Abstract

Film-induced tourism is considered a valuable marketing tool, especially crucial for the recovery of post-pandemic tourism. The rapid growth of digital streaming platforms has enabled film and television works to reach global audiences and impact viewers on a broader scale. Scholars and tourism operators increasingly recognise film characters’ pivotal role in global film-induced tourism. While film-induced tourism is generally believed to impact the image of tourist destinations positively, existing research has predominantly focused on the decent characters portrayed in films. However, the allure of captivating audiences is not confined solely to decent characters. According to narrative studies in film and television, villainous characters with extraordinary skills often have a stronger appeal to viewers than decent ones. Therefore, the objective of this study is to explore a rarely discussed topic: how villainous characters enhance the attractiveness of tourist destinations. This interdisciplinary research principally integrates character arc theory and reception aesthetics from film studies, emotion contagion theory from marketing research, and place attachment theory from tourism studies. Accordingly, this study examines the perceived charismatic leadership of villainous characters and its impact on film tourists’ emotion contagion, place attachment and visit intention. The study distributed questionnaires to 532 audiences who watched the Chinese police and crime drama titled, The Knockdown (狂飙), and who acquainted themselves with the villainous character Gao Qiqiang (高启强). Structured equation modelling showed that villainous characters with charismatic leadership can significantly impact the intention of film tourists. Specifically, perceived charismatic leadership directly influenced emotions of pleasure, arousal and admiration. Place attachment existed as a whole or partial mediator of the three emotions and visit intention. Moreover, the audience’s justice sensitivity negatively moderated the positive relationship between perceived charismatic leadership and emotions. Finally, the study provides insights and suggestions for film tourism marketers and screenwriters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For post-epidemic tourism recovery, tourism marketing has long recognised the value of film tourism as the latter is essentially a potential niche market that has been perceived to be more resilient than any other types of tourism during a crisis (Avraham 2021; Sousa et al. 2021). Due to the rapid development of digital streaming platforms, temporal and spatial constraints of traditional screened media comsumption are shattered, globalising the influence of film and TV content (Martínez-Sánchez et al. 2021). Consequently, film stories and characters have become vital in global tourism marketing. Rather than merely increasing destination exposure, films can engage the viewer in a deeper emotional connection with the location by empathising with the storyline and characters (Oshriyeh and Capriello 2022). Film characters can be utilised as tourist attractions, destination mascots and celebrity endorsements (Teng and Chen, 2020; Xu et al. 2022; Florido-Benítez 2023; Zhou et al. 2023). This series of studies on mascots and celebrity-related theories focuses primarily on decent characters, such as super cute cartoons, doctors, soldiers, superheroes and saviours (Kim 2011; Yen and Croy 2013; Kim and Kim 2017; Xu et al. 2022; Florido-Benítez 2023). The success rate of decent characters in promoting film tourism is expected to be higher, whereas villain characters are viewed with scepticism (Pratt 2015). Although many tourist destinations have interestingly become popular because of villainous characters, such as gangsters in the film Monga (2009), Count Orlok in the film Nosferatu (1922) in real-life scenarios (Chen and Mele 2017; Liu et al. 2020), discussion scarcely focuses on how villainous characters enhance the appeal of tourism destinations, which is the main objective of this study.

Emotional contagion is a unique experience for the audience of audiovisual narratives and a critical conversion process from being stimulated by film characters to generating an intention to travel to a destination (Coplan 2011; Podoshen 2013; Wu and Lai 2021). Psychology, film and media studies constitute vital sources of research pertaining to emotional contagion, often intertwined with marketing and consumer research to create a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon (Podoshen, 2013). Considering destination marketers’ limited control over film location portrayals, tourism operators must grasp how different film genres affect tourists’ emotional responses (Tasci 2009; Florido-Benítez 2023). Hence, exploring the specific factors that prompt emotional contagion among the audience towards villainous characters is essential.

Character arc theory proposed by McKee (1997) suggested that charismatic antagonists possess a high level of intelligence, charm and emotional depth, bringing them up to par with the protagonists (Lyons 2021). The perceived charismatic leadership of celebrities can produce emotional contagion, but whether film villains can create the same emotional contagion has not been empirically verified (Cherulnik et al. 2001; Lee and Theokary 2021). Aesthetic reception theory also emphasises that personal experience will affect their aesthetic judgement and interpretation of film images (Jauss and Benzinger 1970); whether justice sensitivity will influence the emotion towards evil characters remains unknown. Moreover, although recent tourism research has identified the development of place attachment and behavioural intentions as a result of emotional contagion and has cautioned that different emotions have distinct effects on place attachment and behavioural intentions (Ratcliffe and Korpela 2017; Xu and Tan 2019), current researches have not directly measured the different emotions that viewers feel towards a character and compare the effects of different emotions on psychological and behavioural responses.

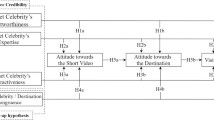

Addressing the identified research gaps and based on emotional contagion theory and the stimuli-organism-response (SOR) model, this study has the following primary purposes: (a) to determine how perceived charismatic leadership of a villainous character, as a stimulus to the audience, influences emotions; (b) to examine whether justice sensitivity moderates the positive emotions generated by perceived charismatic leadership towards a villainous character; (c) compare the differences in the impact of different emotions generated by the perception of charismatic leadership on place attachment (as a psychological response) and visit intention (as a behavioural response); (d) to provide valuable recommendations for film tourism stakeholders, including filmmakers, destination operators and tourism marketers.

Literature review

Film-induced tourism and digital streaming platforms

Film-induced tourism refers to visiting a destination or attraction prompted after viewing films which cover movies, TV dramas and other forms of screened media (Connell 2012; Yen and Croy 2013). The appeal of film-induced tourism primarily lies in its ability to enhance the image and value of destinations. Films serve as the cornerstone of film tourism marketing, conveying tourist destinations’ emotional elements and values (Florido-Benítez 2022). Films establish themselves as icons of tourist destinations, affirming the feasibility and practicality of film tourism (Nakayama, 2022). Nevertheless, film-induced tourism faces particular challenges in becoming the perfect marketing tool for the tourism industry. Research based on the push-pull theory suggested that film-induced tourism often occurred as a serendipitous event, with the impact of film-induced motivation factors being relatively low compared to other factors (Chemli et al. 2022). Furthermore, studies indicate that serendipitous tourists make up the majority of film tourism, possibly due to the limited penetration of films and TV dramas in some regions, as their distribution remains restricted (Ng and Chan 2019).

With the rapid development of digital streaming platforms, the constraints on disseminating films and TV dramas have gradually been overcome. Mainly influenced by the pandemic, which compelled audiences to spend more time at home, consuming music, films, TV shows, and various forms of entertainment through digital means, this has propelled the flourishing of streaming and online services (Jelinčić 2022). As the consumption patterns of television shift, digital streaming platforms have seen an increasing penetration among audiences. These platforms have incorporated social media into their strategies for attracting new users to enhance their competitiveness (Martínez-Sánchez et al. 2021). This strategy has not only strengthened the impact of films and TV dramas on social media but has also led film tourism-related research to focus more on film characters and story elements that are easily disseminated through social media. Xu et al. (2022) suggested that selecting film characters with local cultural significance as mascots for tourist destinations can contribute to reviving the tourism industry in the post-pandemic era. Tourists sharing photos related to film tourism on social media are often linked to narrative plots and interactions with film characters (Gómez-Morales et al. 2022). Puche-Ruiz (2022) emphasised that humorous and extravagant narrative techniques, along with highlighting the mythical, unpredictable, and irrational features of destinations through characters, play a crucial role in shaping tourists’ perception of the formal aspects of the destination’s culture. Augmented Reality (AR) features in film character-related tourism apps can be integrated into destination marketing strategies since fans can share AR images of their favourite stars on social media, establishing connections with potential film tourists (Wu and Lai 2021). Therefore, a deeper understanding of how screened media’s plots and character traits influence film tourists becomes increasingly essential in the current digital streaming platform development landscape.

Perceived charismatic leadership

Charismatic leadership is a concept initially defined within the discipline of organisational behaviour. The current research explored the notion of charismatic leadership from two distinct angles. An important characteristic of charismatic leadership is followers’ perception that their leader has extraordinary qualities, highlighting their emotional attachment to the leader (Weber 1947; Shamir et al. 1993). Conger (1989) believed that charismatic leadership is characterised by self-confidence, strong vision and the ability to articulate a compelling message, highlighting the exceptional qualities and abilities that can inspire and motivate followers. Specifically, these extraordinary capacities include strategic vision and articulation, the ability to take personal risk, sensitivity to the environment, sensitivity to member needs and unconventional behaviour (Conger and Kanungo 1994). In this study, perceived charismatic leadership refers to the audience’s perception coming from the extraordinary leadership ability of a character in a fictional story.

Interestingly, current research on film and TV drama narratives has highlighted that charismatic leadership theory has become an essential theory of character creation in films both for fictional heroes and villainous characters (Warner and Riggio 2012). Rosser (2016) revealed Harry Potter’s charismatic style as reflected in the main character, which demonstrates the effective management of leadership abilities that guide others through the application of virtuous values; particularly in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2000), several film scenes reveal the role of leadership theory in film narratives and serve as the epitome of leadership theory. Leaders must have a good sense of narrative and storytelling to develop their charismatic image (Sharma and Grant 2011). Gordon Gekko claimed that ‘greed is good’, reflecting that he is an iconic example of charismatic leadership in the movie Wall Street (1987); he represents both a morally flawed character and a classic portrayal of ambition gone awry (Gini and Green 2013). The reason villains in films are often also charismatic leaders is inextricably linked to the use of character arcs in film narratives. Character arcs are characters’ transformations or inner journeys throughout a story and are the secret to creating charismatic avatars (McKee 1997). McKee (1997) served Shakespeare’s Macbeth as an example and suggested that in screenwriting, a well-rounded and multidimensional charismatic antagonist must have a high level of intelligence, charm and emotional depth, making them on par with the protagonist. The Godfather trilogy (1972–1990) is Coppola’s most lasting contribution to cinematic exploration of charismatic leadership, and it shows gangsters in a more noble light than most films do; leadership stereotypes were brilliantly challenged by Corleone (Warner and Riggio 2012). The main character, Joker, in his display of power underscores the unethical charismatic leadership affecting followers in the movie Batman: The Dark Knight (2008) and the bureaucratic authority granting leaders legitimate power (Edwards et al. 2015). The characters of Walter White from Breaking Bad (2008–2013) and Jimmy McGill from Better Call Saul (2015–2022) have shattered the conventional line between hero and villain, yielding to a new era of compromised protagonists and charismatic anti-heroes (Lyons 2021). Fictional characters’ charismatic leadership has profoundly contributed to the dramatic appeal.

Through these dramas and films as an attractive medium, many studies have also found that individuals’ perceptions of charismatic leadership from fictional characters can affect personal behaviour in reality. A character’s charismatic leadership could be the impact of media portrayals on viewers’ expectations, the reinforcement of social and cultural norms and the potential for leadership lessons to be derived from fictional narratives (Long 2017; Kuri and Kaufman 2020). The public’s fascination with the images and behaviours of highly appealing film characters can be extended to the physical environments in which these characters appear (Allen, 2009). However, discussions on how audience perceptions of characters’ charismatic leadership influence character-related consumption behaviour have been scant. For film-tourism research, despite real examples of gangster characters driving tourism (Chen and Mele, 2017), whether tourists’ pilgrimage is caused by perceived charismatic leadership remains empirically unproven. Thus, this study fills a gap in marketing and tourism research.

Emotion contagion theory

Emotion contagion theory (ECT) is a psychological concept that describes the spread of emotions between individuals. It involves mimicking and synchronising expressions, vocalisations, postures, and movements, resulting in shared emotional experiences (Hatfield et al. 1993). Emotional contagion is believed to occur when the subconscious and automatic transfer of emotions takes place between people, according to the instinctive, primitive contagion approach (Barsade 2002). Thus, symptoms of emotional contagion include the uncontrollable spread of feelings without the individual being aware of them. Emotional contagion is not only a process of emotion transmission but also a process in which individuals or groups influence others’ attitudes or behaviour by inducing emotional states (Schoenewolf 1990; Du et al. 2010).

Initial studies on emotional contagion focused on face-to-face interactions. However, modern mass media, including film, newspaper, radio, television, and social media, can spread emotions across large audiences, transcending geographical boundaries. Döveling et al. (2010) emphasised that contemporary mass media has an even greater influence than it has been commonly perceived owing to their potential to trigger the dissemination of not only information but also emotions. Emotional contagion is particularly common during film and TV viewing, offering a unique experience of audio-visual narrative to audiences (Coplan 2011). Coplan (2006) posits that emotional contagion occurs during film viewing as it does in real life, which results from direct sensory engagement and reflective feedback.

Characters are undoubtedly a crucial element of a film experience, as the viewer is ‘infected’ by the mood or emotion of the characters (Eder 2010). As a result, the study of film-induced tourism has underlined the importance of characters in film, TV drama and other forms of screened media. Research on film-induced tourism identified that emotional contagion, which often originates in movie characters, is a major influence on tourists’ behaviour (Podoshen 2013; Wu and Lai 2021). An empathic connection to the storyline and characters of films can enhance the connection between the viewer and the location (Oshriyeh and Capriello 2022). Famous characters attract tourists to film theme parks and provide a fantasy experience to interact with cartoon or fictional characters (Florido-Benítez 2023). Specifically, tourists share more images on social media of locations that have more exposure time on screen, that contain more crucial squences to plot structure, and that have more closely interactions between the characters and the scenarios (Gómez-Morales et al. 2022). Existing research validates that numerous characteristics of a character can be a motivation for film tourists, including nostalgia, romanticism, cuteness, fantasy, distinctive makeup, unique costumes and cultural meanings (Podoshen 2013; Ng and Chan 2019; Xu et al. 2022). However, attention has rarely examined the character’s personality traits related to the storyline. Moreover, the personality traits of the villain character that can influence emotional contagion remain unknown. Whereas in the real world, celebrities can create emotional contagion by demonstrating charismatic leadership on social media or television (Cherulnik et al. 2001; Lee and Theokary 2021), the effectiveness of a character’s charismatic leadership on the audience still needs verification in the fictional world of cinema. This study fills these gaps by exploring the effect of perceived charismatic leadership on emotional contagion derived from fictional characters.

Pleasure emotion, arousal emotion and admiration emotion

Emotions refer to feelings experienced and expressed, accompanied by physical solid reactions (Grindstaff and Murray 2015). The film character’s linguistic and nonverbal expressions of emotion are the most crucial source of triggering the audience’s emotions (Feng and O’Halloran 2013). In this study, emotions refer to audiences’ different personal reactions when they see a film or watch television. According to Bartsch (2012), emotion is considered the core of media entertainment such as films, novels, television, videos and computer games; people’s emotional investment in film and TV characters is related to the role of emotion in satisfying social and cognitive needs. In the framework of the SOR model, emotion, as an organism, contributes to consumers’ willingness to purchase online and tourists’ intention to visit a destination (Thomas and Mathew 2018; Li et al. 2022). In several different studies, pleasure, arousal and admiration were confirmed to influence audiences’ willingness or behaviour to participate in film tourism (Im and Chon 2008; Yen and Croy 2013; Di-Clemente et al. 2022). Therefore, this research categorises emotion into pleasure, arousal and admiration emotions.

Pleasure is a feeling of contentment, happiness or fulfilment (Perea y Monsuwé et al. 2004). In the context of this study, pleasure emotion can be defined as sensations of happiness, satisfaction, relaxation and joy that audiences experience when they see a film or watch television. In the film The Lion King (1994), the main character, Simba, who has charismatic leadership, wins the hearts of the audiences and creates pleasure in them (Reiner 2009). In the romance series film The Twilight Saga (2008–2012), when female audiences see the film’s male characters, Edward and Jacob, who have different leadership styles, they substitute themselves with the female character Bella, creating a sense of pleasure and satisfaction (Taylor 2012). In the film Henry V (1989), Henry is a morally flawed charismatic leader with an inspirational style and charismatic personality; not only did he bring positive emotional value, but he also promised glory to his followers (Warner 2007). Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H1: Perceived charismatic leadership positively influences pleasure emotion.

Arousal is the feeling of excitement, surprise, stimulation, activity or alertness (Floyd 1997; Perea y Monsuwé et al. 2004) and refers to the intensity of emotions (Pastor et al. 2007). In this study, arousal emotion refers to the various, more intense physical and emotional reactions evoked in audiences when watching a film or television. In art psychology, complex, novel, uncertain or conflicting stimuli have been shown to heighten the arousal emotion (Silvia 2005). Katniss Everdeen, the heroine of The Hunger Games trilogy (2008–2010), has impressed audiences with the thrills, violence and hardships she has endured on her journey to adulthood and has evoked a wide range of emotions (Irwin 2012). One of the defining trends of the contemporary golden era of TV fiction has been the popularity of antiheroes as protagonists; the antihero has become the critical element of drama conflict, bringing contradiction and emotion into the story (Gernsbacher et al. 1992). As a film’s success is primarily determined by its ability to evoke moral emotions in viewers, cultivating attitudes of sympathy and antipathy towards its various characters is necessary (Carroll 2010). Villains with charismatic leadership in the film Bonnie and Clyde (1967) evoke a fresh emotional reaction in gangster films; in essence, it uses aesthetic values to obscure moral values and then reveal the latent moral values with great force. Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H2: Perceived charismatic leadership positively influences arousal emotion.

Admiration is a kind of positive emotion that relates to the ability of people to perform rare and difficult feats with skills (Algoe and Haidt 2009). When people see extraordinary abilities in others, they develop feelings of admiration (Immordino-Yang et al. 2009). In the context of the film as a marketing tool, the success of film-induced tourism derives from the audience’s admiration for film celebrities (Zeng et al. 2023). Admiration elicited by film characters can come not only from heroes but also from villains. Many studies show that admiration appears in villainous characters because these characters have superior qualities, which usually give the audience a sense of honour and empathy, among others (Eaton 2010; Kjeldgaard-Christiansen et al. 2021). According to Wei (2023), the film’s aesthetic treatment of form, style and content can fascinate audiences with the amoral qualities of an evil character and generate admiration. Villainous characters with charismatic, positive qualities are more likely to inspire admiration from the audience (Moss 2014). Admiration is the important emotional outcome of charismatic leadership (Sy et al. 2018). However, both villainous and heroic leadership can lead to admiration due to the blindness that often goes along with such admiration (DeCelles and Pfarrer 2004). Daenerys Targaryen in Game of Thrones (2011–2019) is a fictional character with charismatic leadership; her image reflects danger and power, leading audiences’ admiration towards her (Khalifa-Gueta 2022). Having a particular type of moral flaw can remarkably enhance the aesthetic value of a work. As charismatic villain in The Soprano (1999–2007), Tony Soprano has attracted a global audience in admiration of his fictional character, which made people recognise the dangerous appeal of charismatic leaders (Eaton, 2012). Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H3: Perceived charismatic leadership positively influences admiration emotion.

Place attachment

Place attachment, initially defined as an emotional bond with an environment providing comfort and safety, leads to the formation of emotions and personal behaviour (Kyle et al. 2004). It signifies the emotional connection between a tourist and a destination (Krolikowska et al. 2019; Zhou et al. 2023) and is linked to positive emotions and behavioural intentions resulting from one’s interaction with the environment (Hosany et al. 2019; Abbasi et al. 2022). Due to its abstract nature, place attachment is often discussed in two sub-dimensions: place dependence, reflecting a functional attachment, and place identity, representing a symbolic or emotional attachment (Williams and Vaske 2003; Halpenny 2010; Vada et al. 2019).

Owing to media exposure, tourists tend to form place attachments before visiting a particular location. Film-induced tourism research concluded that the symbolic meanings embedded in films can be transformed into an attachment to the places featured in a particular medium (Kim 2010; Hosany et al. 2019). When people are inspired to visit a destination or attraction after seeing being depicted in movies or dramas, their attachment to the place serves as a connection between that motivation and their actual visitation behaviour (Chen 2017; Zhou et al. 2023). Film characters are found crucial to film tourism as they not only create a sense of place and authenticity in the destination but also create varying degrees of emotional attachment in the viewer (Lindsay 2009; Yen and Croy 2013). Transfer theory confirmed that emotional attachment to places depicted in a film, particularly those associated with an attractive fictional character, can create a sense of place attachment (Hosany et al. 2019). In many studies based on the SOR model, place attachment is considered a positive psychological response acting as an ‘R’ in the model (Zhu and Chiou 2022). Existing studies have found that different emotions vaguely affect place attachment, and the result can be influenced by the context of the study (Gross and Brown 2008; Ratcliffe and Korpela 2017). The impact of various emotions linked to film-induced tourism on each aspect of place attachment is not thoroughly explored. Therefore, the present study fills the gap in this area.

Pleasure-seeking is an important tourism push factor relevant to emotional needs and influences choice behaviour (Goossens 2000). Marketing tool commonly provides pleasure anticipation to attract travellers to the destination. In the study of virtual tours, an individual’s pleasure emotion was confirmed to positively affect place attachment on its two sub-dimensions, even if they had not visited the locale (Wirth et al. 2012). Consequently, if a film or TV drama audience develops pleasure emotions towards a certain character and storyline, the probability of developing place attachment to relevant locations is also quite high. Given this consideration, some hypotheses have been proposed as follows:

H4: Pleasure emotion positively influences place identity.

H5: Pleasure emotion positively influences place dependence.

Promotional stimuli can be measured in terms of their ability to arouse people by incorporating emotional information (Goossens 2000). The feeling of arousal, as part of emotional involvement, arises out of a particular stimulus or circumstance and has the properties and consequences of drive, which include the sense of seeking, processing information and making decisions (Rothschild 1984). Affective appraisal of arousal about a place in a person’s memory can often largely influence place attachment, including place identity and dependence (Ratcliffe and Korpela 2017). Excitement as a part of the arousal emotion arising from the virtual world has been validated to stimulate place attachment to the real place (Oleksy and Wnuk 2017). Given this consideration, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H6: Arousal emotion positively influences place identity.

H7: Arousal emotion positively influences place dependence.

A key emotional driver of celebrity influence on consumer-celebrity relationships is admiration, which is often elicited by forms of celebrity attachment (Moraes et al. 2019). A high degree of celebrity involvement is generally characterised by positive attitudes towards products or brands that are associated with celebrities that people admire (Ilicic and Webster 2021). In film-induced tourism research, both attachment and involvement towards the film star can be transferred to place attachment (Wong and Lai 2015; Chen 2017). Therefore, the following hypotheses arise from this study:

H8: Admiration emotion positively influences place identity.

H9: Admiration emotion positively influences place dependence.

Visit Intention

Visit intention, which is a person’s expectation or future action, refers to the probability of future travel (Su et al. 2020). Whereas most of the literature does not distinguish between tourists and visitors regarding visit intentions, Davari and Jang (2021) restricted tourists to non-visitors and defined visit intention as the decision to travel to a destination for the very first time.

In the context of film-induced tourism, visit intention is the willingness to visit places once depicted in film or TV drama, including filming sites and associated theme parks (Hahm and Wang 2011; Florido-Benítez 2023). Tourism research from the perspective of the SOR model often categorises visit intention as a behavioural response (Hsiao and Tang 2021). The tourism industry relies heavily on marketing, and operators often use mass media to shape destinations to attract tourists (Leung and Jiang 2018; Baber and Baber 2022). Apart from bringing brand equity to the destination, a proper marketing strategy also strengthens the emotional attachment of tourists to the destination (Chi et al. 2020; Teng and Chen 2020).

Tourists can transfer their enjoyment of a person or thing to a certain destination that they have never visited before (Zhang et al. 2020). Min et al. (2019) used SOR theory to suggest further that music-induced emotions can lead to tourist visitation, and such emotions include pleasures and arousal. Kim and Kim (2017) demonstrated that fictional characters in film and TV drama strongly influence viewers’ emotional engagement, and that a mental and emotional engagement with the film is expected from film tourists. Xu and Tan (2019) pointed out that fictional characters in film and TV drama also induce admiration, which is an emotion that also prompts audiences’ longing to be close to filming sites. Admiration can serve as a driving force behind their inclination to embark on a visit, precisely encapsulating the essence of film tourism (Ono et al. 2020). Therefore, the following hypotheses arise from this study:

H10: Pleasure emotion positively influences visit intention.

H11: Arousal emotion positively influences visit intention.

H12: Admiration emotion positively influences visit intention.

Some researchers suggested that place attachment is an important assessment that can be used to evaluate an individual’s visit intention (Cho 2021; Wan et al. 2021). Specifically, place dependence is an intentional mental activity that shows an individual’s tendency to act on a place (Borden and Schettino 2010; Halpenny, 2010). Place attachment promotes a strong association between behavioural tendencies and place identity (Neuvonen et al. 2014). Place identity involves the perception of a place by an individual (Liu et al. 2021). A strong sense of place attachment is formed in the psychological response; most importantly, it becomes an important factor in promoting film tourism (Hosany et al. 2019). With the support of other technologies, the sense of attachment generated without the need for physical experience can also have a positive impact on visit intention. The introduction of VR virtual technology allows even unvisited destinations to create attachments and induce their visit intention (Atzeni et al. 2021). Therefore, the following hypotheses arise from this study:

H13: Place dependence will have a positive influence on visit intention.

H14: Place identity will have a positive influence on visit intention.

Reception Aesthetics and Justice Sensitivity

‘Expectation horizon’ is a fundamental concept in reception aesthetics theory. A literary work employs textual strategies, signals, familiar characteristics or implicit allusions to evoke memories of the familiar, stir specific emotions in the reader and create expectations (Jauss and Benzinger 1970). Various elements that filmmakers emphasised and transmitted were used to convey meanings to the audience (Xie et al. 2022). According to reception theory in film and television research, encoded information has multiple directivities and an open meaning. Decoding the information will occur as the audience identifies with the encoder’s ideology’s shape and meaning (Hall et al. 1980). In other words, the audience does not passively accept a creative work. Instead, audiences’ interpretations of the creative work are influenced by their unique cultural backgrounds and personal experiences.

People highly desire a world of justice; the expectation is the same in the fictional world of film (Welsh et al. 2011), demonstrating a realistic response to aesthetic reception theory. A longstanding and close connection has existed between matters of justice and popular superhero narrative films such as Marvel movies (Maruo-Schröder 2018). The ‘call to do justice’ expressing tendencies of superheroes in films and TV series have arguably become the foremost symbols of substantive justice in popular culture, achieving the right outcome even if it means sacrificing some aspects of procedural fairness since the 1940s (Bainbridge 2015). Narrative themes commonly incorporate vengeance and punishment for wrongdoing and their connection to justice such as Batman (1966), The Punisher (2004) and Spider-Man (2002) (Coyne et al. 2004; Holbert et al. 2016).

Justice is a fundamental value in human life (Lerner 1980). As a predictor of criminal justice-related emotions and behaviour, justice sensitivity reflects an individual’s concern for justice (Baumert et al. 2013). The key components of justice sensitivity include sensitivity to the suffering of others, a belief in the importance of justice and a motivation to take action to rectify injustice (Schmitt et al. 2005). An important aspect of justice sensitivity is emotional reactivity towards perceived injustices (Baumert and Schmitt 2016). A relatively stable and consistent personality variable, namely, justice sensitivity, has been shown to predict people’s reactions when they experience or witness injustice (Mohiyeddini and Schmitt 1997; Schmitt and Dörfel 1999). People of this type tend to protest injustice and work towards restoring justice (Schmitt 1996) and taking action against perpetrators even at their own expense (Fetchenhauer and Huang 2004). Accordingly, people with a high level of justice sensitivity may ruminate on injustices experienced longer and more intensely than people with a lower level of justice sensitivity (Schmitt 1996). Furthermore, scholars found that people with high justice sensitivity perceived more justice after a redress of injustice than people with low justice sensitivity (Baumert and Schmitt 2009).

In fact, a similar situation was portrayed when the audience saw the film. Using film clips that show intentional harm or help, Yoder and Decety (2014) investigated the effects of prosocial perspectives of justice sensitivity. People with higher levels of justice sensitivity developed stronger reactions to bad actions in areas of the brain responsible for understanding mental states, identifying others’ intentions and retaining goal representations (Yoder and Decety 2014). After witnessing injustice from film clips in Witness (1985), justice-sensitive individuals were more sensitive to unjust stimuli than negative control stimuli (Baumert et al. 2020). Baumert and Schmitt (2016) argued that a justice-sensitive person reacts strongly to subjective injustice, regardless of whether justice principles are being violated in a particular circumstance. Thus, the possibility of differences should exist in the emotional responses of audiences with different levels of justice sensitivities to the same film character.

For villainous characters, three hypotheses are formulated.

H15: Justice sensitivity negatively moderates the relationship between perceived charismatic leadership and pleasure emotion.

H16: Justice sensitivity negatively moderates the relationship between perceived charismatic leadership and arousal emotion.

H17: Justice sensitivity negatively moderates the relationship between perceived charismatic leadership and admiration emotion.

According to Hypotheses 1–17, Fig. 1 presents the theoretical framework for this study.

Research Methods

Study Setting

The Knockout (狂飙), a Chinese police and crime drama launched in January 2023, has received considerable attention. After its release, this TV drama has been reported to have attracted a cumulative audience of 319 million viewers on cable television networks in China; even more, the stock price of co-producer iQiyi, a commercial online streaming platform known for producing hit shows, rose by nearly 10 percent.Footnote 1 With the hit TV drama, Jiangmen—a city in Guangdong where this drama was filmed—has become an instantly popular tourist destination. According to the data cited by the Jiangmen government, the number of tourists at the filming location increased nearly fivefold from the previous year. Search heat increased by 130 percent.Footnote 2 Particularly, the filming locations related to the main villain character, Gao Qiqiang (高启强), have become pilgrimage sites for tourists. On social media platforms such as Tiktok and Xiaohongshu, many travel bloggers also posted videos or pictures of travel routes related to Gao, which attracted a wide range of views and likes.Footnote 3;Footnote 4 The local government has created a VR live-action map on the basis of the eight pick-up points related to Gao in the drama to easily facilitate tourists’ search for a spot to hit.Footnote 5 Accordingly, tourists can compare the live action with the drama footage and thus gain a profound impression of them. This reality is used as the context of this study to explore how the villainous character Gao Qiqiang’s perceived charismatic leadership in the fictional story affects the audience’s emotions, place attachment and behavioural intentions.

Measurements and data collection

This study developed a self-administered questionnaire on the basis of existing research. It rated each item on a seven-point Likert scale between 7 (strongly agree) and 1 (strongly disagree). The measurement items of perceived charismatic leadership towards a fictional character were developed from previous studies (Conger et al. 2000). These items were categorised into five dimensions, including strategic vision and articulation (7 items), personal risk (3 items), sensitivity to the environment (4 items), sensitivity to member needs (3 items) and unconventional behaviour (3 items). Items for assessing audience emotions were adopted from Meng et al. (2021). Four items measured audiences’ pleasure emotions triggered by a fictional character. Audiences’ arousal emotions were evaluated with three items. Four items were used to measure audiences’ admiration for a fictional character. The place attachment scale was adopted from Hosany et al. (2019) and divided into two independent dimensions, namely, place identity (5 items) and place dependence (4 items). A three-item scale of visit intention was developed from Han et al. (2010). A six-item scale measuring audiences’ justice sensitivity was developed from Sabbagh (2021). Translation accuracy is ensured by back-translation for all items in the Chinese version questionnaire. Some items were reworded to avoid confusion or misunderstandings and match the study context.

Additionally, 50 potential tourists were invited to participate in the pilot test. Pilot test respondents expressed no remarkable concerns. Finally, the measurement scale consisting of 49 items formed a central part of the questionnaire. Detailed information on all items can be found in Appendix 1. Following this section is the collection of demographic information regarding the participants.

Based on previous research experience, the online panel survey method is well-accepted for studies of TV drama or film-induced tourism (Kim and Kim 2017; Kim et al. 2017). This method has many advantages, such as the ability to select precise target samples and the ability to collect data immediately (Grönlund and Strandberg 2014). Data collection was assisted by an online panel company in China with approximately 4 million members from the 1st of April to the 25th of April, 2023. The two criteria for selecting respondents for this study are as follows: (1) must have watched the TV drama series The Knockout and (2) had never travelled to Jiangmen. To reduce the generation of common method bias, the order of all items in the measurement scale section was randomised with the help of an online survey system. Based on the pilot test experience, the minimum time to complete the questionnaire in full was three and a half minutes. To improve the reliability of the data, all questionnaires with less than 3.5 min of response time were considered invalid. A total of 550 questionnaires were completed. After excluding 18 invalid forms, 532 completed questionnaires remained for further analysis.

Data analysis technology

As per recommendation by Hair Jr et al. (2022), PLS-SEM has been validated to handle structurally complex research models and to conduct exploratory studies efficiently. In tourism research, particularly in the context of film-induced tourism, PLS-SEM has been demonstrated as an effective method for handling theoretical models with moderating variables (Wu and Lai 2021; Yang et al. 2022). Given that the research model in this study is structurally complex, that is, possessing a high-order independent variable and a moderating variable, PLS-SEM will be utilised to validate the study’s theoretical model. According to the ten-time rule, 490 samples are this study’s minimum sample size for PSL-SEM. The sample size of 532 obtained during the data collection phase thus fulfilled the requirement for conducting further analyses (Hair et al. 2011).

Results

Sample Profile

Table 1 shows that women comprised the majority of respondents, accounting for 66.17% of the overall respondents. More than 60% of respondents were 36–45. Regarding education level, 95.86% of respondents possess a college diploma or above, indicating a high education level. The income of nearly half of the respondents ranges from RMB 5,001 and 10,000 a month. By contrast, 29.51% have a monthly income between RMB 10,001 and 20,000. Respondents who did not reside in Guangdong Province accounted for 79.89%.

Common method bias

Although in terms of procedural design, this study utilised a questionnaire distribution system in which the measurement items were accessible for respondents to answer in a random order with the goal of reducing the possibility of Common Method Bias (CMB), a validation step after data collection remained essential. Two statistical verification methods were used for statistical validation. As a first step, validation of the CMB problem was conducted using Harman’s one-factor test. One factor explained 30.36% of the variance, less than the 50% threshold (Podsakoff et al. 2012). Additionally, the pathological VIF measurements ranged from 1.042 to 2.902, which is below the critical value of 3.3; this finding indicates that the CMB was not a concern (Kock 2015).

Measurement Model

In the research model, one construct, namely, perceived charismatic leadership, is a high-order component; accordingly, the two-stage approach for estimating reliability and convergent validity was employed (Hair Jr et al. 2022).

In the first stage, the measurement model for low-order constructs and first-order dimensions of perceived charismatic leadership is evaluated. Cronbach’s α (0.706 to 0.936) and the Composite reliability values (0.836 to 0.954) are greater than 0.7, confirming the reliability in the first stage of the assessment. In addition, values of factor loading (0.715 to 0.952) and AVE (0.584 to 0.856) were above 0.7 and 0.5, respectively. This finding indicates that the measurement model assessment in the first stage has acceptable convergent validity. Table 2 summarises the first stage’s assessment.

The second stage evaluates the measurement model for high-order components of perceived charismatic leadership. Factor loadings for the five sub-dimensions onto the perceived charismatic leadership construct were greater than 0.7. Composite reliability, Cronbach’s α and AVE are all above the threshold, confirming acceptable results of the assessment in the second stage (see Table 3 for details).

Combining the Fornell-Larcker criterion with an HTMT analysis was used to estimate the discriminant validity of the measurement model. Given that the square root of the AVE is greater than the correlation between the constructs and all of the HTMT values are under 0.85, the satisfaction of discriminant validity can be confirmed (see Table 4 for further details).

Structural Model

To determine whether or not the structural model accurately predicted the data, the values of R2 and Q2 were used as a first step in the structural model evaluation process. An acceptable R2 and Q2 must be larger than 0.1 and 0, respectively. Table 5 shows that the R2 value ranges from 0.103 to 0.594, whilst the Q2 value ranges from 0.414 to 0.581. Consequently, these results reliably predict the efficiency of the structural model.

A bootstrapping method involving 5000 resamples was used to determine whether the constructs were statistically significant. Figure 2 and Table 6 illustrate the arithmetic diagram and detailed calculation results in SmartPLS software, respectively. Three significant associations exist between perceived charismatic leadership and emotions and are reflected in the establishment of H1, H2 and H3. As for the relationship between the three types of emotions and place attachment, all hypotheses were verified except for the statistically insignificant relationship between pleasure emotion and place identity. That is, H5 is unacceptable; whereas H4 and H5 to H9 are acceptable. As for the hypotheses related to visit intention, the validation results showed that the effect of pleasure and admiration emotion on visit intention is insignificant. This finding is reflected in the fact that H10 and H12 are invalid. The effect of arousal emotion and place attachment on visit intention is significant; thus H11, H13 and H14 are valid.

Hypotheses related to moderating effects were also examined using a bootstrapping technique. The interactive effect of justice sensitivity and perceived charismatic leadership are significantly associated with pleasure emotion (β = −0.114, t = 2.856), arousal emotion (β = −0.143, t = 4.042) and admiration emotions (β = −0.112, t = 2.88) suggesting that the moderating effect of justice sensitivity is supported. Thus, H15, H16 and H17 are supported. Figures 3–5 illustrate the results of the simple slope analysis. Differences in the slope of the line due to different degrees of judicial sensitivity indicate the negative moderation effect of justice sensitivity.

As the final part of the structural modelling assessment for this study, indirect effects are also analysed to determine the degree of complexity of the relationships between the variables. Table 7 shows nine indirect paths (IPs) for forming visit intention by perceived leadership. All seven IPs are significant except IP3 and IP7, which are insignificant. Notably, IP2’s significance explains H10’s insignificance because place dependence fully mediates the relationship between pleasure emotion and visit intention. The establishment of IP8 and IP9 explains why H12 is not supported. The relationship between admiration emotion and visit intention is fully mediated by place attachment.

Discussion and conclusions

As mentioned in the literature review, research on film tourism has increasingly focused on film characters and story elements that are easily communicated through social media, but little is known regarding the antecedents of film tourists’ behaviour, particularly in relation to plots and character traits. This study aims to introduce perceived charismatic leadership by analysing the emotional contagion of audiences triggered by the popular Chinese TV drama The Knockout and its evil character, Gao Qiqiang, and to develop a novel and conceptual model for explaining film tourists’ visit intention. Up until now, a set of evidence supports that perceived charismatic leadership has a significant impact on emotional contagion and is therefore a driving force behind film tourism. A brief discussion of the key findings is provided below.

Firstly, perceived charismatic leadership has a positive impact on pleasure emotion (H1), arousal emotion (H2) and admiration emotion (H3). Given that these three emotions are considered important indicators in marketing research related to emotional contagion, the perceived charismatic leadership towards evil characters in the film can be inferred to have a significant impact on the emotional contagion of the audience. This finding is consistent with previous studies in film narrative studies (Long 2017; Kuri and Kaufman 2020). In contrast to the abstract nature of film and TV drama theories and their absence of empirical validation, this study empirically validated character arc theory and charismatic leadership theory of film and TV drama narratives by using empirical methods as well as linking them with tourism marketing theories. By comparing the degree to which the three emotions were affected, this study also found that admiration emotion was most affected by perceived charismatic leadership (H3: β = 0.47). This result is consistent with findings from organisational behaviour research (Sy et al. 2018) and extends the conclusions from real individuals to fictional characters.

Secondly, results demonstrate the complex relationship of emotional contagion with place attachment and visit intention. Pleasure emotion has a positive impact on place dependence (H4) and insignificant effect on place identity (H5). This result indicates that the pleasurable emotion of the audience is responsible for making film tourism more attractive than other destinations. However, the audience’s emotional attachment to the film tourism was unaffected. The result that pleasure emotion had no statistically significant effect on place identity has also appeared in previous studies (Gross and Brown 2008; Ratcliffe and Korpela 2017). However, in the study of Ratcliffe and Korpela (2017), pleasure emotion has a negative impact on place dependence. The reason for the opposite result is likely to be that previous studies have not distinguished between travellers who have been to the destination before. Both arousal and admiration emotions positively affect place attachment (H6–H9). These findings provide credence to the research of Oleksy and Wnuk (2017), which focused on game marketing, and the research of Ilicic and Webster (2021), which focused on celebrity-related marketing. Compared with previous film tourism research (Wong and Lai 2015; Chen 2017), the results of this study extend the psychological factors influencing place attachment from celebrity attachment and involvement to three specific emotional dimensions.

Moreover, arousal emotion and place attachment positively affect visit intention (H11, H13 and H14). Pleasure and admiration do not significantly affect visit intention (H10 and H12). Although previous research on tourism advertising has validated that visit intention is positively influenced by arousal emotion and place attachment (Hosany et al. 2019), our study further clarifies the triangulation of emotion, place attachment and visit intention by examining indirect pathways. Place attachment demonstrates an important intermediary role in the relationship between emotion and visit intention (IP2, IP5, IP6, IP8 and IP9). The audience’s positive emotions are confirmed to have elicited a psychological response (place attachment), which later developed into a behavioural response (visit intention) as a result of its positive feelings towards the characters in the film and TV drama.

Finally, the audience’s justice sensitivity can undermine the positive emotions generated by the villainous characters’ perceived charismatic leadership. In other words, under the same perceived charismatic leadership influence, the higher the audience’s justice sensitivity, the less positive emotions are generated towards the villain character (H15–H17). Our study contests authority of reception aesthetics theory through an empirical approach, revealing that viewers’ values affect their evaluation of film and TV characters (Xie et al. 2022). Whereas villains can positively affect film tourism, justice cannot be ignored and is still expected to exist in the fictional world of film (Baumert and Schmitt, 2016; Baumert et al. 2020).

Theoretical and practical implications

This study introduces a comprehensive model based on film and TV drama narrative theory, ECT and the SOR model, which provides a deeper understanding of film tourism behaviour triggered by film characters and storylines and has theoretical and practical importance.

Theoretically, this study empirically links film and TV drama characterisation with emotional contagion theory, taking character arc and charismatic leadership on screenwriting beyond mere artistic creation to the realm of psychology and marketing. This study demonstrates that the perceived charismatic leadership of fictional characters can generate emotional contagion, establishing a theoretical foundation for future research on the relationship between virtual characters in screened media, such as AI or game characters, and their audiences’ psychology.

In addition, this study grants more exhaustive evidence to reception aesthetics theory by validating the relationship between the perceived charismatic leadership of an evil character and the audience’s justice sensitivity. Therefore, this study highlights the need to move beyond simply discussing the impact of character attractiveness on the audience whilst considering the values and cultural context of the different audiences to gain a better understanding of the complexities of emotional contagion theory.

Finally, this study extends the push-pull theory related to film tourism. Previous studies tend to discuss the stimulation of film tourists by motivation factors from the perspective of film tourists’ emotions and needs. The perceived charismatic leadership validated in this study is closely related to the story and film characters and is an antecedent of emotional contagion for the audience. Prior research considered film-induced tourism as a sporadic behaviour, primarily due to the limited exploration of the “pull” factors related to film plots and characters in these push-pull theory-based studies (Chemli et al. 2022). The findings of this study enhance the potential for film-induced tourism to become a more predictable activity. Notably, in the context of the rapid development of social media and digital streaming platforms, this research provides a theoretical foundation for future studies focusing on uncovering additional film-induced tourism marketing elements conducive to social media dissemination. In contrast to previous research, which predominantly focused on decent characters in film-induced tourism, this study broadens the scope and subject of film-induced tourism research. Investigating villainous characters is crucial for shaping tourism marketing strategies and can expand the perspectives of tourism marketers.

Thus, from a practical point of view, this study demonstrates that villain characters can also be involved in film tourism marketing. The premise of villainous characters’ involvement in film-induced tourism is that tourism marketers must thoroughly understand the storyline of film and TV drama and assess whether the villainous characters demonstrate charismatic leadership in the story of film and TV drama. Destination management organisations (DMOs) can strategically arrange filming locations that showcase the charismatic leadership qualities of these antagonist characters in the most prominent tourist destinations they aim to promote. The success of film-induced tourism relies on the ability to anticipate the market types and sizes that find a particular destination attractive and to develop corresponding plans, thus addressing sustainability concerns (Nakayama 2022). As a result, DMOs and tourism marketers must stay attuned to the latest reactions on social media regarding characters and storylines from screened media contents. This enables them to follow online trends while understanding the interests of the relevant audience, privileging the development of targeted marketing strategies. Moreover, these marketing strategies must consider film tourists’ values and cultural backgrounds, as this process is critical in determining whether villainous characters can stimulate the intention to travel.

In addition, this study sheds light on the practice of film screenwriting. Creating villainous characters is necessary for film screenwriting under the influence of the wave of anti-heroism. When creating a screenplay, screenwriters need to consider a storyline that can fully demonstrate the charismatic leadership of the villain to enhance the villainous character’s appeal to the audience. Moreover, the overall sense of justice can affect the viewing experience of specific viewers.

Limitations and future research

Despite the practical and theoretical significance of this study’s findings, some limitations persist. The measures of perceived charismatic leadership and emotions were primarily derived from Chinese TV dramas and Chinese viewers. The study results are not necessarily applicable to TV dramas and viewers in other countries and regions (Ng and Chan 2019). Therefore, future research could discuss possible differences in results across geographical locations and cultural contexts.

Secondly, this study focused on a trait of a villainous character in a police and crime drama, which may not necessarily apply to fictional characters in other media (Puche-Ruiz 2022). Future studies may consider gathering other factors from different types of screened media, such as documentaries, comedies, cartoons and games, among others.

Lastly, the data collected for this study mostly originated from viewers who had never travelled to the destinations depicted in the films or TV dramas. Future research could collect tourists who have visited film tourism destinations and discuss the influence of characters on film tourists’ behavioural intentions after watching the film. Simultaneously, integrating factors related to characters and storylines into research based on the push-pull theory can further establish the significance of these elements within the realm of film-induced tourism studies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available as a form of supplementary file and/or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

https://v.douyin.com/iatyuxD/ (in Chinese).

http://xhslink.com/p8B9ls (in Chinese).

https://40dgfwrf5.wasee.com/wt/40dgfwrf5 (in Chinese).

References

Abbasi AZ, Schultz CD, Ting DH, Ali F, Hussain K (2022) Advertising value of vlogs on destination visit intention: the mediating role of place attachment among Pakistani tourists. J Hospitality Tour Technol 13(5):816–834. https://doi.org/10.1108/jhtt-07-2021-0204

Algoe SB, Haidt J (2009) Witnessing excellence in action: the ‘other-praising’ emotions of elevation, gratitude, and admiration. J Posit Psychol 4(2):105–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760802650519

Allen J (2009) The film viewer as consumer. Q Rev Film Stud 5(4):481–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509208009361066

Atzeni M, Del Chiappa G, Mei Pung J (2021) Enhancing visit intention in heritage tourism: the role of object‐based and existential authenticity in non‐immersive virtual reality heritage experiences. Int J Tour Res 24(2):240–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2497

Avraham E (2021) Recovery strategies and marketing campaigns for global destinations in response to the Covid-19 tourism crisis. Asia Pac J Tour Res 26(11):1255–1269. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2021.1918192

Baber R, Baber P (2022) Influence of social media marketing efforts, e-reputation and destination image on intention to visit among tourists: application of SOR model. J Hospitality Tourism Insights. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-06-2022-0270

Bainbridge J (2015) The Call to do Justice”: Superheroes, Sovereigns and the State During Wartime. Int J Semiotics Law—Rev Int de Sémiotique Jurid 28(4):745–763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-015-9424-y

Barsade SG (2002) The ripple effect: emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Adm Sci Q 47(4):644–675. https://doi.org/10.2307/3094912

Bartsch A (2012) Emotional gratification in entertainment experience. why viewers of movies and television series find it rewarding to experience emotions. Media Psychol 15(3):267–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2012.693811

Baumert A, Gollwitzer M, Staubach M, Schmitt M (2020) Justice sensitivity and the processing of justice–related information. Eur J Personal 25(5):386–397. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.800

Baumert A, Rothmund T, Thomas N, Gollwitzer M, Schmitt M (2013) Belief in a just world and justice sensitivity as potential indicators of the justice motive. In: Heinrichs K, Oser FK, Lovat T (eds) Handbook of moral motivation. Brill

Baumert A, Schmitt M (2009) Justice-sensitive interpretations of ambiguous situations. Aust J Psychol 61(1):6–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530802607597

Baumert A, Schmitt M (2016) Justice sensitivity. Handbook of social justice theory and research, 161–80

Borden RJ, Schettino AP (2010) Determinants of environmentally responsible behavior. J Environ Educ 10(4):35–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1979.9941906

Carroll N (2010) Movies, the Moral Emotions, and Sympathy. Midwest Stud Philos 34(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4975.2010.00197.x

Chemli S, Seo KJ, Nunes S, Sejdini A, Del Moral Agúndez A, Da Fonseca JF (2022) The importance of film-induced tourism as a motivational influence on travel decisions: analysis of push and pull factors from the perspective of Portuguese consumers. Int J Tourism Policy 12(4). https://doi.org/10.1504/ijtp.2022.10053173

Chen C-Y (2017) Influence of celebrity involvement on place attachment: role of destination image in film tourism. Asia Pac J Tour Res 23(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2017.1394888

Chen F, Mele C (2017) Film-induced pilgrimage and contested heritage space in Taipei City. City, Cult Soc 9:31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2016.02.001

Cherulnik PD, Donley KA, Wiewel TSR, Miller SR (2001) Charisma is contagious: the effect of leaders’ charisma on observers’ Affect1. J Appl Soc Psychol 31(10):2149–2159. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb00167.x

Chi H-K, Huang K-C, Nguyen HM (2020) Elements of destination brand equity and destination familiarity regarding travel intention. J Retailing Consumer Services 52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.12.012

Cho H (2021) How nostalgia forges place attachment and revisit intention: a moderated mediation model. Mark Intell Plan 39(6):856–870. https://doi.org/10.1108/mip-01-2021-0012

Conger JA (1989) The charismatic leader: Behind the mystique of exceptional leadership. Jossey-Bass

Conger JA, Kanungo RN (1994) Charismatic leadership in organizations: perceived behavioral attributes and their measurement. J Organ Behav 15(5):439–452. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030150508

Conger JA, Kanungo RN, Menon ST (2000) Charismatic leadership and follower effects. J Organ Behav: Int J Ind Occup Organ Psychol Behav 21(7):747–767. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1379(200011)21:7%3C747::AID-JOB46%3E3.0.CO;2-J

Connell J (2012) Film tourism—evolution, progress and prospects. Tour Manag 33(5):1007–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.02.008

Coplan A (2006) Catching characters emotions: emotional contagion responses to narrative fiction film. Film Stud 8(1):26–38. https://doi.org/10.7227/fs.8.5

Coplan AMY (2011) Will the real empathy please stand up? a case for a narrow conceptualization. South J Philos 49:40–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-6962.2011.00056.x

Coyne SM, Archer J, Eslea M (2004) Cruel intentions on television and in real life: can viewing indirect aggression increase viewers’ subsequent indirect aggression? J Exp Child Psychol 88(3):234–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2004.03.001

Davari D, Jang S (2021) Visit intention of non-visitors: a step toward advancing a people-centered image. J Destination Marketing Manag 22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100662

DeCelles KA, Pfarrer MD (2004) Heroes or villains? corruption and the charismatic leader. J Leadersh Organ Stud 11(1):67–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190401100108

Di-Clemente E, Moreno-Lobato A, Sánchez-Vargas E, Pasaco-González B-S (2022) Destination promotion through images: exploring tourists′ emotions and their impact on behavioral intentions. Sustainability 14(15). https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159572

Döveling K, Scheve CV, Konijn EA (2010) The Routledge handbook of emotions and mass media. Routledge

Du J, Fan X, Feng T (2010) Multiple emotional contagions in service encounters. J Acad Mark Sci 39(3):449–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0210-9

Eaton AW (2010) Rough Heroes of the New Hollywood. Revue Int Philosophie (4), 511–24. https://doi.org/10.3917/rip.254.0511

Eaton AW (2012) Robust Immoralism. J Aesthet Art Criticism 70(3):281–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6245.2012.01520.x

Eder J (2010) Understanding characters. Projections 4(1):16–40. 10:3167/proj.2010.040103

Edwards G, Schedlitzki D, Ward J, Wood M (2015) Exploring critical perspectives of toxic and bad leadership through film. Adv Dev Hum Resour 17(3):363–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422315587903

Feng D, O’Halloran, KL (2013) The multimodal representation of emotion in film: Integrating cognitive and semiotic approaches. Semiotica 2013(197). https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2013-0082

Fetchenhauer D, Huang X (2004) Justice sensitivity and distributive decisions in experimental games. Personal Individ Differences 36(5):1015–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(03)00197-1

Florido-Benítez L (2022) The impact of tourism promotion in tourist destinations: a bibliometric study. Int J Tour Cities 8(4):844–882. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijtc-09-2021-0191

Florido-Benítez L (2023) Film-induced tourism—the impact the of animation, cartoon, superhero and fantasy movies. Tourism Rev https://doi.org/10.1108/tr-11-2022-0537

Floyd MF (1997) Pleasure, arousal, and dominance: Exploring affective determinants of recreation satisfaction. Leis Sci 19(2):83–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490409709512241

Gernsbacher MA, Goldsmith HH, Robertson RR (1992) Do readers mentally represent characters’ emotional states? Cognition Emot 6(2):89–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699939208411061

Gini A, Green RM (2013) 10 virtues of outstanding leaders: leadership and character. John Wiley & Sons

Gómez-Morales B, Nieto-Ferrando J, Sánchez-Castillo S (2022) (Re)Visiting Game of Thrones: film-induced tourism and television fiction. J Travel Tour Mark 39(1):73–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2022.2044971

Goossens C (2000) Tourism information and pleasure motivation. Ann Tour Res 27(2):301–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0160-7383(99)00067-5

Grindstaff L, Murray S (2015) Reality celebrity: branded affect and the emotion economy. Public Cult 27(1):109–135. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2798367

Grönlund K, Strandberg K (2014) Online panels and validity. In: Callegaro M, Baker JBR, Göritz AS, Krosnick JA, Lavrakas PJ (eds) Online panel research: A data quality perspective. Wiley, pp 86–103

Gross MJ, Brown G (2008) An empirical structural model of tourists and places: Progressing involvement and place attachment into tourism. Tour Manag 29(6):1141–1151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.02.009

Hahm J, Wang Y (2011) Film-induced tourism as a vehicle for destination marketing: is it worth the efforts? J Travel Tour Mark 28(2):165–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2011.546209

Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2011) PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J Mark theory Pract 19(2):139–152

Hair Jr JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2022) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) 3 edn. Sage

Hall S, Hobson D, Lowe A, Willis P (1980) Culture, media, language: Working papers in cultural studies. Routledge

Halpenny EA (2010) Pro-environmental behaviours and park visitors: the effect of place attachment. J Environ Psychol 30(4):409–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.04.006

Han H, Hsu L-T, Sheu C (2010) Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour Manag 31(3):325–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.03.013

Hatfield E, Cacioppo JT, Rapson RL (1993) Emotional contagion. Curr Directions Psychol Sci 2(3):96–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10770953

Holbert RL, Shah DV, Kwak N (2016) Fear, authority, and justice: crime-related TV viewing and endorsements of capital punishment and gun ownership. Journalism Mass Commun Q 81(2):343–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900408100208

Hosany S, Buzova D, Sanz-Blas S (2019) The influence of place attachment, ad-evoked positive affect, and motivation on intention to visit: imagination proclivity as a moderator. J Travel Res 59(3):477–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519830789

Hsiao C-H, Tang K-Y (2021) Who captures whom—Pokémon or tourists? A perspective of the Stimulus-Organism-Response model. Int J Inform Manag 61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102312

Ilicic J, Webster CM (2021) Effects of multiple endorsements and consumer–celebrity attachment on attitude and purchase intention. Australas Mark J 19(4):230–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2011.07.005

Im HH, Chon K (2008) An exploratory study of movie‐induced tourism: a case of the moviethe sound of Musicand its locations in Salzburg, Austria. J Travel Tour Mark 24(2-3):229–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548400802092866

Immordino-Yang MH, McColl A, Damasio H, Damasio A (2009) Neural correlates of admiration and compassion. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106(19):8021–8026. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0810363106. May 12

Irwin W (2012) In: Dunn GA, Michaud N, eds. The hunger games and philosophy: a critique of pure treason. John Wiley and Sons

Jauss HR, Benzinger E (1970) Literary history as a challenge to literary theory. New Literary History 2(1). https://doi.org/10.2307/468585

Jelinčić DA (2022) Stress for the wellness sectors: the paradox of culture and tourism in the COVID-19 times. In: Tourism recovery from COVID-19. World Scientific, pp 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789811260247_0002

Khalifa-Gueta S (2022) The goddess, Daenerys Targaryen and me too values. Acta Universitatis Sapientia, Film Media Stud 22(1):139–161. https://doi.org/10.2478/ausfm-2022-0016

Kim S (2010) Extraordinary experience: re-enacting and photographing at screen tourism locations. Tour Hospitality Plan Dev 7(1):59–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790530903522630

Kim S (2011) Audience involvement and film tourism experiences: emotional places, emotional experiences. Tourism Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.04.008

Kim S, Kim S (2017) Perceived values of TV drama, audience involvement, and behavioral intention in film tourism. J Travel Tour Mark 35(3):259–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2016.1245172

Kim S, Kim S, Petrick JF (2017) The effect of film nostalgia on involvement, familiarity, and behavioral intentions. J Travel Res 58(2):283–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517746015

Kjeldgaard-Christiansen J, Fiskaali A, Høgh-Olesen H, Johnson JA, Smith M, Clasen M (2021) Do dark personalities prefer dark characters? A personality psychological approach to positive engagement with fictional villainy. Poetics 85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2020.101511

Kock N (2015) Common method bias in PLS-SEM. Int J e-Collaboration 11(4):1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

Krolikowska E, Kuenzel S, Morrison AM (2019) The ties that bind: an attachment theory perspective of social bonds in tourism. Curr Issues Tour 23(22):2839–2865. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1677571

Kuri SK, Kaufman EK (2020) Leadership insights from hollywood‐based war movies: an opportunity for vicarious learning. J Leadersh Stud 14(1):53–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/jls.21682

Kyle GT, Mowen AJ, Tarrant M (2004) Linking place preferences with place meaning: an examination of the relationship between place motivation and place attachment. J Environ Psychol 24(4):439–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2004.11.001

Lee MT, Theokary C (2021) The superstar social media influencer: exploiting linguistic style and emotional contagion over content? J Bus Res 132:860–871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.11.014

Lerner MJ (1980) The belief in a just world. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0448-5

Leung XY, Jiang L (2018) How do destination Facebook pages work? An extended TPB model of fans’ visit intention. J Hospitality Tour Technol 9(3):397–416. https://doi.org/10.1108/jhtt-09-2017-0088

Li W, Kim YR, Scarles C, Liu A (2022) Exploring the impact of travel vlogs on prospect tourists: a SOR based theoretical framework. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2022, Cham

Lindsay C (2009) The tourist as spectator: Arthur Hugh Clough’s Amours de Voyage Dickens and tourism conference, September 2009, Nottingham

Liu W-Y, Yu H-W, Hsieh C-M (2021) Evaluating forest visitors’ place attachment, recreational activities, and travel intentions under different climate scenarios. Forests 12(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/f12020171

Liu, Y, Chin, WL, Nechita, F, & Candrea, AN (2020) Framing film-induced tourism into a sustainable perspective from Romania, Indonesia and Malaysia. Sustainability 12(23). https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239910

Long BS (2017) Film narratives and lessons in leadership: insights from the Film & Leadership Case Study (FLiCS) Club. J Leadersh Stud 10(4):75–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/jls.21498

Lyons S (2021) The (Anti-)Hero with a Thousand Faces: Reconstructing Villainy in The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, and Better Call Saul. Can Rev Am Stud 51(3):225–246. https://doi.org/10.3138/cras-2020-017

Martínez-Sánchez ME, Nicolas-Sans R, Bustos Díaz J (2021) Analysis of the social media strategy of audio-visual OTTs in Spain: the case study of Netflix, HBO and Amazon Prime during the implementation of Disney +. Technol Forecasting Social Change 173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121178

Maruo-Schröder N (2018) “Justice Has a Bad Side”: Figurations of Law and Justice in 21st-Century Superhero Movies. Eur J Am Stud (13-4). https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.13817

McKee R (1997) Story: Substance, structure, style and the principles of screenwriting. 1997. Methuen, Kent, Great Britain

Meng L, Duan S, Zhao Y, Lü K, Chen S (2021) The impact of online celebrity in livestreaming E-commerce on purchase intention from the perspective of emotional contagion. J Retailing Consumer Services 63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102733

Min Z, Jie Z, Xiao X, Mengyuan Q, Youhai L, Hui Z, Tz-Hsuan T, Lin Z, Meng H (2019) How destination music affects tourists’ behaviors: travel with music in Lijiang, China. Asia Pac J Tour Res 25(2):131–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2019.1683046

Mohiyeddini C, Schmitt MJ (1997) Sensitivity to befallen injustice and reactions to unfair treatment in a laboratory situation. Soc Justice Res 10(3):333–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02683307

Moraes M, Gountas J, Gountas S, Sharma P (2019) Celebrity influences on consumer decision making: new insights and research directions. J Mark Manag 35(13-14):1159–1192. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257x.2019.1632373

Moss E (2014) “How I Had Liked This Villain! How I Had Admired Him!”: A. J. Raffles and the Burglar as British Icon, 1898–1939. J Br Stud 53(1):136–161. https://doi.org/10.1017/jbr.2013.209

Nakayama C (2022) Destination marketing through film-induced tourism: a case study of Otaru, Japan. J Hospitality Tour Insights 6(2):966–980. https://doi.org/10.1108/jhti-02-2022-0047

Neuvonen M, Pouta E, Sievänen T (2014) Intention to Revisit a National Park and Its Vicinity. Int J Sociol 40(3):51–70. https://doi.org/10.2753/ijs0020-7659400303

Ng T-M, Chan C-S (2019) Investigating film-induced tourism potential: the influence of Korean TV dramas on Hong Kong young adults. Asian Geographer 37(1):53–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/10225706.2019.1701506

Oleksy T, Wnuk A (2017) Catch them all and increase your place attachment! The role of location-based augmented reality games in changing people—place relations. Computers Hum Behav 76:3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.008

Ono A, Kawamura S, Nishimori Y, Oguro Y, Shimizu R, Yamamoto S (2020) Anime pilgrimage in Japan: Focusing Social Influences as determinants. Tourism Manag 76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.06.010

Oshriyeh O, Capriello A (2022) Film-induced tourism: a consumer perspective. In: Jaziri D, Rather RA (eds) Contemporary approaches studying customer experience in tourism research. Emerald Publishing Limited, pp 223–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80117-632-320221022