Abstract

Universities are facing changes that could be adapted by learning. Organisational learning helps universities in attaining better organisational and sustainable performance. The study aims to combine and explore how organisational learning culture enables organisational learning to contribute to better organisational performance and better sustainable performance, following the natural resource-based view and organisational learning theory. The study examines the relationship between organisational learning culture, organisational learning, organisational performance, and sustainable performance in the university context from university teachers. The author collected 221 surveys from public university teachers in Europe to test the model. The results indicate a positive relationship between organisational learning culture and organisational learning. In addition to that, the positive relationship between organisational learning and organisational performance is indicated. Moreover, the results indicate a positive relationship between organisational learning and sustainable performance. The results also show that the organisational learning process mediates organisational learning culture and university performance. The study addresses a gap in the scarce studies in the university context for organisational learning and sustainable performance. Finally, this study reproduces an organisational model that has been adapted for universities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Universities are facing different types of change, including digitalisation, sustainability, entrepreneurship, and innovation (Leal Filho et al. 2018; Pocol et al. 2022); it is the universities’ obligation to cope with this change (Medne et al. 2022; James et al. 1993). One of the proven ways that help universities adapt to change and increase their performance is learning, more specifically, organisational learning (Kezar and Holcombe 2019). In fact, organisational learning practices and processes can facilitate change and enhance organisations (Argyris and Schön 1996; Fiol and Lyles 1985; Garvin 1993; Huber 1991).

The topic of organisational learning has been discussed since the early nineties when the foundations of organisational learning were further developed during this era (Castaneda et al. 2018). Researchers called for more research to understand organisational learning. Organisations learn when there is information processing that leads to a change in the behaviour and the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and abilities (Kezar and Holcombe 2019; Flores et al. 2012; Jyothibabu et al. 2010; Jiménez Jiménez and SanzValle 2006; Slater and Narver 1995; Huber, 1991). Organisational learning researchers have extended their research to identify the organisational learning predictors to include organisational learning culture (Flores et al. 2012). Organisational learning has been discussed in several industries, but it is considered scarce in the university context (Abu‐Tineh 2011; Voolaid and Ehrlich 2017). Previous research focused on organisational learning capabilities and behaviours. However, the author will focus on organisational learning processes in this study. The organisational learning processes affect organisational performance (Bontis et al. 2002; Crossan and Bapuji 2003; Kontoghiorghes et al. 2005; Sun et al. 2008; Jyothibabu et al. 2010), as well as sustainability and sustainable performance (Iqbal and Ahmad 2021; Kordab et al. 2020; Bilan et al. 2020). However, this relationship in the university sector is understudied, with a gap in organisational learning literature. Especially since universities are considered a complex type of organisation (Elbawab 2022a; Bleiklie and Kogan 2007). Sustainable development was defined as ‘development which meets the needs of the present, without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ by the Brundtland Commission in 1987 (Basiago 1995). Sustainable development and learning share many important elements, including “a challenge to mental models, fostering fundamental change, engaging in extensive collaborative activity and, in some cases, revisiting core assumptions about business and its purpose” (Molnar and Mulvihill 2003, p. 168), therefore several scholars showed the need to understand the relationship between learning in organisations and sustainability (Feeney et al. 2023). Sustainability is used in different domains, including economics and education (Pocol et al. 2022; Basiago 1995). In 2015, The United Nations General Assembly approved the ‘2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’, which contains a set of measures aiming to balance economic progress and the protection of the environment (Leal Filho et al. 2018). The agenda consists of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which, among many other tasks, plan to eradicate poverty and create better health conditions in both developed and developing countries (Leal Filho et al. 2018). Sustainability in higher education institutions can be implemented in teaching, research, governance, and outreach (Leal Filho et al. 2023; Serafini et al. 2022). In fact, higher education’s growth contributes to society’s better sustainable development (Geng et al. 2023; Geng et al. 2020a). Therefore, this is one of the reasons for the need to focus on studying sustainability in higher education. In the research area, sustainability research can be implemented by researchers from various areas who can work independently or collectively on the same project by combining their expertise (Leal Filho et al. 2023; Collin 2009). Additionally, sustainability can be implemented in research by framing higher education institutions’ research in the direction of the SDGs (Serafini et al. 2022). In the teaching area, sustainability can be implemented within the strategies in the curriculum development of promoting sustainability and in planning new courses (Leal Filho et al. 2023; Serafini et al. 2022). Sustainability in the teaching area can also be developed by modifying the existing curriculum with the SDGs (Leal Filho et al. 2023). As for governance, sustainability can be implemented by establishing indicators in rankings that evaluate the performance of higher education institutions concerning compliance with the SDGs. Sustainability within governance can also be implemented by evaluating the level of knowledge, awareness, and attitudes towards the SDGs among academic community members and educators (Serafini et al. 2022). Finally, for the outreach, sustainability can be implemented by disseminating SDGs by training the managers and decision-makers in civil society organisations (Serafini et al. 2022). In this study, the author will focus on the governance of sustainability in education. The relationship between organisational learning and sustainability has been discussed in several studies. A study developed in 2020 assessed the relationship between organisational learning and sustainable organisational performance (Kordab et al. 2020). Another study assessed the relationship between organisational learning and sustainability (Bilan et al. 2020). Subsequently, the lack of studies that evaluate organisational learning and sustainability in universities has emerged.

According to the natural resource-based view (NRBV) theory (Hart 1995), environmentally friendly resources and capabilities play a key competitive advantage in an organisation (Iqbal and Ahmad 2021; Hart 1995). The NRBV theory takes the capabilities and competitive advantage thinking one step further, where the theory posits that the organisation’s competitive advantage can only be sustained when the capabilities creating the advantage are supported by resources not easily duplicated by competitors (Hart 1995). In this study, the resource is the organisational learning. In organisational learning theory, organisational learning is defined as the change that occurs in the organisation, resulting from knowledge memorised in organisations gathered from experience and changes in behaviour resulting from such knowledge (Argote and Miron-Spektor 2011). These experiences and changes in behaviours that happen in the organisation are not easily duplicated by the competitors. To explain organisational learning more thoroughly and to show how organisational learning is a resource that is not easily duplicated, the author will further explain the types of learning that are crucial for the organisational learning theory (Crossan et al. 1999). Organisational learning has two types of learning. The first is characterised by improving the existing routines, and the second is characterised by reframing a situation or solving unclear problems (Edmondson 2002). Since the existing routines and situations will differ from one organisation to another, thus organisational learning can be considered a resource that is not easy to duplicate. Consequently, environmentally friendly resources should have a relationship with organisational learning. Subsequently, this study explores the relationship between organisational learning and sustainable performance (Environmental performance and social performance). The significance of the study is found at both empirical and theoretical levels. Theoretically, it is found to explore the influence of organisational learning as a process on university performance. Also, the influence of learning on sustainability and the role of learning culture among these relationships. This study adds to the theory of organisational learning and, specifically, how to treat organisational learning as a process. Moreover, another significant aspect of this study is addressing the mediation of the organisational learning process in the relationship between organisational learning culture and university performance, as organisational learning culture is proposed to directly affect higher education institutional performance (Kumar 2005). Furthermore, the significance of the study is found in exploring the relationship between organisational learning and sustainable performance in the university context. Finally, it empirically assesses organisational learning and all the relationships in the university’s context.

This study assesses the relationship between organisational learning culture and organisational learning processes. The study will also assess the organisational learning processes with the outcomes, where the relationship between the organisational learning process and university performance is assessed. The study will also assess the relationship between organisational learning processes and sustainable performance. Further, this research assesses the mediation between the organisational learning culture and university performance.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Learning

Organisational learning process

Most scholars agree that organisational learning is known as the change in organisational knowledge, which is acquired through practical experiences (Argote and Miron-Spektor 2011), where this knowledge is then translated into the organisation’s knowledge system (Do et al. 2022). Organisational learning is defined as “the process by which organisations learn” (Chiva et al. 2007, p. 224; Domínguez-Escrig et al. 2022). Organisational learning focuses not only on intentional learning but also on unintentional learning in the organisation (Huber 1991), as organisational learning helps reduce uncertainty (Schönherr et al. 2023). Learning can happen intentionally and unintentionally (Huber 1991). Intentional learning is the main process for scientists and educators. Researchers often think of it as an intentional process directed at improving effectiveness. In contrast, unintentional learning is proposed as unsystematic learning (Huber 1991). Even though previous research has focused on organisational learning as a culture or as an outcome, fewer have discovered organisational learning processes (Pham Thi Bich, Tran Quang 2016). Consequently, the author focuses on the organisational learning process due to the scarcity of research in this area. Subsequently, universities’ organisational learning will be better understood (Abu‐Tineh 2011) and could be enhanced.

Huber (1991) suggested that organisational learning includes four processes. The processes are information acquisition, knowledge dissemination, shared interpretation, and organisational memory (Huber 1991; Santos-Vijande et al. 2012). The relevant organisational learning processes in the university sector proposed by the study (Elbawab 2022b) are information acquisition and knowledge dissemination. In this research, the author has empirically assessed the organisational learning processes and proposed that the relevant processes are information acquisition and knowledge dissemination. Hence, these are the processes used in this paper. The process of information acquisition is about acquiring information from various sources, either internally or externally (Huber 1991; Flores et al. 2012). The internal information is gathered from inside the organisation and from the company’s creator or previously acquired experience. As for the external information, it is gathered from the competitors and the marketplace through acknowledging and acquiring the implicit analysis of the actions of the competitors. On other occasions, organisations look for the best practices, and they solve the problems by identifying key tendencies, collecting external information, and comparing their performance with that of their relevant competitors (Santos-Vijande et al. 2012).

Knowledge dissemination is a process that takes place through formal settings (e.g., departmental meetings, discussion of future needs, and cross-training) and informal interactions among individuals within the organisation (Kofman and Senge 1993). The creation of formal networks and databases encourages communication by guaranteeing both the accuracy and the rapid dissemination of information. These initiatives need more informal exchange mechanisms to complement them so that any tacit knowledge individuals gather is transformed into explicit knowledge. Researchers perceive organisational learning as either an organisational process or an organisational capability. Organisational capability is the organisational and managerial characteristics that facilitate the organisational learning process or allow an organisation to learn (Aragón et al. 2014; Chiva et al. 2007; Tohidi et al. 2012). In the present study, organisational learning is viewed as a process that occurs inside the organisation on an organisational level. Organisational learning as a process focuses on the set of actions that occur in the organisation to help in the learning process. In the university context, researchers have called for more studies to understand the organisational learning process (Abu‐Tineh 2011). Voolaid and Ehrlich (2017) assessed organisational learning in two Estonian universities, but also from a cultural perspective and with the perception of the two universities. The researchers insisted on the scarcity of organisational learning research in higher education institutions and the need for a study that empirically assesses organisational learning in more universities from different countries and regions. Further, more research is needed to understand the multidimensionality from an aggregated perspective.

Organisational learning culture

Organisational learning culture is a general predictor of the organisational learning process. The organisational learning culture is essential for organisational learning (Flores et al. 2012). Higher education institutions need to adapt to the competition with new discoveries and ideas proactively. The development of a learning culture could be the key, to help through gathering, organising, sharing, and analysing the knowledge across the institution (Kumar 2005). Previously, several predictors have been mentioned for organisational learning, including knowledge-sharing behaviour (Park and Kim 2018), goal orientation (Chadwick and Raver 2012), participative decision-making, openness, learning orientation and transformational leadership (Flores et al. 2012). Flores et al. (2012) mentioned that these predictors are part of the culture, whereas organisational learning culture is considered a predictor that should be assessed in relation to organisational learning. Consequently, this study assesses organisational learning culture as a predictor of organisational learning. Pham Thi Bich and Tran Quang (2016) recommend that more predictors positively influencing organisational learning should be explored.

Organisational culture is a factor that facilitates organisational learning (e.g., Ahmed et al. 1999; Campbell and Cairns 1994; Conner and Clawson 2004; Maccoby 2003; Marquardt 1996; Marsick and Watkins 2003; Pedler et al. 1997; Rebelo and Duarte Gomes 2011). An organisational learning culture is described as the values, beliefs and assumptions that emphasise creating collective learning in an organisation (Sorakraikitikul and Siengthai 2014). Researchers have shown the importance of an organisational learning culture as a culture that creates a supportive environment. This culture enables and influences learning and knowledge sharing at the individual, team, and organisational levels (Kontoghiorghes et al. 2005; Marsick and Watkins 2003). Despite the importance of organisational learning culture in the literature (e.g., Marquardt 1996; Pedler et al. 1997), there is still a lack of research explicitly concerning learning culture (Rebelo and Duarte Gomes 2011) and its relationship with organisational learning. Also, a study developed by Wahda (2017) has agreed with the scarcity of studies that assess organisational learning culture in higher education institutions. In Wahda’s (2017) study, the results show that organisational learning culture is found in a university in Indonesia, and it also shows the importance of applying organisational learning culture in higher education institutions as it facilitates the learning processes. In conclusion, there is a lack of research addressing this relationship in the university context.

Previous research showed a positive relationship between participative decision making, openness and leadership and organisational learning (Flores et al. 2012). Since these predictors are considered part of the organisational culture, the author proposes a positive relationship between organisational learning culture and organisational learning. This study will explore the relationship between the organisational learning culture (as a predictor) and the organisational learning process in the university context. Accordingly, the author hypothesises:

H1: There is a positive relationship between the organisational learning culture and the organisational learning process.

H1a: There is a positive relationship between system connection and dialogue and inquiry and information acquisition.

H1b: There is a positive relationship between system connection and dialogue and inquiry and knowledge dissemination.

Performance

Organisational performance

The organisation’s performance depends on the achievement and the progress of the strategy identified by the organisation (Davies and Walters 2004; Mohammad 2019). Performance needs to meet the organisational strategies and the organisational goals because it shows the organisation’s success. Several studies have mentioned Organisational performance as an outcome of organisational learning (Aragón et al. 2014; Mohammad 2019). This research focuses on university performance. Few studies have focused on assessing the relationship between organisational learning and organisational performance for example (Bontis et al. 2002; Crossan and Bapuji 2003; Jyothibabu et al. 2010; Kontoghiorghes et al. 2005; Sun et al. 2008). Some previous empirical studies proposed the positive influence of organisational learning on organisational performance (Aragón et al. 2014; Mohammad 2019). According to previous research, organisational learning helps to improve the performance of an organisation.

Most previous research has focused on the relationship between organisational learning as a capability and performance (e.g., Camps and Luna-Arocas 2012; Hurley and Hult 1998; Keskin 2006; Rhodes et al. 2008). Nevertheless, the present study focuses on organisational learning as a process and its impact on university performance. In the context of universities, few empirical studies have shown a positive relationship between organisational learning and university performance (Guţă 2014; Pham Thi Bich and Tran Quang 2016). Guţă (2014) did not assess the relationship empirically, while Pham Thi Bich and Tran Quang (2016) study assessed university performance in only one university. More research is needed to assess the relationship between the organisational learning process and organisational performance (Pham Thi Bich and Tran Quang 2016). This paper assesses university performance from teachers’ opinions from several universities. From the previous research, the author hypothesised:

H2: There is a positive relationship between organisational learning processes and university performance.

The relationship between organisational learning culture and organisational performance has also been discussed in the previous literature, where a positive relationship has been identified between organisational learning culture and organisational performance (Ellinger et al. 2002; Sorakraikitikul and Siengthai 2014). Organisational learning culture supports promoting and facilitating workers’ learning, hence contributing to organisational development and performance (Rebelo and Duarte Gomes 2011). Although there is little empirical evidence concerning the relationship between organisational learning culture and the performance of public organisations, some studies still allow us to infer that organisational learning culture is related to performance (Choi 2020). This paper assesses educators’ opinions in public universities, as public organisations are understudied. Hence, we hypothesised the following:

H3: There is a positive relationship between the organisational learning culture and university performance.

The study will also assess the mediation of the organisational learning process in the relationship between organisational learning culture and university performance. Building on the previous hypotheses H1, H2 and H3, we propose that organisational learning culture solely is not sufficient to improve the university’s performance and that there is a need to involve organisational learning to enhance the university’s performance. Subsequently, we hypothesise the following:

H4: The organisational learning process mediates the relationship between organisational learning culture and university performance.

Sustainable performance

Nowadays, sustainability has been called for in different business models (Zhang et al. 2019). The concept of sustainability helps organisations to improve different processes, which results in higher organisational performance (Zhang et al. 2019). Other studies have mentioned sustainability as an output of organisational learning (Kordab et al. 2020; Bilan et al. 2020; Iqbal and Ahmad 2021). The more learning that happens on an organisational level, the more sustainable the organisation is. In a study developed by Bilan et al. (2020), the authors advised that organisational learning significantly improves the firm’s sustainability. Other studies have focused on sustainable performance (Kordab et al. 2020; Iqbal and Ahmad 2021). Kordab and his colleagues mentioned the positive relationship between organisational learning and sustainable organisational performance (Kordab et al. 2020). The study developed by Iqbal and Ahmad (2021) states that organisational learning significantly influences sustainable performance. Another study developed in 5 companies in Norway and Italy has explored the internalisation of a sustainable environment through the learning process (Bianchi et al. 2022; Massimo and Nora 2022). The literature discussing the relationship between organisational learning and sustainability is scarce (Kordab et al. 2020). The earlier mentioned studies have assessed the relationship between Malaysian manufacturing organisations (Bilan et al. 2020), audit and consulting companies in the Middle East (Kordab et al. 2020), and small and medium-sized enterprises in Pakistan (Iqbal and Ahmad 2021). On the other hand, this study assesses the relationship between organisational learning and sustainable performance in the university context.

Sustainability in higher education institutions helps in the development of regenerative societies. This help is provided by educators as they influence ideologies and perspectives regarding sustainability in society (Leal Filho et al. 2023). In the review study developed by (Serafini et al. 2022) for the articles related to higher education institutions and SDGs, only four per cent of the studies considered professors as the target audience. Hence, in this study, the author assesses sustainable performance from educators’ perceptions as it is scarce. Therefore, the hypothesis is developed as below:

H5: There is a positive association between organisational learning and sustainable performance.

H5a: There is a positive relationship between information acquisition, knowledge dissemination and sustainable environmental performance.

H5b: There is a positive relationship between information acquisition, knowledge dissemination and sustainable social performance.

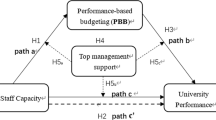

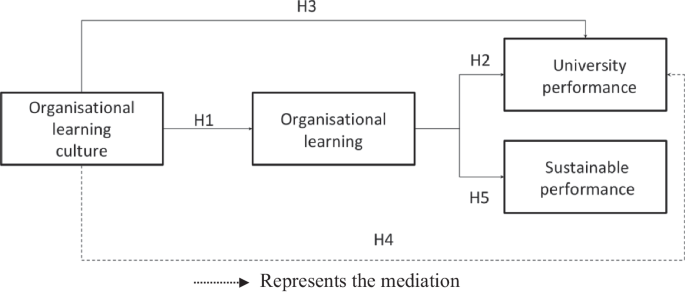

Finally, Fig. 1 shows the proposed model of this study, which includes the proposed hypotheses.

Methodology

Data collection and sample

This study’s sample mainly focused on university teachers from several European universities. Self-selection sampling is used in this paper; this method helps the researcher better explore the research area and understand the relationships (Saunders et al. 2007). The self-selection sampling method relies on the willingness of the participant to participate in the questionnaire. An email invitation with the link to the online questionnaire has been sent to a range of professors. Moreover, university teachers who accepted to participate are the ones who were considered in this study. The researcher has gathered the emails of the university teachers from the university websites.

Data were gathered through an online questionnaireFootnote 1. The questionnaire is developed from the previous literature. The questionnaire was developed on Qualtrics, and an anonymous link was sent to the respondents. The researcher sent the questionnaire to 10366 university teachers. The university teachers are from different schools and departments, including business, psychology, science, and engineering schools. The researcher received 525 replies, which corresponds to a response rate of 5%. Of the 525 responses received, 304 were incomplete, so we excluded the incomplete questionnaires and kept 221 questionnaires. The questionnaire was sent to 53 public universities in Europe. The countries were Portugal, Spain, Italy, France, Germany and Greece.

The sample is composed of (36.7%) associate professors, (15.4%) assistant professors, (22%) full professors, (6.8%) lecturers and assistants, (3.2%) invited assistant/associate/full professors and (15.8%) respondents who did not declare their job level. Also, the majority of the sample (65.2%) has worked more than seven years in the same university and more than five years in the same team (66.5%). As for the age of the participants, (49.9%) were of age 50 years and above, and the majority of the sample (47.5%) was composed of Males, followed by (37.6%) Females and (14.9%) ‘don’t prefer to say’. The survey was conducted from October 2022 to January 2023. Two reminder emails were sent to the university teachers. Moreover, the design of this study is a correlational design, where all the proposed relationships are studied between organisational learning as a process and its antecedent and outcomes.

Measures

The constructs used to assess the indicators in this study are obtained from previous scientific studies, where their reliability and validity were previously tested and verified. Organisational learning culture was assessed using the measure of the Dimensions of Learning Organisations Questionnaire (Watkins and Marsick 1993, 1997), which was adapted and validated to the university’s context in Elbawab (2022b). The adapted measure included two sub-dimensions. The scale consisted of 8 items that measured the two sub-dimensions: dialogue and inquiry and system connection. The participants indicated to what extent they agreed with each of the eight items on a 7-point rating scale (1 = totally disagree, 7= totally agree). An example of the items is: “In my university, whenever academic staff state their view, they also ask what others think.” we checked the scales’ internal consistency to measure these indicators by calculating Cronbach’s alpha. The results indicate strong scale reliability for both system connection (0.88) and dialogue and inquiry (0.87).

The organisational learning process scale was assessed based on the Santos-Vijande et al. (2012) scale and then adapted to the university’s context in Elbawab (2022b). The scale consists of 8 items that measure two subdimensions: information acquisition and knowledge dissemination. Individuals indicated to what extent they agreed with each of the eight items on a 7-point rating scale (1 = totally disagree, 7 = totally agree). An example of the items is: “We have a meeting schedule among departments and with the dean to integrate the existing information.” We checked the scales’ internal consistency to measure these indicators by calculating Cronbach’s alpha. The results indicate strong scale reliability for information acquisition (0.89) and knowledge dissemination (0.79).

As for the performance, one variable was used to evaluate university performance, and another was used to evaluate sustainable performance. The university performance questionnaire is based on Jyothibabu et al. (2010), but the scale is adapted to the university context. The measured scale includes seven items. All items were scored on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree, 7= totally agree). An example of the items is: “There is continuous improvement in my university”. In this study, the Jyothibabu et al. 2010 scale has been adjusted from a 6-point to a 7-point Likert scale as the 7-point Likert scale reaches the upper limit of reliability (Allen and Seaman, 2007; Leung, 2011). Also, removing a neutral point introduces “a forced choice in the scale” (Allen and Seaman 2007), whereas our focus in this study is to avoid the forced choice. The reliability score of this scale in this study is 0.93; however, Jyothibabu et al. (2010) Cronbach alpha scored 0.90. In conclusion, the Cronbach alpha score in this study has improved. All factor loadings are significant (p < 0.05) and indicate strong factor loadings. As for sustainable performance, it is assessed based on Iqbal and Ahmad (2021), but only the environmental and social performance were adopted in this study. Since the economic performance measure mainly focuses on sales growth, income stability, profitability and return on investment. At the same time, the activities of public universities are driven by the pursuit of excellence and prestige maximisation, which does not necessarily imply economic efficiency traditionally assumed for profit-maximising business establishments (Kipesha and Msigwa 2013). Therefore, sustainable economic performance will not be assessed in this study for these reasons.

These measures are relevant to the university context, which follows the QS world rankings, where the environmental impact and the social impact of each university are addressed. The sustainable performance scale is adapted to the university context. All items were scored on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree, 7 = totally agree). An example of the items is: “Your university is concerned about waste management”. The results indicate strong scale reliability for sustainable environmental performance (0.88) and sustainable social performance (0.82). All factor loadings are significant (p < 0.05) and indicate strong factor loadings.

Data analysis

The author assessed the descriptive statistics in this study by identifying the means and standard deviations. Also, the author measured the factor loading for all the questionnaire items. Moreover, the author tested the hypotheses with the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics Suite, version 27. The author assessed the correlations among the relationships and assessed the models using regression analysis using SPSS. Moreover, the author used the PROCESS macro by Andrew Hayes (2013) in SPSS to test the mediation hypothesis.

Results

The means, standard deviations, and correlations for all the variables in the study are shown in Table 1. The results shown are a consideration of a sample where more than 65% have worked in the same university for more than seven years, and more than 74% of the sample are assistant, associate, and full professors. The highest means are for performance and sustainability environmental performance. At the same time, the lowest means are for system connection and dialogue and inquiry. Factor loadings were then calculated for all items, which were all higher than 0.64% (shown in Table 2).

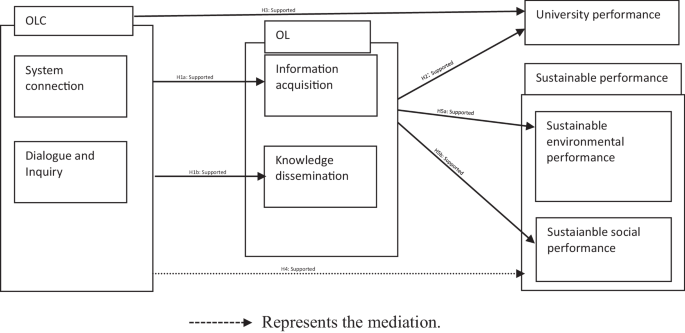

The findings show the acceptance of H1, there is a strong significant positive relationship between dialogue and inquiry and information acquisition (r = 0.70, p < 0.001), and there is likewise a strong positive significant relationship between dialogue and inquiry and knowledge dissemination (r = 0.64, p < 0.001). There is a significant positive relationship between system connection and information acquisition (r = 0.59, p < 0.001), and a significant positive relationship emerged between system connection and knowledge dissemination (r = 0.52, p < 0.001). Multiple regression was run to predict information acquisition from dialogue, inquiry, and system connection. There is a positive effect between dialogue and inquiry and information acquisition (β = 0.520, p < 0.01); also, there is a positive effect of system connection and information acquisition (β = 0.197, p < 0.01). These variables statistically significantly predicted information acquisition, R2 = 0.522. All two variables added statistically significantly to the prediction, p < 0.05. Therefore, H1a is supported. Multiple regression was run to predict knowledge dissemination from dialogue, inquiry, and system connection. There is a positive effect of dialogue and inquiry on knowledge dissemination (β = 0.544, p < 0.01), and there is a positive effect between system connection and knowledge dissemination (β = 0.162, p < 0.01); these variables statistically significantly predicted information acquisition, R2 = 0.429. All two variables added statistically significantly to the prediction, p < 0.05. Therefore, H1b is supported. These findings show the positive relationship between organisational learning culture and organisational learning.

The findings also support H2. A significant positive relationship between information acquisition and university performance is found (r = 0.58, p < 0.001), and there is a strong positive significant relationship between knowledge dissemination and university performance (r = 0.64, p < 0.001). A multiple regression was run to predict university performance from information acquisition and knowledge dissemination. There is a positive effect between information acquisition and university performance (β = 0.250, p < 0.01); also there is a positive effect between knowledge dissemination and university performance (β = 0.381, p < 0.01). These variables statistically significantly predicted information acquisition, R2 = 0.451. All two variables added statistically significantly to the prediction, p < 0.05. Therefore, H2 is supported. These findings show the positive relationship between the organisational learning process and university performance.

The findings support H3, where there is a strong significant positive relationship between system connection and university performance (r = 0.57, p < 0.001), also there is a strong positive significant relationship between dialogue and inquiry and university performance (r = 0.66, p < 0.001). Multiple regression was run to predict university performance from system connection, dialogue and inquiry. There is a positive effect between system connection and university performance (β = 0.184, p < 0.01), and there is a positive effect between dialogue and inquiry and university performance (β = 0.440, p < 0.01). These variables statistically significantly predicted information acquisition, R2 = 0.470. All two variables added statistically significantly to the prediction, p < 0.05. Therefore, H3 is supported. This concludes the positivity of the relationship between organisational learning culture and university performance.

This study also developed a mediation analysis, H4, using Hayes (2013). Macros were developed to assess the mediation analysis of the models on SPSS. Macros help estimate the indirect effect with a bootstrap approach (Cole et al. 2008).

Organisational learning culture (dialogue and inquiry and system connection) has an indirect effect on university performance mediated by organisational learning processes (information acquisition and knowledge dissemination), which supports H4. Dialogue and inquiry have an indirect impact on university performance mediated by information acquisition (IE = 0.1427). The indirect effect is statistically significant; a bootstrapped 95% confidence interval around the indirect effect did not contain zero CI[0.482, 0.2423]. Also, system connection indirectly affects university performance mediated by information acquisition (IE = 0.1800); the indirect effect is a statistically significant bootstrapped 95% confidence interval around the indirect effect that did not contain zero, CI[0.1104,0.2548]. Dialogue and inquiry have an indirect impact on university performance mediated by knowledge dissemination (IE = 0.2038). The indirect effect is a statistically significant bootstrapped 95% confidence interval around the indirect effect that did not contain zero, CI [0.1306, 0.2865]. Moreover, system connection has an indirect effect on university performance mediated by knowledge dissemination (IE = 0.1970). The indirect effect is a statistically significant bootstrapped 95% confidence interval around the indirect effect that did not contain zero, CI [0.1351, 0.2638].

The findings support H5, where there is a strong significant positive relationship between Information acquisition and sustainable environmental performance (r = 0.57, p < 0.001), Whereas a positive significant relationship has been found between information acquisition and sustainable social performance (r = 0.559, p < 0.001). Moreover, a positive significant relationship is detected between knowledge dissemination and sustainable environmental performance (r = 0.526, p < 0.001), and finally, a positive significant relationship is detected between knowledge dissemination and sustainable social performance (r = 0.550, p < 0.001). A multiple regression was run to predict sustainable environmental performance from information acquisition and knowledge dissemination. There is a positive effect between information acquisition and sustainable environmental performance (β = 0.365, p < 0.01); also, there is a positive effect between knowledge dissemination and sustainable environmental performance (β = 0.208, p < 0.01). These variables statistically significantly predicted information acquisition, R2 = 0.362. All two variables added statistically one significantly to the prediction, p < 0.05. Therefore, H5a is supported. A multiple regression was run to predict sustainable social performance from information acquisition and knowledge dissemination. There is a positive effect between information acquisition and sustainable social performance (β = 0.299, p < 0.01); also, there is a positive effect between knowledge dissemination and sustainable social performance (β = 0.252, p < 0.01). These variables statistically significantly predicted information acquisition, R2 = 0.365. All two variables added statistically significantly to the prediction, p < 0.05. Therefore, H5 b is supported. It is deduced that a positive relationship exists between the organisational learning process and sustainable performance. The results are summarised in Table 3, and the new proposed model is found in Fig. 2.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper examines the impact of the organisational learning culture on the organisational learning process in the university context as well as the impact of the organisational learning process on a university’s performance and sustainable performance. The literature showed a gap where organisational learning processes are rarely assessed in universities (Abu‐Tineh 2011; Elbawab 2022b). Also, most of the previous studies assess the impact of culture on organisational learning, but few studies have assessed the impact of organisational learning culture on the organisational learning process. Another gap has emerged, where the impact of organisational learning on sustainability is understudied (Alerasoul, 2022). Whereas this study also focuses on empirically assessing the relationship between organisational learning and sustainable performance. Learning normally empowers the occurrence of sustainability in organisations and enhances sustainability practices.

The findings of this study contribute to the literature in many ways. The findings support the positive relationship between an organisational learning culture and an organisational learning process, which supports H1. Organisational learning culture is represented by dialogues and inquiry and the system connection. Further, organisational learning processes are represented in this study as the process of information acquisition and knowledge dissemination. Dialogue and inquiry and system connection have a positive impact on information acquisition and knowledge dissemination. So, the findings indicate that the more the organisational learning culture increases in the university, the more the organisational learning processes occur. This relationship between the organisational learning culture and the organisational learning process is assessed empirically in this research, contrary to other studies where previous research always focused on organisational culture rather than organisational learning culture (Cho et al. 2013; Liao et al. 2012). This research also contributes to organisational learning research as the results indicate that the organisational learning culture is one of the antecedents to the organisational learning process. Accordingly, top management in universities needs to focus on improving the organisational learning culture to have better organisational processes. Also, human resources practitioners need to highlight the importance of maintaining organisational learning culture in organisations as it facilitates the organisational learning process.

The findings also support H2 which posits the positive relationship between the organisational learning process and a university’s performance. Our findings agree with previous research that supported the positive relationship between organisational learning and performance in organisations (Aragón et al. 2014; Bontis et al. 2002; Jyothibabu et al. 2010). We mainly focus on organisational learning processes that enhance a university’s performance. Our findings show that the better the information acquisition process and knowledge dissemination processes are, the better the university’s performance is going to occur in universities. So practically, the higher the efficiency of the acquisition of knowledge process, like acquiring the information from two sources is leading to a better the university’s performance. The two sources of information acquisition are internally from within the university and externally from other universities in the market. In this research, information acquisition is the process of identifying tendencies and problems, which leads to a better performance by the university.

This research has focused on the relationship between organisational learning culture and university performance. The findings in this study agree with previous studies (Ellinger et al. 2002; Sorakraikitikul and Siengthai 2014) that there is a positive relationship between the organisational learning culture and performance; the present study assessed this relationship empirically in the context of public universities while other studies have focused on various industries. (Choi 2020) focused on the assessment of the relationship between organisational learning culture and performance in public organisations generally. The present study focused on public universities as part of the public organisations in any country. The results show support for H3. Moreover, the findings suggest that universities that have a supportive learning culture will lead to better performance. If universities encourage a strong learning culture among their teachers, staff, and students, this will eventually lead to better performance.

Moreover, the organisational learning process mediates the relationship between organisational learning culture and university performance, as illustrated by the findings. These results support H4. Also, these results indicate that the more the top managers and human resources practitioners in universities encourage a learning culture and develop strong organisational learning processes, the higher the university’s performance will be. These findings demonstrate the need for alignment between the university learning culture and the university learning processes as they will promote better university performance. The findings indicate that organisational learning culture indirectly impacts university performance when it is mediated by organisational learning. From a theoretical lens, the organisational learning in this study is stated as a process. Hence, the organisational learning culture is considered an antecedent to the organisational learning process. In this study, the adapted model of culture (system connection and dialogue and inquiry) tests the culture with the process (information acquisition and knowledge dissemination); the results have shown both a direct and an indirect impact on university performance. The direct impact of culture on university performance has been found in the (Wahda, 2017) study, where this study agrees with (Wahda 2017) study. However, since this study has looked at organisational learning as a process and culture as an antecedent, it provided additional theoretical evidence of the indirect impact of organisational learning culture on performance, mediated by organisational learning as a process. This study also agrees with (Rebelo and Gomes 2017) study, where organisational culture emerges as a key concept and an essential condition that would promote and support learning in organisations. Moreover, in the following study, organisational learning culture is considered an antecedent to the organisational learning process. Whereas university performance is considered an outcome of the organisational learning process. Therefore, this study supports the (Rebelo and Duarte Gomes 2011) study that considers organisational learning culture as an antecedent to the organisational learning process. At the same time, the theoretical contribution that lies in this study is to address the model and consider the relationship between organisational learning culture and university performance directly and indirectly through the organisational learning process.

Another part of the framework assessed in this study is the impact of organisational learning processes on sustainable performance. Most universities nowadays focus on the importance of sustainability and apply sustainability practices. Also, the universities capitalise on the SDGs that are developed by the European Union. Whereas universities call for relating future research with the SDGs, as it helps in the sustainable development of society (Serafini et al. 2022). Moreover, universities focus on enhancing their sustainable environment. Still, this study addressed a significant gap, where few research studies have empirically addressed the impact of organisational learning on sustainable performance. And this research highlights the importance of applying this relationship and helps imply sustainable performance as an indicator for universities to be used in the future.

Sustainable performance in this study is considered another outcome of organisational learning. The findings of this study show support for H5. This study confirms the previous study findings (Iqbal and Ahmad 2021) that there is a positive impact between organisational learning and sustainable performance. However (Iqbal and Ahmad 2021) study did not assess the organisational learning process in universities, so this study develops it. The findings of this paper indicate the positive impact of information acquisition and knowledge dissemination on sustainable environmental performance and sustainable social performance. Therefore, when the organisational learning in universities is deepened and increased, the sustainable performance of the universities is better.

Finally, this study has created a suitable model to assess organisational learning processes, antecedents, and outcomes in universities. It has contributed to the theory of organisational learning; it shows a newly adapted model of organisational learning culture as well as organisational learning as a process and its influence on a university’s performance and the sustainable performance of the organisation. This adapted model may be considered novel because it indicates the antecedents, processes, and outcomes of organisational learning. Also, this model relates between NRBV and organisational learning theories, which is considered a theoretical contribution. Moreover, this model is tested in European universities and is considered an empirical contribution.

Implications and future research

Theoretical implications

For the theoretical implications of describing organisational learning in universities, most previous research focused on assessing learning organisations; for example, the review developed by (Örtenblad and Koris 2014) showed the studies focused on assessing learning organisations. Furthermore, few studies focused on the learning processes and identified which organisational learning processes are more relevant to public universities and the education sector.

We have validated the organisational learning predictor as an organisational learning culture. Also, we have validated the organisational learning outcomes: university performance and sustainable performance.

The relevant learning processes are knowledge dissemination and information acquisition, where these processes are mainly representing the organisational learning processes in universities. This study recommends using the organisational learning developed model as it is relevant to universities.

Since researchers proposed that organisational learning culture is an important facilitator of the organisational learning process (Marsick and Watkins 2003). This study focused on assessing organisational learning culture’s impact on the organisational learning process. Previous research mainly focused on assessing the organisational culture’s impact on organisational learning (e.g., Oh and Han 2020; Rebelo and Duarte Gomes 2011). Few researchers focused on the impact of organisational learning culture on organisational learning. Previous research showed organisational culture as decision-making processes, openness, learning orientation, and leadership (Flores et al. 2012). In this study, organisational learning culture was described as the collective learning culture that enhances the organisational learning activities (Sorakraikitikul and Siengthai 2014). Subsequently, it is evident that this gap was addressed and studied in this study. The findings show a strong relationship between organisational learning culture and organisational learning processes in education.

Moreover, the mediation of organisational learning processes between organisational learning culture and university performance is another theoretical contribution to organisational studies. As the previous research mainly focused on the impact of organisational learning culture on organisational performance (Sorakraikitikul and Siengthai 2014), few studies focused on mediation analysis. The findings of this study show that organisational learning culture indirectly impacts university performance when it is mediated by both organisational learning processes (information acquisition and knowledge dissemination). These findings show the importance of having an effective learning culture and efficient organisational learning processes on the organisational level as they help improve university performance.

Previous studies focused on assessing the relationship between organisational learning and organisational performance (Bontis et al. 2002; Jyothibabu et al. 2010). Scarce studies focused on university performance, while in the meantime, university performance reveals the success of the university and the achievement of its goals. Finally, this study has contributed to organisational studies by exploring the relationship between organisational learning and sustainable performance and curating a model specifically for higher education institutions.

Practical implications

This research serves universities; the implications of this research could be adapted to various faculties. The result of this investigation recommends that when universities work on organisational learning culture, it is followed by enhancing the organisational learning process. Subsequently, the organisational performance and sustainable performance will be improved. This section will provide implications and countermeasures for different stakeholders related to the universities.

To develop the organisational learning culture, universities should work on their dialogue and inquiry process and their system connection process. A learning culture that promotes more dialogue and inquiry among the university members is the target. Hence, the organisational learning culture should be encouraged at all university levels, including among deans, heads of departments, directors, and teachers. The author of the study suggests that deans hold organisational meetings for the faculty members (for example, semester meetings and monthly meetings) mainly to discuss the faculty’s point of view, to share feedback and to empower the experimentation and questioning of the process, to reach for shared view and perspective reasonably. For the teacher, the author recommends attending the meetings with the capacity to inquire about the process, share their feedback and opinions and listen to other views. At the same time, the author recommends enhancing the organisational learning culture by focusing on the system connection.

The author recommends having an ongoing connection with the market to know their needs. Subsequently, the department heads and the director of the programs design new curricula and update the existing ones to align the curriculum with the market needs. We recommend that the teachers support the system connection by advising and recommending the new market demands and technologies in their classes and for the program directors and department heads. Subsequently, both these actions will help increase the organisational learning culture in universities.

After providing the necessary organisational learning culture, universities should develop their organisational learning process in order to increase their performance. To develop the organisational learning process, universities are recommended to capitalise on information acquisition and processes to disseminate knowledge.

For the information acquisition process, acquiring information from two sources improves the university’s performance. The two sources of information acquisition are internally from within the university and externally from other universities in the market. The author recommends that the deans, as well as the heads of departments, focus on acquiring the information internally, whether the students’ satisfaction, the feedback about the curriculum, and even the successful teaching methodologies. The deans need to focus on the university’s previous experiences and align the learning processes with the business environment. As for the external information, deans and rectors who have the bigger image need to acquire the information from competitors (e.g. international universities) and the marketplace to develop their analyses regarding each academic year and the long-term plans. The rectors will help empower the organisational learning processes to flow throughout the university. Practically, the top management in the university needs to look for the best practices internally and externally and solve problems by identifying the key tendencies, whereas in this process, the rectors, deans, program directors, heads of departments and teachers need to share and collaborate. Meanwhile, the information acquisition process is enhanced by collecting not only the information but also the best practices and pedagogies from the competitors. Also, the employers’, policymakers’, and governors’ perspectives should be acquired.

Another practice for enhancing the information acquisition process is comparing the university’s performance to other universities. Acquiring information sources could be formally through the formal reports published on a yearly basis (ex: public university performance reports, universal rankings and amount of collaboration and funds provided to this university), whereas informal sources of acquiring information like assessing the performance of the university on social media. Hence, different stakeholders are involved in the information acquisition process.

As for the second process, knowledge dissemination, the author recommends that universities focus on both the formal and informal interaction between employees to enhance the dissemination of knowledge. For the formal interactions, the author advises rectors and deans to focus on meetings and training that will enhance the continuous learning process and efficiently use the university database. Moreover, deans should enhance the formal networks among their universities and the rest of the universities, for example, through exchanging professors and publishing research papers. These practices will help disseminate the information rapidly and accurately. As for the informal interaction and communication between employees, the author advises the teachers to share knowledge, best practices, new teaching methods, and new tendencies in research and the market with each other. The author also advises university heads of departments to encourage informal interaction between teachers to support the university’s organisational learning. Since the government governors are involved in the process, the author recommends that university heads contact government governors. Government governors can help by disseminating the goals and future plans of the government, as well as the best practices from different universities so that the universities can adapt their learning processes.

Another example of an organisational learning process may be found during the departmental and pedagogical meetings, during which the future of the courses, the programmes, and the schools are discussed, this leads to better dissemination of knowledge and eventually a better performance by the university. Therefore, top managers in universities need to focus on the implementation of the organisational learning processes in their universities as it helps in having better performance and eventually adapt to change and university success (Meshari et al. 2021).

Another important point is that universities need to acquire sustainable performance as it is also one of the indicators of the university rankings that has been recently added to the university’s ranking (like the QS world ranking). Where the SDGs in the QS world ranking, mainly focus on the environmental impact and the social impact of each university by indicating the SDGs rating of each university regarding social and environmental impact.

Finally, top managers in universities need to adapt the universities to the change that is occurring internationally and promote having a better sustainable performance to also reflect in their ranking. These will eventually reflect in the university’s success.

Since the findings show that there is a positive impact of organisational learning on sustainable performance, then it is recommended to deliver training for top managers and decision makers in civil society organisations and government governors to enhance sustainable development outreach. Moreover, in order to focus on the importance of sustainable performance in the meetings and the conferences that are developed in the organisations.

In conclusion, all these recommendations will likely help universities achieve better performance. Top managers like deans, rectors and school heads in universities need to focus on the learning flow within the university. They need to focus on the organisational learning process at the organisational level. The author suggests for the future of this research stream to assess this model on a broader scope, as more universities from outside Europe could be evaluated. As this model showed its validity in various public universities. Also, it is recommended to assess this model in private universities, as the private universities have different regulations, organisational learning culture and performance goals.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and/or analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Abu‐Tineh AM (2011) Exploring the relationship between organizational learning and career resilience among faculty members at Qatar University. Int J Edu Manag 25(6):635–650. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513541111159095

Ahmed PK, Loh AYE, Zairi M (1999) Cultures for continuous improvement and learning. Tot Quality Manag 10(4-5):426–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/0954412997361

Alerasoul SA, Afeltra G, Hakala H, Minelli E, Strozzi F (2022) Organisational learning, learning organisation, and learning orientation: An integrative review and framework. Human Res Manag Rev 32(3):100854

Allen IE, Seaman CA (2007) Likert scales and data analysis. Quality Prog 40(7):64–65

Aragón M, Jimenez‐Jimenez D, Sanz Valle R (2014) Training and performance: The mediating role of organizational learning. Business Res Quart 3(10):17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cede.2013.05.003

Argote L, Miron-Spektor E (2011) Organizational Learning: From Experience to Knowledge. Organization Sci 22(5):1123–1137. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0621

Argyris C, Schön D (1978) Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective. Reis, (77/78), 345–348. https://doi.org/10.2307/40183951

Argyris C, Schön D (1996) Organizational learning: a theory of action perspective. Reading: Addison-Wesley

Basiago AD (1995) Methods of defining ‘sustainability. Sustainable Dev 3(3):109–119

Bianchi G, Testa F, Boiral O, Iraldo F (2022) Organizational Learning for Environmental Sustainability: Internalizing Lifecycle Management. Org Environ 35(1):103–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026621998744

Bilan Y, Hussain HI, Haseeb M, Kot S (2020) Sustainability and economic performance: Role of organizational learning and innovation. Enginee Econ 31(1):93–103. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.ee.31.1.24045

Bleiklie I, Kogan M (2007) Organization and governance of universities. Higher Edu Policy 20:477–493

Bontis N, Crossan MM, Hulland J (2002) Managing An Organizational Learning System By Aligning Stocks and Flows. J Manag Stud 39(4):437–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.t01-1-00299

Campbell T, Cairns H (1994) Developing and Measuring the Learning Organization. Industrial Commercial Training 26(7):10–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/00197859410064583

Camps J, Luna-Arocas R (2012) A Matter of Learning: How Human Resources Affect Organizational Performance. British Journal of Management, no–no. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2010.00714.x

Castaneda DI, Manrique LF, Cuellar S (2018) Is organizational learning being absorbed by knowledge management? A systematic review. J Knowledge Manag 22(2):299–325. https://doi.org/10.1108/jkm-01-2017-0041

Chadwick IC, Raver JL (2012) Motivating Organizations to Learn. J Manag 41(3):957–986. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312443558

Chiva R, Alegre J, Lapiedra R (2007) Measuring organisational learning capability among the workforce. Int J Manpower 28(3/4):224–242. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720710755227

Cho I, Kim JK, Park H, Cho N-H (2013) The relationship between organisational culture and service quality through organisational learning framework. Total Quality Manag Business Excellence 24(7-8):753–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2013.791100

Choi I (2020) Moving beyond Mandates: Organizational Learning Culture, Empowerment, and Performance. Int J Public Admin 43(8):724–735. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2019.1645690

Cole MS, Walter F, Bruch H (2008) Affective mechanisms linking dysfunctional behavior to performance in work teams: A moderated mediation study. J Appl Psychol 93(5):945–958. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.5.945

Collin A (2009) Multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary collaboration: implications for vocational psychology. Int J Educ Vocat Guid 9(2):101–110

Conner ML, Clawson JG (Eds.). (2004) Creating a Learning Culture. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139165303

Crossan MM, Bapuji HB (2003) Examining the link between knowledge management, organizational learning and performance. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Organizational Learning and Knowledge, Lancaster University, Lancaster, 30 May-2 June

Crossan MM, Lane HW, White RE (1999) An Organizational Learning Framework: From Intuition to Institution. The Academy of Management Review, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 522–537. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/259140. Accessed 28 Sept. 2020

Davies H, Walters P (2004) Emergent patterns of strategy, environment and performance in a transition economy. Strategic Manag J 25(4):347–364. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.380

Do H, Budhwar P, Shipton H, Nguyen HD, Nguyen B (2022) Building organizational resilience, innovation through resource-based management initiatives, organizational learning and environmental dynamism. J Business Res 141:808–821

Domínguez-Escrig E, Broch FFM, Chiva R, Alcamí RL (2022) Authentic leadership: boosting organisational learning capability and innovation success. Learning Org 30(1):23–36

Edmondson AC (2002) The Local and Variegated Nature of Learning in Organizations: A Group-Level Perspective. Org Sci 13(2):128–146. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.13.2.128.530

Elbawab R (2022b) University Rankings and Goals: A Cluster Analysis. Economies 10(9):209

Elbawab RRKI (2022a) Predictors and outcomes of team learning in higher education institutions. Dissertation, ISCTE-University Institute of Lisbon

Ellinger AD, Ellinger AE, Yang B, Howton SW (2002) The relationship between the learning organization concept and firms’ financial performance: An empirical assessment. Hum Resource Dev Quart 13(1):5–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.1010

Feeney M, Grohnert T, Gijselaers W, Martens P (2023) Organizations, learning, and sustainability: A cross-disciplinary review and research agenda. J Business Ethics 184(1):217–235

Fiol CM, Lyles MA (1985) Organizational Learning. Acad Manag Rev 10(4):803. https://doi.org/10.2307/258048

Flores LG, Zheng W, Rau D, Thomas CH (2012) Organizational learning: Subprocess identification, construct validation, and an empirical test of cultural antecedents. J Manag 38(2):640–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310384631

Garvin DA (1993) Building a learning organization. Harvard Business Rev 71:78–91

Geng Y, Chen L, Li J, Iqbal K (2023) Higher education and digital economy: Analysis of their coupling coordination with the Yangzte River economic Belt in China as the example. Ecol Indicators 154:110510

Geng YQ, Zuhu HW, Zhao N, Zhai QH (2020a) A New Framework to Evaluate Sustainable Higher Education: An Analysis of China. Discrete Dyn Nat Soc 2020:110514

Guţă AL (2014) Measuring organizational learning. Model testing in two Romanian universities. Manag Marketing 9(3), 253–282. http://www.managementmarketing.ro/pdf/articole/454.pdf

Hart S (1995) A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad Manag Rev 20(4):986–1014

Hayes AF (2013) Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. (2nd ed.). Guilford Publications

Huber GP (1991) Organizational Learning: The Contributing Processes and the Literatures. Org Sci 2(1):88–115. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.88

Hurley RF, Hult GTM (1998) Innovation, Market Orientation, and Organizational Learning: An Integration and Empirical Examination. J Marketing 62(3):42–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299806200303

Iqbal Q, Ahmad NH (2021) Sustainable development: The colors of sustainable leadership in learning organization. Sustain Dev 29(1):108–119

James LR, Demaree RG, Wolf G (1993) r-sub(wg): An assessment of within-group interrater agreement. J Appl Psychol 78(2):306–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.2.306

Jiménez Jiménez D, SanzValle R (2006) Innovación,aprendizaje organizativo and resultados empresariales. Un estudio empírico. Cuadernos de Economía and Dirección de la Empresa 29:31–56

Jyothibabu C, Farooq A, Bhusan Pradhan B (2010) An integrated scale for measuring an organizational learning system. Learning Org 17(4):303–327. https://doi.org/10.1108/09696471011043081

Keskin H (2006) Market orientation, learning orientation, and innovation capabilities in SMEs. Eur J Innovation Manag 9(4):396–417. https://doi.org/10.1108/14601060610707849

Kezar AJ, Holcombe EM (2019) Barriers to organizational learning in a multi-institutional initiative. Higher Educ 79(6):1119–1138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00459-4

Kipesha EF, Msigwa R (2013) Efficiency of higher learning institutions: Evidences from public universities in Tanzania. J Educ Pract 4(7):63–73

Kofman F, Senge PM (1993) Communities of commitment: The heart of learning organizations. Org Dyn 22(2):5–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(93)90050-b

Kontoghiorghes C, Awbrey SM, Feurig PL (2005) Examining the Relationship Between Learning Organization Characteristics and Change Adaptation, Innovation, and Organizational Performance. Hum Res Dev Quarterly 16(2):185–211. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.1133

Kordab M, Raudeliūnienė J, Meidutė-Kavaliauskienė I (2020) Mediating role of knowledge management in the relationship between organizational learning and sustainable organizational performance. Sustainability 12(23):10061

Kumar N (2005) Assessing the learning culture and performance of educational institutions. Perform Improv 44(9):27

Leal Filho W, Tripathi SK, Andrade Guerra JBSOD, Giné Garriga R, Orlovic Lovren V, Willats J (2018) Using the sustainable development goals towards a better understanding of sustainability challenges. Int J Sustain Develop World Ecol 26(2):179–190

Leal Filho, W, Trevisan LV, Rampasso IS, Anholon R, Dinis MAP, Brandli L L, ... Mazutti J (2023) When the alarm bells ring: Why the UN sustainable development goals may not be achieved by 2030. J Clean Prod 407:137108

Leung SO (2011) A comparison of psychometric properties and normality in 4-, 5-, 6-, and 11-point Likert scales. J Soc Serv Res 37(4):412–421

Liao SH, Chang WJ, Hu D-C, Yueh YL (2012) Relationships among organizational culture, knowledge acquisition, organizational learning, and organizational innovation in Taiwan’s banking and insurance industries. Int J Hum Res Manag 23(1):52–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.599947

Maccoby M (2003) The Human Side: The Seventh Rule: Create a Learning Culture. Res-Technol Manag 46(3):59–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/08956308.2003.11671567

Marquardt M (1996) Building the Learning Organization. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY

Marsick VJ, Watkins KE (2003) Demonstrating the Value of an Organization’s Learning Culture: The Dimensions of the Learning Organization Questionnaire. Adv Dev Hum Res 5(2):132–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422303005002002

Massimo B, Nora A (2022) Barriers to organizational learning and sustainability: The case of a consumer cooperative. J Co-operative Org Manag 10(2):100182

Medne A, Lapina I, Zeps A (2022) Challenges of uncertainty in sustainable strategy development: Reconsidering the key performance indicators. Sustain 14(2):761

Meshari AZ, Othayman MB, Boy F, Doneddu D (2021) The impact of learning organizations dimensions on the organisational performance: An exploring study of Saudi Universities. Int Business Res 14(2):54

Mohammad HI (2019) Mediating effect of organizational learning and moderating role of environmental dynamism on the relationship between strategic change and firm performance. J Strat Manag 12(2):275–297. https://doi.org/10.1108/jsma-07-2018-0064

Molnar E, Mulvihill PR (2003) Sustainability-focused organi- zational learning: Recent experiences and new challenges. J Environ Planning Manag 46(2):167–176

Oh SY, Han HS (2020) Facilitating organisational learning activities: Types of organisational culture and their influence on organisational learning and performance. Knowledge Manag Res Pract 18(1):1–15

Örtenblad A, Koris R (2014) Is the learning organization idea relevant to higher educational institutions? A literature review and a “multi-stakeholder contingency approach”. Int J Educ Management 28(2):173–214

Park S, Kim E-J (2018) Fostering organizational learning through leadership and knowledge sharing. J Knowledge Manag 22(6):1408–1423. https://doi.org/10.1108/jkm-10-2017-0467

Pedler M, Burgoyne J, Boydell T (1997) The Learning Company: A Strategy for Sustainable Development, 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill, London. https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/pah-27346?lang=en

Pham Thi Bich N, Tran Quang H (2016) Organizational Learning in Higher Education Institutions: A Case Study of A Public University in Vietnam. J Econ Dev88–104. https://doi.org/10.33301/2016.18.02.06

Pocol CB, Stanca L, Dabija DC, Pop ID, Mișcoiu S (2022) Knowledge co-creation and sustainable education in the labor market-driven university–business environment. Front Environ Sci 10:781075

Rebelo T, Gomes AD (2017) Is organizational learning culture a good bet? An analysis of its impact on organizational profitability and customer satisfaction. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración 30(3):328–343

Rebelo TM, Duarte Gomes A (2011) Conditioning factors of an organizational learning culture. J Workplace Learn 23(3):173–194. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665621111117215

Rhodes J, Lok P, Yu‐Yuan Hung R, Fang S (2008) An integrative model of organizational learning and social capital on effective knowledge transfer and perceived organizational performance. J Workplace Learn 20(4):245–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620810871105

Santos-Vijande ML, López-Sánchez JÁ, Trespalacios JA (2012) How organizational learning affects a firm’s flexibility, competitive strategy, and performance. J Business Res 65(8):1079–1089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.09.002

Santos-Vijande ML, López-Sánchez JÁ, González-Mieres C (2012) Organizational learning, innovation and performance in KIBS.Journal of Management & Organization, 1390–1447. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.2012.1390

Saunders M, Lewis P, Thornhill A (2007) Research methods for business students (4th. Ed.). Pearson education

Schönherr S, Eller R, Kallmuenzer A, Peters M (2023) Organisational learning and sustainable tourism: the enabling role of digital transformation. J Knowledge Manag

Serafini PG, de Moura JM, de Almeida M. R., de Rezende JFD (2022) Sustainable development goals in higher education institutions: a systematic literature review. J Clean Prod 370:133473

Slater SF, Narver JC (1995) Market Orientation and the Learning Organization. J Marketing 59(3):63–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299505900306

Sorakraikitikul M, Siengthai S (2014) Organizational learning culture and workplace spirituality. Learning Org 21(3):175–192. https://doi.org/10.1108/tlo-08-2011-0046

Sun H, Ho K, Ni W (2008) The empirical relationship among Organisational Learning, Continuous Improvement and Performance Improvement. Int J Learn Change 3(1):110. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijlc.2008.018871

Tohidi H, Mohsen Seyedaliakbar S, Mandegari M (2012) Organizational learning measurement and the effect on firm innovation. J Enterprise Info Manag 25(3):219–245. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410391211224390

Voolaid K, Ehrlich Ü (2017) Organizational learning of higher education institutions: the case of Estonia. Learning Org 24(5):340–354. https://doi.org/10.1108/tlo-02-2017-0013

Wahda W (2017) Mediating effect of knowledge management on organizational learning culture toward organization performance. J Manag Dev 36(7):846–858

Watkins K, Marsick VJ (1993) Sculpting the Learning Organization. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA

Watkins K, Marsick V (1997) Dimensions of the learning organization questionnaire. Partners for the Learning Organization, Warwick, RI

Zhang Y, Khan U, Lee S, Salik M (2019) The influence of management innovation and technological innovation on organization performance. A mediating role of sustainability. Sustainability 11(2):495

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RE contributed to all the sections of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All questionnaires collected in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the university and declaration of Helsinki, the questionnaire was previously used in the following dissertation (Elbawab, R. R. K. I. (2022)a. Predictors and outcomes of team learning in higher education institutions. Dissertation, ISCTE-university institute of Lisbon).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.