Abstract

The prevailing housing situation in Pakistan is alarming, as more than 47% of urban households are estimated to be living in squatters. Housing stakeholders require an enabling environment to collaborate to reduce the drastic inequity with too many housing options for the high-income and too few for the low-income groups. Existing literature reveals that Pakistan lacks stakeholder studies with a collaborative focus on providing low-income housing in urban areas. This study explores the barriers and impediments to stakeholder collaborations in the low-income housing sector through in-depth interviews within the urban setting of Lahore, the capital and the most populous city of the biggest province, Punjab, Pakistan. The findings identify the emergence of five cross-cutting collaboration challenges (GLIPP), placing government capacity, institutional complexity, and political willpower & intervention as dominant ones. This study stresses revising the organizational hierarchy of government institutions to develop a collaborative culture in the Pakistani housing sector. As part of practical implications, this paper would agitate policymakers to develop housing policies and programs for low-income groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

More than 20% of the world’s population faces a shortage of adequate housing, estimated at around 100 million homeless people (Adetooto and Windapo, 2022). There is an increased demand for affordable housing by low-income groups, which draws essential considerations on the resources and competencies of all stakeholders. For the projects to be well-connected with community needs, the various strengths of each involved stakeholder must be integrated with the development process, further ensuring feasibility and long-term affordability (Bratt, 2008). A recent study indicated a research knowledge gap and recommended developing a conceptual framework for barriers to sustainable affordable housing (Adabre et al., 2020). For housing development, such partnerships range from multi-stakeholder engagements, local and global level arrangements, short to long-duration strategies, and fully mandated voluntary basis (Selsky and Parker, 2005; Madden, 2011; Cleophas et al., 2019). Many practical barriers impede collaboration for low-income housing provision. Little literature is available about barriers to stakeholder collaboration in the context of low-income housing in developing countries. A recent study identified several factors impeding the sustainable provision of affordable housing for low-income groups, including fiscal constraints, cultural change, market limitations, knowledge limitations, institutional and legislative barriers, and technological difficulties (Ezennia, 2022). Williams and Dair (2007) found that the stakeholders involved in development and construction face knowledge-related barriers. Developers, builders, consultants, and academia are potential market stakeholders working within professional consultancy, labor, and building material supplies. Their decision-making practice is influenced by the configuration of their engagement patterns and values about land, property, buildings, and environments. Regarding funding issues, Average (2019) highlighted that the private sector avoids investing in low-income housing schemes as they regard it as a high-risk and low-return investment area; hence, the low-income groups are ruled out from participating in private sector projects because of their stringent framework insensitive to the urban poor conditions. The literature on collaboration barriers was explored under different housing contexts like sustainable housing development, affordable housing, and low-income housing (Table 1).

The above table highlights key factors acting as barriers to stakeholder collaborations. Such barriers fall mainly within government, policy, funding, legislation, political will, and environmental factors. Regulatory measures act as drivers for change within the government sector since these deal with important procurement matters for project tenders of housing development. Meehan and Bryde (2015) highlighted the role of officials within regulatory authorities in the procurement domain of sustainable housing. Their study exposed that “regulators’ network position affords no direct access to suppliers, contractors or tenants constraining knowledge creation, an essential factor for sustainable procurement in the sector.

The policy domain can also play a vital role in promoting stakeholder collaborations. A recent study by Odoyi and Riekkinen (2022) explored housing policy discussion using qualitative content to promote affordable housing for low- and middle-income earners, which finds that land, research and development, housing schemes, and government are important to providing affordable housing. Institutional factors that constraint the collaborative approach among stakeholders for housing development include duplication and confusion arising from parallel policies/legislation, lack of inter-stakeholder communication networks, slow administrative processes in certifying and policymaking, lack of a comprehensive code /policy package to guide action on sustainability (Yang and Yang, 2015). If mutual gains are to be achieved, there needs to be some alignment among the partners because mismatched partners can strain collaboration (Berger et al., 2004). A focus on mission and community can provide necessary alignment, anticipating problems of fit and structure to avoid misallocation of costs/benefits or mismatched partnerships (Madden, 2011).

Barriers to collaboration must be addressed to minimize uncertainty and build essential information to deliver across all stakeholders (Cheung and Rowlinson, 2011) and positively impact decision-making toward more efficient and effective outcomes (Miller and Buys, 2013). Yang andYang (2015) revealed that the problems of key housing stakeholders, particularly those designing, developing, and marketing sustainable housing products, were not studied systematically. This fits well with the case of Pakistan since the country is facing the provision of affordable housing for low-income groups. The situation is alarming; around 47 per cent of urban households are estimated to live in squatters. These overcrowded informal settlements lack basic infrastructure like schools, sanitation, and health services, contributing to poor social and economic outcomes (Uppal, 2021; Malik et al., 2020). Housing prices have increased over time; this has been reflected in all the data sets under observation. There is drastic inequity in the provision of housing, resulting in too much housing for high-income and too little for low-income groups. This is because the country has observed rapid growth in population and urbanization that has badly affected almost every activity of city life (Ahmed et al., 2021). Recent housing efforts from the government sector, like the Naya Pakistan Housing Project (NPHP), need to do more to ensure that government land and revenue are utilized for the benefit of those who need it the most (Farrukh, 2022).

The present study reflects on the two-fold research gap: stakeholder and low-income housing studies concerning Pakistan. Previously, stakeholder studies in the Pakistani context have focused on stakeholder communication for the software industry, housing design and household practices brownfield redevelopment environmental impact assessment (Nadeem and Fischer, 2011; Bott, 2018); risk management practices in the construction industry (Choudhry and Iqbal, 2013); and housing reconstruction post-conflict (Zada, 2019). Regarding the low-income housing domain in Pakistan, existing literature has not investigated collaboration barriers restricting the provision of low-income housing. Past and recent studies have explored the different perspectives related to low-income housing. For instance, housing finance models from investor innovators like Reall (Jones and Stead, 2020), urban sprawl and colonization (Javed and Riaz, 2020), housing inequalities among ethnolinguistic groups (Munir et al., 2022), understanding the public housing institutions with overlapping jurisdictions and roles (Malik et al., 2020), the impact of foreign capital inflow on the housing market (Ahmed et al., 2021), financialization and real estate in the Global South (Akhtar and Rashid, 2021), and determinants of housing prices (Azam Khan et al., 2022). It establishes a key research gap to conduct the rigorous analytical study of barriers to stakeholder collaborations to address the prevalent issue of inadequate low-income housing delivery mechanisms in most developing countries, particularly Pakistan. The key stakeholders in establishing linkages of allied industries with the housing sector can play a vital role in housing provision for low-income groups. Since stakeholder-oriented studies could have multi-dimensional scopes, this study explicitly focuses on exploring stakeholders’ experiences within the low-income housing sector’s state, market, and civil society categories. Research shows that stakeholders who engage as facilitators, invest in building trust and commitment, and promote a sense of shared responsibility can help their networks overcome these barriers and collaborate more effectively (Mosley, 2021). By studying the low-income housing context in Pakistan concerning collaboration barriers, research can reveal the operational loopholes within current government-set conditions and private market agendas to offer the best possible grounds for solutions to policymakers.

Methodology

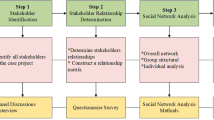

The insufficiency of literature, particularly on the Pakistani low-income housing sector, as indicated above, can be well achieved in the present research by exploring the experiences of housing providers represented by key stakeholders working in different categories, i.e., state (government authorities), market (Developers), and civil society (NGOs). The selection of stakeholders was guided for the present study from previous studies like Bondinuba et al. (2016), such as housing providers like microfinance bodies, end users, government bodies (banks, ministries, and local bodies), and supporting institutions (academia, research centres). Exploration of theoretically loaded parameters with ideology, structure, and experience of stakeholders to the proliferation of the concept of low-income housing need to be measured qualitatively (Moore, 2005; Moore and Koontz, 2003). Hence, the case study approach helped understand the low-income housing arena by exploring the stakeholder experiences and perspectives through in-depth interviews.

Lahore, the capital and the most populous metropolitan city of the largest province of Punjab, Pakistan, has been chosen as the case study area. The selection of Lahore city is because the largest public project in the low-income housing sector, i.e., the Ashiana Housing Project (AHP), exist in the city. Purposive sampling directed the first data collection phase, resulting in twelve in-depth interviews. In the second data collection phase, the online interviews were conducted from another city, i.e., Islamabad, where federal housing authorities exist. Eighteen interviews were conducted for 1 h or more. The extensive study of developers, public housing authorities, social enterprises, consultants, and financial institutions working in the low-income housing sector provided the underlying barriers. The housing providers (State, market, and civil society) interviewed at the local level and provincial and federal (national) authorities are summarized in Table 2. All such stakeholders have been playing major roles in sustaining the provision of low-income housing in Punjab, Pakistan.

The theme of the primary research question is to explore barriers to stakeholder collaborations, asking: Why can stakeholders not collaborate within current institutional arrangements for low-income housing provision? This question aims to identify key obstacles to federal, provincial, and local-level partnerships that would reveal limited collaborative activities and developer experiences for facilitating the low-income housing sector. The barriers regarding land acquisition, infrastructure development, designing and planning of housing projects, limited mortgage and housing finance, and inadequate policy frameworks within the low-income housing sector were addressed. This question is sensitive to uncovering the truth of the state and market’s institutional capacities. According to each indicated barrier, the sub-questions turned into individual nature to meet the objective of knowing constraints that obstruct collaboration and contribute to the isolated engagement/ coordination of concerned stakeholders. In this study, adopting the researcher’s reflexivity as a validity technique to control bias, the researcher kept and employed a separate journal of abstract interpretations before and after the data collection and analysis. It proved that personal speculative arguments do not support data analysis and discussion. The data was analysed, and three stages of coding (initial, focused, and theoretical) were processed in NVivo 12.

Findings

Collaboration barriers in the context of low-income housing were found to be involved with the government sector, policy, and institutions. Within this study, the constrained capacity of the government sector and poor engagement networks were mainly discussed by the research participants. Overarching categories under this theme are being discussed individually, with distinct properties under each category.

Institutional complexity

Barriers within institutional arrangements and engagement patterns deviate stakeholder attitudes towards collaboration for low-income housing provision. Almost all participants agreed that institutional arrangements were crucial to satisfy, compromising the effective provision of low-income housing in Pakistan. Each property under this category is listed along with scopes in Table 3.

Procedural delays

Procedural delays were associated with state departments and the exchange of information with market stakeholders for low-income housing development. Poor maintenance of land records appeared as an essential source of delaying the application process for developers. An interviewee (consultant 2, 2019) mentioned that “we requested every authorized person to provide relaxation to get our project land title, which got delayed due to human error on the masterplan”. Another reason behind the land approval delay is the status of land pockets. Clearing the parcels of land existing within the housing project, as pockets are already sold, is a hassle (Interview, ABAD Member, 2020). This issue was also highlighted by PHATA officials that “within a big chunk of land, such issues are common, where some 2 MarlasFootnote 1 belong to someone else and other pockets to someone else (Interview, PHATA official 1 & 2, 2019).

The flow of information among state departments within federal, provincial, and local authorities is cumbersome. It was observed as a massive issue within the government-appointed teams, where departments are working superficially through the circulation of files, and proper work is being compromised (Interview, consultant 2, 2019). Each task in the government office takes around two weeks; ideally, if there is an objection/note on the project file, it further delays the execution of the project following the same procedure (Interview, Provincial HTF member, 2020). The bureaucratic working system further delays the application process within current institutional arrangements. Another government official regarding provincial authorities shared the same experience: “Things are working very slowly; a summary of such problems was prepared and shared with relevant authorities, currently waiting for the actual outcomes (Interview, PHATA official-1, 2019). Financial assistance to Akhuwat was delayed for one year for the Naya Pakistan Housing Program (NPHP) by the ruling government of PTI in 2019. It happened due to the lack of project planning and delaying procedures for approval applications regarding land and finance (Interview, Akhuwat official, 2020). The same issues also delayed the infrastructure for the NPHP low-income housing projects (Interview, PHATA Official 2, 2019).

Weak institutions

State authorities must be examined through the performance of public service delivery to the community, and if the performance is weak, institutions must be held responsible. There is a need to look at the genesis of the housing shortage, and for this, housing departments at the city level must give data about houses being constructed every year (Interview, ABAD Member, 2020). While speaking about the institutional performance at the local level, LDA projects are in the same status even after ten years with vacant land plots and no construction activity (Interview, BOP official, 2020). The HBFC’s performance was also inferior, being the only financial institution in Pakistan. HBFC kept running unattentively by the GOP; it is unfortunate to see that in Pakistan, institutions are weak, and people are strong (Interview, HBFC official, 2019).

The local government departments are directed by bureaucrats who chair the planning committees at the city level. Within planning committee meetings at the local level, bureaucrats usually make irrelevant objections without having technical knowledge of urban development projects (Interview, consultant 2, 2019). Orthodox approaches to data maintenance contribute to weak institutional performance. The rent-seeking attitude of land record officials (patwariFootnote 2 culture) and lack of digitalization impact land matters, including site demarcation (Interview, PHATA Official 2, 2019). Technical understanding of stakeholders about the current constitutional framework also configures the execution of housing matters. Many state stakeholders, including the judiciary, lack understanding of the housing business & real estate sector and its conflict with legal frameworks like foreclosure laws (Interview, LDA Official, 2019).

Complex legislative matters

Pledging land documents is an integral part of the housing mortgage agreement. For this reason, officials go to civil court (kacheriFootnote 3) to get land record documents for the mortgage, which is quite a challenging job (Interview, HBFC official, 2019). PTI government promised tax relaxations for developers to speed up the NPHP planning and execution. However, the approval process was constrained due to the country’s economic instability. International Monetary Fund-IMF has limited tax relief that the government promised, restricting the Ministry of Finance to facilitate low-income housing provision (Interview, ABAD Official, 2019). The cabinet is delaying the approval of housing legislation such as property laws, foreclosure laws, and Public-private partnership (PPP) acts. In 2018, the State Bank of Pakistan-SBP presented the foreclosure law in the assembly, and it is still in the approval process by the Cabinet (Interview, BOP Official, 2020; PHATA Official 1, 2019). The Real Estate Regulatory Authority (RERA) was proposed to regulate the real estate sector with more legislative and regulatory powers. Due to delayed responses, RERA was given the shape of the ordinance by the Cabinet, with an effective duration of three months unless it becomes an Act following the Parliament procedure (Interview, HTF-Federal official, 2020).

Institutional duplication

The presence of a wide range of housing organizations has added more confusion among housing stakeholders in each category (state, market, and civil society). NPHDA-Naya Pakistan Housing Development Authority, as a new emerging government body at the federal level, has not defined a clear delivery mechanism (Interview, consultant 1, 2019). Duplication in roles among these diverse housing organizations has created difficulties for developers predominantly. In Lahore, the universal approval procedure for housing projects does not exist yet due to the duplication of public departments and authorities (Interview, HTF-Federal official, 2020). In this context, one of the interviewees stated, “I would not call it a multiplicity of organizations but overlapping jurisdictions fabricating mumble and a jumble of laws and regulations in the housing sector” (Interview, LDA official, 2019). There is another anomaly for private developers since LDA is acting as both a regulator and a developer in the case of Lahore. There is no accountability for LDA-initiated projects. The private developer must obtain over 10 NOCs (no objection certificates) to verify and support its planning permission application for a new housing project (Interview, consultant 2, 2019). This is a complete violation of competition laws that a private developer needs several NOCs to advertise a construction project, unlike LDA (Interview, ABAD Official, 2019).

Constrained capacity of the government sector

The constrained capacity of the government sector is associated with the limited role of state stakeholders within the context of low-income housing provision. This collaboration barrier among housing stakeholders reveals the incompetency within the state departments and suggests institutional reforms. The table illustrates the emerged properties for this category (Table 4).

Accountability and transparency

The recent involvement of the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) in the housing sector is not welcomed by market stakeholders, especially ABAD. Interviewees reflected that NAB doesn’t understand the complexities associated with property and real estate business. Without expertize and a poor understanding of cooperative housing laws and building by-laws, NAB has previously audited housing projects (Interview, consultant 2, 2019). For transparency to be achieved in the housing sector, it is essential to identify the corruption activities in the property business. The matter was referred to the Ashiana Housing Project (AHP) corruption case, a Public-Private Partnership project of PLDC. Biased awarding of the project to the incompetent bidder while tendering the project to the private sector triggered NAB’s investigation at the prequalification stage, as financial shares of Joint Venture-JV were not disclosed (Interview, PLDC official 2, 2019). For government-owned projects, developers must be guaranteed by government organizations like NABPTO and PPRA (Public Procurement Regulatory Authority) to avoid legislation issues. Private developers fear working on state-owned lands as the current NAB reference of AHP is restricting them from investing in public low-income housing projects (Interview, AMC official, 2020).

There has been an identity clash between former and present governments establishing political victimization towards public service projects, including low-income housing provision. Political leaders have created delays for land approvals on behalf of their conflicts (Interview, LDA official, 2019). Previous government of Pakistan Muslim League Noon (PMLN) didn’t support PHATA in the past because of its association with another political party, i.e., PML-Q (Pakistan Muslim League Qaaf), establishing PLDC to replace PHATA in delivering public housing projects (Interview, HTF-Provincial official, 2020).

Poor coordination patterns

The absence of an integrated approach among state departments directs disturbed coordination among housing stakeholders. Poor federal-provincial linkages among housing departments caused a lack of coordination among NPHDA members, which made valuable members leave the HTF teams for public housing projects (Interview, consultant 1, 2019). The federal government has initiated an online survey to register for NPHP low-income housing schemes; however, information has not been floated yet to the provincial and local bodies (Interview, HTF-Provincial official, 2020). In Punjab, PHATA deals with NPHP, and PHATA officials have no clue about the state department working in other three provinces, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Baluchistan, for NPHP projects (Interview, PHATA official 2, 2019). PHATA, as a mainstream provincial housing body, is also unaware of public policy seminars. PHATA lacks information about urban policy talks and seminars and how these contribute to the cause of low-income housing provision (Interview, PHATA official 2, 2019). Similar building bylaws are not followed in different cities across Punjab. This has been observed as a critical issue leading to poor coordination among different institutions for housing projects. The draft of standardized LDA building by-laws has not yet been approved, even after nine months (Interview, HBFC official, 2019). Low consistency of interaction among stakeholders has led to limited collaboration since HBFC didn’t contact the Akhuwat Foundation for any low-income housing project (Interview, Akhuwat official, 2020). Admittedly, if we are looking for coherence between the public and private sectors for housing projects, we don’t have any examples (Interview, PHATA official 2, 2019).

Limited fiscal funds and mortgage facility

Restricted mortgage provision is the biggest issue faced by low-income groups, as beneficiaries cannot afford their housing units at affordable rates. Many interviewees mentioned it as the main barrier to effectively providing low-income housing. The ratio of mortgage finance in the world is 80–90%, while in developing countries, even in India, the mortgage ratio is around 6−7%; however, this ratio drops to less than 1% in Pakistan (Interview, ABAD official, 2020). This perspective may be related to the unwillingness of many banks to lend money to low-income groups. Banks consider providing mortgages to low- and middle-income groups risky due to their inability to pay the loan installment (Interview, HBFC official, 2019). In this regard, another issue is the undocumented salary sources for low-income groups. People are reluctant to get documented in the official salary brackets by maintaining bank statements to avoid tax payments; hence, risk assessment for such people becomes difficult for the banking sector (Interview, LDA official, 2019).

Other problems were also counted for mortgage facility. The interest rate is very high, and the mortgage repayment time is short (Interview, independent consultant, 2019; HBFC official, 2019). Lack of fiscal funds delays the infrastructure development in low-income housing projects, impacting the project execution negatively (Interview, PHATA official 2, 2019). In the context of NPHP, financial constraints were faced by the government authorities for the execution of our prepared projects in five or six cities of Punjab (Interview, HTF-Provincial official, 2020).

Shortage of human capital

Human capital is the sole driver for organizational competency and satisfactory service delivery in the urban development sector. Capacity building is a major component in the efficiency of government departments within the housing sector (Interview, PHATA official 1, 2019). Previously, intellectual human resources have not been incorporated properly within the housing sector. An irregular hiring system with little consideration given to relevant education and experience has spoiled the performance of government housing departments (Interview, MHW official, 2020). Hiring such poor professionals has adversely affected the working capacity of state housing authorities (Interview, PHATA official 2, 2019). The government has not focused on town planners, architects, and housing experts to deliver low-income housing projects successfully. Architects and town planners were not hired for a long time in PHATA to execute plans from the planning phase (Interview, PHATA official 1, 2019). In the case of PLDC (2010–2017), regular recruitments were not made for the company’s CEO. The Chief Minister of Punjab (PMLN) appointed bureaucrats with additional charges. Hence, they did not perform well due to double job duties and poor focus on delivering the project (Interview, PLDC official 2, 2020). In every government institution, the workload on a single person is high, reducing the departmental efficiency of the public sector and ruining the service delivery to cities (Interview, consultant 1, 2019).

Poor efficiency

A lot of challenges come with massive housing provisions for low-income groups. Effective use of government money to execute housing projects is one of those challenges. So far, the Government of Punjab (GoPb) has delivered very few projects, and beneficiaries are not interested in public housing projects, considering AHP as the recent example (Interview, consultant 2, 2019). The situation is even worse at the federal level than at the provincial level. Previously, only 5500 housing units were delivered from 1999 to 2016 in the context of public housing projects (Interview, MHW official, 2019). In 2015, federal authorities were mandated to provide houses and apartments in different areas with a target of 7000 housing units; however, this is still in process (Interview, MHW official, 2019).

At the provincial level, within the state housing departments, PHATA remained inactive for a decade. If PHATA was active as an executing body, there was no need to introduce PLDC; instead, it delayed the execution of low-income housing projects (Interview, PLDC official 1, 2019). Execution of quality housing projects is the key to achieving the wider urban development goals. The Defence Housing Authority (DHA) is famous for its brand value by delivering quality infrastructure, facilities, and governance within the private sector. In contrast, as a developer in the public domain, LDA has not delivered at the same pace (Interview, BOP official, 2020). The service quality of DHA is better, while LDA has negative brand value as the delivery of projects has extended over twenty years (Interview, ABAD official, 2019). Flawed master planning caused extreme practical shortcomings. Master plans were not updated under the ground realities of the changing urban landscape. In the context of Safia Homes (Faisalabad), the master plan contradicted the statements of local authority officials labeling the project land status as agricultural; at the same time, a housing society was already built on the ground (Interview, AMC official, 2020).

Incompetent state legislation

Incompetent state legislation restricts local authorities from implementing and maintaining law and order within the housing sector. Emerging properties for this category are listed in the following Table 5.

Unregulated real estate sector

Weak foreclosure laws negatively impact the real estate culture and encourage the mafia to regulate the urban development sector. Without strong foreclosure laws, banks are reluctant to enter the housing sector. If a person becomes a house mortgage defaulter, then court stay orders facilitate the person, leaving banks insecure (Interview, HTF-provincial official, 2020). The real estate sector cannot be regulated well due to property transactions for vacant land plots. In Lahore, 60–75% of Bahria Town is, on average, vacant, and investment for such land plots has escalated the property prices (Interview, BOP official, 2020). At the city level, 40−45% of plots in Lahore are vacant land plots. Unfortunately, LDA has not devised a mechanism to determine the property transaction process’s 4Ws (What, When, Who, and Where) (Interview, LDA official, 2019).

The powerplay of some leading developers and business tycoons merely dominates the real estate sector. Private developers like DHA & Bahria Town serve only high-income groups (Interview, Urban Unit official, 2019). It has caused the limited availability of housing units to low-income groups. In Lahore, 20% of rich households occupy 56% of the land, while 20% of poor households live on 6% (Interview, Urban Unit official, 2019). The poor regulation of the real estate sector has badly affected housing project delivery. The rules and laws for documenting the property transaction processes are missing at the local level, delaying the delivery of housing units over ten years on average (Interview, HTF-Federal official, 2020).

Corruption in government authorities

The bribe activities are considered routine with land record officials in housing state departments like the Board of Revenue and LDA in Punjab. Rent-seeking behavior of land record officials is common by demanding bribes from project applicants to get the process for land matters timely (Interview, PHATA official 2, 2019). Bribe culture being practiced in government departments further leads to land ownership conflicts. Land record officials driven by vested interests often change the land records, which becomes problematic for developers while processing the planning permission application from the relevant development authorities (Interview, LDA official, 2019). Inter-departmental corruption also delays the approval of housing projects. LDA has not delivered projects like LDA City, and open plots were not allotted to applicants for around 12 years for LDA Avenue one (Interview, LDA official, 2019).

Bureaucratic lobbying among government officers is creating hurdles for the approval process of housing legislation. The cabinet includes delegates from the different ministries. If an objection is made from one minister, the whole application request for the housing project gets stuck into extensive documentation (Interview, ABAD official, 2019). Developers are facing difficulties from such a bureaucratic environment of government departments. The bureaucracy acts as a stumbling block and is not interested in moving the support for private developers willing to work for public low-income housing projects (Interview, AMC official, 2020).

Poor enforcement

Many participants experienced weak policy implementation deteriorating state authorities’ working capacity. The impact of policy frameworks on the housing sector can’t be measured due to lack of enforcement (Interview, PHATA official 1, 2019). Due to weak policy enforcement previously, stakeholders are not optimistic about ongoing projects like NPHP. The housing sector has not flourished despite the presence of policy frameworks (Interview, PLDC official 1, 2019). Many policy and planning talks have already been done; the real task is implementing the policies and regulations (Interview, LDA official, 2019). Proposing rules and frameworks is theoretical, while policy implementation is part of the execution process of housing projects. Regarding the policy gaps and their implementation, there is a need to bring the framework down to the provincial and local levels to implement policies from the federal level (Interview, AMC official, 2020).

Absence of political will

This barrier emerged as an important part of the experiences and perceptions of the study participants. All the stakeholders, including the state stakeholders, felt that poor political will is the leading cause of the limited provision of low-income housing. The following table illustrates the emerged properties for this category (Table 6).

Vested interests

Vested interests of political leadership have disturbed the provision of low-income housing in Punjab and the country. Personal and professional motives primarily drive most of the stakeholders involved in the housing development sector. Stakeholders, including developers and consultants, get involved in the housing project consultations on behalf of their vested interests (Interview, consultant 2, 2019). Many members of HTF were motivated by their wish to enter politics through the NPHP platform (Interview, HBFC Official, 2019). One of the interviewees shared plans that I belong to a political family and would like to participate in the upcoming elections (Interview, HTF-Provincial official, 2020).

The personal involvement of political leaders with vested interests disturbs the volunteer actions of the stakeholders with dedicated causes. A steering committee was formulated to plan the AHP execution involving land acquisition strategies and infrastructure development proposals. After six months, dedicated members left the committee due to political intervention from Members of the Provincial Assembly (MPAs) in Punjab (Interview, HBFC official, 2019). The wish for political victory mainly drives politicians to put interest in low-income housing projects. AHP was delayed by five years since the favor was not returned to a developer who lent the financial aid to GoPb for project initiation (Interview, PLDC official 2, 2019). Such huge, vested interests trickle down to the level of bureaucrats and government officials of housing authorities. PMLN made political mileage by securing a vote bank in Punjab during the general elections in 2013 by initiating AHP under PLDC (Interview, HBFC official, 2019).

Recently, NPHP has also been perceived as a political motive by the PTI government, like the way PMLN did for the AHP previously (Interview, ABAD official, 2019). Furthermore, to become more prominent and visible, most public projects are often associated with the Vision of the Prime Minister or the Chief Minister. In the early 1990s, Muhammad Nawaz Shareef was the Prime Minister of Pakistan, and he introduced the project of 500,000 housing units for low-income groups under the Prime Minister Housing Authority (Interview, MHW official, 2019). In addition to vested interests, bad intentions also contributed to gaps in the timely delivery of low-income housing. People don’t obey the law because of bad intentions, which can’t be labeled bad governance (Interview, LDA Official, 2019).

Constant shift in higher management

The constant shift in top management for government departments like PHATA and PLDC confirms the political intervention in the institutional working of the housing sector. The political leadership kept changing housing secretaries, disturbing the consistency of work for NPHP in the PTI (Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf) government (Interview, HBFC Official, 2019). Continuous changes in PLDC top management every four or six months delayed the AHP project extensively (Interview, PLDC official 2, 2019; Fig. 1). Another issue within the appointment system was placing people from bureaucracy with an additional charge as it diverted the dedicated efforts for efficient project delivery. This shuffle in top administration affected a PLDC greatly when bureaucrats were given additional charge of CEO besides their primary job in another government sector. (Interview, PLDC official 2, 2019; Interview, Urban unit official, 2019).

The PTI government’s project delivery patterns are disturbed due to constant shuffling in Punjab Building By-laws approval. PHATA forwarded the housing Bylaws to the housing secretary; three secretaries have changed in eight months (Interview, HTF-Provincial official, 2020). Regarding PHATA’s performance, the constant change of the Director General is troubling the policy drafts and project proposals for low-income housing since the individual priorities don’t match different management systems (Interview, Academic, 2020).

Poor trust in government

The limited vision of government authorities is keeping the slow pace of housing provision. Provincial and local housing departments have poor knowledge of project execution and are confused about delivery strategies (Interview, consultant 1& 2, 2019). High-ranked officials like ministers and secretaries must have the road map for implementing the policies being initiated for the housing sector. The housing minister in Punjab could not approve the affordable housing rules from Cabinet due to limited vision and approach to action (Interview, ABAD Official, 2019). The response to foreign investors also matters in delaying the delivery of massive housing projects like NPHP. Delayed responses from concerned authorities made the investor lose interest in the project, leading to a lack of confidence in government institutions (Interview, Independent Consultant 2, 2019). The current government does not back the people working with the previous setup. Current government representatives are not willing to take up the AHP as the reference for planning future low-income housing projects (Interview, PLDC Official 2, 2019). In the early days of NPHP initiation, volunteers were active in HTF meetings, but this dynamic response declined with time. The low credibility and trust in government authorities caused the stakeholders to move out of volunteering for the cause of low-income housing provision (Interview, Academic, 2020).

Poor environment for collaboration

The poor environment for collaboration was identified as a major reason for ineffective stakeholder engagements constraining the effective provision of low-income housing. Overarching properties within this category are listed in the following Table 7.

Limited culture of collaboration

The mechanism for approaching and selecting the stakeholders for low-income housing provision consultations was observed to follow a biased approach. NPHP stakeholders were selected either randomly or according to the personal choice of the higher authorities (Interview, Independent Consultant 1, 2019). It reflects the unpromising attitude of government policies toward documenting and sharing the minutes of meetings with all stakeholders and the public (Interview, Academic, 2020). Many meetings are probably a waste of time since it is hard to see the foreseen productive outcomes (Interview, BOP official, 2020). The culture of collaboration has not been developed yet, and unsuccessful engagement of the private sector has limited the low-income housing provision. There is no concept of institutionalized collaboration, and it can only be achieved through engaging more potential stakeholders in the low-income housing sector (Interview, PLDC official 1, 2019).

Poor acknowledgement of technical expertize

A poor environment for collaboration is due to the inadequate acknowledgement of intellectual resources for low-income housing development. Quality housing is hard to achieve without the involvement of experienced housing professionals (Interview, Independent Consultant 2, 2019). Fund allocations & cost-cutting behavior are standard norms in public projects for housing development. Consultancy services for the public sector are not being paid yet, even after the execution of the projects. One more basic flaw lies in the provincial procurement rules: the consultancy fee is not more than 2% in public projects while preparing Project Costing: PC-I (Interview, Independent Consultant 1, 2019). The allocated design fee (2% of the total project cost) cannot accommodate the resident supervision comprising resident engineers, architectural engineers, and quantity surveyors (Interview, Independent Consultant 1, 2019).

The trend of hiring international consultants for government projects negatively impacts local consultants and designers who better understand ground issues within the low-income housing sector. It leaves an impression that resident consultants and developers cannot deliver, and foreigners can provide solutions for local housing issues, which is an absurd expectation (Interview, ABAD Official, 2019). Professionals are reluctant to join the financial institutions of the government sector. Experts are there for housing finance. However, they demand an enabling environment to work properly; unfortunately, it doesn’t exist in government offices (Interview, BOP Official, 2020).

Poor sense of civic responsibility

The absence of volunteer organizations prevents practitioners and students from participating in civic responsibility activities. Planning Aid for London is a voluntary organization that provides free planning advice to people. Unfortunately, Pakistan has no such platform (Interview, Independent Consultant 1, 2019). Another reason is the elite capture that restricts the private developers from working for the cause of low-income housing. Urban supremacy in Punjab revolves around ‘Power, Profit, and Plan, representing DHA as Power, Bahria Town’s as Profit, and Plan as master planning, as these three factors have shaped the urban form of Lahore (Interview, Urban Unit Official, 2019). Real estate is a property transaction sector, and property owners are not showing efforts to serve low-income groups with adequate housing at affordable rates. The lack of a proactive approach from the real estate sector instills unwillingness among developers to perform a promising role in the low-income housing sector (Interview, Academic, 2020).

Policy and practice gaps

The housing sector in Pakistan suffers from policy and practice gaps not only on the federal level but also at the provincial and local levels. This category was majorly defined by interviewees about the intention and direction for policymaking and the inadequacy of the existing policy framework. The emerging properties under this category and the associated scopes are mentioned in the following Table 8.

Intention and direction for policy

In developing countries like Pakistan, housing policy is not being drafted extensively, addressing all the concerns. Unfortunately, the existing housing policy does not address the issues of housing backlog in detail (Interview, HTF-provincial official, 2019). Policy frameworks don’t provide essential housing information such as housing shortage, housing demand analysis, and target income groups (Interview, MHW official, 2019). Meaningful intentions of state stakeholders for the extensive policymaking have not been observed. It has caused a lack of clarity while executing the housing projects. A housing policy must include important aspects about budget, location, and building materials for affordable housing (Interview, PHATA Official 2, 2019). Expediting the approval as well as the execution process of low-income housing projects are policy-related matters (Interview, LDA official, 2019). In government departments, the policy-making process is mainly led by bureaucrats. Bureaucracy cannot understand urban governance issues without urban planning expertize (Interview, Urban Unit official, 2019).

After the initiation of NPHP, the PTI government couldn’t pledge policymaking for the low-income housing sector. Although the MHW is supportive, no work has yet been started for extensive policymaking to facilitate low-income housing provision.” (Interview, HTC-provincial official, 2019). After the 18th constitutional amendment, housing became a provincial subject; however, the federal housing policy is still being implemented in provinces, which directs policymaking as the federal domain of action (Interview, LDA official, 2019). Apart from this federal-provincial interplay of housing policies, it is also essential to investigate the need for rural and urban low-income housing policies. There is no provision for any section regarding low-income housing in the current housing policy; it should be treated as a separate policy draft (Interview, PHATA official 2, 2019). However, others believe one housing policy should include solutions for low-income housing issues (Interview, Urban Unit official, 2019).

Inadequate policy frameworks

The inadequacy of policy frameworks is majorly related to inaccurate attempts to target the beneficiaries of public low-income housing projects. Housing authorities mostly facilitate middle-income groups, which are not the target of low-income housing projects (Interview, Academic, 2020). There is no section about finance tools within the National Housing Policy, NHP (2001), such as micro-financing and incremental housing solutions for low-income groups. Chile and Singapore tackled the challenges of housing backlogs by adding dedicated financial solutions to the policy frameworks (Interview, Academic, 2020). Collaborative housing projects are absent due to inadequate policy frameworks (Interview, PLDC Official 1, 2019). Building bylaws and land regulations are essential components of housing policy that have been neglected in the past. Local authorities in different cities have separate building bylaws displaying different public regimes under PHATA, making policy enforcement difficult (Interview, AMC Official, 2020).

Weak housing finance policy

Housing finance is a federal subject regulated by SBP; however, its policies have not been implemented widely. SBP keeps updating the housing finance policy, including relaxing the terms to enhance developer activity in the low-income housing sector. However, little implementation was observed (Interview, HBFC official, 2019). As a major market stakeholder, ABAD labeled the housing finance sector weak and uncertain. The revised policy by SBP has not yet been implemented, so its impact on low-income housing development can’t be decided (Interview, ABAD official, 2019). The current trends of price escalation and inflation in the property sector demand that housing finance policies be revised. Even the policies released in 2018 have already become outdated due to escalated dollar rates (PKR 160 to PKR 220) as of today (Interview, ABAD official, 2019). There is a constant increase in the construction cost of housing units, but the time allotted to pay the housing loan through a mortgage agreement is insufficient. In DHA, the land price has increased by 60%, while the construction costs increased to 75% within a year. However, less time is allowed from the banks in the mortgage payment (Interview, BOP official, 2020).

Ways forward

Institutionalized collaboration was well explored under this category with concepts of organizational revitalization. The concerns were more descriptive in the suggestions of organizational restructuring, while more participants were found in responses for collaborative alliances. The properties of this category and associated scopes are presented in Table 9.

Revising organizational hierarchy

The diversity of housing government departments was highlighted as a serious barrier to housing collaborations, causing poor coordination and inefficiency. The interviewees from the state departments suggested that public departments should revise their organizational structure and hierarchy. The foremost obligation is to merge the existing housing authorities at the provincial level into NPHDA, which will bring more clarity to the rules (Interview, PHATA official 2, 2019). According to this suggestion, a single implementation direction would navigate the provincial departments to follow low-income housing programs in a more focused way. Organizational revitalization demands significant steps in bringing various departments and authorities under one umbrella. There should be only one legislative body at the provincial level of Punjab, including all the legal bodies for housing development, and a sub-legislation body for monitoring local bodies (Interview, AMC official, 2020). At the city level, the ideal condition is to have one parent department under which all departments should work; for instance, in the case of Lahore, it is LDA (Interview, PHATA official 1, 2019).

Decentralization of power at the local level could be a potential approach for achieving the desired organizational hierarchy. Governance is more efficient at the local level, so LDA and PHATA should work in their designated domain of action; furthermore, the supervisory role must be defined for NPHP execution to improve the low-income housing shortage. (Interview, PLDC official 1, 2019). The replication of federal authority must ensure better coordination and coherence among the public departments at all government tiers. The supervisory role must be assigned to NPHDA, and it should take targets from established federal authorities like MHW, FGEHA and PHA to work together for the vision of NPHP (Interview, PLDC official 2, 2019). Provincial replication of NPHDA must be developed to better coordinate with PHATA and PLDC for low-income housing provision (Interview, HTF-Federal official, 2020).

Collaborative alliances with private sector

All research participants suggested government-initiated collaborations with the private sector to provide low-income housing effectively. For this reason, the tendering process of public housing projects must be accessible to all stakeholders. Government authorities must keep the tendering mechanism open by taking offers from all active private developers and transferring these offers for the project execution by transparent payment method (Interview, consultant 2, 2019). Social enterprises like AMC and Akhuwat can come under mutual funds by offering built low-income housing units through joint ventures and collaborative alliances with the government sector (Interview, PHATA official 2, 2019). AMC can collaborate with NPHP to facilitate low-income housing development.” (Interview, HTF-Federal official, 2020). A cross-subsidy model must be replicated in the government sector by enabling private developers to profit from housing projects. Such a government-enabled environment would convince developers to offer housing units to low-income groups as cross-subsidization (Interview, LDA official, 2019). Public-private partnerships must be encouraged in the housing sector by formulating a competent committee to communicate negotiations for PPP initiatives of low-income housing projects within the government departments (Interview, PLDC official 1, 2019).

Stakeholder engagement for policy consultation was missing to collaborate for low-income housing provision. State departments must take consultants to improve research and technical expertize (Interview, PHATA official 1, 2019). Authorities should pay consultants properly for the authenticity of project design, short planning assignments, and feasibility studies (Interview, consultant 1, 2019). The participatory approach is important to streamline resource-wise stakeholder engagements in the low-housing sector. Academia, civil society, practitioners, private developers, professionals, and citizens must be consulted during the decision-making processes of low-income housing programs to ensure the active inclusion of all major stakeholders (Interview, Urban Unit official, 2019).

Transforming attitude for civic responsibility

Institutionalized collaboration is not possible without inducing the spirit of civic responsibility. Understanding market segmentation is essential to collaborative project design while planning low-income housing projects. Knowledge of market segments can help developers plan for community houses as a cross-subsidy housing model easily accessible to low-income beneficiaries (Interview, BOP official, 2020). Employing the concept of ‘build and sell’ for already ongoing projects is essential compared to launching new projects like NPHP in the context of low-income housing. The timely property transactions of low-income housing units benefit developers and beneficiaries, minimizing the chance of abandonment (Interview, BOP official, 2020). A proactive approach at the top management level within the organization can induce civic responsibility. Top managers in housing departments must understand institutional arrangements and be familiar with the project delivery mechanism through positive lobbying (Interview, Urban Unit official, 2019).

Discussions and conclusion

This study has provided an understanding of the factors responsible for collaboration barriers among housing stakeholders in urban Pakistan to provide low-income housing. The data sources from stakeholder interviews of different categories (State, Market, and civil society) revealed the critical barriers to collaborations for low-income housing planning. Analysis of the present study finds six major insights. First, institutional complexity within the low-income housing sector involves procedural delays, poor organizational performance, lengthy legislative processes, and institutional duplication (Table 3). Institutional factors like duplication within parallel policies/legislation by provincial bodies and biased stakeholder consultation supported the findings by Yang and Yang (2015). Second, the constrained capacity of the government sector reflects the issues of accountability, mortgage, coordination patterns, poor efficiency, and capacity building of human capital (Table 5). The involvement of government officials in multiple domains affecting the working capacity of the government sector resonated well with Meehan and Bryde (2015) and Madden (2011). Third, incompetent state legislation showcases the interconnections with corruption in government authorities, poor policy enforcement, and the real estate sector (Table 6). Due to incompetent state legislation, the governance of low-income housing projects is difficult due to unlawful property transactions within low-income housing schemes. This domain of findings was also highlighted well in previous studies like Mehmood (2016) and Malik et al. (2020), Kaleem and Ahmed (2010), Gandhi (2012), and Olotuah (2009).

Fourth, the absence of political will reveals the unfortunate parts associated with the profit motives of political leaders, poor trust in government operations, and execution delays of housing projects due to stability issues of higher management (Table 7). The vested interests and profit motives also led to non-stability in the administrative position of PLDC (Fig. 1). Studies including Madden (2011), Siddiqui (2015), and Aazim (2017) have also highlighted these concerns. Literature (Lowe and Oreszczyn, 2008; Li et al., 2018; Sourani and Sohail, 2011); Muazu and Oktay, 2011 shows the environment for collaboration as a critical aspect of delivering housing projects. The emerging theme, i.e., a poor environment for collaboration, was acknowledged as the fifth main barrier, which involves poor acknowledgement of technical expertize, the limited culture of collaboration, and civic responsibilities. This barrier impacts the stakeholder selection for public housing projects, hiring consultants, and volunteer actions from market players (Table 8).

Sixth, policy & practice gaps as the sixth key barrier highlight the challenges involved with policy direction, inadequate policy frameworks, and weak housing finance policy. Planning approvals, by-laws enforcement, identification of the target groups, and policy implementation were found to be associated with it (Table 9). These issues align well with the findings of Winston (2010), and Mehmood (2016). Ways forward for institutional collaboration were also discussed in a limited capacity, and research participants advised on revising organizational hierarchy, collaborative alliances with the private sector, and transforming attitudes toward civic responsibility (Table 10). An outline of the findings for the research objective to simplify the complexity and intricacy of the data involved is provided below as an exciting summary of emerged categories and properties. Interdisciplinary themes were established for this research question, being more abstract and focused simultaneously on multiple resources of the low-income housing provision system.

The synthesis of barriers and operational loopholes from stakeholders’ perspectives emerged as GLIPP according to the underlying properties against each category (Fig. 2). GLIPP presents cross-cutting collaboration barriers featuring G: government capacity, L: legislation, I: institutional complexity, P: Policy, and P: Political will. Within the GLIPP lies the weaker grounds of collaborations that affect stakeholder engagement undesirably. Configuration of the GLIPP connections places the government sector as the central focus, sharing twofold connections with legislation matters, political leadership, and institutional arrangements. The direct and one-sided impact was observed from policy gaps and lack of political will towards the government sector and state legislative processes. The mutual effect was observed in the case of weak institutional arrangements and a lack of political will. The collaboration environment was constrained as a collective of incompetent state legislation, institutional complexity, lack of political will, and practice and policy gaps.

The study presents philosophical constructs about identifying the key barriers to achieving the sustainable development goal SDG-11 of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, i.e., affordable housing for low-income groups. The achievement of SDG 11 becomes more vital in the case of developing countries where rapid urbanization leaves no option for the urban poor for adequate housing, end up in slums and squatters. The visible dilemma of poor housing demands understanding and exploring solutions to deep-rooted problems, constraining the collaborative efforts among housing providers. This research makes a theoretical contribution in the form of the GLIPP advancing the knowledge of collaboration barriers associated with low-income housing provision, which still involves more areas to explore further. The findings suggest revising the organizational hierarchy of government institutions, providing a better environment for collaboration and effective CSR from market stakeholders. Future research implies the GLIPP paradigm must focus on country-specific institutional frameworks that obstruct collaborations among housing stakeholders since limited research is available in Pakistan. As part of practical implications, this study agitates policymakers in formulating housing policies and programs for low-income groups. The scope of the present study slightly touches on the solutions to barriers on the primary level. These limitations offer salient avenues for future studies on a project basis regarding the collaborative approach for low-income housing.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are shared the data with the editors.

Notes

1 Marla is equal to 224 Square feet in Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan.

Patwari is normally known as low-level government officials being expert in dealing with land matters.

The Urdu Word Kacheri Meaning in English is Judicatory.

References

Aazim, M. (2017). Budget Impact on Housing. Dawn, The Business and Finance Weekly. Retrieved from https://www.dawn.com/news/1337531

Adabre MA, Chan AP, Darko A, Osei-Kyei R, Abidoye R, Adjei-Kumi T (2020) Critical barriers to sustainability attainment in affordable housing: International construction professionals’ perspective. J Clean Prod 253:119995

Adetooto J, Windapo A (2022) Concomitant impediments to the social acceptance of sandbag technology for sustainable and affordable housing delivery: the case of South Africa. Buildings 12(6):859

Ahmad N, Anjum GA (2012) Legal and institutional perplexities are hampering the implementation of urban development plans in Pakistan. Cities 29(4):271–277

Ahmed R, Jawaid ST, Khalil S (2021) Foreign capital inflows and housing market in Pakistan. Int J Hous Mark Anal 14(5):936–952

Akhtar AS, Rashid A (2021) Dispossession and the militarised developer state: financialisation and class power on the rural–urban frontier of Islamabad, Pakistan. Third World Q 42(8):1866–1884

Aslam, J. (2014). In conversation with Jawad Aslam_ The challenges of providing affordable housing in Pakistan/Interviewer: H. B. Malik & F. Sajjad. Lahore: Tanqeed

Average C (2019) Low income housing problems and low-income housing solutions: opportunities and challenges in Bulawayo. J Hous Built Environ 34:927–938

Azam Khan M, Ali N, Khan H, Yien LC (2023) Factors determining housing prices: empirical evidence from a developing country’s Pakistan. Int J Hous Mark Anal 16(5):936–954

Berger IE, Cunningham PH, Drumwright ME (2004) Social alliances: company/nonprofit collaboration. Calif Manag Rev 47(1):58–90

Bondinuba FK, Karley NK, Biitir SB, Adjei-Twum A (2016) Assessing the role of housing microfinance in the low-income housing market in Ghana. J Poverty Invest Develop 28:44–54

Bott LM (2018) Linking migration and adaptation to climate change. How stakeholder perceptions influence adaptation processes in Pakistan. Int Asienforum 47(3-4):179–201

Bratt RG (2008) Nonprofit and for‐profit developers of subsidized rental housing: Comparative attributes and collaborative opportunities. Hous Policy Debate 19(2):323–365

Cheung YKF, Rowlinson S (2011) Supply chain sustainability: a relationship management approach. Int J Manag Proj Bus 4(3):480–497

Choudhry RM, Iqbal K (2013) Identification of risk management system in construction industry in Pakistan. J Manag Eng 29(1):42–49

Cleophas C, Cottrill C, Ehmke JF, Tierney K (2019) Collaborative urban transportation: Recent advances in theory and practice. Eur J Op Res 273(3):801–816

Farrukh M (2022) Housing market distortions for public benefit: an example from a developing economy. In 2021 APPAM Fall Research Conference. Associayion of Public Policy & Management (APPAM). Texas, USA

Ezennia IS (2022) Insights of housing providers’ on the critical barriers to sustainable affordable housing uptake in Nigeria. World Dev Sustain 1:100023

Gandhi S (2012) Economics of affordable housing in Indian cities: the case of Mumbai. Environ Urban Asia 3(1):221–235

Javed N, Riaz S (2020) Issues in urban planning and policy: The case study of Lahore, Pakistan. New Urban Agenda in Asia-Pacific: Governance for sustainable and inclusive cities, 117–162

Jones A, Stead L (2020) Can people on low incomes access affordable housing loans in urban Africa and Asia? Examples of innovative housing finance models from Reall’s global network. Environ Urban 32(1):155–174

Kaleem A, Ahmed S (2010) The Quran and poverty alleviation: A theoretical model for charity-based Islamic microfinance institutions (MFIs). Nonprofit Voluntary Sect Q 39(3):409–428

Lowe R, Oreszczyn T (2008) Regulatory standards and barriers to improved performance for housing. Energy Policy 36(12):4475–4481

Malik S, Roosli R, Tariq F, Yusof NA (2020) Policy framework and institutional arrangements: case of affordable housing delivery for low-income groups in Punjab, Pakistan. Hous Policy Debate 30(2):243–268

Mehmood A (2016) The pillar that holds the roof, The Issue of Land in Low-Income Housing in Pakistani Punjab: A Case of Ashiana Scheme. 2nd International Multi-Disciplinary Conference, 19-20 December 2016, Gujrat

Mosley JE (2021) Cross-sector collaboration to improve homeless services: Addressing capacity, innovation, and equity challenges. ANNALS Am Acad Political Soc Sci 693(1):246–263

Muazu, J., & Oktay, D. (2011). Challenges and prospects for affordable and sustainable housing: the case of Yola, Nigeria. Open House International

Munir F, Ahmad S, Ullah S, Wang YP (2022) Understanding housing inequalities in urban Pakistan: an intersectionality perspective of ethnicity, income and education. J Race, Ethnicity City 3(1):1–22

Sourani, A., & Sohail, M. (2011). Barriers to addressing sustainable construction in public procurement strategies. In Proc. Institution of Civil Engineers-Engineering Sustainability (Vol. 164, No. 4, pp. 229-237). Thomas Telford Ltd

Zainul Abidin N, Yusof NA, Othman AA (2013) Enablers and challenges of a sustainable housing industry in Malaysia. Constr Innov 13(1):10–25

Li, X., Liu, Y., Wilkinson, S., & Liu, T. (2018). Driving forces influencing the uptake of sustainable housing in New Zealand. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management

Madden, J. (2011). Overcoming collaboration barriers in affordable housing public-private partnerships. In Academy of Management Proceedings, 2011(1). 1-6. NY: Academy of Management

Meehan J, Bryde DJ (2015) A field-level examination of the adoption of sustainable procurement in the social housing sector. Int J Oper Prod Manag 34(7):982–1004

Miller W, Buys L (2013) Factors influencing sustainability outcomes of housing in subtropical Australia. Smart Sustain Built Environ 2(1):60–83

Moore EA, Koontz TM (2003) Research note a typology of collaborative watershed groups: Citizen-based, agency-based, and mixed partnerships. Soc Nat Resour 16(5):451–460

Moore, S. M. (2005). New urbanist housing in Toronto, Canada: A critical examination of the structures of provision and housing producer practices (Doctoral dissertation, The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE)

Nadeem O, Fischer TB (2011) An evaluation framework for effective public participation in EIA in Pakistan. Environ Impact Assess Rev 31(1):36–47

Odoyi EJ, Riekkinen K (2022) Housing policy: an analysis of public housing policy strategies for low-income earners in Nigeria. Sustainability 14(4):2258

Olotuah O (2009) Demystifying the Nigerian urban housing question. 53rd series of Inaugural lecture. Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria

Selsky JW, Parker B (2005) Cross-sector partnerships to address social issues: challenges to theory and practice. J Manag 31(6):849–873

Shah S, Afridi M (2007) Assessment of institutional arrangement for urban land development and management in five large cities of Punjab. Urban Sector Policy and Management Unit Planning and Development Department, Government of Punjab, Pakistan

Siddiqui, T. (2015). Housing for the poor. [Lecture]. First Published: 2000 Republished: January 2015. Islamabad: Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI)

Uppal J (2021) Developing housing finance in Pakistan-challenges and opportunities. Lahore J Econ 26(1):31–56

Williams K, Dair C (2007) What is stopping sustainable building in England? Barriers experienced by stakeholders in delivering sustainable developments. Sustain Dev 15(3):135–147

Winston N (2010) Urban regeneration and housing: challenges for the sustainable development of Dublin. Sustain Dev 18(10):319–330

Yang J, Yang Z (2015) Critical factors affecting the implementation of sustainable housing in Australia. J Hous Built Environ 30(2):275–292

Zada, M. (2019). An Evaluation of Housing Reconstruction Programme in 2009-10 Conflict Affected Areas of District Swat, Pakistan (Doctoral dissertation, university of Peshawar, Peshawar)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM: Conceptualization, methodology, data collection, supervision, writing original draft preparation, resources, writing review and editing; MN: Methodology, resources, writing review and editing, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The ethical approval of the study protocol for this research was obtained from Human Ethics Research Committee, University Sains Malaysia.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Malik, S., Nurunnabi, M. Stakeholders’ perspective on collaboration barriers in low-income housing provision: a case study from pakistan. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 88 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02583-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02583-0