Abstract

The aim of the study is to analyze the evolution of gender roles and to generate, from a feminist and intergenerational perspective, a cognitive change in the participants, using film and discussion groups as mediating techniques, since they are considered appropriate to analyze the evolution of gender roles and to raise awareness, from a feminist and intergenerational perspective, about the importance of gender roles in people’s lives. To this end, an intergenerational project, called “ Women in the focus”, was created within the framework of the Master’s program at the Complutense University of Madrid, which allows 75 women, belonging to three different generations, to reflect on the concept of gender and the expectations linked to the term, through three films produced in different decades: The Red Cross girls by Rafael J. Salvia (1958); Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown by Pedro Almodóvar (1988); and My life whith out you by Isabel Coixet (2003). Once the films had been viewed, 21 focus groups were organized, made up of between 3 and 5 women of different ages and, in order to analyze the experience, the 21 coordinators of the discussion groups were interviewed. The data obtained from the interviews and the focus groups were analyzed following a qualitative approach, through the technique of content analysis. The results show that feminist thought has had an impact on the lives of Spanish women, but in different ways depending on their age, thus, there is a discrepancy regarding the roles that women have to fulfill, a difference based on the difficulties they have had to face. With respect to the choice of film and the focus group as research techniques, it is possible to affirm that they have worked, since they have allowed women of three different generations to dialogue and review their approaches to the social construction of gender from a diachronic perspective, generating an empathetic discourse of acceptance and sisterhood, which implies, in spite of the discrepancies, the recognition of the difficulties of each generation of women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Franco’s dictatorship (1939–1974) had a particular impact on Spanish women, who, as seen in the film The Red Cross Girls, lost the rights acquired during the first third of the 20th century and were condemned to the role of wife and mother as the only means of social promotion (Arránz, 2020).

In this sense, during the Francoist period, women lacked the freedom to make decisions, requiring permission from fathers, if they were single, or from husbands to travel, own property, work, have a bank account, etc. (Bover, 2004). During this period, the majority of Spanish women dedicated themselves solely to reproductive tasks related to care (Loscertales and Núñez, 2009).

Since the 1960s, the number of women entering university and subsequently the work world has increased. This incorporation is questioned on a social level since unemployment is mainly attributed to the increased presence of women in the workplace, which sets the stage for the emergence of the slogan “one family, one job”. However, despite social pressure, nothing stops this progress, and the number of women with higher education degrees and liberal professions is progressively increasing (Puigvert and Redondo, 2005).

During this period, women began to demand equal rights (Thornham, 1999), achieving a legal ban against discrimination on the basis of sex with Article 14 of the Spanish Constitution.

However, this incorporation into the labour market does not prohibit women from engaging in reproductive tasks linked to caring for the family. Forced to maintain a double working day, these women are hindered in their professional careers and distanced from managerial positions (INE, 2022). As a consequence, marriage and birth rates fall, new types of families appear, and a strong social demand arises, linked to the feminism of difference (Sendon, 2000). This movement demands that the state provide resources to improve work-life balance and positive measures that recognise gender roles to avoid the so-called glass ceiling (Raya, 2007 and Moreno, 2019).

In the first decade of the 21st century, Spanish society has changed radically. As a consequence of feminism’s fourth wave, a new concept of women has appeared that also aims to attend to their needs, which are always perceived as postponed, with actions in favour of work-life balance and professional careers, thus recognising their own identity (Varela, 2019).

The evolution of the social context for Spanish women shows how the imprint of feminism is evident; democracy made it easier for the waves of the movement to reach the peninsula with force and transform the orography of gender, which in just a few decades was changed by the chisel of women’s thought (Moreno, 2019).

These changes have led to the coexistence of generations with such different gender stereotypes that they are even opposed to each other, generating misunderstandings and making solidarity difficult (Arránz, 2020) since each wave has had to deal with different difficulties. As women entered university, the labour market and professional careers and met the demands of each of these areas of socialisation, these new roles had to be reconciled with the reproductive roles centred on caring for their descendants and predecessors (Bover, 2004).

In this sense, gender transformations have in turn generated changes in the welfare system, which has had to adapt and create professional services for women, who have been requesting greater state involvement to achieve equality (Martínez-Vérez, 2011).

However, in addition to conciliation services and affirmative action measures, it is necessary to generate spaces for reflection and analysis and tools to promote sisterhood between different generations, and artistic social work, applied to groups, is an appropriate method to address this need (López, 2010).

Thus, within the framework of this context of feminist reflection, the idea of “Women in the Spotlight” was born in the Master in Artistic Education in Social and Cultural Institutions of the Complutense University of Madrid (MEDART). From artistic social work with intergenerational groups, this project links feminist reflection with artistic expression to generate a cognitive change in the participants and was implemented in 2022.

After the potential of different artistic techniques was analysed, film was chosen as a reflective and analytical tool based on its ability to capture the dominant stereotypes in the social imaginary and represent them through a plot. This narrative representation in turn transports us to this imaginary world, generating an empathetic response in the audience (Puebla and Carrillo, 2011).

For this reason, after reviewing the filmography on the subject, the following films were chosen: The Red Cross Girls by Rafael J. Salvia (1958); Woman on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown by Pedro Almodóvar (1988); and My Life Without You by Isabel Coixet (2003), according to these criteria:

-

1.

They present the social roles and expectations of women according to the period in which they were performed, i.e., they keep women at the centre of the stage.

-

2.

Each of them presents different challenges faced by women: marriage as a means of social advancement (1950s), reconciling family and work (1980s) and attending to one’s own desires and needs (2000s).

-

3.

The films are separated by at least two decades, evidencing an evolution in gender roles and expectations.

-

4.

In the course of film selection, the date of birth of the participating women was taken into account so that no generation was excluded.

Finally, after selecting the three films that make up the film selection, intergenerational discussion groups are organised.

Objectives of the study

The aim of this study is to analyse the evolution of gender roles and to generate, from a feminist and intergenerational perspective, a cognitive change in the participants, using film and discussion groups as mediating tools.

Following Ruíz (2012) and Kvale (2011), the object of study is operationalised in specific objectives, according to the dimensions or “keys” that define it (see Table 1).

Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework for the project “Women in the Spotlight” is defined by the method of social work with groups, taking into account that the purpose of this method, to raise awareness and provoke a cognitive change in the participants, is part of the objectives of this discipline (López, 2010).

In this sense, the purpose of group dynamics is to promote awareness, attitudinal change, cohesion, empowerment and the liberation of individuals and the communities in which they participate so that they can cope with life’s problems (Segado and García-Castillo, 2022).

In light of the rapid evolution of gender expectations in Spanish society, a profound intergenerational clash exists among women (Loscertales and Núñez, 2009), which is evident in the existence of different sexist stereotypes (Arránz, 2020). Thus, this methodological framework is appropriate for promoting reflections that favour cognitive and attitudinal change, as interdisciplinary projects focused on raising awareness are necessary parts of social change.

Specifically, it is possible to affirm that the proposed work plan is framed within Paulo Freire’s conscientisation model, which organises the intervention in several phases: 1- the analysis of reality, becoming aware of the factors that oppress people, groups and communities; 2- attention to social processes and community objectives through social practice; 3- investigation of the results; and 4- cocreation, through discursive practice and the production of meaning, of a reality full of sense and meaning (Segado and García-Castillo, 2022). Cinema, within the framework of this model, is used as a mediating tool to analyse the female gender and its evolution across the cinematographic representation in film productions, letting viewers become aware of the stereotypes that oppress women and generating dialogue and cognitive change.

Methodology

Focus of the study

In keeping with the objective set out in the previous section, the research approach will be qualitative since the project aims to analyse how gender expectations impact women’s lives and understand the perspective of the people involved (Hammersley and Atkinson, 1994).

The aim is to establish a difference between gender identity, understood as objective, and the collective imaginary that sustains it, which, by definition, is a social construction (Lefevre and Lefevre, 2014).

In this way, through discursive practice (Spink and Medrado, 2000) linked to an emerging interdisciplinary field such as art (Denzin and Lincoln, 1998), the participants in “Women in the Spotlight” generate a new discourse on gender.

Consequently, we opted for a mixed research design (Alonso, 2013) that employs the combined use of several techniques, film forums and discussion groups, to approach the intersubjectivity of the participants (Reidl, 2012). The approach is exploratory in that it aims to analyse the impact of an artistic technique to promote feminist debate, establishing and operationalising this objective (Ruíz, 2012). The approach is also holistic, given that the project is developed through the three cores that make up the human condition: the cognitive, the emotional and the corporal dimensions (Moreno, 2022).

Participants

A total of 75 women from 3 generations participated in “Women in the Spotlight”. The largest age group had 32 individuals under 35 years old, while 22 individuals were between 35 and 59 years old, and 21 were over 60 years old.

In addition to the three researchers who proposed the study, two of whom are specialists in fine arts and another in sociology and social work, three institutions participated collaboratively: MEDART, which acted as proposer and facilitator, the Anxel Casal Integrated Vocational Training Centre (CIFP) and the Faculty of Social Work at the National University of Distance Education, which both participated and collaborated in the research through the specialist in sociology and social work.

The recruitment process for participants was carried out through MEDART’s partner organisations, taking into account the following criteria:

-

1.

Women belonging to a collaborating entity.

-

2.

Women born between 1950 and 2002, so that the youngest participants would have reached the age of majority.

-

3.

Women who showed interest in participating in the project.

To achieve methodological coherence, a protocol of good practices (Declaration of Helsinki, 2008) was adopted by the participating institutions in two phases:

-

1.

MEDART informed the participants about the nature, purpose and methodological procedure, requesting their collaboration.

-

2.

Participants were asked for their informed consent to the protocols, which specified the confidential treatment of the data, limits on data disclosure to the academic and scientific spheres and the personal responsibility and physical place for data safekeeping.

The process of data collection

In accordance with the procedure outlined in the previous sections, two data collection techniques were used: 1- focus groups to address the evolution of female gender roles and expectations and 2- interviews to analyse the suitability of the techniques used and how they fit in with the social work method.

To meet this objective, 21 discussion groups were organised, comprising between three and five women from different generations (total: 75 women). These women first watched the films, then reflected on them individually and, finally debated as a group about female gender roles and their evolution.

Subsequently, the 21 discussion coordinators in the groups were interviewed to determine how they functioned as a tool for feminist reflection and discussion.

Data collection techniques

The techniques used to achieve the socioeducational objectives are 1- film and 2- discussion groups.

-

1.

Film is a mediating technique that facilitates reflection, in this case, on the roles and expectations linked to the female gender through a script or narrative plot recreated by the characters. This plot represents the collective imaginary, that is, the stereotypes of a society or culture, which, when preserved on tape and reproduced, have the power to transport us to that imaginary (Puebla and Carrillo, 2011). Thus, it is through the diachronic interaction with the film that we can observe the evolution of gender archetypes and demystify “the eternal feminine” (Guil, 1998).

In film, what happens to the characters is objectified, i.e., it is naturalised, so that viewers tune in and feel represented in the plot. What the actors do is then “normal” or “expected” in the era when the film is produced (Cruzado, 2011).

Therefore, by analysing the presentation of women in cinema through films produced in different periods, it is possible to appreciate the evolution of gender expectations so that what is understood as “normal”, “natural” or “objective” becomes subjective, specific to a particular time and culture and, therefore, a “social construction” (Rincón, 2014).

Thus, after verifying the narrative and representational power of film, the researchers specified the film set, selected the participants through MEDART, as indicated in the previous subsection, and organised the discussion groups, placing the reflection on the evolution of gender expectations at the centre of them.

-

2.

The focus group is a conversational technique that works with “speech” to produce a result, thus requiring a coordinator or moderator. The focus group “makes possible the reconstruction of social meaning through group interaction” (Llopis, 2004, p.35). Thus, the rationale of the focus group is based on the fact that “if the meaning is group, it seems obvious that the form of the focus group will have to be better adapted to it than the individual interview” (Canales and Peinado, 1995, p.290).

-

3.

The interview is also a conversational technique, “a face-to-face interaction between the interviewer (the researchers), and the interviewees (the focus group coordinators), in which the latter behave as representatives of an individual perspective, that of the focus group “ (Llopis, 2004, p.35). Its purpose, within the framework of this project, is to obtain information regarding the suitability of the film forum in relation to the project’s objectives.

For Alonso (1999), the interview provides information on how people individually approach and/or distance themselves from gender stereotypes. This information complements that offered by the discussion groups since the stereotypes themselves are debated towards an eventual group perspective on them, but the groups do not offer individual data.

Data analysis

Once the requested information was obtained, content analysis was conducted (Vallés, 1999), coding and categorising the information by means of previously established units of analysis (dimensions) and units of measurement (variables).

Regarding the success or suitability of the techniques, the results were discussed by the members of the GIMUPAY research group of the Complutense University of Madrid.

After analysing the information derived from the focus groups and interviews, the results are written up, including images of the artistic practices; these images should not be considered results but only an illustration of what happened.

Results

The results of the study are shown below, grouped according to the dimensions established in the methodology:

Gender and its social construction

The viewing of the three selected films generated an intense debate about gender in the intergenerational discussion groups. While the older women admitted that they have never asked themselves about the meaning of the word woman and the impact of gender in their lives, as seen in the following quote, “It is a question that has never bothered me, I just assumed it (I- 62 years old)Footnote 1“, the younger women believe that reflecting on gender is an obligation, not only for themselves but for society as a whole. A younger woman said, “We must continually rethink gender, fight the idea that it is something obvious” (I- 19 years old). In this sense, the younger women demand an awareness of the true meaning of the term and its social construction under the patriarchy since “we must not forget that the identity of women, what they have to be, has been defined by men” (I-27 years old).

For their part, the middle-aged group of women participants, who came up against the glass ceiling, explain how the gender debate in their generation has focused on “making visible the gender gap that prevented us from growing professionally and at the same time having a family” (I-57 years old). The truth is that “the word that defines gender in our generation was [a source of] discrimination in almost all fields: access to public positions, to the management of companies, to the heads of administration and so on and so forth” (I-56 years old).

For this reason, “we fought hard to get the state to provide work-life balance services to help us achieve a balance between work and family” (I-55 years old). In this sense, “the truth is that if it wasn’t for my mother, I wouldn’t have been able to work, she raised my children and it was hard for both of us” (I- 54 years old).

Thus, this intermediate age group believes that in their youth, “the role of women as mothers and carers was not valued. It was done, or delegated when possible—to the extent that it was possible—but at great cost, not only economically, but above all emotionally” (I-51 years old).

The imprint of feminism strongly penetrates the discourse of younger women, who state that its influence has been crucial in their lives. One woman commented, “The concept of woman I have today comes from the women’s liberation movement” (I-23 years old), and these younger women even quote and explain to the older women the key ideas of the different waves of the movement, with special emphasis on the radical feminist Judith Butler, whom they consider the core of the fourth wave. The older women admit that they do not participate in the debate, are surprised by the evolution of the women’s liberation movement and do not understand the idea of abolishing gender terms. At the same time, these older women do admit to having fought for equality, sending their daughters to university studies because “an educated woman has more opportunities; she can go wherever she wants. It is good not to depend on her husband” (I-84 years old).

For its part, the feminism that has marked the generation of middle-aged women has focused on “fighting to compensate for the gender difference through measures to support women” (I- 56 years old); “Have we achieved it? I don’t think so, but at least now women are more visible and more recognized” (I- 48 years old), so “I think our daughters will find it easier to take care of their careers and their families, i.e., they won’t be constantly on the verge of a nervous breakdown” (I- 52 years old).

There is a great discrepancy between the adjectives that define women and the roles that they have to play in society. Thus, for older women, the most important role for women is motherhood. The possibility of gestation is what differentiates and defines them with respect to men. As one woman stated, “We receive the gift of giving life, of creating a human being and it is a privilege” (I-62 years). Another added, “We are more peaceful and sentimental. Biologically, we are more prepared to care for and show affection towards others” (I-80 years). Therefore, while for this generational cohort, motherhood is a determining factor, for younger women it is a choice or a possibility “that does not complete you or define you as a woman” (I-23 years old). Younger women refuse to define or categorise themselves in relation to the other sex, as “men and women are whatever they want to be. They have interests, they work, they make an effort, they go through life and that is what defines them” (I-26 years old).

For their part, middle-aged women hold that, based on their experience, “being a woman is difficult. I remember that when my daughter was little, I was always anxious, running from one place to another” (I-45 years old). Another commented that “I often had to tell lies at school and at work. I was almost always late to one place or another and everything was fine” (I-44 years old) because “if the child got sick, my life was chaos” (I-52 years old). In this sense, a woman explains, “I would have liked to have been head of services, but I had to take courses and study on weekends and in the evenings, and it was impossible” (I-54 years old). In addition, “when my children were starting to become adolescents and were more autonomous, my mother fell ill and I looked after her. I think I spent my life looking after her and working as best I could” (I-57 years old).

However, despite these differences, contraceptive methods, especially for women, are viewed positively by all the generations of participating women. For older women, unwanted pregnancies were a conditioning factor that affected “both sexual relations and family life, and even marriage and status, when they were single” (I-70 years old), and therefore, they value birth control. For the younger generations, “sex is a vital necessity that contraception allows us to enjoy without fear” (I-34 years). However, there is no consensus in regard to abortion, which is naturalised among the younger cohorts as another means of birth control and morally condemned by the older ones because it denies life.

Nor do the generations agree on sexual orientation. The older ones say that “there have always been people who have always been attracted to others of the same sex, but this changing. As [frequently as] it happens nowadays, this is not normal” (I-76 years old). However, the younger ones believe that “sexual orientation is not even relevant, it depends on appetite. You like—or fall in love with—the person, not their sex” (I-19 years old).

And the same phenomenon happens in consideration of transgender people. For the older ones, transgender identity represents “a radical fashion, and let’s see where it will lead us” (I-80 years old) since, “in all my life I have known one and suddenly a lot of them appear” (I-79 years old). For the younger ones, transgender individuals are “just another reality” (I-19 years old) with whom they coexist on a daily basis. Notably, from a descriptive point of view, three transgender women participated in this study, and all of them were under 25 years old.

For their part, middle-aged women do not fully understand either multiple expressions of sexuality or transgender experiences; however, they show less concern about this issue since, as one participant points out, “in all these years, if we have lived through anything, it has been changes. Changes…seemed like they were going to be a social debacle, like gay marriage, and you see, it has come to nothing; nowadays, it is normal” (I-48 years old).

With regard to the role of women within the family, intergenerational differences were also found. While the youngest women and those in the middle-aged group stressed that the overload from reconciling family and work responsibilities “implies a wear and tear that affects women to a greater extent, it harms them”, the older women spoke of the difficulty of mediating in the family, of acting as emotional support and of taking responsibility for transmitting moral values to their children. One respondent reported, “For me, the most difficult thing has been to be the helm of the family in times of disunity and difficulty” (I-80 years old). However, all three generations agree that there is an overload derived from the accumulation of productive and reproductive roles that affects women to a greater extent than men and that needs to be solved.

In the opinion of the participants, the younger women found it difficult to understand the film The Red Cross Girls and relate to the roles played by women. Only when the younger women were able to understand that marriage meant a glimpse of social and economic independence were they able to “accept the plot” (I-27 years old). On the other hand, these same women are able to “identify my mother in the anxiety experienced by the women in Pedro Almodóvar’s film, always in a hurry and [covered with] half-truths to justify the impossible [demands] that she had to face” (I-31 years old). Like the protagonist of My life without you, they believe that “all people, whether men or women, must fulfil their desires and dreams. It is fair that we have that opportunity; life owes it to us” (I-21 years old).

The middle-aged generation is more aware of the difficulties that older women have had to face since “I have had to rely on my mother” and “without her sacrifice and commitment I would not have been able to study or work afterwards” (I-57 years old). Thus, one woman observed, “Although the plot of the film The Red Cross Girls seems to me to be an exaggeration, I am not going to make judgements or assess the role of this generation of women since, in my opinion, life has been very unfair to them, and they have had the worst part of it” (I-55 years old). In response to Pedro Almodóvar’s film, the participants maintained that “the concept of women is somewhat removed from reality, but I do see myself reflected in the hurry, in the difficulty, in the constant anxiety. In that, yes” (I-48 years old). With regard to the film My life without you, the women show empathy for the protagonist, as one commented, “How many times have I not wished I could be [first], to be able to take care of myself, to be able to give myself some priority”; therefore, “in my opinion, it is important not to forget about oneself, without neglecting anyone but also without renouncing the self” (I-49 years old).

The older generation of women understands The Red Cross Girls perfectly since “it seems incredible now, but finding a husband and doing it well was very important” (I-79 years old). Thus, “[a good marriage] could mean the difference between a good life and a bad life” (I-67 years old). Another felt that the film was very exaggerated, as “the competitiveness between women, I don’t think it was like that. In my opinion, we helped each other more often than we harmed each other” (I-80 years old). Regarding Pedro Almodóvar’s film, they say, “I don’t understand it, it’s an exaggeration, it’s crazy” (I-72 years old). But they also observed, “I think that my daughter’s life was not easy. She had to give up a lot of things and she needed us a lot to raise the two children, but she is nothing like Almodóvar’s protagonists” (I-79 years old). However, this generation of women admires the protagonist of My life without you, as “this is what a woman should be like, devoted to others and aware of herself” (I-67 years old).

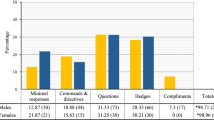

In order to facilitate the understanding of the results of this section, the interviews are searched for words or attributes that describe the genre for each generation, taking into account the different films, the selection is made on the basis of the significance criterion, “those that are most repeated, that is, those that generate most consensus in each age group” and Table 2 “Attributes describing gender, by generation and film” is drawn up.

The Red Cross Girls (1958) Woman on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988) My life without you (2003)

The evaluation of the project

The coordinators of the discussion groups held that the choice of a film screening has been ideal for analysing the evolution of gender roles since “cinema shows a moment in history and, therefore, through the images and the plot, it makes it possible to compare the present with the past and to notice the transformation, in this case, of the role of women” (DGFootnote 2 - 14). Furthermore, despite the temporal distance between the three films, “in all of them, the woman appeared in the centre of the scene, arguing her own life within the framework of the period” (DG- 15).

Of the three films, the one that aroused the greatest acceptance was My life without you since, regardless of age, all the participants have identified with some feature or experience of the protagonist. Thus, participants stated that “it is the one we liked the most” (GD- 10) or that “the protagonist could be any one of us, we all have longings to satisfy” (GD- 20).

The film Woman on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown introduces the issue of overburdened women, especially in terms of work-life balance but also in other aspects, such as the obligations of family support. The loss of mental health, anxiety and emotional imbalance of the female carer is mentioned; therefore, “it is important to share the burden” (GD-1) and “not to assume —on the part of men and society—that things are done alone” (GD-19).

With regard to the plot of The Red Cross Girls, there is a curious consensus among the participants, and it is that “the plot of the film is the culture of a generation, it is only possible to understand it from there” (DG-21) since the experience of women, which is their own experience, is determined by the time and place in which they have lived. This temporal distinctiveness can be seen in the plot of the three films selected by the researchers, “each one being the daughter of an era” (I-65 years old) and “showing different longings and dreams depending on the life of the woman and the man at the time the script was written” (I-29 years old).

Therefore, women in the focus groups valued the experience of the intergenerational film forum, as they all felt that they learned something, came closer and, despite the differences, developed a deeper understanding of the demands of each generation.

On the other hand, the coordinators of the discussion groups highlight the capacity of cinematographic language “both in the social construction of gender” (GD- 9) and “in the organisation of the debate” (GD- 5) since “the moving images allowed the participants to capture more explicitly complex aspects, such as the expectations of gender roles, i.e., what is expected of men and women in each historical period” (GD- 14). Thus, “cinema is a tool that unwittingly transports the audience to the background of things, i.e., to their true meaning”, so that it is possible to state that it is “a mediator between reality and fiction. It favours the symbolic aspects of actions through the vicissitudes of the characters and offers meaning to one’s own experience” (GD- 3).

In regard to the discussion groups, the coordinators held that the debate facilitated both “the achievement of the objectives, i.e., the analysis of gender roles in the past and present”, and the cognitive change regarding gender stereotypes in the women participants”, through the achievement of “certain unplanned transversal learning such as restructuring preconceived ideas, reflecting on the thoughts of others, increasing sensitivity towards the participants and their experiences, and incorporating their opinions” (GD-15). In addition, “group reflection has allowed me to experience empathy for other generations, situating the role of women in terms of gender expectations” (GD- 11) (see Figs. 1, 2 and 3).

Photo-essay composed of four images. Left, visual quote from a still of the film The Red Cross Girls by Rafael J. Salvia (1958), source: https://img2.rtve.es/i/?w=1600&i=1637836425976.jpg. On the right is a photograph by Angela Membrillo, followed by a photograph, top by Daniela San Martín and a photograph, below, by Ariana Palau García.

Photo-essay composed of four images. The first top photograph, by Irene Montaner Pérez, is titled “Self-portrait 2022”. Next, on the left is a photograph of Inés Bueno Pascual. On the right is a photograph by Irene Rodríguez de Rivera. Finally, a visual quote from a still of the film Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios by Pedro Almodóvar (1988), source: https://static.eldiario.es/clip/35cd9fb1-49d7-4728-a2c8-e13a256432ea_16-9-aspect-ratio_default_0.jpg.

Photo-essay composed of six images. First, above left holds a visual quote in a still frame from the film My life without you by Isabel Coixet (2003). Below are two photographs by Irene Rodríguez de Rivera. At the centre of the composition is photography by Eira Treviño, “Self-portrait (2022)”. On the right are two photographs of Maria Gabriela di Franco.

In terms of the objectives of the project, the persons who led the discussions held that, through the application of social work methods with the groups, the following objectives have been achieved:

An intergenerational approach was generated, i.e., “a greater understanding of the world and of women’s lives” (GD- 9). The groups had “a focus exposed not only to difference but also to that which unites us in gender” (GD-5), such as “the sense of belonging and the struggle to live in a society that disadvantages women” (GD-16). In fact, “one of the conclusions of the discussion groups is that throughout history, women have had to make a breakthrough and that even today, it is necessary to change the social model to avoid discrimination on issues such as co-responsibility, the reconciliation of work and family life and the dominant stereotype of beauty” (GD-18). For this reason, the coordinators held that “the intergenerational composition of the discussion groups has been a success” and that there has been a cognitive change with respect to gender stereotypes in the participants.

In this sense, the results of the evaluation of the project, regarding the success or suitability of the techniques, were discussed by the members of the GIMUPAY research group of the Complutense University of Madrid, reaching a positive consensus regarding their validity.

However, despite this achievement, during the project, there were difficulties that the coordinators had to overcome, such as fears associated with catching COVID-19, sharing space, and meeting with other people, which manifested as impossibilities: “On occasions, some participants did not attend and were given the option of participating online” (GD- 14). Furthermore, “some participants would have preferred to choose the films according to their own definition of women and analyse why they chose them, but this would not have worked” (GD-9). Finally, the lack of knowledge of feminist thought among the older generations made it necessary to “construct a conceptual framework that was provided by the younger generations” (GD- 6).

Discussion

It should be noted that the results of this study are not intended to generate inference, it is a qualitative work focused on achieving a cognitive change regarding gender stereotypes in the participants, it is possible to affirm that the gender attributes offered by the women participants present in Table 2 show that the mentioned change has taken place, since, the stereotypes were affected, however, it is not possible to speak of a total transformation of the concept and attributions of gender, since the stereotypes are still present in the population.

However, if we look at the studies of the IMSERSO (2005; 2018), INE (2022) and Family Caregiver Alliance (2022), we can observe that a reality of reduced stereotypes is not so far away since the number of women carers has been decreasing at the same time as the number of care services for dependent adults has increased. Additionally, the social presence of women in the political, public, social and professional spheres has increased. As Martínez-Vérez, (2011) and Raya (2007) point out, this redistribution does not mean that women no longer care but rather that they do not care alone. There is therefore a principle of co-responsibility that was acquired under the constant pressure of the feminist movement in Spain, which in turn has made it easier for the younger generation of women to aspire to greater freedom.

However, despite the similarities detected, it is important to highlight that this work is limited to collecting the discourses of women belonging to three different generations who participated in the debate framed by the project “Women in the spotlight”. These women discussed the changes that have occurred in gender roles in accordance with the principles and approaches of social group work, using a film-based discussion stimulus that was designed in the Master’s Degree in Art Education in Social and Cultural Institutions to generate an atmosphere of reflection and awareness (Segado and García-Castillo, 2022).

Thus, the first thing that can be observed is the evolution of feminism itself; in this sense, no one questions the equality of rights between men and women, but there is disagreement on all that is entailed by the labels “man” and “woman” (Varela, 2019). It is possible to affirm that each generation has been affected by one of the feminist waves, from movements toward awareness of equality and difference (Sanders, 1999; Thornham, 1999; Sendon, 2000 and Hooks, 2000) to the fourth wave (Bulter, 1990 and Cano, 2021). Consequently, the women are aware of the difference both in the experience of the role itself and in gender expectations (Varela, 2019). Thus, while older women recognise that they have perceived gender as a natural and objective attribute associated with sex, younger generations even question its existence.

In regard to defining gender roles and expectations, the differences appreciated by the participants are associated with social construction (Bover, 2004), taking into account the age and place of birth of the women (Loscertales and Núñez, 2009).

In this sense, film, as a tool for reflection and debate, successfully introduced phenomenological doubt on the ontological nature of gender, giving rise to a new shared discourse on the influence of cultural variables in the social construction of gender. In this new discourse, it is possible to appreciate a greater rapprochement and empathy between the participants than existed before.

Approaching a film from another generation means moving away from what we consider normal to enter into another perspective (Raquejo and Perales, 2022), generating empathy by appreciating not only the evolution of gender but also the social imprints on all women (Guil, 1998).

The discussion groups have also borne the expected fruit in that they brought the gender debate to the table, provoking consensus and situating the existing differences in the historical circumstances of the participants, i.e., in the cultural imprint of each generation. Thus, the discussion groups also contributed to bringing the three generations emotionally closer together.

Finally, from a methodological point of view, the techniques chosen to collect and analyse the data have made it possible to show how social work applied through the debate over filmic arts has contributed to interdisciplinarity by creating an intervention in an emerging space. This has allowed researchers to approach intersubjectivity and to contemplate how “the person, in the game of social interactions, is in a constant process of negotiation, developing symbolic exchanges, in a space of intersubjectivity” (Spink and Medrado, 2000, p. 55).55), with film being the resource that has favoured this development (Moreno, 2022).

Finally, it is important to note that the data collection was not carried out by independent assistants, the coordinators were involved in the project. In this sense, the group discussions and the data on their results may have been biased in the direction of the project objectives. However, the findings obtained were reviewed by the research group GIMUPAY of the Complutense University of Madrid. They can be considered project-external evaluation experts, and they reached a positive consensus regarding the evidence found that supports the suitability of the techniques employed. A formal limitation to the independence of their judgement, though, may be that they are from the same university as the researchers.

Conclusions

Conclusions related to the specific objective 1- to compare gender and its social construction across generations and to generate a cognitive change regarding gender stereotypes in the women participants

Feminist thought has had an impact on the lives of Spanish women, but it has done so differently from the European context, given that the Franco dictatorship generated an involution of rights that mainly affected the female gender. Thus, as seen in the debate, older women say that for them, gender has been an unquestioned reality that they never stopped to consider, as being a woman implied roles and responsibilities, such as motherhood, caring for the family, uniting the family, and relegating their own needs. However, younger women, affected by the fourth wave of feminism, recognise the social construction of gender and the need to change everything that harms women, hinders equality and does not facilitate self-care.

There is a great discrepancy between the roles that women have to fulfil in society. Thus, while younger women hold that there should be no roles associated with gender and believe, in accordance with fourth wave feminism, that it is necessary to abolish this label so that the social stereotypes that have historically harmed women disappear, older women do not understand how motherhood and care can be shared equally between men and women, as they find a feeling of fulfilment in their role as wife and mother. Older women also hold that it is logical that the care of the family, the union of the marriage and the reconciliation of the differences between parents and children should fall on women, as they are naturally more peaceful and sentimental and are more prepared to care for others. For their part, women of the intermediate generations emphasise the need to make visible the difficulties women face in reconciling work and family and hold that it is necessary to continue to demand state support in the co-responsibility of care.

In regard to the difficulties that women face or have faced, older women hold that the main problem in their daily lives was the responsibility of morally and emotionally supporting the family, especially bearing in mind that in the 1950s and 1960s, several generations lived under the same roof and the influence of the in-laws was important. On the other hand, younger and middle-aged women hold that their main difficulty is a work-life balance that forces them to postpone motherhood indefinitely, sometimes even renouncing it, to gain economic independence and professional development. In other words, they feel the weight of the glass ceiling, and thus they are forced to depend on extended family, i.e., grandparents, to care for their children, especially when there are insufficient resources for a work-life balance.

There is no agreement on sexual orientation either: while younger women admit to having questioned their own feelings on this issue because they hold that socialisation favours heterosexuality and that it is appropriate to question this norm, older women and those in the middle-aged group hold that sexual orientation is what it is. In this sense, all generations admit that homosexuality exists, but not to the same degree: younger and middle-aged women say that it is as normal as heterosexuality, but older women think that it is overemphasised.

The same dissent appears with pansexuality, so while for the younger generations, gender does not play a role in sexual attraction since you fall in love with a personality and not with one sex or the other, allowing the sexual object to change from male to female and vice versa, older women and women in the middle-aged group believe that gender does play a role in the choice of sexual object. Women in the middle-aged generation state that they are not concerned about this issue.

Transgender people are part of the reality and coexistence of the youngest women; thus, the three women participants who defined themselves as transgender were all under 25 years old. However, for older women, people with diverse gender identities escape the construct of femininity.

The women participating in this study, regardless of their age, agree on the impact and use of contraceptive methods by women, especially to avoid unwanted pregnancies. They also agree on the impact of the time and place of birth on the role expectations and therefore on the experience of each woman.

In the light of the data provided, it is possible to conclude that there has been a cognitive change in the women participants with respect to gender stereotypes, since the attributes they offer to describe the female gender show a transformation, the appraisals they make are not so radical with respect to the other generations of women and words and expressions appear that indicate understanding and even gratitude with respect to the role they have played in the social transformation of women.

Conclusions related to the specific objective 2- to analyse the suitability of the techniques used in terms of their reflective and representational capacity

The choice of film has worked as a mediating tool to introduce a debate about the social construction of gender roles and expectations. It allowed women from three different generations to generate a dialogue and review their approaches to what they consider obvious and objective, creating a common discourse of acceptance that implies a recognition of the difficulties of each generation. This intergenerational empathy serves as a basis for establishing a relationship prone to solidarity in sisterhood.

The triad of films chosen allowed us to observe, through the imaginaries that sustain them, the evolution of gender roles in Spanish society by putting ourselves in the shoes of the protagonists.

The films also enabled the participants to carry out a diachronic analysis of the impact of feminist thought and the role of women in furthering this impact. In this sense, all generations agree in affirming that there are anonymous women who, by exercising the roles that corresponded to them by age, have allowed others to study and exercise a professional career. There was consensus that it is necessary to recognise this anonymous role, thus bringing about intergenerational rapprochement.

On the other hand, film language is considered to play an important role in the social construction of gender since it allows us to access the symbolic background of concepts, i.e., the imaginary that gives rise to stereotypes and prejudices and is therefore particularly useful for critical reflection on the role of women.

The use of intergenerational focus groups was also successful in achieving the objectives of critical analysis, delving into the social construction of gender roles and expectations. According to the group coordinators, it was not easy to set aside gender stereotypes of woman in order to make room for the circumstances that determine what we do and who we are.

Finally, it is important to note that certain unforeseen transversal skills were acquired, such as the restructuring of one’s own concepts, newly understood as stereotypes and prejudices, with nuance from the debate. These skills gave rise to the processes of otherness, first, and empathy, later.

Data availability

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during this study are in the property of the authors and are available upon reasonable request.

Notes

The letter I- stands for “Informant”, and the following number refers to age.

The letters DG- stand for “Discussion group”, and the number that follows refers to the order of the group in the database.

References

Almodóvar, P (1988) Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios [Film]. El Deseo, LaurenFilm S.A

Alonso LE (1999) Sujeto y discurso: El lugar de la entrevista abierta en las prácticas de la sociología cualitativa. En Juan Manuel Delgado y Juan Gutiérrez (Coord.) Métodos y técnicas cualitativas de investigación en ciencias sociales, Síntesis, Madrid, pp 225–240

Arránz, F (2020) Estereotipos, roles y relaciones de género en series de televisión de producción nacional: un análisis sociológico. Instituto de la Mujer y para la Igualdad de Oportunidades. https://www.inmujeres.gob.es/areasTematicas/AreaEstudiosInvestigacion/docs/Estudios/Estereotipos_roles_y_relaciones_de_genero_Series_TV2020.pdf

Bover A (2004) Cuidadores informales de salud en el ámbito domiciliario: percepciones y estrategias de cuidado ligadas al género y a la generación. Universitat de les Illers Balears. Unpublished doctoral thesis

Bulter J (1990) El género en disputa: el feminismo y la subversión de la identidad. Barcelona. Paidós

Canales M, Peinado A (1995) Grupos de discusión. En José Manuel Delgado y Juan José Gutiérrez (Coord.) Métodos y técnicas cualitativas de investigación en ciencias sociales. Síntesis, Madrid, pp 288–316

Cano M (2021) Judith Butler: Performatividad y vulnerabilidad. Barcelona. Shackleton Books S.L

Coixet I (2003) Mi vida sin mí [Film]. Coproducción España-Canadá; El Deseo, Milestone Entertainment, Antena 3 Televisión, Vía Digital

Cruzado Á (2011) Mujeres de cine: directoras y nuevos modelos de feminidad en la gran pantalla. In: Ramírez-Almazán En D, Martín-Clavijo M, Aguilar-González J, Cerrato D (eds), La querella de las mujeres en Europa e Hispanoamérica, Sevilla. ArCiBel Editores, S. L, Vol I, pp 287–304

Declaration of Helsinki (2008) Ethical Principles for Research Involving Human Subjects. 59th General Assembly, Seoul, Korea, http://www.wma.net/

Denzin N, Lincoln Y (1998) Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials. Teller Road, Thousand Oaks. Sage

Family Caregiver Alliance (2022) Health Conditions. https://www.caregiver.org/caregiver-resources/health-conditions/

Guil LA (1998) El papel de los arquetipos en los actuales estereotipos sobre la mujer. Comunicar 11:95–100. https://doi.org/10.3916/25247

Hammersley M, Atkinson P (1994) Etnografía: Métodos de investigación. Barcelona. Paidós

Hooks B (2000) Feminisms for everybody: passionate politics. Boston. South End Press

IMSERSO (2005) Cuidados a las personas mayores en los hogares españoles. El entorno familiar. Serie dependencia. Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales

IMSERSO (2018) Encuesta mayores 2018. Ministerio de Derechos Sociales y Agenda 2030. https://imserso.es/el-imserso/documentacion/estadisticas/informe-2018-personas-mayores-espana

INE (2022) Mujeres y Hombres en España. Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. https://www.ine.es/ss/Satellite?L=es_ES&c=INESeccion_C&cid=1259926668516&p=1254735110672&pagename=ProductosYServicios%2FPYSLayout¶m1=PYSDetalle¶m3=1259924822888

Kvale Z (2011) La entrevista en investigación cualitativa. Madrid. Morata

Lefevre F, Lefevre AM (2014) Discurso do sujeito coletivo: representações sociais e intervenções comunicativas. Contexto Enfermagem, Florianópolis 23(2):502–507. IC.2009.01.20

López A (2010) Hacia un modelo teórico del Trabajo Social con grupos. In López A (ed) Teoría del Trabajo Social con grupos. Madrid. UNED

Llopis R (2004) Grupos de discusión. Barcelona. ESIC

Loscertales F, Núñez T (2009) La imagen de las mujeres en la era de la comunicación. I/C - Revista Científica de Información y Comunicación 6:427–462. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072014000000014

Martínez-Vérez, M. V (2011) Los cuidadores informales en la enfermedad de Alzheimer. Procesos, claves y alternativas (un estudio en la ciudad de A Coruña). Universidade da Coruña. Unpublished doctoral thesis

Moreno R (2019) Feminismos. La historia. Madrid. Akal

Moreno A (2022) Mediación artística y arteterapia. Delimitando territorios. Encuentros. Revista de Ciencias Humanas, Teoría Social y Pensamiento Crítico, 15:32–45. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5979840

Puebla B, Carrillo E (2011) La mujer en el cine de Alejandro Amenábar: pinceladas de una nueva feminidad en el cine español. Razón y Palabra 78:1–15. http://www.razonypalabra.org.mx/N/N78/02_PueblaCarrillo_M78.pdf

Puigvert L, Redondo G (2005) Feminismo dialógico: igualdad de las diferencias, libertad y solidaridad para todas. In: J. Giró (ed.) (2005) El género quebrantado. Sobre la violencia, la libertad y los derechos de la mujer en el nuevo milenio (pp. 206-238). Universidad de la Rioja

Raquejo T, Perales V (2022) Arte ecosocial. Otras maneras de pensar, hacer y sentir. Plaza y Valdés, Madrid

Raya E (2007) Políticas sociales en el siglo XXI: cambios en la atención a las personas de edad. In: J. Giró (Eds.) Envejecimiento, autonomía y seguridad (pp. 81-114). Universidad de la Rioja

Reidl LM (2012) Research design in education: current concepts. Research Methodology in Medical Education 1(1):35–39. https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/iem/v1n1/v1n1a8.pdf

Rincón A (2014) Representaciones de género en el cine español. Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales. Universidad del País Vasco. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Madrid

Ruíz JI (2012) Metodología de la investigación cualitativa. Universidad de Deusto

Salvia RJ (1958) Las chicas de la Cruz Roja [Film]. Asturias Films

Sanders V (1999) Firts wave feminism. In: Gamble En S (ed) The icon critical dictionary of feminism and postfeminism, London. Icon Books, pp 16–28

Segade S, García-Castillo (2022) Fundamentos del Trabajo Social. Aranzadi, Madrid

Sendon V (2000) ¿Qué es el feminismo de la diferencia?. Buenos Aires. Ediciones La mariposa y la iguana

Spink MJ, Medrado B (2000) Práticas discursivas e produção de sentido no cotidiano. En M. J.Sipnk, (org.). Aproximações teóricas e metodológicas 2. ed. (pp. 41-61). Sao Paulo. Cortez

Thornham S (1999) Second wave feminism and postfeminism. In Gamble S (ed) The Icon critical Dictionary of feminism and postfeminism. Icon books, London, pp. 29–42

Vallés M (1999) Técnicas cualitativas en investigación social. Metodologías de reflexión y práctica profesional. Madrid. Síntesis

Varela N (2019) Feminismo 4.0. La cuarta ola. Barcelona. Edic.B

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors declare that they have contributed equally in the following sections: 1. Have made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; and 2. Been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and 3. Given final approval of the version to be published. Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content; and 4. Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests with respect to the research, implementation and publication of this article.

Ethical approval

This project is carried out as part of the teaching activity of the master’s degree in Art Education in Social and Cultural Institutions in Faculty of Fine Arts and therefore has the approval of the Research Ethics Committee University Complutense of Madrid. Project de ref. PID2019-104506GB-I0 Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades).

Informed consent

The participants have been informed and have signed an informed consent document. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martínez-Vérez, M.V., Albar-Mansoa, P.J. Gender roles in Spanish cinema: a critical and creative process around the word ‘woman’. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 845 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02324-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02324-3