Abstract

The primary objective of this research is to examine the diverse product attributes related to the credibility of organic food. Given that organic quality of food products is considered a credence attribute, establishing credibility plays a pivotal role in consumers’ decision-making processes when purchasing organic products. The lack of credibility represents a significant barrier to the growth of the organic market. Therefore, it is crucial to explore the specific product attributes that can enhance the perceived credibility of organic products. To assess the various factors influencing credibility, a choice-based conjoint method was employed. The study involved Hungarian participants (n = 652) and Polish participants (n = 290), who were asked to select a hypothetical product they deemed more credible. The findings reveal that the country of origin, appearance, and packaging exert the most substantial influence on the perceived credibility of organic food. Additionally, price and the place of purchase were identified as factors that also impact consumer perceptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Consumer trust in the food chain is a significant issue in contemporary society. Given that food is an integral part of everyday life, consumers are increasingly concerned about the quality and safety of what they eat. While certain characteristics of food, such as smell, taste, and appearance, allow consumers to make immediate judgments about its quality, there are other attributes that often go unnoticed, such as the presence of pesticides or the production methods employed. This information asymmetry between consumers and producers contributes to organic food being considered a “credence good” (Giannakas, 2002), which is challenging to trust. Consequently, many consumers, particularly in emerging markets (Nuttavuthisit and Thøgersen, 2017), remain sceptical about the authenticity of organic products.

Trust and credibility are strongly related to each other. According to Bentele and Seidenglanz (2008), credibility is a sub-phenomenon of trust. In the context of food products, credibility can be a feature of a product attributed by consumers. As Thorsøe et al. (2016) explains, food producers or retailers must be credible to generate consumer trust.

The credibility of organic food in Hungary and Poland assumes even greater significance given the historical and social context of former socialist countries. As indicated by social psychology research, the legacy of socialist regimes has left a lasting impact on institutional trust in these nations, with trust in governmental and public institutions found to be notably low (Delhey and Newton, 2003). The erosion of trust in state institutions during the socialist era resulted in citizens relying on private and informal networks to address their daily needs due to limited resources and services (Delhey and Newton, 2003).

In the case of organic food, the credibility of certification systems and labelling practices becomes a vital factor in rebuilding and strengthening consumer trust in the agricultural sector (Hughner et al., 2007). As consumers in Hungary and Poland are more likely to be sceptical of official institutions, having robust and transparent organic certification processes can serve as a means to assuage concerns and increase the uptake of organic products (Bryła, 2016). By fostering credibility in organic food production, these countries can work towards mitigating the deep-seated distrust inherited from their socialist past and promote sustainable agricultural practices that align with consumer demands for trustworthy and ethical food choices (Nuttavuthisit and Thøgersen, 2017; Zander et al., 2015).

Various factors impede the growth of the organic food market. Hungarian and Polish researchers have identified the high price of organic food as a significant barrier (Szente, 2004; Bryła, 2016; Jarczok‐Guzy, 2018). While the health benefits associated with organic food are often acknowledged as a positive factor, low credibility in organic products poses an additional obstacle to market expansion (Nuttavuthisit and Thøgersen, 2017).

The most recent data of the Hungarian organic food market is from 2015, which valued it at €30 million, accounting for only 0.3% of the total food market, with per capita organic food consumption at €3/person/year (Willer et al., 2022). Although it can be assumed that these figures have increased since then, organic food consumption among Hungarian consumers remains relatively low.

In the case of Poland, data from 2019 indicates that the organic food market reached €314 million, representing 0.6% of the total food market. Annual per capita consumption was €8/person/year, which, although higher than the Hungarian average, still falls well below the averages of Western European countries. For instance, Austria has per capita consumption of €254/person/year, Germany has €180/person/year, and neighbouring Czech Republic consumes more than double that at €19/person/year (Willer et al., 2022).

Consumer’s perceived credibility in organic food is crucial, given the perception that organic products are better for the environment, more sustainable, and healthier than conventionally grown alternatives (Wee et al., 2014). However, maintaining credibility in the organic food industry presents challenges. The certification process for organic products is often costly and time-consuming, leading some farmers and traders to mislabel their products as “organic” without adhering to the necessary guidelines. This deceptive practice erodes consumer trust in the industry as a whole. Additionally, incidents of fraud and mislabelling within the organic food industry contribute to consumer scepticism and doubts regarding the authenticity of organic products (von Meyer-Höfer et al., 2015).

Aim of research and hypothesis building

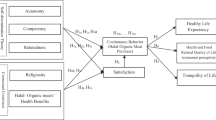

Credibility of organic food is influenced by various intrinsic and extrinsic factors. The aim of this research to quantify the effect of product-specific factors (e.g., packaging, price) and external factors (e.g., place of purchase), which might influence consumers’ perceived credibility of organic food. Attributes were selected based on Nagy et al.’s (2022) literature review findings, where the following attributes were found to be the most influential: packaging (Danner and Menapace, 2020), appearance (Nuttavuthisit and Thøgersen, 2017), communication (Vega-Zamora et al., 2019), certification and country of origin (Pedersen et al., 2018), price (Lee et al., 2020) and place of purchase (Bonn et al., 2016).

Among these attributes, certification holds the greatest prominence. Certification involves evaluating organic food supply chain actors to ensure compliance with organic standards and regulations, thus serving as a key factor in consumer trust (Janssen and Hamm, 2012). Organic logo generally signals certification to consumers, and well-known logos can create trust (Janssen and Hamm, 2012), although Činjarević et al. (2018) argue that the logo alone may not suffice to establish credibility in the product, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe.

Certification was assessed combined with the country of origin, as organic food is usually certified in the country its coming from (Pedersen et al., 2018). Numerous studies indicate that organic food originating from developing countries is perceived as less credible compared to products from Western countries (de Morais Watanabe et al., 2020; Bruschi et al., 2015; Yadav et al., 2019; Lang and Conroy, 2021; Chen et al., 2019). According to Yin et al. (2019), consumer ethnocentrism can influence organic food credibility based on the country of origin.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Consumers consider locally produced organic products more credible compared to imported organic products.

While limited evidence exists, product-level communication has the potential to enhance credibility in organic products (Vega-Zamora et al., 2019). Similarly, the appearance of organic food is believed to influence consumer perceptions. Lockie et al. (2002) demonstrated that processed organic food creates scepticism among consumers regarding its organic status. Communication of organic claims through packaging design, along with clear and accurate organic labelling, can increase consumers’ perceived credibility in organic food products (Margariti, 2021).

Packaging is a relatively underexplored topic in current literature (Hemmerling et al., 2015). Danner and Menapace (2020) found that consumers in German-speaking countries perceive plastic-packaged organic fruits and vegetables as less credible. Similarly, Hemmerling et al. (2015) argue that packaging, despite providing information about the organic status of the product, is often seen as environmentally unfriendly, contradicting the concept of organic food.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Environmental-friendly packaging and natural appearance of the product positively influence organic products’ perceived credibility.

The high price of organic food is a primary barrier to increased consumption (Hemmerling et al., 2015). However, low-priced organic products also generate distrust (Yin et al., 2016). Also, consumers’ willingness to pay for organic food is lower, if they do not consider it credible (Krystallis and Chryssohoidis, 2005). This contrast underscores the importance of measuring these credibility factors to understand which aspects are most significant to consumers.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Consumers consider lower priced organic products less credible than higher priced organic products.

Furthermore, the place of purchase plays a critical role in consumers’ assessment of organic food credibility (Konuk, 2018). Positive consumer perceptions of retailers are particularly influential (Bonn et al., 2016), while in the case of online retailers, the media richness of the website can impact the perceived credibility of organic products (Yue et al., 2017). Consumers can be sceptical of organic origin, if a product is sold in a superstore (Padel and Foster, 2005).

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Organic products’ perceived credibility will be lower if it is sold in a conventional supermarket.

The novelty of this study lies in its comprehensive examination of various external credibility factors and their impact on consumers’ perceived credibility. Previous research has highlighted the importance of trust in the organic food industry and identified several factors that contribute to consumer scepticism. However, this study delves deeper into the specific product attributes that influence credibility, such as certification, country of origin, product communication, appearance, price, place of purchase, and packaging. By exploring these factors and their relative importance, this research provides valuable insights into consumer perceptions of organic food credibility and offers guidance for organic food producers in enhancing consumer trust. Furthermore, the comparative analysis between Hungary and Poland sheds light on potential similarities and differences in the evaluation of organic food products within different cultural and market contexts.

Research question 1 (RQ1): Which factor is the most important to influence consumers’ credibility of organic food?

Research question 2 (RQ2): Are there differences between Hungarian and Polish consumers’ evaluation of organic food credibility?

Methods

To assess the various external credibility factors of organic food, an online questionnaire was developed using the choice-based conjoint method. This method involves conducting a consumer survey in which respondents are asked to rank “cards” containing different combinations of products based on their perceived importance. Through this analysis, the relative utility and importance of each attribute level can be determined in relation to the others (Green et al., 2001).

Survey design

The initial step in constructing the survey involved selecting the measured factors and their respective levels, based on Nagy et al.’s (2022) systematic review and bibliometric analysis and the set-up hypothesis in chapter 2. Figure 1 shows chosen attributes and their levels used in the research. Rice was selected as the focal product for this research, as the aforementioned factors are relevant to organic rice and it is a widely consumed cereal globally, ensuring familiarity among consumers.

The attribute levels were determined based on market observations. In the case of packaging, in addition to commonly used plastic and paper packaging, a packaging-free option was included to account for the growing trend of packaging-free retailing (Fuentes et al., 2019).

While white rice is the most commonly available type in retailers, brown rice has gained popularity as a more natural choice (Saleh et al., 2019). Therefore, in the questionnaire, the product presentation attribute was set to reflect this market observation. Furthermore, communication on organic status was based on the prevalent claim of “From controlled organic farming” found on many organic products.

The country-of-origin attribute consisted of three levels, representing the main rice exporters to the European Union (EC, 2022). In addition to the local product, rice from India and the United States were included in the choice experiment. To aid in distinguishing the origin, the organic logo of the respective country was partially incorporated.

To establish the price levels, market observations conducted in April 2021 were considered. The low price level was set at 999 HUF/12 PLN (approximately €2.50), the average price at 1399 HUF/17 PLN (approximately €3.5), and the high price at 2499 HUF/29 PLN (approximately €6) per kilogram.

Currently, organic food is readily available in most supermarkets and has become the primary sales channel for such products (Willer et al., 2022). Alongside supermarkets, online sales channels are increasing in number, while traditional channels like markets still hold significance for consumers when purchasing organic food (Hamzaoui-Essoussi et al., 2013).

Conjoint analysis

In the second step of the study, conjoint “cards” were generated using the R program, following the guidelines outlined by Aizaki and Nishimura (2008). Using the selected attributes and their respective levels, a full factorial design was created using the R package AlgDesign. Given the large number of attributes and levels involved in the survey, it was impractical to present all possible product variations to the participants. To address this, an orthogonal design was employed to reduce the number of choice sets to 16 pairs of cards in the questionnaire (for example, see Fig. 2).

A notable aspect of this research is the approach taken when querying the participants. Instead of asking about their willingness to purchase the products, they were specifically asked to indicate which product they trusted to be genuinely organic. This methodology allows us to ascertain the significance of the product attributes that influence the credibility of organic food. However, one limitation of this approach is that it does not enable us to determine willingness to pay, despite price being included as one of the attributes in the conjoint analysis.

According to random utility theory, perceived utility can be split into two components: systematic utility and a random component:

where U is the utility of the product, V is the observable component and e is the random factor.

Vi is the representative utility in the case of product i in the above showed equation. PACi, APPi, COMi, COOi, PRIi and POPi values represent the product attributes of product i (packaging, appearance, communication, country of origin, price, and place of purchase), β value is an unknown coefficient, which represents the unobservable factors.

Based on the above mentioned equation, conditional logit model was calculated in R, using clogit() function in the “survival” package (Lumley, 2006). To account for how individual characteristics impact the assessment of attributes, the model incorporates interactions between individual characteristics and attribute variables.

Within the questionnaire, in addition to selecting conjoint cards, Hungarian and Polish participants were also asked various questions relating to their organic food consumption habits. These included inquiries about the frequency of organic food consumption (Zander et al., 2015) and the participants’ familiarity with the organic logos presented in the questionnaire (Janssen and Hamm, 2012).

In addition to collecting demographic data, different scales were employed to measure participants’ attitudes towards specific food consumption habits. A 5-question scale developed by Brunsø et al. (2021) was utilized to gauge attitudes towards responsible food consumption. Respondents’ general willingness to pay for organic food was assessed using questions adapted from Wang et al. (2020). Given that the attribute of country of origin was investigated, participants’ ethnocentrism was also measured using a scale developed by Klein et al. (2006).

Data collection and sample

The online questionnaire was distributed to Hungarian respondents between 14 October and 7 December 2021 via social media platforms. For the Polish sample, the questionnaire was administered through the online platform Prolific from 20 to 22 June 2022. During these periods, a total of 723 Hungarian responses were collected, with 652 of them deemed analysable after excluding respondents who solely selected the option “I trust neither.” For the Polish sample, a total of 299 responses were obtained, and after analysis, 290 responses were included in the study. All participants were asked if they are responsible for food purchase in their household, thus respondents who are not directly engaged in food purchasing decisions were excluded from analysis.

There are notable differences between the two samples from Hungary and Poland. Table 1 illustrates that neither sample is representative of the overall population. The Hungarian sample is skewed towards female respondents, while the Polish sample is skewed towards male respondents. Additionally, the Polish sample over-represents younger participants. In terms of education, the Hungarian sample over-represents individuals with higher education, whereas the Polish sample is primarily composed of respondents with a secondary school education. However, similarities in terms of place of residence and income are observed between the Hungarian and Polish samples. Given the comparative nature of the research, data from 652 Hungarian respondents and 290 Polish respondents were separately analysed using the same methods.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 displays the food related consumer behaviour and attitude scales of the Hungarian and Polish samples. It can be observed that the pattern of the organic food buying frequency is very similar between the two samples. Approximately third of the respondents purchase organic food once or twice a month, Polish respondents slightly purchase more frequently organic food compared to the Hungarian participants. 14% of either Hungarian and Polish respondents almost never buy organic food, and approximately 10% of respondents can be considered as frequent organic food buyers.

Regarding organic logo knowledge, Hungarian respondents have a deeper awareness of either EU, USDA and India Organic logos compared to Polish respondents, although the same pattern can be observed: EU logo is the most well-known logo, and India Organic logo is the least known logo among the organic logos used in this research. Hungarian respondents scored higher points on both Food Responsibility, Price Sensitivity and Ethnocentrism scales as well.

Hungarian sample

Table 3 illustrates the findings regarding the influential factors among Hungarian respondents, with the country of origin emerging as the most significant factor, as supported by the corresponding organic logo displayed on the conjoint cards.

Domestic origin positively impacted the credibility of organic food (Exp coef = 1.975), and for rice, Indian origin was deemed more credible than rice from the United States (Exp coef = 0.859).

The type of packaging emerged as the second most important factor in determining consumers’ perceived credibility in organic rice. Paper packaging (Exp coef = 1.673) instilled confidence in respondents, while plastic packaging (Exp coef = 0.686) deterred them from trusting the organic authenticity of the food products. Packaging-free options were considered less credible compared to paper packaging.

Another less researched attribute that gained prominence was product appearance, which significantly influenced respondents’ perceived credibility in organic rice. Specifically, when the product appeared brown, respondents were more inclined to believe that it was genuinely produced in accordance with organic standards (Exp coef = 1.266).

Other characteristics also exerted a significant, albeit lesser, influence on the credibility of organic rice. The claim “from controlled organic farming” bolstered confidence in the organic nature of the rice (Exp coef = 1.181). The place of purchase was indicated by the background of the products in the questionnaire, with the organic market background appearing more credible from the respondents’ perspective (Exp coef = 1.161). Organic rice presented in an online store (Exp coef = 0.767) was considered less credible compared to rice with a supermarket background. Price had the least impact on the credibility of organic food, although it still carried significance. When the price of organic rice was lower than the average price, consumers harboured doubts about its organic origin. Conversely, a higher price enhanced the perceived reliability of the organic product (Exp coef = 1.113).

Polish sample

Table 4 displays that packaging, appearance and place of purchase were the most influential attribute for Polish respondents to consider a product as credible to be organic.

Packaging emerged as the most crucial factor for Polish respondents when evaluating the credibility of organic rice. Respondents from Poland considered paper packaging (Exp coef = 1.810) credible against plastic packaging (Exp coef = 0.355), similar to the Hungarian sample.

The appearance of the product also played a significant role. Polish respondents in line with Hungarian respondents perceived brown rice (Exp coef = 1.341) as more credible compared to white rice.

Place of purchase, while still significant, exerted a relatively lesser influence as the third most important attribute impacting the credibility of organic food for Polish respondents. Polish participants exhibited greater credibility in the organic market setting (Exp coef = 1.290), with online shopping (Exp coef = 0.705) appearing less credible than purchasing from a supermarket.

The country of origin demonstrated a significant but comparatively weaker impact on product credibility for Polish respondents. However, the order of attribute levels remained consistent between the two countries. In other words, rice of Hungarian origin was perceived as the most credible (Exp coef = 1.239), followed by rice from India and then the United States.

Price played a lesser role as an influencing factor for Polish respondents. Only the low price attained significance in influencing the credibility of organic rice (Exp coef = 0.726). However a low price had a negative effect on credibility just like in the case of Hungarian sample. Unlike the Hungarian respondents, high price did not yield a positive effect for Polish participants.

The communication on the product had no significant effect on Polish respondents. It was the least important attribute in the Hungarian sample but seemed to be completely indifferent to the Polish sample.

Effect of individual characteristics on credibility factors

In addition to examining the overall importance of each product attribute, we further investigated potential differences in credibility among different consumer groups. Specifically, we assessed variations based on gender, age, level of education, place of residency, perceived income, and frequency of organic food purchases. Additionally, we explored the impact of logo knowledge, consumers’ food responsibility, willingness to pay, and ethnocentrism. The statistically significant findings are summarized in Tables 5 and 6.

Among Hungarian male respondents, we observed a positive effect of paper packaging on credibility, albeit to a lesser extent compared to the average sample. Conversely, no significant difference was observed for Polish men.

Young Hungarian respondents appeared to be less influenced by high prices or the country of origin when determining credibility, but they exhibited higher perceived credibility in organic rice when the price was higher. Polish young respondents, on the other hand, demonstrated a greater influence of product appearance compared to the average sample.

Respondents with higher education assigned greater importance to the attributes that were also deemed significant by the average sample. Specifically, Hungarian respondents with higher education displayed a higher coefficient for country of origin, while Polish respondents with higher education exhibited a similar difference for packaging. Additionally, for Polish respondents with higher education, appearance and country of origin held greater importance compared to the average sample.

Regarding place of residence, no notable differences were observed in the importance of credibility factors. However, Polish respondents with high income displayed a more significant distinction.

Individuals with higher education, similar to those discussed earlier, placed greater importance on paper packaging and Hungarian origin when assessing the credibility of organic rice.

A distinction arises between Hungarian and Polish respondents based on the frequency of organic food purchases. Polish consumers who purchase organic food more frequently than the average demonstrated higher credibility in brown rice compared to white rice. In contrast, Hungarian regular organic food buyers placed greater perceived credibility in domestically sourced products and viewed the organic market as a reliable place of purchase.

Familiarity with logos also influenced consumers’ perceptions of product credibility. Hungarian and Polish consumers who were more familiar with the EU organic logo were more inclined to consider products bearing this logo as credible. For Polish respondents, knowledge of the EU organic logo was also positively associated with credibility in paper-packaged brown rice.

Among Polish respondents who were more familiar with the USDA logo, products featuring this logo were considered more credible than those with the Indian organic logo. These respondents also viewed brown rice as more credible. However, they exhibited less credibility in the organic market as a place of purchase compared to other respondents.

Conversely, Polish respondents who were more familiar with the Indian organic logo expressed greater perceived credibility in the organic market as a place of purchase and exhibited less credibility in products originating from the USA and Europe. Hungarian respondents who were more familiar with the Indian logo also displayed lower credibility in the EU organic logo, with product appearance assuming greater importance for them.

Polish respondents with a higher willingness to pay demonstrated distinct behaviour when evaluating the importance of specific credibility factors. They perceived brown rice in paper packaging as a more reliable product, and a higher price instilled greater confidence.

As expected, Hungarian respondents with higher levels of ethnocentrism exhibited greater credibility in Hungarian-origin organic rice compared to respondents with lower levels of ethnocentrism. In the Polish sample, however, we observed the opposite pattern. Rice bearing the EU organic logo but originating from Hungary garnered significantly less credibility among ethnocentric Polish respondents. Furthermore, the appearance of the product did not factor into their assessment of the credibility of organic rice. Nonetheless, these consumers displayed a stronger preference for paper-packaged products available at the organic market, considering them more credible from an organic standpoint. While the organic market background inspired confidence among Polish ethnocentric respondents, online sales evoked explicit distrust regarding the organic status of the product.

Discussion

The findings of this study corroborate previous research while also uncovering new relationships between factors influencing credibility in organic food. Overall, all the examined factors demonstrated an influence on consumers’ credibility in organic rice, although the differences between attribute levels were not consistently large, and not all results achieved statistical significance.

The significance of country of origin has been established in previous studies (e.g. Yip and Janssen, 2015; Lee et al., 2020; Thorsøe et al., 2016; Padel and Foster, 2005). However, in our research, this attribute was presented alongside logos. Our findings support prior research, such as Pedersen et al.’s (2018) assertion that the image and credibility of the exporting country can influence credibility in imported organic food. It is worth noting that knowledge of logos had a positive impact on credibility in products bearing those logos, similarly to the findings of Zander et al. (2015), highlighting the importance of education in improving consumers’ perceived credibility in organic food. We observed some differences in the perceived credibility among Hungarian and Polish consumers concerning the country-of-origin attribute, namely Hungarian consumers were more in favour of the Hungarian rice, on the other hand Polish participants considered it less trustworthy, though still more credible than imported organic rice. For both groups, products displayed with the EU organic logo were indicated as “Produced in Hungary” since rice production does not exist in Poland. Consequently, for Polish respondents, the product was not considered domestic. Overall, these findings can confirm Hypothesis 1.

Historically, there has been limited research on the packaging of organic food (Hemmerling et al., 2015). However, for both Hungarian and Polish respondents, the type of packaging emerged as a notably significant aspect, which corresponds with the findings of Danner and Menapace (2020), that packaging plays a crucial role for the products’ credibility for European consumers. We investigated packaging-free products, which are gaining popularity among environmentally conscious consumers (Rapp et al., 2017), and they appeared to be a preferable option compared to plastic packaging, although paper packaging garnered even greater credibility. One possible explanation is that the natural brown colour of the paper packaging in the questionnaire conveyed a sense of naturalness, aligning with consumers’ perception of organic products. This explanation is verified with the research of Marozzo et al. (2020), who tested natural colours’ consumer perceptions. According to their findings, ‘au naturel’ colours of packaging can increase willingness to pay and perceived authenticity in the case of healthy products. Additionally, paper packaging is considered a more sustainable choice, which holds considerable importance for organic food consumers (De Canio and Martinelli, 2021). While our current research did not directly address this aspect, the results suggest that product colour may also impact the credibility of organic products, as evidenced by Šola et al.’s (2022) finding that the colour of organic food packaging influences consumers’ decision-making processes.

The appearance of organic products has likewise received limited research attention, but our study demonstrates that product type does affect credibility, namely brown rice appears to be more credible to respondents compared to white rice, supporting Hypothesis 2. Consumption of brown rice is much lower compared to white rice, and consumers’ sensory preferences are biased towards white rice (Gondal et al., 2021). On the other hand, brown rice can be considered as a healthier option compared to white rice (Saleh et al., 2019). This “less tasty=healthy” intuition of consumers (Raghunathan et al., 2006) perfectly resonates with brown rice, thus the natural appearance of brown rice lends it an organic and authentic look, potentially enhancing its perceived credibility.

Price plays a paradoxical role in the perceived credibility of organic food products. Organic rice cost more to produce (Suwanmaneepong et al., 2020), making it a more expensive option for consumers, although consumers are price sensitive, especially in Hungary and in Poland (Ferencz et al., 2017). As Hughner et al. (2007) highlighted, consumers are looking for low prices, although low price can hinder the credibility of the product. Our results support this finding and Hypothesis 3, namely that low price creates scepticism among consumers, although high price was not a strong aid to build credibility of organic product.

The purchase environment of the organic product was influential both for Hungarian and Polish participants, which corresponds to previous studies, that consumers’ perception of the retailers has an impact on the organic products’ credibility which it sells (Bonn et al., 2016; Hwang and Chung, 2019; Konuk, 2018). The importance of online retail is rapidly growing in Central-Eastern Europe (Bartók et al., 2021), although our results show that consumers still do not consider products purchased online credible compared to traditional retail channels. As organic food become more mainstream, most of the purchase happens in supermarkets (Szente, 2004, Willer et al., 2022), but this does not reflect the level of credibility. Consumers considered organic farmers’ market as the most credible source of organic food in our research, especially among ethnocentric and regular organic food buyers. One explanation of this phenomena can be found in the research of Hamzaoui-Essoussi et al. (2013), that the size of farm influences the credibility of organic food produced by them. In organic farmers’ market usually only small farmers can sell their product, on the other hand, supermarkets mostly sell so called “industrial organic” products, which were produced by much larger farms, which are considered less trustworthy.

Regarding Research question 1, the results indicate that for organic products to build credibility, they should originate from the consumer’s own country, be packaged in natural-looking paper packaging, and be sold at a higher price. The order of importance may slightly differ for Polish consumers, but the aforementioned findings hold true for both groups.

Despite differences in demographic characteristics between the Hungarian and Polish samples, the results exhibited remarkable similarity, likely due to shared cultural and social backgrounds, providing answer to Research question 2. While there are variations in the food markets of the two countries, there are many similarities in consumer habits (Potori et al., 2014).

Limitations

It is important to note that certain demographic characteristics and consumption attitudes influenced the extent to which product attributes influenced credibility of organic food, although those demographic characteristics were not homogenous between the two samples, making it difficult to generalize results. Furthermore, when evaluating the conjoint cards, respondents made choices based on attribute combinations, with some attributes potentially impacting each other, while others may not be applicable to certain food types. Also, due to the nature of this research, only limited sets of attributes could be evaluated, thus other attributes might play a role influencing credibility. Regarding the country-of-origin attribute, the organic logo of the respective country was displayed on the packaging. Consumer familiarity with the logo varied, and more recognizable logos were deemed more credible. Due to the limitations of online data collection, there were limited opportunities to display different options for the place of purchase attribute. However, an explanation of the background’s meaning was provided at the beginning of the questionnaire.

While the study offers valuable insights into the perception of organic product credibility, its applicability to producers and marketers may be constrained because it did not directly investigate consumer buying behaviour, including the evaluation of a possible price premium for organic products. Regardless of the limitations, this study also paves the way for future studies. As the study solely focused on one type of staple product, it would be worthwhile to explore other food products where additional factors may contribute to strengthen credibility. Additionally, conducting research in a real-life setting, rather than presenting respondents with theoretical product combinations virtually, could yield different results. Although the theoretical products were designed to reflect real market situations, offline research may expose respondents to different stimuli.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study contributes to our understanding of the factors influencing consumers’ perceived credibility of organic food. From a theoretical perspective, these findings prompt the exploration of broader frameworks for understanding consumer decision-making in the context of organic products. Researchers in consumer psychology and marketing can build upon these insights to refine existing models and develop new ones that better capture the nuances of credibility assessment.

The findings confirm previous research while offering new insights into the role of packaging, product appearance, and country of origin. The results highlight the importance of natural-looking paper packaging and the positive impact of the appearance of brown rice on credibility. Moreover, the study emphasizes the significance of consumer knowledge of organic logos and the influence of place of origin on credibility. The similarities in results between Hungarian and Polish respondents, despite demographic differences, suggest shared consumer habits and cultural backgrounds. This study highlights the potential transferability of credibility factors across diverse cultural contexts, as evidenced by the similar responses of Hungarian and Polish participants. This observation opens possibilities for cross-cultural studies and encourages researchers to investigate how cultural factors interact with credibility perceptions in different regions.

However, further research is warranted to explore different food products and conduct studies in real-life settings. Overall, this research provides valuable information for organic food producers and marketers seeking to enhance consumers’ perceived credibility of their products. By addressing the credibility factors identified in this study, producers can improve their communication strategies and ultimately strengthen consumer trust in organic food.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Aizaki H, Nishimura K (2008) Design and analysis of choice experiments using R: a brief introduction. Agric Inf Res 17(2):86–94. https://doi.org/10.3173/air.17.86

Bartók O, Kozák V, Bauerová R (2021) Online grocery shopping: the customers’ perspective in the Czech Republic. Equilibrium 16(3):679–695. https://doi.org/10.24136/eq.2021.025

Bentele, G., & Seidenglanz, R. (2008). Trust and credibility—prerequisites for communication management. In: Public relations research: European and international perspectives and innovations. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden, p 49–62

Bonn MA, Cronin Jr JJ, Cho M (2016) Do environmental sustainable practices of organic wine suppliers affect consumers’ behavioral intentions? The moderating role of trust. Cornell Hosp Qly 57(1):21–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965515576567

Bruschi V, Shershneva K, Dolgopolova I, Canavari M, Teuber R (2015) Consumer perception of organic food in emerging markets: evidence from Saint Petersburg, Russia. Agribusiness 31(3):414–432. https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.21414

Brunsø K, Birch D, Memery J, Temesi Á, Lakner Z, Lang M, Grunert KG (2021) Core dimensions of food-related lifestyle: a new instrument for measuring food involvement, innovativeness and responsibility. Food Qual Prefer 91:104192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2021.104192

Bryła P (2016) Organic food consumption in Poland: motives and barriers. Appetite 105:737–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.07.012

Chen M, Wang Y, Yin S, Hu W, Han F (2019) Chinese consumer trust and preferences for organic labels from different regions: evidence from real choice experiment. Br Food J 121(7):1521–1535. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-02-2018-0128

Činjarević M, Agić E, Peštek A (2018) When consumers are in doubt, you better watch out! The moderating role of consumer skepticism and subjective knowledge in the context of organic food consumption. Zagreb Int Rev Econ Bus 21(SCI):1–14

Danner H, Menapace L (2020) Using online comments to explore consumer beliefs regarding organic food in German-speaking countries and the United States. Food Qual Prefer 83:103912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.103912

De Canio F, Martinelli E (2021) EU quality label vs organic food products: a multigroup structural equation modeling to assess consumers’ intention to buy in light of sustainable motives. Food Res Int 139:109846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109846

Delhey J, Newton K (2003) Who trusts?: the origins of social trust in seven societies. Eur Soc 5(2):93–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461669032000072256

de Morais Watanabe EA, Alfinito S, Curvelo ICG, Hamza KM (2020) Perceived value, trust and purchase intention of organic food: a study with Brazilian consumers. Br Food J 122(4):1070–1184. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-05-2019-0363

Ferencz Á, Deák Z, Nótari M (2017) Environmentally conscious consumption in Hungary. Ann Pol Assoc Agric Agribus Econ 19(4):34–39

Fuentes C, Enarsson P, Kristoffersson L (2019) Unpacking package free shopping: alternative retailing and the reinvention of the practice of shopping. J Retail Consum Serv 50:258–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.05.016

Green PE, Krieger AM, Wind Y (2001) Thirty years of conjoint analysis: reflections and prospects. Interfaces 31(3_supplement):S56–S73. https://doi.org/10.1287/inte.31.3s.56.9676

Giannakas K (2002) Information asymmetries and consumption decisions in organic food product markets. Can J Agric Econ 50(1):35–50

Gondal TA, Keast RS, Shellie RA, Jadhav SR, Gamlath S, Mohebbi M, Liem DG (2021) Consumer acceptance of brown and white rice varieties. Foods 10(8):1950. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10081950

Hamzaoui-Essoussi L, Sirieix L, Zahaf M (2013) Trust orientations in the organic food distribution channels: a comparative study of the Canadian and French markets. J Retail Consum Serv 20(3):292–301

Hemmerling S, Hamm U, Spiller A (2015) Consumption behaviour regarding organic food from a marketing perspective—a literature review. Org Agric 5(4):277–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13165-015-0109-3

Hughner RS, McDonagh P, Prothero A, Shultz CJ, Stanton J (2007) Who are organic food consumers? A compilation and review of why people purchase organic food. J Consum Behav Int Res Rev 6(2‐3):94–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.210

Hwang J, Chung JE (2019) What drives consumers to certain retailers for organic food purchase: the role of fit for consumers’ retail store preference. J Retail Consum Serv 47:293–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.12.005

Janssen M, Hamm U (2012) Product labelling in the market for organic food: consumer preferences and willingness-to-pay for different organic certification logos. Food Qual Prefer 25(1):9–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13165-015-0109-3

Jarczok‐Guzy M (2018) Obstacles to the development of the organic food market in Poland and the possible directions of growth. Food Sci Nutr 6(6):1462–1472. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.704

Klein JG, Ettenson R, Krishnan BC (2006) Extending the construct of consumer ethnocentrism: when foreign products are preferred. Int Mark Rev 23(No. 3):304–321. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330610670460

Konuk FA (2018) The role of store image, perceived quality, trust and perceived value in predicting consumers’ purchase intentions towards organic private label food. J Retail Consum Serv 43:304–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.04.011

Krystallis A, Chryssohoidis G (2005) Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic food: factors that affect it and variation per organic product type. Br Food J 107(5):320–343. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700510596901

Lang B, Conroy DM (2021) Are trust and consumption values important for buyers of organic food? A comparison of regular buyers, occasional buyers, and non-buyers. Appetite 161:105123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105123

Lee TH, Fu CJ, Chen YY (2020) Trust factors for organic foods: consumer buying behavior. Br Food J 122(2):414–431. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-03-2019-0195

Lockie S, Lyons K, Lawrence G, Mummery K (2002) Eating ‘green’: motivations behind organic food consumption in Australia. Sociol Ruralis 42(1):23–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9523.00200

Lumley T (2006) clogit. S original by T. Therneau, ported by T. Lumley: The survival package version 2.29

Margariti K (2021) “White” space and organic claims on food packaging: communicating sustainability values and affecting young adults’ attitudes and purchase intentions. Sustainability 13(19):11101. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131911101

Marozzo V, Raimondo MA, Miceli GN, Scopelliti I (2020) Effects of au naturel packaging colors on willingness to pay for healthy food. Psychol Mark 37(7):913–927. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21294

Nagy LB, Lakner Z, Temesi Á (2022) Is it really organic? Credibility factors of organic food–a systematic review and bibliometric analysis. PLoS ONE 17(4):e0266855. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266855

Nuttavuthisit K, Thøgersen J (2017) The importance of consumer trust for the emergence of a market for green products: the case of organic food. J Bus Eth 140(2):323–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2690-5

EU (2022) Organic farming in the EU, continuing on the path of growth, July 2022. European Commission, DG Agriculture and Rural Development, Brussels

Padel S, Foster C (2005) Exploring the gap between attitudes and behaviour: understanding why consumers buy or do not buy organic food. Br Food J 107(8):606–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700510611002

Pedersen S, Aschemann-Witzel J, Thøgersen J (2018) Consumers’ evaluation of imported organic food products: the role of geographical distance. Appetite 130:134–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.08.016

Potori N, Chmieliński P, Karwat-Woźniak B (2014). A comparison of the agro-food sectors in Poland and Hungary from a macro perspective. Research Institute of Agricultural Economics, p 9

Raghunathan R, Naylor RW, Hoyer WD (2006) The unhealthy= tasty intuition and its effects on taste inferences, enjoyment, and choice of food products. J Mark 70(4):170–184. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.70.4.170

Rapp A, Marino A, Simeoni R, Cena F (2017) An ethnographic study of packaging-free purchasing: designing an interactive system to support sustainable social practices. Behav Inf Technol 36(11):1193–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2017.1365170

Saleh AS, Wang P, Wang N, Yang L, Xiao Z (2019) Brown rice versus white rice: nutritional quality, potential health benefits, development of food products, and preservation technologies. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 18(4):1070–1096. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12449

Šola HM, Gajdoš Kljusurić J, Rončević I (2022) The impact of bio-label on the decision-making behavior. Front Sustainable Food Syst. 370. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.1002521

Suwanmaneepong S, Kerdsriserm C, Lepcha N, Cavite HJ, Llones CA (2020) Cost and return analysis of organic and conventional rice production in Chachoengsao Province, Thailand. Org Agric 10:369–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13165-020-00280-9

Szente V (2004) Organikus élelmiszerek fogyasztási és vásárlási szokásainak vizsgálata Magyarországon. Élelmiszer Táplálkozás Mark 1(1-2):101–105

Thorsøe MH, Christensen T, Povlsen KK (2016) “‘Organics’ are good, but we don’t know exactly what the term means!” Trust and Knowledge in Organic Consumption. Food Cult Soc 19(4):681–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2016.1243767

Vega-Zamora M, Torres-Ruiz FJ, Parras-Rosa M (2019) Towards sustainable consumption: keys to communication for improving trust in organic foods. J Clean Prod 216:511–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.129

von Meyer-Höfer M, Olea-Jaik E, Padilla-Bravo CA, Spiller A (2015) Mature and emerging organic markets: modelling consumer attitude and behaviour with partial least square approach. J Food Prod Mark 21(6):626–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2014.949971

Wang J, Pham TL, Dang VT (2020) Environmental consciousness and organic food purchase intention: a moderated mediation model of perceived food quality and price sensitivity. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(3):850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030850

Wee CS, Ariff MSBM, Zakuan N, Tajudin MNM, Ismail K, Ishak N (2014) Consumers perception, purchase intention and actual purchase behavior of organic food products. Rev Integr Bus Econ Res 3(2):378

Willer H, Trávnícek J, Meier C, Schlatter B (eds) (2022) The world of organic agriculture. Statistics & emerging trends 2022. Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) & IFOAM - Organic International

Yadav R, Singh PK, Srivastava A, Ahmad A (2019) Motivators and barriers to sustainable food consumption: qualitative inquiry about organic food consumers in a developing nation. Int J Nonprofit Voluntary Sector Mark 24(4):e1650. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1650

Yin S, Chen M, Chen Y, Xu Y, Zou Z, Wang Y (2016) Consumer trust in organic milk of different brands: the role of Chinese organic label. Br Food J 118(No. 7):1769–1782. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-11-2015-0449

Yin S, Han F, Wang Y, Hu W, Lv S (2019) Ethnocentrism, trust, and the willingness to pay of Chinese consumers for organic labels from different countries and certifiers. J Food Qual. 8173808. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8173808

Yip L, Janssen M (2015) How do consumers perceive organic food from different geographic origins? Evidence from Hong Kong and Shanghai. J Agric Rural Dev Tropics Subtropics 116(No. 1):71–84. (2015)

Yue L, Liu Y, Wei X (2017) Influence of online product presentation on consumers’ trust in organic food: a mediated moderation model. Br Food J 119(No. 12):2724–2739. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-09-2016-0421

Zander K, Padel S, Zanoli R (2015) EU organic logo and its perception by consumers. Br Food J 117(5):1506–1526. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-08-2014-0298

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Wacław Felczak Foundation for making Polish data collection possible.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by LBN, BU-P and ÁT. The first draft of the manuscript was written by LBN and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Interim Ethical Committee of the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Doctoral School of Economic and Regional Sciences (protocol code 103/2022, 7 April 2022).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. All participants accepted and voluntarily participated in the study after the researcher assured them of anonymity and that their responses were solely for academic purposes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagy, L.B., Unger-Plasek, B., Lakner, Z. et al. Confidence in organic food: a cross-country choice based conjoint analysis of credibility factors. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 762 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02293-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02293-7