Abstract

This essay delves into the essentialities of object-giving sources within the formulation of epistemic objectivity. It explores the relationship between objectivity and intentional states, particularly in the context of immediate and transcendent experiences. A key focus of this paradigm is the examination of inferences and how they are held in X’s intentional processes. These claims about inferences contribute to the perception of objectivity by highlighting the epistemological transitions of things that occur in the constitutive ideation. Additionally, the activity within X’s episteme leads to significant articulations that reflect a structural realism of experiences. The essay also introduces a convention of the experiential-intentional process so that the causality manipulations could be avoided by the precents of sources of ideation. In this instance, the central niche is occupied by transcendental reflections of intentionality, which are fundamentally founded on experiences and objectivity, and they possess a distinct rhetorical quality. They manifest as acts, propositional forms, and constituents, all of which contribute to the understanding and justification of objectivity. To establish such a framework that upholds objectivity, certain prerequisites must be met. Firstly, the framework must possess justificational resources that prevent causality manipulations. Secondly, pre-reflective sources should not inter-define causality in epistemic circumstances, although this does not exclude the emergence of causal relations, and thus this approach offers a correlational explanation. Lastly, transcendental reflections should remain compatible with the experiential-intentional process, allowing for the accommodation of subjectivity in the justification of objectivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Husserl and foundational(ism): all about knowledge

According to J.N. Mohanty, Husserlian phenomenology aims at absolute knowledge: non-relative, grounding of human knowledge (Mohanty, 1988, p. 177). Several commentators, including both critics and supporters, argue that Husserlian phenomenology plays a significant role in establishing the foundations of knowledge. They suggest that this approach incorporates elements of traditional conservativity, particularly when examining Descartes’s pursuit of knowledge (Sartre, 1956). Despite this, the prime focus of phenomenology is to reveal the underlying explanations for an individual’s perceptions about their state of affairs. Such a concept has been characterized by our way of thinking about life in our surroundings, at least in terms of the causal explanations of comprehension, namely common and ordinary experiences encompassing sensuous, theoretical, and reasoning knowledge. For example, observing the causal elements involved in plant growth: soil, water, and light. This means sensual, theoretical, and phenomenological knowledge and reasoning acts are situated in all our experiences.

Smith and McIntyre (1982) demonstrated that Husserl shared Descartes’s ideas on the foundations of knowledge. In the Prolegomena, Husserl emphasized the importance of theoretical completion by metaphysics and logic for the ‘sense of science’. However, despite this emphasis, only a few scholars have attempted to pursue this theoretical completion through metaphysics and the theory of knowledge (Husserl, 2001). Subsequently, the completion itself necessitates extensive and rigorous preliminary phenomenological investigations (Husserl, 2001). Husserl discusses the idea that all non-phenomenological sciences (e.g., putative positive sciences) are dogmatic and must be subjected to phenomenological criticism in order to produce an absolute grounding for knowledge in us (Husserl, 1983, p. 141). This argument, according to contemporary critics, is analogous to the old platonic idea of genuine science as per formal and transcendental logic: knowledge grounded on absolute foundations, which reminds me of a discussion with Hopp in 2021: naturally, it attributes to transcendental phenomenologists an attempt to justify existing sciences to establish epistemological foundations from a phenomenological perspective. Given this, Hopp (2008a) thinks that the sources of knowledge that underpin the epistemic foundational conditions can be categorized as follows: Firstly, a proper noetic structure, which can be established either through epistemic foundations or directly and indirectly through various means. It is crucial that all noetic structures related to this are formed accurately. Secondly, while every piece of knowledge is not inherently epistemically founded, certain proportions of knowledge are based on phenomenological foundations. Lastly, it is important to note that the epistemic foundational conditions are not a psychological thesis and do not pertain to an actual noetic structure. Instead, they fulfill the requirements for constitutive peripherals of a proper noetic structure. In contemporary epistemological foundationalism literature, there are proponents and opponents for the justification of foundationalism, such as Fumerton (2006), Alston (2005), Steup (2005), Audi (2001), and Howard-Snyder (2005). These versions of epistemic foundational(-ism), in their non-skeptical forms, assert that beliefs that are epistemically founded must possess certainty in relation to truth and should remain unaltered by any subsequent corrections. Indeed, for non-epistemic foundationalists, this is not a necessary component of foundationalism. However, qua foundationalists are steadfast in their views, and they see the content of mental states as foundational. Its precise epistemic status confers the non-foundational nature on the relations that make it available, but Hopp’s second ‘epistemic foundational condition’ is merely applicable to the content of the foundational mental states: one can reach absolute certainty, at least concerning some matters, and also that…it [is] a main task of philosophy to attain such certainty (Føllesdal, 1988, p. 107). But Husserl’s position about the necessity of infallibilism is different. Zahavi (2003) attempted to clarify this with three major claims (Zahavi, 2003, p. 67; Hopp, 2008a, 2008b, p. 196.) referring to …. for motives long forgotten and, in any case, never clarified, reduces evidence to an insight that is apodictic, absolutely indubitable, and, so to speak, absolutely finished in itself—is to bar oneself from an understanding of any scientific production (Husserl, 1969, sec. 60, p. 161).

The primary assertion posits Hopps’s epistemic foundational conditions discussed earlier, without necessitating absolute certainty in foundational knowledge. It extrapolates the notion of what Husserl has described as an unostentatious form of foundationalism, wherein epistemically founded knowledge can be acquired in bits and pieces (Berghofer, 2019). This perspective allows for a level (degree) of commitment that does not reach certainty, or in simpler terms, uncertainty. In light of Zahavi (2003) the second claimFootnote 1, does not confront all the phenomenological propositions before the scientific propositions. As a result, an epistemological foundationalism is not required to fulfill the science of phenomenology and other non-phenomenological bits and pieces of knowledge. Non-phenomenological propositions of knowledge, on the other hand, are dependent on a few phenomenological propositions. The final claim asserts that epistemological foundations are responsible for more than just responding to individual beliefs, which logically implies non-foundational commitments or the involvement of any other natural relation. Conversely, it is intended to establish the supremacy of truth through the justificatory notion of seeking to learn. According to Mohanty (1988), thought and recognition have an idealist character for the constitutive component of knowledge but are always influenced by temporal relations. We will understand the distinctive nature of such a constituent portion if and only if we delve into our knowing act. The statement’s meaning translates as knowledge being “constituted” by an act, and what if such an act is not completely definable as we articulate it, except in terms of the knowing act?

Episteme in the account of judgmental sense

Husserl’s emphasis on comprehending the origins, grasping, and acquisition of knowledge is a crucial issue in the fields of positive, naïve, and non-phenomenological sciences. This argument remains an active component in pre-thought and experiences, as stated by Husserl (2001). However, pre-thinkingFootnote 2 is a natural process of the unconscious state with pre-reflective projections, which are known as having first-order constituents: experiences, inferences, and awarenessFootnote 3. These constituents are in contrast to the lack of explicit to-meness or owningness, which is a quality of possessing. The outcome of such an orientation reveals the degree of self-reference in our articulations and sometimes in our actions. Notably, this outcome has been overlooked as a matter of factual relevance. From a particular perspective, the presence of rigidity and conservatism enables individuals to develop specific forms of ideas and habits that are not influenced by changing situations or eventualities. As a result, the question is how such tendentious perspectives are conditionally characterized as mental constituentsFootnote 4 in an intuitive capacity when the instance is ‘A knows that p,’ where A is a subject with knowledge about something, and p is the proposition that describes what is to be known. We may question what situations assist A justify that p is the instance, and this should be explored in both traditional and non-traditional ways. In traditional analysis, knowledge is a justified true belief; for example, in the case of factual knowledge, the false propositions cannot be known because the attributions of knowledge require at least a true belief to justify p. Additionally, A does not believe the proposition p, and thus p cannot be the proposition that A knows. On this account, knowledge must be justified by the fulfillment of truth and a justified belief in the truth, that is, ‘A knows that p is true, and thus A’s stance is justified in believing p’. Consequently, ‘if A is not correct in believing p in a given situation’, it may not translate to the meaning, and might not satisfy the sufficient and necessary conditions to believe that p is true. A non-traditional approach, on the other hand, differs in terms of whether A’s belief has an objective probability of truth or not. Again, truth is a necessary condition of knowledge on most fallibilismFootnote 5 accounts of knowledge; at the very least, it does not require a true belief to justify p. Even so, we can say that truth is a necessary condition of knowledge; that is, if a belief is not true, it cannot constitute knowledge. As a result, if there is no such thing as truth in a subject’s epistemic belief, then there can be no knowledge, and this is accomplished if and only if a belief originates in mental states with a provocation from relevant cognitive facultiesFootnote 6.

The following sections focus on how and where phenomenological knowledge emerges concerning state-of-affairs, i.e., knowledge about knowledge emerges. On the one hand, such knowledge cannot necessarily be expressed, explained, or explicated in a straightforward propositional or prosaic manner (van Manen and van Manen, 2021, p. 1077). On the other hand, does phenomenological knowledge (including non-phenomenological attributes from ordinary experiences) form the central function of the pre-(theoretical) thoughts that necessarily allow objective categories in reasoning? Following that, based on Husserl’s debate for objective categories of truth claimed concerning the transcendental correlation of things, we would discuss the philosophical validity of such a viewpoint (aka objects). These studies would also ask whether knowledge is dependent on the epistemic belief principles that the subject is aware of, nor what they entail.

Constituents and experientiality

How do objects, regardless of their type, constitute our knowledge? The same object can be the object of perception, of judgment, of inference of feelings, or aversion. Thus, there is a certain independence from the varying modes of apprehension (Mohanty, 1954, p. 345). The independence in question, which is a character object, has polarities of negative and positive character in the acts, particularly when the object is confronted with the problem of identity (Corazza, 2018). The primest consideration is that an object can persist across all variations of acts and not just the character polarities. The same object’s aboutness can appear in the ultimate objective of various acts, i.e., goal-seeking intention. Owing to the nature of constituents, such object(s)Footnote 7 is not the intentions, and besides that which intention is directed. Like, S = {the table that I am seeing now} is not intended, but rather a bearer of intention or aboutness of the act. As such, this act relies on the justification of truth-claimed relations and satisfies objectivity, but what is the ground within the general noesis-noema doctrine? And X, as an experiencer, should be aware that the noetic-noematic structure follows parallelism, implying that all kinds of experiences share common properties. In the doctrine, if the noesis (conscious act) has different corresponding objects for each noema (meaning of the act), then what is implied by the S is that a corresponding object endures as an ultimate objective of varying acts within the judgmental sense. To be known, every conscious act (noesis) has a nucleus that contains its (own) meaning, which is reflected in its correspondence (interventions). Such meanings can be coupled to the object with shared properties in a different nucleus for the noemata of various perceptual acts that exist. These different nuclei are proximity within a referential unity, which is something determinable but hidden in each nucleus; that is, a referent is evidence for self-perception manifesting through its reflectionsFootnote 8.

This means that where the grounds are expected to be understood, the given in an intuition offers referentiality. As a result, it is vital to explore the central substance of Husserl’s phenomenal intentionality, in which our inner experiences emerge to be directed beyond themselves and toward bodily manifestations. Intentionality is known to be the primary component in phenomenological descriptions of all our experiences, and these experiential facts are the most fundamental phenomenological facts. The descriptive elucidation of intentionality from subjective experiences is the focal point of the Husserlian theory of knowledge problem, which has driven the exploration into the constituent manifestation in the act of transformation between non-objectual and objectual things. This conception might stand squarely for skeptics, given the Kantian tradition, which regards knowledge as merely the product of intuition and concept. For instance, if X believes that a rose flower is blooming in the backyard and that it is red, then a thought must be intended for the relevant state-of-affairs. This implies that the operations of ‘meaning-intention acts’ in thought must be associated with the justified belief corresponding to the relevant state-of-affairs. However, after attending to the newly bloomed flower that is surrounded by bushes in the same backyard, one may perceive that their propositions possess pure meanings. So, while the pure meanings may be instantiated in the meaning-intention acts, this does not justify knowledge of their truth-claimed relations. Whereas the ultimate objective (i.e., goal-seeking intention) descriptively serves to ensure fulfillment through the matter of conscious intuitive projection; it is a kind of wedding of the pure meanings to an intuition of the same object in the act of fulfillment. This context highlights Husserl’s extensive discussions on intentional content. Meanings, in general, are the type of intentional content of meanings—intentional acts and acts of thought within a knowing act—in which the intuitional component satisfies the awareness of the object (thing) itself in the body (leibhaft) with intuitive fullness, as intended in the act (Husserl LI, VI16; Husserl TS, 4–5).

We can observe the consistency of an essential distinction between the acts of intentional content and their objects. The intentional feature of an act as an element in intuitive activity is, by virtue, intentionally directed to its object, which manifests in the world through bodily presence as actions of intuitive capacity (Husserl LI, V Section 20). To draw a logical conclusion, we might say that the intentional features manifest the essential part of the intuitive capacity in state-of-affairs that represent the relevant object relations: properties or propositions. For example, seeing the red-bloomed rose in the backyard has propositions, as intentional features cannot exist alone without an intuitive act. As a result, the intentional feature is an instance of an intuitive act that is distinct from the meaning content and the object (thing) itself; however, intuitive acts traverse their hands, corresponding to meaning-intention acts. Given this, the ideal meaning can be expressed in subjective experiences as mental states such as believing, imagining, remembering, desiring, and so on. Nonetheless, it may differ from the objectual experience, as the intentional content of experience is to be determined by how things appear in subjective experiences. That intentional content cannot be determined merely through experiencing historical, causal, and (Theo-)functional relationships, but rather by their interventions as referential relations at the nucleus of conscious acts, i.e., a series of perspective variations’, (aka sensuous components). How does the unity of appearances on a continuum lead to referential things? As a ‘problem’ that must be addressed on a transcendental level through phenomenological clarification.

As Husserl described: in the spirit of phenomenological science, we are to describe noematicaly all the connections of consciousness that render necessary a plain object precisely in its character as real (Husserl, 1983, p. 377). This condition enables the problem to be explained in two distinct kinds of intentional experiences in different ways using the same criterion. The true being reduces itself to givenness (immanent and transcendent), but it is important to understand whether this givenness is adequate by considering two cases within a phenomenological analysis (Husserl, 1983, p. 395). In immanent experiences, the adequacy of the object is understood as the absolute and comprehensive presence of the object itself. It encompasses all potential and actual determinants that contribute to its nature, leaving no space for uncertainty or ambiguity. However, this conditioning takes on a distinct character in the context of transcendental perception, as there is always a margin of indeterminacy that can be discerned in some manner. Since it never fully reaches the object’s experiential adequateness, the principle of judgmental sense has been invoked to represent the deficiency. As a result, the object possesses inadequacy. The justification reasons out in a judgment sense; however, it prescribes the adequateness predetermined by the appearances continuum to be defined as a priori (Husserl Ideas, p. 397). This leads us to infer, within the context of the continuum, that the appearance of something is not itself something. For instance, the insight that this infinity is intrinsically incapable of being given does not exclude but rather demands the transparent givenness of the Idea of this infinity (Husserl, 1983, p. 397), which states that the infinity is not itself infinity (Husserl, 1983, p. 398). It also implies that regardless of the criteria for the fulfillment of complete givenness to objectivity, what is given is the appearance of this objectivity. In other words, appearance serves with predetermined adequacy even when it consists of inadequateness or incompleteness of experiences: an a priori rule for the well-ordered infinities of inadequateness of experiences (Husserl, 1983, p. 398). If we observe this apprehension of objects closely from the phenomenological view, the constitutive knowledge representations are yielded by the fusion of concepts or ideas. In contrast, the ‘sense-intuition’ notions are the foundation of any knowledge (Williams, 2018). The ideas of reason are never given in intuition and always refer to the transcendental essence of things, intentionally. Similarly, the completed series of perspective variations cannot be given to intuition to serve as an a priori rule for inadequate givenness (Mohanty, 1954; Corazza, 2018).

Constitutive ideation—an intuitive fulfillment of what is required

Acts with the structure of fulfillment can have their origins in an individual’s intuitive history in constitutive ideation. It has been extensively discussed in scientific or cultural practices, demonstrating that every bit and piece of our knowledge, with its structure and fulfillment, is founded on the sensuous components of acts (Byrne, 2021; Picolas and Soueltzis, 2019; Sandler, 1987; Hopp, 2008b; Wright et al., 2003; Haaparanta, 1996).

Furthermore, certain varieties of individual objects, where the acts are found, have been distinguished as sensuous and straightforward perceptual intuition categories. That is, if the factual forms of the foundation are epistemic in nature, the evidence of belief is directly drawn from sensuous perceptual acts, and thus knowledge is gained in the ‘unity of the fulfillment acts’Footnote 9. On the other hand, if forms are non-epistemic, the sensuous perceptual experiences that are not directly involved in the evidence, then this calls into question the relevance of sensuous perceptual to epistemic inquiry. As a result, an intuitive awareness of the factual relations about the ‘evidence of belief’ would not be manifested within them without the interventions of object properties and propositions, which could be essential or contingent.

On the other hand, if forms are non-epistemic (or merely ontological) sensuous perceptual experiences that are not directly involved in the evidence. So, within them, without the interventions of object properties and propositions, which could be essential or contingentFootnote 10, an intuitive awareness of the factual relations about the ‘evidence of belief’ would not be manifested. Such factual relations do not depend on the evidence associated with an individual object. For example, if X does not have an intuitive awareness of the fact that redness is a contingent feature for a factual relation about the ‘objects qua relations’. In addition, if it was not aware in sensuous ways about the ‘redness’, merely the evidence about the rose’s color ‘red’ is associated with individual beliefs about individual red objects and is not grounded, concerning knowledge gain.

According to Kidd (2014), the evidence is founded intuitively on the unity of fulfillment acts, which should satisfy Husserl’s three prime conditionsFootnote 11 (see the notes), the levels of evidentiality that yield to the ‘apodicticity of evidence’, and thus constitute the ideation of self-evident knowledge (Husserl, 1983, Section 13, pp. 73–75; Husserl, 1977, Sections 3–6). Nevertheless, the factual relations about evidentiality would be ineffective in terms of what is determined and intuited in the given act. This raises the necessity that the evidential forms and knowledge-gain acts (aka knowing acts) be put together into one basket. So, it presents, collectively, the components of constitutive ideation in varied facets of knowledge at different levels of intuitive fulfillment, it is all founded on the synthesis of experiences.

Sensations, cognition, and inferences

Intentionality is concerned with the factual relationships between various objects in terms of their properties and propositions. So, strictly speaking, perceptual sensations are episodic and short-lived; they are mental events with a short-lived state rather than a knowing act. However, a knowing act among fulfillment acts, such as concentrating on something specific, i.e., inferential causes, behave as intentional; they are invariably factual relations belonging to the object’s properties and propositions, just when and insofar as they are inferred and cognized. As a result, inferences focus on acts associated with factual relations and object propositions, or their hood, rather than mere beliefs, and this is a critical law of the intentional process. According to this law, the simplest articulable sensation contains the relations and attributes of anything. An articulable sensation has the minimal structure of a noema, which necessitates a synthesis of founded and foundational acts. In our case, the inferences between pre- and post-thought were constituted intuitively by a series of intentionalandumFootnote 12experiential cues. Naturally, cognitive agents cannot describe or distinguish the intuitive constitution underlying the unity of fulfillment acts, because this is a synthesis process of acts that we call pre-thinking that has yet to be encountered and cognized. Forms of knowledge are the experiential-intentional processes and sensations that cognitive agents encounter and become constituted with the help of relations, propositions, and properties; Hegel defined this entire process as an objectification processFootnote 13.

Leaving aside the question of whether objects are constituent parts and object propositions are noema acts, which would necessitate the use of semantics. In mental states (perceptual or belief states), intentionality is a property of representations; that is, referring to an object with semantic notions regardless of mental state, such as spoken words in the air, text on paper, instrument reading, or software codes in computer programming, is taken to include intentionality.

Proponents argue that such referring states should not be regarded as external interventions during ideation. For example, “that is news in a paper” denotes an entity referring to the text hood or beings of “semantics” in a Paper; “that is a newspaper” articulates an occupant’s inferences, which is roughly equivalent to an “experiencer belief.” In the case of a non-experiential belief, this condition would not be treated as an intentional process, despite the fact that the dispositions presented, which also are formed by perceptions, other cognitive occurrences, and do maintain ideational continuity. Other mental states, such as representational arrangement in cognition, are also said to be intentional (Dretske, 1981; Fitch, 2008; Godfrey-Smith, 2004; Schlicht and Starzak, 2021). In the experiential-intentional process, inference indicates that X, whose objecthood is Xo, produces a disposition from the object-giving sourcesFootnote 14 that, when caused to bring about a rehearsal of X’s character, is an effort or another mental state whose objecthood is Xo. Whereas sensations, whose indications are not just about factual information, must be understood differently; that is, judgmental senses, too, have experience-directed intentionality. For example, mistaking a rope for a snake under certain worldly conditions means mistaking an object (Y) for X when it is X concerning facts, but the X-hood is part of that Y-hood. This stems from X’s previous experiences, which are directed toward the thoroughly real property of Y. Among the premises, though it does not exist in factual experience, ordinary experience insists on a snake nearby. Under normal epistemic conditions, this would become a memory disposition, prompting a rehearsal or recall for later remembering. In the specific conditions of an error-prone inference, however, this causes and fuses a Y-hood part of intentionality into current pseudo-factual information. A non-judgmental sense may be said to have mispositioned the direction of intentionality, resulting in Y-hood, which is not the case in reality. Nonetheless, it generates something (in terms of relations) that exists elsewhere in the lineup history of experiences, and the Y or X remains an object. Technically, the relationship between inferences and experiences varies depending on what is experienced and sensed. As such, the entire causality of having an object is merely a (quasi-)property of experiences, a relational property determined by the order of experiences. If it is simply a sensory experience of objects in the world, then the sensations are all the object-giving source entities, I repeat. Determinate intuitive awareness, according to this, is roughly equivalent to epistemically realized noesis acts and thus expressible. An individual’s intuitive awareness is made up of a series of non-(quasi-) experiential tokens, the types of which are specified by propositions of having an object and having in the mental content (beliefs or judicious); again, if it is not the realm of either first-order propositions or mere sensed data, the nature of experienced objects and their interdependence allow us to articulate them pragmatically. However, if and only if their systematic needs do not allow for pragmatization and introspection, they will be neither judicious nor non-judicious, and will be contentious even among intentionalists. Given this, an intuitive predicate ‘copula’ (is, to be, etc.) Footnote 15 in mental phenomena indicates the intentionality (what it is about) to be interpreted as intuitive awareness, for example, “The thing in front of me right now is a newspaper.” Speaking ontologically, the X-hood relation derives its structure from object properties (mostly representational). In this case, the X’s intuitive awareness affirms the individual experience as its object, and all relational properties are affirmed. Object-giving sources are, in principle, linked with acts of knowing, and thus all knowledge forms are related to experiential-intentional processes. For example, “that is a newspaper,” one would say intuitively and with their judgmental sense of having an object, and the object-giving sources are said to depend on experiences in one or more ways, including, to be sure, objectification. In this context, the objective complex experienced as something appearing as its kind is the X’s pervasion of an object from which it inherits its semantic nature, “text (news)-in-paper.” And since the inferential relations are direct, the inheritance relationship, or whatever the linking relationship (including correlation), must be included among the constitutive sources.

Inferential awareness—a noesis and noema synthesis

According to intentionalists, inferential awareness is the constituting source that results in judicious senses referring to various acts. And it is founded on skepticality, which allows the paradigm case of argumentation. Inferences are the conductors in this order, just as all experiences of objects or objecthood are relational to their directness or aboutness. For example, “that is not a newspaper,” because the objecthood (paperhood), as appeared differently in relation to “news on the paper,” explains the inferences concerning a pragmatic sense; however, the paradigm case argument is merely a fallacy when its inferential awareness leads to fallibility. Given this, within the acts, knowing acts would be the determiner of essential fulfillments in inferences. For instance, an individual being inferred an object (O) or its objecthood (Oo) as exhibiting one kind of property as fulfilled by another, like ‘paper’ is fulfilled by any other property (p); technically, in this case, the object ‘paper’ is a determiner and the property to be determined by its nature, like pragmatically. Such an act is said to be the fulfiller-act of inferential knowledge—with a focus on types of relations—and thus a memory is formed towards its pragmatic nature. In the standard scenario, the memory would have been the outcome of prior experiences with either positive or negative correlations blended at the operational level by diverse compositions of causal elements, logical stances, spatiotemporal relations, and propositions. In the experiential-intentional process, these correlations are referred to as polarities for judicious senses, where fulfillment allows for an asymmetric coupling as well. This is meant to say that the spatiotemporal relations do not necessarily influence bi-directional, as they are synergistically effective, especially in fulfillment (Boroditsky, 2011). Consider the following: Op1 is fulfilled by Op2, ergo there may be instances of the fulfiller (ø(Op2)) whenever the fulfilled (Op1) is not (Op1 —> Op2), but no instances of the fulfilled without the fulfillers. So, what has the fulfiller: has the determiner, for example, “what has a luminosity: has brightness.” The given stance is inclusive, which initiates a particular act that leads to inferential awareness, such as “the room has a luminosity,” which is equivalent to “the room is brighter.” Throughout this logic, relational fulfillment is the focus of ideation under the rubric premises of inferential awareness. This is to say, insofar as the nature of inferentiality is a causal factor in the correlation of constituting sources. In this sense, inductive support must be presumed for the proper formation of inferences, and the locus would be the property known to exhibit in both determiners and to be determined. For example, the determiner is the luminosity, and that property is to be determined as the result, i.e., the brightness; wherever luminosity is, there is brightness. It considers both the “property in the determiner” and the “property for determination.”

As mentioned, the premises of the experiential-intentional process for ideation are:

-

1.

The light is luminous (where the proposition is to be determined, the determiner is approved by the fulfiller (ø). This is called the “proposition” (P)).

-

2.

The light is luminous (where the object property is the determiner to be determined. This is called the logical stance (L)).

-

3.

‘What has luminosity, that has brightness’ (The general rule of this statement allows a grounding inference: what has the property that has the proposition.) like brightness, and unlike dusky or dim. (There is this inferential base, and this is called the “reference” generation for intuitive senses).

-

4.

This intuitive sense is likewise an application, an instance of the general rule for inferential knowledge.

-

5.

“Therefore, that light is luminous.” (This is the same information as judicious, and thus the proposition is determined. This is called “objectification” in a judicious sense; it is evidence or factual information. However, if it is unknown, then it stands in contradiction, as does the fact that there would not be any equally well-evidenced counter fulfiller).

According to this, any inferential assertion has three parts: a determiner ‘a’ that is approved by the fulfiller (ø) (part one: proposition, P). Because the same determiner ‘a’ is determined by the fulfiller (ø) (part two: a composition (logical stance, L)), a general rule of ‘reference’ between the determiner ‘a’ and to be determined ‘b’ would be (part three: La —> Pb). In this case, putatively experiential inferences are observed from the order of the terms in the inferential statement form: “This room is brighter because it is luminous, like the sun’s brightness.” Nevertheless, under these premises, we do not require a special logical signature to comprehend the inferences produced from experiences; But technically, they are indeed needed to understand their relationship within the intentional process, namely the correlation of acts. Therefore, I have employed a few expositional aids to allow the adequacy function to apply to every dimension of experience under the light of the intentionality law for ideation in the Husserlian phenomenological framework. In that function, to distinguish the categories, experiences are analyzed in terms of causal conjectures, relations, and logical stances. These distinctions are necessary for efficacy, and the set of other conditions together is sufficient, i.e., adequate; they are also crucial, as will be explained:

-

1.

Noema (M) (the determiner ‘a’ possesses the reason property (p) in the Noesis (S). And

-

2.

(p) (Sp —› Mp) (what has the ‘p’ property, that has the S property in Ma). Therefore,

-

3.

Sa (the fullfiler (ø), p, possesses S).

-

1.

Schematically, these are the functions of ideation w.r.t. a fulfillment—a fulfiller (ø), a determiner ‘a’, suggests a conditional relationship: if an inference is approved by ‘ø’, then an S determiner ‘a’ is an intuitive property. If an object is luminous, then it is also brighter because there is a general relationship captured by a universally determined condition between luminousness and brightness. Whatever possesses the one has the other too—as stated by intentionalists who are not concerned with relations between sentences or propositions but with property-possession standing stead for the copula, especially in a judicious sense of experiences. Such reasoning instances comprise an inductive procedure, which is a method of discerning the pervasiveness of experiences through knowing or examining them. Similar instances are known to exhibit the fulfiller and thus should also, at least in one case, exhibit the determiner ‘a’ possessing property (e.g., Ma and Sa); and dissimilar instances are known not to exhibit the fulfiller and, as a result, should lack the determiner, too (e.g., -Sa and -Ma).

Precedence causality can be irrelevant to manipulation

Preceding conditions are regulative, where the causes can be identified in explaining varieties of experiences in intentional processes. A causal condition that is necessary for the emergence of an effect. And it necessarily amounts to no effect arising without being preceded by a causal condition, so the causal condition cannot be counted as “irrelevant.” For instance, the precedence is irrelevant to an inference that just happens to always be used to bring out the pulp from a particular kind of paper; therefore, the inference is not regulatory. In this case, the presence of an effect, in sum, entails the prior occurrence of all its true (non-irrelevant) causal conditions. The presence of one such cause, however, does not entail the occurrence of other effects. The other conditions may well be necessary too, as they typically are. For example, the presence of luminosity implies the presence of brightness, which is a necessary condition. However, if the luminosity producer is covered with a non-reflective absorbent, it might also be dim or darkish. As a result, it does not imply luminosity. Here, we are not talking about sufficient (adequate) causality—about a set of causal conditions whose being in place unfailingly brings about an effect of a particular type. Whereas the necessary causal conditions are formulated on top of the only necessary factors and not an entire set of causal conditions, especially in the case of correlations; however, in traditional inferential knowledge theories, these necessary causal conditions are considered instrumental causes, which are distinguished from two other types: inherentFootnote 16 and emergentFootnote 17 causes (Esfeld, 2011; Williford, 2013). In addition to the instrumental, these are sometimes said to be the preeminent senses of causation, as they reflect their appearances in ordinary usage. Does this concept have the efficacy of inferential knowledge, although commentators may disagree about this? In my opinion, inferential knowledge is distinct in nature: it incorporates sensations, perceptions, and casual conditions, yet it also encompasses various other operational compositions as interventions in a judicious sense. Therefore, inferential knowledge should not be taken as it is; there must be an absolute minimum factor prior to its effectiveness. Within the object-giving sources, there exists a perception that the constituent possesses a form of “operational employment.” In essence, the instrumental cause occupies an intermediary position. To illustrate, the act of marking paper necessitates the operational employment of a pen. Consequently, the instrumental cause is sometimes utilized in a pragmatic sense, indicating its relative intervention. Therefore, it is more closely linked to proximity rather than being an absolute cause. It is important to note that the causal conditions have been implemented as interventions at an operational level, and their causal relevance within a set of necessary conditions is determined by what is necessary for an inference. For instance, the properties of paper collectively are enough to produce an effect. However, the operational cause of paper receives special attention due to its pragmatic nature, specifically its usage or purpose in the context of a newspaper. Upon encountering a Newspaper, the effect is further intensified by the presence of nearby proximity, which combines with a multitude of pre-existing enabling conditions. This resultant effect is inevitable. Likewise, various emerging causes are frequently subject to controversy, particularly in situations where the precise determination of essential factors is crucial. Furthermore, the process of ideation, such as representing an object as a paper with distinct causes compared to the same object represented as a substance (news), raises questions regarding the status of causality. These questions remain unanswered in terms of epistemic fulfillment within the boundaries of an individual’s experience. Our comprehension of the causal status of evidentiality can be deemed suitable for achieving epistemic fulfillment. This notion suggests that evidence is built upon a foundation of experiences. However, it is necessary to consider whether this applies to all levels of ideation, including intuitive, imaginative, and empirical. In other words, what is the relationship between the various sources that constitute ideation and sensuous experiences, in accordance with the law of intentionality? Therefore, it is important to provide evidence that supports the perspective of everyday objects as experiences and a causal understanding of how we learn about them.

“Experientialism” is what shall be used

“Constituting sources,” the most important three of which are perception, inference, and assertion, reveal objects that do not exist independently of experiences but are also causes or effects of them. Furthermore, there are the subvarieties of these source(s) that operate within specific boundaries, along with the fourth source: intentionality, allowing no restrictions to the ideational process. It is important to note that all these sources are part of the causal web of ideation and are considered natural processes. Their evidence can be identified through introspection from a first-person perspective, as the judgmental sense originated. This allows for an understanding of the origin of these sources. However, when it is presented from an ideational standpoint, it is crucial to recognize that these sources are inherent intentional processes that are shared by all individuals who engage in inference and perception. An ideation, irrespective of its origin, encounters a fact or, more properly, an object along with its propositions, and behind it can be experiences that are derived causally. For instance, when a cloud collation produces a luminous experience, mistaking light for thunder in a sky where there is luminous light, this ideation is not accidentally generated but rather a genuine perception of the object. The pseudo-inferential awareness of the luminous nature resulting from the observation of thunderlight, although ideational, is an experiential consequence that implies intentional activity. This experiential-intentional process is typically explained through a relationship from experience to object that is independent of the constitutive sources of ideationFootnote 18. This relationship, known as having an object from the perspective of the experience and having an object load from the perspective of the experiencer, can be embraced as a theory of ideation for the emergence of knowledge.

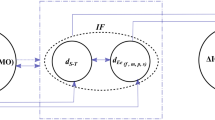

Constituting sources are characterized by an ideational logic and are commonly regarded as object-giving sources. Consequently, they are typically interpreted as infallible. This contrasts with optical instances, where a Cartesian perspective acknowledges the possibility of fallibility as constituting sources do not, in a judgmental sense. Such that an object-giving source is embedded with intentional processes, while the outcome, as an experiential-intentional process, is inherently judgmental and distinct from a pseudo-inferential process, even though individuals may perceive it as pure-judgmental when it occurs. It is important to note that pseudo-inferentiality does not qualify as an object-giving source, as it involves misinterpreting a rope as a snake, which is not strictly inferential but rather pseudo-inferential. To be considered an object-giving source, the experiential-intentional processes, identified as correlational constituting sources, must function flawlessly in conjunction with compulsive interventions. These interventions encompass various factors such as the environment, sensory function, and inferential activity as a causative process. Notably, the object-giving source is suitably positioned in the causal chain or composite of causative elements that results in its being experienced. In the context of the ideation theory for knowledge emergence, if the issue of constituting source individuation arises, it becomes pertinent to explore the various types of experiential-intentional processes that are salient. Additionally, understanding the phenomenological characteristics such as bliss and grief requires an investigation into how we acquire knowledge about them. Furthermore, it is important to determine whether there exists a distinct source of object-giving for absentia (inferential) awareness and whether such postulation serves as a different object-giving source compared to constitutive sources. These inquiries and others have the potential to disrupt the ideation process, which heavily relies on observable source types. The central argument of this thesis posits that experiential-intentional processes can be categorized into ‘groups’ based on their outcomes, and object-giving sources can be classified as ‘types’. And, given the conditions of this, the remaining subtypes will be identified, including but not limited to absentia awareness and other experiences that are not in those ‘groups and types’ that are contingent upon what they are about their objects, or their propositions or objecthood.

As explored in previous sections, the alignment of experiences with their sources has epistemic consequences, as it allows for the possibility of experiencing an object with its inherent characteristics and its relationship to a certain outcome. This alignment is made possible by the propositions associated with the object, but the recognition of objecthood depends on the level of inferential awareness. In other words, inferring an object from what is known as an object-giving source becomes correlated with a constituent that determines the ways in which objecthood can be known to be true. However, it is important to note that historically, the constituents took the position that inference from the success of later intentions, which is a form of correspondence in terms of correlational activity, proceeds. The object propositions are implied but not explicitly acknowledged. This procedure may appear to be self-constraint, but it is not. Once a type of constituent, as recognized by its propositions and its objecthood has been correlated with it, a later constituent known to be a token of the type becomes correlated as well. In debates, attempting to prove what is already known is criticized. If the ideation focuses on the first order of experiential occurrences, assuming that the mental apparatus for prompting the later intentions is known to be “dispositions” or “memory impressions,” which are properly formed only by their constituents, then it can be considered ideational. However, it is important to note that the order of experiences is serial, and these experiences fall into types, i.e., can be categorized. This categorization may lead to skepticism if there are no new constituents added to the process of ideation. Therefore, inferences, or the awareness of ideation, play a crucial role in understanding and grasping object propositions. These inferences can occur with the involvement of later intentions. On the other hand, the operation of a constituting source implicitly provides a non-inferential justification when inferring an object as it is, which is referred to as unawareness justification. However, it is essential to recognize that the inference is not solely about the judgmental sense of objecthood. Instead, it involves the meta-level inference of the judgmental sense of objecthood. In simpler terms, ideation itself does not require a judgmental sense, as suggested by correlation theories (Nikolić, 2016; Peres, 2017; Płotka, 2020). These theories argue that ideation does not necessarily involve awareness of justification. But it does require a proper correlation between objecthood and propositions, which equates to an apprehension of the object-giving sourcesFootnote 19. If objects form a “memory impression” based on certain types of experiences, they may appear to exist independently. These objects are shaped as mental representations that lead to articulation in speech acts, including language. The prime and original source in this case is experience, which plays a crucial role in inferentiality. Inferentiality heavily relies on acts in the experiential-intentional process, where awareness of something arises from a qualifying object coupled to the sensory. For example, inferring that a bird named Raven is a crow due to categorial intuitive awareness narrows down to the object-giving sourceFootnote 20, which is a type of experiential-intentional process. Inferences about commitment to entities that cause its content have led to an acceptance of fallibilism regarding all varieties of emotional experiences, including biases. While the constitutive sources are seen as infallible, a subject may have a different experience that appears to be inferential from a first-person perspective.

However, in-reality, it is non-ideational and simply pseudo-inferential. Except in certain cases of apperception or an encompassing unity of object propositions, the presence of an object in the pseudo-inferential processes of objecthood implies that the possibility of deception about the object cannot be eliminated. Apperception with the immediacy of previous experience is intrinsic and fully accessible to experiencers without an essential direct causative process. However, other types of experiences for object-giving sources exist independently of the judgmental sense as causes and objects of distinct sources’ truth-hitting mental representations, and they are extrinsic to the experiencer’s awareness. In addition, if the propositions hold the permissible properties, it is possible for a few objects on any given occasion to go unrecognized. In such cases, most objects are not accessible to direct ideation, or at least some aspects may not be objectively verifiable. This transcendental nature of ideation leads to the embrace of ideational fallibilism. It should be noted that the entire range of experiences is not inherently focused on facts, as their normal nature is to be appreciative unless there is an intentional process that acts differently. However, there are instances where a non-apperceptive process does not occur without any evidential disruption, and this can be attributed to intentional intervention. This intentional intervention may align with ideational fallibilism, but it is not solely due to inferences. Instead, it is influenced by the nature of the justification process. From an epistemic perspective, certain virtues play a significant role in shaping the ideational process, namely dogmatism and the desire to know (McCraw, 2022). The absence of these virtues in sources that provide information can lead to deficiencies in knowledge and hinder the establishment of leases. To ensure the validity of inferences, the immediacy of inferential acts should be justified by the pervasiveness of objecthood and object propositions. The correlation between propositions and objecthood supports the pervasiveness of objecthood, while non-objecthood and non-propositions of the given object indicate negative correlations. However, it is important to note that epistemic virtues operate with causal relevance, and thus objecthood and propositions are key factors in causality and the constituting sourcesFootnote 21.

Experiential episteme is situated and transcendental

Tassone (2017) has critiqued certain models of justification and knowledge, focusing on the epistemic conditions that are involved in truth-claimed relations within subjective beliefs. Tassone (2017) argues that subjectivism plays a significant role in establishing justified true claims for knowledge (Tassone, 2017; David, 1999). In order to achieve objectivity in justification, it is necessary to rely on our senses and perception to gain epistemic access to evidence. This requires a careful analysis of the structural components of mental states that offer epistemic access to evidence for the justification of beliefs. Ultimately, this highlights the importance of a self-transcending ground for determining knowledge about the world in modern epistemological approaches. This understanding emphasizes the essential structures posed by intentional objects along modes of givenness, which afford transcendence for meaning and knowledge. Access to evidence is contingent upon the epistemic connection between intuitions for direct awareness of objects within the realm of experience. Nevertheless, it is worth considering that empiricist ideas (Murphy, 1980, p. 90; Husserl LI, II, vol. 1, Section 21) could potentially be reducible into natural categories or analogous to familiar containers employed for the retention of ideas.

Accessing the world to achieve direct access to both physical and non-physical structures of perceptual experiences is essential for the act of knowing. This direct access eliminates external causal factors and allows subjective experiences to turn into objective categories of knowledge. However, it is important to consider how physical and non-physical objects are presented by their nature in perspective acts and whether they are necessarily incomplete or considerably non-objectual. For instance, if a cushioned chair appears from a specific perspective, the minutiae are usually undisclosed to visibility by virtue, and the internal structure of the cushioning cannot be seen unless the outer structure is opened-up. Similarly, in the case of mental objects such as concepts and ideas, higher-order categorical experiences are given adequacy and apodictic evidence. Therefore, thinking about the chair as an object with properties presented in a spatiotemporal frame is an a priori feature of the perceptual structure.

Apart from the perceptual properties of existence, certain internal factors within the structure of perceptual acts are essential in determining the justification of asserting ‘the chair is on the floor’. Within this context, the concept of mental acts becomes crucial as it enables us to perceive and understand both the intuitive and qualitative aspects of an object. Through a transformation of qualities into functions (Husserl LI, I, vol. 1, Sections 11–13), we gain insights into the object’s existence and its spatial position, thereby allowing us to establish the validity of the justification. In contrast, the privately accessible situation of affairs (Sachlage), such as the example of ‘the chair is on the floor’, can be perceived differently by individuals in different circumstances. These varying perceptions contribute to the establishment and validation (constitute and justify) of the same ‘state of affairs’ as either true or false (Husserl LI, I, vol. 1, Sections 11–13). This distinction in mental acts highlights the importance of differentiating (an essential sense of distinction) between truth-stating and truth-making, as well as between the intuitive (propositional content) and the significative (world-dependent factors). These reflections represent knowledge at different levels and serve to establish relationships based on truth-claims (Husserl LI, pp. 244–246). They differentiate the understanding of meaning in judgments from the representational content, with the objectifying acts serving as internal conditions for both the creation and expression of meaning or making and stating the meanings. This distinctionFootnote 22 is particularly significant when connecting meaning to referential or intended objects (Husserl LI, VI, vol. 2, Section 4, Section 25, Section 44). Rather than assigning an exclusive epistemological role to the subjectively experienced content or the mental existence of transcendental objects, a correlational condition can be affirmed between signitive (significative) and intuitive acts. These acts are (a) part of the stream of consciousness and are (b) adequately or nearly adequately given. This implies a fulfillment structure founded on intuitiveness for both the experienced and transcendental content. Constitutive ideation represents an intuitive fulfillment of the essential structural notions that serve as objective references for meaning and truth-claimed relations. This comprehension of semantics, however, presents a certain ambiguity in the ontological status of purely transcendental objects.

Conclusion

In previous sections, the arguments underlying Husserl’s critique of intuitively grasped objects have been examined from the perspective of first-order constituents: subjective experiences, inferences, and awareness. The question at hand is whether these arguments are simply a rehashing of old ideas presented in a new form. The perspective presented here distinguishes between immanent beings that are inherently present and the possibility of a transcendent being as a thing. However, this transcendent being is perceived through a transcendental lens that varies depending on the observer’s perspective in their first-order awareness. This perspective is significant in that it emphasizes the importance of understanding the observer’s perspective in perceiving the transcendent being. Furthermore, it aligns with the functionalist thought of idealistic faith, which requires knowledge of the natural world from a macro perspective and can be seen as a causal manipulation of the mental state. Phenomenological studies argue that most idealistic faith is charged with self-knowledge is non-relevant due to the lack of awareness regarding the absolute nature of objects. This perspective introduces a fresh viewpoint that highlights the limitations of idealistic views and emphasizes the significance of comprehending the observer’s perspective in perceiving the transcendent being. Conversely, scholars who have examined eidetic memory propose that all our actual experiences extend beyond themselves, aiming to acquire new possible experiences. By considering eidetic memory studies, it becomes apparent that the observer’s real-world is the manifestation of one among infinite possibilities. Consequently, it is plausible that the existence of non-existent entities is not accidental, implying that the transformation of non-objectual experiences into objectual experiences is also not accidental. Instead, it can be understood as a cognitive process within our faculties, specifically a synthesis of noesis-noema and other varieties of acts, or a correlation among the constituents as they mutually share each relevant thing. The question then arises in the case of first-order constituents as to whether such ‘things’ belong to more than one possible constituent, given that ‘things’ are intended as internal and private elements of them, which Husserl calls ‘phenomenological transcendental reflections’. The principle of phenomenological study is not to be determined by how the intentional analysis of such immanent experience should be a matter of correlation nor to have a naive assertion of things. However, the elaboration of this principle is undertaken by the phenomenologist, who admits a very significant concession about the phenomenological sphere.

In conclusion, Husserl’s critique of intuitively grasped objects from a first-order perspective is a new argument that challenges the idealistic faith charged with self-knowledge. Eidetic memory studies suggest that the real world is the manifestation of one among infinite possibilities, and the transformation of non-objectual experiences to objectual experiences is not accidental but rather a process within cognitive faculties, i.e., a noema-noetic synthesis. The principle of phenomenological study is not to be determined by how the intentional analysis of such immanent experience should be the subject matter nor to have a naive assertion of things. However, the elaboration of this principle is undertaken by the phenomenologist, who admits a very significant concession about the phenomenological sphere in the experiential-intentional process.

Notes

According to Husserl, “phenomenology is not a deductive discipline but a descriptive discipline, for which reason Husserl explicitly states the transcendental analysis carried out by phenomenological reductions are necessarily incomplete, so their capacity to ad infinitum need to be progresse” (Zahavi, 2003, p. 197).

In the initial phase, an individual engages in reflective practice, periodically pausing to recognize the necessity for transformation. This stage does not aim to predict future events or formulate strategies for them. Instead, it explores and describes the potentialities and contemplates our potential responses to them. This informal process does not necessitate any structured activities; rather, it serves as a precursor to ideation. Operating under a hypothetical condition of ‘what if…?’, it facilitates a comprehensive reevaluation of deeply ingrained assumptions from various perspectives, thereby diminishing uncertainty during the ideation process.

“It is an awareness we have before we do any reflecting on our experience (Gallagher, and Zahavi, 2008)”.

Mental processes encompass a combination of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral components. Each component encompasses specific operational or functional elements. The emotional components pertain to our feelings and desires, including emotions such as anger, fear, anxiety, rage, sadness, happiness, and jealousy. The cognitive components involve our thoughts and imagination, giving rise to conceptual notions such as ideas, memories, and intelligence. Lastly, the behavioral components involve the interactions between our actions and behaviors, relying on the relationships influenced by each action, such as reading, writing, talking, playing, and more.

As Descartes’s meditations on a first philosophy describe fallibilism as a view in epistemology doctrine, “it is an account devoted to studying knowledge valuablesim states that no belief can ever be rationally supported or justified conclusively; always there remains a possible doubt as to the truth of the belief […]. Never experienced anything like that yourself…perhaps you are experiencing such a thing for the first time. [.…]. This may sound far-fetched because, well, it is, but that’s not the point. The question we are exploring is whether we can know anything with absolute certainty or if fallibilism is correct, and it is always possible to some extent that our beliefs are wrong no matter what they are” (Boghossian, 2007, pp. 111–128).

Epistemic beliefs are processed by cognitive faculties in a manner that is relatively non-inferential or founded, owing to the presence of truth conditions that provide justification. It is noteworthy that cognitive faculties would generate such beliefs even in the absence of truth conditions, resulting in unjustified beliefs. However, the genetic fallacy suggests that the proximity of knowledge proportions originating from our own beliefs may fail to acknowledge the possibility of justified grounds for holding necessary truth conditions. The responses from epistemic beliefs may mistakenly overlook the distinction between propositional and doxastically justified beliefs, which is subtle and determines the objectivity of propositionally justified beliefs, even if they are not doxastically justified.

The functionality of objectual and non-objectual varies.

In order to identify a referent, it is crucial to consider the functional, structural, material, and qualitative aspects of an object, much like the conscious act (noesis) of perceiving a table. The intervention of these aspects within a given situation results in a shared essence of properties between self-perception and the state of affairs, ultimately leading to a mutable relationship that allows for the identification of the referent.

The integration or synthesis of fulfillment acts is a crucial aspect of both scientific and philosophical thought, as it seeks to capture the mental representations of experiences in cognition. For example, the representation of visual experiences for each spatial pattern can be likened to a snapshot, with each burst serving to represent the substance that it is correlated with. The pattern or relation, on the other hand, is akin to a search, with its essence symbolizing the presence or absence of the substances that the system is seeking. Such interpretations prompt us to examine the function of features and the causal impact of stimuli on the experiencer and to seek a reflection of the environment within by correlating the features of the stimuli with interventional activity. In this context, the propositions arising from experiences and fulfillment acts signify a cyclical or rhythmic quality in certain cognitive processes, such as attention, perception, and memory. Furthermore, the concept of unification, which refers to the synthesis of two or more processes or acts, provides insight into how the essence and interventions interact with the external world. While individual experiences are joint activities, much like a dance performance, they can synthesize physical, psychological, and phenomenal representations, establishing a stronger ideational bond that enhances performance.

This terminology, which can be traced back to Aristotle and was later revised by Kripke in his modal logic (Robertson and Philip, 2020), encompasses opposing pairs: essential versus accidental and contingent versus necessary. These distinctions, which are prevalent in modern discussions of truth claims and relations, are established by applying various features to object properties or propositions. For example, essential features are attributed to object properties that define their essence and are indispensable to their existence, while accidental features are incidental and not essential. Similarly, contingent features are characterized by their availability in certain possible contexts but not in others, without being either necessary or impossible. While the essential versus accidental distinction is typically applied to properties, the contingent versus necessary distinction pertains to propositions. However, it is important to note that essentials can also be contingent, but only if the object itself is contingent.

Firstly, the intuitive givenness of an object is entirely adequate, as each aspect of it is precisely as intended. Secondly, since the object is inconceivable and is intuited and intended in the acts, the evidence of belief in it is indefeasible. Lastly, the final level, which fulfills both the first and second conditions, is not conditionally certain due to the absence of sufficient fulfillment (Kidd, 2014).

In analytical philosophy, this notion is roughly equivalent to Husserl’s noema, “as there is certainly no valid move from describing something as an intentional object to describing it as an object in some of the other philosophical senses—as existent, complete, concrete, or whatever—but suppose to carry properties or relations which enable to describe the object” (McGinn, 2004, p. 221).

The process of objectification is intentionally designed to be intentionalandum. This implies that the core facts and factual relationships of the noema acts are recognized and comprehended from the sources that constitute the prior authentic experiences, thereby fostering transitional ideation. For example, linguistic specimens such as hymns, dialects, and cognates were gradually collected from causal interactions and analyzed, not only for their semantics or intended messages but also to ascertain their relationships (spatiotemporal, etc.) and their beingness (hood). The historical content that is no longer in existence and has been reconstructed is the relationships between the concerned inferences (or how one emerged into the other).

Object-giving sources encompass a wide range of experiential awareness and remembering. These sources involve various types of acts that create new representations within the experiential-intentional process, with the new information complementing the existing information that is readily accessible through remembering. Consequently, these acts are rooted in different sources of generated information, as cognitive events involve an assimilation process that characterizes newly acquired information based on fulfillment relations. Although explicit awareness of past experiences is not necessary for cognition, a cognitive event pertaining to something from the past is considered a memory. Therefore, awareness in experiential-intentional process is causally linked to both physical and psychological realities, as it encompasses empirically, perceptually, imaginatively, or sensually generated information. In contrast, psychological properties are mediated by imaginary boundaries and are perceived through an imaginative connection.

The operators that establish a correlation between two expressions are commonly comprehended.

The substratum is an essential component of the superstratum, with an inherent connection between the two. For instance, A serves as an inherent cause for A-hood, where the fundamental cause of a fabric lies in the threads that form its structure. It is important to acknowledge that intrinsic causes are not limited to substances alone, as universals also exist in qualities and motions, in addition to substances. Consequently, a feeling can be considered a quality, with its inherent cause being an individual self. This feeling serves as an inherent cause for universal sensation-hood, which encompasses numerous inherent causes, encompassing all sensations within the universe.

The emergent cause of a particular attribute, such as the blueness of a piece of paper, can be understood as a property that arises from the inherent nature of its constituent parts. This emergent cause is considered a property in itself, as it is an integral part of the whole. In the case of the blueness of the paper, it is the blue color of its pulp that serves as the emergent cause.

During the ideation process, it is not possible to have an intuitive awareness of the ideal objectives without completing the process. From a phenomenological perspective, ideation is not just about perceiving an object; it involves drawing intuitive knowledge from empirical awareness during the constitutive ideation and then being exposed to different perspectives, which leads to a synthetic perception of the pure essence or eidos.

The correlative consideration in this context is based on perceptual or inferential awareness, without any concern for judgmental sense. It refers to experiences that involve instances, events, or situations that cannot be relied upon due to their similarity to previous occurrences. These experiences are reinforced by constant streams of feedback from those occurrences, such as the realization that it is not advisable to jump into an unknown lake or to solely rely on vision while driving in low visibility conditions. However, the focus of interest lies in judgmental senses that are intentionally judgmental, as they can be invoked to resolve skeptical inquiries and address the deep concerns of skeptics. This requires a justification process that is not only intended but also arrives at a righteous justification. The thesis aims to specify the connections between experiences and ideational processes in the science of constituting true sources. In cases of skepticism or dispute, correlations and methods can be employed to resolve them. Inferences and justifications play a crucial role in this process, as they are not only important but also thematic. When faced with dogma, disagreement, conflict, or preference, referring to constituting sources is the most effective way to find a resolution. Intention regarding an identified fourth source elevates the level of knowledge and introduces more complex conditions for dogma and disagreement. It is important to note that knowledge, although coupled with intentions, is inherently inferential, just like the awareness and particular relations of constituents. These constituents become stronger through verification to ensure their factual nature. Without this verification, knowledge may transform into beliefs. There is a larger group of externalists who drive their epistemological perspectives based on objecthood (Brandt, 2020).

It shows inseparably linked stakes among the ontological and epistemological relations: it is about the intuitive givenness of ideal objects on the one hand and the ontological distinction between sensuous and ideal entities on the other. This analysis shows an encompassing unity of all elements: a synthesis of signitive and intuitive intentional acts, sensuous and categorial intuitions, acts of thought, and acts of language (Bernet, 1988).

The legitimacy of propositions lies in epistemology, which must provide a reason for believing them. Lack of experience or the inability to explain knowledge does not necessarily lead to mistrust. Ideational experiences accompany knowledge originating from object-giving sources, even if the individual is not attentive to the facts. However, disagreements can lead to convictions and preferences. Therefore, understanding object-giving sources and epistemic virtues is crucial in resolving problems, preserving confidence, reducing skepticality, and preventing disagreements.

The conditions that hold significant and intuitive value can be found in both sensuous and categorial intuitions.

References

Alston WP (2005) Beyond “Justification”: dimensions of epistemic evaluation. Cornell University Press

Audi R (2001) The architecture of reason. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Berghofer P (2019) Husserl’s noetics—towards a phenomenological epistemology. J Br Soc Phenomenol 50(2):120–138

Bernet R (1988) Perception, categorical intuition, and Truth in Husserl’s Sixth ‘Logical Investigation’. In: Sallis JC, Moneta G, Taminiaux J (eds.) The collegium phaenomenologicum, The first ten years phaenomenologica, vol 105. Springer, Dordrecht

Boroditsky L (2011). How languages construct time. In Space, time and number in the brain (pp. 333–341). Academic Press

Boghossian P (2007) Fear of knowledge: against relativism and constructivism. Clarendon Press

Brandt PA (2020) Cognitive semiotics: signs, mind, and meaning. Bloomsbury Publishing

Byrne T (2021) Husserl’s theory of signitive and empty intentions in logical investigations and its revisions: meaning intentions and perceptions. J Br Soc Phenomenol 52(1):16–32

Corazza E (2018) Identity, doxastic co-indexation, and Frege’s puzzle. Intercult Pragmat 15(2):271–90

David C (1999) The paradox of subjectivity: the self in the transcendental tradition. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Dretske F (1981) Knowledge and the flow of information. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Esfeld M (2011) Causal properties and conservative reduction. Philos Nat 42–43:9–31

Fitch WT (2008) Nano-intentionality: a defense of intrinsic intentionality. Biol Philos 23:157–177

Føllesdal D (1988) Husserl on evidence and justification. In: Sokolowski Robert (Ed.) Edmund Husserl and the phenomenological tradition. The Catholic University of America Press, Washington

Fumerton R (2006) Epistemic Internalism, Philosophical Assurance and the Skeptical Predicament. In: Crisp TM, Davidson M, Vander Laan D (eds) Knowledge and reality., vol 103. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-4733-9_8

Gallagher S, Zahavi D (2008) The phenomenological mind: an introduction to philosophy of mind and cognitive science. Taylor and Francis, New York, NY

Godfrey-Smith P (2004). On folk psychology and mental representation. In Representation in mind (pp. 147–162). Elsevier

Haaparanta L (1996) The model of geometry in logic and phenomenology. Philos Sci 1(2):1–14

Hopp W (2008a) Husserl on sensation, perception, and interpretation. Can J Philos 38(2):219–245

Hopp W (2008b) Husserl, phenomenology, and foundationalism. Inquiry 51(2):194–216

Howard-Snyder D (2005) Foundationalism and arbitrariness. Pac Philos Q 86:18–24

Husserl E (1969) Formal and transcendental logic (trans: Cairns D) Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague. In: Janssen P (ed) Formale und transzendentale Logik. Husserliana vol XVII. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, 1974

Husserl E [1970] (2001) Logical investigations, two volumes (trans: Findlay JN) (Latest edition with a new preface by Michael Dummet and introduction by Dermot Moran). Routledge (cf: Husserl LI)

Husserl E (1983) Ideas pertaining to a pure phenomenology and to a phenomenological philosophy: first book: general introduction to a pure phenomenology (trans: Kersten F). Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston, [1913]

Husserl E (1977) Cartesian meditations, translated by D. Cairns. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, [1929–1960] sections 3, 6, 12, and 27

Kidd C (2014) Husserl’s phenomenological theory of intuition. In: Osbeck L, Held B (Eds.) Rational intuition: philosophical roots, scientific investigations. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 131–150

McCraw B (2022) Epistemic virtues. Oxford University Press

McGinn C (2004) Consciousness and its objects. Oxford University Press

Mohanty JN (1954, 2003) The ‘object’ in Husserl’s phenomenology J Philos Phenomenol Res 14(3):343–353