Abstract

Young people Not in Employment, Education, or Training (NEET) have become a target population of policymaking in Europe. After one decade of political attention and corresponding policy action, we consider it a good time to take stock of the literature that has dealt with young people who are classified as NEET and the policies adopted in response to the risk of leaving this group of vulnerable individuals behind. To this end, we carry out a systematic review of 83 articles published between 2011 and 2022 in pertinent journals indexed in the Web of Science (WoS). Our scoping review investigates how i) NEETs are defined in the literature, ii) which factors the authors have reported to be relevant for explaining whether a young person becomes NEET, and iii) how policymakers have responded to the existence of this group. We find that there exists no unanimous definition in the literature of young people classified as NEET, even though the European Union has enacted policies that target them. Our review also highlights that individual-level factors as much as contextual variables and policies determine the likelihood of individuals entering into the NEET status and that it matters whether young people live in urban or rural areas. Lastly, the literature has shown that European policymakers have adopted a wide range of policy responses in order to engage young people in employment, training, or education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For a long time, youth unemployment levels have been high in certain parts of the European Union (EU) and especially in Greece, Italy, and Spain (Avagianou et al. 2022). But the economic and financial crisis that hit the EU from 2008 onwards resulted in a situation in which youth unemployment rates rose in almost all member states, since crises tend to affect mostly those who are new entrants to the labor market (O’Reilly et al. 2015; Tosun et al. 2019; Scandurra et al. 2021). Consequently, EU policymakers began in 2009 to pay greater political attention to youth unemployment and took the first steps towards defining a common policy approach for addressing it in 2010 (Eichhorst and Rinne 2017; O’Reilly et al. 2015). One of the direct EU-level policy consequences of the elevated political attention levels was the adoption of the European Youth Guarantee in 2012 and its financial instrument, the European Youth Employment Initiative, in 2013. These jointly sought to support young people who fell into the category of Not in Education, Employment, or Training (NEET).

On the one hand, it was a remarkable development for the EU not to focus on unemployed young people only but to embrace the notion of NEET as the target of its policy action. Young people falling into this category have different characteristics and needs, which makes it more difficult to design and implement effective policy measures. The EU’s approach to formulating a common policy framework for addressing young people labelled as NEET is even more astounding considering that the EU does not have a legal competence in the fields of employment and welfare policies. Instead, these fields are governed by the so-called Open Method of Coordination (OMC), which does not require the EU member states to introduce or amend their policies but is based on policy monitoring and benchmarking (Heidenreich and Zeitlin 2013).

On the other hand, it is plausible that the EU shifted its focus onto young people who fall into the NEET category, as this group experiences manifold disadvantages (Ralston et al. 2022). Many individuals who qualify as NEETs are trapped in a vicious cycle between periods of unemployment, economic inactivity, and precarious or informal employment (Mussida and Sciulli 2023). On a societal level, high numbers of NEETs hurt the economy in the long term by leaving it exposed due to lack of human resources and by putting pressure on social protection systems (Ralston et al. 2022).

The point of departure of this scoping review is the EU’s decision in 2010 to embrace the concept of NEET and the academic literature which assesses the application of this term and reflects on the factors that increase the likelihood of young people being grouped under this label. The perspective chosen is motivated by the fact that the applicability of the NEET concept is not straightforward, in part because the concept as such has been criticized as ambiguous or as unable to capture the real-life challenges of young people, for it was supposedly “borne of administrative convenience, rather than sociological consistency” (Ralston et al. 2022, p. 59).

This study carries out a systematic review of 83 articles that focus on young people classified as NEET in European – not only EU – countries and which were published between 2011 and 2022 in pertinent journals indexed in the Web of Science (WoS). The literature refers to NEETs in different ways: Some studies simply state that individuals are NEETs; others focus on those who have an asserted status of a NEET; several trace the process of how young people become NEET; and a number of studies (critically) reflects on the notion and how it is used in research and policy practice. To structure this diverse corpus of research, we pursue three research questions:

-

1.

What insights does the literature provide into the conception of young people classified as NEET?

-

2.

Which factors does the literature highlight as causes of young people becoming NEET?

-

3.

Which national policies has the literature discussed as responses to young people falling into the NEET category?

The remainder of this article unfolds as follows. First, we outline the overarching conceptual framework on which the review is based. Then we present the methodology, identifying the corpus of research and how we have processed the included articles. After this, we summarize our findings for each of these three research questions. Finally, we discuss the insights yielded by the literature and offer some concluding remarks.

Conceptual framework

It lies in the nature of a scoping review to be based on existing research, which means the insights it offers depend on how the literature has engaged with a given topic. It follows that the topic of a scoping review should be selected in such a way that the literature offers valuable insights. The topic of how scholars and policymakers conceive of NEETs and which policy action has been taken in Europe to address their needs has produced an extensive literature. We structure the literature along three dimensions as derived from key concepts in multi-disciplinary research in policy sciences:

-

Dimension 1: Characteristics of the target group (Schneider and Ingram 1993)

-

Dimension 2: Causes underlying the policy issue (Howlett and Mukherjee 2014)

-

Dimension 3: Characteristics of the national policy responses to EU guidelines (Heidenreich and Zeitlin 2013)

Ideally, dimensions 1 and 2 would directly feed into the third dimension, but research typically concentrates on one or two of these dimensions. Consequently, this framework must be regarded as a heuristic tool rather than a causal model, aiming to map essential questions related to NEET policy.

Before motivating and elaborating on each of these dimensions, it is important to note that while the EU’s policy approach clearly has policy implications for the EU member states first and foremost, it also affects states in its ‘neighbourhood’ (Lavenex 2004). For example, Switzerland and the members of the European Economic Area (Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway) implement EU legislation related to the common market, and hence they are directly affected by the EU (Torfing et al. 2022). Other non-EU countries adopt EU legislation in order to prepare for accession to the EU, such as several countries in the Western Balkans (Bartlett and Uvalić 2022). Then, some countries consider EU policy as a source of inspiration and transfer these policies because they consider them to be effective or otherwise desirable (Lavenex 2004). Consequently, this scoping review includes both EU members states and a larger set of European countries.

The NEET concept originated in the United Kingdom (Furlong 2006; Mascherini 2019; Ralston et al. 2022). While it is not uncommon for the EU to embrace concepts that already exist in its member states (as the United Kingdom was until 2020), the adoption of this particular concept is surprising given that it allows for different interpretations and, related to this, different conceptions of the target population (Schneider and Ingram 1993). What is more, the concept and its use for labelling young people has been problematized. Furlong (2006), for instance, has cautioned against the use of the term and argued that policy outputs and outcomes vary strongly depending on the underlying conception of NEET. Given the definitional ambiguity of the concept and the fact that it is prone to criticism, the first review dimension concentrates on how NEETs are conceived in the pertinent literature.

Research on policy design has stressed the importance of the capacity of policymakers to analyze and understand the policy problems they seek to address (Howlett and Mukherjee 2014). The characteristics of issues and the perceptions of these characteristics have received attention by economists, who regard policies as sets of incentives. Depending on how an issue is conceived, the design of the policy responses chosen will vary both in terms of the individual instruments established by a policy as well as by their calibration (Eichhorst et al. 2017). It follows that it is instructive to offer insights in relation to the factors identified by relevant research as driving the risk of young Europeans to become NEET.

In line with Europeanization research – to which studies from various disciplines, including economics (van Vliet and Koster, 2011), law (Zahn, 2017), political science (Bussi and Graziano 2019), and sociology (Heidenreich and Bischoff 2008), have contributed – the national policy responses to the EU’s embracement of the NEET concept and the European Youth Guarantee are likely to vary. Pertinent research has shown that the EU has been influential in shaping or modifying national policies and even institutions, such as labor markets, which is the gist of the Europeanisation concept (see the overview article by O’Reilly et al. (2015)). However, how exactly national policymakers have implemented the EU’s requirements and guidelines depends on several factors, including specific challenges at the national (Assmann and Broschinski 2021) or even subnational (Cefalo et al. 2020; Scandurra et al. 2021) level, which include, inter alia, whether there are differences in how young people residing in urban or rural areas are integrated into labor markets (Farrugia 2016; Mujčinović et al. 2021). Given that the EU has only formulated guidelines for national policies targeting NEETs (Tosun et al. 2019; Trein and Tosun 2021), we consider it rewarding to discuss which national policy responses the literature has identified.

Data and methods

The method we used to analyze the literature is a scoping review. This type of review can help researchers to assess the “extent, range, and nature of research activity in a topic area; determine the value and potential scope and cost of undertaking a full systematic review; summarize and disseminate research findings; and identify research gaps in the existing literature” (Pham et al. 2014, p. 371). It needs to be distinguished from meta-analyses, which also draw on existing research but aim to statistically combine the results of the individual studies (Cemalcilar et al. 2018). Meta-analyses permit the testing of hypotheses, whereas scoping reviews do not. Therefore, the conceptual framework guiding this scoping review is of a heuristic, not causal nature.

As with any reviewing technique, the findings obtained using this method depend on the articles selected for inclusion. We opted exclusively for articles published in journals listed on the WoS platform, which is an article database covering various disciplines in the social sciences, humanities, and natural sciences. The main advantage of using WoS-indexed articles is that it keeps the corpus of literature focused on the topic of interest, for the WoS lists the journals in which relevant research is published. Also, the editors and reviewers of these journals have already assessed the quality of the included publications according to a standard which is itself subject to assessment by the WoS. To be clear, the corpus of NEET-focused research is larger, but we limited it to articles published in journals that are indexed in the WoS. Choosing a different criterion (e.g., Scopus-indexed articles) would have produced a different corpus of research.

Similarly in line with our conceptual framework, we implemented the search strings “(“NEET”) and ((“employment” AND “polic*”) or (“jobs” AND “polic*”) or (“labour” AND “polic*”) or (“work” AND “polic*”)) or (educ* AND polic*) or (school* AND polic*)” on 28 November 2022, which produced 120 records consisting of articles published between 2002 and 2022 (see A1–A3 in the Online Appendix). We inspected all records and excluded from our analysis the single one we could not find (see A4 in the Online Appendix). The records also comprised 37 articles that did not provide any insights for European countries or were not related to NEETs (see A4 in the Online Appendix). They entered the records because at least one of the authors was affiliated with a European university or research institute. We provide a Prisma diagram in the Online Appendix (see A3) to show the steps that led us to include a total of 83 papers in the analysis. We also present all papers (including those excluded from the analysis) briefly in the Online Appendix (see A4).

Having defined the review corpus, we applied a network analysis to the keywords of the 83 selected papers in order to map the topical space. The network analysis presented in the Online Appendix shows that the body of NEET literature is fragmented, as the individual articles focus on quite different aspects related to the concept (see A5–A9 in the Online Appendix).

Subsequently, we produced a reading grid, which includes information on the respective definition of NEET (age, target group) as well as the aims of the policies and policy instruments covered by the individual publications. We provide the complete grid in the Online Appendix (see A10) and present in this review only the results we obtained.

Characteristics of the target group

To address the first research question, we present the literature that engages with the characteristics of NEETs. We could identify three main dimensions in said literature: the age groups to which the NEET concept is applied, their employment status, and subgroups of young people who fall into this category.

Age group

Initially, the EU conceived of NEETs to comprise a group of young people aged 15 to 24 years, but then it broadened the term to include those aged 15–29 (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions 2022). The broadened age range corresponds to the discussion on NEETs by the International Labor Organization (ILO) and other international organizations.

Turning to the academic literature, we can see that it is characterized by varying definitions of the age range of young people who would fall into the NEET category (Sergi et al. 2018). Some papers use narrow age groups, such as youths aged 14–24 (Cabasés Piqué et al. 2016; Raghupathi and Raghupathi 2020), 15–24 (Abayasekara and Gunasekara 2019; Cefalo et al. 2020; Mauro and Mitra 2020; Mujčinović et al. 2021; Petrescu et al. 2022; Raileanu Szeles and Simionescu 2022), 15–25 (Smoter 2022), or 16–24 (Bradley et al. 2020; Maguire 2015; Mellberg et al. 2023; Tamesberger and Bacher 2014; Tanton et al. 2021). The variation in definitions of age group is almost to be expected. For example, Holmes et al. (2021), Rodriguez–Modroño (2019), and Zuccotti and O’Reilly (2019) concentrate on young people aged 15–29. Other studies largely stick with this definition but adjust the upper or lower age limits, usually because of data availability, and therefore use groupings such as 16–29 (Serracant 2014), 16–24 (Mawn et al. 2017; Palmer and Small 2021), or 15–27 (Wilson et al. 2008). Other variants include 18–24 (Lőrinc et al. 2020; Scandurra et al. 2021), 18–30 (Juberg and Skjefstad 2019), and 15–34 (Luca et al. 2020; Serracant 2014).

There is little discussion in the literature for choosing a given age range, except for mentioning the EU’s definition. Malo et al. (2023) argue that extending the upper limit from 24 to 29 has the advantage of including young people with a delayed school-to-work transition, which reflects the key argument advanced by Arnett (2007) about delays and detours in reaching adulthood.

The variation in how the age groups are defined is plausible. Especially in studies focusing on the transition to adulthood, ‘youth’ can have different meanings (García-Fuentes and Martínez García 2020). Furthermore, the construction of age groups depends on the historical and cultural context (Thompson 2011). For instance, the use of the lower limit of 16 could ground on the existing social norm from the 1970s that teenagers were generally looking to enter labor market in the United Kingdom by the age of 16 (Bynner 2012). In the broader literature, definitions of ‘normal’ life courses differ from one period to another, and in late modern societies in particular, the concept of the school-to-work transition becomes fragile and bendable, with spells of education or training often succeeding periods of employment (Arnett 2007). This view is also compatible with people that simply choose to take a year off, for instance, to travel, as reported by Maguire (2015). Belonging to the youth also depends on the decisions made by the young people themselves, and this is reflected in the varied definitions by national or international authorities and therefore in the literature.

An element missing in the literature as reviewed here is a critical reflection on the definition of the age range for young people who could qualify as NEET. What is also worth noting is that the age range covered in the studies is not based on theoretical considerations or at least not motivated by theoretical arguments.

Employment status

The statistical definition of the NEET status is based on a total of six months (or one-quarter of the past 24 months) out of work, education, or training (Yates et al. 2011). Furlong (2006) suggests a more nuanced definition of NEET which includes “young people who are long-term unemployed, fleetingly unemployed, looking after children or relatives in the home, temporarily sick or long-term disabled, putting their efforts into developing artistic or musical talents or simply taking a short break from work or education” (p. 554). In addition, the literature differentiates between those searching for a job, who are coined as ‘active’ NEETs, and those who are ‘inactive’ (Holmes et al. 2021).

Some authors problematise the varying definitions of NEET, as several include, for example, women with caring responsibilities, youths who cannot work due to illness or disability, those discouraged from looking for work, and those who are voluntarily in a NEET status (Yeung and Yang 2020). Therefore, as an alternative to the standard NEET classifications, Serracant (2014) develops a NEET-restricted indicator which refers to inactive, non-studying people who are not ill or disabled, have no caring responsibilities, and do not wish to work or study. André and Crosby (2022) distinguish between two groups of NEETs: those in “discontinuous”, unstable work situations and NEETs who are “outside the system”, that is, individuals who do not seek aid from service institutions. The authors contend that NEETs withdrawing from society and societal institutions is not an expression of lacking will but a way to confront mechanisms of exclusion.

Consequently, some youths fall under the radar and are labelled as ‘off-register NEETs’ when they do not participate in programs offered by public employment services and do not claim jobseeker’s allowance or other unemployment-related benefits (van Parys and Struyven 2013). By assigning people to the category of ‘inactive’ NEETs, they are cleared from unemployment statistics. This can mean, depending on the social protection regime in their country of residence, that they miss labor market interventions that target active NEETs only (Maguire 2015, p. 124).

Considering employment as a selection criterion for assigning young people to the NEET group entails strong assumptions, especially temporal ones. While the basic definition refers to a status at one given point in time, the concept as such entails the observation of the status of young people for a longer period of time (Dumouilla et al. 2021). For instance, Erdogan et al. (2021) exclude from the NEET category those individuals who received any type of education in the past four weeks. Goldman-Mellor et al. (2016) assess whether the NEET status may not be due to being on summer holiday or on parental leave. Manhica et al. (2019) define NEETs as individuals whose annual earnings are less than half the national base amount and who receive payments in the form of unemployment, sickness, disability, or social assistance benefits. However, most publications in our corpus simply assess the NEET status based on a person’s employment situation at the time of data collection.

Another criterion, albeit rarely used, associates the NEET status with the unwillingness of young people to receive education or training or to find employment (Mauro and Mitra 2020). Other studies also refer to people in precarious employment as NEETs (Lawy et al. 2010; Quinn 2013).

Given the variety of reasons why someone can end up being classified as a NEET, it is not surprising that the literature refers to different criteria for labelling someone as NEET. Of these, being in employment or not stands out as the dominant one, while the literature does recognize that the NEET concept goes beyond employment in the narrow sense.

Subgroups of NEETs

A semantic analysis by Dumouilla et al. (2021) of how often NEETs and non-NEETs use the term ‘NEET’ reveals that those who are not part of the group, but who are students in the same age group, tend to be more categorical in their definitions and to portray NEETs negatively. Despite both NEETs and non-NEETs being similar in how they stress the role of social context, the heterogeneity of the terms that the authors use to define NEETs exposes the lack of consensus on the definition. Erdogan et al. (2021), for instance, note with respect to the actions initiated under the umbrella of the Youth Guarantee scheme that “two-thirds of projects do not have a clear definition of their target groups” (p. 11).

Several papers criticize the heterogeneity of the NEET concept (Holmes et al. 2021; MacDonald 2011; Serracant 2014; Yeung and Yang 2020), since it can create measurement difficulties (Thompson 2011). The EU uses the term in the context of its Youth Strategy as a label describing a homogenous, static group (Cabasés Piqué et al. 2016) – a conception that fails to acknowledge that many NEETs also belong to risk groups such as the disabled, single mothers, and the unemployed (Cefalo et al. 2020). Hence, some authors discuss whether certain groups, such as young mothers with care responsibilities who are not looking for a job, should be excluded from the NEET category (Tamesberger and Bacher 2014). Others, meanwhile, argue that the NEET label is useful as it brings to the forefront teenage parents and carers as well as the disabled (Cefalo et al. 2020; Thompson 2011). The notion of specific categories of NEET is common to many papers in our selection (Smoter 2022). There are also some articles that treat NEET as a general label but control for the effects of specific statuses, such as re-entrants, the long-/short-term unemployed, the ill and disabled, caretakers, and the disadvantaged, among others. We explain this in greater detail in the section on individual covariates.

Summarizing the main insights

The literature on NEETs in Europe is keen to stress the origins of the concept in the United Kingdom and the EU’s role in promoting it. However, the literature engages with the role of the EU most directly when justifying the age range selected but much less so when presenting conceptualizations of NEET in terms of the criteria used to label them as such. The impression obtained from the literature aligns with the real-life situation that the EU has been most explicit in defining the age range for individuals who could enter the NEET category. Less explicitly defined than the age range were the different subgroups of NEETs, even though there exist compelling suggestions for identifying such groups. For example, Mascherini and Ledermaier (2016) propose a differentiation between re-entrants, the long-term unemployed, the short-term unemployed, people with an illness or disability, those with family responsibilities, those discouraged from finding work, and other NEETs. The application of this conceptualization could help scholars to arrive at a more nuanced characterization of NEETs.

Causes underlying the policy issue

This section discusses research that taps into the second guiding question of this paper by reviewing contextual and individual-level determinants for being classified as NEET.

Contextual factors

Research finds that the rate of NEETs depends on the national labor market (Holmes et al. 2021; Serracant 2014) and on events that have affected it, such as the economic and financial crisis (Signorelli and Choudhry 2015). Plausibly, pertinent research shows that high unemployment rates increase the number of NEETs (Maynou et al. 2022).

The literature has begun to differentiate between factors related to the urban and rural populations of young people. Along this line, Mujčinović et al. (2021), for instance, have shown that the relationship between unemployment and NEET rates holds equally true for rural areas. Several studies show that there exists a geographical component to the NEET risk. For example, in the United Kingdom, the NEET risk is higher outside of London (Holmes et al. 2021), while in Poland it is reported to be higher in urban areas (Smoter 2022). Austrian NEETs are also more likely to live in urban areas (Tamesberger and Bacher 2014).

Research has found that education has an attenuating effect, as higher educational attainments tend to buffer the impact of economic crises (Kelly and McGuinness 2015; Scandurra et al., 2021). Likewise, public policies have an impact on NEET rates. For example, Turkey raised the age-specific minimum wage, which, in the short term, increased the NEET risk, but in the medium term, this effect has disappeared (Dayioglu et al. 2022).

Scholars have also paid notable attention to the welfare regime types postulated by Esping‐Andersen (1989), which Cinalli and Giugni (2013) have since adapted to youth unemployment. This literature has shown that sub-protective and familial (liberal and Mediterranean) welfare regimes maintain cross-regional inequalities; these stand in contrast to universalistic and employment-centered (Nordic and Conservative) regimes that boost the convergence of NEET rates across regions within a given society (Rambla and Scandurra 2021).

Furthermore, regional disparities (Scandurra et al. 2021) or longer school-to-work transition pathways (Haikkola 2021) may trigger higher NEET rates. These mechanisms relate to the role of schools, social services, municipalities, and families in defining the opportunity structures for young people (Rambla and Scandurra 2021, p. 6). Several studies stress the importance of public employment services in preventing young people from entering the NEET status or for overcoming this status (Haikkola 2021; Smoter 2022; van Parys and Struyven 2013). However, empirical research has shown that contact with public employment services does not have a significant effect on a temporary or permanent exit of the NEET situation (Bynner 2012; Tamesberger and Bacher 2014).

Societal factors are also important for explaining variation across countries or across regions within countries. For example, higher NEET rates are associated with higher adolescent fertility rates at the regional level in Spain (Scandurra et al. 2021). The higher the percentage of married women in a region, the lower the youth unemployment and NEET rates are; and the higher the percentage of part-time workers in a region, the higher the NEET rate is (Bradley et al. 2020). Higher educational attainment of the youth labor force lowers NEET rates (Bradley et al. 2020).

Digital skills are becoming increasingly important for job-seekers (Stosic et al. 2020). These vary across Europe as much as access to the internet. Overcoming the digital divide through measures such as increasing internet usage and improving digital skills can reduce NEET rates (Raileanu Szeles and Simionescu 2022).

Individual-level factors

Since the status of NEET is attributed to a person, scholars have tested several individual-level factors to explain it. Among them, education is a key factor for explaining whether young people become NEET. In Italy, most NEETs have no degree (Sergi et al. 2018), whereas data for the United Kingdom reveal that in the last decade, this effect has disappeared and even reversed (Holmes et al., 2021). In general, though, there is a robust empirical pattern indicating that low-educational attainment and leaving school early (Burlina et al. 2021; Madia et al. 2022; Smoter 2022; Tamesberger and Bacher 2014), as well as truancy (Bradley and Crouchley 2020; Hale and Viner 2018), increase the NEET risk, while higher educational attainment in the adult population and among parents can counter high NEET rates (Odoardi 2020; Rasalingam et al. 2021).

That leaving school early is a decisive factor for being labelled as NEET is also confirmed for European regions (Maynou et al. 2022). In Italy, leaving school early is related to the NEET status for men especially (Luca et al. 2020). Early drop-out is shown to be connected to remaining in the NEET situation long-term in Germany (Klug et al. 2019) and Spain (Salvà-Mut et al. 2016). In Spain, education on the ISCED 3–4 level decreases the probability of a man being classified as NEET, while for women, holding a university degree (ISCED 5–8) increases the risk (Rodriguez-Modroño 2019). In the United Kingdom, low education levels and having a part-time low-paid job often prove to be a steppingstone towards entering a NEET situation (Lawy et al. 2010).

Furthermore, the alignment of professional aspirations and intentions with educational expectations has an impact on the likelihood of entering the NEET status. The effects are not consistent though, with some papers finding that educational misalignment or uncertain occupational aspirations raises the NEET risk (Yates et al. 2011) and others reporting the opposite effect (Simões et al. 2017; Thompson 2011).

The NEET group is divided based on their level of key competences: Some have high literacy skills, others low ones (van Vugt et al. 2022). Low-literate young people are more likely to become long-term NEET, while soft-skills are also less present among NEETs (Goldman-Mellor et al. 2016). High truancy and low test scores increase the NEET probability (Bradley & Crouchley 2020). Digital skills, by themselves, are not enough for a NEET to affect the transition towards occupational pathways (Szpakowicz 2022).

Gender is another critical factor for determining a person’s NEET risk. A higher incidence of labelled NEETs in the corresponding population can be observed in the 1990s in the United Kingdom (Bynner 2012), for Polish women (Smoter 2022), and in Ireland before the 2000s economic crisis, though the effect reverted after this crisis (Kelly and McGuinness 2015). The same holds true for women in Austria in times of economic crisis (Tamesberger and Bacher 2014). The NEET probability in combination with mismatched educational alignments and uncertain occupational aspirations is greater among young females than males (Salvà-Mut et al. 2016; Yates et al. 2011), but males are more likely to be expelled from school and later become NEET (Madia et al. 2022).

The interaction of ethnicity, gender and parents’ work status is also decisive: Second-generation Indian and African men as well as Bangladeshi men and women with unemployed parents face a lower NEET risk than white British living in a household with parents who do not work (Zuccotti and O’Reilly 2019).

The risk of unemployment and NEET does differ between males and females but is almost always greater for males (Bradley et al. 2020). For young men, inner city housing has a large effect, while for young women, family poverty has a stronger impact (Bynner and Parsons 2002). However, as with the other factors discussed so far, the empirical findings vary. Simões et al. (2017), for instance, report no difference between genders.

Older age is associated with a higher likelihood to become NEET (Smoter 2022), but its effect decreased recently as compared to the 1980s (Holmes et al. 2021). For Spanish young men, after controlling for various other factors, the NEET probability increases with age, but age has no effect for women (Rodriguez-Modroño 2019). The risk perception regarding the NEET status differs between young people and adults: While young people stressed the influence of institutional and social factors, adults focused rather on structural factors and personal challenges (Brown et al. 2022).

Family is also central to the NEET status. Unstable family conditions during childhood (Thompson 2011), including lack of parental interest (Bynner 2012) and an abusive childhood (Pinto Pereira et al. 2017), increase the NEET probability. Out-of-home care (OHC) experience increases the NEET risk in Nordic countries, and the risk increases even more for people with both OHC experience and poor school performance (Berlin et al. 2021). Living with parents decreases the probability of entering into the NEET status (Holmes et al. 2021), but youths living with workless parents are on average at greater NEET risk than those from households with at least one working parent (Zuccotti and O’Reilly 2019). From a different perspective, living on one’s own decreases one’s perceived self-efficacy, as contrasted to living with parents, yet increases educational aspirations (Simões et al. 2017). The parents’ socio-economic situation, based on proxies such as low household income and skilled manual class, increases the odds of entering the NEET status (Bynner 2012; Campbell et al. 2020).

Moving in with a partner at an early age is strongly related to entering into the NEET status, which may be due to the overall vulnerability of a person’s family of origin (Alcázar et al., 2020). Living as a couple increases the NEET risks for both men and women (Rodriguez-Modroño 2019).

Having children is an additional NEET risk factor (García-Fuentes and Martínez García 2020; Tamesberger and Bacher 2014). Teenage pregnancy has a significant effect on NEET risk for young women but no significant influence for their male counterparts (Yates et al. 2011); however, child penalty (the effect of having children on income for women compared to men) has decreased in recent years (Holmes et al. 2021). Unpaid reproductive work is excluded from a new re-defined NEET indicator since it does not match with the idea of passive inactivity, and the majority of people from this group are not at risk of social exclusion (Serracant 2014). In fact, in one study, NEETs, especially women, reported having other family or personal responsibilities as their reason for not seeking work (García-Fuentes and Martínez García 2020).

For certain health conditions, such as sensory impairment, epilepsy and spinal muscular atrophy, spina bifida, and cerebral palsy, the NEET odds are particularly high (Rasalingam et al., 2021). Chronic illness is not relevant, but a general low health status in early adolescence is a catalyst for becoming NEET (Hale & Viner, 2018). Moreover, mental health problems are reported to be associated with the NEET status (Goldman-Mellor et al., 2016; Holmes et al., 2021; Karaoglan et al., 2022; Leavey et al., 2019). Receiving mental health care treatment increases the odds of falling into the NEET category for individuals younger than 21 years of age (Rasalingam et al., 2021).

The same holds true for obesity and alcohol consumption (Karaoglan et al., 2022), in particular for older and long-term NEETs (Basta et al. 2019). In a study of British NEETs, young men who were NEET were more likely to self-report smoking or drug use. The debate on the relationship between alcohol and drug problems and being labelled as NEET sparks controversies. One study criticizes that this connection was addressed in discourses of Norwegian policy documents without scientific evidence, thus contributing to the creation of myths and stigma (Juberg & Skjefstad 2019). However, Manhica et al. (2019) bring compelling evidence that the NEET status contributes to an increasing risk of alcohol use disorder in Sweden. Having parents with substance abuse problems can also have an impact on how youths experience the school-to-work transition, as they remain relatively invisible to social services or may not even be eligible because they exceed the age limit (Wilson, Cunningham-Burley, Bancroft, and Backett-Milburn 2008).

Having a disability can make the school-to work transition difficult for young people. Nevertheless, authors such as García-Fuentes and Martínez García (2020), Holmes et al. (2021), and Serracant (2014) exclude disabled or ill people from the NEET category because they are an inactive population due to reasons alien to their will. These researchers do, however, acknowledge that many of these people are in difficult situations and need specific help programs. A study of Scottish youths with learning disabilities confirms that the majority was highly motivated to find a job despite several setbacks and barriers (MacIntyre, 2014).

Youths with a migration background also face a higher NEET risk (Tamesberger and Bacher 2014). As mentioned above, they are often at risk of intersectional, multiple disadvantages, such as being a woman with a first- or second-generation migration history.

A low socio-economic status (Alcázar et al. 2020) increases the NEET likelihood for men with misaligned aspirations and has an even worse impact for those with uncertain expectations (Thompson 2011; Yates et al. 2011). Having parents with a lower socio-economic status was more strongly associated with the NEET risk than were adverse childhood experiences (Pitkänen et al. 2021). Young people who are NEETs are likely to have had a low birth weight and to have grown up in inner city public housing in poor families where they lacked educational achievement and cultural capital (Bynner and Parsons 2002). Hence, cultural capital reduces the risk of entering the NEET status (Burlina et al. 2021).

Work experience decreases the NEET likelihood across genders and years for Spanish youths. Being unemployed for six months or less increases the NEET odds. Longer unemployment periods for more than six months were especially hard on women in 2013 and on both genders in 2016 (Rodriguez-Modroño 2019).

Entering the NEET status is shown to relate to a vicious circle that perpetuates this status over time and transmits it to subsequent generations (Bynner 2012; Thompson 2011). A similar vicious circle is observed between lack of education, unemployment, and low qualifications. They mutually enforce each other and keep a young person in the NEET status trapped in this situation.

Nevertheless, some of the above-mentioned covariates of being labelled as NEET have an impact beyond the direct associations. For instance, a low socio-economic status in the family of origin not only increases by itself the probability of being labelled as NEET; it also raises the likelihood of early drop-out and truancy, and both increase the probability to become NEET. Therefore, it is likely that a reversed Matthew effect is at play: Negative factors accumulate and couple to trigger the NEET status.

Summarizing the main insights

The literature reveals that the factors which result in young people entering the NEET status are multiple and interwoven, but how they interweave depends on several country-level factors ranging from existing policies to labor market and welfare regimes and even to how the economy is structured. Within-country variations, such as regional differences and the rural-urban divide, also exist and highlight a gap in equal opportunities for young people based on their place of residency. The literature equally shows that measures for supporting young people in leaving the NEET status or for not entering into it must also address individual opportunities for education, training, and employment. If policy-makers in Europe want to reduce the number of young people who fall into the NEET category, they cannot focus on employment only but must adopt a more holistic understanding of the various individual steps in the school-to-work transition as well as contextual factors surrounding them. What is more, the policy responses need to be tailormade, as formally recognized by the EU, since research has highlighted the importance of young people’s personal situation for becoming NEET. An aspect that deserves more attention in the literature is how the various factors interact with each other, and there is a lack of longitudinal analysis that concentrates on the labor market outcomes of young people and how they are related to each other.

Characteristics of the National policy responses to EU guidelines

In this section, we provide insights from the literature on policy responses to the EU’s framework on NEETs. For this, we sub-divided the literature into studies inspecting the public policy responses targeting NEETs more generally and studies that more specifically analyze policy principles and goals as well as instruments and their target areas.

The need for NEET-focused policies

One literature strand focuses on the extent to which policies do and should capture the specificities of NEET; we refer to this as the reflexive stream of policy-related research. Policies addressing NEETs face the challenge that this group is heterogenous, making it difficult to formulate adequate policy recommendations (Malo et al. 2023). However, Finlay et al. (2010) reflect on adequate public policies for effectively addressing NEETs and call for policy interventions that are tailored to different subgroups of NEETs.

A critical stream of research questions the need for dedicated policies addressing NEETs. For example, Thompson (2011) contends that NEETs are not more or less socially excluded than other individuals and calls for policy interventions that focus on young people in an effort to prevent them from entering the NEET status. Maguire (2010) goes a step further and contends that the construction of NEETs as a target population aggravates this problem instead of helping to address it.

Types of NEET-focused policies

We could observe several attempts in the literature to classify NEET-focused policies. For example, Erdogan et al. (2021) analyze and classify sets of EU policies, while Rambla and Scandurra (2021) propose a conceptualization of NEET-focused policies on the basis of welfare regimes. According Rambla and Scandurra, universalistic (i.e. Nordic) welfare regimes focus on individual choice and design policy interventions by providing public services and employment in the public sector. In their typically stratified form of welfare provision, employment-centered (Conservative) welfare regimes link access to the labor market to the skills of individuals. Liberal welfare regimes focus on comprehensive education systems and address mainly the high-skilled and dropouts from upper-secondary school. Finally, familial (Mediterranean) welfare regimes also focus on comprehensive education systems yet have an underdeveloped vocational sector. Additionally, access to the labor market in such regimes is limited and highly stratified.

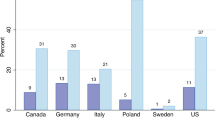

Comparative policy assessments focus on the EU Youth Guarantee and its implementation (Cabasés Piqué et al. 2016; Pesquera Alonso et al. 2021) and evaluate the influence of education and social policies on cross-national variations in NEETs (van Vugt et al. 2022).

Research on specific factors is the fourth stream. Smoter (2022) and Maguire (2015), for instance, assess the number and structure of NEETs as well as the policies developed by public employment services in order to provide these individuals with education, training, or employment. Other policy interventions concentrate on soft factors that may lead to policy action, such as commitment to work (Goldman-Mellor et al. 2016). Additional research highlights neoliberal discourses which govern public opinion and policy documents addressing NEETs (Juberg and Skjefstad 2019).

Policy principles and goals

Few articles included in the review provide a theoretical underpinning for the type of policy interventions selected by policymakers or advocated by the researchers themselves. Among the studies that do are those which discuss whether NEET policies should be designed at the national or the subnational level, mostly the NUTS2 regions (Maynou et al. 2022; Rambla and Scandurra 2021), or at the municipal level (Saczyńska-Sokół 2018).

A few pertinent studies elaborate on two policy principles that stand out: first, the idea of bringing action closer to the specific needs of the (potential) NEET by advocating tailormade policies (Bynner 2012; Finlay et al. 2010); second, the notion of the embeddedness of young people in their respective social context has induced researchers to focus on social networks and the education system and how they operate together (Görlich and Katznelson 2015). Thus, a literature exists that builds on the principle of tailormade policies, while another stresses the importance of holistic policy approaches.

The bulk of research advocates tailormade policies for different types of NEETs in recognition of the heterogeneity of this group (Furlong 2006; Holmes et al. 2021; MacDonald 2011; Pemberton 2008; Serracant 2014; Yeung and Yang 2020). However, a complementary perspective exists, too. Dorsett and Lucchino (2014), for example, argue in favor of a common policy for all NEETs, even though they acknowledge the heterogeneity of this group. Turning to the principle of a holistic approach, scholars predominantly define this as the need to coordinate different sectoral policies or to adopt multisectoral policy packages (Trein and Tosun 2021). The literature has identified education, employment, and health policy as the critical sectors and argued that policy action in them should be coordinated (Dorsett and Lucchino 2014; Furlong 2006; Tanton et al. 2021).

In addtition to policy principles, the policy-focused literature also elaborates on policy goals. One of the policy goals discussed in the literature refers to the degree to which different types of NEETs have access to services and support. Thompson (2011), for instance, considers inequalities in accessing education and the labor market as the main reason for some young people to become NEET. From this comes the demand for policies that aim to reduce or overcome these inequalities. A complementary perspective explicitly calls for unequal treatment and affirmative action, for example, by establishing special childcare offers for single mothers so they can terminate their NEET status; another suggestion is to support “blind hiring”, a practice in which personal information concerning the applicant is concealed to avoid bias and ensure a more equal access to the labor market (Klug et al. 2019).

We could identify a cluster of policy-focused research that brings together three key issues: employability, education, and equality of access, which is a finding of the network analysis (see A5 in the online appendix). The study by Yeung and Yang (2020) captures this integrated perspective very well. The authors contend that policy interventions must consider both the demand and the supply side, highlighting that education and skills need to match (future) labor market needs. To this end, they explain that such policies should (1) provide more training, internships, and mentoring, especially for women, but with a focus on capabilities instead of certifications (Bynner 2012); (2) provide protection for vulnerable groups; and (3) design differentiated interventions for different groups.

Policy instrument types

There exist several types of policy instruments, which are based on information provision, regulating the behavior of the target populations, providing financial incentives, and the direct provision of services by the state (Margetts and Hood 2016).

Information-based policy instruments as discussed in the literature predominantly concern informing NEETs about public programs and measures and about informing the stakeholders about the tools in place for assisting the NEETs (Smoter 2022). One example of such an instrument is career counselling, which the literature identifies as critical since NEETs tend to lack knowledge on school-to-work pathways (Dorsett and Lucchino 2014; Simões et al. 2017; Szpakowicz 2022). As Pitkänen et al. (2021) show, schools and families must work together if counselling is to be effective.

Regulations play an important role in the national approaches to implementing the European Youth Guarantee program (Cabasés Piqué et al. 2016; Erdogan et al. 2021; Focacci 2020). For example, Juberg and Skjefstad (2019) focus on the corpus of Norwegian legislation addressing NEETs and classify the types of policies adopted, including regulations. Other studies concentrate on specific regulatory aspects, such as the impact of increasing the years of mandatory schooling and how this affects young people’s NEET risk (Pitkänen et al. 2021). For example, in the United Kingdom, a statutory law requires young people to participate in education or training until their 18th birthday through full-time study either in a school, at a college, or with a training provider. In 2020, the UK government enacted specific policies to try and increase the status of technical education, establishing new vocational education and training pathways (Brown et al. 2022).

Most policy-focused studies concentrate on policy instruments targeting both the young people themselves (through education and training measures) and the labor market (Cabasés Piqué et al. 2016; Smoter 2022), mostly in the form of active labor market policies (ALMPs). ALMPs feature prominently in the European Youth Guarantee, and therefore it comes as little surprise that this policy type has been examined by numerous scholars. ALMPs for youths combine all four types of policy instruments, as Tosun et al. (2017) show, including financial incentives (for employers) and the direct provision of employment through the state. Table 1 summarizes examples taken from the 83 papers that illustrate different types of ALMPs. In particular, ALMP measures related to learning and apprenticeship have increased over time.

Target areas of policies

The rural-urban divide, important in the approach proposed by Erdogan et al. (2021), is visible in particular when the authors consider the social inclusiveness aspects of the policy actions related to the Youth Guarantee. Two articles in our selection focus on the specific situation of rural NEETs in the remote Portuguese region of Azores, stressing their cumulative disadvantage (Simões et al. 2017; Simões et al. 2021). Nevertheless, measures directly targeting rural NEETs are often missing in national policy implementation plans, as the development of the Youth Guarantee in Romania, Italy, and Portugal showcases (Petrescu et al. 2022). In contrast, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, and Serbia, youths are indirectly targeted within agricultural and rural development policies through measures that support agricultural producers (Mujčinović et al. 2021). Ireland, conversely, proactively supports rural youth NEETs through comprehensive policies and initiatives, such as rural youth participation in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics programs, or through regional science festivals in rural Ireland (Mujčinović et al. 2021). A complementary perspective is put forth by Quinn (2013), who, on the basis of data for young people in jobs without training in rural Southwest England, argues that policies should expose these disadvantaged individuals to nature experience.

In the study by Erdogan et al. (2021), some of the projects reviewed are at the cross-border regional level. Local governments or non-state actors are mentioned as partners in a few projects, while the bulk of policy interventions take place at the national level.

Several studies in our selection stress the transferability of findings. For instance, Focacci (2020) claims that her findings for Trento (Italy) are transferable to regions in Italy or other EU countries, like Denmark and Austria, which share with Trento the policy approach to inactivity. Focacci’s claim, however, should be caveated, since structural inequalities across regions can shape NEET opportunities; in particular, mobility often serves as a means of escaping unfavorable socio-economic conditions (Silva et al. 2021).

Our review has revealed that policy proposals also take regional distinctions into account. To bridge the negative effect of the regional digital divide in the EU on NEETs, Raileanu Szeles and Simionescu (2022) call for an increase in higher education spending in order to advance digital literacy skills and stimulate economic growth in the information and communication sector. The latter only applies to already digitally developed regions; for the other regions, strengthening and expanding the traditional sector of manufacturing is the only way to allow regions to reintegrate NEETs.

Summarizing the main insights

The literature offers a comprehensive discussion of the policy responses to young people classified as NEET. This comes as little surprise given that the EU has stipulated guidelines for addressing this group of young people. What we did find striking was that the literature has not only engaged with NEET-focused policies from different conceptual and theoretical perspectives; it has also not reflected critically on such policies. Several studies have either called for tailormade policy responses in order to capture the varied needs of the different subgroups of young people categorized as NEET. However, the clearest trend in the literature constitutes the focus on ALMPs, which scholars view as the set of policy instruments most effective in bringing young people into education, employment, or training. Especially the most recent articles published on NEETs call for the need to adapt ALMPs to the characteristics of the place where young people reside, that is, urban or rural areas. The discussion of whether rural target groups need different policy instruments or policy instruments that are calibrated differently appears to us as a seminal avenue for future research.

Conclusion

The economic and financial crisis from 2008 onwards brought challenges to various groups in Europe, as not only those who had already experienced economic hardship and disadvantages were hard hit, but also those without this experience. Among those affected most by the economic and financial crisis were young people. EU policymakers realized that these could get left behind not only because they were not being offered (adequate) jobs but also because they were inactive in the sense of not participating in education or training programs. To capture this group of disadvantaged young people, EU policymakers embraced the notion of NEETs and required policymakers in the EU member states to take policy action targeting this group.

This article mapped the research that dealt with the various conceptions of NEETs and the policy responses which have been adopted to improve their situation in the EU and European countries more generally. As the review revealed, the literature has paid considerable attention in conceiving of who is labelled as a NEET and who is not. Researchers have predominantly focused on empirical and descriptive criteria, while leaving ontological questions unconsidered.

To explain under which circumstances young people are likely to end up being labelled as NEET, research differentiates between context-level variables (which refer to the national or regional level) and individual-level factors. It also tests hypotheses that stress both their isolate and interactive effects. This body of research is relatively coherent and offers some intriguing cumulative insights, such as the varied impact of individual-level factors when changing the socio-economic context. The observed variation also invites a critical rethinking of the construction of the NEET category.

By all accounts, the variation in the importance of factors across countries or groups of young people justifies tailormade policies rather than the adoption of policies that are too similar and therefore fail to account adequately for why a young person ends up being labelled as NEET.

Turning to the third review dimension, we observed two striking features. The first is the literature’s focus on the implementation of the European Youth Guarantee, which is plausible considering it was the first time that the EU had adopted a dedicated measure addressing the integration of young people into the labor market. The research consulted has shown that the implementation of the Youth Guarantee has been uneven, and several empirical studies call into question the effectiveness of the Youth Guarantee. The second feature of the literature is its emphasis on ALMPs. The dominant stance is that the situation of NEETs can only be improved if the government not only intervenes in the labor market but also asks young people to become active themselves. Within this literature, the focus has been on a wide range of more specific measures which allow for assessing to what degree they are tailored to NEETs, or even to different subgroups of NEETs, and how holistic they are in the sense of overcoming sectoral boundaries.

The insights provided in this review depend on what has already been studied in the literature. While we are positive that the literature already offers a wealth of insights, there are several ways in which future research could go beyond the state of research as depicted here. First, we would have wished to offer a more wholesome discussion on how geography or place of residence matters. The geographical or spatial dimension was captured by the literature on the causes of young people becoming NEET, but it was mostly absent in the policy-focused literature, with the study by Erdogan et al. (2021) being an important exception. Consequently, we invite future research to pay more attention to the question of how place of residence matters and how it can be addressed by policymaking.

Second, throughout the review we mentioned time-related differences in reported associations between being NEET and its origins, consequences, or policy that address NEETs. However, we did not systematically approach our corpus from a temporal perspective. Future research may overcome this limitation by stressing the dynamics of all these elements and proposing periodization, including the periodization of high-profile policy responses and of academic interests in the field.

Third, as stated in the section outlining our conceptual framework, we had to look into the three research dimensions separately. To date, there exist no attempts to understand how policymakers understand the issue of there being young people who are NEET, by what sources their understanding is informed, and how closely they follow up on their understanding by proposing policy responses. In other words, based on this scoping review, we see room for expanding the state of research by applying the analytical perspective of policy design (Howlett and Mukherjee 2014) to the study of how policymakers have reacted to NEETs.

Data availability

Data sharing is not required as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Abayasekara A, Gunasekara N (2019) Determinants of youth not in education, employment or training: evidence from Sri Lanka. Rev Dev Econ 23(4):1840–1862. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12615

Alcázar L, Balarin M, Glave C, Rodríguez MF (2020) Fractured lives: understanding urban youth vulnerability in Perú. J Youth Stud 23(2):140–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1587154

André G, Crosby A (2022) The “NEET” category from the perspective of inequalities: toward a typology of school-to-work transitions among youth from lower class neighborhoods in the Brussels region (Belgium). J Youth Stud 2(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2022.2098707

Arnett JJ (2007) Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Dev Perspect 1(2):68–73

Assmann M-L, Broschinski S (2021) Mapping young NEETs across Europe: exploring the institutional configurations promoting youth disengagement from education and employment. J Appl Youth Stud 4(2):95–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43151-021-00040-w

Avagianou A, Kapitsinis N, Papageorgiou I, Strand AH, Gialis S (2022) Being NEET in youthspaces of the EU South: a post-recession regional perspective. YOUNG 30(5):425–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/11033088221086365

Bartlett W, Uvalić M (2022) Introduction: key challenges for economic inclusion in the Western Balkans. In W. Bartlett & M. Uvalić (Eds.), New Perspectives on South-East Europe. Towards Economic Inclusion in the Western Balkans (Vol. 13, pp. 1–16). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06112-7_1

Basta M, Karakonstantis S, Koutra K, Dafermos V, Papargiris A, Drakaki M, Tzagkarakis S, Vgontzas A, Simos P, Papadakis N (2019) NEET status among young Greeks: association with mental health and substance use. J Affect Disord 253(12):210–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.095

Berlin M, Kääriälä A, Lausten M, Andersson G, Brännström L (2021) Long‐term NEET among young adults with experience of out‐of‐home care: a comparative study of three Nordic countries. Int J Soc Welf 30(3):266–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12463

Bradley S, Crouchley R (2020) The effects of test scores and truancy on youth unemployment and inactivity: a simultaneous equations approach. Empir Econ 59(4):1799–1831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01691-8

Bradley S, Migali G, Navarro Paniagua M (2020) Spatial variations and clustering in the rates of youth unemployment and NEET: a comparative analysis of Italy, Spain, and the UK. J Reg Sci 60(5):1074–1107. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12501

Brown C, Douthwaite A, Costas Batlle I, Savvides N (2022) A multi-stakeholder analysis of the risks to early school leaving: comparing young peoples’ and educators’ perspectives on five categories of risk. J Youth Stud 18(2):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2022.2132139

Burlina C, Crociata A, Odoardi I (2021) Can culture save young Italians? The role of cultural capital on Italian NEETs behaviour. Econ Polit 38(3):943–969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-021-00219-7

Bussi M, Graziano P (2019) Europeanisation and the youth guarantee: the case of France. Int J Soc Welf 28(4):394–403

Bynner J (2012) Policy reflections guided by longitudinal study, youth training, social exclusion, and more recently neet. Br J Educ Stud 60(1):39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2011.650943

Bynner J, Parsons S (2002) Social exclusion and the transition from school to work: the case of young people not in education, employment, or training (NEET). J Vocat Behav 60(2):289–309. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1868

Cabasés Piqué MÀ, Pardell Veà A, Strecker T (2016) The EU youth guarantee – a critical analysis of its implementation in Spain. J Youth Stud 19(5):684–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1098777

Campbell R, Wright C, Hickman M, Kipping RR, Smith M, Pouliou T, Heron J (2020) Multiple risk behaviour in adolescence is associated with substantial adverse health and social outcomes in early adulthood: Findings from a prospective birth cohort study. Prev Med 138(2):106157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106157

Cefalo R, Scandurra R, Kazepov Y (2020) Youth labor market integration in European regions. Sustainability 12(9):3813. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093813

Cemalcilar Z, Secinti E, Sumer N (2018) Intergenerational transmission of work values: A meta-analytic review. J Youth Adolesc 47:1559–1579

Cinalli M, Giugni M (2013) New challenges for the welfare state: the emergence of youth unemployment regimes in Europe? Int J Soc Welf 22(3):290–299

Cornish C (2023) Exclusion by design: uncovering systems of segregation and ‘ghettoization’ of so-called NEET and ‘disengaged’ youth on an employability course in a further education (FE) college. J Youth Stud 26(4):456–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2021.2010690

Dayioglu M, Küçükbayrak M, Tumen S (2022) The impact of age-specific minimum wages on youth employment and education: a regression discontinuity analysis. Int J Manpow 43(6):1352–1377. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-02-2021-0079

Dorsett R, Lucchino P (2014) Explaining patterns in the school-to-work transition: an analysis using optimal matching. Adv Life Course Res 22(3):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2014.07.002

Dumouilla A, Botella M, Gillet M, Joncheray H, Guegan J, Robieux L, Bordes P, Collard L, Hodzic S, Sovet L, Lubart T, Zenasni F (2021) Comparison of social representations of NEETs in active young French adults and NEETs themselves. Br J Guid Couns 49(3):333–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2021.1900776

Eichhorst W, Rinne U (2017) The European youth guarantee: a preliminary assessment and broader conceptual implications. CESifo Forum 18:34–38

Eichhorst W, Marx P, Wehner C (2017) Labor market reforms in Europe: towards more flexicure labor markets? J Labour Mark Res 51(3):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12651-017-0231-7

Erdogan E, Flynn P, Nasya B, Paabort H, Lendzhova V (2021) NEET rural–urban ecosystems: the role of urban social innovation diffusion in supporting sustainable rural pathways to education, employment, and training. Sustainability 13(21):12053. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112053

Esping-Andersen G (1989) The three political economies of the welfare state. Can Rev Sociol/Rev Can De Soc 26(1):10–36

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (2022) NEETs. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/topic/neets

Farrugia D (2016) The mobility imperative for rural youth: the structural, symbolic and non-representational dimensions rural youth mobilities. J Youth Stud 19(6):836–851. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1112886

Finlay I, Sheridan M, McKay J, Nudzor H (2010) Young people on the margins: in need of more choices and more chances in twenty‐first century Scotland. Br Educ Res J 36(5):851–867. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920903168532

Focacci CN (2020) You reap what you sow”: Do active labour market policies always increase job security? Evidence from the Youth Guarantee. Eur J Law Econ 49(3):373–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-020-09654-6

Furlong A (2006) Not a very NEET solution. Work, Employ Soc 20(3):553–569. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017006067001

García-Fuentes J, Martínez García JS (2020) Los jóvenes “Ni-Ni”: Un estigma que invisibiliza los problemas sociales de lajuventud.Educ Policy Anal Arch 28(20):1–25. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.28.4652

Goldman-Mellor S, Caspi A, Arseneault L, Ajala N, Ambler A, Danese A, Fisher H, Hucker A, Odgers C, Williams T, Wong C, Moffitt TE (2016) Committed to work but vulnerable: self-perceptions and mental health in NEET 18-year olds from a contemporary British cohort. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 57(2):196–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12459

Görlich A, Katznelson N (2015) Educational trust: relational and structural perspectives on young people on the margins of the education system. Educ Res 57(2):201–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2015.1030857

Haikkola L (2021) Classed and gendered transitions in youth activation: the case of Finnish youth employment services. J Youth Stud 24(2):250–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2020.1715358

Hale DR, Viner RM (2018) How adolescent health influences education and employment: investigating longitudinal associations and mechanisms. J Epidemiol Community Health 72(6):465–470. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2017-209605

Heidenreich M, Bischoff G (2008) The open method of co‐ordination: a way to the europeanization of social and employment policies? JCMS: J Common Mark Stud 46(3):497–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2008.00796.x

Heidenreich M, Zeitlin J (2013) Changing European employment and welfare regimes: The influence of the open method of coordination on national reforms. Routledge

Holmes C, Murphy E, Mayhew K (2021) What accounts for changes in the chances of being NEET in the UK? J Educ Work 34(4):389–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2021.1943330

Howlett M, Mukherjee I (2014) Policy design and non-design: towards a spectrum of policy formulation types. Politics Gov 2(2):57–71. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v2i2.149

Juberg A, Skjefstad NS (2019) NEET’ to work? – substance use disorder and youth unemployment in Norwegian public documents. Eur J Soc Work 22(2):252–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1531829

Karaoglan D, Begen N, Tat P (2022) Mental health problems and risky health behaviors among young individuals in Turkey: the case of being NEET. J Ment Health Policy Econ 25(3):105–117

Kelly E, McGuinness S (2015) Impact of the Great Recession on unemployed and NEET individuals’ labour market transitions in Ireland. Econ Syst 39(1):59–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2014.06.004

Klug K, Drobnič S, Brockmann H (2019) Trajectories of insecurity: Young adults’ employment entry, health and well-being. J Vocat Behav 115(1):103308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.05.005

Lavenex S (2004) EU external governance in ‘wider Europe’. J Eur Public Policy 11(4):680–700

Lawy R, Quinn J, Diment K (2010) Responding to the ‘needs’ of young people in jobs without training (JWT): some policy suggestions and recommendations. J Youth Stud 13(3):335–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260903447544

Leavey G, McGrellis S, Forbes T, Thampi A, Davidson G, Rosato M, Bunting B, Divin N, Hughes L, Toal A, Paul M, Singh SP (2019) Improving mental health pathways and care for adolescents in transition to adult services (IMPACT): a retrospective case note review of social and clinical determinants of transition. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 54(8):955–963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01684-z

Lőrinc M, Ryan L, D’Angelo A, Kaye N (2020) De-individualising the ‘NEET problem’: an ecological systems analysis. Eur Educ Res J 19(5):412–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904119880402

Luca G, de, Mazzocchi P, Quintano C, Rocca A (2020) Going Behind the high rates of NEETs in Italy and Spain: the role of early school leavers. Soc Indic Res 151(1):345–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02370-3

MacDonald R (2011) Youth transitions, unemployment and underemployment. J Sociol 47(4):427–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783311420794

MacIntyre G (2014) The potential for inclusion: young people with learning disabilities experiences of social inclusion as they make the transition from childhood to adulthood. J Youth Stud 17(7):857–871. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.878794

Madia JE, Obsuth I, Thompson I, Daniels H, Murray AL (2022) Long‐term labour market and economic consequences of school exclusions in England: Evidence from two counterfactual approaches. Br J Educ Psychol 92(3):801–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12487

Maguire S (2010) I just want a job’ – what do we really know about young people in jobs without training? J Youth Stud 13(3):317–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260903447551

Maguire S (2015) NEET, unemployed, inactive or unknown – why does it matter? Educ Res 57(2):121–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2015.1030850

Malo MÁ, Mussida C, Cueto B, Baussola M (2023) Being a NEET before and after the Great Recession: persistence by gender in Southern Europe. Socio-Econ Rev 21(1):319–339. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwab043

Manhica H, Lundin A, Danielsson A-K (2019) Not in education, employment, or training (NEET) and risk of alcohol use disorder: a nationwide register-linkage study with 485 839 Swedish youths. BMJ Open 9(10):e032888. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032888

Margetts H, Hood C (2016) Tools approaches. In B. Peters & P. Zittoun (Eds.), Contemporary Approaches to Public Policy: Theories, Controversies and Perspectives (pp. 133–154). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50494-4_8

Mascherini M (2019) Origins and future of the concept of NEETs in the European policy agenda. In J. O'Reilly, J. Leschke, R. Ortlieb, M. Seeleib-Kaiser & P. Villa (Eds.), Youth Labor Transit (pp. 503–529). Oxford University Press

Mascherini M, Ledermaier S (2016) Exploring the diversity of NEETs. Eurofound. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Mauro JA, Mitra S (2020) Youth idleness in Eastern Europe and Central Asia before and after the 2009 crisis. Appl Econ 52(15):1634–1655. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.1677848

Mawn L, Oliver EJ, Akhter N, Bambra CL, Torgerson C, Bridle C, Stain HJ (2017) Are we failing young people not in employment, education or training (NEETs)? A systematic review and meta-analysis of re-engagement interventions. Syst Rev 6(1):b829. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0394-2

Maynou L, Ordóñez J, Silva JI (2022) Convergence and determinants of young people not in employment, education or training: An European regional analysis. Econ Model 110(1):105808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2022.105808

Mellberg C, Minas R, Korpi T, Andersson L (2023) Effective local governance assisting vulnerable groups: the case of youth not in employment, education or training (NEETs) in Sweden. Int J Soc Welf 32(1):20–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12527

Mujčinović A, Nikolić A, Tuna E, Stamenkovska IJ, Radović V, Flynn P, McCauley V (2021) Is it possible to tackle youth needs with agricultural and rural development policies? Sustainability 13(15):8410. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158410

Mussida C, Sciulli D (2023) Being poor and being NEET in Europe: Are these two sides of the same coin? J Econ Inequality 21:463–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-022-09561-7

O’Reilly J, Eichhorst W, Gábos A, Hadjivassiliou K, Lain D, Leschke J, McGuinness S, Kureková LM, Nazio T, Ortlieb R, Russell H, Villa P (2015) Five Characteristics of Youth Unemployment in Europe. SAGE Open 5(1):215824401557496. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015574962

Odoardi I (2020) Can parents’ education lay the foundation for reducing the inactivity of young people? A regional analysis of Italian NEETs. Econ Polit 37(1):307–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-019-00162-8

Palmer AN, Small E (2021) COVID-19 and disconnected youth: Lessons and opportunities from OECD countries. Scand J Public Health 49(7):779–789. https://doi.org/10.1177/14034948211017017

van Parys L, Struyven L (2013) Withdrawal from the public employment service by young unemployed: a matter of non-take-up or of non-compliance? How non-profit social work initiatives may inspire public services. Eur J Soc Work 16(4):451–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2012.724387

Pemberton S (2008) Tackling the NEET generation and the ability of policy to generate a ‘NEET’ solution—Evidence from the UK. Environ Plan C: Gov Policy 26(1):243–259. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0654

Pesquera Alonso C, Muñoz Sánchez P, Iniesta Martínez A (2021) Youth guarantee: looking for explanations. Sustainability 13(10):5561. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105561

Petrescu C, Ellena AM, Fernandes-Jesus M, Marta E (2022) Using evidence in policies addressing rural NEETs: common patterns and differences in various EU countries. Youth Soc 54(2_suppl):69S–88S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X211056361

Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA (2014) A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods 5(4):371–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123

Pinto Pereira SM, Li L, Power C (2017) Child Maltreatment and Adult Living Standards at 50 Years. Pediatrics 139(1):e20161595. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1595

Pitkänen J, Remes H, Moustgaard H, Martikainen P (2021) Parental socioeconomic resources and adverse childhood experiences as predictors of not in education, employment, or training: a Finnish register-based longitudinal study. J Youth Stud 24(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1679745

Quinn J (2013) New learning worlds: the significance of nature in the lives of marginalised young people. Discourse: Stud Cult Polit Educ 34(5):716–730. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2013.728366

Raghupathi V, Raghupathi W (2020) The influence of education on health: an empirical assessment of OECD countries for the period 1995–2015. Arch Public Health 78(1):95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-020-00402-5

Raileanu Szeles M, Simionescu M (2022) Improving the school-to-work transition for young people by closing the digital divide: evidence from the EU regions. Int J Manpow 43(7):1540–1555. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-03-2021-0190

Ralston K, Everington D, Feng Z, Dibben C (2022) Economic inactivity, not in employment, education or training (NEET) and scarring: the importance of NEET as a marker of long-term disadvantage. Work, Employ Soc 36(1):59–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017020973882

Rambla X, Scandurra R (2021) Is the distribution of NEETs and early leavers from education and training converging across the regions of the European Union? Eur Soc 23(5):563–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1869282