Abstract

Coronavirus and other prevailing viruses continue to remain a health threat and challenge the efforts of institutions to promote vaccination acceptance. The current study’s aim is to propose a conceptual framework explaining the role of individual motivators (such as self-interest and collective interest) in shaping attitudes toward vaccination while emphasizing the pivotal role of institutional trust as a mediator and gender as a moderator. Data were collected via an online panel survey among Israelis (N = 464), and SEM statistics were used to test the model empirically. The path analysis model supports the positive direct effect of collective interest and the negative effect of self-interest. Additionally, it shows an indirect effect through the mediation effect of institutional trust and gender moderation. Therefore, institutional trust may significantly influence self-interest people’s attitudes toward vaccines. Furthermore, since females process information more comprehensively, their developed trustworthiness in institutions has an increased impact on vaccine acceptance. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The coronavirus outbreak has made the world more aware of human interdependence (Milani, 2021). Many countries took proactive measures to control the coronavirus pandemic. They shut down and convinced their residents to get vaccinated to attain herd immunity (Wells and Galvani, 2021), seeking to avoid the danger of a mass outbreak that might cause erosion or even collapse of domestic health systems (Armocida et al., 2020; da Silva and Pena, 2021) and damage to the inner economy (Welfens, 2020). Even though we are in the midst of a new phase in the treatment of COVID‐19, health institutions continue to encourage people to get vaccinated for different purposes. As such, it remains crucial to understand what predicts adherence to preventive behaviors such as vaccine acceptance (Matus et al., 2023).

Individual values, beliefs, and perceptions of society and the self, have significant meaning in forming an individual’s attitude toward vaccination and willingness to be vaccinated (Yang and Huang, 2022). In this context, vaccinations provide individual health benefits by protecting against disease and societal benefits by preventing transmission and enhancing herd immunity (Jones et al., 2022). However, public health policies that promote vaccination to achieve herd immunity can conflict with individual autonomy in managing personal health choices (Tu et al., 2021). As such, this tension between collective and self-interest is highly relevant for understanding public attitudes toward vaccination as policymakers seek to craft public health policies and messages that align with both individual and societal values. Self-interest refers to prioritizing one’s own well-being, while collective interest prioritizes societal-level benefits (Zimand-Sheiner et al., 2022). These values are considered cultural orientations used to interpret COVID-19 prevention behaviors. Specifically, self and collective interests are used in research in the context of psychological aspects (Tu et al., 2021; Tong et al., 2022), public health (Bianchi et al., 2023), and public health communications (Jones et al., 2022), showing that individuals who show a tendency to collective interest are more likely to be vaccinated or take other preventive behaviors. This perspective asserts that there is a direct effect of self-interest versus collective interest on vaccination intention. Additionally, according to certain studies, institutional trust facilitates preventative health behaviors and increases compliance with institutional directions (Peterson et al., 2022; Pummerer et al., 2022), and some found it as a moderator for the effect of factors such as social or political identity on vaccination intention (Dal and Tokdemir, 2022). The inconsistency between these viewpoints necessitates a new evaluation of the impact of motivational factors in light of the importance of institutional trust. In fact, there is limited research that investigates the impact and precise function of institutional trust on the relationship between collective interest, self-interest, and attitudes toward vaccination. By filling in this gap, we will gain a deeper understanding of the complex interaction between individual values, societal benefits, and trust.

Therefore, the aim of the current study is to bridge this gap and, based on expectancy-value theory (EVT) (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975; Ajzen and Fishbein, 2000), to explore the effect of individual motivators (e.g., collective interest and self-interest) on attitudes toward vaccination while investigating the role of institutional trust in the process. Additionally, leaning on the selectivity hypothesis (Meyers-Levy, 1988) that suggests that men and women process information differently, we examine how gender plays a role in this decision-making process, as it directly impacts the processing of information delivered by institutions. Lastly, it is conducted in the Israeli context, where authorities were highly active in widespread vaccination campaigns (Gesser-Edelsburg et al., 2022). The study contributes to the literature on vaccination and can help healthcare professionals and policymakers effectively promote vaccination, considering both individual and societal values.

The effect of collective interest and self-interest tendencies on attitudes toward vaccination

Collective interest (also referred to as altruism) and self-interest (also referred to as egoism) are value orientations that are reflected in personality traits: collective interest is associated with pro-social behavior, while self-interest is associated with actions that serve to benefit the individual (van der Linden and Savoie, 2020; Jordan et al., 2021; Kol et al., 2023, 2024). Collective interest individuals empathize with others without seeking their own advantage, while self-interested individuals seek self-gratification by serving their own self-interests and welfare (Song and Kim, 2019). Social psychology views collective interest and self-interest as construals of the self, based on the degree to which the self is defined in relation to other social beings: collective interest people are mostly interdependent, whereas self-interest people are mostly independent (Markus and Kitayama, 1991; Tu et al., 2021).

In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, previous research suggests that during the crisis, people are more engaged with altruistic messages than egoistic messages (Zimand-Sheiner et al., 2022) and that interdependent individuals are more cooperative than independent individuals in collective cooperation, such as assisting others affected by the pandemic (Au et al., 2023), staying at home adherence (Tu et al., 2021) and increased vaccine acceptance (da Silva et al., 2021; Barbieri et al., 2023). These findings suggest that pro-social behavior is related to self-regulatory ability that enables altruistic people to resist selfish impulses (Cao and Li, 2022) and to empathy, i.e., the ability to imagine what another person’s life is like, which leads to greater social competence (Hajek and Konig, 2022).

The well-established expectancy-value theory (EVT) (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975; Ajzen and Fishbein, 2000) posits that people will behave according to the values they expect to achieve from this behavior. Following this theory in the vaccination context, we should expect that people with collective interests personalities, and values will be inclined to be vaccinated. However, individuals with strong self-interest values and personalities, considering only the consequences of the individual (Arias-Oliva et al., 2021), will be indifferent to community immunity and, therefore, not prone to be vaccinated. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Collective interest is positively related to individuals’ attitudes toward vaccination.

H2: Self-interest is negatively related to individuals’ attitudes toward vaccination.

The mediating role of institutional trust

People trust institutions based on prior experience and knowledge of their prior behavior or, in other words, their trustworthiness (Uslaner, 2002). In previous research, trust in government and other institutions, such as healthcare and pharmaceuticals, has been found to be an important predictor of individual vaccination intentions (Galdikiene et al., 2022; Peterson et al., 2022). Additionally, reliance on legacy news institutions was found to be negatively associated with belief in health misinformation (Wu et al., 2023). Furthermore, people who were confronted with a conspiracy theory regarding the COVID-19 pandemic have been found to have negative societal effects, such as low institutional trust (Pummerer et al., 2022). In addition, research found that institutional trust positively mediates the effect of vaccine information on vaccination attitudes (Zimand-Sheiner et al., 2022) as well as the effect of social identity on vaccination intention (Dal and Tokdemir, 2022). Thus, we suggest that both altruistic and egoistic individuals considering vaccination will take institutional trust into consideration. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3a: Institutional trust mediates the relationship between collective interest and individuals’ attitudes toward vaccination.

H3b: Institutional trust mediates the relationship between self-interest and individuals’ attitudes toward vaccination.

The moderating role of gender

The selectivity hypothesis (Meyers-Levy, 1988; Meyers-Levy and Maheswaran, 1991; Meyers-Levy and Sternathal, 1991) provides a gender-based explanation of information processing disparities based on biological differences between females and males. The theory suggests that males and females process and evaluate information differently (Meyers-Levy and Maheswaran, 1991). Females process information more comprehensively, use multiple sources of information, and engage in detailed cognitive processing, whereas males use heuristics, focus on selected sources, and process data selectively. The selectivity hypothesis is also well supported by the context of information search behavior (Kol and Levy, 2023). The motivation for females in their search for information that reduces uncertainty is psychological, whereas the motivation for males is functional. Taking this perspective into consideration, gendered tendencies are likely to extend to COVID-19 vaccine search behavior. In the case of uncertain vaccine efficacy, females’ comprehensive search strategies may motivate them to access information from various government, public, healthcare, and social media sites since they seek psychological assurances. In contrast, males tend to focus on functional value, so they rely on expert opinions and vaccine websites that emphasize their utility by providing key facts.

Additionally, previous studies assert that females consistently rate risks as more concerning across various hazards than males (Gustafson, 1998) and, therefore, engage in higher levels of information seeking, particularly for new risks like COVID-19 (Campos-Castillo, 2021). Research indicates that information elaborated more comprehensively leads to extensive attitude formation that persists over time, resists persuasion, and influences other behaviors and judgments (Petty et al., 1983; Kitchen et al., 2014).

Since institutional trust is developed through the evaluation and perception of information about institutional past performance (Suh et al., 2012; Godefroidt et al., 2017), we assume that the differences in information processing between males and females will influence the relationship between institutional trust and attitudes toward vaccination. Females are more distressed than males by COVID-19 (Heffner et al., 2021), access more sources as they seek psychological assurances, and elaborate the information more comprehensively. Given the novel risks posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, gender seems to play a significant role in shaping vaccine attitudes (Lin et al., 2021); therefore, we assume a stronger effect of institutional trust on attitude in the case of females. Hence, we hypothesize the following:

H4a: Gender moderates the mediating effect of institutional trust on the relationship between collective interest and individuals’ attitudes toward vaccination. That is, the mediating effect of institutional trust will be stronger for females than for males.

H4b: Gender moderates the mediating effect of institutional trust on the relationship between self-interest and individuals’ attitudes toward vaccination. That is, the mediating effect of institutional trust will be stronger for females than for males.

Figure 1 displays the conceptual model, including the hypotheses.

Methods

Procedure and sample

Data were collected via a survey through a self-administered questionnaire. Participants were randomly recruited by Blueberries, an online access panel survey company, in exchange for incentives to avoid nonresponse bias. This study was conducted in Israel, where internet penetration rates are high, reaching 90.3% of the total population as of early 2023 (Kemp, 2023). Previous research has found that high-quality online panels with demographic profiling can provide meaningful representation for public opinion research (e.g., Ansolabehere and Schaffner, 2014). The Israeli context represents a country in which vaccination campaigns were heavily promoted by the authorities (Gesser-Edelsburg et al., 2022) and conducted successfully (Antonini et al., 2022). The university’s ethics committee of the research team has confirmed that the study meets the conditions set out in the procedure for approving a study that is not a clinical trial in humans. All participants were assured of confidentiality; they were also informed that the survey would last about five minutes, and an agreement to participate was obtained before the survey began.

The sample for this study was limited to adults between 18 and 57 (Gen Z, Y, X) (Lissitsa and Kol, 2021). This age range was selected because these individuals were considered relatively less susceptible to severe COVID-19 outcomes than older adults but faced potential risks from the disease. At the same time, younger and middle-aged adults have been observed in previous research to have higher rates of vaccine hesitancy and rejection compared to older populations (Lazarus et al., 2021). Therefore, concentrating on adults 18–57 allowed us to examine vaccine attitudes among a demographic that faced lower but non-negligible COVID-19 risks while also being prone to vaccine skepticism. The sample included 464 responses; 56% were females and 44% were males. Their ages ranged from 18 to 57 years (M = 36.5, SD = 10.7). The majority of the sample had postsecondary education (75%) and an average income or above (57%).

Measures

The survey questionnaire comprised items and scales collected from validated studies (see Table 1). Where needed, the scale items were adjusted to capture vaccination orientation. Items for attitude toward vaccination were taken from Fu et al. (Fu et al., 2015). Institutional trust items are based on Ervasti et al. (2019) and Zimand-Sheiner et al. (2021). Items for collective interest were taken from Price et al. (1995) and the items for self-interest from Birch et al. (2018). In these survey scales, respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with different statements on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Demographic data were also collected.

Results

Validity and reliability

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to confirm construct validity. The results show acceptable fit for all measurements (χ2 value (150) = 448.15, p < 0.05 (χ2/df < 3); Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.951; Normed Fit Index (NFI) = 0.929; and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.066). All four construct standardized regression estimates were above 0.50, reflecting an acceptable fit of the measures (Hair et al., 2010). The average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) were also calculated and indicated convergent validity (see Table 1). Additionally, by comparing the AVE values with the square of the correlation estimates (maximum shared squared variance, MSV), the AVEs achieved greater values, which means that the constructs’ discriminant validity was confirmed (see Table 2). The above measures exhibit acceptable levels of validity and reliability.

Empirical findings

To examine the research hypotheses, two separate models were constructed, one for collective interest and one for self-interest. In each model, a moderated mediation analysis (PROCESS MODEL 14) (Hayes, 2018) was processed with 20,000 bootstrapped samples (self-interest and collective interest were alternatively added as covariates). We tested three key probes: the direct effect of collective interest/self-interest on attitude toward vaccination, whether this effect was mediated by institutional trust, and whether the mediation was moderated by gender. Therefore, institutional trust was modeled as a mediator, and gender as a moderator of the relationship between collective interest/self-interest and attitude toward vaccination (see outcomes in Table 3).

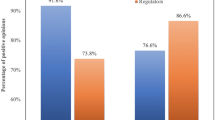

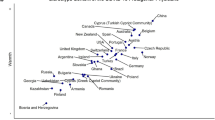

In the collective interest case (see Table 3, model 2 and Fig. 2), the results showed a direct positive effect of collective interest on attitudes toward vaccination (B = 0.15; t = 2.45; p < 0.05). In addition, an indirect effect was mediated by institutional trust. Specifically, collective interest is positively associated with institutional trust (B = 0.19; t = 3.30; p < 0.01), which in turn increases attitudes toward vaccination among females (B = 0.49; t = 7.45; p < 0.01) more than among males (B = 0.27; t = 3.56; p < 0.01). The interaction effect between institutional trust and gender on attitude was positive and significant (B = 0.22; t = 2.18; p < 0.05) indicating that attitude improves for females more than males (see Fig. 3). Overall, the results support the proposed moderated mediation model (B = 0.04; 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.10). Namely, institutional trust mediates the effect of collective interest on attitude for females (B = 0.09; 95% CI: 0.03 to 0.17) more than for males (B = 0.05; 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.10). Hence, H1, H3a and H4a are supported.

In the case of self-interest (see Table 3 model 3 and Fig. 4), the results showed a direct negative effect of self-interest on attitudes toward vaccination (B = −0.15; t = −2.77; p < 0.01). In addition, an indirect effect was mediated by institutional trust. Specifically, self-interest is positively associated with institutional trust (B = 0.16; t = 3.29; p < 0.01), which in turn increases attitudes toward vaccination among females (B = 0.49; t = 7.45; p < 0.01) more than among males (B = 0.27; t = 3.56; p < 0.01). The interaction effect between institutional trust and gender on attitude was positive and significant (B = 0.22; t = 2.18; p < 0.05), indicating that attitude improves for females more than males.

Overall, the results support the proposed moderated mediation model (B = 0.04; 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.09). Namely, institutional trust mediates the effect of self-interest on attitude for females (B = 0.08; 95% CI: 0.02 to 0.14) more than for males (B = 0.04; 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.08). Hence, H2, H3b and H4b are supported.

Discussion

As coronavirus and other viruses continue to remain a health threat, individual motivators determine how we respond to health promotion and disease prevention efforts by government institutions. Following the EVT (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975; Ajzen and Fishbein, 2000) and self-construal (Markus and Kitayama, 1991; Tu et al., 2021) perspectives, this study explores how people’s motivators (collective interest and self-interest) shape attitudes toward vaccination, as well as how institutional trust and gender play a pivotal role in the process. Additionally, the study reflects the Israeli setting where vaccination campaigns were strongly supported by authorities (Gesser-Edelsburg et al., 2022) and carried out successfully (Antonini et al., 2022).

The results of moderated mediation analyses provide evidence indicating two paths of the effects of both motivators, collective interest, and self-interest. Collective interest has a positive direct effect on attitudes toward vaccination, which corresponds with previous studies (da Silva et al., 2021; Barbieri et al., 2023). Interestingly, we also found that collective interest has another indirect positive path through the mediating effect of institutional trust. It is notable that this indirect path differs by gender, namely, that institutional trust has a greater impact on attitudes toward vaccination among females. Previous research has documented that females who do not seek information about vaccines expressed higher levels of fear of vaccination (Paul et al., 2021; Rzymski et al., 2021). This study complements previous research by showing that females are more likely to accept vaccinations if they develop institutional trust. Considering that institutional trust is built over time through past experiences and information elaboration, the results may be explained by the selectivity hypothesis (Meyers-Levy and Maheswaran, 1991). According to this theory, females process information more comprehensively, which may result in a more robust institutional trust, and therefore, its mediated effect on vaccination acceptance is found to be stronger for females.

Self-interest motivation, as expected, has a negative direct effect on attitude toward vaccination and being indifferent to community immunity. This finding adds another perspective to previous research that found that self-interested individuals are less cooperative in stay-at-home adherence (Tu et al., 2021). Surprisingly, self-interest also has an indirect positive effect through the mediating effect of institutional trust. In other words, institutional trust can significantly affect the attitude of egoistic people toward vaccines. Thus, extrinsic motivations such as complying with recommendations from trusted institutions (Ryan and Deci, 2020) might be more influential in regard to getting vaccinated in this case, as opposed to intrinsic, selfish motivations for not getting vaccinated. Moreover, as discussed above for collective interest, this positive indirect path differs by gender, with females showing a greater effect of institutional trust.

Theoretical and managerial implications

The present research offers several theoretical and practical implications. First, this research contributes to the literature on vaccination. It offers a conceptual framework that enhances the understanding of the effect of individual motivators (i.e., collective interest and self-interest) on attitudes toward vaccination. It shows that while interdependent-altruistic individuals demonstrate a positive attitude, independent-egoistic individuals present a negative attitude. However, the main contribution lies in the verification that these differences in motivation can be neutralized through institutional trust to form a positive attitude. Additionally, this path’s magnitude differs by gender. Seemingly, developing female trust is more apparent in predicting positive attitudes. Integrating the selectivity hypothesis into vaccine literature adds a gender perspective to the understanding of the vaccine acceptance process (Kol and Levy, 2023).

Second, it contributes to the literature on self-construal theory. While this theory emphasizes internal motivations as a predictor of behavior, our research indicates that in regard to attitudes toward vaccines, complying with trusted institutions leads to behavior that differs from what the internal motivation predicts. Hence, the present study complements the theory by showing that individual motivators can also influence attitudes through a moderated mediation effect created by trustworthy governmental institutions and individual genders.

Third, this study has implications for policymakers. Institutional trust plays a major role in convincing and refining the effects of personal motivators, softening their effects. As such, policymakers need to cultivate and strengthen trust in governmental institutions. Moreover, since this effect of trust in governmental institutions is higher in females than males, policymakers should concentrate their vaccine efforts on females. Additionally, persuasion efforts should be tailored to the gender being targeted since females and males process information differently. Finally, public health campaigns should be designed to increase trust in government-issued health advice among females.

Limitations and further research

The study was conducted following the COVID-19 pandemic when some people were previously vaccinated against different variants of the virus so that some respondents may base their answers on their past experience. It would be beneficial for future research to examine how this study model differs between people who have been vaccinated in the past and those who have not. Additionally, further studies should be conducted on different vaccines for other epidemics or diseases, such as influenza and papillomavirus, to generalize the model results. Furthermore, while our focus on gender provides an initial look at demographic factors, examining intersections with additional variables like age, education, and ethnicity could reveal important nuances in vaccine attitudes. Cross-national studies could elucidate how gender and vaccine attitudes vary across settings.

Data availability

The data set generated during and/or analyzed during the current study is submitted as a supplementary file and can also be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ajzen I, Fishbein M (2000) Attitudes and the attitude-behavior relation: reasoned and automatic processes. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 11:1–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779943000116

Ansolabehere S, Schaffner BF (2014) Does survey mode still matter? Findings from a 2010 multi-mode comparison. Political Anal 22:285–303. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpt025

Antonini M, Eid MA, Falkenbach M et al. (2022) An analysis of the COVID-19 vaccination campaigns in France, Israel, Italy and Spain and their impact on health and economic outcomes. Health Policy Technol 11:100594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2021.100594

Arias-Oliva M, Pelegrín-Borondo J, Almahameed AA, de Andrés-Sánchez J (2021) Ethical attitudes toward COVID-19 passports: evidences from Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413098

Armocida B, Formenti B, Ussai S et al. (2020) The Italian health system and the COVID-19 challenge. Lancet Public Health 5:e253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30074-8

Au AKY, Ng JCK, Wu WCH, Chen SX (2023) Who do we trust and how do we cope with COVID-19? A mixed-methods sequential exploratory approach to understanding supportive messages across 35 cultures. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01747-2

Barbieri V, Wiedermann CJ, Lombardo S et al. (2023) Age-related associations of altruism with attitudes towards COVID-19 and vaccination: a representative survey in the north of Italy. Behav Sci 13:1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020188

Bianchi D, Lonigro A, Pompili S et al. (2023) Individualism-collectivism and COVID-19 prevention behaviors in young adults: the indirect effects of psychological distress and pandemic fears. J Psychol 157:496–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2023.2250057

Birch D, Memery J, De Silva Kanakaratne M (2018) The mindful consumer: Balancing egoistic and altruistic motivations to purchase local food. J Retail Consum Serv 40:221–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.10.013

Campos-Castillo C (2021) Gender divides in engagement with COVID-19 information on the internet among U.S. older adults. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 76:E104–E110. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa133

Cao Y, Li H (2022) Toward controlling of a pandemic: how self-control ability influences willingness to take the COVID-19 vaccine. Pers Individ Dif 188:111447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111447

da Silva DT, Biello K, Lin WY et al. (2021) Covid-19 vaccine acceptance among an online sample of sexual and gender minority men and transgender women. Vaccines (Basel) 9:1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9030204

da Silva SJR, Pena L (2021) Collapse of the public health system and the emergence of new variants during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. One Health 13:100287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100287

Dal A, Tokdemir E (2022) Social-psychology of vaccine intentions: the mediating role of institutional trust in the fight against Covid-19. Polit Behav 44:1459–1481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09793-3

Ervasti H, Kouvo A, Venetoklis T (2019) Social and institutional trust in times of crisis: Greece, 2002–2011. Soc Indic Res 141:1207–1231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1862-y

Fishbein M, Ajzen I (1975) Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Reading, MA

Fu JR, Ju PH, Hsu CW (2015) Understanding why consumers engage in electronic word-of-mouth communication: perspectives from theory of planned behavior and justice theory. Electron Commer Res Appl 14:616–630

Galdikiene L, Jaraite J, Kajackaite A (2022) Trust and vaccination intentions: Evidence from Lithuania during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 17:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278060

Gesser-Edelsburg A, Hijazi R, Cohen R (2022) It takes two to tango: how the COVID-19 vaccination campaign in Israel was framed by the health ministry vs. the television news. Front Public Health 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.887579

Godefroidt A, Langer A, Meuleman B (2017) Developing political trust in a developing country: the impact of institutional and cultural factors on political trust in Ghana. Democratization 24:906–928. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2016.1248416

Gustafson PE (1998) Gender differences in risk perception: Theoretical and methodological perspectives. Risk Anal 18:805–811. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:RIAN.0000005926.03250.c0

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2010) Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective, 7th edn. Pearson Upper Saddle River

Hajek A, Konig HH (2022) Level and correlates of empathy and altruism during the Covid-19 pandemic. Evidence from a representative survey in Germany. PLoS ONE 17:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265544

Hayes AF (2018) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis, a regression-based approach. Guilford Press, New York

Heffner J, Vives ML, FeldmanHall O (2021) Anxiety, gender, and social media consumption predict COVID-19 emotional distress. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00816-8

Jones C, Bhogal MS, Byrne A (2022) The role of altruism vs self-interest in COVID-19 vaccination uptake in the United Kingdom. Public Health 213:91–93

Jordan JJ, Yoeli E, Rand DG (2021) Don’t get it or don’t spread it: comparing self-interested versus prosocial motivations for COVID-19 prevention behaviors. Sci Rep 11:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97617-5

Kemp S (2023) DIGITAL 2023: ISRAELNo Title. In: DATAREPORTAL. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-israel

Kitchen PJ, Kerr G, Schultz DE et al. (2014) The elaboration likelihood model: Review, critique and research agenda. Eur J Mark 48:2033–2050. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-12-2011-0776

Kol O, Levy S (2023) Men on a mission, women on a journey—gender differences in consumer information search behavior via SNS: The perceived value perspective. J Retail Consum Serv 75:103476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103476

Kol O, Zimand-Sheiner D, Levy S (2024) Let us buy online directly from farmers: an integrated framework of individualistic and collectivistic consumption values. Br Food J 126:1617–1632. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-08-2023-0696

Kol O, Sheiner DZ, Levy S (2023) A (local) apple a day: pandemic-induced changes in local food buying, a generational cohort perspective. European J Int Manag 19:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2023.127297

Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A et al. (2021) A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med 27:225–228. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9

Lin C, Tu P, Beitsch LM (2021) Confidence and receptivity for covid‐19 vaccines: A rapid systematic review. Vaccines (Basel) 9:1–32. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010016

Lissitsa S, Kol O (2021) Four generational cohorts and hedonic m-shopping: association between personality traits and purchase intention. Electron Commer Res 21:545–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-019-09381-4

Markus HR, Kitayama S (1991) Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev 98:224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

Matus K, Sharif N, Li A, et al. (2023) From SARS to COVID-19: the role of experience and experts in Hong Kong’s initial policy response to an emerging pandemic. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01467-z

Meyers-Levy J (1988) The influence of sex roles on judgment. J Consum Res 14:522–530

Meyers-Levy J, Maheswaran D (1991) Exploring differences in males’ and females’ processing strategies. J Consum Res 18:63. https://doi.org/10.1086/209241

Meyers-Levy J, Sternathal B (1991) Gender differences in the use of message cues and judgments. J Mark Res 28:84–96

Milani F (2021) COVID-19 outbreak, social response, and early economic effects: a global VAR analysis of cross-country interdependencies. J Popul Econ 34:223–252

Paul E, Steptoe A, Fancourt D (2021) Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Implications for public health communications. Lancet Region Health—Europe 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012

Peterson CJ, Lee B, Nugent K (2022) COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among healthcare workers—a review. Vaccines (Basel) 10:1–30. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10060948

Petty RE, Cacioppo JT, Schumann D (1983) Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: the moderating role of involvement. J Consum Res 10:135–146

Price LL, Feick LF, Guskey A (1995) Everyday market helping behavior. J Public Policy Mark 14:255–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/074391569501400207

Pummerer L, Böhm R, Lilleholt L et al. (2022) Conspiracy theories and their societal effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 13:49–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506211000217

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2020) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp Educ Psychol 61:101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Rzymski P, Zeyland J, Poniedziałek B et al. (2021) The perception and attitudes toward covid-19 vaccines: a cross-sectional study in Poland. Vaccines (Basel) 9:1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9040382

Song SY, Kim YK (2019) Doing good better: Impure altruism in green apparel advertising. Sustainability 11:5762. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205762

Suh CS, Chang PY, Lim Y (2012) Spill-up and spill-over of trust: an extended test of cultural and institutional theories of trust in South Korea. Sociol Forum 27:504–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1573-7861.2012.01328.x

Tong J, Zhang X, Zhu X, Dang J (2022) How and when institutional trust helps deal with group crisis like COVID-19 pandemic for Chinese employees? A social perspective of motivation. Curr Psychol https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04149-w

Tu KC, Chen SS, Mesler RMD (2021) Trait self-construal, inclusion of others in the self and self-control predict stay-at-home adherence during COVID-19. Pers Individ Dif 175:110687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110687

Uslaner EM (2002) The moral foundations of trust. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

van der Linden C, Savoie J (2020) Does collective interest or self-interest motivate mask usage as a preventive measure against Covid-19? Can J Polit Sci 53:391–397. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423920000475

Welfens PJJ (2020) Macroeconomic and health care aspects of the coronavirus epidemic: EU, US and global perspectives. International Economics and Economic Policy

Wells CR, Galvani AP (2021) The interplay between COVID-19 restrictions and vaccination. Lancet Infect Dis 21:1053–1054. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00074-8

Wu Y, Kuru O, Campbell SW, Baruh L (2023) Explaining health misinformation belief through news, social, and alternative health media use: the moderating roles of need for cognition and faith in intuition. Health Commun 38:1416–1429. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2021.2010891

Yang L, Huang Y (2022) How mortality salience and self-construal make a difference: an online experiment to test perception of importance of COVID-19 vaccines in China. Health Commun 00:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2106413

Zimand-Sheiner D, Kol O, Frydman S, Levy S (2021) To be (Vaccinated) or not to be: The effect of media exposure, institutional trust, and incentives on attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412894

Zimand-Sheiner D, Kol O, Levy S (2022) Help me if you can: the advantage of farmers’ altruistic message appeal in generating engagement with social media posts during COVID-19. Electron Commer Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-022-09637-6

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ariel University Ethics Committee (protocol code AU-SOC-SL-20210324 24.3.21).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kol, O., Zimand-Sheiner, D. & Levy, S. A tale of two paths to vaccine acceptance: self-interest and collective interest effect, mediated by institutional trust, and moderated by gender. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 614 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03070-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03070-w