Abstract

The implementation of the poverty alleviation relocation policy in northwestern minority areas of China has had a significant impact on the production and living spaces of residents. Our investigation and research have shown that the social participation of ethnic minorities is influenced not only by their social and cultural norms but also to a large extent by public policies. China’s policy of relocating people to alleviate poverty has indirectly affected the social participation of elderly ethnic minorities through the relocation of households and the reconstruction of community living spaces and infrastructure. On the one hand, the family production of elders has decreased significantly, while the number of elders participating in housework and leisure activities has increased. On the other hand, although the relocation has accelerated the modernization process in ethnic minority areas, the market work of elders who aged over 50 has not increased much to compensating the job losses. As a result, the overall productivity of the elderly has declined, and their social participation has weakened. Elderly men have been more affected by social changes than elderly women and have borne more adaptation pressures. There are significant differences in leisure activities between elderly men and women. Ethnic and religious activities have remained largely unchanged, while social activities are insufficient and may not promote good health. It is important to encourage elderly individuals, particularly men, to acquire marketable skills and assist them in finding employment. Additionally, promoting social activities for elder individuals can help create a more harmonious community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Relocation is a special poverty alleviation project implemented by China for poor people living in resource-poor areas. At the press conference held by the Information Office of the State Council of China on 3 December 2020, the National Development and Reform Commission announced that China’s relocation task for poverty alleviation in the 13th Five-Year Plan has been fully completed, and more than 9.6 million registered poor residents have moved to new homes (An Bei 2020). The relocation has achieved remarkable results in China, promoting the development of many underdeveloped ethnic minority areas in China. However, from another perspective, the relocation means the overall change, adaptation and reconstruction of the migrant population’s living space, which has brought great challenges (Zhang 2018).

In the relocation process, the elderly are a group with relatively weak adaptability among all age groups, especially the elderly from ethnic minorities. In addition to economic adaptability, they also face social and cultural adaptability problems after relocation. People’s adaptability and psychological state will be shown through their behaviour, and different behaviour will cause positive or negative feedback and have an impact on people’s psychological state. The behaviour of participating in various social activities is a necessary channel for them to settle down, and also a way for them to integrate into the society and get social recognition. Therefore, the social participation of older people is an important indicator that reflects their quality of life, mental health and social adjustment process. If we ignore the social participation of the elderly and neglect their happiness, so that they can only adapt passively, it is obviously a lack of humanitarian care, which is not in line with Chinese traditional values on the life cycle and respect for the elderly, and also contradicts the ethical values of cultural continuity. For Chinese people, the social participation of ethnic minority elders is not only related to the dignity and value of elders, but also to the harmony and stability of families, communities and even the country. Therefore, only by studying the content and changes of social participation of ethnic minority elderly people and exploring the key issues can we propose follow-up policies to promote active ageing and harmonious national development in ethnic areas.

Literature review

Research on social participation

There existed a political and cultural tradition of citizen participation and social participation in Western democratic countries. The study of the relationship between “individual, government and society” has always been an important part of sociology, economics and politics. In the history of the social thought, there are a lot of related academic and opinion debates. Broadly speaking, social participation includes consciousness and behaviour participation in all aspects of society, such as economic, political, cultural and other activities. It emphasizes fairness, justice and openness, and reflects the social power of the people. The concept of social participation put forward by Berger is defined as a type of citizen participation (Berger 2009). In modern society, scholars generally believe that citizen participation including “social participation, political participation and moral participation” is one of the main conditions for achieving democracy and good governance.

With the further deepening of the reform and opening up in the 1990s in China, the people’s demands for public services and social participation has become increasingly strong. To release the finance restrains of local government, other social subjects introduced to jointly undertake public services. At the same time, the academic research on social participation is increasing. Until today, social participation is still one of the hot issues concerned by the Chinese government and society. A considerable number of social management innovation theories and government governance theories have focused on how to use and promote public participation to improve governance efficiency, and study on the content and methods of participation. Most scholars hope to promote Chinese system construction and reform practice by introducing relevant western theories and try to apply them to practice. Until the early 21st century, scholars in China has paid more attention to the content of social participation at the macro level, studying the current situation of social participation and how to promote social participation to improve the government goal, while ignoring the significance of social participation itself at the micro level for citizens(Wang 2015). During this period, many research focused more on roles of various systems and organizations, rather than individual citizens’ attitudes and behaviours during social participation.

In recent years, the research content on social participation has expanded a lot in China, from emphasis on theoretical and institutional changes to specific micro groups or events. In recent years, the research on social participation of the elderly in China has accounted for a considerable proportion. The author searched China Journal Network (CNKI) in 2021 and found that 55.6% of the articles with on social participation included in the title were about the social participation of the elderly group, 19.8% were about social governance, environmental governance and social participation in specific organizations and their roles, 16% were related to education and youth groups, and 8.6% were about the social participation of groups with various diseases. It can be seen that with the development and change of China’s social and economic environment, the aging social problem has gradually surfaced and become a hot issue, which has caused a huge shift in the domestic focus on social participation.

Research on social participation of the elderly

Using the keywords social participation and old, approximately 160 articles were searched in Clarivate Web of Science in January 2024, but most of the literature was not relevant. Most of the relevant literature is about specific methods or factors that influence the enhancement of well-being and health, cognitive functioning, and the reduction of depression in the elderly, and social participation is only an intermediary or intermediate outcome. Very little relevant literature has examined the relationship between social participation in health and psychological state of old people. In relevant sociological research, a combination of interview methods and focus groups are usually used, and in other areas of research, such as medicine and public health, empirical research methods are usually used. Yot et al. (2023) found that mentally abused elderly who participated in social activities were happier than those who did not. Elderly memory was improved by protecting their right to social participation, enriching the style and content of social participation, and ensuring the continuity of their social obligations (Hu et al. 2022). Social participation deserves much more attention as a protective factor for chronic diseases (Holmes and Joseph 2011), was negatively associated with suicidal ideation in the elderly (Yung-Chieh et al. 2005) and mortality (Hidehiro et al. 1994), had a statistically significant effect on life satisfaction(Seok and Noh, 2017), has a positive impact on health (Minagawa and Saito, 2015) and is a promoter of well-being. Pais (2016) examined the importance of work and the promotion and support of the implementation of paid work in older people. Some researchers in China have found that the physical health level of the 60–74 cohort is declining, and the participation of the elderly in social activities is low, which is a weakness in the process of healthy ageing in China (Yang and Meng 2020). Since role performance has the strongest influence on successful ageing, programs should be developed to meet local characteristics and increase opportunities for social participation of the elderly (Park et al. 2013).

In the papers published in CNKI, Chinese scholars usually conduct research on different elderly groups, such as migrant elderly, widowed elderly, rural elderly, urban elderly, etc. Hu and Bei (2020) proposed that the floating elderly have more labour participation in social activities, higher labour participation rate, and lower willingness to participate in voluntary services and community activities. Yao et al. (2020) proposed that the overall social participation of the elderly in China is low, and widowhood significantly increases the participation of the elderly in social activities; the impact of widowhood on the participation of urban elderly is significantly higher than that of rural elderly; and it significantly increases the activity participation of female elderly, but inhibits the activity participation of male elderly. Pan et al. (2021) proposed that visiting or socializing with friends, doing housework, watching TV, listening to the radio and playing chess and cards are protective factors for cognitive function in the elderly of all genders and ages. We found that scholars use different data sources and content to divide the types of social activities of the elderly. Morrow-Howell et al. (2014) used the potential category model to divide the multiple social activities of the elderly into five types: low participation type, medium participation type, high participation type, economic activity type and physical activity type. Zhang and Zhao (2015) divided the social participation activities of young and middle-aged urban elderly in China into five types: work type, social type, leisure and entertainment type, housework type and ordinary type. Xie and Bin (2019) divided the models of social activities of elderly in China into three types: low participation, high participation and family care model by analyzing the four determinants of social participation: personal, social, economic and environmental factors. Wang et al. (2021) defined social participation of elderly as economic participation, political participation, public welfare participation, family participation, internet access and physical exercise. It can be seen that many studies are conducted from the perspective of the state of social participation and the impact on the physical and mental health of the elderly, and few studies are conducted on the social value and social impact of the elderly.

Research on the social participation of elders in ethnic minority or remote areas and gender differences

Some relative studies have addressed the nutrition, health or well-being of older people from ethnic minorities or isolated areas, but there is very little literature that examines the social participation of their older people and its gender differences. Li et al. (2016) found that rural elders had more depressive symptoms than urban elders in China. Marsh et al. (2018) found that social participation in poor, geographically isolated communities in rural Sri Lanka was low, elders has low engagement with organised activities, while attendance at religious activities was common and valued.

Gender division of labour has always been an important issue discussed by academic community and in reality, and we can see it plays an important role in differentiated characteristics in terms of social participation by different genders. Anthropology, sociology and economics analyze the differences, causes and effects of gender division of labour from different disciplinary perspectives, most of these studies are based on the logic of the Western theoretical systems. The theory of evolution in the middle and late 19th century explored gender differences and social division of labour from the natural law of adaptation evolution, and believed that gender differences between men and women were the result of natural selection to adapt to the environment. Women always lagged behind men in physical and psychological characteristics. Evolutionary psychology explains the adaptability of human behaviour through the psychological mechanism of evolution. The desire for survival and reproduction urges human beings to constantly explore new division of labour, which is the most original power of gender division of labour; the difference of gender division of labour is the result of individual selection in the process of human evolution (Chen 2017). Marxism explores the division of labour between men and women with the method of class analysis, and believes that the capitalist reproduction relationship has laid the foundation for the division of labour between men and women, and the transfer of labour force in modern society has enhanced the economic and social status of men. The double burden of work and housework makes female workers physically and mentally exhausted, and strengthens the dominant position of men in the labour market. Thus, the hierarchical division of family labour is perpetuated by the labour market (Shi, 2021). Gender theory proposes that gender differences are deliberate fostered and constant strengthened by family and society in the process of individual socialization, and are the result of social and cultural norms. The field of women’s community participation not only includes communities, but also extends to families and markets. Women’s income changes and gender awareness will affect their community participation (Hanyu 2020).

The process of emancipating Chinese women’s thinking began during the Republican period with the introduction of modern Western thought. The idea of gender equality was further reinforced after the founding of New China, as exemplified by the prominent slogan “Women can hold up half the sky”. This phrase, associated with the women’s liberation movement led by the Communist Party of China (CPC), marked a significant shift in the status of Chinese women in the social, cultural, and public spheres by highlighting their contribution to the construction of socialism. The Chinese women’s liberation movement aimed to liberate women’s minds and promote gender equality. However, it also disregarded femininity and imposed male standards on women. Therefore, the concept of equality between men and women can often place a double burden and pressure on women in both society and the family. This is due to the belief that women who do not perform well in social work are “have no confidences” and may lose their equal status in social and family life. Similarly, there are disparities in women’s social status and imbalances in development between urban and rural areas. In urban China, parents place great importance on educating girls due to the thorough implementation of the one-child policy (1979–2015) in cities. They hope that their daughters can secure good jobs and achieve parity with their male counterparts. While in certain backward rural areas and ethnic minority areas, there are often different preferential policies on childbearing that allow ethnic minority families to have two or more children. They are also less influenced by the modern cultures; as a result, the parents have different expectations of girls in these areas compared to urban areas, they tend to be more influenced by traditional Chinese thinking and expect women to take on more responsibility in the domestic sphere.

Successful aging is a multidimensional and complex concept that exhibits gender heterogeneity, participation in social activities with friends and family is a important factor (Tyrovolas et al. 2014). Due to the traditional culture of dualistic division of labour in undeveloped areas, domestic work and cultural constraints often prevented older women from attending organised activities (Li et al. 2011). At any age, the social participation of Chinese elderly women was lower than that of elderly men, and this gap widened with age. Social participation of older women was more vulnerable to economic conditions. Living with children had a significant negative impact on the social participation of elderly women and there was no significant gender difference in the influence of marital status and educational level on the social participation of the elderly (Zhong and Jing 2022). Retirees show a gradual decline in the frequency of meeting friends and an abrupt decrease in the frequency of attending a social gathering, compared to their working peers. These trends are much stronger for men than women, and compound pre-existing gender differences in social participation (Lim-Soh and Lee 2023).

Deficiencies in previous researches and innovation of this paper

There are relatively more studies on social participation and gender division of labour in the existing literature. However, there are relatively fewer studies on the social participation of ethnic minority elderly people and their gender differences, as well as the impact of migration or changes in living space of on their social participation. The existing literature reveals interesting findings on the social participation and gender differences of ethnic minority elders in specific marginal areas. Religious culture, family responsibilities, and the gender division of labour at work tend to show differentiated impacts on the social participation of the elderly in different geographic and cultural contexts. Social participation tends to shift differently in various socio-historical and cultural contexts. There is a lack of both empirical and qualitative research in this area.

This study is based on the implications of national policy of poverty alleviation and relocation in China. The policy has significantly altered the production and living spaces of residents in many underdeveloped areas, thus greatly affecting the content of social activities and participation of elderly ethnic minorities. The research indicates that social participation can be influenced by specific policy measures and the policy of poverty alleviation relocation has played a significant role in social participation. On one hand, it has improved the living environment of western minorities in China, which may lead to increased market involvement and social participation. On the other hand, it also had some negative effects on social participation, particularly for minority elders. The study enhanced the research on social participation among disadvantaged groups and gender differences, as well as the effects of immigration policies and their impacts, and proposed measures for subsequent improvement.

Research methods, policy background and sample description

Research methods and models

Research methods

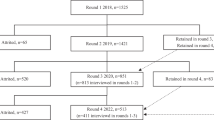

This study conducts field research on relocation sites for poverty alleviation in underdeveloped ethnic minority areas in northwestern China. Typical relocation communities were selected for comparative and qualitative research based on the obtained data.

Firstly, the research team obtained data on the distribution and size of relocation sites in ethnic minority areas at municipal and county levels from relevant government departments.

Secondly, we conducted interviews with community directors (or community committee cadres recommended by the directors) in the relocated communities; most of interviewees were males and have been in charge of their community for more than one year. We aimed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the specific information related to the migrant community, including the background and scale of the relocation, the government’s relocation policy and enabling measures. And obtain the information about the housing situation, the demographic characteristics of the relocated residents, the difficulties faced by the residents during the relocation process and in their production and daily life, the economic development situation, etc.

Household surveys were conducted within the families of the community. Random interviews were conducted in public places within the community. The household survey questionnaire mainly covers the basic situation of individuals and families, changes in production and lifestyle after relocation, the status and adaptation of individuals and family members, and the specific content and participation in various types of social activities. Random interviews mainly focus on the residents’ lifestyle and psychological state. By means of observation, interviews, and questionnaires, we have gained a comprehensive understanding of the changes in social participation among ethnic minority elders after relocation. We will discuss the causes of these changes and explore the social issues reflected in the changes in personal behaviour.

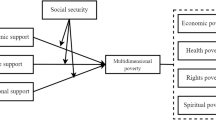

Theoretical model

This research combines the labour participation theory and social participation theory to build a research framework. We often divide work into two types: household work and market work or paid work in the model of Labour Economics. Although in some cases family work didn’t been paid, it make obvious benefits for family, so it often be classed as market work or paid work and is regarded as valuable. And generally people don’t classify household work as paid work. So in many societies especially in traditional societies, market work or paid work is often the most important channels for individual’s socialization and social participation.

According to the social environment of ethnic minorities in Northwest China, we divide the social activities of the elderly of ethnic minorities into three major parts: family production activities, market work activities, and household work and leisure activities. Among which family production activities include traditional agricultural and animal husbandry production activities. And we use market work participation situation and family labour participation situation to describe social production activities. We hope that changes in the content of various social activities can reflect the impact of relocation on the lives of the elderly. And reveal the social participation of the elderly by analyzing and studying the changes in the structure and content of social participation activities of the elderly.

Policy background

Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, poverty has been a persistent issue that has evolved through five stages of development: widespread poverty, rural poverty, concentrated regional poverty, poverty among special groups, and latent and recurring poverty. As China’s urban-rural divide remains unbroken in many areas, the per capita disposable income of rural residents has consistently remained in the middle to lower range of the overall population. Additionally, poverty rates are highest in rural areas of less developed regions. Figure 1 below shows the distribution of income by province. The per capita disposable income of rural residents in Shanxi, Guangxi, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, and Ningxia is presented. In 2016, the per capita disposable income of rural residents in Gansu and Xinjiang was below the middle-income line for rural residents in the entire country. Specifically, the per capita disposable income of rural residents in Gansu was below the lower-middle-income line for farmers in the entire country (Sun and Tim 2019). Gansu Province is situated in the interior of Northwest China, at the intersection of three major plateaus: the Tibetan Plateau, the Inner Mongolian Plateau, and the Loess Plateau. Its complex and diverse topography makes it one of the most ecologically fragile regions in China. The province comprises 14 cities (prefectures), including two ethnic autonomous prefectures. The region suffers from weak infrastructure, underdeveloped social services, and significant poverty issues. The per capita disposable income of urban residents and the per capita net income of peasants have been among the lowest in the country for decades. Additionally, several economic indicators have shown significantly low ranking. In 2020, the annual GDP was ¥901.67 billion (Gansu Province National Economic and Social Development Statistics Bulletin in 2020, 2021), with more than 25 million people there.

Between 1986 and 2010, the goal of policy for poverty alleviation in China was to solve the basic survival needs of “food, clothing and housing”; in 2008, the absolute poverty line was ¥785 per capita net income. Since then, the poverty standard has been raised several times, with the standard after 2010 being classified as the standard of stable subsistence. The poverty standard was set at ¥2300 per person per year in 2011, ¥2855 in 2015, and ¥3218 in 2019, according to the price level of the corresponding year (Wu and Qian 2023). In 2020, it was set to be around ¥4000 (Zhang 2019). In 2015, the State Council issued the Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on Winning the Battle of Poverty Alleviation. This decision designated relocation for poverty alleviation as the top priority in the battle against poverty. Subsequently, each province prepared its own implementation plan. In the process of lifting people out of poverty, it is necessary not only for their incomes to reach the appropriate level but also to ensure “two no worries, three guarantees”: no worries about food or clothing and guarantees of compulsory education, basic medical care, and housing security. The Chinese Government has invested a great deal of money and manpower in the construction and promotion of the policy of poverty alleviation and relocation. The government aims to improve the living and production conditions of impoverished households by relocating migrants. This will help achieve national goals such as eradicating family poverty, integrating modernisation, and promoting ecological and environmental protection. Elderly people, as those who move with their families, are not the focus of policy attention, and most of the policy’s assistance to the elderly population has been in the form of the construction of medical and health facilities and the provision of more medical services.

In line with the Gansu Province’s ‘13th Five-Year’ (2016–2020) Plan for Poverty Alleviation Relocation (2016), Gansu Province will rely on central villages, small towns, industrial parks, and state-owned forest farms that are in better condition to implement relocation for poverty alleviation. The construction of relocation sites is financed through a combination of sources. These include the central budget, special construction funds, debt financing by local governments with interest subsidies from the central government, and self-financing by residents. The self-financing portion is typically limited to ¥10,000 per household or ¥3000 per person. However, widows, widowers, orphans, and other groups facing special difficulties may be exempt from self-financing (Hundred Questions and Answers on the Work of Poverty Alleviation Relocation in the New Era (III), 2019). Relocated households are required to sign the Agreement on Relocation for Poverty Alleviation and the Agreement on the Vacation of Old Residential Base for Poverty Alleviation Relocation with the local government, and their original houses were demolished and relocated. (Hundred Questions and Answers on the Work of Poverty Alleviation Relocation in the New Era (I), 2019) Through the construction of relocation sites for poverty alleviation, the living conditions of the residents were significantly improved, and they were relocated to relatively concentrated, conveniently accessible, and environmentally friendly areas, and the poverty alleviation work was a great success (Shen 2020).

Description of study samples

Sample selection

The aim of this paper is to examine the residents of Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture (See Fig. 2) in Gansu Province who were relocated to alleviate poverty during the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020). Linxia Autonomous Prefecture is one of the most impoverished areas in China, and its eight counties are the main focus for poverty alleviation and development in the Liupan Mountains Concentrated Continuous Difficulties Area (CCTDA). As of the end of 2013, it had a population of 563,200 recorded individuals, with a poverty incidence rate of 32.5%. The province identified 412 villages as deeply impoverished. During the Thirteenth Five-Year period, Linxia Prefecture had carried out various poverty alleviation efforts resulting in the successful eradication of poverty among its residents. (Gansu held a series of conferences on striving for overall prosperity and fighting against poverty -Linxia special session, 2020).

The research team selected two typical relocation sites for poverty alleviation in Linxia Prefecture, Gansu Province. The communities had a registered population of approximately 13,000 in 2020, including 2498 individuals aged 51 and over. The research team conducted household surveys and focus interviews to investigate the social participation of elderly ethnic minorities after relocation and any gender differences. The majority of residents in these two poverty alleviation relocation sites originate from the agricultural population within the county. The original homes were lack of public transport, and were located in mountainous areas within 50 kilometers of the relocation sites. They voluntarily moved from the remote and less densely populated hills to the newly centrally constructed communities after the government’s propaganda and mobilization.

The age division of elderly ethnic minorities

The definition of elderly in China generally starts at 60 years old. However, definitions of elderly vary across societies. Retirement is often considered a sign of entering old age in modern society, while some developed Western countries use 65 as the dividing point. In traditional Chinese society and some underdeveloped regions of China, people over 50 years old or those who have become grandparents are generally considered to be entering old age. In many ethnic minority areas in northwest China, early marriage and early childbearing are prevalent due to a lack of modernization or a short time since entering modernization. The traditional Chinese concept of considering someone over 50 years old or a grandparent as elderly is still prevalent in their society.

It is worth noting that women in ethnic minority areas are expected to marry and start a family after the age of 16. The survey revealed that many residents over the age of 40 have grandchildren. However, it was also discovered that numerous enterprises in these areas do not hire new workers over the age of 50. Therefore, this study classifies individuals aged 51 and above as elderly, dividing those aged 51 to 60 into the “early old stage” and those aged 61 and above into the “official old stage”. The study aims to investigate the social participation problems faced by ethnic minority elders in a changing social environment.

The social participation of ethnic minority elderly

The social activities of elderly individuals from ethnic minorities can be divided into three major categories: family production activities, social production activities, and household and leisure activities. The following text describes the results of these activities.

The dramatically drop of the family production activity and the substantial increase in manual market work, household chores and leisure activity

Data on family production content was obtained through interviews conducted in July 2021. A total of 160 households were visited, 90 in Community A and 70 in Community B, with valid data collected from 156 families. These families have a total of 748 registered residents, including 156 individuals aged over 51. The interviews revealed significant changes in the family production activities of the elderly in the surveyed minority areas following relocation. Prior to relocation, elderly individuals from ethnic minorities primarily engaged in family production activities, such as farming and breeding. However, after relocation, these activities decreased significantly. This was due to the fact that the original cultivated land was far away and could not be cultivated, and the new community did not permit breeding. The labour activities of elderly ethnic minorities have shifted from family-based productive activities, such as planting and breeding, to part-time market work or household chores. The proportion of labour types underwent significant changes, with a decline in planting from 28% to 4% and breeding from 14% to 3%. As a result, the total family production activity decreased from 42% to 7%, a drop of 35% of total elders. On the other hand, there was a significant increase in manual market work, household work, and leisure activity, which increased by 13%, 9%, and 11%, respectively. Additionally, there was a 2% increase in public employment.

The labour participation rate of market work dropped rapidly on the “early elder stage” and “official elder stage”

Based on employment data for the first half of 2020, the labour force participation rate of elderly ethnic minorities in the “early old stage” (i.e. between the ages of 51 and 60 years) decreased significantly in both Communities A and B. The labour force participation rates for the prime-age labour force are 73.5% and 64.6% in Communities A and B, respectively. In the stage of early old age, between the ages of 51 and 60, the rate of labour force participation declines significantly. In Community A, the rate drops to 57.3% for 51-year-olds and 39.7% for 60-year-olds. In Community B, the rate is 61.7% for 51-year-olds and 33.3% for 60-year-olds. Between the prime of life and the age of 51, the labour participation rate of the elderly decreased by 16.2% and 2.9% in the two communities, respectively. From the age of 51 to 60, it decreased by 17.6% and 28.4%, respectively.

The labour force participation rate also declined significantly during the “formal old stage” between the ages of 61 and 70. The labour participation rate for ethnic minority older people in Community A decreased from 33.8% for 61-year-olds to 7.4% for 70-year-olds during this stage. In contrast, Community B had the highest labour participation rate for 61-year-olds at 17.6%, but the rate for 69-year-olds had already dropped to 0. Between the ages of 61 and 70, the labour participation rates for older people in the two communities declined by 26.4% and 17.6% respectively. In contrast, Community B had the highest labour participation rate for 61-year-olds at 17.6%, but the rate for 69-year-olds had already dropped to 0. Between the ages of 61 and 70, the labour participation rates for older people in the two communities declined by 26.4% and 17.6% respectively.

It can be seen that the labour participation rate in the job market decreased significantly during both the “early old stage” and the “official old stage” of the elderly.

Types of leisure activities and its engagement of the elderly

According to the survey, the majority of elderly individuals believe that the number of ethnic and other cultural activities in the community has not changed much after relocation. Additionally, the engagement in ethnic cultural activities is significantly higher than that of other leisure activities. Specifically, 57.7% of elderly individuals often participate in ethnic cultural activities, while only 12% often participate in other leisure activities. The survey results indicate that 83% of the elderly do not believe that there are any spontaneously organized activities in the community. Regarding activities organized by the community council, 17% of the elderly believe that there are none, 50% believe that there are few, 29% believe that they are ordinary, and only 4% believe that there are enough activities. The elderly reported that the most community activities they participated in were religious activities, followed by recreational activities, and the rest activities were seldom attended such as political learning, training activities, environmental protection and other activities organized by the community.

The overall social participation of the elderly has dropped largely after the relocation

In both community A and community B, we found that the trend of labour participation rate of elders is consistently declining. For the ethnic minority elderly who have entered the “early old” age stage of 51, their labour participation rate has decreased significantly compared with the prime stage or the mature stage. Although we haven’t got the data of labour participation rate of all residents before the relocation, but as we interviewed the households and the community officials, we can see many of elders have worked in farm lands and animal husbandry before they relocated, they haven’t got much paid work, and so they no need to have a rapid withdrawn from work as they came to the age of 50’s or 60’s, they can flexibly arrange their labour time as they wish. But after the relocation, we can see that the work of farm and breeding work dropped from 42 to 7% after relocation, and the 7% was included a large part of paid farm and breeding work which will face unfavourable market environment when they are aging. The overall labour participation has also dropped from 51 to 31%. So we can conclude that after the relocation the labour participation of the elderly has dropped dramatically.

As the overall production activities of elderly have declined and the leisure activities have not changed much, so the overall social participation of the elderly has dropped largely after the relocation.

The characteristics of ethnic minorities have no direct influence on social participation

The social participation of the elderly is not directly influenced by the characteristics of ethnic minorities. In our survey of elderly individuals from ethnic minorities, none reported feeling isolated or experiencing social participation issues due to their ethnicity. Additionally, none of the elderly participants mentioned being treated unfairly or differently because of their ethnic background. Elderly ethnic minorities report that most residents in resettlement communities are from their own ethnic groups, same as before. They do not experience any production or living problems or contradictions caused by different ethnic characteristics or groups. For ethnic minority residents who are neighbours of different ethnicities, such as Han Chinese, the racial differences described by the minorities are only some personal characteristics, such as “Han Chinese got flexible thinking” and “Han Chinese got more market experience”. So the minorities believe that Han Chinese have more job opportunities and higher income just because of their personal characteristics. The income and occupational disparities among these ethnic groups were not directly linked to their ethnic identities, but rather to other labour market characteristics such as age and skill level.

Gender differences in social participation of ethnic minority elderly

In modern industrialized society, men and women have equal opportunities for social production. Men also participate in domestic work, and family production activities are relatively small. However, in the ethnic minority areas of north-west China, there were more family production activities and fewer opportunities for social production before relocation. Women have long been disadvantaged in the social division of labour, having more children than women in urban areas, doing almost all the housework and not being much influenced by the women’s liberation movement. After relocation, the production activities and living environment of the residents in the ethnic minority areas have changed significantly, with different effects on the social participation of older men and women.

Elderly men’s productive activities were affected more

The household survey data indicates that among elderly individuals from ethnic minorities, men have predominantly engaged in productive activities. This includes traditional planting and breeding, as well as business and paid work. Prior to the relocation, men were primarily engaged in productive activities or paid work, such as public officials, planting, breeding, business, and manual labour, accounting for 66% of the total male elderly engaged in these activities. In contrast, women only accounted for 33% of those engaged in such activities. Following the relocation, the number of men engaged in the five activities accounted for 43%, a decrease of 23% compared to before the relocation. The proportion of women engaged in these activities was 15%, a decrease of 18% compared to before the relocation. Overall, the work activities of both elderly men and elderly women decreased. However, the work activities of elderly men were more affected by relocation.

The data reflects a situation that is consistent with the overall impression gathered from interviews conducted in the communities. Many elderly people report that they are still capable of working and have a desire to work. In the past, they were able to engage in courtyard economy activities such as planting and breeding. After the relocation, the traditional production conditions have worsened or disappeared, and the original working model cannot continue. At the same time, they are also limited by age and skill when they go out to find a job. Therefore, it leads to the situation of a lot of involuntary unemployment and forced leisure time.

The sense of social participation decreased significantly by some male elderly

The survey revealed that the social participation of ethnic minority elderly is influenced by both cultural traditions and economic factors. Those with a higher economic status tend to participate more in social affairs.

As previously mentioned, there has been a long-standing traditional gender division of labour in the ethnic minority areas of Lin Xia Prefecture. Men’s social status and participation in society are primarily based on their productive activities. Therefore, work is crucial to men’s sense of social participation and is an important component of it. Following the relocation, the traditional work of the elderly ethnic minority, such as breeding and planting, has decreased overall. Additionally, the instability of market work has led to a decline in the social participation of elderly men. Paid work is not only a crucial factor for a sense of social participation but also serves as a foundation for attending other social activities. During the interview, it was discovered that many elderly men experience anxiety, with some describing themselves as having “nothing to do” and feeling very anxious. This is due to the fact that in traditional agricultural societies, men are dominant and often perform heavy manual labour, serving as the backbone of the family. As a result, when the social production activities of elderly men are reduced, their social and psychological well-being is significantly impacted. As traditional family life’s main pillar, elderly men faced dual pressure from both family and society when their work time decreased. This led to increased psychological discomfort and a diminished sense of social participation. In the long run, this could harm their enthusiasm for social engagement.

Elderly men have higher attention to social affairs while elderly women are not

As elderly men participate less in productive activities, they tend to focus on other social affairs. It was observed that male elderly individuals from ethnic minorities pay more attention to social affairs and are more knowledgeable about relocation policies. They prefer to gather and discuss new policies or exchange views on social affairs, while elderly women do not. The proportion of outworkers among ethnic minority elderly women is very small; they prefer to stay near the community to find part-time jobs that can give consideration to their families. During the community interview, the female elderly of ethnic minorities we contacted paid more attention to household chores and did not comment on the relocation policy or livelihood issues of poverty alleviation. In the home interviews, the investigators found that most of the answers of elderly women about the economy and the policy were “unclear”. Most elderly women in the family are only responsible for internal household affairs. They think that social affairs should be undertaken by men, women do not need to worry about social affairs or know the public policies.

Leisure activities of elderly men and women are significantly different, and the activities are not so healthy and enough

According to the interview, leisure activities such as minority religion activities still exist as before. It is mainly men who go to temples for social religious activities. The frequency of the elderly going to the temple varies from person to person, which is related to their leisure time and initiative. Some people go to the temple once a month and some people go once a week. Many people say that they will go when they have time and not tired. And other leisure activities are deficient and lack of engagement. After dinner, the male elderly people often gathered in the public space of the community, most of whom are unemployed male elderly people. They will chat, play cards, and roast about the difficulties after the relocation and their dissatisfaction with the implementation of the relocation policy.

Women’s leisure activities are mainly in the community spaces such as poverty alleviation factories and the square within the community. Social participation has increased as women have gained more paid work in or around the community. However, as elderly women have less paid work and the jobs provided by poverty alleviation factories supported by the government are insufficient, resulting in limited social participation. Additionally, many elderly women are occupied with household chores within their families. They have used to spend their leisure time with neighbours and relatives, however, they are not very familiar with their neighbours after the relocation as they mentioned; and with the increase in the number of migrant workers going out for work, there are fewer opportunities for social interaction in the community. So we can see that there were not enough active and healthy leisure activities for both elderly men and women.

Conclusions and suggestions

Conclusions

Firstly, the study demonstrates the significant impact of public policy in China and its indirect effects, highlighting the social participation challenges faced by ethnic minority elderly individuals in a time where traditional values intersect with modernity. We discovered an intriguing phenomenon: although the purpose of the relocation is to increase income, it is challenging for individuals over 50 years old to integrate into the modern production sector and boost their earnings. Our findings indicate that economic problems are the primary cause of social participation issues among elderly ethnic minorities in Dongxiang County. The elderly face a reduction in traditional production activities and are often excluded from the labour market. This results in a serious waste of human resources, particularly for families in less developed areas. In traditional rural societies like Linxia in Gansu, elderly people over the age of 50 are crucial members of the labour force and do not retire even after reaching the age of 60, They would continue to work for their families until they are unable to do so.

Secondly, relocation for poverty alleviation has led to other social participation issues and psychological problems for the elderly. The gradual withdrawal of ethnic minority older persons from productive labour in traditional agricultural societies, and the slow decline of social participation in line with their declining physical condition, is a natural and gradual process of ageing and reduced social activity. In contrast, the modern productive sector often leads to an abrupt end of retirement after the age of 60 or loss of work, resulting in a sudden reduction of social participation. Elderly ethnic minorities, who are heavily influenced by traditional culture, may find it challenging to adapt to this relatively sudden change after relocation. Many elderly men experience greater psychological stress due to their traditional social division of labour and directly confronted with the competition of modern society, which can impair their sense of social participation. Women also face challenges with social participation in the new community, but the impact of relocation on their psychology is less pronounced as their expectations of social participation are inherently lower.

Again, within the relocated community, there are notable differences in the leisure activities of elderly men and women. Ethno-religious activities remain unchanged, with male elders showing more interest in social affairs; while female elders participate less in social activities. The lack of positive and healthy leisure activities for both genders may ultimately undermine their motivation to engage socially in the new community.

Suggestions

Facilitating social participation among older members of ethnic minority migrant communities is a complex issue, given the trends of industrialisation and modernisation. However, certain measures can be taken to alleviate the pressure on the elderly and increase their opportunities and motivation for social participation. The traditional Chinese idea and culture of “providing the elderly with a sense of belonging and security” has significant implications. The post-relocation policy should not only focus on young and middle-aged individuals but also on those aged 50 or above. In addition to improving healthcare services for the elderly, it is important to address their mental health and social participation. Specific measures should focus on two aspects. Firstly, it is necessary to encourage the elderly, particularly men, to learn and acquire marketable skills to increase their employability. Secondly, it is necessary to vigorously develop social and cultural activities in the relocated communities to attract the participation of the elderly and encourage them to engage in healthy and active leisure activities, thus contributing to the building of a harmonious community.

Data availability

Data for this study was collected by our research group through local government channels, and interviews were conducted with permission from the grassroots government and agreed by the interviewees. Unfortunately, we are unable to provide the data due to legal restrictions. The data provider did not agree to share their details publicly, so supporting data is not available. The attachments are solely for the purpose of this study.

References

An Bei. Five years, nearly ten million people, this “relocation” has far-reaching impact. Xinhua News Agency, Beijing, December 3.2020, http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020-12/03/c_1126818784.htm

Berger B (2009) Political theory, political science and the end of civic engagement. Perspect Politics 7(02):335–350

Chen B (2017) The gender of livehood--the field study of gender division of labour in a Dong minority village. Guangxi University for Nationalities, 05

Gansu Holds Series of Conference on building a moderately prosperous society and Fighting Poverty Alleviation (Linxia Session), Gansu Provincial People’s Government Information Office, 2020.12.21, www.scio.gov.cn/xwfb/dfxwfb/gssfbh/gs_13853/202207/t20220716_230900.html

Gansu Province National Economic and Social Development Statistics Bulletin in 2020, Gansu Provincial Bureau of Statistics, 2021.3.30

Gansu Province’s '13th Five-Year' Plan for Poverty Alleviation Relocation”, Gansu Development and Reform Commission, 9 August 2016, https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzI1NTEyNjM3MA==&mid=2247483764&idx=1&sn=b3f304cae10f54ef8efa03aa12b162db&chksm=ea3bff79dd4c766fde47a464698a35f2b8ff4412a7ef0204155202ba4fe8fe92126f6da7730b&scene=27

Hanyu L (2020) Research on influencing factors of female community participation under the perspective of gender. East China University of Political Science and Law 06

Hidehiro S, Liang J, Liu X (1994) Social networks, social support, and mortality among older people in Japan. J Gerontol. ume 49(Issue 1):S3–S13. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/49.1.S3

Holmes WR, Joseph J (2011) Social participation and healthy ageing: a neglected, significant protective factor for chronic non communicable conditions. Glob Health 7:43. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8603-7-43

Hu H, Hengyuan Z, Yonggang T (2022) Patterns of social participation and impacts on memory among the older people. Front Public Health, 15 November 2022. Sec. Aging and Public Health 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.963215

Hu Y, Bei L (2020) Impact of social activity participation on the health of the migrant elderly: An empirical study based on propensity score matching (PSM). Mod. Prevent Med. 47(24):4488–4491

Hundred Questions and Answers on the Work of Poverty Alleviation Relocation in the New Era (III), China Linxia Network - Ethnic Daily, 18.10.2019, www.linxia.gov.cn/lxz/zwgk/zc/zcjd/zzjdzc/art/2022/art_5da7b5b713cc45098b5ac2fd83e1270e.html

Hundred Questions and Answers on the Work of Poverty Alleviation Relocation in the New Era (I), China Linxia Network - Ethnic Daily, 2019.10.18, www.linxia.gov.cn/lxz/zwgk/zc/zcjd/zzjdzc/art/2022/art_69295fd8a0d94313bb692bc0073dd69a.html

Li LW, Liu J, Xu H, Zhang Z (2016) Understanding rural–urban differences in depressive symptoms among older adults in China. J. Aging Health 28(2):341–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264315591003

Li YP, Lin SI, Chen CH (2011) Gender differences in the relationship of social activity and quality of life in community-dwelling Taiwanese Elders. J. Women Aging 23(4):305–320

Lim-Soh JW, Lee Y (2023) Social participation through the retirement transition: differences by gender and employment status. Res. Aging 45(1):47–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/01640275221104716

Marsh C, Agius PA, Jayakody G et al. (2018) Factors associated with social participation amongst elders in rural Sri Lanka: a cross-sectional mixed methods analysis. BMC Public Health 18:636. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5482-x

Minagawa Y, Saito Y (2015) Active social participation and mortality risk among older people in Japan: Results from a nationally representative sample. Res Aging 37(5):481–499. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027514545238

Morrow-Howell N, Putnam M, Lee YS et al. (2014) An investigation of activity profiles of older adults. J Gerontol. 69(5):809–821

Pais, SRS (2016). Projeto – covilhã cidade amiga da pessoa idosa: Espaços exteriores e edifícios: Participação cívica e emprego (Order No. 30213707). (2775966708). Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/projeto-covilhã-cidade-amiga-da-pessoa-idosa/docview/2775966708/se-2

Pan Q, Wang M, Wang H, Zhu W (2021) Effects of social activities on cognitive function of the elderly. Mod Prevent Med 48(11):2022–2026

Park S-Y, Chun Young M, Lee Sun H (2013) Effects of elder’s role performance and self-esteem on successful aging. J Korean Gerontological Nurs. 노인간호학회지 15(1):43–50

Seok SY, Noh JH (2017) The effects of asset on life satisfaction among the elderly: focused on the multiple mediating effect of participation in social activities. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 37(2):216–250. https://doi.org/10.15709/hswr.2017.37.2.216

Shen L (2020) Gansu Province’s poverty alleviation relocation has achieved obvious results. Gansu Daily

Shi W (2021) A study on the Conspiracy relationship between Capitalism and Gender Division of Labour under the perspective of feminist. Guangxi Soc Sci (06): 87-94

Sun J, X Tim (2019) China’s poverty alleviation strategy and the delineation of relative poverty line after 2020: An analysis based on theory, policy and empirical data. China Rural Econ (10):98-113

Tyrovolas S, Haro JM, Panagiotakos D (2014) Successful aging, dietary habits and health status of elderly individuals: A k-dimensional approach within the multi-national MEDIS study. Exp Gerontology 60:57–63

Wang R, Ting L, Gang L (2021) Social participation patterns and its influence on age identity of the Chinese elderly. Popul Dev 27(06):151–161

Wang X (2015) Civil participation, political participation and social participation: conceptual discrimination and theoretical interpretation. Zhejiang Acad J (01):204-209

Wu W, M Qian (2023) What is the poverty standard and poverty incidence rate. National Bureau of Statistics

Xie L, Bin W (2019) Social participation profile of the Chinese elderly in the context of active ageing: Patterns and determinants. Popul Res 43(03):17–30

Yang, YN, Meng YY (2020) Is China Moving toward Healthy Aging? A Tracking Study Based on 5 Phases of CLHLS Data. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17 (12)

Yao S, Linzhu W, Yali Z (2020) A study on the impact of widowhood on social activities participation of elderly----based on the data from China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Product Res (11):1-4

Yot A, Prachuabmoh V, O’Brien M (2023) Does social participation make Thai psychologically abused elders happier? a stress-buffering effect hypothesis. J Elder Abuse, 35 - Issue 2-3

Yung-Chieh Y, Yang M-J, Yang M-S, Lung F-W, Shih C-H, Hahn C-Y, Lo H-Y (2005) Suicidal ideation and associated factors among community-dwelling elders in Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 59(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01387.x

Zhang J (2018) Relocation of poverty alleviation under the vision of campaign-style governance - Based on the survey of X City in Western China. China Agric Univ J Soc Sci. Ed. 35(05):70–80

Zhang W, Zhao D (2015) Analysis on patterns of social Participation of young and middle aged elderly in urban China. Popul. Dev. 21(01):78–88

Zhang YL (2019) State Council Poverty Alleviation Office: Income from poverty should reach 4,000 yuan in 2020. China.org. http://www.china.com.cn/lianghui/news/2019-03/07/content_74542476.shtml

Zhong Y, Jing C (2022) Gender Differences in the Score and Influencing Factors of Social Participation among Chinese Elderly. J Women Aging 34(4):537–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2021.1988313

Acknowledgements

The study is funded by the item “Empirical study on the effectiveness of relocation of poverty alleviation in western minority areas” (No. 20bmz146) which is one of the Chinese National Social Science Fund Project in 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ziyao Zhang contributed to the conception and analysis of the study and authored the manuscript. Lin Feng provided constructive discussions and assistance with the analysis. All authors agreed and consented to the publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

In 2020, our research group was working through our school (Gansu Agricultural University) to interface with the People’s Government of Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture and got the permission and help of the government office. We have collected data from Linxia Prefecture Rural Revitalization Bureau and its subdivisions, our interview has also been permitted by the Bureau and helped by their public servant. No other ethical approvals need to be granted for this study and there were no ethical approval number. The interviewees all know that the information we collected is for research and has agreed to do the questionnaire.

Informed consent

The interviewees all know that the information we collected is for research and has agreed to do the questionnaire. All authors have agreed to publish this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Feng, L. Social participation and its gender differences among ethnic minority elders after poverty alleviation relocation (Linxia, China). Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 543 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03043-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03043-z