Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the complex response techniques employed to halt its spread, are both detrimental to mental and emotional well-being. Students’ lives have been damaged by social alienation and self-isolation. These effects must be detected, analyzed, and dealt with to make sure the well-being of individuals, specifically students. This research examines the impact of parent–child relationships, parental autonomy support, and social support on enhancing students’ mental well-being using data collected from post-COVID-19. The Potential participants were students from several universities in Pakistan. For this reason, we chose Pakistan’s Punjab province, with 8 prominent institutions, as the primary focus for data collection. A questionnaire was created to gather information from 355 students. For descriptive statistics, SPSS was used, while AMOS structural equation modeling was used to test hypotheses. The findings revealed that social support on mental well-being (standardized β = 0.43, t = 7.57, p < 0.01) and parental autonomy support was significant and positively related to mental well-being (standardized β = 0.31, t = 5.016, p < 0.01), and predicted parent–child relationships. Furthermore, the parent–child relationship strongly mediated the association between social support, parental autonomy support, and students’ mental well-being. This research proposes that good social support and parental autonomy support improve parent–children relationships and contribute to students’ mental well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

COVID-19 has grown increasingly concerned with mental health and well-being in the past few years. Many research investigations have found that students have higher levels of psychological suffering than the overall people. This psychological tension of this virus among students has had significant and longer-term mental health repercussions, leading to low physical well-being results, including an increase in cardiovascular illnesses and lowly mental health (MH) results. Students suffer from the mental load of this impact more than grownups because they lack the grownup’s ways to cope and physical growth (Rawat and Sehrawat, 2021). Students who have a history of MH difficulties are more likely to suffer MH problems amid a crisis (Gavin et al., 2020). On the advice of the Emergency Committee, the head of the “World Health Organization (WHO)” stated the novel Coronavirus, also identified as “COVID-19”, is a Health Emergency of Worldwide Distress. COVID-19 has catastrophic impacts on the global business environment, schooling, and humanity (Priya et al., 2021). Health professionals designed a complex response plan to stem the spread of COVID-19 from the pandemic’s start. Being isolated or home quarantined was an essential part of the approach. One of the measures authorities have attempted to sluggish the spread of the virus is isolation from society. Isolation from society can affect mental health, increasing symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress (Robb et al., 2020). There has been a surge in the number of students reporting mental health difficulties in the present years at colleges and universities. The underlying explanation might be university students’ inexperience, as they often struggle to handle stress, mainly when confronted with educational, social, and career-related challenges. Following research, the COVID-19 pandemic increases students’ chances of developing unhappiness and suicidality (Xiong et al., 2021). Following the closure of university campuses, students tended to see their educational future as bleak. Isolation from society and a lack of adequate and effective MH assistance exacerbated students’ fragile status. Because of these factors, young individuals pursuing university are now at a higher risk of acquiring MH disorders (Su et al., 2021).

Social support is instinctively understood, but ideas about definitions conflict when specific questions are raised. Family practitioners believe that social support is one of the possible keys to an individual’s well-being, especially for those going through significant life transitions or crises (Kaplan et al., 1977). The definition of “social support” varies usually among those who have studied it. It has been discussed in a general way as support that is “provided by other people and arises within the context of interpersonal relationships” Cooke et al. (1988) and as “support accessible to an individual through social ties to other individuals, groups, and the larger community” (Lin et al., 1979). Parent–children relations are interpersonal interactions formed by the interaction of parents and Child in blood and genetically related families. Parent–children ties are the first social associations to which individuals are exposed. It influences many facets of personality development, social cognition, and mental well-being (Lu et al., 2020). A lower degree of social support, in particular, is connected to greater levels of depressive symptoms (Wang and Peck, 2013). Social support refers to the standard of emotional assistance provided by others.

Furthermore, research shows that social support levels are closely related to measures of reduced stress and psychological discomfort, as well as improved well-being (Wang and Peck, 2013). Nevertheless, most research on youths’ social support focuses on their families, with relatively little research on their peers’ social support (Oktavia et al., 2019). Based on the gaps in existing knowledge, this research intended to determine whether there is a link between parent–child relationships during social seclusion caused by the pandemic and MH. This study additionally explored how social support (SS), parental autonomy support (PAS), and parent–child relationships are related to students’ mental health and well-being. It also looks into the role of the parent–child relationship as a mediator. The outcomes of this investigation are expected to increase understanding of the topic. Despite several research in the field of MH, there is still a literature gap on the roles and linkages of parent–child relationships and their mediator behaviors. This research provides a model for simultaneously investigating the roles and intervening factors. The focus of this investigation is on the following research questions. How can social and parental autonomy support affect students’ MH following COVID-19? How does the parent–children relationship mediate this relationship? Following an exhaustive assessment of the pertinent literature (Akram et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022), it was discovered that numerous research has been conducted to evaluate parents–children relationships and MH-associated issues, but to the best of our knowledge no research has been performed in Pakistan yet to determine the answers to these study topics will be provided utilizing a single theoretical model. Based on the available literature, the present study initially posits that social and parental autonomy support favorably promotes the student’s mental well-being and positively connects with a parent–child relationship in Pakistan. The study also hypothesizes that the parent–child relationship impacts the mental well-being of the students and mediates the connection between social support, parental autonomy support, and mental well-being. The research could have subsequent contributions: To begin, the research provides a detailed and systematic investigation of the concepts of the parents–children relationship, social support, parental autonomy support, and mental well-being. Second, by integrating the parents–children relationship, the study enhances the comprehensive analytical model that investigates the association between SS, PAS, and mental well-being. The model of the research describes the theoretical viewpoint in an innovative manner. Furthermore, the work has both practical and theoretical ramifications.

Literature review

Social support and mental well-being of students

Social support is instinctively understood, but ideas about definitions conflict when specific questions are raised. Family practitioners believe that social support is one of the possible keys to an individual’s well-being, especially for those going through significant life transitions or crises (Kaplan et al., 1977; Wilcox and Vernberg, 1985). The definition of “social support” varies usually among those who have studied it. It has been discussed in a general way as support that is “provided by other people and arises within the context of interpersonal relationships” Cooke et al. (1988) and as “support accessible to an individual through social ties to other individuals, groups, and the larger community” (Lin et al., 1979).

Multiple research investigations have revealed that several internal elements influence young students’ mental well-being, notably the temperament of the students Ypsilanti et al. (2020), parental style Rinaldi and Howe (2012), and peer interaction (Holmes et al., 2016). One of the most significant macrosocial elements impacting students’ mental health is social support, which relates to the subjective and objective support they get from their circle of friends and how they utilize it (Shen, 2009). “Family support, friend support, and other support” are common sources of social support (Dahlem et al., 1991, p. 760). Through social bonding, social support may reduce psychological stress and maintain or enhance a person’s mental and physical well-being (Cohen and McKay, 2020; Tao et al., 2022). Prior studies have found that social support can make parents more positive, enhance their mental and physical wellness, and improve their parenting efficacy (Yan et al., 2023). Once parents believe they have access to support and networks of friends, their psychological well-being rises (Chatters et al., 2015). Parents with higher social support are more nurturing and consistent in their parenting and less likely to use harsh parenting behaviors across a range of child ages Byrnes and Miller (2012), and social support may assist parents in managing how they react emotionally to their kids (Marroquín, 2011). Social support may also give parents developmental knowledge and advice on proper parenting practices, allowing them to adapt to their expectations and enhance their parenting abilities (Ayala-Nunes et al., 2017). A lack of or insufficient social support, on the other hand, maybe an indicator of risk for parental psychological wellness, leading to incorrect parenting behaviors (Belsky and Jaffee, 2015; Hu et al., 2023). Parents with psychological problems have fewer beneficial relationships with their kids, experience more instances of not positive interactions and enmity, express less efficiently, and are less responsive to their children’s actions (Herwig et al., 2004). As a result, parents’ perceived social support influences parenting ideas and conduct, which can impact children’s mental well-being development. As a result, parents’ perceived social support may be favorably related to the mental well-being of their children.

H1: Social support positively related to the mental well-being of students

Parental autonomy support and mental well-being of students

Following the self-determination theory Ryan and Deci (2000), “autonomy” is the fundamental cognitive or emotional need that leads to optimum growth and functioning, for instance, higher levels of educational accomplishment and improved psychological well-being of students (Vasquez et al., 2016). Parental support has been proven in studies to increase autonomy in young people (Inguglia et al., 2015). Parental autonomy support (PAS) refers to parents promoting emerging adolescents’ growing desires for independence, like liberty of expression, pondering, and making decisions (Soenens et al., 2007). Numerous research concentrating on European societies have found that parental autonomy support is connected with positive psychosocial adjustment in individuals (Froiland, 2011; Soenens et al., 2007). An empirical study, for example, has shown that autonomy support in intimate associations is an important predictor of mental well-being (Arslan and Asıcı, 2022; Shamir and Shamir Balderman, 2023). Likewise, Kins et al. (2009) found that PAS is related to greater mental well-being in Belgian young adults. Surprisingly, cross-cultural research found that parental autonomy support is connected to mental well-being in “Chinese and North American” teenagers Lekes et al. (2010), indicating that PAS benefits people working in a group environment.

Furthermore, according to the latest meta-analysis, the parental autonomy support association is greater when it reflects both parents instead of just moms and dads (Vasquez et al., 2016). Accepting this viewpoint, the present research emphasizes PAS. Whereas various research in Western cultures indicates the relationship between PAS and mental well-being, nothing is known about the advantages of “parental autonomy support” in a communal community or the fundamental connection between PAS and mental well-being. Through self-regulatory processes, culture can influence mental well-being, impacting how individuals think, feel, and conduct themselves in pursuit of mental well-being (Siu, Spector, Cooper, and Lu, 2005). Thus, we posit that PAS impacts the mental well-being of university students.

H2: Parental autonomy support positively related to the mental well-being of the students

Mediating effect of parent–children relationship

Parent–children connections are interpersonal interactions formed by the interaction of parents and Child in blood and genetically related families. Parent–children ties are the first social associations to which individuals are exposed. It influences many facets of personality development, social cognition, and mental well-being (Lu et al., 2020). Greater social interaction has been shown to improve parent–children interactions, increase parent–children warmth, and decrease parent–children animosity (Lippold et al., 2018). This might be attributed to two factors. On the one hand, social assistance may significantly enhance children’s quality of family life (Balcells-Balcells et al., 2019; Feng et al., 2022). Parents might have more time to dedicate to parenting, resulting in improved parent–children interactions. On the other hand, social support has been shown to lower parental stress, promote mental well-being, and favorably affect how parents act (Avila et al., 2015; Östberg and Hagekull, 2000). Social support can help parents get good parenting counsel and assistance (Dominguez and Watkins, 2003). Social support may assist parents in managing their feelings about their children, which leads to improved parenting practices and more parental warmth (Byrnes and Miller, 2012). Parent–children relationships and children’s mental well-being are inextricably linked. Parent–children connections are crucial in the development of children. Parent–children connections have a greater influence on the Child than other interpersonal interactions in the family and have a significant impact on the growth of a person’s personality, mental well-being, and adjustment (Nock et al., 2009).

Parent–children attachment and intimacy are significant manifestations of parent–children interactions. In the long run, the continuing emotional link between a kid and a caregiver is known as parent–children bonding. A strong bond is a vital basis for children’s healthy development and integration into society, and parent–children bonds remain stable as adolescents age (Juffer et al., 2012). It has been demonstrated that young people with solid parent–children bonds acquire more beneficial social abilities, have greater cognitive functioning, and have greater mental and physical wellness (Ranson and Urichuk, 2008). Parent–children attachment is the tight, warm relationship between parents and kids, which may be shown in positive interaction behaviors and close sentiments about one another (Chen et al., 2015). According to several types of research, the parent–children connection is the foundation of proper child development and the most consistent safeguard for healthy personal growth (Barber et al., 2005). Li et al. (2022) used the parent–child relationship as a mediator in their study to explore the impact of parental mediation on internet addiction. In a nutshell, students who have close, warm parent–children connections experience less externalizing and internalizing difficulties Lamborn and Felbab (2003), have a lower incidence of suicide ideation Harris and Molock (2000), and have improved psychological well-being. Thus, parent–children relationships may act as a mediating variable between SS, PAS, and the mental well-being of students.

H3: Parents–children relationship mediates the association between social support and the mental well-being of the students

H4: Parents–children relationship mediates the association between parental autonomy support and the mental well-being of the students

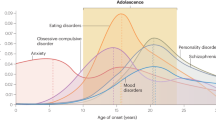

Figure 1 depicts the hypothesized study model. The direct impacts of SS and PAS on the mental well-being of university students were investigated first, followed by studying the other linkages and indirect effects among social support, parental autonomy support, parent–children relationships, and the mental well-being of the students.

Materials and methods

Sampling technique and data collection

The Potential participants were students from several universities in Pakistan. For this reason, we chose Pakistan’s Punjab province, with 8 prominent institutions as the primary focus. Due to Covid 19, it was projected that the majority of the students would remain at home and endure some form of psychological disorder with their families. To gather data on the research variables, we employed a validated questionnaire that was distributed to assistance desks/information desks of the selected institutions for self-rated replies. The datagathering period was from April to May (2023). Data were collected on-site. We used snowball sampling since the datagathering was connected to extremely subtle and individual concerns, such as mental well-being, social support, and parent–child relationships.

Furthermore, we requested assistance from the directorates of student affairs at the respective institutions in determining the target participants. We accompanied the recommendations offered by different scholars, such as those who recommended: “every item must be represented employing five samples,” that “samples of three hundred shall be regarded as appropriate,” who suggested that “the size of it ought to be twenty times bigger than the expected factors,” and who suggested that “N = 100–150” is adequate for conducting SEM (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). Based on these scholars’ suggestions and the usual response percentage, we selected a sample size of 467 out of 355 that were found legitimate (response percentage of 76%). Male respondents comprised 55 percent, whereas female participants comprised 45 percent. Obtained surveys were utilized for research.

Measurement development

Each scale utilized in this investigation was taken and slightly modified from prior studies and had previously been authenticated by the researchers. Teti and Gelfand (1991) established the “Parent–Child Relationship” Scale, which is commonly used to measure the closeness of adolescents to their parents (Chen et al., 2015). It is made up of ten questions that relate to teenagers’ sentiments about their parents. Adolescents in this study were given questions like, “How openly do you talk with your parents?” The questions about perceived friend support were modified, and the sample construct was “I can count on my friends when things go wrong.”

Similarly, the study’s scale constructs of other people’s support were changed, and its example construct was “There is a special person in my life who cares about my feelings.” In this research, we assessed parental autonomy support developed by Soenens et al. (2007). It has five items: “My parents let me plan for things I want to do.” Furthermore, the assessment questions of mental well-being are measured by the five‐item scale of the World Health Organization. This scale was adapted from the study of (De Wit et al., 2007). Its three aspects, namely cognitive, emotional, and psychological health, were altered, and its construct was “I’ve been feeling optimistic about the future.” All of the constructs were measured on a “five-point Likert scale.” The Alpha for social support was 0.93. The Alpha value for parental autonomy support was 0.92. The Alpha for parent–child relationship was 0.90, and for mental well-being was 0.90.

Common method bias (CMB)

Since the data is collected all at once from a single source, bias concerns might surface and cast doubt on the study’s validity. The Harman single-factor test investigated the bias problem (Harman and Harman, 1976). The results demonstrated that each element of the suggested model could be separated into four variables, the first of which only explained 38.78% of the variation. According to this statistical value, normal biases must be lower than 50%. Therefore, our statistical data are free from prejudice.

Data analysis

We used Analysis of moment structures 25.0 to asses study hypotheses utilizing structural equation modeling (Shaffer et al., 2016). We used the two-step SEM technique Anderson and Gerbing (1988) recommended, beginning with CFA, to guarantee model adequacy. After that, an ultimate theoretical model was evaluated to evaluate the connections among every variable. Several fit indicators, such as 2/df, the CFI, TLI, the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), were employed in the confirmatory factor analysis.

Descriptive statistics

The values for the mean, standard deviation, AVE, and Pearson’s correlations for each observed variable are displayed in Table 1. The standard deviations ranged from 0.84 to 1.31, whereas the mean values were 1.43 to 2.94. Table 1 further reveals that the relationships between all variables analyzed are positive and substantial. Table 2 also indicates the DV of every factor for which the numerical values of average variance extracted are greater than the inter-correlational values, and the values of average variance extracted are also higher than 0.5 (Shaffer et al., 2016).

Measurement model

The measurement model in this work was evaluated using CFA Kline (2015), and Table 3 displays the standard factor loadings, Alpha, and CR of each component.

Social support, Parental autonomy support, Parent–child relationship, and mental well-being of students have Alpha of 0.92, 0.91, 0.90, and 0.88, respectively. These alphas exceed the suggested 0.70 threshold (Hair et al., 1998). The standardized factor loadings for Social support ranged from 0.78 to 0.86 for Parental autonomy support, 0.71 to 0.84 for the Parents–children relationship, 0.70 to 0.82, and 0.71 to 0.81 for the mental well-being of students. All factor loadings exceed 0.50 (Hair et al., 1998). The composite reliability (CR) ranges from 0.87 to 0.92 for Social support, Parental autonomy support, Parents–children relationship, and mental well-being of students, which is above the recommended value of 0.60 (Bagozzi et al., 1991).

In addition, we ran a serial-wise confirmatory factor analysis to ensure the model recognized different structures. The hypothesized 4-factor measurement model (Social support, Parental autonomy support, Parents–children relationship, and mental well-being of students) offered an appropriate fit to the data: χ2 = 2693.55, Df = 946, χ2/df = 2.847, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.05 and SRMR 0.04 (Table 3). The hypothesized 4-factor measurement model is the most suitable in each other models in Table 3.

Table 3 shows that all observed items load the respective latent variables significantly. Other CFA models were contrasted with the proposed four-factor model. The validities are demonstrated by Table 4’s fit indices, providing a strong basis for evaluating the proposed four-factor model.

Hypotheses testing

We utilized a thorough structural equation modeling model with maximum likelihood estimation to analyze momentum structures and assess the study’s hypotheses. Simultaneously, hypotheses 1–2 (shown in Table 5) were supported by correlations (provided in Table 1) and SEM findings.

There is a strong positive correlation between students’ mental health and social support, as Hypothesis 1 suggests. Tables 1 and 5 provide the evidence we discovered supporting H1 (standardized β = 0.43, t = 7.57, p < 0.01). According to the second hypothesis, there will be a beneficial correlation between students’ mental health and PAS. With standardized β = 0.31, t = 5.016, and p < 0.01, H2 was supported.

H3 of our research uncovers that the ‘parents–children relationship significantly performs a mediating role in the association between social support and mental well-being of the students.’ Table 6 shows that when parent–child relationships are present, the β coefficient from social support and students’ mental health turns insignificant (β = 0.041; S.E. = 0.060; t = 0.683; CI = −0.061, 1.012), but the indirect beta coefficient has a significant value (β = 0.149; S.E. = 0.063; t = 2.365; CI = 0.337, 0.589). These findings demonstrate the mediating function of the parent–child bond in the association between students’ mental health and social support. The parent–child bond also acts as a mediator in the link between PAS and mental health, according to hypothesis 4. Table 6 shows a substantial mediating mechanism and a significant value for the beta coefficient. For H4, there is a substantial indirect correlation (β = 0.163; S.E. = 0.062; t = 2.629; CI = 0.259, 0.352). Parental autonomy support and mental well-being have a direct link that eventually becomes negligible (β = 0.008; S.E. = 0.060; t = 0.133; CI = −0.001, 0.013).

All formulated hypotheses of our study are accepted.

Discussion

Mental health problems affect 10%–20% of students worldwide. Students’ susceptibility during the COVID-19 pandemic will likely influence this statistic. Poor mental health causes undesirable effects, including suicidal inclinations, behavioral disorders, and psychological abnormalities; hence, studies to remove or decrease the effects of bad mental health are critical. COVID-19 has made the already difficult state of youths and their mental health even more insecure. In the aftermath of a pandemic, the scale of COVID-19 the necessity for excellent research to fight MH concerns has grown exponentially. Keeping this information in mind, we developed our study subject and research questions and included parent–child relationships and linkages with students’ post-COVID-19 mental well-being of the pupils. The current research reviewed the literature on PAS, PSS, and people’s mental well-being after the COVID-19 pandemic. The literature study provided a vision of previous studies on the parent–child connection for mental well-being. According to research, the pandemic and its associated elements, such as quarantine, social isolation, and travel limitations, have been tense for students and other populations. Stress and worry caused by events such as closing schools, joblessness, poor healthcare, and uncertainty in education, job, and individual life have substantially influenced human mental and physical wellness (Pfefferbaum and North, 2020). We chose a paradigm that may serve the literature theoretically and practically, considering the significance of parent–child relationships after the pandemic. Prior study on the parent–child relationship has not investigated their role as a mediating variable in a unified model. The present research covers this gap in the literature by assuming that SS is positively linked with the mental well-being of students. The data analysis revealed that SS is substantially and highly positively associated with mental well-being; hence, H1 is accepted, in line with Cohen and McKay (2020), who discovered that social bonding and social support reduce psychological stress and enhance a person’s mental well-being.

Similarly, H2 investigated the association between parental autonomy support and mental well-being. It is also consistent with previous study findings that parental support has been proven to increase autonomy in young people, ultimately improving mental well-being (Inguglia et al., 2015). Because the conclusions indicated substantial values for each of these variables, H2 was also acceptable.

The mediation analysis was performed to determine if H3 and H4 were accepted or rejected. As previously stated in the findings section, mediating analysis was undertaken to check if the mediator increased the influence of independent variables on the dependent variable. Our research findings uncover that the ‘parents–children relationship significantly mediates the association between SS and mental well-being of the students.’ It can be viewed in the results section that the β coefficient from SS and mental well-being of the students turns insignificant in the attendance of the parent–children relationship, whereas the indirect beta coefficient has a significant value; this exhibits that the parent–children relationship plays a mediating role in the association between social support and the mental well-being of the students. Similarly, hypothesis 4 reveals that the parent–child relationship mediates the association between PAS and mental well-being. Table 6 shows that the beta value is significant, indicating a considerable mediation. The indirect association for hypothesis 4 is substantial, but the direct association between PAS and mental well-being turns insignificant. The H3 and H4 of our study are accepted.

Our findings reveal that all the proposed hypotheses were accepted, implying that SS has a good effect on the mental well-being of students and is related to a positive parent–child relationship. The findings then show that parent–child relationships positively influence mental well-being and play the role of mediating variable in the association between SS, PAS, and students’ mental well-being, which is in line with study findings that show that parent–child relationships mitigate the adverse influences of stress and foster mental wellness (Dam et al., 2023).

Implications

Our findings have far-reaching implications for medical practitioners, research organizations, and healthcare policymakers. Educational organizations should first become more aware of their students’ extra needs and mental health challenges. Future research should include people from various countries and ethnicities as COVID-19 control tactics and epidemic extent vary per country. Finally, the impacts of COVID-19 on students’ mental health have been overlooked. We urge instructors, higher education organizations, and mental health professionals to provide enough assistance to their students through the pandemic. Providing pupils with education to aid them in building self-efficacy, healthy parent–child relationships, and practical tools to cope with problems could help them handle the amplified stress that COVID-19 involves. It has been observed that durable and successful parent–child relationships were quite beneficial in helping pupils manage their stress. Administrators must appreciate MH practitioners’ function in supporting students seeking mental health support. Students’ capacity to tackle stress and create social support can assist them in escaping the harmful psychological impacts of the coronavirus outbreak. As a result, family, friends, and instructors should develop emotional resilience and enhance positive coping strategies among adolescents by adopting theory-tested treatments or programs. Because of constraints such as social isolation and lockdown, these treatments might be carried out in novel modes, for instance, webinars, online courses, and on-demand movies. Inter-professional probing programs and online mental behavior treatment boost students’ endurance and confidence (Schmutz, 2022). Furthermore, increasing social support could offer people a sense of higher psychological stability, reducing their fears and anxiety and helping them to function regularly during the pandemic. If students are urged to directly communicate their experiences and obstacles in their schooling after COVID-19, their morale will grow, and their MH will be preserved.

Limitations and future study

Our study has numerous limitations. For instance, this study relied on quantitative research; future research could use a qualitative or blended methodology to provide more intriguing outcomes. Secondly, the findings of this study were obtained by investigating eight educational institutions in Punjab province. Thirdly, because of the time limitation, we only carried out this study in one provincial unit. This research study might be broadened to other provincial units or nations in the future to generalize the study’s findings. Fourth, we obtained data from eight institutions; next, data from more institutions to be gathered to conduct the study. Finally, the current study included a mediating effect. Still, future studies may focus on using parent–child relationships as moderating variables. We suggest studying the reason for integrating PSS into the cognitive vulnerability model. As a result, new concerns have developed regarding the viability and significance of progressing to an integrative model, etiological paradigms, and innovative prospects for study and practical implementations.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic and the complex reaction techniques to halt its spread harm psychological and emotional well-being. Students’ lives have been damaged by social alienation and self-isolation. These effects must be detected, analyzed, and dealt with to guarantee the well-being of people like students. As a result, the present research sought to examine the influence of parental-child relationships, PAS, and SS in enhancing students’ mental well-being by gathering data from post-COVID-19. Students enrolling in Pakistani universities provided data. A survey for the survey was created to collect information from 355 students. SPSS was used to compute descriptive statistics, whereas AMOS structural equation modeling was employed to test hypotheses. These findings underlined the importance of the parent–child connection in dealing with complicated unfavorable conditions since it influences their mental results, particularly their psychological health. Optimistic and adverse relationships are opposed. Students who utilized primarily constructive relationship mechanisms with their parents experienced less emotional distress than those who employed more detrimental connection mechanisms with their parents (Budimir et al., 2021). Furthermore, the research emphasized the need for social support, such as friends and family, as well as parental autonomy support, in the fight against mental disorders. The findings also revealed that students require not only family support but also help from friends and others to create good relationships with parents to deal with psychological difficulties and stress produced by numerous sources.

Data availability

According to the confidential agreements with the participants, the dataset analyzed during the current study is not publicly available. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Akram AR, Abidin FA, Lubis FY(2022) Parental autonomy support and psychological well-being in university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of autonomy satisfaction. Open Psychol J 15(1):1–8

Anderson J, Gerbing D (1988) Structural equation modelling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull 103(3):411–423

Arslan Ü, Asıcı E (2022) The mediating role of solution focused thinking in relation between mindfulness and psychological well-being in university students. Curr Psychol 41(11):8052–8061

Avila C, Holloway AC, Hahn MK, Morrison KM, Restivo M, Anglin R, Taylor VH (2015) An overview of links between obesity and mental health. Curr Obes Rep 4:303–310

Ayala-Nunes L, Nunes C, Lemos I (2017) Social support and parenting stress in at-risk Portuguese families. J Soc Work 17(2):207–225

Bagozzi RP, Yi Y, Phillips LW(1991) Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Adm Sci Q 15(1):421–458

Balcells-Balcells A, Giné C, Guàrdia-Olmos J, Summers JA, Mas JM (2019) Impact of supports and partnership on family quality of life. Res Dev Disabilit 85:50–60

Barber BK, Stolz HE, Olsen JA, Collins WA, Burchinal M (2005) Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev i–147(8)

Belsky J, Jaffee SR (2015) The multiple determinants of parenting. In: Developmental psychopathology: volume three: risk, disorder, and adaptation. Willey publishers, pp. 38–85

Budimir S, Probst T, Pieh C (2021) Coping strategies and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown. J Ment Health 30(2):156–163

Byrnes HF, Miller BA (2012) The relationship between neighborhood characteristics and effective parenting behaviors: the role of social support. J Fam Issue 33(12):1658–1687

Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Woodward AT, Nicklett EJ (2015) Social support from church and family members and depressive symptoms among older African Americans. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 23(6):559–567

Chen W, Li D, Bao Z, Yan Y, Zhou Z (2015) The impact of parent-child attachment on adolescent problematic Internet use: a moderated mediation model. Acta Psychol Sinica 47(5):611

Cohen S, McKay G (2020) Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: a theoretical analysis. In: Handbook of psychology and health (volume IV). Routledge, pp. 253–267

Cooke BD, Rossmann MM, McCubbin HI, Patterson JM (1988) Examining the definition and assessment of social support: a resource for individuals and families. Fam Relat (3):211–216

Dahlem NW, Zimet GD, Walker RR (1991) The multidimensional scale of perceived social support: a confirmation study. J Clin Psychol 47(6):756–761

Dam VAT, Do HN, Vu TBT, Vu KL, Do HM, Nguyen NTT, … Auquier P (2023) Associations between parent-child relationship, self-esteem, and resilience with life satisfaction and mental wellbeing of adolescents. Front Public Health 1–11

De Wit M, Pouwer F, Gemke RJ, Delemarre-Van De Waal HA, Snoek FJ (2007) Validation of the WHO-5 Well-Being Index in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diab Care 30(8):2003–2006

Dominguez S, Watkins C (2003) Creating networks for survival and mobility: social capital among African-American and Latin-American low-income mothers. Soc Prob 50(1):111–135

Feng Y, Zhou X, Qin X, Cai G, Lin Y, Pang Y, Zhang L (2022) Parental self-efficacy and family quality of life in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder in China: the possible mediating role of social support. J Pediatr Nurs 63:159–167

Froiland JM (2011) Parental autonomy support and student learning goals: a preliminary examination of an intrinsic motivation intervention. Paper presented at the Child & Youth Care Forum

Gavin B, Lyne J, McNicholas F (2020) Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. Irish J Psychol Med 37(3):156–158

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL (1998) Multivariate data analysis. 5th edn. vol. 5, no. 3. Upper Saddle River, pp. 207–219

Harman HH, Harman HH (1976) Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago press

Harris TL, Molock SD (2000) Cultural orientation, family cohesion, and family support in suicide ideation and depression among African American college students. Suicide Life‐Threat Behav 30(4):341–353

Herwig JE, Wirtz M, Bengel J (2004) Depression, partnership, social support, and parenting: interaction of maternal factors with behavioral problems of the Child. J Affect Disord 80(2-3):199–208

Holmes CJ, Kim-Spoon J, Deater-Deckard K (2016) Linking executive function and peer problems from early childhood through middle adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol 44:31–42

Hu J, Chiang JTJ, Liu Y, Wang Z, Gao Y (2023) Double challenges: How working from home affects dual‐earner couples’ work‐family experiences. Pers Psychol 76(1):141–179

Inguglia C, Ingoglia S, Liga F, Lo Coco A, Lo Cricchio MG (2015) Autonomy and relatedness in adolescence and emerging adulthood: Relationships with parental support and psychological distress. J Adult Dev 22(1):1–13

Juffer F, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH (2012) Promoting positive parenting: an introduction. In: Promoting positive parenting. Routledge, pp. 1–10

Kaplan BH, Cassel JC, Gore S (1977) Social support and health. Med Care 15(5):47–58

Kins E, Beyers W, Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M (2009) Patterns of home leaving and subjective well-being in emerging adulthood: the role of motivational processes and parental autonomy support. Dev Psychol 45(5):1416

Kline RB (2015) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications

Lamborn SD, Felbab AJ (2003) Applying ethnic equivalence and cultural values models to African-American teens’ perceptions of parents. J Adolesc 26(5):601–618

Lekes N, Gingras I, Philippe FL, Koestner R, Fang J (2010) Parental autonomy-support, intrinsic life goals, and well-being among adolescents in China and North America. J Youth Adolesc 39:858–869

Li J, Huang J, Hu Z, Zhao X (2022) Parent–child relationships and academic performance of college students: chain-mediating roles of gratitude and psychological capital. Front Psychol 13:794201

Li X, Ding Y, Bai X, Liu L (2022) Associations between parental mediation and adolescents’ internet addiction: the role of parent–child relationship and adolescents’ grades. Front Psychol 13:1061631

Lin N, Ensel WM, Simeone RS, Kuo W (1979) Social support, stressful life events, and illness: a model and an empirical test. J Health Soc Behav (2)108–119

Lippold MA, Glatz T, Fosco GM, Feinberg ME (2018) Parental perceived control and social support: linkages to change in parenting behaviors during early adolescence. Fam Process 57(2):432–447

Lu J, Lin L, Roy B, Riley C, Wang E, Wang K, Zhou X (2020) The impacts of parent-child communication on left-behind children’s mental health and suicidal ideation: a cross sectional study in Anhui. Child Youth Serv Rev 110:104785

Marroquín B (2011) Interpersonal emotion regulation as a mechanism of social support in depression. Clin Psych Rev 31(8):1276–1290

Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, De Girolamo G (2009) Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med 6(8):e1000123

Oktavia W, Urbayatun S, Mujidin Z (2019) The role of peer social support and hardiness personality toward the academic stress on students. Int J Sci Technol Res 8(12):2903–2907

Östberg M, Hagekull B (2000) A structural modeling approach to the understanding of parenting stress. J Clin Child Psychol 29(4):615–625

Pfefferbaum B, North CS (2020) Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med 383(6):510–512

Priya SS, Cuce E, Sudhakar K (2021) A perspective of COVID 19 impact on global economy, energy and environment. Int J Sustain Eng 14(6):1290–1305

Ranson KE, Urichuk LJ (2008) The effect of parent–child attachment relationships on Child biopsychosocial outcomes: a review. Early Child Dev Care 178(2):129–152

Rawat M, Sehrawat A (2021) Effect of COVID-19 on mental health of teenagers. Asian J Pediatr Res (3):28–32

Rinaldi CM, Howe N (2012) Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styles and associations with toddlers’ externalizing, internalizing, and adaptive behaviors. Early Child Res Q 27(2):266–273

Robb CE, De Jager CA, Ahmadi-Abhari S, Giannakopoulou P, Udeh-Momoh C, McKeand J, Ward H (2020) Associations of social isolation with anxiety and depression during the early COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of older adults in London, UK. Front Psychiatry 11:591120

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2000) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol 25(1):54–67

Schmutz JB (2022) Institutionalizing an interprofessional simulation education program: an organizational case study using a model of strategic change. J Interprof Care 36(3):402–412

Shaffer JA, DeGeest D, Li A (2016) Tackling the problem of construct proliferation: A guide to assessing the discriminant validity of conceptually related constructs. Organ Res Method 19(1):80–110

Shamir M, Shamir Balderman O (2023) Attitudes and feelings among married mothers and single mothers by choice during the Covid-19 crisis. J Fam Issue 45(3):0192513X231155661

Shen YE (2009) Relationships between self‐efficacy, social support and stress coping strategies in Chinese primary and secondary school teachers. Stress Health J Int Soc Investig Stress 25(2):129–138

Siu O-L, Spector PE, Cooper CL, Lu C-Q (2005) Work stress, self-efficacy, Chinese work values, and work well-being in Hong Kong and Beijing. Int J Stress Manag 12(3):274

Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, Lens W, Luyckx K, Goossens L, Beyers W, Ryan RM (2007) Conceptualizing parental autonomy support: adolescent perceptions of promotion of independence versus promotion of volitional functioning. Dev Psychol 43(3):633

Su Z, McDonnell D, Wen J, Kozak M, Abbas J, Šegalo S, Cai Y (2021) Mental health consequences of COVID-19 media coverage: the need for effective crisis communication practices. Glob Health 17(1):1–8

Tao Y, Yu H, Liu S, Wang C, Yan M, Sun L, Zhang L (2022) Hope and depression: the mediating role of social support and spiritual coping in advanced cancer patients. BMC Psychiatry 22(1):345

Teti DM, Gelfand DM (1991) Behavioral competence among mothers of infants in the first year: the mediational role of maternal self‐efficacy. Child Dev 62(5):918–929

Vasquez AC, Patall EA, Fong CJ, Corrigan AS, Pine L (2016) Parent autonomy support, academic achievement, and psychosocial functioning: a meta-analysis of research. Educ Psychol Rev 28:605–644

Wang M-T, Peck SC (2013) Adolescent educational success and mental health vary across school engagement profiles. Dev Psychol 49(7):1266

Wilcox BL, Vernberg EM (1985) Conceptual and theoretical dilemmas facing social support research. In: Social support: theory, research and applications. Springer, pp. 3–20

Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Chen-Li D, Rosenblat JD, Rodrigues NB, Carvalho I, Mansur RB (2021) The acute antisuicidal effects of single-dose intravenous ketamine and intranasal esketamine in individuals with major depression and bipolar disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res 134:57–68

Yan Z, Yu S, Lin W (2023) Parents’ perceived social support and children’s mental health: the chain mediating role of parental marital quality and parent‒child relationships. Curr Psychol (12):1–13

Ypsilanti A, Robson A, Lazuras L, Powell PA, Overton PG (2020) Self-disgust, loneliness and mental health outcomes in older adults: an eye-tracking study. J Affect Disord 266:646–654

Funding

This research is supported by the Jiangsu Funding Program for Excellent Postdoctoral Talent (No. 2022ZB643).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AJ, MZ, YW, and ML conceptualized the study; MA and AH conducted the surveys and performed the Analysis; AJ and MZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript; all authors critically discussed the results, revised the manuscript, and have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Jiangsu University Institutional Review Board (No. JUIRB/13178/2023). The survey process and procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Before data collection, all eligible respondents were informed about the aims of the study, voluntary participation, and the right to withdraw at any time without giving any reason. They were also assured of the confidentiality of the information to be collected.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jameel, A., Ma, Z., Li, M. et al. The effects of social support and parental autonomy support on the mental well-being of university students: the mediating role of a parent–child relationship. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 622 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03088-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03088-0