Abstract

When faced with incivility from service recipients, do volunteers feel damaged? As few previous studies have explored this issue, this study uses the conservation of resources theory to investigate the mechanisms through which incivility affects volunteer engagement and burnout, based on three-wave survey data from 1675 volunteers. This study develops a moderated mediation model to examine the effect of incivility on volunteer outcomes. We find that incivility affected volunteers’ subsequent outcomes, reducing engagement and increasing volunteer burnout by lowering volunteers’ psychological detachment. Volunteers’ hostile attribution bias played a moderating role, amplifying the negative impact of incivility on psychological detachment. Hostile attribution bias also enhanced the mediating effect of incivility on volunteer engagement and increased volunteer burnout by reducing psychological detachment. Besides developing a moderated mediation model, this study also proposes that managers should pay attention to strengthening volunteer training and providing psychological counseling to improve psychological detachment for volunteers experienced with incivility from service recipients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In daily volunteer work, volunteers may not only receive praise from their service recipients but also face incivility, such as non-compliance, incomprehension, and even harassment and verbal abuse from their service recipients (Dawood, 2013; Paull and Omari, 2015). Incivility is defined as low-intensity deviant workplace behavior with ambiguous intent (including intentional and unintentional harm) to harm the target (Schilpzand et al. 2016). The ambiguity of intention in uncivil interactions creates uncertainty for targets and observers as to whether the instigator acted deliberately or unintentionally. For example, when a volunteer faces incivility from the recipient, they cannot ascertain whether the incivility is personally directed at them or their organization, or arises from intentional hostility or situational stress. Incivility from customers undermines happiness (Cortina et al. 2001), and can even lead to depression (Lim and Lee, 2011; Burns, 2022). During the COVID-19 pandemic, many epidemic-prevention volunteers reported that customer complaints and verbal abuse caused them to suffer psychological breakdown (Li et al. 2023; Vagni et al. 2020). Even after work, they continued to recall negative interactions there. Existing studies point out that incivility targeted at volunteers is widespread (Trent and Allen, 2019), harming emotions and performance at work (Sliter et al. 2015; Wilson and Holmvall, 2013). Most research on volunteers has focused on their personalities and organizational management. By contrast, the impacts of volunteer service recipients on volunteers has received limited attention.

To date, the impact of incivility from service recipients on volunteers and its underlying mechanism remains unclear. This study therefore examines how incivility affects volunteer engagement and burnout through a three-wave, time-lagged survey of volunteers. According to the conservation of resources (COR) theory, individuals need to devote considerable resources to handling negative stimuli (Hobfoll, 2001). Volunteers use cognitive resources to resolve conflicts with service recipients and emotional resources to accomplish emotional labor (Allen and Augustin, 2021). Regardless of whether incivility is successfully resolved, it will impact individuals’ cognition and emotions, and ultimately consume their resources. After work, individuals need to detach themselves from the negative incidents, to restore their resources. This is psychological detachment, the ability of individuals to detach from work and stop work-related thinking during non-working hours, without interference from work-related issues (Sonnentag, 2012). Research suggests that psychological detachment is beneficial and positively impacts work engagement (Sonnentag et al. 2008). Therefore, we assumed that psychological detachment was the core mechanism through which incivility from service recipients affected volunteer outcomes.

In addition, hostile attribution bias reflects an individual’s interpretation of negative events (Helfritz-Sinville and Stanford, 2014). Individuals with hostile attribution bias are more likely to perceive the external environment or the intentions of others as hostile when faced with ambiguous situations (Tuente et al. 2019). Few previous studies have focused on volunteers’ hostile attribution bias. Volunteers exhibit different levels of agreeableness and emotional stability (Ackermann, 2019). There may be volunteers who are more capable of detaching from incivility, but also sensitive and vulnerable ones. Vulnerable and sensitive volunteers are more likely to react negatively after experiencing incivility (Sliter et al., 2015). When volunteers’ hostile attribution is high, they are more likely to perceive the incivility from the recipients as deliberate hostile behaviors, which makes them fear continuing harassment: the persistent thought “Why is this person doing this to me?” will prevent psychological detachment. Therefore, we believe that volunteers’ hostile attribution bias will moderate the relationship between incivility and psychological detachment. Volunteers with a higher degree of hostile attribution bias will amplify the negative effects of incivility.

This study uses the COR theory to build a moderated mediation model to reveal the mechanism of the influence of incivility on volunteer engagement and burnout. The main theoretical contributions are as follows: First, this study may be one of only a few that focuses on service recipients’ incivility to volunteers. Most previous studies have investigated organizational management factors that influence volunteers (Hallmann and Harms, 2012; Allen and Augustin, 2021). Some studies have analyzed the impact of service recipients’ positive behaviors toward volunteers (Maas et al. 2021; Kulik, 2021; Bang and Ross, 2009), but few studies have focused on negative behaviors such as incivility (Dawood, 2013; Paull and Omari, 2015). Second, this study measured psychological detachment as a mediating variable to further explain the impact of incivility on volunteer engagement and burnout. Finally, by analyzing the hostile attribution bias of volunteers, this study revealed that individual differences among volunteers cannot be ignored. This explains the boundary conditions for the impact of incivility.

This paper is structured as follows: first, we propose the research hypotheses of this study based on a review of relevant prior studies and practical issues. Next, we show how the path analysis model was used to test research hypotheses. Finally, after discussing the research results, we propose practical suggestions to help volunteer organizations assist volunteers in dealing with incivility.

Theory and hypotheses

Incivility and conservation of resources

The COR theory provides a useful theoretical basis for explaining how incivility in the workplace leads to undesirable results, such as loss of work engagement, turnover tendency, and workplace deviance (Sliter et al. 2012; Halbesleben et al. 2014; Zhu et al. 2021). The COR theory states that individuals try to avoid resource loss when facing stressful situations (Hobfoll et al. 2018). Specifically, individuals react to actual and expected resource losses (Hobfoll et al. 2000). For example, when facing criticism from work leaders, people avoid and rationalize criticism to avoid the consumption of resources due to stress (Bhandarker and Rai, 2019). Incivility is a source of stress: if employees cannot properly deal with incivility, it will lead to work conflicts and negatively impact their work, leading to an expected resource loss. To manage incivility, they need to restrain negative emotional reactions and use many cognitive and emotional resources. Such resource loss has a strong negative impact, resulting in work burnout, depression, and other negative physical and mental outcomes (Sliter et al. 2012; Zhu et al. 2021).

For volunteers who experience incivility, recovering psychological resources is particularly important. In the work context, psychological detachment is a key factor in the resource recovery process (Schulz et al. 2019). Psychological detachment is how individuals psychologically detach themselves from work, including cognitive and emotional detachment (Sonnentag and Fritz, 2007). To achieve psychological detachment, it is not enough to simply leave the workplace; continued thoughts about work-related issues must also be stopped (Sonnentag and Bayer, 2005). Experiencing incivility from service recipients often triggers negative emotions such as shame and guilt in volunteers, making it difficult for them to let go of emotions even after ending volunteer service and to truly detach themselves from the stressful situation. Dealing with incivility consumes significant resources such as emotional regulation and coping strategies, reducing the resources available for recovery, and making it difficult for volunteers to detach themselves from their work. Overall, experiencing incivility changes the allocation of resources for volunteers, increasing volunteers’ attention and resource inputs into negative work factors. This means that work-related cognition occupies more psychological resources, making it impossible to achieve a high level of psychological detachment.

The mediating role of psychological detachment

Volunteers who originally intended to help others are most likely to feel psychologically lost when they experience unreasonable complaints, blame, or even abuse from others during volunteer service. Paid employees can buffer the impact of incivility from service recipients by viewing work pay as a service motivation (Megeirhi et al. 2020). However, volunteers’ intrinsic motivation is altruistic, and external motivation is weaker (Hallmann and Harms, 2012; Geiser et al. 2014). As a result, when volunteers experience more incivility, their feelings will likely be contradictory and confused: “Why am I doing good deeds when these people still blame me?” Such internal contradictions will continue to linger in volunteers’ minds. Even with intrinsic motivation, this negative social feedback can frustrate volunteers’ identification with volunteering. Previous studies have shown that rumination and a sense of cognitive dissonance will reduce their psychological detachment (Ingram, 2015). Therefore, we speculated that when faced with incivility, volunteers would find it difficult to achieve psychological detachment. Based on this, we propose the following:

H1: Volunteers’ experiences of incivility from service recipients are negatively related to their ability to psychologically detach from work. The more incivility experienced by volunteers, the more difficult it is for them to achieve psychological detachment.

Psychological detachment, volunteer burnout, and volunteer engagement

According to COR theory, psychological detachment is beneficial as it allows employees to stop work-related thinking after work and temporarily eliminate work stress, thus avoiding the continued consumption of psychological resources and reducing burnout (Sonnentag, 2012). Psychological detachment allows employees to recover resources. The recovered resources can then be used for subsequent work, enabling individuals to focus more attention and have a greater sense of engagement at work. Previous studies have found that when employees experience customer incivility, it can lead to work conflict, reduce employees’ psychological detachment, and affect work performance (Nicholson and Griffin, 2015; Volmer et al. 2012).

After experiencing incivility, volunteers naturally feel a negative emotion such as shame, unhappiness, or and guilt. This emotion casts a net over the individual’s mind, likely causing them to proactively dwell on the negative event (Koster et al., 2011). When the volunteer then encounters a similar situation in their next volunteering, challenging emotion associated with the previous negative situation is activated. This situation recalls hinders the process of psychological detachment, making it difficult for them to effectively restore their resources. Volunteers experiencing difficulty in achieving psychological detachment will focus on the negative factors at work. This forms a negative experience of volunteer service work, which, in turn, aggravates burnout. If volunteers frequently experience incivility at work, burnout will remain at a high level for a long time. When the level of psychological detachment is low, it is difficult for volunteers to fully engage in restoring resources. As a result, the energy they could devote to the next work session will decrease. In contrast, if volunteers can achieve a higher level of psychological detachment, burnout will decrease, and the next volunteer service is still expected to devote more energy. Based on this, we propose the following:

H2: Psychological detachment mediates the relationship between incivility and volunteer outcomes.

H2a: Psychological detachment mediates the negative correlation between incivility and volunteer engagement.

H2b: Psychological detachment mediates the positive correlation between incivility and volunteer burnout.

The moderating role of hostile attribution bias

Different individuals experience different feelings and reactions to uncivil encounters (Alola et al., 2019). Hostile attribution bias refers to individuals’ interpretation of negative events. Individuals with high hostile attribution bias tend to attribute hostility to behaviors they experience, even if that was not the intention (Matthews and Norris, 2002; Adams and John, 1997; Crick and Dodge, 1996). Previous studies have found that employees with higher hostile attribution bias tend to have more negative emotions (Cheng et al., 2020) and are more prone to work conflict (Zhu et al., 2021). In the context of volunteer service, some volunteers may be more empathetic and view incivility as accidental and unintentional, while others may be more sensitive and experience incivility as hostile and deliberate.

In this study, we believe that hostile attribution bias may strengthen the negative relationship between incivility and volunteers’ psychological detachment. The incivility experienced by volunteers is often accidental, and volunteers often do not know why the public or service recipients are so rude to them (Henkel et al., 2017; Torres et al., 2017). We believe that volunteers with higher hostile attribution bias naturally view incivility as intentional harm. This exacerbates the psychological conflict caused by incivility, thereby reducing volunteers’ ability to achieve psychological detachment. This psychological conflict may become more pronounced due to volunteers’ altruistic psychology. Volunteers with high hostile attribution bias will be more confused about why they are doing good deeds but still suffering from other people’s intentional blame, abuse, or even harassment. This confusion will make it more difficult for volunteers to mentally detach themselves from the negative situation.

Some studies have found that employees with strong hostile attribution bias believe they are likely to continue to be treated uncivilly in the future (Walker et al., 2014). This is likely to reduce volunteers’ psychological detachment and make it difficult for them to detach at all. In other words, too much worry and fear will not only lead to a reduction of resources but will also prevent them from recovering resources through psychological detachment. Volunteers with high hostile attribution bias are more likely to recall scenes of incivility outside work and worry about whether they will experience such incivility again next time.

In contrast, when volunteers with low hostile attribution bias experience incivility, they are more likely to interpret incivility as reasonable criticism and suggestions made by service recipients, rather than intentionally hostile acts against them. Therefore, at the end of their work, they will not associate incivility experiences with themselves, thereby reducing the impact of the loss spiral caused by incivility, avoiding volunteer burnout, and maintaining subsequent volunteer engagement.

Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3: Hostile attribution bias enhances the mediating effect of incivility on volunteer outcomes through psychological detachment.

H3a: Volunteers with high hostile attribution bias find it more difficult to detach when experiencing incivility and are more prone to disengagement.

H3b: Volunteers with high hostile attribution bias find it more difficult to detach when experiencing incivility and are more prone to increased burnout.

Method

Sample

Our survey was conducted in Zhejiang Province in the Yangtze River Delta region of China. Zhejiang is a coastal province with a developed economy and ranks among the top provinces in China. Many studies have taken it as a research site (Cheng et al., 2020; Miao et al., 2018). We obtained a directory of nonprofit organizations providing community services in 11 cities in Zhejiang Province. We randomly selected 15 nonprofit organizations in each city. These organizations provided contact information for their long-term active volunteers. We randomly selected 2500 volunteers and sent survey invitations to their mobile phones. Among them, 2135 expressed their willingness to participate in this anonymous survey. The participants in this study were volunteers who filled out the questionnaires on their own accord, without receiving any monetary compensation. We sincerely appreciate the time and effort spent by the participants.

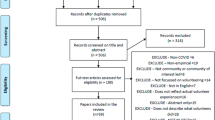

We used a three-wave research design to reduce the likelihood of common method bias (Andersen et al., 2016; George and Pandey, 2017) At time point 1, we investigated incivility and hostile attribution bias, with 1954 volunteers completing an anonymous survey. At time point 2 (two weeks later), we investigated psychological detachment, with 1772 volunteers completing the survey. At time point 3 (two weeks later), we investigated volunteer engagement and burnout. After each survey, we sent thank-you letters, and after the first two surveys, we informed participants that there would be follow-up surveys in two weeks. Eventually, 1675 volunteers completed all the surveys, with a questionnaire recovery rate of 78.45%, which is similar to those reported in previous studies (Trent and Allen, 2019).

The final sample consisted of 1675 respondents, of whom 477 (28.5%) were male, and 1198 (71.5%) were female. The mean age of the respondents was 25.18 (SD = 8.07). Regarding highest education level completed, 35 (2.1%) reported primary school, 699 (5.9%) middle school, 219 (13.1%) high school, 1166 (69.6%) bachelor degrees, and 156 (9.3%) master’s or doctoral degrees. The mean years of volunteering was 2.34 (SD = 1.59). The volunteers in our study were involved in a variety of volunteer programs, including traffic order maintenance, environmental protection monitoring, elderly care, and so on. The sample information in this study is similar to previous surveys of Chinese volunteers by Wu et al. (2018), indicating good sample representativeness.

Measures

All scales used in this study were translated from English to Chinese following a back-translation procedure (Brislin, 1970). All items were rated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Incivility

Incivility was assessed using four items (e.g., Some people spoke aggressively toward the volunteers) adapted from Walker et al. (2014). This scale has been used to measure incivility experienced by volunteers with high reliability (Trent and Allen, 2019). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87.

Psychological detachment

Psychological detachment was measured using four items (for example, I get a break from the demands of volunteering work.) Adapted from Sonnentag and Fritz (2007). The reliability of this scale was proven by Sonnentag et al. (2010). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77

Hostile attribution bias

Hostile attribution bias was measured using six items (e.g., A person is better off if he doesn’t trust anyone.) from the hostility subscale of the California Psychological Inventory (Adams and John, 1997). The reliability of this scale has been proven in Cheng et al. (2020). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77.

Volunteer engagement

Volunteer engagement was assessed using three items (e.g., I am enthusiastic about my volunteering) adapted from the 3-item Utrecht Work Engagement (UWE) scale (Schaufeli et al. 2017). Previous research has shown that the UWE scale has good reliability in the volunteer domain (Vecina et al., 2012; Curran and Taheri, 2021; Erks et al., 2020). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.81.

Volunteer burnout

Volunteer burnout was measured using three items (e.g., I feel emotionally drained from my volunteering work) adapted from Watkins et al. (2015). This scale has been used to measure feelings of burnout in volunteers with high reliability (Trent and Allen, 2019). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77.

Results

Descriptive statistic, correlation analysis, and confirmatory factor analysis were performed first. The mediation and moderation effects were then tested through path analysis using Jamovi 2.1(2022), based on the R-lavaan package.

Confirmatory factor analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to test whether the four variables of incivility, psychological detachment, hostile attribution bias and volunteer engagement, represented distinct constructs. The results showed that the five-factor model had the best fit for the data (χ2 = 846.32, df = 153, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.031, CFI = 0.953, TLI = 0.941). Table 1 presents the results of descriptive and correlational analyses between study variables.

A Harman’s single factor test was conducted to check common method variance (CMV). The results showed the variance of a single factor was 36.95%, which was less than the suggested threshold value of 40% (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Multicollinearity issues in the model were checked using the variance inflation factor (VIF). The results revealed that the VIF value of the variables ranged from 1.17 to 1.63, which is less than the suggested threshold value of 5 (Venkatesh et al., 2012). Compared to the competition model in Table 2, the theoretical model in this study has the best fit, indicating that the five variables have good discriminative validity (Fig. 1).

Path analysis model

The path analysis model was used to test the hypotheses. The results showed that incivility was negatively related to psychological detachment (β = −0.12, p < 0.001), which supports H1. Further, incivility was negatively associated with volunteer engagement (β = −0.15, p < 0.001) and positively associated with volunteer burnout (β = 0.06, p < 0.001). Of the demographic variables, only education level was negatively correlated with volunteer engagement (β = −0.07, p < 0.001) and not correlated with volunteer burnout (β = 0.01, p = 0.401); age and gender were not significantly correlated with either volunteer engagement or volunteer burnout, respectively (ps. > 0.05).

We examined the mediating effect of psychological detachment on volunteer outcomes using a bias-corrected bootstrap procedure with 1000 bootstrap samples (MacKinnon et al., 2007). The results indicated that incivility negatively affected volunteer engagement via psychological detachment (β = −0.07, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.107, −0.050]) and a positive effect on volunteer burnout via psychological detachment (β = 0.09, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.057, 0.121]). Therefore, H2 is supported.

To test H3, we conducted a moderated path analysis (Edwards and Lambert, 2007; shown in Fig. 2). The mediating effect of psychological detachment between incivility and volunteer engagement was strengthened by high hostile attribution bias (β = −0.09, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.138, −0.070]), but not low attribution bias (β = −0.02, p = 0.062, 95% CI = [−0.045, 0.001]). The indirect effect was significant (β = −0.07, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.089, −0.035]). Moreover, the mediating effect of incivility on volunteer burnout via psychological detachment was stronger when hostile attribution bias was high (β = 0.113, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.019, 0.078]) than when it was low (β = 0.030, p = 0.050, 95%CI = [−0.001, 0.062]). The indirect effect was significant (β = 0.07, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.009, 0.070]).

The moderated path analysis further supported that for those with high hostile attribution bias, the impact of incivility on psychological detachment was increased (β = −0.19, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.245, −0.128]), whereas for those with low hostile attribution bias, the effect was weaker (β = −0.05, p = 0.051, 95% CI = [−0.095, −0.001]).

Discussion

Our study reveals how incivility from service recipients affects volunteer outcomes. Through a three-wave survey, we found that incivility from service recipients affected volunteers’ ability to achieve psychological detachment, which, in turn, hindered their engagement in volunteer services and led to higher volunteer burnout. Further, volunteers’ hostile attribution increased this indirect effect. This study provides the following insights at the theoretical level.

First, previous studies have focused more on incivility within volunteer service organizations and less on incivility from service recipients. As pointed out by Dawood (2013) and Paull and Omari (2015), the incivility experienced by volunteers may come more from service recipients than from within the organization. Using a large sample of volunteer (N = 1675) data collected in three waves, this study found that the score of incivility from service recipients was 3.67, indicating that volunteers experienced incivility from service recipients to some extent. These findings show that research on incivility experienced by volunteers is timely and necessary, and future research should further deepen this understanding.

Second, this study introduces the concept of psychological detachment in volunteer services. Psychological detachment is a necessary process for recovering volunteer resources (Schulz et al. 2019). It exerts a significant influence on the relationship between incivility and volunteer outcomes. This study revealed the moderating role of hostile attribution bias on volunteer perception of incivility from service recipients. Incivility’s negative impact on volunteers becomes more pronounced with volunteers’ higher levels of hostile attribution bias, thereby lowering volunteer engagement. This aligns with prior research on the diversity of volunteers (Dolnicar and Randle, 2007). However, our study may be the first to use hostile attribution bias as an explanatory variable for individual volunteer differences. It should be noted that the hostile attribution bias referred to in this article does not mean that volunteers are unwilling to help others but that volunteers sometimes have neurotic tendencies (Czarna et al., 2021). The vulnerability, sensitivity, and inability to defend against external negative information brought about by neuroticism are reflected in higher levels of hostile attribution bias.

Finally, we used two negatively correlated outcome variables, volunteer engagement and volunteer burnout, as indicators of volunteer outcomes. Choosing reverse outcome variables further enhances the robustness of the model (Campbell and Fiske, 1959). It responds to previous scholars’ calls for volunteer service research to choose multiple outcome variables to improve model robustness (Clark and Watson, 2019).

Managerial implications

Volunteer organizations pay insufficient attention to incivility experienced by volunteers. (1) Given the harmful effects of incivility from service recipients, volunteer organizations should train volunteers to deal with it and prevent them from experiencing long-term psychological damage. (2) Volunteer organizations should allow volunteers to suspend volunteering work and achieve psychological detachment instead of doing service work with fatigue, which is overdrawing future volunteer behavior. Volunteer organizations may organize post-volunteer service meetings to help volunteers vent and quickly recover psychological resources (Hershcovis et al., 2018; Jang et al., 2020; Thieleman and Cacciatore, 2014) (3) Finally, this study found that volunteers with higher hostile attribution bias are more easily affected by incivility. Accordingly, volunteer organizations should arrange for volunteers with low hostile attribution bias to perform roles requiring communication with service recipients, while also identifying and conducting resilience training for volunteers with high hostile attribution bias, thereby helping them to overcome its negative effects (Parlak et al., 2022).

Limitations and scope for future study

This study has some limitations. Although two variables (volunteer burnout and engagement) were used as indicators to measure volunteer outcomes, we relied on volunteers’ self-reported data rather than more objective indicators. In future studies, we recommend that researchers use objective variables such as actual volunteer service time to better test the impact of incivility on volunteer engagement.

We encourage future researchers to explore the relationship between incivility and volunteer outcomes in more detail. For example, incivility from service recipients and from volunteer service leaders may have different effects. Compared to volunteers who need to obey service leaders, the relationship between volunteers and service recipients is more equitable. Differences in power status may alter the impact of incivility on volunteers (Hershcovis et al., 2017). Volunteers are less likely to resist incivility from leaders due to their higher leadership status, resulting in deeper psychological damage.

Ackermann (2019) suggests that more attention should be paid to the effects of differences in volunteers’ individual personality traits. As a personal trait, belief in a just world (BJW) promotes volunteer effectiveness and willingness to help people (Correia et al., 2016), and might also have a potential effect on volunteers. Belief in a just world refers to the belief that the world is fair and that immoral people should be punished while virtuous people should be rewarded (Dalbert, 2009). Volunteers with low BJW believe that the world is unjust and lack a sense of justice. This may exacerbate the negative impact of incivility, further damaging motivation to volunteer, and increase volunteer burnout. Therefore, future research should explore the moderating roles of BJW on incivility and volunteer outcomes. Additionally, it has been found that rumination (brooding) negatively affects psychological disengagement (Saffrey and Ehrenberg, 2007), whereas contemplation does not (Weigelt et al., 2019). Future research could further compare the impacts of rumination and contemplation, and explore whether there are different levels of mediating effects between uncivil behavior and psychological disengagement.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to data protection obligations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ackermann K (2019) Predisposed to volunteer? Personality traits and different forms of volunteering. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 48(6):1119–1142

Adams SH, John OP (1997) A hostility scale for the California psychological inventory: MMPI, observer Q-sort, and big-five correlates. J Pers Assess 69(2):408–424

Allen JA, Augustin T (2021) So much more than cheap labor! Volunteers engage in emotional labor. Soc Sci J 1–17

Alola UV, Olugbade OA, Avci T et al. (2019) Customer incivility and employees’ outcomes in the hotel: testing the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Tour Manag Perspect 29:9–17

Andersen LB, Heinesen E, Pedersen LH (2016) Individual performance: From common source bias to institutionalized assessment. J Publ Adm Res Theory 26(1):63–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muv010

Bang H, Ross SD (2009) Volunteer motivation and satisfaction. J Venue Event Manag 1(1):61–77

Bhandarker A, Rai S (2019) Toxic leadership: emotional distress and coping strategy. Int J Organ Theory Behav 22(1):65–78

Brislin RW (1970) Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross-Cult Psychol 1(3):185–216

Burns ST (2022) Workplace mistreatment for US women: best practices for counselors. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9:131. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01154-z

Campbell DT, Fiske DW (1959) Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol Bull 56(2):81

Cheng B, Dong Y, Zhou X et al. (2020) Does customer incivility undermine employees’ service performance? Int J Hosp Manag 89:102544

Cheng Y, Yu J, Shen Y et al. (2020) Coproducing responses to COVID-19 with community-based organizations: lessons from Zhejiang Province, China. Public Adm Rev 80(5):866–873

Clark LA, Watson D (2019) Constructing validity: new developments in creating objective measuring instruments. Psychol Assess 31(12):1412

Correia I, Salvado S, Alves HV (2016) Belief in a just world and self-efficacy to promote justice in the world predict helping attitudes, but only among volunteers. Span J Psychol 19:E28

Cortina LM, Magley VJ, Williams JH et al. (2001) Incivility in the workplace: incidence and impact. J Occup Health Psychol 1:64

Crick NR, Dodge KA (1996) Social information‐processing mechanisms in reactive and proactive aggression. Child Dev 67(3):993–1002

Curran R, Taheri B (2021) Enhancing volunteer experiences: using communitas to improve engagement and commitment. Serv Ind J 41(15-16):1053–1075

Czarna AZ, Zajenkowski M, Maciantowicz O et al. (2021) The relationship of narcissism with tendency to react with anger and hostility: The roles of neuroticism and emotion regulation ability. Curr Psychol 40:5499–5514

Dalbert C (2009) Belief in a just world. Handbook of individual differences in social behavior. The Guilford Press, New York, p 288–297

Dawood SR (2013) Prevalence and forms of workplace bullying in the voluntary sector: is there a need for concern? Volunt Sect Rev 4(1):55–77

Dolnicar S, Randle M (2007) What motivates which volunteers? Psychographic heterogeneity among volunteers in Australia. Voluntas 18:135–155

Edwards JR, Lambert LS (2007) Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: a general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol Methods 12(1):1

Erks RL, Allen JA, Harland LK et al. (2020) Do volunteers volunteer to do more at work? The relationship between volunteering, engagement, and OCBs. 32:1–14

Geiser C, Okun MA, Grano C (2014) Who is motivated to volunteer? A latent profile analysis linking volunteer motivation to frequency of volunteering. Psychol Test Assess Model 56(1):3

George B, Pandey SK (2017) We know the yin-but where is the yang? Toward a balanced approach on common source bias in public administration scholarship. Rev Public Pers Adm 37(2):245–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X17698189

Halbesleben JR, Neveu JP, Paustian-Underdahl SC et al. (2014) Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J Manag 40(5):1334–1364

Hallmann K, Harms G (2012) Determinants of volunteer motivation and their impact on future voluntary engagement: A comparison of volunteer’s motivation at sport events in equestrian and handball. Int J Event Festiv Manag 3(3):272–291

Helfritz-Sinville LE, Stanford MS (2014) Hostile attribution bias in impulsive and premeditated aggression. Pers Individ Differ 56:45–50

Henkel AP, Boegershausen J, Rafaeli A et al. (2017) The social dimension of service interactions: observer reactions to customer incivility. J Serv Res 20(2):120–134

Hershcovis MS, Ogunfowora B, Reich TC et al. (2017) Targeted workplace incivility: the roles of belongingness, embarrassment, and power. J Organ Behav 38(7):1057–1075

Hershcovis MS, Cameron AF, Gervais L et al. (2018) The effects of confrontation and avoidance coping in response to workplace incivility. J Occup Health Psychol 23(2):163

Hobfoll SE (2001) The influence of culture, community, and the nested‐self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl Psychol 50(3):337–421

Hobfoll SE, Halbesleben J, Neveu JP et al. (2018) Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu Rev Organ Psych 5:103–128

Hobfoll SE, Shirom A, Golembiewski R, Golembiewski RT (2000) Conservation of resources theory. Handbook of organizational behavior. CRC Press, Florida, p 57–80

Ingram KE (2015) Always on my mind: The impact of relational ambivalence on rumination upon supervisor mistreatment. Paper presented at Academy of Management Proceedings, 30 November 2015

Jang J, Jo W, Kim JS (2020) Can employee workplace mindfulness counteract the indirect effects of customer incivility on proactive service performance through work engagement? A moderated mediation model. J Hosp Mark Manag 29(7):812–829

Koster EH, De Lissnyder E, Derakshan N et al. (2011) Understanding depressive rumination from a cognitive science perspective: the impaired disengagement hypothesis. Clin Psychol Rev 31(1):138–145

Kulik L (2021) Multifaceted volunteering: The volunteering experience in the first wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic in light of volunteering styles. Anal Soc Issues Public Policy 21(1):1222–1242

Li J, Huang C, Yang Y et al. (2023) How nursing students’ risk perception affected their professional commitment during the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating effects of negative emotions and moderating effects of psychological capital. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:195. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01719-6

Lim S, Lee A (2011) Work and nonwork outcomes of workplace incivility: does family support help? J Occup Health Psychol 16:95–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021726

Maas SA, Meijs LC, Brudney JL (2021) Designing “national day of service” projects to promote volunteer job satisfaction. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 50(4):866–888

MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS (2007) Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol 58:593–614

Matthews BA, Norris FH (2002) When is believing “seeing”? Hostile attribution bias as a function of self‐reported aggression. J Appl Soc Psychol 32(1):1–31

Megeirhi HA, Ribeiro MA, Woosnam KM (2020) Job search behavior explained through perceived tolerance for workplace incivility, cynicism and income level: A moderated mediation model. J Hosp Tour Manag 44:88–97

Miao Q, Newman A, Schwarz G et al. (2018) How leadership and public service motivation enhance innovative behavior. Public Adm Rev 78(1):71–81

Nicholson T, Griffin B (2015) Here today but not gone tomorrow: Incivility affects after-work and next-day recovery. J Occup Health Psychol 20(2):218

Parlak S, Tunç EB, Eryiǧit D et al. (2022) Relationships between hostility, resilience and intolerance of uncertainty: A structural equation modeling. J Evid-Based Psychother 22(1):1–20

Paull M, Omari M (2015) Dignity and respect: important in volunteer settings too. Equal Divers Incl 34(3):244–255. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-05-2014-0033

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP (2012) Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol 63:539–569

Saffrey C, Ehrenberg M (2007) When thinking hurts: attachment, rumination, and post-relationship adjustment. Pers Relatsh 14(3):351–368

Schaufeli WB, Shdazu A, Hakanen J et al. (2017) An ultra-short measure for work engagement. Eur J Psychol Assess 35:577–591

Schilpzand P, De Pater IE, Erez A (2016) Workplace incivility: a review of the literature and agenda for future research. J Organ Behav 37:S57–S88

Schulz AD, Schöllgen I, Fay D (2019) The role of resources in the stressor–detachment model. Int J Stress Manag 26(3):306

Sliter M, Sliter K, Jex SM (2012) The employee as a punching bag: the effect of multiple sources of incivility on employee withdrawal behavior and sales performance. J Organ Behav 33(1):121–139

Sliter M, Withrow S, Jex SM (2015) It happened, or you thought it happened? Examining the perception of workplace incivility based on personality characteristics. Int J Stress Manag 22(1):24

Sonnentag S (2012) Psychological detachment from work during leisure time: the benefits of mentally disengaging from work. Curr Dir Psychol 21(2):114–118

Sonnentag S, Bayer UV (2005) Switching off mentally: predictors and consequences of psychological detachment from work during off-job time. J Occup Health Psychol 10(4):393

Sonnentag S, Fritz C (2007) The Recovery Experience Questionnaire: development and validation of a measure assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. J Occup Health Psychol 12:204–221

Sonnentag S, Mojza EJ, Binnewies C et al. (2008) Being engaged at work and detached at home: a week-level study on work engagement, psychological detachment, and affect. Work Stress 22(3):257–276

Sonnentag S, Binnewies C, Mojza EJ (2010) Staying well and engaged when demands are high: the role of psychological detachment. J Appl Psychol 95(5):965

Thieleman K, Cacciatore J (2014) Witness to suffering: mindfulness and compassion fatigue among traumatic bereavement volunteers and professionals. Soc Work 59(1):34–41

Torres EN, van Niekerk M, Orlowski M (2017) Customer and employee incivility and its causal effects in the hospitality industry. J Hosp Mark Manag 26(1):48–66

Trent SB, Allen JA (2019) Resilience only gets you so far: volunteer incivility and burnout. Organ Manag J 16(2):69–80

Tuente SK, Bogaerts S, Veling W (2019) Hostile attribution bias and aggression in adults-a systematic review. Aggress Violent Behav 46:66–81

Vagni M, Giostra V, Maiorano T et al. (2020) Personal accomplishment and hardiness in reducing emergency stress and burnout among COVID-19 emergency workers. Sustainability 12(21):9071

Vecina ML, Chacón F, Sueiro M et al. (2012) Volunteer engagement: does engagement predict the degree of satisfaction among new volunteers and the commitment of those who have been active longer? Appl Psychol-Int Rev 61(1):130–148

Venkatesh V, Thong JY, Xu X (2012) Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q 36(1):157–178

Volmer J, Binnewies C, Sonnentag S et al. (2012) Do social conflicts with customers at work encroach upon our private lives? A diary study. J Occup Health Psychol 17:304–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028454

Walker DD, Van Jaarsveld DD, Skarlicki DP (2014) Exploring the effects of individual customer incivility encounters on employee incivility: The moderating roles of entity (in) civility and negative affectivity. J Appl Psychol 99(1):151

Watkins MB, Ren R, Umphress EE et al. (2015) Compassion organizing: Employees’ satisfaction with corporate philanthropic disaster response and reduced job strain. J Occup Organ Psychol 88(2):436–458

Weigelt O, Gierer P, Syrek CJ (2019) My mind is working overtime—towards an integrative perspective of psychological detachment, work-related rumination, and work reflection. Int J Environ 16(16):2987

Wilson NL, Holmvall CM (2013) The development and validation of the incivility from customer scale. J Occup Health Psychol 18(3):310–326

Wu Z, Zhao R, Zhang X et al. (2018) The impact of social capital on volunteering and giving: evidence from urban China. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 47(6):1201–1222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764018784761

Zhu H, Lyu Y, Ye Y (2021) The impact of customer incivility on employees’ family undermining: a conservation of resources perspective. Asia Pac J Manag 38:1061–1083

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (21&ZD184).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QM: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, writing-reviewing, and editing. JH: methodology, software, formal analysis, and writing-original draft. HY: writing-reviewing and editing. All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by QM, JH, HY. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JH and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this type of study is not required by our institute. Ethical approval was therefore not provided.

Informed consent

Respondents’ participation in this study was voluntary. A total of 1675 sampled participants accepted and voluntarily participated in the study after the researchers assured them of anonymity and that their responses were solely used for academic purposes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miao, Q., Huang, J. & Yin, H. Lingering shadows: the negative effects of incivility on volunteers. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 974 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02479-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02479-z