Abstract

This article aims to reveal the domestic implications of China’s digital diplomacy by centring the interaction between official diplomatic discourses and Chinese nationalist sentiments. Examining diplomatic discourse presented by Chinese foreign affairs spokespersons and the related nationalist comments of the Chinese domestic audience, this study illustrates the dynamic interplay between official diplomatic discourses, the salience of other, and nationalist sentiments. The findings suggest that China’s digital diplomatic discourse can influence the dynamic of domestic nationalist sentiments. A positive diplomatic tone contributes to more positive nationalist sentiments through an enhanced sense of national identification. Conversely, a negative tone of diplomatic discourse tends to generate more negative nationalist sentiments through intensified social comparison and derogation, particularly in the presence of salient foreign others. The study puts forward the theoretical commensurability between digital diplomacy, social identity theories, and nationalism construction. It also offers practical insights into China’s multifaceted nationalist communication and digital diplomacy strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The 21st century has witnessed China’s substantial investment to enhance global outreach and influence. Public diplomacy, primarily understood as a country’s engagement and investment that target foreign publics (Cull 2010), has become one essential component of China’s overall diplomatic strategy in recent years (Hartig 2016). Parallel to this diplomatic approach is China’s growing use of digital communication tools, a phenomenon referred to as “digital diplomacy,” to exceed conventional diplomatic practices. China’s evolving digital diplomacy constitutes a pivotal element of China’s construction of public diplomacy strategy, contributing to the overall process of China’s rise (Zhang and Ma 2022). Meanwhile, with the adoption of China’s national plan to defend its “discourse power” against distorted narratives, China is increasingly resorting to a more confident, assertive and firmer rhetoric in diplomacy. For instance, fronting with the foreign press, Chinese foreign affairs spokespersons often respond with strong criticism towards the decoupling and confrontation from the West with China, and defend China’s policies combatively. The assertive diplomatic messages have not only been transmitted to Twitter for foreign digital publics, but also been presented by domestic media to reach the Chinese digital audience. Under the context of “Tell China’s Story Well”, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) has been actively present on Chinese major social media. However, the current discussion of China’s digital diplomacy mainly focuses on its external impact on the foreign public, whilst there is a relative scarcity of scholarly attention to how China’s digital diplomacy impacts its domestic audience.

The diplomatic assertiveness has raised many international concerns about China’s rising nationalism (Johnston 2017; Weiss 2019) and the internet has become a commonplace for nationalist discussion. However, most of the scholarly focus is mainly on high-profile international conflicts and disputes, which often trigger nationalist movements. This may lead to the difficulty of gaining a full picture of nationalist sentiments (Zhang et al. 2018). Moreover, in a broader context of China’s engagement with the international community, various foreign issues, external “others” encountered and the corresponding diplomatic responses may exert nuanced influence on the domestic nationalist response. There is, therefore, a need to further explore the daily expressed nationalist sentiments within the nuanced impacts of Chinese diplomatic discourse.

The aim of our article is thus to study the impact of the digital diplomatic discourse on the domestic audience, specifically focusing on nationalist sentiments as the central theme. To this end, this paper draws upon the Social Identity Theory (SIT) to investigate the two dimensions of nationalist sentiments, namely national identification and social derogation. It combines discourse analysis, sentiment analysis, and quantitative methods to examine the interplay between foreign affairs spokespersons’ diplomatic discourse, public perception of “self” and salient “others”, and nationalist sentiments. By incorporating SIT into the analysis of nationalism, the study represents how official diplomatic discourses shape domestic nationalism from a social psychology perspective. Furthermore, with an examination of the daily interaction between official discourses and the public, this research facilitates the multifaceted understanding of Chinese nationalism and the nuanced influence of digital communication on the complex landscape of nationalist sentiments.

This article is structured as follows. The first section presents the existing literature and gaps on Chinese digital diplomacy and nationalism. The second section develops a conceptual scheme that links all potential variables, followed by the third section where we introduce the method, research data and measurement. Section four uses a series of multivariate models to test the influence path of the variables. In the final section, based on the empirical results, we offer some concluding thoughts and suggest avenues for further research.

Literature review

Public diplomacy, digital diplomacy and audience

The initial academic definition of public diplomacy focused on its direct communication with foreign peoples, aiming at affecting their thinking and, ultimately, that of their governments” (Malone 1985:199). Later definitions identified the object of public diplomacy, most of the definitions agreed that the public diplomacy targeted foreign publics (Vickers 2004), as well as their foreign policy decisions (Signitzer 2008). With the development of new technologies, states are offered opportunities to conduct online international communication, contributing to the rise of “digital diplomacy”. The digital transformation in the diplomatic arena has been widely recognised as to shift the traditional public diplomacy and forms a crucial component of the “new” public diplomacy (Zhang and Ma 2022), evident in the emergence of various terminologies such as public diplomacy 2.0 (Cull 2011), digital public diplomacy (Huang 2022), and virtual statecraft of public diplomacy (Williamson and Kelley 2012).

The digitalisation of public diplomacy has challenged the minimalist definition of public diplomacy in recent scholarship (Fallon and Smith 2022) since it has speeded up the “digital blurring of the foreign and the domestic” (Bjola et al. 2019: 85–86). Digital diplomatic communication can be targeted at “foreign audience” (Bjola 2016) and “foreign publics” (Bjola and Jiang 2015), but it can also reach the “general public” (Lewis 2014), “audience they seek to influence” (Adesina 2017), “digital public” (Zhang, Ong’ong’a (2021)), and “mass audience” (Luqiu and Yang 2020). A growing scholars recognised the previously overlooked domestic dimension of public diplomacy in the literature, adopting the notion “two-level game” (Fallon and Smith 2022) to indicate that public diplomacy is not exclusively about states projecting towards foreign audiences, but also involves interaction between a state and its domestic audiences.

Despite that, the current discussion on Chinese digital diplomacy still centers around China’s external impacts on foreign audience. These scholarly contributions mainly include China’s achievement in promoting its soft power (D’Hooghe (2005)), cultivating a favourable national image (Hartig 2016; Wang 2008; Chang and Lin 2014), integrating with the world harmoniously (Zhao 2019), and legitimizing itself with foreign audiences (Repnikova and Chen 2023). There is also increasing research revealing the unwanted effects resulting from China’s assertive rhetoric, including the “sharp power” as a consequence of manipulative use of information (Nye 2017) and unfavourable image of the “wolf warrior diplomacy” (Martin 2021; Mattingly and Sundquist 2022). These external impacts are often studied by investigating online activities conducted by Chinese state-led media and MFA on foreign social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter (e.g., Vila Seoane 2023; Alden and Chan 2021).

When transferring digital diplomatic discourse to domestic audience, Chen (2023) introduced the concept of “mediated/transmitted diplomacy” to denote the process wherein state-owned media transmit diplomatic messages to shape the discussion of digital publics. In this respect, a small strand of the existing research examined the domestic implications of digital diplomacy through the prism of political legitimacy. Bjola et al. (2019: 90) argued that digital technologies, from a public diplomacy perspective, can help foreign policy institutions to engage with the national citizenry, seeking public support for diplomatic policies and translating it into political backing. Yang (2020) further explained that China’s public diplomacy helps accrue legitimacy for the country at home. Huang (2022) contends that China’s digital public diplomacy efforts contributed the state to maintaining its dominant power domestically and conquering discursive power internationally. Further, according to Sullivan and Wang (2023), this process may foreground the domestic mechanism of representative communications.

Chinese nationalism and foreign relations

The first strand of literature on the dynamic interplay between Chinese nationalism and foreign relations follows the top-down approach, examining how nationalistic narratives structured by state or government are transferred to individuals with the assistance of the modern media system (Chen et al. 2019). Abundant sources contributing to patriotic education and national identity construction in China have been noted, such as the publication of “China Can Say No”, news coverage of events such as the Olympic Games and National Day military parade, and discursive use of symbols like “Motherland” (Pan 2018). With technological development, discursive construction by elites accounts for the prevailing Chinese cyber-nationalism (Schneider 2018). Many scholars also quantitatively demonstrated the impact of online political expression on public nationalist sentiments. For instance, Hyun and Kim (2014) declared that online political discourse can enhance public support for the existing sociopolitical system through nationalism. Zhang and Xu (2023) found that official expression constructed nationalism embodied in the media’s constructed social reality.

The second strand of literature follows the bottom-up approach, highlighting the crucial role of daily nationalist sentiments and self-initiated patriotic consciousness (Chen 2023) in shaping foreign policies and external relations. The bottom-up nationalist movements often raise scholarly concerns that China would make popular nationalism for aggressive foreign policy use (Hughes 2017), indicating that the pressure posed by assertive or aggressive nationalist public opinion may hijack the central government and its foreign policy-making (Chubb 2018; Gries 2004; Quek and Johnston 2018). More recent studies discussed that Chinese diplomatic posture is often received as an appropriate demonstration of China’s fighting for its interests against outside provocations and therefore satisfies the domestic preferences for popular nationalism (Sullivan and Wang 2023).

Despite the typological differences, top-down and bottom-up approaches to constructing Chinese nationalism are not mutually exclusive. The evolution of Chinese nationalism can be attributed to the dynamic interplay between the state and society (Modongal and Lu 2016), and is the result of interaction between different stakeholders, including state and individuals (Schneider 2018). Empirical studies also show that the construction of Chinese nationalism online follows a two-way direction (Chen et al. 2019) and is embedded in both social and political characteristics of individuals (Tang and Darr 2012). It is noteworthy that we do not inherently dismiss the efforts of either the top-down or the bottom-up approach. In this paper, the objective is not only to illustrate how digital diplomatic discourses, as presented by Chinese foreign affairs spokespersons, influence nationalist sentiments among the Chinese digital public, but also to incorporate elements of social identity theories, such as the public perception of salient foreign others.

Reflections on literature

Among the extensive literature, this article aims to fill in literature gaps and provide empirical support in the following ways. Firstly, compared to its external influence, the domestic setting of digital diplomacy is arguably conceptually undeveloped (Fallon and Smith 2022). Moreover, the existing scholarship on the domestic implications of digital diplomacy mainly focuses on China’s largest social media Weibo, whereby the more traditional communication style of text-based post and non-live comment may hinder the active participation of audience in discussion or instant expression of their sentiments. In this article, we endeavour to analyse the domestic nationalist reactions to the digital diplomatic discourses presented by MFA spokespersons, which are, through the Chinese social media channel Bilibili, transferred to China’s domestic digital population. Bilibili, together with its unique interaction mode of bullet screen, provides an ideal place to study the “real-time” reaction and interaction of viewers. It helps us adopt a more micro-level perspective to scrutinize the interaction between discursive elements, foreign affairs, and public perception of “self” and “other”. Below we build a theoretical model that explores these potential factors.

Secondly, a great majority of scholarship examines the dynamic of nationalism under the context of international conflicts and the subsequent mobilisation and protests, while scant attention has been paid to daily and routinized nationalist expressions. As Zhang et al. (2018) declared, a significant portion of empirical research on Chinese nationalism heavily leans on case studies, with some scholars delving into single high-profile issues such as the Diaoyu Islands dispute, and others focusing on critical junctures such as Covid-19. Although major international conflicts indeed can trigger nationalist movements, they may lead to the ongoing scholarly worries of the “audience cost” of nationalism (Weiss 2019; Sinkkonen 2013; Zhao 2014). Moreover, it is hard to gain a full picture of nationalist sentiments if we look at sorely international conflicts. Under the broader context of China’s engagement with the international community, nationalism should be multi-faceted (Guo et al. 2007) resulting from the dynamic international environment and China’s international status. Additionally, under the context of highly sensitive political topics, netizens may be reluctant to give comments. There is, therefore, a need for further exploration into the subtle operation of nationalism expression in individuals’ daily routines, as articulated by the concept of “latent nationalism” (Guo et al. 2007). To facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of Chinese popular nationalism, this article seeks to examine diverse foreign affairs topics, scrutinise the corresponding official statements, and understand the daily expressed public nationalist sentiments within the context where nationalist discussion naturally occurs.

Thirdly, an important concentration shared by the literature on the impact of digital diplomacy on domestic nationalism is the so-called “wolf warrior diplomacy”, highlighting the offensiveness (Zhu 2020) and confrontational approach (Martin 2021: 3) of Chinese diplomats presented on foreign social media. This focus may overshadow various other factors present in China’s contemporary digital diplomatic discourse. For instance, in response to French President Emmanuel Macron’s appeal for Europe and the U.S. to supply vaccines to developing countries to prevent Russia and China from extending their influence over these nations. Chinese foreign affairs spokesperson not only expressed China’s “welcome and support for the provision of vaccines by European countries and the USA to African nations”, but also outlined China’s ongoing efforts and plans to contribute to the anti-Covid efforts in Africa. Public comments showed, on the one hand, positive nationalist sentiments such as pride, appreciation, and affection, as well as horizontal comparisons with Western countries to showcase the prestige China gains from assuming international responsibilities as a major global power, on the other. To shed light on the broader impact of Chinese digital diplomatic discourse on domestic nationalism, our article endeavours to conduct a sentiment analysis of the diplomatic tones and go beyond the examination of the “hard” facet of Chinese diplomatic discourse.

Theoretical framework

We argue that both official diplomatic discourses and attributes of foreign events influence public perceptions about one’s own country and the other countries, driving the nationalist sentiments of the domestic audience. This study is designed to not only test the direct impact of these potential variables on nationalism, but also investigate the indirect impact and influence path of them. We develop a framework that links all elements which can be schematically represented in Fig. 1. Below we unpack the potential relationships among these variables.

Official diplomatic discourse and nationalism

Firstly, we look at the official diplomatic discourse with our overall thesis being that it will have impacts on the domestic audience’s nationalism. Official diplomatic discourse specifically refers to the remarks of China’s foreign affairs spokespersons presented officially at the regular press conference of the MFA, rather than their personal comments. These remarks can be seen as the official diplomatic stance toward a specific country or foreign policy choices, because a considerable amount of literature has convinced that the statements made by the spokesperson at the regular press conference serve as both external and internal official political communication functions (Wu 2020).

Given our particular interest in the domestic function of digital diplomatic discourse, we thus need to examine what message these diplomatic discourses deliver to the public regarding the diplomatic events and the self-other relationship involved. Therefore, the transmission of optimistic diplomatic messages to the audience regarding foreign events and the external others involved is anticipated to foster a corresponding positive trend in nationalist sentiments, while conversely, less favourable messages may yield negative implications.

Hypothesis 1. Positive official diplomatic discourse will increase the likelihood of domestic audience exhibiting positive nationalist sentiments.

Mediating effect of the national identification and social derogation

Hypothesis 1 suggests a positive impact of the positive official diplomatic discourse on the overall positivity of nationalist sentiments. Furthermore, to elucidate the mechanism through which official diplomatic discourse impacts domestic nationalist sentiments, we estimate that the narrative construction of the self-other relationship plays a pivotal role. In other words, the influence is disseminated via two dimensions of nationalism: national identification and social derogation.

The statement is derived from our induction of social identity theory (SIT) and characteristics of nationalism. SIT, as articulated by Hogg (2016), highlights significantly the distinction between the in-group and relevant out-groups in a particular context, which enhances its capacity to explain nationalism, as evidenced by numerous scholarly contributions (e.g. Gries 2005; Huddy and Khatib 2007; Li and Brewer 2004; Mummendey et al. 2001). According to SIT, the motivation for positive intergroup distinctiveness and self-enhancement (Tajfel and Turner, 1979), results in in-group favouritism and out-group derogation (e.g. Huddy 2001; Meeus et al. 2010). This framework aids in elucidating the characteristics of nationalism, as described by Blank and Schmidt (2003): (a) Idealization of the nation; (b) Sense of national superiority; (c) Uncritical acceptance of state and political authority; (d) Excessive emphasis on the attribution of the nation in the individual self-concept; (e) Suppression of ambivalent attitudes towards the nation; (f) Self-identifying; (g) Homoplasy; (h) Social derogation towards groups not considered part of the nation. Based on the delineation of national self-concept and the conduct of intergroup comparisons, we propose that these characteristics can be categorized as national (in-group) identification (d, e, f, and g), and social (out-group) derogation (a, b, c, and h).

Moreover, we assume that national identification includes a positive facet of nationalist sentiments. The positive aspect of nationalist sentiments mainly stems from in-group affection (Chen et al. 2019), revolving around concepts such as patriotism, belonging to a country (Keillor et al. 1996), confident nationalism (Oksenberg 1986), national pride, and inclusion. In contrast, social derogation tends to focus on the out-group. This would encompass relatively negative nationalist sentiments such as history of humiliation (Schneider 2018, Callahan 2006, Gries 2004), out-group hostility (Callahan 2010), cross-national comparison, hawkishness, and exclusion. It’s noteworthy that the use of the term “positive” here might raise concerns, as patriotic sentiments can occasionally lead to negative outcomes such as violence and social intolerance. Accordingly, during the subsequent content analysis, we took special care to evaluate the discourse’s positive or negative attributes based on its potential social implications.

We expect that the impact of official diplomatic discourse on nationalism is conducted through two mediating effects of social derogation and national identification.

Hypothesis 2. Social derogation will mediate the effect of official diplomatic discourse on nationalism. Namely, negative discourse will lead to more negative nationalism by increasing the level of social derogation.

Hypothesis 3. National identification will mediate the effect of official diplomatic discourse on nationalism. This means positive discourse will lead to more positive nationalism by raising the level of national identification.

Moderating effect of the salience of other

Although official diplomatic discourse may influence the domestic audience’s nationalism through the mediating effects, the degree of the effects can vary with the engaged actors in the foreign events, that is, in our article, the salience of other. Drawing upon the SIT, Gries (2005) argues that international competition and conflict occur only when there is a consequential zero-sum comparison with the salient other. In other words, the salience of other plays an important role in triggering international competitions and consequently shaping nationalist sentiments.

The first question is, what is the otherness of Chinese nationalism? The existing literature suggests that understanding Chinese nationalism requires to understand the dynamic relationship between China and the West (Li 2019; Zhao 2014). Not surprisingly, the collective memories of past humiliation that China suffered from the Western (Japanese) imperialists have been long shaped a victimisation sentiment towards the West and Japan (Callahan 2010; Gries 2004). Since late 20th century, the nationalism was characterised by a growing anti-West sentiment and diplomatic assertiveness (Zheng 1999: 1). Moreover, with the geopolitical turn of Chinese nationalism since 2008 (Hughes 2011: 602), the otherness of Chinese nationalism is targeting increasingly Western liberalism and the U.S.-dominated international order (Johnston 2017). Recent empirical research also proves that the sentiments of anti-West, anti-hegemony (Zhang 2019), and ideological competition between China and the West, especially the United States (Zhang 2022) remain dominant nationalist sentiments in Chinese digital sphere. Therefore, we assume that the West and Japan as the targeted salient others in our research.

The second question comes to what determines a salient other. According to Gries (2005), the salient other must be both external and a desirable object of comparison. Earlier researchers particularly highlighted the saliency of the threats from United States and Japan in the Chinese public’s minds (Chen 2001). In this study, however, we define the United States as the most salient other among the broader context of the West. Theoretically, this argument can be supported by high-profile political discourses and scholarly perspectives underscoring the U.S. as the principal actor in the process of decoupling and containment vis-à-vis China, in concert with its strategic partners such as Japan (e.g. Carlson et al. 2016). Practically, a survey conducted by the Center for International Security and Strategy at Tsinghua University (CISS 2023) indicated that the U.S. ranked as the most unfavorable country among Chinese public, followed by Japan, India, South Korea, European Union. To include all nation-actors involved in the foreign affairs that we collected, we position Australia, Canada, India, Japan, South Korea, United Kingdom as the second tier of salient others.

We suppose that when the external other is more salient, the positive impact between the positivity of official diplomatic discourse on the positivity of nationalism will be weakened because the mediating effect of social derogation will be more significant. Nevertheless, in the same situation, the positive relationship between nationalism and official diplomatic discourse will be weakened because the mediating effect of national identification will not work as significantly as when the external other is less salient. Hence, this study also tests whether the indirect association between official diplomatic discourse and nationalism will be moderated by salience of other. We estimate:

Hypothesis 4a. Salience of other will moderate the indirect effects of official diplomatic discourse on nationalism through social derogation. With a higher level of salience of other, the indirect effect will be enhanced.

Hypothesis 4b. Salience of other will moderate the indirect effects of official diplomatic discourse on nationalism through national identification. With a higher level of salience of other, the indirect effect will be weakened.

It is important to acknowledge that, due to the inherent limitations of cross-sectional observational designs, our assumption of the relationship between official diplomatic discourse, salience of other, and nationalism cannot definitively establish causality. Our research aims to discuss the possibility of influential directions of digital diplomatic discourse on domestic nationalist responses. The establishment of a potential influence path serves to enhance our understanding of the relationships among these variables, providing a foundation for future researchers to delve deeper into these dynamics.

Method

As Hughes (2005) argues, nationalism does not denote a concept or a movement, but rather a discursive theme, it is therefore necessary to identify the discursive elements and the interrelationships among them. This study combines qualitative and quantitative methods. With discourse analysis, sentiment analysis, and a multivariate regression model, we aim to examine the potential impact of digital diplomacy on domestic audience by creating a link among diplomatic discourse, foreign others and nationalist sentiments.

Data

Data were obtained from videos related to the regular press conferences posted on the Bilibili and the bullet screens of each video. We chose Bilibili and bullet screens as our research materials due to the following reasons. Firstly, Bilibili is an ideal digital place for gathering a large number of video clips related to MFA regular press conferences, with nearly 300 of them getting millions of views. Secondly, Bilibili is a representative of Chinese video-sharing community. The average age of Bilibili users is 22.8 years old, making it the online community with the highest concentration of college students (Bilibili 2022). Moreover, Bilibili’s user distribution aligns with the rankings of the top five provinces in China and the top five provinces by Gross Domestic Product (GDP), closely resembling China’s economic and population distribution (Bilibili 2022). Thirdly, the bullet screens culture in Bilibili allows us to comprehend the daily nationalist responses of viewers engaging in “real-time” discussions on foreign affairs and diplomatic discourses. As bullet screens only appear at specific points, precisely when the comments are made and inserted, they can more effectively reflect the audience’s reactions to a specific phrase or tone, thus providing knowledge of the “live” interaction of audience with both main characters and other viewers (Li 2017).

Videos in our dataset were selected based on the following criteria. Concerning the origin of videos, we took measures to guarantee the authenticity of each video, ensuring they were accurate records of the MFA’s regular press conferences. This can help us minimise the influence of individual interpretation and processing on the videos. Following the principle of universality, all videos selected have more than 50,000 views and over 100 bullet screens. Unlike the videos displayed on the highly personalized endless scrolling portal, trending and positive energy videos are not influenced by user preference or location (Chen et al. 2021). Following the principle of diversity, the time span is from 2019 to 2022, and the videos involve diplomatic events with different themes and objects. The variety of periods and diplomatic affairs allows us to grasp more comprehensively the daily nationalist expressions under the long-term of construction of diplomatic discourses. We finally selected 200 videos and Table 1 shows some examples of selected videos and their bullet screens.

After obtaining all video samples and discursive samples, we started the measuring and coding of variables. Firstly, we extracted all the bullet screens (122291 pieces of bullet screens in total) from each video with Python. Secondly, we used the most common Chinese word segmentation software in China - NLPIR system to form a self-defined nationalism lexicon dictionary. We selected nationalistic words applicable to this analysis to construct a nationalistic lexicon dictionary (with 544 words in total). Thirdly, all bullet screens that indicate nationalist sentiments were collected and coded by Gooseeker. It is an automated coding instrument and is also able to conduct textual analysis. Specifically, a machine learning algorithm automatically extracts text features to identify and classify attributes of a text. Machine learning is also equipped with the bag-of-words technique that tracks the occurrence of words in a text. It can also use neural networks to analyse words with similar meanings.

Variables

National identification and social derogation

For all nationalism lexicons, we first customized the two sets of keywords tags that categorize the nationalism lexicon as national identification (225 words) and social derogation (319 words) to build the coding scheme. We then code the national identification as 1 and the social derogation as −1. Next, we let Gooseeker identify the counts of frequencies of occurrence of these keywords in bullet screen discourses of each video. We calculated the percentages of frequencies of both kinds of categorization in each video. For example, national identification = 15.87% means that in a certain video, the bullet screens that involve “national identification” account for 15.87% of the total bullet screens. Similarly, social derogation = 32.16% means that in a certain video, the proportion of bullet screens that mention “social derogation” is 32.16%.

Nationalism

After identifying all bullet screens that contain obvious nationalist sentiment for each video as mentioned before, we used the Gooseeker to conduct sentiment analysis for all samples that fit the nationalism identification. This step was to extract the polarity, namely the positivity and negativity of the public nationalist sentiments. We adopted BosonNLP, the largest sentiment dictionary in China to identify and weigh the sentiment lexicon. We integrated our nationalism lexicon into the sentiment dictionary to develop a nationalist sentiment assessment system. Gooseeker then calculated the sentiment score of bullet screens for each video. If the score was larger than 5%, we coded this video as 1, because it indicated more positive nationalist sentiments; if the score was less than −5%, we coded this video as −1, because it was more likely to indicate negative nationalist sentiments. If the scale ranged from −5% to 5%, we coded it as 0 because the bullet screens had mixed and rather neutral nationalist sentiments. We thus designed an ordinal variable to reflect the positivity of nationalism of each video.

Official diplomatic discourse

There have been many scholarly efforts to evaluate the tone of political discourse and news reporting. The overall tone can be captured by sentiment lexicon coding (Young and Soroka 2012), with more positive tones increasing the inclination of voters to support (Hopmann et al. 2010). This supports our measurement of spokespersons’ attitudes toward a specific diplomatic issue. Keywords are selected based on the sentiment dictionary provided by BosonNLP and the Chinese Diplomatic Language Corpus edited by the China Academy of Diplomatic Discourse. It is worth noting that this may reduce the precision of the sentiment analysis, and we acknowledge that this is where the limitation of our study lies. However, we still coded whether the spokesperson’s depiction of the foreign issues - as likely perceived from his or her perspective- had a neutral or mixed (coded as 0), negative ( − 1), or positive (1) tone. Generally, if the spokesperson’s response is of condemnation, sarcasm, refutation, etc., it indicates a negative diplomatic tone and is coded as −1. A more positive diplomatic tone, which is coded as 1, is indicated if the speaker’s response contains appreciation, support, welcome, etc. If the spokesperson is merely stating facts or responding objectively, without any obvious emotional tendencies, it indicates a neutral diplomatic tone and is coded as 0. The coding reflects the positivity of official diplomatic discourse, making it an ordinal variable.Footnote 1

Salience of other

Based our above discussion on the otherness of Chinese nationalism, we assign different weights to different others based on their salience to China. Therefore, we coded the United States as 2, the most salient other, and Australia, Canada, India, Japan, South Korea, United Kingdom as 1, and all the rest as 0. This scale of salience makes salience of other an ordinal variable.

Statistical analysis

The analysis tool we used is PROCESS developed by Hayes (2012), which is a popular statistical tool for mediation and moderation analyses, as well as their combination. We tested our study hypotheses in three interlinked steps. First, the descriptive information and correlation matrix were calculated. Second, a mediation model was established. We finally test the moderating effect and build a moderated mediation model. Since that we treat all variables as continuous variables, therefore we employ ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. Robust standard errors are clustered by country to reduce heteroscedasticity.

Tests of mediation

We followed MacKinnon’s (2008) four-step procedure to test the two potential mediators. Step 1: we examined the significant direct effect of official diplomatic discourse on nationalism (Hypothesis 1). Step 2: a significant relationship between official diplomatic discourse and national identification, and that between official diplomatic discourse and social derogation. Step 3: a significant correlation between social derogation and nationalism and that between national identification and nationalism while controlling for official diplomatic discourse. Step 4: a significant coefficient for the indirect path between official diplomatic discourse and nationalism through national identification and social derogation (Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3). We also ensured that the last step satisfied the bootstrapping test of confidence intervals (CIs).Footnote 2 CIs that do not include zero indicate a significant effect (MacKinnon et al. 2004).

Tests of moderation

Concerning Hypothesis 4a and Hypothesis 4b, we predicted that the salience of other would moderate both the indirect effects of national identification and social derogation on official diplomatic discourse. Therefore, it is feasible to apply a moderated mediation model to test whether the magnitude of a mediation effect is conditional on the value of a moderator (Muller et al. 2005).

Results

Our findings unfold as follows. The mediation model firstly supported our Hypothesis 1 that official diplomatic discourse has a significant and positive impact on the positivity of the audience’s nationalist sentiments. The same model also demonstrated that the inverse relationship between official diplomatic discourse and social derogation mediates the total effect of official diplomatic discourse on nationalism, supporting our Hypothesis 2. While strong evidence for Hypothesis 3 was not obtained, the subsequent examination of the moderated mediation model reveals that both indirect effects via two mediators were significantly moderated by salience of other, supporting our Hypothesis 4a and 4b. This result explains the fact that the significance of the indirect effect via national identification depended on the value of salience of other. Hence, our Hypothesis 3 is partially supported.

Table 2 presents means, standard deviations, and the correlation matrix for all variables. Generally speaking, contrary to most scholars’ concerns, the majority of popular nationalist sentiments are positive (see Supplementary Fig. S1 online). An inspection of the correlations reveals that nationalism is positively related to official diplomatic discourse (r = 0.21, p < 0.01). We further discussed the impact of official diplomatic discourse on nationalism in the following mediation model. Moreover, nationalism is also positively related to national identification (r = 0.58, p < 0.001), whereas inversely related to social derogation (r = −0.71, p < 0.001).

Test of mediation

While Hypothesis 1 suggests a positive effect of positive official diplomatic discourse on positive nationalism, Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3 collectively suggest an indirect effect model, whereby the correlation between official diplomatic discourse and nationalism is transmitted by national identification and social derogation. Table 3 presents the results for Hypothesis 1, Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3. The total effect in Table 3 illustrates the significant impact of official diplomatic discourse on nationalist sentiments (B = 0.24, t = 2.99, p < 0.01), indicating more positive official diplomatic discourse is associated with a higher likelihood of domestic audience expressing more positive nationalist sentiments (also see Supplementary Table S2 online). The significance of total effect can also be shown by the bootstrapped 95% CI around the total effect not containing zero (0.08, 0.39). Hypothesis 1 was therefore supported.

In support of Hypothesis 2, as shown in Table 3, we proved that the indirect effect of official diplomatic discourse on nationalism through social derogation was significant (indirect effect =0.16), with a bootstrapped 95% CI around the indirect effect not containing zero (0.06, 0.25). In addition, the direct effect became insignificant as shown in Table 3. This indicated that the mediation model was indirect-only.Footnote 3

To our surprise, the indirect effect of national identification was insignificant (indirect effect =0.06) with a bootstrapped 95% CI around the indirect effect containing zero ([−0.01, 0.15]), which did not provide enough support for our Hypothesis 3. However, we did not deny the plausibility of Hypothesis 3 immediately. Hayes and Rockwood (2019) put forward that the test of moderation does not depend on the significance of the direct effect, and the test of moderated mediation does not require the significance of the mediating effect. It may be possible that the positive mediating effect via national identification is moderated by salience of other. Therefore, though the result does not fully support the mediating effect of national identification, we continued our test of the moderated mediation process in this effect path.

Test of moderated mediation

With regard to Hypothesis 4a and Hypothesis 4b, we predicted that with higher salience of other, the inverse relationship between official diplomatic discourse and social derogation will be stronger, and the positive relationship between official diplomatic discourse and national identification will be weaker. According to Hayes (2015), to test the significance of moderated mediation, it is necessary to examine whether the index of moderated mediation and the contrast between conditional indirect effects are significant. We used the information from the regression results (presented in Supplementary Table S4 online) to calculate simple effects at low and high levels of salience of other (see Table 4). As presented in Table 4, both the contrast and index of the indirect effect are significant with the bootstrap 95% CI not including zero ([−0.33, −0.03] and [−0.23, −0.02], respectively). When external others have a higher level of salience, the inverse effect of official diplomatic discourse on social derogation will be enhanced. On the contrary, with a lower level of salience, the inverse effect of official diplomatic discourse on social derogation will be less. Thus, Hypothesis 4a was supported.

Similarly, we tested the moderated mediating effect via national identification. Table 4 presents the significance of the moderated mediation, with both the contrast and index significant within the lower and higher level of salience of other (bootstrap 95% CI [−0.36, −0.10] and [−0.26,−0.07] respectively). Empirically, external others with a lower level of salience generated more positive nationalist sentiments via an enhanced indirect effect of official diplomatic discourse on national identification. Thus Hypothesis 4b was also supported.

Figure 2a, b present the plots of conditional effects of official diplomatic discourse on nationalism in paths through social derogation and national identification respectively. It can be inferred that the indirect effect via social derogation is much stronger than the direct effect, regardless of the level of salience of other. Concerning the indirect effect via national identification, however, it is only when the value of salience of other is smaller than 1.41 will the indirect effect surpasses the direct effect. However, the value of salience of other should be an integer ranging from 0 to 2, thus the condition holds only if the value is 0 or 1.

Following Preacher et al. (2007), we also used the Johnson- Neyman method to plot the conditional indirect effects of salience of other in Fig. 3a,b. According to the plots, the indirect effects are significantly far from 0 for any value of salience of other smaller than 1.49 and 1.14. The plots show that when the value of salience of other is 2, the indirect effect via social derogation can still have a role to play, but the indirect via national identification will not appear. This result is in accord with our prediction that the indirect effect via national identification may be lower than zero because of the negative moderation of salience of other, which contributes to the insignificant indirect effect tested previously. It can partially support our Hypothesis 3 that the mediating effect of national identification is conditionally significant.

To investigate whether there is a possibility of alternative models, we used the PROCESS to conduct several tests to examine other potential effect paths. Firstly, we tested whether salience of other simultaneously moderated the second-stage indirect effects (path from social derogation and national identification to nationalism). Secondly, we tested whether salience of other moderated the direct effects. However, results could not support that neither second-stage effect paths nor direct effect was moderated by salience of other (see Supplementary Table S5 online). Our hypothesised mode thus provides tentative evidence for the influence path suggested here.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper presents an empirical study of the domestic impact of Chinese spokespersons’ official diplomatic discourse from the perspective of nationalism. We developed an integrated conceptual scheme with 5 hypotheses that the proposed potential impact of official diplomatic discourse on nationalism, the inner mechanism by which effects operate, and the factors that influence the strength of this mechanism. The findings of our research indicate that digital diplomatic discourses transferred to Chinese digital public are able to influence domestic nationalist sentiments. Spokespersons with a more positive tone will generate more positive nationalist sentiments, and the impact is conducted through a reinforced sense of national identification. Conversely, spokespersons with a more negative tone will drive more negative nationalist sentiments through a more intensive sense of social derogation. In addition, with higher levels of salience of other, the national sentiments will be more negative and vice-versa. The study has the following implications.

Nationalism as a domestic dimension of digital diplomacy

This research sheds light on the domestic implications of the state’s digital diplomatic strategy, especially in terms of nationalism construction. Abundant researchers have discussed the role that Chinese digital diplomacy plays towards the international public, either in her national image construction or, conversely, in the unwanted critics of “sharp power” and “wolf warrior diplomacy”. We demonstrate that digital diplomacy also works at home by shaping the domestic public perceptions of other social groups and their own national identification. The firmer, more assertive and confident diplomatic tone, though given pejorative connotations in Western interpretation, is however being reported, received, and often praised in the Chinese context as a powerful demonstration toward the unfriendly treatment by the outside world. The assertiveness of Chinese diplomats can have nuanced impacts on domestic nationalist sentiments through the intricate inner mechanism. In other words, the nationalist sentiments raised are not necessarily negative sentiments such as chauvinism or militarism, but can also be positive emotions such as affection and pride.

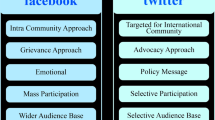

Moreover, this research offers practical insights into China’s digital diplomacy network on different social media carriers. Weibo, along with its “long Weibo” service, enables MFA to articulate China’s official stance towards diplomatic affairs through long texts. Twitter, however, given its word limit, necessitates Chinese diplomats to fragment and condense the long posts and maintain their tweets concise and accurate, and dynamic (Huang and Wang 2021). Compared to the relatively serious and restrained discourse found on Weibo and Twitter, our exploration into Bilibili has revealed a distinct feature of the MFA’s digital diplomacy practices. The videos of the MFA regular press conferences often incorporate discursive elements characterized by humorous language and references to internet popular culture. This is evident in the captivating titles of the videos, catchy buzzwords used by spokespersons such as “hilarious” (xiaodiao daya 笑掉大牙) and “shrug out” (hehe 呵呵), as well as striking rhetorical questions directed back at certain unfriendly inquiries. This has made the Bilibili an ideal platform to convey daily, light-hearted, and amusing expressions of nationalism to the domestic audience, especially when its user base primarily composed of youth who appreciate subcultural and entertaining styles. Moreover, this asymmetry in digital diplomatic practices may lead scholars to further consider China’s digital diplomacy strategies to deliver homogenous and coordinating discourses to different sets of publics, both internationally and domestically.

Towards a multi-faceted understanding of Chinese nationalism

In this article, we put forward the theoretical commensurability between social identity theories and nationalism, as previously discussed by Huddy (2001) and Meeus et al. (2010). Relying on the intergroup relationship, we disaggregated the abstract concept of nationalist sentiment into two dimensions, namely national identification and social derogation, and attributed the positive ingroup evaluation to the positive aspect of nationalist sentiments, whereas outgroup rejection into the negative facet of nationalist sentiments. Moreover, drawing upon Gries’ (2005) argument regarding the conditions under which international comparisons take place, we discussed the impact of the salience of foreign others on nationalism, and demonstrated empirically how it interacts with ingroup identification and out-group derogation. As shown in our research, when facing more salient external others, the Chinese netizen may place more emphasis on social comparison and derogation, which is more conducive to negative national sentiments. By integrating SIT into nationalism research, this study conceptually advances the nationalism analysis from the perspective of social psychology, and encourages future studies to examine nationalist sentiments via the logic of political identity and political psychology.

Moreover, this research addressed the literature gap between extensively studied “manifest nationalism,” which centres on high-profile nationalist events, and the relatively understudied “latent nationalism”, which focuses on daily and routinized nationalist cognition (Guo et al. 2007). By scrutinizing the audience reaction on Chinese foreign affairs across various topics and periods and the interaction between China’s foreign affairs spokespersons and the public, this study explored the daily and multifaceted nationalist communication through the lens of social psychology. This research invites more scholarly efforts on the quotidian nationalist discussion and online participation in China’s engagement with the international community. In this regard, the interaction mode of Bilibili also deserves more attention given its popularity among Chinese internet users and the uniqueness of youth subculture.

It is noteworthy that we do not deny the argument that China’s firmer and more assertive diplomatic discourses may lead to China’s rising nationalism and tougher foreign policy (Johnston 2017; Weiss 2019), and an increase in negative nationalist sentiment may deepen other countries’ doubt and fear of China’s rise. However, we do recognise that the state also possesses the capacity to mitigate the adverse effects of nationalism on decision-makers. This objective can be achieved, as previous scholars have observed, through strategies such as harnessing “positive energy” out of nationalism (Chen et al. 2021), or distancing itself from undesirable nationalism narratives (Zhang and Ma 2022).

Limitation and future research

Firstly, we acknowledge that socio-economic backgrounds would have a role to play in the audience’s predispositions. However, due to data privacy, we do not have access to the personal or contact information of bullet screen posters. Future researchers can conduct surveys to include the demographic variables or study the demographic discrepancy among different social media platforms to increase the scientificity of the research. Secondly, our attempts to quantify some of the variables, such as the tone of official diplomatic discourses, the positivity of nationalist sentiments, and the salience level of others, have mainly relied on subjective evaluation and automated machine learning. Whereas this does not invalidate the current research, future studies that include additional, more objective performance measures would enhance the robustness of our findings. Last but not least, all variables are treated as ordinal variables for the sake of the simplification of regression models. The moderated mediation model, for example, can be built as one with categorical variables in future studies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are included in the supplementary information, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Notes

To be precise, this ordinal variable is a qualitative variable. However, we treat it as a quantitative variable. This transition may lead to a loss of accuracy.

The bootstrapped CIs is to test whether an indirect effect has power problems introduced by asymmetric or other non-normal sampling distributions.

According to Hayes, the mediation analysis does not require that there be evidence of a simple association between X and Y. See Hayes A (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 76: 408–420. also see Hayes A and Rockwood N (2017) Regression-based mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav. Res. Ther. 98: 39–57.

References

Adesina OS (2017) Foreign Policy in an Era of Digital Diplomacy. Cogent Soc Sci 3(1):1297175

Alden C, Chan K (2021) Twitter and Digital Diplomacy: China and COVID-19 https://www.lse.ac.uk/ideas/Assets/Documents/updates/LSE-IDEAS-Twitter-and-Digital-Diplomacy-China-and-COVID-19.pdf

Blank T, Schmidt P (2003) National Identity in a united Germany: Nationalism or patriotism? an empirical test with representative data. Polit Psychol 24(2):289–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00323

Bilibili (2022) Analysis of bilibili user demographics. https://www.bilibili.com/read/cv15208692?from=search&spm_id_from=333.337.0.0

Bjola C, Jiang L (2015) Social media and public diplomacy: A comparative analysis of the digital diplomatic strategies of the EU, US and Japan in China, in C Bjola and M Holmes (eds.) Digital Diplomacy: Theory and Practice. London: Routledge

Bjola C (2016) Digital diplomacy – the state of the art. Glob Aff https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2016.1239372

Bjola C, Cassidy J, Manor I (2019) Public diplomacy in the digital age. Hague J Diplom 14(1-2):83–101. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-12341328

Callahan WA (2006) History, identity, and security: Producing and consuming nationalism in China. Crit Asian Stud 38(2):179–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672710600671087

Callahan WA (2010) China: The Pessoptimist Nation. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Carlson AR, Costa A, Duara P et al. (2016) Nations and Nationalism roundtable discussion on Chinese nationalism and national identity. Nations Nationalism 22(3):415–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12232

Chang T-K, Lin F (2014) From propaganda to public diplomacy: Assessing China’s international practice and its image, 1950–2009. Public Relat Rev 40(3):450–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.03.008

Chubb A (2018) Assessing public opinion’s influence on foreign policy: The case of China’s assertive maritime behavior. Asian Secur 15(2):159–179

Chen J (2001) Urban Chinese perceptions of threats from the United States and Japan. Public Opin Q 65(2):254–266

Chen KA (2023) Digital Nationalism: How do the Chinese Diplomats and Digital Public View “Wolf Warrior” Diplomacy? Glob Media China 8(2):138–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/20594364231171785

Chen X, Valdovinos Kaye DB, Zeng J (2021) PositiveEnergy Douyin: Constructing “Playful Patriotism” in a Chinese Short-Video Application. Chin J Commun 14(1):97–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2020.1860804

Chen Z, Su CC, Chen A (2019) Top-down or Bottom-up? A Network Agenda-setting Study of Chinese Nationalism on Social Media. J Broadcast Electron Media 63(3):512–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2019.1653104

CISS (2023) 2023 public opinion polls: Chinese outlook on international security. https://ciss.tsinghua.edu.cn/info/CISSReports/6145

Cull NJ (2010) Public diplomacy: Seven lessons for its future from its past. Place Brand Public Dipl 6(1):11–17. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2010.3

Cull NJ (2011) WikiLeaks, public diplomacy 2.0 and the state of digital public diplomacy. Place Branding Public Diplom 7:1–8

D’Hooghe I (2005) Public diplomacy in the People’s Republic of China. The New Public Diplomacy: 88–105

Fallon T, Smith NR (2022) The Two-Level Game of China’s Public Diplomacy Efforts. Routledge, London

Gries PH (2004) China’s New Nationalism: Pride, Politics, and Diplomacy. University of California Press, Berkeley

Gries PH (2005) Social Psychology and the Identity-Conflict Debate: Is a ‘China Threat’ Inevitable? Eur J Int Rel 11(2):235–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066105050572

Guo Z, Cheong WH, Chen H (2007) Nationalism as public imagination: The media’s routine contribution to latent and manifest nationalism in China. Int Commun Gaz 69(5):467–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048507080873

Hartig F (2016) How China Understands Public Diplomacy: The Importance of National Image for National Interests. Int Stud Rev 18(4):655–680. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viw027

Hayes AF (2012) An Analytical Primer and Computational Tool for Observed Variable Moderation, Mediation, and Conditional Process Modeling. http://www.Afhayes.com

Hayes AF (2015) An Index and Test of Linear Moderated Mediation. Multivar Behav Res 50(1):1–22

Hayes AF, Rockwood NJ (2019) Conditional process analysis: Concepts, computation, and advances in the modeling of the contingencies of Mechanisms. Am Behav Sci 64(1):19–54

Hogg MA (2016) Social identity theory. In: McKeown S, Haji R, and Ferguson N (ed) Understanding peace and conflict through social identity theory: Contemporary global perspectives. Springer International Publishing. p 3–17

Hopmann DN, Vliegenthart R, De Vreese C et al. (2010) Effects of election news coverage: How visibility and Tone Influence Party choice. Polit Commun 27(4):389–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2010.516798

Huang ZA (2022) “Wolf Warrior” and China’s Digital Public Diplomacy during the COVID-19 Crisis. Place Brand Public Dipl 18(1):37–40. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-021-00241-3

Huang ZA, Wang R (2021) Exploring China’s digitalization of public diplomacy on Weibo and Twitter: A case study of the US–China trade war. Int J Commun 15(2021):1912–1939

Huddy L (2001) From Social to Political Identity: A Critical Examination of Social Identity Theory. Pol Psychol 22(1):127–156

Huddy L, Khatib N (2007) American Patriotism, National Identity, and Political Involvement. Am J Polit Sci 51(1):63–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00244.x

Hughes CR (2005) Interpreting nationalist texts: A post-structuralist approach. J Contemp China 14(43):247–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670560500094945

Hughes C (2011) ‘Reclassifying Chinese Nationalism: The Geopolitik Turn’. J Contemp China 20:70. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2011.532433

Hughes CR (2017) Militarism and the China model: The case of national defense education. J Contemp China 26(103):54–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2016.1139054

Hyun KD, Kim J (2014) The role of new media in sustaining the status quo: Online political expression, nationalism, and system support in China. Inf Commun Soc 18(7):766–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.808363

Johnston AI (2017) ‘Is Chinese Nationalism Rising? Evidence from Beijing’. Int Secur 41(3):7–43. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00265

Keillor BD, Hult GTM, Erffmeyer RC et al. (1996) NATID: The development and application of a national identity measure for use in international marketing. J Int Mark 4(2):57–73

Lewis D (2014) Digital Diplomacy. http://www.gatewayhouse.in/digital-diplomacy-2/

Li H (2019) ‘Understanding Chinese Nationalism: A Historical Perspective’, in H. Liu (ed.) From Cyber-Nationalism to Fandom Nationalism: The Case of Diba Expedition in China. Routledge, pp. 13–31. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367819476-2

Li J (2017) The Interface Affect of a Contact Zone: Danmaku on Video-Streaming Platforms. Asiascape: Dig Asia 4(3):233–256. https://doi.org/10.1163/22142312-12340079

Li Q, Brewer MB (2004) What does it mean to be an American? Patriotism, nationalism, and American identity after 9/11. Polit Psychol 25(5):727–739

Luqiu LR, Yang F (2020) Weibo Diplomacy: Foreign Embassies Communicating on Chinese Social Media. Gov Inf Q 37(3):101477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2020.101477

MacKinnon D (2008) Introduction to Stat. Mediation Anal., 1st ed. Mahwah: Routledge

MacKinnon D, Lockwood CM, Williams J (2004) Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and Resampling Methods. Multivar Behav Res 39(1):99–128

Malone G (1985) Managing public diplomacy. Wash Q 8(3):199–213

Martin P (2021) China’s Civilian Army: The Making of Wolf Warrior Diplomacy. Oxford University Press

Mattingly DC, Sundquist J (2022) When Does Online Public Diplomacy Succeed? Evidence from China’s ‘Wolf Warrior’ Diplomats. Polit Sci Res Methods 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2022.41

Meeus J, Duriez B, Vanbeselaere N et al. (2010) The Role of National Identity Representation in the Relation Between In‐Group Identification and Out‐Group Derogation: Ethnic Versus Civic Representation. Br J Soc Psychol 49(2):305–320. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466609X464849

Modongal S, Lu Z (2016) Development of nationalism in China. Cogent Soc Sci 2(1), https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2016.1235749

Muller D, Judd CM, Yzerbyt VY (2005) When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. J Pers Soc Psychol 89(6):852–863. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852

Mummendey A, Klink A, Brown R (2001) Nationalism and patriotism: National identification and out‐group rejection. Br J Soc Psychol 40(2):159–172

Nye J (2017) How sharp power threatens soft power - The right and wrong ways to respond to authoritarian influence. Foreign Aff https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2018-01-24/how-sharp-power-threatens-soft-power

Oksenberg M (1986) China’s confident nationalism. FA 65(3):501–523

Pan X (2018) “祖国母亲”:一种政治隐喻的传播及溯源 (Motherland: The spread and traceability of a political metaphor). J Humanit (人文杂志) 1:92–102

Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF (2007) Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar Behav Res 42(1):185–227

Quek K, Johnston AI (2018) Can China back down? crisis de-escalation in the shadow of popular opposition. Int Secur 42(3):7–36

Repnikova M, Chen KA (2023) Asymmetrical Discursive Competition: China–United States Digital Diplomacy in Africa. Int Commun Gaz 85(1):15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/17480485221139460

Schneider F (2018) China’s Digital Nationalism. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Signitzer B (2008) Public relations and public diplomacy: Some conceptual explorations. In: Zerfass A, van Ruler B, Sriramesh K (eds) Public Relations Research. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-90918-9_13

Sinkkonen E (2013) Nationalism, patriotism and foreign policy attitudes among Chinese university students. China Q 216:1045–1063

Sullivan J, Wang W (2023) China’s “Wolf Warrior Diplomacy”: The Interaction of Formal Diplomacy and Cyber-Nationalism. J Curr Chin Aff 52(1):68–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/18681026221079841

Tajfel H, Turner JC (1979) An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In Austin WG and Worchel S (ed) The social psychology of intergroup relations. Brooks Cole, Monterey, p 33–47

Tang W, Darr B (2012) Chinese nationalism and its political and social origins. J Contemp Chin 21(77):811–826

Vickers R (2004) The New Public Diplomacy: Britain and Canada compared. Br J Polit Int Relat 6(2):182–194

Vila Seoane MF (2023) China’s Digital Diplomacy on Twitter: The Multiple Reactions to the Belt and Road Initiative. Glob Media Commun 19(2):161–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/17427665231185697

Wang Y (2008) Public diplomacy and the rise of Chinese soft power. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 616(1):257–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716208318866

Weiss JC (2019) How Hawkish is the Chinese Public? Another Look at “Rising Nationalism” and Chinese Foreign Policy. J Contemp China 28(119):679–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564. pp

Williamson WF, Kelley JR (2012) Kelleypd: Public Diplomacy 2.0 Classroom. Glob Media J 12(21):1

Wu H (2020) Engagement Resources in Diplomatic Discourse: With reference to remarks by Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson. US-China Foreign Lang 18(2):68–74

Yang Y (2020) Looking inward: How does Chinese public diplomacy work at home? Br J Polit Int Relat 22(3):369–386

Young L, Soroka S (2012) Affective news: The automated coding of sentiment in political texts. Polit Commun 29(2):205–231

Zhang D, Xu Y (2023) When nationalism encounters the COVID-19 pandemic: Understanding Chinese nationalism from media use and media trust. Glob Soc 37(2):176–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2021.1973506

Zhao K (2019) The China model of public diplomacy and its future. Hague J Diplom 14(1-2):169–181

Zhao S (2014) Foreign policy implications of Chinese nationalism revisited: The strident turn. Construct. Chin. Nationalism Early 21st Century, 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2014.918263

Zhang C (2019) Right-wing populism with Chinese characteristics? identity, Otherness and global imaginaries in Debating World Politics Online. Eur J Int Relat 26(1):88–115

Zhang C (2022) Contested disaster nationalism in the digital age: Emotional registers and geopolitical imaginaries in COVID-19 narratives on Chinese social media. Rev Int Stud 48(2):219–242

Zhang X, Ma Y (2022) China’s emerging digital diplomacy strategies. China’s Int Commun Relationship Build 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1145/3492037.3499235

Zhang Y, Liu J, Wen JR (2018) Nationalism on Weibo: Towards a multifaceted understanding of Chinese nationalism. China Q 235:758–783

Zhang Y, Ong’ong’a DO (2021) Unveiling China’s Digital Diplomacy: A Comparative Analysis of CGTN Africa and BBC News Africa on Facebook. Asian J Comp Politics 7(3):661–683. https://doi.org/10.1177/20578911211068217

Zheng Y (1999) Discovering Chinese nationalism in China: Modernization, identity, and international relations. Cambridge University Press

Zhu Z (2020) Interpreting China’s ‘wolf-warrior diplomacy’. Diplomat 15(5):2020

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by the State Scholarship Fund of China Scholarship Council. The funder had no role in the design and/or execution of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XWZ conceptualized, wrote, and revised the manuscript. YXT processed the data, edited, and revised the manuscript. These authors contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as this article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. Informed consent was not relevant.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Tang, Y. Digital diplomacy and domestic audience: how official discourse shapes nationalist sentiments in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 182 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02669-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02669-3