Abstract

Hybrid networks of actors such as policymakers, funders, scholars, and business practitioners are simultaneous producers and consumers of evidence use. While this diversity of evidence use is a strength, it also necessitates greater collaboration among interested parties for knowledge exchange. To address this need, we investigate how ecotones, which are hybrid networks operating in the transitional area between two distinct ecosystems, such as academic research and policy ecosystems, must involve, disseminate, and integrate different types of knowledge. Specifically, our research aims to unpack how an ecotone’s knowledge brokerage function evolves over its lifecycle. This paper presents the findings of a phenomenological investigation involving experts from the policy and academic research ecosystems. The study introduces a three-stage maturity transitions framework that outlines the trajectory of the brokerage function throughout the ecotone’s lifecycle: i. as a service function, ii. a programme-partnership, and iii. a network of networks. The paper contributes to the theory of knowledge brokerage for policy-making. We reflect on our findings and discuss the theoretical contributions within an ecosystem approach and their associated research and policy implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Evidence use is important in policymaking and refers to the process of incorporating empirical data, research insights, and expert analysis or other forms of evidence into the policy decision-making process (Oliver and Boaz, 2019; Oliver et al., 2022). This plurality of sources of evidence is welcomed by policymakers, funders, scholars and business practitioners and we see a global interest in evidence-based policymaking to address complex and pressing global challenges. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) are prime examples of global initiatives that emphasize the importance of evidence-based decision-making. While this diversity of evidence use is a strength, it also requires greater forms of collaboration among interested parties in terms of knowledge exchange.

Knowledge brokering helps to translate knowledge, align, and integrate information needs and outputs across stakeholders from different backgrounds (Pielke Jr, 2007; Oliver and Boaz, 2019). Knowledge brokerage literature has offered insights into how collaboration is facilitated by individuals who act as brokers (Pielke Jr, 2007; Meyer, 2010; Boari and Riboldazzi, 2014) and boundary organizations (O’Mahony and Bechky, 2008; Perkmann and Schildt, 2015; Boswell, 2018).

Within this body of work, there is recently increased interest in the transitional area between two ecosystems—known as an ecotone—where hybrid networks of actors in either academic research or policy ecosystems variously interact to exchange knowledge and span the boundaries between the two ecosystems (Seidman, 2009; Ghazinoory et al., 2021; Massa et al., 2022). Recent examples in the UK, include the Cambridge sub-region, which attracts a critical mass of high-tech R&D and technology commercialization, creating a rich ecotone for targeted innovation creation and knowledge exchange (Viitanen, 2016).

An ecotone, originating in ecology, signifies a transitional area where distinct ecosystems blend, resulting in unique features (Heaton et al., 2019; Ghazinoory et al., 2021; Hoffmann et al., 2022; Massa et al., 2022). In knowledge exchange and boundary work, it represent a boundary or interface where diverse groups (scientists, policymakers, practitioners) collaborate. An ecotone’s “knowledge brokerage function” refers to the role it plays in facilitating the exchange of knowledge and information between these different groups. This function fosters effective communication and collaboration, akin to an ecotone’s role in facilitating ecological interactions. It bridges the gap between research and action, promoting informed policy and practice. For instance, Massa et al. (2022) identified several ecotone brokerage functions, namely, conflict resolution, spreading knowledge, linking idea fragments, connecting problems to solutions, expanding the network, and strengthening the network.

Within this theoretical framework, we investigate how these ecotones need to involve, disseminate, and integrate different types of knowledge. Specifically, our research seeks to unpack how ecotones’ knowledge brokerage evolves over their lifecycle. While previous studies have advanced our understanding of how organizational actors evolve as knowledge brokers (Boari and Riboldazzi, 2014) within the confinements of boundary organizations, our focus concentrates on the structural determinants of ecotones’ knowledge brokerage function.

Whilst we know that ecosystems grow, decline and can be reborn (Heaton et al., 2019), there is a gap in how an ecotone’s knowledge brokerage function evolves by the specificities of the wider ecosystem landscape. Informed by this theoretical background, we ask: “How does the knowledge brokerage function of ecotones evolve to meet the needs of academic research and policy ecosystems?” To answer our research question, we took an ecosystem perspective and conducted a phenomenological study to explore how the knowledge brokerage function might evolve over the ecotone’s lifecycle.

The main contribution is a three-stage framework that explains how the knowledge brokerage evolves and matures over time. While previous studies have provided theoretical and empirical insights, they focused on the network’s governance structure (Provan and Kenis, 2007), or took a static view of the ecotone’s brokerage function (Fitzgerald and Harvey, 2015). Our findings explain how the brokerage function of an ecotone develops and matures and demonstrate the developmental stages that an ecotone may undergo to operationalize a mature knowledge brokerage function. The second contribution relates to the particular outputs for research and evidence systems. Ecotones with an immature knowledge brokerage function as demonstrated in Stage 1 will inevitably contribute to a fragmented knowledge base. However, as the knowledge brokerage matures into Stage 2 it can form diverse evidence on a specific policy area, and in Stage 3, the knowledge brokerage can achieve cross-pollination of research evidence on multiple policy areas.

Background

This section briefly outlines the brokerage literature and how the theory has evolved to consider an ecosystem approach to knowledge brokering. We categorize three units of analysis within brokerage literature, starting with the individual broker, then boundary organizations, and finally, ecotones.

Knowledge brokering is particularly important for policy-making and Cairney and colleagues have offered many contributions in this space (Cairney et al., 2016; Cairney and Kwiatkowski, 2017; Cairney and Oliver, 2017; Oliver and Cairney, 2019). This research explains how academics may create impact from their research; change policy; develop collaboration strategies for knowledge co-production; and improve their academic–policy relations.

Within this stream, the knowledge brokerage literature has focused on the role and ontology of boundary actors—known as brokers. The skills needed for boundary action have been extensively discussed in the management and policy literature (Tushman and Scanlan, 1981; Williams, 2002; Zhao and Anand, 2013; Boswell, 2018), as well as in other contexts such as healthcare. For example, Ayatollahi and Zeraatkar (2020) showed that knowledge exchange and management are strategic resources in healthcare organizations; they identified several factors such as organizational culture, and information technology that influence the success of knowledge exchange.

Earlier studies have theorized on how brokers broker (i.e., brokerage as a process of intermediation, brokerage as a direct flow of information) (Quintane and Carnabuci, 2016) or what brokering involves (Meyer, 2010). Particularly relevant is the work of Pielke (2007), which distinguished the theoretical issues of brokerage practice at the science–policy interface. Several studies have built on this work which advances among four broker archetypes (Duncan et al., 2020; Cairney and Oliver, 2020; Gluckman et al., 2021).

Another stream of studies has taken an organizational approach to knowledge brokering. The construct of boundary organizations emerged to describe how organizations that held divergent interests discovered areas of convergent interest and could collaborate by creating a boundary organization (O’Mahony and Bechky, 2008; Boswell, 2018). The International Structural Genomics Consortium shares many features with organizations characterized as boundary organizations (Perkmann and Schildt, 2015). Recent evidence suggests that boundary organizations are subject to power plays and politics (MacKillop and Downe, 2023), regarding which initiatives to pursue and how this may impact the future of the organization and its relationship with policymakers. They also face tensions and negotiations regarding determining what counts as evidence and who should be called upon to provide that evidence (MacKillop et al., 2023).

A third stream of research has taken an ecosystem or network perspective. Provan and Kenis (2007) research offered a conceptual model that explains how networks are governed. We are most interested in this unit of analysis as it is gaining increasing attention (Ghazinoory et al., 2021; Hoffmann et al., 2022; Massa et al., 2022).

Within this work, ecotones form the interface between two or more disparate ecosystems, featuring a mix of different types of communities, usually containing a larger variety of species (i.e., actors) than the separate ecosystems (Ghazinoory et al., 2021). In this literature, it is important to connect the knowledge ecosystem (science) with adjacent ecosystems (policy or business) in a way that the respective knowledge and capabilities can be exchanged and recombined, causing a reciprocal cross-pollination (Massa et al., 2022). Ecotones are hybrid networks situated at the interface between two or more disparate ecosystems. They feature a mix of different types of communities, e.g., science and policy, or science and business. Ecotones contain a larger variety of actors than separate ecosystems (Seidman, 2009). Their boundaries are not strictly defined as boundary organizations; their main purpose is to support exchanges between adjacent ecosystems.

We see globally an interest in network brokerage facilitated by ecotones. Recent examples of ecotones brokerage services include Berkeley at the University of California, Kendall Square at MIT, the Interuniversity Microelectronics Center in Belgium, and Cambridge Enterprise in Cambridge, UK (Leten et al., 2013; Heaton et al., 2019; Massa et al., 2022). These hybrid networks of actors revolve around a research organization as the center of gravity and include science parks, incubators, technology transfer offices, venture capitalists, consultants, startups or incumbents. Furthermore, they all operate in the transition (non-geographic) area identified by the ecotone. These actors relate to the academic research, policy, or business ecosystems yet span their respective boundaries (Massa et al., 2022).

Research gap

In sum, traditional brokering literature has provided insights as to who acts as a broker (Molina-Morales et al., 2016), and what brokers do (Meyer, 2010), shedding light on the importance of individuals acting as brokers. The brokerage literature also has identified the role of organizations acting as boundary spanners (O’Mahony and Bechky, 2008), and because of their permanent nature, they are durable structures that encourage parties to collaborate and pursue mutual goals. However, from an organizational architecture perspective, boundary organizations may be limited in effectively responding to political or institutional barriers (MacKillop and Downe, 2023). As a result, policymakers or businesses may resist engaging with external organizations and bureaucratic hurdles may impede collaboration.

To overcome this hurdle, network brokers have access to a wide range of networks, including policymakers, researchers, and practitioners. This diversity of network actors operating in the boundaries of an ecotone (Massa et al., 2022) can help overcome the resistance of policymakers or practitioners to engage with external boundary organizations because network brokers can leverage their existing relationships and credibility within these networks. National Institute for Health and Care Research Applied Research Collaborations (ARCs) (formerly known as Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care) offered great insights on describing partnerships, vision and values, and structures and processes facilitated within the boundaries of these networks (Kislov et al., 2018). Despite these advancements, ARCs offered a static view (Fitzgerald and Harvey, 2015) of how an ecotone could facilitate knowledge brokerage services.

A significant gap in our understanding lies in the limited evidence available regarding the evolution of ecotones’ knowledge brokerage function and how they can adapt to provide the necessary services for more effectively facilitating knowledge exchange between adjacent policy and science ecosystems. To address this gap, we approach this issue through an ecosystem lens, drawing upon the ecosystem approach as outlined in previous research (Heaton et al., 2019; Ghazinoory et al., 2021; Hoffmann et al., 2022), and responding to recent calls for research (Massa et al., 2022) that emphasize the need to unpack and explore how the relationship between these hybrid networks (referred to as ecotones) and their knowledge brokerage activities may evolve throughout the ecotone’s lifecycle.

Methodology

The purpose of this qualitative phenomenological study (Creswell and Poth, 2016) is to understand the knowledge brokerage function in the boundaries of an ecotone as it evolves for individuals in the academic research and policy ecosystems. At this stage in the research, the knowledge brokerage function is generally defined as the facilitation of information exchange and collaboration between academic research and policy domains within the dynamic context of an ecotone. Phenomenology is an appropriate research design for developing a composite description of the experiences of individuals around a particular phenomenon.

In terms of reflexivity, this study follows Moustakas’s (1994) phenomenological approach which focuses less on the interpretations of the researcher and more on a description of the experiences of participants. From a research participant’s point of view (individuals in the academic research and policy ecosystems), the phenomenon in the study would be the knowledge brokerage function within the boundaries of an ecotone as it evolves. They are the ones directly involved in or experiencing this phenomenon, so their perspective and understanding of how knowledge brokerage works within this specific context would be of particular interest in the phenomenological study. As such, the authors acted as independent observers of the process and temporarily suspended their preconceptions, beliefs, biases and assumptions about the phenomenon under study to engage in the phenomenological analysis (Moustakas, 1994).

Data collection

Primary (survey, interviews, direct observations) and secondary data sources (presentation slides, reports, websites) were collected to address our research question. Below we outline the data collection methods and sampling strategy for each.

Survey (N = 127)

The research team launched an exploratory survey in April 2022 and employed purposive sampling to identify individuals from a wide breadth of the policy and academic research communities around academic–policy engagement. The survey was open to both individuals with no prior engagement in academic-policy partnerships and individuals with substantial experience in such partnerships. Participants were recruited through institution-wide emails, contacting individuals who had previously expressed an interest in providing their views, social media (i.e., LinkedIn and Twitter), newsletters, policy and academic networks. 127 valid responses were received (London policymakers = 67, academic researchers = 60). The survey questions can be found in Supplementary Note S1. The analysis of survey responses was used to draft the semi-structured interview questions. Follow-up emails were sent to those who indicated in their survey responses that they would like to participate in additional interviews.

Semi-structured interviews (N = 107)

We conducted interviews with 107 participants spanning 30–90 min (London policy-makers = 49, Academic researchers = 58) between June 2022 and September 2022. The interview topics can be found in Supplementary Note S2. Participants were sampled across different disciplines, institutions/teams and policy areas, which helped to minimize bias and obtain responses from individuals with extensive experience in the field but also to accommodate the views of individuals with little to no experience engaging with the other community. We used Microsoft Teams auto-transcription function during the interview sessions. After each interview, the research team manually checked the transcripts for accuracy. In parallel with data collection, we inserted the transcripts into NVivo and pseudonymized them for analysis. Data collection was concluded once data saturation had been reached.

Direct observations (N = 1950 h)

The two authors were recruited as Policy Fellows embedded within City Intelligence Unit in the Greater London Authority (GLA), in the UK. The Fellowship was a 12-month pilot to create a dedicated knowledge brokerage function to build knowledge networks between London policy-makers and academics in London and beyond. The authors were members of the newly formed executive team of the London Research and Policy Partnership (LRaPP) (2023). LRaPP is an innovative experiment that seeks to connect London’s universities and the London government to work more closely together to address the capital’s strategic challenges. The study spanned over one year (March 2022–March 2023). Whilst the intention of this fellowship was to develop the future brokerage function of LRaPP, only the initial exploratory findings pertaining to individuals’ experiences of the wider academic research and policy ecosystems are reported in this paper. The purpose of the data collection at this stage was to obtain participants’ perspectives on their broader and former experience of research/policy engagement.

Archival data

We had access to a diverse archival set of data, such as programme booklets outlining the scope of research-academic partnerships, PowerPoint presentations, term of reference documents, invitations to submit proposals, reports on policy engagement mapping, internet sites on research and policy engagement initiatives, and blogs that proved useful in identifying the key actors and partnerships.

Data analysis

The two fellows independently analysed the database with the transcripts. Thematic analysis of the interview transcripts was undertaken using an inductive approach (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Initially, we used open coding, and 613 nodes were created in NVivo by the two fellows. The 613 nodes were clustered into larger categories to identify possible relationships and links among the nodes. The initial 613 nodes were aggregated into 74 second-order codes in NVivo. To better make sense of the data, we engaged with the literature of organization design, and knowledge co-production and brokering to identify what observations to look into further and delimit our coding (Locke et al., 2020). We compared the open codes with the literature and proceeded to substantive coding of our data into aggregate dimensions using concepts from organization design and knowledge co-production and brokering reference points. These streams of literature provided concepts used to perform axial coding and identify patterns in and relationships between codes. Table 1 outlines the parameters we used to define each stage of our framework.

After investigating the literature and our empirical data simultaneously we derived three clusters (Collaborative Knowledge Exchange and Facilitation; Resources, capabilities, and practices; Brokerage focus, Response, and Knowledge Utilization) to describe the three stages an ecotone’s knowledge brokerage function might evolve.

To further validate our findings, we presented our findings to actors of both ecosystems on 13 separate occasions including, workshops, executive board meetings, lunchtime policy seminars, policy forums, academic seminars, and policy and academic conferences, to obtain feedback and further refine our framework.

Findings

In the following sections, we present the three maturity stages of an ecotone’s brokerage function that are derived from our empirical findings. Each stage of the framework is supported by excerpts from our data set (Tables 2–4).

Stage 1: Service-function model

Stage 1 represents the foundational phase where the ecotone lays the groundwork for more advanced knowledge brokerage functions. It provides essential services to initiate collaboration, disseminate information, and begin trust-building efforts. As it matures through the subsequent stages, it will expand its capabilities and evolve into a more sophisticated knowledge brokerage entity. In a Stage 1 environment, the participants reported that the ecotone’s brokerage function provided basic ad-hoc services to their adjacent ecosystems and focused on ‘quick wins’.

Collaborative Knowledge Exchange and Facilitation

Our participants offered limited accounts that accurately reflected how the brokerage mode of an ecotone might operate at this stage. Looking at the brokerage mode of LRaPP in Stage 1 as the closest example in our dataset; its primary function was to establish the groundwork for effective knowledge brokerage and collaboration. The emphasis was on providing basic brokerage services such as mapping interest across the ecotone and support to initiate interactions and build the confidence of ecotone actors from academic research and policy ecosystems. The brokerage function served as a facilitator, encouraging interactions and communication between actors from both ecosystems. It helped bridge the initial communication gaps and fostered connections.

Regarding convening, the participants viewed the brokerage function as predominantly raising awareness within the ecotone’s boundaries, identifying and aligning the strategic priorities for research and policy across the wider ecosystems. Convening at this stage was a light touch. The brokerage function logged interest coming from actors from across the policy and academic research ecosystems and the ecotone. For example, LRaPP informally delivered the brokerage service and placed efforts on identifying researchers from LRaPP’s existing networks. The interview participants mentioned that funding was scarce, an ecotone at this stage of maturity would have access to small amounts of funding from across the ecosystems it served. Funding could be used, e.g., as an open challenge for policy and academic research teams that want some research done. A project example that was funded through LRaPP’s channels was the “New Deal for Young People Mentoring Research”, which was funded by the Higher Education Innovation Fund (HEIF). LRaPP secured HEIF funding from the University of London, one of the founding organizations of the partnership. LRaPP issued an invitation to submit proposals (see also consultation practices below) to university researchers setting out how they would approach the research and their qualifications. The call was issued on LRaPP’s website and on social networks e.g., LinkedIn, to draw interest from the wider network of academic researchers specializing in this area of research.

Resources, capabilities and practices

Resource structuring at this stage concerned ongoing activities by which ecotones acquired knowledge brokerage resources. Participants explained that ecotones could not afford acquiring knowledge brokerage resources externally, so it fell more around identifying experts in particular research and policy areas through existing informal networks and building on these ongoing relationships. The participants agreed that building on existing informal networks was the most affordable way for ecotones to acquire resources. Capability building was immature because the brokerage function had not yet secured buy-in at large from academics nor policy-makers, and neither of the ecosystem actors was yet committed to joint initiatives.

Regarding engagement practices, these were limited because of the limited resources and funding. Most participants identified consultations as the most prominent practice of the brokerage function. For example, policy participants explained how they resorted to consultancy-like approaches when engaging with an ecotone’s brokerage function because there was no established network to enable them to engage in different ways when their work was urgent. The second most prominent engagement practice was engaging with academics informally e.g., through long-standing relationships. A policymaker explained:

“I was happy asking [London Higher Education Institution] because I knew this was one of their priorities, it was on their website. But that’s only because I went there, and I met the professor, and I knew that there was a person that wanted to be more involved in policymaking.” I-8, Project Manager, Policy Institution.

Brokerage focus, response, and knowledge utilization in brokerage

The participants mentioned that the primary focus of knowledge brokerage was predominantly on building the confidence of each set of actors in the different ecosystems. This was done by engaging in ‘quick win’ projects; projects that demonstrated early results or potential alongside scoping and developing ideas/proposals for more strategic interventions/actions to be delivered over the medium to long-term. Ecosystem actors wanted to see how the knowledge brokerage function worked and how it immediately impacted their work. In that sense, a policy area with a sense of urgency would achieve this result. A policymaker explained:

“From a time point of view, because I think if there’s an urgent deadline rather than just open-ended, which can take months or years you know you’ll never get the people—they will never quite get there. [A policy area with a sense of urgency] that’s what I think is more attractive to people.” I-13, Head of Engagement and Operations, Policy Institution.

Participants stated that because the knowledge brokerage function was not yet established at this stage, the brokerage function’s response was largely ad-hoc and reactive. The projects delivered at this stage responded to short-term challenges/requirements identified by policy teams within their strategic goals. The brokerage function predominantly tried to establish momentum, creating several pockets of knowledge that attempted to demonstrate ‘proof of concept’ but were disconnected.

Stage 2: Programme-partnership

At Stage 2, Programme-partnership model is a structured framework designed to facilitate collaboration between researchers, policy-makers, businesses and funders. It recognizes the importance of careful programme structure, resource allocation, and a well-defined policy area. The model aims to generate evidence-based solutions to address strategic priorities while fostering a dynamic and ongoing relationship between research, policy, and business development.

Collaborative Knowledge Exchange and Facilitation

The participants referred to a knowledge brokerage mode that resembled a programme management structure with several embedded programmes running simultaneously to address a well-defined policy area or areas. The knowledge brokerage function ensured that these programmes would run collaboratively, and their work is jointly contributing towards the aims of the ecotone. The London Climate Change Partnership (LCCP) (The London Climate Change Partnership, 2023) is an example of this, as an independent partnership of key stakeholders across the academic, private and public sector (within the fields of environment, finance, health and social care, resilience, development, housing, government, utilities, communications, transport, retail, and academic research); bringing together expertise on climate change adaptation and resilience to extreme weather in London. The organizations have either a strategic or operational responsibility for dealing with climate change to enable knowledge transfer and brokerage, through the use of sharing knowledge and drawing on the network of organizations within the partnership.

In terms of having the power to convene, the brokerage function relied on a two-way relationship so that the policy area would benefit from research, but in addition, academics would learn from their policy partners about real-world issues and challenges. For example, in the £1m Transforming Construction Network Plus (TCNP) (UCL, 2021a), young researchers valued the proximity to leading policy stakeholders:

“…people valued the proximity to leading stakeholders. We effectively brought them to the academic community in a way that some of the younger colleagues could never have dreamed of getting. They had direct exposure to policymakers in the room with us. So, I think for me, most profoundly, it’s that bringing the policymakers into the room. Creating that space to bring people together was really important and valued.” I-7, Professor of Construction Management, Higher Education Institution.

As regards funding at this stage, the participants explained that ecotones with a brokerage maturity of this stage would have secured government funding. However, funding from multiple funders may create issues because if the ecotone engaged more with one funder over the other, this would generate an asymmetry, and therefore, the priorities of one funder may overshadow the priorities of the other funder. The participants mentioned another problem that arose from multiple funders, which was that the funders may had different approaches around a policy area, e.g., circular economy, so the approach had to be negotiated to ensure an outcome that was satisfactory for all actors:

“[Our funders] have different approaches on circular economy. So, [Funder 1] has a particular I think policy or strategy. [Funder 2] has something different as well. So clearly as a center you’ve got to understand and relate to all of them.” I-7, Professor of Construction Management, Higher Education Institution.

Resources, capabilities and practices

The participants argued that resource structuring to support the brokerage function takes up a significant proportion of the budget for professional services specialists to undertake administrative, events set, and communication activities. The brokerage function needed to budget for resources, meetings, and events at a higher proportion rate than expected for a standard research grant project. Regarding capability building, the brokerage function could build legitimacy and capabilities to overcome significant liabilities of newness that we saw in Stage 1. For example, the TCNP funded by the Industrial Challenge fund gave the network the legitimacy for capability building because it already had a place within the policy-making landscape. Policy-makers were already involved in the network and researchers who joined the network shortly after could be matched with their policy counterparts.

Regarding engagement practices, the participants mentioned that a brokerage function at Stage 2 would have the resources and budget to organize events and coordinate activities systematically. Speed dating networking events and roundtables were the most prominent engagement practices mentioned by the participants at this stage:

“So now we’re in the phase of setting up a speed dating workshop where both parties will come along and pitch the ideas about who wants to work together. And then the network will take it forward because they’ve got the money to do that.” I-13, Head of Engagement and Operations, Policy Institution.

Brokerage focus, response, and knowledge utilization

In Stage 2, the brokerage function’s focus was more strategic. Funders, the ecotone, and its partnerships would come together to serve a well-defined area. For example, the Alan Touring Institute focus was on data science and artificial intelligence, and the Manchester Urban Ageing Research Group had a strong local focus on challenges associated with population ageing in urban environments. The brokerage function’s response was proactive instead of reactive in Stage 2. The participants mentioned that knowledge partners contributed constantly rather than ad-hoc and reviewed and advised each other’s work. Finally, the knowledge base contributed towards a tightly defined policy area, such as the LCCP:

“…we realized that the impacts of climate change were not just about long-term mitigation and reducing carbon emissions, but it’s also about how do we deal with what is coming down the line in terms of the impacts of climate change. So that’s what we focus on is adaptation and very much long-term adaptation as opposed to short term resilience. We’re very much about how do we adapt London to the long term? Or how do we adapt London in the long term to the impacts of climate change that will happen over the next 20, 30, 100 years? I-43, Principal Policy and Projects Officer, Policy Institution.

Stage 3: Network of networks

Stage 3 was the final most-developed stage for the knowledge brokerage function to leverage the wider ecosystem landscape of multiple academic research-policy partnerships. The Network of Networks model was a dynamic and flexible framework that connected various networks, promoting collaboration, information sharing, and advocacy. It drew funding from various sources, including government support and subscription-based revenue, to sustain its activities. This model prioritized responsiveness to emerging challenges, co-production of solutions, and the diversification of evidence across multiple disciplines to address critical policy issues.

Collaborative Knowledge Exchange and Facilitation

The participants referred to a knowledge brokerage mode that resembled that of a hub-and-spoke model. The hub was the “umbrella” organization that oversaw and coordinated the brokerage efforts of the various networks, the “spokes”. The hub streamlined the network offering and aligned the network with the strategic priorities of the wider ecosystems landscape. On the other hand, the spokes were self-regulated and had their own structure. In terms of convening, the brokerage function had three main objectives. London Higher (LH) (London Higher, 2023) was a good example:

“[LH] convenes as a Collaborator—by hosting influential activities to identify new initiatives to solve common challenges—as a Communicator—by disseminating evidence of world-class research—and, as a Campaigner—by promoting advocacy strategies and raising awareness of policy implications across the ecosystem landscape.” London Higher website.

Regarding funding, the participants suggested that it would come from the government, but also the Hub could offer a subscription service whilst the spokes would access independent funding. For example, LH initially secured government funding which lasted three years and when that ended, it was able to alter its business model and offer a subscription service.

Resources, capabilities and engagement practices

Participants mentioned that resource structuring was intensive at this stage of maturity, the knowledge brokerage promoted collaborative working by mapping the resources of existing networks and promoting sharing of resources. Capability building focused on replicating and expanding good brokerage practices into other policy domains. The brokerage function’s capability building focused on strong connections between academics and policy-makers, but also would build strong connections between academics and users, charities, and charities and policy-makers. A research academic commented:

“it’s about a shared interest in developing the right policies and getting the right evidence to bear on policy problems so that there are different motivations from each of the different kind of interests there, it’s a kind of shared agenda.” I-21, Senior communications and public affairs Director, Policy Institution.

Regarding engagement practices, the knowledge brokerage offered, smart-matching services to connect ecosystem actors. Participants mentioned the National Centre for Universities and Business (NCUB) Konfer digital brokerage service (National Centre for Universities and Businesses, 2023) as a good example. Konfer was free for all UK businesses, charities, research and technology organizations, universities, academics and individuals. It enabled, e.g., users to find research partners from the wider ecosystem landscape of the ecotone. Another brokerage service was the development of Areas of Research Interest (ARIs) (Boaz and Oliver, 2023). Traditionally, the Research Councils set the strategic priorities for researchers, often quite different from those most important for policy-makers. ARIs detail the main research questions facing government departments at the local, national and international levels. They offered a more sophisticated dialogue with academia. ARIs allowed policy-makers to have “more skin in the game” and be interested in the research activities that take place. A policymaker explained:

“We do try to bring academics in to help us think through topics and issues. I try to encourage that among my policy colleagues to bring academics in at the earlier stages of policy development because I think that until you do that, you are not up to date with the latest thinking.” I-93, Associate Director, Policy Institution.

Brokerage focus, response, and knowledge utilization

At Stage 3, the knowledge brokerage focus was strategic and evolving. The knowledge brokerage response evolved into co-development. For example, the Climate Action Unit (CAU) at UCL (UCL, 2021b) had developed a series of training sessions to ensure the relationship between academics and policy teams did not fall into the client-contractor mode and instead focus on providing good support to the other community. One of the CAU members explained:

“But what we were really looking for was for partnerships where both the problem and the solution was jointly owned. So, everything that was being produced was being tampered with, an understanding of how the Councils would use it to deliver actual change.” I-77, CAU member, Higher Education Institution.

Finally, the knowledge base was rich and diverse. Unlike Stage 2 where multi-disciplinary evidence was generated towards a well-defined policy area, in Stage 3 the knowledge brokerage generated evidence that would feed into several policy domains from multi-disciplinary teams. LH provided a good example of where academic institutions/researchers have formed knowledge partnerships simultaneously with several London boroughs to address different aspects of the policy challenge to achieve London’s carbon-neutral goals, but in addition, LH and its partners were able to look at other issues such as equality, diversity, inclusion as a response to the Black Lives Matter protest, as well as mental health and well-being issues.

Discussion

In the realm of knowledge exchange and evidence use, knowledge brokering plays a crucial role in facilitating collaboration among stakeholders from different ecosystems (Pielke Jr, 2007; Oliver and Boaz, 2019). This diversity of evidence use is a strength but also necessitates greater collaboration. Researchers have shown increasing interest in the concept of ecotones, transitional areas where hybrid networks exchange knowledge between ecosystems (Seidman, 2009; Ghazinoory et al., 2021; Massa et al., 2022). In our study, we explored how these ecotones integrate various types of knowledge and investigated how the knowledge brokerage function within them evolves and matures over time.

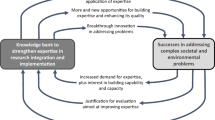

To answer our research question, we took an ecosystem perspective and used the exemplars of good practice and successful short-term, medium-term, and long-term academic–policy partnerships identified through our data collection and analysis to develop a three-stage ‘transitions framework’ to chart the trajectory of an ecotone’s knowledge brokerage function, outlining the different maturity stages from the initial groundwork state (Stage 1) to a Stage (2) where the knowledge brokerage service has a defined and structured programme, and the final aim of the most-developed Stage (3), leveraging and convening the wider landscape of multiple academic-policy partnerships.

The framework (Fig. 1) describes the three maturity stages of an ecotone’s knowledge brokerage function and their corresponding configurations across a wide set of organizational, and policy and brokering parameters.

In terms of validity, first, the framework takes a temporal bracketing process view (Langley, 1999), namely, it decomposes an ecotone’s knowledge brokerage function into three succinct maturity stages. This decomposition of data into successive adjacent maturity stages enables the examination of how the maturity of the knowledge brokerage function will lead to changes in the way ecotone actors facilitate brokerage operations from one stage to subsequent stages. Second, to put the temporal bracketing process into practice, we delved into the fields of organization design, and knowledge co-production and brokering literature. This exploration helped us identify specific observations to focus on and narrow down our coding process, as discussed by Locke et al. (2020), to unpack how each stage of the framework unfolds. As a final validation step, we conducted 13 expert review sessions, where experts from policy and academic institutions shared their positive assessments and offered constructive feedback.

Theoretical contributions

This study offers two theoretical contributions. First, it contributes towards an ecosystem approach to knowledge brokering. Globally, several attempts have been made to build communities and networks to improve research evidence use. However, most documented initiatives are rooted in confined disciplines (Boari and Riboldazzi, 2014; Molina-Morales et al., 2016) or organizations acting as boundary spanners (O’Mahony and Bechky, 2008). The nature of boundary organizations may limit their effective response to political or institutional barriers (MacKillop and Downe, 2023). Thus, recent studies call for an ecosystem approach that promotes greater collaboration and co-production, share, and use of evidence more efficiently (Seidman, 2009; Massa et al., 2022). Our research posits that this collaboration facilitated by a mature knowledge brokerage function is a gradual process and sheds light on three progressive stages of development.

Research in healthcare on evidence use offered insights into how an ecotone’s knowledge brokerage function operates (Fitzgerald and Harvey, 2015). This mode of brokerage function resembles our study’s Stage 2 maturity. However, the literature stops short in explaining how the brokerage function of an ecotone develops and matures. Thus by responding to calls for a longitudinal approach (Fitzgerald and Harvey, 2015), we were able to demonstrate the developmental stages that an ecotone may undergo to develop a mature knowledge brokerage function.

Our model is comparable to Best and Holmes’s (2010) three-generation model. Best and Holmes (2010) took a systems thinking approach to describe how systems thinking works through research-policy-practice: 1. Linear models; 2. Relationship models, and 3. Systems models. Although there are similarities between the two studies, we see them as complementary. Systems thinking is a valuable tool for understanding the complexity of larger systems, identifying potential unintended consequences, and designing policies and interventions that consider systemic dynamics. In some cases, a combination of both approaches, where systems thinking informs the understanding of the broader context and an ecotone approach facilitates stakeholder engagement and evidence use, maybe the most effective strategy.

Despite advocating for an ecosystem approach, we need to identify potential issues to minimize our own biases. First, the ecosystem approach presented in this article may impede certain academic fields because their discipline may not be directly associated with a policy issue. Second, certain academic institutions may be precluded because their reputation is not on par with the more prestigious universities or because, traditionally, they are not engaging in policy compared with their peers. Third, this coveted interdisciplinarity may result in some disciplines overpowering other disciplines when synthesizing evidence into a coherent whole (O’Mahony and Bechky, 2008). Fourth, we must not ignore the complex political policy-making context (Cairney, 2016). Finally, as brokering reaches greater maturity and size, it must also be able to navigate the increasing complexity and the political landscape surrounding it.

The second contribution is associated with the specific outputs of research and evidence systems. The field of evidence use has documented several diverse contributions from multiple theories, approaches, interventions, and initiatives (Halevy et al. 2019; Oliver and Cairney, 2019). However, these valuable advancements are contained within silos and are difficult to move beyond one-off projects that incrementally advance the knowledge base (Farley-Ripple et al., 2020). First, our findings confirm that a reduced connectedness—as demonstrated in Stage 1—due to limited collaboration efforts will inevitably contribute to a fragmented knowledge base. Simply put, the brokerage function in Stage 1 alone cannot increase the connectedness of research evidence. To overcome this limitation, research and policy ecosystems are vested in developing ecotones at the local or national level to help them move and advance the knowledge base. As evidenced in Stage 1, the brokerage function is only able to create ‘evidence pools’—an independent, isolated micro-data lake of research evidence, whereas, in Stage 2, research evidence forms a well-defined ‘evidence lake’—many evidence pools that belong to the same knowledge-base—and in Stage 3, the brokerage function can achieve cross-pollination of research evidence (Table 5).

For instance, unlike Stage 1, where the outputs of engagement were fragmented, in Stage 2, there was a vast amount of evidence produced by multi-disciplinary teams. Whereas in Stage 2, the policy focus was strategic, and the knowledge brokerage focus was predominantly on generating evidence on a well-defined policy area, in Stage 3, the knowledge brokerage would build emergent policy areas for the wider public interest.

Conclusion and future research

Our research question asked how ecotones’ knowledge brokerage function evolves to meet the needs of academic research and policy ecosystems. Our main contribution offers a three-stage transition framework that explains how the knowledge brokerage function evolves and matures in the boundaries of an ecotone. Ecotones focus on knowledge mobility within their adjacent ecosystems such as academic research and policy. It emphasizes the exchange of knowledge, collaboration, and boundary-spanning activities in these interface zones. The ecotone approach provides a specific strategy for fostering collaboration and knowledge exchange through its mature knowledge brokerage function.

Our study contributes to the field of knowledge exchange by identifying and describing the evolution of knowledge brokerage within ecotones. This advancement in theoretical understanding can guide future research in ecotone studies and help scholars and practitioners better comprehend how ecotones function and change over time. Recognizing the maturity stages of knowledge brokerage in ecotones has practical implications for various stakeholders, such as policymakers. Policymakers can use our findings to develop policies and interventions that are better aligned with the natural progression of knowledge brokerage in ecotones. This can lead to more effective policies and practices. Understanding these stages informs decision-making processes, as it provides insights into how knowledge should be brokered and utilized within ecotones to achieve desired outcomes. The identification of maturity stages promotes collaboration among different actors involved in ecotone management. When stakeholders understand the evolving nature of knowledge brokerage, they may be more willing to adapt their practices and collaborate effectively to achieve shared goals.

This research provides useful insight into the characteristics of the three possible stages of evolution but is limited in providing details on the specific milestones and timescales for each. Below we discuss some of the limitations and suggest future research directions. First, future research could provide valuable insights by delving into the specific timeframes associated with each stage of the transition and identifying the key factors that facilitate the shift from one stage to another. Exploring whether the commitment of specific individuals, the success of particular projects, or the presence of effective leadership played pivotal roles in these transitions would be particularly informative. Understanding these influencing factors in detail can offer essential lessons for the potential application of this model in various other contexts. Second, future research should consider the influence of various contextual factors, such as political and physical geography, the proximity of policy and research institutions, and the specific focus of the ecotone. These factors can vary significantly between regions and ecosystems, and exploring their impact can help us better understand the limitations and conditions for success when implementing similar models in different settings. Third, whilst our study’s unit of analysis was the ecotone, future research should include a deeper exploration of the individuals involved in knowledge brokerage, their roles, and how they operate. Activities, meetings, and project calls should be examined in relation to who manages them and how they contribute to the knowledge exchange process. Future research could highlight the significance of knowledge brokers within the ecotone. Linking these aspects to relevant literature, particularly research that highlights the role of leadership, can offer valuable insights into the success and dynamics of knowledge brokerage in ecotones.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the topic raised during the interviews.

References

Ayatollahi H, Zeraatkar K (2020) Factors influencing the success of knowledge management process in health care organisations: a literature review. Health Inf Libr J 37:98–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12285

Best A, Holmes B (2010) Systems thinking, knowledge and action: towards better models and methods. Evid Policy 6:145–159. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426410X502284

Boari C, Riboldazzi F (2014) How knowledge brokers emerge and evolve: the role of actors’ behaviour. Res Policy 43:683–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.01.007

Boaz A, Oliver K (2023) How well do the UK government’s ‘areas of research interest’ work as boundary objects to facilitate the use of research in policymaking? Policy Politics 51:314–333. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557321X16748269360624

Boswell J (2018) Keeping expertise in its place: understanding arm’s-length bodies as boundary organisations. Policy Politics 46:485–501. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557317X15052303355719

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cairney P (2016) The politics of evidence-based policy making. Springer

Cairney P, Kwiatkowski R (2017) How to communicate effectively with policymakers: combine insights from psychology and policy studies. Palgrave Commun 3(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0046-8

Cairney P, Oliver K (2017) Evidence-based policymaking is not like evidence-based medicine, so how far should you go to bridge the divide between evidence and policy? Health Res Policy Syst 15:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-017-0192-x

Cairney P, Oliver K (2020) How should academics engage in policymaking to achieve impact? Political Stud Rev 18:228–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929918807714

Cairney P, Oliver K, Wellstead A (2016) To bridge the divide between evidence and policy: reduce ambiguity as much as uncertainty. Public Adm Rev 76:399–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12555

Creswell JW, Poth C (2016) Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches, 4th edn. Sage Publications

Duncan R, Robson-Williams M, Edwards S (2020) A close examination of the role and needed expertise of brokers in bridging and building science policy boundaries in environmental decision making. Palgrave Commun 6:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0448-x

Farley-Ripple EN, Oliver K, Boaz A (2020) Mapping the community: use of research evidence in policy and practice. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00571-2

Fitzgerald L, Harvey G (2015) Translational networks in healthcare? Evidence on the design and initiation of organizational networks for knowledge mobilization. Soc Sci Med 138:192–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.06.015

Ghazinoory S, Phillips F, Afshari-Mofrad M, Bigdelou N (2021) Innovation lives in ecotones, not ecosystems. J Bus Res 135:572–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.06.067

Gluckman PD, Bardsley A, Kaiser M (2021) Brokerage at the science–policy interface: from conceptual framework to practical guidance. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8:84. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00756-3

Halevy N, Halali E, Zlatev JJ (2019) Brokerage and brokering: an integrative review and organizing framework for third party influence. Acad Manag Ann 13:215–239. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2017.0024

Heaton S, Siegel DS, Teece DJ (2019) Universities and innovation ecosystems: a dynamic capabilities perspective. Ind Corp Chang 28:921–939. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtz038

Hoffmann MG, Murad EP, Lemos DDC et al. (2022) Characteristics of innovation ecosystems’ governance: an integrative literature review. Int J Innov Manag 26:2250062. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919622500621

Kislov R, Wilson PM, Knowles S, Boaden R (2018) Learning from the emergence of NIHR Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs): a systematic review of evaluations. Implement Sci 13:111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0805-y

Langley A (1999) Strategies for theorizing from process data. Acad Manag Rev 24:691. https://doi.org/10.2307/259349

Leten B, Vanhaverbeke W, Roijakkers N et al. (2013) IP models to orchestrate innovation ecosystems: IMEC, a Public Research Institute in Nano-Electronics. Calif Manag Rev 55:51–64. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2013.55.4.51

Locke K, Feldman M, Golden-Biddle K (2020) Coding practices and iterativity: beyond templates for analyzing qualitative data. Organ Res Methods. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120948600

London Higher (2023) We are the voice of the higher education sector in London. https://londonhigher.ac.uk/. Accessed 21 Sept 2023

London Research & Policy Partnership (2023) Researchers and Policymakers working together for a better London for everyone. University of London. https://www.london.ac.uk/london-research-and-policy-partnership. Accessed 25 May 2023

MacKillop E, Connell A, Downe J, Durrant H (2023) Making sense of knowledge-brokering organisations: boundary organisations or policy entrepreneurs? Sci Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scad029

MacKillop E, Downe J (2023) Knowledge brokering organisations: a new way of governing evidence. Evid Policy 19:22–41. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426421X16445093010411

MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, Milstein B (1998) Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Field Methods 10:31–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X980100020301

Massa L, Ardito L, Petruzzelli AM (2022) Brokerage dynamics in technology transfer networks: a multi-case study. Technol Forecast Soc Change 183:121895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121895

Meyer M (2010) The rise of the knowledge broker. Sci Commun 32:118–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547009359797

Molina-Morales FX, Belso-Martinez JA, Mas-Verdú F (2016) Interactive effects of internal brokerage activities in clusters: the case of the Spanish Toy Valley. J Bus Res 69:1785–1790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.056

Moustakas C (1994) Phenomenological research methods. SAGE Publications

National Centre for Universities and Businesses (2023) Digital Brokerage—konfer. National Centre for Universities and Business. https://www.ncub.co.uk/solutions/digital-brokerage/. Accessed 21 Sept 2023

Oliver K, Boaz A (2019) Transforming evidence for policy and practice: creating space for new conversations. Palgrave Commun 5:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0266-1

Oliver K, Cairney P (2019) The dos and don’ts of influencing policy: a systematic review of advice to academics. Palgrave Commun 5:21. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0232-y

Oliver K, Hopkins A, Boaz A et al. (2022) What works to promote research-policy engagement? Evid Policy 18:691–713. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426421X16420918447616

O’Mahony S, Bechky BA (2008) Boundary organizations: enabling collaboration among unexpected allies. Adm Sci Q 53:422–459. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.53.3.422

Perkmann M, Schildt H (2015) Open data partnerships between firms and universities: the role of boundary organizations. Res Policy 44:1133–1143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.12.006

Pielke Jr RA (2007) The honest broker: making sense of science in policy and politics. Cambridge University Press

Provan KG, Kenis P (2007) Modes of network governance: structure, management, and effectiveness. J Public Adm Res Theory 18:229–252. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum015

Quintane E, Carnabuci G (2016) How do brokers broker? Tertius Gaudens, Tertius Iungens, and the temporality of structural holes. Organ Sci 27:1343–1360. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2016.1091

Seidman P (2009) Vitality at the edges: ecotones and boundaries in ecological and social systems. World Futur 1:31–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/194675670900100505

The London Climate Change Partnership (2023) Welcome to LCCP. London Climate Change Partnership. https://climatelondon.org/. Accessed 26 Sept 2023

Tushman ML, Scanlan TJ (1981) Boundary spanning individuals: their role in information transfer and their antecedents. AMJ 24:289–305. https://doi.org/10.5465/255842

UCL (2021a) Transforming construction network plus | The Bartlett School of Sustainable Construction. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/construction/about-us/transforming-construction-network-plus. Accessed 21 Sept 2023

UCL (2021b) Climate action unit. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/climate-action-unit/ucl-climate-action-unit. Accessed 21 Sept 2023

Viitanen J (2016) Profiling regional innovation ecosystems as functional collaborative systems: the case of Cambridge. Technol Innov Manag Rev 6:6–25

Williams P (2002) The competent boundary spanner. Public Adm 80:103–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00296

Zhao ZJ, Anand J (2013) Beyond boundary spanners: the ‘collective bridge’ as an efficient interunit structure for transferring collective knowledge. Strateg Manag J 34:1513–1530. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2080

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the interview participants for the valuable time which helped develop the ideas presented. We also extend our gratitude to the Greater London Authority for enabling this research and providing us with the resources to carry out the Fellowship. This report is independent research supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research ARC North Thames. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health and Care Research or the Department of Health and Social Care. This study was funded by the Capabilities in Academic Policy Engagement project, which is funded by the Research England Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IK: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft. SJ: Methodology, investigation, writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The UCL Research Ethics Committee has granted that this work was exempt from ethical approval as per UCL’s published guidelines. We confirm that all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations.

Informed consent

The UCL Research Ethics Committee has granted that this work was exempt from ethical approval as per UCL’s published guidelines. We confirm that all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krystallis, I., Jasim, S. Charting the path towards a long-term knowledge brokerage function: an ecosystems view. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 760 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02294-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02294-6