Abstract

The social distancing imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the digitalisation of societies, which also influenced habits related to the consumption and dissemination of news. In this context, older individuals are often blamed for contributing to disinformation, which is associated with the echo chambers fostered by social media. Mass media, social media and personal communication tools act as mass, social or personal intermediaries when it comes to keeping up to date with the news. This paper analyses the preferred intermediaries of older online adults (aged 60 and over) for following the news and how they change over time. We analysed two waves of an online survey-based longitudinal study conducted in Canada and Spain, before Covid-19 pandemic (2016/17), and during Covid-19 (in 2020). We found that most participants exclusively use mass intermediaries or combine mass with social and personal intermediaries to keep abreast of the news. However, only 28% of respondents inform themselves exclusively through the alleged echo chambers of social and personal intermediaries. Results also show that media ecologies evolve in different directions, and, despite the forced digitalisation driven by the pandemic, digital media usage did not always increase or evolve towards newer technologies. This paper contributes to understanding the diverse intermediaries used by older adults to obtain news and how such media ecologies can contribute to contrasting different sources of information beyond the alleged echo chambers of social media.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the popularisation of the World Wide Web in the 1990s (Leiner et al. 2009), societies have followed a path of increasing digitisation and digitalisation. It challenges personal communication ecologies (Wilkin et al. 2007) by introducing new devices, products and services. Such ecologies imply the combination of different intermediaries to keep up to date with the news, including mass or hierarchical media (MM); mass self-communication media (MSCM) or social media (Castells 2009; Jenkins et al. 2015); and one-to-one communication (121C) technologies. Intermediaries are agents who transform information as they convey it to their audiences (Maglio and Barrett 2000). Thus, mass media, social media and personal communication tools act as mass, social or personal intermediaries when it comes to keeping society informed.

Social media in particular are associated with disinformation (Sunstein 2014). However, the so-called participatory media often do not operate in a vacuum and static media space. Many digital devices and services can be used for the same communication goals (Wilkin et al. 2007), with nuances giving rise to media competition, coexistence (Dimmick 2003) or even displacements (Newell et al. 2008), which can be particularly challenging for older people (Nimrod 2019). In addition, media habits shape the appropriation of new media, with possibilities ranging from adhering to tried-and-trusted media habits (LaRose 2010) to combining or abandoning them (e.g. Rosales and Fernández-Ardèvol 2018).

The social distancing imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the digitalisation of societies (Wai-Loon Ho et al. 2020), contributed to an increase in the consumption of electronic news (Van Aelst et al. 2021) and might have impacted the digitalisation of older adults as well. Before the pandemic, there was great interest in convincing older adults to use digital technologies to reduce the digital divide (Choudrie et al. 2018), as adopting digital technologies was supposed to benefit older adults with their advantages (Cotten et al. 2013). However, such prescriptions often came without considering autonomous and informed decisions that people of all ages, including older adults, make about selecting media that best fit their interests, habits and values. At the same time, ageist prejudices often associate older people with a lack of interest or poor skills in using digital technologies (Durick et al. 2013). In this sense, stereotypical prejudices often blame older individuals for not knowing how to use digital media properly (Comunello et al. 2022), and, particularly, for having fewer skills to be able to identify fake news (Dumitru et al. 2022).

This paper explores the declared preferred intermediaries to obtain news, which contributes to the empirical analysis of trends in news intermediation among older adults and their alleged contribution to disinformation. Our approach avoids the “decline narrative” (Gullette 2011) that views older adults as mere passive recipients of technologies (Marshall and Katz 2016). Instead, we look at how their practices change to accomplish everyday communication goals based on the combination of mass, social and personal intermediaries. Thus, the research questions (RQ) motivating our paper are: RQ1: What are the preferred news intermediaries used by online older adults? RQ2: How did they change with the Covid-19 pandemic? And RQ3: what similarities or differences can be observed between Canada and Spain?

The data used in this study correspond to two waves of a longitudinal study deployed before and during the pandemic. The first data collection was conducted between 2016/17 (wave 1, or W1) and the second one in November 2020 (wave 2, or W2), in two countries, Canada and Spain. The study targeted internet users aged 60 and over, as in both countries this age boundary allows to grasp the imminent transitions towards retirement. The content of this study focuses on their preferred media for keeping up to date with breaking news. The selected sample corresponds to the 1450 individuals participating in both waves, who are internet users with an average age of 70 in 2020. Given the structure of older internet users in the two countries, the proportion of male respondents (56%) surpasses female respondents (44%).

Our analysis focuses on Canada and Spain, countries with quite similar digital situations at the moment of the last wave of the study: (1) both are upper-middle-income countries (World Bank 2023); (2) whereas the age-based digital divide is closing in terms of access and use in both countries (International Telecommunication Union, 2020); (3) the best comparable data for 2020 show that internet use is higher in Canada, where 76.3% of adults aged 65+ were internet users (Statistics Canada n.d.), while in Spain the share was 70.5% in the 65–74 age group, falling to 28.7% in the 75+ age group (Spain, Instituto Nacional de Estadística 2021). Finally, (4) internet prices were different in 2020 in both countries: mobile internet prices are comparatively higher in Canada (0.67 GNIpcFootnote 1 VS 0.31 in Spain), while the cost of fixed broadband connection is comparative lower (Canada: 1.12 GNIpc, Spain: 1.72 GNIpc) (International Telecommunication Union, 2020). The selected countries, therefore, allow us to explore media prioritisation to obtain news among older internet users in two different contexts of digital appropriation in later life.

Following the irruption of the Covid-19 pandemic, a general trend of increased use of digital technologies was observed in other age-groups. We also expected such a trend between the two waves studied, although, results might be influenced by the circumstances at that moment of the pandemic and differences in appropriation of digital technologies and skills of the studied online population.

The following section provides the theoretical framework for analysing news intermediation. We then present details of the survey and the statistical techniques used. Subsequently, we report the results of our analysis. Finally, we conclude the paper by discussing our findings and conclusions.

Theoretical framework

As a result of new technological possibilities and user appropriation, information, and communication technologies (ICTs) keep changing or creating what could be considered new types of media. In the public sphere, the printing press, radio, and television are the oldest communication technologies widely used nowadays. In the personal sphere, we can include letters and landline telephones, which became popular before the 1970s (Diaz 1995; Raboy 1990). Such analogue media were followed, since the 1990s, by the popularisation of the internet (Leiner et al. 2009) and initially included only websites and email. Finally, the newest technologies used in our analysis are multimedia mobile messaging (Martín-Pozuelo 2012) and social network sites (SNS) (Bugeja 2006).

To some extent, analogue ICTs were transformed by the internet. Telegrams transformed into pagers and later into SMS (short message service) and mobile messaging via apps (Church and de Oliveira 2013). Emails replaced most of the letters, and most newspaper readers moved to online newspapers (Loos and Ivan 2022). The same is happening with the transformation of television, radio and voice calls into their equivalent apps, with the consequent reduction in the audience of the traditional media (e.g. Orús 2023). Such transformation implies a change in the main affordances of the media. Internet-based mobile messaging services allow text messages, voice and video messages, and a variety of multimedia file sharing (Church and de Oliveira 2013). Finally, social network sites (SNS) build on real-life word of mouth. Still, they represent an entirely new approach to mediated communication, where individuals’ social networks are placed at the centre of the media (Rainie and Wellman 2012).

The combination of all these possible communication media used by an individual constitutes their communication ecologies (Wilkin et al. 2007). Among communication ecologies, we distinguish between mass media (MM), social media (SM) and one-to-one communication tools (121C). MM refers to media that support one-to-many communication and provide information hierarchically. The contents are often written and edited responding to journalistic principles, although they could be biased towards certain ideologies, and focused on cost-effectiveness. Regarding SM, Castells (2009) defines them as mass self-communication media, and describes them as the digital media that support horizontal communication networks where all users can receive messages, but can also create, send and distribute messages to a massive audience, i.e. SNS, email, chat and mobile messaging. Contents are curated based on obscure algorithms that might be biased towards corporate interests (O’Neil 2016). Finally, 121C refers exclusively to one-to-one communication, meaning relying on personal relationships to obtain news, namely voice calls. The combination of mass communication and mass self-communication gives rise to what is known as media convergence. The news is explained differently through different types of media, as a range of voices can engage in various ways, with users able to take part in expanding news (Jenkins et al. 2013). Indeed, a “mix of top-down and bottom-up forces determine how the material is shared in far more participatory (and messier) ways” (Jenkins et al. 2013, p. 1) than in exclusively hierarchical (mass) media. With digital media, the idea of “prosumers” is reinforced (Toffler, 1980). Users become producers and consumers who not only circulate but also recreate news. Individuals consume, share, reframe, mix and create news beyond the paradigms of one-to-one communication or one-to-many consumption. This shift from distribution to circulation builds on the participatory culture that began to flourish with digital media (Jenkins et al. 2015).

In the early 2000s, the democratisation of the sources of online news, mainly through social media, put some individuals at risk of becoming trapped in “filter bubbles” or “echo chambers”, where they mostly see information that confirms their intuitions (Sunstein 2001). Online opinion leaders, such as journalists and politicians, can influence online communities with different ideologies, in some cases building on fake news (Guo et al. 2020). Big data and artificial intelligence can also influence individuals by building on their predicted ideologies, fears and phobias in an “information psychological war” (Colmenarejo 2021). Thus, the spread of rumours (Sunstein 2014) and fake news (Allcott and Gentzkow 2017) gains momentum as SNS become increasingly more relevant and the participatory culture is further popularised (Jenkins et al. 2015).

In order to keep up to date with the news, individuals can make use of mass media, social media or personal communication tools. Thus, the media act as intermediaries between individuals and information. Intermediaries are defined as programs or agents that select and adapt or transform information as they convey it to their audiences (Maglio and Barrett 2000). Although most of the literature focuses on the new opportunities provided by online intermediaries (del Águila-Obra et al. 2007; Schmidt et al. 2019), we also consider how personal communication tools and mass media act as intermediaries to access information, as they also select, adapt and transform the information they convey. In this context, individual media preferences account for the (lack of) diversity of intermediaries to obtain news, which creates concerns about the potential impact on democracy and public debate. This is mainly due to polarisation through the echo chamber effect of social media (Terren and Borge-Bravo 2021). Studies that claim an echo chamber effect in news consumption are mainly based on tracked data on social media. Contrarily, studies that support the opposite are mainly based on reported data (ibid) and show how people form their own opinion about different topics, not only based on what they read on social networks, but also on the consumption of other media.

In this context, older adults have been blamed for contributing to disinformation (Brashier and Schacter 2020; Loos and Nijenhuis 2020), although Loos and Nijenhuis (2020) explain that the studies that make such claims are limited to the analysis of disinformation in relation to Trump or Brexit and cannot be extended beyond those studies. However, such cases might have been influenced by cognitive or confirmation bias and its association with disinformation (Moscadelli et al. 2020; Terren and Borge-Bravo 2021). Confirmation bias refers to the “unwitting selectivity in the acquisition and use of evidence” (Nickerson 1998; p. 175). In the digital content era, individuals tend to select and trust the news that confirms their beliefs, for example, ideologically right-wing individuals tend to support disinformation aligned with their ideology more than individuals with centre or left-wing ideologies (Baptista et al. 2021). Thus, such studies might have been influenced by confirmation bias, political ideology or a lack of experience with the digital skills required to identify disinformation (Loos and Nijenhuis 2020).

Data and methods

Data

The data come from an international online survey panel, and their collection was done as part of the project Ageing Communication and Technologies funded by the Social Sciences and Research Council of Canada (ACT Project 2015). The survey panel consisted of three waves of data collection between 2016 and 2020. In this study, we focus on Canada and Spain at two specific points in time. The first point of data collection extended between 2016 and 2017 (which we identify as wave 1 or W1). For our study, we chose the last point of data collection, November 2020, as our second wave to allow for a larger time span (identified as wave 2 or W2). Data in our wave 2 was collected after the lockdown was over in both countries, although social distance measures were still in place to some degree.

The baseline sample design resembles each country’s population of internet users aged 60 and over. With a response ratio of 45.7%, the number of valid responses amounted to 5948 in W1. After four years, it achieved a 24.4% retention rate of valid responses (N = 1450). In the two countries, the retention rate surpassed the sample design expectations of 500 participants per country at the end of the study in 2020, although it appears to be lower than the usual values reported in the literature (e.g., Meng-Jia Wu et al. 2022). However, an online longitudinal survey that collected data monthly in a similar 4-year time span (Lugtig 2014) reports 61% of missing observations although “almost all of the respondents … miss one or more waves of the study” (Lugtig 2014, p.717). In the data we analysed, all the participants took part in the different waves of the original study (three in total), meaning that those who did not participate in one wave were not re-invited to the study and therefore excluded from the analysis.

Our selected sample corresponds to the 1450 individuals participating in both waves. Table 1 gathers the sample socio-demographic characteristics. Reports and analyses are based on the age of the respondents in W2.

As we can observe in Table 1, more than half of the sample corresponds to Spanish individuals, and around 56% are males. As for the level of education, in both countries the percentage of internet older-adults users with tertiary education is 43%. Interestingly, for primary level or no education it is around 2% in Canada, whereas in Spain it is around 21%.

Our interest is in the preferred media for checking timely information about a given event or breaking news (see Table 2 for results). The survey asked the respondents to select up to three options from a list of media. The wording of the question was as follows. In parentheses, we indicate the label of each category used in our analysis:

-

Imagine that you are in a hurry to get important information (e.g. the outcome of a political election or the winner of a football game). Please indicate the three sources of information that you are most likely to use from the following options.

-

Calling someone who is likely to have this information (Call)

-

Sending a text, voice or video message via your mobile phone to someone who is likely to have this information (M.mssg)

-

Sending an email to someone who is likely to have this information (Email)

-

Using social network sites, such as Facebook or LinkedIn (SNS)

-

Turning on the TV or radio (TV/R)

-

Checking websites (Web)

-

Using a computer-based chat program, such as Skype (Computer chat)

-

Other (please specify): ______

-

Don’t know

-

“Other” was recoded into existing categories when relevant and left as “Other” in the remaining cases. The selection had no set order, except for “Other” and “Don’t know”, which were always listed at the bottom. “Don’t know” became the only possible choice when selected.

Methods

First, a descriptive analysis of the data allowed us to identify statistically significant differences in the preference of each media between W1 and W2. Then, a latent class analysis (LCA) served to cluster the participants in each wave, reducing all possible combinations of preferred media to four classes.

Then, the latent class technique (LCA) was used to find unobservable classes or groups based on individual responses to the preference for each media and explain their characteristics. This method allows us to gain significant insights into the data structure and classify individuals into meaningful groups/classes based on their shared behaviours (using categorical data). Moreover, this approach (and using the posterior probabilities) allowed us to explain class membership over time.

Respondents could select up to three options out of ten media to show their preferences. Each item was a dichotomous variable (0=not selected, 1=selected). For more technical details on LCA, see Masyn (2013) and Nylund-Gibson and Choi (2018). Estimations were made using the R package poLCA (Linzer and Lewis 2011). To construct the latent classes, we considered the participants’ declared latest preferences (meaning, calculations are based on data from W2). To apply the LCA appropriately, we considered those categories with a minimum frequency of 5% in both waves (see Table 2), resulting in six media choices (TV/R, m.mssg, Email, SNS, Call and Web).

The model assumes that classes identified in the latest wave represent the underlying characteristics of the analysed data. We then calculated the estimated class probabilities and item response probabilities as a classification model, and then, calculated the likelihood of each individual belonging to each class and assigned everyone to the class for which they have the highest posterior probability.

We used the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to assess the optimal number of latent classes. Considering the sample size, the number of indicators remained within the acceptable thresholds.

According to the AIC and BIC criteria, the optimal model included four latent classes (named Class1 to Class4; see Supplementary Table S1 online). We named the four classes taking into account the most prevalent forms of information in each of them. Having selected the best model for W2, we assigned each participant to the class with the highest probability of membership. Class membership for W1 was then predicted using a posterior modal probability. These methods used the combination of media choices resulting in W2 to classify individuals in W1 and to uncover any changes in these choices over time. Then, each respondent was assigned to the corresponding class in W1, allowing us to capture media preference trends between waves. Although the calculations were made backward in time, the dynamics of the results are discussed in standard forward terms.

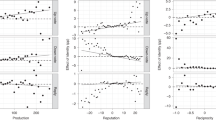

Finally, we used Sankey diagrams “to illustrate quantitative information about flows, their relationships and their transformation” (Riehmann et al. 2005, p. 233). This infographic tool depicts the individual transitions regarding the preferred combination of media over time.

Results

To respond to our research questions, we analysed preferred news intermediaries (RQ1), how they changed with Covid-19 pandemic (RQ2) and how they differ between the two countries (RQ3) at two levels, first by looking for trends in media use at the aggregated level (Section “Media considered individually”), and second by exploring the individual transitions (Section “Combination of communication practices”).

Media considered individually

In aggregate terms, Web, TV and Radio, and calls are the preferred intermediaries to get news (RQ1). We found that there are statistically significant differences through time. In the whole sample, there is a reduction in the preference for traditional media (TV/R) and websites (RQ2). However, at a country level, such differences are only significant in Spain (RQ3). Moreover, although voice calls and mobile messages do not show statistically significant variations over time for the total sample (RQ2), at the country level these decline in Canada and increase in Spain (RQ3) (Table 2).

Combination of communication practices

Latent class analysis offers a nuanced look at relevant trends in the combination of preferred media intermediaries for obtaining news. In what follows, we provide summary details about the classes and explore individuals’ transitions between classes from W1 to W2 (results from: Fig. 1, Tables 3 and 4):

-

Media choices (RQ1) identifies the media selected above the average in W2 and how it applies to W1 (see radars in Fig. 1 and Table 4) and presents the average number of preferred media intermediaries in the class (Table 4). Respondents were given a maximum of three media choices, whereas the average could be lower if they selected less than three options.

-

Size (RQ1 and RQ2) shows the class size, expressed as a share of the total population (see the bottom of the radar in Fig. 1 and Table 4).

-

Transitions (RQ2) details the individual’s transitions between classes from W1 to W2 (Sankey diagram in Fig. 1, Table 4 and Supplementary Table 2).

-

Socio-demographics (RQ2 and RQ3) changes in the composition of the classes between the two waves, including countries as a socio-demographic variable (Tables 3 and 4).

Class 1 (10% in wave 2): Mass and personal intermediaries (MM, websites and calls)

-

Media choices: respondents included in this class in each wave combined mass and personal intermediaries, they exclusively selected three media: TV/R, websites and voice calls, resulting in a constant average number of selected media.

-

Size: this one is the smallest class, reducing size from 17% in W1 to 10% in W2.

-

Transitions: only 15% of class members in W1 remain in W2, making it the most unstable class. The remaining 85% of new members in W2 came from the other three classes in similar proportions.

-

Socio-demographics: W2 includes more respondents with primary or lower education and shows a significant change in country composition. In W1, only about one-third of the class were from Canada; in W2, respondents were only from Spain. There were more men than women in both waves, although with no statistically significant changes.

Class 2 (30% in wave 2): Mass Intermediaries (MM and websites)

-

Media choices: respondents mainly use mass intermediaries to obtain news, i.e. TV/R (namely MM), websites. However, in wave 1, there was a major interest in email. The average number of media selected increased from 1.77 to 2.1.

-

Size: this class grew from 25% in W1 to 30% in W2.

-

Transitions: this is the most stable class, as 46% of the individuals in W1 remain in the same class for W2. The rest of the respondents came in similar proportions from the other three classes.

-

Socio-demographics: W2 sample includes more respondents with secondary education and a scarce proportion with primary or less education. W1 shows an equal distribution among countries, while W2 only included respondents from Spain. In both waves there were more men than women, with no statistically significant changes.

Class 3 (32% in wave 2): Mass and social intermediaries (MM & MSCM)

-

Media choices: individuals in this class mainly use mass and social intermediaries to stay abreast of the news, i.e. TV/Radio (namely MM) and websites in combination with SNS or m.mssg (namely MSCM). The average number of media selected is 2.96 in W1 and 2.62 in W2, meaning that not all respondents in this class chose three options, with a trend towards reducing the number of preferred media over time.

-

Size: this is the most significant class in both waves, and remained stable between waves, 33 and 32% for W1 and W2, respectively.

-

Transitions: this is the second most stable class, with 45% of the respondents remaining in this class. The rest of the respondents came from the other classes in similar proportions 16–24%.

-

Socio-demographics: W2 sample includes more respondents with primary and tertiary education and fewer with secondary education. In W1, three out of four individuals in the sample were from Spain, whereas in W2, respondents were all from Spain. In both waves there were more men than women, with no statistically significant changes.

Class 4 (28% in wave 2): Personal and social intermediaries (Calls and MSCM)

-

Media choices: respondents in this class combine personal and social intermediaries to obtain news, i.e. calls with emails and mobile messages in both waves. The average number of media in both waves is 2.7.

-

Size: this class grew from 25 to 28% of the sample.

-

Transitions: 41% of the individuals remained in this class between waves. The rest of the respondents came in different proportions from the other classes, between 15 and 30%.

-

Socio-demographics: W2 shows more respondents from Spain than in W1. Education and gender composition did not change significantly between waves; however, we observed more women than men in W1, with the opposite in W2.

Discussion

Our study examined the preferred news intermediaries (Maglio and Barrett 2000) of older adults (RQ1), including Mass Media, Social Media (Castells 2009) and 121 Communication intermediaries. How preferences changed, with the Covid-19 pandemic (2027/17 and 2020 respectively) (RQ2) and how preferences are different or similar in Canada and Spain (RQ3). We analysed those questions in aggregated levels and the different combinations of preferences.

Global and country-level media preference changes

When looking at the aggregated level, despite their preponderant position (RQ1), we observed a decline in the use of mass intermediaries (the more traditional media, namely TV/R and websites) to follow the news, which points towards a reduction in the interest in mass and unidirectional communication (RQ2); however, this accounts mainly for Spain (RQ3). This result aligns with studies that found that watching TV is diminishing in Spain (Orús 2023).

We also found some country differences in personal and social intermediaries, namely calls and mobile messaging. In Canada both media decreased, whereas in Spain they increased (RQ3), which could be related to the lower prices of mobile internet in Spain (International-Telecommunication-Union 2020).

Combinations of intermediary preferences (RQ1 and RQ2)

Regarding staying up to date with breaking news, respondents were grouped into four classes (Fig. 1), representing different tendencies in the variety of preferred news intermediaries (RQ1 and RQ2).

Only two classes (3 and 4), representing 60% of the sample in W2, include social intermediaries, i.e. the multi-directionality of social media, including SNS and mobile messaging, which are in question when discussing disinformation. From these two classes, only class 4, which represents 28% of W2, includes panellists who prefer to obtain news exclusively through individual and social intermediaries, which could be considered a lack of diversity of news sources and can contribute to polarisation and have an impact on public debate and democracy (Terren and Borge-Bravo 2021).

The other two classes (1 and 2), representing 40% for W2, include mass intermediaries, i.e. TV/R or websites, which represent mass media and hierarchical communication. From this, only class 1, representing 10% of the sample in W2, includes mass media and personal intermediaries for following the news, which could also lead to filter bubbles that contribute to disinformation.

Thus, most of the participants form their own opinions about different topics, not only based on what they receive from social media, but also on the consumption of other media, which might push them away from the so-called echo chamber effect of social media (Terren and Borge-Bravo 2021). However, TV/R, websites, emails and calls can also be used as filter bubbles that reinforce cognitive biases and contribute to disinformation.

Only two classes (1 and 4), representing 38% of W2, include personal intermediaries (namely calls) in their preferred media to access news. These results reveal that most of older adults’ distrust personal intermediaries when trying to stay abreast of breaking news or lack sufficient (digital) skills to consult mediated sources of information.

In other words, the online older adults in this study relied on their communication ecology (Wilkin et al. 2007) to keep informed, combining mass, social and personal intermediaries in different ways. For example, they combine the news circulating in participatory media (Jenkins et al. 2013) with the hierarchy of news conveyed through mass media and have little interest in making calls to keep abreast of breaking news. While previous studies claim older people are more prone to spreading disinformation (Brashier and Schacter 2020; Loos and Nijenhuis 2020), these results build mainly on tracked data on social media (Terren and Borge-Bravo, 2021). The communication ecology approach of our study allowed us to show that, at least to following news, older people do not put social media at the centre (Rainie and Wellman 2012); i.e they not only inform themselves through rumours (Sunstein 2014), fake news (Allcott and Gentzkow 2017) or the alleged echo chambers of social media responsible for disinformation (Terren and Borge-Bravo 2021), but they also combine different media to obtain information and build their own opinions, which may contribute to counterbalancing disinformation. However, the combination of preferred information media can also lead to filter bubbles and disinformation.

Changes after Covid-19 pandemic (RQ2)

Classes changed in size and composition before and during Covid-19 (Fig. 1 and Table 3). Classes 2 and 3 are the most stable ones, with almost half of the individuals staying in the same class in both waves. The individual class transitions between waves are represented in the Sankey graphics (Fig. 1). 60.5% of the respondents changed classes between waves (see Supplementary Table S3 online). The changes go in three different directions: 1) towards a variation in the number of preferred media (see Supplementary Table S3 online), 2) towards classes with more weight in the MSCM approach, a more digital approach, 3) towards classes with more weight in the MM approach, a more conventional use of media. Despite the imperant discourses about media displacement in the transition towards digital media (Newel et al. 2008; Nimrod 2019), these results show that older users not only move towards the appropriation of digital technologies, but also in different directions. Some older digital users in the study make informed choices regarding their preferred media, and this could include stopping using an already adopted media (e.g. SNS) and changing it for an older media (e.g. TV). Thus, not using new media is not always related to a lack of digital skills, as users choose the channel that best fits their communication needs and style.

Similarities and differences between Canada and Spain (RQ3)

There are no significant changes in the age and gender composition of the classes over time. Moreover, in the overall sample, we found that lower educational levels are more common in Spain than in Canada (Table 1), and therefore more common in the clusters with mainly Spanish respondents. This impacts the constitution of classes. Class 1 includes respondents who prefer mass and personal intermediaries, i.e. websites, TV/R and calls. In W2, it includes only respondents from Spain and with lower educational backgrounds. Class 2 focuses mainly on mass intermediaries, namely websites and TV/R. W2 includes only Spanish respondents with higher educational levels. Class 3 includes participants who combine mass and social intermediaries to obtain news, namely combining websites, TV/R, SNS and mobile messaging. In W2 it includes respondents exclusively from Canada with higher educational backgrounds. Finally, Class 4, focuses mainly on personal and social intermediaries, namely calls, mobile messaging and emails. It mainly includes respondents from Spain in W2 and lower educational backgrounds. This association between cluster 1, more focused on mass media and lower educational level, and conversely cluster 3, more focused on social media and higher educational level, should be related to the digital divide that associates lower educational levels with lower digital skills and uses (Friemel 2016). Thus, our data suggests that differences between the preferred intermediaries between Canada and Spain are mainly related to the sample’s demographics.

Limitations

This study focuses only on older adults online; thus, we were not able to compare the preferred intermediaries of other groups of adults. Due to the longitudinal nature of the survey design, the sample represents online older adults for the first wave and the sample attrition prevents a generalisation of the obtained results. Although our results are rich and analytically relevant, they are not meant to achieve statistical representativeness at the population level. Future research should increase the observation period, providing a more nuanced analysis of intermediation trends as individuals age. There is a four-year gap in the data collected between W1 and W2, including the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. The final wave was collected after the worst months of the pandemic (2020), when circulation restrictions were less strict in both countries. It is worth mentioning that the significant changes observed over time might be influenced by the pandemic, although it was not part of the objective of this study to measure it. Thus, results might represent the habits adopted because of the pandemic context. Further research should evaluate whether the new informational habits remain among the older population.

Conclusion

Our study examined the preferred news intermediaries among online older adults and the trends through a communication ecology approach, as well as similarities and differences between Canada and Spain, using two waves of an online longitudinal survey conducted before and during the pandemic (2016/17 and late 2020). The timing of the data collection, before and during the Covid-19 pandemic started, accompanied by an accelerated digitalisation, particularly regarding news consumption (Van Aelst et al. 2021), and might have impacted older people’s practices.

Results show how participants in the study combined mass, social and personal intermediaries to obtain news in different ways (RQ1). Thus, older respondents formed their opinions not only through the echo chambers of social media allegedly responsible for the spread of disinformation (Sunstein 2001), but also through the consumption of other media, which might contribute to building their own opinions and combating disinformation (Terren and Borge-Bravo 2021). Otherwise, just 28% of the sample were exclusively informed through social and personal intermediaries, which could have reinforced the echo chambers only among a reduced number of the participants, among whom cognitive bias could have reinforced polarisation and users could have contributed to the spread of disinformation. These results contribute to counterbalancing broad generalisations about older people that associate their perceived lack of digital skills and media literacy with their contribution to disinformation (Dumitru et al. 2022).

Ageist prejudices often associate older adults with a lack of interest and skills in using digital technologies, and particularly a lack of digital media literacy (Dumitru et al. 2022). Indeed, previous research has ostensibly proved that older people contribute to disinformation through social media (Loos and Nijenhuis 2020). Our results contradict such ageist assumptions in the sense that most participants combine mass, social and personal intermediaries to follow the news. The combination of different sources of information may contribute to building their own opinions and offsetting the filter bubbles of the echo chambers responsible for disinformation (Terren and Borge-Bravo 2021) that can be associated with any single source of information.

Results show that preferences are anything but constant (RQ2). Even after the disruption of Covid-19 pandemic, media transitions are not always towards using more and newer media, and shifts can move in different directions. This includes people who moved from already adopted and preferred social intermediaries to traditional mass intermediaries, so despite having the knowledge and skills to use digital technologies, they chose to return to more traditional intermediaries. Changes might be related to media ideologies (Gershon, 2010), i.e. the meaning and uses attached to each medium, and influenced by the varied media trajectories of older adults. There are some differences in the changes in media preferences between Canada and Spain (RQ3). However, these might be related to the differences in the demographic background of the sample in both countries.

Implications and future work

Our results show that respondents explored new digital technologies and made decisions regarding the appropriation or rejection of media, which provides new insights into the trends and diversity of digital practices in old age. Likewise, they underline the relevance of communication ecologies in understanding the changes in communication practices over time, particularly by looking at users’ preferred media for specific communication goals. Results might be taken into account in further analysis of digital inequalities, and in the broad digitalisation of basic products and services.

Data availability

The project’s leading university (Concordia University) will make the full database available in its open repository. Within the context of this manuscript, the dataset can be considered secondary data.

Notes

GNIpc: Gross National Income per Capita

References

ACT Project (2015) Mandate. https://actproject.ca/mandate/

Allcott H, Gentzkow M (2017) Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. J Economic Perspect A J Am Economic Assoc 31(2):211–236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

Baptista JP, Correia E, Gradim A, Piñeiro-Naval V (2021) The Influence of Political Ideology on Fake News Belief: The Portuguese Case. Publications 9(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications9020023

Brashier NM, Schacter DL (2020) Aging in an Era of Fake News. Curr Directions Psychological Sci 29(3):316–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420915872

Bugeja MJ (2006) Facing the Facebook. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/facing-the-facebook/

Castells M (2009) Communication Power. Oxford University Press, New York, USA

Choudrie J, Pheeraphuttranghkoon S, Davari S (2018) The Digital Divide and Older Adult Population Adoption, Use and Diffusion of Mobile Phones: a Quantitative Study. Inf Syst Front 22:673–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-018-9875-2

Church K, de Oliveira R (2013) What’s up with WhatsApp? Comparing Mobile Instant Messaging Behaviors with Traditional SMS. MobileHCI. https://doi.org/10.1145/2493190.2493225

Colmenarejo R (2021) La digitalización como paradigma: retos éticos emergentes. In: Ayala Román AM, Fernández Dusso JJ, Rodríguez Caporalli E (Eds.) Diálogos entre ética y ciencias sociales. Teoría e investigación en el campo social. Universidad Icesi, Cali, p 161–193

Comunello F, Rosales A, Mulargia S, Ieracitano F, Belotti F, Fernández-Ardèvol M (2022) Youngsplaining” and moralistic judgements: exploring ageism through the lens of digital “media ideologies. Ageing Soc 42(4):938–961. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20001312

Cotten SR, Anderson WA, McCullough BM (2013) Impact of Internet Use on Loneliness and Contact with Others Among Older Adults: Cross-Sectional Analysis. J Med Internet Res, https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2306

del Águila-Obra AR, Padilla-Meléndez A, Serarols-Tarrés C (2007) Value creation and new intermediaries on Internet. An exploratory analysis of the online news industry and the web content aggregators - ScienceDirect. Int J Inf Manag 27(3):187–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2006.12.003

Diaz L (1995) LA TELEVISION EN ESPAÑA, 1949-1995. Prólogo de Eduardo Haro Tecglen. Alianza editorial, Madrid

Dimmick JW (2003) Media Competition and Coexistence: The Theory of the Niche, 1st edn. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Media-Competition-and-Coexistence-The-Theory-of-the-Niche/Dimmick/p/book/9780415761680

Dumitru E-A, Ivan L, Loos E (2022) A Generational Approach to Fight Fake News: In Search of Effective Media Literacy Training and Interventions. Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Design, Interaction and Technology Acceptance 291–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05581-2_22

Durick J, Robertson T, Brereton M, Vetere F, Nansen B (2013) Dispelling ageing myths in technology design. In: Proceedings of the 25th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference: Augmentation, Application, Innovation, Collaboration p. 467–476. https://doi.org/10.1145/2541016.2541040

Friemel TN (2016) The digital divide has grown old: Determinants of a digital divide among seniors. N Media Soc 18(2):313–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814538648

Gershon I (2010) The Breakup 2.0. https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9780801457395/the-breakup-2-0/

Gullette MM (2011) Agewise. University of Chicago Press; pu3430623_3430810. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/A/bo10385719.html

Guo L, A. Rohde J, Wu HD (2020) Who is responsible for Twitter’s echo chamber problem? Evidence from 2016 U.S. election networks. Inf, Commun Soc 23(2):234–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1499793

International-Telecommunication-Union (2020) ICT Price Baskets (IPB) https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Dashboards/Pages/IPB.aspx. Accessed 19 February 2023

Jenkins H, Ito M, Boyd D (2015) Participatory Culture in a Networked Era: A Conversation on Youth, Learning, Commerce, and Politics. Wiley, https://www.wiley.com/en-ca/Participatory+Culture+in+a+Networked+Era%3A+A+Conversation+on+Youth%2C+Learning%2C+Commerce%2C+and+Politics-p-9780745660707

Jenkins H, Ford S, Green J (2013) Spreaddable media, creating value and meaning in a networked culture. New York University Press, New York

LaRose R (2010) The Problem of Media Habits. Commun Theory 20(2):194–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2010.01360.x

Leiner BM, Cerf VG, Clark DD, Kahn RE, Kleinrock L, Lynch DC, Postel J, Roberts LG, Wolff S (2009) A brief history of the internet. SIGCOMM Comput Commun Rev 39(5):22–31. https://doi.org/10.1145/1629607.1629613

Linzer DA, Lewis JB (2011) poLCA: An R Package for Polytomous Variable Latent Class Analysis. J Stat Softw 42:1–29. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v042.i10

Loos E, Ivan L (2022) Not only people are getting old, the new media are too: Technology generations and the changes in new media use. New Media Soc. 14614448221101783. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221101783

Loos E, Nijenhuis J (2020) Consuming Fake News: A Matter of Age? The Perception of Political Fake News Stories in Facebook Ads. Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Technol Soc 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50232-4_6

Lugtig P (2014) Panel Attrition: Separating Stayers, Fast Attriters, Gradual Attriters, and Lurkers. Sociol Method Res 43(4), 699–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124113520305

Maglio P, Barrett R (2000) Intermediaries personalize information streams. Commun ACM 43(8):96–101. https://doi.org/10.1145/345124.345158

Marshall BL, Katz S (2016) How Old am I?: Digital Culture and Quantified Ageing. Digital Cult Soc 2(1):145–152. https://doi.org/10.14361/dcs-2016-0110

Martín-Pozuelo V (2012) Los inicios del teléfono móvil en España. ThinkBig. https://blogthinkbig.com/los-inicios-del-telefono-movil-en-espana

Masyn KE (2013) Latent class analysis and finite mixture modeling. In T.D. Little (Ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Quantitative Methods: Vol. 2. Statistical Analysis (pp. 551–611). New York, NY: Oxford University Press

Meng-Jia Wu, Zhao K, Fils-Aime F (2022) Response Rates of Online Surveys in Published Research: A Meta-analysis. Comput Hum Behav Rep 7:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2022.100206

Moscadelli A, Albora G, Biamonte MA, Giorgetti D, Innocenzio M, Paoli S, Lorini C, Bonanni P, Bonaccorsi G (2020) Fake News and Covid-19 in Italy: Results of a Quantitative Observational Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(16). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165850

Newell J, Pilotta JJ, Thomas JC (2008) Mass Media Displacement and Saturation. Int J Media Manag 10(4):131–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/14241270802426600

Nickerson RS (1998) Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises. Rev Gen Psychol 2(2):175–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175

Nimrod G (2019) Selective motion: media displacement among older Internet users. Inf Commun Soc 22(9):1269–1280. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1414865

Nylund-Gibson K, Choi AY (2018) Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Transl Issues Psychological Sci 4(4):440–461. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000176

O’Neil C (2016) Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. Crown: Publishing Group, New York, USA

Orús A (2023) Televisión: tasa de penetración en España 1997-2022. Statista. https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/475958/penetracion-de-television-en-espana/

Raboy M (1990) Missed Opportunities. McGill-Queen’s University Press, Ontario, https://www.mqup.ca/missed-opportunities-products-9780773507432.php

Rainie L, Wellman B (2012) Networked: The new social operating system. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/8358.001.0001

Riehmann P, Hanfler M, Froehlich B (2005) Interactive Sankey diagrams. In: IEEE Symposium on Information Visualization, 2005. INFOVIS 2005., p. 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1109/INFVIS.2005.1532152

Rosales A, Fernández-Ardèvol M (2018) Long-term appropriation of smartwatches among a group of older people. Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92034-4_11

Schmidt J-H, Merten L, Hasebrink U, Petrich I, Rolfs A (2019) How Do Intermediaries Shape News-Related Media Repertoires and Practices?: Findings From a Qualitative Study. Int J Commun 13:853–873. https://kops.uni-konstanz.de/handle/123456789/54463

Spain, Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2021) Survey on Equipment and Use of Information and Communication Technologies in Households 2019. https://ine.es/dynt3/inebase/en/index.htm?padre=6898

Statistics Canada (n.d.) Table 22-10-0135-01 Personal Internet use from any location by province and age group. https://doi.org/10.25318/2210013501-eng

Sunstein C (2001) Echo chambers: Bush v. Gore, impeachment, and beyond. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, https://www.worldcat.org/es/title/echo-chambers-bush-v-gore-impeachment-and-beyond/oclc/174040521

Sunstein C (2014) On Rumors: How Falsehoods Spread, Why We Believe Them, and What Can Be Done. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400851225

Terren L, Borge-Bravo R (2021) Echo Chambers on Social Media: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Rev Commun Res 9:99–118. https://www.rcommunicationr.org/index.php/rcr/article/view/94

Toffler A (1980) The Third Wave. New York. William Morrow & Co

Van Aelst P, Toth F, Castro L, Štětka V, de Vreese C, Aalberg T, Cardenal AS, Corbu N, Esser F, Hopmann DN, Koc-Michalska K, Matthes J, Schemer C, Sheafer T, Splendore S, Stanyer J, Stępińska A, Strömbäck J, Theocharis Y (2021) Does a Crisis Change News Habits? A Comparative Study of the Effects of COVID-19 on News Media Use in 17 European Countries. Digital J 9(9):1208–1238. https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-217117

Wai-Loon Ho C, Caals K, Zhang H (2020) Heralding the Digitalization of Life in Post-Pandemic East Asian Societies. J Bioethical Inq 17(4):657–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-020-10050-7

Wilkin HA, Ball-Rokeach SJ, Matsaganis MD, Cheong PH (2007) Comparing the communication ecologies of geo-ethnic communities: How people stay on top of their community. The Electronic. J Commun 17:1–2

World Bank (2023) Country and Lending Groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 15 Feb 2023

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ageing Communication and Technologies Project, funded by the Social Sciences and Research Council of Canada (SSHRCC, Ref. 895-2013-1018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the analysis, conducted the analysis, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research involved human participants and obtained ethical approval from the universities responsible for fieldwork: Universitat Oberta de Catalunya for the fieldwork in Spain and Concordia University for the fieldwork in Canada. The fieldwork is part of the Ageing Communication and Technologies Project, funded by the Social Sciences and Research Council of Canada (SSHRCC, Ref. 895-2013-1018).

Informed consent

Panellists were informed of the objectives and procedures of the study and how personal data would be treated and agreed to participate before the beginning of the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosales, A., Fernández-Ardèvol, M., Gómez-León, M. et al. Old age is also a time for change: trends in news intermediary preferences among internet users in Canada and Spain. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 455 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02940-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02940-7