Abstract

This study analyzes the impact of four dimensions on Generation Z’s intentions to work in the tourism industry in their hometown of Antequera (Malaga, Spain) within the specific tourism context of World Heritage Sites (WHSs). We estimate the influence of young residents’ perceptions toward tourism development through WHS recognition, community involvement, and place attachment on this variable, following the theory of planned behavior (TPB). A structural equation model based on variance by partial least squares, PLS-SEM, has been proposed. The results show that Generation Z’s community involvement, place attachment, and positive perceptions toward tourism development directly influence their intentions to work in their WHS hometown; meanwhile, the negative perceptions toward tourism development have no direct impact on these intentions to work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the relevant challenges facing the tourism industry today is having a qualified and stable workforce (Goh and Okumus, 2020). Within this context, some authors consider that the sector is experiencing an exceptionally complex situation they call “the perfect storm” due to the high level of labor dependence on youth tourism. A considerable percentage of experienced workers retire as young people enter the industry. This new generation holds the foreseeable future of this vital sector in their hands, especially in terms of the global economy and development (Solnet et al., 2016).

However, the percentage of workers under the age of 25 in the tourism and hospitality industry in Spain (10.7%), according to the National Statistical Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2020), is considerably lower than the average in Europe (19.6%) and much lower than countries like the United States (33.1%) or Australia (43%) (Hotels, Restaurants, Bars, and Cafes in Europe [HOTREC], 2019). This percentage will likely increase in the coming years, due to the higher age of retirement in Spain, which seems to signal that the storm will be even more relevant with this new generation. Additionally, recent studies indicate that many young people, even those that have studied tourism, have tried to find work in a different sector (Duman et al., 2006; Solnet et al., 2012). Along these lines, Innerhofer et al. (2022) indicates the low absorption rate of tourism graduates.

What are the reasons behind Spanish youth’s lack of intentions to work in the tourism industry in their WHS hometown? To answer this question, this study considers the impact of four dimensions on young people’s intentions to work in the tourism industry, which is of great interest in the scientific literature. The four dimensions are residents’ positive perceptions of tourism development through WHS consideration, residents’ negative perceptions of tourism development through WHS consideration, community involvement, and place attachment.

The influence of residents’ positive and negative perceptions of tourism on young people’s intentions to work in tourism has been extensively studied in the literature (Goh and Lee, 2018; Gursoy et al., 2019). However, perceptions regarding the development of tourism through the consideration of WHSs have not been sufficiently analyzed for this age group. Other variables, such as place attachment and community involvement, have been studied as antecedents of intentions to work in the hometown although not in the tourism industry (Beccaria et al., 2021; Larkins et al., 2015). Moreover, both variables are closely related to positive and negative perceptions of tourism (Chi et al., 2017). However, the influence of community involvement and place attachment on young residents’ intentions to work in tourism in their WHS hometown has not been specifically analyzed by academia.

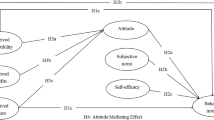

Our research, based on TPB, analyzes the influence of these factors (positive and negative perceptions of tourism development through WHS consideration, place attachment, and community involvement) on their intentions to work in the tourism industry in their WHS hometown.

We also consider it relevant to analyze these relationships within the specific tourism context of a WHS. This study is specifically situated at the “Antequera Dolmens Site,” which was first recognized as a WHS on July 15, 2016, the turning point for the region’s tourism industry. Considerations regarding the context of COVID-19 were not included in the survey since it was validated in January 2020, and data was first gathered in February 2020, when Spain still did not have any pandemic-related restrictions in place.

The paper is organized as follows: the second section presents the theoretical background of the research; section 3 describes the research design, variables, data collection, and data analysis method; section 4 provides the empirical results and a discussion on the main findings; and the last section includes conclusions, limitations, and future research.

Literature review and hypotheses

Theoretical framework: theory of planned behavior

This study is based on the TPB (Ajzen, 1991). Although this theory has been used in the tourism industry for analysis and travelers’ decision-making processes prior to visiting a tourist destination (Zheng et al., 2022), it has not been used academically for the behavioral study of young people’s decisions whether or not to work in the tourism industry.

According to this theory, behaviors are a function of three basic factors: those of a personal nature (attitude), those that reflect social influence (subjective norms), and those that reflect anticipated difficulties (perceived behavioral control). In our study, the behavior we measure is young people’s intentions to work in the tourism industry in their WHS hometown. Attitudinal factors are positive perceptions toward tourism development through WHS consideration and place attachment. We analyze the subjective norms through the community involvement of Generation Z. In this study, perceived behavioral control factors are given by negative perceptions toward tourism.

In order to increase the predictive capacity of the TPB, various authors have added variables to the model (Ahmmadi et al., 2021). We attempt to expand the theory in our study by analyzing a new behavioral domain (young people’s intentions to work in the tourism industry) through new factors such as those discussed above.

Generation Z and their intentions to work in their hometown

From a human resources perspective, the management, attraction, and retention of talent, especially among young people, has become a serious problem for the tourism sector (Solnet et al., 2016). This issue has been analyzed from different perspectives. Some authors emphasize the concept of meaningful work as an innovative formula in the accommodation industry (Tan et al., 2019). Others are concerned about talent management and the sense of exclusion among hotel employees (Kichuk et al., 2019). However, there are few specific studies on Generation Z entering the tourism labor market.

The generational theory distinguishes the population by age, where each interval includes all the people born in a certain 20-year period (Betz, 2019). This theory has been extensively studied and discussed as it shows the behavior and perspectives of a specific population group (Runruil-Diaz and Manner-Baldeon, 2018). This is crucial in knowing how to handle and what to offer each generational segment in different fields (Băltescu, 2019).

For this study, we use Williams and Page (2011) as a frame of reference for those who believe that Generation Z includes people born between 1994 and 2010. Generation Z, also called iGeneration, PostMillennials, and NetGeneration (Csobanka, 2016), is characterized as having integrated technology in their personal and professional daily lives, which improves their work performance. They feel confident using these tools to execute their jobs and are considered as having high technical skills since they know how to use multiple programs and applications. This generation is the most accepting of diversity (Betz, 2019) and they prefer to be their own boss (Runruil-Diaz and Manner-Baldeon, 2018).

Generation Z is currently entering the job market due to Baby Boomers retiring, leading to changes in the current work culture and environment (Goh and Lee, 2018; Randstad, 2016). One of the most significant decisions a person has to make in life is deciding which sector to pursue a career in, as it determines their professional and personal development and the environment in which they will grow (Erdinç and Kahraman, 2012). The sector’s organization and the opportunities offered by companies influence this decision. These opportunities are related to the company’s disposition toward its employees, corporate culture, and company social relationships, among other factors (Pelit and Arslantürk, 2011).

There is a broad range of studies about choosing and working in a professional industry. Regarding the tourism industry, and more precisely, Generation Z’s intentions to work in their hometown in this sector, the TPB (Ajzen, 1991) has been used to study this generation’s attitude toward working in this industry, taking into account the opinions of other residents and the problems they may perceive regarding working in this sector (Goh and Lee, 2018). Very few studies on the tourism industry focus on this specific age cohort (Baum et al., 2016).

Their job searches are not primarily based on salary as a motivation (which is more typical of the Millennial generation). Instead, they want to be recognized in their job, work for the company’s good, and have a good work environment with their coworkers (Goh and Lee, 2018). Likewise, they perceive the most value in jobs that focus on helping others or being of use to society (Vaghela and Agarwal, 2018). These attitudes toward work make this generational cohort ideal for the service sector, specifically the tourism industry (Goh and Lee, 2018).

The use of and dependence on new technologies by this cohort is of fundamental importance since they have been born and raised using technology (Prensky, 2001). This fact can be either a facilitator of procedures in the tourism field or an obstacle, depending on how these technological resources are used (Monaco, 2018).

Generation Z considers that working in the tourism industry is satisfactory and exciting, and allows them to travel (Goh and Lee, 2018), which is a factor that motivates them to work in this sector (Brown et al., 2015; Buzinde et al., 2018). However, their intentions to work in tourism in their hometown are very much determined by the actions of the companies that hope to employ this workforce (Martínez González et al., 2017).

Generation Z residents’ perception of tourism and its influence on their intentions to work in the tourism industry, place attachment, and community involvement

Firstly, we describe the conceptualization of residents’ perceptions of tourism development. In this sense, residents’ perceptions of tourism have been a topic of study in prior research (Andereck et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2013), including articles focused on an in-depth literature review of the concept of tourism perceptions (Gursoy et al., 2002; Almeida García et al., 2015). Tourism development affects the host communities (Sharpley, 2014) and impacts them. This influence can be studied from an economic, social, and environmental perspective. Furthermore, the impact of tourism on residents has been analyzed by academics, differentiating between the positive and negative perceptions of this impact. All tourism activities have costs and benefits for these residents (Gursoy et al., 2002; Gursoy et al., 2019).

The economic benefit positively influences residents’ attitudes toward tourism since it improves the local economy and creates jobs (Gursoy et al., 2002; Choi and Sirakaya, 2006; Liu et al., 2023). The economic costs of tourism are associated with increased prices (Andereck et al., 2005) and real estate taxation (Latkova and Vogt, 2012). From a social standpoint, residents value the fact that tourism positively influences the community and the services available (Andereck et al., 2005). It also reinforces cultural identity and promotes cultural protection and revitalization (Kim, 2002). Conversely, residents consider that tourism development can increase traffic congestion and various services provided to citizens (Latkova and Vogt, 2012; Ko and Stewart, 2002), but also bring about a rise in crime rates (Deery et al., 2012) and increased waste generation (Latkova and Vogt 2012). From an environmental standpoint, some authors claim that tourism helps conserve natural resources (Andereck and Nyaupane, 2011) and improves the city (Andereck et al., 2005). Nevertheless, other authors emphasize the possibility of tourism harming the environment and increasing pollution (Ko and Stewart, 2002).

According to Jimura (2011), some studies claim that when a destination is declared as a WHS, it implies a certain degree of importance that attracts visitors, while significant investments are made to conserve the heritage. This designation can help residents maintain their cultural identity and awaken a stronger sense of place attachment for all the residents at that destination (Jaafar et al., 2015; Gursoy et al., 2002). It also offers economic development opportunities to the area, taking the local community into account and prioritizing conservation programs for the destination (Jaafar et al., 2015; Jimura, 2011). From the perspective of the 2030 agenda and its sustainable development goals (SDGs), tourism can generate value and contribute to the sustainable use of natural and cultural resources. Moreover, it can be an important tool for alleviating poverty in developing countries (Xiao, 2013), accelerating development in a sustainable and environmentally and socially responsible manner (SDGs 1 and 11), fostering partnerships to achieve goals (SDG 17) through strong institutions (SDG 16) (Hosseini et al., 2021). However, such development must be accompanied by improved services and the supervision of private initiatives (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017).

Very few studies focus on the perceptions of young people. This population segment has greater expectations in terms of their perceptions of the benefits of tourism development through WHS recognition (Jaafar et al., 2015), which is closely related to their expectations of job creation and the possibility of getting to know other cultures (Vareiro et al., 2011). A site declared a WHS implies a greater awareness of the importance of its heritage and helps young people recognize its value (UNESCO, 2002 cited by Jaafar et al., 2015). The importance of young people’s positive perceptions of the tourism industry as future decision-makers and workers is not always taken into account (Wu and Pearce, 2013), and very few studies highlight the relationship between residents’ perceptions and the sustainable development of a WHS (Jimura, 2011; Nicholas et al., 2009). This study aims to fill the gap in the literature.

Secondly, describing the impact of residents’ perceptions of tourism development on community involvement is necessary. Some academics state that tourist destination residents’ perceptions of the effects of tourism are a crucial factor in their participation in tourism development (Gursoy et al., 2002; Jaafar et al., 2015). Residents’ perceptions of the positive or negative impact of tourism development on their hometowns influence their involvement in the development (Nicholas et al., 2009). Various studies highlight community involvement as a key to the sustainability of tourism development (Nicholas et al., 2009).

In the case of a WHS, residents play an essential role in implementing activities and maintaining the sites with this designation (Vlase and Lähdesmäki, 2023). Their involvement helps the destination’s economic development through tourism development and heritage conservation, improving their living conditions (Jaafar et al., 2015; Nicholas et al., 2009), favoring conflict resolution among neighbors (Su and Wall, 2014), and promoting their traditions, values, and lifestyle (Sheldon and Abenoja, 2001). Some authors’ results confirm a direct, positive relationship between young people’s positive perceptions of tourism development on community involvement in promoting and supporting a WHS (Jaafar et al., 2015). Other studies have shown that residents with a highly positive perception and a low negative perception of tourism development favor community involvement (Jaafar et al., 2015; Latkova and Vogt, 2012; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017).

There is no consensus among the prior research regarding the influence of negative perceptions on community involvement. Some studies claim that residents’ negative perceptions hurt community involvement (Latkova and Vogt, 2012; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2015); meanwhile, other academics argue that there is no significant impact (Jaafar et al., 2015; Gursoy et al., 2002).

Thirdly, the impact of residents’ perceptions of tourism development on place attachment is analyzed. Referring to it, place attachment is a term that has been extensively studied to understand how tourists behave at tourist destinations. However, few studies develop this concept regarding the area’s residents, and fewer studies discuss destinations designated as a WHS (Hoang et al. 2020). Some authors have demonstrated that negative perceptions of tourism development positively affect place attachment (Harrill, 2004; Jaafar et al., 2015). Also, young WHS residents’ positive perceptions of tourism development do not directly affect place attachment, although they do indirectly through community involvement (Jaafar et al., 2015). Nevertheless, other authors like Bett (2005) contradict this finding, concluding that young people’s positive perceptions affect place attachment and community involvement.

Fourthly, the impact of residents’ perceptions of tourism on their intentions to work in tourism is reviewed. Accordingly, tourism companies must be aware of young people’s perceptions of being part of the industry workforce, even more importantly, due to high employee turnover in this sector (Baum et al., 2016). This knowledge is essential for attracting and retaining talent (Richardson, 2009).

According to Davidson et al., (2011), generational change is one of the most important research topics for human resources management in tourism. Nonetheless, very few studies have addressed the topic of human resources in this industry, and those that have considered it focus more on the general context of tourism than on problems with the workforce in this field (Baum et al., 2016).

This younger generation is different from prior generations, as younger people are generally more interested in this field, especially since it offers them the opportunity to travel and have new experiences (Goh and Lee, 2018), which makes them more motivated to work in this sector (Buzinde et al., 2018). The low salaries are not a determining factor for them as they are motivated by the possibility of having a professional career and job satisfaction (Goh and Lee, 2018).

Hereafter, when referring to the Gen Z construct, we specifically refer to the young residents of Antequera that belong to this generation. Considering all of the above, we postulate the following hypotheses:

H1. Gen Z’s positive perceptions toward tourism development have a direct, positive influence on their intentions to work in tourism in their WHS hometown.

H2. Gen Z’s negative perceptions toward tourism development have a direct, positive influence on their intentions to work in tourism in their WHS hometown.

H3. Gen Z’s positive perceptions toward tourism development have a direct, positive influence on community involvement.

H4. Gen Z’s negative perceptions toward tourism development have a direct, positive influence on community involvement.

H5. Gen Z’s positive perceptions toward tourism development have a direct, positive influence on place attachment.

H6. Gen Z’s negative perceptions toward tourism development have a direct, positive influence on place attachment.

H7. Gen Z’s positive perceptions toward tourism development have an indirect, positive influence on their intentions to work in tourism in their WHS hometown through community involvement.

H8. Gen Z’s negative perceptions toward tourism development have an indirect, positive influence on their intentions to work in tourism in their WHS hometown through community involvement.

H9. Gen Z’s positive perceptions toward tourism development have an indirect, positive influence on their intentions to work in tourism in their WHS hometown through place attachment.

H10. Gen Z’s negative perceptions toward tourism development have an indirect, positive influence on their intentions to work in tourism in their WHS hometown through place attachment.

Community involvement in promotion and support of World Heritage Sites, and its influence on place attachment and intentions to work in the tourism industry

Regarding community involvement, it has also been conceptualized in the scientific literature as community participation. Community involvement is defined as a collaborative work process of a group of people related through interest, proximity, or situation to address a reality that affects the well-being of those people; it goes beyond community engagement (McCloskey et al., 2011). Although community involvement has been the subject of academic study since the mid-twentieth century when research was conducted in sociology, such as Sower and Freeman (1958), its implication in economic development in general, and in tourism activity in particular, is more recent.

From a tourism standpoint, the concept of residents’ involvement in their community has been analyzed primarily from the perspective of economic development (Ndivo and Cantoni, 2016), tourism sustainability (Li and Hunter, 2015), and a combination of both (Nyaupane et al., 2006). In the specific field of WHSs, various studies have concluded that the promotion and support of community involvement plays a decisive role in successful heritage management and tourism planning (Jaafar et al., 2015; Yung and Chan, 2011). Furthermore, this success results in meeting the needs and interests of residents (Tavares et al., 2015).

Community involvement in cultural heritage projects improves residents’ place attachment, which in turn helps people develop trusting relationships and stronger connections, enabling them to appreciate and better understand the value of what they have nearby (Jaafar et al., 2015; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2013; Yung and Chan, 2011). Consequently, a community’s involvement in tourism development increases their place attachment to that tourist destination (Gross and Brown, 2008). Several studies have highlighted that community involvement among young residents is crucial for the future development of these programs, creating a stronger connection with their community thanks to their playing an important role in promoting and supporting it (Jaafar et al., 2015; Wu and Pearce, 2013).

Nevertheless, the scientific literature does not explore in depth how young people’s community involvement in these tourism projects influences their intentions to work in this industry. This study aims to compensate for this gap in the literature. We have therefore developed the following hypotheses based on the literature review:

H11. Community involvement has a direct, positive influence on intentions to work in tourism in the WHS hometown.

H12. Community involvement has a direct, positive influence on place attachment.

H13. Community involvement has an indirect, positive influence on intentions to work in tourism in the WHS hometown through place attachment.

Place attachment and its influence on work intentions

Multiple terms and definitions have conceptualized a person’s attachment to a particular place (Halpenny, 2010). In the specific literature on tourism, the word ‘place attachment’ is the most frequently used, in addition to others such as community attachment (Hoang et al., 2020) or sense of belonging as a result of this attachment (Di Masso et al., 2017).

Place attachment is considered a multidimensional construct (Ramkissoon et al., 2013) whose components refer to dependence, identity, and fondness for one’s place of residence. Place attachment can be defined as an individual’s cognitive and emotional connection to a specific place or environment (Low, 1992), or, in a broader sense, an effective long-term connection with a specific geographic area that inspires a sense of belonging through one’s identification with the location (Hay, 1998).

Specific authors have confirmed that when a location is declared a WHS, there is an increase in the sense of belonging or attachment to the place and the community, to the point that residents may want to start a business there and live their entire lives at that location (Han et al., 2020). This place attachment makes individuals feel that their needs are the same as those of the general community and that they share the same history and heritage (Chi et al., 2017). These studies have also confirmed that the most recent arrivals and young people develop place attachment more quickly if tourism is highly developed. Therefore, place attachment, perception of tourism, and community involvement are closely related (Chi et al., 2017). However, we have not found articles that relate the dimension of place attachment (or similar to a sense of belonging or community attachment) to intentions to work in tourism in the WHS hometown. Therefore, considering everything mentioned in the literature review, we believe that this study would not be complete without confirming the existence of a significant relationship between the two constructs.

Therefore, in an attempt to fill this gap in the scientific literature, we propose the following hypothesis:

H14. Place attachment has a direct, positive influence on intentions to work in tourism in the WHS hometown.

Methods

Data collection, participants, and sample

The inclusion criteria for this study were that participants had to be residents of the municipality of Antequera and between the ages of 16 and 26 (Generation Z). The raw data was culled from surveys from February to May 2020. Three professionals were involved in the pre-test: one specialized in youth employment, one in recruitment in the tourism sector, and one academic researching youth employment in the tourism sector. We included their suggestions and required changes made to the final questionnaire. The questionnaire was translated into Spanish by a professional translator. It is a convenience sample, and the responses were collected using Google Forms. The survey was anonymous and complied with ethical standards.

G*Power 3 free software (Faul et al., 2009) was used to determine the appropriate sample size. With a configuration of a small to a medium effect size of 0.05, a significance of 5%, a statistical power of 90%, and in terms of the number of predictors the endogenous variable receives (with a maximum of four predictors of the construct of Gen Z’s intentions to work in their WHS hometown), the resulting appropriate sample size was 313 participants. In our case, out of 366 collected responses, after filtering for outliers and inconsistencies, 315 valid responses formed an appropriate sample.

Indicators and constructs

The questionnaire includes 25 indicators (Table 1) and five constructs: two independent predictor constructs positive perception of tourism development (POS), negative perception of tourism development (NEG), and three endogenous constructs Generation Z’s community involvement in tourism (COMM), place attachment (PLACE), and their intentions to work in their WHS hometown (WORK). We used the same measurement scales validated by Jaafar et al., (2015) except for intentions to work adapted from Goh and Lee (2018). However, factor analysis was calculated to validate each construct using SPSS software for the multiple items associated with each construct. Negative perceptions were not validated for this construct, and two of the five items were eliminated.

Finally, the descriptive measurements of the observable indicators are displayed in Table 2. The skewness coefficients exceed ±1, indicating that the data is not distributed according to a normal distribution.

Methodology and data analysis

This study uses partial least squares – structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). SmartPLS software (Ringle et al., 2015) executed analyses. Moreover, considering that these are behavioral constructs, we opted to use consistent PLS (Dijkstra and Henseler, 2015) and to obtain a large sample size for the measurement models. Nevertheless, anticipating the data from the results, no possible solution was obtained through bootstrapping, indicating that the common factor hypotheses are not fulfilled. According to particular academics (Rigdon et al., 2017; Sarstedt et al., 2016), the construct is a composite of various indicators more than a common factor, which justifies the use of PLS-SEM. Academic manuals using this methodology (Hair-Jr et al., 2017; Hair et al., 2019) and recent manuscripts recommend a series of requirements for evaluating a path model, e.g., Benitez et al. (2020).

Moreover, the indirect effects and type of mediation analysis are also interesting. The mediator analysis is described by various academics (Cepeda et al., 2017; Nitzl et al., 2016) within the context of PLS-SEM. Firstly, the significance of the indirect and direct effects is analyzed to determine whether there is mediation and the type of mediation − either complementary or competitive, or full or partial (Zhao et al., 2010). In addition, the magnitude of the variance accounted for (VAF) to measure how much the indirect effect represents the total effect in terms of proportion (or percentage) is also classified: under 20% there is no mediation; VAF between 20% and 80% is partial mediation, and over 80% is total mediation (Hair-Jr et al., 2017).

Research results and discussion

Profile of participants

Concerning the participants’ descriptive profiles, women account for 67.6% of the respondents, while 32.1% are men, and only one listed their gender as other. The average age is 21.7 years, and the standard deviation is 2.645 years. Forty-six participants (15%) are 16–18 years old, which, according to Spanish law, is the age when they are eligible to enter the job market (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2020) and focus their studies on the economic sector they like the best; 101 respondents (32.1%) are 19–21 years old, and 168 (53.3%) are between the ages of 22 and 26, young people that are about to start working or are already working after studying university degree programs or completing vocational training. It is essential to clarify this information to relate this data to intentions to work in the tourism industry in the WHS hometown. The majority of participants (56.8%) have a university degree or higher level of education; meanwhile, 35.6% have high school examination qualifications or similar education (vocational training) in preparation for a university degree or vocational training, and 7.6% have only completed primary education (Table 3).

Results of the variance-based structural equation model

Regarding the measurement model, outer loadings achieve the threshold of 0.7. To evaluate the reliability of the construct, we calculated Cronbach’s alpha, Dijkstra-Henseler’s rho (RhoA), composite reliability (CR), and the convergent validity through the average variance extracted (AVE), achieving the thresholds required (Table 4).

The Fornell-Larcker criterion (1981), the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations, HTMT (Henseler et al., 2015) (Table 5), and the examination of cross-loadings (Table 6) are the approaches for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling and meets the required thresholds. Thus, we can conclude that the measurement model meets the requirements established by the criteria mentioned above and is sufficient.

Before evaluating the structural model, it is necessary to check whether severe multicollinearity exists among predictor constructs. Also, the model’s predictive power and, finally, the significance and importance of the standardized beta coefficients (standardized inner weights, usually beta coefficients) and the effect sizes (f2), must be measured (Table 7).

Referring to the collinearity analysis among the predictors, the variance inflation factor (VIF) value threshold under 3.3 (Kock, 2015) has been established, meaning that the multicollinearity between constructs is not severe. The obtained VIF values do not indicate severe multicollinearity between the predictors, in this case, composites. The effects size f2 are included, revealing that the higher value concerns the community involvement in intentions to work in tourism in the WHS hometown.

The model’s explanatory and predictive power can be evaluated using two criteria: the coefficient of determination R2 and the Q2 coefficient Stone-Geisser, respectively. The minimum recommended value of R2 ≥ 0.1 (Falk and Miller, 1992) was met. However, these coefficients are weak for community involvement (R2 = 0.196) and moderate for place attachment (R2 = 0.293) and Gen Z’s intentions to work in tourism in their WHS hometown (R2 = 0.296) according to the thresholds (Hair et al. 2019). On the other hand, concerning the Stone-Geisser coefficient, after applying an omission error of 6, the crossed-validated redundancy value obtained reveals that it is not a predictive model (Hair-Jr et al. 2017).

Figure 1 depicts a graphic representation of the path diagram for the estimated model. Meanwhile, Fig. 2 depicts the five two-path mediated and two three-path mediated effects.

All the constructs have a direct, positive influence on intentions to work in the tourism industry in the WHS hometown. The greatest strength of the direct effects when explaining intentions to work comes from the largest coefficient – in this case, community involvement (β = 0.366, p < 0.05) – while positive perceptions (β = 0.135, p < 0.05) and place attachment (β = 0.137, p < 0.05) are equally relevant, with a similar magnitude. In the case of negative perceptions, the direct effect on intentions to work in tourism in the WHS hometown is not significant (β = 0.056, ns). Table 8 shows the analysis of the significance of the different effects and final decision.

Next, we will analyze the significance and relevance of the direct and indirect effects. Concerning direct effect, all hypotheses are supported except for H4 (negative perceptions have no impact on community involvement). And pertaining to indirect effects, H7, H9, and H13 are significant, and mediators are all partially collaborative. However, the indirect effect of negative perceptions on intentions to work in tourism in the WHS hometown (H8) and on place attachment (H10) are not significant; then, there is no mediation in these cases. Additionally, community involvement and place attachment are partial collaborative – complementary – mediators between positive perceptions and intentions to work in tourism. Community involvement mediates between positive perceptions and place attachment. Finally, place attachment is a partial collaborative mediator between community involvement and intentions to work in tourism. Whether the direct, total indirect, or total effects are significant or not, the decision about hypotheses and the type of mediation are displayed in Table 3. Lastly, in relation to total effects, they highlight the relevance of community involvement and positive perceptions followed by place attachment on intentions to work in tourism in the WHS hometown, being the smallest positive effect of negative perception (see Fig. 3).

Conclusions

Theoretical implications

This study contributes to filling the gap of in-depth research that analyzes the workforce in the tourism industry (Baum et al. 2016). It also responds to the need for future lines of research as proposed by various authors. Firstly, it aims to define the characteristics of the young people that will replace the older workers retiring from the tourism industry (Solnet et al., 2016). Secondly, it analyzes Generation Z’s overall intentions to work in the tourism industry in their hometown without the bias of conducting specifically tourism-related studies (Goh and Lee, 2018). Thirdly, it highlights the need to better study the perceptions of young residents in the development process of a destination, particularly those designated as a WHS (Jaafar et al., 2015). This study responds to this and other questions based on an innovative model that explains the joint influence of the constructs of residents’ perceptions of tourism, community involvement, and place attachment on young residents’ intentions to work in the tourism industry in their WHS hometown.

On the other hand, our research enriches the scope of application of the TPB, confirming that attitudinal factors such as a positive perception of tourism development and place attachment influence the decisional variable (intentions to work in the WHS hometown). The community involvement variable is also confirmed as a factor of subjective norms. However, negative perceptions of tourism have not been determined to be a factor of perceived behavioral control.

The results of this study show how young residents’ positive perceptions of tourism development have a direct, positive influence on community involvement, which confirms the findings of authors (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017; Latkova and Vogt, 2012; Ko and Stewart, 2002). In contrast, the direct effect of Generation Z’s negative perceptions of tourism development through WHS consideration on community involvement is not significant. These results are in line with the conclusions of Gursoy et al. (2002) and Jaafar et al. (2015). These perceived costs may be mitigated by the importance of the community’s place in improving the local economy. Consequently, residents may underestimate the cost and overestimate the economic gains. However, there is no unanimity in the direct effects of negative perceptions on community involvement. The results are contradictory, as some academics reported negative direct effects (Latkova and Vogt, 2012; Nicholas et al., 2009; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2015); meanwhile, there is no significant influence by other authors according to our result. Therefore, although residents are aware of the costs associated with tourism development in their community, it does not impede them from actively participating in their commitment to the community in promoting and supporting Antequera as a WHS.

This analysis is also intended to shed some light on discrepancies among the scientific community regarding the influence of residents’ perception of tourism on place attachment. It shows how young people’s positive perceptions of tourism development have a direct, positive effect on place attachment, creating a sense of belonging, which is in line with conclusions by Bett (2005) and contradicts the claims of Jaafar et al. (2015). Nevertheless, we agree with these authors about the indirect influence of positive perceptions on place attachment through the mediating role of community involvement.

In terms of the influence of young people’s perceptions of tourism on their intentions to work in the sector, this study concludes that their positive perceptions of tourism development have a direct, positive impact on their motivation to work in the tourism industry. In contrast, their negative perceptions do not have any direct effect.

Regarding the positive effect of negative perceptions of tourism development on place attachment, this finding sheds light on the existing discrepancies in the scientific literature, aligning with Jaafar et al.‘s (2015) position. This fact is particularly significant as young residents, who are more attached to Antequera, perceive tourism development more negatively.

With regard to indirect effects, positive perceptions affect positively intentions to work in the WHS hometown through place attachment and community involvement. Also, community involvement impacts positively on intentions to work through place attachment, and positive perceptions influence place attachment through community involvement. However, place attachment and community involvement do not mediate between negative perceptions and intentions to work in tourism. Also, community involvement does not mediate between negative perceptions and place attachment. These indirect results represent an important advance in the scientific literature in this industry, given the lack of specific prior studies that analyze these relationships or consider destinations that have been declared a WHS. The direct, positive influence of beneficial perceptions of tourism is in line with evidence from specific studies like that of Goh and Lee (2018), which shows that Generation Z considers it exciting to work in the tourism industry, bringing them closer to new cultures and experiences (Buzinde et al., 2018).

We believe that one of the reasons why negative perceptions do not directly influence the intentions to work in the tourism industry in the WHS hometown may be because there is no perception of tourism as a threat (as shown in the descriptive analysis of the variables of this construct). Nevertheless, there is an indirect influence through place attachment. The reason may lie that this variable (place attachment) is influenced by negative perceptions and other constructs (positive perceptions and community involvement) that have a greater effect on the mediating variable.

This study also supports the finding that community involvement in promoting and supporting a WHS has a direct, positive influence on place attachment, thereby confirming the results of numerous prior studies (Jaafar et al., 2015; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2013; Gursoy et al., 2002; Nicholas et al., 2009; Yung and Chan, 2011). Thus, aspects such as territorial intelligence become a key tool to promote sustainable and balanced tourism, taking into account the needs and aspirations of local communities and contributing to the socioeconomic development of territories in harmony with their identity and heritage (Llanez Anaya and Sacristán Rodríguez, 2021).

Nevertheless, the lack of prior studies on the influence of community involvement on intentions to work in the tourism industry in the WHS hometown makes these findings especially relevant. Community involvement has the most relevant total effect (direct and indirect) of all the constructs that influence intentions to work in tourism in the WHS hometown. This strong relationship may be because young people actively promote and support the WHS, gain in-depth knowledge of the associated tourism development, and are more in tune with the appeal and excitement of working in this sector.

Practical implications

Generation Z is entering the job market, and this will be a determining factor for the future of the tourism industry (Solnet et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the scientific literature has found that young people from other cohorts (such as Millenials) have certain reservations about working in this sector (Duman et al., 2006). This study presents decisive evidence regarding the variables that serve as a means for this collective to want to work in this industry, enabling tourism companies and public institutions to make decisions to encourage the incorporation of young talent.

From this perspective, public institutions should take action for young residents to form positive perceptions of the area’s tourism development. Improving these residents’ quality of life and their pride in achieving the distinction as a WHS will considerably influence their positive perceptions of tourism development activity, resulting in greater intentions to work in the sector in their WHS hometown.

Public organizations and tourism companies should collaborate with young people from Generation Z to actively promote and support WHSs. On the one hand, these actions will increase their desire to work in the tourism industry and, on the other, increase their sense of belonging as a result of place attachment with Antequera, which will once again increase their desire to work in tourism.

The confirmation that community involvement positively influences intentions to work in the tourism industry in the WHS hometown, and that this is the construct with the biggest effect on this desire, brings to light a series of significant challenges for public-private collaboration in the field of tourism.

Consequently, local public institutions have to find the most appropriate communication links with these young people so that any activity associated with promoting the cultural heritage of Antequera will reach the largest possible number of people enabling them to participate. Furthermore, these institutuions should aim for a high degree of the involvement of these young people beyond merely attending these activities, instead also actively connecting people to develop these activities. The impact will be even greater if companies in the sector get involved in these activities through sponsorships or patronage. Similarly, it is crucial for private companies and tourism institutions to actively collaborate, to avoid tourism development leading to Generation Z forming negative perceptions of this sector. Conservation measures will be essential to protect the heritage site and the environment.

Lastly, recruiters and talent managers in the tourism industry should plan young people’s professional careers by emphasizing the industry’s dynamism and associated emotions and experiences to attract Generation Z. We also believe that tourism companies’ participation in talks and debates with young students about professional opportunities in the tourism industry will be a determining factor. They should also be involved in training programs, including professional internships associated with tourism and specific courses taught in public and private institutions.

This study reveals various limitations and lays the foundations for future research. Firstly, the data refers to cross-section data. So, it would be advisable to conduct a longitudinal analysis over time to see how these perceptions evolve. Secondly, the data was collected right before the onset of COVID-19 and its associated consequences for Antequera as a WHS tourist destination.

Future research lines

Therefore, future studies need to replicate this study in other WHS destinations. Also, it is recommended to expand the field of research, analyzing the antecedents of intentions to work in tourism in the WHS hometown. It would also be interesting to use post-COVID-19 information to track the evolution of young people’s intentions to work in the tourism industry. Finally, we recommend expanding the number of variables that influence their desire to work in tourism, such as personality or the corporate social responsibility of the tourism companies that currently offer work to Generation Z.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the authors.

References

Ahmmadi P, Rahimian M, Movahed RG (2021) Theory of planned behavior to predict consumer behavior in using products irrigated with purified wastewater in Iran consumer. J Clean Prod 296:126359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126359

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2):179–211

Almeida García F, Balbuena Vázquez A, Cortés Macías R (2015) Residents’ attitudes toward the impacts of tourism. Tour Manag 13:33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2014.11.002

Andereck KL, Nyaupane GP (2011) Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents. J Travel Res 50(3):248–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362918

Andereck K, Valentine K, Knopf R, Vogt C (2005) Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann Tour Res 32(4):1056–1076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.03.001

Băltescu CA (2019) Elements of tourism consumer behaviour of generation. Z Bull Transilv Univ Bras, Economic Sciences. Series V, 12(1):63–68

Baum T, Kralj A, Robinson R, Solnet D (2016) Tourism workforce research: a review, taxonomy and agenda. Ann Tour Res 60:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.04.003

Beccaria L, McIlveen P, Fein EC, Kelly T, McGregor R, Rezwanul R (2021) Importance of attachment to place in growing a sustainable Australian Rural Health Workforce: a rapid review. Aust J Rural Health 29(5):620–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12799

Benitez J, Henseler J, Castillo A, Schuberth F (2020) How to perfom and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: Guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory IS research. Inf Manag 57:103168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2019.05.003

Bett A (2005) Role of community in the conservation of Mt. Kenya Biosphere Reserve. Report submitted to UNESCO MAB for the Award of MAB Young Scientists Awards. Penn State College of Information Sciences and Technology, Penn State’s University, Pennsylvania, US [Unpublished manuscript]. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.567.6647andrep=rep1andtype=pdf

Betz C (2019) What Generations X, Y and Z Want from Leadership. J Pediatr Nurs 44:A7–A8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2018.12.013

Brown EA, Thomas NJ, Bosselman RH (2015) Are they leaving or staying: a qualitative analysis of turnover issues for Generation Y hospitality employees with a hospitality education. Int J Hosp Manag 46:130–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.01.011

Buzinde CN, Vogt CA, Andereck KL, Pham LH, Ngo LT, Do HH (2018) Tourism students’ motivational orientations: the case of Vietnam. Asia Pacific J Tour Res 23(1):68–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2017.1399918

Cepeda G, Nitzl C, Roldán J (2017) Mediation Analyses in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Guidelines and Empirical Examples. In H Latan and R Noonan (eds.). Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Basic Concepts, Methodological Issues and Applications (173-195). Springer

Chi CG-Q, Cai R, Li Y (2017) Factors influencing residents’ subjectives well-being at World Heritage Sites. Tour Manag 63:209–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.06.019

Choi HC, Sirakaya E (2006) Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tour Manag 27(6):1274–1289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.05.018

Cronbach L (1951) Coefficient alpha and internal structure of test. Psychometrika 16:297–334

Csobanka Z (2016) The Z Generation. ACTA 6:63–76

Davidson MC, McPhail R, Barry S (2011) Hospitality HRM: past, present and the future. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 23(4):498–516. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111111130001

Deery M, Jago L, Fredline L (2012) Rethinking social impacts of tourism research: a new research agenda. Tour Manag 33(1):64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.01.026

Di Masso A, Dixon J, Hernandez B (2017) Place attachment, sense of belonging and the micro-politics of place satisfaction. In G Fleury-Bahi, E Pol and O Navarro (eds.), Handbook of Environmental Psychology and Quality of Life Research. International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life (85-104). Springer

Dijkstra T, Henseler J (2015) Consistent and asymptotically normal PLS estimators for linear structural equations. Comput Stat Data Anal 81:10–23

Dijkstra T, Henseler J (2015) Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q 39(2):297–316. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26628355

Duman T, Tepeci M, Unur K (2006) The comparative analysis of university and high school level tourism students’ perceptions on work conditions and desire to work in the tourism industry in mersin. Anatolia 17(1):51–69

Erdinç S, Kahraman S (2012 April 12-15) Turizm mesleğini seçme nedenlerinin incelenmesi [Conference paper] VI. Lisansüstü Turizm Öğrencileri Araştırma Kongresi, Kemer (pp. 229-237). Antalya, Turkey

Falk R, Miller N (1992) A primer for soft modeling. University of Akron Press

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A (2009) Statistical power analyses using g*power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analysis. Behav Res Methods 41(4):1149–1160. https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpower.html

Fornell C, Larcker D (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

Goh E, Lee C (2018) A workforce to be reckoned with: the emerging pivotal Generation Z hospitality workforce. Int J Hosp Manag 73:20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.01.016

Goh E, Okumus F (2020) Avoiding the hospitality workforce bubble: strategies to attract and retain generation Z talent in the hospitality workforce. Tour Manag Perspect 33:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100603

Gross MJ, Brown G (2008) An empirical structural model of tourists and places: progressing involvement and place attachment into tourism. Tour Manag 29:1141–1151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.02.009

Gursoy D, Jurowski C, Uysal M (2002) Resident attitudes: a structural modeling approach. Ann Tour Res 29(1):79–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00028-7

Gursoy D, Ouyang Z, Nunkoo R, Wei W (2019) Residents’ impact perceptions of and attitudes toward tourism development: a meta-analysis. J Hospitality Mark Manag 28(3):306–333

Hair JF, Hult GT, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Castillo-Apraiz J, Cepeda Carrion G, Roldán JL (2019) Manual de Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). OmniaScience (Omnia Publisher SL)

Hair-Jr JF, Hult GT, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2017) A Primer On Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd edn). SAGE Publications Inc

Halpenny E (2010) Pro-environmental behaviours and park visitors: the effect of place attachment. J Environ Psychol 30(4):409–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.04.006

Han W, Cai J, Wei Y, Zhang Y, Han Y (2020) Impacts of the world heritage list inscrption: a case study of Kaiping Diaolou and villages in China. I J Strateg Prop Manag 24:51–69. https://doi.org/10.3846/ijspm.2019.10854

Harrill R (2004) Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: a literature review with implications for tourism planning. J Plan Lit 18(3):251–266

Hay R (1998) A rooted sense of place in cross‐cultural perspective. Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien, 42(3):245–266

Henseler J, Ringle C, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43(1):115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hoang T, Brown G, Kim A (2020) Measuring resident place attachment in a World Cultural Heritage tourism context: the case of Hoi An (Vietnam). Curr Issues Tour 23(16):2059–2075. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1751091

Hotels, Restaurants, Bars and Cafes in Europe [HOTREC] (2019) Facts and figures: the hospitality industry’s contributions to European economy society. [data set] https://www.hotrec.eu/facts-figures/

Hosseini K, Stefaniec A, Hosseini SP (2021) World Heritage Sites in developing countries: assessing impacts and handling complexities toward sustainable tourism. J Dest Mark Manage 20:100616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100616

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2020) Tasas de empleo según grupos de edad. Brecha de género. [Data set] https://www.ine.es/ss/Satellite?L=es_ESandc=INESeccion_Candcid=1259925463013andp=1254735110672andpagename=ProductosYServicios%2FPYSLayoutandparam3=1259924822888

Innerhofer J, Luigi Nasta L, Cabot J, Zehrer A (2022). Antecedents of labor shortage in the rural hospitality industry: a comparative study of employees and employers. J Hosp Tour Insights. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-04-2022-0125

Jaafar M, Noor SM, Rasoolimanesh SM (2015) Perception of young local residents toward sustainable conservation programmes: a case of study of the Lenggong World Cultural Heritage Site. Tour Manag 48:154–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.018

Jimura T (2011) The impact of world heritage site designation on local communities—a case study of Ogimachi, Shirakawa-mura, Japan. Tour Manag 32(2):288–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.02.005

Kim K (2002) The effects of tourism impacts upon quality of life of residents in the community. Blacksburg, Virginia

Kim K, Uysal M, Sirgy MJ (2013) How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour Manag 36:527–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.09.005

Kichuk A, Brown L, Ladkin A (2019) Talent pool exclusion: the hotel employee perspective. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 31(10):3970–3991. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2018-0814

Ko D, Stewart W (2002) A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tour Manag 23(5):521–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00006-7

Kock N (2015) Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int J e-Collab 11(4):1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

Latkova P, Vogt C (2012) Residents’ attitudes toward existing and future tourism development in rural communities. J Travel Res 51(1):50–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510394193

Larkins S, Michielsen K, Iputo J, Elsanousi S, Mammen M, Graves L, Neusy AJ (2015) Impact of selection strategies on representation of underserved populations and intention to practise: international findings. Med Educ 49(1):60–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12518

Li Y, Hunter C (2015) Community involvement for sustainable heritage tourism: a conceptual model. J Cult Heritage Manag Sustain Dev 5(3):248–262. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-08-2014-0027

Liu YL, Chiang JT, Ko PF (2023) The benefits of tourism for rural community development. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:137. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01610-4

Llanez Anaya HF, Sacristán Rodríguez CP (2021) Desarrollo territorial y economía solidaria: análisis desde el concepto de desarrollo, el medio ambiente y la incorporación de las comunidades en una estrategia de desarrollo territorial. Tendencias 22(1):254–278

Low S (1992) Symbolic ties that bind: place attachment in the plaza. In Altman I, Low SM (eds), Place Attachment. Human Behavior and Environment (Advances in Theory and Research) (vol. 12, 165–185). Springer, Boston

Martínez González JA, Parra-Lopez E, Buhalis D (2017) The loyalty of young residents in an island destination: an integrated model. J Dest Mark Manag 6(4):444–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.07.003

McCloskey D, McDonald M, Cook J, Heurtin-Roberts S, Upgrove S, Sampson D, Gutter S (2011) Chapter 1. Community engagement: definitions and organizing concepts from the literature. CTSA Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement, Principles of Community Engagement [Internet] Publication No. 11–7782 (pp. 3–41). NIH. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pce_intro.html

Monaco S (2018) Tourism and the new generations: emerging trends and social implications in Italy. J Tour Futures 4:7–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-12-2017-0053

Ndivo R, Cantoni L (2016) Rethinking local community involvement in tourism development. Ann Tour Res 57:275–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.014

Nicholas L, Thapa B, Ko Y (2009) Residents’ perspectives of a world heritage site. The pitons management area, St. Lucia. Ann Tour Res 36(3):390–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.03.005

Nitzl C, Roldan J, Cepeda G (2016) Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modeling: Helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Ind Manag Data Syst 116(9):1849–1864. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0302

Nyaupane G, Morais D, Dowler L (2006) The role of community involvement and number/type of visitors on tourism impacts: a controlled comparison of Annapurna, Nepal and Northwest Yunnan, China. Tour Manag 27(6):1373–1385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.12.013

Pelit E, Arslantürk Y (2011) The importance of practices regarding business ethics of tourism enterprises on workplace choice: a study on tourism student. J Fac Econ Adm Sci 16(1):163–184

Prensky M (2001) Digital natives, digital immigrants. On Horizon 9(5):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424843

Ramkissoon H, Smith L, Weiler B (2013) Relationships between place attachment, place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviour in an Australian national park. J Sustain Tour 21(3):434–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.708042

Randstad (2016) Gen Z and Millennials collide at work. [Online report] https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/409577/Pre-Team%20Drive%20PDFs/Randstad_GenZ_Millennials_Collide_Report.pdf

Rasoolimanesh SM, Ringle CM, Jaafar M, Ramayah T (2017) Urban vs. rural destinations: resident’s perceptions, community participation and support for tourism development. Tour Manag 60:147–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.11.019

Rasoolimanesh S, Badarulzaman N, Mastura J (2013) A review of city development strategies success factors. Theo Empir Res Urban Manag 8(3):62–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24873357

Rasoolimanesh S, Jaafar M, Kock N, Ramayah T (2015) A revised framework of social exchange theory to investigate the factors influencing residents’ perceptions. Tour Manag Perspect 16:335–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2015.10.001

Rasoolimanesh S, Roldán J, Jaafar M, Ramayah T (2017) Factors Influencing Residents’ Perceptions toward Tourism Development: Differences across Rural and Urban World Heritage Sites. J Travel Res 56(6):760–775. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516662354

Richardson S (2009) Undergraduates’ perceptions of tourism and hospitality as a career choice. Int J Hosp Manag 28(3):382–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2008.10.006

Rigdon E, Sarstedt M, Ringle C (2017) On Comparing Results from CB-SEM and PLS-SEM. Five Perspectives and Five Recommendations. Marketing ZFP 39(3):4–16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26426850

Ringle C, Wende S, Becker JM (2015) Software “SmartPLS 3” (version Professional 3.3.3). Boenningstedt, Federal Republic of Germany. http://www.smartpls.com

Runruil-Diaz N, Manner-Baldeon F (2018) Perfil del turista de la generación Z que visita Guayaquil. Kalpana, Revis Investig 16:4–27. ISSN: 1390-5775

Sarstedt M, Hair J, Ringle C, Thiele K, Gudergan S (2016) Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: where the bias lies! J Bus Res 69(10):3998–4010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.06.007

Sharpley R (2014) Host perceptions of tourism: a review of the research. Tour Manag 42:37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.10.007

Sheldon PJ, Abenoja T (2001) Resident attitudes in a mature destination: the case of Waikiki. Tour Manag 22(5):435–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00009-7

Solnet D, Baum T, Robinson R, Lockstone-Binney L (2016) What about the workers? Roles and skills for employees in hotels of the future. J Vacat Mark 22:212–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766715617403

Solnet D, Kralj A, Kandampully J (2012) Generation Y employees: an examination of work attitude differences. J Appl Manag Entrepren 17(3):36–54

Sower C, Freeman W (1958) Community involvement in community development programs. Rural Sociol 23(1):25

Su M, Wall G (2014) Exploring the shared use of world heritage sites: residents and domestic tourists’ use and perceptions of the summer palace in Beijin. Int J Tour Res 17:591–601. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2026

Tan KL, Lew TY, Sim AK (2019) An innovative solution to leverage meaningful work to attract, retain and manage generation Y employees in Singapore’s hotel industry. Worldw Hosp Tour Themes 11(2):204–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-11-2018-0075

Tavares A, Henriques M, Domingos A, Bala A (2015) Community involvement in geoconservation: A conceptual approach based on the geoheritage of South Angola. Sustainability 7(5):4893–4918. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7054893

Vaghela P, Agarwal H (2018, December 21-22) Work Values of GEN Z: Bridging the Gap to the Next Generation [Conference paper]. INC-2018 - National Conference on Innovative Business Management Practices in 21st Century, Faculty of Management Studies, Parul University, Gujarat, India

Vareiro L, Ribeiro JC, Remoaldo PC, Marques, V (2011) Residents’ perception of the benefits of cultural tourism: The case of Guimarães. In A. Steinecke and A. Kagermeier (Eds.), Kultur als Touristischer Standortfaktor – Potenziale – Nutzung – Management, Paderborn Geographical Studies (pp. 187–202). Institute series no. 23. University of Paderborn, Germany

Vlase I, Lähdesmäki T (2023) A bibliometric analysis of cultural heritage research in the humanities: The Web of Science as a tool of knowledge management. Humanit. Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01582-5

Williams K, Page R (2011) Marketing to the Generations. J Behav Studies Bus 3(1):37–53

Werts C, Linn R, Jöreskog K (1974) Intraclass reliability estimates: Testing structural assumptions. Educ Psychol Meas 34(1):25–33

Wu M, Pearce P (2013) Tourists to Lhasa, Tibet: How Local Youth Classify, Understand and Respond to Different Types of Travelers. Asia Pacific J Tour Res 18(6):549–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2012.680975

Xiao H (2013) Dynamics of China tourism and challenges for destination marketing and management. J Destin Mark Manag 2(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2013.02.004

Yung E, Chan E (2011) Problem issues of public participation in built-heritage conservation: Two controversial cases in Hong Kong. Habitat Int 35(3):457–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2010.12.004

Zhao X, Lynch Jr JG, Chen Q (2010) Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J Consum Res 37(2):197–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/651257

Zheng K, Kumar J, Kunasekaran P, Valeri M (2022) Role of smart technology use behaviour in enhancing tourist revisit intention: the theory of planned behaviour perspective, Eur J Innov Manag. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-03-2022-0122

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the University of Malaga, the Faculty of Commerce and Management and the Faculty of Economics and Business, Malaga (Spain). This research is part of the PRY081/22 project titled: ‘Seeking the sustainability of organizations in strategic sectors: tourism and bioeconomy’ to the Andalusian Public Foundation Centro de Estudios Andaluces (ROR: https://ror.org/05v01tw04 and Crossref Funder ID 100019858).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Experimentation of University of Malaga-CEUMA- (No.109-2023-H).

Informed consent

The objectives and methods of the study were fully explained to the participants and electronic informed consent was obtained.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bermúdez-González, G., Sánchez-Teba, E.M., Benítez-Márquez, MD. et al. Generation Z members‘ intentions to work in tourism in their World Heritage Site hometowns. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 841 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02349-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02349-8