Abstract

How does Tencent—a leading Chinese Internet enterprise—frame news to regulate popular nationalism? To address this problem, we applied the automated sentiment analysis program to more than 500,000 news comments on the Tencent news website during the 2012 Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands incident. The results show that audiences’ online nationalism is significantly influenced by Tencent news, user engagement, and emotions. First, contrary to using stimulative nationalist narratives in the early stages of the incident, the platform shifts to restrictive nationalist narratives to prevent online nationalism from endangering social governance; second, restrictive news can decrease popular nationalism compared with stimulative news; third, users’ love, anger, and disgust emotion can increase their support for China, while the happiness emotion has the opposite effect. Online nationalism, as imaginary engagement, arises from the collusion among platforms, the government, and audiences, contributing to maintaining the government’s legitimacy. The computational approach promises to shed light on nationalism research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The expansion of the Internet has brought about a profound debate on its impact on the communication of Chinese nationalism. On the one hand, Technology and important symbols are key to constructing chauvinistic online nationalism (Schneider, 2018). Hyun and Kim (2015) found that online political expression can enhance nationalism. Advanced information and communication technologies play a pivotal part in the interaction between state-led nationalism and popular nationalism (Schneider, 2022). On the other hand, the co-existence of the Internet and the party-state gives rise to both government critics and pro-government voices (e.g., nationalism) (Han, 2018). Online nationalism can influence government policies by integrating online nationalism into the political system and prompting the government to grant more freedom to cyberspace (Wu, 2007). In addition to facilitating online public opinion, the Internet also challenges the discourse power and information control of the state (Liu, 2006; Shen and Breslin, 2010; Esarey and Xiao, 2011). In contrast, Wang and Kobayashi (2021) show that state-controlled media increases nationalism, while social media present contrasting effects: WeChat has a positive effect on nationalism, but Weibo has a negative effect on nationalism.

Further, most of these discussions overlook the public’s engagement with online nationalism and their interaction with the platforms. What online audiences express in detail and how platforms react to such public opinion remains unclear. For example, Wang and Tao (2021) analyzed nationalism reflected in the comments on Chinese social media and argued that the political crisis triggers the rising of nationalism and its evolution. Yet they only selected a portion of the full dataset as representatives, which limited the comprehensiveness of their study (Wang and Tao, 2021). Similarly, Yuan (2021) looked into a large number of posts on social media and identified the topics presenting nationalist sentiment. However, the interaction between the platforms and the audiences was largely ignored.

To resolve the dispute regarding the relationship between the Internet and Chinese online nationalism, we claim that Chinese online nationalism is imaginary engagement. By analyzing large-scale datasets of Tencent news comments, we fill the research gaps by exploring how online platforms portray nationalist events, how audiences express nationalist sentiment, and the interaction between them. We argue the collusion among the platforms, audiences, and the government gives rise to the imaginary engagement with Chinese online nationalism. Two characteristics of the Tencent news comment data are essential for this study: On the one hand, provided by a large number of Chinese audiences, the comments reflect Chinese people’s online public opinion. On the other hand, as the audiences are less aware of being investigated by the researchers (Salganik, 2018), the comment data they provide could be less biased compared with those collected from traditional surveys. Our findings show that the level of audience engagement, the platform’s restrictive strategy, and the audience’s emotions have a significant influence on their support for China.

In specific, we focus on the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands incident, which has been the most influential international conflict for China and generated a wide antagonization of Japan in the past decade (Schneider, 2018, p.1–2). The most recent conflict of the incident started in April 2012, when the Japanese government proposed to purchase the islands. It lasted for about half a year, followed by several protection activities from mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. Although how people access information and express their opinions has changed over the past decade, the logic of Chinese online nationalism as imaginary engagement emerged in the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands incident still holds. First and foremost, media platforms are required to comply with government regulations and oversight. Second, media platforms are dedicated to seeking revenue from audiences. Therefore, media platforms must balance their relationship with the government and audiences. When nationalism is beneficial to the government and national interests, it will be encouraged through media platforms; when the flames of nationalism threaten the government and national interests, they are suppressed through media platforms. Nowadays, as the governance of media platforms becomes increasingly stringent, this underlying logic has gained prominence. Therefore, although the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands incident took place a decade ago, it remains crucial for us to understand the logic of online nationalism as imaginary engagement.

We choose Tencent as a representative of the four major non-official news media companies in China, i.e., Tencent (qq.com), Sina (sina.com.cn), NetEase (163.com), and Sohu (sohu.com). First, Tencent is the most popular website among the four major portals. Second, Tencent has developed two instant messaging apps, Tencent QQ (developed in 1999) and WeChat (developed in 2011), providing an extensive user base. There were 798 million active QQ user accounts and over 300 million registered WeChat users in 2012 when the incident took place. A miniature Tencent news website or a breaking news snippet pops up at times in the user interface of the QQ and WeChat apps, linking to Tencent’s website and thereby increasing traffic. Third, while not allowed to create news reports, Tencent has its own opinion columns that effectively function as a kind of “Tencent news.”

According to China’s provisions on the administration of Internet news information services, Internet media—including these news portals—only have the right to gather and repost news from traditional media outlets instead of creating their own news. Consequently, these news websites can only repost the news produced by other news media. Yet a gray area exists: they can publish their opinions alongside the news. During the Diaoyu (Senkaku) islands incident, Tencent published the top news about the dispute on its homepage, provided background information in multiple forms (e.g., pictures, videos, and texts), and summarized the step-by-step development of the incident. In particular, Tencent published a special series on the incident in the Jinri Huati column, providing its own systematic and in-depth analyses. Each news report of Jinri Huati had a clear, pointed message for readers regarding how they should think about the incident or what they should do during the incident.

Literature review

Chinese online nationalism as imaginary engagement

Nationalism, as the most powerful political force, connects people, the platforms, and the government. The construction of nationalism is based on three elements: national boundaries, collective memory, and people’s engagement. Boundary makes a nation limited (Anderson, 1991). However, the boundary is not restricted to a territorial dimension; it also connotes political, cultural, and psychological variances that stimulate national consciousness or imagination. It takes a critical position in forming group identities, such as national identities (Barash, 2016).

We argue that people’s online engagement with Chinese nationalism is essentially imaginary. On the one hand, as Anderson (1991) claims, a nation is an imagined community shared by people living within the same boundary, and this national imagination is realized with print media. In cyberspace, which is an extension of the nation, most audiences do not know each other. Their perception of nationalism is obtained through their imagination after consuming various online content. Thus, online nationalism can be regarded as the imaginary engagement of audiences who express their nationalist sentiment on platforms.

On the other hand, the interplay between audiences and platforms constructs imaginary engagement with online nationalism. Audiences’ online engagement with nationalism encompasses activities, such as consuming news stories, expressing approval or disapproval by clicking the “like” or “dislike” buttons, and voicing nationalist opinions. Platforms play a pivotal role in facilitating online engagement with nationalism. To increase traffic, platforms are incentivized to increase audiences’ engagement. However, when online nationalist engagement poses challenges to the government, platforms will employ restrictive strategies to appease the public or even censor the audiences’ content (King et al., 2013; Han, 2018; Han and Shao, 2022). The strategic choice reduces the risks caused by offline engagement and aids the government in maintaining social stability. Consequently, public engagement with online nationalism decreases their capacity to take action and participate in offline protests, which makes Chinese nationalism merely imaginary.

The imaginary engagement of online nationalism arises from the collusion of three parties (platforms, audiences, and the government). Three parties’ complicated relationships determine the mechanism of news production and consumption. In the form of imaginary engagement, audiences consume news and express nationalist emotions, platforms win their traffic for their economic purpose by framing the news, and the government maintains its legitimacy with the assistance of the platforms.

First, as the major disseminators of nationalism, platforms profit by increasing traffic by producing news reports that shape nationalist opinion, especially when nationalism is considered emotionally compelling and marketable. However, platforms must also adhere to the Party line (Zhao, 1998), which obliges them to serve as instruments of state propaganda. Specifically, in times of crisis, they bear the responsibility of mitigating the government’s communication risks. In practice, platforms employ communication strategies (e.g., news framing) to shape how audiences perceive nationalism. As a bridge connecting the government with the public, platforms have to balance the interests of both parties and bear pressure from both sides. Consequently, they produce news that caters to people while aligning with the government’s expectations.

Second, audiences’ online nationalist voices form their imaginary engagement in cyberspace. On the one hand, public engagement with news generates traffic for platforms. More importantly, it can bring political trust to the government. On the other hand, online expressions of nationalism can bolster netizens’ support for the government (Hyun and Kim, 2015). Shen and Guo (2013) suggest that nationalism and the form of consumed media are instrumental in consolidating political trust.

Third, the government plays a significant role in shaping Chinese nationalism and regulating communication on platforms. On the one hand, the government regulates platforms to consolidate or at least maintain its legitimacy. On the other hand, while nationalism fosters nation-states, it also poses threats to social stability (Billig, 1995, p.43). For example, the government has implemented a long-term Patriotic Education Campaign targeting the Chinese youth to strengthen political legitimacy (Zheng, 1999, p.90). However, when abrupt events stoked excessive nationalism, the populace would blame the government for its softness in international conflicts, potentially undermining the government’s legitimacy.

Yet, we can only observe the behaviors of two parties, with the government hidden behind the scenes. First, the platform produces the news with its nationalist strategies. Second, the audiences create news comments to express their nationalist opinions. Before formally developing our hypotheses, we need to describe the nationalism arising from news and news comments. Thus, we formulate our descriptive research question as follows:

RQ: How is Chinese online nationalism constructed in the news of commercialized news portals and audiences’ comments, respectively?

Restrictive strategies

Platforms employ various communication strategies to portray news stories and further shape public opinion. The most common two tactics are agenda setting and framing. Agenda setting refers to the mechanism that mass media set the agenda for audiences (McCombs and Shaw, 1972). Platforms set the public agenda through news reports on nationalist events. By emphasizing what communicators intend to highlight, platforms direct the audience’s attention to specific topics while neglecting others. Similarly, framing tells audiences how to view various issues in news. Entman (1993, p.52) asserts that “to frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described.”

Nationalism encompasses both rational and irrational elements (Kecmanovic, 2005). The engagement with nationalism can thus be either rational or irrational. Correspondingly, patriotism is classified into two types: rational patriotism (pinyin: lixing aiguo) and irrational patriotism (pinyin: feilixing aiguo) (Allison and Williams, 1971; Li, 2018). Rational patriotism advocates the expression of patriotic sentiment in a non-violent manner. On the one hand, rational patriotism avoids harm to fellow Chinese. On the other hand, it helps to maintain social stability and national interests (Li, 2014, p.189). In contrast, irrational patriotism, often criticized by Chinese media, involves non-violent protests (e.g., boycotting foreign products) and violent protests (e.g., smashing foreign automobiles or looting foreign shops), which can lead to economic loss and social chaos. In all, rational patriotism can reduce people’s irrational engagement in expressing radical nationalist sentiment.

Nationalism can be framed as either stimulative or restrictive. Stimulative news fuels emotions, appealing to nationalist audiences and generating higher traffic. In contrast, restrictive strategies are more commonly employed for the safety of the platforms. Restrictive strategies are implemented by adjusting the nationalism of the news. There are three basic forms of restrictive strategies, including obscuring national boundaries, blurring collective memory, and reducing people’s engagement. Among them, reducing people’s engagement refers to decreasing irrational nationalist behavior, such as boycotting foreign products and street violence, which poses challenges to social governance. Thus, platforms often emphasize the discourse of rational patriotism. While rational patriotism might be regarded as incapable by some nationalists, it is less likely to threaten the government. Similarly, Shen and Guo (2013) state that the positivity bias in the news reports of China as framing has a positive association with national pride and political trust in China. According to the arguments above, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H1: The restrictive strategy of news reduces audience support for China.

Engagement

Three aspects of audiences’ online discourse embody their engagement: the meaning of the content, the number of words, and the number of sentences in their comments. Longer comments with more meanings, words, or sentences suggest stronger nationalism, whether it is rational or irrational. The Chinese people, especially the young, are more hawkish than dovish in international conflicts (Weiss, 2019). Politicians apply discursive resources (e.g., thematic, evaluative, and cultural representations) to arouse state nationalism in support of their governance (Wang, 2017). The interaction between officials and popular nationalism gives rise to the grassroots’ “wolf warrior” posture (Sullivan and Wang, 2023). The audience engagement fuels the flames by generating stronger online nationalism and creating more pro-government discourses. During the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands incident, it is reasonable to infer that most user comments support China. Therefore, the higher the level of audience engagement indicates the stronger Chinese nationalism.

H2: The extent of audience engagement increases audience support for China.

Emotions

Emotions play a significant role in people’s daily lives, which drives them to think and behave in certain ways. Nationalist propaganda manipulates emotions and anti-foreign sentiment (Mattingly and Yao, 2020). The Chinese state demobilizes and redirects online emotions into regime-supportive nationalism through multi-layered strategies (Song and Liu, 2023). Official media act as a system of emotional valves to stabilize society and relieve social tension (Lu et al., 2023). Following Ekman (1993) and Xu et al. (2008), we consider seven types of emotions in audiences’ comments, i.e., anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, surprise, and love. The presence of emotions suggests stronger nationalist sentiment, which can translate to increased support for China. For example, love is a sense of belongingness to people’s nation, while anger shows resentment towards other nations. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: The emotions of the audiences increase audience support for China.

Method

The data of Tencent news and comments

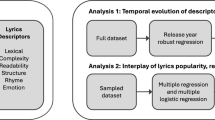

The Internet offers a broader spectrum of nationalist expressions (Denemark and Chubb, 2016) and serves as an ample database for nationalism research. We examined Tencent news on the 2012 Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands incident. First, we compared the news in Jinri Huati with the incident’s timeline to investigate Tencent’s publishing frequency and framing strategy. Second, we coded the news (stimulative or restrictive) in Jinri Huati to explore how Tencent switched its tones to adjust online nationalism. Third, we utilize a computer-assisted data collection system called Shuimiao (https://www.shuimiao.net/NewsComment/) to automatically gather the comment data. This system goes beyond mere sampling and instead scrapes the entire dataset, ensuring the validity of our data. Fourth, to explore netizens’ online nationalism, we analyze the news comments related to the coverage of the incident in Jinri Huati, mainly using sentiment analysis. The work steps of analysis are described in Fig. 1.

Manual coding of restrictive strategies in news

Jinri Huati consists of more than 20 news reports on the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands incident. We chose the first 18 news reports (see Appendix 1) that covered almost the whole incident from April 2012 to September 2012. Tencent framed the news by adjusting its content in line with its incentives. We set the coding rules as follows: if the news reports are used to attract people’s attention to the incident and encourage people to resist or fight with Japan, we categorize them as promoting nationalism and mark them as “stimulative.” Specifically, news reports that emphasize national boundaries, the collective memory of Japanese resentment, or promote nationalist engagement (e.g., setting a nationalist example from other nations) are regarded as “stimulative.” News reports that create a diversion from the incident by obscuring national boundaries, blurring collective memory, or reducing engagement (directly calling for “rational patriotism”) are marked as “restrictive.” Two coders are recruited to code the restrictive strategy of 18 news independently, and the intercoder reliability is 1.

As shown in Table 1, the first news report (titled “How to view the Japanese people’s support for purchasing the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands?”) calls for prompt action to cope with Japan’s political pursuit on the international stage. In the news, Tencent tries to obscure national boundaries (to reduce antagonism) between China and Japan by narrowing the definition of the enemy as the Japanese right-wing group rather than the Japanese government and people. This article aims to relieve the conflicts, so we mark it “restrictive.” Another example is the fourth news report (titled ‘How to view “defending the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands” among the populace?’). It says that the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands are actually controlled by Japan, so it is not feasible for the Chinese government to take any action. However, it is worthy of praise for the populace to defend the islands, which aims to increase people’s engagement in the incident. So we mark this article “stimulative.” We code the 18 news reports and identify the strategies that Tencent applied in each news report.

Manual coding of nationalist sentiment in news comments

As shown in Table 2, we develop a coding scheme of nationalist sentiment. Two coders are recruited to categorize the nationalist sentiment in news comments into five levels according to the coding scheme and the tone expressed in the comments: “very high” (score = 2), “high” (score = 1), “neutral” (score = 0), “low” (score = −1), and “very low” (score = −2). It is necessary to note that the platform or the government aims at controlling nationalism at a “very high” level, which will arouse collective action or harm foreign relations. The intercoder reliability is between 0.84 and 0.88 (Hosti score = 0.91, Scott’s Pi = 0.84, Cohen’s Kappa = 0.84, and Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.88).

Sentiment analysis

According to Pang and Lee (2008, p.10), sentiment analysis is “the computational treatment of opinion, sentiment, and subjectivity in text.” Pang and Lee (2008) suggest that sentiment analysis mines the data in terms of features, including term presence, position information, parts of speech, syntax, negation, and topic-oriented features.

First, we measure the emotions (anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, surprise, and love) embedded in the news comments using the Python Package cnsenti (https://pypi.org/project/cnsenti/). The measurements of emotions were originally proposed by Ekman (1993) and later enriched by Xu et al. (2008).

Second, we have also employed the Automated Sentiment Analysis Program (ASAP) to measure the nationalist opinion in the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands incident. This program was mainly adapted from a previous approach proposed by Hopkins and King (2010). However, the natural language processing module for Chinese word segmentation makes the ASAP different from the ReadMe package (Hopkins and King, 2010). To estimate the proportion of all documents in each category rather than classifying individual documents, Hopkins and King (2010) developed an unbiased method. The function of the ASAP is to perform the calculation of the proportion of catalogs with various sentiments. Thus, the ASAP is also called “opinion mining” which serves as an automatic classifier for objects. The supervised machine learning approach is employed in ASAP with unbiased estimation. The ASAP includes five steps as follows:

Step 1. Natural language processing with Chinese word segmentation. Hopkins and King (2010, p.232) argue that when processing an English text, it is necessary to convert all the words into lowercase, eliminate punctuation, and stem the word based on the characteristics of the English language. Analyzing a Chinese language text, however, is different. Chinese is made up of characters instead of letters that form words. The characters have no upper- or lowercase and no stems. Furthermore, different combinations of characters generate various meanings. We use the package of Chinese Lexical Analysis System (ICTCLAS) for word segmentation.

Step 2. Training set assignment. A prerequisite for the ASAP is a hand-coded training set large enough to contain all examples of nationalist sentiments in the online discourse that is to be analyzed. Using the examples of blogs, Hopkins and King (2010) suggest that coding more than about 500 documents to estimate a specific quantity of interest is probably not necessary unless one is interested in much more narrow confidence intervals than is common or in specific categories that happen to be rare. For some applications, as few as 100 documents may even be sufficient (Hopkins and King, 2010, p.242). 300–500 comments in each case is enough for the desired estimation accuracy. Therefore, we randomly select 300–500 comments for each of the eighteen news articles. Then, we manually code the selected comments to be the training sets according to the coding rules (see Table 2). With this training set, the ASAP learns how to understand and code the residual comments.

Step 3. Word table construction. After the previous steps, we download the training set of comments and the comments for automated sentiment analysis from a spreadsheet file to a Word table for further statistical processing. Based on the training set, the ASAP recognizes which words in the samples gain high points and which words deserve low points. For example, in the training set, we mark the comments containing the phrase “打日本” (strike against Japan) with 2 points and those with the meaning of “谴责” (condemn) with 1 point.

Step 4. Unbiased proportion estimation of comments with different sentiment levels. Instead of finding a needle in the haystack, Hopkins and King (2010) propose to directly characterize the haystack. The central idea of Hopkins and King (2010) relies on the so-called random selection assumption: the misclassification probability calculated using data from the training dataset also applies to unlabeled population datasets. By directly estimating the document proportion using the algorithm developed by Hopkins and his colleagues (Hopkins and King, 2010; Hopkins et al. 2012), the ASAP provides a relatively low biased proportion estimation.

Step 5. Results reporting. The ASAP outputs the proportions of different levels of nationalist sentiment.

Results

To answer the research question, we start from describing the communication strategies in the Tencent news of Jinri Huati and the nationalism presented in the audience comments. Further, we employ regression models to formally test our hypotheses and examine the relationship between Tencent’s communication strategy and the audiences’ online nationalism.

Tencent’s news framing

As Tencent’s standard narration about the Sino-Japanese conflict, the first column of Table 1 shows the incident development summarized by Tencent editors based on the reports of the other media outlets. As the summary of the facts of the incident, it is more objective than Tencent editors’ discussions. The second column of Table 1 shows the titles of 18 Jinri Huati news reports. By comparing the incident development situation (the first column) and the news reports of Jinri Huati (the second column), we explore the publishing frequency of Tencent news. Additionally, after reading the news, we code Tencent’s general attitude toward nationalism (the last column). Two key points arise from our observations: First, the publishing frequency suggests the news framing function of the platform; second, whether the Tencent news can stimulate nationalist sentiment depends on Tencent’s framing purpose.

First, Table 1 illustrates that Tencent’s news publication lags behind incident reports. When the other media outlets release reports on the Japanese government’s activities during the incident, Tencent follows by producing corresponding Jinri Huati news reports to guide public opinion. For instance, four sub-incidents were covered by other media outlets in April 2012, while the related Jinri Huati news reports emerged on 1 May 2012. In May, with limited incident news, Tencent did not create additional Jinri Huati news. Similarly, when another four sub-incidents were reported in June, Tencent produced two related Jinri Huati news reports in July.

Second, Tencent actively frames the news in response to the incident’s development. In August, when the Japanese government officially initiated the nationalization of the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands, Tencent significantly increased the number of Jinri Huati news reports, reaching a total of six. These news reports were swiftly published from 16 August to 28 August, with new reports appearing in no more than four days. This surge was prompted by widespread protests in major cities of China during this period. As the dispute came to a climax in September, a total of nine Jinri Huati news reports were released. Consequently, from Tencent’s perspective, the increase in the number of Jinri Huati news reports reflects the escalation of the Sino-Japanese conflict and the growing demand for online news framing.

Third, when examining the results of manual coding of the Jinri Huati news, a clear pattern of restrictive strategies emerges. As Table 1 shows, out of the 18 Jinri Huati news reports, only two are marked as “stimulative,” while the remaining 16 are classified as “restrictive.” Notably, the two stimulative news reports (the fourth news and the fifth news) were published during a phase when the conflict had not escalated. Even in their stimulative capacity, these reports only called for certain actions without fueling strong resentment or resistance against Japan. An important milestone of the incident was the Japanese government’s signing of the purchase contract with the private owner on 11 September which incited considerable frustration among many Chinese citizens. The eruption of nationalism caused violence towards the Japanese residents in China and even incidents involving Chinese individuals working for Japanese companies or married to Japanese spouses (Wallace and Weiss, 2014). Such a situation posed a direct challenge to state governance. Excessive nationalism leading to social turmoil could tarnish the government’s image and legitimacy (Shirk, 2008). It is reasonable to speculate that Tencent’s shift in reporting aligns with internal directives from the authorities to temper nationalist sentiment. Consequently, Tencent adjusted the frame of subsequent news reports (from the sixth news to the eighteenth news) to emphasize rationality in the context of the incident, aiming to bring down nationalist sentiment to an acceptable level to the government. The restrictive strategy of Jinri Huati news underscores Tencent’s efforts to curb popular nationalism.

In summary, Tencent managed its news production during the incident by adapting both the publication frequency and the news content. Initially, as the incident began, Tencent released Jinri Huati news with relatively low frequency. As the conflict escalated, Tencent significantly increased its coverage of the incident, effectively framed the news, and enhanced audiences’ nationalist sentiment. Notably, when offline protests engendered much violence, Tencent’s news production featured the restrictive strategy, which helped suppress popular nationalism and advocate rational patriotism. As Zheng (1999) argues, rational patriotism represents a milder form of nationalism supported by the government.

Public engagement with Tencent news

Analyzing audiences’ engagement involves two key steps: comment count and sentiment evaluation. The first step involves counting the number of comments in each Jinri Huati news report. Tencent news allows audiences to air their opinion and engage with the news content. The sheer volume of comments indicates a significant level of interest and engagement among the audience with regard to the incident covered in the news.

Figure 2 shows the comment number of 18 Jinri Huati news reports comments (see also Appendix 2). Notably, there is a noticeable spike in the number of comments in late August and early September, aligning with the climax of the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands conflict and Tencent’s increasing coverage of the incident (see Table 1). Given the issue of salience to national sovereignty, we interpret these spikes in coverage and comments as signs of increased interest in national identity and nationalism.

Figure 2 reveals an interesting observation regarding audience engagement. Specifically, the fifth news report, titled “Why Does the South Korean Government Strongly Defend Tokdo Island (Takeshima)?” and the eighth news report, titled “A Patriot: Shintaro Ishihara,” received significantly fewer comments compared to the other news reports. This discrepancy can be attributed to the fact that these two news reports do not directly discuss the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands incident, which is the central focus of the news series titled “The Escalation of the Diaoyu Islands Crisis.”

Sentiment analysis of the user comments

The second step aims at evaluating nationalist sentiment within the comment data using the ASAP program. With the processed data, the ASAP program is run to conduct sentiment analysis. We also calculate the mean values of nationalist sentiment in each news report. Figure 3 displays the percentage of different levels of nationalist sentiment in the 18 Jinri Huati news reports. There are two spikes (the second news and the seventh news, above 40%) in “very high” nationalism (which Tencent aimed to decrease).

Tencent’s strategic narration of the conflict aims to balance the expression of nationalism with the need to prevent excessive violence and social chaos. Without the restrictive approach, the level of nationalism might have escalated further, given the peak of offline nationalism during that time. Here’s a breakdown of their strategies:

First, catering to angry emotions. At the start of the anti-Japanese demonstration in August 2012, Tencent published two stimulative news reports (the fourth news and the fifth news) on 16 and 20 August 2012 (see Table 1). These reports aimed to cater to audiences’ angry emotions and promote nationalism.

Second, shifting to a restrictive tone. As street demonstrations escalated and violence became prominent, Tencent quickly shifted to a restrictive tone. On 21 August 2012, they released the sixth news, which advocated rational patriotism and discouraged boycotting Japanese products. The restrictive voice continued throughout the rest of the incident.

Third, gradual reduction of nationalism. Figure 3 shows that Tencent’s strategy to dial back nationalism does not have an immediate effect. The seventh news still has very high-level nationalist sentiment (above 40%). However, from the eighth news to the eighteenth news, the level of high-level nationalist sentiment consistently remains below 30%, which is considered within an acceptable range.

Figure 4 shows the mean percentage of nationalist sentiment. First, the proportion of comments categorized as “low” and “very low” is very small. In particular, the proportion of “very low” level is almost negligible (0.28%). Second, the largest portion of nationalist sentiment falls into the “high” category (70.57%) instead of “very high,” suggesting that most audiences utilize a rationalist frame to express their nationalism. They tend to adopt rationalist discourse (e.g., orally condemning Japan) rather than promoting collective actions (e.g., proposing war with Japan) that could jeopardize the government’s legitimacy. Third, the “very high” level nationalist sentiment (e.g., supporting war or smashing Japanese autos) is relatively high (15.88%), taking the second place among the five levels. Indeed, the risks associated with strong nationalism should not be underestimated. In addition, this pattern is relatively stable across 18 news reports.

After measuring the nationalist sentiment in the comments of Jinri Huati news, we investigate whether the nationalist sentiment reflected in the comments is affected by Tencent’s framing of the news. Qualitatively speaking, it appears that the framing of Tencent in the Jinri Huati news is effective in influencing the tone and level of online nationalism among the audience during the course of the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands incident. In the beginning and middle part of the incident, Tencent only designed two stimulative news reports to promote online nationalism. Audiences’ “very high level” online nationalism takes a more significant proportion in the first seven news reports, implying that Tencent encourages audiences to raise nationalist sentiment. With the development of the incident, people’s offline nationalist sentiment became stronger, and protests continuously emerged in many cities (Wallace and Weiss, 2014). Therefore, Tencent switched to producing news to adjust nationalism by calling for “rational patriotism” after 21 August 2012. From the eighth news to the eighteenth news, the “very high level” nationalism was mostly below 20%, except for the tenth news and fourteenth news, only a little higher than 20%. In particular, during the climax of the incident (from 11 to 16 September 2012), when the 11th–13th news reports were released, the “very high level” nationalism was even lower than 10% (see Fig. 3). Thus, when the protests were fierce in the streets, Tencent tried to frame the news to restrict audiences’ online nationalism, which seems to be effective.

Overall, it shows that the audience’s engagement with Tencent’s news reports during the incident is marked by a high level of nationalism, but this nationalism generally remains within a range that did not incite widespread violence or extreme actions. While the public express strong nationalist sentiments, they are largely channeled through discourse and online expression rather than leading to widespread physical violence or extreme behaviors. This finding also highlights the role of media platforms in shaping and moderating nationalism sentiment.

Hypotheses testing

We formally conduct a logistic regression analysis to examine the relationship between Tencent news and online nationalism presented in audiences’ comments (see Table 3). We employ both OLS and mixed effects logistic regression to test the hypotheses. Using the support for China in 6398 comments as the dependent variable, we categorize the comments with high and very high nationalism as “support China” and those with very low, low nationalism, and neutral as “neutral or not support China.” We code the attitudes that “support China” as 1 and others as 0.

Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of the findings: First, there is a negative relationship between Tencent’s restrictive news framing and corresponding online popular nationalism. Compared with stimulative strategies, when Tencent applies restrictive strategies in its Jinri Huati news, online nationalism significantly decreases. This finding suggests that Tencent as a platform can effectively adjust popular nationalism. Second, the length of the comments positively influences the level of nationalism, suggesting that a higher level of engagement tends to intensify nationalism. Third, users’ emotions, including love, anger, and disgust, can increase their support for China, while the emotion of happiness has the opposite effect. In all, our hypotheses H1-3 are largely supported.

Discussion and conclusion

To understand how the interplay between the platform and its audience gives rise to online nationalism, we empirically investigate Tencent’s framing of Jinri Huati news, online nationalism presented in audiences’ comments, as well as their relationships during the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands incident. Tencent primarily employs the restrictive strategy to adjust online nationalism and alleviate the fervor of irrational patriotism. Through its strategic news framing, the platform effectively accomplishes its objectives: It bolsters popular nationalism by garnering audience attention through extensive reporting while concurrently tempering popular nationalism by adopting a more restrictive stance.

First, the “very high” level nationalism, signifying extreme nationalism, is present at a relatively low percentage, notably lower than the “high level” nationalist sentiment, which is considered conducive to the government’s interests and platform stability. Second, Tencent facilitates a rise of rational discourse in both news reports and user-generated comments aligned with the government’s official narrative, thereby assisting the government in forestalling collective action. In addition, audiences’ nationalist sentiment is relatively stable over time. Platforms, such as Tencent, effectively affect online nationalism through communication strategies in news reports. In contrast, popular nationalism in public demonstrations appeared challenging to control, with instances of violence erupting in numerous major Chinese cities during protests. From this perspective, online news websites play a crucial role in averting the erosion of government legitimacy.

We argue that the collusion of the platform, audiences, and the government shapes the underlying logic of audiences’ imaginary engagement with online nationalism. Since the government and censorship are hidden behind the scenes, we can only observe the explicit behaviors of the platform and audiences. The platform successfully generates revenue by capturing considerable attention from the audience while simultaneously aiding the government in preserving its legitimacy through the tempering of extreme popular nationalism. Audiences, in turn, fulfill their emotional and entertainment needs by consuming nationalist news and articulating their sentiments in online comments. Further, the impact of censorship aligns with the central logic of our argument: online censorship represents a structural factor contributing to Chinese online nationalism as imaginary engagement. If the framing strategy of news serves as a gentler means to temper nationalist sentiment, censorship acts as a forceful mechanism to suppress the fanatical national sentiment. Consequently, the government manages to uphold its legitimacy by restoring social order to a stable state. This synergistic alliance among these three parties effectively bolsters popular nationalism (Hyun and Kim, 2015).

Nationalism is inherently intertwined with the potential for violence. Just as Billig (1995, p.28) claims, “Violence is seldom far from the surface of nationalism’s history.” This argument prompts the question of whether individuals can truly exercise rationality in the context of a nationalist sentiment that is innately violent. Consequently, categorizing patriotism as “rational” and “irrational” may be problematic during the incident. Nevertheless, despite the inherent paradox, the platform’s persistent promotion of “rational patriotism” exerts a discernible influence on nationalist sentiment.

In all, drawing upon existing research on nationalism (Wu, 2007; Han, 2018; Schneider, 2018; Wang and Kobayashi, 2021; Wang and Tao, 2021; Yuan, 2021; Schneider, 2022), we suggest that the Chinese online engagement with nationalism is essentially imaginary. Platforms, to some extent, help confine Chinese online nationalism to the realm of imagination or mere expression, devoid of the potential for actionable outcomes. We make a valuable contribution to prior research by formulating Chinese online nationalism as a form of imaginary engagement. This study is inspired by Anderson (1991), who indicates that a nation is an imagined community and nationalism gives rise to our understanding of the nation. In a parallel vein, our research underscores that online public engagement with nationalism is also imaginary, which may address the ongoing debates in existing research regarding the influence of the Internet on Chinese nationalism (Esarey and Xiao, 2011; Schneider, 2018 and 2022; Han, 2018; Wang and Kobayashi, 2021). Admittedly, Chinese nationalism has been influenced by various external factors, such as tightened control of media under the new leadership and the China–United States trade war since 2012. Online nationalism seems to have become stronger in general than a decade ago. Nevertheless, the logic of collusion among platforms, audiences, and the government stays the same. Their intricate interplay may still forge the fundamental rationale behind audiences’ imaginary engagement with Chinese online nationalism.

Data availability

The dataset and code employed in this study are available on Open Science Framework https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/ZHT8E.

References

Allison CB, Williams LP (1971) Patriotism: irrational and rational. The Educational Forum 35(2):235–238

Anderson B (1991) Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso

Barash J (2016) Collective memory and the historical past. The University of Chicago Press

Billig M (1995) Banal nationalism. Sage

Denemark D, Chubb A (2016) Citizen attitudes towards China’s maritime territorial disputes: traditional media and Internet usage as distinctive conduits of political views in China. Inf Commun Soc 19(1):59–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1093527

Ekman P (1993) Facial expression and emotion. Am Psychol 48(4):384–392. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.4.384

Entman RM (1993) Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun 43(4):51–58

Esarey A, Xiao Q (2011) Digital communication and political change in China. Int J Commun 5:22

Han R, Shao L (2022) Scaling authoritarian information control: How China adjusts the level of online censorship. Polit Res Q 75(4):1345–1359. https://doi.org/10.1177/10659129211064536

Han R (2018) Contesting cyberspace in China: Online expression and authoritarian resilience. Columbia University Press

Hopkins D, King G (2010) A method of automated nonparametric content analysis for social science. Am J Polit Sci 54(1):229–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00428.x

Hopkins D, King G, Knowles M, Melendez S (2012) ReadMe: software for automated content analysis. Available at http://GKing.Harvard.Edu/readme

Hyun KD, Kim J (2015) The role of new media in sustaining the status quo: online political expression, nationalism, and system support in China. Inf Commun Soc 18(7):766–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.994543

Kecmanovic D (2005) The rational and the irrational in nationalism. Stud Ethnicity Nationalism 5(1):2–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9469.2005.tb00125.x

King G, Pan J, Roberts M (2013) How censorship in China allows government criticism but silences collective expression. Am Polit Sci Rev 107(2):326–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055413000014

Li Z (2014) On “rational patriotism and irrational patriotism” (tan “ganxing aiguo he lixing aiguo”). Leg Soc 27:187–189

Li J (2018) The rational expression of patriotism (aiguo de lixing biaoda fangshi). People’s Forum 18:130–131. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-3381.2018.18.054

Liu SD (2006) China’s popular nationalism on the Internet. Report on the 2005 Anti‐Japan Network Struggles. Inter-Asia Cult Stud 7(1):144–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649370500463802

Lu F, Huang Z, Meng T (2023) Official media as emotional valves: How official media guides nationalism on Chinese social media. Asian Surv. 63(4):611–640. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2023.1831404

Mattingly D, Yao E (2020) How propaganda manipulates emotion to fuel nationalism: Experimental evidence from China. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3514716

McCombs ME, Shaw DL (1972) The agenda setting function of mass media. Public Opin Q 36(2):176–187

Pang B, Lee L (2008) Opinion mining and sentiment analysis. Found Trends 2:1–135. https://doi.org/10.1561/1500000001

Salganik MJ (2018) Bit by bit: social research in the digital age. Princeton University Press

Schneider F (2022) Emergent nationalism in China’s sociotechnical networks: How technological affordance and complexity amplify digital nationalism. Nations and Nationalism 28(1):267–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12770

Schneider F (2018) China’s digital nationalism. Oxford University Press

Shen F, Guo ZS (2013) The last refuge of media persuasion: news use, national pride and political trust in China. Asian J Commun 23(2):135–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2012.725173

Shen S, Breslin S (2010) When China plugged in: structural origins of online Chinese nationalism. In S Shen & S Breslin (Eds.) Online Chinese nationalism and China’s bilateral relations (pp. 3–12). Plymouth

Shirk L (2008) China: fragile superpower. Oxford University Press

Song L, Liu S (2023) Demobilising and reorienting online emotions: China’s emotional governance during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian Stud Rev 47(3):596–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2022.2098254

Sullivan J, Wang W (2023) China’s “wolf warrior diplomacy”: The interaction of formal diplomacy and cyber-nationalism. J Curr Chin Aff 52(1):68–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/18681026221079841

Wallace J, Weiss JC (2015) The political geography of nationalist protest in China: cities and the 2012 anti-Japanese demonstrations. China Q 222:403–429. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741015000417

Wang J (2017) Representing Chinese nationalism/patriotism through President Xi Jinping’s “Chinese Dream” discourse. J Lang Politics 16(6):830–848. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.16028.wan

Wang X, Kobayashi T (2021) Nationalism and political system justification in China: differential effects of traditional and new media. Chin J Commun 14(2):139–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2020.1807372

Wang Z, Tao Y (2021) Many nationalisms, one disaster: categories, attitudes and evolution of Chinese nationalism on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Chinese Political Sci 26(3):525–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-021-09728-5

Weiss JC (2019) How hawkish is the Chinese public? Another look at “rising nationalism” and Chinese foreign policy. J Contemp China 28(119):679–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2019.1580427

Wu X (2007) Chinese cyber nationalism: evolution, characteristics, and implications. Lexington Books

Xu L, Lin H, Pan Y, Ren H, Chen J (2008) Constructing the affective lexicon ontology. J China Soc Sci Tech Inf 27(2):180–185

Yuan EJ (2021) The web of meaning: The internet in a changing Chinese society. University of Toronto Press

Zhao Y (1998) Media, market, and democracy in China: between the Party line and the bottom. Rowman & Littlefield

Zheng Y (1999) Discovering Chinese nationalism in China: modernization, identity, and international relations. Cambridge University Press

Acknowledgements

Qiaoqi Zhang would like to sincerely thank her PhD supervisors Prof. dr. Florian Schneider and Prof. dr. Stefan Landsberger from Leiden University for their encouragement, inspiration, and guidance on her PhD study when the early draft of this article was shaped. This research work is funded by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No.22BXW032) and the Social Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province of China (Grant No. 19JD001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qiaoqi Zhang conceived the study, analyzed the data, wrote the first manuscript, and served as the first author. Cheng-Jun Wang supervised the study, analyzed the data, revised the manuscript, wrote the cover letter, and served as the corresponding author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Q., Wang, CJ. Chinese online nationalism as imaginary engagement: an automated sentiment analysis of Tencent news comments on the 2012 Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands incident. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 484 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02983-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02983-w