Abstract

This is a conceptual and methodological paper about improving our notion of human values. While it is recognized that talk of values has become increasingly popular in many walks of life, it is claimed that this is not underpinned by solid scientific contributions or a robust theory of values. Two initial claims set the scene for the paper: (1) there is no generally accepted theory of values, and (2) values are notoriously elusive. However, the paper acknowledges the problem that a better grasp on people’s values is needed for addressing the complex issues of our present-day life. An attempt is made to present an outline for an empirical axiology. After a brief historical overview of value discussions in social theory and philosophy, it is claimed that the empirical study of values needs to get around several hurdles: values-as-truisms, belief in articulated values, belief in deep and hidden values. However, combining several research methods may give first indications of what here is called value landscapes. A conceptual model of values in these landscapes would need to be multi-dimensional, with the tentative characteristics of proximity, intensity, contextuality, and malleability. The paper calls for transdisciplinary research designs to probe these conceptual insights.

Similar content being viewed by others

The problem: values in human agency

Talk about values is increasingly prominent both in various academic disciplines and in the political affairs of our life. In both contexts it emerges as an inherently complex matter, but with fundamental implications for what we think, what we do, and how we see the world around us. In fact, values are commonly regarded as building blocks of our identity (Joas 2000, p.164; Hitlin 2003). Despite their importance, there are (at least) two disturbing observations—here offered as hypotheses—about values: (1) there is no generally accepted theory of values, and (2) values are notoriously elusive. I will clarify both claims further down in the article. But first I note that there is even inherent ambiguity in what people mean when they talk about values. Values can acquire a deontic meaning as something that is right or wrong, what we ought to do and what not, or they can be understood as evaluative terms which rests on something being good or being bad. The former use is typical for normative discourse, e.g., in metaethics, while the latter is the reign of what has been termed axiology, the domain of the good.

Obviously, the topic of values can be approached from several angles and with several objectives in mind. However, this paper aims at the evaluative use of values (notwithstanding that there are clear crossovers to the deontic uses, e.g., in consequentialism). The reason for this is that values as evaluative terms have important policy implications (Scharfbillig et al. 2021) in the sense of good governance (Schulz et al. 2017, 2018), and that many of the empirical disciplines have that particular use in mind when they make values the subject of their research. Furthermore, many acknowledge that the evaluative “is part of the normative, where the normative is understood as concerning what we ought to do” (Brosch and Sander, 2015a, 7, italics in original). In this sense, this paper sketches a program in empirical axiology.

The term “axiology” normally signifies the study of values, or more concretely what is good or bad. This indicates a philosophical study but often also including other studies, normally from the social sciences but more recently even including neuroscientific studies (Brosch and Sander 2015b). With the term “empirical axiology” I want to signify a framework of axiological studies which is capable to be supported by and tested against relatively robust datasets about what values people actually hold.

While some authors have called for a “science of values” (Bahm 1993; Hartman 2011) I find this phrasing (at least when formulated in English) a bit too restrictive since it seems to indicate a strong reductionist view, mirroring and limiting the methods on those of the natural sciences. Thus, I prefer to speak about a “theory of values” and mean roughly a conceptual framework consisting of an ontology and possible relationships between these objects of the study. Sometimes this is also called a “model”Footnote 1. The relationship between these focal points of the framework and external objects of study, like e.g., motivations, preferences, norms, action, attitudes, is making up what in my earlier work I called the “phenomena” of the research (Kaiser 1991, 1995). A good theory of values should clarify how its phenomena can be linked to values and possible empirical data.

Hartman (2011) expresses this idea in a similar vein: “This conception presupposes that there are value phenomena, that they form an orderly pattern, and that this pattern can be mirrored in a theoretical structure, the theory of value or axiology” (ibid., 3–4).

While a satisfactory definition and full characterization of values in their evaluative use must be an endpoint of more empirical studies, for the purpose of this paper I present here a pragmatic working definition (adapted from the Value Isobars 2009; Meisch et al. 2011) as follows:

Values are reference points for evaluating something as positive or negative. Values are often rationally and emotionally binding and they give long-term orientation and motivation for action.

My first claim (1) is further elaborated in the following section on the historical development of the value concept. I should perhaps add up front that the claim about the lack of a value theory accepted across disciplines and by multiple research groups is not so original. Hartman (2011) complains that “value has not been made an object of orderly thinking” (ibid., 6), and even Schwartz (2016) acknowledges: “Despite the widespread use of values, many different conceptions of this construct have emerged … Application of the values construct in the social sciences has suffered, however, from the absence of an agreed-upon conception of basic values, of the content and structure of relations among these values, and of reliable empirical methods to measure them” (ibid., 63). I add a section where I criticize functionalist theories of values. This is then followed by a section on values in philosophical thinking which sketches some relevant philosophical discussions, but states also that value studies in philosophy have mainly focused on the deontic use.

Claim (2) is further specified in the section about studying values empirically and mapping value landscapes. It describes some recognized methodological hurdles which impede reliable data on the values that people ascribe to. Apart from the highly abstract level on which values seem to operate and which tends to immunize their study from counter evidence, I also discuss the claim that data via composite indicators add uncertainty upon uncertainty and rarely seem to provide robust empirical input to our theory.

In the final section before the conclusion, I explain my “model” or metaphor of a value landscape in greater detail and describe the characteristics of a multi-dimensional model of values. This then sets the scene for a recommendation to study values in a transdisciplinary mode.

Problem statement: while values are generally recognized as important drivers of attitudes and behavior, we lack the tools to adequately probe people and society about their values and what values are, in particularly about pressing issues in social life. The academic disciplines are divided in their handling and understanding of the issue, their theories are weakly supported by evidence, and the request by decision makers for providing evidence for robust policies is poorly served.

A historical sketch of the scholarly development of the concept of value

With regard to values, it makes sense to claim, on the one hand, that their theoretical import dates back to antiquity, and, on the other hand, that their entry into academic discourse is not older than sometime during the eighteenth to nineteenth century (Meisch and Potthast 2010).

In order to acknowledge the relationship of values to action and attitudes, it is useful to recall the classical philosophical view of explaining action on the basis of mental states (with possible origins from Aristotle and Augustin, but mainly developed through Leibniz and Kant; cf. Hilgard 1980): the analysis of human action is described as comprising three essential mental states: (1) the cognitive—what we know; (2) the affective—what we feel and long for; (3) the conative—what we aspire to, what we desire, what we value. There is a wealth of scholarly literature about (1) and (2), while (3) is much less represented in the literature.

Economic theory introduced the market as the platform for value transactions. The rise of economics through the work of Adam Smith and Karl Marx introduced a new notion of the market, as a multipotent sphere of relationships and interchanges between humans, based upon values—i.e., value transactions—and those were defined through work in both Smith and Marx (Spates 1983; Joas 2000). In economic theory it is expected utility which is the assumed ultimate arbiter (Gibbard 1986). We note that this approach is based on a one-dimensional transformation of values into a utility-measure.

However, this reductionism of values to economic utility has raised and still raises strong opposition in some quarters (Boudon 2001).

Emile Durkheim (through his analysis of rituals and collective effervescence) and later Max Weber (pro-social behavior as value-rational action; the essence of culture) discovered values as the glue in human societies (von Scheve 2016), though based on different outlooks. Durkheim assumed a “deterministic relationship between ‘social structures’ and moralities—certain moralities are ‘incompatible’ with certain social structures, and certain social structures ‘necessitate’ certain moralities” (Abend 2008, p. 99). Weber on the other hand, favored an internalist perspective on values as the sum of individual beliefs, with moral statements not among those being true as a part of the sciences, such that no evaluative quality is inherent in any action (Abend 2008). Friedrich Nietzsche called for a “Umwertung aller Werte” (Nietzsche 1887), and thus assumed a multiplicity of values, a call that fed into the wider popularization of the value concept.

Arguably it was Christian von Ehrenfels (1859–1932) who was among the first to publish a treaty to lay the foundations of a theory of values (“Allgemeine Werttheorie”; v. Ehrenfels 1897), based on the three mental states mentioned above. His theory accounts for differing intensity of values and states that the value of something is the degree of its desirability.

The rise of functionalism in value theory

In this section I want to address what is perhaps the major approach to values in social psychology and sociology, namely functionalist theories of values. In terms of scientific output and data collection this is certainly the dominating approach. One can find a more or less continuous development from early conceptions of the twentieth century to more recent theory constructions. Some conceptions and data, like in particular Schwartz’ studies, are informing important policy papers (Scharfbillig et al. 2021). While I will briefly summarize some of the most important ones, I shall present the latest addition in more detail, the theory of Gouveia et al. (2019). A criticism of these approaches is the topic in the section after this one.

The American sociologist Talcott Parsons was perhaps one of the most outspoken scholars who saw values as the major determinant in our understanding of society, stressing the important role of normative agreements in human affairs. His functionalist theory placed values, understood as moral beliefs, as the ultimate rationales for our actions (Spates 1983).

The nearly forgotten (and somewhat controversial) philosopher Eduard Spranger opened a new field, in particular for the new science of psychology, through his book Lebensformen (Spranger 1928), in which he presented six value-based attitudes to meet the problems of life. This in turn inspired Charles Morris who ended up with 13 ways to live, basically a role-specific prototype approach. Spranger and Morris (and also Allport) opened now the doors for more extensive empirical research on values. American social scientists and psychologists, inspired by philosophers such as Spangler, Morris and Dewey, foremost with Allport, Rokeach, Inglehart and Schwartz saw the opportunity to study values empirically, mostly quantitatively (Maio 2010).

The major innovation in large scale empirical approaches came with the social psychologist Milton Rokeach (1973) who introduced value research as a potent (American) alternative to the then dominant behaviorism in psychology. He named values, based on intuition, briefly explained their meaning, and asked people to rank them. With Rokeach, a distinction was introduced between instrumental values, and terminal or final values (Rokeach 1973; Rohan 2000). While this gave interesting results, it was not powerful enough to predict the probabilities for concrete preferences and actions. This was improved first by Ronald Inglehart (1977, 1990, 1997), and later by Shalom Schwartz’ (1992, 2016) value-theory. Both conceptions build upon the earlier work of Maslow and his conception of human needs (Boeree 1998). Where Inglehart operates with the basic opposition between materialism vs. post-materialism, later also traditional vs. secular-rational modes, Schwartz operates with self-transcendence vs. self-enhancement, and openness-to-change vs. conservation, which gives him nineteen value-spheres along these axes with currently 40 value-based properties or norms. Strong weight on one side of the axis implies lesser weight on the opposite side.

Inglehart’s approach may have some long-term predictive power about value change on the macro-level, while Schwartz’s theory exhibits more coherence as theory. However, both struggle with making connections to attitudes, preferences and actions (Datler et al. 2013). As Stavroula Tsirogianni states it: “In essence, the post-Rokeachean landscape of studies in values, assumed coherence, stability, homogeneity and universality in value structures, and ignored individuals’ capacity to boast a plural value system” (Tsirogianni 2010, 455).

Gouveia et al. (2014) and Gouveia (2019) propose to merge the functional theories of values as guide to action (like in Rokeach or Schwartz) with the functional theories of values as cognitive expressions of needs (like in Inglehart or Maslow). His 2 × 3 matrix (2 horizontal dimensions = thriving needs + survival needs, and 3 vertical dimensions = personal goals + central goals + social goals) results in six subfunctions (cells) where each is further specified by 3 marker-values. For instance, the crossing of social goals with survival needs gains as normative values: obedience, religiosity and tradition. Goveia hypothesizes that his 18 selected marker values are strong indicators of their correspondent basic values of people, a claim which he then finds confirmed in his survey study. While I think that the crossing of the different functions and the parsimonious outcome in terms of how many universal values to consider is a substantial progress in regard the previous theories he refers to, I am not yet convinced that this undoubtedly more sophisticated approach can avoid the more foundational criticisms of the inherent functionalism. Gouveia’s theory may be reflected in many remarkable statements as for instance: “It is value, then, that brings universes into being” (Graeber 2013, 231), since his overall theory “focuses on the functions human values fulfill” (Gouveia et al., 2014, 11) and is accordingly a functional theory: “the theory is the first to explicitly propose the functional interplay between the two dimensions [the dimension of representing personal versus social values and the dimension representing survival versus thriving values; my explanation]” (ibid., 12). It is this centrality of functionalism with which I disagree.

A philosophical criticism of functionalist value theories

Let me be more specific about functionalist value-theories here. My criticism of existing functional approaches to values is central for the alternative view of empirical axiology in the remainder of the paper. The following points aim at foundational issues in these functionalist approaches.

First, values as “guide” to action suffer from the tendency to collapse into the normative, deontic use of values, and are thus not necessarily identical to values that are actually held by people. Furthermore, it remains at least doubtful that values can be explanatory of concrete actions. Some social science literature has come to underline the importance of feelings, i.e., the emotive aspects, as possible explanations of actions (Elster 1999). To explain an action, one needs to look for the causal influence values can have as drivers/motivations to actions and some actions are triggered by something different than values (fear, envy, addiction, lust, etc.). Our tendency to rationalize our past actions does not justify the conclusion that we were actually guided by our values. In Gouveia’s table the category of social goals for action entails for instance the interactive value of Belonging as “regulating, establishing and maintaining one’s interpersonal relationships” (Gouveia et al. 2014, 43). I would hold against it that interpersonal relationships often are guided by other “valuations” as for instance differentiation, individuality or echo chambers. The functional approach to values as guide to action is thus missing out on the explanatory relation to people’s actions.

Second, values as cognitive expression of needs suffers from the same kind of criticism that Maslow’s hierarchy of needs was met with (cf. Neher 1991). While the purely physiological needs and perhaps even the safety needs could be granted a universal status, things become more contested and problematic when moving upwards into psychological and social needs. The higher one moves in the hierarchy the greater is the probability that different people choose different courses of action even under similar circumstances. These different courses of action signify a socio-cultural diversity in our web of meaningful representations of the surrounding world as for instance Serge Moscovici (1988) already pointed out for social psychology. The work of anthropologists underscores the socio-cultural diversity of values, as e.g., in the work of Graeber (2001, 2005, 2013). He stresses different value fields like homo economicus, homo hierarchicus, homo academicus etc (Graeber 2013, 229) as forming different universes where individuals are constantly moving back and forth. Values are here seen as different forms of constructing our actions to take on meaning which embraces a larger totality, a universe. My point is that the dominant functionalism in value theory (as cognitive expression of needs) ignores the degrees of freedom that cultural evolution brings about.

Spates (1983) identifies three fundamental problems in the sociology of values. First, there is the problem of empirical support. Spates claims that very few scholars actually attempt empirical studies to test their theories. One notable exception is Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck (1961) on value orientations, and a few others are concerned with particular selective cases. Second, there is the problem of deductive imposition. As Spates puts it: “subscribing to functionalist value theory, the researcher knows what to look for beforehand and imposes certain categories of response upon the empirical situation … Observable reality is forced into accord with a preconceived model. Thus, it is little wonder that functionalist research often finds ‘evidence’ for its concepts: such evidence is never given a chance not to appear” (Spates 1983, italics in original, p. 34). This is a consequence of my criticism of functionalist theories of values outlined above.

Third, there is the problem of abstraction. This issue concerns the immunization from falsification through increased abstraction. “With the distinction between values and norms …, values were said to be neither situation-specific nor function-specific. Ironically, their ‘power’ in shaping social life became even greater. Values were at the peak of the cultural ‘cybernetic hierarchy of control’; they ‘controlled’ norms, and norms ‘controlled behavior” (Spates 1983, p. 35). This is a methodological point which I want to expand on now.

One might object that all (or most) social science studies of theoretical constructs concerning people will operate with some kind of measurable indicators since the higher-level constructs are rarely if ever directly observable. For some phenomena there is widespread agreement what the useful indicators are. An example is the Human Development Index for which there are three individual indicators. But when the issue becomes more complex and the constructs more abstract, eventually leading to composite indicators based on other sets of (composite) indicators a lot of the specificity is lost, and the reliability of the measurement in relation to the reality of the construct suffers (Kaiser et al. 2021; Giampietro and Saltelli 2014). In the context of the study of human behavior and action I would hold that the study of social norms or the study of human cognition and beliefs is of lower complexity than the study of values. Values are typically the highest form of abstraction and consequently data about values are beset with significant uncertainties.

If one takes a closer look at the theory of planned behavior (TPB) which assumedly is one of the most influential current social science theories explaining human behavior based on beliefs, the above point of staggered indicators becomes apparent. TPB operates with three core components: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral controls which together determine intentions toward a type of behavior (Ajzen 2020). Attitude—to mention one of them—is again perceived as the sum of the product of composite belief indices and subjective evaluations. But there are also other dispositions such as personality traits and life values which enter as background factors. These are not part of the theory itself but recognized as potential causal influences. “With the aid of TPB it becomes possible to examine why a given background factor influences, or fails to influence, behavior by tracking its effects via the more proximal antecedents of the behavior” (Ajzen 2020, p.318). My point is that such theory spans open a highly complex field with multiple composite indicators which again might be correlated to background factors like values which then also are explored through such indicators. We might discover social norms through indicators for type of behavior or mechanisms of reward/punishment, but when it comes to values, they typically are on such a high level of abstraction that uncertainties in measurement tend to build upon other uncertainties. This does not in itself make more reliable data impossible, but it only shows that our theoretical construct of values needs to match the expected complexity that we might find in the data. Dynamic theory development and data acquisition will go hand in hand. This is a methodological point about levels of uncertainty and complexity in acquiring empirical data for a theory of values. I hold that the functionalist theories of value mentioned above do not reflect this complexity when they cite “supporting” evidence.

Thus, value theory and empirical value research did not experience a smooth ride in all these disciplines, in fact it almost disappeared in most of them. One reviewer of Rokeach wrote: “Few would dispute the statement that values play an important part in human behavior, … yet the concept of value has not been particularly useful despite the fact that a variety of social scientists … have attempted to make the concept relevant” (Gutek 1975; here quoted after Wuthnow 2008).

Values in philosophical thinking

In philosophy, the analytic and positivist turn side-lined ethics and studies of morality, and thus indirectly values, as these seemed not conducive to logical argumentation and to the strict methodology of the natural sciences (von Wright 1963). In the German speaking world, the so-called Werturteilsstreit, revived as Positivismusstreit primarily through the debate between Adorno and Popper in Tübingen in 1961, introduced a gulf between competing conceptions of society (Kaiser 2015). While both camps agreed that values enter in theory constructions of the scientists, they divided again when it came to the question of testability and basic analysis (totality vs. piecemeal problem solving). Despite elevating values to the conditions of research as such, both camps in fact lay dead the more concrete studies of the role of values in human mind, human action and in social interaction. In philosophical logic (as e.g., von Wright 1963), the stress lay on norms, conceived as directives, as they could be understood with deontic operators, while value judgements were seen as indefinite pro or con attitudes, lacking clear links to action, and even if granted a universal status, it would not follow that any of them ought to be achieved at all costs, given that other values might intervene. Thus, philosophical logic had no mind for values.

In current philosophy, except environmental ethics, the study of values per se is most probably a niche activity. It has some roots in social choice theory (stemming from Condorcet’s voting paradox, Kenneth Arrow’s impossibility theorem, and Sen’s capability approach), theory of taxonomy and the fitting-attitude-analysis of value (Rabinowicz and Rønnow-Rasmussen 2004, 2016). In principle, it is part of a theory of rational action which easily deviates into utility theory (and decision theory, game theory) as conceived in economics. The fitting-attitude-analysis of values accounts for values as something which is correctly desirable, thus including a deontic element in the specification of values. What is still remarkable is that—for the most part—philosophical analysis and conceptualization of values seems unaffected by purely descriptive aspects that the sociologists or the social psychologist have made their business to describe.

We note that philosophical discourse about values is mostly occupied with their deontic contexts. A good discussion of this is found in The Oxford Handbook of Value Theory (Hirose and Olson 2015). Here several theoretical challenges are analyzed in detail, as for instance the issue of monism versus pluralism of values. One important point to note in our context is that the pluralism of values is often aligned to claims of incommensurability. As Chang notes, incommensurability must be strictly distinguished from incomparability. The latter implies the former, but not vice versa. For an empirical axiological account of values, the incomparability is the more crucial aspect as it potentially affects accounts of rational action (Chang 2015).

The discussion about values was further advanced through the Handbook of Value (Brosch and Sander 2015a) which aimed at a more thorough but now interdisciplinary discussion of values, based on valuations implicit in our acts. As a matter of fact, in their contribution to the named Handbook, Brosch and Sander use the term which I have introduced earlier, “value landscapes”. They write:

“Valuation can thus be considered as the result of a ‘value field’ with different zones of attraction and repulsion that define the decision value of different choice options … Core value differences may thus represent differences in the shape of this force field, which determine the decision value of an option and allow accounting for individual differences in the decision value of one option. … The same behavior may be evaluated as neutral or even repulsive by another person with a different value landscape’” (Brosch and Sander 2015b, p. 401).

Given that already von Ehrenfels (1897) designed a theory of values based on the proportionality of the intensity of the desirability of values, one may wonder what progress we have made in the design of such a theory. I shall follow up this metaphor of a value landscape in the remainder of the paper.

Studying values empirically and mapping value landscapes

One problem for researching values is that peoples’ immediate responses to value inquiries may give us platitudes which have rhetorical appeal but no real motivational power. “Motherhood and Apple-Pie” as the English say, or “Friede, Freude, Eierkuchen” as the Germans say, sound very positive but are hardly revealing inner motivational structures. If values are perceived as truisms (Maio and Olson 1998; Bernard et al. 2003), then this has complicating consequences for research on them: how could they be powerful enough to motivate action and guide decisions? And how can they be truly descriptive of the complexity of peoples’ inner feelings and dilemmas in value-based choices?

Baruch Fischhoff (2000) commented upon the differences that exist among empirical value studies. He claimed that there are three basic and competing paradigms that inform this kind of research. He calls the first paradigm the philosophy of articulated values. This approach assumes that if there are clear and meaningful questions then subjects will have equally meaningful answers. The other extreme Fischhoff calls the paradigm of basic values. Now one assumes that people actually lack clear and articulated values for most areas of life. For the analyst this implies that the respondents have to decompose a question into a number of attributes that together might influence (be reasons for) the outcome of the respondents’ choice. Then one probably constructs a multi-attribute utility function that expresses all kinds of trade-offs. The third paradigm is basically an intermediate position, called partial perspectives. This view holds that people in general are not that badly informed about their own values that they need to start from scratch each time. But neither are all possible values necessarily well-articulated. People are assumed to have rather “stable values of moderate complexity, which provide an advanced starting point” (Fischhoff 2000, 622) to solve complex problems of the real world. Josselson (2004) argues that different perspectives may serve different functions, none truer than the others.

I take it from these discussions that the study of values needs to be reflective about what the objectives are for pursuing the study, and that we probably do best, if our data sampling is cognizant of the advantages and pitfalls of collecting data high and low.

The crux is, however, that we seemingly need this empirical input first in order to possibly construct a robust theory of values. As long as we are in the business of an empirical axiology, the exercise is not one of armchair philosophy. We need theory and data to mutually reinforce each other and to point the way to improve our understanding of a complex matter.

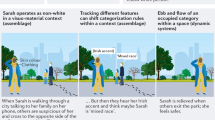

Can we get more insights into actually held values through some form of a grounded theory approach? In the project “Sustaining ethical aquaculture trade” (SEAT; cf. seatglobal.eu), I and the Bergen group was given the task of mapping Asian values in relation to aquaculture, in order to chart the ethical terrain between Asia and the European consumers. Our group designed a three-tiered empirical research method, which consisted of (1) a survey, (2) a number of qualitative interviews based on narratives and scenarios, and (3) a deliberative workshop to arrive at considered—and possibly consensual—judgments among the stakeholders. The results of the research were illuminating and noteworthy (cf. Bremer et al. 2012, 2013, 2014). One important finding was also that the ethical landscapes in the four countries under study differed significantly in their ranking of values. Despite our rather rough approach to values, interesting and relatively robust results emerged. Thus, one could clearly see cultural differences, often due to religious traditions. I refer to this as contextuality of scale and scope, implying that changing the scale and scope of the study might result in quite different rankings of values. Further down in the paper I will explain purpose contextuality in the study of values. See e.g., the comparison of individual personal values between Bangladesh and China in the SEAT project (Fig. 1).

The difference in value landscapes is coherent with the differences we found in the choice of preferred future scenarios, while the precise outcome of these preferences could admittedly not be predicted based on the values. Similar results have later been obtained by Mimi Lam who adopted a variant of our method of value mapping for the case of a herring fisheries conflict between the Haida and the federal government in Canada (Lam et al. 2019; Pitcher et al. 2017; Lam 2015). An interesting observation is that in her study the complexity scale was national, but the scope was divided into two different cultural systems, the indigenous culture of the Haida and the Western culture of the authorities and industry.

We conclude from this experience that careful and well-designed empirical studies of value landscapes can provide some useful input into constructing a more comprehensive and empirically adequate theory of values. However, we probably also foresee that we need to operate with more sophisticated models and concepts of values. This we will discuss in the remainder.

Value-landscapes—toward the construction of a value-theory?

One of the problematic assumptions in several approaches to the study of values is the claim that the list of all held values is finite and universal (Rokeach 1973; Schwartz 1992; Rohan 2000), while they may be held with different strengths in different cultures and countries. It is at least questionable if this could serve as a suitable starting point for constructing a theory of values. My contention is that this should be a hypothesis in need of empirical test and validation rather than a starting point. One should open for the possibility of non-universality of at least some actual values.

One cornerstone for constructing an empirical axiology should be value-pluralism. This implies that at least some values are not expressible through reduction to one overarching value. This would reject monism and limit the possibility of aggregating several values into just one. This assumption is coherent with most of the empirical studies on values so far (Tsirogianni and Gaskell 2011). Endorsing a value-pluralism seems to imply significant qualitative differences between pairs of values. As Chang (2015) argued, it need not imply a principal incomparability of the values. If we weigh different values against each other, we implicitly compare them in terms of relevance and intensity of bindings. Value-tradeoffs only make sense if we assume value-pluralism. However, in the abstract they may just be incommensurable. In the abstract it does not make much sense to apply firm measures to for instance the value of health, the value of welfare, the value of good food, and the value of listening to good music. But given a concrete context with a concrete choice to be made, then we might actually rank them according to how they fare for us in this specific context. For instance, if after more than a year of the pandemic and several lockdowns we have to decide whether to attend a public concert or rather remain careful and avoid possible infection, we may actually rank the value of health lower than the need to hear a good concert again.

This brings me to another cornerstone for a theory of values. The study of values needs to be sensitive to the context and they may take on different intensities in different contexts. This I call the contextuality of purpose, basically explaining why we want to elucidate the values of people in the first place. With a given and explicit purpose of our inquiry we hope to introduce sufficient context to the people so that they can easier identify their dominant values and give meaning to them. What people understand by abstract values like for instance human dignity can easily be different when discussing the future of their industry as compared to, say, security measures at airports. Adopting this viewpoint means choosing either Fischhoff’s second or third paradigm, while excluding or dampening the first. In other words, there might be too many fluctuations between values when contexts change for there to be a fixed expression of those values that count the most. However, once a context is specified then people might have a clearer conception of their values in this particular context.

There is supposedly a further constraint on value theory construction. While it seems convenient to label values with a term signifying it, it is not given that that term has a fixed meaning. Because of the purpose contextuality mentioned above, there may be ambiguity and different shadings of the term’s meaning. As an example, take a term like (personal) freedom. This has been much discussed during the pandemic, and some people have put forward claims of defending their personal freedom against state restrictions like wearing face masks or limiting the number of people allowed to party at home. Freedom is here understood as absence of state interventions in private behavior, including behavior in public spaces. However, such freedom has not been invoked in state interventions in e.g., regulating the traffic, and an obligation to drive on the right side of the road or stopping at a red light. This contextuality of meaning is also in line with the anthropological ideas of Graeber (2001, 2005, 2013) mentioned earlier.

I have taken a different road to constructing a theory of values. In an EU-funded project called The Landscape and Isobars of European Values in Relation to Science and New Technology (abbreviated as Value Isobars (2009)), I introduced the metaphor of a value landscape, combined with the idea of value isobars. Roughly, this was meant to imply that we have to deal with a variety of values which in principle can be arranged differently in relation to each other, and, furthermore, that one could identify areas of common pressure zones (like the isobars in meteorology) on these landscapes which in effect could promote or hinder certain innovations. One of the resulting insights of the project was that we still are missing a robust theory of values, and that the available data are too weak to allow for reliable predictions.

Value landscapes designate a novel view on value taxonomy and concept (Kaiser 2022). The philosopher Charles Taylor (1989) had earlier used the term Moral landscapes, as a metaphor for ordering and mapping the moral experiences and views of the self. The neuroscientist (and philosopher) Sam Harris has published a book with the title The Moral landscape (2010). Brosch and Sander (2015b) introduce the notion of value landscape as a field with hills and troughs representing various personal values, and providing “different zones of attraction and repulsion” (ibid, p.401) for different choice options. Schulz et al. (2017, 2018) used the term value landscapes as a conceptual framework to identify values on different levels of abstraction relevant for (water) governance. The general benefit of the metaphor of value landscapes is to capture the complexity and contextuality of actually held values from an inter- and transdisciplinary viewpoint for purposes of governance (as comprising polity, politics and policy).

Out of the earlier studies mentioned above, several insights emerged: (1) Values come to life in a given context and choice situation. Values-as-truisms are not dominant when a concrete context is given to people for the enquiry into their values. (2) When crossing cultural borders and inquiring about values, some values may crop up which do not usually enter the list of Western scholars. In our studies, for instance the value of political leadership was strongly voiced in some South-East Asian countries, while more or less absent in Western countries. (3) Value concepts do not easily translate into other cultures and languages, but when supplied with short narratives and preferably even artwork depicting the value, then ordinary people get more easily engaged in value discussions (including ethics). We were surprised about the enthusiasm with which even illiterate people participated in the discussions about values. (4) Values, or rather value landscapes, are not synchronized with ethical principles, and differences emerge between cultures without a direct relation to the value landscapes we managed to depict. While “problematic” principles (among Western governments) like Polluter-pays or the Precautionary principle were widely accepted in the Asian countries we studied, others which are supposed to be universal were not accepted, like the Equity principle, or Animal Welfare. Thus, values and (moral) principles are sometimes out of sync. (5) The relation between values and preferences, or decisions, or actions is at most vague, and while values—as conceived so far—typically serve justificationary roles, they are seldom predictive of actual behavior. To what extent values have a motivational function, directly or indirectly, remains unclear. (6) However, when addressing visions of future development, for instance in scenario workshops, values seem to serve an important function by, among others, weighting several options and arguing for or against them in dialogue. This bespeaks the role of values for governance.

With these experiences as background, and the current state of the relevant literature, there seem to emerge some cornerstones and research questions for the building of a future value-theory.

The metaphor of a value landscape is meant to convey the following complex of conceptual insights: (1) values relate to each other in terms of proximity; (2) different values may exhibit different intensity (defining peaks in the landscape); (3) each value acquires various meanings dependent on from where it is perceived (contextuality); and (4) values have an inertia but are malleable over time, particularly in interaction with belief states. In effect, values in value-landscapes are construed as multi-dimensional entities, highly dependent on context of use.

The first characteristic of intensity we find already in the conception of von Ehrenfels and later works, as for instance Inglehart or Schwartz. Values may trigger different affective states and be felt with different intensity. Sometimes they may also constitute reasons for action to a different degree. Dignity and respect toward myself and toward others in my community may be accompanied by strong feelings. Cultural roots may be responsible for that, or personal experiences. In many indigenous cultures respect apparently figures as the number one value (Lam et al. 2019), overriding autonomy. Thus, affective intensity may be another factor to determine different shades of my values.

Secondly, one has to break through the simple idea of the direct and one-dimensional representational character of value-terms. To assume that a given value, say privacy, retains the same characteristics and reference across various contexts of uses, does not seem promising. Instead, one would have to work-in multiple factors which together embrace the meaning of the term. One such factor could be context-dependent scope. Sometimes privacy may denote sheltering aspects of my life from just anybody, as is typically the case with diaries. Other times, it may shelter selected aspects of my life from specific users who may misuse this against my interests, as e.g., not making records of my health available to potential or actual employers, or when I resent making the contents of my luggage visible to co-travelers in a border control. This points us toward ambiguity and semantic indeterminacy. If one follows Quine’s Gavagai-argument (Quine 1960) this would imply a theoretical impossibility of translation between cultures since there is no single fact of the matter correlated to a term’s meaning—the empiricist heritage of Quine. Yet, in practical terms one may always get around this by working in contextual coherence, though this would not result in a unique scheme of translation. In our context here it suffices to observe that a given value term may not uniquely depict a specific meaning unless embedded in a specific context, and even then, this meaning may vary across various sub-contexts and the same individuals may fluctuate between them.

Thirdly, an additional factor could be shadings influenced by context-dependent neighborhood relations. For instance, privacy concerns are often contrasted to security concerns, as e.g., in security checks at airports, where many of us apparently let security concerns trump privacy. However, sometimes I may distrust the confidentiality of the party who receives my private information or suspect that other external motives are behind their look into confidential matters, e.g., commercial or political interests. Authoritarian regimes sometimes pretend security interests of their citizens when invading privacy. Chinese surveying technology in public spaces allegedly serves security interests of the populace, while many would assume that behind this objective lurks the state’s attempt of political control. Thus, (dis-)trust in beneficial intentions may override my security interests. This points us beyond mere context toward contrast with other relevant values and indeed other mental states (cognitive or affective) in these contexts, and this is what we above described as neighborhood sensitivity.

Fourthly, it is assumedly widely recognized that people’s values may change over time, both in individual and in socio-cultural history. What was described as equity or dignity in early constitutions of states has changed to the extent that the set of subjects falling under this juridical term has been extended, from men to including women, from white people to people of color etc. Similarly with animal welfare: it is just recently that people have realized the extent of animal’s capacity to experience pain, and the universe protected by animal welfare rules has been extended to include for instance fish and other vertebrates. This motivates us to conclude that personal values have a certain inertia and are resistant to short term experiences, but over time they too will change and adapt to a changing environment. Metaphorically this feature correlates to the slow changes in the landscapes around us.

What is the model/metaphor of a value landscape supposed to do then and how can this be the basis for a theory of values? A value theory should clarify what values actually do. It would build on the intimate relation between value as a noun and valuing as a verb. If values make a difference, then they should at least steer our valuing activities (Brosch and Sander 2015b). Furthermore, do values have some causal power for human action? If so, then one should expect that if x is such a value, then the removal of this value/should result in an observable difference in action. Some values may exhibit this feature in regard to some actions but not necessarily always. It would be the task of a good value theory to clarify the factors that make a difference. Such a theory should provide us with tools to specify cultural differences in our axiological basis and give indicators what emerges in regard dispositions toward certain actions and preferences. In particular, it should give us the empirical means to test whether all values are universal or not, or which of them are and which not. A prominent task of a theory of values should be to provide us with the means to evaluate and dialogue about possible futures for society. Ideals of deliberative democracy remain incomplete as long as we always end up in value-based conflicts without the means to explicitly address those values which separate us. In extension, it should provide us with the necessary link to ethical principles and attitudes so that we end up not necessarily in optimal negotiated choices of strategies for the futures, but in satisfying choices which obey the limits which ethical considerations may put upon us. We know by now that our current scientific and technological development is highly sensitive to ethical considerations. A theory of values should help us sorting out these considerations.

All this is still a far cry from a satisfactory theory of values. I envision a theory of values just as any other scientific theory which is open for empirical refutation. It would need a clear and concise conceptual framework, based on an ontology of values, and with a set of explicit relationships between them. Furthermore, it would need links to possible empirical validation or falsification, i.e., practical methods how to detect those values in humans, and avoiding the values-as-truisms fallacy. One objective would be to define a value-theory which potentially crosses different disciplinary boundaries, as I deem it incoherent when different disciplines operate with radically different value terms and value-theory. The notion of value-landscapes could remedy this, but proof of this needs to be forthcoming.

Solution statement: the academic community can assist policy making through developing inter- and transdisciplinary research, based on a new model of value theory which operates with a multi-dimensional dynamical concept of values, metaphorically guided by the picture of value-landscapes, and empirically underpinned by robust testing and empirically sound data.

Conclusion: research challenges ahead

This is a conceptual paper with the aim of hopefully pointing the way toward an empirical program of value research, based on a multi-dimensional concept of values, serving the socio-political objective of designing sustainable futures which people can recognize and embrace as an ethical way forward. Why do I think such a program would be relevant for policy? The relevance emerges from a quick informal look at recent European policy documents and discussions. For instance, Thiery Chopin and Macek (2018) state “The [European] Union is founded on a community of values set down in the treaties: the respect of human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and the respect of Human Rights” (ibid.), while it is acknowledged that it is still the Nation which is the primary frame of identification for most citizens. Brexit has shown that identification with Europe and its values is weakly entrenched among some people. Recent phenomena like the rise of populism and extremism, the rise of racism, opposition to immigration, and even some acts of roll-back on democratic liberties by member states (Hungary and Poland in particular) raise again the question how to approach the question of basic values and identities in forming our policies for the future, and more importantly, how to develop passionate adoption of these fundamental values among European citizens. I surmise that the question might not look very different from a North-American perspective. One may ask why this has not been done already, and why reviewing the current attempts at value theories seems to end up with a negative assessment of inability to serve this end. My answer is that this is mainly due to how we have structured our scientific enterprise. We work in disciplinary siloes, we seek quick academic merits, mostly in the form of publications, and we tend to oversell our mostly limited insights to advance our careers.

What we are not used to do is to seek out the dialogue with other disciplines (radical interdisciplinarity) and to adjust our research in a continued dialogue with users and the public at large (transdisciplinarity). However, while disciplinary work has still a lot going for it, the inherent complexity of our grand societal challenges demands to break through this straitjacket and address those “wicked” problems (Rittel and Webber 1974) in new ways. Therefore, the first challenge I foresee for a robust theory of values, fit for the purpose of designing sustainable futures, is a solid transdisciplinary research protocol (Kaiser and Gluckman 2023).

One would need to combine the insights from various sciences, including all social sciences, economy, philosophy and the humanities. One would also need to seek out specific contexts and the potential users to design partnerships for putting values to work, including alternative epistemic and value communities representing e.g., indigenous cultures.

We would then also have to work out a good model of personal and social values, along the characteristics of multi-dimensional value landscapes as described above. The links to social phenomena and possible empirical data need to be clarified, together with methodological guides how to get and interpret these data. The model itself needs to be critically tested, and if indicated changed. In the end, one would need to work on translating these insights into policy-relevant data and policy options in the light of people’s values.

All this may sound idealistic or futuristic given the current state of affairs, academically, socially and politically. But I would argue that we either take the current talk about our (European and other) values seriously and then work to underpin it with better research, or we abandon the talk about values as guides to our futures and resign with apathy, leaving values in the sphere of rhetorical instruments, powerless to inform and guide people’s actions and preferences. The latter would mean to give up a long tradition of understanding ourselves and our actions as based on the three basic mental states identified in the beginning. My plea is for trying to reform our research and our sciences before we give up our conception of the self.

Notes

For various reasons I do not call this framework a “paradigm” in the Kuhnian sense. Even though I claim to propose a novel approach, I do so as a constructive way to improve on previous research aiming at inter- and transdisciplinary research designs.

References

Abend G (2008) Two main problems in the sociology of morality. Theor Soc 37:87–125

Ajzen I (2020) The theory of planned behavior: frequently asked questions. Hum Behav Emerg Technol 2(4):314–324

Bahm AJ (1993) Axiology: the science of values, vol 2. Rodopi, Amsterdam, Atlanta, GA

Bernard MM, Maio GR, Olson JM (2003) Effects of introspection about reasons for values: extending research on values-as-truisms. Soc Cogn 21(1):1–25

Boeree CG (1998) Abraham Maslow. http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/maslow.html

Boudon R (ed) (2001) The origin of values: essays in the sociology and philosophy of beliefs. Transaction Publishers, Library of Congress, USA

Bremer S, Haugen AS, Kaiser M (2012) Mapping core values and ethical principles for livelihoods in Asia. In: Potthast T, Meisch S (eds) Climate change and sustainable development—ethical perspectives on land use and food production. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen, pp 419–424

Bremer S, Johansen J, Øyen S, Kaiser M, Haugen AS (2014) Mapping the ethical terrain of Chinese aquaculture. In: Brautaset C, Dent CM (eds) The great diversity: trajectories of Asian development. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen

Bremer S, Haugen AS, Kaiser M (2013) Whose sustainability counts? Engaging with debates on the sustainability of Bangladeshi shrimp? In: Röcklinsberg H, Sandin P (eds) The ethics of consumption: the citizen, the market and the law. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen

Brosch T, Sander D (eds) (2015a) Handbook of value: perspectives from economics, neuroscience, philosophy, psychology and sociology. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Brosch T, Sander D (2015b) From values to valueation: an interdisciplinary approach to the study of value. In: Brosch T, Sander D (eds) Handbook of value: perspectives from economics, neuroscience, philosophy, psychology and sociology. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Chang R (2015) Value incomparability and incommensurability. In: Hirose I, Olsson J (eds) The Oxford handbook of value theory. Oxford University Press, New York, Cambridge UK, p 205–224

Chopin T, Macek L (2018) In the face of the European Union’s political crisis: the vital cultural struggle over values. Fondation Robert Shuman The Research and Studies Centre on Europe, European Issue, 479

Datler G, Jagodzinski W, Schmidt P (2013) Two theories on the test bench: internal and external validity of the theories of Ronald Inglehart and Shalom Schwartz. Soc Sci Res 42:906–925

Ehrenfels C (1897) System der Werttheorie. 1. Band. O. R. Reisland, Leipzig

Elster J (1999) Alchemies of the mind: rationality and the emotions. Cambridge University Press, New York, Cambridge UK

Fischhoff B (2000) Value elicitation. Is there anything in there [w:] choice, values, and frames, red. D Kahneman, A Tversky, Russel Sage Foundation, Cambridge University Press, New York, Cambridge, UK

Giampietro M, Saltelli A (2014) Footprints to nowhere. Ecol Ind. 46:610–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2014.01.030

Gibbard A (1986) Risk and value. In: MacLean D (ed) Values at risk. Rowman & Allanheld, University of Michigan, p 94–112

Gouveia VV (2019) Human Values: Contributions from a Functional Perspective. In: Koller S (ed) Psychology in Brazil. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11336-0_5

Gouveia VV, Milfont TL, Guerra VM (2014) Functional theory of human values: testing its content and structure hypotheses. Pers Individ Differ 60:41–47

Graeber D (2001) Toward an anthropological theory of value: the false coin of our own dreams. Palgrave, New York & Houndmills, Bassingstoke, Hampshire, England

Graeber D (2005) Value: anthropological theories of value. In: Carrier JG (ed) A Handbook of Economic Anthropology. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK, Northampton, Mass, USA, p 439–454

Graeber D (2013) It is value that brings universes into being. HAU J Ethnogr Theory 3:219–243

Gutek BA (1975) Review of the nature of human values. Am J Sociol 81:443–444

Hartman RS (2011) The structure of value: foundations of scientific axiology. Wipf and Stock Publishers, Eugene, Oregon

Hilgard ER (1980) The trilogy of mind: cognition, affection, and conation. J Hist Behav Sci 16(2):107–117

Hitlin S (2003) Values at the core of personal identity: drawing links between two theories of Self. Soc Psychol Q 66:118–137

Hirose I, Olson J (eds) (2015) The Oxford handbook of value theory. Oxford University Press, New York & Cambridge UK

Inglehart R (1977) The silent revolution. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Inglehart R (1990) Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Inglehart R (1997) Modernization and post-modernization. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Joas H (2000) The genesis of values. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Josselson R (2004) The hermeneutics of faith and the hermeneutics of suspicion. Narrat Inq 14(1):1–28

Kaiser M (1991) From rocks to graphs—the shaping of phenomena. Synthese 89(1991):111–133

Kaiser M (1995) The independence of scientific phenomena. In: Herfel W, et al. (eds.) Theories and models in scientific processes. Amsterdam, Atlanta, pp 179–200

Kaiser M (2015) Werte, werturteile, und post-normale Wissenschaft. In: Quinn RA, Potthast T (Hrsg) Ethik in den Wissenschaften, Internationales Zentrum für Ethik in den Wissenschaften (IZEW), Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, pp 367–374

Kaiser M, Chen ATY, Gluckman P (2021) Should policy makers trust composite indices? A commentary on the pitfalls of inappropriate indices for policy formation. Health Res Policy Syst 19:40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00702-4

Kaiser M (2022) Taking value-landscapes seriously. In: Bruce D, Bruce A (eds.) Transforming food systems: ethics, innovation and responsibility. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen, pp 46–51. https://doi.org/10.3920/978-90-8686-939-8_5

Kaiser M, Gluckman P (2023) Looking at the future of transdisciplinary research. International Science Council. https://doi.org/10.24948/2023.05

Kluckhohn FR, Strodtbeck FL (1961) Variations in value orientations. Row, Peterson, Evanston, IL

Lam ME, Pitcher TJ, Surma S, Scott J, Kaiser M, White AS, Pakhomov EA, Ward LM (2019) Value-and ecosystem-based management approach: the Pacific herring fishery conflict. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 617:341–364

Lam ME (2015) Herring fishery needs integrated management plan. Op-Ed, The Vancouver Sun, November 9

Maio GR (2010) Mental representations of social values. In: Zanna MP (ed) Advances in experimental social psychology, vol. 42. Academic Press, Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales, UK, p 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(10)42001-8

Maio GR, Olson JM (1998) Values as truisms: evidence and implications. J Pers Soc Psychol 74(2):294–311

Meisch S, Potthast T (2010) Values in Society EC Project: the landscape and isobars of European values in relation to science and technology. Eberhard-Karls Unviersität, Tübingen

Meisch S, Beck R, Potthast T (2011) Towards a pragmatically justified theory of values for governance. Conceptual analysis of values, norms, preferences and attitudes. EU-Project Value Isobars, 436

Moscovici S (1988) Notes towards a description of social representations. Eur J Soc Psychol 18(3):211–250

Neher A (1991) Maslow’s theory of motivation: a critique. J Humanist Psychol 31(3):89–112

Nietzsche F (1887; 2018) Zur Genealogie der Moral: Eine Streitschrift (Classic Reprint), Forgotten Books, London, England, UK

Pitcher TJ, Lam ME, Kaiser M, White A(S-J), Pakhomov E (2017) Hard of herring. In: Tortell P, Young M, Nemetz P (eds.) Reflections of Canada: illuminating our opportunities and challenges at 150+ years. Peter Wall Institute of Advanced Studies, Vancouver, Canada, pp 112–119

Quine WVO (1960) Word and object. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, p 147

Rabinowicz W, Rønnow-Rasmussen T (2004) The strike of the demon: on fitting pro-attitudes and value. Ethics 114:391–423

Rabinowicz W, Rønnow-Rasmussen T (2016) Value taxonomy. In: Brosch T, Sander D (eds) Handbook of value: perspectives from economics, neuroscience, philosophy, psychology and sociology. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Rittel HW, Webber MM (1974) Wicked problems. Man-made Futures 26(1):272–280

Rohan MJ (2000) A rose by any name? The values construct. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 4:255–277

Rokeach M (1973) The nature of human values. Free Press, New York

Scharfbillig M, Smillie L, Mair D, Sienkiewicz M, Keimer J, dos Santos RP, Scheunemann L (2021) Values and identities—a policymaker’s guide. EUR 30800 EN. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Schulz C, Martin-Ortega J, Glenk K, Ioris AA (2017) The value base of water governance: a multi-disciplinary perspective. Ecol Econ 131:241–249

Schulz C, Martin-Ortega J, Glenk K (2018) Value landscapes and their impact on public water policy preferences. Glob Environ Change 53:209–224

Schwartz SH (1992), Universals in the content and structure of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In: Zanna M (ed) Advances in experimental social psychology, vol 25. Academic Press, New York

Schwartz S (2016) Basic individual values: sources and consequences. In: Brosch T, Sander D (eds) Handbook of value: perspectives from economics, neuroscience, philosophy, psychology and sociology. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Spates JL (1983) The sociology of values. Ann Rev Sociol 9:27–49

Spranger E (1928) Types of men: the psychology and ethics of pesonality. Hafner Pub. Co, (German original: Lebensformen) New York

Taylor C (1989) Sources of the self: the making of the modern identity. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Tsirogianni S (2010) Values in context: a study of the European Knowledge Society. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, Institute of Social Psychology, London School of Economics, London

Tsirogianni S, Gaskell G (2011) The role of plurality and context in social values. J Theory Soc Behav 41:441–465

Value Isobars (2009) EU funded project nr. 230557. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/230557/reporting

von Scheve C (2016) Societal origins of values and evaluative feelings. In: Brosch T, Sanders D (eds) Handbook of value: perspectives from economics, neuroscience, philosophy, psychology and sociology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 175–195

von Wright GH (1963) Norm and action: a logical enquiry. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London

Wuthnow R (2008) The sociological study of values. Sociol Forum 23:333–343

Acknowledgements

The author wants to thank Mimi Lam, Maureen Junker-Kenny, Margit Sutrop, Thomas Potthast, Christian Wittrock, and Sir Peter Gluckman for helpful discussions and comments on an earlier version.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Bergen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The corresponding author is sole author of the paper and conceived the basic ideas of the paper, produced the manuscript in all its versions, and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

No ethical assessment or permissions were required for the writing of the paper. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaiser, M. The idea of a theory of values and the metaphor of value-landscapes. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 268 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02749-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02749-4