Abstract

State-owned enterprises have responsibilities to conduct head office’s strategies to make profits, to execute public programs and obligations, to maintain their viabilities, to serve customers, and to manage employees. Those prompt their branch managers not only to explore their environment but also to face a goal conflict situation. This study is to investigate the effects of branch managers’ boundary spanning activities and resource orchestration on the performance of branch offices in the dynamics of environmental uncertainty and goal conflict. This study employs structural equation modeling on one of the most prominent state-owned banks in Indonesia, with 201 branch offices as the unit of analysis, and 186 branch managers as respondents. The results of this study show that boundary spanning activities have a positive and significant relationship with resource orchestration. Meanwhile, both boundary spanning activities and resource orchestration are to influence the performance of branch offices. However, the influence varies widely, depending on environmental uncertainty and goal conflict experienced by branch managers. Furthermore, this study delves into an interesting phenomenon, that goal conflict situation, instead of reducing boundary spanning activities, it increases them but has no impact on resource orchestration. This closely relates to the culture of Indonesia as a nation with high power distance, low individualism, low masculinity, and low indulgence which represent preferences to prioritize workplace harmony, obey supervisors, and be loyal to the workplace.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

State-owned Enterprises (SOEs) are regulated by the state through full, majority, or significant minority ownership (ADB Institute 2017). By managing services in various essential and strategic sectors, SOEs make substantial contributions to the economic development, public well-being, and sound public finances of numerous developed and developing countries (ADB Institute 2017; IMF 2020; OECD 2021; ADB 2022). According to the 2017 OECD study of thirty-nine countries, excluding China, SOEs employ more than 9.2 million people and being worth $2.4 trillion (IMF 2019). SOEs have the potential to play a vital role in addressing technological disruption, digital transformation, and climate change (ADB 2022).

Governments have utilized SOEs including state-owned banks (SOBs) for assistance in the management of crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, during which SOEs have actively supported the public health emergency and the recovery process of the economic crisis that followed (IMF 2020; ADB 2022). In many countries, SOBs are even required to provide loans to families and micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (IMF 2020; Panizza 2023). This is in line with the social and developmental, also political and institutional functions of SOBs (Sapienza 2004; Douglas 2008; La Porta et al. 2002).

Currently, SOBs are dealing with a volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous environment (Bennet and Lemoine 2014), and also with a variety of external factors, e.g., unpredictable customer needs, intense competitions, dominance of technological change, digital transformation, and the COVID-19 pandemic (Carbonara and Caiazza 2010; Bai et al. 2020; Nachit and Belhcen, 2020; OECD 2020). To maintain their profitability and going concern, SOBs’ business lines including branch offices must be flexible and adaptive to environmental changes and uncertainties (Delozier and Burbach 2021; Zhang and Li 2021). Those are affecting long-term strategic planning and innovation performance of banks (Javidan 1984), reducing the availability of bank financing, threatening the efficiency and operational performance of banks, and declining the stability of the banking sector (Baum et al. 2021). The greater the environmental changes and uncertainty, the more branch managers of SOBs need to do boundary spanning activities (Zhang and Li 2021).

An organization have an interdependent relationship with their environment (Monteiro and Birkinshaw 2016), and will be dependent on its environment not only to get critical resource inputs, but also to distribute products and services as the outputs (Aldrich and Herker 1977). Boundary spanning activities are skills for building connections that transcend institutional, professional, organizational, or related boundaries (Burbach et al. 2023), such as negotiations, contracting, and cooperation building, as to manage interactions across boundaries (Stock 2006). In general, there are multi levels of actors in an organization that contribute to boundary spanning activities, namely top management, middle management (including branch managers), and lower management which consists of supervisors and staffs (Dasgupta 2015; Haas 2015; Alfoldi et al. 2017; Natarajan et al. 2019; Drion 2021). When handling customers, branch managers undertake boundary spanning activities, such as communicating customer needs to management, representing the bank to the customers and other parties, and acting as ambassadors, task coordinators, scouts, guards, and service providers (Ancona and Caldwell 1992; Bettencourt et al. 2005; Brion et al. 2012; Subramony et al. 2021).

Besides performing boundary spanning activities, branch managers must be able to use available resources and orchestrate them efficiently. The concept of resource orchestration explains how managers combine firm resources effectively to achieve performance (Hughes et al. 2018) and emphasizes that the superior performance of a firm could be manifested through combination of resources, capabilities, and managerial acumen (Helfat et al. 2007; Sirmon et al. 2007; Sirmon et al. 2011). Boundary spanning activities and resource orchestration are two crucial daily works of SOBs’ branch managers, which significantly influence the performance of the branch office through customer satisfaction (Bergami et al. 2021) and organizational resilience (Ahmed 2022).

Furthermore, their role as branch managers often put them in an intra-individual goal conflict situation of two opposites, for example, between their job to generate profit and their responsibility as financial intermediaries to national economic recovery programs (Gorges and Grund 2017; Jaser 2021). SOBs branch managers work amidst these conflicting goals, while attempting to respond to pressures from their head offices (Boelens 2020) and to reduce goal conflict which appears because of institutional logic (Keij and van Kranenburg 2022).

This study evaluates the impacts of perceived environmental uncertainty and intra-individual goal conflict experienced by SOBs’ branch managers on the boundary spanning activities and resource orchestration which they do to improve the performance of their branch offices. Several previous studies on this topic have found a link between perceived environmental uncertainty and boundary spanning activities (Leifer and Huber 1977; Leifer and Delbecq 1978; Schwab et al. 1985; At-Twaijri and Montanari, 1987); between perceived environmental uncertainty and resource orchestration (Ahuja and Chan 2017; Badrinarayanan et al. 2018; Choi et al. 2020; Chen and Tian 2022; Temouri et al. 2022); and between resource orchestration and perceived organizational performance (Wales et al. 2013; Miao et al. 2017; Tuo-Chen and Qiao 2017; Peat and Permann-Graham 2020; Kristoffersen et al. 2021). Furthermore, previous studies only examine the indirect impacts of intra-individual goal conflict on boundary spanning activities (Schotter and Beamish 2011), indirect impacts of intra-individual goal conflict on resource orchestration (Omotosho and Anyigba 2019), and indirect impacts of boundary spanning activities on resource orchestration (Merindol and Versailles 2018).

This study aims not only to confirm the findings of previous studies but also to provide novelty to researches on the direct impacts of intra-individual goal conflicts on both boundary spanning activities and resource orchestration, as well as the direct impacts of boundary spanning activities on resource orchestration.

State-owned banks in the Indonesian context

According to Article 2 Paragraph 1 of the Law Number 19 of 2003 of the Republic of Indonesia on SOEs (Law Number 19, 2003), SOEs have five purposes as follows: 1) to contribute to the development of national economy; 2) to gain profits; 3) to provide high quality and adequate goods and/or services; 4) to become pioneers in any business activities that have not been carried out by private sector and cooperatives; and 5) to provide guidance and assistance to entrepreneurs from lower economic class, cooperatives, and the community. Thus, apart from being demanded to be able to survive and to gain profits for the government, SOEs must also give access to financial services for Indonesian people, particularly those living in underdeveloped areas of Indonesia.

In Indonesia, there are four SOBs, which constitute one of the four most prominent SOEs clusters that make the highest profit contribution for Indonesian government, along with the energy cluster, the telecommunications and media cluster, and the mineral and coal cluster (The Ministry of State-Owned Enterprises of the Republic of Indonesia 2022). The four SOBs dominate the Indonesian banking industry as shown in Table 1. The Government of Indonesia needs to maintain the existence of healthy SOBs to be able to serve their financial intermediary function properly and generate profits for the government (Gianni et al. 2020). In addition, as assessed by Fitch (www.fitchratings.com), Indonesian SOBs play a significant role in supporting the government’s programs to develop micro, small, and medium enterprises, which is difficult or even almost impossible for private banks to offer (Special Report: Indonesian State-Owned Banks – Peer Review 2023).

Historically, based on information taken from the annual reports of all SOBs, the four Indonesia’s SOBs consist of three Dutch banks from the colonial era of the Dutch East Indies Government in Indonesia that have been nationalized and another bank which is the first and oldest to be established and owned entirely by the Indonesian government. As the first bank belonging to the Republic of Indonesia, the latter bank was originally established as a central bank but was later mandated other functions as a development bank and finally as a state-owned commercial bank with the aim of improving the economy of Indonesian people and participating in national development. This SOB has a long and unique history along with the history of Indonesian independence also becomes the first Indonesian SOB to officially have foreign branches. These facts underlie the reasons for conducting this study in this state-owned bank.

Indonesian Ministry of SOEs has core values for all SOEs including SOBs those are: trustworthy, competent, harmonious, loyalty, adaptive, and collaborative (www.bumn.go.id). Those values are implemented to be SOBs’ shared identity and daily shared corporate culture for sustainable performances, not only for employees but also for managements. Besides that, the domination of those four SOBs in Indonesian banking industry is seen from the number of their networks (51.65%), third party funds (41.26%), and assets (40.72%) comparing to other regional development and commercial banks. Hence, the selection of the examined Indonesian SOB was expected could represent Indonesian SOEs in common.

Literature review and hypothesis development

This study aims to investigate the effects of perceived environmental uncertainty and intra-individual goal conflict experienced by the SOB’s branch managers on their boundary spanning activities and resource orchestration to achieve their goals set by the head office as indicated by the perceived organizational performance of the branch offices under their management.

Literature review

Perceived environmental uncertainty (PEUN)

Perceived environmental uncertainty (PEUN) can be defined as an individual perception of inability to accurately predict organizational environment due to unavailability of information or inability to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant data (Milliken 1987); insufficient information about environmental activities and/or inability to predict external changes and their impacts on organizational decisions (Sawyerr 1993); or the lack of important information about the business environment experienced individually by each member of the management (Duncan 1972; Jahanshahi and Brem 2020). Milliken (1987) classified environmental uncertainty into three types: 1) state uncertainty, the inability to predict environmental conditions; 2) effect uncertainty, the inability to predict the impacts of the environmental changes; and 3) response uncertainty, the inability to predict the consequences of a response choice to environmental change.

Intra-individual goal conflict (GCFL)

Goal conflict is one of the crucial factors in motivation theory (Gray et al. 2017). According to Locke and Latham (2006), goal setting and target fulfillment affect task performance. However, problems arise when an individual is assigned multiple goals at the same time; if these multi-goals lead to unbalanced/incongruent results or competition for the same resources, goal conflict will occur (Gray et al. 2017; Gorges and Grund 2017). Intra-individual goal conflict (GCFL) is the degree of incompatibility between expected performance and multi-goals assigned (Locke et al. 1994; Slocum et al. 2002). GCFL can be categorized into three groups: 1) conflict between assigned external goals and personal goals; 2) conflict between tasks those must be completed at the same period of time; and 3) conflict between multiple targets of the same task (Locke et al. 1994; Locke and Latham 2002; Slocum et al. 2002).

Boundary spanning activities (BSAC)

Boundary spanning activities (BSAC) can be defined as connecting pins between the organization and its environment (Organ, 1971). BSAC can be classified into several sets of categories, i.e., ambassador, task coordinator, scout, and guard activities (Ancona and Caldwell 1992); spearheading, facilitating, reconciling, and lubricating (Birkinshaw et al. 2017); selecting (guard and scout), translating (ambassador and interpreter), and connecting (task coordinator and entrepreneur) (van den Brink et al. 2019); and external representation, information processing, and networking (Wu 2022). According to Karimikia et al. (2022), BSAC are conducted by individuals, teams, and organizations to implement processes, strategies, or behaviors to accelerate decision making, conflict resolution, learning, and innovations. Meanwhile, Santistevan (2022) argued that coordination through BSAC is done to facilitate lateral collaboration and alignment within an organization as an effective bridge between units in the organization.

Resource orchestration (ROCR)

The concept of resource orchestration (ROCR) explains how managers combine company resources effectively to achieve performance targets (Hughes et al. 2018); it is a combination of resources and capabilities as well as managerial acumen to realize organization performance (Helfat et al. 2007; Sirmon et al. 2007; Sirmon et al. 2011; Chadwick et al. 2015). ROCR is rooted in asset orchestration and resource management (Sirmon et al. 2007; Helfat et al. 2007; Sirmon et al. 2011). Asset orchestration comprises of two processes, namely search/selection and configuration/deployment (Helfat et al. 2007; Peuscher, 2016), whereas resource management consists of three processes, i.e., structuring, bundling, and leveraging (Sirmon et al. 2007). Hitt et al. (2011) described ROCR as a managerial action in the process of structuring a firm’s resource portfolio, bundling resources to develop relevant capabilities, and leveraging these capabilities to gain various competitive advantages. ROCR is a combination of the roles of top, middle, and lower managements (Chadwick et al. 2015). In performing ROCR, synchronization of all levels is highly necessary so that middle managers are not only able to achieve goals but also give corrections for dyadic information flow between levels (Carnes et al. 2022).

Perceived organizational performance (PPER)

Firm or organizational performance is the most relevant variable in studies on organization and strategic management (Santos and Brito 2012; Miller et al. 2013). The problem is often about understanding how a firm can gain sustainable competitive advantages to produce sustainable superior or above-average performance (Tang and Liou 2010). Measurement of organizational performance can be taken using two models: objective (independent and distant from the observer, not too biased, but not always available all the time); and subjective (usually depending on and involving perceptions, opinions, impressions, and assessments from the observer); which subjective performance measurement can be an alternative if no objective performance measurement is available (Richard et al. 2009). Singh et al. (2016) stated that subjective or perceived organizational performance (PPER) measurement data from managers are consistent, valid, and reliable, making it possible to use them as research data. The concept of PPER refers to the subjective measurement from employee perceptions of overall organizational performance compared to competitors in the same sector, strategies, and reward system (Berberoglu 2018).

Hypothesis development

Relationships between perceived environmental uncertainty (PEUN), boundary spanning activities (BSAC), and resource orchestration (ROCR)

SOBs’ branch managers who have high PEUN tend to perform more BSAC (Au and Fukuda 2002). If they have experiences in serving various functions, this leads to a higher contribution rate in doing BSAC (Ancona and Caldwell 1989). According to Leifer and Huber (1977), PEUN has a positive relationship with BSAC only if the structure of the organization is designed to respond to environmental changes. This is in line with another study by At-Twaijri and Montanari (1987) which found that PEUN significantly and positively influences BSAC. Furthermore, BSAC reduces information asymmetry and eventually increases the level of the firm’s strategic communication, thereby increasing the firm’s trustworthiness, although BSAC has no direct impact on the firm’s performance (Zhang et al. 2015). However, Au and Fukuda (2002) rejected the hypothesis that the higher the PEUN the higher the BSAC. Lysonski and Woodside (1989) explained that PEUN has a negative relationship with BSAC; the level of BSAC decreases if PEUN increases; but this can only occur because of the inability of managers to deal with higher PEUN so that they passively follow organizational policies and decisions.

Ahuja and Chan (2017) argued that PEUN moderates (strengthens/weakens) the stages of ROCR (Sirmon et al. 2007). Meanwhile, Badrinarayanan et al. (2018) suggested that the more complex the PEUN the greater the level of ROCR. According to Choi et al. (2020), entrepreneurial orientation has a strong and positive impact on performance when PEUN and ROCR are at high intensity. Furthermore, an effective and synergic combination of PEUN and ROCR will result in the achievement of digital transformation (Chen and Tian 2022), and the higher the PEUN the higher the tendency of the organization to choose new business exploration as part of ROCR (Temouri et al. 2022).

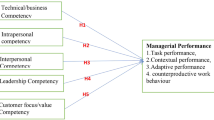

From the explanations above, the first hypothesis of this study is that PEUN has a positive influence on both BSAC and ROCR, with sub-hypotheses as follows:

H1.a. PEUN has a positive influence on BSAC.

H1.b. PEUN has a positive influence on ROCR.

Relationships between intra-individual goal conflict (GCFL), boundary spanning activities (BSAC), and resource orchestration (ROCR)

Based on the previous literatures, there are almost no direct relationships investigations found between GCFL, BSAC, and ROCR, but only the indirect impacts of GCFL on BSAC (Schotter and Beamish 2011) and on ROCR (Omotosho and Anyigba 2019); and of BSAC on ROCR (Merindol and Versailles 2018). The majority related literatures are using other organizational variables (goal commitment, goal difficulty, goal priority, goal uncertainty, goal ambiguity, goal alignment, goal diversity, and goal achievement or performance) as dependent research variables. Some related literatures are as follows.

GCFL reduces commitment to goals and decreases performance (Locke and Latham 2013), reduces the achievement of new goals (Kehr 2003), and is associated with the emergence of uncertainty and ambiguity (Gupta et al. 1999). Slocum et al. (2002) stated that GCFL has a negative influence on both goal commitment and organizational performance (PPER). According to Cheng et al. (2007), the more difficult the targets to be achieved the higher the GCFL, and the higher the GCFL the lower the PPER; thus, the difficult targets to achieve will indirectly lead to low PPER through GCFL as the mediator. This is in line with a study by Staniok (2014) which found that GCFL has a negative impact on employee goal commitment and that it will significantly and negatively moderate the relationship between manager goal priority and employee goal commitment.

According to Omotosho and Anyigba (2019), GCFL experienced by managers is a moderator of the relationship between ROCR and PPER, where GCFL is goal alignment (in situations of intense conflict) and goal diversity (in situations of more intense conflict), while ROCR is the entrepreneurial process in the form of strategic thinking, strategic planning, and exploitation of capabilities.

Based on the explanation above, the second hypothesis as the first novelty contribution from this study is that GCFL directly has a negative influence on both BSAC and ROCR, with sub-hypotheses as follows:

H2.a. GCFL has a negative influence on BSAC.

H2.b. GCFL has a negative influence on ROCR.

Relationships between boundary spanning activities (BSAC) and resource orchestration (ROCR)

A few studies about the link between BSAC and ROCR already exist in the literature, but mostly indirect relationships and in the lenses of BSAC as enablers for ROCR (Merindol and Versailles 2018; Johnson 2007). According to Xue and Woo (2022), BSAC provides the necessary resources to subordinates while simultaneously managing the external environment and creating organizational performance. Meanwhile, BSAC also had roles to facilitate in gathering resources and to support resource mobilization (Wilemon 2014; Jun 2018; Wei et al. 2020). Cui and Han (2022) wrote that the firm needs to build BSAC to obtain external resources and to maximize ROCR process. Brion et al (2012) emphasized that BSAC supported in accessing and enabling ROCR such as: combining knowledge, coordinating with stakeholders, and lobbying for top management support for resources competition and managerial attention. However, there is no direct and significant correlation between BSAC and PPER (Satheesh et al. 2023).

The explanation above also underlies the second novelty contribution from this study, the development of the third hypothesis of this study is that BSAC has a direct positive influence on ROCR as follows:

H3. BSAC has a positive influence on ROCR.

Relationship between resource orchestration (ROCR) and perceived organizational performance (PPER)

ROCR positively moderates or strengthens the relationship between supply chain collaboration and PPER (Tuo-chen and Qiao 2017), between HR system and PPER (Peat and Permann-Graham 2020), and between entrepreneurial orientation and PPER (Wales et al. 2013; Choi et al. 2020). Miao et al. (2017) reviewed the relationship between human capital and social capital with PPER, where ROCR mobilizes firm resources and is proven to mediate the relationship. Meanwhile, Kristoffersen et al. (2021) also found that ROCR strongly and positively mediates the relationship between business analytics capability and PPER. This explanation leads to the development of the fourth hypothesis of this study as follows:

H4. ROCR has a positive influence on PPER.

The research model of this study is as seen in Fig. 1.

Method

Based on the development of the hypotheses, investigation was performed on the relationship between variables using covariance-based Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). This study was held in one of the four Indonesian SOBs, namely the first and oldest bank entirely established and owned by the Indonesian government. The analysis unit of this study is the 201 branch offices of the SOB which perform complete bank business and services (full branches or stand-alone branches). The population is 201 branch offices, and the respondents are 186 branch managers (92.54%) who are officially assigned as full-time managers of the branch offices located in Indonesia, by excluding temporarily branch managers and the managers of foreign branch offices. Overall, 186 respondents were considered homogeneous, more than 90% are male, more than 80% are 46 years old, 80.65% of the total respondents have work experience of more than 20 years, 99.46% of them hold postgraduate degree, and all respondents (100%) represent 17 Regional Offices of the examined SOB.

The operationalization for each variable was completed with variable definitions, dimensions, indicators/questionnaires, and references. Research questionnaires use a 6–point Likert scale starting from 1 (very disagree) to 6 (very agree). All questions are adopted and translated to Indonesian from the literature, and improvement were made through in-depth discussions with an expert team from related SOBs. Necessary question addition and wording modification were done to make the questionnaires simpler, more contextual, and easier to understand.

The first variable, Perceived Environmental Uncertainty (PEUN), is defined as the inability to accurately predict environmental changes as an impact of no relevant information (Milliken 1987; Silva and Ferreira 2017). This variable consists of three dimensions and ten indicators sourced from Silva and Ferreira (2017). Some wordings in the questionnaire on PEUN are as follows: (1) It is hard for me to monitor business trend in my branch office’s environment; (2) I can identify impacts of environmental changes on activities in my branch office; and (3) Head Office has adjusted the response based on environmental changes in my branch office. The second variable, Intra-individual Goal Conflict (GCFL), is defined as incompatibility or misalignment caused by multi-goals that must be accomplished (Locke et al. 1994; Slocum et al. 2002). This variable consists of three dimensions and ten indicators taken from Kwan et al. (2013), Locke and Latham (2013), and Lee et al. (1991). Some points in the questionnaire regarding GCFL include: (1) Some targets assigned to me are contradictive with my personal values; (2) I have contradictive targets from different working units (or even from the same working unit); and (3) A few targets given to me do not encourage me to maintain my performance.

Furthermore, Boundary Spanning Activities (BSAC) as the third variable is defined as a set of communication and coordination activities performed by individuals both intra- and inter-organization to integrate activities across cultures, institutions, and organizational contexts (Schotter et al. 2017). This variable comprises of five dimensions and nineteen indicators proposed in studies by Ancona and Caldwell (1992) and Bettencourt et al. (2005). Some statements in the questionnaire on BSAC are: (1) I protect my branch office activities from any disturbing information or requests from outside of my branch office; (2) if needed, I would like to coordinate with other parties outside my branch office to support me to complete my activities; (3) I try to find out about the performance of branch offices of other bank in my working area; (4) I keep some information about my branch office and will only will share it with others if necessary; and (5) I handle customers by following rules in the guidance book. The fourth variable, resource orchestration (ROCR), consists of three dimensions and thirteen indicators from Berseck (2018) and Carnes et al. (2022). A few statements in the questionnaire about ROCR are as follows: (1) I recruit employees for some positions in my branch office by my own; (2) I have assets maintenance program in my branch office for long-term usage; and (3) I give instructions to all employees in my branch office to help each other by cross utilizing the available resources to support daily activities.

The fifth variable, Perceived Organizational Performance (PPER) is defined as factors to show how well an organization achieves its goals (Richard et al. 2009). This variable consists of two dimensions and eleven indicators taken from Delaney and Huselid (1996). A few points in the questionnaire regarding PPER include: (1) In my opinions, my branch the performance of office for the last three years is better than that of the branch offices of other bank in my working area in aspects of product quality, services, or programs; and (2) In my opinions, the performance of my branch office for the last three years is better than that of the branch offices of other bank in my working area in aspects of marketing.

Then the questionnaires, in cooperation with the examined SOB, were sent to the intended branch managers using online form, filled by themselves, monitored timely, and collected periodically through networks and services division of the examined SOB.

SEM method requires a minimum number of samples of around ten times the number of indicators (Hair et al. 2019). As this study has sixty-one indicators, it ideally needs around 610 respondents. This means that this study did not meet the requirement for analysis with the SEM method. To overcome this limitation, this study applied the parceling method by counting Latent Variable Score (LVS), which was accumulating or aggregating indicators individually to be one or two new parcels to be used as new indicators for latent variables (Cattell and Burdsal 1975; Kishton and Widaman 1994). Parceling aims to solve problems in research, especially in terms of data limitation or data loss (Enders and Bandalos 2001; Graham 2003). According to Little et al. (2013), key advantages of parceling are as follows: higher reliability, greater communality, lower likelihood of distributional violations, fewer parameter estimates, lower indicator-to-sample size ratio, and reduced sources of sampling error. However, parceling might lead to misrepresentations of the phenomena under study, unless fulfilling some of the conditions as follows: the study purpose is to examine the structural relationships among multiple constructs, the scale measurement is unidimensional structure, the data are not optimal, having correlated error, the size is small, and the model is complex (Matsunaga 2008).

This study had five unobserved latent variables, sixteen unobserved dimensions, and sixty-one observed indicators. Therefore, this research to employ parceling method with minimal potential of misrepresentations, for meeting at least some conditions: the purpose is to examine structural model, having multiple constructs, the data size is small, and the model is complex. Following the method, the sixty-one indicators were accumulated into one composite for each dimension to obtain the observed indicators. Therefore, the required minimum number of samples changed to 160 people, meaning that the minimum requirement for analysis with the SEM method was achieved with 186 respondents.

Analysis using covariance-based SEM for the measurement model requires the value for standard loading factor (validity test) of ≥0.50, Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient for reliability test of ≥0.90, and overall reliability value consisting of composite reliability (CR) of ≥0.70 and variance extracted (VE) of ≥ 0.50 (Hair et al. 2019; Hair et al. 2021). Meanwhile, in one-tailed test with a significance level of 95%, t-values can be stated as significant only if t ≥t-statistics 1.65, meaning that the hypotheses were supported by available data (Hair et al. 2021).

Data analysis

Pre-test data was conducted to forty-five purposively selected respondents, who the writer’s colleagues with experience as branch managers of banks. Based on the validity test, fourteen indicators are invalid (three from PEUN, five from GCFL, four from BSAC, and two from ROCR). Meanwhile, the value of the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient is 0.936 in the reliability test, which is higher than the standard of 0.90 (Hair et al. 2019), meaning that the reliability level is excellent. Based on these two tests, the wording of the questionnaires was then modified and improved through discussion with an expert team from the examined SOB prior to field data sampling.

All respondents have experienced all types of intra-individual goal conflict, but they get support from the head office as proven by the positive indicators which were as dominant as the negative indicators. Regarding the changing external environment, respondents need to improve their understanding of what changes are happening and how to deal with the competitive landscape between banks in their working areas. According to the respondents, the head office’s responses to environmental changes need to be adapted to the local conditions of each branch office. Furthermore, the respondents mostly do two types of boundary-spanning activities, namely service delivery and ambassador activities. On the other hand, they also must conduct two dominant activities, namely (1) monitoring the environment by identifying and observing the environment to draw innovative ideas, and (2) maintaining the images of the branch office by filtering information that may or may not be published. However, respondents have limited authorities in orchestrating their resources, causing them to focus only on optimizing the usage of existing resources based on their authorities and suggesting the programs to the head office. Their innovation activities seem dominant but are limited by the capacity of the branch office for resources and authorities. Finally, the performance of branch offices needs to be improved, especially in terms of the ability to retain employees and market share.

The measurement model with five variables (PEUN, GCFL, BSAC, ROCR, and PPER) was evaluated using covariance-based SEM, where indicators with a loading factor (LF) below 0.5 were considered invalid and omitted (Hair et al. 2019). Then the measurement model was re-evaluated until all indicators had a loading factor above 0.5. After that, composite reliability (CR) and variance extracted (VE) were calculated, where variables with CR value of ≥0.7 and VE value of ≥0.5 based on Hair et al. (2019) were considered reliable. Based on results of the tests for PEUN (CR = 0.91; VE = 0.57), BSAC (CR = 0.96; VE = 0.57), ROCR (CR = 0.92; VE = 0.53), and PPER (CR = 0.96; VE = 0.75), the final indicators were obtained, all of which are valid and reliable. As for the GCFL variable, despite having valid final indicators with a CR value of 0.86 ( > 0.7), it had a VE value of 0.48 (marginal due to being close to the minimal value of 0.5). According to Lam (2012) and Huang et al. (2013), if a variable has a CR value of >0.7, it can be considered reliable although the VE value is <0.5, only if the VE value is still >0.4. This means that the GCFL variable in this study is also reliable.

After parceling, next measurement was performed on the overall model; 16 indicators had SLF > 0.5, CR = 0.98 (>0.7), and VE = 0.79 (>0.5), thus being considered valid and reliable. Then, the goodness of fit test was applied to all research variables (PEUN, GCFL, BSAC, ROCR, and PPER) for overall model. The result shows that from eleven criteria (Chi Square, Goodness of Fit Index, Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index, Comparative Fit Index, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual, Incremental Fit Index, Relative Fit Index, and Parsimony Normed Fit Index), almost all majorities are of good fit. Only one criterion did not meet the requirement of good fit, namely the Chi-square. Therefore, the overall model was considered a good fit.

Testing was proceeded towards structural model for all research variables (PEUN, GCFL, BSAC, ROCR, and PPER) after parceling. Hypothesis testing was done to see t-values from each diagram. According to Hair et al. (2021), in one-tailed test with a significance level of 95%, t-values can be stated as significant only if t ≥ 1.65 (supported by available data). Conversely, if t ≤ 1.65, t-values can be considered insignificant (not supported by available data). Figure 2 below describes the relationship between all latent variables with each of their indicators with a SLF > 0.5 (valid). Of six relationships between latent variables, two relationships are stated as not supported by available data as follows: GCFL – ROCR with a t-value of −1.32 (the same negative value as proposed but below the condition) and t-statistics of <1.65; and GCFL – BSAC with a t-value of 4.36 (positive value that differs from proposed negative value but above the condition) and t-statistics of >1.65. Meanwhile, the remaining four relationships have t-values > 1.65 and stated as significantly supported by available data (PEUN – BSAC, PEUN – ROCR, BSAC – ROCR, and ROCR – PPER).

Furthermore, the requirement of goodness of fit statistics was checked (See Table 2), and the results indicate that almost all 11 criterions (Chi Square, Goodness of Fit Index, Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index, Comparative Fit Index, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual, Incremental Fit Index, Relative Fit Index, and Parsimony Normed Fit Index) are of good fit. Only two criterions did not meet the requirement, i.e., Chi square and standardized RMR, so that the overall model can still be considered a good fit.

Table 2 presents the conclusions derived from the results of the analyses above.

Discussion

Perceived environmental uncertainty, boundary spanning activities, and resource orchestration

This study confirms that perceived environmental uncertainty (PEUN) has a positive and significant influence on both boundary spanning activities (BSAC) and resource orchestration (ROCR) performed by respondents; the higher the PEUN, the higher both the BSAC and the ROCR. This supports the findings of previous studies from Schwab et al. (1985), Leifer and Delbecq (1978), Leifer and Huber (1977), and At-Twaijri and Montanari (1987), that PEUN has impact on BSAC. The result of this study also supports previous studies from Ahuja and Chan (2017), Badrinarayanan et al. (2018), Choi et al. (2020), Chen and Tian (2022), and Temouri et al. (2022) that PEUN has impact on ROCR. This finding is supported by the responses of the questionnaire which had high loading factor scores that branch managers responded to uncertainty by observing and learning from the environment, choosing, and filtering information to support their programs, and providing more service excellence for their customers based on information they gain from the environment. After responding to uncertainties, branch managers tried to achieve their goals by managing knowledge (encouraging employees to search new knowledge from outside the organization and share it with each other).

Intra-individual goal conflict, boundary spanning activities, and resource orchestration

The hypothetical proposition, that intra-individual goal conflict (GCFL) has a negative and significant correlation with both boundary spanning activities (BSAC) and resource orchestration (ROCR) performed by respondents, is not supported with available data. Nevertheless, this study found an interesting phenomenon as first novelty contribution from this study that instead of reducing the level of BSAC, the higher GCFL directly leads to the higher BSAC, but however has no impact on ROCR. This finding is in contrast with existing literature, which some previous studies have explained that GCFL indirectly has negative impacts on PPER through its organizational variables (Locke et al. 1994; Slocum et al. 2002; Cheng et al. 2007; Staniok 2014), and that GCFL has indirect impacts on the relationship between ROCR and PPER (Omotosho and Anyigba 2019).

Based on the results of the questionnaire, the goals assigned by head office to branch managers are not perceived as intra-individual goal conflict and branch managers will try their best to accomplish these goals by implementing BSAC and ROCR as needed. To minimize GCFL, branch managers must use limited resources, find assistances from others, negotiate conditions with related parties, to accomplish their goals, and optimize their available resources to support the daily operation, competency development, and knowledge management of their branch office.

The impacts of intra-individual goal conflict on boundary spanning activities and resource orchestration

The condition that GCFL positively impacts BSAC but has no impact on ROCR can be explained from the concept of nation culture that influences individuals on how to behave to their superiors, peers, subordinates, tasks, and many factors inside or outside their organization (Hofstede et al. 2010; Hofstede 2011). According to Hofstede et al. (2010) and Hofstede (2011), there are six dimensions of nation culture: (a) power distance (low score means all organization members are equal to each other, while high score means organization is arranged in an unequal structure from superiors to subordinates); (b) uncertainty avoidance (low score means having tolerant and comfort with uncertainty, high score means being eager to get regularities and standard structures); (c) individualism (taking care of themselves and the smallest family) versus collectivism (getting together and loyal to the big family); (d) masculinity (assertive and competitive) versus femininity (humble and attentive); (e) long-term orientation (focus on the future and adaptive) versus short-term orientation (focus on the past/present and standard); and (f) indulgence (individual happiness is very important) versus restraint (individual happiness is not as important as or below social norms).

From these six dimensions on each aspect of nation culture, Indonesia obtains high power distance (78), low individualism (14), low masculinity (46), low uncertainty avoidance (48), high long-term orientation (62), and low indulgence (38). Therefore, Indonesian people are described as being hierarchical (subordinates must obey superiors) and loyal to the big family (in this case, the head office), putting appearances or prestige first, considering harmony and kinship in workplace as important, having pragmatic orientation, being adaptive to various situations, contextual, and on time, and also believing that social norms limit their behaviors (Hofstede et al. 2010).

Based on the explanation of Indonesia’s nation culture above, it is understandable that respondents choose to put harmony in workplace, obey to superiors, and loyal to their workplace that they consider as big family rather than to choose options between intra-individual goal conflicts they experienced.

Boundary spanning activities, resource orchestration, and perceived organizational performance

The hypothesis that boundary spanning activities (BSAC) have a direct positive and significant correlation with resource orchestration (ROCR) was supported by available data; the higher the BSAC, the higher the ROCR. In addition, resource orchestration (ROCR) has a positive and significant correlation with perceived organizational performance (PPER) of respondents’ branch offices was also supported with available data; the higher the ROCR, the higher the PPER.

This finding is the second novelty contribution from this study. Mostly previous literatures are using the lenses of BSAC as enablers for ROCR or in other words that BSAC has indirect influence on ROCR (Johnson 2007; Brion et al. 2012; Wilemon 2014; Jun 2018; Merindol and Versailles 2018; Wei et al. 2020; Cui and Han 2022; Xue and Woo 2022; Satheesh et al. 2023). Meanwhile, this study finds there is a direct positive and significant relationship between BSAC and ROCR. Furthermore, this finding also supports previous studies on the relationship between ROCR and PPER, such as those conducted by Tuo-chen and Qiao (2017), Peat and Permann-Graham (2020), Wales et al. (2013), Miao et al. (2017), and Kristoffersen et al. (2021).

Based on the responses of the questionnaire which have high loading factor scores, branch managers can be depicted as performing both BSAC and ROCR at the same time with the same spirit to accomplish goals assigned by the head office through: searching information from competitors to encourage employees in creating products and services innovation, protecting the image of the organization from fraud, and solving customers’ problem on time using the limited resources available in their branch office.

Conclusion

Based on the analysis and discussion above, four findings can be concluded as follows: 1) perceived environmental uncertainty has a positive and significant influence on boundary spanning activities and resource orchestration carried out by respondents (the higher the perceived environmental uncertainty, the higher the boundary spanning activities and resource orchestration); 2) instead of having negative influences, intra-individual goal conflict experienced by respondents positively and significantly affects boundary spanning activities (the higher the intra-individual goal conflict, the higher the boundary spanning activities), but has no effect on resource orchestration; 3) boundary spanning activities positively and significantly influence resource orchestration (the higher the boundary spanning activities, the higher the resource orchestration); and 4) resource orchestration by respondents has a positive and significant influence on the performance of the branch offices (the higher the resource orchestration, the better the branch office performance). Furthermore, instead of intra-individual goal conflict has a negative impact on boundary spanning activities, it influences them positively, describes Indonesia’s nation culture with preferences to prioritize workplace harmony, obey supervisors, and be loyal to the workplace.

Based on the path diagram analysis, the path with the highest loading factors is on the path of perceived environmental uncertainty – boundary spanning activities – resource orchestration – perceived organizational performance. This path occurs and is explained as follows: when respondents encounter high perceived environmental uncertainty, they try to reduce or stabilize the uncertainty through increasing boundary spanning activities, and then increasing resource orchestration as optimal as they can, to accomplish the performance of their branch office.

Theoretical and managerial contributions

There are three theoretical contributions from this study. First, it confirms previous studies on two hypotheses: environmental uncertainty has a positive and significant correlation with both boundary spanning activities and resource orchestration, and resource orchestration has a positive and significant relationship with perceived organizational performance. Second, it strengthens previous studies on hypothesis: resource orchestration has a positive and significant correlation with perceived organizational performance. Third, it contributes to theoretical novelties regarding a direct positive and significant correlation between boundary spanning activities with resource orchestration, and relationships between intra-individual goal conflict with both boundary spanning activities and resource orchestration. In the context of branch offices of one Indonesian SOB located in Indonesia, according to the result of this study, instead of having negative influence, intra-individual goal conflict positively and significantly influences boundary spanning activities but has no impact on resource orchestration.

In terms of the management of the banks, there are also three contributions of this study for strengthening the performance of SOBs: 1) equipping the capabilities of SOBs’ branch managers not only as middle managers (championing alternative, synthesizing information, facilitating adaptability, and implementing deliberate strategy) but also as boundary spanners (ambassadors, task coordinator, scout, guard, and service delivery) and resource orchestrator (structuring/search/selection, bundling, and leveraging/configuration/deployment); 2) developing non-hierarchical communication channels between SOBs’ branch managers with top management therefore information, feedbacks, and alternatives solutions obtained from their environment can be delivered to management as soon as possible to shorten responding time to environmental changes; and 3) delegating higher authority and more discretions to SOBs’ branch managers in performing resource orchestration so that the impacts of intra-individual goal conflict in decreasing branches’ performance can be minimized.

Limitations and future studies

This study has two limitations: (1) it uses one variable related to external environment, perceived environmental uncertainty, and one variable related to internal environment, intra-individual goal conflict; (2) the respondents are limited to branch managers as part of middle management. These limitations open up four opportunities for future studies: (1) adding more independent variables related to external environment (financial technology, digital technology, the COVID-19 pandemic, and other related variables) and internal environment (digital transformation, new ways of working, digital culture, and other related variables); (2) using other organizational variables (uncertainty, ambiguity, collaboration, customer engagement, goal commitment, goal prioritization, goal alignment, trust, perceived organization support, strategic thinking, entrepreneurial orientation, and other related variables) as intervening variables in the research model; (3) expanding the types of respondents (not only branch managers but also other members of all managerial levels in the organization that perform boundary spanning activities, such as change agents, public relation managers, lending relationships managers, purchasing manager for supply chain, customer service employees, senior managers, top management, and other related type of respondents ; and (4) replicating this study to other SOBs, private commercial banks, other financial service institutions, and also to all clusters of SOEs.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to they are related to activities conducted by branch managers of one of Indonesian state-owned bank, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

OECD (2021) Competitiveness in South-East Europe 2021: A Policy Outlook. Competitiveness and Private Sector Development. OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcbc2ea9-en

ADB Institute (2017) Efficient Management of State-Owned Enterprises: Challenges and Opportunities. Policy Brief, No. 2017-14 (December)

Ahmed E (2022) Predicting the mediating effect of resource orchestration on the relationship between leadership strategy and the resilience of Kenyan Listed Banks. Inter J Res Bus Soc Sci 11(6):56–73. https://doi.org/10.20525/ijrbs.v11i6.1904

Ahuja S Chan YE (2017) Resource Orchestration for IT-enabled Innovation. Kindai Mana Rev 5. https://www.kindai.ac.jp/files/rd/research-center/management-innovation/kindai-management-review/vol5_5.pdf Accessed 29 July 2023

Aldrich H, Herker D (1977) Boundary Spanning Roles and Organization Structure. Acad Manag Rev 2(2):217–230

Alfoldi EA, McGaughey SL, Clegg LJ (2017) Firm Bosses or Helpful Neighbours? The Ambiguity and Co-Construction of MNE Regional Management Mandates. J Manag Stud 54(8):1170–1205. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12287

Ancona DG, Caldwell DF (1989) Beyond Boundary Spanning: Managing External Dependence in Product Development Teams. Working Paper, Alfred P. Sloan School of Management. WP 2103-89. Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Mass. http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/46949

Ancona DG, Caldwell DF (1992) Bridging the Boundary: External Activity and Performance in Organizational Teams. Admin Sci Q 37(4):634–665. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393475

At-Twaijri MIA, Montanari JR (1987) The Impact of Context and Choice on the Boundary-spanning Process: An Empirical Extension. Hum Rel 40(12):783–798. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678704001201

Au KY, Fukuda J (2002) Boundary spanning behaviors of expatriates. J World Bus 37:285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-9516(02)00095-0

ADB (2022) Unlocking the Economic and Social Value of Indonesia’s State-Owned Enterprises. Asian Development Bank, December 2022. 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines

Badrinarayanan V, Ramachandran I, Madhavaram S (2018) Resource orchestration and dynamic managerial capabilities: focusing on sales managers as effective resource orchestrators. J Pers Sell Sales Manag 39(1):23–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853134.2018.1466308

Bai C, Quayson M, Sarkis J (2020) COVID-19 pandemic digitization lessons for sustainable development of micro-and small- enterprises. Sustain Prod Cons 27:1989–2001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.04.035

Baum CF, Caglayan M, Xu B (2021) The impact of uncertainty on financial institutions: A cross-country study. Inter J Fin Econ 26(3):3719–3739. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.1983

Bennett N, Lemoine GJ (2014) What a difference a word makes: Understanding threats to performance in a VUCA world. Bus Horiz 57(3):311–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2014.01.001

Berberoglu A (2018) Impact of organizational climate on organizational commitment and perceived organizational performance: empirical evidence from public hospitals. BMC Heal Serv Res 18:399. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3149-z

Bergami M, Moranding G, Bagozzi RP (2021) How and when Identification with a Boundary-Spanning Part of One’s Organization Influences Customer Satisfaction. Eur Manag Rev 18(2):93–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12435

Berseck, N (2018) Resource Orchestration as Source of Competitive Advantage of Cities – Empirical Studies of Business Improvement Districts in New York City and the City of Hamburg Technische Universitaet Berlin (Germany). ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2018. 27610476. https://depositonce.tu-berlin.de/items/76622da8-aa66-4de1-87a1-d92ccf740df3

Bettencourt LA, Brown SW, MacKenzie SB (2005) Customer-oriented boundary-spanning behaviors: Test of a social exchange model of antecedents. J Retail 81(2):141–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2005.03.004

Birkinshaw J, Ambos TC, Bouquet C (2017) Boundary Spanning Activities of Corporate HQ Executives Insights from a Longitudinal Study. J Manag Stud 54(4):422–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12260

Boelens B (2020) Boundary spanning in Dutch water management and sustainable energy projects. Master Thesis. Environmental and Infrastructure Planning, University of Groningen. https://frw.studenttheses.ub.rug.nl/id/eprint/3372. Accessed 28 July 2023

van den Brink M, Edelenbos J, van den Brink A, Verweij S, van Etteger R, Busscher T (2019) To draw or to cross the line? The landscape architect as boundary spanner in Dutch river management. Landsc Urban Plan 186:13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.02.018

Brion S, Chauvet V, Chollet B, Mothe C (2012) Project leaders as boundary spanners: Relational antecedents and performance outcomes. Inter J Proj Manag 30(6):708–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2012.01.001

Burbach ME, Eaton WM, Delozier JL (2023) Boundary spanning in the context of stakeholder engagement in collaborative water management. Soc Eco Pract Res 5:79–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-023-00138-w

Carbonara G, Caiazza R (2010) How to turn crisis into opportunity: Perception and reaction to high level of uncertainty in banking industry. Foresight 12(4):37–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/14636681011062988

Carnes CM, Hitt MA, Sirmon DG, Chirico F, Huh DW (2022) Leveraging Resources for Innovation: The Role of Synchronization. J Prod Innov Manag 39(2):160–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12606

Cattell RB, Burdsal Jr CA (1975) The Radial Parcel Double Factoring Design: A Solution to the Item-Vs-Parcel Controversy. Multivar Behav Res 10(2):165–179. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr1002_3

Chadwick C, Super JF, Kwon K (2015) Resource orchestration in practice: CEO emphasis on SHRM, commitment‐based HR systems, and firm performance. Strateg Manag J 36(3):360–376. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2217

Chen H, Tian Z (2022) Environmental uncertainty, resource orchestration and digital transformation: A fuzzy-set QCA approach. J Bus Res 139:184–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.09.048

Cheng MM, Luckett PF, Mahama H (2007) Effect of perceived conflict among multiple performance goals and goal difficulty on task performance. Account Finance 47(2):221–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-629X.2007.00215.x

Choi SB, Lee WR, Kang SW (2020) Entrepreneurial orientation, resource orchestration capability, environmental dynamics, and firm performance: A test of three-way interaction. Sustainability 12(13):5415. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135415

Cui Z, Han Y (2022) Resource orchestration in the ecosystem strategy for sustainability: A Chinese case study. Sustain Comput 36:100796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suscom.2022.100796

Dasgupta M (2015) Middle Level Managers and Strategy: Exploring the Influence of Different Roles on Organisational Performance. J Gen Manag 41(1):25–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/030630701504100103

Delaney JT, Huselid MA (1996) The impact of human resource management practices on perceptions of organizational performance. Acad Manag J 39(4):949–969. https://doi.org/10.2307/256718

Delozier JL, Burbach ME (2021) Boundary spanning: Its role in trust development between stakeholders in integrated water resource management. Curr Res Environ Sust 3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsust.2021.100027

Douglas JL (2008) The Role of a Banking System in Nation-Building. Maine Law Rev 60(2):511–531. https://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/mlr/vol60/iss2/14

Drion WRB (2021) Boundary spanning roles and related intellectual capital factors accomplishing innovations within and between public sector organizations: A boundary spanned explorative case study. Essay Master. Business Administration MSc., Behavioral Management and Social Sciences (BMS). University of Twente. http://essay.utwente.nl/86440/ Accessed 28 July 2023

Duncan RB (1972) Characteristics of Organizational Environments and Perceived Environmental Uncertainty. Admin Sci Q 17(3):313–327. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392145

Enders CK, Bandalos DL (2001) The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct Eqn Model 8(3):430–457. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5

Gianni SE, Saiful S, Aprila N (2020) Analisis Kinerja Keuangan Bank Milik Pemerintah Indonesia. J Fairness 10(2):135–148. https://doi.org/10.33369/fairness.v10i2.15260

Gorges J, Grund A (2017) Aiming at a moving target: Theoretical and methodological considerations in the study of intraindividual goal conflict between personal goals. Front Psycho 8(2011):1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02011

Graham JW (2003) Adding Missing-Data-Relevant Variables to FIML-Based Structural Equation Models. Struct Eqn Model 10(1):80–100. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1001_4

Gray JS, Ozer DJ, Rosenthal R (2017) Goal conflict and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. J Res Pers 66:27–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.12.003

Gupta AK, Govindarajan V, Malhotra A (1999) Feedback-Seeking Behavior within Multinational Corporations. Strateg Manag 20(3):205–222. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3094103

Haas A (2015) Crowding at the frontier: boundary spanners, gatekeepers, and knowledge brokers. J Knowl Manag 19(5):1029–1047. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-01-2015-0036

Hair Jr JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2019) Multivariate Data Analysis. Eighth Edition. Cengage Learning, EMEA, Cheriton House, North Way Andover, Hampshire, SP10 5BE United Kingdom

Hair Jr JF, Hult G, Thomas M, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2021) A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). Third Edition. SAGE Publications Inc., 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks, California 91320

Helfat CE, Finkelstein S, Mitchell W, Peteraf MA, Singh H, Teece DJ, Winter SG (2007) Dynamic capabilities and organizational process. Dynamic Capabilities: Understanding Strategic Change in Organizations. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

Hitt MA, Ireland RD, Sirmon DG, Trahms CA (2011) Strategic Entrepreneurship: Creating Value for Individuals, Organizations, and Society. Acad Manag Pers 25(2):57–75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23045065

Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ, Minkov M (2010) Cultures and Organizations, Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival. The McGraw-Hill Companies, New York

Hofstede G (2011) Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Read in Psych and Cult 2(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Huang CC, Wang YM, Wu TW, Wang PA (2013) An Empirical Analysis of The Antecedents and Performance Consequences of Using the Moodle Platform. Inter J Inform Educ Technol 3(2):217–221. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijiet

Hughes P, Hodgkinson IR, Elliott K, Hughes M (2018) Strategy, operations, and profitability: the role of resource orchestration. Int J Oper Prod Manag 38(4):1125–1143. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-10-2016-0634

IMF (2019) Reassessing the role of state-owned enterprises in Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. European Departmental Paper Series. No.19/11

IMF (2020) Government Support to State-Owned Enterprises: Options for Sub-Saharan Africa. June 15, 2020. Fiscal Affairs. Special Series on COVID-19

Indonesia Banking Statistics, Volume 20 Number 6. Financial Services Authority Republic of Indonesia, May 2022

Jahanshahi AA, Brem A (2020) Entrepreneurs in post-sanctions Iran: Innovation or imitation under conditions of perceived environmental uncertainty? Asia Pac J Manag 37:531–551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-018-9618-4

Jaser Z (2021) The Real Value of Middle Managers. Harv Bus Rev. Leadership Development. June 07, 2021. https://hbr.org/2021/06/the-real-value-of-middle-managers. Accessed 28 July 2023

Javidan M (1984) Research Note and Communication: The Impact of Environmental Uncertainty on Long-range Planning Practices of The US Savings and Loan Industry. Stratag Manag 5(4):381–392. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250050407

Johnson KL (2007) A case study of the expatriate boundary spanning role. Dissertation. Library and Archives Canada. Published Heritage Branch, 395 Wellington Street Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada, https://repository.library.carleton.ca/downloads/1r66j158c. Accessed 29 July 2023

Jun K (2018) Boundary Spanning and Leadership Perceptions in Creative Organizations: Evidence from four Orchestras. Theses and Dissertations–Management. College of Business and Economics, University of Kentucky, UKnowledge. https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2018.323https://uknowledge.uky.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=management_etds. Accessed 29 July 2023

Karimikia H, Bradshaw R, Singh H, Ojo A, Donnellan B, Guerin M (2022) An emergent taxonomy of boundary spanning in the smart city context – The case of smart Dublin. Technol Forecast Soc Change 185:122100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122100

Kehr HM (2003) Goal conflicts, attainment of new goals, and well-being among managers. J Occup Health Psychol 8(3):195–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.8.3.195

Keij L, van Kranenburg H (2022) How organizational leadership and boundary spanners drive the transformation process of a local news media organization. Journalism. https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849221105721

Kishton JM, Widaman KF (1994) Unidimensional versus domain representative parceling of questionnaire items: An empirical example. Educ Psychol Measure 54(3):757–765. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164494054003022

Kristoffersen E, Mikalef P, Blomsma F, Li J (2021) The effects of business analytics capability on circular economy implementation, resource orchestration capability, and firm performance. Inter J Prod Econ 239:108205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108205

Kwan HK, Lee C, Wright PL, Hui C (2013) Re-examining the Goal-Setting Questionnaire. In: Locke EA, Latham GP (eds) New developments in goal setting and task performance. Routledge, 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203082744

Lam LW (2012) Impact of Competitiveness on Salespeople’s Commitment and Performance. J Bus Res 65(9):1328–1334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.026

Lee C, Bobko P, Earley PC, Locke EA (1991) An Empirical Analysis of a Goal Setting Questionnaire. J Org Behav 12(6):467–482. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030120602

Leifer R, Huber GP (1977) Relations Among Perceived Environmental Uncertainty, Organization Structure, and Boundary-Spanning Behavior. Admin Sci Q 22(2):235–247. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391958

Leifer R, Delbecq A (1978) Organizational/Environmental Interchange: A Model of Boundary Spanning Activity. Acad Manag Rev 3(1):40–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/257575

Little TD, Rhemtulla M, Gibson K, Schoemann AM (2013) Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychol Methods 18(3):285–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033266

Locke EA, Latham GP (2002) Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. Am Psychol 57(9):705–717. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705

Locke EA, Latham GP (2006) New Directions in Goal-Setting Theory. Curr Direct Psychol Sci 15(5):265–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00449.x

Locke EA, Latham GP (2013) New developments in goal setting and task performance. Routledge, 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, 10.4324/9780203082744

Locke EA, Smith KG, Chah D, Schaffer A, Erez M (1994) The Effects of Intra-individual Goal Conflict on Performance. J Manag 20(1):67–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639402000104

Lysonski S, Woodside AG (1989) Boundary role spanning behavior, conflicts, and performance of industrial product managers. J Prod Innov Manag 6(3):169–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/0737-6782(89)90029-5

Matsunaga M (2008) Item Parceling in Structural Equation Modeling: A Primer. Commun Methods Measure 2(4):260–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312450802458935

Merindol V, Versailles DW (2018) Boundary Spanners in The Orchestration of Resources: Global-local Complementarities in Action. Eur Manag Rev 17(1):101–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12321

Miao C, Coombs JE, Qian S, Sirmon DG (2017) The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation: A meta-analysis of resource orchestration and cultural contingencies. J Bus Res 77:68–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.016

Miller CC, Washburn NT, Glick WH (2013) The myth of firm performance. Org Sci 24(3):948–964. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1120.0762

Milliken FJ (1987) Three Types of Perceived Uncertainty About the Environment: State, Effect, and Response Uncertainty. Acad Manag Rev 12(1):133–143. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1987.4306502

Monteiro F, Birkinshaw J (2016) The external knowledge sourcing process in multinational corporations. Strateg Manag J 38(2):342–362

Nachit H, Belhcen L (2020) Digital Transformation in Times of COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Morocco (July 7, 2020)

Natarajan S, Mahmood IP, Mitchell W (2019) Middle management involvement in resource allocation: The evolution of automated teller machines and bank branches in India. Strateg Manag J 40(7):1070–1096. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3017

OECD (2020) Digital Transformation in the Age of COVID-19: Building Resilience and Bridging Divides. Digital Economy Outlook 2020 Supplement, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/digital/digital-economy-outlook-covid.pdf Accessed 28 July 2023

Omotosho SI, Anyigba H (2019) Conceptualising corporate entrepreneurial strategy: A contingency and agency collaborative approach. J Strateg Manag 12(2):256–274. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSMA-05-2018-0046

Organ DW (1971) Linking pins between organizations and environment: Individuals do the interacting. Bus Horiz 14(6):73–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(71)90062-0

Panizza U (2023) State-owned commercial banks. J Econ Policy Ref 26(1):44–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2022.2076678

Peat DM, Perrmann J (2020) Exploring the Interaction Effects Between HR Systems and Resource Orchestration on Firm Performance. Acad Manag Proc 2020(1):17173. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2020.17173abstract

Peuscher D (2016) The Resource Orchestration Theory as contributor to Supply Chain Management: an assessment on its applicability. IBA Bachelor Thesis Conference, September 14th, 2016. University of Twente, The Faculty of Behavioural, Management and Social sciences, Enschede, The Netherlands, https://essay.utwente.nl/70993/1/Peuscher_BA_Behavioural%20Management%20and%20Social%20sciences.pdf. Accessed 29 July 2023

La Porta R, Lopez-De-Silanes F, Shleifer A (2002) Government Ownership of Banks. J Finance 57(1):265–301. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2697840

Republic of Indonesia, Article 2 Paragraph 1 of the Law Number 19 of 2003 on State-Owned Enterprises

Richard PJ, Devinney TM, Yip GS, Johnson G (2009) Measuring organizational performance: Towards methodological best practiXce. J Manag 35(3):718–804. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308330560

Santistevan D (2022) Boundary-spanning coordination: Insights into lateral collaboration and lateral alignment in multinational enterprises. J World Bus 57(3):101291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2021.101291

Santos JB, Brito LAL (2012) Toward a subjective measurement model for firm performance. Braz Admin Rev 9:95–117. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1807-76922012000500007

Sapienza P (2004) The effects of government ownership on bank lending. J Financial Econ 72(2):357–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2002.10.002

Satheesh SA, Verweij S, van Meerkerk I, Busscher T, Arts J (2023) The Impact of Boundary Spanning by Public Managers on Collaboration and Infrastructure Project Performance. Pubic Perform Manag Rev 46(2):418–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2022.2137212

Sawyerr OO (1993) Environmental uncertainty and environmental scanning activities of nigerian manufacturing executives: A comparative analysis. Strateg Manag J 14(4):287–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250140405

Schotter A, Beamish PW (2011) Performance effects of MNC headquarters–subsidiary conflict and the role of boundary spanners: The case of headquarter initiative rejection. J Inter Manag 17(3):243–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2011.05.006

Schotter APJ, Mudambi R, Doz YL, Gaur A (2017) Boundary Spanning in Global Organizations. J Manag Stud 54(4):403–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12256

Schwab RC, Ungson GR, Brown WB (1985) Redefining the Boundary Spanning-Environment Relationship. J Manag 11(1):75–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638501100107

Silva AA, Ferreira FCM (2017) Uncertainty, flexibility, and operational performance of companies: Modelling from the perspective of managers. Rev de Admin Mack 18(4):11–38. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-69712017/administracao.v18n4p11-38

Singh S, Darwish TK, Potočnik K (2016) Measuring Organizational Performance: A Case for Subjective Measures. Brit J Manag 27(1):214–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12126

Sirmon DG, Hitt MA, Ireland RD (2007) Managing firm resources in dynamic environments to create value: Looking inside the black box. Acad Manag Rev 32(1):273–292. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2007.23466005

Sirmon DG, Hitt MA, Ireland RD, Gilbert BA (2011) Resource orchestration to create competitive advantage: Breadth, depth, and life cycle effects. J Manag 37(5):1390–1412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310385695

Slocum JW, Cron WL, Brown SP (2002) The Effect of Goal Conflict on Performance. J Lead Org Stud 9(1):77–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190200900106

Special Report: Indonesian State-Owned Banks – Peer Review 2023. Thursday 09 March 2023 – 22.53 ET. https://www.fitchratings.com/research/banks/indonesian-state-owned-banks-peer-review-2023-09-03-2023. Accessed 24 June 2023

Staniok CD (2014) Goal Prioritization and Commitment in Public Organizations Exploring the Effects of Goal Conflict. The Rockwool Foundation Research Unit, Study Paper No.73. University Press of Southern Denmark

Stock RM (2006) Interorganizational teams as boundary spanners between supplier and customer companies. J Acad Mark Sci 34(4):588–599

Subramony M, Groth M, ‘Judy’ Hu X, Wu Y (2021) Four Decades of Frontline Service Employee Research: An Integrative Bibliometric Review. J Serv Res 24(2):230–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670521999721

Tang YC, Liou FM (2010) Does firm performance reveal its own causes? the role of Bayesian inference. Strateg Manag J 31(1):39–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.799

Temouri Y, Shen K, Pereira V, Xie X (2022) How do emerging market SMEs utilize resources in the face of environmental uncertainty? Bus Res Quar 25(3):212–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/2340944420929706

The State Ministry of State-Owned Enterprises of the Republic of Indonesia (2022) 2022 Annual Report. State Ministry of SOE of RI

Tuo-Chen L, Qiao L (2017) The Effect of Supply Chain Collaboration on Innovation Performance: Moderating Effects of Resource Orchestration. Paper presented at International Conference on Management Science and Engineering (ICMSE), Nomi, Japan, p 342–349. 2017 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMSE.2017.8574437

Wales WJ, Patel PC, Parida V, Kreiser PM (2013) Nonlinear Effects of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Small Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of Resource Orchestration Capabilities. Strateg Entrep J 7:93–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1153

Wei R, Geiger S, Vize R (2020) Bridging Islands: Boundary Resources in Solution Networks: An Abstract. In: Wu S, Pantoja F, Krey N (eds) Marketing Opportunities and Challenges in a Changing Global Marketplace. AMSAC 2019. Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science. Springer, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39165-2_258

Wilemon D (2014) Boundary-spanning as enacted in three organizational functions: new venture management, project management, and product management. In: Langan-Fox J, Cooper CL (eds) Boundary-spanning in organizations: Network, influence, and conflict. Routledge, New York, NY, p 230–250

Wu D (2022) Forging connections: The role of ‘boundary spanners’ in globalising clusters and shaping cluster evolution. Prog Hum Geogr 46(2):484–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325211038714

Xue R, Woo HR (2022) Influences of Boundary-Spanning Leadership on Job Performance: A Moderated Mediating Role of Job Crafting and Positive Psychological Capital. Inter J Envron Res Pubic Health 19(19):12725. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912725

Zhang C, Wu F, Henke Jr JW (2015) Leveraging boundary spanning capabilities to encourage supplier investment: A comparative study. Ind Mark Manag 49:84–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.04.012

Zhang Q, Li J (2021) Can employee’s boundary-spanning behavior exactly promote innovation performance? The roles of creative ideas generation and team task interdependence. Inter J Manag 42(6):1047–1063. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-06-2019-0302

Acknowledgements

This study is fully funded by the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP) Scholarship from the Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia (under contract number of 0008141/AK/D/2/lpdp2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception, methodology, and design. AA(1) contributed to the material preparation, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. AA(2), RR, and RK contributed to supervise the work. All authors contributed to read, review, revise, and approve the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research does not involve any human subjects and animal testing performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This research does not involve any human subjects and animal testing performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ariwibowo, A., Afiff, A., Rachmawati, R. et al. The impact of boundary spanning activities and research orchestration in improving performance of Indonesian state-owned bank branches. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 493 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02831-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02831-x