Abstract

Evidence shows the role men can have to contribute to the prevention of non-consensual relationships and gender violence, mainly fostering educational and social strategies which strengthen egalitarian male models that take consent as a key aspect in their sexual and affective relationships. In this regard, social networks show the existence of discourses that reinforce these male models. However, there is a gap in the analysis of how the previously mentioned discourses on consent are linked to men’s sexual satisfaction. The present study deepened into this reality by analysing messages on Reddit and Twitter. Drawing on the Social Media Analytics (SMA) technique, conducted in the framework of the European large-scale project ALL-INTERACT from the H2020 program, the hashtags notallmen and consent were explored aimed at identifying the connections between masculinities and consent. Furthermore, three daily life stories were performed with heterosexual men. Findings shed light on the relevant positioning of men about consent as a key message to eradicate gender-based violence; in parallel, they reveal the existence of New Alternative Masculinities that have never had any relationship without consent: they only get excited by free, mutual and committed consent, while repulsing unconsented or one-sided relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are several myths about heterosexual men’s sexual interests and desires, which are based on hoaxes and not scientific evidence. One salient example of them refers to the idea that all heterosexual men always have sexual desire for women, regardless of their lack of consent. However, research has evidenced that this statement is not real and there are men’s groups and men who are positioned against relationships without consent (Kaufman 2001). Concerning the approach to gender issues, social media is given a relevant role in their visibility. In fact, studies on the impact of social media have illustrated the effects on the reality that messages posted on virtual networks can have (Fu and Chau 2014; Zheng and Yu 2016). For instance, the gendered trolling of women was analysed by Pillai and Ghosh (2022) for its consequences on women.

The research questions that drive this study are: Do men take a stand in favour of consent, in their personal sexual relationships and in interaction with others’ behaviours? Do men desire consensual relationships and reject non-consensual interactions? In the present article, we pay attention to this issue by analysing discourses and messages which have emerged on two social networks: Twitter and Reddit. Thus, we have mainly focused on the discussions around the hashtags #NotAllMen and #Consent, which show the positioning of men and women against gender-based violence and its connection with consent. Furthermore, three life stories of men were conducted aimed at deepening this issue: this fieldwork illustrates different dimensions concerning interviewed men’s desire for consenting relationships that have not been identified in the analysis of social media.

This article is divided into four different sections. Firstly, the theoretical framework of the study will be introduced; secondly, a literature review will highlight some of the latest research relevant to our study, regarding scientific literature on masculinities, consent in affective relationships, and the relevance of social networks for strengthening the transformation processes. Thirdly, mixed methods employed in the article are described, as well as how the data analysis has been carried out. Fourthly, findings obtained through social media analytics and life stories are summarised. Lastly, a brief discussion of the results is elaborated.

Theoretical framework

This study is primarily situated within the theoretical framework and research line of preventive socialisation of gender-based violence, intersectionality and social impact research. The former examines how interactions with media and other people can help overcome violence (Gomez 2015; Puigvert 2014; Salceda et al. 2020). The central thesis revolves around the cultivation of an alternative socialisation that directs our focus, attraction, and decision-making toward egalitarian and dialogic relationships. Within this framework, the analysis of New Alternative Masculinities (NAM) is found and conceptualised: these NAM behaviours, characterised by a fusion of egalitarian values and attractiveness in the same boys and men, are to be promoted and endorsed within society. Shifting attention to such alternative attitudes could prove pivotal in reshaping preferences towards men who are not violent or dominant across various relationship dynamics.

Second, intersectionality is another theoretical approach that has been widely employed to comprehend gender inequalities directly or indirectly connected with masculinities (Crenshaw 1989). Following Crenshaw’s works (2013), intersectionality pays attention to how hierarchical power relations contribute to maintaining discriminatory practices which are linked to structural variables such as race, social class and gender. This is particularly relevant to deepening the situation of social exclusion or discrimination lived by certain vulnerable groups. In this vein, categories of class, race and sexuality can also reinforce patriarchy and men’s privilege, strengthening the legitimacy of dominant models of masculinity that uphold positions of power (Christensen and Jensen 2014). Conversely, the theory of the Dialogic Society demonstrates that these kinds of unequal power alignments are being contested by social movements and individuals who claim and build more egalitarian relations (Flecha 2022).

Last, social transformation processes are often elucidated by social impact-focused theories, illustrating how research can serve as a valuable tool for bringing about significant societal changes by highlighting realities that contribute to a better world. These realities, like the ones explained in this paper, become social creations thanks to co-creation processes engaging citizens and promoting an egalitarian dialogue with researchers (Flecha 2022; Aiello and Joanpere 2014). In this regard, there are several analyses that show the role of social science research in generating experiences that reduce or eradicate inequalities. For example, the successful action approach, which arises from European research, provides the definition of successful educational actions that are improving coexistence and academic results in schools of different parts of the world (Flecha 2014; Flecha and Soler 2014). In relation to gender, Judith Butler (2003) clearly states that feminism can lead to social transformations of gender relations. Feminism, egalitarian men’s groups and other identity movements are contributing to create new social relations shaping an alternative socialisation which strongly rejects non-consensual relationships (Soler-Gallart and Flecha 2022).

Literature review

The review of scientific literature is divided into two sections. Firstly, a review of contributions from men’s studies concerning consent is carried out. Secondly, the role of social media for social transformation is analysed, paying particular attention to those campaigns which emerge in the context of men’s engagement in initiatives that promote consent and gender equality.

Men and consent

About the contributions in the field of men’s studies, impactful and a significant amount of literature pays attention to the relevance of implementing interventions addressed to men and boys to sensitise them on the importance of consent in intimate relationships. For instance, investigations which examine the impact of these interventions stress the relevance to articulate “positive masculinities” which are centred on the performance of healthy behaviours directly linked to male gender identity (Carline et al. 2018; Orenstein 2021). However, other contributions call into question the capacity of these actions to transform hegemonic masculinities (Jewkes et al. 2015), a typology of masculinities which still has an important influence in men’s behaviours (Connell 2012; Flecha et al. 2013; Guarinos and Martín 2021; Padros-Cuxart et al. 2021).

There is another body of literature which examines the characteristics of some strategies addressed to men aimed at raising awareness about consent in sexual and affective relationships. One example of these strategies is those which are launched at university campuses where campaign posters are placed in strategic spaces, such as toilets, student unions, and pubs. These campaign posters include key messages related to consent, such as ‘Can’t answer? Can’t consent – sex without consent is rape’ (Carline et al. 2018). However, there is a significant academic debate about the impact of these informative strategies on men, particularly because several limitations are identified linked to how tailored these strategies are to local and regional realities where they are implemented (Casey and Lindhorst 2009).

From another perspective, there are analyses of consent linked with the construction of masculine models. For instance, Beres (2010) stipulates young men hold ideas about consent as a tacit understanding; therefore, they used to employ statements such as ‘you get a vibe’ and ‘just feel it in the air’. On the other hand, other conceptualisations relativise sexual abuses using sentences such as ‘sort of just happens’, thus diminishing the importance of consent in intimate relationships. In fact, studies on socialisation related to this type of relationship show how this is strongly influencing social imaginaries about women, who are sometimes perceived as sexual gatekeepers.

Recent developments in men’s studies have introduced alternative conceptualisations, different from the above-mentioned, which provide new insights on the positioning of men concerning consent. Thus, the New Alternative Masculinities’ approach (NAM) (Ríos-González et al. 2021) pays attention to the active positioning against gender-based violence and abusive relationships. However, one of the distinctive elements of this approach concerns how New Alternative Masculinities men look for relationships that combine freedom, equality, and passion, so desired consent from all parts is necessary. The last findings in this field illustrate a distinction between traditional and alternative models of masculinities. In the first case, there are the Dominant and the Oppressed models. The Dominant Traditional Masculinities refer to the typology of masculinity, which exercises violence and domination. The Oppressed Traditional Masculinities are not aggressive but become passive in front of discrimination and inequalities (Ríos-González et al. 2021). In addition, the former is socially perceived as attractive, and the latter as unattractive (Puigvert et al. 2019).

Since the beginning of the study of men and masculinities, outstanding scholars like Connell have identified the pressure that men experience to follow a Dominant model, which is reinforced by a social coercive discourse that breaks the relationship between beauty, goodness and truth and gives social value to men who not only do not improve relationships but actually make them worse with their disdain and power (Puigvert et al. 2019). Nonetheless, research suggests that New Alternative Masculinities become an alternative to this double standard generated by traditional models because they combine a clear positioning in front of gender-based violence and awaken desire with their actions (Flecha et al. 2013).

In Butler’s terms (1990), gender exists because it is socially performed, which means that the construction of gender patterns has a relevant role in shaping people’s identities. She stated heteronormative matrix is also conditioning men’s socialisation, pushing them to reject feminine behaviours and reproducing hegemonic values. Nevertheless, as mentioned earlier, the New Alternative Masculinities’ approach confirms the existence of an alternative socialisation which confronts this normativity promoting more diverse masculinity models away from the dominant ones.

Social media and transformation

The second facet that this literature review explores is the role of social media in current societies. In this respect, social media can be employed as an instrument that, on one hand, fosters Islamophobia, chauvinism, and homophobia (Awan 2016; Leppanen et al. 2016); or, conversely, could become a tool to engage citizenship in transformative actions with a significant social impact (Roth-Cohen 2022; Soler-Gallart and Flecha 2022; Pulido et al. 2018; Redondo-Sama et al. 2021). However, the existence of a coercive dominant discourse, as previously explained, present in society and expressed as well in social networks such as Instagram or Twitter, is linking attractiveness with violent and risky behaviours (Villarejo et al. 2020). This discourse is influencing young people’s socialisation, making them more vulnerable to affective and sexual relationships where this connection emerges. More attention will be paid to all these aspects, which are under the purpose of the research we have conducted.

More linked with the research we have performed here, there are analyses about social media and social transformation, which have evidenced that virtual networks are accelerating activism communication and are making the work of social movements more visible (Poell 2014; Maaranen and Tienari 2020). This is evident in the experiences on social media driven by specific campaigns and hashtags. For instance, Zheng (2020) analyses #NotAllMen as a hashtag that has reached a wide audience, although she insists on the fact that several feminist voices have been very critical of it. They argue that it is only restricted to harassers, rapists, batterers, and perpetrators of sexism, concluding that more distinction is needed to properly understand the role of men in the prevention of gender-based violence.

There is another campaign and hashtag strongly linked to the involvement of men in gender equality and violence prevention, #HeForShe, which has been promoted by the actress Emma Watson since her discourse at the United Nations Headquarters in 2014. As it was demonstrated in Samarjeet’s (2017) analysis, this hashtag encouraged many male celebrities to express their solidarity with women and contributed to creating global rhetoric on the relevance of involving men in gender equality. After this impact, the United Nations created a global social movement that is enabling the implementation of a set of actions addressed to question gender inequalities and stereotypes from a male standpoint.

While covering these issues, there is a scientific gap on the rejection of non-consent and, complementarily, desire towards consent. Moreover, no studies have analysed alternative interactions from men regarding consent. This manuscript endeavours to address the existing void by analysing online dialogues and engaging with a sample of heterosexual men who are actively participating in an egalitarian men’s movement. The evidence found in this study, and presented in this paper, seeks to make a meaningful contribution to the transformation of gender roles and the engagement of egalitarian men in consensual relationships. This transformation is facilitated through the promotion of New Alternative Masculinities, fostering change in both online and face-to-face interactions.

Materials and methods

This research started with the concern of what would the debates on social media be regarding men and consent. More specifically, there was an initial hypothesis that there is growing criticism of non-consent and towards men who perpetrate or reinforce it, while, and most importantly, there is a growing active involvement of men in opposing gender-based violence and only seeking relationships based on consent.

This study is framed within the ALL-INTERACT project from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (ALL-INTERACT, 2020–2023). This project aims at Widening and diversifying citizen engagement in science, grounded on the perspective of the social impact of research.

Our study follows a Communicative orientation (Redondo-Sama et al. 2020). This Communicative Methodology aims not only to analyse social realities but also to find solutions that can help overcome injustices and inequalities, with the aim of informing social transformation through research. This methodological approach focuses above all on breaking the hierarchy between researcher and researched, breaking with the idea of interpretative unevenness. Analyses conducted under this methodology are based on the creation of scientific knowledge through egalitarian dialogue, with the primary goal of reducing social inequalities. Next, the data-collection techniques are summarised, that is, the Social Media Analytics and the communicative daily life stories. Their design, implementation and analysis follow a communicative orientation.

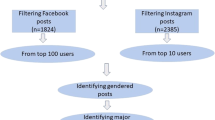

First, the Social Media Analytics (SMA, hereinafter) carried out is explained. Reddit and Twitter were the social media platforms chosen for the analysis of posts, comments, and debates given their public dialogue nature, where any user can join an open conversation, read and participate. Precisely, the search unit we employed was NotAllMen and Consent, in the form of hashtags and keywords; these words were searched separately and combined. The objective was to see what people, not only men, talk about regarding consent and men. We initially analysed all messages that contained those words and additionally explored the threads where such messages were inserted to include reactions and responses.

Twitter was openly explored: according to the criteria described above, over two thousand Twitter messages -including the initial tweet, answers and retweeted messages- were read and analysed. On Reddit the search was centred on the following subreddits with a connection to the research purpose and which were obtained from the work of ALL-INTERACT. This European project funded this study and had two focus fields: the subreddits Feminism, Feminisms, Bisexual, FeMRADebates and PurplePillDebate related to gender issues; the subreddits ApplyingToCollege, Education, Science, Teachers and Teaching were focused on education. We were able to utilise this data extraction and analyse its content in search for findings that met our research goals in two fields of great importance for the issue of consent: gender and education forums with great participation. Excel files containing messages from those subreddits added up to a total of 58,114 posts and comments, which were filtered to analyse those that included the target words and hashtags NotAllMen and Consent. The messages finally included in the results section were selected because they answered the purpose of the research. For data protection purposes, no literal excerpts will be presented, but rather descriptions and paraphrases of such comments.

To introduce the communicative daily life stories, it is important to note that our goal was not to provide a comprehensive and representative analysis of men’s perspectives about consent, but rather to complement the SMA to fill the gap that social platforms did not incorporate in filling with statements from egalitarian men who may reject relationships not based on mutual consent and who would be most excited by enthusiastic consent. To achieve that, the inclusion criteria were men from an intentional sample who had participated in groups of men who discuss relationships that combine egalitarian values with desire and passion. Thus, the research team contacted a Spanish men’s movement familiarised with scientific articles on consent and new alternative masculinities that they regularly debate. After being contacted, three heterosexual Spanish men between 35 and 45 years with a long trajectory on the movement and with significant knowledge of the aforementioned topics of age linked to a network of men who debate New Alternative Masculinities and the overcoming of gender-based violence were selected and then interviewed.

The technique chosen was the communicative daily life stories, where a specific topic is discussed based on the life experiences lived, which are put to reflection with the scientific evidence on men and consent that the researcher shares. During the conversation, the participants were asked to share insight about excitement and consent: they talked about their level of satisfaction towards consensual encounters and the way they felt about relationships where consent or reciprocity cannot be ensured. After analysing the interviews, the most repeated results were categorised considering the above-mentioned hypothesis.

The results were analysed following the communicative orientation. An initial general category, “Effects on consensual relationships”, was drawn from the literature reviewed and the research objective. Then, the transformative and exclusionary dimensions were differentiated: the exclusionary dimension includes the debates and comments that perpetuate non-consent relationships; the transformative dimension includes “Debates and comments that help overcome non-consensual relationships” (see Table 1). Posts, comments and quotes that included the keywords, or referred to them, were analysed following the main category drawn from the literature and the emergent subcategories.

Results

The results are presented in different categories following the ones established in the above-described data analysis procedure. Therefore, subsections ‘Exclusionary dimension: debates and comments that perpetuate non-consent relationships’ and ‘Transformative dimension: debates and comments that help overcome nonconsent relationships’ refer to the exclusionary and transformative dimensions of the main category, respectively.

In this section, we would like to underline that we draw on the conceptualisation of validity claims performed by Habermas (1984) and updated by Soler and Flecha (2010), which focuses on the arguments based on sincerity, truth and normative rightness. Thus, validity claims are contrary to power claims, which are framed on hierarchies and power positions.

Exclusionary dimension: debates and comments that perpetuate non-consent relationships

This section analyses the exclusionary dimension of the results: issues that arise from the comments and debates on Reddit and Twitter related to the chosen hashtags that make it difficult to overcome violence against women and gender violence. Data has shown the presence of debates and comments that pose barriers to overcoming relationships without consent.

The instrumental use of #NotAllMen acts as an excuse for some men to perpetrate and get away with unconsented actions. For instance, a tweet reports gay men touching women without their consent but justifying that they are not sexually attracted to them. Much more extended are conversations where the rape culture is strengthened. Some male posts include the views that a woman’s “no” actually means “yes”, or that they just need to be “warmed up”. An open discussion on Twitter expressed the ideas of a man who argued that men have to insist because girls have learned to say “no” initially out of fear of looking easy, and that if men simply complied none would ever get laid. He shared a story where he respected the “no” of a girl who he later found out had ridiculed him with her friends with an insult regarding his sexual abilities, and that the following day she had called her vile ex to have sex because the first guy had left her sexually frustrated. What is more, the girl’s friends offered him a solution that is not focused on consent and communication, but rather on techniques to have sex from an instrumentalised and senseless point of view.

Related to the previous interaction, we highlight a man’s reflection of how women, he argues, engage in more or less consensual sex depending on whether men are more of a dominant or a nice-guy type. The comment shows that, with dominant men, women would consent to certain sexual practices he considers degrading, but which they would not have consented to with a non-dominant man. This statement can be aligned with previous research where it is noted that the existence of a dominant coercive discourse, linking attractiveness to bad boys and emptying nice guys of desire, is influencing socialisation processes with regard to affective-sexual relationships (Puigvert et al. 2019).

Both women and men express how some men behave differently whether in the presence of women or when they are among other men: those men act decently when addressed individually or among women, but openly exhibit misogynistic and anti-feminism comments and ideas when only men are present. Linked to that, some anti-violence men express on Twitter a popular and extended sense of silent and permissive brotherhood from some dominant men with any men, with whom they feel safe to say comments that perpetuate the rape culture. Critical debates about such situations are found in Twitter, and they include criticism of a larger group of less dominant but unconfident men who are nonetheless dragged along, wanting to fit in, and either stay silent or even encourage or reinforce the initial comments or behaviours.

Some female Reddit users express resistance to understanding the lack of consent from some men in different situations. For instance, a doctor stole a woman’s number from personal data to ask her on a date, to which she felt stalked; her male friends excused this behaviour as understandable, as “he was taking his chance”. Another issue that different users point out is the difficulty to identify men who do not care about consent when deciding whether to have a relationship with one.

Some difficulties, concerns, and doubts are shared on how to induce change in such dominant men. Contrary opinions are shared on the role that male friends can have in stopping comments. On the one hand, the problem of being a minority that stands up against them is thought to result in no positive impact. This lack of impact in individual actions can go from not taking the comment seriously to receiving attacks, which discourages them from future standing up because they feel it is not worth it. Men identify how not having a strong network is turning into a barrier for them.

Debates showed different elements as to why non-violent men do not feel empowered or ready to stand up to violence against women. An issue that discourages some non-violent men’s involvement is “being put in the same boat” as the offenders, which frequently happens: they may be labelled as contributors or the problem, and attacked online for it. Further, at times when these men call out all forms of violence, including those perpetrated by women, they are attacked as misogynistic. Some spaces with a supposedly feminist standpoint seem to fuel this notion and its consequences, sharing repeated messages that “all men are evil”. Likewise, some comments state that men who have healthy relationships should not be valued because that is what should be normal; some men themselves, when they support victims or the fight against gender violence, respond defensively because they should not be promoted for doing “the bare minimum”.

Some men show in different online debates struggles in knowing how to flirt, while they seem to try to learn not by engaging in meaningful conversations but by reading self-help guides. They do not believe there are successful alternatives to the dominant model of insisting on women. That leads these men to hide their sexuality to ensure women are not bothered by them, but such an attitude results in women never taking them out of the friend zone. Consequently, to the internalisation of the idea that “successful masculinity is only found within traditional approaches”, these “nice guys” express their need to adopt dominant behaviours due to their initial lack of success and the actual success they achieve when they behave badly. Linked to this, a woman on Reddit expresses her view that most men are very romantic and loving towards women; to this comment, a man’s answer expresses that many men are initially like that, but after some bad experiences, they are taught by women that those attitudes will not bring them any success. Therefore, to appear attractive to women, those initially egalitarian men feel like they have to train themselves not to be kind, even if most of them resist that mindset and keep on longing for mutually loving relations.

Non-scientific debates on men and consent

Next, we explore comments and debates that are not supported by scientific evidence. These conversations, which may be rooted in hoaxes related to gender issues, are not focused on discussing solutions or transformative proposals for the prevention of gender violence, specifically around consent.

The hashtag #NotAllMen is widely seen and explored. This hashtag is mostly used by men who claim never to have committed sexual assault or violence against women and state that they are not like that, even though they have not been personally accused. They act defensively, interfering in debates where women, and sometimes men, have conversations about experiences of non-consent or gender violence. It is then when these men alter the course of the discussion and, not caring for the victim’s feelings or offering any form of ally-wise support, interrupt the debate to let everyone know they would not do the aggression being reported and criticised. As a consequence, victims and people who support them feel their concerns undermined.

Some men use hoaxes that deny the gendered base of violence, alluding to false reports from women being assaulted or to statistics being wrong. Certain profiles manipulate cases and statistics of male sexual abuse to strengthen misogynistic beliefs; or use men’s suicide stats to bring up men’s issues as a tool to switch the approach of the subject, silencing victims’ voices.

Last, some debates introduce incorrect biological assumptions about innate sex drive differences between men and women, which are used with ulterior motives to justify some men’s behaviours. Likewise, non-scientific conclusions that account for more self-control in women than in men are explained and used to justify some men paying for sex, even if they criticise such behaviour.

Transformative dimension: debates and comments that help overcome non-consent relationships

This section summarises the transformative dimension of this study: well-reasoned and impactful critiques against comments that perpetuate the non-consent culture, and against male inactive bystanders. Firstly, the #NotAllMen hashtag is strongly criticised; it is argued that nobody created an initial #AllMen hashtag (referring to all men being aggressors) to which the #NotAllMen hashtag had to be counter-used to make justice.

As another validity claim against #NotAllMen comments, very diverse comments and posts state the widely-held view that the men who harm women are a minority, but declare that this is not the point of the conversation. Some comments use #SomeMen to refer to perpetrators of the worst gender violence, such as rape or murder, to move the attention towards less grave but still worrisome situations that many women suffer, which all portray cases of harassment and violence that create the base of a pyramid of violence: that includes actions boys and men perpetrate, from looking under a girl’s skirt to “slut shaming”. These comments express a wide range of situations of violence against women concerning consent.

In a complementary way, there is a public accusation of men who are accomplices and who therefore support rape culture: some of the behaviours they criticise include men letting rape jokes slide, looking the other way because “it’s none of their business”, or not seeing the problem of using the “boys will be boys” statement.

We found repeated criticism towards people, mainly men, who act defensively but may be incoherent and stand by in face of non-consent situations. That critique is frequently supported by the notion of not being part of the solution: many female users ask if all men do what they can to ensure that other men do not harm women, by stopping bad behaviours or engaging in conversations about women’s safety and consent with their sons. They encourage those men that, before writing #notallmen, they share all their actions in defence of consent and women, such as campaigns, talks in schools, or gatherings to discuss male violence. Otherwise, they argue, it appears as if they seek recognition for not engaging in sexual assault. Some hashtags that reinforce this bystander critique include #TooManyMenNotSpeakingUp and #TooManyMenProtectingHorribleMen. Other users explain that bystanders are evil as well as the aggressors, for seeing hostile situations and doing nothing, since by looking the other way they are endorsing dominant men to escalate to worse behaviours. In this sense, the New Alternative Masculinities approach has demonstrated that alternative men’s positioning and rejection is a transformative response to these men or men’s groups complicit in the perpetuation of non-consensual relationships (Nazareno et al. 2022).

Transformative debates on consent and men: men who stand up against gender violence reject non-consent in their relationships

Next, transformative conversations regarding consent and men are presented. These debates offer alternatives, advice based on enthusiastic consent, or help men stand up to violence against women.

Educating about consent is a shared concern and a successful preventive strategy for many people, both in educational institutions and within families. Sex education in high schools seems too late for many, as they argue it should start in preschool years with non-sexual situations, with notions such as consent for physical touching. Regarding teaching consent in sexual-affective relationships, some comments include critically addressing from the “no means no” to a “yes means yes” that takes into account non-verbal communication. Further in that sense, some debates on Twitter express that the ultimate goal to be pursued when discussing consent with youth should be mutual enjoyment and good sex. Educators and parents showing themselves as available for open and continuous dialogues with youth are important for these social media users; from their perspective, adults should frequently engage in critical dialogue about situations they watch together in movies so that they distinguish whether there was or not consent. Another man shows his determination that we should teach our young men about what it is to be a man in sex, “which always starts with consent”. The tea metaphor for learning consent video is shared as a useful resource, with over 20 million views on YouTube. Mention is made towards preventive, governmental and systemic approaches that include the educational system and all social spheres, such as the police and workplaces.

Training men to become confident and successful upstanders is also discussed. Many public campaigns, such as #AllMen by Women’s Aid Organisation, have this approach. For instance, men who lead the men’s engagement campaign “Don’t be that guy” express that men do step up and want to engage in dialogue and action about these issues: one of them explains that since the beginning of one of the campaigns he had been receiving positive daily messages from men, as well as support from women. Some of the famous men portrayed in the campaigns further develop the campaign in their media profiles, having conversations with experts who discuss scientific evidence of the impact of male sexual entitlement on violence against women.

Following that course of action, it is clearly expressed the need for men to have an active role in stopping violence by changing the atmosphere, rather than just an intrapersonal approach to changing their own actions. That involves, they say, retaking social spaces where sexist men think that their misogyny is accepted until they have no spaces where they feel their behaviours are normal. Some comments acknowledge that “leaders set the tone”, but criticise looking up because that encourages the bystander effect -people waiting for others to intervene. In this sense, the bottom-up community approach is reinforced, stressing the need for everyone to be an upstander.

Many discussions on social media, involving both men and women, focus on criticising and condemning non-consent relationships and situations mostly shared by women while expressing support to the victims. When women break the silence online and speak up about a situation they suffered, many men show messages of empathy, support, and rejection of the offenders and their behaviours.

Some debates in social media show that many people choose not to engage in a conversation with other people who are not interested in having an egalitarian dialogue focused on collective solutions; these persons move away from such encounters and focus their energies on those who are willing to engage in respectful and constructive dialogue. Users choose to mute Twitter threads when “gender-critic trolls” invade it with ill-intentioned comments; others choose to stop interactions and relationships with the most dominant men in their environments because it is counterproductive to intervene as an isolated action.

Struggles from unconfident men who care about consent are mostly met with support and advice from other men. That advice includes being assertive and confident about one’s desires, while maintaining an open mind to what the other person may want and being willing to stop. These conversations offer advice about building up a relationship so “it’s pretty clear” that the other person feels comfortable with them before asking for a date or a kiss. Being thoughtful and considerate towards the other person is also appreciated among some men’s debates and seen as a virtue, even if that means some women will lose motivation because they are not used to such kindness. According to the comments analysed, this is not seen as the man’s problem but as the woman’s loss.

There is a repeated understanding of the essential role of men in overcoming gender violence. Conversations about men standing up to violence against women support the idea that there are allies in men who portray an alternative masculinity model; female users value how “they raise the bar about what it means to be a good man”. Women in these debates emphatically talk about the fact that male allies exist. These comments are socially valued in terms of the relative number of likes they receive compared to the rest.

Men openly express their collective need to stand up against male offenders. They do it by writing blog articles that they publish on social media or which are disseminated by others; they stand up by posting videos where their public positioning against violence is explained, while encouraging other men to share their upstander statements to the world, claiming their bottom-up transformative potential. Some of these male allies have thousands of followers, but there are many more men who are not public figures and who make comments and show their egalitarian attitude. Some brave statements from men in #NotAllMen debates describe their commitment to be exempt from double standards against gender violence: they argue they do not feel offended by the public debate because they know they would stop any form of violence even if that meant standing up to a friend. Concrete examples of possible reactions and answers against dominant behaviours are discussed and offered in the debates. Real stories of men taking a stance against violence are shared, which manifest as verbal or non-verbal communicative acts, such as a disapproving and strong gaze to keep other men in check. Users identify these behaviours in their male friends and relatives.

The hashtags analysed also included profiles of men’s groups that promote boys’ and men’s engagement to end gender violence. “What Can I Do?”, “Beyond Equality” and “White Ribbon” are more repeatedly found in users’ debates. An attached article about Beyond Equality describes how the project experienced a significant increase in men registering for their training following the femicide of two women from their country.

Men who reject violence also use these social media debates to ask what they can do to be more active allies. This allows for encouraging and resourceful advice from both women and men. Suggestions include sharing studies about gender violence on social media, amplifying women’s voices, or even being willing to let go of friends because of how they treat women. These suggestions include reasons for having other men in check, such as the need to call out any small attitude to prevent it from building up to assault, because dominant men cannot interpret, they will be tolerated for anything they may do. Some answers insist that ignoring and letting it happen makes you part of the problem, and that collective actions are needed and have the most impact because all men doing something would result in an avalanche of actions.

Having conversations, not with dominant men but rather between egalitarian men, is a strategy with the preventive potential to also change the culture: people comment suggestions such as male spaces about sharing what each of them is doing, to realise they have the same objective and to inspire others to action. Specifically, including boys in the conversation is an option men suggest to break the “boys will be boys” mentality, better equipping them with the right skills.

Men of all ages, countries and cultures show these critical attitudes that transform bystander inaction into allyship attitudes. Some may recognise their past bystander conduct, but strongly state that they are no longer part of the problem because they are active allies who act with solidarity no matter the personal consequences.

Male aversion to relationships without mutual and enthusiastic consent

This section and the next one are made from the comments of the three men interviewed. These are heterosexual men who participate in groups of men who dialogue around scientific evidence on preventive socialisation of gender-based violence (Gomez 2015). The participants express that not only do they reject non-consent relationships because it may be morally wrong, but because they do not enjoy them: “I have never had a need to look for relationships without consent, it is the opposite to arousal, it doesn’t turn me on”. These men do not seek the other person’s consent to appear as nice guys but because it’s the only way they can truly enjoy their relationships:

I did not guide my actions so that the other person would consent, I did it for myself because… no, no, I couldn’t get my head around it [that the other person would not be enthusiastically into it], I didn’t like it, I got the creeps. Even on a sexual level, an emotional level, feeling that the person who was with you was not all over you, hmm… I didn’t like it, I felt like something was off.

Rejection is expressed not only in unconsented relationships, but in instrumental or unilateral situations: “If the other person is not there 100%, I do not want it either, but not just because I say “no, this isn’t right”, but because I no longer want it, I’m not turned on anymore.” Another participant expresses it like this: “From what people say, it’s like turning sex into some kind of routine, a task on a checklist, and you can tell me what is the point…”. This fragment and the following clearly express these men’s views on relationships with and without desired consent:

Of course, that [an unenthusiastic encounter] is a drag, you have already taken away not only magic, but that point of intensity; it’s like anything, you can do it 100% with maximum commitment and thus it is fun, pleasant, unrepeatable but you want to repeat it because you had such a great time; or it can be as if you were checking that task off your checklist; and of course turning sex into that, you tell me about it… and of course, that needs consent, obviously, otherwise, you tell me about it…

Men who only enjoy consensual and committed relationships

Ideals of sexual-affective relationships that combine enthusiastic and mutual consent are shared by men on social networks. Some speak about never having had sex without enthusiastic consent, since that is a basic sign of dignifying and respecting women. Others project their dreams of a relationship onto the future, speaking with desire about intimate and loving situations such as cuddling or holding hands, or about sex, stating that the greatest thing is making her feel good as well. Men in these conversations share a wide range of sexual encounters, which nonetheless include communication and consent as essential, regardless of the stage of the relationship.

All participants in the communicative daily life stories show that the only way for them to allow and enjoy any sexual-affective relationship is not only by mutual consent but by mutual commitment: “What I like is seeing that the other person is with you, that she is well, and that you are with her, that you are comfortable, and to me that makes me lower the nervousness pulse and turn up the excitement pulse.”

In the following quote, It becomes evident how a participant in our qualitative study connects consent and desire; for him, it is not possible to separate both things because desire appears when consent is clearly observable:

What I find most exciting is giving yourself. The way it feels like fireworks is when there is this full commitment, and these moments where you kind of lose the sense of time (…); but of course, that only happens, the way I see it, when there is that possibility to commit fully; therefore, since it is a form of interaction like any other, then of course, if the other person doesn’t consent, they can’t be like that [committed], and if they can’t be like that…

Last, an interviewee points out that dreams linked to an ideal relationship have been crucial in his life. Therefore, in that case, this element serves as a preventive factor that explains better choices that connected consent and enjoyment:

In some way, I thought (…) I wanted sexual-affective relationships to be something else; something was there within me that drove me to look for beauty and kindness in relationships, and I believe that has been a lifejacket (..), not only to be okay, but to have a good time as well, because we have seen what the alternative is…

Discussion

This manuscript supposes an advance in research regarding social media and consent, due to its communicative and mixed methodological approach and its focus on men. Thus, it is giving voice to these models of brave masculinity which are connected with good values, and the research is committed to looking for such standpoints that generate unprecedented knowledge which can contribute to improving sexual and affective relationships. Findings show that public debates on Twitter and Reddit have both an exclusionary and a transformative dimension. Among the negative interactions that perpetuate gender-based violence, we found how the #NotAllMen is used to excuse men and switch the centre of attention, making victims lose credibility. Additionally, some women ridicule men who stop at the first sign of non-consent. Both things would be strengthening non-egalitarian relationships with dominant men (Valls-Carol et al. 2021).

Misogynistic men seem to feel comfortable when they are surrounded by only men because those usually do not challenge them. A difficulty to identify predatory men before engaging in a relationship is shared. Literature supports this idea, especially in sporadic relationships (Torras-Gómez et al. 2020), where there is little chance to get to know the other person. When deciding to stand up to dominant men, there is a risk of suffering reprimands -which the literature refers to as Isolating Gender Violence (Aubert and Flecha 2021), especially if there is no collective positioning, and this fact discourages some men’s upstander behaviours. In this sense, there are analyses that emphasise the importance of addressing these typologies of violence from an intersectional perspective, calling for the creation of an Intersectional Gender-Based Violence Movement. This would make it possible to study and address the problem by considering the creation of networks of survivors who are contributing to overcoming violence and who present very diverse typologies of discrimination, including gender identity, sexual orientation or cultural and ethnic origin (Gill 2018).

Comments that put egalitarian men and offenders on the same boat, stating that all men are potential offenders, provoke similar effects. Scientific conceptualisations on masculinities with a transformative dimension (Flecha et al. 2013) clearly express that only some men with a Dominant Traditional Masculinity exercise violence, while many others who remain inactive and accomplice to it have an Oppressed Traditional Masculinity; but there exist New Alternative Masculinities (NAM) who do not tolerate any violence and act upon it to protect the victims with confidence and strength.

In this regard, these men should not receive praise for merely meeting the minimum expectations. Contrarily, evidence shows the need to include the language of desire towards these New Alternative Masculinities aimed at inducing social change (Melgar-Alcantud et al. 2021; Puigvert et al. 2019). In fact, not offering this alternative as a successful and desirable one risks that “nice guys” who do not have success with women may become dominant because they see that as their only “successful” option (Puigvert et al. 2019). In this way, New Alternative Masculinities radically position themselves and seek sexual relations where there is consent because this is what excites them sexually. When there is no consent, there is a lack of motivation. Thus, in their sexual relations, New Alternative Masculinities look for people who treat them as equals, as this generates greater sexual pleasure for them (Joanpere et al. 2021).

Many transformative debates are analysed in this study. They focus on educating about consent at all ages and the power of having continuous and critical dialogues with children, with special mention to addressing boys and men; it is key to have those dialogues based on scientific evidence (Villarejo-Carballido et al. 2022). In that line, different campaigns, especially on Twitter, debated that breaking the silence fosters men’s engagement, and many comments acknowledge that many men are already committed. Indeed, the #MeToo movement has already shown the potential of online solidarity networks, which can take place among men as well, and help overcome the potential reprisal for stepping up, what is known as Isolating Gender Violence (Nazareno et al. 2022). It is these kinds of movements that Butler (2022) argues are working from a position of nonviolence for social transformation. Their ethical stance is one of the bases of their struggle for equality and peace.

This reality contrasts with another one also analysed by studies such as Trott’s (2022) in which the use of YouTube comments in a campaign promoting alternative masculinities can be a niche for derisive comments typical of Traditional Dominant Masculinities (Flecha et al. 2013; Al-Rawi et al. 2022). Works such as Díaz-Fernández and García-Mingo’s (2022) express how online platforms such as Forocoches validate digital (hegemonic) masculinities; while we argue that online means merely facilitate the emergence of those already internalised dominant attitudes, indeed exacerbated by a culture of tolerance and a law of silence, which indeed needs to be broken.

We found in the interviewed men that they strongly reject relationships without consent, using a language of desire because they do not get aroused if women are not into it as well. In this regard, these men show in different ways their desire for relations with mutual and enthusiastic consent (Joanpere et al. 2021). The advice between men in that regard is seen as well in social media, showing a re-enchantment in dialogue (Gomez 2015) and a focus on communicative acts (Rios-Gonzalez et al. 2018); they also share brave examples of male positioning against potential harassment and provide reasons why all should engage to leave offenders alone.

Similarly, the three interviewed men affirm they are only turned on by relationships where all parts are committed, independently of the type of relationship. In a broader sense, this study highlights the need for research on successful and egalitarian types of men, such as New Alternative Masculinities, and their role in fostering passionate and egalitarian relationships across various contexts, including mass media. The paper contributes to universal goals, such as SDG5, providing evidence that, shared with citizens, can foster more transformative actions and help overcome non-consent relationships.

Conclusion

Following our research questions and with the data analysed, men with traits of New Alternative Masculinities (NAM) show attitudes that play a critical role in eliminating non-consensual relationships. These men are making visible their rejection of non-consensual relationships, as well as explicitly stating that they enjoy their affective-sexual relationships much more when there is consent on both sides. This last aspect has not been found in any of the debates that have been evaluated in the social networks analysed, so the qualitative fieldwork has provided relevant and complementary knowledge to the research. In fact, this complementarity is visible in many of the posts where many men, through the hashtag #notallmen, express a position in favour of relationships with consent and a rejection of gender-based violence or harassment.

Lastly, we would like to highlight that the present study has some limitations: the sample size of men interviewed is relatively small and belongs to an intentional group. Future research could analyse dialogues between different groups of egalitarian men, which can positively influence peer learning about consent and effective responses to violence. Moreover, in future research, it would be relevant to conduct a quantitative analysis of social media discussions to determine the percentage of men exhibiting NAM characteristics, because this is a step pending in the analysis undertaken in the present study.

Data availability

The data that were used for this study are not available for the general public, since they contain personal information on sensitive topics about gender-based violence. However, it can be made available upon reasonable request by email to the corresponding author.

References

Aiello E, Joanpere M (2014) Social creation. A new concept for social sciences and humanities. Int Multidisc J Soc Sci 3(3):297–313

ALL-INTERACT (2020–2023) Widening and diversifying citizen engagement in science. Horizon Europe. European Commission

Al-Rawi A, Siddiqi M, Wenham C et al. (2022) The gendered dimensions of the anti-mask and anti-lockdown movement on social media. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9:418. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01442-8

Aubert A, Flecha R (2021) Health and well-being consequences for gender violence survivors from isolating gender violence. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(16):8626

Awan I (2016) Islamophobia on social media: a qualitative analysis of the Facebook’s walls of hate. Int J Cyber Criminol 10(1). https://www.zenodo.net/record/58517/files/ImranAwanvol10issue1IJCC2016.pdf

Beres M (2010) Sexual miscommunication? Untangling assumptions about sexual communication between casual sex partners. Cult Health Sex 12(1):1–14

Butler J (1990) Gender trouble: feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge, New York

Butler J (2022) The force of nonviolence: an ethico-political bind. Verso Books, New York

Butler J (2003) Gender trouble. Cont femin reader: 29-56

Carline A, Gunby C, Taylor S (2018) Too drunk to consent? Exploring the contestations and disruptions in male-focused sexual violence prevention interventions. Soc Leg Stud 27(3):299–322

Casey EA, Lindhorst TP (2009) Toward a multi-level, ecological approach to the primary prevention of sexual assault: prevention in peer and community contexts. Trauma, Violence Abus 10(2):91–114

Christensen AD, Jensen SQ (2014) Combining hegemonic masculinity and intersectionality. NORMA: Int J Mas Stud 9(1):60–75

Connell R (2012) Masculinity research and global change. Masc Soc Chang 1(1):4–18

Crenshaw K (1989) Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine. Univ Chic Leg 140:139–168

Crenshaw KW (2013) Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of colour. In The public nature of private violence. Stanf Law Rev 1991:1241–1299

Díaz-Fernández S, García-Mingo E (2022) The bar of Forocoches as a masculine online place: affordances, masculinist digital practices and trolling. New Media Soc 2023. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221135631

Flecha R, Soler M (2014) Communicative methodology: successful actions and dialogic democracy. Curr Socio 62(2):232–242

Flecha R, Puigvert L, Rios O (2013) The new alternative masculinities and the overcoming of gender violence. Int Multidiscip J Soc Sci 2(1):88–113

Flecha R (2022) The dialogic society: the sociology scientists and citizens like and use. https://hipatiapress.com/index/en/2022/12/04/the-dialogic-society-2/

Flecha R. (2014) Successful educational actions for inclusion and social cohesion in Europe. Springer

Fu KW, Chau M (2014) Use of microblogs in grassroots movements in China: exploring the role of online networking in agenda setting. J Inf Technol Politics 11(3):309–328

Gill A (2018) Survivor-centered research: towards an intersectional gender-based violence movement. J Fam Violence 33(8):559–562

Gomez J (2015) Radical love: a revolution for the 21st century. Peter Lang Publishing

Guarinos V, Martín ISL (2021) Masculinity and rape in Spanish cinema: representation and collective imaginary. Masc Soc Chang 10(1):25–53

Habermas J (1984) Theory of communicative action, volume one: reason and the rationalization of society. Beacon Press

Jewkes R, Flood M, Lang J (2015) From work with men and boys to changes of social norms and reduction of inequities in gender relations: a conceptual shift in prevention of violence against women and girls. Lancet 385(9977):1580–1589

Joanpere M, Redondo-Sama G, Aubert A, Flecha R (2021) I only want passionate relationships: are you ready for that? Front Psychol 12:673953

Kaufman M (2001) Building a movement of men working to end violence against women. Development 44(3):9–14

Leppanen S, Westinen E, Kytola S (2016) Social media discourse, (dis)identifications and diversities. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=XUQlDwAAQBAJ

Maaranen A, Tienari J (2020) Social media and hyper‐masculine work cultures. Gend Work Organ 27(6):1127–1144

Melgar-Alcantud P, Puigvert L, Ríos O, Duque E (2021) Language of desire: a methodological contribution to overcoming gender violence. Int J Qual Meth 20:160940692110345

Nazareno E, Vidu A, Merodio G, Valls R (2022) Men tackling isolating gender violence to fight against sexual harassment. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(4):1924

Orenstein P (2021) Boys and sex: young men on hook-ups, love, porn, consent and navigating the new masculinity. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=dIe_zQEACAAJ

Padros-Cuxart M, Molina S, Gismero E, Tellado I (2021) Evidence of gender violence negative impact on health as a lever to change adolescents’ attitudes and preferences towards dominant traditional masculinities. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(18):9610

Pillai V, Ghosh M. (2022) Indian female Twitter influencers’ perceptions of trolls. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9(166) https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01172-x

Poell T (2014) Social media and the transformation of activist communication: exploring the social media ecology of the 2010 Toronto G20 protests. Info Commun Soc 17(6):716–731

Puigvert L (2014) Preventive socialization of gender violence moving forward using the communicative methodology of research. Qual Inq 20(7):839–843

Puigvert L, Gelsthorpe L, Soler-Gallart M, Flecha R (2019) Girls’ perceptions of boys with violent attitudes and behaviours, and of sexual attraction. Palgr Commun 5(56)

Pulido CM, Redondo-Sama G, Sordé-Martí T, Flecha R (2018) Social impact in social media: a new method to evaluate the social impact of research. PLOS ONE 13:e0203117

Redondo-Sama G, Díez-Palomar J, Campdepadrós R, Morlà-Folch T (2020) Communicative methodology: contributions to social impact assessment in psychological research. Front Psychol 11:286

Redondo-Sama G, Morlà-Folch T, Burgués A, Amador J, Magaraggia S (2021) Create solidarity networks: dialogs in reddit to overcome depression and suicidal ideation among males. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(22):11927. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211927

Ríos-González O, Ramis-Salas M, Peña-Axt JC, Racionero-Plaza S (2021) Alternative friendships to improve men’s health status. The impact of the new alternative masculinities’ approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(4):2188

Rios-Gonzalez O, Peña Axt, JC, Duque Sanchez E, De Botton Fernández L (2018) The language of ethics and double standards in the affective and sexual socialization of youth. Communicative acts in the family environment as protective or risk factors of intimate partner violence. Front Sociol 19(3)

Roth-Cohen O, Avidar R (2022) A decade of social media in public relations research: A systematic review of published articles in 2010–2020. Publ Relat Rev 48(1):102154

Salceda M, Vidu A, Aubert A, Roca E (2020) Dialogic feminist gatherings: impact of the preventive socialization of gender-based violence on adolescent girls in out-of-home care. Soc Sci 9(8):138

Samarjeet S (2017) Hashtag ideology: practice and politics of alternative ideology. In Political scandal, corruption, and legitimacy in the age of social media. IGI Global:101–122

Soler M, Flecha R (2010) From Austin’s speech acts to communicative acts. Perspectives from Searle, Habermas and CREA. Rev Signos 43:363–375

Soler-Gallart M, Flecha R (2022) Researchers’ perceptions about methodological innovations in research oriented to social impact: citizen evaluation of social impact. Int J Qual Meth 21:160940692110676

Torras-Gómez E, Puigvert L, Aiello E, Khalfaoui A (2020) Our right to the pleasure of falling in love. Front Psychol 10:3068

Trott VA (2022) Gillette: the best a beta can get’: networking hegemonic masculinity in the digital sphere. N Media Soc 24(6):1417–1434

Valls-Carol R, Madrid-Pérez A, Merrill B, Legorburo-Torres T (2021) «Come on! He Has Never Cooked in His Life!» New alternative masculinities putting everything in its place. Front Psychol 12:674675

Villarejo B, López G, Cortés M (2020) The impact of alternative audiovisual products on the socialization of the sexual-affective desires of teenagers. Qual Inquiry 26(8–9):1048–1055

Villarejo-Carballido B, Pulido CM, Zubiri-Esnaola H, Oliver E (2022) Young people’s voices and science for overcoming toxic relationships represented in sex education. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(6):3316

Zheng Y, Yu A (2016) Affordances of social media in collective action: the case of Free Lunch for Children in China. Info Syst J 26:289–313

Zheng R (2020) # NotAllMen and# NotMyPresident: The Limits of Moral Disassociation. EurAmerica 50(4). http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=10213058&AN=147759966&h=dRUcRiT0OWYtBV0CTfdjMx%2FIASagQVGxJwq%2FmYfUCtj7Fc66SOT3RgyfT%2BVQ479wmtcrgJPb1AR1MmJs57ky2w%3D%3D&crl=c

Acknowledgements

This article draws on the knowledge created by the coordinator of the H2020 project ALL-INTERACT: Widening and diversifying citizen engagement in science. This project was selected and funded by the European Commission under Grant Agreement number 872396.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OR-G, EA, EO, AM-P and GL-T contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was performed by OR-G and GL-T. Analysis was performed by GL-T and OR-G. The first draft of the manuscript was written by GL-T and OR-G. AT and BC made the last revisions. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The article has been approved by the CREA ethics committee of the University of Barcelona, which certifies that the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. No data from Twitter or Reddit are literally included in the manuscript.

Informed consent

Participants in the interviews were explained the goal of the study and consented to their participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Table 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rios-Gonzalez, O., Torres, A., Aiello, E. et al. Not all men: the debates in social networks on masculinities and consent. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 67 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02569-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02569-y