Abstract

Achieving sustainability within planetary boundaries requires radical changes to production and consumption beyond technology- and efficiency-oriented solutions, especially in affluent countries. The literature on degrowth offers visions and policy paths with the explicit aim of ensuring human wellbeing within an economy with a lower resource metabolism. This paper reviews and discusses the academic literature on degrowth with the aim of deriving the main inherent challenges where further research is needed. Proponents of degrowth envisage radical redistribution and decommodification with ‘floors’ and ‘ceilings’ for income and wealth, as well as extensive public service provision. This paper outlines how results from other research support such a policy direction. However, the paper discusses three inherent challenges for such a future with respect to the feasibility and desirability of degrowth policies, as well as their legitimate underpinning in public support. This includes the internal growth dependencies of established social policies, which require changes to financing, output-based management and perhaps even curtailing input (service demand). Secondly, it concerns the role of public welfare provision when degrowth advocates also envisage the proliferation of alternative and informal economies. The paper emphasises that these two challenges invite more work on where public service provision should play a lesser role. Thirdly, the paper covers popular legitimacy. In affluent democracies, popular support needs to expand further beyond the ‘new left’ or the ‘green left’, even if larger shares of the population exhibit some potential for growth-critical stances. At the heart of these challenges is the need for new norms and values with respect to wellbeing, which is envisaged in the literature as a shift from materialist and hedonic towards needs-oriented and eudaimonic conceptions of wellbeing and happiness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Considering the planetary crises with respect to climate change, the mass extinction of species and the general degradation and depletion of the biosphere (see for instance IPCC, 2022; Jaureguiberry et al., 2022; Obura et al., 2022; Hagens, 2020; IPBES, 2019), it is no longer controversial to say that sustainability goes far beyond the implementation of new technologies and increased resource efficiency. More fundamental changes to both consumption and production are needed, especially in affluent economies. As a prominent example of more radical language, UN Secretary-General António Guterres has repeatedly delivered strong calls for action, stating at COP15 in Montreal in late 2022, “With our bottomless appetite for unchecked and unequal economic growth, humanity has become a weapon of mass extinction… ultimately, we are committing suicide by proxy” (United Nations, 2022).

By reviewing and discussing the academic literature on ‘degrowth’, the aim of this paper is to derive the main inherent challenges where further thinking and research are needed. These challenges or inherent tensions concern the feasibility and desirability of social policies based on degrowth. Arguments and empirical research support the need for greater equality and public decommodification, yet barriers or challenges may also be intensified in a political economy of degrowth. The main argument of the paper is that current and future research should focus on the potential limits for public decommodification or formal welfare provision. The paper substantiates these challenges by bringing in relevant literature and studies on the link between social policy, inequality and sustainability, as well as the dynamics of public attitude formation.

There has been a surge in literature and research on degrowth that explicitly seeks to address human wellbeing through a societal transformation towards sustainability. However, there are some inherent tensions with room for more critical discussion on the challenges of social policymaking in such a future (see Walker, Druckman & Jackson (2021) and Bailey (2015) with respect to fiscal viability and other growth dependencies of affluent welfare states).

Degrowth may be understood as a concept, research field, social movement or an ‘activist-led science’ that has for decades discussed what it would entail to place the pursuit of a reduction in throughput or resource ‘metabolism’ front and centre of a vision for the future, rather than as a supplement to the technology- and efficiency-oriented policies that dominate the established ‘green growth’ paradigm (Buch-Hansen & Nesterova, 2023; Schmelzer, Vetter & Vansintjan, 2022; Schulken et al., 2022; Hickel, 2021, 2020; Parrique, 2019; Kallis et al., 2018). Degrowth as a concept is strongly related to the notion of wellbeing economies guided by more diverse social aims rather than continued material growth, and both concepts depart from growth critiques (Fioramonti et al., (2022); Büchs & Koch 2019). Degrowth can perhaps be understood as a particular conception of the road towards a wellbeing economy, one that has a more explicit foundation in ecological economics, whereas the notion of a wellbeing economy with broader, multidimensional aims is more approachable for established actors in contemporary politics (Fioramonti et al., (2022)).

The paper aims to engage readers who are well-versed in the literature, as well as those less familiar with the topics covered. For the first group, the paper aims to condense the recent literature on degrowth and sustainability transformations and highlight the three challenges that particularly require further research and consideration. For the latter group of readers, the paper seeks to provide an up-to-date overview of the main policy ideas in the literature, as well as emphasising that the foundation in ecological economics must be taken more seriously by mainstream political science (i.e., addressing policy implications of the need to radically reduce the resource throughput of affluent economies). The paper establishes a definition of degrowth and traces its origins in a fusion of ecological economics and normative growth critiques rooted in critical theory, as well as the policies and visions offered by the literature. While greater equality and strong social policies are needed to achieve human wellbeing within planetary boundaries, this paper goes on to derive three inherent tensions or challenges with respect to the viability of such policies in a new political economy. These challenges follow from the growth dependencies of established welfare states.

The first challenge concerns strongly decommodifying and redistributive social policies, i.e., both ‘ceilings’ and ‘floors’ in terms of wealth and income, as well as an expansion of public services (McGann & Murphy, 2023; Fitzpatrick, Parrique & Cosme, 2022; Coote, 2022; Gough, 2022; Büchs, 2021; Koch, 2022c; Walker, Druckman & Jackson, 2021; Hirvilammi & Koch, 2020; Bohnenberger, 2020). The paper discusses how the research supports the need for such policy aims in order to achieve lower environmental impact and maintain wellbeing, but also that many social policies and the welfare state itself harbours substantial growth dependencies. Hitherto, welfare states have been complementary to the growth economy (Walker, Druckman & Jackson, 2021; Bailey, 2015).

The second challenge concerns the vision of simultaneous and complementary policy reforms ‘from above’ and transformations ‘from below’ of civil society and lifestyles based on ‘commoning’ and ‘convivialism’ (Buch-Hansen & Nesterova, 2023; Fitzpatrick, Parrique & Cosme, 2022; Koch, 2022a, 2022b; D’Alisa & Kallis, 2020; Parrique, 2019; Helfrich & Bollier, 2015; Deriu, 2015). These combinations of grand, progressive policy reforms and the proliferation of alternatives based on commoning (self-governing communities, cooperatives, ecovillages, etc.) are not mutually exclusive. However, they do raise some questions on the pertinence of state-led decommodification and welfare provision in a simultaneously expanding informal economy, where alternatives to formal state and market institutions are becoming more prominent in our lives.

The third and final challenge concerns public legitimacy and support. The social-movement-like transformations and major policy reforms envisaged by advocates of degrowth require broad public support. Across European countries, it is already possible to identify substantial shares of the population in support of growth critiques and degrowth-related policies (Schulken et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2022; Emilsson, 2022a, 2022b; Heggebø & Hvinden, 2022; Paulson & Büchs, 2022). This is remarkable considering that growth critiques and degrowth are marginalised in established political agendas and that advocates possess few conventional power resources (Buch-Hansen & Carstensen, 2021; Buch-Hansen, 2018). However, the paper also discusses ambivalence with respect to public support for an agenda that is still unclear or entirely unknown to many. Support for core policies must expand further beyond voter constituencies on the ‘new left’ or ‘green left’.

The three challenges or inherent tensions concern the feasibility and desirability of social policies based on degrowth. The first does so by focusing on such policies themselves, the second by discussing their role vis-à-vis informal commoning and reciprocity-based welfare within civil society, while the third concerns democratic legitimacy or public support. By focusing attention on these three issues, I emphasise that more research is needed on the potential limits for formal, publicly provided welfare in a political economy based on needs and sufficiency where informal commoning is also envisaged to play a larger role. In terms of popular support, I also emphasise that there are limits to degrowth in affluent economies if framed mainly as an issue of environmental justice and class struggle. New popular conceptions of welfare and wellbeing are also needed. This presupposes ‘social tipping points’, where new norms, behaviours and modes of living become more widespread in a rapid, non-linear fashion.

The literature itself has elaborated this as a shift from wants-based conceptions of wellbeing towards needs-based conceptions, with less room for conspicuous consumption (also discussed as ‘limitarianism’ and ‘sufficiency’), and a more eudaimonic rather than hedonic conception of happiness (Buch-Hansen & Nesterova, 2023; Isham et al., 2022; Jackson, 2021; Büchs & Koch, 2019; Spangenberg & Lorek, 2019).

Degrowth: Definition, origins and visions

It seems that we are witnessing a resurgent paradigm rift between the established ‘green growth’ paradigm and degrowth, while more ineffable and perhaps pragmatic concepts such as ‘a-growth’ or ‘post growth’ are often thrown into the mix as well (Jakob et al. 2020; Raworth, 2017; van den Bergh & Kallis, 2012). Degrowth does not mean replacing GDP growth with a political goal of indiscriminately destroying all forms of economic activity and imposing a self-inflicted recession, but a “… planned reduction of energy and resource throughput designed to bring the economy back into balance with the living world in a way that reduces inequality and improves human well-being” (Hickel, 2021:2). The main priority is not simply to reduce GDP by itself, but to move towards a situation where GDP becomes less important, thus facilitating a reduction in resource throughput. Various similar definitions place the emphasis on democratic and planned reductions of throughput—particularly in wealthy countries—with attention to redistribution and wellbeing on the basis of a growth-independent economy (Buch-Hansen & Nesterova, 2023; Schmelzer, Vetter & Vansintjan, 2022; Schulken et al., 2022; Hickel, 2020; Burkhart, Schmelzer & Treu, 2020; Parrique, 2019; Kallis et al., 2018; Jackson, 2016; Kallis, Demaria & D’Alisa, 2015; Demaria et al., 2013; Latouche, 2009).

It is no longer controversial to say that some forms of economic activity must be scaled down and that technological development and increased resource efficiency alone will not solve the problem. For instance, ideas of a ‘New Green Deal’ being floated in both the US and the EU tread the waters somewhere between green growth, degrowth and a-growth, depending on the specific proposal and emphasis (Albert, 2022; European Environment Agency, 2021; Mastini, Kallis & Hickel, 2021). Similarly, IPCC (2022) discussed demand-side reforms on the basis of socio-cultural and behavioural changes and suggested that these can be achieved while improving global wellbeing. Degrowth, however, is a more radical approach, where downscaling of environmentally harmful activities—both in terms of production (supply) and consumption (demand)—is the main path towards sustainability (Schmelzer, Vetter & Vansintjan, 2022; Schulken et al., 2022; Mont, Lehner & Dalhammar, 2022; Brand, 2022; Hickel, 2021, 2020).

Degrowth unifies two main strands of thought. Firstly, analyses of the environmental impact of the growth economy and secondly, normative critiques of ‘growthism’. In other words, what we might understand as a fusion of ecological economics and various critical approaches grounded in political theory. Degrowth unifies critiques of ecological destruction as well as inequality, alienation and ill-being as a result of the growth imperative, as well as feminism and post-colonial critiques of unequal terms of trade and resource extraction in the global economy (Schmelzer, Vetter & Vansintjan, 2022; Schulken et al., 2022; Hickel et al., 2022; Hubacek & Wieland, 2021; Hickel, Sullivan & Zoomkawala, 2021; Hickel, 2020; Parrique, 2019; Demaria et al., 2013, Alexander, 2012a).

The analytical foundation rooted in ecological economics finds support in studies of (the lack of) decoupling between exponential economic growth on the one hand and resource use and environmental impacts (global warming, biodiversity loss, etc.) on the other. This strand of research entered the public consciousness with Limits to Growth in 1972 (Meadows, Randers & Meadows, 2004). It is beyond the scope of this article to elaborate on contemporary research (for metareviews and relevant studies, see for instance Vogel & Hickel 2023; Fanning et al., 2021; Hubacek et al., 2021; Herrington, 2021; Lamb et al., 2021; Haberl et al., 2020; Hickel & Kallis, 2020; Vadén et al., 2020; Hagens, 2020; Parrique et al., 2019; Le Quéré et al., 2019; Ward et al., 2016; Wiedmann et al., 2015).

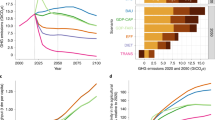

The main findings in this literature can be summarized like this: There is evidence of absolute decoupling between emissions and economic growth in a small number of rich countries, mostly due to an increased electricity supply from renewables (during a period of low growth), but it is very limited and starkly insufficient vis-à-vis goals in in the 2015 Paris Agreement (Vogel & Hickel 2023; Hubacek et. al. 2021). Beyond this, there is no wider, sustained and absolute decoupling from environmental impacts or resource use (in ‘footprints’, i.e., once trade has been taken into account) in national economies or the global economy as such (Herrington 2021; Vadén et al., 2020; Haberl et. al. 2020; Hickel & Kallis 2020; Parrique et al., 2019; Wiedmann et. al. 2015). Efforts based mainly on technology-driven efficiency gains are hampered by strong ‘rebound’ effects (Berner et al., 2022; Vadén et al., 2020; Parrique et al., 2019), and there are strong limits to the idea of a ‘circular economy’, since the vast majority of economic activities rely on new resource inputs (Bianchi & Cordella, 2023; Hickel & Kallis, 2020).

These findings make a strong argument for the aims advocated by degrowth. There are many recent examples of larger groups of ecosystem or sustainability scientists publishing collective reviews or calls to abandon our reliance on economic growth and directly reduce impactful forms of consumption/production (for instance Obura et al., 2022; Bradshaw et al., 2021; Pihl et al., 2021; Collste et al., 2021; Ripple et al., (2021); Wiedmann et al., 2020). The small number of surveys conducted to date among environmental scientists or experts find that clear majorities favour assessments in line with degrowth or a-growth, either explicitly or implicitly (King, Savin & Drews, 2023; Lehmann, Delbard & Lange, 2022).

The normative foundation of degrowth as a ‘movement’, on the other hand, is rooted in various strands of critical theory, and it tends to have strong ideological affinities with the ‘new left’ or left libertarianism. This is based on critiques of growthism as a hegemonic paradigm with impacts beyond the environment, and it embraces critiques of the negative social impact on wellbeing when economic growth is pursued at all costs (Parrique, 2019; Büchs & Koch, 2019; Kallis et al., 2018).

Beneath these lines of thought, degrowth presupposes a shift away from wellbeing based on materialistic and hedonic values, framed within the literature as critiques of the ‘hedonic treadmill’, materialism, consumerism, conspicuous consumption or self-centeredness (Hirvilammi et al., 2023; Isham et al., 2022; Jackson, 2021; Büchs & Koch, 2019). This perspective finds support in analyses of how consumption-driven pursuits of wellbeing provide no further positive (or even negative) effects on happiness and wellbeing in affluent economies (Isham et al., 2022; Collste et al., 2021).

Conversely, degrowth relies on a needs-based (as opposed to a wants-based) conception of wellbeing, as well as related concepts like ‘limitarianism’ or ‘sufficiency’ (Hirvilammi et al., 2023; Buch-Hansen & Nesterova, 2023; Koch, 2022c; Büchs, 2021; Bohnenberger, 2020; Büchs & Koch, 2019). It also presupposes a popular or cultural shift from hedonic to eudaimonic conceptions of wellbeing (Isham et al., 2022; Jackson, 2021; Büchs, 2021; Büchs & Koch, 2019; Lamb & Steinberger, 2017). Eudaimonia is the classic Aristotelian idea of living in accordance with personal values and fulfilling one’s potential as a virtuous (social) citizen, whereas hedonism concerns the simpler and more immediate maximisation of pleasure. This distinction has been widely used in psychological research on wellbeing and happiness (Ryff, 2017, 1989).

The literature on how public welfare provision can reduce hedonistic, positional or status-driven consumption often makes references to needs-based conceptions of welfare and wellbeing, as elaborated by Max-Neef (1991) and Doyal & Gough (1991). Needs-satisfiers and objective aspects of wellbeing can be defined in terms of nutrition, housing, healthcare, security, etc. The same concerns and ideas are reflected in the emerging literature on ‘foundational economics’, in which certain needs are decommodified and prioritised for public or collective provision (if not always publicly financed) (Novy, 2022; Wahlund & Hansen, 2022).

These origins of degrowth have led to various political aims in terms of democracy, international politics, labour and working conditions. This paper focuses on issues related to promoting redistribution and needs provision in a political economy of degrowth.

Public decommodification: Enabling degrowth or growth dependency?

This section discusses the basic challenge of expanding decommodifying social policies when the contemporary welfare state has nourished its own growth dependencies. The degrowth literature commonly envisages an expansion of public welfare services, transfers and progressive taxes. Such social policies must also become growth independent.

The specific social or welfare policy proposals propagated and discussed by the literature include caps or ceilings on maximum income and wealth, as well as minimum income or basic income and extensive provision of public services across a broader range of needs than would typically be covered by contemporary welfare states (see McGann & Murphy, 2023; Coote, 2022, Gough, 2022; Büchs, 2021; Koch, 2022c; Walker, Druckman & Jackson, 2021; Bohnenberger, 2020; Hartley, van den Bergh & Kallis, 2020; Hirvilammi, 2020; Hirvilammi & Koch, 2020). For Daly (2007), politically chosen maximum and minimum income levels were a logical implication in a realised steady-state economy. Altogether, this amounts to radical, policy-led decommodification.

In this section, we will primarily discuss policies concerning welfare provision and redistribution, but the extensive reviews by Fitzpatrick, Parrique & Cosme (2022), Parrique (2019) and Cosme, Santos & O’Neill (2017) identify a number of other core policy proposals in the literature. These include a reduction in working hours, job guarantees, caps on resource use and emissions, not-for-profit cooperatives, deliberative forums, ‘reclaiming’ the public commons, ecovillages and housing cooperatives, which we will return to in the next section.

The overall policy direction is neatly encapsulated by discussions on universal basic income (UBI) and universal basic services (UBS) and how they can be combined or supplement each other in a degrowth economy (Coote, 2022; Büchs, 2021; McGann & Murphy, 2023). Bohnenberger (2020) distinguishes vouchers for various goods or services as a distinct policy option in between UBI and UBS. Universal basic income has a centuries-long history in political thought outside of degrowth (Ketterer, 2021; Standing, 2017), but has accompanied the ecosocialist origins of degrowth since the 1970s (Gorz, 1994). The concept of UBS embodies more recent ideas of how to ensure strong welfare services.

Both UBI and UBS can be discussed alongside their different environmental and social advantages. While UBI affects individual consumption, UBS concerns the production side of the economy and relies on the political identification of needs that are provided and financed (partly) by the public (Büchs, 2021). Furthermore, UBI is rooted in normative ideals concerned with emancipation and autonomy (Ketterer, 2021), whereas UBS perhaps speaks more directly to the needs-oriented conception of wellbeing with lower resource footprints, as outlined above (Büchs, 2021; Bohnenberger, 2020). Universal basic services directly seeks to elaborate how relatively universal and satiable (but also non-substitutable) needs can be translated to policy fields such as housing, health, education, transport and nutrition, etc. (Bohnenberger, 2020; Büchs & Koch, 2019; Lamb & Steinberger, 2017). It does not necessarily imply fully publicly financed and delivered services in areas where welfare states do not do so today (Coote, 2022; Bohnenberger, 2020). This approach is elaborated further in the literature on ‘foundational economics’, where social licensing entails that some services or public infrastructures are not necessarily financed or even delivered by public entities. Instead, private companies enter into formal, reciprocal obligations to meet certain standards or otherwise offer social returns to the local areas in which they are based (Novy, 2022; Wahlund & Hansen, 2022).

There is research to support that equality and decommodified service provision make it easier to reduce resource use. More equal economies and countries with better public service provision exhibit weaker links between resource use and various indicators of needs and wellbeing (Vogel et al., 2021). A higher level of inequality means that more energy is needed to ensure a decent standard of living for a broader share of the population (Millward-Hopkins, 2022). These studies run parallel to widely disseminated analyses of how ‘carbon inequality’ mirrors economic inequality, or how emissions are disproportionately driven by the richest individuals across and within countries (Chancel et al., 2023, Gore, 2021). Previous studies into healthcare provision have highlighted that public procurement and provision may be substantially more resource efficient than private solutions for the same services (Bailey, 2015).

In short, it is possible to achieve security and wellbeing at lower levels of resource use, although equality and wellbeing in rich economies presently emerges as equality of unsustainably high levels of consumption (Garcia-Garcia, Buendia & Carpintero, 2022; Ottelin, Heinonen & Junnila, 2018; Fritz & Koch, 2016). In addition to the impact on resource use, research has sought to explain the negative links between inequality and psychosocial aspects of wellbeing, such as happiness and social trust. However, consensus has not yet been reached on the independent effects of economic inequality versus other drivers of status inequality, social distance and the perceived fairness of market and state institutions (Willis et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2022; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2017).

Since contemporary welfare states vary widely with respect to coverage or generosity and the institutional roles of public policies vis-à-vis market, family and civil society, efforts have been made to investigate potential links between ‘welfare regimes’ and environmental sustainability (see the seminal typology and conceptualisations popularised by Esping-Andersen (1990) or Hasanaj (2022) for a recent overview, including the topic of global regime variations beyond Western welfare states). Arguments have been elaborated for a ‘synergy’ hypothesis linking universal/social democratic welfare states, coordinated economies and environmental sustainability (Garcia-Garcia, Buendia & Carpintero, 2022; Schoyen, Hvinden & Leiren, 2022; Koch & Fritz, 2014; Dryzek, 2008). Universal welfare states and/or coordinated market economies might arguably have stronger foundations for integrating strong environmental policies focused on the long-term with their existing state capacities as well as coordinated governance structures incorporating different interests (Finnegan, 2022; Lamb & Minx, 2020). Dryzek (2008) also argues that discourse on sustainability has been more prevalent here, and that such economies are already based on the idea that private and public interests need not be at odds with each other.

Coordinated economies with strong state capacities and transparent institutions do indeed seem to fare better in terms of adopting stronger climate policies (Finnegan, 2022; Lamb & Minx, 2020; Zimmermann & Graziano, 2020; Best & Zhang, 2020). In terms of public attitudes, citizens in more encompassing and universal welfare states express stronger support for more extensive environmental policies (Sivonen & Kukkonen, 2021; Fritz & Koch, 2019). More egalitarian societies seem to fare better in terms of avoiding public divides with opposition towards environmental policies, an important mechanism perhaps being that redistributive institutions dismantle the perception that there are trade-offs between environmental and social concerns (Gaikwad, Genovese & Tingley, 2022; Parth & Vlandas, 2022; Heggebø & Hvinden, 2022; Malerba, 2022; Dechezleprêtre et al., 2022; Otto & Gugushvili, 2020; Fritz & Koch, 2019). Favourable public moods are mirrored in the politics of established mainstream parties in the sense that environmental agendas go beyond the parties on the green left in universal welfare states (Derndorfer, Hoffmann & Theine, 2022).

However, resource and impact-oriented indicators of sustainability, such as material footprints or consumption-based emissions per capita, do not readily fall into established institutional ‘regime’ patterns (Garcia-Garcia, Buendia & Carpintero, 2022; Koch, 2022c; Fritz & Koch, 2019; Koch & Fritz, 2014). These are the primary concerns from a degrowth perspective, where current effects of income and affluence still trump everything else. While the afore-mentioned nuances are important, there is still a strong negative relationship between the fulfilment of material needs and social outcomes on the one hand, and indicators of environmental sustainability on the other (Fanning et al., 2021; Fritz & Koch, 2016). To date, this link has not been sufficiently broken anywhere.

Finally, we cannot ignore that the modern welfare state evolved in tandem with the growth economy, or as a ‘double movement’ complementary to capitalism, as Polanyi (1944) described it (Novy, 2022; Walker, Druckman & Jackson, 2021; Walker & Jackson, 2021). This means that the welfare state itself is afflicted by a number of growth dependencies. Walker, Druckman & Jackson (2021) and Walker & Jackson (2021) have discussed these dependencies under the headings of financing, increasing relative costs of care, increasing demands, rent seeking, ownership models and management models incentivising growth. The welfare state is financed by taxation and contributions from economic activities, the aggregate value of which could be expected to decline in a degrowth scenario, particularly in wealthy economies (see Bailey (2015), who elaborates on the challenge with respect to financing welfare beyond growth).

Costs, in particular for care services such as healthcare, have increased at a faster rate than GDP in many countries, and relative differences in productivity improvements, as described by Baumol’s cost disease, might have contributed to the increasing relative costs of some services in the public sector. In addition, demands have changed (and increased) due to changing demographics, family structures and new socioeconomic risks associated with modern labour markets. Finally, many management models have relied on incentivising and rewarding increasing activity and output within the public sector. Some of these growth dependencies could be curtailed, for instance by switching to less growth-dependent sources of financing (such as shifting away from contributions) and towards more progressive and environmental forms of taxation, abandoning output-oriented management, curtailing opportunities for rent-seeking and limiting for-profit ownership models, etc. (Walker, Druckman & Jackson, 2021; Walker & Jackson, 2021; Bailey, 2015).

In summary, there are arguments and research to support the view that strong welfare institutions are needed in an economy where wellbeing is achieved at lower levels of resource use and impact. Many of the arguments and findings presented above are sometimes raised in other fields of literature without explicit or elaborated references to degrowth, such as the nascent literature on ‘eco-social’ welfare states (Hirvilammi et al., 2023; Schoyen, Hvinden & Leiren, 2022; Gough, 2022). However, we cannot identify any contemporary welfare states that have succeeded in breaking the current links between affluence, wellbeing and environmental degradation. Established welfare states are still concerned with ideas and paradigms wedded to the growth economy (Hirvilammi et al., 2023; Hirvilammi, 2020). There are also real growth dependencies within contemporary welfare states, and even if they could be curtailed to some extent, it should be discussed whether there would need to be a reduction in some current demands for publicly provided welfare.

Commoning and convivialism: doing away with the welfare state?

This strand of degrowth does not concern state-led decommodification and welfare provision, but emancipation from both state and market. It outlines needs, sufficiency and commoning provided outside of formal institutions (Schmelzer, Vetter & Vansintjan, 2022). It often imagines self-determination or governance at community level. Following on from the challenge raised in the previous section, this topic provides an avenue for further thinking on decommodification and growth independence outside of the formal welfare state. Yet it also raises its own challenge concerning the balance (both potential complementarities and trade-offs) between public social policies and the alternative or informal economy.

The terms ‘commoning’ and ‘convivialism’ are often points of departure in this literature. Convivialism (from the Latin ‘convivere’, meaning to live together), like ‘décroissance’ (degrowth), originates in French debates (Deriu, 2015). Commoning denotes the shared and network-based management of material and social resources, or community-based ‘governance’ (Koch, 2022c; D’Alisa & Kallis, 2020; Parrique, 2019; Helfrich & Bollier, 2015; Deriu, 2015).

While decommodification is about the public stepping in and financing and/or providing resources or goods that have been commodified and regulated by the price mechanism, commoning represents a different process. Commoning describes the social practices, values and norms used to manage public or common resources. The concept is known from the management (and mismanagement) of resources that can be characterised as common-pool resources, as described by Hardin (1968) in The Tragedy of the Commons and by Ostrom (1990) in her seminal work on functioning, sustainable commons. Commons are guided by the organising principle of reciprocity, whereas states and markets adhere to exchange and redistribution (Parrique, 2019; Helfrich & Bollier, 2015).

This is a strand of degrowth that broadly envisages radical change and emancipation ‘from below’ rather than through ‘top-down’ policy reforms (Schulken et al., 2022; Kallis et al., 2018; Demaria et al., 2013). It broadly covers many of the proposals reviewed by Fitzpatrick, Parrique & Cosme (2022), Parrique (2019) and Cosme, Santos & O’Neill (2017) that were not covered in the previous section, such as not-for-profit cooperatives, deliberative forums, ecovillages and housing cooperatives. It could also be said that this concerns all kinds of alternative and informal economies based on solidarity, reciprocity and mutual exchange, as well as non-profit forms of production in cooperatives, ecovillages or transition towns (Schmelzer, Vetter & Vansintjan, 2022; Kallis et al., 2018). These solutions are seen as a way to reduce the need for increasing production and consumption. Commoning versus decommodification mirrors the potential tensions between grand, public social reforms and bottom-up, community-based management.

Transformation of paid labour, especially a general reduction in working hours, underpins commoning or convivialism as a core policy proposal, also straddling the previous institutionalist, policy-oriented strand (Kallis et al., 2018; Cosme, Santos & O’Neill, 2017). Shorter work days or work weeks facilitate commoning by freeing up time as a necessary resource. In addition, it further reduces material consumption and encourages more sustainable and social pursuits that require free time (Chung 2022; Antal et al., 2020; Parrique, 2019; Kallis et al., 2018; Pullinger, 2014). Reducing working hours can also be seen as a tool for weakening ‘Okuns Law’, the strong association that is typically observed between low economic growth and increasing unemployment, although it is likely that a general reduction in working time would need to be accompanied by policies that lower profit rates (Oberholzer, 2023; Antal, 2014). These aims are followed by proposals to increase public sector service employment (hence, the aforementioned discussion on UBS) and even ‘job guarantees’ for the unemployed (Parrique, 2019; Kallis et al., 2018; Cosme, Santos & O’Neill, 2017).

The most radical visions in this strand of degrowth literature have an origin in anarchism in the form of self-reliant and self-determinant communities, or imagining a civil society nearly absent of state and market. For instance, Trainer (2010) argues that the implications of a degrowth, steady-state economy can only logically mean living in communities absent of growth-oriented markets and financial institutions and with relatively minimal state institutions (Alexander, 2012b). It is not clear in such writings that there would or should be room for the ambitious proposals for universal, publicly provided basic services.

This approach to degrowth has also been criticised within the literature as being utopian and overly romantic with respect to a simpler, self-sufficient way of life (Schmelzer, Vetter & Vansintjan, 2022). Outright anarchism is not dominant in the literature (see also Koch, 2022a, 2022b on state-civil society relations in degrowth). However, this strand of degrowth does envisage a substantial expansion of the alternative and informal economy, and this raises some questions with respect to the role and viability of formal social policies.

The predominant idea in the literature is that degrowth is realised by complementarities between top-down policy reforms and the spread of bottom-up alternatives. The lack of more conceptual, theoretical or strategic clarity beyond this vague idea has been elaborated and addressed in recent work on state-civil society relations and transformational strategies, the latter inspired by the work of Erik Olin Wright (Schmelzer, Vetter & Vansintjan, 2022; Chertkovskaya, 2022; Koch, 2022a, 2022b; D’Alisa & Kallis, 2020; Wright, 2019). Wright conceptualised three types of transformational change, with ‘interstitial’ strategies including the proliferation of alternatives within capitalism. While initially marginal, successful alternative institutions can proliferate and cumulatively bring about a demand for more transformative and hegemonic change.

This constitutes a natural interstitial path towards degrowth, whereas the social-policy-led transformations of the previous section might represent what Wright labelled ‘symbiotic’ strategies of change. This broadly means making use of the state and existing institutions and reforming them through more traditional political processes. Both logics may provide positive feedback for each other. Finally, ‘ruptural’ strategies describe confrontational and even revolutionary political acts through which movements seek to dismantle or abolish existing power structures and institutions. Such actions are not widely discussed in the degrowth literature, but they may include more traditional actions such as civil disobedience and mass protests.

Popular support: dreary limits or a new wellbeing economy?

While the first two sections concerned different challenges with respect to the potential limits of formal social policies and their role vis-à-vis an economy based on commoning and convivialism, this final section raises the challenge of gathering public support. If degrowth aims to transform societies through both the interstitial and symbiotic strategies outlined above, it must expand its support base beyond smaller activist groups and academic environments. Public support greatly increases the likelihood that policy ideas will survive the policy process (Schaffer et al., (2022); Burstein, 2003).

This is certainly a challenge considering that the established growth paradigm constitutes the political order. For instance, Buch-Hansen & Carstensen (2021) conceptualise degrowth as a ‘fourth-order change’ beyond more familiar third-order paradigms operating within the growth economy, and this renders it antagonistic to most predominant elites, including epistemic communities (beyond the sustainability sciences), established policymakers and especially economic interests. With few power resources in this respect, degrowth advocates often envisage change via social movements and eventually broader public support (Schulken et al., 2022; Rilovic et al., (2022); Buch-Hansen & Carstensen, 2021; Buch-Hansen, 2018).

There is substantial evidence that environmental politics is more likely to be successful when redistributive concerns are taken into account, and more likely to fail if for instance reforms of taxes and levies have regressive effects, alongside other important determinants of support such as environmental values, political trust and perceived policy efficiency (Gaikwad, Genovese & Tingley, 2022; Bergquist et al., 2022; Bumann, 2021; Drews & van den Bergh, 2016a). Some of the literature has discussed whether support for environmental policies and support for social policies complement each other or rather crowd each other out, and it is possible to identify a complex mosaic of high to low support for both policy fields (Emilsson, 2022a, 2022b, Heggebø & Hvinden, 2022; Otto & Gugushvili, 2020). This indicates a need for policy agendas that seek to avoid trade-offs in these policy fields in order to unite coalitions and achieve broader support. As previously mentioned, there is some support for a ‘synergy’ logic at a national level, where more encompassing or universal welfare states are reflected to a larger extent in better support for both policy fields (Heggebø & Hvinden, 2022; Sivonen & Kukkonen, 2021; Fritz & Koch, 2019).

Environmentalism or environmental values constitutes an independent set of values (conceptualised in different studies as ‘biospheric’, ‘new ecological paradigm’, ‘self-transcendence’ or the broader set of ‘postmaterialist’ values, see for instance Smith & Hempel, 2022; Bouman et al., 2018, Dietz et al., 2005 for more). However, there is still a tendency for environmentalism to be associated with left-wing ideology, especially when we move from broad attitudes and values to attitudes to specific policy tools with material and distributional consequences (Kenny & Langsæther, 2022; Smith & Hempel, 2022; Khan et al., 2022; Bumann, 2021; Sivonen & Koivula, 2020; Drews & van den Bergh, 2016a).

This suggests that strong environmental policies, especially when coupled with social policies that are strongly left of centre, may struggle to escape a smaller constituency of left-wing voters. In other words, an impression of degrowth as a form of ecosocialism can also present a major challenge for degrowth in terms of the current public mood (Albert, 2022; Buch-Hansen, 2018).

We know very little about popular support for degrowth aims and specific policy proposals. Using a single question that has featured in a number of surveys in recent decades, Paulson & Büchs (2022) and Gugushvili (2021) revealed that the majority of people in many European countries are in favour of prioritising the environment, even if this would lead to job losses or slower economic growth. Utilising a large number of items that better reflect discussions of green growth, degrowth and a-growth, Drews & van den Bergh (2016b) found that around a third of the Spanish population holds a growth-critical stance in opposition to green growth.

In addition, even less is known about public support specifically for the more radical social policies advocated in the degrowth literature. Khan et al. (2022) measured the support for five prominent ecosocial (and degrowth-related) policies in Sweden, namely a reduction in working hours, wealth tax, maximum income, basic income and meat tax. The most popular policy was a reduction in working hours, with support from around 50% of the population, followed by a wealth tax and meat tax at 40% and 30%, respectively, while maximum income and basic income only gained support from 25% and 15%, respectively. The study also found that the dominant predictor of support for such policies is left-right orientation, rather than pro-environmental attitudes.

More is known about support for UBI specifically, especially following a new item introduced to the European Social Survey in 2016 (Chrisp et al., (2020); Roosma, van Oorschot (2020)). In Europe, support varied from large minorities to clear majorities in favour, with higher support in countries where existing safety nets are less encompassing.

In short, although the research is still limited, we see a mix of strong ideological barriers with some potential for wider support. For advocates of degrowth, this might be encouraging as they are far from the popular-movement-like dynamics they envisage, and considering that degrowth policies are not often promoted by established political actors.

Proponents of degrowth might find further hope of escaping the current barriers in the nascent research on ‘social tipping points’ and how this relates to pro-environmental behaviours and attitudes (Andrighetto & Vriens, 2022; Winkelmann et al., 2022; Otto et al., 2020). This research investigates how marginal movements and small minorities above a certain threshold of public involvement or support can at times give birth to broader, more popular shifts and rapid changes. The thresholds in this research vary from small, marginal minorities to larger minorities, but the main point is that it is possible for initially small movements to trigger rapid, non-linear societal transformations.

However, degrowth still presupposes a non-trivial change with respect to fundamental values or norms and identities. This was previously outlined as a cultural shift from hedonic to eudaimonic and needs-based conceptualisations of wellbeing. This is a larger ambition and challenge for degrowth. It is intended to be an emancipatory vision for a new wellbeing economy, but the concept of degrowth, as well as ‘needs’ and ‘sufficiency’, might carry entirely different connotations to austerity, inconvenience and constraints from a ‘wants-based’ or hedonic approach. For the same reason, some advocates have discussed whether ‘degrowth’ is a ‘missile word that backfires’ and whether other terms should be used in public discussions (Drews & Antal, 2016). Other, more positive frames of the basic vision might appeal to broader segments of the population (Smith, Baranowski & Schmid, 2021; Drews & Antal, 2016).

Conclusion

The aims propagated by the degrowth literature imply radical societal transformations. Many (but not all) authors even argue that it would (and should) do away with capitalism itself (Saito, 2022; Kallis, 2019; Andreucci & McDonough, 2015; Demaria et al., 2013). Regardless, the facts established by ecological economics and empirical research into the links between exponential economic growth, the resource throughput of the economy and degradation of the planet arguably demand transformative changes. Such changes may be comparable to those experienced only a few times before in human history, for instance the onset of agriculture and later industrialisation (Pichler, 2023; Hagens, 2020; Haberl et al., 2011).

Both within and across nations, greater equality of needs satisfaction and wellbeing is not only an optional shortcut to sustainability, but arguably a necessary condition (if not by itself sufficient). Furthermore, excess inequality may lead to collective action becoming nigh impossible, as high stratification leads to diverging interests, just as elites and wealthier countries can shelter themselves from crises in the short term (Brozovic, 2023; Motesharrei et al., (2014)).

The academic literature on degrowth argues that combinations of major policy reforms and civil society alternatives are mutually complementary, or that both ‘symbiotic’ and ‘interstitial’ transformations are needed (Chertkovskaya, 2022; Koch, 2022a, 2022b; D’Alisa & Kallis, 2020). Yet these different strands of degrowth also harbour some inherent tensions and challenges. This paper has derived three of these:

Firstly, these ideas and proposals amount to encompassing social policies, and even if such reforms are necessary to bridge social and environmental sustainability, the growth dependencies of the current welfare state must be further addressed. Bailey (2015) outlined this as a ‘welfare paradox’ in which extensive social policymaking is needed beyond growth, yet the fiscal viability of the established welfare state would also be challenged. Labour-intensive care services might be particularly challenged here.

Secondly, when combined with changes ‘from below’ based on commoning and convivialism, it is not always clear what room there could or should be for extensive state-led decommodification and welfare provision when we simultaneously envisage a bigger role for the alternative and informal economy.

Thirdly, while there is potential for broad, public support, degrowth as a movement still has some way to go before the public could be convinced of the more radical policies that would substantially transform the growth-based political economy. Consistent support across major policy proposals is limited to the green or new left.

The first two challenges have been derived by questioning where there are potential limits for formal welfare or service provision in a political economy of degrowth, firstly with respect to such policies in and of themselves, and secondly with respect to their balance (potential complementarities or trade-offs) vis-à-vis alternatives based on informal commoning and convivialism. If degrowth entails both less and more of the existing alternatives and institutions (Buch-Hansen & Nesterova, 2023), I have questioned whether we need more research on what should be considered ‘less’ in terms of formal social policies. For instance, what aspects of social reproduction should be formally decommodified and what should be left for commoning in local, alternative or informal economies?

In terms of fiscal viability, degrowth advocates and ecological economists rightly point to the role of the financial sector and monetary policy in terms of enforcing the growth imperative, and how reforms here, alongside radical redistribution, are necessary complements to the decommodification of goods and services (Jackson, Jackson & van Lerven, 2022; Fitzpatrick, Parrique & Cosme, 2022; Parrique, 2019). Olk et al., (2023) discuss how the ideas in ‘modern monetary theory’ may inform the regulation of private finance, private money creation, employment and tax reforms in order to both secure public provisioning and eliminate growth dependencies.

Still, efforts to clearly define a ‘sufficiency-oriented’ or ‘foundational’ economy (see for instance Bärnthaler & Gough, 2023; Wahlund & Hansen, 2022) require more explicit and critical work on the extent to which some aspects of welfare provision (services and aspects of social reproduction) could or should be provided by public social policies in an economy based on sufficiency, foundational needs and commoning. The aim should be to naunce what a future ‘mixed economy of degrowth’ could imply, emphasizing that public commodification does not necessarily imply goods that are entirely publicly regulated, delivered and financed across all needs (such nuances are addressed with different concepts by, for instance, Wahlund & Hansen, 2022; Coote, 2022 and Bohnenberger, 2020), just as commoning need not be entirely informal or organized solely in alternative economies.

The third and final challenge concerns attitudes, perceptions and values among the wider public. Proponents of more radical environmental transformations often point to power structures and the need to break with vested economic interests in fossil fuels, extractionism, etc., as well as excess levels of inequality, which are certainly the major culprits behind past failures to take sufficient political action (Stoddard et al., 2021). Degrowth might have traction as an issue of environmental justice and class struggle.

Yet, particularly in affluent economies, degrowth would also require new popular conceptions or values with respect to wellbeing and the good life that would also change the behaviours that bring social recognition and status. As a movement, degrowth has some way to go in achieving the ‘social tipping points’ that would eventually lead to the new norms, values and identities presupposed by degrowth with respect to less materialist and hedonic and more needs-oriented and eudaimonic conceptions of wellbeing and happiness.

Transformations of this magnitude might need to complement and reinforce each other. While the literature has generally tended to focus separately on formal policies or non-institutionalised alternatives, some research has managed to spell out what this entails in terms of dynamics and strategies of change, as well as the role of different types of actors, sometimes inspired by other theories of social change (see for instance Buch-Hansen & Nesterova, 2023; Pichler, 2023; Durand, Hofferberth & Schmelzer, 2023; Schulken et al., 2022; Koch, 2022a, 2022b, D’Alisa & Kallis, 2020). This paper emphasises that there is room for more work on the viability and role of formal, public social policies and achieving the public legitimacy that is needed.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this research as no data were generated or analysed.

References

Albert M (2022a) Ecosocialism for realists: transitions, trade-offs, and authoritarian dangers. Capital. Nat. Social. 34:1–21

Alexander S (2012a) Planned economic contraction: the emerging case for degrowth. Env. Polit. 21(3):349–368

Alexander, S (2012b) Ted Trainer and the simple way. University of Melbourne, Australia

Andreucci D, McDonough T (2015) Capitalism. In: D’Alisa G, Demaria F, Kallis G (eds.) Degrowth: A vocabulary for a new era, 1st edn. Routledge, Abingdon, p 84–87

Andrighetto G, Vriens E (2022) A research agenda for the study of social norm change. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 380:1–13

Antal M (2014) Green goals and full employment: are they compatible? Ecol. Econ. 107:276–286

Antal M, Plank B, Mokos J, Wiedenhofer D (2020) Is working less really food for the environment? a systematic review of the empirical evidence for resource use, greenhouse gas emissions and the ecological footprint. Environ. Res. Lett. 16(1):1–19

Bailey D (2015) The environmental paradox of the welfare state: the dynamics of sustainability. New Polit. Econ. 20(6):793–811

Bärnthaler R, Gough I (2023) Provisioning for sufficiency: Envisaging production corridors. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 19(1):1–18

Bergquist M, Nilsson A, Harring N, Jagers S (2022) Meta-analyses of fifteen determinants of public opinion about climate change taxes and laws. Nat. Clim. Change 12(3):235–240

Berner A, Bruns S, Moneta A, Stern D (2022) Do energy efficiency improvements reduce energy use? empirical evidence on the economy-wide rebound effect in Europe and the United States. Energy Econ. 110:1–19

Best R, Zhang Q (2020) What explains carbon-pricing variation between countries. Energy Policy 143:1–11

Bianchi M, Cordella M (2023) Does circular economy mitigate the extraction of natural resources? empirical evidence based on analysis of 28 European economies over the past decade. Ecol. Econ. 203:1–11

Bohnenberger K (2020) Money, vouchers, public infrastructures? a framework for sustainable welfare benefits. Sustainability 12(2):1–30

Bouman S, Steg L, Kiers H (2018) Measuring values in environmental research: a test of an environmental portrait value questionnaire. Front. Pshychol. 9:1–15

Bradshaw C, Ehrlich P, Beattie A, Ceballos G, Crist E, Diamond J, Dirzo R, Ehrlich A, Harte J, Harte M, Pyke G, Raven P, Ripple W, Saltré F, Turnbull C, Wackernagel M, Blumstein D (2021) Underestimating the challenges of avoiding a ghastly future. Front. Conserv. Sci. 1:615419

Brand U (2022) Radical emancipatory social-ecological transformations: Degrowth and the role of strategy. In: Barlow N, Regen L, Cadiou N, Chertkovskata E, Hollweg M, Plank, C, Schulken, M, Wolf V (eds.) Degrowth & strategy. How to bring about social-ecological transformation, 1st edn. Mayfly Books, p 37–55

Brozovic D (2023) Societal collapse: a literature review. Futures 145:1–24

Buch-Hansen H (2018) The prerequisites for a degrowth paradigm shift: insights from critical political economy. Ecol. Econ. 146:157–163

Buch-Hansen H, Carstensen M (2021) Paradigms and the political economy of ecopolitical projects: green growth and degrowth compared. Compet. Change 25(3):308–327

Buch-Hansen H, Nesterova I (2023) Less and more: conceptualizing degrowth transformations. Ecol. Econ. 205:1–9

Büchs M (2021) Sustainable welfare: how do universal basic income and universal basic services compare? Ecol. Econ. 189:1–9

Büchs M, Koch M (2019) Challenges for the degrowth transition: the debate about wellbeing. Futures 105:155–165

Bumann S (2021) What are the determinants of public support for climate policies? a review of the empirical literature. Rev. Econ. 72(3):213–222

Burkhart C, Schmelzer M, Treu N (2020) Introduction: degrowth and the emerging mosaic of alternatives. In: Burkhart C, Schmelzer M, Treu N (eds.) Degrowth in movement(s). Exploring pathways for transformation, 1st edn. Zero Books, Winchester, p. 8–32

Burstein P (2003) The impact of public opinion on public policy: a review and an agenda. Polit. Res. Quart. 56(1):29–40

Chancel L, Bothe P, Voituriez T (2023) Climate inequality report 2023. World Inequality Lab Study 2023/1

Chertkovskaya E, (2022) A strategic canvas for degrowth: In dialogue with Erik Olin Wright. In: Barlow N, Regen L, Cadiou N, Chertkovskata E, Hollweg M, Plank, C, Schulken, M, Wolf V (eds.) Degrowth & strategy. How to bring about social-ecological transformation, 1st edn. Mayfly Books, p. 56–76

Chung H (2022) A social policy case for a four-day week. J. Soc. Policy 51(3):551–566

Chrisp J, Laenen T, van Oorschot W (2020) The social legitimacy of basic income: a multidimensional and cross-national perspective. An introduction to the special issue. J. Int. Compar. Soc. Policy 36(3):217–222

Collste D, Cornell S, Randers J, Rockström J, Stoknes P (2021) Human well-being in the anthropocene: limits to growth. Glob Sustain. 4(30):1–9

Coote A (2022) Towards a sustainable welfare state: the role of universal basic services. Soc. Policy Soc. 21(3):473–483

Cosme I, Santos R, O’Neill D (2017) Assessing the degrowth discourse: a review and analysis of academic degrowth policy proposals. J. Clean. Prod. 149:321–334

D’Alisa G, Kallis G (2020) Degrowth and the state. Ecol. Econ. 169:1–9

Daly H (2007) Ecological economics and sustainable development: selected essays of Herman Daly. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Dechezleprêtre A, Fabre A, Kruse T, Planterose B, Chico A, Stantcheya S (2022) Fighting climate change: International attitudes toward climate policies. OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1714

Demaria F, Schneider F, Sekulova F, Martinez-Alier J (2013) What is degrowth? from an activist slogan to a social movement. Environ. Values 22(2):191–215

Deriu M (2015). Conviviality. In: D’Alisa G, Demaria F, Kallis G (eds.) Degrowth: A vocabulary for a new era, 1st edn. Routledge, Abingdon, p. 104–107

Derndorfer J, Hoffmann R, Theine H (2022) Integrating environmental issues within party manifestos: Exploring trends across European welfare states. In: Schoyen M, Hvinden B, Leiren D (eds.) Towards sustainable welfare states in Europe, 1st edn. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, p. 80–108

Dietz T, Fitzgerald A, Shwom R (2005) Environmental values. Annu. Rev. Environ. Res. 30:335–372

Doyal L, Gough I (1991) A theory of human need. Red Globe Press, London

Drews S, Antal M (2016) Degrowth: a ‘missile word’ that backfires? Ecol. Econ. 126:182–187

Drews S, van den Bergh J (2016a) What explains public support for climate policies? a review of empirical and experimental Studies. Clim. Policy 16(7):855–876

Drews S, van den Bergh J (2016b) Public views on economic growth, the environment and prosperity: results of a questionnaire survey. Glob. Environ. Change 39:1–14

Dryzek J (2008) The ecological crisis of the welfare state. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 18(4):334–337

Durand C, Hofferberth E, Schmelzer, M (2023) Planning beyond growth. The case for economic democracy within limits. Political economy working papers 1/2023. Department of History, Economics and Society, University of Geneva

Emilsson K (2022) Support for sustainable welfare? A study of public attitudes related to an eco-social agenda among Swedish residents. Dissertation, School of Social Work, Lund University

Emilsson K (2022b) Attitudes towards welfare and environmental policies and concerns: a matter of self-interest, personal capability, or beyond? J. Eur. Soc. Policy 32(5):592–606

Esping-Andersen G (1990) The three worlds of welfare capitalism. University Press, Princeton

European Environment Agency (2021). Reflecting on green growth. Creating a resilient economy within environmental limits. European Environment Agency, Copenhagen

Fanning A, O’Neill D, Hickel J, Roux N (2021) The social shortfall and ecological overshoot of nations. Nat. Sustain. 5:26–36

Finnegan J (2022) Institutions, climate change, and the foundations of long-term policymaking. Compar. Polit. Stud. 55(7):1198–1235

Fioramonti L, Coscieme L, Costanza R, Kubiszewski I, Trebeck K, Wallis S, Roberts D, Mortensen L, Pickett K, Wilkinson R, Ragnarsdottir V, McGlade J, Lovins H, De Vogli R (2022) Wellbeing economy: an effective paradigm to mainstream post-growth policies? Ecol. Econ. 192:1–8

Fitzpatrick N, Parrique T, Cosme I (2022) Exploring degrowth policy proposals: a systematic mapping with thematic dynthesis. J. Clean. Prod. 365:1–19

Fritz M, Koch M (2016) Economic development and prosperity patterns around the world: structural challenges for a global steady-state economy. Glob. Environ. Change 38:41–48

Fritz M, Koch M (2019) Public support for sustainable welfare compared: links between attitudes towards climate and welfare policies. Sustainability 11(5):1–15

Gaikwad N, Genovese F, Tingley D (2022) Creating climate coalitions: mass preferences for compensating vulnerability in the world’s two largest democracies. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 116(4):1165–1183

Garcia-Garcia P, Buendia L, Carpintero O (2022) Welfare regimes as enablers of just energy transitions: revisiting and testing the hypothesis of synergy for Europe. Ecol. Econ. 197:1–14

Gore T (2021) Carbon inequality in 2030. Per capita consumption emissions and the 1.5o Goal. Oxfam, Oxford

Gorz A (1994) Capitalism, Socialism, Ecology. Verso, London

Gough I (2022) Two scenarios for sustainable welfare: A framework for an eco-social contract. Soc. Policy Soc. 22(3):460–472

Gugushvili D (2021) Public attitudes toward economic growth versus environmental sustainability dilemma: evidence from Europe. Int. J. Compar. Sociol. 62(3):224–240

Haberl H, Fischer-Kowalski M, Krausmann F, Martines-Alier J, Winiwarter V (2011) A socio-metabolic transition towards sustainability? challenges for another great transformation. Sustain. Dev. 19(1):1–14

Haberl H, Wiedenhofer D, Virág D, Doris K, Kalt G, Plank B, Brockway P, Fishman T, Hausknos D, Krausmann F, Leon-Gruchalski B, Mayer A, Pichler M, Schaffartzik A, Sousa T, Streeck J, Creutzig F (2020) A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: synthesizing the insights. Environ. Res. Lett. 15(6):1–42

Hagens N (2020) Economics for the future—beyond the superorganism. Ecol. Econ. 169:1–16

Hardin G (1968) The tragedy of the Commons. Science 162(3859):1243–1248

Hartley T, van den Bergh J, Kallis G (2020) Policies for equality under low or no growth: a model inspired by Piketty. Rev. Polit. Econ. 32(2):243–258

Hasanaj V (2022) Global patterns of contemporary welfare states. J. Soc. Policy 52(4):886–992

Heggebø K, Hvinden B (2022) Attitudes towards climate change and economic inequality: A cross-national comparative study. In: Schoyen M, Hvinden B, Leiren D (eds.) Towards sustainable welfare states in Europe, 1st edn. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, p 53–79

Helfrich H, Bollier D (2015) Commons. In: D’Alisa G, Demaria F, Kallis G, (eds.) Degrowth: A vocabulary for a new era, 1st edn. Routledge, Abingdon, p. 74–78

Herrington G (2021) Update to limits to growth: comparing the World3 model with empirical data. J. Indust. Ecol. 25(3):614–626

Hickel J (2020) Less is more. How degrowth will save the world. William Heinemann, London

Hickel J (2021) What does degrowth mean? A few points of clarification. Globalizations 18(7):1105–1111

Hickel J, Kallis G (2020) Is green growth possible? New Polit. Econ. 25(4):469–486

Hickel J, Sullivan D, Zoomkawala H (2021) Plunder in the post-colonial era: quantifying drain from the global south through unequal exchange 1960–2018. New Polit. Econ. 26(6):1030–1047

Hickel J, Dorninger C, Wieland H, Suwandi I (2022) Imperialist appropriation in the world economy: drain from the global south through unequal exchange 1990–2015. Glob. Environ. Change 73:1–14

Hirvilammi T (2020) The virtuous circle of sustainable welfare as a transformative policy idea. Sustainability 12(1):1–15

Hirvilammi T, Koch M (2020) Sustainable welfare beyond growth. Sustainability 12(5):1–8

Hirvilammi T, Häikiö L, Johansson H, Koch M, Perkiö J (2023) Social policy in a climate emergency context: towards an ecosocial research agenda. J. Soc. Policy 52(1): 1–27

Hubacek K, Wieland H (2021) Global patterns of ecologically unequal exchange: implications for sustainability in the 21st Century. Ecol. Econ. 179:1–14

Hubacek K, Chen X, Feng K, Wiedmann T, Shan Y (2021) Evidence of decoupling consumption-based CO2 emissions from economic growth. Adv. Appl. Energy 4:1–10

IPBES (2019). Global assessment report of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem Services. IPBES, Bonn

IPCC (2022). Climate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. Summary for policymakers. working group III contribution to the IPCC sixth assessment report. University Press, Cambridge

Isham A, Verfuerth C, Armstrong A, Elf P, Gatersleben B (2022) The problematic role of materialistic values in the pursuit of sustainable well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:1–20

Jackson T (2016) Prosperity without growth. Foundations for the economy of tomorrow. Taylor & Francis, Milton Park

Jackson T (2021) Post growth—life after capitalism. Polity Press, Cambridge

Jackson A, Jackson T & van Lerven, F (2022) Beyond the debat controversy–re-framing fiscal and monetary policy for a post-pandemic era. Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity (CUSP) working paper no. 31

Jakob M, Lamb W, Steckel J, Flachsland C, Edenhofer O (2020) Understanding different perspectives on economic growth and climate policy. WIREs Clim. Change 11(6):1–17

Jaureguiberry P, Titeaux N, Wiemers M, Bowler D, Cosciemes L, Golden A, Guerra, C, Jacob U, Takahashi Y, Settele J, Diaz S, Molnar Z, Purvis, A (2022) The direct drivers of recent global anthropogenic biodiversity loss. Sci. Adv. 8(45):eabm9982

Kallis G (2019) Socialism without growth. Capital. Nat. Social. 30(2):189–206

Kallis G, Demaria F, D’Alisa G (2015) Introduction: Degrowth. In: D’Alisa G, Demaria F, Kallis G, (eds.) Degrowth: A vocabulary for a new era, 1st edn. Routledge, Abingdon, p. 1–17

Kallis G, Kostakis V, Lange S, Muraca B, Paulson S & Schmelzer M (2018) Research on degrowth. Annu. Rev. Environ. Res. 43(1): 291–316

Khan J, Emilsson K, Fritz M, Koch M, Hildingsson R, Johansson H (2022) Ecological ceiling and social floor: public support for eco-social policies in Sweden. Sustain. Sci. 2022:1–14

Kenny J, Langsæther P (2022) Environmentalism as an independent dimension of political preferences. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 62:1031–1053

Ketterer H (2021) Living differently? A feminist-Bourdieausian analysis of the transformative power of basic income.Sociol. Rev. 69(6):1309–1324

Kim Y, Sommet N, Jinkyung N, Spini D (2022) Social class—not income inequality—predicts social and institutional trust. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 13(1):186–198

King L, Savin I, Drews S (2023) Shades of green growth scepticism among climate policy researchers. Nat. Sustain. 312:1644

Koch M (2022) State-civil society relations in Gramsci, Poulantzas and Bourdieu: strategic implications for the degrowth movement. Ecol. Econ. 193:1–9

Koch M (2022) Rethinking state-civil society relations. In: Barlow N, Regen L, Cadiou N, Chertkovskata E, Hollweg M, Plank, C, Schulken, M, Wolf V (ed.) Degrowth & strategy. How to bring about social-ecological transformation, 1st edn. Mayfly Books, p 170–181

Koch M (2022c) Social policy without growth: Moving towards sustainable welfare states. Soc. Policy Soc. 21(3):447–459

Koch M, Fritz M (2014) Building the eco-social state: Do welfare regimes matter? J. Soc. Policy 43(4):679–703

Lamb W, Steinberger J (2017) Human well-being and climate change mitigation. WIREs Clim. Change 8(6):1–6

Lamb W, Minx J (2020) The political economy of national climate policy: architectures of constraint and a typology of countries. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 64:1–16

Lamb W, Grubb M, Diluiso F, Minx J (2021) Countries with sustained greenhouse emissions reductions: an analysis of trends and progress by sector. Clim. Policy 22(1):1–17

Latouche S (2009) Farewell to growth. Polity Press, Cambridge

Lehmann C, Delbard O, Lange S (2022) Green growth, a-growth or degrowth? Investigating the attitudes of environmental protection specialists at the German Environment Agency. J. Clean. Prod. 336:1–22

Le Quéré C, Korsbakken J, Wilson C, Tosun J, Andrew R, Andres R, Canadell J, Jordan A, Peters G, van Vuuren D (2019) Drivers of declining CO2 emissions in 18 developed economies. Nat. Clim. Change 9:213–217

Malerba D (2022) The effects of social protection and social cohesion on the acceptability of climate change mitigation policies: what do we (not) know in the context of low and middle-income countries? Eur. J. Dev. Res. 34:1358–1382

Mastini R, Kallis G, Hickel J (2021) A green new deal without growth? Ecol. Econ. 179:1–9

Max-Neef M (1991) Human scale development. Conception, application and further reflections. Zed Books, London

McGann M, Murphy M (2023) Income support in an eco-social state: The case for participation income. Soc. Policy Soc. 22(1):16–30

Meadows D, Randers J, Meadows D (2004) Limits to growth: The 30-year update. Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction

Millward-Hopkins J (2022) Inequality can double the energy required to secure universal decent living. Nat. Commun. 13:1–9

Mont O, Lehner M, Dalhammar (2022) Sustainable consumption through policy intervention—a review of research themes. Front. Sustain. 3:1–15

Motesharrei S, Rivas J, Kalnay E (2014) Human and nature dynamics (HANDY): modeling inequality and use of resources in the collapse or sustainability of societies. Ecol. Econ. 101:90–102

Novy A (2022) The political trilemma of contemporary social-ecological transformation—lessons from Karl Polanyi’s the great transformation. Globalizations 19(1):59–80

Oberholzer B (2023) Post-growth transition, working time reduction, and the question of profits. Ecol. Econ. 203:1–10

Obura D, DeClerck F, Verburg P, Gupta J, Abrams J, Bai X, Bunn S, Ebi K, Gifford L, Gordon C, Jacobson L, Lenton T, Liverman D, Mohamed A, Prodani K, Rocha J, Rockstro J, Sakschewski B, Stwart-Koster B, van Vuuren D, Winkelmann R, Zimm C (2022). Achieving a nature- and people-positive future. One Earth https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2022.11.013

Olk C, Schneider C, Hickel J (2023). How to pay for saving the world: modern monetary theory for a degrowth transition. Ecol. Econ. 214:107968

Ostrom E (1990) Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. University Press, Cambridge

Otto A, Gugushvili D (2020) Eco-social divides in Europe: public attitudes towards welfare and climate change policies. Sustainability 12(1):404

Otto I, Donges J, Cremades R, Bhowmik A, Hewitt R, Lucht W, Rockström J, Allerberger F, McCaffrey M, Doe S, Lenferna A, Moran N, van Vurren D, Shellnhuber J (2020) Social tipping points for stabilizing Earths climate by 2050. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117(5):2354–2365

Ottelin J, Heinonen J, Junnila S (2018) Carbon and material footprints of a welfare state: Why and how governments should enhance green investments. Environ Sci Policy 86:1–10

Parrique T (2019) The political economy of degrowth dissertation. University of Stockholm, Swedan

Parrique T, Barth J, Briens F, Christian K, Kraus-Polk A, Kuokkanen A, Spangenberg J (2019) Decoupling debunked. Evidence and arguments against green growth as a sole strategy for sustainability. European Environmental Bureau, Brussels

Parth A-M, Vlandas T (2022) The welfare state and support for environmental action in Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 32(5):531–547

Paulson L, Büchs M (2022) Public acceptance of post-growth: factors and implications for post-growth strategy. Futures 143:1–15

Pichler M (2023) Political dimensions of social-ecological transformations: Polity, politics, policy. Sustainability. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 19(1):1–15

Pihl E, Alfredsson E, Bengtsson M, Bowen K et al. (2021) Ten new insights in climate science 2020—a horizon scan. Glob. Sustain. 4(5):1–18

Polanyi K (1944) The great transformation. Farrar & Rhinehart, New York

Pullinger M (2014) Working time reduction policy in a sustainable economy: criteria and options for its design. Ecol. Econ. 103:11–19

Raworth K (2017) Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st century economist. Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction

Rilovic A, Hepp C, Saey-Volckrick J, Herbert J, Bardi C, Carol (2022) Degrowth actors and their strategies: Towards a degrowth international. In: Barlow N, Regen L, Cadiou N, Chertkovskata E, Hollweg M, Plank, C, Schulken, M, Wolf V (eds.) Degrowth & strategy. How to bring about social-ecological transformation, 1st edn. Mayfly Books, p. 93–109

Ripple W, Wolf C, Newsome T, Barnard P, Moomaw W (2021) World scientists’ warning of a climate emergency. BioSci. 70(1):8–12

Roosma F, van Oorschot W (2020) Public opinion on basic income: mapping European support for a radical alternative for welfare provision. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 30(2):190–205

Ryff C (1989) Happiness is everything, or is it? explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57(6):1069–1981

Ryff C (2017) Eudaimonic well-being, inequality, and health: recent findings and future directions. Int. Rev. Econ. 64:159–178

Saito, K (2022) Marx in the Anthropocene. Towards the idea of degrowth communism. University Press, Cambridge

Schaffer LM, Oehl B, Bernauer T (2022) Are policymakers responsive to public demand in climate politics? J. Public Policy 42(1):136–164

Schoyen M, Hvinden B, Leiren D (2022) Welfare state sustainability in the 21st century. In: Schoyen M, Hvinden B, Leiren D (eds.) Towards sustainable welfare states in Europe, 1st edn. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, p. 2–27

Schmelzer M, Vetter A, Vansintjan A (2022) The future is degrowth. A guide to a world beyond capitalism. Verso, London

Schulken M, Barlow N, Cadiou N, Chertkovskata E, Hollweg M, Plank C, Regen L, Wolf V (2022) Introduction: strategy for the multiplicity of degrowth. In: Barlow N, Regen L, Cadiou N, Chertkovskata E, Hollweg M, Plank, C, Schulken, M, Wolf V (eds.) Degrowth & strategy. How to bring about social-ecological transformation, 1st edn. Mayfly Books, p. 9–36

Sivonen J, Koivula (2020) How do social class position and party preference influence support for fossil fuel taxation in the Nordic countries? J. Soc. Sci. 2020:1–21

Sivonen J, Kukkonen I (2021) Is there a link between welfare regime and attitudes toward climate policy instruments. Sociol. Persp. 64(6):1145–1165

Smith E, Hempel L (2022) Alignment of values and political orientations amplifies climate change attitudes and behaviors. Clim. Change 172(4):1–28

Smith T, Baranowski M, Schmid B (2021) Intentional degrowth and its unintended consequences: Uneven journeys towards post-growth transformations. Ecol. Econ. 190:1–8

Spangenberg J, Lorek S (2019) Sufficiency and consumer behavior: from theory to policy. Energy Policy 129:1070–1079

Standing G (2017) Basic income and how we can make it happen. Pelican, London

Stoddard I, Anderson K, Capstick S, Carton W, Depledge J, Facer K, Gough C, Hache F, Hoolohan C, Hultman M, Hällström N, Kartha S, Klinsky S, Kuchler M, Lövbrand E, Nasiritousi N, Newell P, Peters G, Sokona Y, Stirling A, Stilwell M, Spash C, Williams M (2021) Three decades of climate mitigation: why haven’t we bent the global emissions curve? Annu. Rev. Environ. Res. 46:653–689

Trainer T (2010) The transition to a sustainable and just world. Envirobook, Sydney

United Nations (2022) COP15—UN Secretary-General’s Remarks to the UN Biodiversity Conference https://unric.org/it/cop15-un-secretary-generals-remarks-to-the-un-biodiversity-conference/

Vadén T, Lähde V, Antti M, Järvensivu P, Toivanen T, Hakala E, Eronen J (2020) Decoupling for ecological sustainability: A categorisation and review of research literature. Environ. Sci. Policy 112:236–244

Van den Bergh J, Kallis G (2012) Growth, a-growth or degrowth to stay within planetary boundaries? J. Econ. Issues 46(4):909–918

Vogel J, Steinberger J, O’Neill D, Lamb W, Krishnakumar J (2021) Socio-economic conditions for satisfying human needs at low energy use: An international analysis of social provisioning. Global Environ. Change 69:1–15

Vogel J, Hickel J (2023) Is green growth happening? An empirical analysis of achieved versus Paris-compliant CO2-GDP decoupling in high-income countries. Lancet Planetary Health e7:e759–e769

Wahlund M, Hansen T (2022) Exploring alternative economic pathways: a comparison of foundational economy and doughnut economics. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 18(1):171–186

Walker C, Jackson T (2021). Tackling growth dependency—the case of adult social care. Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity (CUSP) working paper no. 28

Walker C, Druckman A, Jackson T (2021) Welfare systems without economic growth: a review of the challenges and next steps for the field. Ecol. Econ. 186:1–12

Ward J, Sutton P, Werner A, Costanza R, Mohr S, Simmons C (2016) Is decoupling GDP growth from environmental impact possible. PLoS One 11(10):1–14

Wiedmann T, Lenzen M, Keyβer L, Steinberger J (2020) Scientists’ warning on affluence. Nat. Commun. 11(1):3107

Wilkinson R, Pickett K (2017) The enemy between us: the psychological and social costs of inequality. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 57(1):11–24

Willis G, Garcia-Sanchez E, Sanchez-Rodriguez A, Garcia-Castro J, Rodriguez-Bailon R (2022) The psychosocial effects of economic inequality depend on its perception. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1:301–309

Wiedmann T, Schandl H, Lenzen M, Moran D, Suh S, West J, Kanemotoc K (2015) The material footprint of nations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 112(7):6271–6276

Winkelmann R, Donges J, Smith K, Milkoreit M, Eder C, Heitzig J, Katsanidou A, Wiedermann M, Wunderling N, Lenton T (2022) Social tipping points processes towards climate action: a conceptual framework. Ecol. Econ. 192(1):107242

Wright EO (2019) How to be an anti-capitalist in the 21st century. Verso, London

Zimmermann K, Graziano P (2020) Mapping different worlds of eco-welfare states. Sustainability 12(5):1–20

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author is the sole contributing author to this article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval