Abstract

This study focused on the factors that influence innovation performance in housing agents. Based on a worldwide literature review on the topic of innovation performance, we defined relational capital, knowledge sharing at the individual level, and organizational culture, structural capital, and human resource management practices at the organizational level to carry out the analysis using hierarchical linear modeling. The survey subjects were housing agents in Kaohsiung City, Taiwan. A total of 1130 questionnaires were distributed to 113 agencies. Of a total of 444 collected surveys, 40 unanswered questionnaires were invalid and three with fewer than three answers were eliminated. The final number of valid questionnaires was 401. The response rate of effective questionnaires was 35.49%. The results show that organizational culture can indirectly affect innovation performance through knowledge sharing, indicating that there is a partial mediating effect. Structural capital can indirectly affect innovation performance through knowledge sharing, demonstrating a complete mediating effect. Relational capital can indirectly affect innovation performance through knowledge sharing, having a partial mediating effect. Human resource management practices did not have a confounding effect on innovation performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Innovation performance reflects an organization’s ability to transform innovation inputs into outputs and to acquire achievements and outcomes through the innovation process. Wang and Lee (2018) regarded innovation strategies as applying innovation to maximize an enterprise’s value. West and Anderson (1996) pointed out that innovation is crucial to social or organizational development and advancement. Innovation performance includes employee growth, team cohesion, effective internal communication, and continuous improvements in other related performances. In the technology sector, Ma et al. (2023) showed that innovation performance can be better generated when companies proactively accept external information and engage in intra-organizational knowledge transfer with the acquired information. Taking a service-oriented approach, Yiu et al. (2020) suggested that innovation performance can be enhanced through mutual learning, in which knowledge sharing and transfer occur between partners within an organization.

These arguments highlight the importance of innovation performance in various industries.

Most of the research on innovation performance in the real estate agency industry is centered on the financial and service aspects (Hameed et al., 2021; Rajapathirana and Hui, 2018). The financial aspect is measured through various factors, including performance-based bonuses, business performance, the number of transactions, and organizational financial status (see Yu and Liu, 2004; Lee and You, 2007; Meslec et al., 2020). Real estate agents aim toward achieving strong individual performances for the sake of their own bonuses (Mallik and Harker, 2004; Bradler et al., 2019; Manzoor et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2023). The service aspect is measured through factors such as research satisfaction and service quality (see Wu, 1999; Wang, 2004; Ullah and Sepasgozar, 2019; Yeh et al., 2020).

In the real estate agency industry, direct sales business operators may adopt the competition strategy of branch cooperation, as the internal systems and organization inside a branch are closely associated. Organizational culture includes the values, forms, and traditions conveyed by the organization to all its members (Ouchi, 1981). Narver and Slater (1990) suggested that organizational culture can be measured through the three components of market orientation: customer orientation, competitor orientation, and interdepartmental coordination. Lee and Sheng (2022) suggested that shared beliefs, expectations, values, norms, and routine tasks influence the relationship and methods of cooperation between organizational members, effectively creating different organizational values. Since the real estate agency industry is a part of the service industry, having a customer orientation is conducive to improving the quality of interactions between employees and customers (Bitner et al., 1994; Bowen and Schneider, 1985). Interdepartmental coordination is also associated with the human resources within the organization. Competition among enterprises has intensified in response to globalization, which highlights the importance of human resource management. In this 21st-century global economy driven by services, knowledge, technology, innovation, and globalization, human resource management (HRM) remains among the main models of competition management in local and foreign companies as well as emerging or established markets (Thite, 2015). Dessler (2000) stressed the importance of HRM for an enterprise. The functions of HRM include talent recruitment and selection, promotion and allocation, training and development, remuneration and benefits, labor relations, employment security, and labor safety. Well-executed HRM practices allow employees to improve organizational cohesion, teamwork, and organizational climate through self-directed work teams, inter-team cooperation, decision-making authorization, trustworthy organizational communications, and flexible management (Evans and Davis, 2005). To accurately and effectively allocate and leverage human resources, the real estate agency industry must rely on productive HRM practices (Wu, 2007). Therefore, adopting suitable HRM practices effectively improves elements such as employee training and development procedures (periodically arranging suitable internal and external training programs), performance evaluation (firm-specific evaluation criteria), and compensation and benefit packages (merit pay). Consequently, employees effectively enhance their innovative behavior at the individual and organizational levels through knowledge sharing, thus reducing their turnover (Hsu et al., 2021).

This study seeks to examine whether HRM evokes employees’ enthusiasm toward their jobs through motivational human resource activities such as human resource planning, training and development, remuneration and benefits, and employee relations, thereby increasing knowledge sharing and innovation performance within the organization. Additionally, it investigates whether the value generated from intangible intra-organizational assets and knowledge is key to an enterprise’s success. Such intangible assets and knowledge-creation mechanisms are collectively known as structural capital (Chen, 2007). Excellent structural capital not only improves an organization’s value but is also conducive to its development and enables it to gain continuous competitive advantages that can be converted into higher performances (Bontis et al., 2000; De Pablos, 2004). Structural capital includes an organization’s internal creativity and encompasses the development of new products, trade secrets, patents, and so on, which are also referred to as innovation capital. An organization’s internal infrastructure, including its management fad, corporate culture, management procedures, and information systems, is also known as process capital and represents major assets of structural capital (Saswat, 2018).

Moreover, real estate agent services are closely associated with the people involved. Of the personal relationship factors, relational capital is among the most important traits that real estate agents should possess. There are four types of intellectual capital: human capital, innovation capital, organizational capital, and relational capital (Tseng and Goo, 2005). In particular, relational capital refers to relationships that involve interpersonal trust and mutual identification (Cabrera and Cabrera, 2005). Numerous researchers have emphasized the important role of relational capital-associated factors in an organization’s business performance (Kogut and Zander, 1996; Uzzi, 1996; Saswat, 2018). Employees’ willingness to share knowledge is also based on the beliefs and behaviors associated with strong social interactions (Kim et al., 2013). Knowledge sharing is the mutual learning and understanding promoted through interaction and conversation between people (Lin and Wang, 2005). Knowledge sharing is crucial for externalizing individual knowledge within the organization, ensuring that employees who require such knowledge can effectively execute their work tasks. In other words, knowledge sharing is the transmission of knowledge to others anywhere, anytime (Wu and Lin, 2007). Several barriers also exist to knowledge sharing and organizational innovation. Firstly, an employee who feels that knowledge sharing is tedious and time-consuming may choose to hide knowledge so that they can save time and focus on their own tasks. Next, some knowledge is essentially confidential or sensitive information (such as personal connections or the knowledge to perform a task), and an employee can retain their competitive advantage by hiding this knowledge. Lastly, employees may worry that others will be skeptical of or criticize them for the knowledge that they share (Chen and Chen, 2022). Based on these arguments, we posit that individual relational capital is a key factor that affects personal knowledge sharing and innovation performance.

This study focused on organizational culture among real estate agents. Organizational culture can be described as a meaningful system with complex and profound effects. The complex and profound effects of organizational culture are mainly displayed through morals and values (Ke and Wei, 2008). Organizational culture is the sharing of values or beliefs to regulate the behaviors of organizational members (Geiger, 2017). For an enterprise or organization, human resources are an important internal resource while structural capital is a key internal element that creates value (Robbins, 2006). Previously, few studies within Taiwan and abroad have investigated the organizational level variables of organizational culture, structural capital, and HRM practices collectively. Unlike previous studies, this study examined the influence of these variables on knowledge sharing and innovation performance. In essence, relational capital, as part of intellectual capital, emphasizes connections with the external environment (Bontis, 1999). In this study, we categorized relational capital, knowledge sharing, and innovation performance as individual-level variables and collectively examined them alongside the aforementioned organizational-level variables. The goal was to investigate whether these two levels of variables positively affect innovation performance. Additionally, we considered HRM practices as a confounding variable that affects the influence of knowledge sharing on innovation performance.

Real estate agencies in Taiwan are commonplace. Countless real estate agency branches can be found nationwide, where many frontline real estate agents carve out their careers. In the past, the real estate industry in Taiwan was notorious for its sales tactics that often resulted in disputes. After the promulgation of the Real Estate Broking Management Act in 1999, the industry became professionally institutionalized. Due to the impacts of economic downturns, real estate agencies in recent years have turned to marketing their own brands. The industry adopted an atypical compensation scheme, based on commission. The industry is also known for its long work hours, challenging tasks, and high turnover. Thus, the means to enhance its innovation performance has gained much interest in academia and industry, most of which is directed at the organization’s internal business and management models. The influences of organizational culture, structural capital, HRM practices, relational capital, and knowledge sharing on innovation performance can shed light on the intra-organizational modes of operation of a real estate company, thus enabling research on and evaluation of the innovation performance of different industries.

Literature review and research hypotheses

Thanks to technological advancements, millennials (the demographic cohort currently aged 29 to 35 years) prefer to acquire consumer-related information from online platforms and visit physical stores after receiving marketing information online (Chang et al., 2023). As the popularity of artificial intelligence (AI) and the platform economy grows, the real estate agency industry has developed its own strategy, called property technology (PropTech), in response to technological advancements. PropTech refers to the consolidation of technology and real estate, whereby various emerging information and communications technologies are introduced into various fields of the real estate industry, enhancing the business efficiency of the overall industry and opening up new opportunities for innovative developments (Kuo, 2022). Lin (2021) identified several impacts of PropTech on the real estate agency industry: 1. Enhancing the efficiency of real estate transactions by increasing the convenience of acquiring information by sellers and buyers; 2. Providing new information rapidly and promoting transactions, such as generating empathetic responses through virtual reality settings in online platforms; 3. Unbundling real estate agents’ work tasks, in which traditional full-service tasks are split into several smaller ones, such as assigning dedicated personnel to assist house sellers or handling the company’s online business. This strategy provides a new stage for knowledge sharing and innovation in the business. This study will analyze the relationships between organizational culture and other internal factors in the industry.

The essence of organizational innovation is the means to effectively and adequately foster an excellent organizational culture that positively and significantly influences its performance (Daft, 2004; Lemon and Sahota, 2004). Hurley and Hult (1998) found that an organizational culture rooted in innovation can provide the organizational resources to help the organization leverage innovation to their advantage for progress. Organizational innovation is a part of organizational culture and is the precursor to innovation. Shahzad et al. (2017) revealed that organizational innovation performance is supported and influenced by organizational culture. Deal and Kennedy (1984) pointed out that a well-performing enterprise must have an excellent organizational culture as it is the main reason behind organizational innovation performance. Srisathan et al. (2020) examined the influence of organizational culture on open innovation performance using a sample of 300 Thai and Chinese small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). They demonstrated the significant influence of organizational culture on innovation performance concerning marketing, operations, customer orientation, and capital management. Aboramadan et al. (2020) contended that organizational culture positively influences market innovation and technology innovation. Srisathan et al. (2020) argued that organizational culture positively influences innovation performance through organizational sustainability. We propose H1 as follows:

H1: Organizational culture has a significant and positive influence on innovation performance.

Edvinsson and Malone (1997) described structural capital as an intangible organizational asset that cannot be taken away by employees when they resign. Furthermore, structural capital reflects an organization’s ability to function as one and is made up of organizational capital, process capital, and innovation capital. De Pablos (2004) observed that structural capital improves organizational value. Lin et al. (2011) conceptualized structural capital as an organization’s capacity to solve problems and create value in its general systems and procedures. Consequently, structural capital improves an organization’s competitiveness and innovation performance. Structural capital also reflects the mechanisms and capabilities within an organization that allow it to integrate and utilize all of its resource production procedures. Organizations need to apply for legal protection and patents for the components of structural capital, such as manufacturing processes, trade secrets, and business secrets. The core of structural capital is the common knowledge that is retained in the organization after an employee begins their tenure (Grasenick and Low, 2004; Roos et al., 1997). Ji et al. (2017) argued that structural capital positively affects innovation performance directly and indirectly (through intellectual capital). When examining the associations between structural capital and performance in the Mexican and Peruvian public administrations, Pedraza et al. (2022) found that structural capital is an intangible asset for public and private organizations because it positively and significantly affects organizational resources, capacities, and innovation performance. Therefore, organizations must establish their internal structural capital management strategies to improve innovation performance at the individual and organizational levels.

On this basis, structural capital is conducive to an enterprise’s innovation performance. We propose H2 as follows:

H2: Structural capital has a significant and positive influence on innovation performance

Relational capital refers to an organization’s establishment, maintenance, and development of relationships with its customers, suppliers, and partners (Molyneux, 1998). Bontis (1998) suggested that customer-based relationship capital represents the potential ability of an organization to own external intangible assets and is embedded within the organization’s external customer relationships. Tu (2009) demonstrated that relational capital positively influences knowledge integration, which in turn positively and significantly influences innovation performance. Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) contend that knowledge innovation stems from interpersonal interactions; exchanges between organizational members promote the creation of innovative knowledge and thereby trigger innovation performance. Onofrei et al. (2020) studied the influence of relational capital on innovation performance in supply chains using a sample of 557 manufacturing plants across 10 countries. The results showed that suppliers and customers who build strong relational capital effectively enhanced the company’s innovation performance, which is also the best way to maintain one’s competitive advantage in the global supply chain. Onofrei et al. (2020) found that relational capital positively affects innovation performance. Duan et al. (2023) suggested that relational capital positively affects innovation performance through trust, reciprocity, and transparency. We propose H3 as follows:

H3: Relational capital has a significant and positive influence on innovation performance

Calantonea et al. (2002) argued that when an organization creates an environment that is highly conducive to learning, its innovativeness and innovation performance can be improved through the active knowledge interaction processes. Lin (2007) revealed that an organization can further achieve innovation through knowledge sharing after it acquires the necessary information. Bavik et al. (2018) posited that through knowledge sharing, employees are provided the relevant information to help them achieve individual innovation. The results of the study by Perry-Smith and Shalley (2003) suggested that information exchange and knowledge sharing between team members are positively associated with innovation performance. Shi et al. (2022) investigated the effects of knowledge sharing, collaborative innovation, and building information modeling (BIM) application on innovation performance in the construction supply chain by creating and validating the rationality of a relationship model entailing all four factors. The relationships between the factors not only were useful for understanding the role of knowledge sharing in collaborative innovation in the construction supply chain but also had positive effects on developing BIM functions. Wang and Hu (2020) agreed that knowledge sharing positively influences innovation performance. Hanifah et al. (2022) highlighted that knowledge sharing has a significant impact on firm innovation performance. We propose H4 as follows:

H4: Knowledge sharing has a significant and positive influence on innovation performance

According to Tushman and O’Reilly (1996), an enterprise should foster an innovative organizational culture, as the values of cultural factors affect behavior, which in turn affects knowledge creation and sharing. McDermott and O’Dell (2001) examined organizational culture and knowledge sharing and found that the core values of an organization must be closely associated with knowledge sharing. An organization would create its own culture of knowledge sharing and convert it into a tangible asset alongside its business objectives. Svelby and Simons (2002) stressed that embodying organizational culture during its creation process is conducive to knowledge sharing. Caruso (2017) suggested that knowledge sharing is the sharing of information, techniques, and professionalism between organizational members; it is a valuable intangible asset and is affected by organizational culture. Earl and Scott (1999) showed that creating a culture that is conducive to the promotion of knowledge sharing within the organization improves knowledge acquisition skills at the individual and aggregate levels, thus significantly increasing knowledge value. Gooderham et al. (2022) used the ability, motivation, and opportunity (AMO) approach to examine how organizational culture and national culture affect knowledge sharing in multinational enterprises. The research encompassed 11 countries and regions in northern, central, and eastern Europe and southeast Asia. A questionnaire was administered to 11,484 people employed in 1235 departments. The results showed that organizational and natural cultures were both important factors for understanding knowledge sharing due to their positive influences. Knowledge sharing is conducive to understanding the intrinsic motivations of employees, and managers can broaden its range through organizational culture, thus promoting long-term organizational development. We propose H5 as follows:

H5: Organizational culture has a significant and positive influence on knowledge sharing

Joia (2000) pointed out that structural capital comprises the structure and strategies necessary for an organization to function, and its influence is realized through the organization’s internal operations. Bontis (1999) classified intellectual capital as human resource capital, structural capital, and relational capital, and investigated ways to associate between internal organizational knowledge and the external environment. Yli-Renko et al. (2001) suggested that individual members who hold advantageous positions in their organizations can help their organizations accumulate knowledge and assets through knowledge sharing. This imperceptibly improves the knowledge and competence of other employees and leaders, and their sharing behaviors become conducive to organizational growth. Kim and Shim (2018) found that the density of social capital, including structural capital, has a positive influence on knowledge sharing between small and medium enterprise employees. In a study on the influence of social capital on knowledge sharing in online user communities, Yan et al. (2019) highlighted a significant bidirectional relationship between social capital (structural, cognitive, and relational) and knowledge sharing, mainly manifested in the knowledge sharing behaviors of core participants in the community. Structural capital positively influences knowledge sharing through expansion and conversion. We propose H6 as follows:

H6: Structural capital has a significant and positive influence on knowledge sharing

McFadyen and Cannella (2004) pointed out that the strength of the relations in relational capital influences knowledge sharing and innovation. Hooff and Huysman (2009) revealed that relational capital positively influences knowledge sharing. Lai (2013) found that the stronger the relationships (the higher the relational capital), the more likely employees are to exhibit cooperative behaviors and promote knowledge sharing. Kim et al. (2013) demonstrated a strong association between relational social capital and knowledge sharing. Allameh (2018) described the three dimensions of social capital as structural, relational, and perceptional social capital, all of which positively affect knowledge sharing. Qiao and Wang (2021) opined that relational capital concurrently positively influences explicit knowledge sharing and tacit knowledge sharing. Hanifah et al. (2022) examined relational capital, knowledge sharing, and innovation performance in the Malaysian manufacturing sector. They identified internal and external relational capital as determinants of innovation performance against the backdrop of the competitiveness and survivalist challenges of the manufacturing sector. Knowledge sharing also mediated innovation performance, and relational capital positively influenced knowledge sharing. We propose H7 as follows:

H7: Relational capital has a significant and positive influence on knowledge sharing

Valle et al. (2000) argued that human resource training should be in line with corporate strategies in order to achieve optimal organizational performance. An enterprise that adopts innovative strategies and design training programs that correspond to these innovative strategies can enhance their innovation performance. Enterprises can improve employees’ knowledge, skills, and competence by managing specific human resources, thus improving their employees’ contributions to the organization and further enhancing innovation performance (Valle et al., 2000; Youndt and Snell, 2004). According to research, human resource management practices include providing authorization to employees, encouraging employee engagement, and enhancing organizational innovation (Garaus et al. 2016). Human resource management activities play a key role in improving market share, individual activeness, and service innovation (Anderson et al. 2014; Ardito and Messeni, 2017). Using a sample of 129 companies, Papa et al. (2020) examined the effects of knowledge acquisition, employee retention, and HRM practices on innovation performance. The results showed that companies are under immense pressure due to increasing innovation models and means of knowledge acquisition. Leaders who can promptly adapt to such external changes can consolidate the HRM practices of their company, thereby reducing employee turnover and promoting innovation performance. We propose H8 as follows:

H8: Human resource management practices have a significant and positive influence on innovation performance

To enhance employees’ knowledge, skills, and competence, enterprises can leverage the managerial strengths of specified human resources, thereby strengthening employees’ contributions to the organization and subsequently to organizational performance (Sanz-Valle et al., 1999; Youndt and Snell, 2004). Schneider and Reichers (1983) mentioned that positive interactions between organizational members create an environment conducive to information sharing within the organization. This environment allows high-performing employees to enhance their leadership skills, thus improving organizational performance through employees’ awareness of knowledge sharing. A team’s ability to showcase their performance or achieve knowledge sharing and innovation depends on the degree to which their organization’s human resource management effectively stimulates team operations (McHugh, 1997). Papa et al. (2020) demonstrated the positive effects of knowledge sharing on innovation performance, while HRM enhances the relationship between knowledge sharing and innovation performance. Regarding the positive effects of knowledge sharing on innovation performance, studies have also shown that the influence of knowledge sharing on innovation performance is moderated by the HRM practices adopted (Kim and Park, 2017; Jada Mukhopadhyay and Titiyal, 2019). Haq et al. (2021) examined the influence of HRM practices on knowledge sharing and innovation performance in 213 manufacturing plants in China. The results showed that HRM practices indeed influence knowledge sharing, and knowledge sharing directly influences innovation performance. Supplier knowledge sharing complements intra-organizational knowledge sharing, and HRM practices interfere with the relationship between knowledge sharing and innovation performance. We propose H9 as follows:

H9: The influence of knowledge sharing on innovation performance is moderated by HRM practices

Regarding mediation effects, we have proposed three hypotheses about knowledge sharing as a mediator variable. Firstly, we explained why knowledge sharing was assigned as a mediator variable, followed by proposing the three hypotheses. Bagherzadeh et al. (2019) examined the influence of outside-in open innovation (OI) on innovation performance while considering the mediating roles of knowledge sharing and innovation strategy. The results revealed that knowledge sharing and innovation strategy fully mediated the relationship between outside-in OI and innovation performance. Hanifah et al. (2022) studied the influences of intellectual capital and entrepreneurial orientation on innovation performance in SMEs, with knowledge sharing as a mediator. The results showed that human capital, as well as external relational capital, had a positive correlation with both knowledge sharing and innovation performance mediated by knowledge sharing. Hanifah et al. (2022) studied relational capital, knowledge sharing, and innovation performance in the Malaysian manufacturing sector. They showed that internal and external relational capital were determinants of innovation performance, while knowledge sharing mediated the influence of innovation performance, and relational capital positively influenced knowledge sharing.

The means of creating appropriate and effective organizational culture underpins organizational innovation. Research has demonstrated the positive and significant influence of organizational culture on organizational innovation and innovation performance (Daft, 2004; Lemon and Sahota, 2004). Shahzad et al. (2017) revealed that organizational innovation performance is supported and influenced by organizational culture. Sveiby and Simons (2002) stressed that realizing organizational culture while establishing it is conducive to knowledge sharing. Caruso (2017) agreed that organizational culture influences knowledge sharing. Bavik et al. (2018) suggested that employees can acquire the necessary knowledge through knowledge sharing and thus achieve personal innovation. Perry-Smith and Shalley (2003) revealed that information exchange and knowledge sharing between team members positively influence innovation performance. We propose H10 as follows:

H10: Knowledge sharing mediates the influence of organizational culture on innovation performance.

De Pablos (2004) demonstrated that good structural capital empowers organizational value. Lin et al. (2011) defined structural capital as the ability to resolve organizational problems and create value in the organization’s system and procedures as a whole, thus enhancing organizational competitiveness and firm innovation performance. Yli-Renko et al. (2001) contended that members who hold advantageous positions in the organization’s structural capital framework can contribute to its accumulation of knowledge assets by leveraging sharing environments where leaders and subordinates share knowledge and capabilities. Kim and Shim (2018) showed that the density of social capital, which includes structural capital, positively influenced knowledge sharing among SME employees. Lastly, knowledge sharing positively and significantly influenced innovation performance. We propose H11 as follows:

H11: Knowledge sharing mediates the influence of structural capital on innovation performance.

Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) suggested that interpersonal interactions and exchanges between organizational members generate innovative knowledge and subsequently promote innovation performance. Tu’s (2009) empirical results showed that relational capital positively influences knowledge integration abilities, which positively and significantly influences innovation performance. Moreover, the empirical study by Kim et al. (2013) demonstrated a strong link between relational social capital and knowledge donation. Allameh (2018) identified the structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions of social capital, all of which positively influence knowledge sharing. Lastly, knowledge sharing positively and significantly influences innovation performance. We propose H12 as follows:

H12: Knowledge sharing mediates the influence of relational capital on innovation performance.

Methods

Study framework

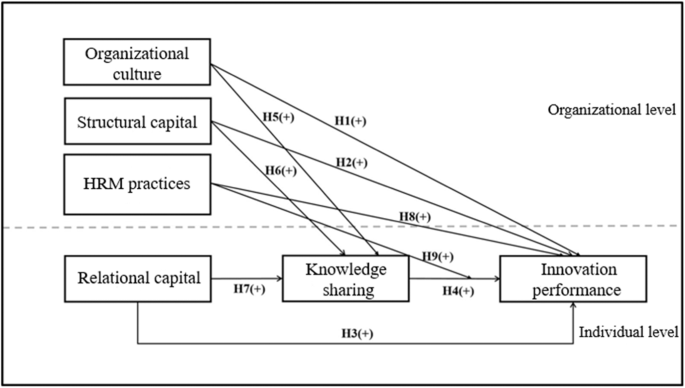

We designed a study framework consisting of a hierarchical linear model for analysis and estimation as shown in Fig. 1. The main reason for using hierarchical linear modeling is because traditional single-level regression analysis is prone to bias. Wen and Chiou (2009) pointed out that in the traditional approach, organizational level and individual level variables are placed into a single regression model, which likely violates the assumption of independence. The standard error of the estimated regression coefficient analyzed through traditional regression analysis is also excessively small and may reject the null hypothesis, resulting in type 1 error inflation. Therefore, hierarchical linear modeling was used for data analysis in this study with the goal of demonstrating the relationships between all the organizational level and individual level variables, as well as the interactions between different levels.

The empirical model

Analytical strategies and levels

In hierarchical linear mediation analyses, several configurations exist such as 1 → 1 → 1, 2 → 1 → 1, and 2 → 2 → 1 (Krull and MacKinnon, 1999). The mediating effect models in this study were the 1 → 1 → 1 and 2 → 1 → 1 configurations. These three numbers represent the independent variable, mediator variables, and outcome variables, respectively. The mediating effect models in this study were (1) organizational culture → knowledge sharing → innovation performance; (2) structural capital → knowledge sharing → innovation performance; and (3) relational capital → knowledge sharing → innovation performance.

Null model

In this study, the individual variables (innovation performance and knowledge sharing) were assigned as outcome variables. First, prior to conducting a hierarchical linear analysis, a null model must be used to check for significant differences in the individual innovation performance (PERFORMANCE) and knowledge sharing (KNOWLEDGE), as well as to estimate the amount of between-branch variance that constitutes the total variance in the individual innovation performance and knowledge sharing. The model settings are shown in Eqs. (1) to (2):

Level1

Level2

where PERFORMANCEij represents the individual innovation performance of the ith person in the jth branch; β0j represents the mean innovation performance of the jth branch; rij indicates the within-group error, with a mean of 0; the variance σ2 is independent, homogenous, and normally distributed; γ00 represents the total mean score of the individual innovation performance; uoj represents the difference in the mean individual innovation performance and the total mean score of the individual innovation performance of each branch; uoj is the between-group error, which is independent and has a mean of 0; τ00 is the variance and is independent, homogenous, and normally distributed; and rij and uoj are assumed to be independent of each other. We further examined the ICC of the null model (ICC = τ00/τ00 + σ2) to determine the necessity to perform HLM analysis. Heck and Thomas (2009) suggested that HLM can be used for estimation and analysis when the ICC is greater than or equal to 0.05. The same settings were applied to the knowledge sharing (KNOWLEDGE) null model, and shall not be elaborated on further.

Hierarchical linear mediation model

Based on the construction of the hierarchical linear mediation model, random effects were used to set the Level1 intercept. The mediation models were: (1) Organizational culture → knowledge sharing → innovation performance; (2) Structural capital → knowledge sharing → innovation performance; (3) Relational capital → knowledge sharing → innovation performance. Regarding mediation effect testing, the ordered regression coefficient test proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986) is a popular method. This study followed Baron and Kenny’s (1986) three-step test method in which the first step was to test the influence of the independent variables on the dependent variables, namely the influences of organizational culture (CULTURE), structural capital (STRUCTURE), and relational capital (RELATION) on innovation performance (PERFORMANCE), as shown in Eqs. (3) through (5). The second step was to test the influence of the independent variables on the mediator variables, namely the influences of organizational culture (CULTURE), structural capital (STRUCTURE), and relational capital (RELATION) on knowledge sharing (KNOWLEDGE). Lastly, the other variables were included in the model, and the influences of organizational culture (CULTURE), structural capital (STRUCTURE), HRM practices (RESOURCE), relational capital (RELATION), and knowledge sharing (KNOWLEDGE on innovation performance (PERFORMANCE) were estimated, as shown in Eqs. (9) to (12). Sex (SEX), job tenure (EXP), and business model (MANAGE) were set as control variables. The first step is as follows:

Level1

Level2

where β0j is the Level1 intercept; β1j~β3j represent the coefficients of the Level1 independent variables; γ00 is the total mean innovation performance; γ01 is the coefficient of organizational culture (CULTURE); γ02 is the coefficient of structural capital (STRUCTURE); μ0j is the between-group error, which is independent and has a mean of 0; and τ00 is the variance and is independent, homogenous, and normally distributed. Fixed effects were applied to Eq. (5), without a random error. The estimations for Eqs. (3) through (5) are presented in Model 1 in Table 3. If γ10, γ01, or γ02 was significant, then the second step was used for estimation.

Level1

Level2

The estimations for Eqs. (6) through (8) are presented in Model 2 in Table 3. If γ10, γ01, or γ02 was significant, then the third step was used for estimation.

Level1

Level2

The estimations for Eqs. (9) through (12) are presented in Model 3 in Table 3. If γ20 was not significant, then there were no mediation effects; if γ20 was significant alongside any of γ10, γ01, γ02, or γ03, then there were partial mediation effects; if γ20 was significant, but γ10, γ01, γ02, or γ03, were not, then there were complete mediation effects.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire in this study consisted of two sections. The first section covered the participants’ basic information, including sex, age, tenure in the real estate agency, and job position. The second section covered items related to the three organizational-level variables (organizational culture, structural capital, and HRM practices) and the three individual-level variables (structural capital, knowledge sharing, and innovation performance).

The items pertaining to organizational culture were designed according to the studies by Schein (1993), Wilkins and Ouchi (1983). Organizational culture consists of three sub-dimensions: artifacts, espoused values, and basic assumptions. According to Schein (1993), artifacts are all the concrete observations of a company, such as language, style, ceremonies, and office settings; espoused values are the common beliefs, ethics, and behavioral norms shared by the organization, which consist of organizational strategies, objectives, philosophies, and values; basic assumptions refer to the unconscious beliefs that organizational members hold and are the original source of values and organizational action that profoundly influence how organizational members perceive, think about, and interact with the world. Each sub-dimension consists of three items, for a total of nine items. Next, the items pertaining to structural capital were designed according to the studies by Edvinsson and Malone (1997) and Jaw (2004). Structural capital consists of three sub-dimensions: organizational capital, innovation capital, and process capital. Organizational capital refers to a company’s investments in systems and instruments that enhance the transfer of knowledge inside the organization as well as improve the means to supply and disseminate knowledge. This capital reflects an organization’s ability to systematize, synthesize, and arrange itself and the systems for enhancing production. Innovation capital refers to an organization’s capacity to innovate and protect trade rights, intellectual property, and other intangible assets and its ability to develop and expedite the launch of new products and services. Process capital includes work procedures, special methods, and employee programs for expanding or enhancing product manufacturing or service efficiency. The above sub-dimensions consist of three, three, and two items, respectively, for a total of eight items. The items pertaining to HRM practices were designed according to the studies by Bae et al. (1998), and Sun et al. (2007). HRM practices consist of human resource planning, training and development, and remuneration and benefits, and each sub-dimension includes two or three items, for a total of eight items. Finally, the items pertaining to relational capital were designed according to the studies by Sarkar et al. (2001). Relational capital consists of mutual trust, commitment, and information exchange, and each sub-dimension includes two or three items, for a total of eight items.

The items pertaining to knowledge sharing were designed according to the studies by Spencer (2003); Hendrinks (1999); Bock and Kim (2002); Bock et al. (2005); Betz (1987); Subramanian and Nilakanta (1996); Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal (2001); Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995). Knowledge sharing was divided into three sub-dimensions: knowledge sharer, knowledge recipient, and knowledge sharing intentions, each consisting of two or three items, for a total of eight items. The items pertaining to innovation performance were designed according to the studies by Amabile (1988); Drejer (2004); and Bilderbeek et al. (1998). Innovation performance consisted of stimulating innovation and service innovation, which included three and two items, respectively, for a total of five items. All items were measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). Please refer to Table 1 for the detailed questionnaire items.

Cronbach’s α is currently the most common method of measuring the reliability of each dimension. A Cronbach’s α of greater than 0.8 indicates high reliability (Hair et al., 2011), which was the case for all dimensions in this study. As a measure of construct validity, the factor loading of each item in this study was significant, thus validating the construct validity of the scale. We further performed measurements using convergent validity, which is based on the factor loading of each item in each dimension. According to Hair et al. (2006), a good convergent validity should be greater than 0.5, which was the case in our study.

Data collection, descriptive statistics, and data treatment

Data collection

Convenience sampling was adopted in this study to survey real estate agents from seven real estate agency chains in Kaohsiung City: Sinyi Realty, HandB Housing, Taiching Realty, Taiwan Realty, Yung Ching Realty, CTBC Real Estate, and U-Trust Realty. The surveyed area consisted of the commercial hubs of Sanmin, Zuoying, Lingya, Gushan, and Xinxing districts. The questionnaire was administered in person to the participants before mid-May 2021, and then via mail after mid-May 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic situation. The survey period lasted from May 1 to July 31, 2021. A total of 1130 questionnaires were distributed (530 in person, 600 via mail), and 444 were recovered (115 from Sanmin district, 104 from Zuoying district, 66 from Lingya district, 58 from Gushan district, and 101 from Xinxing district). 40 invalid questionnaires were removed for missing items or no response to sex and tenure. The Level 2 variables were in units of branches, and the variance data were the aggregate of the Level 1 individual data. To ensure representativeness, three questionnaires were removed because their branches had returned less than three responses. This left a total of 401 valid questionnaires, or an effective response rate of 35.49%.

Armstrong and Overton (1977) proposed the non-response bias test process for examining whether significant differences exist in the response rate in the options for sex, marital status, and education level, which was used in each of the two batches of recovered samples. The non-response bias reflects the consistency between the distribution of the actual recovered samples and the population data structure. We split the 401 recovered samples into two groups based on the code number; the first group consisted of 310 responses recovered in person, and the second consisted of 91 responses recovered via mail. We then tested the differences in the demographic backgrounds (sex, marital status, and education level) of the two groups, but found no significant differences. Thus, no serious non-response bias was found in the questionnaire.

Descriptive statistics

In the valid sample, men accounted for 53.9% (216 participants) of the responses while women accounted for 46.1% (185 participants) of the responses. The largest group of participants (29.5%, 116) were in the 30–40 years age group, followed by those in the 41–50 years age group (27.2%, 107). Regarding marital status, unmarried participants accounted for 47.9% (190) while married participants accounted for 47.6% (189) of the responses. Regarding tenure, the largest percentage of the participants had been working for between one and five years (42.1%, 169), followed by those working for less than a year (23.7%, 95). Regarding income, the largest percentage of participants (22.5%, 88) earned between NT$460,000–600,000, followed by those who earned less than NT$300,000 (18.9%, 74). Regarding job positions, the majority (82.3%, 326) of the participants were salespersons, while agents constituted 4.5% (18). Regarding education level, the majority of the participants had received university or two/four-year technical college educations (57.2%, 224), while those who received a senior (vocational) high school education or less made up 21.4% of participants (84). The majority (74.6%, 299) of the participants were working in franchise office branches, followed by those working in direct sales offices (25.4%, 102).

Data processing

Control variables

In a regression analysis, the influence of control variables such as sex, tenure, and business model must be considered. Gender differences reflect physiological differences and can affect which employees are assigned different work tasks, which may influence their innovation performance. Therefore, we used sex as a control variable in the regression model. Many companies nowadays desire to achieve higher innovation performance. Most employees with longer tenures are older and are less responsive toward accepting new things; on the other hand, employees with shorter tenures are mostly fresh graduates or younger employees with less work experience. They tend to be more enthusiastic about their jobs since they have just entered the workforce and are more likely to develop new ideas; therefore, they have better innovation performance than employees with longer tenures. For this reason, we used tenure as a control variable in the regression model. The real estate industry in Taiwan consists of direct sales and franchise stores. the former is directly operated by the headquarters of a real estate company, and the employed agents and salespersons are dispatched to these direct sales offices after receiving training at the headquarters. The headquarters is responsible for guaranteeing the resources and service contents at each branch office. On the other hand, franchise stores consist of independent branch offices that need to pay a regular franchise fee to the headquarters in exchange for resources such as the headquarters’ brand image, educational training, or advertising. Each franchise is equivalent to a standalone company that must bear its own losses, and its business system and service contents differ as well. Since the innovation performance of both business models may differ, we also used the business model as a control variable in the regression model.

Aggregation issues

In this study, organizational culture, structural capital, and HRM practices were assigned as Level 2 variables. The data was a shared construct since it was collected from each real estate agent. In addressing the treatment of shared construct data, Klein et al. (1994) indicated that prior to conducting a multi-level analysis, it is necessary to examine the appropriateness of consolidating individual variables to the aggregate level. We used the intraclass correlation test (ICC(1)) approach proposed by James (1982) and the reliability of the mean test (ICC(2)) approach proposed by Bliese (1998) to examine the between-group differences. An ICC(1) greater than 0.5 indicates aggregation within organizational members, and the mean is the score of the organizational variable (Bliese, 2000; Heck and Thomas, 2009); an ICC(2) greater than 0.7 indicates a high reliability for using the group mean of individual data as a contextual variable, and that significant differences exist between the mean of each group (Dixon and Cunningham, 2006). The formulas are shown below:

where MSb is the between-group difference, MSw is the within-group difference, Ng is the arithmetic mean of the group size.

There were 55 branches in Level 2, and the calculated ICC (1) of organizational culture and structural capital was 0.998 (>0.5), indicating that the individual variables of structural capital and organizational culture can be integrated into the aggregate level. The ICC (1)s of organizational culture and structural capital were both 0.999 (>0.07), which shows that the group means of individual organizational culture and structural capital are highly reliable contextual variable indicators with significant between-group heterogeneity. The ICC (2) of HRM practices was 0.999 (>0.07), which shows that HRM practices are a highly reliable contextual variable indicator with a significant between-group heterogeneity.

We recovered 401 questionnaires from 55 branches. We then used the within-group interrater reliability rwg (James et al., 1984, 1993) to determine the within-group agreement, which reflects the degree of agreement of an individual in a particular population toward a particular variable (Bliese, 2000). The within-group agreement is present when rwg,j exceeds 0.7 (James et al., 1984). The formula is as follows:

where J is the number of questionnaire items; rwg(j) is the within-group agreement coefficient for judges’ mean scores based on the jth item; \(sx_j^2\) is the mean of the observed variances on the jth item; and \(\sigma _E^2\) is the expected variance of a hypothesized null distribution.

The results showed that the mean rwg(j) of the 55 branches in relation to organizational culture, structural capital, and HRM practices was 0.973, 0.966, and 0.950, respectively, and all were larger than 0.7. This shows that the within-group agreements were present in the variables of organizational culture, structural capital, and HRM practices, and were strongly correlated. Thus, the organizational members were in agreement regarding organizational culture, structural capital, and HRM practices. Therefore, our consolidation of organizational culture, structural capital, and HRM practices as organizational-level variables was adequate.

Empirical results

Prior to HLM analysis, we needed to examine whether significant differences exist between the individual innovation performance and knowledge sharing between branches, and we also had to estimate the proportion by which the total variance of innovation performance and knowledge sharing is shaped through the differences between branches.

As shown in Table 2, the estimated variance of the random effects of personal innovation performance was 0.086 and was significant at the 1% level. This shows that significant differences exist in the individual innovation performance at each branch. The intraclass correlation was 0.208 (=0.086/(0.086 + 0.328)), which means that 20.8% of the variance of individual innovation performance consisted of the interclass (between branches) differences, while 79.2% of the variance consisted of intraclass (within a branch) differences. Next, the estimated variance of the random effects of knowledge sharing was 0.068 and was significant at the 1% level. This shows that significant differences exist in the levels of knowledge sharing at each branch. The intraclass correlation was 0.189 (=0.068/(0.068 + 0.292)), which means that 18.9% of the variance of knowledge sharing can be explained by the differences between branches, while 81.1% of the variance can be explained by the differences between agents. Therefore, we further applied HLM for analysis and estimation.

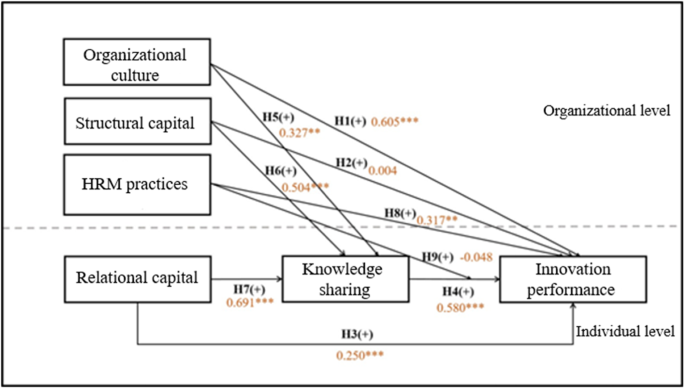

According to Table 3 and Fig. 2, the estimation results of Model 1 showed that the estimated coefficient of relational capital was 0.643 and was significant at the 1% level. The estimated coefficient of organizational culture was 0.556 and was significant at the 1% level. The estimated coefficient of structural capital was 0.381 and was significant at the 5% level. These results showed that the three-step mediation effects testing had passed the first step. The estimation results of Model 2 showed that the estimated coefficient of organizational culture was 0.327 and was significant at the 1% level. The empirical results support H5. The estimated coefficient of structural capital was 0.504 and was significant at the 1% level. The empirical results support H6. The empirical results support H7. These results indicated that the three-step mediation effects testing had passed the second step.

The estimation results of Model 3 showed that the estimated coefficient of knowledge sharing was 0.580 and was significant at a 1% level. The empirical results support H4. The estimated coefficient of organizational culture was 0.605 and was significant at a 1% level. The empirical results support H1. The results support H1, H4, and H5, as well as H10. The estimated coefficient of structural capital was 0.04 but did not attain a significant level. The empirical results do not support H2. Good structural capital creates organizational value (De Pablos, 2004). The empirical results support H2, H4, and H6, as well as H11. The estimated coefficient of relational capital was 0.250 and was significant at a 1% level. The empirical results support H3. The empirical results support H3, H4, and H7, as well as H12.

The estimated coefficient of HRM practices was 0.317 and was significant at a 5% level. The empirical results support H8. The estimated coefficient of the influence of knowledge sharing on innovation performance through the moderating variable of HRM practices was −0.048 and did not attain a significant level. This shows that HRM practices do not moderate the influence of knowledge sharing on innovation performance. The empirical results do not support H9.

Discussion

Theoretical implications

This showed that the stronger the real estate agents’ understanding of organizational culture, the better their understanding of knowledge sharing. The empirical results support H5 and validate Sveiby and Simons’ (2002) study, which showed that an organizational culture characterized by trust and cooperation increases knowledge sharing and innovation performance. In addition, the process of implementing organizational culture is conducive to the indication of intra-organizational knowledge sharing. This indicates that the real estate agents’ knowledge sharing is significantly influenced by their strong understanding of structural capital. The empirical results support H6. This finding also demonstrates that organizational members create partnerships rooted in mutual respect through long-term relationships or friendships, as well as that the trust-based structural capital shaped by this cooperative climate promotes organizational members’ willingness to share knowledge (Granovetter, 1992). This indicates that real estate agents with a stronger understanding of relational capital have a stronger understanding of knowledge sharing as well. The empirical results support H7. This finding supports Lai’s (2013) argument that the higher the relational capital, the more likely organizational members are to engage in cooperation and the more likely they are to share knowledge. A stronger and closer relational capital increases the depth, breadth, and efficiency of knowledge sharing (Lane and Lubatkin, 1998).

The empirical results support H4. This finding is in line with Lin’s (2007) demonstration of the relationship between knowledge sharing and innovation performance. The study revealed that knowledge sharing is essential for information acquisition and, subsequently, innovation. This further indicates that the stronger the real estate agents’ understanding of knowledge sharing, the better their innovation performance. Indeed, knowledge sharing has mediating effects. This indicates that real estate agents’ understanding of organizational culture significantly influences their innovation performance. The empirical results support H1. Huang (2018) showed that a good organizational culture is a determinant of innovation performance. The cultures shaped by an organization play an important role in their innovation performance; organizational culture has significant and direct effects on innovation performance. The results support H1, H4, and H5, as well as H10. Alavi and Leidner (2001) highlighted that organizational culture is an important factor affecting knowledge management and organizational learning, is a determinant of organizational value, and promotes knowledge sharing and innovation. Fernandez et al. (2011) revealed that organizational culture enhances service innovation through knowledge sharing between colleagues. The key to building a strong and proactive organizational culture lies within the knowledge sharing and knowledge management behaviors between colleagues. This increases the likelihood that an organization will create innovative strategies (Al-Refaie, 2015). Organizational culture indirectly influences innovation performance through knowledge sharing and has a partial mediating effect.

The empirical results do not support H2. Good structural capital creates organizational value (De Pablos, 2004). Employees with a poorer perception toward their organization’s structural capital are incapable of significantly increasing the innovation performance of the organization. Our results revealed that structural capital has no significant or direct influence on innovation performance. This reflects the reality of the real estate industry since all agents are constantly competing, whether or not they are in the same organization. Consequently, they remain passive or are not attracted to the internal culture and vision of their organization or developing new skills. Regarding the enhancement of their personal and professional skills, each company has its own regulations on employee training. Some large and renowned brands provide internal and external training programs to their employees gratis, whereas smaller and independent brands operate on an out-of-pocket policy. Under such circumstances, structural capital fails to ideally influence innovation performance. The empirical results support H4 and H6, as well as H11. De Pablos (2004) wrote that structural capital consolidates individual and group knowledge to generate organizational knowledge during the learning process. An employee who is more willing to share knowledge would gain a higher level of personal achievement. Our results showed that structural capital indirectly influences innovation performance through knowledge sharing, with complete mediation effects. This indicates that real estate agents with a stronger understanding of relational capital have a higher innovation performance. The empirical results support H3 and show that relational capital has a direct influence on innovation performance. The empirical results support H3, H4, and H7, as well as H12. Nahapiet and Hoshal (1998) suggested that relational capital promotes innovation in knowledge sharing through the exchange of intangible assets. Tu (2009) indicated that relational capital serves as a medium for knowledge flow; the knowledge advantage created through knowledge sharing and consolidation enhances the mutual trust, commitment, and bilateral communication between partners, thus increasing their innovation performance. Our results indicate that relational capital indirectly influences innovation performance through knowledge sharing, and the mediation effects were partial.

This suggests that real estate agents with a stronger understanding of HRM practices have a higher innovation performance. The empirical results support H8. Lazear (1996) pointed out that employees who express a higher interest in HRM practices and strategies understand more about their organization and innovation performance. The findings therefore suggest that the positive effects of employee recruitment, selection, training, human resource planning, remuneration scheme design, and employee engagement activities can improve an organization’s market performance, overall performance, and innovation (Hartog and Verburg, 2004; Andries and Czarnitzki, 2014). This shows that HRM practices do not moderate the influence of knowledge sharing on innovation performance. The empirical results do not support H9. Previous studies have shown that HRM practices promote knowledge sharing on innovation performance (Lazzarotti et al., 2015). Knowledge-sharing activities among employees must be modified through HRM approaches such as designing training programs, reward systems, work teams, etc., so as to increase the willingness of employees to share their knowledge and experiences with others and thereby influence the individual innovation behaviors of employees and improve their innovation performance and creativity (Cano and Cano, 2006). Since the real estate agents had a weak understanding of HRM practices. This is because, in reality, many real estate agents do not have a base salary and must depend on making successful transactions by communicating and coordinating with their clients. Therefore, they tend to neglect the HRM practices in their organization. Our empirical results fail to support the aforementioned arguments.

Managerial implications

Our empirical results demonstrated that the indirect influence of organizational culture on innovation performance was partially mediated by knowledge sharing, the indirect influence of structural capital on innovation performance was fully mediated by knowledge sharing, and the indirect influence of relational capital on innovation performance was partially mediated by knowledge sharing. Real estate agents with a more positive perception of HRM practices showed better innovation performance.

First, managers should actively foster an organizational culture to enhance employees’ innovation performance. Measures include encouraging harmonious and friendly interactions between colleagues, creating a productive workplace climate, ensuring fair and equal treatment of all employees, emphasizing interpersonal relations, and establishing robust and comprehensive company policies.

Next, employees’ innovation performance can be enhanced by accumulating structural capital, such as allocating adequate funds and time to encourage employees to acquire new knowledge, establishing all-inclusive HR training programs, using various approaches to help employees develop their innovative capacity, and providing high-quality services that meet customer demands.

Employees can also improve their innovation performance by accumulating structural capital, such as establishing mutual trust between colleagues, treating one another with integrity, sharing knowledge, communicating frequently, and exchanging informal and formal information.

Lastly, HRM practices can be used to improve employees’ innovation performance. This includes setting well-defined career paths in the organization, assisting employees in applying their training contents into practice, giving compensation based on an employee’s contributions, and emphasizing impartiality.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study applied hierarchical linear modeling to explore the influences of organizational culture, structural capital, human resource management practices, relational capital, and knowledge sharing on the innovation performance of real estate agents. Organizational culture, structural capital, and human resource management practices were assigned as organizational-level variables while relational capital, knowledge sharing, and innovation performance were assigned as individual-level variables. First, we studied the influences of organizational culture, structural capital, and relational capital on innovation performance; afterward, we used knowledge sharing as a mediator variable to examine how it is influenced by organizational culture, structural capital, and relational capital. Lastly, we explored the influences of organizational culture, structural capital, human resource management practices, relational capital, and knowledge sharing on innovation performance, as well as whether human resource management practices moderated the influence of knowledge sharing on innovation performance. After testing the null model of the hierarchical linear model, we found that innovation performance and knowledge sharing differed significantly across the office branches, indicating that hierarchical linear modeling was suitable for analysis.

Based on the empirical results, organizational culture indirectly influences innovation performance through knowledge sharing. In other words, organizational culture has a partial mediating effect on innovation performance. Structural capital directly influences innovation performance through knowledge sharing, with a complete mediating effect. Relational capital indirectly influences innovation performance through knowledge sharing, with a partial mediating effect. The stronger the real estate agents’ understanding of human resource management practices, the higher their innovation performance. Human resource management practices did not moderate the influence of knowledge sharing on innovation performance, and our empirical results were not supported. From a theoretical perspective, the impacts of organizational culture in higher education on job satisfaction have been studied previously (see Islamy et al.,, 2020), although the model merely consisted of organizational culture, job satisfaction, and knowledge sharing. Moreover, Kutieshat and Farmanesh (2022) only considered the exogenous variable of new HRM practices when studying innovation performance. Our study expands and enhances the completeness of this theoretical framework by adding the variables of structural capital and relational capital, thus achieving better empirical support. Concerning the research subjects, studies on innovation in the real estate industry (see Benefield et al., 2019) have mostly observed the effects of real estate agencies and technology based on housing prices. On the other hand, our study employed latent variables and performed measurements from a psychological level, thereby broadening the research on the real estate industry.

This study was administered to participants in Kaohsiung City, Taiwan; therefore, the results cannot be extrapolated beyond the range of the study area. The control variables in the hierarchical linear model only included sex, tenure, and business model; job position was excluded, and the questionnaire was not directed at supervisors. Therefore, we were unable to explore whether job positions or supervisors’ opinions toward the organization or individual employees differed. Furthermore, we only focused on the human resource planning, training and development, and remuneration and benefits sub-dimensions of human resource management practices. We recommend future studies to explore the other sub-dimensions of human resource management practices, such as performance evaluation and non-financial remuneration schemes. Due to manuscript length restrictions and time and monetary constraints, we did not examine the behaviors of house buyers. As a result of technological advancements and social developments, our lifestyles and behaviors are profoundly influenced by science and technology, which may also alter the preferences of house buyers. Therefore, we suggest that future studies can focus on the impacts of technology (such as AI) on house-buyers’ behaviors or how AI moderates the relationship between knowledge sharing and innovation performance.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aboramadan M, Albashiti B, Alharazin H, Zaidoune S (2020) Organizational culture, innovation and performance: a study from a non-western context. J Manag Dev 39(4):437–451

Alavi M, Leidner DE (2001) Review: knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Q 25(1):107–136

Allameh SM (2018) Antecedents and consequences of intellectual capital: the role of social capital, knowledge sharing and innovation. J Intellect Cap 19(5):858–874

Al-Refaie A (2015) Effects of human resource management on hotel performance using structural equation modeling. Compute Hum Behav 43:293–303

Amabile TM (1988) A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Res Organ Behav 10(1):123–167

Anderson N, Potočnik P, Zhou J (2014) Innovation and creativity in organizations: a state-of-the-science review. J Manag Stud 40(5):1297–1333

Andries P, Czarnitzki D (2014) Small firm innovation performance and employee involvement. Small Bus Econ 43(1):21–38

Ardito L, Messeni PA (2017) Breadth of external knowledge sourcing and product innovation: the moderating role of strategic human resource practices. Eur Manag J 35(2):261–272

Armstrong JS, Overton TS (1977) Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J Market Res 14:396–402

Bae J, Chen SJ, Lawler JJ (1998) Variations in human resource management in Asian countries: MNC home-country and host-country effect. Int J Hum Resour Manag 9(4):653–669

Bagherzadeh M, Markovic S, Cheng J, Vanhaverbeke W (2019) How does outside-in open innovation influence innovation performance? Analyzing the mediating roles of knowledge sharing and innovation strategy. IEEE Trans Eng Manag 67(3):740–753

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical consideration. J Pers Soc Psychol 51:1173–1182

Bavik YL, Tang PM, Shao R, Lam LW (2018) Ethical leadership and employee knowledge sharing: Exploring dual-mediation paths. The Leadership Q 29(2): 322–332

Becerra-Fernandez I, Sabherwal R (2001) Organizational knowledge management: a contingency Perspective. J Manag Inf Syst 18(1):23–56

Benefield JD, Sirmans CS, Sirmans GS (2019) Observable agent effort and limits to innovation in residential real estate. J Real Estate Res 41(1):1–36

Betz F (1987) Managing technology-competing through new ventures-innovation and corporate research: Prentice Hall

Bilderbeek R, den Hertog P, Marklund G, Miles I (1998) Services in innovation: Knowledge Intensive Business Services (KBIS) as co-producers of innovation, Sl4S Synthesis Paper no. 3, STEP Group

Bitner MJ, Booms BH, Mohr LA (1994) Critical service encounters: the employee’s viewpoint. J Market 54:71–84

Bliese PD (1998) Group size, ICC values, and group-level correlations: a simulation. Organ Res Method 1(4):355–373

Bliese PD (2000) Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: implications for data aggregation and analysis. In: Klein KJ, Kozlowski SW (eds). Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations. Jossey-Bass, Inc., San Francisco, CA, pp. 349–381

Bock GW, Kim YG (2002) Breaking the myths of rewards: an exploratory study of attitudes about knowledge sharing. Inf Resour Manag J 15(2):14–21

Bock GW, Zmud RW, Kim YG, Lee JN (2005) Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Q Inf Technol Knowl Manag 29:87–111

Bontis N (1998) Intellectual capital: an exploratory study that develops measures and models. Manag Decis 36(2):63–76

Bontis N (1999) Managing organizational knowledge by diagnosing intellectual capital: framing and advancing the state of the field. Int J Technol Manag 18(5-8):433–463

Bontis N, Keow WCC, Richardson S (2000) Intellectual capital and business performance in Malaysian industries. J IntellectCap 1(1):85–100

Bowen DE, Schneider B (1985) Boundary-spanning-role employees and the service encounter: some guidelines for future management and research. In: Czepiel John, Solomon MichaelR, Surprenant CarolF (eds.) The service encounter. Lexington Books, New York, pp. 127–147

Bradler C, Neckermann S, Warnke AJ (2019) Incentivizing creativity: a large-scale experiment with performance bonuses and gifts. J Labor Econ 37(3):793–851

Cabrera EF, Cabrera A (2005) Fostering knowledge sharing through people management practices. Int J Hum Resour Manag 16:720–735

Calantonea RJ, Cavusgil ST, Zhao Y (2002) Learning orientation, firm innovation capability, and firm performance. Ind Market Manag 31(6):515–524

Cano CP, Cano PQ (2006) Human resources management and its impaction innovation performance in companies. Int J Technol Manag 35(1-4):11–28

Caruso SJ (2017) A foundation for understanding knowledge sharing: organizational culture, informal workplace learning, performance support, and knowledge management. Contemp Issue Educ Res 10(1):45–52

Chang TY, Lee CC, Lin HC (2023) A study on the influence of experiential marketing on repurchase intention of O2O operation model-with consumer decision -making as mediating. Manag Inf Comput 12(1):37–48

Chen TH, Chen HF (2022) Turning old to enable new: a case study on knowledge sharing of reverse mentoring for organizational innovation. Sun Yat-sen Manag Rev 30(2):325–366

Chen YH (2007) The strategy of value innovation of intellectual capital. J China Inst Technol 37:159–171

Daft RL (2004) Organization theory and design, 8th edn. Thomson/South-Western, Mason, Ohio

De Pablos PO (2004) Measuring and reporting structural capital: lessons form European learning firms. J Intellect Cap 5(4):629–647

Deal TE, Kennedy AA (1984) Corporate cultures. Common Wealth Publishing, NY

Dessler G (2000) Human resource management. Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, N. J

Dixon MA, Cunningham GB (2006) Data aggregation in multilevel analysis: a review of conceptual and statistical issues. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci 10(2):85–107

Drejer I (2004) Identifying innovation in surveys of services: a Schumpeterian perspective. Res Policy 33(3):551–562

Duan Y, Chen Y, Liu S, Wong CS, Yang M, Mu C (2023) The moderating effect of leadership empowerment on relational capital and firms’ innovation performance in the entrepreneurial ecosystem: evidence from China. J Intellect Cap 24(1):306–336

Earl lJ, Scott IA (1999) Opinion: what is a chief knowledge officer? I Sloan Manag Rev 40(2): 29–38

Edvinsson L, Malone MS (1997) Intellectual capital: realizing your company’s true value by finding its hidden roots. Harper Collins Publishers, Inc, New York

Evans WR, Davis WD (2005) High-performance work systems and organizational performance: the mediating role of internal social structure. J Manag 3:758–755

Fernández JE, Torres-Ruiz JM, Diaz-Espejo A, Montero A, Álvarez R, Jiménez MD, Cuervab MV Cuevas J (2011) Use of maximum trunk diameter measurements to detect water stress in mature ‘Arbequina’ olive trees under deficit irrigation. Agric Water Manag 98(12):1813–1821

Garaus C, Güttel WH, Konlechner S, Koprax I, Lackner H, Link K, Müller B (2016) Bridging knowledge in ambidextrous HRM systems: empirical evidence from hidden champions. Int J Hum Resour Manag 27(3):355–381

Geiger RS (2017) Beyond opening up the black box: investigating the role of algorithmic systems in Wikipedian organizational culture. Big Data Soc 4(2):2053951717730735

Gooderham PN, Pedersen T, Sandvik AM, Dasí À, Elter F, Hildrum J (2022) Contextualizing AMO explanations of knowledge sharing in MNEs: the role of organizational and national culture. Manag Int Rev 62:859–884

Granovetter MS (1992) Problems of explanation in economic sociology. In: Nohria N, Eccles R (eds.) Networks and organizations: structure, form and action. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, pp. 25–56

Grasenick K, Low J (2004) Shaken, not stirred: defining and connecting indicators for the measurement and valuation of intangibles. J Intellect Cap 5(2):268–281

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL (2006) Multivariate data analysis, 6th edn. Pearson University Press, Upper Saddle River, NJ

Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2011) PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J Market Theor Pract 19(2):139–152

Hameed WU, Nisar QA, Wu HC (2021) Relationships between external knowledge, internal innovation, firms’ open innovation performance, service innovation and business performance in the pakistani hotel industry. Int J Hosp Manag 92:102745

Hanifah H, Abd Halim N, Vafaei-Zadeh A, Nawaser K (2022) Effect of intellectual capital and entrepreneurial orientation on innovation performance of manufacturing SMEs: mediating role of knowledge sharing. J Intellect Cap 23(6):1175–1198