Abstract

The importance of stability has been consistently emphasized in China and the discursive use of stability is found to have legitimizing effects in Chinese newspapers, but how such political keywords are employed by the newspaper of a country that is ideologically distinct from China remains underexplored. This study addresses this gap by investigating the use of stability in The New York Times’ coverage of China between 1980 and 2020, drawing on critical discourse analysis (particularly, the discourse-historical approach) and sentiment analysis. A diachronic quantitative analysis demonstrates an overall negative sentiment in news reports relating to China’s stability across these years, with positive sentiment evident only during the 1980s and negative sentiment prevailing from 1990 to 2020. These findings are consistent with general trends in US-China relations and US foreign policy over the four decades. Qualitative analysis reveals that negative sentiment focuses on sociopolitical and territorial issues, whereas positive sentiment focuses primarily on economic and financial aspects, indicating that the newspaper views the issue of China’s stability from a politically self-interested perspective of the US and is also concerned about the persistence of certain dominant ideologies in American society. This study contributes to a greater comprehension of the use of political keywords in national and international news discourse, especially by the media of ideologically diverse societies. Moreover, because the application of sentiment analysis to critical discourse analysis and news discourse analysis has proven to be time-efficient, verifiable, and accurate, researchers can confidently employ it to disclose hidden meanings in texts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the beginning of China’s era of reform and opening up in 1978, the importance of stability has been consistently emphasized. In government work reports, press conferences, and official media, the political keyword “stability” (稳定, wen ding) is frequently collocated with other words to form phrases such as “social stability,” “political stability,” “stability and peace,” and “stability and prosperity.” These collocations refer to the fundamentals of a decent life, such as a peaceful and secure existence, a functioning legal system, economic prosperity, and opportunities for personal and social advancement, and imply that the Chinese government is responsible for ensuring these fundamentals.

The discursive use of stability is profoundly rooted in China’s traditional political philosophies concerning the right to rule and the ethics of governance. The normative principles such as the “Mandate of Heaven” (天命, tian ming), “rule by virtue” (仁治, ren zhi), “legality and ritual” (法礼, fa li), and “putting people first” (人本, ren ben) were conceived during the pre-Qin period, canonized in the Spring-Autumn period, and institutionalized in the Han dynasty (Banwo, 2015), in the hope of achieving the Confucian paradise of “true harmony” (大同, da tong). According to these fundamental principles, the divine source of authority (Heaven) legitimized the right to govern China’s rulers and emperors, who were obligated to make decisions in the best interests of their people and even share their recreational parks. A leader who violated the principle of beneficence would be deposed and replaced by the populace.

The victory of the War of Liberation between 1946 and 1949 initially legitimized the Communist Party of China (CPC) as the governing party of modern China, which claimed to aim at establishing a free, egalitarian, and democratic nation. Between 1966 and 1976, after a decade of the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese government recognized the importance of stability for the country’s economic development. In 1989, one of Deng Xiaoping’s basic tenets was “Stability is of paramount importance” (稳定压倒一切, wen ding ya dao yi qie) (Deng, 1994). Consequently, “stability” has become one of China’s most frequently used political keywords. Deng’s successors inherited his legacy which emphasized the importance of a stable domestic and international environment for creating and sustaining a “moderately prosperous society,” eradicating poverty and achieving the Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation and world peace.

In China, stability has never been a simple matter. Over the past decade, scholars in the social sciences have examined the country’s internal stability from various perspectives in an effort to find effective ways to address the complexities. As noted by Liebman (2014), in their efforts to balance legal reform, political stability, and social stability, China’s leaders faced the law-stability paradox, in which party-state leaders do not trust the country’s legal institutions to resolve the most complex issues resulting from China’s rapid social transformation. In the 2010s, when the cost of sustaining economic stability soared, Yu (2014) argued that China could benefit from a transition from “rigid stability” to “resilient stability.” To ensure the country’s long-term stability, it was also recommended that a more equitable system of social allocation be implemented, and that the government provide more support for the public’s swiftly growing desire for greater political participation.

From a discoursal perspective, Sandby-Thomas examined the political keyword “stability” (2014). Using discourse-historical analysis (DHA), an approach of critical discourse analysis (CDA), he investigated the legitimizing effect of the discourse of stability in editorials and commentaries published by People’s Daily, the official Chinese-language newspaper with the largest circulation in China. Qualitative data analysis revealed that the discourse of stability was ideologically flexible: Its positive value was used to legitimize the party-state’s authority by portraying stability as closely related to the country’s national interest, while its negative value was used to delegitimize an assigned “other.”

Because few studies have probed into how the political keyword “stability” is used in articles published by the major newspapers of countries with political systems ideologically different than China’s, the purpose of this study is to investigate how The New York Times, one of the most influential national newspapers in the United States, utilizes this keyword in its reporting. Specifically, by reviewing this newspaper’s portrayals of China, this study seeks to answer the following questions drawing on the approach of CDA and utilizing the relatively new technique of sentiment analysis: (1) What sentiments (positive, negative, or neutral) toward China did The New York Times discursively construct over the 41-year period through the use of the political keyword “stability”? (2) What facets did the newspaper mainly focus on with regard to the discourse of stability relative to China? In addition to the “how” and “what” questions, this study seeks to answer the “why” question by examining the relationship between The New York Times’ use of “stability” as a political keyword and the dominant ideologies in the United States.

CDA is adopted as the theoretical base of this study because of its foci on “the relationship between language, ideology, and power, and the relationship between discourse and social change” (Fairclough, 1992, pp. 68–69). In the CDA framework, an ideology is equivalent to a worldview, an (often) one-sided perspective with related mental representations, convictions, opinions, attitudes, and evaluations shared by a specific community (Reisigl and Wodak, 2009, p. 88). With the assistance of corpus linguistics (CL), it can be unveiled by investigating certain salient language patterns in a research corpus and predetermined language patterns based on the background knowledge of the specific sociopolitical issue under investigation that the researcher possesses (Love and Baker, 2015).

In order to answer the “how” and “why” questions, among various strands of CDA, the DHA method developed by Wodak (1996) is selected for analyzing and discussing the results obtained by corpus tools, which focuses not only on the internal co-text of language patterns but also on the broad historical contexts of the sociopolitical issue in question (Reisigl and Wodak, 2009, p. 93). The historical perspective is very helpful to discourse analysts while they explore evolving changes in discourse practice over a long period of time. Of five types of proposed discursive strategies (i.e., nomination, predication, argumentation, perspectivization, and intensification/mitigation), the strategies of nomination and predication are heavily relied on in the detailed analysis of utterances because news reports focus on the description of specific events, which involve social actors, objects, phenomena, processes, and actions. According to Reisigl and Wodak (2009, pp. 93–94), the nomination strategy refers to discursive construction of events, social actors, objects, phenomena, processes, and actions by way of such devices as membership categorization devices, deictics, and anthroponyms, while the predicational strategy means discursive characterization of these stuff in a positive, neutral, or negative manner in the form of adjective, appositions, prepositional clauses, explicit predicates, etc., hence they are suitable for the micro-analysis of news discourse.

A brief review of US media representations of China

As a result of its policy of reform and opening up over the past four decades, the rise of China has garnered a great deal of attention from US media as well as scholars in the social sciences, particularly those in the fields of media and discourse studies. According to a bibliometric study of news discourse analysis from 1988 to 2020, “China” was one of the top 30 keywords from 1988 through 2000 and from 2008 through 2020. In addition, from 2001 through 2007, the keyword “Hong Kong” ranked 24th, indicating that China-related issues have been salient to news discourse analysts since 1988 (Wang et al. 2022).

Media representations of China and its social, political, diplomatic, environmental, economic, and sporting events have been the subject of a large number of academic studies. The majority of these studies have utilized qualitative methods, or a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods, to analyze media texts or selections from such texts in order to determine whether China as a whole, or a particular China-related issue, is being depicted in a positive, neutral, or negative light through the use of specific media frames, language patterns, or discursive devices over specific periods of time.

These studies either portray the evolving relations between China and the United States against a background of specific historical and sociopolitical contexts or indirectly relate their findings to such contexts, because the national media of a foreign country typically depicts its concerns and problems in a manner consistent with its own dominant ideology (van Dijk, 1988; Wang, 1991), foreign policy (Cook, 1997; Seib, 1997), and national interest (Yan, 1998; Wang, 2017; Chen and Wang, 2022a, 2022b).

Over the last twenty years, the US national media has consistently portrayed China in a negative light, despite variations in degree (e.g., Liss, 2003; Peng, 2004; Tang, 2021). During the first half of the 2010s, there was a slight but noticeable movement toward the positive in the US media’s coverage of China (Moyo, 2010; Syed, 2010). However, when the Sino-US currency disputes erupted, hardline viewpoints that China’s rapid growth was becoming a threat to the economy and national security of the United States began to prevail (Liu, 2015, 2017) and, with the escalation of trade disputes between China and the United States at the end of the decade, instances of sinophobic attitudes toward China in US news discourse significantly increased (Chen and Wang, 2022a, 2022b). What’s more, the US media’s coverage of the Hong Kong activists’ fight for independence and democratic rule in the 2019–2020 Anti-extradition Bill Movement became increasingly critical of the mainland Chinese government (Wang and Ma, 2021). In their news coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic, the news discourse of the mainstream US media also showed a clear tendency to depict China as a cultural or racial “other” (Chung et al. 2021).

Despite extensive research on the reporting of China-related issues, only a few diachronic studies spanning one or more decades exist. Yan (1998) investigated The New York Times’ news coverage of China from 1949 to 1988. Over the course of four decades, the newspaper maintained an interest in the same political, diplomatic, economic, and military issues, with the Taiwan question and Sino-Soviet relations remaining prominent. In addition, Peng (2004) conducted a comparative analysis of The New York Times and Los Angeles Times’ coverage of China between 1992 and 2001. While he found no significant differences between the two newspapers, he pointed out the substantial increase in the number of news articles over time and a generally negative tone for both. The study also revealed that while most political and ideological frames were viewed unfavorably, economic frames were consistently viewed more favorably.

In light of the fact that a diachronic study typically provides a comprehensive picture of a particular research topic, the purpose of this study is to investigate what facets The New York Times focused on through its use of the discourse of stability related to China in the shifting sociopolitical contexts of the US and China since the 1980s.

The synergy of critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics

CDA investigates the interwoven nature of inequality, authority, and ideology at various linguistic levels of discourse (Fowler, 1991; van Dijk, 2009). From a discoursal perspective, news discourse, which claims neutrality and objectivity, is in fact a typical form of ideological discourse (van Dijk, 2009, p. 195) that provides “categories for reality” that contribute “primarily to social control and reproduction” (Fairclough, 1992, p. 161). To address the criticism of “cherry picking” by other scholars in the social sciences, Hardt-Mautner (1995) introduced the techniques of CL to CDA in her study of news reporting on the European Union in the British press. Later, Baker et al. (2008) further advocated a “useful methodological synergy” of CL and CDA. Since then, corpus-based or corpus-assisted CDA has been employed extensively in news discourse analysis over the past two decades.

The proportionate application of CDA and corpus linguistics helps analysts confirm, refute, or revise their own intuition by demonstrating why and to what extent their suspicions are founded (Partington, 2012, p. 12). For example, corpus techniques such as high-frequency words, collocation, and keyword analysis are used to identify linguistic patterns not readily discernible to the human eye, and concordance analysis is also employed to delve deeply into the aboutness of specific texts. With the advancement of CL and natural language processing (NLP) in recent years, new techniques have been applied to discourse studies, with sentiment analysis emerging as one of the most effective. Sentiment analysis, a technique that combines NLP and machine learning to determine whether a piece of text is positive, negative, or neutral, is used in this study to reveal the sentiment implied in the sentences containing the political word “stability”, thus enhancing the objectivity of the study.

Sentiment analysis

Sentiment analysis is the study of emotions, opinions, assessments, and attitudes expressed in various media forms regarding “services, products, individuals, organizations, issues, topics, events, and their attributes” (D’Andrea et al. 2015, p. 27), and it is often used to detect public sentiment on social media platforms (Kotzé and Senekal, 2018; Wicke and Bolognesi, 2021). There are three levels of sentiment analysis: document level, sentence level, and aspect level (D’Andrea et al. 2015; Feldman, 2013). In this context, a document consists of one or more sentences and corresponds to the term ‘text’ as commonly applied in discourse analysis. Document-level analysis assesses the overall tone or sentiment of a given text; sentence-level analysis focuses on the sentiment expressed in the words of a specific sentence. And, when an entity—a product, for example—has multiple characteristics, features, or “aspects,” it is necessary to conduct an aspect-level analysis which may include such things as price, functionality, and appearance.

Researchers usually employ one of two types of approaches to conduct a sentiment analysis: either a standard machine-learning method or a lexicon-based method, also called “unsupervised/lexicon-based machine learning.” Sentiment analysis that is based on machine learning is “a classification-based method that employs classification algorithms to determine the sentiment of a text” (Lei and Liu, 2021). However, some researchers prefer to use the unsupervised/lexicon-based method because the standard machine-learning method is as yet unable to incorporate general semantic knowledge and does not support labeled data (Taboada et al. 2011). Lexicon-based methods rely on one or more sentiment lexicons to ascertain the polarity of textual data (Nasim et al. 2017). Well-known sentiment lexicons include the Jockers & Rinker Polarity Lookup Table, the Syuzhet Lexicon, the Bing Lexicon, and the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC). The lexicon-based method compares the words in a text to those in the chosen lexicon dictionary and calculates a sentiment score for the text based on word values. This approach has been shown to efficiently and effectively analyze texts presented on Internet blogs, online forums, and product evaluations at the document and sentence levels (Ding et al. 2008; Kim and Hovy, 2004; Turney, 2002). After carefully considering the relative efficacy of this and other methods, we chose to utilize a lexicon-based methodology for our study.

In addition to its usefulness in analyzing social media discourse, sentiment analysis can also be applied to the examination of news discourse. For instance, Smirnova et al. (2017) used LIWC to examine the sentiment toward Russia and Islam in The New York Times. Some years later, Taufek et al. (2021) used the Azure Machine-Learning software to reveal the polarity of sentiment in the same newspaper to identify trends in public perception of climate change. Vargas-Sierra and Orts (2023) explored how two respected financial newspapers (The Economist in English and Expansión in Spanish) emotionally verbalized the economic havoc of the COVID-19 period and enhanced the understanding of the reshaping the linguistic landscape of financial journalism in crisis.

Here, please note that sentiment analysis is distinct from appraisal analysis (Martin and White, 2005) and prosody analysis (Sinclair, 1991, 2004). Whereas semantic prosody focuses on a pragmatic unit of meaning and consists of extensive searches and analyses of the unit in context, appraisal analysis emphasizes a pragmatic unit of meaning and involves extensive searches and analyses of the unit. In contrast, in sentiment analysis, sentiment-related words are identified by specific software, which automatically calculates their value in a broad context. For this reason, sentiment analysis is exclusively quantitative and is therefore an ideal method for efficiently processing a large volume of text.

Data and methods

Corpus construction

To compile the datasets for this study, we searched the LexisNexis database for the news reports about China published by The New York Times. We used “China,” “Sino,” and “Chinese” as search terms and ranked search results according to “Relevance” (a LexisNexis-supplied filtering criterion) to extract news articles published year after subsequent year until their content became obviously tangential to the subject. To ensure that our data fell under the category of “news report” (i.e., “hard news”), articles with “document type” tags such as Letter, Op-ed, News Analysis, and Editorial (available through LexisNexis) were deleted manually. Then, guided by the theory of news framing proposed by Entman (1993), we discarded news reports that were thematically less pertinent. According to Entman (1993), the coherent construction of a news event typically involves four components: problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and treatment or recommendation. Additionally, news articles containing at least two of these four elements can be considered related to a particular topic (Wang, 2018). Next came the process of data cleaning, when we manually removed data irrelevant to our analysis, such as publication date, by-lines, and copyright information.

The corpora for this study cover the 41-year period from 1980 to 2020. Search results indicated that the first news article directly related to our study’s objective was published by The New York Times in 1980, and the current full year at the time of data collection was 2020.

To carefully examine the use of the political keyword “stability” in the datasets, we roughly divided the time periods into four mainly based on the social development of China, and in particular, China-US relations (Chen and Wang, 2022a, 2022b), for when it comes to the representation of a foreign country and foreign affairs, the positioning of a country’s mainstream media tend to be in congruent with the dominant ideologies in their home country (Cook, 1997; Seib, 1997). In Period 1 (1980–1990), China undertook modernization efforts after the 1978 start of the reform and opening up policy and established extensive cooperation with the US after the two countries normalized diplomatic relation in 1979, but this was later seriously damaged by the “Tiananmen Square incident” in 1989. Period 2 (1991–2000) was marked by China’s rapid economic progress and the end of the Cold War with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, which allowed the US to become the world’s sole superpower, thereby undermining to an extent the rationale for increasing cooperation between the two nations. Besides, this period witnessed China’s consistent domestic and foreign policies, the historic 1997 Hong Kong handover to China, and unprecedented efforts in international image building (Peng, 2004). During Period 3 (2001–2010), China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 and won the bid for hosting the 2008 Olympic Games. With its increasing integration into the world and rapid economic progress, China overtook Japan as the world’s second-largest economy in 2010. Moreover, as a result of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the US government viewed international terrorism as its primary threat, thereby providing China with a strategic opportunity to develop its own military power (He, 2016). Over Period 4 (2011–2020), China began to get involved in remarkedly more clashes with other countries, particularly with the US, as its economic and political influence continued to grow. The release of the Obama administration’s “pivot toward Asia” policy in 2011 signaled a major shift in the US’ strategy in the Asia-Pacific (Shambaugh, 2013), and following the initiation of the China-US trade disputes in 2018, frictions between the two countries became more intense (Tellis, 2020).

Table 1 displays general information about the corpora, which reveals, not surprisingly, a constant increase in the number of news reports on the subject of China and China-US relations.

Corpus annotation and analysis

To reveal the change in discourse practice over a long period of time in this study, we employed descriptive research, which incorporates both quantitative and qualitative methods. Having completed the initial process of data collection, the first step in our analysis was data annotation. Using the concordance and file view functions of AntConc 3.5.8 (Anthony, 2019), we categorized the term “stability” into three types based on its usage in co-text: Type (1), “stability” in non-quotations related to China (not annotated); Type (2), “stability” in quotations related to China (annotated as “stabilityI”); and Type (3), “stability” unrelated to China (annotated as “stabilityII”). We chose to exclude Type (2) from our analysis because a quotation represents the viewpoint of its source and not that of the journalist. And because the focus of this study is on how China is portrayed by The New York Times, we also excluded Type (3).

The data for raw frequency and standardized frequency are presented in Table 2, where a measured increase in standardized frequency and, most notably, an abrupt increase from Period 2 to Period 3 can be observed.

The second step in our analysis was to examine variations in journalistic perspective across the four time periods. To calculate text polarity at the sentence level and determine the sentiment values of each period’s news stories, we used the R Package “sentiment” software (Rinker, 2018). In this process, we utilized the 11,709-word Jockers & Rinker Lexicon because it takes into account valence shifters (i.e., negators, amplifiers, and intensifiers), de-amplifiers, and adversative conjunctions, and has been found to generate more accurate results (Naldi, 2019).

The third step consisted of generating the collocates of non-quotation “stability” pertaining to China in each period using the AntConc collocation function, which provides a statistically sound way to identify strong lexical associations. Although there are numerous methods for calculating collocation strength (e.g., Z-score, MI, and log-likelihood), we chose log-likelihood because it is sensitive to low-frequency words, albeit with some bias toward grammatical words (Baker, 2006). Considering this drawback, we chose to exclude collocates with little or no semantic meaning such as “the,” “a,” and “that” (grammar words included). To accomplish this, we used the R package ‘tidytext’ (Silge and Robinson, 2016), which includes a list of 1149 English stop words. To ensure the non-random occurrence of a collocate, we set the window span to five to the left and five to the right of the node, with a minimum frequency of three.

To determine how The New York Times used non-quotation “stability” to characterize China over specific periods of time, we limited our analysis to the strongest adjective and noun collocates because a pilot study revealed that the strongest adjective and noun collocates in the corpora occurred most frequently in collocations such as “social stability,” “political stability,” “economic stability,” “financial stability,” “stability and peace,” and “stability and prosperity.” Then, we extracted the sentences containing the node “stability” and its strong collocates and conducted polarity and sentiment analysis. General information about the selected sentences is presented in Table 3.

The fourth step was to perform a co-textual analysis of the sentences. Based on the results of sentiment analysis, we first classified the sentences as positive, neutral, or negative, then examined the themes of these three categories of sentences to determine the newspaper’s focus during specific time periods, and categorized these sentences into several types based on their themes. After that, a few sentence examples were selected and analyzed to form a clearer picture of how “stability” was used in the assembled corpora.

Findings

An overall view of sentiment toward China in each period

Because there were no more than six collocates in the first period and seven collocates in the second period, we selected seven collocates for further analysis in the third and fourth periods. Table 4 displays the most frequent noun and adjective collocates (per 10,000,000 words) for each time period. Log-likelihood scores are used to rank each collocate.

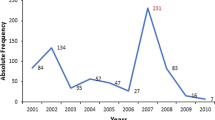

Table 4 shows that the word “political” appears in each period, indicating the keyword’s strong political connotation and the newspaper’s consistent emphasis on “political stability” regarding China-related issues. Further investigation of these instances in co-text indicates that “political stability” was associated with a variety of factors during distinct time periods. In Period 1, before and after the return of Hong Kong to China, the newspaper closely connected it to the “economic stability” and “prosperity” of “Hong Kong.” Periods 2 and 3 highlighted the Communist Party’s resolve and actions in fostering and preserving “political stability.” During Period 4, a great deal of focus was placed on the system of “stability maintenance” established and administered at all levels by the Chinese “government.” Fig. 1 depicts the sentiment value of non-quoted “stability” sentences pertaining to China and its significant collocates across the four time periods.

As shown in Fig. 1, Period 1 is the only period in which the sentiment value is positive (0.09), which may be explained by the relatively harmonious China-US relations that began in 1979 when the two nations agreed to recognize each other. In Period 2, the sentiment value (−0.19) fell to an all-time low, as social problems and human rights issues began to garner a great deal of attention after the 1989 “Tiananmen Square incident”. The sentiment value for Period 3 (−0.06) is a bit greater than that of the previous period (−0.04), although it is still negative, and the score for Period 4 (−0.02) also increases. The reasons for the changes will be explained in detail in the following sub-sections.

Table 5 demonstrates the distribution of sentiment polarity of the extracted sentences across the four time periods by displaying the number and percentage of each sentence type in each period.

Of all occurrences of the keyword “stability” in Table 4, 50.4 and 46.4% have positive and negative connotations, respectively, indicating that the term is likely to be used in either of these ways. In contrast, it is used infrequently in neutral contexts (3.2%). In addition, Period 2 displays a remarkable increase in negativity (Period 1: 31.6%; Period 2: 75%), followed by a modest decrease in Period 3 (50.1%), which is consistent with the trend shown in Fig. 1. Due to the very low percentage of neutral attitudes in the four periods and the word limit of this article, we chose to use only examples of positive and negative attitudes for the detailed analysis presented in the following section.

Detailed analysis of Period 1

Table 5 shows that in Period 1, 68.4% of the extracted sentences were used to represent positive sentiment toward China, primarily due to a focus on China’s economy, its contribution to regional development, and its contribution to world peace. On the other hand, 31.6% of the sentences contain negative connotations, reflecting concerns about political instability in China, the uncertain future of Hong Kong, and the “Tiananmen Square incident” of 1989. Although the Chinese government defined the Tiananmen Square incident as a “political disturbance” (Xinhua News Agency, 2006), it marked a turning point in the West’s perception of Chinese authorities (Schoenhals, 1999). Furthermore, as indicated by Extract (2) below, the newspaper believed that uncertainty about China’s political stability would negatively affect the country’s economic stability. We chose the following two extracts to illustrate positive and negative sentiment, respectively:

-

(1)

The improvement of relations between Japan, China, and the United States, by helping to assure political stability in the region, seems to have laid a foundation for a great East Asia offshore oil boom in the 1980’s. (“Oil riches off China’s shores,” January 19, 1982; sentiment value: 0.5014169)

-

(2)

Signaling uncertainty about China’s political stability, Moody’s Investors Service Inc. today downgraded the country’s long-term credit rating. (“China’s credit rating downgraded by Moody’s,” November 10, 1989; sentiment value: −0.2529822)

In Extract (1), the newspaper emphasizes the significance of relations between its native country (the United States) and two East Asian nations (China and Japan) and describes the economic benefits of political stability in East Asia (an oil boom). From the perspective of The New York Times, the US, as an ally of Japan and a third party involved in the Sino-Japan Diaoyu Islands dispute (Wang, 2017), was an outsider regarding oil drilling in the East China Sea and foreign affairs relating to Japan. The implicit nomination strategy employed by The New York Times here legitimates the US’s appearance in this utterance. It is clear that this perspective is largely US-centric given the fact that the US is not an East Asian country.

In contrast, Extract (2) illustrates how “the Tiananmen Square incident” resulted in increased Western skepticism regarding China’s political stability, which eventually led to severe economic repercussions, including the downgrading of China’s long-term credit rating. The newspaper implied that “the uncertainty of China’s political stability” was the cause of this downgrading, nevertheless, it employed the strategy of prediction through the use of “signaling uncertainty about …” and “downgraded the country’s …”, which highlights the simultaneity of the two actions and weakens the cause-and-effect relationship between them. In this way, this piece of message seems to be more objectively presented, though the negative facet of China is communicated to the audience as well.

Detailed analysis of Period 2

In Period 2, positive sentiment (25%) is associated with China’s contribution to stability in Asia and international stability, as exemplified by Extract (3), which suggests that the newspaper was well aware of China’s growing significance in the international community. In contrast, the majority of sentences (75%) demonstrate a negative sentiment that is based on three primary aspects: (1) social problems: the threat of rising unemployment to China’s social stability; (2) human rights and religions: the outlawing of Falun Gong, arresting dissidents, and tightening the reins on writers and publishers, as illustrated by Extract (4); and (3) power shift: maintaining the nation’s stability following the death of Deng Xiaoping on February 19, 1997.

-

(3)

Even though it was a Cold War instrument that put Beijing and Washington in a common cause against Soviet expansion, the Shanghai Communique ushered in the longest period of Asian peace and stability in this century and made it possible for Asia’s vibrant new economies to emerge. (“The China-and-Taiwan problem: How politics torpedoed Asian calm,” February 11, 1996; sentiment value: 0.1916745)

-

(4)

Their [The current Chinese leaders’] notion of stability means stamping out any threats to the rule of the Communist Party, which leads them to imprison advocates of democracy despite international criticism. (“Volatile issues await China’s Premier in the US,” April 4, 1999; sentiment value: −0.2598076)

In Extract (3), the newspaper describes how strengthening China-US relations has contributed to peace and stability in Asia. The use of the superlative adjective “longest” to emphasize the positive effects of the Shanghai communique between China and the US is noteworthy. The predicational strategy “ushered in the longest period of…” highlights the contribution of the US in maintaining peace and stability in Asia and promoting the economic development of the region.

In Extract (4), the statement demonstrates The New York Times’ basic understanding of stability in Chinese contexts by employing the predicational strategy “means stamping out any threats to the rule of the Communist Party”. The newspaper defined stability as the CPC’s instrument of dominance in a direct manner. In addition, the report criticized the CPC’s imprisonment of dissidents and highlighted international criticism of this practice in the non-restrictive attributive clause introduced by “which”.

Detailed analysis of Period 3

Due to China’s contribution to the 2007–2008 financial crisis, its financial stability became salient during this period. As shown in Table 5, 40.4% of instances convey a positive sentiment toward China, primarily regarding its booming economy, financial management, and maintenance of social stability, as illustrated in Extract (5), whereas 50.1% of instances of “stability” denote negative aspects of China, covering a wide range of political and diplomatic issues as well as social problems, such as press freedom, territorial disputes, corruption, a widening wealth gap, etc. We chose Extract (6) to illustrate the newspaper’s portrayal of the democratic rights of the Chinese people.

-

(5)

China also needs to show long-term economic and financial stability—something it has demonstrated over the past year in greater abundance than most countries. (“In step to enhance currency, China allows its use in some foreign payments,” 7 July 2009; sentiment value: 0.346)

-

(6)

Beijing, which enforces a strict code of social stability, almost never gives permission for protesters to march on the streets of the capital. (“Riot police called in to calm Anti-Japanese protests in China,” 10 April 2005; sentiment value: −0.09174634)

In the phrase following the dash in Extract (5), China is compared to other nations in terms of economic and financial stability, and the positive evaluative adjective “abundance” is used to convey this comparison. This suggests that the newspaper had at this point acknowledged China’s economic and financial strength. What is worthy of equal note is the predicational strategy “needs to show long-term economic and financial stability” utilized to portray “China”, which “needs to” suggest the obligation of the country (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004, p. 147) is totally presented from the perspective of The New York Times.

Extract 6 highlights the Chinese government’s ban on its citizens parading through the streets of Beijing. Such conduct was fiercely condemned by The New York Times through the use of the predicational strategy in the non-restrictive clause following “Beijing”. This strategy is mainly realized by the verb “enforces”, which suggests that Chinese authorities exercised top-down government power. Additionally, the newspaper’s use of the adjective “strict” and the full-negation adverb “never” enhances the negative tone.

Detailed analysis of Period 4

In Period 4, the percentages of positive and negative sentiment are 58.2 and 38.4%, respectively. However, as stated previously, the sentiment value of the extracted sentences remains negative, despite the fact that the number of positive sentiment sentences exceeds the number of negative sentiment sentences. Similar to Period 3, the positive sentences relate to China’s economy and financial management, as illustrated in Extract (7). In contrast, the newspaper’s negative sentiment focuses on a number of sociopolitical issues, such as cybersecurity, COVID-19, and social unrest in Hong Kong, among others, as evidenced in Extract (8).

-

(7)

But even some vocal naysayers say the country has found ways to contain its problems—at least for now. That improving outlook is, in part, reflected in China’s currency. The renminbi has surged in value in recent weeks, helped by growing confidence in the country’s economic prospects and by a political push for stability. (“Amid optimism, China’s currency rises,” 12 September 2017; sentiment value: 0.54)

-

(8)

Apparently unnerved by an anonymous Internet campaign urging Chinese citizens to emulate the protests that have rocked the Middle East, Chinese authorities this week have begun a forceful and carefully focused clampdown on activities by foreigners that the government deems threatening to political stability. (“Wary of fueling protests, China adds new limits on foreigners,” 4 March 2011; sentiment value: −0.305596)

In Extract (7), the newspaper depicts political stability in China and the positive influence of political stability on the country’s economic development, as evidenced by the appreciation of the country’s currency, the renminbi (RMB). The newspaper employed the strategy of predication to describe “renminbi”, and its positive attitude toward its surge in value is strengthened by “-ed” phrase following it.

In contrast, Extract (8) illustrates the Chinese government’s alertness to issues related to political stability, as well as its firm resolve to take swift action whenever necessary to safeguard it. The New York Times used the strategy of prediction “have begun a forceful and carefully focused clampdown” to depict “Chinese authorities” and portrayed Chinese authorities as a negative agent, implying its critical attitude toward measures taken by the Chinese government in response to “an anonymous Internet campaign urging Chinese citizens to emulate the protests that have rocked the Middle East.” In addition, it is evident that the newspaper compares China to some Middle Eastern nations.

Discussion and conclusion

The preceding diachronic analysis demonstrates that The New York Times tended to define the political keyword “stability” with reference to China in a negative light and relate it to various sociopolitical and territorial issues, while positively portraying China’s economic and financial progress and contribution to the world peace to a relatively limited extent mainly through the use of the strategies of nomination and predication. These findings are consistent with Peng’s (2004) analysis of news reporting on China by The New York Times and Los Angeles Times between 1992 and 2001, which revealed that the two newspapers framed China-related issues negatively on the political and ideological fronts, but positively on the economic front. Therefore, it is fair to conclude that the dominant ideologies pertaining to China in the US mainstream media have changed very little, if at all, over the past few decades.

The newspaper’s perspective on China’s stability is predominately political and US-centric. The definition of “stability” in China presented in Extract (4) reveals the prevalent understanding in the US that stability means maintaining the CPC’s rule in China, which is thus antithetical to democracy. This definition may explain the newspaper’s negative depiction of various sociopolitical issues in China such as unemployment, suppression of people’s freedom of expression, aggressive actions in East China Sea disputes, control of Hong Kong, etc. Several other studies have identified the same trend. For instance, casting the United States as a third party between China and Japan and an ally of Japan, the US media framed the disputes as being triggered by rising nationalism in both China and Japan, highlighting the military threat in the Asia-Pacific region (Nathan and Scobell, 2012; Ross, 2012) and justifying US intervention in territorial disputes outside its borders (Wang, 2017).

In addition, the shift from a generally positive China image in the 1980s to a negative China image afterward, as viewed through sentiment analysis of non-quotation “stability,” is generally in agreement with the major aspects of US-China relations and the changing US foreign policy over the past four decades (Chang, 1988). From the angle of the US, the evolving bilateral relationship between the US and China is an issue with complex political, economic, and security dimensions (Medeiros, 2019).

In 1979, when the two nations established a formal diplomatic relationship, they strengthened their diplomatic and economic ties (Kang, 2007; Kurlantzick, 2007). At the time, the Western world viewed China as “a harbinger of the liberalization of the entire Communist world” (Madsen, 1995, ix) and a “troubled modernizer” (i.e., a country that modernized itself and gradually liberalized its economy and politics), but they were disillusioned by the 1989 incident and no longer hoped to westernize China politically and ideologically (Madsen, 1995, pp. 28–29). The persistent ideological divergence between China and the United States is evident in numerous examples of negative sentiment regarding sociopolitical issues (including religions and human rights), particularly in the 1990s, although China was integrated into the post-Cold War order after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 (Nacht et al. 2018, p. 1). Despite a “constructive strategic partnership” sought by the Clinton administration, China was portrayed as an ideological and political “other” by The New York Times.

The trend of othering China politically and ideologically continued throughout the following two periods, and this may explain why the overall sentiment value of the sentences containing the political keyword “stability” in non-quotations remains negative in both periods. Since the presidency of George W. Bush between 2001 and 2009, China has been viewed as a rising challenger and strategic competitor of the US (Tellis, 2020), although it was assumed by some Americans that by drawing China into the World Trade Organization (WTO) and promoting China’s economic growth, China’s political system could be westernized (Lukin, 2019, pp. 23–24). After the September 11 attacks in 2001, on the one hand, the Bush administration intended to engage China to address the escalating regional and global terrorist problem together; on the other hand, US companies desired to profit from China’s enormous market, preferable foreign investment policies, and low-cost workforce. However, the US government was vigilant about China’s growing economic and military power, not to mention its political presence in the world.

In the 2010s, China–US relations became worse in many aspects, especially in terms of economic cooperation, and political distrust toward China grew, although the commitment to working with China in areas of shared interest was clearly expressed by the US government, such as North Korean nuclear proliferation (Nacht et al. 2018, p. 1). After China emerged as the world’s second-largest economy, the Asia-Pacific Rebalancing Strategy was proposed by the Obama administration in 2012, which was interpreted as “prominently a military posture aimed at countering increased Chinese assertiveness” (Nacht et al. 2018, p. 1). In the meantime, those who used to advocate for cooperation with China were gradually aware that China failed to fully open its market to foreign investors and continued with forced technology transfer. They also realized it was impossible for China to be transformed into a Western-style democracy when they were informed (mainly by the national news outlets, for example, The New York Times) of social unrest in Hong Kong and cyber censorship in China’s mainland. Consequently, the majority coalition of interest groups in the US increasingly embraced protectionism and nationalism as their guiding ideologies in tackling China, which was later strengthened by the “America First” policy when Donald J. Trump took office. In early 2018, the two biggest economies were embroiled in a full-blown trade dispute (Swenson and Woo, 2019).

In conclusion, drawing on the approaches of CDA and sentiment analysis, this study closely examines the use of non-quotation “stability” in relation to China by The New York Times between 1980 and 2020. It contributes to the existing literature by addressing how a political keyword such as “stability” is used in news reports published by the preeminent newspaper of a country that is ideologically distinct from China, and how the intentional use of such a keyword contributes to the construction of a country’s national image.

In addition, this study represents a substantial contribution to the limited literature on the application of sentiment analysis to CDA and news discourse analysis. In our investigation, this method proved to be time-efficient, verifiable and well-suited to accurately measure the positivity and negativity of sentiments expressed in news discourse. Our future study will utilize this method to compare and examine several large groups of news texts in different periods to uncover hidden sociopolitical factors in them.

However, despite our best efforts to be as objective as possible in the selection of data, some researcher subjectivity may have entered into our classification of three categories of “stability” and our method of sentence analysis. In addition, while we utilized cross-domain lexicons to conduct sentiment analysis, this method did not allow us to identify all semantic features that are distinct and important in a given text or dataset, due to the fact that language usage varies significantly across domains and contexts. As such, future studies could develop specialized lexicons to dig out sentiment features peculiar to news discourse.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available at https://pan.baidu.com/s/1CoovUawUQzLc2tGx7KiXbg?pwd=amea.

References

Anthony L (2019) AntConc, Version 3.5.8. Waseda University. Available from https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software

Baker P (2006) Using corpora in discourse analysis. Continuum, London

Baker P, Gabrielatos C, Khosravinik M et al. (2008) A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press. Discourse Soc 19(3):273–306

Banwo A (2015) Inherent nature & dynamics of political stability in China. Fudan J Hum Soc Sci 8:291–311

Chang T (1988) The news and US-China policy: symbols in newspapers and documents. J Mass Commun Q 65(2):320–327

Chen F, Wang G (2022a) A war or merely friction? Examining news reports on the current Sino-US trade dispute in The New York Times and China Daily. Crit Discourse Stud 19(1):1–18

Chen F, Wang G (2022b) A social network approach to critical discourse studies. Digit Scholarsh Hum. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqac085

Chung A, Jo H, Lee L, Yang F (2021) COVID-19 and the political framing of China, nationalism, and borders in the US and South Korean news media. Social Perspect 64(5):747–764

Cook T (1997) Governing with the news: the news media as a political institution. University of Chicago University, Chicago

D’Andrea A, Ferri F, Grifoni P et al. (2015) Approaches, tools and applications for sentiment analysis implementation. Int J Comput Appl 125:26–33

Deng X (1994) The United States should take the initiative in putting an end to the strains in Sino-American Relations. In: Editorial Committee for Party Literature (eds) Selected works of Deng Xiaoping, vol 3, Foreign Languages Press, Beijing, pp 320–322

Ding X, Liu B, Yu PS (2008) A holistic lexicon-based approach to opinion mining. In: Proceedings of the 2008 international conference on web search and web data mining. ACM Press, New York. pp 231–240

Entman R (1993) Framing: towards clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun 43(4):51–58

Fairclough N (1992) Discourse and social change: the critical study of language. Polity Press, Cambridge

Feldman R (2013) Techniques and applications for sentiment analysis. Commun ACM 56(4):82–89

Fowler R (1991) Language in the news: discourse and ideology in the press. Routledge, London

Halliday MAK, Matthiessen C (2004) An introduction to functional grammar. Hodder Arnold, London

Hardt-Mautner G (1995) “Only connect.” Critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics. UCREL Technical Paper 6, Lancaster

He K (2016) Explaining United States-China relations: neoclassical realism and the nexus of threat–interest perceptions. Pac Rev 30:1–19

Kang D (2007) China rising: peace, power, and order in East Asia. Columbia University Press, New York

Kim SM, Hovy E (2004) Determining the sentiment of opinions. In: Proceedings of the 20th international conference on computational linguistics – COLING’04, Morristown, NJ, 23–27 August 2004

Kotzé E, Senekal B (2018) Employing sentiment analysis for gauging perceptions of minorities in multicultural societies: an analysis of Twitter feeds on the Afrikaner community of Orania in South Africa. J Transdiscipl Re 14(1):1–11

Kurlantzick J (2007) Charm offensive: how China’s soft power is transforming the world. Yale University Press, New Haven

Lei L, Liu D (2021) Conducting sentiment analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Liebman B (2014) Legal reform: China’s law-stability paradox. Daedalus 143(2):96–109

Liss A (2003) Images of China in the American print media: a survey from 2000 to 2002. J Contemp China 12(35):299–318

Liu M (2015) Scapegoat or manipulated victim? Metaphorical representations of the Sino-US currency dispute in Chinese and American financial news. Text Talk 35(3):337–357

Liu M (2017) Contesting the cynicism of neoliberalism: a corpus-assisted discourse study of press representations of the Sino-US currency dispute. J Lang Polit 16(2):242–263

Love R, Baker P (2015) The hate that dare not speak its name? J Lang Aggress Confl 3(1):57–86

Lukin A (2019) The US-China trade war and China’s strategic future. Survival 61(1):23–50

Nacht M, Laderman S, Beeston J (2018) Strategic competition in China-US relations. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, California, https://cgsr.llnl.gov/content/assets/docs/CGSR-LivermorePaper5.pdf

Naldi M (2019) A review of sentiment computation methods with R packages. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1901.08319

Nasim Z, Rajput Q, Haider S (2017) Sentiment analysis of student feedback using machine learning and lexicon based approaches. Paper presented at International Conference on Research and Innovation in Information Systems (ICRIIS), Langkawi, Malaysia, 16–17 July 2017

Madsen R (1995) China and the American dream: a moral inquiry. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles

Martin JR, White PRR (2005) The language of evaluation: appraisal in English. Palgrave/Macmillan, London and New York

Medeiros ES (2019) The changing fundamentals of US-China relations. The Washington Quart 42(3):93–119

Moyo L (2010) The global citizen and the international media: a comparative analysis of CNN and Xinhua’s coverage of the Tibetan crisis. Int Commun Gaz 72(2):191–207

Nathan A, Scobell A (2012) How China sees America. Foreign Aff 91(5):32–47

Partington A (2012) Corpus analysis of political language. In: Chapelle C (ed.) The encyclopedia of applied linguistics. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, p 1299–1307

Peng Z (2004) Representation of China: an across time analysis of coverage in The New York Times and Los Angeles Times. Asian J Commun 14(1):53–67

Reisigl M, Wodak R (2009) The discourse-historical approach (DHA). In: Wodak R, Meyer M (eds.) Methods of critical discourse analysis, 2nd edn. Sage, New Delhi, p 87–121

Rinker T (2018) Sentimentr: dictionary based sentiment analysis that considers valence shifters (Version 2.6.1). Available from https://github.com/trinker/sentimentr

Ross R (2012) The problem with the Pivot–Obama’s new Asia policy is unnecessary and counterproductive. Foreign Aff 91(6):70–82

Sandby-Thomas P (2014) “Stability overwhelms everything”: analysing the legitimating effect of discourses of stability since 1989. In: Cao Q, Tian H, Chilton P (eds) Discourse, politics and media in contemporary China. John Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, p 47–76

Schoenhals M (1999) Political movements, change and stability: the Chinese Communist Party in power. China Quart 159:595–605

Seib P (1997) Headline diplomacy: how news coverage affects foreign policy. Praegar, Westport

Silge J, Robinson D (2016) Tidytext: text mining and analysis using tidy data principles in R. J Open Source Softw 1(3):37

Sinclair J (1991) Corpus concordance collocation. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Sinclair J (2004) Trust the text: language, corpus and discourse. Routledge, London

Shambaugh D (2013) Assessing the US “Pivot” to Asia. Strateg Stud Quart 7(2):10–19

Smirnova A, Laranetto H, Kolenda N (2017) Ideology through sentiment analysis: a changing perspective on Russia and Islam in NYT. Discourse Commun 11(3):296–313

Swenson D, Woo W (2019) The politics and economics of the US-China trade war. Asian Econ Pap 18(3):1–28

Syed N (2010) The effect of Beijing 2008 on China’s Image in the United States: a Study of US media and polls. Int J Hist Sport 27(16–18):2863–2892

Taboada M, Brooke J, Tofiloski M et al. (2011) Lexicon-based methods for sentiment analysis. Comput Linguist 37(2):267–307

Tang L (2021) Transitive representations of China’s image in the US mainstream newspapers: a corpus-based critical discourse analysis. Journalism 22(3):804–820

Taufek TE, Fariza N, Jaludin A et al. (2021) Public perceptions on climate change: a Sentiment analysis approach. Gema Online J Lang S 21(4):209–233

Tellis A (2020) US–China competition for global influence. In: Tellis A, Szalwinski A, Wills M (eds) Strategic Asia 2020: US-China competition for global influence. The National Bureau of Asian Research, Seattle, pp 1–43

Turney PD (2002) Thumbs up or thumbs down? Semantic orientation applied to unsupervised classification of reviews. In: Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL ‘02), Philadelphia, Philadelphia, pp 417–424

van Dijk TA (1988) News analysis: case studies of international and national news in the press. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale

van Dijk TA (2009) News, discourse, and ideology. In: Wahl-Jorgensen K, Hanitzsch T (eds.) The handbook of journalism studies. Routledge, New York, p 191–204

Vargas-Sierra C, Orts M. Á (2023) Sentiment and emotion in financial journalism: a corpus-based, cross-linguistic analysis of the effects of COVID. Hum Soc Sci Commun. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01725-8

Wang G (2017) Discursive construction of territorial disputes: foreign newspaper reporting on the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands dispute. Soc Semiot 27(5):567–585

Wang G (2018) A corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis of news reporting on China’s air pollution in the official Chinese English-language press. Discourse Commun 12(6):645–662

Wang G, Ma X (2021) Were they illegal rioters or pro-democracy protestors? Examining the 2019‒20 Hong Kong protests in China Daily and The New York Times. Crit Arts 35(2):85–99

Wang G, Wu X, Li Q (2022) A bibliometric study of news discourse analysis (1988‒2020). Discourse Commun 16(1):110–128

Wang M (1991) Who is dominating whose ideology? New York Times reporting on China. Asian J Commun 2(1):51–69

Wicke P, Bolognesi M (2021) Covid-19 discourse on Twitter: how the topics, sentiments, subjectivity, and figurative frames changed over time. Front Commun 6:1–20

Wodak R (1996) The genesis of racist discourse in Austria since 1989. In: Coulthard CR, Coulthard M eds) Texts and practices. Routledge, New York, p 107–128

Xinhua News Agency (2006) China blasts US statement on “Tiananmen Incident.” http://www.Chinadaily.com.cn/China/2006-06/07/content_610618.htm

Yan W (1998) A structural analysis of the changing image of China in the New York Times from 1949 through 1988. Qual Quant 32(1):47–62

Yu J (2014) Shifting from “rigid stability” to “resilient stability.”. Contemp Chin Thought 46(1):85–91

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Major Project of the National Social Science Fund of China under Grant 20&ZD140 and the Shanghai Social Science Planning Project (General Project) under Grant 2020BYY003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guofeng Wang and Yilin Liu contributed to research design, methodology, data collection, analysis, and writing and editing. Shengmeng Tu contributed to data collection and part of the analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, G., Liu, Y. & Tu, S. Discursive use of stability in New York Times’ coverage of China: a sentiment analysis approach. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 666 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02165-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02165-0