Abstract

By analysing big data collected from 1990 to 2017 on the consumption behaviours of men and women living alone and in heterosexual couples in Switzerland, we classified 75 food items in terms of their consumption within couple versus single households. We defined and quantified the gender dominance exhibited in the food purchasing activities of couples. Our results showed that to form consumption of couples, the average consumption of single women weighted 0.6, while that of men weighted 0.38. In addition, couples were found to consume more drinks and pricier foods than singles. Our findings span various areas, including the socioeconomics of food, food choice, social eating, gender power, eating behaviour and population and consumer studies. The robustness of the findings may be validated for other countries and cultures, and the findings may be of interest to researchers from various fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bonding and marriage are perceived differently by economists and sociologists. In the 20th century, economists defined the concepts and situations, in which two agents maximise a common or personal utility function (Debreu, 1951, 1954; Pigou, 1920; Varian, 1992), and games of two, in which both bargain and try to obtain the highest gain (common or shared; Gibbons, 1992; Nash, 1950; Shapley, 1953; von Neumann and Morgenstern, 1955 [1944]). More recently, coupling has also been described as a form of insurance or risk-sharing within a network or between networks (Fafchamps, 2008; Hayashi et al., 1996). Sociologists are also interested in the bargaining process that occurs before and during marriage (Bittman et al., 2003; Scanzoni and Scanzoni, 1976). They explored the role that coupling plays in preventing criminal behaviour (Chriss, 2007) and in modulating sexual life (Kornrich et al., 2013).

Taking an explicit socioeconomic stance, in this study, we explored the effect of bonding on food consumption behaviour in households. The nutrition of women and men has always differed and still differs (Baker and Wardle, 2003; Bloodhart and Swim, 2020; Steinbach et al., 2020; Toro et al., 2019; Valsecchi, 2021; Zhao et al., 2021). However, little is known about the differences in nutrition between men and women who live alone and those who live together in a household. Limited studies have been conducted in similar areas. For example, Hanson et al. (2007), Sobal et al. (2009), Sobal and Hanson (2011) and Chan and Sobal (2011) investigated gender, marriage and food dimensions and highlighted their effects on obesity and home food security. In other studies, household expenditure on food has been analysed (e.g. Eika et al., 2020; Mulamba, 2022). Nevertheless, to date, it has been unclear how the food basket of a couple differs from the baskets of two single people. The findings of this study provide the answer to this question, contribute to the field of the socioeconomics of food (e.g. Bhadra et al., 2023; Mann and Loginova, 2023; Sinclair and Diamond, 2022; Tyagi, 2023) and offer more insides for precise modelling of behaviour and decision-making in couples.

This study provides three core contributions to the field. First, using over 4.43 million observations collected by households in Switzerland over the last 30 years, we have comprehensively characterised food consumption by couples. More specifically, we have quantitatively demonstrated that men and women consume food at home differently when they are in a joint household compared to being single. Second, we have defined and classified the patterns found in the consumption behaviours, as described in Sections ‘Classification of the Foods’ and “Classification of Consumed Foods”. Most of the 75 studied food items remained in the same category from 2006 to 2017. Finally, our results show that, on average, the consumption exhibited by couples is shaped more strongly by female than male consumption behaviour. In addition, couples were found to consume more drinks and pricier foods than singles. Thus, our results highlight the importance of considering gender and the effect of coupling with the opposite gender when developing models, marketing strategies and further theories on consumption.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section ‘Theoretical Background’ presents a theoretical background on gendered eating in Switzerland and decision-making in couples and states the four hypotheses on the consumption patterns of couples tested in this study. Section ‘Data and Methods’ describes our data and empirical approach. Section ‘Results’ presents our results on food classification, a model on gender domination and the limitations of our approach. Section ‘Discussion and Implications’ discusses the results, and Section ‘Conclusions and Future Scope of Work’ outlines the conclusions reached in this study.

Theoretical background

Gendered eating in Switzerland

In Switzerland, there are relatively traditional gender stereotypes and roles, at least by European standards (Bornatici et al., 2020), and these are reflected in strongly gendered eating patterns. For example, Baur et al. (2022) found that males in Switzerland consumed more processed meat, red meat, alcoholic beverages and sodas, and less whole grains, vegetables and fruits, than females (according to Swiss-specific Nutritional Index data collected in August and September 2018). In fact, men have been found to consume meat products more frequently than women since early data were collected on this subject in 1992 (Eichholzer and Bisig, 2000; Steinbach et al., 2020; Tschanz et al., 2022). This indicates that Switzerland is following the typical trend in terms of this worldwide phenomenon (Rosenfeld and Tomiyama, 2021). However, this well-known fact should not distract us from the many other differences in eating behaviours between the genders, such as the observation that the energy-standardised dairy intake was higher for women than men (Inanir et al., 2020). Based on these existing findings on the differences in eating behaviours between the genders, it is possible to examine the changes that occur (if any) when persons identifying as men and persons identifying as women move into a joint household.

Decision-making in couples

Imagine a woman and a man, each with own shopping and eating habits, moving into a joint household. The most basic scenario would entail a mere addition of their habits. But how could we get more likely scenarios?

If the bargaining process during coupling is the interface between the economic and sociological perspectives of coupling, it is certainly a convenient starting point for approaching the question of how bonding affects food consumption from a socioeconomic view. Whereas economists use the ‘battle of the sexes’ concept as the basis for mathematical exercises to explore dominance and negotiation (Fudenberg and Imhof, 2006; Veller and Hayward, 2016), sociologists often remark on the still dominant role of men over women (El Shoubaki et al., 2021; Giner et al., 2022). This is illustrated in Table 1, which summarises studies that have analysed dominant positions in partnerships. Among the listed studies, only one study (Stein et al., 2014) was performed using panel data and had the potential to analyse the decision-making of couples over time. The other studies analysed data from a single year, a small number of observations and the responses of couples or coupled women, neglecting choices made by single women or any men under similar circumstances. The overarching limitation of these studies is that they did not compare the food consumption choices of couples and singles, albeit research has been conducted on the gender aspects of food (Sobal, 2005).

Hypothesis generation

Given the findings summarised in Table 1, it is tempting to hypothesise that men dominate the shopping and eating patterns of couples. However, consumption decisions are usually made in supermarkets or other retail outlets, and the same traditional distribution of roles that leads to men being dominant in so many realms of life results in women being responsible for grocery shopping (Melović et al., 2020; Van Milligan (2021); Yingli et al., 2018). This also applies in Switzerland, where discrimination in the workplace still pushes many women to become housewives. With this in mind, we developed Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 1: Persons identifying as women influence the food choices of heterosexual couples more strongly than persons identifying as men.

However, it would be too pessimistic to interpret coupling only as a power struggle. Gillis (2004), for example, described how the conjugal bond confers status and identity, and the symbolic creation of a joint ‘sweet home’ is an important step in the process. Notably, food consumption may be conceptualised as ‘social eating’ or a ‘social event’ (Douglas, 1972; Kauppinen‐Räisänen et al., (2013); Sobal and Bisogni, 2009). Therefore, moving into a household with a partner is likely to shift a part of the social experience of eating from the outer world of restaurants into the home, which led to the second hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2: The home food consumption of heterosexual couples exceeds the food consumption of single men and single women.

In addition to ensuring the intake of calories, eating has a strong social function that applies even more to drinks. While most peoples’ hydration needs can usually be met by drinking water, many other types of drinks have certain social functions in many societies. Weiner (1996), for example, explored the role of Coca-Cola in the United States. The concept is even more apparent for alcoholic beverages (Dunbar, 2013). The notion that couples are likely to utilise the social meanings of eating and drinking in their home life inspired Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 3: The relative consumption of drinks compared to solid food is higher in heterosexual couple households than in single households.

Lastly, the literature emphasises the existence of the ‘matching effect’ in terms of the volume consumed when eating with companions; that is, an individual’s intake corresponds to the social norms established by others rather than their personal needs (e.g. Bryan et al., 2019; Herman and Polivy, 2005; Levy et al., 2021). For example, a woman chooses foods of significantly lower caloric value when eating with a man than when eating with another woman (Young et al., 2009). It is likely that through the necessity or option of adding symbolic potential to their at home consumption, couples will attempt to add value to their purchases compared to those in single households. This value can be in terms of health or luxury. This led to the development of our final hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: The food consumed by heterosexual couples is processed less and more expensive than that consumed in single households.

Data and methods

Data

To assess our hypotheses, we analysed data described in more detail below:

-

Data type: Household consumption data collected over one month;

-

Data selection: Single households and mixed-gender couples’ households;

-

Data volume: 75 different food items (kilograms consumed);

-

Time: 1990–2017, and we used data from selected years.

We used disaggregated, agent-based, household yearly data from the Swiss Federal Statistics Office. This office annually asks randomly chosen households in Switzerland to provide data on the personal characteristics of household’s members and other factors, such as the volume and cost of foods consumed by the household (via food purchasing diaries). Therefore, the data we used were obtained from a reliable, randomised, observational survey on average monthly consumption over the year.

The data were available for 6000–12,000 participants yearly. Unfortunately, the data collection only allowed for identification of the participants’ gender as man (male) or woman (female); therefore, the data can only be analysed in a binary manner.

The survey was processed identically each time; however, the earlier data specified households and foods in less detail. We only studied the foods that matched precisely across the studied years, and we grouped the remaining foods into general categories. Hereafter, the foods described in the data before and after the grouping are called ‘disaggregated’ and ‘aggregated’ foods, respectively. This grouping allowed us to avoid a major reduction in the data volume. Declarations of ‘zero consumption’ were considered in all the estimations of this study. Across all the studied years, the households’ food diaries contained the details of the foods purchased by the households and not of foods that were consumed in restaurants or canteens.

We selected only households with one or two members. We took the gender of a household to be i) ‘man’ (denoted ‘M’ in the equations) when the household’s only member was declared to be a man, ii) ‘woman’ (denoted ‘F’ in the equations) when the household’s only member was declared to be a woman, and iii) ‘a man and a woman’ (also called a ‘couple’ throughout the manuscript) when the respondent declared that the household consisted of a man and a woman living together. We termed households ‘single’ when they consisted of one member. We termed households ‘a couple’ when they consisted of a man and a woman. We calculated the per-person consumption of each disaggregated food in each household (i.e. the per-person consumption in single households equalled the household consumption in the raw data, while the household consumption in couple households was halved to derive per-person consumption in couple households).

To avoid the inclusion of outliers, we excluded the 0.5% of households with the highest and the 0.5% of households with the lowest consumption per-person in the groups by disaggregated food and year. The final data set contained 4.43 million observations for 64,076 persons (7044 men, 10,888 women and 23,072 couples) and 75 aggregated foods (1860 combinations of disaggregated foods and years) observed in 41,004 households in one of several available years, namely 1990 and 2000–2017. The descriptive statistics for all the foods are presented in Supplementary Information. The descriptive statistics for beef and beer are shown in Fig. 1 as examples of the changes in consumption patterns noted within the household types and over the study period. It is easy to see that individuals in couples consumed more beef than singles and that women shaped the beer consumption patterns of couples.

To prepare the data for food classification, we aggregated personal consumption (c) in households h ∈ [1…H] in groups by the year of observation (t), the gender of the household g ∈ (“man”, “woman”, “a man and a woman”) and the aggregated type of food (\(\ddot \iota\)). For regression analysis, we calculated the average personal consumption in groups by a combination of disaggregated foods (\(\dddot \iota\)) and years and the gender of a household as follows:

Classification of the foods

We classified the foods consumed by couples into seven categories. The classification depended on gender domination, the synergy between the genders and the deviation in consumption from the average consumption of people in single households. We studied two genders: man and woman. Mid-position foods were foods that were consumed by couples at the same level, on average, as they would be consumed by two separate persons of opposite genders. Positive (negative) domination by gender N in the context of this study occurred when the average personal consumption in a couple increased (decreased) to the average consumption by gender N; that is, the consumption of a food was positively (negatively) dominated by gender N. Positive (negative) synergy foods were foods that couples consumed more (less) per-person than separate-household individuals of any gender. The zones of domination, synergy and mid-position have the same trends as consumption. The resultant classification is visualised in Fig. 2.

Notes. The blue, red and black lines illustrate the consumption by gender 1, gender 2 and their average consumption, respectively. The dashed lines illustrate the possible options for consumption by couples.

A robust difference in the consumption by gender was observed for gender-dependent foods (Fig. 2a), for which the dominance of a gender is graphically visible—the line for couples mainly lies in the zone of one of the genders. In the case of gender-neutral foods (Fig. 2b), the consumption by each gender was similar, reducing the gender domination zones to zero.

We then determined that if the average consumption per-person for couples, single men and single women exist and was yi,t, ci,M,t and ci,F,t, respectively, then we could compare them at each time t and for each food i = \(\ddot \iota\) (i.e. aggregated food), thus classifying the foods. A food was considered gender-neutral when ci,M,t ≈ ci,F,t, otherwise it was considered gender-dependent. To ensure the quantitative comparability between the foods and groups, we shifted from levels to relative values. Systems (3)–(9), shown below, were developed to describe the classification of food consumption by couples:

Methods

To quantify the average gender dominance in the food purchasing decisions made by the households, we used a simple linear regression with robust estimates. As the data did not allow for determining how much of each food was consumed by each person in a couple, we analysed the average consumption per-person in grams. For foods i and time t, we denoted the average consumption per-person for couples as yi,t (thus, we explain values such as the average per-person consumption of seafood in the year 1990 by couples), for single men as ci,M,t and for single women as ci,F,t, and the sum of consumptions by all the households with one and two members as ci,t. Similarly, ei,t represents the total expenditure on food for all the households with one and two members. We denoted the groups of foods using dummy variables dg, g ∈ {“processed”, “animal”, “liquid”}, with di,g equalling 1 when the food belonged to the category g, and equalling 0 otherwise. The purchase price pi,t was calculated as in Eq. (11), and the correlations between the consumption by couples and the described factors were calculated using the regression (12):

where α is a constant, εi,t is the error term (residuals) and βj denotes the correlations of interest. The magnitude and significance of the estimates of βj (i.e. \(\hat \beta _j\)) were the focus of the present study. As we used different foods in our model, we expected the value of constant α to be close to 0, and we did not include trend and time-fixed effects. The constant was included in the regression to enhance the reliability of the tests of the residuals and standard errors. For clarification, it may be helpful to note that the value of β1 and β2 would be 0.5, and the value of all the other coefficients would be 0, if the consumption by couples equalled the sum of individual male and female consumption.

Results

Classification of consumed foods

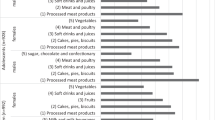

Single men consumed more pasta, drinks, sausages and canned and prepared fish and meat than single women, who had higher consumption of the remaining gender-dependent foods. For most of the foods, the consumption by two-gender households deviated from the average consumption by single men and women, giving direction to our food classification process. We classified the main foods into our devised categories, as shown in Table 2.

Only 23% of the food types were classified as ‘mid-position’; that is, the per-person consumption by people in heterosexual couples and the average consumption by two opposite gender single individuals were almost the same. These foods were beans and peas, cabbage vegetables, canned fruit, coffee and substitutes, cream, seafood, prepared fish and seafood, fruits, jam, non-alcoholic drinks, nuts, pears and quinces, rice, stone fruit, syrups, tea and vegetarian soy products. For most of the foods, gender-dominated or synergistic consumption was observed.

The types of foods that were consumed in a gender-dominated manner resembled the lists of ‘gendered’ foods (see Sobal, 2005, p. 137 for more details). The consumption of wine, beer, sausages and canned meat was positively dominated by men. In terms of this study, this suggests that the average per-person consumption by people in couples was the same as the average consumption by a man. The consumption of the following foods was positively dominated by women: apples, baby food, berries, butter, canned fruit, canned vegetables and mushrooms, cereals, egg, flours, grapes, ice cream, kitchen herbs, leafy vegetables, oils and fats, onions and garlic, soups and tomatoes. The consumption of these foods forms a slightly healthier dietary pattern than those dominated by men. Negative domination by men in couples resulted in lower consumption of bananas, cheese and curd, cocoa and chocolate, honey, lemons, mixed milk-based products and ready meals. Similarly, negative domination by women in couples led to lower average consumption of bread, canned fish, mineral water and pasta.

We found that meat consumption resulted from positive synergy in couples; that is, couples consumed more meat per-person than individuals of any gender in a single household. We could not estimate the distribution of this increase across the members of the household; that is, it is unknown whether a man in a couple consumed considerably more meat or whether the woman’s consumption increased. It is likely that a combination of both scenarios occurred due to the effects of ‘social eating’. Understanding this effect requires more studies of individual data.

Although meat is considered to be a ‘men food’ (e.g. Sobal, 2005), our results showed that single men did not have higher household meat consumption than single women in Switzerland (see Supplementary Information). Our results also showed that most of the studied meat types were gender-neutral foods. In other words, man-associated in-house meat consumption appeared to occur only in couple households or in a synergistic manner (see Supplementary Information). A similar positive synergistic effect was also observed for the consumption of gender-neutral milk and spirits and liqueurs.

A negative synergistic effect was noted for the consumption of taste essences, citrus, pastry, sugar and yoghurt. Except for the reduced consumption of sugar and several types of vegetables, the synergistic effect seemed to lead to less healthy diets, on average. Although women had slightly healthier diets and positively influenced the consumption of healthier foods by couples, single women consumed more gender-dependent foods than single men.

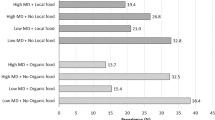

The dominance of gender

Women were found to dominate food purchasing decisions when they were coupled with men (Table 3). Forming the consumption of couples, the average consumption by single women weighted as 0.6, while that of men weighted as 0.38.

As the estimate for consumption by women had higher magnitude than the estimate for consumption by men, we could not reject Hypothesis 1. The constant was not positive; thus, Hypothesis 2 was rejected. In terms of per-person consumption, people in couples did not consume more than those in single households. The remaining difference in food consumption between single people and couples was accounted for by the higher consumption of liquids by couples; thus, Hypothesis 3 could not be rejected. Couples also preferred to consume more expensive foods compared to single people. Although this is an aspect of Hypothesis 4, couples did not consume less processed food than single households. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was partially rejected. Nevertheless, the symbolic meaning of expensive products seemed to influence the consumption patterns of couples (Carcano and Ceppi, 2010).

Limitations

The first important limitation of this study is that it was not possible to quantify the changes in, and distribution of, consumption among the individuals within couples using the available data. Such findings may be of interest to researchers who calculate and analyse environmental and health indicators for single and coupled individuals of different genders. We suggest that interested researchers use the dummy variable on gender coupled with the dummy variable on the presence of the opposite gender in a household in their food models and study these associations using data from individuals as well as individual products or consistent product groups.

The second limitation of our study is its territorial and time coverage. Swiss data may be representative of the gender relationships in developed European countries over the last 30 years. For other countries and cultures, it is plausible to develop similar studies to examine the gender relationships specific to their societies. Our classification and domination evaluation approach provides support for such context-specific investigations. With regard to the timeframe, the COVID-19 pandemic might have changed the lifestyles of consumers, the structure of supply, and inflation since 2020. Such shocks will likely contribute to changes in consumption patterns, at least in the short term.

Third, many factors were beyond the scope of our study. In essence, we aimed to systematically analyse ‘social eating’ by couples through the prism of gender and quantification of ‘gender domination’. Some of the important factors we did not consider are income, age, who does the grocery shopping and the selection bias of couples. That is, individuals’ social roles might interrelate with their consumption behaviours.

Finally, the most significant limitation of this study is that the data only allowed for a binary gender analysis. We hope that data collected in the future will permit finer differentiation within the gender spectrum.

Discussion and implications

This study used 4.43 million observations recorded by members of Swiss society over the last 30 years and generated a straightforward outcome: men and women consume food differently when they are in a joint household compared to living alone. This difference in consumption may be classified at the food-type level as (a) dominative, when the consumption by two people of opposite genders in one household is, on average, dominated by one person of one gender; (b) synergistic, when the per-person consumption by two people of opposite genders in one household is unexpectedly higher or lower than that of single people of any gender; and (c) mid-position, when the average per-person consumption in a household of two people of opposite genders is nearly the same as that of single people of the same gender. Most of the studied food types remained in the same of these categories from 2006 to 2017. The consumption of meat by couples has been influenced by a positive synergistic effect over the last 30 years, and only 23% of the studied foods fell into the mid-position category. Our results suggest that gender and the effect of coupling with the opposite gender should be considered when developing models and further theories on consumption.

Beyond the observation that coupling alters the choice of food for in-house consumption, three more conclusions can be drawn from our empirical investigation. First, food purchasing decisions are one of the few realms of life in which women show dominance over men, at least in Switzerland. Men still make more than one-third, but less than half, of the choices. Second, it can also be concluded that the consumption of drinks is higher in couple households compared to single households. Lastly, couples tend to choose more expensive foods than single men or women. These latter two findings confirm that coupling entails not only a power struggle but also bringing more socially loaded patterns into the household.

The findings of this study contribute to current debates within the fields of:

-

1.

food consumption and food choices made by couple households (e.g. Chan and Sobal, 2011; Hanson et al., 2007; Sobal et al., 2009; Sobal and Hanson, 2011) by providing quantitative estimates of how the average personal consumption of people in couples is shaped by the consumption by singles of many foods over decades;

-

2.

social eating (e.g. Brunner, 2011; Rodríguez-Pérez et al., 2020; Young et al., 2009) and gendered eating (Inanir et al., 2020; Steinbach et al., 2020; Tschanz et al., 2022) by classifying the food choices made by heterosexual couples;

-

3.

feminist studies (e.g. Avakian and Haber, 2005; studies in Table 1) by defining gender power in the area of food choice/purchase negotiation;

-

4.

psychological studies on eating behaviour (e.g. Stöckli et al., 2016; Weibel et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2021) by determining the contribution of coupling to food choice;

-

5.

the socioeconomics of food (Bhadra et al., 2023; Carson, 2017; Dai and Wu, 2023; Tyagi, 2023; Wu et al., 2021) by identifying robust food consumption patterns in a developed economy; and

-

6.

household dynamics by providing insight into how peoples’ needs and behaviours change during coupling, which is an important biological and survival constraint in population studies (e.g. Marin and Beluffi, 2018; Salotti, 2020).

Scholars working in these six fields may consider it important that women who live in a system in which they are structurally disadvantaged may be ‘compensated’ by taking a dominant position in terms of food purchasing decisions.

Given that we have classified the consumption of many main food types using social parameters, our findings may also be useful for promotional and marketing professionals in Switzerland (and perhaps other countries) who wish to target product promotions to people of a specific gender or couples. Our classification system and results may be tested for their generalisability to other countries and cultures.

Conclusions and future scope of work

Applying the concepts of dominance, synergy and mid-positioning to analyse the food consumption patterns of households offers insight into social and psychological behaviours that contributes to existing theories and enhances knowledge about human eating. Our results will be useful for the following groups:

-

1.

consumers who want to improve their diets;

-

2.

economists who investigate games and other forms of interaction between individuals of different genders. They may find empirical material in our study that highlights behavioural patterns in couples;

-

3.

scholars who model (food) consumption, social eating, human behaviour and (food) choice of couple households. Their research will benefit from the clear food-tailored relationships between the consumption by singles and the consumption by couples identified in this study.

-

4.

scholars in the field of feminist studies who wish to further examine this exceptional situation in which women’s power outweighs men’s power in a core area for health, the environment and the sustainability of the family and society;

-

5.

socioeconomists who theorise about and empirically analyse food consumption patterns around the world.

This identification and analysis of food consumption patterns will hopefully contribute to environmentally and personally friendly food consumption and to further studies on the role of interrelations between genders in eating.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the supplementary material.

References

Aletheia D, Doss C, Goldstein M-P, Gupta S (2021) Sharing responsibility through joint decision making and implications for intimate-partner violence: Evidence from 12 sub-Saharan African countries. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9760. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/36225

Avakian AV, Haber B (2005) From Betty Crocker to feminist food studies: Critical perspectives on women and food. University of Massachusetts Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vk2tn

Baker AH, Wardle J (2003) Sex differences in fruit and vegetable intake in older adults. Appetite 40(3):269–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0195-6663(03)00014-x

Baur I, Stylianou KS, Ernstoff A, Hansmann R, Jolliet O, Binder CR (2022) Drivers and barriers toward healthy and environmentally sustainable eating in Switzerland: Linking impacts to intentions and practices. Front Sustain Food Syst 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.808521

Bensemann J, Hall CM (2010) Copreneurship in rural tourism: exploring women’s experiences. Int J Gend Entrepreneurship 2(3):228–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566261011079224

Bhadra M, Gul MJ, Choi GS (2023) Implications of war on the food, beverage, and tobacco industry in South Korea. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01659-1

Bittman M, England P, Sayer L, Folbre N, Matheson G (2003) When does gender trump money? Bargaining and time in household work. Am J Sociol 109(1):186–214. https://doi.org/10.1086/378341

Bloodhart B, Swim JK (2020) Sustainability and consumption: what’s gender got to do with it? J Soc Issues 76(1):101–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12370

Bornatici C, Gauthier JA, Le Goff JM (2020) Changing attitudes towards gender equality in Switzerland (2000–2017): Period, cohort and life-course effects. Swiss J Sociol 46(3):559–585. https://doi.org/10.2478/sjs-2020-0027

Brunner KM (2011) Der Ernährungsalltag im Wandel und die Frage der Steuerung von Konsummustern. In: Ploeger A, Hirschfelder G, Schönberger G (eds) Die Zukunft auf dem Tisch. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-93268-2_13

Bryan CJ, Yeager DS, Hinojosa CP (2019) A values-alignment intervention protects adolescents from the effects of food marketing. Nat Hum Behav 3(6):596–603. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0586-6

Carcano L, Ceppi C (2010) Time to change: contemporary challenges for haute horlogerie. EGEA

Carson J (2017) Eating healthy or eating right. Nat Hum Behav 1(12):858–858. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0268-1

Chan JC, Sobal J (2011) Family meals and body weight. Analysis of multiple family members in family units. Appetite 57(2):517–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.07.001

Chriss JJ (2007) The functions of the social bond. Sociol Q 48(4):689–712. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2007.00097.x

Costescu DJ, Lamont JA (2013) Understanding the pregnancy decision-making process among couples seeking induced abortion. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 35(10):899–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1701-2163(15)30811-2

Dai X, Wu L (2023) The impact of capitalist profit-seeking behavior by online food delivery platforms on food safety risks and government regulation strategies. Hum Soc Sci Commun 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01618-w

Debreu G (1951) The coefficient of resource utilization. Econometrica 19:273

Debreu G (1954) Representation of a preference ordering by a numerical function. In: Robert TM, Coombs CH, Raiffa H (eds.) Decision processes, Wiley, pp. 159–167

Dekkers TD (2009) Qualitative analysis of couple decision-making. Dissertation, Iowa State University

Douglas M (1972) Deciphering a meal. Daedalus 101(1):61–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/20024058

Dunbar RIM (2013) The social function of alcohol from an evolutionary perspective. In: Abed R, John-Smith PS (eds.) Evolutionary psychiatry: current perspectives on evolution and mental health. Cambridge University Press

Fafchamps M (2008) Risk sharing between households. In: Benhabib J, Bisin A, Jackson MO (eds.) Handbook of social economics. Elsevier

Eichholzer M, Bisig B (2000) Daily consumption of (red) meat or meat products in Switzerland: Results of the 1992/93 Swiss Health Survey. Eur J Clin Nutr 54(2):136–142. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600907

Eika L, Mogstad M, Vestad OL (2020) What can we learn about household consumption expenditure from data on income and assets? J Public Econ 189:104163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104163

El Shoubaki A, Block J, Lasch F (2021) The couple business as a unique form of business: a review of the empirical evidence. Manag Rev Q 72(1):115–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-020-00206-5

Fudenberg D, Imhof LA (2006) Imitation processes with small mutations. J Econ Theory 131:251–262

Ghasemi A, Zahediasl S (2012) Normality tests for statistical analysis: a guide for non-statisticians. Int J Endocrinol Metab 10(2):486–489. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijem.3505. 10:486–489

Gibbons R (1992) A primer in game theory. Harvester Wheatsheaf

Gillis JR (2004) Marriages of the mind. J Marriage Fam 66(4):988–991

Giner C, Hobeika M, Fischetti C (2022) Gender and food systems: Overcoming evidence gaps. OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers 184. https://doi.org/10.1787/355ba4ee-en

Hanson KL, Sobal J, Frongillo EA (2007) Gender and marital status clarify associations between food insecurity and body weight. J Nutr 137(6):1460–1465. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/137.6.1460

Hayashi F, Altonji J, Kotlikoff L (1996) Risk-sharing between and within families. Econometrica 64(2):261–294. https://doi.org/10.2307/2171783

Herman C, Polivy J (2005) Normative influences on food intake. Physiol Behav 86(5):762–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.064

Inanir D, Kaelin I, Pestoni G, Faeh D, Mueller N, Rohrmann S, Sych J (2020) Daily and meal-based assessment of dairy and corresponding protein intake in Switzerland: Results from the National Nutrition Survey menuCH. Eur J Nutr 60(4):2099–2109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-020-02399-7

Kauppinen‐Räisänen H, Gummerus J, Lehtola K (2013) Remembered eating experiences described by the self, place, food, context and time. Br Food J 115(5):666–685. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070701311331571

Kornrich S, Brines J, Leupp K (2013) Egalitarianism, housework, and sexual frequency in marriage. Am Sociol Rev 78(1):26–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122412472340

Koval O (2020) Decision-making in couples: It takes two to tango. Dissertation, University of Stavanger

Law WK, Yaremych HE, Ferrer RA, Richardson E, Wu YP, Turbitt E (2021) Decision-making about genetic health information among family dyads: a systematic literature review. Health Psychol Rev 16(3):412–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2021.1980083

Levy DE, Pachucki MC, O’Malley AJ, Porneala B, Yaqubi A, Thorndike AN (2021) Social connections and the healthfulness of food choices in an employee population. Nat Hum Behav 5(10):1349–1357. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01103-x

Mann S, Loginova D (2023) Distinguishing inter- and pangenerational food trends. Agric Econ 11(10). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-023-00252-z

Marin F, Beluffi C (2018) Computing the minimal crew for a multi-generational space travel towards Proxima Centauri b. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1806.03856

McAdam M, Marlow S (2013) A gendered critique of the copreneurial business partnership. Int J Entrepreneurship Innov 14(3):151–163. https://doi.org/10.5367/ijei.2013.0120

Melović B, Cirović D, Backovic-Vulić T, Dudić B, Gubiniova K (2020) Attracting green consumers as a basis for creating sustainable marketing strategy on the organic market—Relevance for sustainable agriculture business development. Foods 9(11):1552. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9111552

Millman C, Martin LM (2007) Exploring small copreneurial food companies: female leadership perspectives. Women Manage Rev 22(3):232–239. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420710743680

Meier K, Kirchler E, Hubert AC (1999) Savings and investment decisions within private households: Spouses’ dominance in decisions on various forms of investment. J Econ Psychol 20(5):499–519. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:joepsy:v:20:y:1999:i:5:p:499-519

Mottiar Z, Quinn D (2004) Couple dynamic in household tourism decision making: Women as the gatekeepers? Dublin Institute of Technology. https://doi.org/10.21427/D72J3G

Mulamba KC (2022) Relationship between households’ share of food expenditure and income across South African districts: a multilevel regression analysis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9:428. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01454-4

Nash JF (1950) Equilibrium points in n-person games. Proc Natl Acad Sci 36(1):48–49. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.36.1.48

Pigou AC (1920, [1932]) The economics of welfare (1st & 4th ed.). MacMillan

Rempel LA, Rempel JK (2004) Partner influence on health behavior decision-making: increasing breastfeeding duration. J Soc Pers Relat 21(1):92–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407504039841

Rodríguez-Pérez C, Molina-Montes E, Verardo V, Artacho R, García-Villanova B, Guerra-Hernández EJ, Ruíz-López MD (2020) Changes in dietary behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak confinement in the Spanish COVIDiet study. Nutrients 12:1730. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061730

Rosenfeld DL, Tomiyama AJ (2021) Gender differences in meat consumption and openness to vegetarianism. Appetite 166:105475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105475

Salotti JM (2020) Minimum number of settlers for survival on another planet. Sci Rep 10:9700. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66740-0

Scanzoni L, Scanzoni J (1976) Men, women and change: A sociology of marriage and family. McGraw Hill

Shapley LS (1953) A value for n-person games. In: Kuhn HW, Tucker AW (eds.) Contributions to the theory of games, vol 2. The RAND Corporation

Sinclair R, Diamond J (2022) Basic food and drink price distributions transcend time and culture. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01177-6

Sobal J (2005) Men, meat, and marriage: models of masculinity. Food Foodways 13(1–2):135–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/07409710590915409

Sobal J, Bisogni CA (2009) Constructing food choice decisions. Ann Behav Med 38(S1):37–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9124-5

Sobal J, Hanson KL (2011) Marital status, marital history, body weight, and obesity. Marriage Fam Rev 47(7):474–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2011.620934

Sobal J, Hanson KL, Frongillo EA (2009) Gender, ethnicity, marital status, and body weight in the United States. Obesity 17(12):2223–2231. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2009.64

Stein P, Willen S, Pavetic M (2014) Couples’ fertility decision-making. Demogr Res 30:1697–1732. https://doi.org/10.4054/demres.2014.30.63

Steinbach L, Rohrmann S, Kaelin I, Krieger JP, Pestoni G, Herter-Aeberli I, Faeh D, Sych J (2020) No-meat eaters are less likely to be overweight or obese, but take dietary supplements more often: results from the Swiss National Nutrition Survey menuCH. Public Health Nutr 24(13):4156–4416. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980020003079

Stöckli S, Stämpfli A, Messner C, Brunner TA (2016) An (un) healthy poster: When environmental cues affect consumers’ food choices at vending machines. Appetite 96(1):368–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.034

Toro F, Serrano M, Guillen M (2019) Who pollutes more? Gender differences in consumptions patterns. Research Institute of Applied Economics Working Paper 2019/06:1/48. https://www.ub.edu/irea/working_papers/2019/201906.pdf

Tschanz L, Kaelin I, Wróbel A, Rohrmann S, Sych J (2022) Characterisation of meat consumption across socio-demographic, lifestyle and anthropometric groups in Switzerland: Results from the National Nutrition Survey menuCH. Public Health Nutr 25(11):3096–3106. https://doi.org/10.1017/s136898002200101x

Tyagi K (2023) A global blockchain-based agro-food value chain to facilitate trade and sustainable blocks of healthy lives and food for all. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01658-2

Valsecchi MC (2021) A dietary gender gap in ancient Herculaneum. Nat Italy. https://doi.org/10.1038/d43978-021-00107-5

Van Milligan H (2021) Mixed methods research into audience reception of ‘gay window advertising’. Wageningen University & Research

Varian H (1992) Microeconomic analysis, 3rd edn. Norton

Veller C, Hayward LK (2016) Finite-population evolution with rare mutations in asymmetric games. J Econ Theory 162:93–116

von Neumann J, Morgenstern O (1955, [1944]) Theory of games and economic behavior, 6th edn. Princeton University Press

Weibel C, Messner C, Brügger A (2014) Completed egoism and intended altruism boost healthy food choices. Appetite 77:38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.02.010

Weiner M (1996) Consumer culture and participatory democracy: the story of Coca-Cola during World War II. Food Foodways 6(2):109–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/07409710.1996.9962033

Wu J, Fuchs K, Lian J, Haldimann ML, Schneider T, Mayer S, Byun J, Gassmann R, Brombach C, Fleisch E (2021) Estimating dietary intake from grocery shopping data—A comparative validation of relevant indicators in Switzerland. Nutrients 14(1):159. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14010159

Yingli W, Touboulic A, O’Neill M (2018) An exploration of solutions for improving access to affordable fresh food with disadvantaged Welsh communities. Eur J Oper Res 268(3):1021–1039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2017.11.065

Young ME, Mizzau M, Mai NT, Sirisegaram A, Wilson M (2009) Food for thought. What you eat depends on your sex and eating companions. Appetite 53(2):268–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2009.07.021

Zhao Z, Gong Y, Li Y, Zhang L, Sun Y (2021) Gender-related beliefs, norms, and the link with green consumption. Front Psychol 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.710239

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M. and D.L. developed the study conceptualisation and design. Material and data preparation were performed by D.L. and S.M. Analysis was performed by D.L. The first draft of this manuscript was written by D.L. and S.M. S.M. supervised, proofread and commented on previous versions of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval

The authors confirm that this article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. The authors confirm that the data used in this research are not identifiable. Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

The authors confirm that this article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. The authors confirm that the data used in this research are not identifiable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Loginova, D., Mann, S. Sweet home or battle of the sexes: who dominates food purchasing decisions?. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 261 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02745-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02745-8