Abstract

PhD by publication, a route of attaining a ‘doctorate’, is growing in adoption, yet has not gained universal acceptance. Whilst doctoral students are expected to free range, be independent in their study, and contribute to knowledge, there is a tendency to be schooled or mainly assessed along the lines of positivism and interpretivism. This paper, in part the author’s situational reflexivity and noting Liezel Frick’s “PhD by publication – panacea or paralysis?”, carried out a documentary analysis of academic regulations of 101 universities in the UK, South Africa, Ireland, Australia, and examined the literature for demi-regularities supporting or inhibiting critical realism in doctoral studies. It followed a (multimethod) plural approach. The examination revealed that critical realism is sparse in doctoral studies, and universities do not cohere in nomenclature and ‘form’ of PhD by publication. In filling the ‘free range’ gap, this paper contributes to the ongoing discourse on PhD by publication by introducing the IDADA (‘identify’, ‘define’, ‘analyse’, ‘develop’ and ‘apply’) methodological framework. The framework evolved from the demi-regularities understudied. IDADA is a practical solution-centric, methodological approach to PhD by publication. The paper calls on researchers and practitioners to be open to structured and ‘alternate’ approaches to research whilst ensuring ontological, epistemological, and axiomatic rigour. Researchers need not approach research religiously — as that of a particular paradigm sect; but rather embrace ‘practical adequacy’. Doctoral students should be encouraged to produce research output with more significant impact through interrogation and unearthing phenomena rather than just “observing, outlining and discussing findings” or conforming to ‘writing style’.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The word research is composed of two syllables, re and search … (The ‘re’ and ‘search’ in research [T]ogether form a noun describing a careful, systematic, patient study and investigation in some field of knowledge, undertaken to establish facts or principles.) - Richard M. Grinnell Jr (1993)

In the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (moving to fifth), knowledge economy (Philbeck and Davis, 2019), digital transformation (Salmela et al., 2022) and beyond, the need for knowledge and innovation workers adept at conceptualising and driving knowledge is more apparent and evident. Beyond those, at the spectrum end of knowledge production (Motshoane, 2022, 2), doctoral studies are increasing in higher education (Chong and Johnson, 2022, iv). Across the Australasian, Asia Pacific, Europe, Middle East, Africa, and America, different models and mix of doctoral studies are evolving, with each adapting to the changing knowledge economy and digital transformation landscape. In all of these, the core of doctoral studies remains intact; original research conducted by the candidate and contribution to the body of knowledge (Davies and Rolfe, 2009, 592, Kot and Hendel, 2012, 346, Kubota et al., 2021, 5). Doctoral students are expected to exhibit a high degree of independence and are required to bring their independent thought to bear in their study; conceptualisation, philosophical underpinning, approach, methodology, analyses, contribution to knowledge and others (Evans, 2000, 268, Robins and Kanowski, 2008, 12), even as they engage collaboratively (Billsberry and Cortese, 2023, 124).

Doctoral students would then have to navigate the philosophical (epistemological/methodology approach) terrain and engage within the form of their doctoral studies. The form is largely informed by academic regulations, while philosophical terrain is an open landmine that the doctoral student ought to navigate per their choice. The author faced a similar challenge (form and philosophy) in his earlier PhD study (readers are referred to the conclusion for the author’s situational critical reflexivity). The form and philosophical inclination are now briefly explored.

Liezel Frick: PhD by publication – panacea or paralysis?

There are different forms of undertaking and obtaining a doctorate (see section 2.1: PhD qualification): one of which is ‘PhD by Publication’. Liezel Frick, in her 2019 paper, “PhD by publication – panacea or paralysis?” affirmed that the PhD by publication has gained impetus as a form of doctoral production (Frick, 2019a, 47). She argued that “it is necessary first to consider the nature and purpose of the PhD before determining its form – form follows function”. Frick (2019a, 47) reckoned that “only after determining the function of the PhD does it seem prudent to deliberate on formats that serve the purpose thereof”. She opined that the primary purpose of the PhD is to transform a student into a scholar (Frick, 2019a, 56). Having looked at form and function, Frick expressed that PhD by publication requires pedagogical changes geared towards engaging in publication activities. In concluding her study, Frick made a clarion call in asking, “how do we support students’ ability to contribute to the epistemic scholarly debate?”.

Consequently, this paper revisits Frick’s call for pedagogical support. This paper looks at two aspects of the doctoral study: model in terms of PhD by publication and methodology by putting forward critical realism as a worthy research philosophy.

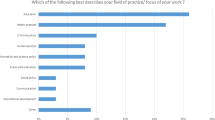

Doctoral approach

One area where doctoral students face challenge having free reign seems to be in (the area of) research philosophy and approach. It is common for doctoral students to defer generally to positivism and interpretivism (Billsberry and Cortese, 2023, 129), which are typically followed by quantitative and qualitative or broadly to ‘mixed-methods’. Where doctoral students adopt other paradigms, tensions might ensue with the supervisor or committee (Chong and Johnson, 2022, 61,128), although not insurmountable. They get entangled in their pre-doctoral exposure, and school/department tradition, among others. Contributory factors might be the supervisor/advisor’s exposure (or partly background), or the school/department’s tradition. Another is prior exposure of the doctoral student during their master’s (Evans, 2000, 268) or research methodology training (Bhattacherjee, 2012). At times, doctoral students in their research planning are faced with “relatively few guides to help translate and understand the application of critical realism” (Martin, 2016, 213). This viewpoint is further supplemented by the researcher’s observation of cohorts of doctoral students across South Africa, Nigeria, and the UK, and cursory search of doctoral pages of universities across South Africa and the UK.

Paper purpose and focus

This paper aims to close the gap of doctoral students’ limited approach to or unwillingness to follow critical realism as the underpinning research philosophy for their study. This paper does so through critical evaluation of the state of PhD by publication and highlighting a practical approach through its IDADA (‘identify’, ‘define’, ‘analyse’, ‘develop’ and ‘apply’) framework (elucidated in Table 2 and conceptualised in Fig. 3 later in this paper): It is a reflection on a PhD by publication journey. The paper contributes to the ‘murky’ waters of methodological ‘how-to’ approach of critical realism in (doctoral) research study (Ackroyd and Karlsson, 2014, 45). It contributes to the discourse on PhD by publication and critical realism.

In one part, it reviewed the academic regulations of 101 universities across the UK, Ireland, South Africa, and Australia. The second part discusses how studies informed by critical realism can add to and fill in the gap in PhD by publication. Although nearly all the academic regulations dictate the ‘form’, they largely mandate the function (nature and purpose) of PhD by publication. They are not prescriptive of which research philosophy must be followed, rather they demand rigour. In practice, however, research ‘philosophical’ approaches are induced by departments, schools, research committees, traditions: though not in all. The ’ideal’ is for the nature of the research enquiry informed by (or informing) the philosophical underpinning.

This paper introduces how critical realism philosophically underpins a doctoral research journey. It also advocates allowing doctoral students to ‘free range’ their philosophical underpinning and approach: At the end of their study, as demanded by academic regulations, it is the students ‘independent’ mind and contribution that are assessed in the thesis examination and the oral viva voce: There is a call for viva voce where it is lacking (Billsberry and Cortese, 2023). This paper also advocates for critical realism as an alternate, (augment as Orlikowski and Baroudi (1991) put it), and not as a replacement for other research philosophies. As alternate especially when explicating ‘deeper’ levels of explanation and understanding (Alkathiri and Olson, 2019, 36) of demi-regularities (Lawson, 1997, 204) and generative mechanisms of sociotechnical structures/interplay. Notably, “critical realism encourages analysis to move from the level of the empirical to the underlying reality, searching for generative mechanisms and structures” (Jordet, 2023, 7).

In summary, IDADA encourages doctoral students to adopt pluralism (multimethod), follow non-linear steps in their research methods, critically engage with reality ontology, re-interrogate epistemic knowledge of existing concepts and push for publishing their research work without the need to pedantically follow the review, methods, finding, discussion dictum. Appropriate methods are used in each phase of the research, and each can be self-containing: the principle is to “let the nature of the phenomena guide the choice of method” (Jordet, 2023, 6). Obviously, this might not be desirable for all research types, such as those strictly following IMRad (Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion) in core experimental natural sciences and medical fields (Cuschieri et al., 2018, Search and Write (Søk and Skriv), 2023). Nonetheless, critical realism through dispositional ontology supposes that ‘another’ philosophy of science is possible (Vandenberghe, 2019): causal mechanisms of experimental conditions (Bhaskar, 2013) and explanatory ‘generative mechanisms’ (Bhaskar, 2009).

By adopting critical realism, this paper does not advocate for ‘doing away with’ other research philosophical approaches. Doctoral students following IDADA or critical realism broadly should embrace the greater flexibility they have in how they can structure their PhD by publication thesis through their publications (Goodwyn, 2018, 16, Chong and Johnson, 2022, 69).

Paper structure

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. PhD qualification models and concerns are discussed, after which the research domain and methodology come next. Thereafter, the finding is presented, followed by scenario applicability to the nature of digital technologies (and IT as a form of digital technology), and from there, the paper concludes.

PhD qualification, concerns on approach and structure towards PhD by publication

This section looks at the PhD qualification, introduces the PhD by publication and the concerns around the PhD by publication.

PhD qualification

In academe parlance, the doctorate or PhD is the highest formal academic qualification that a student can exit a higher education institution with (Cryer and Mertens, 2003, 93, Mirzaei and Mabin, 2013, 1, Makoni and Makoni, 2022, 40). Invariably the ‘highest’ graduate degree awarded by universities (Asfour and Winter, 2018, E660). The post-doctoral after the PhD programme is not a formal academic qualification (Alkathiri and Olson, 2019, 36). Likewise, ‘higher doctorate’ like DSc (Doctor of Science) or DLitt (Doctor of Letters or Literature) are typically not formal academic qualifications either.

The PhD programme is often seen as ‘work’ or research pupillage (McAlpine and Mitra, 2015, 111), akin to apprenticeship (Lundgren-Resenterra and Crosta, 2019, 704, Makoni and Makoni, 2022, 42). Some follow the professional doctorate programme (Billsberry and Cortese, 2023, 132); a formalised and systematised approach to gaining the PhD qualification (Lundgren-Resenterra and Crosta, 2019, 704). In most fields, a PhD is the must-have qualification for proper entry into academia professoriate (Alkathiri and Olson, 2019, 34). This paper acknowledges that some fields allow for other doctorate degrees such as but not limited to Ed.D. (Education Doctorate), Eng. D. (Engineering Doctorate), J.D (Juris Doctor in Law), MD (Medical Doctorate which is distinct from Doctor of Medicine). Though in some parts of Europe, habilitation, a post-doctoral ‘qualification’ is required or mandatory for professorship (Kwiek, 2003, 466, Lienhard, 2019, 158), this is not a formal exit programme.

Robins and Kanowski (2008, 2), outlined five types of PhD qualification routes. These are Tradition PhD (also refers to as PhD by Thesis), PhD by publication, New route PhD, Professional doctorate, and Practice-based doctorate. Their ‘new route’ PhD route (from the UK/Ireland point of view), as it would appear, is North America ‘de-facto’: the PhD training in the UK centres for doctoral training (CDT) is closing inFootnote 1.

PhD by publication

Aside from the traditional “master-apprentice” approach and the structured doctoral programmes (Lundgren-Resenterra and Crosta, 2019, 704), the PhD by publication is a route to gaining PhD qualification from one’s research publications. It is defined in the UK Council for Graduate Education as the PhD awarded “to a candidate whose thesis consists entirely or predominantly of refereed and published articles in journals or books which are already in the public domain” (Davies and Rolfe, 2009, 591–592). Jackson (2013, 556 in quoting Park, 2007, p. 33), on the other hand, described a PhD by publication as an award where the candidate’s thesis is “based largely on the supervised research project, but examined based on a series of peer-reviewed academic papers that have been published or accepted for publication, usually accompanied by an over-arching paper that presents the overall introduction and conclusions”.

The offering of PhD by publication varies from university to university and from region to region: evinced in the 101 universities reviewed in this research (84 in the UK, 7 in Australia, 8 in South Africa and 2 in Ireland). Some offer PhD by publication to the generality of students beyond just their staff (#56 in the reviewed universities). Some offer only to their staff (#16) to shore up ‘staff doctorate’ (Davies and Rolfe, 2009, 591). Some offer to staff and alumni, and some offer to staff, alumni and associates (having some form of affiliation/link to the university: For instance, Northumbria University, University of Leicester, and University of West England Bristol, among many).

Retrospective and prospective route

Davies and Rolfe (2009, 592) suggest that following a prospective route would be beneficial “in addition to the usual retrospective route where candidates submit a portfolio of previously published papers”. The concern is that some students would not want to embark on the PhD by publication if they have not published a priori.

However, because of their work or style, they might be interested in starting on publication during their study, which they would want to be credited towards their doctorate. Readers should note that Jackson (2013, 358) refers to retrospective (Peacock, 2017, 126) as ‘PhD by Prior Publication’ and prospective (Peacock, 2017, 125) as ‘PhD by Publication’Footnote 2. A not-so-distinct type identified by Jackson is termed ‘Hybrid PhD by Publication’, which is a combination of the two programmes (for instance, as of 2022, University of Johannesburg South Africa, Coventry University, Manchester Metropolitan University, University of West England Bristol, the University of Strathclyde in the UK offered ‘Hybrid’ in one form or the other).

This paper loosely uses the three terms (retrospective, prospective, hybrid): Where need be, emphasis is made. The methodological approach suggested in this paper is geared towards assisting students in prospective and hybrid PhD by publication, and is highly helpful for ‘self-studying’ researchers embarking on the retrospective route. By way of distinction, the retrospective is when the research papers (or works) are published following peer review prior to the tenancy of the PhD programme. One (or maybe two) additional published paper(s) might be accommodated post enrolment; however, some universities might allow this only in hybrid. Prospective, on the other hand, entails publishing research outputs during candidature. In some instances, one (or two) previously published might be allowed if motivated: (this ordinarily would fall under hybrid, though).

Query on academic level validity and rigour

There is no universal acceptance of PhD by publication. Indeed as Dowling et al. (2012, 295) put it, “acceptance of the PhD by publication is far from universal; many supervisors remain sceptical and some examiners continue to query the validity of it”. Concerns of rigour and validity are also those of academic level. Davies and Rolfe (2009, 592) clearly acknowledged that “the question of academic level needs to be addressed if the PhD by publication is to gain wider acceptance”. More so, when noting that the “PhD by Publication format is often treated with suspicion in disciplines and countries where it is not widely adopted, some harbouring concerns regarding the credibility of this format” (O’Keeffe, 2019, 2). This paper flowing from its documentary analysis (of academic regulations), asserts that the reviewed universities (84 in the UK, 7 in Australia, 8 in South Africa and 2 in Ireland) were equivocal in their admission criteria and examination assessment rigour. Consequentially, concerns about academic level and rigour ought to fall away.

Stepping back and looking afar, it would appear that scepticisms about PhD by publication validity, rigour and acceptance revolve around nature, purpose, form, and function (Robins and Kanowski, 2008). Therefore, processes, frameworks, guidelines, and policies on approaching and improving its structure and function would go a long way in addressing perceived academic rigour concerns (Davies and Rolfe, 2009, Frick, 2019a).

This paper summarises this section with the conceptual view in Fig. 1; a summary of a doctorate’s form, function, and nature. The critical realism-based solution-centric approach postulated in this paper’s second part seeks to assist with quality and doctoral students ‘free range’ methodological determination.

As Frick (2019a, 52) has noted, a “PhD by publication requires a pedagogy that supports the publication of doctoral work”. Inherently, PhD by publication is anchored on the ‘bundled’ publications as an ‘examinable’ thesis. The concerns around the peer-review process and the entropy of predatory journals can be managed by improving structures and functions around ‘publication outlets’ (Jackson, 2013, 362).

Further studies on structures and processes of PhD by publication are required from the preceding concerns. Apart from institutional academic regulations, policies and guidelines (Robins and Kanowski, 2008, Davies and Rolfe, 2009, Jackson, 2013, Frick, 2019a), there is a need to point the beam-light on methodological approaches that aid PhD by publication.

Research domain and methodology

From the preceding section, it became apparent that PhD by publication entails writing, submitting, and collating accepted and/or published publications (which can be journal articles, books, book chapters to mention but a few, and in some instances, conference papers included in proceedings). The doctoral study, irrespective of the route, entails conceptualising and learning the art of research, including methodology (Jackson, 2013, 357) and writing skills (Robins and Kanowski, 2008, 8).

Research paradigm and philosophy

While methodological approach and rigour remain fundamental to research (Dowling et al., 2012, Jackson, 2013, Saunders et al., 2019a), the research landscape is changing (O’Keeffe, 2019, 11).

Religiosity of research paradigm

Researches are no longer approached religiously – as that of a particular (cast in stone) paradigm sect. Instead, practical solution–centric approach(es) is/are taken by researchers (Kahn et al., 2012, 56) whilst adhering to the principles of ontology, epistemology, axiology and rigour. What is critical is the appropriateness and suitability of research philosophical approaches and not fixation on ‘a’ philosophy. Hence, it is not about positivism, interpretivism, critical realism or any other, but what lends itself to the research at hand.

Critical realism

Going by the observation of the researcher and cursory view of graduate schools programmes and websites, many doctoral students are schooled in positivism and interpretivism (Alkathiri and Olson, 2019, 36); nonetheless, doctoral students are free and expected to be free range in their study (Evans, 2000, 268) and contributing to knowledge (Robins and Kanowski, 2008, 12). The other ‘within bound’ ascribed to most doctoral students are quantitative and qualitative with a degree of freedom exercised as mixed-method (Dowling et al., 2012, 295, Ivankova and Plano Clark, 2018, 409). These schooling and approaches are typical but not exhaustive nor cast in stone as the gospel truth.

Critical realism has earned its place as a research principle alongside positivism and interpretivism (Bhaskar, 2016, Alkathiri and Olson, 2019). Rather than tilting towards quantitative or qualitative, critical realism advocates plurality of methods – multimethod (Mingers, 2001, Wynn and Williams, 2012, Adesemowo, 2019, 405) based on the deep-rooted necessity of need. Critical realism also acknowledges the multifinality (Chatterjee et al., 2021, 564) of material, and structures, and the generative mechanisms they cause or the phenomenon we observe. In doing so, critical realism affirmed that there is more than one plausible underlying cause for which we must unearth the most plausible (Bhaskar, 2016, Pilkienė et al., 2018).

Although critical realism has gone mainstream, with accompanying research strategies, processes and scripts taking shape, it has yet to take flight amongst doctoral students as the go-to or preferred research approach. This, nonetheless, the existence of a frontline journal dedicated to critical realism (Journal of critical realism, ISSN 1476-7430) and tier A journals devoting special issues to critical realism (for instance, MIS Quarterly issue 3, 2013, EJISDC issues 6, 2018). Yet, it would appear that critical realism is relatively few and far between in doctoral studies: evinced in the literature search in academic databases.

At the risk of detailing what critical realism is, which this paper avoids, critical realism resonates well with the doctoral study: readers are referred to critical realism concepts and reference papers outlined in Table 2. Critical realism, through its (real, actual and empirical) stratified ontology (Fletcher, 2017, Fig. 1, Shi, 2019, 2), meta-theory (Hoddy, 2019, 112), and causal generative mechanism (Shi, 2019, 4), is geared towards re-examining/re-interrogating research realities to gain ‘deeper’ knowledge. Alongside the ‘retroduction’ process, critical realism enables developing a new frontier of knowledge on already held knowledge (Boughey and Niven, 2012, 642, Clegg, 2012, 674, Adesemowo, 2019, 405, Alkathiri and Olson, 2019, 36). In explaining reality, the unseen need not be seen (Yu-cheng, 2022, 7) in order to explicate the ‘power’ or generative mechanisms or capabilities they exert.

Research rationale

The paper aims to study these gaps in academic regulations and literature, and contribute to forms and processes of facilitating critical realism in doctoral study, and to the call for ‘how-to’ of engaging critical realism. The paper focuses on information systems (a cross-domain, interdisciplinary area of study). The subject matter is broadly digital technologies, which are ubiquitous in use and pervasive in organisations and with a focus on the materiality of IT assets (as a form of digital technology). From the demi-regularities (‘partial’ regularities, causal patterns, ‘nuances’ from the ontological and epistemological study) and example scenario-play, the paper outlines a conceptual guide, using a non-linear stepwise approach, suitable for PhD for publication. Therefore, the objective of this research project is:

to propose a methodological framework that supports PhD by publication doctoral students where reality(ies) are investigated and re-interrogated.

The following sub-objectives assist in achieving this objective:

-

To understudy the concept of PhD by publication;

-

carry out a scoping review of critical realism in doctoral study (in doctoral journals);

-

interrogate the nature/nuances of critical realism in doctoral study (in doctoral journals);

-

conceptualise a supportive methodological framework for PhD for publication

Given the aim and objective, the question is, how does critical realism facilitate PhD by publication and what practical methodological framework avails to doctoral students?

Methodological approach

Flowing from the aim of this research, an exploratory and investigative approach was taken to explain the PhD by publication phenomena; Fig. 2 shows the overarching pictorial view of the methodology approach for this paper (and is also the reference approach for the publications contributing to the IDADA methodological framework introduced later in this paper).

The methodological approach is flexible and reusable: it is good approach for doctoral students to employ in the sections of their methodology and elements of their methods. The approach is divided into four pillars of research methodology; drawing from Saunders et al. (2019a), research onion.

First, the research philosophy sets the tone that underpins the research study, and the direction that the research takes. The second is the mindset approach towards the conduct of the research and analysis of the findings. The third is the strategic approach that houses the methods of data collection that are followed in the fourth.

Research philosophy and approach pillars

Underpinned by (late) Roy Bhaskar’s critical realismFootnote 3 principle (see earlier section), this paper follows a multimethod methodological approach (Mingers and Brocklesby, 1997). Multimethod, in similitude to mixed-method, uses a variety of quantitative or qualitative approaches/methods. However, unlike mixed-method, multimethod uses the most suitable, intra or inter, without necessarily combining or integrating methods (Ivankova and Plano Clark, 2018). With mixed-method, combining is inherent. In essence, plurality in multimethod is focussed on appropriateness and ‘multiple operationalism’ rather than ‘mixed operationalism’ of approaches or methods (Johnson et al., 2007, 114). Often, multimethod gets conflated with mixed-method (Hesse-Biber, 2015 cited in Ivankova and Plano Clark, 2018, 410), especially from a philosophical standpoint (Ivankova and Plano Clark, 2018, 417).

Research strategy and methods pillars

Beyond the philosophical underpinning, approach to theory and methodological choices, a strategic approach is required for what to do and how to understand what to investigate (Saunders et al., 2019b, 131). The strategic goal is to triangulate findings anchored in exploratory enquiry (from a narrative viewpoint) and logically reasoned through (that is argumentation). In this instance, narratives are geared towards gaining practical meaning of content and contexts (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2015, Saunders et al., 2019a).

Consequentially, an exploratory scooping literature review was carried out (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005, Levac et al., 2010) alongside documentary analysis; both informed by narrative enquiry (Mesgari and Okoli, 2019, Saunders et al., 2019a). Python-based Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques assist with enquiry and analysis.

The review and analysis were done alongside logical reasoning/argumentation (Archer et al., 2013, Walton, 2013). The case of IT assets as a form of digital technology was explored (scenario play also using elements of a priori semi-structured interview), and partly drawn from the author’s autoethnography (Chang, 2016, 43). The execution was anchored on an internet-enabled platform (Ruhode, 2013).

Data source and analysis

The two main data sources are documentary (academic regulations and policies) and literature.

Documentary data: They were painstakingly sourced from university webpages across the countries in focus (UK, Ireland, South Africa, and Australia) and where not readily available, an extensive search was done using the synonymous references for PhD for publication in endnote 2.

Literature data: The search for literature is discussed in the section “Search for critical realism in doctoral studies”.

Being underpinned by critical realism, the ‘textual’ analysis tilts largely towards narrative (Kim, 2016, 190) and discourse analysis (Hardy et al. 2004, Sitz, 2008) with elements of content analysis without the ‘counting’. The discourse in this context is more of critical discourse analysis (Saunders et al., 2019b, 678,680) and ‘perception of a phenomena’ (Leung and Chung, 2019, 828). For instance, the researcher explored the ‘meaning’ and ‘context’ of PhD by publication and critical commentary document. The literature ‘review’ follows a narrative review (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2015). Analysis was carried out through visual and interpretive reading of the researcher and leveraging NLP (Li et al., 2021).

Findings and discussion

The exploratory process and the explanatory critical review are presented in this section.

Search for critical realism in doctoral studies

Web of Science (WoS) and Google Scholar (GS) were used to identify publications on doctoral studies using or focusing on critical realism. WoS and GS was ‘purposeful’ –because WoS provides a database of credible papers, while GS has extensive reach (López-Cózar et al., 2017, Gusenbauer, 2019). The choice is also because WoS and GS, combined, have the depth and reach required, although there are hosts of other academic databases, such as EBSCO, Scopus, ProQuest and others (Schryen, 2015, 299). An additional (control) search was carried out in Scopus.

The search through WoS and GS was done with a combination of keywords (search terms), in line with scoping study (Levac et al., 2010, 3, Schryen, 2015, 299). Readers are referred to Table A3 in the Appendix (supplementary) for the search summary in WoS and GS. Results that were not focusing on critical realism in doctoral studies were discarded, as well as those that were duplicates. Reference lists of the pertinent papers were also searched, resulting in twenty-nine papers. A second reading through the papers was done; after that, the streamlined search yielded the selected twenty papers reflecting critical realism.

From the more expansive Google Scholar, the following was observed. In the International Journal of Social Research Methodology, out of about 230 articles discussing doctoral (studies), only 22 dwelt on realism and just eight (08) focused on critical realism. Out of about 49 articles in Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, only one was selected as engaging on critical realism. In the same vein, three articles were deemed to have foci on realism and doctoral (studies) out of 66 papers returned for realism or doctoral in International Journal for Researcher Development. The trend continues in Studies in Higher Education, and in Higher Education Research and Development, with 03 and 05 articles from 807 and 434, respectively. In essence, critical realism is sparse in doctoral studies. A controlled search in Scopus yielded only two articles; it is noted that Scopus was limited to TITLE-ABS-KEY.

An exception to the trend of search results is regarding two articles of interest from Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education journal in WoS (“realism” OR “doctoral”), whereas they were missing in GS.

From analytical (content) reasoning, it became apparent that critical realism is upheld as a philosophy of science that takes meta-theory (Hoddy, 2019, 112) into account and is geared towards re-interrogating research realities and developing a new frontier of knowledge on already held knowledge.

Re-interrogating nuances in critical realism-based doctoral studies

Although now entrenched as a research philosophy (Bhaskar, 2016, Alkathiri and Olson, 2019), critical realism still does not offer or prescribe a clear research methodology for data collection methods (Peter and Park, 2018, 66). This non-prescription is attributable to critical realism favouring plurality (multimethod) and not being descriptive on methods, while being explicit on the research process: description (informed by its philosophy), analytical (phenomena), re-describe (abduction/retroduction), concretisation/contextualisation.

Nonetheless the use and the suitability of critical realism to doctoral studies, not much guidance is available to (doctoral) students starting on critical realism regarding ‘methods’ or experimental design (Martin, 2016, 213): also partly to the ‘nature’ of critical realism (Roy Bhaskar’s foreword in Edwards et al., 2014). Studies, such as the research project in this paper, on the nexus between the critical realism research process and (data gathering) methods, are essential to guiding/assisting doctoral students in aligning with critical realism and having comfort in using methods that conform to critical realism principles. Although there are no set rules nor congruity on the amount and type of publications, some concepts are evolving as outlined in Table 1: Number, type, elapsed time, and the nature of the publication.

Towards a practical methodological approach to doctoral study

From the documentary analysis, universities would normally stipulate the number or range of publications required or the ‘quality’ of the publication (publishing venue). Beyond those, most universities do not prescribe the nature of publication or the methodology for published papers. Doctoral students are at liberty to determine their research’s philosophical underpinning and their methods. Critical realism provides a platform for (re)-interrogating known phenomena or unearthing (generative) mechanisms that are at play.

It is important to pause briefly. Let us for a moment take a simplicist critical realism look at the concept of PhD by publication. It is a reality whether it is followed by a student or not. Invariably, a PhD by publication exists in the real domain (of critical realism). In the actual domain, when ‘engaged’ by a doctoral student, a PhD by publication provides a ‘means’ of gaining a doctorate (an outcome it affords). Also, two modes are afforded: the prospective and retrospective routes. The format (form) and functions are interacted with at the empirical domain level. Critical realism allows for this ontological view. If one is to interrogate this stratified reality and its engagement with other structures and agencies, critical realism causes one to explore causal-mechanism for explanations instead of cause-and-effect relationships.

To facilitate explanatory causal mechanism, critical realism offers concepts founded in research. These (concepts), drawing from the identified nuances/demi-regularities arising from narrative re-interrogation of literature, documentary analysis and reflexivity of the author are collated in Table 2. The concepts, viewpoints, and references in Table 2, which found expression in the IDADA framework (See Fig. 3), provide a referential point for doctoral students in evaluating their research and multiple streams of papers. Equally important is that Table 2 brings together viewpoints and positions from various authors.

(IDADA – Identify, Define, Analyse, Develop and Apply – is underpinned by critical realism. The five phases are non-linear. Validation can take place within each phase or across multiple phases or all the phases. A theory assists in ‘shaping’ a phase or multiple phases (theory-laden); however, theories are not mandated neither must theories validate the research (theory-determined). Likewise, focus is on causal mechanisms rather than cause-and-effect).

The IDADA methodological framework

Part of the challenges identified with PhD by publication is the confidence, opportunity, and space to generate publishable results and to publish papers (Dowling et al., 2012, Jackson, 2013). Critical realism offers a means of moving from “surface” to “depth”, interrogating the depth, moving back to the surface to observe, and then ‘back and fro’ in identifying generative mechanisms and emergence towards emancipatory outcomes (Robins and Kanowski, 2008, 66). For a successful outcome of a PhD by publication and publications (for the degree), critical realism offers a process constrained and guided by its philosophy and allows for choices of approaches in executing activities of the processes.

The other challenge, which ironically is also the strength of critical realism, is that critical realism is not prescriptive of methods. As a meta-theory, critical realism provides an ontological reality to gain epistemological knowledge. Research students in their training in research methods and data collection, relate well when the methods are shown how they relate to and are used within a research philosophical paradigm.

This paper’s ‘identify’, ‘define’, ‘analyse’, ‘develop’ and ‘apply’ (IDADA) methodology (Fig. 3) is a bold attempt at contributing to a practical approach to embracing critical realism (Dobson, 2001, Hoddy, 2019).

Being exploratory and with a focus on explanatory, non-linear stepwise approaches are recommended in this paper, as evinced in Fig. 3. Though distinct, they are not linear. They offer a practical, pragmatic approach to carrying out research work, continually in touch with literature and iteratively engaging in chunks until the research project reaches a saturation exit point.

Scenario: IDADA methodological framework through the lens of the case of digital technologies and IT assets as a form of digital technology

Up to this point, PhD by publication has been discussed, highlighting and re-interrogating its mechanisms. Demi-regularities were extracted, and these informed the construct of the ‘identify’, ‘define’, ‘analyse’, ‘develop’ and ‘apply’ (IDADA) methodology.

This section steps through IDADA methodological framework’s application, through the eyes of the author, as it shaped research into the materiality of digital technologies and the nature of IT assets as a form of digital technology.

When prescribing a methodological framework, care must be taken to guard against being descriptive or overly restrictive. With this hindsight, and taking note of Saunders et al. research onion (Saunders et al., 2019a, fig. 4.1), IDADA proffers a critical realism-based methodological framework that should free up a researcher (especially one embarking on PhD as publication) from prescriptive research methods. Yet, offering indicators that should guide research strategy and methods. A word of caution, though: doctoral students (and researchers at large) should not jump on a philosophy wagon, such as critical realism, for the sake of it. Research philosophy is not disjointed from the nature, topic, and content of what is being investigated, re-examined or evaluated.

The identified five phases of IDADA are non-linear. Validation takes place within and across each phase and is grounded in literature. The design (which is the expectation) is that attempts would be made to publish at least a contribution to knowledge during each phase and as myriad. Further validation occurs through research output dissemination, especially the research publication process.

By enumerating the five phases of IDADA in the following sub-sections, doctoral students are provided with an exemplar of how IDADA was engaged and pointers to how IDADA could be engaged.

IT assets as a digital technology ‘artefact’

The research under study is a research project that broadly re-interrogates the materiality of digital technologies and critically re-examines the structures and mechanisms of IT assets to gain better insight into the nature of digital technologies. This re-examination also aims to contribute to the ongoing discourse of theorisation of digital technology and IT artefacts in the Information System (IS) discipline.

Within IS, researchers have been calling for ‘within discipline’ theorising of IS/IT (Orlikowski and Iacono, 2001, Grover and Lyytinen, 2015) and digital technologies or digital ‘X’ (Salmela et al., 2022), rather than just reliance on mid-range and reference theories (Grover and Lyytinen, 2015). It is not a call to discard away with mid-range and reference theories. It is a clarion call to engage the core of the IS field in itself. Research is developing in this regard of theorising IS/IT artefact (Alter, 2017, Adesemowo, 2019, Bennett et al., 2019, Faulkner and Runde, 2019) and digital technologies (Rodriguez and Piccoli, 2018, Baskerville et al., 2020, Salmela et al., 2022). Going by Alter’s (2017, 675) ‘conceptual artefact’, which loosely translates to ‘knowledge that is abstract’, conceptual artefact also refers to theories, designs, frameworks, and purposeful created (material and non-material) objects.

Identify

IT assets as artefacts are well known within IS. They are also well known as assets. However, there is no coherence with their identification, valuation and addressing risk facing IT assets or risk they introduce. As a phenomenon, IT assets (and now broadly digital technologies) are ubiquitous yet ‘unknown’: A contradictory contradiction, one might say. Consequentially, critical realism becomes a suitable research philosophy to engage the nature of IT assets (and materiality of digital technologies) as critical realism is apt for re-interrogating phenomena or realities that are well-known, yet ‘not understood’ or understanding does not cohere (Goodwyn, 2018, 55). This is because critical realism by its nature, inherently provides for probing and unearthing realities, structures, agencies, and (generative) mechanisms. More so, critical realism is deep in ontology exploration, given its view of reality as structured, differentiated and changing (Hoddy, 2019, 112). Scoping study (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005, Levac et al., 2010) was assistive, especially when it follows the rigour of PRISMA-ScR (Tricco et al., 2018). Equally so is moving away from ‘evidence-centric’ review to explanation through narrative reviews (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2015). A narrative approach is apt for identifying, describing, and abstracting (Hu, 2018, 125) the elements of the phenomena, realities, structures and mechanisms under study. It is a strong foundation of the DREI retroduction methodology (Mingers et al., 2013, 797) that weaves through the other phases.

Define

Whilst IT assets/digital technologies are phenomena on their own, they express themselves as a stream of phenomena from different lenses of (materiality) engagement, identification, valuation, risk, operation, lifecycle, and domain of use. These define the different ontologies of realities at play and inform the multi-faceted research questions. In the case of information assets research, a phenomenon aspect of IT assets was redefined and published (Adesemowo et al., 2016); this commenced from an identified problem of discarding IT assets (Adesemowo and Thomson, 2013). The structures, codified and identified, contribute largely to an ontological classification system that was conceptualised (Adesemowo et al., 2017). Any of or mix, but not limited to, scoping study, logical reasoning, argumentation, coding, focus group, and survey can be used. The phenomenon or reality is concretised sufficiently enough to be engaged uniquely in the ’define’ phase. Sufficiently enough to identify agencies, structures, and mechanisms at play with the (social or material) phenomenon or reality. Sufficiently enough to describe the structures, events and mechanisms for analysis and identifying the ‘correct’ generative mechanisms or emergence at the later stage.

Analyse

Analysis of demi-regularities flows from iterations of identification and defining. To gain a deeper understanding of demi-regularities at play (Lawson, 1997, 204, Ackroyd and Karlsson, 2014, 29), elements, mechanisms, and structures were exploratorily interrogated. Interrogation, whilst being theory-guided, is not necessarily defined by theory. For example, the use of institutional or dynamic capability theory, a type IV Gregor theory (Alter, 2017, 674), from a critical realism point of view is not so much of affirming presence or absence of the data to corroborate theory (El-Gazzar, 2016, 51), but rather gaining insight into and explaining the nature of phenomena and/or realities under investigation as was the case with IT assets/digital technologies. This, (theory guiding but not theory defining), allows pre-existing theories to be engaged and as needed, redeveloped or extended. Thus becomes more theory-laden (Fletcher, 2017, 2) towards theory-building rather than theory-determined (Fletcher, 2017, 4, Hoddy, 2019, 113) of cause-effect proving.

An aspect of ‘cause-effect’ often glossed over, or that is not given sufficient attention in critical realism, is quantitative and statistical analysis. There seems to be an unfolded belief that critical realism is all but quantitative. While qualitative holds sway (Olsen, 2010, Fig. 1), critical realism welcome quantitative approaches (Mingers et al., 2013, Ackroyd and Karlsson, 2014). This paper did not go in-depth in order to remain focused on its discourse on PhD by publication. In brief, critical realism takes a structural view of statistical analysis. For instance, ‘demi-regularities’ can be extracted from data tables, latent factors implicitly measured in data sets (Olsen, 2010), or perhaps exploratory analysis derived from PLS-SEM (partial least square – structural equation model). Of importance to critical realism is ‘practical adequacy’; for quantitative, this requires explanatory analysis of quantitative data. Closely knit is that rather than deterministic, the focus shifts to ‘transfactual’ effects, implying that they are enduring not transitory (Olsen, 2010, Archer et al., 2013), essentially facts within context. In essence, one goes beyond descriptive statistics to situated narrative and describing the context of generative mechanisms (Mingers et al., 2013, Ackroyd and Karlsson, 2014).

Develop

With the insight gained, conceptual artefacts, theories, and models are developed, or existing ones are redefined or extended. Faulkner and Runde (2013, 2019) redefined the concept of IT artefact from technological objects to digital objects, whilst Bennett et al. (2019) extended the dynamic form of matter to digital technologies. Flowing from the re-examining and explication, a discordant definition for information assets was highlighted, a lens and re-definition was developed and published (Adesemowo et al., 2016). A structure and mechanism ontology (for IT assets and risk) was developed and published (Adesemowo et al., 2017), and a re-definition for IT assets as a form of digital technology was proposed (Adesemowo, 2021). The IDADA framework proposed in this paper also emanates from the approach to studying the nature of IT assets and digital technologies (Adesemowo, 2019), proposing a framework for digital development through explanatory investigation of the materiality of digital technologies (Adesemowo, 2020), and the ongoing study of explicating (materiality of) digital technologies.

Apply

An essential part of IDADA is delineating an area of application/study or focus areas. Identifying a domain of use or the domains of use is instructive in guiding the other phases of identify, define, analyse and develop. The benefit accrues when engaging across domains of use; researchers are clear on the phenomena, the ontology of reality(ies), mechanisms, and emergence that are at play without conflating or clouding up issues. Clarifying the domain(s) of use is also of the essence in the validation process. For instance, in the IT assets and risk ontology, the identified use domain was instrumental in validating the developed ontology. Different methods are possible, including scenario, case, evaluation, reflexivity, and auto-ethnography.

The ‘apply’ phase is not left to the last. It is iteratively engaged alongside the other four phases. The applicable domain is identified at the onset and refined as the research progressed. In some research, new or innovative areas emerge, and they are explored, putting a pause on the ‘original’ area or switching away. For instance, a domain of use evinced in the author’s collaboration on a fuzzy approach to information assets’ classification (Alonge et al., 2020). Delineating and focusing are critical for research outcomes, otherwise, the research will be fluffy, being all over the place. It is not uncommon to have manuscripts rejected for lack of ‘focus’ or viva voce failed for lack of ‘defined area’.

Conclusion

This paper concludes with the author’s reflexivity, a recap of IDADA as an approach to critical realism in doctoral studies, its limitations and the way forward.

The author recalled that during his earlier PhD programme, he had published a journal paper and book chapters and had three manuscripts prepared (two of which were submitted for review). There were two supervisors (promoters). The author was hopeful of proceeding to ‘collate’ the published papers and the draughted manuscripts cohesively as his thesis. The author had thought there was an understanding that the chapters of his thesis would follow what was mapped out, along the line of publications lined up. That is from traditional thesis to thesis by articles. It was a rude shock when one of the supervisors said in no uncertain terms that “irrespective of how many papers might have been published and would be published, I hope you are aware that you have to write the chapters of the thesis according to the (traditional) thesis format”. This negates the whole critical realism-based approach for the research projects.

Excruciatingly challenging to have one literature review chapter for the whole research project, another for methodology, and yet another for experimental design et al. Jackson (2013, 365) cautioned against leaving doctoral candidates at the mercy of divergent interpretations of supervisory. Robins and Kanowski’s (2008) earlier caution on student-supervisor cohering a priori on PhD by publication formalities, processes, and strategy is evident and reinforced. Documentary analysis of academic regulations, code of practice and guidance evinced that most (of the universities reviewed) now made it clear when publications can be included. Some dictate at the point of enrolment/registration, some during candidature, and some at the point of submission based on formal supplication/plea or ‘nod’ of the supervisor (Kubota et al., 2021).

Frick (2019a, 52) called for a ‘different’ doctoral pedagogy. Supervisors are enjoined to be open, articulate and hands-on (Billsberry and Cortese, 2023, 128). IDADA, in this regard, provides a process that supports a structured and non-linear piecemeal approach to generating a collection of papers, and provides for theorising philosophy, and in-depth explanatory and narrative review of literature. IDADA also advocates analysing and discussing empirical papers through plurality of methodological approaches, alongside conceptualising and applying findings to domains (Jackson, 2013, 362). IDADA, through the non-linear processes and explanatory nature of critical realism, provides for ‘gelling’ together. The golden thread or coherence challenge raised about PhD by publication gets well attended to (Davies and Rolfe, 2009, 592, Merga et al., 2019, 3).

IDADA as an approach to critical realism in doctoral studies

Doctoral students, especially those pursuing PhD by publication, must be bold in their plurality of data collection and analysis methods. In so doing, they must be firm and concise in deriving their research methods from critical realism-based strategies. They must ensure their methods are undoubtedly informed and grounded in critical realism. The overarching consideration is critical realism’s philosophy ontologically, epistemologically, and axiomatically guiding and shaping their research.

This paper posits that IDADA provides a multimethod research framework for doctoral students pursuing PhD by publication (and researchers at large), exploring critical realism in interrogating the structure and nature of phenomena and realities. Apart from leveraging the principles of IDADA as a critical realism approach in their publications, a key area that critical realism should be espoused, is in the introductory or critical commentary/exegesis. This is the document that explicates the golden thread of the ‘collated’ publications and the ‘practical adequacy’ thereof (Goodwyn, 2018, 15). It is what would be examined along with viva voce (in places where oral takes place).

Whilst it is noted that this paper is situated in the information systems domain, it finds applicability in other research areas subscribing to critical realism, including social sciences and humanities. More so, information systems cuts across related and reference fields of psychology, information science, economics, development studies, sociology, anthropology et al. (Grover and Lyytinen, 2015, 272, Walsham, 2017, 25, 31).

Artefact in PhD by publication (inclusive of prior work or practice)

Given that a significant number of the universities reviewed, allow for ‘artefact’ (typically in documentary, novel, sculpture, architecture, landscape, visual arts, film, music, multimedia), it is left to be seen how websites or artefactFootnote 4 (in information systems) would be handled, were they to be pursued as the ‘practice-based’ research. Intuitively, design science might be a research paradigm of choice, or a general drift towards process and artefact evaluation. Moreover, the collated published works are (in themselves) a form of artefact when situated within the context of the critical analysis for the PhD for publication. If so (for research artefact, published works artefact), critical realism through its ontology (and epistemology) is apt (Carlsson, 2006, 2011, Uppström, 2017). Critical realism provides a suitable philosophical platform of engagement to guide: on one part, the research artefact (engaged within the research) and, on the other hand, to guide the critical retrospective evaluation of the published articles (as artefacts that are ontologically situated). More so, critical realism axiology is rooted in ‘transformatory’ and emancipatory ethos. From a critical realism perspective, emancipatory goes beyond the ‘act’ of ‘visible’ emancipation. As Goodwyn (2018, 58) puts it, “critical realism argues that meaning-making is evaluative in looking for what matters, for what is meaningful to humans, for what offers us a developmental opportunity, this can be called ‘emancipatory’.”

Embracing critical realism

Nonetheless the differing view of ‘theory’ (practice, world view, testable propositions, ‘model’), theories are important, pervasive and indispensable to research (Gregor, 2006, Ramson, 2016, Alter, 2017, Siponen and Klaavuniemi, 2019); more so a pivotal aspect of doctoral research (Ramson, 2016, 1). Yet, crucial to ‘why research’ is philosophy (Holden and Lynch, 2004, 407). Philosophical position/underpinning critically impact the ‘what and why’ of research: for instance, methodological approach might be restricted/inappropriate based on philosophical position. Critical realism, through its stratified (realist) ontology of empirical, actual and real (deep), enables a philosophical stance beyond our ‘knowledge’ or conscious experience (Leonardi, 2013, 68). Through its inclination to pluralism (appropriateness of methodological choices), it affords investigating subjective and objective domains of reality.

A critical realist theory’s explanatory power lies in identifying generative mechanisms that explain how and why events occur in a given context (Shi, 2019, 4). Critical realism should be embraced when identifying, discovering, uncovering (and in more engaged, participatory research, testing the limits of) structures, blocks, and (generically) causes in open systems within a context, and the particular sequences, combinations, and articulations of them at work in specific times and places (Roy Bhaskar Foreword in Edwards et al., 2014): in essence, critical realism is geared towards discovery, understanding, examining/re-investigating (per its causal explanatory), and transformative change (per its emancipatory ethos).

In their reflection on their doctoral studies, Peter and Park (2018, 65) concluded that critical realism offers an alternative to “engage meaningfully in studies that examine perceived realities at the empirical level and the causal mechanisms that lie behind them.” This was evidenced in Ononiwu’s (2015) doctoral study, where he unearthed generative mechanisms in adaptive e-financial information systems that he encapsulated into an explanatory Technology Emergent Usage Model (TEUM). Peter and Park’s reflection and Ononiwu’s thesis affirmed that critical realism explanatory power evinced in the identification of generative mechanisms that explain how and why events occur in a given context” (Shi, 2019, 4), including fluid and complex entities/interactions (Thorpe, 2020, 35).

Two other exemplars of embracing critical realism are conceptualisation and emancipatory practical adequacy. Vulchanov’s (2022) doctorate, in demonstrating the explanatory power of critical realism, also examined contextual mechanisms of the social and interpersonal role of language that was conceptualised in the doctoral study. Still on English, Goodwyn (2018) brought to the fore the real, actual and empirical domain of the ‘art of teaching English’, the classroom and the students. His critical overview (of his published papers) for his PhD by publication thesis affirmed critical realism’s pluralism principle in what he termed ‘practical adequacy’ of using the most appropriate approach and methods (Goodwyn, 2018, 15). Goodwyn’s critical overview also espoused and highlighted the emancipatory ethos of critical realism. By emancipatory, a ‘real/actual’ emancipation need not have taken place; providing clarity, meaning, contextual understanding, or a platform of engaging, or facilitating the conditions/contexts or possibilities for change might suffice (Houston, 2010). As Goodwyn (2018, 56) puts it, in critical realism, “meaning making is evaluative in looking for what matters, for what is meaningful to humans, for what offers us a developmental opportunity, this can be called ‘emancipatory’”.

Limitations and the way forward

A limitation of this research might be the choice of ‘search terms’ and the use of Web of Science and Google Scholar as the primary source of literature for the scoping study. However, great care was taken to follow up on the references in pertinent research papers through purposeful follow-up and reverse citation search (Larsen et al., 2019). Web of Science and Google Scholar provide a blend of credibility and depth of search. Although the choice of publication outlet (based on the search term) might be a limitation, this did not impact negatively: the selected journals are frontline journals covering issues of doctoral study (Peacock, 2017, 126, Grover et al., 2019, 161).

Clearly, there is room for refinement and adaption of IDADA. I call for healthy debate and further engagement by scholars (doctoral students, supervisors, including policymakers) on the forms, processes, and approaches of using critical realism in PhD for publication (and research generally). Researchers are called upon to re-interrogate accompanying critical commentaries/exegeses from critical realism lenses: ontology, epistemology, axiology, multimethod and multifinality. Future research would explore the longitudinal study of place and the role of critical realism on impact and process in PhD by publication; in the field of information systems and cross-domain, and interdisciplinary fields.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The datasets generated for the university’s documentary analysis for the current study are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RDAJUV.

Notes

See archived EPSRC students’ centre: https://web.archive.org/web/20110818004539/http://www.epsrc.ac.uk/funding/students/centres/Pages/default.aspx

This paper through its critical documentary analysis identified various references to retrospective:

PhD by Published Work(s), PhD by Prior Publication, PhD by Publication being the common ones, and a host of PhD by Existing Published Works, PhD by Publication (Retrospective), PhD based on Published Work, PhD on the basis of Prior Published Works, Public Works PhD, Doctorate by Published works, PhD by Previous Published Works, DPhil by Publication, Doctor by Published Works, PhD by Special Regulation, DPhil (Integrated Thesis), PhD by Portfolio of Publication.

This paper makes distinction between critical realism and critical theory (Vandenberghe, 2013, 2, 4, Whelan, 2019), as some critical realist are actually inclined to critical theory rather than critical realism (as advocated by the late Roy Bhaskar). The distinction is beyond the scope of this paper, suffice to say that critical theory (and by extension “Critical Theory”) through its global view, ‘fixation’ on emancipation and cause for action is not completely off tangent to critical realism’s axiological ethos of emancipatory.

The artefact: You may produce a single piece of work such as a documentary, a film script, novel, website, screen works, installation, a manual or tool kit for an art therapy procedure, a digital art therapy programme or a software programme; or a combination of multiple works such as an exhibition of paintings, poetry, theatre pieces, a series of audio productions (for broadcast or podcast), exhibitions or other outputs.” - www.latrobe.edu.au/researchers/grs/hdr

References

Ackroyd S, Karlsson JCH (2014) Critical Realism, Research Techniques, and Research Designs. In: Edwards PK, O’Mahoney J, Vincent S (eds) Studying Organizations Using Critical Realism: A Practical Guide. Oxford University Press, 25–45 https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199665525.003.0002

Adesemowo AK (2019) A Rethink of the Nature and Value of IT Assets – Critical Realism Approach. In: Dwivedi YK, Ayaburi E, Boateng R, Effah J (Eds.), IFIP AICT: ICT unbounded, Social Impact of Bright ICT Adoption. IFIP AICT: Advances in Information and Communication Technology. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, 402–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20671-0_27

Adesemowo AK (2020) CIPPUA: Towards Coherence and Impact in ICT4D/IS. In: Sharma SK, Dwivedi YK, Metri BA, Rana NP (eds.) Re-imagining Diffusion and Adoption of Information Technology and Systems: A Continuing Conversation TDIT 2020. IFIP AICT. IFIP AICT: Advances in Information and Communication Technology. IFIP International Federation for Information Processing. IFIP International Federation for Information Processing, Switzerland AG, 329–340 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64849-7_30

Adesemowo AK (2021) Towards a conceptual definition for IT assets through interrogating their nature and epistemic uncertainty. Computers Security 105:102131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2020.102131

Adesemowo AK, Thomson K-L (2013) Service desk link into IT asset disposal: A case of a discarded IT asset. In: 2013 International Conference on Adaptive Science and Technology. IEEE, Pretoria, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASTech.2013.6707517

Adesemowo AK, Von Solms R, Botha RA (2016) Safeguarding information as an asset: Do we need a redefinition in the knowledge economy and beyond? SA J Inf Manag 18:1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajim.v18i1.706

Adesemowo AK, von Solms R, Botha RA (2017) ITAOFIR: IT Asset Ontology for Information Risk in Knowledge Economy and Beyond. In: Jahankhani H, Carlile A, Emm D, Hosseinian-Far A, Brown G, Sexton G, Jamal A (Eds.) CCIS. Global Security, Safety and Sustainability - The Security Challenges of the Connected World. Springer, London, p 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51064-4_15

Akhlaghpour S, Wu J, Lapointe L, Pinsonneault A (2013) The ongoing quest for the IT artifact: Looking back, moving forward. J Inf Technol 28:150–166. https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2013.10

Alkathiri MS, Olson MR (2019) Preparing doctoral students for the professoriate through a formal preparatory course. Int J Doctoral Stud 14:33–67. https://doi.org/10.28945/4174

Alonge CY, Arogundade O ’T, Adesemowo K, Ibrahalu FT, Adeniran OJ, Mustapha AM (2020) Information Asset Classification and Labelling Model Using Fuzzy Approach for Effective Security Risk Assessment. In: 2020 International Conference in Mathematics, Computer Engineering and Computer Science (IEEE ICMCECS). IEEE, Lagos, Nigeria, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMCECS47690.2020.240911

Alter S (2017) Nothing is more practical than a good conceptual artifact… which may be a theory, framework, model, metaphor, paradigm or perhaps some other abstraction. Inf Syst J 27:671–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12116

Archer MS, Bhaskar R, Collier A, Lawson T, Norrie A (Eds) (2013) Critical Realism: Essential Readings. Routledge, pp. 784. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315008592

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8:19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Asfour A-FA, Winter JP (2018) Whom should we really call a “doctor”? CMAJ: Can Med Assoc J 190:E660. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.69212

Baskerville R, Myers MD, Yoo Y (2020) Digital First: The Ontological Reversal and New Challenges for Information Systems Research. MIS Q 44:509–523. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2020/14418

Bell W (2002) MAKING PEOPLE RESPONSIBLE: The Possible, the Probable, and the Preferable. In: Dators JA (Ed.) Advancing Futures: Futures Studies in Higher Education. Praeger Publishers, Westport, CT, p 33–52. https://books.google.co.za/books?hl=en&lr=&id=AR-CYIXwNvoC06881. Available from (April 24, 2020)

Bennett LA, Toland J, Howell B, Tate M (2019) Revisiting hylomorphism: What can it contribute to our understanding of information systems? In: 30th Australasian Conference on Information Systems 2019 (ACIS2019). Curtin University, Perth, Western Australia, Fremantle, Perth, Western Australia, Australia, 173–179. Available from: https://www.acis2019.org/program/ (December 16, 2019)

Bhaskar R (2009) Scientific Realism and Human Emancipation. Illustrated. Routledge, London, p 360. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203879849

Bhaskar R (2013) A Realist Theory of Science. Routledge, Oxon, Oxford, p 304, https://books.google.co.za/books?id=7318AgAAQBAJ

Bhaskar R (2016) Enlightened Common Sense Enlightened Common Sense: The Philosophy of Critical Realism. Routledge, Routledge, New York, p 224. Hartwig M (Ed.) 2016. | Series: Ontological. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315542942

Bhattacherjee A (2012) Social science research: principles, methods, and practices. Second edition. Anol Bhattacherjee, Tampa, Florida?, p 149, https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/oa_textbooks/3. Available from (August 7, 2023)

Billsberry J, Cortese C (2023) PhD by prospective publication in Australian business schools: provocations from a Collaborative Autoethnography. Int J Doctoral Stud 18:119–136. https://doi.org/10.28945/5102

Boell SK, Cecez-Kecmanovic D (2015) Debating Systematic Literature Reviews (SLR) and their Ramifications for IS: a rejoinder to Mike Chiasson, Briony Oates, Ulrike Schultze, and Richard Watson. J Inf Technol 30:188–193. https://doi.org/10.1057/JIT.2015.15

Boughey C, Niven P (2012) The emergence of research in the South African Academic Development movement. High Educ Res Dev 31:641–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.712505

Boughey C, McKenna S (2017) Analysing an audit cycle: a critical realist account. Stud High Educ 42:963–975. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1072148

Brown J (2006) Reflexivity in the research process: psychoanalytic observations. Int J Soc Res Methodol 9:181–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570600652776

Carlsson SA (2006) Design Science Research in Information Systems: A Critical Realist Perspective. In: Spencer S, Jenkins A (Eds.) ACIS 2006 Proceedings. Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Adelaide, South Australia, http://aisel.aisnet.org/acis2006/40. Available from (December 28, 2016)

Carlsson SA (2011) Critical Realist Information Systems Research in Action. In: Chiasson M, Henfridsson O, Karsten H, DeGross JI (Eds.) Researching the Future in Information Systems. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, Turku, Finland, p 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-21364-9_17

Chang H (2016) Autoethnography. In: Autoethnography as method. Routledge, New York, NY 10017, 43–57. Available from: https://www.routledge.com/Autoethnography-as-Method-1st-Edition/Chang/p/book/9781598741230

Chatterjee S, Sarker S, Lee MJ, Xiao X, Elbanna A (2021) A possible conceptualization of the information systems (IS) artifact: a general systems theory perspective1. Inf Syst J 31:550–578. https://doi.org/10.1111/ISJ.12320

Chong SW, Johnson N (Eds.) (2022) Landscapes and Narratives of PhD by Publication: Demystifying students’ and supervisors’ perspectives. Springer International Publishing, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04895-1

Clegg S (2012) Conceptualising higher education research and/or academic development as ‘fields’: a critical analysis. High Educ Res Dev 31:667–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.690369

Cryer P, Mertens P (2003) The PhD examination: support and training for supervisors and examiners. Qual Assur Educ 11:92–99. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684880310471515

Cuschieri S, Grech V, Savona-Ventura C (2018) WASP (Write a Scientific Paper): how to write a scientific thesis. Early Hum Dev 127:101–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2018.07.012

Davies RE, Rolfe G (2009) PhD by publication: a prospective as well as retrospective award? Some subversive thoughts. Nurse Educ Today 29:590–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2009.01.006

Dobson PJ (2001) The philosophy of critical realism—an opportunity for information systems research. Inf Syst Front 3:199–210. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011495424958

Dowling R, Gorman-Murray A, Power E, Luzia K (2012) Critical reflections on doctoral research and supervision in human geography: The ‘PhD by Publication’. J Geogr High Educ 36:293–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2011.638368

Edwards PK, O’Mahoney J, Vincent S Eds (2014) Studying organizations using critical realism: a practical guide. First edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom, p 376. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199665525.001.0001

El-Gazzar R (2016) Doctoral Dissertation 129 Understanding the Phenomenon of Cloud Computing Adoption within Organizations. Printing Office, University of Agder, Kristiansand, 57654400.98

Evans P (2000) Boundary oscillations: epistemological and genre transformation during the “method” of thesis writing. Int J Soc Res Methodol 3:267–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570050178576

Faulkner P, Runde J (2013) Technological objects, social positions, and the transformational model of social activity. MIS Q 37:803–818

Faulkner P, Runde J (2019) Theorizing the digital object. MIS Q 43:1279–1302. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2019/13136

Fletcher AJ (2017) Applying critical realism in qualitative research: methodology meets method. Int J Soc Res Methodol 20:181–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1144401

Frick L (2019a) PhD by Publication – Panacea or Paralysis? Afr Educ Rev 16:47–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2017.1340802

Frick L (2019b) PhD by Publication – Panacea or Paralysis? Africa Education Review Online Fir: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2017.1340802

Goff WM, Getenet S (2017) Design based research in doctoral studies: adding a new dimension to doctoral research. Int J Doctoral Stud 12:107–121. https://doi.org/10.28945/3761

Goodwyn A (2018) A critical overview of a sample of publications submitted for the award of a PhD by publication. phd. University of Reading Available from: https://centaur.reading.ac.uk/77703/ (2023)

Gregor (2006) The nature of theory in information systems. MIS Q 30:611. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148742

Grover V, Lyytinen K (2015) New state of play in information systems research: the push to the edges. MIS Q 39:271–296. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.2.01

Grover V, Carter M, Jiang D (2019) Trends in the conduct of information systems research. J Inf Technol 34:160–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268396219834122

Gusenbauer M (2019) Google scholar to overshadow them all? Comparing the sizes of 12 academic search engines and bibliographic databases. Scientometrics 118:177–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2958-5

Haigh N (2012) Historical research and research in higher education: reflections and recommendations from a self-study. High Educ Res Dev 31:689–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.689955

Hammersley M (2002) Research as emancipatory: the case of bhaskar’s critical realism. J Crit Realism 1:33–48. https://doi.org/10.1558/jocr.v1i1.33

Hardy C, Phillips N, Harley B (2004) Discourse analysis and content. Anal: Two Solitudes? Qualitative methods 2:19–22. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.998649

Hoddy ET (2019) Critical realism in empirical research: employing techniques from grounded theory methodology. Int J Soc Res Methodol 22:111–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2018.1503400

Holden MT, Lynch P (2004) Choosing the appropriate methodology: understanding research philosophy. Mark Rev 4:397–409. https://doi.org/10.1362/1469347042772428

Houston S (2010) Prising open the black box. Qual Soc Work: Res Pract 9:73–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325009355622

Hu X (2018) Methodological implications of critical realism for entrepreneurship research. J Crit Realism 17:118–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2018.1454705

Ivankova NV, Plano Clark VL (2018) Teaching mixed methods research: using a socio-ecological framework as a pedagogical approach for addressing the complexity of the field. Int J Soc Res Methodol 21:409–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2018.1427604

Jackson D (2013) Completing a PhD by publication: a review of Australian policy and implications for practice. High Educ Res Dev 32:355–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.692666

Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ, Turner LA (2007) Toward a definition of mixed methods research. J Mixed Methods Res 1:112–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806298224

Jordet M (2023) Painting with natural pigments on drowning land: the necessity of beauty in a new economy. J Crit Realism 0:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2023.2217056

Kahn P, Petichakis C, Walsh L (2012) Developing the capacity of researchers for collaborative working. Int J Res Dev 3:49–63. https://doi.org/10.1108/17597511211278643

Kim J-H (2016) Narrative Data Analysis and Interpretation: “Flirting” With Data. In: Understanding Narrative Inquiry: The Crafting and Analysis of Stories as Research. SAGE Publications, Inc., 185–224. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071802861

Kot FC, Hendel DD (2012) Emergence and growth of professional doctorates in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Australia: a comparative analysis. Stud High Educ 37:345–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.516356

Kubota FI, Cauchick-Miguel PA, Tortorella G, Amorim M (2021) Paper-based thesis and dissertations: analysis of fundamental characteristics for achieving a robust structure. Production 31:e20200100. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6513.20200100

Kwiek M (2003) Academe in transition: Transformations in the Polish academic profession. High Educ 45:455–476. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023986406792

Larsen KR, Hovorka DS, Dennis AR, West JD (2019) Understanding the Elephant: The Discourse Approach to Boundary Identification and Corpus Construction for Theory Review Articles. J Assoc Inf Syst 20:887–927. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00556

Lawson T (1997) Economic science without experimentation. In: Economics and reality (Economics as social theory). Routledge, Oxon, OX14 4RN, 199–226. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203195390-22

Leonardi PM (2013) Theoretical foundations for the study of sociomateriality. Inf Organ 23:59–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INFOANDORG.2013.02.002

Leung DY, Chung BPM (2019) Content Analysis: Using Critical Realism to Extend Its Utility. In: Liamputtong P (Ed.) Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Springer Singapore, Singapore, p 827–841. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_102

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK (2010) Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 5:69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Li Y, Thomas M, Liu D (2021) From semantics to pragmatics: where IS can lead in Natural Language Processing (NLP) research From semantics to pragmatics: where IS can lead in Natural Language Processing (NLP) research. Eur J Inf Syst 30:569–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1816145

Lienhard A (2019) Evaluation of academic legal publications in Switzerland. In: Rob van Gestel and Andreas Lienhard (Ed.), Evaluating Academic Legal Research in Europe. Edward Elgar Publishing, 142–169. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788115506.00011

López-Cózar ED, Orduna-Malea E, Martín-Martín A, Ayllón JM (2017) Google Scholar: The Big Data Bibliographic Tool. In: Cantú-Ortiz FJ (Ed.) Research Analytics. Auerbach Publications, Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, FL, p 59–80. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315155890-4