Abstract

Metaphor is an important tool for people to use in their perception of the world, but its representational forms vary across genres. Using Nvivo 12 plus as a tool, this study employs a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods to investigate the multimodal metaphorical representations, modal characteristics and cognitive rationales in the Sino-British co-produced documentary Through the Seasons: China. It has been discovered that: (1) Multimodal metaphorical representations in documentaries are found to be divided into two primary categories and five sub-categories. Implicit source-verbal and pictorial target is the primary way of representation for documentaries. (2) Various modes, including verbal mode, pictorial mode, verbal and pictorial mode, and implicit mode are employed in documentaries. However, the most commonly used modes are verbal and pictorial mode as well as implicit mode. The relationship between verbal and pictorial modes in the documentary is primarily characterised by juxtaposition and interpretation. (3) The documentary’s genre attributes and purpose, as well as the target audience’s physical and cultural experiences, are important cognitive justifications for the multimodal approach to metaphorical representation. This study further enriches the study of multimodal metaphorical representations and contributes to the theoretical refinement of multimodal metaphors. Additionally, it offers a theoretical reference for the development of dynamic multimodal discourses, such as documentaries, and aids in the improvement of audiences’ multimodal literacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The exponential advancement of multimedia technology has precipitated a profound transformation in the manner by which individuals acquire and disseminate information. The exclusive reliance on verbal communication as the primary means of information dissemination is no longer prevalent. Instead, there is a growing trend towards the creation of short videos, cartoons, films, and other forms of multimodal communication that integrate verbal language, pictures, sound, movement, and music.

Simultaneously, there has been a rise in multimodal discourse research, which is quickly gaining traction within the academic community. Early investigations into multimodal discourse cantered on the semiotic interpretation of intricate multimodal discourse through a social-functional perspective (Kress and Van Leeuwen, 2001; O’Halloran, 2015; Wang, 2019). In recent years, there has been an increasing emphasis on the study of multimodal discourse. Scholars have recently initiated research into the potential integration of multimodal discourse with other academic fields in order to tackle the challenge of interpreting non-verbal signs in the analysis of multimodal discourse (Forceville, 2007a; Jewitt, 2009). For instance, the incorporation of multimodal discourse analysis in conjunction with corpus linguistics (Bateman and Hiippala, 2017; Huang, 2015; Jewitt and O’Halloran 2016), metaphor studies (Jesús and Sanz, 2015; Ma et al., 2020; Pérez-Sobrino, 2017), and various other disciplines.

Multimodal metaphor research has both bridged the gap in researchers’ interpretation of the cognitive mechanisms of multimodal discourse and enabled cognitive linguistics to expand the scope of metaphor research beyond verbal mode to other modes such as pictures, gestures, and sounds. Current scholarly investigations on multimodal metaphor, both domestically and internationally, primarily concentrate on two key areas. Firstly, there is a significant emphasis on expanding the theoretical framework of multimodal metaphor. This involves exploring the potential integration of multimodal metaphor with visual grammar, conceptual blending theory, and other related theories. The aim is to enhance and refine the existing theory of multimodal metaphor. The second aspect involves examining the practical implementation of multimodal metaphor in order to validate the theory and expand its applicability. However, previous studies have mostly focused on the meaning construction and modal representation characteristics of multimodal metaphors in advertisements (De Los Rios and Alousque 2022; Pérez-Hernandez, 2019) and comics (Isabel, 2020; Lin and Chiang, 2015), while not enough attention has been paid to multimodal metaphors in dynamic videos such as documentaries.

Although documentaries dominated the early years of film, they were far less prominent than fictional films after 1908, until 1917, when they began to gradually rise in prominence and show rapid growth (Svilicic and Vidackovic, 2014). Documentaries have long been popular with audiences for their authenticity, objectivity, and knowledge. In recent years, especially in the post-epidemic era, documentaries have become an important means of constructing and communicating national images in countries around the world. Documentaries make use of multiple modes, such as pictures, verbal language, and sound, to stimulate the multiple senses of viewers in multiple ways, thus conveying information and winning their recognition. As an important category of multimodal discourse, it is increasingly important to study metaphors in documentaries. This study uses multimodal metaphor theory to analyse multimodal metaphorical representations in documentaries, reveal their cognitive rationale and modal characteristics, help people understand metaphors in documentaries accurately, improve their cognitive ability of multimodal metaphors, verify and expand the research on multimodal metaphorical representations, and provide inspiration for the research and practice of dynamic multimodal discourses such as documentaries.

Theoretical framework

Conceptual metaphor theory assumes that metaphors are pervasive in people’s lives, not only as a form of rhetoric but also as a tool for thinking and acting (Lakoff, 1993: 210). Traditional conceptual metaphor studies have focused on the exploration of the use of metaphors in language and have yielded fruitful results (Kazemian and Hatamzadeh, 2022; Rasse et al. 2020; Santibanez, 2010). However, as metaphor research in cognitive science has intensified, researchers have discovered that metaphors can be represented not only by verbal mode but also by other modes such as pictures, sounds, gestures, and tactile sensations. In this context, multimodal studies of metaphor have gradually emerged.

Forceville, a representative figure in multimodal metaphor research, first proposed the picture metaphor in 1996 and became the earliest advocate and practitioner of multimodal metaphor. Since then, Forceville and Urios-Aparisi (2009: 24) have multimodal metaphors as metaphors in which the source and target domains are represented separately or primarily by different modes. However, this definition has been criticised by some scholars for narrowly defining multimodal metaphors, limiting the scope of actual multimodal metaphor research, and being more difficult to operationalize (Gibbons, 2011: 81). Therefore, this study adopts multimodal metaphor in a broad sense: any metaphor that involves two or more modes in its construction can be called multimodal metaphor (Eggertsson and Forceville, 2009: 430).

The mode also exhibits variation based on the criteria used to define and classify it. Kress (2010 :79) posits that mode encompasses a range of symbolic resources that have the capacity to generate meaning. Language, as an ideational system, is one of these modes, alongside visual representations, physical gestures, and facial expressions. Forceville and Urios-Aparisi (2009: 22) propose that mode can be understood as a symbolic system through which individuals employ their senses to create and interpret meaning. They further categorise modes into visual, auditory, and gustatory modes based on the specific senses involved. However, the convergence of diverse communicative signs and modes within real-life multimodal discourse renders this classification overly broad and fails to support systematic and scientific investigation of multimodal research. Therefore, Forceville and Urios-Aparisi (2009: 23) further classified mode into nine distinct categories, including pictorial symbols, verbal symbols, sounds, and tastes, building upon the original classification. In the context of multimodal metaphors, the distinction in modes also plays a crucial role in determining their respective functions. For instance, the utilisation of pictorial mode has the ability to swiftly capture the audience’s attention and visually illustrate the source and target domains of multimodal metaphors. On the other hand, the verbal mode can aid in the interpretation or directly activate the source and target domains. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to conduct a thorough investigation into the representation of multimodal metaphors in documentary films.

Literature review

Researchers have primarily directed their attention towards investigating multimodal metaphors within static multimodal discourses, such as print advertisements (Feng and Wu, 2022; Pérez-Hernandez, 2019; Pérez-Sobrino, 2016) and cartoons (Abdel-Raheem, 2023; Bounegru and Forceville, 2011; El Refaie, 2013), during the initial stages. However, they have overlooked the examination of the dynamic characteristics of multimodal metaphors. In recent years, there has been a significant emphasis on the study of multimodal metaphors in dynamic multimodal discourse due to the rapid growth of new media (Bort-Mir et al. 2020; Ho, 2019).

Film, being a widely accessible and influential form of audiovisual art, has naturally emerged as an ideal platform for scholars to investigate the intricacies of multimodal metaphors (Gomez-Moreno, 2017). Most of the previous research has focused on examining the construction of multimodal metaphorical meanings in promotional films (Guan and Forceville, 2020; Liu and Li, 2022), animated films (Forceville, 2013; Prokhorov, 2021), and fictional films (Poppi and Urios-Aparisi, 2018; Thompson, 2020). For instance, Carroll (1996) posits that under equal circumstances, the audience can only perceive film metaphors and their related components if they possess salience. Kappelhoff and Müller (2011) argue that the utilization of expressive action in fictional films serves as the foundation for the generation and construction of multimodal metaphors. Coëgnarts and Kravanja (2015) conducted a further investigation into spatial-temporal metaphors in films, building upon previous studies that explored spatial-temporal metaphors in verbal and action modalities. Coëgnarts (2017) integrated conceptual metaphor theory and embodied simulation theory in order to analyse the conceptual meaning in films across three distinct levels: the conceptual level, the formal level, and the receptive level. Previous scholarly investigations into the construction of multimodal metaphorical meanings in film have provided the groundwork for the present study’s examination of multimodal metaphorical representations in documentary film.

Forceville (2007b) pointed out that the way metaphors are represented has an important influence on how people recognise and interpret metaphors. Thus, Forceville (1996: 108–148) was the first to classify picture metaphors in print advertising into four categories from the perspective of the spatial relationship between the source and target domains: metaphors with one pictorially present term (MP1), metaphors with two pictorially present terms (MP2), pictorial simile (PSs), and verbal-pictorial metaphors (VPMs). This classification model has informed and been widely adopted for subsequent studies of metaphorical representations. Thereafter, Forceville (2008 :464–469) revised the above classification model and proposed four classifications: hybrid metaphor, contextual metaphor, pictorial simile, and integrated metaphor. In addition, Hart (2017), in his study of war metaphors in news coverage pictures, proposed a fifth picture metaphor-holistic metaphor that complements Forceville’s classification of picture metaphors from the perspective of metaphorical mapping.

Feng (2011) proposed a classification scheme for the representations of multimodal metaphors, which consists of three categories: cross-modal mapping, mono-modal mapping, and multimodal mapping. Meanwhile, the author also provides a summary of the prevalent multimodal metaphorical representations found in political cartoons and advertisements. It is observed that cross-modal mapping is a frequently employed metaphorical mapping in political cartoons. Additionally, individuals are required to discern the significance and worth of pictures with the aid of language. Multimodal metaphorical representations of verbal source-pictorial target and verbal mapping- picture example target are more common in advertisements. Since then, Yu (2013) and Lan and Zuo (2016) have conducted revisions and expansions on Feng’s (2011) multimodal metaphorical representation. Their studies have further confirmed that the pictorial source-verbal target is the most prevalent form of multimodal metaphorical representation found in news cartoons. In contrast to Feng’s (2011) classification of multimodal metaphor mappings based on the modal characteristics, Yu (2013) categorises the mappings of multimodal metaphors into two dimensions: static-dynamic latitude and concrete-abstract latitude. This classification takes into account the levels of the mapping modality and the mapping content. Lan and Zuo (2016), on the other hand, added implicit mapping to Feng ’s (2011) classification of three multimodal metaphorical representations. Bolognesi and Strik Lievers (2020) point out that the typical structure of metaphors in advertisements is to take the product as the target domain of the metaphor and to use pictures to represent it. This observation highlights the existence of variations in the representation of multimodal metaphors across different genres. It also underscores the importance of investigating the distinctive features of multimodal metaphorical representation within various genres.

In summary, multimodal metaphors in dynamic multimodal discourse are now gradually gaining the attention of scholars, providing a reliable reference for the advancement of this study. The existing body of research on the generation and meaning construction of multimodal metaphors in films is extensive. However, there has been a lack of scholarly attention given to the representation of multimodal metaphors. Most studies have focused on the representation of multimodal metaphors in advertising and cartoons, neglecting the representation of multimodal metaphors in documentaries. In this research, a comprehensive approach incorporating both qualitative and quantitative methods is employed to investigate the multimodal metaphorical representations found in documentary films. The aim is to uncover the cognitive rationale behind these representations and analyse their modal characteristics.

Research corpus and Methodology

This research study centres on the examination of multimodal approaches to metaphorical representation in documentary films. The primary objective of this study is to address the following questions:

-

(1)

How do the modes employed in the documentary coordinate to represent the multimodal metaphor? What are the main modes of representation?

-

(2)

What are the modal characteristics of these multimodal metaphorical representations?

-

(3)

Why do they present such features and representations?

This study utilises the Sino-British co-produced documentary “Through the Seasons: China” as the primary research corpus. The video corpus can be accessed for free on the Youku website (https://youku.com/). The documentary was released in both the UK and China in January 2022 and was recognised by the General Office of the State Administration of Radio and Television of China in the first quarter of 2022 as an exceptional online audiovisual production in August of the same year. The documentary is structured into three episodes, with a total duration of approximately 150 min, and exhibits a wealth of metaphors. Each episode narrates the tale of a Chinese individual associated with a distinct Chinese intangible cultural heritage, namely the twenty-four solar terms. This series has garnered significant acclaim from global viewers, serving as a noteworthy illustration of successful international co-production in portraying the rich cultural narrative of China.

International co-productions mainly refer to the collaboration between two or more companies or governments from different countries to produce a film or program. In these partnerships, each party has an equal voice and the right to distribute the program in their respective markets (Hoskins et al. 1997; Parc, 2020a). As a result, producers from different countries in a co-production can leverage their respective strengths to create the best possible film (Parc, 2020b). This is achieved by sharing the financial burden of film production, receiving support or subsidies from local governments, adopting more advanced filming techniques, creativity, and international thinking from partners, and better capturing the preferences of international audiences. These attributes reduce or eliminate cultural discounting and facilitate the international dissemination of co-productions (Hoskins and Mcfadyen, 1993). In the case of domestically produced films, not only do the producers have to bear the production costs alone, but their filming methods and production styles are also subject to their own standards. At the same time, the absence of an international perspective makes it challenging for localised productions to attract international audiences and does not facilitate the global distribution of films. The diversity of participants in international co-productions strikes a good balance between localisation and internationalisation, making them not only more accessible to domestic and international audiences but also an effective medium for promoting a country’s image in a culture dominated by others (Bergfelder, 2000; Taylor, 1995).

This study is structured into three distinct phases: the identification of multimodal metaphors, the labelling of multimodal metaphorical representations, and the subsequent analysis and discussion of the obtained results. Firstly, this study utilises Forceville’s (2008: 469) criteria for identifying multimodal metaphors in documentary films. The identification process involves the following steps: (1) Analysing the contexts in which the two phenomena occur and assessing whether they pertain to distinct domains. (2) Two distinct phenomena can be identified as the source domain and the target domain, respectively, and can be represented in the format A IS B. (3) The inquiry pertains to whether the construction of the semantic interpretation of the relationship between A IS B is concurrently depicted by two or more symbol systems, sensory modalities.

In the process of metaphor identification, researchers commonly depend on intuition to make assessments regarding specific metaphors. Hence, it is inevitable that there will be a certain level of subjectivity in the recognition outcomes, which poses a significant challenge in contemporary metaphor research (Lan and Zuo, 2016). To enhance the scientific rigor and credibility of metaphor identification, the present study adopted the method proposed by Cameron and Maslen (2010). Additionally, a second researcher specialising in multimodal metaphors was invited to collaborate in the identification, negotiation, and resolution of any disagreements pertaining to multimodal metaphors found in documentaries. The author of this research, along with another scholar specializing in metaphor analysis, employed the Nvivo12 plus software tool to individually detect multimodal metaphors within the documentary video corpus. The findings indicated that the level of agreement between the coding reliability tests conducted by the two researchers was 88.28%, with a mere 17 instances of disagreement observed in the analysis of metaphors. The researchers reached a consensus on an additional 11 metaphors out of the initial 17 through consultation, while discarding the remaining 6 metaphors due to their inability to agree upon them. In this study, a comprehensive analysis was conducted using the Nvivo12 plus tool to identify and label a total of 139 multimodal metaphors. These metaphors were expressed in the form of “A IS B” to facilitate their categorisation and analysis.

Secondly, Nvivo12 Plus serves as a tool for the classification and encoding of the identified multimodal metaphors in relation to their respective representations. The following details are provided: (1) open coding is conducted. The modalities of the identified multimodal metaphors in the source and target domains have been identified, and the original information points are marked (The target domain and source domain are marked with A1 and B1 for linguistic modalities, while the target and source domains are marked with A2 and B2 for pictorial modalities). (2) Axical encoding is carried out. According to the original information points identified in the open encoding, the marked multimodal metaphorical representations that have been marked are grouped together in classes. For instance, various types of encoding are employed, such as A2B1 type, A1B2 type, A1B1B2 type, etc. (3) Selective encoding is carried out. The nodes of the axical encoding are further integrated to extract five categories of cross-modal mapping (CRM), mono-modal mapping (MOM), multimodal mapping (MUM), single-domain implicit mapping (SIM), and dual domain implicit mapping (DUM). Subsequently, the first-level nodes of explicit multimodal metaphor representation (EXM) and implicit multimodal metaphor representation (IMM) are obtained. Some examples are provided here to demonstrate the process of encoding multimodal metaphorical representations.

-

(1)

Open coding: In the preceding step, the researcher identified the multimodal metaphor depicted in Fig. 1 as “the community is a tree”. Combined with the specific representation of this multimodal metaphor in Fig. 1, it is evident that the target domain of “community” is depicted through the verbal mode and is marked as A1. On the other hand, the source domain is represented by the pictorial modality, which is labelled as B2. Thus, the multimodal metaphor can be labelled as A1 is B2.

Fig. 1: The community is a tree (cross-modal mapping; explicit multimodal metaphor representation)(from the documentary Through the Seasons: China). -

(2)

Axical coding: Ascribe this multimodal metaphorical representation mode to the higher-level node A1B2 based on the labelling of it in the previous open coding step.

-

(3)

Selective coding: Based on the representation type of this multimodal metaphor A1B2 in the axical coding, it is further integrated into the higher-level node cross-modal mapping (CRM). Finally, they are clustered under a first-level node-explicit multimodal metaphor representation (EXM) based on their mapping characteristics.

-

(1)

Open coding: In the preceding stage, the multimodal metaphor depicted in Fig. 2 is recognised as “tea trees are humans”. This multimodal metaphor is shown in Fig. 2, wherein the target domain “tea trees” is represented by both verbal and pictorial modes, denoted as A1A2. The source domain of “humans” is not explicitly represented through either verbal or pictorial modes, but rather it is implied within specific contexts. In the present study, the implicit source domain is consistently denoted as B, while the implicit target domain is denoted as A. Thus, the multimodal metaphor can be labelled A1A2 is B.

Fig. 2: Tea trees are humans (Single-domain implicit mapping; implicit multimodal metaphor representation) (from the documentary Through the Seasons: China). -

(2)

Axical encoding: Based on the labelling of this multimodal metaphorical representation mode in the previous open coding step it can be attributed to the higher-level node A1A2B.

-

(3)

Selective coding: The multimodal metaphor A1A2B, represented in the axical coding, is integrated into the higher-level node of single domain implicit mapping (SIM). Finally, based on the mapping characteristics, these elements are subsequently grouped into the first-level node known as implicit multimodal metaphorical representation (IMM).

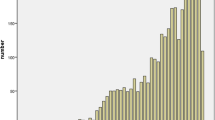

As shown in Table 1, this documentary has 139 multimodal metaphorical representations, five multimodal metaphorical representation subcategories, and two multimodal metaphorical representation categories. Among them, the number of single-domain implicit mapping leads in all issues of the documentary, with 26, 40 and 39, respectively. The number of mono-modal mapping is second only to the number of single-domain implicit mapping, which are located in the second place in each issue of the documentary, with 12, 7 and 6, respectively. The frequency of occurrences of different representational subcategories in each issue of the documentary varies. For example, dual domain implicit mapping appears only in issues 2 and 3, multimodal mapping appears only in issues 1 and 2, and cross-modal mapping appears only once in issue 1. It is evident that documentaries on this cultural topic employ a wide range of multimodal metaphorical representations. Among these representations, the implicit representation category emerges as the most prevalent, with the subcategories of single-domain implicit mapping and mono-modal mapping being the most frequently employed.

Finally, the results of the annotation are analysed and discussed. This study primarily focuses on conducting a case study analysis of the subcategory that occurs most frequently within each category of multimodal metaphorical representations. It aims to summarise the patterns, modal characteristics, and cognitive rationale underlying multimodal metaphorical representations in documentaries.

Research findings

Through meticulous observation and comprehensive analysis of 139 multimodal metaphors presented in the documentary, the author categorises the representations of these metaphors into two distinct categories: explicit representations and implicit representations. Explicit representations can be further categorised into three types: cross-modal mappings, mono-modal mappings, and multimodal mappings. This classification aligns with the categorisation proposed by Feng (2011). Implicit representations can be categorised into two types: single-domain implicit mappings and dual domain implicit mappings. One of the implicit representations in the field of metaphor studies is the dual domain implicit mapping, which can be seen as an equivalent to the contextual metaphor proposed by Forceville (2008). This concept complements the classification of implicit mappings put forth by Lan and Zuo (2016). These five models can be further subdivided into eight sub-models, as illustrated in Table 2. As evident from the data presented in Table 2, this classification emphasises the representation of multimodal metaphors by considering the mapping characteristics of such metaphors and the modal configurations of the source and target domains. In comparison to previous classifications by Feng (2011) and Lan and Zuo (2016), this classification provides a comprehensive summary of multimodal metaphor representation.

As can be seen from Table 2, the number of explicit representations in the documentary is 29 in total, accounting for 20% of the total multimodal metaphors in the documentary, mainly containing three categories of cross-modal mapping, mono-modal mapping and multimodal mapping. Among them, the number of both cross-modal mapping and multimodal mapping is only 2, while the number of mono-modal mapping is 25, accounting for 18%. In contrast, the number of implicit representations in the documentary is as many as 110, accounting for 80% of the total multimodal metaphors in the documentary, mainly containing 2 categories of single-domain implicit mapping and dual domain implicit mapping. Among them, single-domain implicit mapping account for the largest proportion, 76%, while the number of dual domain implicit mapping is only 5, accounting for less than 5%. However, due to the space limitation of the article, only the most frequently occurring sub-models under each model are discussed in detail in this study.

Cross-modal mapping

Among the 139 multimodal metaphors identified in the documentary, a mere 2 instances were found to be cross-modal mappings, representing a mere 1% of the overall count. Cross-modal mapping primarily pertains to the phenomenon wherein the source and target domains of multimodal metaphors are represented through distinct modes. The model can be further subdivided into two sub-models: verbal source-pictorial target and pictorial source-verbal target.

Hani represents one of the ethnic minorities in China, characterised by its distinctive customs and lifestyles. The narration of Picture 1 in Table 3 recounts the narrative of Chen Xi Niang, a Hani man, and his daughter, who have dedicated themselves to promoting Hani music for an extended period. This story highlights the Hani people’s commitment to their traditional way of life cantered around rice cultivation, providing the audience with insights into the rice terrace culture and the distinctive music culture of the Hani community. The linguistic modalities employed in Pictures 2 and 3 in Table 3 serve to communicate the discourse of Chen Xi Niang, a member of the Hani community, to the audience through both oral (auditory) and written (visual) language. Among them, “community” activates the concept of people and “rooted” activates the concept of plant. The connection between these two concepts is established using the conventional metaphor of “PEOPLE ARE PLANTS”, wherein the interdependence of humans on the land is compared to the rootedness of plants in the soil. According to Lakoff and Turner (1989: 16), a base metaphor is part of a more general base metaphor. The linguistic modality presented in Table 3 serves to directly activate the base metaphor “COMMUNITY IS PLANT”, which is primarily derived from the more general base metaphor “PEOPLE ARE PLANTS”.

Picture 1 in Table 3 shows Chen Xi Niang and his daughter standing under different trees playing Hani music. The standing trees and the people standing under the trees seem to be one in the picture, which intuitively gives people a visual suggestion that the people are the trees. Picture 2 in Table 3 is a scene of Hani people planting rice in a field. From afar, the people standing in the field and working sporadically look like the tree rooted in the field not far away. This scene is not only a display of Hani rice cultivation culture but also a further visual implication of the metaphor of “PEOPLE ARE TREES”. Pictures 1 and 2 in Table 3 both visually suggest to the viewers the “PEOPLE ARE TREES” metaphor based on the visualised physical characteristics of trees. According to the principle of salience (Kress and Van Leeuwen, 2021: 182), the source domain “tree” in Picture 3 of Table 3 attracts the viewer’s attention in terms of shape, size and colour, and visually highlights the source domain “tree”. In relation to their shape and size, the clusters of trees depicted in Picture 3 in Table 3 encompass over fifty percent of the total image. The remaining portion of the image showcases community dwellings partially concealed by the surrounding foliage, alongside terraced fields and sporadic trees interspersed throughout the terraces. In terms of the proportion of each element in the whole picture, the trees occupy the largest proportion. According to Kress and Van Leeuwen (2021: 211), the salience of an element in a picture is directly proportional to its visual weight. Therefore, the source domain “tree” exhibits a significant level of salience in this context and is visually emphasized. In Picture 3 of Table 3, the dominant colour is green, which is also the primary colour of the lush trees. This further emphasises the association between the source domain “tree” and the colour green.

In addition, the results of some scholars’ research on tree metaphors and Chinese traditions about tree culture also help people to further clarify the source domain as a tree. Based on the theory of Idealized Cognitive Model, Zhang (2018) argued for the rationality of the metaphor of “PEOPLE ARE TREES”, pointing out that the metaphor has three main modes of expression: evaluation mode, functional mode and growth mode. Among them, the functional mode refers to the relationships and roles between the components of the tree as perceived by people, including the metaphorical mode based on the external shape and internal characteristics of the tree and the metaphorical mode based on the functional characteristics of the constituent parts of the tree. For instance, the vertical external characteristics of a tree can be employed to define an individual’s upright stance. This metaphorical pattern also supports the analogy in Pictures 1 and 2 of Table 3 between the visualisation of the shape of the tree and the person standing under the tree playing music and the person standing in the field, thus visually suggesting to the viewers that the metaphor of “PEOPLE ARE TREES” is established. Metaphorical patterns based on the characteristics of the constituent parts of a tree mainly include metaphors based on characteristics related to roots (In Chinese, it’s called gen), trunk, leaves and branches. For example, the roots of the tree are constantly expanding downwards to provide nourishment for the growth of the tree. These expanding and rooting features of tree roots become the basis for the metaphor of phrases such as “root on, root about, root amongst”. Combined with the results of this research, it can be seen that the verbal modality “We cannot forget where our community is rooted” in Table 3 of this study can activate the source domain “tree”.

China is a large agricultural country with a farming culture that goes back thousands of years. Due to the low level of productivity, people in the ancient times had insufficient knowledge of natural phenomena and were unable to conquer them, thus giving rise to the worship of nature, which mainly included the sun, the moon, thunder and lightning, the land, trees, animals, mountains and rivers, and so on. Among these cultural practices, the veneration of trees has emerged as a distinctive tradition within Chinese culture. In the realm of tree culture, a rich tapestry of myths, legends, historical narratives, and religious customs exists, all intricately intertwined with the significance of trees. Moreover, trees are often personified, serving as symbols or metaphors to convey profound philosophies of existence and human experience, including navigating the complexities of the world and embracing one’s humanity. For example, “Shen qi gen, gu qi di, chang sheng jiu shi zhi dao ye” (to make the roots of a tree stable and not easy to be shaken) (Chen, 2002). As a result, there are many Chinese idioms related to trees. Hao (2019) points out that in Chinese tree idioms, people often use the relationship between tree leaves and roots (In Chinese, it’s called gen) as a metaphor for the close relationship between individuals and their families, hometowns, and clans, such as the metaphor of gen shen ye mao (When the roots are deep, the branches flourish) for the prosperity of the family, the metaphor of kai zhi san ye (After planting a sapling, it grows into a huge tree) for the transmission of ancestral lineage, and the metaphor of luo ye gui gen (Dead leaves that fall to the roots of trees) for the wanderer’s fondness for his hometown and native land. The metaphors of Chinese word gen (roots) idioms are the most numerous among the tree idioms, and the idiomatic expression “zha xia gen” (Roots grow downwards) is often used to simulate going deeper and laying a solid foundation. This research result further confirms that the linguistic modality “We cannot forget where our community is rooted” in Table 3 of this study can activate the source domain “tree”. In addition, another unique Chinese culture, root culture, is derived from the Chinese tree culture, which mainly refers to the Chinese people’s identity and emotional belonging to their country, nation, hometown, land, ancestors and culture. Wang (1991) highlights the multifaceted nature of the Chinese term “gen” (root), which encompasses various connotations. Apart from its fundamental biological significance, it also represents the origin and continuation of life, as well as an individual’s place of birth, ancestral village, and source of identity. He emphasised that the Chinese nation is a people with a strong gen (root) consciousness, and divided the Chinese gen (root) consciousness into five categories using phrases related to Chinese gen (root), such as “luo ye gui gen”, “luo di sheng gen”, and “wen zu xun gen”. Combining the linguistic modality “We cannot forget where our community is rooted” with the synchronised Chinese subtitle “Wo men bu neng wang le wo men de gen” in Table 3, it can be determined that the purpose here is to emphasise the Hani people’s “gen (root) consciousness”. Therefore, based on the Chinese gen (root) culture tradition and the linguistic and pictorial modalities in Table 3 of this study, it can be concluded that “community” is compared to “tree” here is to emphasise the Hani people’s unwillingness to leave the land where they were born and raised in order to earn more money, which highlights the Hani people’s love for their native land and their close relationship with it.

Therefore, when examining the linguistic and pictorial modalities presented in Table 3, it becomes evident that the linguistic modality mainly activates the metaphor of “COMMUNITY IS PLANT” and effectively highlights the target domain of “community” through the utilisation of Chen Xi Niang’s words. The utilisation of the pictorial modality in this context implies the metaphor “PEOPLE ARE TREES” through the visual depiction of tree shapes and the use of colour highlights. This visual presentation effectively conveys the source domain of “tree”. However, if we want to further specify the source domain as “tree”, we need to take into account the cultural background of China and the existing research results of other scholars on tree metaphors. As previously stated, several scholars have provided evidence to support the activation of the metaphor “PEOPLE ARE TREES” through the use of phraseological metaphors such as “root on, root about, root amongst” and the Chinese phrase “zha xia gen”. This provides corpus support for the fact that the linguistic modality “We cannot forget where our community is rooted” can activate the metaphor “PEOPLE ARE TREES” in Table 3. The identification of the source domain of the metaphor in Table 3 can be attributed to the combination of the visual resemblance between the shape of a tree and a human being, as well as China’s distinct cultural tradition of gen (root). Therefore, the source domain of the metaphor can be identified as “tree” once again. At this juncture, the construction of the multimodal metaphor “THE COMMUNITY IS A TREE” can be achieved by considering the linguistic modality, pictorial modality presented in Table 3, the research findings of Chinese scholars on Chinese tree culture and tree metaphors, and the enduring tradition of China’s gen (root) culture.

Mono-modal mapping

Mono-modal mapping refers to the phenomenon where both the source and target domains are represented in the same mode, while the other modes serve as auxiliary modes for interpretation and exemplification in the construction of multimodal metaphors. The documentary contains a total of 25 multimodal metaphors, which account for 18% of the overall metaphors. These metaphors can be further categorised into two sub-models: verbal mapping-picture example source and verbal mapping-picture example target. In the verbal mapping-picture example source sub-model, both the source and target domains are represented in the verbal mode, with the picture serving as an example of the source domain. Similarly, in the verbal mapping-picture example target sub-model, both the source and target domains are represented in the verbal mode, with the picture playing a supporting role as an example of the target domain. The latter sub-model is more prevalent in documentary films compared to the former. This can be attributed to the discursive features of documentaries, which prioritize authenticity and the goal of enabling the audience to comprehend the real world through visual representation.

Table 4 presents the depiction of the Yangtze River wetlands in China as portrayed in the documentary. The source and target domains are represented through verbal mode, constructing the metaphor of “YANGTZE RIVER WETLANDS ARE SPONGES”. Pictures 1 and 2 in Table 4 show the pictures of the Yangtze River wetlands in the distant and close up shots respectively, giving the audience an intuitive visual perception of the “Yangtze River wetlands” and complementing the verbal mode. As widely acknowledged, sponges are characterised by their porous nature, which enables them to exhibit excellent water absorption properties. The metaphorical mapping of the sponge’s characteristic onto the target domain of the “Yangtze River wetland” serves to emphasise the water absorption function of the wetland. The sponge absorbs sewage to help people clean their goods, while the wetland absorbs flood water to reduce the damage caused by downstream floods.

Multimodal mapping

Multimodal mapping primarily pertains to the coexistence of verbal and pictorial mapping, wherein both verbal and pictorial modes are utilised to represent the source and target domains simultaneously. The documentary contains two instances of multimodal metaphors, which fall under the category of multimodal mapping. These metaphors account for a mere 1% of the overall content, which can be attributed to the specific characteristics of the documentary genre. In this genre, it is challenging to effectively represent both the source and target domains simultaneously in all directions.

In Table 5, the account of Li Chunyu, the founder of the migratory bird rescue hospital established by volunteers, is presented in conjunction with the narrative provided in Picture 1. The verbal mode is utilised to represent or activate the source and target domains, resulting in the construction of the metaphor “WILD ANIMALS ARE BABIES.” This metaphor reflects the enduring human inclination to provide protection and care for animals. Pictures 1 and 2 in Table 5 illustrate Li Chunyu and a group of volunteers offering compassionate care and medical treatment to injured migratory birds, treating them as if they were their own. This statement further strengthens the metaphor of “WILD ANIMALS ARE BABIES” by employing visual imagery. Hence, the verbal and pictorial modes work in tandem to create a multimodal metaphor of “WILD ANIMALS ARE BABIES,” thereby enhancing each other and fostering a more profound comprehension of China’s principles regarding animal conservation and nurturing.

Single-domain implicit mapping

Single-domain implicit mapping primarily pertains to multimodal metaphors in which the source or target domains are not explicitly depicted and instead rely on the context and the audience’s encyclopedic knowledge to infer the implicit source or target domains. The documentary contains a total of 105 multimodal metaphors, which account for 76% of all the multimodal metaphors identified. These metaphors can be further divided into two sub-models: implicit source-verbal target-pictorial supplement; implicit source-verbal and pictorial target. The second sub-mode exhibits the highest percentage of single-domain implicit mappings. This finding suggests that the documentary aims to enhance the comprehension of the relatively abstract Chinese culture among international audiences. To achieve this, the documentary primarily employs verbal and pictorial modes to interpret and present Chinese culture within the target domain.

Chinese tea culture boasts a profound history spanning thousands of years. By employing tea as a medium, it serves as a conduit for the dissemination and embodiment of China’s abundant spiritual culture. The challenge lies in effectively conveying the essence of Chinese tea culture to the audience within the constraints of a limited time frame. The documentary “Through the Seasons: China” anthropomorphises the “tea tree” in the target domain by employing verbal mode. This technique endows the tea tree with human abilities and characteristics, enabling it to keep the earth green, hide in the mountains, meet with humans, change people’s lives, take on life, be respected and protected, etc. Picture 1 to Picture 5 in Table 6 display various images of tea trees captured from different angles, which complement the verbal mode. Up to this juncture, the target domain “tea tree” is represented in both verbal and pictorial modes, while the metaphorical source domain “human” is never represented directly and necessitates audience inference based on the given context.

Dual domain implicit mapping

The concept of dual domain implicit mapping primarily pertains to the absence of direct representation for both the source and target domains in multimodal metaphors. The construction of such metaphors relies heavily on contextual cues and the audience’s encyclopaedic knowledge. Only five multimodal metaphors in the documentary are mapped in this way, accounting for only 4% of the total number of metaphors. It is possible that the heavy reliance on audience inference in such mapping may result in cognitive bias during the communication process. This is particularly evident when considering the differences in cultural background and knowledge level among the audience. Consequently, this approach may not effectively achieve the communication objectives of the documentary.

China has both a diverse material culture and a rich spiritual culture. While material culture can be represented directly in the material medium in documentaries, the abstract nature of spiritual culture makes its presentation in documentaries more complicated, which leads documentaries to adopt a dual domain implicit mapping approach to describe China’s national spiritual culture. The verbal modes “improve” and “highest” in Table 7 help the audience to infer the metaphor of “GOOD IS UP “ from the specific context (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980: 16). The combination of the images of Pictures 1 and 2 in Table 7 shows a large number of engineers building railroads for people in remote areas in order to improve their living standards. The pictorial mode allows viewers to witness the efforts of the Chinese people to realize the metaphor “GOOD IS UP “, showing the selfless dedication of the Chinese people and their strong sense of family. The juxtaposition of Pictures 3 and 4 in Table 7 demonstrates a significant advancement in rocket construction by Chinese scientists, marking a breakthrough achieved after a three-year effort. This visual representation showcases the realisation of the metaphor “GOOD IS UP” in a pictorial mode, while also conveying the innovative spirit of Chinese scientists who fearlessly strive for excellence despite the challenges they face. The verbal and pictorial modes complement each other to construct the multimodal metaphor “ GOOD IS UP “.

The understanding of metaphor is a multifaceted and open-ended process, influenced by the viewer’s heavy dependence on both their physical and cultural experiences (Forceville, 1996). This finding suggests that the cognitive processing of multimodal metaphors varies across different audiences, indicating that the role of pictorial mode and verbal mode in cognition may differ. For instance, certain multimodal metaphors may employ the pictorial mode to enhance their metaphorical capacity by presenting both the vehicle and the topic. However, it can be challenging for certain viewers to fully comprehend the metaphor solely based on the pictorial mode (Gonçalves-Segundo, 2020). For individuals with diverse cultural backgrounds, the inclusion of verbal modal cues is not essential for the comprehension of multimodal metaphors. However, individuals with limited cultural exposure possess a significant requirement for verbal modal cues in order to comprehensively grasp multimodal metaphors (Bounegru and Forceville, 2011). Specifically, within the context of the multimodal metaphor “Good is up,” the concept is depicted as follows: The verbal mode “improve” emphasises the act of raising people’s standard of living. The term “highest” in the verbal mode emphasises the outcome of upgrading the technical level, specifically, the technical level of rocket construction has been constantly upgraded to the highest level, in the upper class. Both words imply a horizontal upward lift, giving the viewer the perception of a vertical upward lift, which indirectly activates the source domain “up”. Both of these words imply the upward elevation of the level, offering the audience a cognitive perception of vertical ascent and indirectly invoking the conceptual domain of “up”. The concept of directionality rising in metaphor has been linked to several positive connotations (Kövecses, 2010). The construction of railways for the betterment of society and the advancement of rocket construction to support the country’s space development are actions and occurrences that are associated with positive implications, as indicated in Table 7. The metaphor of “GOOD IS UP” can be deduced from the various elements present in the verbal mode.

The metaphor of “Good is up” falls under the category of orientation metaphors within the framework of conceptual metaphors. According to Lakoff and Johnson (1980: 14), orientation metaphors organise the whole conceptual system on the basis of interrelationships between concepts, giving each concept a spatial orientation. Orientation metaphors are mainly based on people’s physical and social experiences, and the same concept of orientation is applied in different ways depending on the kinds of experiences on which the metaphors are based. For instance, the vertical concept of “up” can be employed in different ways such as HAPPY IS UP, HAVING CONTROL OR FORCE IS UP,MORE IS UP, GOOD IS UP. The concept of verticality “up” can enter our experience in different ways, thus generating different metaphors. Lakoff and Johnson (1980: 16) propose that the metaphor of GOOD IS UP can be activated by phrases such as “Things are looking up; He does high-quality work; We hit a peak last year.” They argue that the primary empirical basis for the activation of this type of metaphor is that all events, behaviours, emotions, and other experiences that contribute to people’s well-being and are beneficial to them can be described as “up”. Since then, numerous scholars (Brunyé et al. 2012; Meier and Michael, 2004; Palma et al. 2011; Stepper and Strack, 1993) have conducted various experiments to demonstrate the association between positive emotions, behaviours, events, memories, and so on, are commonly associated with the spatial representation of “up”. These studies provide substantial experimental evidence for GOOD IS UP metaphor. Taken collectively, the linguistic modals “improve” and “highest” identified in Table 7 of this study exhibit a shared characteristic of vertical perception, specifically upward elevation. This characteristic renders them suitable as metaphorical keywords for the metaphor GOOD IS UP. Meanwhile, the linguistic modal “We improve our people’s lives” primarily highlights the engineers’ endeavour to construct a railway in the remote mountainous regions of China, with the aim of enhancing the quality of life for the local population. This initiative is regarded as a positive contribution towards the well-being of the people residing in these remote areas. The statement “What we’ve achieved here is the highest level in the country” emphasises the fact that Chinese scientists have achieved the highest level in China in building rockets, which is beneficial and positive for both the scientists involved and China. By examining the correlation between the linguistic modality and the pictorial modality in Table 7, it becomes evident that the construction of a railway for the people and the progress in the level of construction of rockets, which are positive and beneficial to the people and the country, can be characterised by the target domain “good”, which is associated with the source domain “up”, thus forming the metaphor GOOD IS UP.

Furthermore, the specifics of the image modality presented in Table 7, along with the shooting distance and camera movement, also play a significant role in the interpretation of GOOD IS UP. The combination of images in Pictures 1 and 2 of Table 7 shows people in different jobs working together to build a railway for people in a remote area, showing both the seemingly endless railway that has already been built and the section that is still under construction. The series of images depicted in Pictures 1 and 2 in Table 7 serve as a complementary visual representation to the specific content discussed in “the work” within the linguistic modal of “We are proud of the work we do”. It is also a strong illustration of the linguistic modal “We improve our people’s lives and bring our cities and remote areas closer together …”, i.e., the work of the railway we build or the railway we repair can improve the living standards of people in remote areas and bring cities and remote areas closer together. At the same time, the linguistic modal “proud” indicates that the work of the people building the railway in the combination of images in Pictures 1 and 2 of Table 7 is meaningful and positive. Compared to other forms of media, such as news comics and print advertisements, film possesses a distinct characteristic in its capacity to narrate a story, captivate or divert the audience’s attention, and effectively communicate a message through the dynamic movement of the camera (Wang and Cheong, 2009). Shots in motion pictures or films can be categorised into fixed and motion (dynamic) shots, where motion shots can be categorised into seven basic forms of shots: push in, pull out, pan, shift, follow, crane up and crane down (David et al. 2020; Steve, 2019). The images depicted in Pictures 1 and 2 within Table 7 showcase perspectives captured during a motion shot. This particular shot is a fusion of a crane up shot and a moving shot. In this combination of shots, the camera moves slowly in the horizontal direction while simultaneously ascending, thereby expanding the audience’s field of view from a long shot to an extreme long shot. This not only provides viewers with a glimpse into the engineers’ work, but also showcases the challenging environment in which they are constructing the railway. The presence of vast lakes and barren land, coupled with the dedicated individuals working in these conditions, serves to reinforce the notion that building a railway for remote communities is a commendable and worthwhile endeavour. The rising camera makes viewers have a vertical experience of going up, combining the language and visual cues discussed in the preceding section, facilitates the association between the positive aspects of constructing a railway to enhance people’s well-being and the upward direction. Consequently, this leads to the formation of metaphorical cognition, specifically the concept of “GOOD IS UP.”

The series of images depicted in Pictures 3 and 4 in Table 7 show different shots of individuals celebrating after successful completion of field experiments pertaining to Chinese rocket building technology. This signifies that the technology has currently reached the highest level in the country. The image compositions depicted in Picture 3 in Table 7 consist of fixed shots capturing individuals celebrating in various manners. One composition showcases scientists with joyful expressions on their faces, observing the successful outcome of the experiment. Another composition captures scientists taking a group selfie with their mobile phones to commemorate the experiment’s success. The images visually illustrate to the viewer that the linguistic modal display of “rocket building technology at the highest level in the country” is a good thing. These images serve as an illustration of the target domain “Good” within the “ GOOD IS UP”. The images depicted in Picture 4 in Table 7 capture a sequence of scenes in motion shots, in which the viewer’s field of view gradually expands in a crane up shot: From a long shot in which the viewer is able to observe the exuberant engineers who have yet to depart from the experimental site and the interior of the site gradually expands into an extreme long shot of the lone experimental site deep in the mountains. The utilisation of a crane up shot in this scene not only provides the viewer with a vertical experience of ascending, but also elicits a sense of the challenges faced by the scientists conducting their experimental work in a desolate location, as well as the arduous journey towards achieving their current success step by step. Therefore, by integrating the verbal modality and pictorial modality clues discussed in the preceding section, it becomes more convenient for the audience to establish a connection between the positive aspect of “reaching the highest level of technology in the country” and the upward direction. Consequently, this facilitates the formation of the metaphorical cognition that “GOOD IS UP”. Therefore, in line with the anchoring effect of linguistic modality on pictorial modality (Barthes, 1964: 44), the pictorial modality presented in Table 7 serves as a concrete representation of the linguistic modality. Specifically, the content pertaining to the target domain “good” is visually expanded upon, while the source domain “up” is depicted through dynamic motion shots. The combination of pictorial and linguistic modalities synergistically facilitates the audience in constructing and comprehending the multimodal metaphor “GOOD IS UP”. However, the crux of comprehending this metaphor resides in the evaluative discernment of the audience (Ibáñez-Arenós and Bort-Mir, 2020), which determines that the successful recognition of this metaphor requires more cognitive effort on the part of the audience.

Discussion

Main types of multimodal metaphorical representations

It is found that multimodal metaphors in the documentary are represented in a variety of ways, with the implicit source-verbal and pictorial target (63 cases, 45%) being the main representation of multimodal metaphors in the documentary. As evident in Table 2, the documentary showcases multimodal metaphorical representations that can be categorised into two main groups: explicit and implicit representations. Furthermore, these representations can be further classified into five subcategories, namely cross-modal mapping, mono-modal mapping, multimodal mapping, single-domain implicit mapping, and dual domain implicit mapping. The above five subcategories can be further divided into eight models according to the modal representation of the source domain and the target domain, such as verbal source-pictorial target; pictorial source-verbal target. This statement provides additional support for Forceville’s (2002) assertion that the target and source domains of metaphor in film can be represented in the form of pictures, verbal language, and sound. Furthermore, it suggests that a single domain can be represented simultaneously in multiple modes. The implicit source-verbal and pictorial target representation model is the most frequently occurring representation in the documentary. This representation puts the interpretation of the multimodal metaphor presented in the documentary in the hands of the viewer (Forceville, 2002). Rather than imposing the multimodal metaphor on the audience, it enables them to experience and perceive the metaphor (Forceville, 1999). Consequently, this approach facilitates the audience’s acceptance and comprehension of the metaphorical message conveyed in the documentary.Although scholars have shown interest in multimodal metaphors since their inception, the absence of a unified classification model can be attributed to the intricate cognitive mechanisms and representational modes involved in these metaphors. This study aims to investigate the cognitive characteristics of multimodal metaphorical representations, including the mapping patterns and representational modalities of the cognitive domain. The objective is to develop a unified and comprehensive classification model for multimodal metaphorical representations, with the ultimate goal of enhancing the understanding and analysis of multimodal metaphorical representations.

Compared to Forceville’s (1996; 2008) classification of non-verbal metaphorical representations, this study’s classification of multimodal metaphorical representations is more comprehensive and scientific. The exploration of non-verbal metaphorical representation patterns began with Forceville’s (1996: 108–148) classification of pictorial metaphors. However, the classification of pictorial metaphors primarily relies on the relationship between the source and target domains. It categorises pictorial metaphors into four distinct groups: metaphors with one pictorially present term (MP1), metaphors with two pictorially present terms (MP2), pictorial similes (PSs), and verbal-pictorial metaphors (VPMs). Although this classification can help to quickly clarify the source and target domains of pictorial metaphors and the relationship between them, it does not reflect the characteristics and advantages of non-verbal metaphors over verbal metaphors. The last classification model of verbal-pictorial metaphors (VPMS) is clearly inconsistent with the first three classifications according to the relationship between the source and target domains of the pictorial metaphor. Therefore, although this model of classifying non-verbal metaphors is an inspiration for the study of multimodal metaphorical representations, its lack of rigor and its inability to reflect the characteristics of non-verbal metaphors make it difficult to be widely used in multimodal metaphor studies. Since then, Forceville (2008: 464–469) has revised the classification model of pictorial metaphors, proposing four classifications: contextual metaphor, hybrid metaphor, pictorial simile, and integrated metaphor. This classification model emphasises the perception and experience of pictorial metaphors, but at the same time ignores the two cognitive domains of image metaphors. Since the nature of metaphor is to understand and explain one concrete, perceptible thing by means of another relatively abstract, complex thing (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980: 5), multimodal metaphor necessarily involves the representation and recognition of two cognitive domains as well. This also determines the one-sidedness of classifying representations of multimodal metaphors from a perceptual perspective only. The present study aims to classify the representations of multimodal metaphors by considering not only the perceptual perspective of multimodal metaphors, but also the modal characteristics of the representations of the source and target domains, as well as the relationship between these two cognitive domains. The perceptual dimension of multimodal metaphors is divided into explicit representation and implicit representation. Then, taking the representation modes and relations of the two cognitive domains of multimodal metaphor as the starting point, the explicit representation can be further divided into five subcategories: verbal source-pictorial target; pictorial source-verbal target; verbal mapping-picture example source; verbal mapping-picture example target; verbal -pictorial mapping. Implicit representation can be classified into three distinct categories: implicit source-verbal target-pictorial supplement; implicit source-verbal and pictorial target; verbal and pictorial supplement. This classification not only accentuates the perceptual attributes of multimodal metaphors, but also underscores the mode characteristics and interconnections between the two cognitive domains of multimodal metaphors simultaneously.

This study is also a revision and supplement to Feng’s (2011), Lan and Zuo’s (2016) and Yu’s (2013) multimodal approach to metaphorical representation. The delineation of how multimodal metaphors are represented from the perspective of multimodal metaphor mapping is a common feature of the above-mentioned scholars’ studies. Feng (2011) classified the representation of multimodal metaphors into cross-modal mapping, mono-modal mapping and multimodal mapping from the perspective of metaphorical mappings, but neglected the special category of implicit mapping. Lan and Zuo (2016) added implicit mapping to Feng’s (2011) three multimodal metaphorical representation models and divided the implicit mapping into two categories: implied source–pictorial or verbal target; pictorial or verbal source–implied target. However, this classification of implicit mapping only includes the case where the source or target domains are individually implicit and ignores the case where both domains are simultaneously implicit.

The present study contributes to the classification of multimodal metaphorical representations by incorporating implicit mapping into Feng’s (2011) three multimodal metaphorical representations. Additionally, it offers a revision to the implicit mapping proposed by Lan and Zuo (2016). This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the mapping characteristics of the source and target domains in implicit mapping. Additionally, it proposes a revised classification of implicit mapping, distinguishing between single-domain implicit mapping and dual domain implicit mapping. The single-domain implicit mapping can be further classified into two sub-categories: implicit source-verbal target-pictorial supplement; implicit source-verbal and pictorial target. The dual domain implicit mapping primarily encompasses verbal and pictorial supplementation. This classification demonstrates a higher level of conciseness, clarity, and comprehensiveness compared to the general classification of implicit mapping proposed by Lan and Zuo (2016).

Moreover, this study complements Yu’s (2013) multimodal metaphorical representation approach. Yu (2013) classified the metaphorical representations in news cartoons into six types, including pictorial source-verbal target; pictorial source-symbolic target; pictorial source-pictorial target, etc., from the perspectives of source and target domain representational modalities and the relationship between the two cognitive domains. The present study, on the other hand, expands the metaphorical representations in documentaries into eight types, such as verbal source-pictorial target; implicit source-verbal and pictorial target; verbal and pictorial supplement, on the basis of the source and target domain representational modalities and the relationship between the two cognitive domains. Yu (2013) classifies the mapping of multimodal metaphors into static-dynamic latitude and concrete-abstract latitude from the levels of mapping mode and mapping content. Specifically, the division of mapping mode is primarily determined by whether the metaphorical content as a whole represents a static or dynamic phenomenon. The categorization of mapping content is determined by whether the metaphor’s source and target domains represent tangible or intangible concepts. Both of these divisions are based on the semantic properties of metaphors or two cognitive domains as the main division criterion, which adds new perspectives to the study of metaphorical mapping to a certain extent, but fails to highlight the modal configuration characteristics of multimodal metaphorical mapping.

From the perspective of modal configuration characteristics of metaphor mapping, this study divides metaphor mapping in documentaries into five categories: cross-modal mapping, mono-modal mapping, multimodal mapping, single-domain implicit mapping and dual domain implicit mapping. This approach better highlights the multimodal nature of multimodal metaphor mapping. Furthermore, this study provides a more detailed classification of the five metaphorical mappings, categorising them into two major groups based on their explicit and implicit representations within the perceptual dimension. Among them, cross-modal mapping, mono-modal mapping, and multimodal mapping are categorised as explicit representations. Single-domain implicit mapping and dual domain implicit mapping belong to implicit representations. Therefore, in contrast to Yu’s (2013) study of multimodal metaphors at two levels: the representational modality of the cognitive domain and the semantic properties of the metaphorical mapping, this study explores the multimodal properties of multimodal metaphors at three levels: the perceptual level of multimodal metaphors, the characteristics of the modal configurations of the mappings, and the representational modality of the two cognitive domains.

Modal characteristics of multimodal metaphorical representations

Overall, documentaries mainly represent multimodal metaphors through four main types of modes: verbal mode, pictorial mode, verbal-pictorial mode, and implicit mode, but the frequency of use of each mode is extremely uneven. Among them, implicit mode and verbal-pictorial mode are the most common modes of representation in documentaries, while verbal and pictorial modes are used relatively less frequently. This is closely related to the documentary itself and the characteristics of each mode. The documentary is mainly a medium that transmits knowledge and information to viewers by invoking various modes such as pictures, verbal language, and the main purpose is to make viewers understand and accept the knowledge conveyed by the documentary. Therefore, documentaries do not employ a forceful approach to compel viewers to recognise metaphors. Instead, they frequently utilise implicit modes to subtly guide viewers in perceiving metaphors (Forceville, 1999). This approach allows viewers to better comprehend the information conveyed through these metaphors. Although the use of moving pictures in documentaries can effectively convey the source or target domains and create a strong visual impact, the interpretation of these images is subjective and varies among viewers (Kress, 2009: 56). This variability poses a challenge for the pictorial mode to become the dominant representational mode in documentaries. While the verbal mode of communication is effective in conveying information with clarity and accuracy, it often lacks the ability to engage viewers visually and stimulate their interest. Consequently, this limitation hinders the widespread dissemination of documentaries. The utilisation of the verbal-pictorial mode allows for the effective utilisation of the visual benefits of images, as well as the anchoring effect of verbal language on pictures (Barthes, 1964: 44). Consequently, this mode has emerged as a prominent method of representation in the realm of documentaries.

Specifically, the documentary exhibits distinct characteristics in the representational modes of both the source domain and the target domain. As can be seen from Table 8, among the four types of modes involved in the source domain representation mode, the implicit mode is used most frequently, 110 times in total, accounting for 79% of all source domain representation modes, and the verbal mode is the second most frequently used, 22 times in total. The verbal mode, on the other hand, is used only 6 times, and the pictorial mode is used the least frequently, with only 1 time. This finding indicates that multimodal metaphors employed in documentaries exhibit a reduced reliance on verbal mode, pictorial mode, and verbal-pictorial mode for representing the source domain. Instead, they opt for familiar elements with generic meanings to represent the source domain, implicitly conveying them within specific contexts or through verbal language. The frequent use of implicit mode in documentaries to represent the source domain is related to the low difficulty of recognising the source domain and the complexity of the target domain. The comprehension of source domains in documentaries is facilitated for viewers due to their specificity and universality. Consequently, these source domains are often implied within the context or verbal language, allowing more time and visual content for the interpretation and presentation of the target domain.

The modal characteristics of the target domain representations in the documentary are quite different from those of the source domain. The verbal-pictorial mode is used most frequently, 86 times, accounting for 62% of all target domain representational modes. The verbal mode is the second most frequently used, with a total of 47 times. Implicit mode and pictorial mode are used only 5 times and 1 time, respectively. This suggests that viewers’ recognition of the target domain requires both the pictorial mode to make an intuitive visual impact on their brain to impress them (Pérez-Sobrino, 2016) and the verbal mode to cooperate with the pictorial mode to avoid ambiguity. When the target domain is too abstract to be represented by pictorial mode, verbal mode is the preferred mode for documentaries in order to give the audience a clear and accurate perception of the target domain.

Furthermore, the different mapping relationships of multimodal metaphors in the documentary demonstrate once again the diversity of the use of multimodal metaphorical modes in multimodal discourse. Both traditional linguistic metaphors and multimodal metaphors are essentially ways of thinking (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980: 5), more specifically cross-domain mappings in the human cognitive system (Lakoff, 1993: 215). However, the mapping relationships of multimodal metaphors are more diverse than the single mapping relationship of traditional linguistic metaphors that use only linguistic mode for cross-domain mapping. For example, the multimodal metaphor in this documentary contains five mapping relationships: cross-modal mapping, mono-modal mapping, multimodal mapping, single-domain implicit mapping and dual domain implicit mapping. The majority of these mappings consist of single-domain implicit mappings, accounting for 76% of the total. Mono-modal mappings account for 18% of the total. The percentage of dual domain implicit mappings is 4%. Cross-modal mappings and multimodal mappings constitute the smallest proportion, amounting to only 1%.

The single-domain implicit mapping is the main mapping relationship for multimodal metaphors in this documentary and contains two main patterns: implicit source-verbal target-pictorial supplement; implicit source-verbal and pictorial target. In both patterns of multimodal metaphor, verbal mode participates in the representation of the target domain. This also confirms the conclusion of Zibin and Altakhaineh (2023) about the target domain of multimodal metaphor: the abstract nature of the target domain of multimodal metaphors makes it easier for the audience to perceive it through verbal mode rather than pictorial mode. Verbal mode in documentaries therefore plays a very important role in the audience’s interpretation and perception of the target domain of multimodal metaphors. In multimodal discourse, neither the constructors nor the de-constructors of multimodal metaphors should ignore verbal mode and overemphasise non-verbal mode such as picture and sound, but should make flexible use of multiple modes such as language and pictures to fully demonstrate the modal advantages of multimodal discourse. Furthermore, Zibin and Altakhaineh (2023) also point out that multimodal metaphors in cartoons use both pictorial and verbal modes to characterise the target domain of multimodal metaphors in order to provide the audience with more information about this cognitive domain, which in turn leads to feelings of incompatibility. However, this study finds that although multimodal metaphors in documentaries, like multimodal metaphors in cartoons, use pictures and language modes to represent the target domain in multiple ways in order to provide viewers with more information about this cognitive domain, their purpose is not to create a sense of incompatibility, but rather to provide viewers with a clearer and more accurate understanding of the target domain. The target domain “Tea trees” in the multimodal metaphor “Tea trees are humans” presented in Table 6 is depicted through both verbal and pictorial modes, providing the audience with a more comprehensive perception of the Chinese tea tree.

The significance of the verbal mode and the adaptability of the pictorial mode in delineating the two cognitive domains of the multimodal metaphor are well represented in the documentary, albeit somewhat inadequately depicted in the mono-modal mapping and the dual domain implicit mapping. As observed in mono-modal mapping, the source and target domains of multimodal metaphors for both patterns are characterised by the verbal mode exclusively or by the combination of verbal and pictorial modes. Verbal mode also plays a significant role in the interpretation of multimodal metaphors in the dual domain implicit mapping. The utilisation of pictorial modes in the documentary showcases their adaptability, as they are employed in the mono-modal mapping for the representation of the source domain and occasionally the target domain, depending on the multimodal metaphor. While the dual domain implicit mapping does not engage the two cognitive domains of the pictorial mode that characterise the multimodal metaphor, the interpretation of the multimodal metaphor fulfils a similar function as the verbal mode. Cross-modal and multimodal mappings can be classified as multimodal metaphors, as per the definition provided by Forceville and Urios-Aparisi (2009: 24). However, the documentary places the least emphasis on these mapping relationships, thereby reinforcing the inflexibility of the defined concept of multimodal metaphor (Lan and Zuo, 2016). Mechanically determining whether the source and target domains are represented by different modes as a criterion for multimodal metaphor is not only too narrow in understanding multimodal metaphor, but also not conducive to the long-term advancement of research in multimodal metaphor.