Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to show the necessary competence sets for Higher Education (HE) lecturers in the framework of the COVID and post-COVID. A COVID-situated competence survey was carried out among university lecturers. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (EFA, CFA) were applied to show the significant digital education competence factors. The representative online survey of 322 respondents shows that three big competence sets can be identified: Awareness, Professional, and Digital. Those having higher scores in Professional competencies foresee more digital programs and communications in the future, and not only the digital competencies but also the professional ones should be developed to meet the requirements of the digital education transformation process. The findings emphasize that the forced and drastic changes in the application of digital education to the intensification of COVID-19 should become sustainable and find its proper place and role in the future HE. The structured and closely managed use of the results was followed by a set of digital and professional competence development initiatives carried out within the framework of the Digital Education and Learning Support Centre, founded in 2020 at the University of Pécs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The world pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus shook the bases of the global and EU economies, causing serious economic consequences (European Commission, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic affected everyone in the whole world: individuals and the whole society as well. The virus changed everyone’s lives from one day to another. Individuals, cities, economies, countries, and continents experienced what it meant to be isolated from the outside world and be afraid of the unknown (Budhwar and Cumming, 2020; Caligiuri et al., 2020).

COVID-19 has had an unpredictable effect on the actors of society and the economy worldwide. The organization of work was identified as a significant research trend in the field of IT services during the global crisis, which is also valid in higher education (Shankar, 2020). This inspired us to form a research team and examine the influence of COVID-19 on the work of lecturers in higher education.

Because of the switchover of higher education to digital teaching in the Spring of the 2019/2020 academic year, we examined the digital and non-presence educational forms, the actual situation, and future ideas of distance work with the help of online questionnaire surveys. The first round of the survey for lecturers was organized at the University of Pécs (UP), which is the first founded (1367) university and one of the biggest higher education institutions in Hungary, with more than 20,000 students. The UP offers a broad range of training and degree programs even beyond the borders of the city. The UP represents classical university values (Hrubos, 2012), while the challenges of the present and the future are being adapted successfully as well.

The aim of our research is to supply data to the actors of higher education to help the leaders of universities motivate employees in the post-COVID-19 special situation, where universities had to reinvent themselves and adopt new strategies to support cohesion in educational communities to face the technical and methodological challenges of non-presence education. The changed circumstances, the switchover to digital education and working in a home office caused never-seen hardships and difficulties, which appear as problems to be solved both for employers and employees. The question is what the consequences of these effects will be for education and lecturers and how lecturers can be successful after the pandemic.

Basically, the above issues inspired our research group to focus on the following research question in connection with the post-COVID-19 pandemic world.

RQ: The question is if the competencies required of lecturers will change and meeting the challenges of digitalization will be central after the pandemia, or if other fundamental professional competencies can be detected as well.

To answer our research question, we did a focused literature research and conducted our own survey at the University of Pécs. Our literature research focused on the direct effects of the pandemic both in the changes in higher education and in the changes of competencies as well. The literature on competencies is widespread, so the present study could not undertake to exhibit its entire depth and width. Regarding our empirical research, we conducted a survey among the lecturers of UP after the home-office system and digital education were introduced. To start with, we analyzed the results of the validated competence surveys of the University of Pécs from the aspect of our research question. 322 out of 1426 lecturers responded to the survey, which means a response rate of 22.6%. Accordingly, the results allowed us to understand which further competencies beyond the digital ones were necessary while switching over to digital education in Hungary, and based on the results, we worded suggestions of possibilities of competence development to institution management and lecturers. Given the timeframe of the research, we think it important to show its afterlife and implemented initiatives, such as the Digital Education and Learning Support Centre founded by the University of Pécs, which also helps other HE actors to support the already launched development processes further.

Theoretical background

The changes in higher education caused by COVID-19 are presented in this chapter, together with the importance of competencies and different approaches to them.

Pandemic and its consequences on higher education

COVID-19 pandemic has an unpredictable effect on the actors of higher education worldwide. The measures to hinder the spreading of the pandemic, e.g., closing borders, traffic restrictions, decreasing capacities of public transportation, compulsory quarantine when entering and leaving a country, restrictions of public gatherings, voluntary separation from others, and keeping social distance, all mean serious challenges for higher education institutions in fulfilling their tasks (Brammer and Clark, 2020), that is for lecturers’ working as well.

Naturally, researchers around the world are currently analyzing the consequences of the pandemic from multiple aspects, including medical, social, economic, technology-innovational and also organizational, workplace, and educational aspects.

The research in the fields of organization and workplace focused on the change in the nature of working, leaving the familiar working environment, the challenges of home office, its costs and benefits with special emphasis on ergonomic aspects, workplace environment and the equipment supply of home office workstations (Autor and Reynolds, 2020; Boland et al., 2020; Davis et al., 2020; Fadinger and Schymik, 2020).

In the field of education, the collection of existing best practices and resources for handling the educational situation caused by the pandemic was started. The problems caused by the ‘new normal’ educational situation, e.g., the dropout rate and the unevenness in the quality of education, were analyzed. The influences of isolation on people working in higher education, their well-being, the efficiency of their work, and the possibilities of handling challenges caused by digital equipment were also examined (Dreesen et al., 2020; Isaacs, 2020; Musek, 2020).

Education-related research can also be categorized according to the levels of education under analysis (Singh and Chander, 2020) or according to practice-oriented areas in education (Awan et al., 2020; Hardie et al., 2020; Lal and Patel, 2020; Rassudov and Korunets, 2020), but it is evident that most of the researchers examine the mass shift of education to non-presence education along with digital education en masse (De, 2020). Opinions about the future are almost uniform that the systems of education will change (Gruenwald, 2020; Kallenberg, 2020), and educational methodologies will move in the direction of digital and online techniques (Ali and Kaur, 2020; Korkmaz and Toraman, 2020; Nikdel Teymori and Fardin, 2020).

As we have already highlighted, the conditions changed dramatically in which lecturers had to perform efficiently, especially due to the transition to non-attendance education and digital education. University leaders had to react quickly to the changing circumstances and provide prompt replies on how to continue working. In similar times, students, lecturers, researchers, and employees working in the administration of higher education institutions need support, tolerance, and empathy from one another (Braun et al., 2019). This could also be related to organizational trust (Bøe, 2018).

To explore the above situation, especially in higher education, the International Universities Association (IUA) published an online questionnaire, which was available between 25th March and 17th April 2020, to which 576 responses were received from 424 universities in 109 countries altogether (Marinoni et al., 2020). However, as only one response from each university was taken into account, the final sample size was 424. One of the most important conclusions of the research was that almost all higher education institutions (91%) had an existing communication infrastructure; in spite of this, according to the respondents, it was challenging to conduct unambiguous and effective communication processes with employees and students.

The research of Henley Business School, “UK Survey on COVID-19 and academic work”, used a questionnaire asking business and economics schools at universities in the United Kingdom. The research was conducted in three phases; more than 100 British higher education institutions were involved, and 13,048 responses were received. The questionnaire dealt with the situation of education, research, and examinations as well (Walker et al., 2020), and the respondents mainly agreed that online education makes presenting and explaining the curriculum and interacting with the students difficult.

Thus, the surveys above detected significant negative effects in the case of higher education organizations, lecturers, and researchers (see Table 1). Adapting to the post-COVID higher education situation is still a living challenge in the future. Successful organizations can gain a competitive advantage and success in the higher education market and competition for students.

The effects of pandemia: new type of working – new competencies?

A lot of changes in technology generated new situations, presenting multiple opportunities for the complex educational environment. Consequently, higher education institutions must be attentive to these changes to ensure that students have the skills necessary for the work environment (Farias-Gaytan et al., 2023).

Constant fluctuation is the most important feature of the labor market nowadays. With the help of life-long learning and continuously acquiring new skills, we can accommodate new conditions more easily. Well trained labor force is a type of capital essential in creating a competitive, sustainable, and innovative economy, and this is especially true regarding lecturers working in higher education. HEIs must adapt to ongoing trends and developments in their macro and micro environments, and at the same time, they need to capitalize on any available opportunities, including resources and competencies, to deliver high-quality, student-centered education (Camilleri, 2020).

Numerous studies have examined the relationship between skills and employability (Baird and Parayitam, 2019; Clarke, 2016; Hossain et al., 2020; Kuráth and Sipos, 2020; Teng et al., 2019). Their results can be applied in higher education regarding lecturers’ work as well since it is evident that the educational competencies necessary for successful knowledge transfer changed as an effect of COVID-19. Online learning has become the new mainstream learning norm in universities during the post-epidemic era (Tang and Mo, 2022). In the midst of the paradigm shift, characterized by the growth of online learning in higher education and the move from traditional to online teaching, lecturers would need a wide range of competencies (Chaharbashloo et al., 2023). The competencies and educational methodology of digital education became central in distance learning, and so did the remote teaching competencies (skills and ability to use diverse teaching methods) models (Yunusa et al., 2020). Digital competence is crucial in contemporary social digitalization and should be promoted at all educational levels (Sá and Serpa, 2020). The literature offers several definitions of the capacity to mobilize digital competencies; these involve the ability to use digital technology consciously and critically. Digital competence incorporates the ability to use digital technology both as a consumer and as a content creator (European Commission, 2018; European Union, 2006; Ferrari, 2012; Klassen, 2019; Pötzsch, 2019; Sá and Serpa, 2020).

The lecturers’ professional competencies are important and related to the students’ academic performance, achievement or the performance of a job (Azis et al., 2020; Prasetio et al., 2017).

However, not all individuals who are considered experts can perform well in a lecturer’s job. Professional competencies are rather complex abilities that an individual should possess to perform certain professional activities (Prasetio et al., 2017). Professional competencies can be characterized not only as the ability to give lectures but also as the willingness and capacity to use their potential functionally and to bear responsibility for one’s decisions during the educational process (Žeravíková et al., 2015).

Abduh (2018) found that professional lecturers with professional competence can work and deliver teaching materials effectively, and this competence can be one of the indicators of being a professional educator within a higher education context.

Lecturers are expected to take the roles of a coach, a mentor, and a facilitator at the same time in the online teaching environment (Baran et al., 2013; Sibiya et al., 2020). However, research has largely focused on the technical/hard skills required by the labor market, whereas only limited attention has been devoted to the investigation of soft competencies (Balcar, 2016; Succi and Wieandt, 2019).

There are different definitions of ‘soft skills’, notably as life skills, transversal, cognitive, interpersonal, intellectual, practical skills, and generic competencies, as well as key competencies for a successful life, well-functioning society, and lifelong learning (Haselberger et al., 2012; Heckman and Kautz, 2012; OECD, 2012; Succi and Wieandt, 2019; WHO, 1994).

Succi and Wieandt (2019) adopted the Haselberger list of soft skills defined and described in detail by the ModEs European Project (Haselberger et al., 2012), creating a list of 20 soft skills (categories: personal, social, and methodological).

These skills help people to deal effectively with the challenges of their professional, everyday life, and these are commonly used to refer to people’s emotional side (Le Deist and Winterton, 2005; Succi and Wieandt, 2019).

The starting point of our research was to find out whether the competencies required from lecturers would change after the switchover to digital education as an effect of COVID-19. To accomplish this, we conducted primary research to see if digital became central or if other basic professional competencies could be detected as well.

How have employers incorporated their COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 experiences into their activities? What new expectations have been formulated regarding organizations, workplaces, and employees’ competencies?

Poór et al. (2020a, 2020b), Dajnoki, Kun, et al. (2023), and Dajnoki, Poór, et al. (2023) pointed out some competencies that became the most important in the first and second waves of the pandemic in Hungary: expertize, knowledge, professional experience, digital competencies, IT knowledge, online technologies, problem-solving skills, planning and organization, change and crisis management, independence, flexibility, quick adaptation, training, self-development, learning, planning/organizing, training, communication, assertiveness, conflict management, leadership soft skills, cooperation, teamwork, resilience, stress tolerance, load capacity, empathy, EQ, social skills.

A few researchers have given some best practices in connection with the post-pandemic workplace generally (Chan et al., 2023), organizational resilience (Zhao and Li, 2023) or the adaptation of the role in governance (Almaqtari et al., 2023), while others analyzed the post-pandemic competencies in the digital era (Haris et al., 2023), especially on the focus of artificial intelligence in education (closing to our topic) (İçen, 2022).

What new directions and answers have been formulated specifically for higher education in the post-COVID period? Most of the new possible trends in higher education are based on the high level of Information Communication Technology (ICT) (Kara, 2021) and the methodology of digitalized education and learning, such as e-learning and blended learning (Fauzi, 2022). The criteria for effective teaching in post-COVID are linked to digital knowledge and competencies as well (Devlin and Samarawickrema, 2022).

Methodology

This chapter discusses the details of the survey executed at the University of Pécs. Besides the competence list that was narrowed down based on many years of experience, the execution and methodologies contributing to the examination of research questions are also detailed.

The assessment of competence at the UP

The starting point was the Kabai model (Kabai et al., 2011) and the CHEERS research investigated by García-Aracil and Van der Velden (2007). The pilot research in 2010 established the competence vocabulary using an EFA, which made it possible to identify 16 variables about competencies.

The UP carried out a methodology control (twice) concerning the scope of competence: using paired sample T-test and factor analysis, examining the internal interfaces regarding the data from the previous years, and considering international professional research and publications on the topic. Based on this, the UP decided that a structural correction was needed. As a result of this change, the UP asked questions from each competence group established within the CHEERS research investigated by García-Aracil and Van der Velden (2007). By doing this, the UP complied with the guidelines found in the expectations of the European Union. The final list and details can be seen in the study of Kuráth and Sipos (2020).

Technical execution

Questionnaires were distributed via the online system of EvaSys, and responses were voluntary. The standard online questionnaire of the quantitative survey reached the respondents in April and May 2020. The lecturers of the University of Pécs with Hungarian citizenship embodied the population, 1426 in total. The response rate of 22.6% (322 respondents) is considered high, especially knowing that lecturers at the Faculty of Medicine were under strain due to medical work related to COVID-19, and the duties of the switchover to digital education burdened the whole staff. Examining the gender of respondents, the distribution of female respondents was greater than in the population, and distribution based on age was relatively balanced, although the population under 25 and above 66 of age was small, and due to this, there is a distortion favouring younger respondents. More than 60% of respondent lecturers had been employed by the university for at least ten years.

The questionnaire for lecturers inquires about digital education, home office, organizational communication and culture, and future plans (Sipos et al., 2020); due to length limitations, this study focuses on digital education and competencies.

Considerations of the analysis and methodology

The data was processed using mathematical and statistical methodologies and the SPSS analytical software, providing maximal data security and anonymity that can be expected in the case of online questionnaires. Comparing the results was an important aspect; for this reason, the preparation of the questionnaires was based on the approach and results of research conducted at the University of Pécs in previous years, to which the competencies related to digital education were added. During the survey, only a shorter list could be built into the questionnaire; therefore, the competence groups of awareness and professional skills were selected. Respondents had to answer the questions on a Likert scale of 1 to 5. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the inquired competence list. It can be seen that ICT technology was held the most important, while nonverbal communication was the least important regarding the efficient operation of digital education. Based on the skewness and kurtosis values, all of them can be considered normal distributions (Pituch and Stevens, 2015).

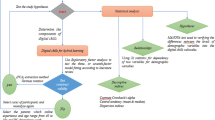

The first step after determining the basic data was to run an exploratory factor analysis (EFA), making it possible to validate whether the existence of previously assumed groups can be identified without forced distribution. The essence of the method is to ensure variance maximization in the data, thus regrouping the original data and creating new factors. The prerequisite of the EFA is that the items correlate with one another, and the analysis can be run with a high confidence level, for this, the Cronbach Alpha value has to be identified so that only values greater than 0.7 are acceptable. During the EFA, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity values have to be examined. In case the value of the former is >0.9, the analysis is very good; it is good if the value is between 0.8 and 0.9 and acceptable if it is between 0.7 and 0.8. In the case of the latter, the p-value is required to be less than 0.05. It is highly recommended to run the Principal Component Analysis with varimax rotation. In general, communality values less than 0.5 should not be taken into consideration when loading into each factor; those less than 0.4 are not to be calculated at all. The identified factors are independent of each other; varimax rotation ensures the best overall fit (Pituch and Stevens, 2015).

Although the established factors are independent according to EFA methodology, the application of a forced method is also recommended. The items belonging to factors can be assigned to latent variables using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). This method does not make factors independent, thus, multicollinearity can occur; however, the analysis effects measured by factors will be more valid on professional grounds. In the case of the CFA, the composite reliability (CR) and the Average Variance Extracted (EVA) analyses contribute to validating the existence of the model. In the case of CR, a value greater than 0.7 means appropriate reliability, but it cannot be less than 0.5. In the case of EVA, the required value is at least 0.5. We use root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) with acceptance criteria of up to 0.10; comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and Coefficient of determination (CD) with acceptance criteria of greater than 0.8; standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) with acceptance criteria of lower than 0.1 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Geldhof et al., 2014; Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Finally, the one-way analysis of variance (One-way ANOVA) shows the extent to which the identified factors contribute to the long-term sustainability of the strong digitalization forced by COVID-19. The difference is significant if Levene p > 0.05 or Welch p ≤ 0.05 and ANOVA p ≤ 0.05.

Findings

The chapter shows the execution of the validity analysis of the three-component group based on our assumption, applying EFA and CFA methods. Afterwards, the main hypothesis of the research is tested using One-Way ANOVA.

Grouping of competencies using factor analysis

Based on the reliability analysis, as a prerequisite of EFA, the value of Cronbach Alpha is 0.839, which means that the analysis can be executed. The value of the KMO test is 0.828 with an appropriate level of significance (Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity χ2: 1.116 034 df = 66 p = 0.000). The maximal number of factors can be four due to the number of items; the eigenvalues and Scree Plot validate the existence of three factors. The related explained variance is 62.2%, which can be regarded as sufficient (Table 3).

The three factors and the description of the competencies belonging to each of them are detailed below; it has to be highlighted that not a model has been identified or repeated but a professional categorization has been carried out to highlight the relevant competence sets for the lecturers:

Factor 1 consists of three elements: Information and communication technology competencies; Digital curriculum development competencies; Online methodological competencies. All of them are competencies specifically needed for digital education, thus, the factor’s name is digital.

Factor 2 consists of five elements. There are multiple considerations since, on the one hand, there is a strong link between Emotional intelligence, Nonverbal communication, and Conflict management skills pointing towards the direction of emotions; on the other hand, Creativity, New vision, and Teamwork elements suggest relating to others and new viewpoints. So, it was named Awareness.

Factor 3 contains four elements. Flexibility and Good time management are regarded as soft and supportive; however, the Ability to analyze and synthesize and Organization skills represent the professional side of education, thus, the factor’s name became Professional.

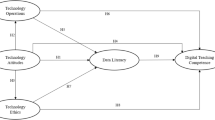

After running the EFA, the next step was the CFA according to the methodology description. Table 4 shows the values related to the three factors, along with the indicators representing the reliability of the model. Figure 1 displays the connections, and it also contains the standardized coefficients. Based on this, it can be stated that each factor bears high AVE and CR values, given an appropriate Cronbach Alpha value, so the existence of all of the factors is justified. The goodness of fit values of the model were within the originally set criteria in the case of all variables.

Figure 1 illustrates that in two cases (D2-D3 and A1-A4), relationships between random errors had to be allowed. The recommended change of Modification Indices is professionally acceptable since the relationships between Digital curriculum development competencies, Online methodological competencies, Creativity, New vision, and Conflict management skills are probable. It should be highlighted that the model previously met all the requirements of the goodness of fit; however, for an even better fit, this minimal correction in the model was acceptable.

On the whole, it can be stated that the model exists, based on professional considerations, the item values of the three factors are related in a statistically demonstrable way.

The analysis of the relationship between educational competencies and the future of digital education using One-Way ANOVA

The three factors established as a result of the CFA appropriately represent lecturers’ competence requirements. The examination of the question in the focus of the study is executed by using a one-way analysis of variance. The question is visualized in Fig. 2.

The questionnaire offers three response options related to the extent of future digital education; the respondent numbers and their distribution in percentage can be seen next to each option.

-

There will be a lot of new online programs, 78 cap – 25.2%

-

Education will be altered to have a little more online programs, 197 cap – 63.5%

-

Everything will be the same as before the pandemic, 35 cap – 11.3%.

In relation to these, we examined what specific features can be detected along with the three identified factors (Table 5), namely where significant relationships exist between them. This way, we can find out which elements are necessary for the success of future digital education.

The result of the One-Way ANOVA shows that in connection with the future shift towards digital education, higher average values can be identified in case of all of the competencies, yet only the Professional factor shows a significant difference based on Levene, Welch, and ANOVA p values.

Discussion and survey afterlife implemented initiatives

To sum up, the COVID-19-related situation resulted in new challenges (Marinoni et al., 2020; Walker et al., 2020) in the future development of digital educational programs and the fields of hard (Kara, 2021) and soft educational technology (Fauzi, 2022). It was expected that lecturers had to meet the challenges of digitalization in higher education (Devlin and Samarawickrema, 2022), that is to say, online competencies would have outstanding significance.

However, the actual challenge is to “develop fluency with teaching and learning with technology, not just with technology, itself” (Jacobsen et al., 2002, p. 44.). Our survey proved as well that beyond technical competencies, further competencies are also necessary. So, the results of the survey confirm that digital competencies are necessary but not sufficient conditions for the long-term success of digital education, and high-level professional competencies are also essential.

We agree that in the online teaching environment, lecturers are expected to take the roles of coach, mentor, and facilitator (Baran et al., 2013; Sibiya et al., 2020), and to meet these requirements, high-level personal and professional competencies are also necessary.

We agree with the authors that software skills may be essential for much of the work of the 21st century, but candidates also need soft skills to be reliable employees. Therefore, widely available technical training is not enough to make people truly ready to work; they also need to develop soft skills, which are usually learned in the workplace (Abere and Constantinides, 2021).

So besides answering the question ‘How?’ (digitally), answering the question ‘What?’ (high-level professional competence and proper attitude) is still a cardinal success factor in the future of higher education.

It is to be highlighted that the presented research fits into a series of initiatives that started before the pandemic but accelerated due to its outbreak. Even before, a workgroup was created at the University of Pécs for the sake of facilitating the spread of digital learning and teaching practice and preparing for a certain transformation. The so-called Digital Education and Learning Support Workgroup (created in December 2020) dedicated its work to responding to the ever-increasing use of online spaces, which are inextricably intertwined with the lives of HE stakeholders. The students and academics started trying out the international trends, and the need for a structured and global information flow and knowledge sharing has rapidly risen. Distance and hybrid education require the proper support not only from an administrative but also from pedagogical, technical, and methodological perspectives (such as MS Teams lectures, Kahoot! tests, course materials in Moodle, HP5 integration, etc.). The weighted use of the toolbox of blended learning pointed to the need for a digital education and learning support system, which can be considered a basic requirement in a 21st-century European higher education institution. In 2020, the Workgroup transformed into a Centre (Digital Education and Learning Support Centre – DOT from the acronym of the Hungarian name: Digitális Oktatás- és Tanulástámogató Központ), emphasizing its role and importance.

The present research gave a stimulus to this transformation of the DOT, which surveyed the student side in 2021 (Dombi et al., 2022; Dombi et al., 2021), where 2999 responded out of the 18,337 base population (16.4% response ratio). The biggest problem they faced during the pandemic was the lack of digital competencies of the lecturers. Even if the students liked the solution of digital education and distance learning, their 3.21 average score on a 1–5 Likert scale, where 5 meant physical learning and 1 meant digital learning, indicated the need for physical learning dominance with digitally supporting elements.

As a consequence, the DOT intensified the workshops organized for the teachers (4–6/semester with an average participant number of 33 professors) with topics of Artificial Intelligence, gamification, online evaluation software, Moodle tricks and practices, M365 integration and SharePoint solutions, etc.). Parallel to these, the e-learning and blended learning support has been extended through the ‘Transformation of traditional courses according to the blended learning methodology’ renders launched by the DOT. Until December of 2023, 104 courses with more than 120 professors won financial and methodological support, in which, in one semester, the participants learned through three modules and extensive consultation sessions how to adapt their course to the new expectations. This means that 15–20 courses are supported in one semester. Considering the professor number (ca. 1500), this has quite a big impact.

Even a White Book on how to support digital education and learning was published in 2022 to further support the professors and to explicitly state the strategic role of digital education within the institutional development strategy of the University of Pécs (Dombi et al., 2022).

In 2023, another survey targeted the students to measure the impact of the initiatives taken. The preliminary results are only ready in December 2023; they show a significant shift toward digital practices, but more has to be done. The next step will be the e-learning support of students in relevant education-related competencies such as time management, digital sources, digital learning, learning environment, available software and solutions, ethical issues, etc. A pilot phase will be started in the Spring of 2024, and every student starting their studies in September 2024 has to get through this segmented and individual-needs-based course.

Beyond this fundamental and university-wide action, other smaller changes have also been implemented, of which it is worth mentioning the Hackathon program (Tóth-Pajor et al., 2023) organized for a mix of students, mentors, professors, and industry partners. Through the digital entrepreneurship education initiative, all the participants can be part of a development framework, where the third mission (Compagnucci and Spigarelli, 2020) is also supported to a significant extent. Furthermore, some parts of post-graduate programs are organized in an e-learning framework, which will be intensified in the future.

Conclusion

Due to the effects of the COVID-19 crisis on educational institutions, schools had to close and switch to online education. The educators’ incorporation and utilization of technology as part of Internet-based instruction was a challenge and pressing necessity. TPACK is an essential framework for comprehending how teachers employ technology in teaching (Elmaadaway and Abouelenein, 2022). At the heart of the TPACK framework is the complex interplay of three primary forms of knowledge: Content (CK), Pedagogy (PK), and Technology (TK). The TPACK approach goes beyond seeing these three knowledge bases in isolation. The TPACK framework goes further by emphasizing the kinds of knowledge that lie at the intersections between three primary forms: Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK), Technological Content Knowledge (TCK), Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK), and Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) (Mishra and Koehler, 2022).

The development of teachers’ digital teaching competence is crucial for effectively infusing technology into teaching in the post-COVID era. With the growing importance of data in education, it is imperative to explore the influencing factors of digital teaching competence and the potential role of data literacy in facilitating digital teaching competence, namely, technology attitudes and technology operations (Chu et al., 2023). The need for digital competencies is also reflected in the expectations of the organization’s employees, as digital forms are also of enormous importance in organizational communication (Borgulya et al., 2022).

Work as we know it has changed forever by the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic. In the contemporary digital society, schools and other educational institutions needed and are in constant need to reinvent themselves. Aspects such as training, internet access infrastructure, hardware and software, digital literacy, and students’ and academics’ teaching and learning strategies are essential in this shift (Sá and Serpa, 2020).

Universities are left with the responsibility to tailor themselves in such a way that whether in an informal or formal environment, teaching and learning should suit those who facilitate teaching, as well as students who are meant to benefit from their respective programs which they are registered for (Sibiya et al., 2020).

Because of introducing non-presence education and the switchover to digital education, the community of lecturers working in higher education had to adopt another knowledge transfer technique and methodology, which they could not entirely accommodate yet. However, today’s tendencies started to reveal to those working in higher education that besides the acquisition of all the competencies of digital education as part of ‘lifelong learning’ (user skills of hardware and software elements, applying new digital education methodologies etc.), the ‘how’ of knowledge transfer does not eliminate the justification of professional knowledge and the competencies belonging to them, that is the importance of ‘what’. These are the ‘good news’ our empiric survey was able to prove for the community of university lecturers.

Research limitations and further research

Although the study has remarkable strengths, some limitations exist. Given the appropriate number of respondents, our research focuses on the lecturers of one Hungarian higher education institution (although one of the biggest), so the results can be considered as guidance to other higher education institutions, and at the same time, they can be used by not only domestic but also international ones. We agree that although studies from different regions can provide important local insight (Isaacs, 2020; Tumwesige, 2020), e.g., managing pandemics in organizations, they can help us to find global solutions as well.

During the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic, the workload of lecturers was extremely heavy because of the transition, so we focused on a limited group of competencies. The questions were responded after the hardship of the first months.

Future studies could apply multiple research methods, such as interviews or other qualitative techniques and analyses because it is also worth understanding the student side. Li et al. (2023) found that teachers should choose motivating styles appropriately based on students’ online learning characteristics and content, and students should develop online ability to improve their engagement and achieve good online learning effectiveness. A further step can be identified within the context of UP students in 2021 (Dombi et al., 2022; Dombi et al., 2021), but additional research should be carried out where a 360-degree assessment can be beneficial.

The complete research program was conducted in Hungary, where the online questionnaire survey of lecturers and employees of UP was put in focus. By involving the international environment in the research, it would be possible to see if national differences can be identified.

Besides institutional level research, it would be an interesting assumption whether the results would be specific to different fields of science, in other words, whether the results would differ in the case of e.g., life sciences with practical teaching methods and social sciences.

Implications

The three sets of competencies utilized in our research can be applied by other higher education institutions to survey the attitude of lecturers and the main focuses of development. Our starting point was that leaders should begin to take steps to consider what the workplace will look like when the pandemic finishes, even if there is no going back to the pre-pandemic situation. Organizations and individuals have had no other choice but to discover new ways of working (Kane et al., 2021). If we look ahead, lecturers’ competencies in higher education will also need to be developed. Soft skills are developed through formal and informal activities. The 70:20:10 learning model is widespread, in which it is considered that 70 percent is learned informally (on the job, experience-based, and through stretch projects and international mobility); 20 percent occurs thanks to coaching and mentoring, developing through others’ feedback and performance appraisal processes; 10 percent through formal learning interventions and structured courses (Kajewski and Madsen, 2012; Succi and Wieandt, 2019).

The professional development aims to enable teachers and educational leaders to perform successfully in professional roles. The key players must regularly participate in relevant professional development programs to gain or improve their knowledge, skills, and abilities (Nguyen, 2019). Based on the above statements, creating opportunities for both formal and informal development is recommended on the institutional level. Therefore, universities should provide remote teaching workshops to assist lecturers before moving to the online teaching environment (Sibiya et al., 2020).

Online learning has merits and is highly welcomed by learners and faculties as well. However, whether the learning quality of online learning improves or not, it should be evaluated adequately. As such, new technologies will be invented, and lecturers should apply them if their introduction improves the classes (Kurihara, 2020). The question of quality should be highlighted, and lecturers having proper competencies are essential to provide high-quality education.

When calling for tenders, education politics should be aware of the fact that it is not enough to involve the acquisition of new skills (digital), but the development of the already existing professional and soft competencies should be ensured as well. Without this awareness, the digital competencies cannot fit into a proper framework; moreover, the efforts to develop them could not be utilized properly.

Data availability

As supplementary information file, it is freely accessible on the journal website. Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ULKGUV.

References

Abduh A (2018) Lecturers’ perceptions on factors influencing the implementation of bilingual instruction in Indonesian universities. J Appl Res High Educ 10(3):206–216

Abere, R, & Constantinides, P (2021). The Future of Digital Work Depends On More Than Tech Skills. MIT Sloan management review. Retrieved 25 February 2021, from https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/the-future-of-digital-work-depends-on-more-than-tech-skills/

Ali W, Kaur M (2020) Educational challenges amidst covid-19 pandemic. Asia Pac Inst Adv Res (APJCECT) 6(2):40–57. https://apiar.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/4_APJCECT_V6_I2_2020_pp.40-57.pdf

Almaqtari, FA, Farhan, NHS, Al-Hattami, HM, & Elsheikh, T (2023). The moderating role of information technology governance in the relationship between board characteristics and continuity management during the Covid-19 pandemic in an emerging economy. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01552-x

Autor, DH, & Reynolds, E (2020). The nature of work after the COVID crisis: Too few low-wage jobs. The Hamilton Project, Brookings. Retrieved 18 February 2021, from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/AutorReynolds_LO_FINAL.pdf

Awan S, Awan GM, Omar B (2020) COVID-19: medical education transformation. Cardiofel Newslet 3(7):33–36. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.16837.47848

Azis M, Hasiara LO, Abduh A (2020) Relationship between lecturers’ competences and student academic achievement in indonesian public universities. Talent Dev Excell 12(1):1825–1832

Baird AM, Parayitam S (2019) Employers’ ratings of importance of skills and competencies college graduates need to get hired. Educ + Train 61(5):622–634. https://doi.org/10.1108/et-12-2018-0250

Balcar J (2016) Is it better to invest in hard or soft skills? Econ Labour Relat Rev 27(4):453–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304616674613

Baran E, Correia A-P, Thompson A (2013) Tracing successful online teaching in higher education: Voices of exemplary online teachers. Teach Coll Rec 115(3):1–41

Bøe T (2018) E-learning technology and higher education: the impact of organizational trust. Tert Educ Manag 24(4):362–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2018.1465991

Boland, B, De Smet, A, Palter, R, & Sanghvi, A (2020). Reimagining the office and work life after COVID-19. Retrieved 10 February 2021, from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/reimagining-the-office-and-work-life-after-covid-19#

Borgulya I, Balogh G, Jarjabka Á (2022) Communication management in industrial clusters: an attempt to capture its contribution to the cluster’s success. J East Eur Manag Stud 27(2):179–209. https://doi.org/10.5771/0949-6181-2022-2-179

Brammer S, Clark T (2020) COVID‐19 and management education: reflections on challenges, opportunities, and potential futures. Br J Manag 31(3):453–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12425

Braun E, Spexard A, Nowakowski A, Hannover B (2019) Self-assessment of diversity competence as part of regular teaching evaluations in higher education: raising awareness for diversity issues. Tert Educ Manag 26(2):171–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-019-09047-8

Budhwar P, Cumming D (2020) New directions in management research and communication: lessons from the COVID‐19 pandemic. Br J Manag 31(3):441–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12426

Caligiuri P, De Cieri H, Minbaeva D, Verbeke A, Zimmermann A (2020) International HRM insights for navigating the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for future research and practice. J Int Bus Stud 51(5):697–713. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00335-9

Camilleri MA (2020) Using the balanced scorecard as a performance management tool in higher education. Manag Educ 35(1):10–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020620921412

Chaharbashloo, H, Talebzadeh, H, Hosseini Largani, M, & Amirian, S (2023). A systematic review of online teaching competencies in higher education context: a multilevel model for professional development. Res Pract Technol Enhanc Learn 19. https://doi.org/10.58459/rptel.2024.19014

Chan XW, Shang S, Brough P, Wilkinson A, Lu CQ (2023) Work, life and COVID‐19: a rapid review and practical recommendations for the post‐pandemic workplace. Asia Pac J Hum Resour 61(2):257–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12355

Chu, J, Lin, R, Qin, Z, Chen, R, Lou, L, & Yang, J (2023). Exploring factors influencing pre-service teacher’s digital teaching competence and the mediating effects of doata literacy: empirical evidence from China. Human Soc Sci Commun 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02016-y

Clarke M (2016) Addressing the soft skills crisis. Strateg HR Rev 15(3):137–139. https://doi.org/10.1108/shr-03-2016-0026

Compagnucci, L, & Spigarelli, F (2020). The Third Mission of the university: A systematic literature review on potentials and constraints. Technol Forecast Soc Change, 161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120284

Dajnoki K, Kun AI, Poór J, Jarjabka Á, Kálmán BG, Kőmüves ZS, Pató Szűcs B, Szabó K, Szabó S, Szeiner Z, Tóth A, Csehné Papp I (2023) Characteristics of crisis management measures in the hr area during the pandemic in hungary – literature review and methodology. Acta Polytech Hung 20(7):173–192. https://doi.org/10.12700/aph.20.7.2023.7.10

Dajnoki K, Poór J, Jarjabka Á, Kálmán BG, Kőműves ZS, Pató Gáborné Szűcs B, Szabó K, Szabó S, Szeiner Z, Tóth A, Csehné Papp I, Kun AI (2023) Characteristics of crisis management measures in the hr area during the pandemic in hungary - results of a countrywide survey of organizations. Acta Polytech Hung 20(7):193–210. https://doi.org/10.12700/APH.20.7.2023.7.11

Davis KG, Kotowski SE, Daniel D, Gerding T, Naylor J, Syck M (2020) The home office: ergonomic lessons from the “new normal. Ergon Des: Q Hum Factors Appl 28(4):4–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1064804620937907

De, S (2020). Impacts of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Global Education. In B Syed (Ed.), COVID-19 Pandemic update 2020 (pp. 84-94). https://doi.org/10.26524/royal.37.6

Devlin M, Samarawickrema G (2022) A commentary on the criteria of effective teaching in post-COVID higher education. High Educ Res Dev 41(1):21–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.2002828

Dombi, J, Egervári, D, Fodorné Tóth, K, Simon, K, Sipos, N, & Vörös, Z (2022). Fehér Könyv a digitális oktatás- és tanulástámogatásról. Pécsi Tudományegyetem. https://m2.mtmt.hu/api/publication/33074848

Dombi J, Sipos N, Vörös Z (2022) A megváltozott tanulási környezet digitális eszközei – hallgatói tapasztalatok a Pécsi Tudományegyetemen. Új Pedagógiai Szle 72(9-10):47–67. https://m2.mtmt.hu/api/publication/33559565

Dombi J, Sipos N, Vörös Z, Egervári D, Simon K, Fodorné Tóth K, Ambrus AJ (2021) Online vagy sem - mitől függhet a jövő? Hallgatói tapasztalatok és jövőbeni preferenciák összefüggései a Pécsi Tudományegyetemen. Iskolakultúra 31(11-12):130–152. https://doi.org/10.14232/ISKKULT.2021.11-12.130

Dreesen, T, Akseer, S, Brossard, M, Dewan, P, Giraldo, J-P, Kamei, A, Mizunoya, S, & Correa, JSO (2020). Promising practices for equitable remote learning. Emerging lessons from COVID-19 education responses in 127 countries. https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/IRB%202020-10%20CL.pdf

Elmaadaway MAN, Abouelenein YAM (2022) In-service teachers’ TPACK development through an adaptive e-learning environment (ALE). Educ Inf Technol 28(7):8273–8298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11477-8

European Commission (2018) Human Capital Digital Inclusion and Skills: Digital Economy and Society Index Report 2018 Human Capital. European Commission, Brussels

European Commission. (2020). Spring 2020 Economic Forecast: A deep and uneven recession, an uncertain recovery. European Commission Press Release. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_799

European Union (2006) Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 on key competences for lifelong learning. Off J Eur Union 394:10–18. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32006H0962

Fadinger H, Schymik J (2020) The effects of working from home on Covid-19 infections and production a macroeconomic analysis for Germany. Covid Econ 9(24):107–139

Farias-Gaytan, S, Aguaded, I, & Ramirez-Montoya, M-S (2023). Digital transformation and digital literacy in the context of complexity within higher education institutions: a systematic literature review. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01875-9

Fauzi, MA (2022). E-learning in higher education institutions during COVID-19 pandemic: current and future trends through bibliometric analysis. Heliyon, 8(5). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09433

Ferrari, A (2012). Digital competence in practice: An analysis of frameworks (P. O. o. t. E. Union, Ed.). https://doi.org/10.2791/82116

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

García-Aracil A, Van der Velden R (2007) Competencies for young European higher education graduates: labor market mismatches and their payoffs. High Educ 55(2):219–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-006-9050-4

Geldhof GJ, Preacher KJ, Zyphur MJ (2014) Reliability estimation in a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis framework. Psychol Methods 19(1):72–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032138

Gruenwald, H (2020). Covid-19 and Education Revisited

Hardie B, Highfield C, Lee K (2020) Entrepreneurship education today for students unknown futures. J Pedagog Res 4(3):401–417. https://doi.org/10.33902/jpr.2020063022

Haris N, Jamaluddin J, Usman E (2023) The effect of organizational culture, competence and motivation on the SMEs performance in the Covid-19 post pandemic and digital era. J Ind Eng Manag Res 4(1):29–40

Haselberger, D, Oberhuemer, P, Pérez, E, Cinque, M, & Capasso, FD (2012). Mediating Soft Skills at Higher Education Institutions. ModEe project: Lifelong Learning Programme. https://gea-college.si/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/MODES_handbook_en.pdf

Heckman JJ, Kautz T (2012) Hard evidence on soft skills. Labour Econ 19(4):451–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2012.05.014

Hossain MM, Alam M, Alamgir M, Salat A (2020) Factors affecting business graduates’ employability–empirical evidence using partial least squares (PLS). Educ + Train 62(3):292–310. https://doi.org/10.1108/et-12-2018-0258

Hrubos, I (Ed.). (2012). Elefántcsonttoronyból világítótorony (0 ed.). Aula Kiadó. https://m2.mtmt.hu/api/publication/2295057

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Eq Modeling: A Multidiscip J 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

İçen, M (2022). The future of education utilizing artificial intelligence in Turkey. Humaniti Soc Sci Commun 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01284-4

Isaacs, S (2020). COVID-19 Education Responses and OER–OEP Policy in the Commonwealth. In S Mishra & S Panda (Eds.), Technology-Enabled Learning: Policy, Pedagogy and Practice (pp. 33-48). Commonwealth of Learning

Jacobsen M, Clifford P, Friesen S (2002) Preparing teachers for technology integration: Creating a culture of inquiry in the context of use. Contemp Issues Technol Teach Educ 2(3):363–388

Kabai I, Kabainé Tóth K, Krisztián V, Kenéz AK (2011) Párbeszéd a Kompeták nyelvén [Dialogue Lang competencies] Felsőoktatási Műhely 4:65–80

Kajewski, K, & Madsen, V (2012). Demystifying 70: 20: 10. Deakin University

Kallenberg T (2020) Differences in influence: different types of university employees compared. Tert Educ Manag 26(4):363–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-020-09058-w

Kane, GC, Nanda, R, Phillips, A, & Copulsky, J (2021). Redesigning the Post-Pandemic Workplace. MIT Sloan management review, 62(3). https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/redesigning-the-post-pandemic-workplace/

Kara, A (2021). Covid-19 pandemic and possible trends into the future of higher education: a review. J Educ Educ Dev 8(1). https://doi.org/10.22555/joeed.v8i1.183

Klassen A (2019) Deconstructing paper-lined cubicles: digital literacy and information technology resources in the workplace. Int J Adv Corp Learn (iJAC) 12(3):5–13. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijac.v12i3.11170

Korkmaz G, Toraman Ç (2020) Are we ready for the Post-COVID-19 educational practice? an investigation into what educators think as to online learning. Int J Technol Educ Sci 4(4):293–309. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijtes.v4i4.110

Kuráth G, Sipos N (2020) Competencies and success measured by net income among Hungarian HE graduates. Educ + Train 63(3):417–439. https://doi.org/10.1108/et-01-2020-0015

Kurihara Y (2020) How should higher education institutions provide lectures under the COVID-19 crisis. Educ, Soc Hum Stud 1(2):144–153. https://doi.org/10.22158/eshs.v1n2p144

Lal, BS, & Patel, N (2020). Economics of COVID-19: Digital Health Education and Psychology. Adhyayan Publishers and Distributors

Le Deist FD, Winterton J (2005) What is competence? Hum Resour Dev Int 8(1):27–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/1367886042000338227

Li, S, Xu, K, & Huang, J (2023). Exploring the influence of teachers’ motivating styles on college students’ agentic engagement in online learning: The mediating and suppressing effects of self-regulated learning ability. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02291-9

Marinoni, G, Van’t Land, H, & Jensen, T (2020). The impact of Covid-19 on higher education around the world. https://www.iau-aiu.net/IMG/pdf/iau_covid19_and_he_survey_report_final_may_2020.pdf

Mishra P, Koehler MJ (2022) Technological pedagogical content knowledge: a framework for teacher knowledge. Teach Coll Rec: Voice Scholarsh Educ 108(6):1017–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x

Musek, J (2020). Coping with Covid 19 in education. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344584382_Coping_with_Covid_19_in_education

Nguyen HC (2019) An investigation of professional development among educational policy-makers, institutional leaders and teachers. Manag Educ 33(1):32–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020618781678

Nikdel Teymori, A, & Fardin, MA (2020). COVID-19 and Educational Challenges: A Review of the Benefits of Online Education. Annals of Military and Health Sciences Research, 18(3). https://doi.org/10.5812/amh.105778

OECD. (2012). Better Skills, Better Jobs, Better Lives. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264177338-en

Pituch, KA, & Stevens, JP (2015). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences: analyses with SAS and IBM’s SPSS. Routledge

Poór, J, Balogh, G, Dajnoki, K, Karoliny, M, Kun, AI, & Szabó, S (Eds.). (2020a). COVID-19 – KORONAVÍRUS-VÁLSÁG: MÁSODIK FÁZIS: KIHÍVÁSOK ÉS HR VÁLASZOK. MAGYARORSZÁG 2020 augusztus–november. SZIE Menedzsment és HR Kutatóközpont. https://m2.mtmt.hu/api/publication/31629472

Poór, J, Balogh, G, Dajnoki, K, Karoliny, M, Kun, AI, & Szabó, S (Eds.). (2020b). Koronavírus-válság kihívások és HR válaszok - Magyarország 2020. A kutatás első fázisának kiértékelése. Magyar Agrár- és Élettudományi Egyetem. https://m2.mtmt.hu/api/publication/31629472

Pötzsch H (2019) Critical digital literacy: technology in education beyond issues of user competence and labour-market qualifications. tripleC: Commun Capital Crit 17(2):221–240. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v17i2.1093

Prasetio AP, Azis E, Fadhilah D, Fauziah A (2017) Lecturers’ professional competency and students’ academic performance in Indonesia higher education. Int J Hum Resour Stud 7(1):86–93

Rassudov, L, & Korunets, A (2020). COVID-19 Pandemic Challenges for Engineering Education 2020 XI International Conference on Electrical Power Drive Systems (ICEPDS)

Sá MJ, Serpa S (2020) COVID-19 and the promotion of digital competences in education. Univers J Educ Res 8(10):4520–4528. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.081020

Shankar K (2020) The impact of COVID‐19 on IT services industry ‐ expected transformations. Br J Manag 31(3):450–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12423

Sibiya, MR, Legodi, LT, & Sengani, F (2020). Remote Learning Amid Covid-19 and Lockdown: Lecturers’ Perspectives. PONTE Int Sci Res J 76(10). https://doi.org/10.21506/j.ponte.2020.10.15

Singh A, Chander M (2020) COVID 19 and higher education. Aegeaum J 8(9):166–186

Sipos N, Jarjabka A, Kurath G, Venczel-Szako T (2020) Higher education in the grip of COVID-19: 10 years in 10 days? - Quick report on the effects of the digital switchhover at work at the University of Pecs. Civ Szle 17:73–91

Succi C, Wieandt M (2019) Walk the talk: soft skills’ assessment of graduates. Eur J Manag Bus Econ 28(2):114–125. https://doi.org/10.1108/ejmbe-01-2019-0011

Tang JT, Mo D (2022) The transactional distance in the space of the distance learning under post-pandemic: a case study of a middle school in Northern Taiwan using gather to build an online puzzle-solving activity. Interact Learn Environ 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2121731

Teng W, Ma C, Pahlevansharif S, Turner JJ (2019) Graduate readiness for the employment market of the 4th industrial revolution. Educ + Train 61(5):590–604. https://doi.org/10.1108/et-07-2018-0154

Tóth-Pajor Á, Bedő Z, Csapi V (2023) Digitalization in entrepreneurship education and its effect on entrepreneurial capacity building. Cogent Bus Manag 10(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2210891

Tumwesige J (2020) COVID-19 Educational Disruption and Response: Rethinking e-Learning in Uganda. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Ed

Walker J, Brewster C, Fontinha R (2020) Consultation on the impact of Covid-19 on the working lives of business, management and economics’ academics in UK 2020. In. Reading: Henley Business School, University of Reading

WHO (1994) Life skills education for children and adolescents in schools. Pt. 1, Introduction to life skills for psychosocial competence. Pt. 2, Guidelines to facilitate the development and implementation of life skills programmes. In (2nd rev ed.). World Health Organization, Geneva

Yunusa AA, Oyelere SS, Dada OA, Agbo FJ, Sanusi IT (2020) Disruptions of Academic Activities in Nigeria: University Lecturers’ Perceptions and Responses to the COVID-19. LACLO IEEE

Žeravíková I, Tirpáková A, Markechová D (2015) The analysis of professional competencies of a lecturer in adult education. SpringerPlus 4:1–10

Zhao R, Li L (2023) Pressure, state and response: configurational analysis of organizational resilience in tourism businesses following the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01788-7

Acknowledgements

Project no. TKP2021-NKTA-19 has been implemented with the support provided from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund of Hungary, financed under the TKP2021-NKTA funding scheme.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Pécs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Gabriella Kuráth, Ákos Jarjabka, and Norbert Sipos; Methodology: Gabriella Kuráth and Norbert Sipos; Formal analysis and investigation: Norbert Sipos and Gabriella Kuráth; Writing - original draft preparation and review: Gabriella Kuráth, Ákos Jarjabka, and Norbert Sipos; Funding acquisition: Gabriella Kuráth, Ákos Jarjabka, and Norbert Sipos; Resources: Norbert Sipos; Supervision: Ákos Jarjabka; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the University of Pécs Rector’s Cabinet Research Committee.

Informed consent

Not applicable, the article is based on an anonymous database investigation, and the data handling has been detailed in a GDPR-based data regulation. By filling out the questionnaire, the participants agreed to use their answers in an anonymous way for research purposes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jarjabka, Á., Sipos, N. & Kuráth, G. Quo vadis higher education? Post-pandemic success digital competencies of the higher educators – a Hungarian university case and actions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 310 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02809-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02809-9