Abstract

Family is an important system that influences children’s social adjustment. Parents are an important member of the family system, and their parental child-rearing gender-role attitudes (PCGA) will have a significant impact on their children’s social adjustment. This study used a sampling method to compare the intergenerational differences between family members’ PCGA, identity with parents and social adjustment in single- and two-parent families through 931 single-parent families and 3732 two-parent families in Suzhou, China. The study explored the mediating role of children’s identity with parents on parents’ PCGA and children’s social adjustment in different family structures. The results showed that: (1) parents’ masculinity rearing, femininity rearing of PCGA and children’s social adjustment in two-parent families were significantly higher than those in single-parent families; (2) children’s identity with parents mediated the relationship between femininity rearing of parents’ PCGA and children’s social adjustment; (3) the mediated model of children’s identity with parents was found to be significantly different between single-parent and two-parent families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With rapid social and economic development, changes in the concept of marriage have occurred, leading to changes in the family structure (Nahkur and Kutsar, 2022). The family is the proximal microsystem that affects children’s physical and mental health, personality psychology, education acquisition, and other development indicators (Bronfenbrenner, 1986). Hence family structure, as the most important part of family influence, its changes will significantly affect children’s development, including the self-concept (Dijk et al., 2020), physical and mental health (Jasmin et al., 2017), social adjustment (Usoroh et al., 2014), etc. Among these factors, social adjustment is one of the criteria for evaluating individual mental health, and it is crucial for children’s development (Zhang et al., 2021). Compared with children in two-parent families, some studies have found that single-parent children may have difficulties in interpersonal interaction (Lee, 2019), learning (Xie, 2021), and emotional regulation (Bzostek and Berger, 2017). This may lead to low self-esteem and related issues (Kiraz and Ersoy, 2018), which directly and indirectly contribute to poor social adjustment.

Social adjustment means that individuals actively adapt to their constantly changing environment with some ease and learn to choose and avoid certain behaviors in daily activities, studies, and interpersonal communication, can control and change the environment, and have age-appropriate behavioral abilities (Mahoney and Bergman, 2002; Nie, 2005). Social adjustment includes interpersonal relationships, academic achievements, life skills, and mental resources (Yang and Jin, 2007). As parents are critical role models in the development of their children’s social adjustment (Park and Lee, 2020), and parenting style is a key factor affecting the development of children’s social adjustment (Masud et al., 2015). Poor social adjustment is related to the negative parenting styles (Zuilkowski et al., 2019). If parents lack understanding and love for their children, display obvious punishment behaviors, reject, and deny their children, then these children are more likely to exhibit problem behaviors (Lansford et al., 2004). Parents tend to adopt a negative parenting attitude when it comes to disciplining sons, in contrast to the gentler disciplinary regime they put in place to deal with daughters (Xie et al., 2004). This gender-differentiated parenting attitude is known as Parental Child-rearing Gender-role Attitudes (PCGA), which are an important aspect of parenting style and affect the social adjustment of children (Hastings et al., 2007; Zhang and Gao, 2015). For example, as previous studies have found, parents with traditional attitudes spend more time playing with gender-typed toys than with cross-gender toys (Wood et al., 2002). In addition, the way parents play with their children extends to the way children play with their peers, and stereotyped playstyles affect children’s interpersonal interactions (Hjelmér, 2020; Kingsbury and Coplan, 2012). Similarly, parents with enlightened attitudes focus on cultivating their children’s awareness of gender equality (Wang et al., 2013), which is helpful for children’s self-exploration and sound personality formation and social adjustment (Chen et al., 2016). Therefore, it can be concluded that parents with different PCGA will affect children’s social adjustment in different ways.

An individual’s social adjustment is not only affected by parental factors but also by cognition factors (McCauley et al., 2011; Zou et al., 2015). In the process of family rearing, the interaction between parents and children can be explained by reference to symbols. People interact through various symbols, both to understand the behavior of others and to assess the impact of their behavior on others (Mead, 1967). Firstly, parents raise and understand their children through language, action, and other factors. Then, after the symbols conveyed by parents are recognized by their children, the latter interact with the former by making symbols of approval or disapproval. Finally, parents and children adjust their behaviors through this process of symbolic interaction. For example, when parents adopt the traditional attitude, they may educate boys using strict disciplinary measures. But individual children can choose to accept or refuse strict discipline from their parents. In short, parents transmit symbols to their children through their PCGA, and children respond to their parents and interact with each other through their identities with their parents. Parents view their children’s socialization as part of their parenting responsibilities. Out of altruistic motives, they try to instill values and attitudes in their children that they believe will improve their children’s lives (Dhar et al., 2019; Doepke and Zilibotti, 2014), and children learn by observing their parents’ behaviors. However, children subjectively interpret the information from their parents and react with approval or disapproval. In the process of interacting with their parents, children learn behaviors that are deemed socially acceptable, thus creating a common context definition as they develop their own socialization (Tang, 2016). Likewise, parents’ cognitions of gender traits are also intergenerationally transmitted through their children’s subjective perceptions and internalization in daily interactions (Alesina et al., 2013), and children demonstrate their full awareness of gender roles through the process of social integration, leading to good social adjustment. Thus, children’s identity with parents may play a mediating role between parental child-rearing gender-role attitude and social adjustment.

The impact of PCGA on social adjustment

Social adjustment is a key indicator for assessing an individual’s socialization and plays a key role in the development of children (Maccoby, 2015; Liang et al., 2022). Gender role socialization is an important part of individual socialization, referring to the process of learning social culture to ensure that one’s gender behavior conforms to social norms (Du and Feng, 2000). The family is the most important arena for the raising of children in the process of gender role socialization (Endendijk et al., 2018). Ecological systems theory states that the family is the microsystem that affects children’s personality psychology, physical and mental health, sex roles, etc. (Bronfenbrenner, 1986). Parents are the main factor in socialization and from birth assume legal responsibility for teaching their children about gender-appropriate behavior and instructing them on the culture and social expectations of gender-typed activities. In this way, their parenting lays the foundation for their children’s future adaptation to the social environment (Busygina et al., 2019).

Parental child-rearing gender-role attitude is one aspect of parenting attitudes, referring to parents’ inherent attitudes and opinions on boys’ and girls’ choices of games and toys, as well as whether their behaviors in future occupations are consistent with their gender roles (Kollmayer et al., 2018). Put simply, parents educate their children through their PCGA, which includes personality perception and expectation, behavior discipline, housework division, leisure activities, material environment, career development, and values (Chen et al., 2018). Parents with more rigid gender attitudes habitually buy toys for boys that are more operable and tend to be social, such as cars and transformers; for girls, they buy toys that can be single-use and family-oriented toys such as dolls and tableware. This difference in the use of toys is likely to affect children’s activities when they grow up (Francis, 2010; Brito et al., 2021). There are similar phenomena in games. For example, parents always arrange for girls to play obedient roles such as nurses, mothers, and secretaries, while boys are arranged to play more independent and dominant roles that also enjoy higher social status, such as policemen and cadres. Children exposed to certain PCGA may reduce women’s motivation to achieve and thus influence their career choices (Fulcher et al., 2008; Yang and Gao, 2021).

The process of gender role socialization is also influenced by family structures (Mandara et al., 2005). And changes in family structure have a certain impact on family members, including parents (Baldridge, 2011). In different family structures, each family member has own unique function. Irrespective of whether the loss of a father or mother in the family is equivalent to losing the nurturing function, which includes financial support, time companionship, role models, etc. (Han and Wei, 2004). It has been found that the parent in a single-parent family may adopt more negative PCGA toward their children compared to a traditional family with two parents. This may contribute to the children being more likely to develop character defects such as pessimism, indifference, isolation, strong aggression, and emotional reactions such as anxiety, nervousness, restlessness, and irritability (Bzostek and Berger, 2017; Lee and McLanahan, 2015). Furthermore, children in single-parent families may have problems with their gender role identity due to the lack of exposure to dual-parent roles. This may make the children lose the reference standard for dealing with gender relationships later in life, which could weaken his or her interpersonal abilities (Dai, 2019). Another study found that children of absent fathers exhibit poorer development in terms of same-gender and opposite-gender traits than children of intact families. Such differences may lead to higher levels of anti-social behavior (Kim and Glassgow, 2018). It is evident that changes in family structure can influence PCGA, and different attitudes can alter children’s social adjustment.

The relationship between PCGA and social adjustment may also be influenced by other factors, such as individual factors. The process of gender socialization is a dynamic process, which is the result of children’s active attempts to adapt their cognition and behavior to their gender (Sowislo and Orth, 2013). Whether PCGA will directly lead to changes in children’s behavior may thus be conditioned by the children’s own actions and ideas. Therefore, this dynamic effect of identity may play an intermediary role in parental child-rearing gender-role attitude and children’s social adjustment.

The mediating role of children’s identity with parents

As a concept from social psychology, identity refers to the psychological process of recognizing and imitating the attitudes and behaviors of other individuals or groups and making them a part of one’s own personality. Social identity, as such, is a guide for us to conceptualize and evaluate ourselves (Baron and Byrne, 2003). Identity with parents refers to whether children are truly able to understand and accept their parents’ values and behaviors (Liu et al., 2011). Darling and Steinberg (1993) model of intergenerational integration suggests that parenting affects children’s socialization development. Child’s openness to parental values means that children’s identity with parents, and it moderates the influence of parenting practice on the children’s development. As a key aspect of parenting, PCGA has an important impact on children’s socialization development. Therefore, children identifying with parents may play a role in the relationship between PCGA and children’s social adjustment.

Children’s attitudes to parents may be influenced by their parents’ attitudes, a phenomenon explained by the theory of intergenerational transmission (Bugental and Grusec, 2006; Farré and Vella, 2013). Bisin and Verdier (2000) thought that the intergenerational transmission of attitudes occurred through the process of “direct vertical” socialization. In order to realize a strong intergenerational correlation between parents’ attitudes and children’s attitudes, parents put in the effort to pass on their attitudes to their children. The actual depth of this transmission will depend on the attitude of the children to their parents. Parental child-rearing gender-role attitude, as parental attitudes to social and cultural values, establish emotional interaction between parents and children. According to the quality of this interaction, children will either selectively take in or resist the transmission of their parents’ attitudes (Huang, 2008; Wang et al., 2019). For example, parent-child interaction is more harmonious under the enlightened PCGA (Perales et al., 2018; Raley and Bianchi, 2006), so children’s identity with their parents is also higher. Thus, parents’ PCGA may affect children’s identity with them.

Identity with parents is an indication of children’s own attitudes. Different people have different views on their PCGA, and the resulting behaviors are commensurately different (Ajzen and Fishbein, 2005). Fazio (1986) thought that attitude strength determines whether it is activated, and if it is activated, it forms an internal driving force that eventually leads to a corresponding behavior. Similarly, children’s identity with parents is an embodiment of the intensity with which those attitudes are held, and a higher identity with parents will have a positive impact on the child. For example, the higher the children’s identity with their parents, the higher life satisfaction will be (Hu, 2014). This positive influence may be because the high identity reflects a positive interaction between the children and the parents, while intimate interaction will affect the development of the children’s social adjustment (Eirini et al., 2014; Krikken et al., 2012). Children who grow up in negative/conflict-ridden parent-child relationships identify less with their parents and show more destructive, aggressive behaviors (Schneider et al., 2001). Although identity is a recessive cognitive change, it is an important factor affecting children’s social adjustment in intergenerational transmission. Therefore, this study will explore the mediating role of children’s identity with parents between parents’ PCGA and children’s social adjustment.

The current study

Although the importance of social adjustment for children’s development has been well documented, the effects of PCGA and intergenerational identity on social adjustment have rarely been studied, and the differences in social adjustment across family structures have also received scant attention in the literature. This study thus builds on existing research by exploring the children and parents of different family structures (single and two parents) to test whether the effects of PCGA on children’s social adjustment differ across family structures. Therefore, the hypotheses of this study were:

H1: There were differences in intergenerational PCGA, identity with parents, and social adjustment between single- and two-parent families.

H2: Children’s identity with parents plays a mediating role in parents’ PCGA and children’s social adjustment.

H3: The mediating role model of children’s identity with parents differs in single- and two-parent families.

Method

Participants

This study used a convenience sampling method and distributed questionnaires of children and their parents to 20 middle schools in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, China.

Suzhou City is an economically developed area, the permanent resident population was 12.8478 million people, with an annual GDP of $3179.7 billion, ranking 6th in the country (Suzhou City Bureau of Statistics, 2022). The survey distributed 5335 questionnaires and collected 4951 questionnaires, with a return rate of 92.80%. After eliminating 288 invalid questionnaires, 4663 questionnaires were finally collected and analyzed, with an effective sample recovery rate of 94.18%.

Among them, 931 (20%) were single-parent families and 3732 (80%) were two-parent families. ‘Single-parent families’ in the study refer to families in which only one parent is involved daily in the raising of children (Li, 2021). The children were aged 14–18 years (M = 14.76; SD = 2.37), with 2278 (48.9%) males and 2385 (51.1%) females. In heads of household, 47.3% (n = 2205) were fathers and 52.7% (n = 2458) were mothers. And 63.6% (n = 592) were headed by fathers and 36.4% (n = 339) by mothers in single-parent households; 43.2% (n = 1613) were headed by fathers and 56.8% (n = 2119) by mothers in two-parent households. The educational level of the parents was 6.7% (n = 314) had below junior high school, 45.8% (n = 2135) had completed junior high school, 30.8% (n = 1437) had finished high school, and 16.7% (n = 777) had finished college or higher. In terms of the monthly family income, 44% reported $687−$1373 (n = 2052), 27.8% reported <$687 (n = 1294), 18.2% reported $1374−$2061 (n = 848), and 10% reported over $2061 (n = 469).

Procedure

This study was permitted by the Ethics Committee of Soochow University. The researchers received permission from the head teacher of the schools, and signed informed consent was obtained from the participants (the students and their parents). The participants were informed about the study’s procedure and aims before the data was collected. The parents were given the opportunity to provide ‘opt-out’ consent for their children’s participation. The scales include a children’s scale and a parent’s scale. The children’s scale was arranged by the head teacher to be completed and collected in the classroom, while the parent’s scale was placed by students in envelopes to be completed by the main caregiver. Then, the students handed the questionnaires to their head teachers for collection within a week. After all the questionnaires were handed in, the researchers matched the children’s scale with the parent’s scale and deleted any unmatched or invalid data (for example, where the unanswered part exceeded 20%, the demographic information was not filled in or filled in incorrectly, or the responses to the scales showed a certain regularity, etc.).

Measures

Parental child-rearing gender-role attitude

We used the parental child-rearing gender-role attitude (PCGA) Scale devised by Chen et al. (2018) to assess the attitudes of grandparents and parents. The parents reported the PCGA of the grandparents and the children reported the PCGA of the parents. The scale consists of two parts: male parenting and female parenting, with 39 items in total across seven dimensions: personality perceptions and expectations (5 items), behavioral discipline (8 items), housework division (6 items.), leisure activities (3 items.), physical environment (5 items), career development (5 items), and value transmission (7 items). A 5-point Likert scale was used, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate a more equal PCGA, and lower scores indicate a more stereotypical PCGA. In the current study, the Cronbach α coefficient for the scale was 0.93. Cronbach’s α for the male and female parenting subscales were 0.85 and 0.88.

Social adjustment

The social adjustment scale was developed by Chen et al. (2016) based on Yang and Jin’s (2007) research. This scale was completed by parents and children to measure their social adjustment. The scale also uses Likert 5-point scoring, ranging from “1 (never) to 5 (always)”. There are 33 items in total, including 4 dimensions: interpersonal relationships, academic achievement, life skills, and mental resources. The average scores of all items were calculated. A higher score indicates better social adjustment. The scale has good reliability. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.97. The Cronbach’s alphas for each dimension of the scale were 0.94 (interpersonal relationship), 0.93 (academic achievement), 0.86 (life skills), and 0.91 (mental resources).

Identity with parents

Identity with parents in this study mainly measured children’s identity to their parents’ parental child-rearing gender-role attitude. It was measured by The parental child-rearing gender-role scale devised by Chen et al. (2018). The scale was completed by both parents and children. It has 39 items, scored on a 2-point Likert scale (0 = disagreement; 1 = agreement). In order to explore the differences among the three generations’ family members, we collected data related to parents’ identity with grandparents and children’s identity with parents. Parents’ identity with grandparents was filled by the parents and refers to the parents’ identity of PCGA to their grandparents. And children’s identity with parents was filled by the children and refers to the children’s identity of PCGA to their parents. The average score of all the items on the scale represents the degree of identification from 0 to 1. A higher score on the scale represents a stronger identity with parents.

Data analysis

The data for this study were collected using self-reported methods, which may be subject to the problem of common method bias. The Harman single-factor test was used for the common method bias test (Zhou and Long, 2004). The result showed that 10 factors with a latent root over one were obtained through factor analysis. The first factor explained 22.56% of the variation, which was much less than the critical value of 40%. Therefore, there was no serious common method bias in this study.

This study used SPSS 25.0 to conduct descriptive statistics, difference tests, and correlation analyses. Descriptive statistics and analysis of variance were conducted using an independent sample t-test to analyze PCGA, identity with parents, and social adjustment in single- and two-parent families (H1). And then the correlations between the variables were explored through correlation analysis.

We applied AMOS 23.0 to further test the mediating role of children’s identity with parents (H2) and its variability between single- and two-parent families (H3). This procedure was divided into two steps. In the first step, a mediation model was constructed to examine the potential mediating role of children’s identity with parents. In the second step, a multi-group analysis was conducted to examine the potential differences between single- and two-parent families. The model fit was evaluated using several fit indices, including the Chi-square statistic, a comparative fit index (CFI), a Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and a root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA). The acceptable model fit was defined thus: CFI, TLI ≥ 0.90, and RMSEA ≤ 0.08 (Kline, 2011).

Results

Descriptive statistics

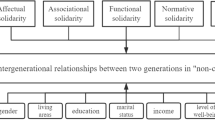

To investigate the intergenerational differences in PCGA, identity with parents, and social adjustment in single- and two-parent families, we compared and analyzed them separately. The intergenerational comparative analysis of PCGA revealed a difference between grandparents’ and parents’ scores in masculinity rearing. Grandparents’ scores were higher than parents’ scores (t = 4.03, p < 0.01). In contrast, there was no significant difference between the two generations for femininity rearing (Table 1).

The T-tests compared the differences between the PCGA of grandparents and parents in single- and two-parent families. The results revealed no significant difference in grandparents’ masculinity rearing, but a significant difference in femininity rearing, with the scores significantly higher in two-parent families than in single-parent families (t = −3.37, p < 0.01). Regarding the PCGA of parents, masculinity rearing and femininity rearing differed significantly between single- and two-parent families, and their scores were markedly higher in two-parent families than in single-parent families (masculinity rearing: t = −6.15, p < 0.01; femininity rearing: t = −6.98, p < 0.01) (see Table 2).

A comparative analysis of identity with parents found no significant difference between parents–children and children–parents in single- and two-parent families. Differential analysis of the identity across the three generations revealed no significant differences between the total scores of parents’ identity with grandparents and children’s identity with parents.

The intergenerational comparison of social adjustment in single- and two-parent families revealed significant differences in the dimensions and total scores of parents’ social adjustment. The scores of parents’ social adjustment in two-parent families were significantly higher than those in single-parent families. In terms of children’s social adjustment, its dimensions and total scores for single-parent families were markedly lower than for two-parent families (ps < 0.01). Moreover, there were significant differences between the parents’ and children’s social adjustment in all dimensions of the two types of family, and parents’ social adjustment scores were significantly higher than children’s scores (see Table 2). Overall, H1 was partially supported.

Mediating role of children’s identity with parents

To examine the mediating role of children’s identity with parents, this study conducted a correlation analysis of the variables. The analysis found that all variables were significantly correlated. Parent’s PCGA, children’s identity, and their social adjustment were significantly and positively correlated (ps < 0.01). The higher the parents’ PCGA scores, the higher the children’s identity with parents’ scores, and hence the more the subjects tended to exhibit better social adjustment (see Table 3).

The structural equation model (SEM) was used to examine the mediating role of children’s identity with parents in the relationship between parents’ PCGA and children’s social adjustment. The mediating model in this study fitted well: χ2 = 39.346, DF = 7, χ2/df = 5.621, CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.995, NFI = 0.998, IFI = 0.998, RMSEA = 0.031, SRMR = 0.009.

Bootstrap method was used with a put-back sample of 5000 times. The results showed that no mediating effect between parents’ masculinity rearing and children’s social adjustment was found. The mediating effect of children’s identity with parents in the relationship between parents’ femininity rearing and children’s social adjustment was 0.016, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [0.008, 0.024]. Since none of the 95% confidence intervals for the mediating effect values contained 0, children’s identity with parents mediated the relationship between parents’ femininity rearing and children’s social adjustment (see Table 4). Accordingly, H2 was partially supported.

Multigroup analysis of single- and two-parent families

In order to test the differences in the model across single-parent and two-parent families, this study used multi-group analysis. First, the model fitting effects were examined separately for the two types of families. The model fit indicators for single-parent families were: χ2 = 32.843, DF = 9, χ2/df = 3.649, CFI = 0.994, TLI = 0.987, NFI = 0.992, IFI = 0.994, RMSEA = 0.053, and the model fit indicators for two-parent families were: χ2 = 32.827, DF = 7, χ2/df = 4.690, CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.995, NFI = 0.998, IFI = 0.998, RMSEA = 0.031. It can be concluded that single-parent families and two-parent families met the test requirements and can be analyzed in multiple clusters.

Due to the goodness of fit of the baseline model for the relationship between PCGA and social adjustment across both family structures, we further tested the assumption of constancy of the structural path coefficients in the structural equation model for the different family structures. We ensured that the structural path coefficients in the structural equation model for the different family structures were all equal (called the Parallel Model). The results showed that the goodness-of-fit index of the Parallel Model was good: χ2 = 76.244, DF = 21, χ2/df = 3.059, CFI = 0.997, NFI = 0.996, IFI = 0.997, RMSEA = 0.021, indicating that the model fit well after restricting the structural path coefficients of single-parent and two-parent family groups to be equal.

Based on the above analysis, the results of a nested model comparison found that the p-value in the Structural Weights Model was 0.023, which is less than the significance level of 0.05, assuming the Model Measurement Weights to be correct. This indicates that there is a significant difference between the single-parent family and two-parent family group variable models in the corresponding qualification. CRD (critical ratio of difference) values greater than ±1.96 indicate statistical significance at 0.05 level. Further analysis of inter-parameter differences across multiple cohorts revealed the CRD of the path “Parents’ Masculinity Rearing → Children’s Identity with Parents” to be 2.826 > 1.96 in absolute terms between single- and two-parent families. This means that single- and two-parent families differed significantly on this pathway (single parents: β = 0.04, p < 0.05; two parents: β = −0.01, p > 0.05). Accordingly, H3 was supported.

Discussion

Family structure is an important aspect in terms of family influence, and its changes have a significant impact on children’s development. In this study, we conducted a paired survey on children and their parents in all families, analyzed the intergenerational differences in PCGA, identity with parents, social adjustment, and the relationship between the three variables across different family structures.

Intergenerational differences in PCGA, identity with parents and social adjustment in single- and two-parent families

The study found masculinity rearing differed significantly between grandparents and parents, with higher scores for the former (see Table 2). The development of gender attitudes can be influenced by changes in socioeconomic circumstances and personal life history (Jia and Ma, 2015). Grandparents grew up in the society before China’s Reform and Opening up (i.e., before 1978), when the concept of gender equality was not yet widespread among the population and traditional cultural structures ordered society and strong stereotypes persisted (Meng and Xu, 2012). Therefore, grandparents emphasized masculine-rearing attitudes. In contrast, the parents grew up in a rapidly changing society where gender roles were becoming looser and more fluid (Connor et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2014). The increased education of the parents also makes them more likely to be exposed to the values of femininity and gender equality. They are more likely to value the development of both masculine and feminine traits when raising their children. For example, grandparents emphasized “the gender division of labor between men and women” when raising children, while their children (i.e., the parents) might believe that men and women should be equally responsible for household chores. (Kong et al., 2020; Yang and Ci, 2021). In addition, under China’s one-child policy, most children born after the 1970s were only children. The only child is the pearl of the whole family and the parents have placed double expectations on them. Under the influence of spoiling and compensating psychology, parents would raise their sons with female standards intentionally or unintentionally, resulting in the weakening of their son’s masculinity (Xu, 2018; Zhang, 2020), such as being softly spoken, gentle, and considerate in their speech and behavior, dressing delicately (Li, 2012). There was no significant difference in femininity rearing between grandparents and parents (see Table 2). This suggests that femininity rearing was similar across the two generations and occurs through intergenerational transmission. The transmission mechanism could be explained by behaviorist theory: children will learn and imitate the behavior of their parents (Bandura, 1977; Li et al., 2016). Parents imitate and absorb grandparents’ PCGA, which is internalized into their own parenting attitudes. Mothers are more feminine, spend more time with their children than fathers, and have a greater influence on their children (Alesina et al., 2013), such that parents’ femininity rearing inherited from grandparents will be higher than that of masculinity rearing (van Putten et al., 2008; Qing, 2018). For example, mothers in Chinese families often need to take care of their children’s diet and living, take them to and from school, and undertake household activities, and such selfless qualities of giving to the family are also internalized in their children’s rearing, which can be seen in both generations of families (Wang et al., 2018). Chinese society is becoming more equal in gender perceptions in terms of these comprehensive indicators (Yang et al., 2014). Although women in the modern era are protected by the law to exercise equal rights with men and women, parents who grew up in a traditional patriarchal society still hold traditional views of women, such as “gentleness is a woman’s weapon” and “women should be diligent” (Du, 2018). So, there is a clear phenomenon of intergenerational transmission. This study further found that the masculinity rearing of grandparents did not differ significantly across family structures, implying that the grandparents’ generation valued masculinity rearing regardless of whether they were in single- or two-parent families. Before China’s Reform and Opening Up began in the late 1970s, China adhered to a development perspective that focused on economic growth and required a large male workforce to drive the economy (Zhan, 2008). In that context, there was a strong emphasis on masculinity, with males holding dominant positions in society and females very much in subservient roles (Meng and Xu, 2012), which led to a higher preference for sons in ancestral families. Such a perception may be the reason why masculine rearing is valued by grandparents regardless of family structure. In contrast, one difference between parents and grandparents was that the masculinity rearing of parents differed significantly in single- and two-parent families, being higher in two-parent families than in single-parent families. This might imply that fathers in two-parent families place more emphasis on masculine-rearing attitudes. It was found that children in two-parent families had their own gendered identity upbringing from an early age and acquired individual gender role knowledge from their parents regarding the appropriate behaviors and activities of males and females respectively (Chen and Zou, 2003). Children in single-parent families lack direct role models to emulate in their gender role learning (Chen et al., 2016). The gender role environment is also more homogeneous, and there is often a lack of the father’s role, so children are more likely to have gender misconceptions, such as male feminization, dressing up in fancy clothes, etc. (Fu and Zhu, 2017). Secondly, parents in single-parent families must take on dual roles and obligations to make ends meet, resulting in insufficient time and energy to spend with their children, which may in turn lead to a neglect of their children’s gender role education (Hu and Lian, 2010; Wang and Guo, 2008). The femininity rearing of grandparents and parents differed significantly in single- and two-parent families, with the latter scoring higher. It implied that PCGA in two-parent families placed more emphasis on femininity rearing than in single-parent families. This might be due to the absence of one parent in single-parent families (Su et al., 2020), the caregiver is busy earning money, caring less for their children, and focusing on fostering their independence (Bastaits and Mortelmans, 2016). Compared to two-parent families, two-parent families have complete parental roles and enough energy to raise their children and provide them with adequate care and support (Langton and Berger, 2011). Socioeconomic status might influence the parenting attitudes of two generations in single- and two-parent families. Studies have found that single-parent families have higher poverty rates and lower socioeconomic status than two-parent families (Daryanani et al., 2016). Families with high socioeconomic status have more social resources, enlightened views of the individual, and greater access to feminist ideas and gender equality concepts (Wang and Wu, 2019). Therefore, it is likely that single-parent families will have a more traditional parental children-rearing gender-role attitude. Therefore, it is likely that parents in two-parent families place more emphasis on feminine traits in PCGA.

This study found no significant difference between parents’ identity with grandparents and children’s identity with parents. In all cases the identities were high (see Table 2). The high degree of identity with parents might be influenced by traditional Chinese filial culture, which emphasizes filial respect for parents, family responsibilities, and interdependence among family members, and advocates that individuals follow socially accepted behavioral norms. Children who grow up in this cultural environment need to obey and accept authority and identify highly with it, especially with the elders in the family (Ng et al., 2014; Pomerantz and Wang, 2009). Secondly, the finding could also be explained by social learning theory, which states that the intergenerational transmission of attitudes is influenced by early formative experiences derived primarily from observing parental behavior, which in turn leads to learning and imitating parental attitudes and behaviors (Bugental and Grusec, 2006; Ranieri and Barni, 2012). Children’s identity with parents could be also internalized by learning from their parents’ expressions of the attitude toward the grandparents. As a result, children’s identity with parents might be similar to the parents’ identity with grandparents. The analysis of differences in single- and two-parent families’ identity with parents revealed no difference between the family structures. This finding contrasts with the findings of other studies (Wu et al., 2016), which have found that parent–child relationships worsen and parent-child conflict increases when parents divorce (Demir-Dagdas, 2021), and as a result, children in single-parent families may also identify less with their parents. Although changing family structure may increase the risk of problems between parents and children, it does not necessarily lead to the occurrence of problem behaviors (Rice, 2016). Even if the children of single-parent families live with one parent for a long time, watching their parent’s hard work in keeping the house, the caring heart for their parents may increase their attachment, and the relationship between parents and children is still very close (Dai, 2019; Perales et al., 2018; Raley and Sweeney, 2020). Thus, children’s identities with parents in single-parent and two-parent were no different.

It has been found that social adjustment differed between fathers and children. The scores of parents’ social adjustment were higher than those of children’s social adjustment (see Table 2). This is consistent with previous findings, that social adjustment is influenced by age and education level. Parents are older and more educated than their children, and their social adjustment continues to develop (Nie, 2005; Zou et al., 2015). In addition, the children in this study were mostly adolescents. With the arrival of adolescence, children undergo dramatic changes in their physical and mental development (Chen and Wang, 2015). After entering secondary school, children’s study tasks increase as they get closer to important midterm and college entrance exams. These exams are an important transition period for Chinese students in their lives and are highly correlated with their future development. Therefore, the pressure of schooling may also cause problems in their interpersonal interactions and mental health (Barry et al., 2019; Li, 2021). In contrast, parents, as adults, are at a different stage of development than their children. They have accumulated richer experiences by working in society. Therefore, parents’ social adjustment might be better than children’s adjustment. The social adjustment of both parents and children differed in single- and two-parent families. Two-parent family social adjustment was better than that in single-parent families. It was consistent with previous studies (Van Der Wal and Kok, 2019). Any radical changes in the family structure had a negative impact on children’s social development, and children in single-parent families had more social adjustment problems than those in two-parent families (Weaver and Schofield, 2015). Chinese society attaches great importance to family relationships and dignity (Jia et al., 2012). To a certain extent, the breakdown of the marriage relationship is regarded as a loss of family dignity and a disgrace to the entire family. Such traditional perceptions can easily create additional psychological pressures for children, thus inhibiting their positive development (Hadfield et al., 2018). Regardless of the factors contributing to single-parent families, parents need to spend a lot of time making psychological adjustments and thus may pay less attention to their children or neglect to care for them (Kalmijn, 2017; Leopold, 2018). These changes prompt children to reevaluate their internal work patterns and cope with challenges and stresses individually, potentially leading to difficulties in social adjustment (Mitchell et al., 2015). Studies have further found that divorce is more likely to occur in families of lower socioeconomic status, and the resulting income reduction for lone parents may further limit funds available to invest in the children’s education and other material inputs (Zhang, 2017). This may cause children to be prone to underperform academically, have trouble in interpersonal interactions, and lack emotional control, which affects social development (Dijk et al., 2020). Compared to single-parent families, parents in two-parent families can provide more resources for their children and effectively contribute to their social adjustment development (Lin et al., 2017; Reiss et al., 2013). These factors might contribute to the better social adjustment of children in two-parent families than that of children in single-parent families.

Mediating role of children’s identity with parents on parents’ PCGA and children’s social adjustment

It was found that parents’ PCGA positively predicted children’s social adjustment and children’s identity with parents mediated the relationship between parents’ femininity rearing and children’s social adjustment.

Parental child-rearing gender-role attitude could positively predict children’s social adjustment (see Table 3), a finding that is consistent with previous studies (Chen et al., 2016; Neppl et al., 2019). With the increasingly fierce social competition, children raised with traditional PCGA might hold gender stereotypes and find it difficult to cope with the complex and changing social environment (Zhao and Wang, 2012). In contrast, parents with enlightened PCGA may raise their children with both male and female sexuality, making them better able to adapt to and navigate a rapidly changing and increasingly complex social environment (Jiang and Jin, 2019; Zhao and Wang, 2012). Thus, parents’ PCGA may positively predict children’s social adjustment.

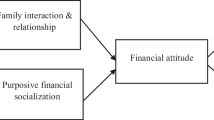

Children’s identity with parents mediated the relationship between parents’ femininity rearing and children’s social adjustment (see Fig. 1). This suggests that PCGA can not only directly influence children’s social adjustment, but can also exert a positive influence through identity as a mediator. In other words, when the score of parents’ femininity rearing is high, children’s identity with parents is also high, and subsequently, the social adjustment of children is better. Wang and Cui (2005) studied the relationship between gender differentiation and psychosocial adjustment in Chinese people and found that feminization was highly correlated with the level of psychosocial adjustment. Because traditional Chinese culture emphasizes harmony and cooperation, even if individuals have strong personal desires, they do not express them directly but need to achieve them through cooperation with others in a win–win or roundabout way (Wang, 2022). The traditional gender role conceptions of femininity fit this characteristic of Chinese culture. As a result, individuals who grow up with high femininity-rearing attitudes from their parents are better socially adjusted. In addition, when parents adopt femininity-rearing attitudes, they may cultivate personality traits such as warmth, empathy, sensitivity, and submissiveness in their children (Weisgram et al., 2011), thus making their children submissive to their own perspectives and increasing their identity with their parents. A higher level of children’s identity with parents also means that children are willing to accept and agree with their parents’ parenting attitudes, so communication between them is smooth and their parent–child relationship is better. It was found that high-quality parent–child relationships were significantly and positively associated with children’s social adjustment (Krikken et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2022). Therefore, the higher the children’s identity with parents, the better their social adjustment. It could be seen that parents’ femininity rearing may influence children’s social adjustment through their identity with parents (Table 5).

Multigroup analysis of single- and two-parent families

The results of the multi-group analysis revealed that the model differed significantly between single- and two-parent families, with the pathway from “Parents’ Masculinity Rearing to Children’s Identity with Parents” differing significantly in terms of family structure (see Fig. 2). Parents’ masculinity rearing in single-parent families influences children’s identity with parents, while in two-parent families it does not. Children raised in two-parent families acquire knowledge about masculine and feminine counterparts of gender roles and socially appropriate behaviors from their parents from an early age. In contrast, parents raised in single-parent families show more masculinity rearing their own children due to the lack of complete learning role models for gender roles such as when single-mother families take on both maternal and paternal responsibilities in their parenting (Hu and Lian, 2010; Wang and Guo, 2008). In Chinese culture, masculinity is highly respected (Xu, 2018). Masculinity, such as being strong, independent, and active can help children whose family structure has changed to actively cope with pressures in life, overcome suffering, and may indirectly improve their identity of masculinity (Read, 2020). Therefore, the children of single-parent families who receive more masculinity rearing are more aware of the positive effects of masculinity and thus increase their identities with masculinity rearing. These results also reflect the ‘male superiority’ phenomenon in traditional Chinese society. Women have been in a passive position for many thousands of years and it seems that they can only be successful and recognized if they have some masculine characteristics. A healthy gender culture should not only endorse the ‘Hanzi’ characteristics of men, but also build gender roles that truly respect the differences between men and women, value the individual, and are accepting of all genders.

This figure shows the mediating role of children’s identity with parents in single- and two-parent families. Numbers before the slash represented the results of single-parent families; Numbers after the slash represented the results of two-parent families. IR interpersonal relationship, AC academic achievement, LS life skills, MR mental resources. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

Limitations and future research

Our study has several limitations that should be addressed by future research. First, the influence mechanism of parental child-rearing gender-role attitude on social adjustment was explored in the context of single-parent and two-parent families. Yet there are many more classifications of family structures such as remarried families, besides single- and two-parent families. Family structures might thus be divided more carefully in future studies. Second, children’s views of their parents in this study were retrospective. This may have generated an inaccurate picture of parents’ rearing attitudes. We can increase the measurement of PCGA by including parents in future research. By integrating and comparing data from both parents and children, the study results can be made more objective. Third, all the variables in the study were measured based on self-reporting. Although the results showed that children’s identity with parents mediates the relationship between parents’ femininity rearing and children’s social adjustment, it was not possible to prove the causal relationship between the variables, and a longitudinal study on the development of parenting process and children’s social adjustment could be used in future studies. Fourth, the subjects of this study were collected in a specific economically developed area— Suzhou City, Jiangsu Province, China. In order to gain a deeper understanding of parental child-rearing gender-role attitudes and children’s social adjustment development in the Chinese cultural context, future studies might consider expanding the sample to other areas of China.

Conclusion

The current research expands the previous work and explores the influence of parents’ PCGA and children’s identity with parents on their social adjustment. This study found that there were partial intergenerational differences in PCGA, children’s identity with parents, and social adjustment in single- and two-parent families. Children’s identity with parents played an intermediary role between femininity rearing of PCGA and children’s social adjustment, and there were significant differences between single-parent and two-parent families. The result reveals parents should actively carry out androgynous gender role education, enhance communication and understanding with their children, and encourage frank dialog between them in order to improve the emotional connection and identity between family members and promote their social adjustment. In addition, in order to reduce the negative impact of family structure on children’s development, the government and social organizations should provide them with family education training and support, such as psychological counseling and parent-child communication skills training.

Data availability

Owing to privacy reasons, the datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ajzen I, Fishbein M (2005) The influence of attitudes on behavior. In: Albarracín D, Johnson BT, Zanna MP (eds) The handbook of attitudes. Mahwah, NJ:Erbaum, pp. 173–221

Alesina AF, Giuliano P, Nunn N (2013) On the origins of gender roles: women and the plough. Q J Econ 128(2):469–530. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjt005

Baldridge S (2011) Family stability and childhood behavioral outcomes: a critical review of the literature. J Fam Strengths 11(1). https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol11/iss1/8

Bandura A (1977) Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Baron RA, Byrne D (2003) Social psychology, 10th edn. Pearson Education, New York

Barry CT, Briggs SM, Sidoti CL (2019) Adolescent and parent reports of aggression and victimization on social media: associations with psychosocial adaptation. J Child Fam Stud 28(8). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.08.005

Bastaits K, Mortelmans D (2016) Parenting as mediator between post-divorce family structure and children’s well-being. J Child Fam Stud 225:2178–2188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0395-8

Bisin A, Verdier T (2000) “Beyond the melting pot”: cultural transmission, marriage, and the evolution of ethnic and religious traits. Q J Econ 115(3):955–988. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300554953

Brito S, Carneiro N, Nogueira C (2021) Playing gender(s): the re/construction of a suspect ‘gender identity’ through play. Ethnogr Edu 16:384–401

Bronfenbrenner U (1986) Ecology of the family as a context for human development: research perspectives. Dev Psychol 22(6):723–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723

Bugental DB, Grusec JE (2006) Socialization theory. Wiley, New York

Busygina AL, Rudenko IV, Arkhipova IV, Firsova TA, Murtazina DA, Shichiyakh RA (2019) Study of the features of family education in the process of social adaptation of a child. Religación 4(13):346–352

Bzostek SH, Berger LM (2017) Family structure experiences and child socioemotional development during the first nine years of life: examining heterogeneity by family structure at birth. Demography 54(2):513–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-017-0563-5

Chen IJ, Shen YF, Zhang HL (2016) The relationship between single parents’ sex-role types and children’s social adaptation: the mediating role of child-rearing sex-role attitude. Psychol Dev Educ 32(3):301–309. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2016.03.06

Chen IJ, Zhang H, Wei B et al. (2018) The model of children’s social adjustment under the gender-roles absence in single-parent families. Int J Psychol 54(3):316–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12477

Chen ME, Zou J (2003) Gender role displacement and educational strategies for children in single-parent families. J Yibin Coll 3(2):90–92. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-5365.2003.02.030

Chen S, Wang GX (2015) Cyber risk factors and protective factors of juvenile delinquency. Psychol Tech Appl 3:31–37. https://doi.org/10.16842/j.cnki.issn2095-5588.2015.03.008

Connor S, Edvardsson K, Fisher C et al. (2021) Perceptions and interpretation of contemporary masculinities in western culture: a systematic review. Am J Mens Health 15(6):579–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/15579883211061009

Dai RQ (2019) The problem of “gender awareness education” in single-parent families, reflection, and deconstruction. Law Soc 28:247–248. https://doi.org/10.19387/j.cnki.1009-0592.2019.10.117

Darling N, Steinberg L (1993) Parenting style as context: an integrative model. Psychol Bull 113(3):487–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487

Daryanani I, Hamilton JL, Abramson LY et al. (2016) Single mother parenting and adolescent psychopathology. J Abnorm Child Psychol 44(7):1411–1423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0128-x

Demir-Dagdas T (2021) Parental divorce, parent-child ties, and health: explaining long-term age differences in vulnerability. Marriage Fam Rev 57(1):24–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2020.1754318

Dijk RV, Valk I, Dekovi M et al (2020) A meta-analysis on interparental conflict, parenting, and child adjustment in divorced families: examining mediation using meta-analytic structural equation models. Clin Psychol Rev 79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101861

Dhar D, Jain T, Jayachandran S (2019) Intergenerational transmission of gender attitudes: evidence from India. J Dev Stud 55(12):2572–2592. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1520214

Doepke M, Zilibotti F (2014) Parenting with style: altruism and paternalism in intergenerational preference transmission. Econometrica 85:1331–1371. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA14634

Du JM, Feng XT (2000) School education and children’s gender role socialization. Guangxi Soc Sci 4:124–126

Du MR (2018) Gender and the awakening of Chinese women’s consciousness and the counterattack: an example of attacking the “Female degeneracy theory”. J News Res 21:49–50

Eirini E, Midouhas E, Joshi H, Tzavidis N (2014) Emotional and behavioural resilience to multiple risk exposure in early life: the role of parenting. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24(7):745–755

Endendijk JJ, Groeneveld MG, Mesman J (2018) The gendered family process model: An integrative framework of gender in the family. Arch Sex Behav 47(4):877–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1185-8

Farré L, Vella F (2013) The intergenerational transmission of gender role attitudes and its implications for female labour force participation. Economica 80(318):219–247. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24029846

Fazio RH (1986) How do attitudes guide behavior? In: Sorrentino RM, Higgins ET (eds) Handbook of motivation and cognition. Guilford, New York, pp. 204–243

Francis B (2010) Gender, toys, and learning. Oxf Rev Educ 36(3):325–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054981003732278

Fu D, Zhu SS (2017) Gender education in divorced families and case studies. Youth Years 9:473–474

Fulcher M, Sutfin EL, Patterson CJ (2008) Individual differences in gender development: associations with parental sexual orientation, attitudes, and division of labor. Sex Roles 58:330–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9348-4

Hadfield K, Amos MA, Ungar M et al. (2018) Do changes to family structure affect child and family outcomes? A systematic review of the Instability Hypothesis. J Fam Theory Rev 10:87–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12243

Han XY, Wei YB (2004) A study of adolescents in divorced families-reflections on a unique case. Youth Stud 7:9

Hastings PD, McShane KE, Parker R et al. (2007) Ready to make nice: parental socialization of young sons’ and daughters’ prosocial behaviors with peers. J Genet Psychol 168:177–200. https://doi.org/10.3200/gntp.168.2.177-200

Hjelmér C (2020) Free play, free choices?—Influence and construction of gender in preschools in different local contexts. Educ Inq 11:144–158

Hu SM (2014) The effect of parental job insecurity on college students’ life satisfaction: the moderating role of parental approval. Chin. J Clin Psychol 22(5):868–872. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2014.05.071

Hu XH, Lian X (2010) Towards mainstreaming gender equality education: experiences and insights from Taiwan. J Inn Mongolia Norm Univ: Philos Soc Sci Ed 5:113–118

Huang LL (2008) Exploring the content of intergenerational transmission of values and its mechanisms. Unpublished Master’s thesis, East China Normal University

Jasmin H, Heather F, Kurt H et al. (2017) Impact of relationship status and quality (family type) on the mental health of mothers and their children: a 10-year longitudinal study. Front Psychiatry 8:266. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00266

Jia ZF, Li XP, Chang Z (2012) Why do Chinese people value interpersonal relationships? A psychological perspective. Soc Psychol Sci 27(11):6

Jia YZ, Ma DL (2015) Multiple perspectives on changing gender concepts: The case of “male domination and female domination”. Women’s Stud Ser 3:29–36. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-2563.2015.03.003

Jiang X, Jin ZZ (2019) The effect of gender role types on risky decisions making tendencies among college students. Youth Soc 19:2

Kalmijn M (2017) Family structure and the well-being of immigrant children in four European countries. Int Migr Rev 51(4):927–963. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12262

Kim SJ, Glassgow AE (2018) The effect of father’s absence, parental adverse events, and neighborhood disadvantage on children’s aggression and delinquency: a multi-analytic approach. J Hum Behav Soc Environ 28:570–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2018.1443866

Kingsbury MK, Coplan RJ (2012) Mothers’ gender-role attitudes and their responses to young children’s hypothetical display of shy and aggressive behaviors. Sex Roles 66:506–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0120-z

Kiraz A, Ersoy MA (2018) Analysing the self-esteem level of adolescents with divorced parents. Qual Quant 52:321–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0614-4

Kline RB (2011) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 3rd edn. The Guilford Press, New York

Kollmayer M, Schultes MT, Schober B et al. (2018) Parents’ judgments about the desirability of toys for their children: associations with gender role attitudes, gender-typing of toys, and demographics. Sex Roles 79:329–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0882-4

Kong XW, Wang QX, Li XM, Yu Y (2020) The influence of family gender perceptions on the positive development of female college students—the mediating role of self-worth. Psychol Mon 17:78–80. https://doi.org/10.19738/j.cnki.psy.2020.17.027

Krikken JB, van Wijk AJ, ten Cate JM, Veerkamp JS (2012) Child dental anxiety, parental rearing style and referral status of children. Community Dent Health 29(4):289–292

Langton CE, Berger LM (2011) Family structure and adolescent physical health, behavior and emotional well-being. Soc Serv Rev 85:323–357

Lansford JE, Ceballo R, Abbey A et al. (2004) Does family structure matter? A comparison of adoptive, two-parent biological, single-mother, stepfather, and stepmother households. J Marriage Fam 63:840–851. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00840.x

Lee D, McLanahan S (2015) Family structure transitions and child development: instability selection, and population heterogeneity. Am Sociol Rev 80(4):738–763. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122415592129

Lee S (2019) Romantic relationships in young adulthood: parental divorce, parent-child relationships during adolescence, and gender. J Child Fam Stud 28:411–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1284-0

Leopold T (2018) Gender differences in the consequences of divorce: a study of multiple outcomes. Demography 55:769–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0667-6

Li JC (2012) Gender identity of body performance: a cultural interpretation of the pseudo-maiden phenomenon. Lanzhou J 05:103–106

Li QM, Chen ZX, Xu HY (2016) Effects of parental rearing styles and parents’ gender on intergenerational transmission of filial piety. Psychol Explor 36(4):358–364

Li SY (2021) A study on the relationship between parenting style, self-esteem and social adjustment of middle school students. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Shanxi University of Technology

Li Y (2021) An exploration of mental health education strategies for children in single-parent families. New Curric 52:230

Liang ZB, Wu AL, Zhang GZ (2022) The relationship between negative parenting styles and preschool children’s social adjustment problems: the mediating role of parent-child conflict. Presch Edu Res 3:43–52

Lin IF, Brown SL, Hammersmith AM (2017) Marital biography, social security receipt, and poverty. Res Aging 39(1):86–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027516656139

Liu HG, Guo LC, Li YF, Yang Z (2011) The current situation of parental identity and educational suggestions for contemporary teacher training students. J Chengdu Aeronaut Vocat Tech Coll 27(3):15–18. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-4024.2011.03.006

Maccoby EE (2015) Historical overview of socialization research and theory. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD (eds) Handbook of socialization: theory and research. New York, p 3–32

Mahoney JL, Bergman LR (2002) Conceptual and methodological considerations in a developmental approach to the study of positive adaptation. J Appl Dev Psychol 23:195–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-3973

Mandara J, Murray CB, Joyner TN (2005) The impact of fathers’ absence on African American adolescents’ gender role development. Sex Roles 53:207–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-5679-1

Masud H, Thurasamy R, Ahmad MS (2015) Parenting styles and academic achievement of young adolescents: a systematic literature review. Qual Quant 49:2411–2433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-014-0120-x

McCauley EA, Schloredt KA, Gudmundsen GR et al. (2011) Expanding behavioral activation to depressed adolescents: lessons learned in treatment development. Cogn Behav Pract 18:371–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.07.006

Mead GH (1967) Mind, self, and society from the standpoint of a social behaviorist. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Meng XF, Xu YH (2012) A study on gender consciousness of high-level female talents and its influencing factors—a survey based on Fujian Province. Women’s Stud Ser 1:12–21

Mitchell C, Brooks-Gunn J, Garfinkel I et al. (2015) Family structure instability, genetic sensitivity, and child well-being. Am J Sociol 120(4):1195–1225. https://doi.org/10.1086/680681

Nahkur O, Kutsar D (2022) Family type differences in children’s satisfaction with people they live with and perceptions about their (step)parents’ parenting practices. Soc Sci 11(5):223. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050223

Neppl TK, Wedmore H, Senia JM et al. (2019) Couple interaction and child social competence: the role of parenting and attachment. Rev Soc Dev 28(2):347–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12339

Ng FF, Pomerantz EM, Deng C (2014) Why are Chinese mothers more controlling than American mothers? “My child is my report card”. Child Dev 85(1):355–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12102

Nie YG (2005) A study of adolescents’ socially adaptive behavior and the influencing factors. Unpublished Master’s thesis, South China Normal University

Park H, Lee KS (2020) The association of family structure with health behavior, mental health, and perceived academic achievement among adolescents: a 2018 Korean nationally representative survey. BMC Public Health 20:510. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08655-z

Perales F, Jarallah Y, Baxter J (2018) Men’s and women’s gender-role attitudes across the transition to parenthood: accounting for child’s gender. Soc Forces 97:251–275. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soy015

Pomerantz EM, Wang Q (2009) The role of parental control in children’s development in western and east Asian countries. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 18(5):285–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01653.x

Qing SS (2018) An analysis of intergenerational transmission of gender role perceptions in China. Chin Popul Sci 6:14

Raley RK, Sweeney MM (2020) Divorce, repartnering, and stepfamilies: a decade in review. J Marriage Fam 82(1):81–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12651

Raley SB, Bianchi SM (2006) Sons, daughters, and family processes: does gender of children Matter? Rev Sociol 32:401–421

Ranieri S, Barni D (2012) Family and other social contexts in the intergenerational transmission of values. Fam Sci 3:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/19424620.2012.714591

Read EL (2020) Exploring perspectives on masculinity and mental wellbeing: the case of students in higher education in New Zealand. Open Access Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington. https://doi.org/10.26686/wgtn.17142794.v1

Reiss AL, Vrticka P, Neely M et al. (2013) Sex differences during humor appreciation in child-sibling pairs. Soc Neurosci 8(4):291–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2013.794751

Rice D (2016) Adolescent psychology (trans: Huang JH, Lian TJ). Xue Fu Culture Business Co, Taipei

Schneider BH, Atkinson L, Tardif C (2001) Child–parent attachment and children’s peer relations: a quantitative review. Dev Psychol 37(1):86–100

Suzhou Bureau of Statistics (2022) Suzhou statistical yearbook. China Statistics Press

Sowislo JF, Orth U (2013) Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull 139:213–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028931

Su YY, Cui CY, Xu DL (2020) Analysis of the current situation of gender equality awareness and influencing factors among children and adolescents. Ment Health Edu Prim Second Sch 25:4–7

Tang C (2016) A study on the relationship between parenting style, gender role identity and mental health in adolescence. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Nanjing Normal University

Usoroh CI, Akpan ID, Amadi NB et al. (2014) A comparative study of the effect of family types on social adjustment of adolescent in Aba, Abia state. Civil Environ Res 8(6):147–151

Van der Wal CN, Kok RN (2019) Laughter-inducing therapies: systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med 232:473–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.02.018

van Putten AE, Dykstra PA, Schippers JJ (2008) Just like Mom? The intergenerational reproduction of women’s paid work. Eur Soc Rev 24(4):435–449. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25209177

Wang C (2022) The historical generation of traditional Chinese culture’s concept of harmony and its contemporary value. Shandong Soc Sci 05:180–185. https://doi.org/10.14112/j.cnki.37-1053/c.2022.05.009

Wang DF, Cui H (2005) Chinses “Big Seven” personality structure: a theoretical analysis. Chin Soc Psychol Rev 1:94–126

Wang EG, Guo MY (2008) Children’s gender role development and its influencing factors. Psychol Res 2:32–35

Wang MF, Yuan CC, Yang F, Cao RY (2013) Parents’ child-rearing sex-role attitudes and its relationship with their gender schematicity. Chin J Clin Psychol 21(4):646–649. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2013.04.018

Wang MM, Zhang QY, Ren LW et al (2019) Intergenerational transmission of anxiety: the mediating role of parent–child relationship. Paper presented at the 22nd National Psychology conference, Hangzhou Normal University, Zhejiang,18-20 October 2019

Wang P, Wu YX (2019) Socioeconomic status, gender inequality, and gender role perceptions. Soc Rev 7(2):55–70

Wang X, Liu YL, Lin J, Liu CX, Wei LZ, Qiu HY (2022) The effect of parent–child relationships on middle school students’ mental health: the chain mediating role of social support and psychological suzhi. Psychol Dev Edu 2:263–271

Wang Y, Chen BB, Li WY, Qian XY (2018) A study on the intergenerational transmission of parenting from the life history theory. Psychol Sci 3:608–614

Weaver JM, Schofield TJ (2015) Mediation and moderation of divorce effects on children’s behavior problems. J Fam Psychol 29(1):39–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000043

Weisgram ES, Dinella LM, Fulcher M (2011) The role of masculinity/femininity, values, and occupational value affordances in shaping young men’s and women’s occupational choices. Sex Roles 65:243–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9998-0

Wood E, Desmarais S, Gugula S (2002) The impact of parenting experience on gender stereotyped toy play of children. Sex Roles 47:39–49. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020679619728

Wu M, Liu ZG, Liang LC (2016) Parent–child relationship impact on children’s mental development. J Beijing Norm Univ: Soc Sci Ed 5:9

Xie BF, Fang YN, Lin YQ, Chen YH, Jin Y, Hu HF, Wang F (2004) Rearing style of their parents influenced on adaptive behavior and study scores of pupils. Chin J Behav Med Sci 13(5):3

Xie SL (2021) Case work involved in children’s learning difficulties from single-parent families—a case study from a poverty village in Chongqing. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Xinan University

Xu JM (2018) A study of gender role socialization of only children in the context of single-sex growth. Youth Quest 6:91–100. https://doi.org/10.13583/j.cnki.issn1004-3780.2018.06.008

Yang JH, Li HJ, Zhu G (2014) Analysis of the trends and characteristics of Chinese people’s gender perceptions in the past 20 years. Women’s Stud Ser 6:28–36

Yang XL, Ci QY (2021) The influence of female labor participation and income level on male gender perception. J Shandong Women’s Coll 6:10

Yang YP, Jin Y (2007) The development of the middle school student’s social adaptation scale. Psychol Dev Edu 4:108–114

Yang X, Gao C (2021) Missing women in STEM in China: an empirical study from the viewpoint of achievement motivation and gender socialization. Res Sci Educ 51:1705–1723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-019-9833-0

Zhan HW (2008) From traditional development concept, new development concept to scientific development concept. J Yunnan Univ Natl: Philos Soc Sci Ed 25(5):64–68

Zhao TT, Wang XC (2012) Relationship between college students’ sex role and adaptation—a comparative study between sex-role reversed and sex role stereotyped. Chin J Clin Psychol 20(3):3

Zhang CN (2017) The impact of contemporary Chinese youth parental divorce on children’s development—an empirical study based on CFPS 2010–2014. China Youth Study 1:4–16. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-9931.2017.01.001

Zhang L, Gao DH (2015) Analysis of the characteristics and causes of peer interaction among classroom children. Stud Early Child Educ 4:64–66. https://doi.org/10.13861/j.cnki.sece

Zhang Y, Guo C, Hou X, Chen W, Meng H (2021) Variants of social adaptation in Chinese adolescents: a latent profile analysis. Curr Psychol 42:10761–10774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02362-7

Zhang YS (2020) A discussion on the representation of the subcultural “pseudo-queen phenomenon”. Educ Res 3(8):196–198

Zhou H, Long LR (2004) A statistical test and control method for common method bias. Adv Psychol Sci 12(6):942–950. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-3710.2004.06.018

Zou H, Liu Y, Zhang WJ, Jiang S, Zhou H, Yu YB (2015) Adolescents’ social adjustment: a conceptual model, assessment, and multiple protective and risk factors. Psychol Dev Edu 31(1):29–36. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2015.01.05

Zuilkowski SS, Thulin EJ, McLean KE, Rogers TM, Akinsulure-Smith AMB (2019) Parenting and discipline in post-conflict Sierra Leone. Child Abuse Negl 97:104138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104138

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (grant number 18BRK039). The authors wish to thank the teachers who supported and assisted the project research and the participants who participated in the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I-JC composed the conception and design and drafted the article. YW interpreted data and revised it critically for important intellectual content. ZS collaborated with the writing of the study. YS provided data methodology and analysis help. LW and MY made critical comments and amendments. Correspondence to I-JC.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Soochow University (protocol code KY20220564B). All procedures performed in research involving human participants conform to the ethical standards of the Institutional Research Council and conform to the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and subsequent amendments.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Participation was voluntary and informed written consent was obtained from all the students and their legal guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, IJ., Wang, Y., Sun, Z. et al. The influence of the parental child-rearing gender-role attitude on children’s social adjustment in single- and two-parent families: the mediating role of intergenerational identity. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 676 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02184-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02184-x