Abstract

Multinational investment has attracted mixed reactions from scholars and policymakers concerning their role and impact on job creation in host countries, particularly in developing economies. Using Ghana as a case study, this paper examines the impact of Greenfield investment on job creation. Proponents of multinational corporations (MNCs) argue that foreign direct investment (FDI) leads to economic growth, creates technological spillover, increases exports, and creates jobs, among other benefits. This has encouraged developing economies to adopt developmental strategies around MNC activities. Although most researchers have analyzed the impact of FDI on job creation, the unanswered question is: Does greenfield investment in Ghana lead to significant job creation in the formal sector? Extant literature considers FDI monolithic, without adequately differentiating between Green and Brownfield investments. Using granular data from the FDI Markets, this research paper fills this gap by empirically analyzing the Greenfield investment by 386 multinational companies in Ghana from 2003 to September 2020. Over the specified year range, these companies engaged in 500 projects across Ghana. Adopting the ordinary least square analysis (OLS), the study demonstrates that Greenfield investment has a statistically significant and positive impact on job creation in Ghana. Out of the 31 sectors, only the following sectors contribute significantly to job creation through Greenfield investment in Ghana: Consumer Products, Food & Beverage, Industrial Equipment, and Non-automotive transport OEM. This paper contributes to a better understanding of how government investment in fixed assets (GCF) such as roads, railways, and industrial buildings in the local economy should be managed efficiently so as not to spur inflation, which correlates negatively with jobs. Finally, this paper analyzes Chinese investments in Ghana, comparing them with U.S. investments, and examining their broader geopolitical implications, which highlights the importance of aligning foreign investments with national development strategies and adhering to international norms and standards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As Bhagwati (2007) rightly stated, “…there is a fierce debate between those who consider multinationals to be a malign influence and those who find them to be a benign force” (p. 163). Considering the growth of multinational corporations (MNCs) in size, global influence, revenues, and technical operations, compared to nation-states, MNCs’ activities are often associated with growth and development. Gilpin and Gilpin also acknowledged that “the world’s largest MNCs account for approximately four-fifths of world industrial output while typically employing two-thirds of their workforce at home” (2001, p. 289). Thus, some of the positive effects of multinational activities on a host country’s economy include productivity and technology spillover, exports, employment, and economic growth, as was emphasized by the United Nations during its International Conference on Financing for Development in Mexico in 2002.

“Private international capital flows, particularly foreign direct investment…are vital complements to national and international development efforts. Foreign direct investment contributes toward financing sustained economic growth over the long term. It is especially important for its potential to transfer knowledge and technology, create jobs, boost overall productivity, enhance competitiveness, and ultimately eradicate poverty through economic growth and development” (U.N., 2002, p. 5).

Therefore, multinational corporations (MNCs) foreign direct investment (FDI) serves as a development strategy for most developing economies (Osei, 2019). FDI from MNCs leads to employment opportunities by directly hiring local workers in their subsidiaries. It also creates indirect employment through links with local suppliers or affiliates who are attracted to the market. Finally, MNCs contribute to higher income in the host country through the multiplier effect (Vacaflores et al., 2017). Hence for host countries particularly in Africa, attracting MNCs serves as an economic instrument for growth and development (Assamah and Yuan, 2023).

Ghana, commissioned as the secretariat of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AFCFTA), adds to the significance of this research as the trade agreement will enhance access by multinationals on the continent, particularly in Ghana. The impact at the household and corporate levels will be significant. By 2030, “the fully integrated market of 1.7 billion people will have an estimated $6.7 trillion of combined consumer and business spending” on the African continent (Fofack, 2020). Although Ghana is not a traditional FDI destination in Africa, its past decade of economic growth and political stability has enabled the country to attract significant FDI over the past couple of years. According to the fDi 2020 report, “Ghana entered the top 10 destinations by number of FDI projects in the Middle East and Africa,” a 56 percent increase from 2018 (fDi Report, 2020, p. 21). Therefore, as investors seek opportunities on the continent for profit, to what extent does that generate employment opportunities for Ghanaians?

Regarding sectoral and industry analysis, the data unveils the following sectors as having a significant impact on the Ghanaian economy regarding job creation: Automotive OEM, Building materials, Business machines, Consumer Products, Food & Beverages, Metals, and Textiles. Sectors such as Healthcare, Industrial Equipment, and Electronic Components do not significantly impact Ghana’s job creation. We recognize that most Chinese companies invest in the Automotive OEM sector and Business machines and equipment. In contrast, the U.S. companies focus more on the Food & Beverage, Metal sector, Healthcare, software, and I.T. services.

Literature review

The presence of MNCs in Ghana can be traced back to the colonial era when companies such as United Trading Company (UTC), Paterson and Zochonis (P.Z.), Kingsway, Lever Brothers (Unilever), and the United African Company (UAC) entered the Ghanaian market, with some still operating today (Williams et al., 2017). After independence, Ghana’s effort to attract foreign investment has been attributed to the following reasons: (1) the country has enormous natural resources but lacks the capital and technology to explore them efficiently, (2) the economy is mainly dependent on agricultural products as its primary export commodity, (3) the economy is overly dependent on the importation of goods and services (Dagbanja, 2014). This has led to enacting domestic laws and national policies to promote the flow of capital investment. The first legislation enacted after Ghana’s independence was the Capital Investment Act (Act 179) in 1963 to promote and protect foreign investment (Dagbanja, 2014). Subsequently, policies such as the Economic Recovery Program (ERP) were initiated in 1983 by the Ghanaian government to support the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Adopting a market-oriented approach, the ERP liberalized the external sector and significantly reduced the macroeconomic imbalances (IMF). The country’s balance of payment registered a sizeable overall surplus throughout that period. However, the Structural Adjustment Program reform slowed economic growth, hampering private investment, export growth, and economic growth. The government’s quest to create an enabling legal environment to attract FDI led to the enactment of the investment code, Ghana Investment Promotion Center (GIPC) Act in 1994 (Act 478) (Abor and Harvey, 2008). Tables 1 summarize the various legislatures enacted since independence, outlining their primary purpose and significant accomplishments. Table 2 provides a description of the variables.

Available data shows that between September 1994 and June 2002, the Ghana Investment Promotion Center registered 1309 FDI projects, with 388 in the service sector, 368 in manufacturing, 153 in tourism, 106 in building and construction, 105 in agriculture, and 91 in export trade. These FDI sources include Great Britain, India, China, the USA, Lebanon, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Netherlands, Canada, France, South Africa, Nigeria, and Malaysia.

Regarding employment opportunities in Ghana, FDI “has had direct and multiplier effects on the level of employment, its quality, and the skills of the labor force” (Fu, 2020 p. 52). Although it has not contributed to labor-intensive activities in some sectors, such as the mining sector, due to capital-intensive production, these regions are training their labor force with specific engineering and management skills to make them relevant in other sectors and high-paying jobs outside the mining sector.

An empirical study by Osei (2019) shows that for every 1 percentage increase in FDI in Ghana, it led to a 3 percent growth in employment between the years 2000 and 2016. This study identifies some critical factors influencing FDI’s impact on employment within the Ghanaian economy, including wage structure, investment freedom, and the nature of the subsectors. This study is consistent with other authors who found that FDI has a positive and significant impact on employment in Ghana (Ato-Mensah and Long, 2021; Awunyo-Vitor and Sackey, 2018). However, these scholars found that FDI does not affect Ghanaian employment in the short run but rather affects economic growth and, ultimately, employment and poverty reduction (Obeng-Amponsah and Owusu, 2023; Tee et al., 2017).

In terms of the source countries of these FDI, Boakye-Gyasi and Li (2017) argue that in the case of Ghana, MNCs from China, India, the USA, and South Africa have significantly contributed to positively shifting the Ghanaian economy. However, the relative impact of these countries on the Ghanaian labor market is sector-bound. Chinese companies have had a significant impact on the Ghanaian manufacturing sector, investing in the plastic industry, steel, construction materials, paper, and artificial hair wigs (Brautigam et al., 2018). Companies from the USA and South Africa focus more on both the Agricultural and Service sectors, while Indian MNCs employ more Ghanaians in the Agricultural sector (Boakye-Gyasi and Li, 2015).

According to Yeboah and Anning (2020), between 2013 and 2018, about 85% of the employment opportunities created by these MNCs were for Ghanaians. Without strong government policies, these positive impacts of FDI on employment in Ghana would not have been possible, especially in the case of Ghana (Boakye-Gyasi and Li, 2015). Table 1 shows the significant investment laws enacted by the Ghanaian parliament since 1963, along with a brief description of their objectives.

Regarding government institutions and policies, some researchers have associated a positive relationship between foreign direct investment (FDI) and host country governance, linking good governance with higher FDI inflows (Liou et al., 2016; Du et al., 2008). However, Fon and Alon (2022) argue that FDI from Chinese state-owned enterprises flows more to African countries with weak institutions. They suggest these enterprises can leverage good China-Africa diplomatic ties to avoid the potential seizure of their assets in weakly governed countries.

Role of multinational corporations (MNCs) in developing economies

Since the mid-1980s, many developing countries have opened their economies to FDI inflow (Nunnenkamp, 2004). Several factors explain this liberalization wave; developing countries welcomed these multinational corporations as “social and cultural change agents” (Meleka, 1985 p. 37). They believed that by opening to multinationals, they could emulate the Western ways. Nevertheless, this enabled these MNCs to operate in environments limited by regulations and restrictions. According to Dijk and Marcussen (1990), the focus of multilateral institutions on infrastructural development in developing countries after the Second World War led to promoting the structural adjustment programs (SAP) that mandated third-world countries to open their economies to trade. SAP discouraged public sector and state involvement in industrial development while promoting exports and the private sector. The significant policy shift among developing countries from import substitution to outward-looking can also be attributed to the inefficiencies associated with import substitution, the success of the newly industrialized economies (NIEs), which were export-led, and increased global production (Lall and Narula, 2004).

Has this openness in the economy led to poverty alleviation and better opportunities through FDI inflows? Researchers and policymakers have mixed evidence regarding the role of MNCs in developing countries. Bhagwati (2007), however, emphasized that the scientific analysis of trade effects on poverty is very compelling and supports MNCs’ argument. This trade effect on poverty is based on a two-step argument, “trade enhances growth, and that growth reduces

poverty” (Bhagwati, 2007, p. 53). As Cohen (2007) argues through research conducted by the McKinsey Global Institute, FDI also leads to improved living standards. Because of MNCs’ value for skilled labor and their use of pollution abatement equipment, Cohen (2007) added that they create socio-economic conditions that lead to improved human rights and environmental quality in developing economies. Sen (1999) will consider this improvement as a reduction in poverty as it enhances human freedom. Neal’s (1994) insightful contribution acknowledged that MNCs investment in developing economies not only creates jobs and improves earnings but more so opens oppressive regimes and subversive cultures to the global market such that “dictatorships are more likely to collapse, or to change, in the face of an enriched (and thereby empowered) population that has adopted the twin values of the global marketplace, consumerism, and entrepreneurialism” (p. 22). In terms of capital and state benefits, the conservative oligopolistic school claims “MNCs are of more benefit to developing states because they serve as providers of capital which may not be readily available in Africa for the exploitation of untapped resources, especially in the mining and drilling sectors”(Amusan, 2018, p. 46).

Contrary to the benefits mentioned above regarding MNCs’ role in developing countries, some researchers argue that MNCs disregard human rights, especially in Africa. Human rights are limited mainly by the West to political and civic rights, mainly considering the freedom of speech, movement, and life (Amusan, 2018). As Donnelly and Whelan (2019) emphasized, if human rights impact development, then economic rights turn out to be duties to help provide for the needy. Critics assert that, due to MNCs’ corrupt nature, they like to operate in conflict areas in Africa where they can siphon resources for their benefit, underpinning why numerous oil companies are found in Sudan, South Sudan, and Nigeria (Amusan, 2018). Researchers like Nunnenkamp (2004) have also argued that FDI does not alleviate poverty; it instead widens the income gap by empowering skilled workers and worsening the poor’s relative income.

Bhagwati (2007), in his book chapter, Corporations: Predatory or Beneficial? Attempted to address most of the criticism against MNCs. Although he acknowledged MNCs’ political intrusion in developing economies, he added that given the rise in democracy and the age of digitization, such corrupt practices will now be difficult to hide. He further argued that it is a grievous mistake to compare MNCs’ size to the GDP of developing countries to portray developing countries as weak negotiators. Moreover, when it comes to labor rights and worker compensation, although ethical values require MNCs to uphold acceptable labor standards, it is still the host government’s responsibility to enforce labor laws.

Although FDI has a positive impact on growth in other developing countries, Nunnenkamp (2004) indicates that “it is mainly in African countries that FDI may have limited effects on economic growth and poverty alleviation” (p. 666). Nunnenkamp (2004) attributed the lack of positive effect of FDI on economic growth to FDI flow volatility in five African countries (Somalia, Gabon, Sierra Leone, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Algeria). Others attribute the negative effect of FDI in developing economies to globalization. Nevertheless, Lall and Narula (2004) assert that the answer is simple “the removal of restrictions on FDI does not create the complementary factors that MNCs need; it only allows them to exploit existing capabilities more freely” (p. 4). The controlling strategy of MNCs in the past has made them successful at the expense of developing countries, Meleka (1985) argued. Deploying unnecessary technology, which could lead to unemployment, providing elusive and vague information about their activities, transferring profits overseas when developing countries anticipated the reinvestment of profits into the economy, and influencing the host country’s policies and politics are some of the controlling advantages exerted by MNCs in developing countries in Africa.

In summary, developing countries must understand that following the Washington consensus, which alludes to FDI flows, generates positive externalities for domestic firms; it is critical to consider the following factors to benefit from the increased FDI flow (Lall and Narula, 2004). For FDI to be beneficial, developing countries must grasp the competence and scope of operation of that subsidiary in their country. The role played by a subsidiary in the MNC giant network determines the nature of the FDI and the local competence they will require to achieve that. Although it is sometimes difficult to ascertain, knowing the motive of an FDI, as discussed above, is critical to determining how externalities and linkages develop. Thirdly, MNC linkages are significant if developing countries benefit through international technology spillovers, backward linkages, labor turnover, or horizontal linkages. What is important here is the host country’s technological capability, the domestic market orientation of subsidiaries, and the entry mode, whether they were established through Greenfield investment or mergers and acquisitions (M&As). Lastly, understanding the nature of the MNC assets can help host countries build appropriate absorptive capacity.

Description of variables

A dependent variable is the response measured or the presumed effect, whereas an independent variable is the manipulated variable or the presumed cause. The dependent variable used in this research is jobs created, and the independent variables are outlined in the table below.

Data structure

The dataset compiled for analysis comprises both time series and cross-sectional data merged together. The foreign direct investment (FDI) project data, including jobs and capital investment indicators, represents repeated cross-sections, with each investment project an independent observation across the June 2003 to September 2020 period. In total, the FDI data covers 500 investment projects across 386 unique firms in Ghana. This project-level FDI data does not constitute panel data. The macroeconomic control variables, including GDP, labor force participation rate, gross capital formation, inflation rate, tax burden, governance integrity, business freedom, and property rights variables are time series data. They pertain to Ghana and are measured annually from 2003 to 2020.

Hence, the compiled dataset has a mixed structure combining both time series and independent cross-sectional observations. The national-level annual indicators capture trends over time (time series data) while the individual FDI projects in each year provide separate cross-sectional data points. This combined dataset allows an assessment of how macroeconomic factors relate to firm-level FDI project activities.

Data analysis

Ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions were used to find the empirical relationship between the dependent and independent variables in the study. Due to the data distribution, different regression models were adopted to transform the data into the best linear shape. The following four equations represent the empirical models used for the analysis in this study:

The various models will be discussed in the findings and analysis session. However, using STATA version 16, the OLS regression identified the effect of a variable while controlling for the other observable differences. OLS minimizes the sum of squares between the observed sample values and the fitted values in the models.

Findings

Table 3 displays the descriptive statistics of the variables in this study. For our key variables, the average Jobs created within the year range is 197, while the average capital invested was $99 million. With a maximum of $7900 million investment in 2007 from Eni Spa, an Italian company. Table 4 displays the regression output for the four models, showing the effect of capital investment on job creation in Ghana.

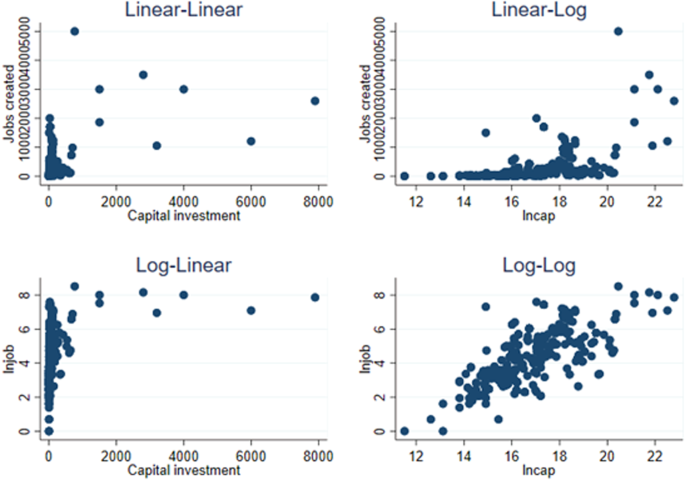

Model 1 shows the untransformed bivariate regression between Greenfield investment and jobs generated by the 386 companies. From Table 4, our model 1 equation becomes \({{{\rm {Jobs}}}}_{i}=153.4+0.445{{{\rm {Capin}}}}_{i}\). Which means that for every $1 million increase in Greenfield investment, the expected job created in Ghana increases by 0.445. The positive coefficient is statistically significant at the 0.001 level. Although this bivariate regression shows a significant statistical result, a scatter graph of the two variables shows a nonlinear relationship (as shown by the Linear–Linear graph in Fig. 1). However, using the logarithmic function, the relationship between these two variables was transformed so we could fit a linear equation through the points, as displayed by the Log–Log graph in Fig. 1. Thus, Model 2 displays this log–log function \({{{\rm {lnjob}}}}_{i}=-8.012+0.719{{{\rm {lncap}}}}_{i}\). Which shows capital investment to be statistically significant at the 0.001 level. Since this is an elasticity model, a one percent change in capital investment predicts a 0.719 percent increase in job creation in Ghana. Although we cannot directly compare the R2 between models 1 and 2, we realize a substantial increase in the R2 for model 2.

Model 3 builds on the Log–Log function by introducing economic indicators such as GDP, GCF, LFPR, and inflation rate. By controlling for these factors, the coefficient for capital investment remains statistically significant at the 0.001 level but decreased slightly by 0.8 percent compared to Model 2. Although this decrease is not massive, the coefficients for the economic indicators were all significant. GDP is statistically significant at 95 percent confidence intervals, while GCF, LFPR, and inflation are highly statistically significant at the 0.001 level. The R2 also increased by 2 percent (0.535) compared to Model 2. The equation for model 3 becomes:

The coefficient for capital investment is interpreted as a one percent change in capital investment leading to a 0.711 percent increase in jobs while holding GDP, GCF, LFPR, and inflation constant.

Model 4 controls the effect of the rule of law, government size, and regulatory efficiency on job creation in Ghana. The effect of the rule of law was measured by introducing two indexes, government integrity, and property rights, as adopted by the Heritage Foundation. The business freedom index was used to measure the regulatory efficiency of the Ghanaian market, and the tax burden represents the government’s size. Capital investment remains statistically significant when we control the rule of law, government size, and regulatory efficiency, but GDP, GCF, LFPR, and inflation became statistically insignificant. However, this model is statistically significant in government integrity, business freedom, and property rights, while the tax burden is insignificant. Interestingly, although the rule of law indexes (government integrity and property rights) were statistically significant at the 99 percent confidence interval, they correlate negatively with jobs created through Greenfield investment in Ghana between 2003 and 2020. Only business freedom positively affects the dependent variable, and it is significant at the 95 percent confidence interval.

Finally, regarding which sectors significantly support the Ghanaian economy in terms of job creation through domestic government investment, this regression model was adopted

Sec represents the variable sector where multinationals have invested between 2003 and 2020, as classified by the fDi Market database. The interaction allows us to see the effect of GCF on the sectors and how these sectors ultimately impact our dependent variable. Out of the 32 sectors, only 13 showed a positive correlation and are statistically significant, as shown in Table 5 below, when the effect of GCF is considered on the sectors. The highly significant sectors in job creation at the 0.001 level while considering the effect of government’s investment in the local economy are Automotive OEM, Business Machines & Equipment, Consumer Products, Food & Beverages, Metals, and Textile. With an R2 of 0.74, it implies that our independent variables explain 74 percent of the variation in the dependent variable (Jobs).

Discussion

The result in this empirical paper is supported by previous studies that examined the relationship and effect of foreign direct investment on job creation in Ghana. Model 1, a linear–linear function, rejects the hypothesis that Greenfield investment does not positively and significantly impact employment. Model 2, a log–log function, also confirms the findings of model 1. Thus, examining the effect of Greenfield investment on job creation in Ghana, the bivariate models (1 and 2), with an R2 of 0.26 and 0.52, respectively, confirm that Greenfield investment has a significant positive effect on job creation.

Introducing national economic variables in model 3 to avoid any left-out variable bias, we realized that the R2 increased by 2 percent. This implies that governmental development plans must boost GDP and increase fixed assets in the Ghanaian economy, such as constructing roads, railways, industrial buildings, and the purchase of machinery and equipment. While making all this progress, the model warns that inflation levels must be low since it negatively correlates with jobs. As I have emphasized the importance of GCF in constructing and purchasing fixed assets, it is imperative to understand that these assets must be intended for producing goods and services. Therefore, they must be considered “produced assets” (OECD, 2022).

For our unrestricted model 4, we realized that the R2 increased by 3.9 percent compared to model 2. By introducing the indexes that measure the rule of law in Ghana, regulatory efficiency, and government size, all the economic indicators introduced in model 3 became insignificant. Using the F-test, the overall significance of the independent variables was assessed, which proved significant at a p-value of 0.000; thus, we reject the null hypothesis that the coefficients are zeros. The F-test for model 3 is also very significant, which means that the independent variables together have explanatory power. However, quite interesting, model 4 alerts us of the possibility of corruption in the Ghanaian economy.

The two indexes measuring the rule of law in the country (Government Integrity and Property Rights) correlate negatively with the dependent variable and are statistically significant at 0.01. Thus, every one percent change in government integrity leads to a 5.1 decrease in jobs. At the same time, a one percent change in the protection of property rights will cause a 22 percent decrease in jobs. Although these results are intriguing, they support the claims of MNC critics who argue that MNCs investing in Africa target corrupt countries with weak institutions so they can get away with their misdemeanors. Ironically, business freedom, measured by how easy it is to start and obtain a business license in Ghana, has a positive and significant effect on job creation. This is very reasonable, as every multinational would like a quick and easy business registration process to commence operations in Ghana. The regression model indicates that every one percent change in business freedom leads to a 2.9 percent increase in job creation while controlling for the other factors. This should encourage policymakers to ensure that the process of business registration, the cost involved, and the waiting periods are reasonable to foster a good business environment.

Finally, as stated above, only 13 of the 31 sectors positively affect job creation in Ghana when the government’s investment is factored in—indicating that government investment in infrastructural development influences firms’ decisions to invest in specific sectors, thus creating labor opportunities. The government of Ghana is required to strategically extend infrastructures in communications, transportation, health, education, and utilities to various districts of the country. In order to attract MNCs into such districts or regions.

Robust check

To ensure the robustness of our regression results, we conducted checks for multicollinearity and heteroskedasticity in our OLS regression analysis. These issues are critical, as they have the potential to affect the validity and reliability of regression results, potentially leading to incorrect inferences and misinterpretations of relationships between variables (O’Brien, 2007). High multicollinearity makes determining the individual importance of correlated predictors difficult (O’Brien, 2007). Using the estat vif syntax in Stata, the variance inflation factors (VIFs) for both Models 3 and 4 showed the absence of severe multicollinearity among the predictor variables.

Additionally, the presence of heteroskedasticity can seriously distort findings and lead to erroneous conclusions in significance testing (Hayes and Cai, 2007). The Breusch–Pagan/Cook–-Weisberg test was utilized to test for heteroskedasticity in the residuals of our models. The results indicated potential heteroskedasticity in the data, therefore robust standard errors were calculated to account for this. While coefficient estimates remain unchanged, the robust standard errors adjust for heteroskedasticity and provide more conservative and cautious statistical inference (Hayes and Cai, 2007). By addressing these diagnostic tests, we enhanced the credibility of our analysis and ensured appropriate interpretation of the relationships between the variables.

Implications: Chinese investment in Ghana

China’s engagement in Africa has brought substantial assistance, particularly in infrastructure development and economic partnerships, contributing to the continent’s growth and stability. In Ghana, particularly, China’s FDI holds significant implications for the country’s economic development, bilateral relations, and regional dynamics. The influx of Chinese investments has also enhanced Ghana’s access to international markets and created opportunities for knowledge transfer and technological spillovers (Tang and Gyasi, 2012). However, concerns have been raised about the sustainability of Chinese-financed projects, environmental impacts, and the influx of Chinese labor in lieu of employing the local workforce. Critics argue that the lack of transparency in Chinese investments and their focus on resource extraction might exacerbate Ghana’s economic vulnerabilities and undermine long-term development objectives (Felix Ayadi et al., 2014). Furthermore, the growing presence of China in Ghana has the potential to reshape the region’s geopolitical landscape and recalibrate Ghana’s traditional alliances with Western countries (Tang and Gyasi, 2012). While the investments have fostered closer political and economic ties between China and Ghana, it is crucial for the Ghanaian government to ensure that these projects align with national development strategies, promote long-term, inclusive growth, and adhere to international norms and standards. This involves striking a balance between attracting foreign investment, safeguarding the interests of local communities and the environment, and maintaining a diversified portfolio of international partnerships.

In the discourse surrounding foreign investment, it’s crucial to distinguish between Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and other forms of financial flows, such as developmental assistance, grants, or loans. Traditionally, FDI refers to an investment made by a firm or individual in one country into business interests located in another country, often by buying a company in the target country or expanding the operations of an existing business. While Chinese infrastructure projects, such as road constructions in Ghana, may not fit the classical definition of FDI, they represent significant capital infusion with long-term strategic interests, which have broader implications than mere infrastructural development. Similarly, while US Aid is predominantly development assistance and grants, the presence of US companies, with their extensive investments and operations in Ghana, can be likened to FDI due to their impact on the local economy and their influence over policy.

From the data, we recognize that the majority of China’s investments are spread across infrastructure, natural resources, and manufacturing sectors. As one of the major investors, China has contributed to the expansion of Ghana’s physical infrastructure, capacity building, and technological advancement, thereby playing a key role in the country’s pursuit of industrialization and economic diversification. Examining the sectors in which China invests in Ghana is crucial for several reasons, including fostering economic growth and diversification, guiding resource allocation and setting priorities, identifying social and environmental implications, understanding geopolitical considerations, and informing policy decisions. By analyzing China’s investment patterns, the Ghanaian government can develop targeted policies to promote sustainable development, allocate resources efficiently, and prioritize investments for maximum benefits, such as job creation and technology transfer. Additionally, recognizing potential social and environmental impacts allows the government and stakeholders to develop mitigation strategies and ensure investments align with national goals. Furthermore, understanding China’s broader geopolitical strategy in Africa enables Ghana to navigate international relations and balance alliances while protecting its national interests. Ultimately, this knowledge empowers the Ghanaian government to develop policies that promote responsible investment, ensure compliance with international standards, and protect the country’s long-term interests.

Infrastructure sector

China has been instrumental in bolstering the health infrastructure of many African nations. They’ve spearheaded numerous projects that include the construction of hospitals, clinics, and diagnostic centers across the continent (Yuan, 2023). China’s investment in Ghana’s infrastructure sector has been significant over the past few decades (Boakye-Gyasi and Li, 2016). This investment has been driven by several factors, including China’s desire to secure natural resources, expand its global influence, and create new markets for Chinese products and services. Additionally, Ghana’s stable political environment and relatively open market make it an attractive destination for foreign investment. China’s investment in Ghana’s infrastructure has had several positive impacts. Firstly, it has helped to improve Ghana’s transportation, energy, and telecommunications sectors, leading to better connectivity and economic growth. Secondly, it has created jobs, both directly and indirectly, contributing to poverty reduction and improved living standards. Finally, these investments have fostered stronger bilateral ties between China and Ghana, leading to increased cooperation in various sectors beyond infrastructure (Boakye-Gyasi and Li, 2015).

China has significantly invested in various infrastructure projects in Ghana, such as the Bui Dam, which is a hydroelectric power project on the Black Volta River with a capacity of 400 MW, providing the country with increased electricity generation capacity and energy security (Yankson et al., 2018). Another noteworthy project is the Atuabo Gas Processing Plant, financed by China, which enables Ghana to process its natural gas resources, offering a cleaner energy source and reducing dependency on imported fuel (Ablo and Asamoah, 2018). China has also contributed to the expansion of the Tema Port, one of Ghana’s primary ports, resulting in increased capacity and efficiency, ultimately promoting trade and economic growth. Furthermore, China’s investment in Ghana’s railway infrastructure includes the construction of the Tema-Akosombo railway line, connecting the Tema Port to the Volta Lake, and the planned 1400-km railway network linking key cities such as Accra, Kumasi, and Tamale to bolster trade and transportation within the country. Finally, the $2 billion Sinohydro Infrastructure Agreement signed in 2018 seeks to develop a range of infrastructure projects (Neal and Losos, 2021), including roads, bridges, and hospitals, in exchange for Ghana’s refined bauxite, further strengthening the collaboration between the two nations.

Natural resources sector

Another major investment from China is Ghana’s natural resources sector. If China’s investment in the infrastructure sector allows China to more easily secure access, the direct investment in natural resources lets China access and extract it (Alden and Alves, 2009). It fuels China’s economic growth and fosters strategic partnerships. For Ghana, the investment helps Ghana better develop and exploit its resources, leading to economic growth and job creation. It also strengthens the bilateral relationship between China and Ghana, leading to increased cooperation in various sectors. It also allows China to secure a stable supply of critical resources to sustain its rapidly growing economy.

Chinese investments in Ghana’s natural resources sector have been significant across various industries. In 2010, the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) acquired a 40% stake in the Jubilee oil field for $1.4 billion, granting China access to Ghana’s oil resources while enabling Ghana to develop its oil industry (Hardus, 2014). Additionally, China National Offshore Oil Corporation’s (CNOOC) investment in the Sankofa Gas Project in Ghana is a perfect example. The Sankofa Gas Project is a deep-water natural gas field located off the coast of Ghana (Morgan et al., 2021). In 2013, CNOOC acquired a stake in the Sankofa Gas Project through a partnership with Italian energy company Eni and Ghana’s state-owned oil company, Ghana National Petroleum Corporation (GNPC). The project is aimed at producing natural gas for Ghana’s domestic market, as well as exporting a portion of the gas to China. This investment not only provided financial and technical support for Ghana’s energy sector but also secured a stable supply of natural gas for China, which is a critical resource for its rapidly growing economy. Another notable agreement between the two nations is the 2018 Sinohydro deal, as previously mentioned, which exchanged $2 billion worth of Ghana’s refined bauxite for Chinese-financed infrastructure projects, allowing Ghana to develop its bauxite resources while China secured a long-term supply of this crucial aluminum production component (Neal and Losos, 2021). Lastly, Chinese companies have significantly invested in Ghana’s timber sector, contributing to the growth of the forestry industry and increasing trade between the two countries.

Manufacturing sector

The third largest investment from China to Ghana is the country’s manufacturing sector. Investing in manufacturing supports Ghana’s industrialization efforts, leading to economic growth, job creation, and technological transfer. Like the previous two sectors, it also strengthens the bilateral relationship between China and Ghana, promoting further cooperation in various sectors. Most importantly, it allows Chinese companies to establish a presence in Africa and access new markets, reducing their reliance on domestic and traditional export markets (Amanor and Chichava, 2016).

Chinese investments in Ghana’s manufacturing sector have significantly impacted various industries. For example, Twyford Ceramics, a subsidiary of Sunda International, established a $77 million ceramic tile manufacturing factory in 2016, creating jobs and providing affordable tiles to the local market (Xia, 2021). In the steel industry, Sentuo Steel has invested over $80 million in a steel plant, bolstering the local steel industry, creating jobs, and supplying raw materials for Ghana’s construction sector (Tang, 2018). Another example of China investing in Ghana’s manufacturing sector is the establishment of the eastern industrial zone (EIZ) in the Tema Free Zone, near the capital city of Accra. The EIZ is a joint project between the Ghanaian government and private Chinese investors, including the China–Africa Development Fund (CADFund) and the Tianjin TEDA Investment Holding (António and Ma, 2015). Launched in 2012, the Eastern Industrial Zone is designed to host a variety of manufacturing industries, such as electronics, textiles, pharmaceuticals, and food processing. These investments not only create employment opportunities for the local workforce but also help enhance Ghana’s industrial capabilities through the transfer of technology and expertise from Chinese companies. Furthermore, the EIZ allows Chinese companies to establish a presence in Africa, access new markets, and reduce their reliance on domestic and traditional export markets.

In conclusion, China’s investments in Ghana across various sectors, including infrastructure, natural resources, and manufacturing, have significantly impacted both countries. These investments are driven by China’s desire to secure essential resources, expand its global influence, access new markets, and diversify its manufacturing base. By investing in Ghana’s key industries, China has contributed to the nation’s economic growth, job creation, and technological transfer while simultaneously benefiting from access to valuable resources and new markets. These collaborations have not only strengthened the bilateral relationship between China and Ghana but have also set the stage for increased cooperation and shared prosperity in the future. China’s investments in Ghana and other African countries have substantial implications for international relations, contributing to shifting global power dynamics as China challenges the traditional dominance of Western powers. This economic interdependence fosters closer ties and mutual interests, while also increasing China’s diplomatic influence and soft power projection. Additionally, China’s investment strategy offers an alternative development model that emphasizes infrastructure, resource extraction, and manufacturing, promoting regional integration and increased trade among African nations. It is also important to note that China’s investment recently often comes with assertive diplomatic rhetoric, highlighting its position as a responsible player on the global stage, while also pointing out the deficiencies of other countries when assisting other countries (Yuan, 2023). As China continues to expand its global presence, the evolving relationships between China and countries like Ghana will significantly impact the international political and economic landscape in the years to come.

The difference between U.S. investment in Ghana and China’s investments in Ghana is often centered on infrastructure, agriculture, health, education, and good governance. The U.S. prioritizes sustainable development, capacity building, and human rights in its investment strategy. Examples include the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) compacts, USAID programs, and the Power Africa Initiative. On the other hand, China’s investments in Ghana mainly focus on infrastructure, natural resources, and manufacturing. Chinese investments are often directed towards large-scale projects like ports, railways, roads, and resource extraction facilities, aiming to facilitate trade and secure access to resources for China’s growing economy.

U.S. investments in Ghana often involve grants, aid programs, and technical assistance through agencies like USAID and the MCC. These investments usually have a more explicit focus on poverty reduction, capacity building, and sustainable development. China’s investments in Ghana are typically structured as loans, with some tied to resource-for-infrastructure deals, such as the Sinohydro Agreement (Neal and Losos, 2021). China often provides financing through state-owned banks and institutions, such as the China Development Bank and the Export–Import Bank of China. U.S. investments in Ghana are part of broader diplomatic efforts to promote democracy, human rights, and the rule of law, which contribute to the projection of American values and soft power. China’s investments in Ghana are part of its broader diplomatic strategy to expand its global influence, strengthen its position as a global power and establish an upstanding international image (Yuan, 2023), and secure access to resources needed for its domestic growth. It is important to know that China’s soft power projection in Ghana also includes cultural exchanges, scholarships, and Confucius Institutes.

In summary, the main differences between the U.S. and China’s investments in Ghana lie in their focus areas, development approaches, financing mechanisms, and soft power and diplomatic goals. While both countries seek to foster economic growth and strengthen bilateral ties, their investment strategies and priorities reflect their distinct national interests and development philosophies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper sheds light on the impact of Greenfield investment on job creation in developing economies, using Ghana as a case study. The study demonstrates that Greenfield investment by multinational companies positively contributes to job creation in Ghana, with significant effects in the Consumer Products, Food & Beverage, Industrial Equipment, and Non-automotive transport OEM sectors. These findings underline the importance of differentiating between Greenfield and Brownfield investments when analyzing the impacts of FDI on job creation.

The research also emphasizes the need for efficient management of government investment in fixed assets to avoid spurring inflation, which negatively correlates with job creation. Chinese investments in Ghana have played a significant role in the country’s economic development and have had notable implications on bilateral relations, regional dynamics, and international markets. China’s investments, which predominantly focus on infrastructure, natural resources, and manufacturing sectors, have promoted economic growth, job creation, and technology transfer in Ghana. However, concerns regarding the sustainability of Chinese-financed projects, environmental impacts, and the lack of transparency in their investments call for a careful assessment of these collaborations. Ultimately, fostering responsible investment, compliance with international standards, and safeguarding the country’s long-term interests will be crucial as Ghana continues to benefit from foreign investments, particularly from China. The evolving relationships between China and countries like Ghana will significantly impact the global political and economic landscape, making it essential for stakeholders to address challenges and harness opportunities that arise from these collaborations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, SY, upon reasonable request.

References

Ablo AD, Asamoah VK (2018) Local participation, institutions and land acquisition for energy infrastructure: the case of the Atuabo gas project in Ghana. Energy Res Soc Sci 41:191–198

Abor J, Harvey S (2008) Foreign direct investment and employment: host country experience. Macroecon Finance Emerg Market Econ 1(2):213–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/17520840802323224

Amusan L (2018) Multinational corporations’ (MNCs) engagement in Africa: messiahs or hypocrites? J Afr Foreign Aff 5(1):41–62. https://doi.org/10.31920/2056-5658/2018/v5n1a3

Alden C, Alves AC (2009) China and Africa’s natural resources: the challenges and implications for development and governance. The South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA)

António NS, Ma S (2015) China’s special economic zones in Africa: context, motivations and progress. Euro Asia J Manag 44:79–103

Assamah D, Yuan S (2023) Can smaller powers have grand strategies? The case of Rwanda. Insight Africa 15(1):108–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/09750878221135074

Ato-Mensah S, Long W (2021) Impact of FDI on economic growth, employment, and poverty reduction in Ghana. Open J Bus Manag 9(3):1291–1296

Amanor KS, Chichava S (2016) South–south cooperation, agribusiness, and African agricultural development: Brazil and China in Ghana and Mozambique. World Dev 81:13–23

Awunyo-Vitor D, Sackey RA (2018) Agricultural sector foreign direct investment and economic growth in Ghana. J Innov Entrep 7(1):15

Bhagwati B (2007) In defense of globalization: with a new afterword. Defense of globalization. Oxford University Press, USA-OSO

Boakye-Gyasi K, Li Y (2015) The impact of Chinese FDI on employment generation in the building and construction sector of Ghana. Eurasian J Soc Sci 3(2):1–15

Boakye-Gyasi K, Li Y (2016) The linkage between China’s foreign direct investment and Ghana’s building and construction sector performance. Eurasian J Bus Econ 9(18):81–97

Boakye–Gyasi K, Li Y (2017) FDI trends in Ghana: the role of China, US, India and South Africa. Eurasian J Econ Finance 5(2):1–16

Brautigam D, Xiaoyang T, Xia Y (2018) What kinds of Chinese ‘geese’ are flying to Africa? Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. J Afr Econ 27:i29–i51

Cohen SD (2007) Multinational Corporations and Foreign Direct Investment: Avoiding Simplicity, Embracing Complexity (1st ed., pp. ix–ix). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195179354.001.0001

Dagbanja D (2014) The changing pattern and future of foreign investment law and policy in Ghana: the role of investment promotion and protection agreements. Afr J Legal Stud 7(2):253–292. https://doi.org/10.1163/17087384-12302023

Dijk M, Marcussen H (1990) Industrialization in the Third World: the need for alternative strategies. F. Cass

Donnelly J, Whelan D (2019) International human rights, 5th edn. Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group

Du J, Lu Y, Tao Z (2008) Economic institutions and FDI location choice: evidence from US multinationals in China. J Comp Econ 36(3):412–429

FDI Report (2020) Global Greenfield investment trends. FDi Intelligence. Retrieved from http://report.fdiintelligence.com/

Felix Ayadi O, Ajibolade S, Williams J, Hyman LM (2014) Transparency and foreign direct investment into sub-Saharan Africa: an econometric investigation. Afr J Econ Manag Stud 5(2):146–159

Fofack H (2020) Making the AfCFTA work for ‘The Africa we want’. Brookings Institution, Washington, DC

Fon R, Alon I (2022) Governance, foreign aid, and Chinese foreign direct investment. Thunderbird. Int Bus Rev 64(2):179–201

Fu X (2020) Innovation under the Radar: the nature and sources of innovation in Africa. University of Cambridge ESOL Examinations

Gilpin R, Gilpin R (2001) Global Political Economy: Understanding the International Economic Order. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400831272

Hardus S (2014) Chinese national oil companies in Ghana: the cases of CNOOC and Sinopec. Perspect Global Dev Technol 13(5–6):588–612

Hayes AF, Cai L (2007) Using heteroskedasticity-consistent standard error estimators in OLS regression: an introduction and software implementation. Behav Res Methods 39(4):709–722

Lall S, Narula R (2004) FDI and its role in economic development: do we need a new agenda? Eur J Dev Res 16(3):447–464

Liou RS, Chao MCH, Yang M (2016) Emerging economies and institutional quality: assessing the differential effects of institutional distances on ownership strategy. J World Bus 51(4):600–611

Meleka HA (1985) The changing role of multinational corporations. Manag Int Rev 25(4):36–45

Morgan TA, Oppong D, Riverson R (2021) An Assessment of Opportunities and Challenges of Natural Gas Utilization in Ghana. In SPE Nigeria Annual International Conference and Exhibition (p. D031S018R004). https://doi.org/10.2118/207173-MS

Neal M (1994) The benefits of foreign direct investment in developing countries. Int J World Peace 11(2):15–34

Neal T, Losos E (2021) The environmental implications of China–Africa resource-financed infrastructure agreements: lessons learned from Ghana’s Sinohydro Agreement. Nicholas Institute for Energy, Environment and Sustainability, Duke University

Nunnenkamp P (2004) To what extent can foreign direct investment help achieve international development goals? www.worldbank.org/wbp/mission/up4.htm

O’Brien RM (2007) A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant 41(5):673–690

Obeng-Amponsah W, Owusu E (2023) Foreign direct investment, technological transfer, employment generation and economic growth: new evidence from Ghana. Int J Emerg Markets https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-02-2022-0200

OECD (2022) “Investment (GFCF)” (indicator). https://doi.org/10.1787/b6793677-en. Accessed 23 Apr 2022

Osei AE (2019) An assessment of the impact of foreign direct investment on employment: the case of Ghana’s economy. J Soc Sci Res 5(6):143–158

Sen A (1999) Development as freedom, 1st edn. Knopf

Tang D, Gyasi KB (2012) China–Africa foreign trade policies: the impact of China’s foreign direct investment (FDI) flow on employment of Ghana. Energy Procedia 16:553–557

Tang X (2018) 8 geese flying to Ghana? A case study of the impact of Chinese investments on Africa’s manufacturing sector. J Contemp China 27(114):924–941

Tee E, Larbi F, Johnson R (2017) The effect of foreign direct investment (FDI) on the Ghanaian economic growth. J Bus Econ Dev 2(5):240–246

U.N. (2002) International conference on financing for development: facilitator’s working paper. United Nations, New York. https://www.un.org/esa/ffd/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/BuildingMonterrey.pdf. Accessed 25 Nov

Vacaflores DE, Mogab J, Kishan R (2017) Does FDI really affect employment in host countries?: subsidiary level evidence. J Dev Areas 51(2):205–220. https://doi.org/10.1353/jda.2017.0040

Williams P, Frempong G, Akuffobea M, Onumah AJ (2017) Contributions of multinational enterprises to economic development in Ghana: a myth or reality? Int J Dev Sustain 6(12):2068–2081

Xia Y (2021) Chinese investment in East Africa: history, status, and impacts. J Chin Econ Bus Stud 19(4):269–293

Yankson PW, Asiedu AB, Owusu K, Urban F, Siciliano G (2018) The livelihood challenges of resettled communities of the Bui dam project in Ghana and the role of Chinese dam‐builders. Dev Policy Rev 36:O476–O494

Yeboah E, Anning L (2020) Investment in Ghana: an overview of FDI components and the impact on employment creation in the Ghanaian economy. Econ Manag Sustain 5(1):6–16

Yuan S (2023) The Health Silk Road: a double-edged sword? Assessing the implications of China’s health diplomacy. World 4(2):333–346

Yuan S (2023) Tracing China’s diplomatic transition to wolf warrior diplomacy and its implications. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:837

Yuan S (2023) Government legitimacy and international image: why variations occurred in China’s responses to COVID-19. J Contemp Eastern Asia 22(2):18–38. https://doi.org/10.17477/jcea.2023.22.2.018

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the research conception and design. The author, DA, confirms responsibility for the following: methodology, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results. The author, SY, confirms responsibility for the following: literature review and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Assamah, D., Yuan, S. Greenfield investment and job creation in Ghana: a sectorial analysis and geopolitical implications of Chinese investments. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 487 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02789-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02789-w