Abstract

COVID-19 and its control measures remain contested issues in literature. While some of the literature views COVID-19 and its responses as neutral events serving the common good, other parts of the literature considers them partial events serving personal interests. This study analyses the political economy of COVID-19 in East Africa by assessing how COVID-19 and its control affected public and private policy actors and how the actors responded to them. Based on a systematic review, the study found that the pandemic and its control generated political and economic opportunities and contestations. Politically, COVID-19 and its control measures presented opportunities to suppress and oppress opposition, conduct political campaigns, provide patronage, and conduct selective enforcement. Economically, the pandemic and its responses presented opportunities to generate income and benefits for the government and its employees, businesses, and ordinary citizens. However, these opportunities were exploited to serve personal political and economic interests. COVID-19 responses also generated a lot of discontent, leading to contestations from many policy actors. The actors contested COVID-19 vaccines and science, role allocation during the response, selective enforcement of COVID-19 directives, corruption in relief provision, and the brutality of security forces. The contestations and pursuit of personal political and economic interests compromised the effectiveness of the COVID-19 response.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since its detection in China in 2019, the coronavirus (COVID-19) rapidly spread to all countries where it infected and killed a large number of people. By 7th March 2023, COVID-19 had already infected 759,408,703 people and killed 6,866,434 of them globally (WHO, 2023). Many countries responded to the pandemic with stringent public health measures. However, COVID-19 and its control measures became issues of contestation. While the responses to the pandemic emerged as technical and supposedly neutral recommendations from experts upon whom politicians and the media rely for technical solutions for public health, some politicians contradicted and contested the technical recommendations (Lavazza and Farina 2020).

COVID-19 and its technical control measures were distorted and contested by disinformation. Official disinformation campaigns came from four categories of governments: denialists (Nicaragua, Tanzania, and Burundi), anti-scientists (Belarus, Brazil, Mexico, United States, Serbia), and curists (Algeria, Benin, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, DRC, Gabon, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Senegal, Togo, Turkey, Venezuela) (Lührmann et al. 2020). For Lührmann et al., denialists openly denied the existence of Covid-19 in their country or initially reported cases, but later claimed little to no active spread of the virus contrary to evidence; anti-scientists downplayed the dangers of COVID-19 while questioning accepted scientific evidence and recommendations by the WHO or other health authorities and; curists supported unsubstantiated treatments for COVID-19, including hydroxychloroquine, alcohol, saunas, herbal tonic named COVID-Organics and herbal tea. The curists also include governments that claimed cures from God. Some governments fall into more than one category of disinformation. Technical and neutral COVID-19 responses have also been politicized by political tribalism (Druckman et al. 2021; Adolph et al. 2021; Gollwitzer et al. 2020). Disinterested government officials were believed to have implemented COVID-19 policy based on the omniscient advice of health, epidemiological, and economic science, that efficiently promote overall well-being, but governments in the United States and around the world made significant errors in their COVID-19 policy response (Boettke and Powell 2021).

COVID-19 and its responses were also subjects of contestation in Africa. The literature largely views the responses as technical, neutral, and harmonised solutions serving the public interest. This follows from leading roles played by technical agencies such as World Health Organisations (WHO), Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), and West African Health Organization (WAHO) and the partnership created in the continent-wide COVID-19 response. An African COVID Task Force consisting of Africa CDC, AU Member States and partners such as WHO led the implementation of a continental response strategy that harnessed and leveraged the continental expertise through technical working groups, which reviewed the latest evidence and best practices, and adapted them into policies and technical recommendations to inform public-health action against COVID-19 and to foster coordinated preparedness and response across Africa (Massinga-Loembé et al., 2020). The effective and harmonised responses were attributed to Africa’s experiences with overlapping health crises such as cholera and Ebola (Patterson and Balogun, 2021). For example, Patterson and Balogun associated Uganda’s experience of Ebola with the swift and comprehensive COVID-19 response including high levels of testing, aggressive contact tracing, curfew and closure of public spaces.

However, other literature reports contestations and heterogeneity among players as well as politicisation and exploitation of COVID-19 response for personal interests. While regional organisations such as WAHO and Africa CDC adopted and promoted science-based COVID-19 response, Madagascar promoted a herbal COVID-19 treatment (COVID-Organics-CVO) alleged to have cured 105 COVID-19 patients (Patterson and Balogun, 2021). Although WHO warned African countries against using or relying on CVO (Patterson and Balogun, 2021), the Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, and Equatorial Guinea purchased the remedy (Africa News 2020). Tanzania also pursued its own COVID-19 response path as it established limited lockdown, supported a herbal treatment (CVO), contested the reporting norms for COVID-19 cases, and shun WHO, regional cooperation meetings of the East African Community and Southern African Development Community for developing a coordinated pandemic response (Houttuin and Bastmeijer, 2020; Kiruga, 2020; Patterson and Balogun, 2021; Mutalemwa, 2021). While WHO and donors credited Uganda for the swift and comprehensive COVID-19 response, it was criticized for the lack of civil society input in the response and the heavy-handed approach to policing behaviour (Lirri, 2020; Patterson and Balogun, 2021). Chidume et al. (2021) also found enthnicisation, regionalisation, and mismanagement of government social support funds and protest of COVID-19 containment measures by religious groups in Nigeria. Patterson and Balogun also reported the exploitation of the pandemic by some leaders to consolidate their power and regimes.

This paper extends the debates about COVID-19 responses from the global and continental to regional and national levels by analysing the political economy of COVID-19 in East Africa using a systematic review. In this paper, the political economy of COVID-19 denotes interrelationships between politics and COVID-19 effects (health, economic, social, or political effects) and responses. Politics is conceptualized as conflicts (of interest and values or beliefs), debates, negotiations, and cooperation or agreements over the use and distribution of economic and political resources that involve two or more people, organizations, families, communities, regions, and countries. East Africa refers to the seven members of the East African Community, namely: Burundi, DR Congo, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda.

The understanding of COVID-19 responses in the region has been limited by two main reasons. Firstly, most studies of COVID-19 responses in East Africa have been narrow in scope. The studies prioritized government responses and neglected responses of other actors as they focused mainly on the effects of government responses such as lockdowns and restrictions. Notably, the studies assessed how the responses affected tourism (Ezra et al., 2021), livelihoods (Mutua et al. 2021, Kansiime et al. 2021; Nchanji and Lutomia, 2021), production and trade (Amutabi 2022; Nchanji et al. 2021; Morton 2020), and human rights (Okech et al. 2020). They also analysed the effects and challenges of border restriction policies during the COVID-19 crisis (Barack and Munga, 2021; Gachohi et al. 2020) and funding sources for the COVID-19 response (Mukova, 2023). While Africa’s responses to COVID-19 were situated in political economy discourse (Matamanda et al. 2022), most studies of the pandemics’ responses in East Africa were void of political economy analysis. This is because the studies analysed the effects of COVID-19 responses without scrutinising the political economy factors and drivers of the responses, namely: interests, incentives, power, values, and ideas of actors as well as institutions and structures. For example, Okech et al. assessed only the human rights effects of the COVID-19 response, but not the interests and incentives driving human rights violations. Mukova presented funders of the COVID-19 response as having public interests and ignored the private interests that some donors such as politicians and companies inhabited. Similarly, Barack and Munga considered COVID-19-related border restriction policies as neutral and technical responses, yet Nasubo et al. (2022) attribute much of these restrictions to the pursuit of national interests other than COVID-19 control. Even the political analyses of COVID-19 responses in the continent were largely conducted outside East Africa, notably, the studies of interrelationships between COVID-19 responses and informal urban governance in Nigeria(Onyishi et al. 2022), religious prevarications and state fragility in Nigeria (Chidume et al. 2021), politics, policy, and inequalities in South Africa (Francis et al. 2020; Phiri, 2021), the collective contestation of COVID-19 lockdown measures by the historically, spatially, economically and socially marginalised urban working class in Ghana (Boateng et al., 2022) and vested interests in COVID-19 responses Lesotho, South Africa, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe (Matamanda et al. 2022).

Secondly, the understanding of the political economy of COVID-19 responses has been limited by diverse contexts. The political economy of any event varies across contexts. For example, COVID-19 responses inflicted much more human rights abuses in the Global South than in the Global North (Uddin et al. 2022). COVID-19 reduced armed conflicts in some countries but led to increased conflicts in other nations (Ide 2021). COVID-19 responses varied in humanitarian and non-humanitarian settings (Singh et al. 2020). While COVID-19 control measures such as lockdown and contact tracing were more stringent under autocratic governments, they were less stringent under democratic governments (Frey et al. 2020). This implies that the political economy of COVID-19 is still less understood because many contexts remain unexplored. Equally, it means that the understanding of the political economy of COVID-19 in East Africa is still limited. This is because the pandemic emerged in Sub-Saharan Africa under diverse contexts characterized by endemic problems of political instability, human rights violations, corruption, conflicts, humanitarian crises, unfair electoral processes, and weak governance (Agwanda et al. 2021).

In this paper, the breadth of political economy analysis was mainly limited to the interests of actors and countries with heightened political activities, leaving the power and ideas of actors as well as institutions at the periphery of the paper. Here, actors refer to COVID-19 policy actors. Knoepfel et al. (2011) define policy actors as political-administrative entities invested with public authority to develop and implement policies to solve a problem and socio-economic entities whose aims and interests are affected by the policy. The paper, therefore, sought an understanding of how COVID-19 and its responses affected and were affected by COVID-19 policy actors and their interests under the contexts of heightened political activities in Burundi, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. In Kenya, the COVID-19 pandemic emerged at a critical time when the country was engaged in a national dialogue of confronting its conflict-dominated past through the Building Bridges Initiative (Ogenga and Baraza, 2020). The pandemic stroked Burundi, Tanzania, and Uganda during the election period (Patterson 2022; Chamegere 2021; Saleh 2020; Obi and Kabandula 2021).

While responses to health emergencies are intertwined with political circumstances (Jung et al. 2021), interrelationships between COVID-19 responses and elections in East Africa have not been comprehensively studied. For example, Nakkazi (2020), Patterson (2022), and Baguzi (2021) reported controversial political decisions and activities of COVID-19 responses in East Africa, but they did not situate these decisions and activities in the election contexts. Although some studies were anchored in the election context, their geographical scopes were limited as they largely covered one country, notably: political branding strategies by Tanzanian politicians during the covid-19 pandemic (Mulinda, 2021), the exploitation of masks by government leaders, opposition parties and citizens for political messaging and defiance in Uganda (Anguyo 2020a, 2020b) and the politicization of the urban relief distribution in Uganda ahead of the 2021 presidential, parliamentary and local elections (Macdonald and Owor 2020).

This paper, therefore, makes two contributions to literature. Firstly, the application of political economy analysis broadens the understanding of COVID-19 responses in East Africa in particular and Sub-Saharan Africa in general because it provides a broader perspective. Secondly, the paper particularly broadens the understanding of the COVID-19 response in a politicized environment.

The paper advanced two arguments. Firstly, COVID-19 and its control measures affected actors positively and negatively. This is because disasters can trigger conflicts and reinforce pre-disaster injustices, but they can also generate opportunities for conflict resolution and sustainable change (Renner and Chafe 2007; Brundiers 2018). Secondly, the responses of actors to COVID-19 and its control measures are not only neutral and technical solutions serving the common good but also partial and contested events driven by political and economic interests. This follows from three main observations. First, pandemics occur in political spaces characterised by contestations and conflicts as the spaces have the market, state, and civil society actors with varying motivations and rules of the game (Matamanda et al. 2022; Bowles and Carlin 2021). Second, responses to pandemics involve many contradictions, conflict, and negotiations (Bankoff and Hilhorst 2009). Third, preparedness for and response to pandemics are profoundly shaped by geopolitical processes and by formal, hybrid, and informal public authorities on the ground (Parker et al. 2020). Disaster reliefs from governments are prone to political influences, which Kumar (2016) attributes to legislative bargaining between coalition members and tactical redistribution. Tactical redistribution is the incumbent government’s ability to buy votes by distributing money or benefits to regions with many floating voters (Dixit and Londregan 1996). Crises are also prone to opportunistic oppression (Seewald 2020). This is a situation where ‘policymakers take advantage of a crisis to pursue pre-existing and often unrelated policy preferences’ (Birdsall and Sanders 2022:1). The subsequent sections of the paper cover COVID-19 and the political situation in East Africa, the analytical framework, methods, data, results, discussion, and conclusion.

COVID-19 and political situation in East Africa

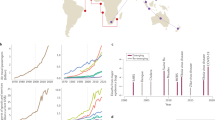

East Africa has not been an exception to the COVID-19 pandemic. Burundi, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda reported initial cases of COVID-19 in March 2020 (Walwa 2023; Liaga et al. 2020). Since then, the virus has infected and killed many people. By 7th March 2023, WHO had reported infection of 54,142 people in Burundi,342,932 people in Kenya, 42,846 individuals in Tanzania and 170,409 people in Uganda, and deaths of15 people in Burundi, 5688 individuals in Kenya, 846 people in Tanzania, and 3630 individuals in Uganda (WHO, 2023). The four countries responded differently to the pandemic. Walwa and Liaga et al.noted stringent COVID-19 control measures in Kenya and Uganda but lenient measures in Burundi and Tanzania.

COVID-19 emerged in East Africa during the peak of political activities in the region. Burundi, Tanzania, and Uganda were heading to elections in May 2020, October 2020, and January 2021 respectively (Walwa 2023; Patterson 2022; Chamegere 2021; Saleh 2020). In Kenya, there was an active campaign for constitutional changes through a referendum under the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) (Otieno 2021; Ogenga and Baraza 2020). The political situation affected the COVID-19 response in the region in many ways. Some of its specific effects have been assessed in this study. Generally, the political situation compromised COVID-19 responses.

The pandemic affected the political situations in Burundi, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda in many, but majorly five ways. Firstly, COVID-19 stopped the political campaigns for constitutional changes through a referendum under BBI in Kenya (Otieno 2021). Secondly, it worsened the already existing conflicts and violence in East Africa as repressive states exploited it to suppress political opponents and civilians, and extremist groups exploited the fears and discontent created by COVID-19 to infuse violent narratives in the pandemic-affected marginalized population because threats and attacks from extremist groups increased as governments attention were diverted to addressing pandemic-related problems (Walwa 2023). Thirdly, tensions emerged between other EAC member countries and Burundi and Tanzania as other member states accused them of concealing the actual Covid-19 results (Mutalemwa, 2021; Oloruntoba 2021). Walwa also associated tensions between Kenya and Tanzania and at the Kenya-Uganda border with Tanzania’s lenient approach to the pandemic control and the discrimination of Kenyan truck drivers by Ugandan authorities enforcing COVID-19 measures respectively. Fourthly, Mutalemwa argued that the unilateral COVID-19 response by EAC member countries revealed increased old tensions among them, notably: security concerns between Rwanda and Uganda and between Burundi and Rwanda and trade wars between Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. Fifthly, new non-tariff barriers caused by COVID-19 in the East African region prevented trade cooperation and effective negotiations (Olubandwa and Zamani 2022).

Analytical framework

The analytical framework of this study seeks to explain the responses of policy actors to pandemics. The framework has two components, namely: a theoretical and a conceptual framework. Both components of the framework are embedded within the political economy.

Political economy theories of pandemic response

Responses to pandemics can be understood from the perspectives of the classical liberal and public choice theories of political economy. Classical liberals, including Adam Smith, argue that, with a few well-defined exceptions, individuals generally can make decisions that are best for themselves (Smith 1776; Koyama 2021). Public health interventions are only limited to containing the spread of contagious diseases and other pandemics causing sufficiently large and morally serious harm (Mill 1989; Epstein 2003, 2004). The interventions are justified by the economic theory of market failure, notably: externalities pioneered by Alfred Marshall, Pigou (1952), and Ronald Coase (1960), which support widespread government action if the externalities in question are large, non-pecuniary, and difficult to observe and measure. These interventions are motivated by and viewed as corrective to market failures (Leeson and Thompson 2021). In supporting the exceptional government interventions, Adam Smith criticized the libertarians’ exertions of the natural liberty of a few individuals as dangerous to the security of the whole society and demanded its restraint by-laws (ii. ii Smith 1776).

However, some classical liberals criticized Adam Smith’s justification of the use of the military to maintain a martial spirit and prevent leprosy or any other loathsome and offensive disease from spreading in the population as taking for granted the state’s commitment to devote its most serious attention to preventing the pandemic. They warn that the power of the government to regulate the spread of an epidemic can easily be misused (Parmet 2008; Koyama 2021). There are many historical examples of governments using epidemics to justify violating medical ethics and abusing their power. These include medical malpractice by public health authorities in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study in the USA where the study’s participants were examined, had their blood drawn, and their corpses subjected to autopsies, but they were not given proper medical treatment (Alsan and Wanamaker 2018; Koyama 2021), medical interventions undertaken during French colonial rule in West Africa (Lowes and Montero 2021) and the forcible sterilisation of African Americans in the 1950s and 1960s in USA (Price and Darity 2010).

The public choice theory (new political economy) of public health stipulates that policymakers and private citizens respond to incentives, including monetary benefits or stay in power (Koyama 2021). Proponents of this theory view policymakers and private citizens as self-interested individuals (Leeson and Thompson 2021). They assert that society consists of competing groups pursuing self-interested goals with the state being itself an interest group wielding power over the policy process in pursuit of the interests of those running it, notably: elected public officials and civil servants (Buse et al. 2005).In particular, Koyama argues that instead of seeking to maximize social welfare, policymakers implement policies that benefit themselves, and private citizens are motivated to comply or not with official policies by incentives.

In the era of COVID-19, the economy faced a shock. The shock affected its supply and demand side (Abbass et al. 2022). To get out of this trap and ensure the full employment and stability of capitalist market economies, the Keynesian theory advocates for government intervention, notably: public investment programmes to steady the rate of investment and counter-cyclical policy, involving the injection of extra spending into the economy when private spending falls and curtailing it when it rises (Skidelsky 2020). These interventions focus on the economic recovery from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, but not mitigating COVID-19 itself.

Political economy analysis framework for COVID-19 response

The political economy analysis framework is a conceptual framework that draws upon political economy factors to analyse particular issues and problems. This study adopted the framework because it complements technical analysis by providing a better understanding of politics and the context behind it (Faustino and Fabella 2011; Fritz et al. 2014; Andrews et al. 2015; Andrews et al. 2017; Pellini et al. 2019). The analysis also facilitates our understanding of what drives political behaviour, how this shapes particular policies and programs, who are the main winners and losers, and what the implications are for development strategies and programs (DFID 2009).

DFID categorises political analysis into country-level, sector-level, and issue-specific analysis. The country-level analysis explores the general sensitivity to the country context and understanding of the broad political-economy environment. The sector-level analysis concerns specific barriers and opportunities within particular sectors. In the issue-specific analysis, the focus is on a specific policy challenge to facilitate an understanding of the political factors, forces, and incentives that shape that specific challenge (Fritz et al. 2014; Menocal et al. 2018). This study adopted the issue-specific analysis to understand the political factors, forces, and incentives that shape the COVID-19 responses, using a framework presented in Fig. 1.

Political behaviours are shaped by the interests, incentives, power, ideas, and values of stakeholders (individual or organizations actors); institutions, and structural factors. Interests refer to “agendas of societal groups, elected officials, civil servants, researchers, and policy entrepreneurs” (Pomey et al. 2010, p. 709). Actors tend to act in such a way as to further their own economic and/or political interests (DFID 2009). For DFID, incentives are the driving forces of individual and organised group behaviour. The actor’s power influences decision-making and resource allocation. Values and ideas include political ideologies, religion, and cultural beliefs that shape political behaviour and public policy (DFID 2009). Institutions are formal and informal rules that structure human behaviour (North 1990). These rules shape human interaction and political and economic competition, including the incentives facing political actors (DFID 2009). Structures are geographical, demographic, historical, economic, and social characteristics of the country or regional factors that influence the political and institutional/policy environment in which government actors and decision-makers operate (Whaites 2017; Pellini et al. 2021).

Actors and their interests in COVID-19 response

COVID-19 and its control measures affected many actors. The actors include governments, politicians, businesses, civil society organizations, religious denominations, and ordinary citizens. COVID-19 responses of these actors differed depending on their varying interests.

Government and politician interests in COVID-19 response

For most governments, COVID-19 responses meant saving lives, livelihoods, and the economy. The rapid and deadly spread of the virus prompted governments to enact policies and implement measures to reduce the infection rate (De Villiers et al. 2020; Mintrom and O’Connor 2020; Greer et al. 2020). They also addressed the effects of the measures on livelihoods and the economy in many ways. For example, De Villers et al. noted the provision of social support and economic relief fund in South Africa. Mintrom and O’Connor reported the use of income support and broader expenditure measures in many countries. However, other governments and their leaders manipulated the COVID-19 responses for their own political and economic interests.

They suppressed science for political and financial gain (Abbasi, 2020). For example, some governors in the US downplayed the public health recommendations for controlling COVID-19 but instead emphasized people’s livelihoods, the economy, and the protection of people’s civil liberties and constitutional and individual rights over their lives (Mintrom and O’Connor 2020). Abbas also implicated the UK’s pandemic response for suppressing science in four instances.

Similarly, they exploited the COVID-19 measures to suppress opposition politicians or their strongholds. For example, Adeniran (2021) noted the use of excessive force, unwarranted fines, disproportionate restrictions, and the criminalisation of non-compliance with COVID-19 rules to suppress opposition and dissent in Myanmar and the Philippines. Barceló et al. (2022) also observed the use of COVID-19 policies as a tool for political repression in Brazil, China, Canada, France, India, Italy, Japan, Nigeria, Russia, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States. In Brazil, the political interests of the federal government disrupted the flow of financial transfers and slowed the deliveries of essential supplies to certain regions (Ferigato et al. 2020).

Government responses also served as patronage. In Bangladesh, for instance, Ali et al. (2021) observed the governance of relief distribution by the non-transparent and patron-clientelistic system which snatched the supervisory functions of relief delivery from bureaucratic to political actors. Matamanda et al. (2022) also reported relief distribution along a partisan line in Lesotho.

Law enforcement officers also selectively implemented COVID-19 mitigation measures in favour of others. For example, Baker (2020) observed that political leaders strongly encouraged the wearing of masks, but they selectively enforced it. Mathew et al. (2022) and Kuiper et al. (2020) also observed selective enforcement of COVID-19 regulations in Zimbabwe and the Netherlands respectively. Thusi (2020) observed the application of COVID-19 rules based on race and the police flouting of mask-wearing mandates in the US. While Baker, Kuiper, et al., Mathew et al, and Thusi report selective enforcement of COVID-19 control measures as a negative practice, Ali et al. (2021) and Watts et al. (2021) noted its positive side. Ali et al. found selective enforcement of COVID-19 directives for favouring the poor and the hungry in Bangladesh. Watts et al. also noted the use of selective enforcement of COVID-19 measures for combating preexisting racial and health disparities in the United States.

Both the ruling and opposition politicians exploited the COVID-19 responses for political campaigns. In Ghana, for example, Nyarko et al. (2021) found that ruling and opposition politicians donated billboards, signposts, and hand-washing equipment with inscriptions and stickers purporting to educate communities on COVID-19 protocols, but more of their design spaces were allotted to party identities of politicians. Government leaders also exploited the pandemic as an opportunity to play the role of the heroic saviour and the exclusive problem solver; grabbing for themselves the symbolic gains, increasing the concentration of power, and expecting citizens to trust nobody except the charismatic leader or party (Kövér 2021). They grabbed the crisis not only to divert the focus from their shortcomings, but also to govern by decree and to increase options for monitoring their citizens, the opposition, and civil society organisations and for obstructing their radius of action (Magyar 2020; Yendell et al. 2021).

Armed forces also had political interests in the COVID-19 response. For instance, when cutbacks in Dutch public spending loomed, the COVID-19 crisis presented an opportunity for the Dutch armed force to demonstrate to taxpayers and their potential recruits how important the force is to society (Lazaro 2020; Kalkman, 2021). The UK Army also exploited its contributions during the COVID-19 crisis to redeem its reputation that was tarnished after the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and to resolve its recruitment and retention problems (Kennard and Glenton 2020).

Governments also exploited COVID-19 for additional funding. For example, Lenhardt (2021) noted a new commitment of funding from donors for the Covid-19 responses. Angaw (2021) reported the acquisition of various bilateral and/or multilateral financial assistance by the Ethiopian Government for enhancing the national public health response. Kim (2020) reported increased implementation of supplementary budgets during the COVID-19 crisis in South Korea. Rahim et al. (2020) found reprogramming of existing budgets, activation of contingency reserves, and adoption of supplementary budgets in many countries as responses to the COVID-19 crisis.

Government responses to COVID-19 were also ridden with corruption. For example, the UK’s pandemic response involved state corruption on a grand scale (Abbasi, 2020). Reuters (2020) also reported poor utilisation of COVID-19 funds across Africa where COVID-19 responses were ridden by gross irregularities, poor planning, dubious contracts, and corruption scandals. Sanny (2022) and also observed unfair distribution of COVID-19 relief items and loss of resources to corruption. Particularly, UNDP and Southern Voice (2022) noted irregularities in identifying beneficiaries for relief items such as food and masks.

Business interest in COVID-19 response

Some business entities responded to the pandemic with the motive of promoting public goods. As part of their social corporate responsibility, small businesses and big corporations in developed and developing countries donated money, materials, and equipment towards the COVID-19 response (Navickas et al. 2021; Manuel and Herron 2020; García-Sánchez and García-Sánchez 2020). However, other businesses inhabited profit motives in their response. In Bangladesh, for example, court fines were given to 64 businesses, including 8 pharmacies, for raising prices of basic commodities, masks, and hand sanitizers; and 56 traders for dealing in adulterated food products (Khan 2020). Binagwaho et al. (2021) also reported higher pricing of COVID-19 vaccines and medical equipment and vaccine nationalism where hoarding vaccines by countries to inoculate groups that are not at high risk resulted in a substantial reduction in the supply of available vaccines. Thiagarajan (2020) reported higher pricing of COVID-19 treatment with a lot of hidden costs in India. These observations indicate that many businesses had profit motives. While many businesses took altruistic actions towards COVID-19, García-Sánchez, and García-Sánchez observed that these seemingly benign behaviours may have hidden economic interests of generating benefits for the business through their impact on image and reputation.

Interests of civil society organisations (CSOs)

CSOs had diverse public interests in the COVID-19 response. Some sought to save lives and support livelihoods. They provided medical equipment, relief items, and other support (Leap et al. 2022; Kövér 2021). Another group, including CSOs in Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa fought and protested corruption and human rights violation and demanded transparency and accountability in managing COVID-19 response funds and materials (Kövér 2021; Eribo 2021; Uroko and Nwaoga 2021). ForKövér, these CSOs were perceived by many governments as adversaries and threats; consequently, their operations were restricted and obstructed by governments, including Hungary and China. However, others protested and criticized the poor government responses to the pandemic. For example, a network of volunteers in the US fought what they called neglect by their government and president (Leap et al. 2022). Leap et al. noted their resistance to the neoliberal doctrines that profits must be prioritised over people and that the market not state institutions should play a leading role during a national emergency.

Interests of religious groups

Religious groups had two main interests. Some groups got stuck to religious traditions of praying in big gatherings and encouraging prayers as a solution to all problems. Because COVID-19 measures threatened their interests, they defied these measures and generated many conspiracy theories, including the virus being satanic and politically motivated (Wildman et al. 2020; Marshall 2020; Yendell et al. 2021). However, Wildman et al., Marshall, and Yendell et al. also observed that other religious groups embraced the public interest by donating to COVID-19 response and encouraging their believers to follow COVID-19 control guidelines.

Interests of ordinary citizens

For ordinary citizens, the COVID-19 response was about health and economic risk. However, perceived economic risk tends to consistently predict mitigation behaviour (Nisa et al. 2021). For example, Bodas and Peleg (2020) found that concern about the loss of income is a major obstacle to compliance with household quarantine. Maloney and Taskin (2020) also noted resistance to abandoning sources of livelihood in the poorest countries. The difficulty of ensuring compliance with COVID-19 mitigation measures in the absence of a comprehensive social protection system or livelihood protection was also reported in Malawi (Nkhata and Mwenifumbo 2020). Ordinary citizens also protested human rights violations and corruption by government employees. For example, Herbert and Marquette (2021) associated protests in every world region and every regime type with many factors, including the use of force in COVID-19 responses. Orjinmo (2020) also noted youth-led protests in Nigeria, which were triggered by anger over police brutality and the unequal distribution of palliatives and relief packages related to COVID-19.

Methods and data

This paper used a literature review method. The method was adopted because it can integrate many study findings. In particular, a systematic review method was used because it is a rigorous and evidenced-based method that promotes transparency and reduces bias (Canwat, 2023). It constitutes a high-quality source of cumulative evidence (Maclure et al. 2016). The review minimises bias by using explicit, systematic methods and it gets rid of “rubbish” and summarises the best of what remains (Akers et al. 2009). This, therefore, ensures the quality of evidence.

Search strategy and selection criteria

The review followed the guideline of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). Studies published from January 2020 to September 2022 were selected by searching Google Scholar. This period covers literature on COVID-19, right from the time publications on the pandemic began to emerge up to the time the review study was conducted. The search terms used were: allintitle: Politics COVID-19 Burundi OR Kenya OR Tanzania OR Uganda; Politics COVID-19 Burundi OR Kenya OR Tanzania OR Uganda,allintitle: PoliticalCOVID-19Burundi OR Kenya OR Tanzania OR Uganda and Political COVID-19 Burundi OR Kenya OR Tanzania OR Uganda. Two major criteria were used for including articles in the review: the study must concern the politics or political economy of COVID-19 and it must be conducted on and/or in Burundi, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. Articles selected for the review covered debates, contestations, conflicts of interest, and values or beliefs over the allocation and use of economic and political resources during COVID-19 and its responses. For example, Kilonzo and Omwalo (2021) illustrated the conflict of beliefs during the COVID-19 response by analyzing how the use of technologies in praise and worship contradicted the myths and misconceptions about pulpit religiosity in Kenya (Kilonzo and Omwalo 2021), Tanzania’s refusal of COVID-19 vaccines (Makoni 2021) constituted contestations of science and partisan civilian targeting by the state during the COVID-19 response in Uganda (Grasse et al. 2021) was a conflict of interest as the state exploited the response to achieve its political goal. However, articles such as contraception access during the COVID-19 pandemic (Aly et al. 2020), the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal health (Kotlar et al., 2021), and Tanzania’s wildlife sector (Jafari et al., 2021) were excluded because they lack all the above-mentioned political dimensions.

Selection and quality assessment of papers

Figure 2 shows the processes of literature search and assessment. The search generated 1606 papers from Google Scholar. Upon deleting duplicates, 1529 records were retained, 1428 articles were excluded and 101 full-text articles that remained were further assessed, leaving 66 papers included in the analysis. These articles were excluded because they lacked political economy analysis and focus on Burundi, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda and some of them were not in English.

Assessment of papers included in the review

For each study included in the review, the date and country of the study were recorded and the response variables were also assessed. Response variables fall into three categories. Firstly, the COVID-19 response is a political opportunity, which includes response as an opposition control strategy, campaign strategy, patronage, and selective enforcement. Secondly, the COVID-19 response is an economic opportunity, which comprises response as a government income source, benefits for government staff, income for security forces, and income for common citizens. Lastly, COVID-19 response as contestations, which entail contestations of science, vaccines, role allocation during COVID-19 response, selective enforcement of COVID-19 directives, corruption in relief provision, and brutality of security forces. The number of times response variables were observed in the reviewed literature denotes their frequencies, which are presented in tables. Percentages were also generated to show the relative frequencies of response variables.

Description of the reviewed literature

Out of the 66 papers included in the review, 13 focused on Burundi, 16 on Kenya, 14 on Tanzania, 17 on Uganda, 1 on Uganda and Tanzania, 4 on Burundi and Tanzania, and 1 focused on Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania. The literature reviewed consisted of 46 journal papers, 1 book chapter, 6 research reports, 4 London School of Economics Blogs, 3 civil society reports, 4 media reports, and 2 policy briefs. The literature is of higher quality as the majority is published in rigorous peer-reviewed scholarly sources.

Results

COVID-19 and its control measures: effects and responses

COVID-19 had two major effects on actors, namely: primary and secondary effects. The primary effects entail the direct effects of COVID-19 on actors. In the secondary effects, actors are affected by COVID-19 control measures. Here, the effects of COVID-19 on actors are indirect. However, responses to COVID-19 fall into four major categories: primary, secondary, hard, and soft responses. While primary responses targeted the COVID-19 pandemic, secondary responses sought to address the effects of the primary responses, especially the economic and social lockdowns. Hard responses are obligatory, but soft responses are voluntary.

Primary effects of and responses to COVID-19

COVID-19 had significant health, economic and political effects. Not only did it kill and infect many people, but the pandemic also created fear and uncertainty (Wild-Wood et al. 2021; Leach et al. 2022). It also increased the demand for intensive medical care (Bukenya et al. 2022; Leach et al. 2022) and permitted the state to use its emergency public order mandate to secure the public good that is a virus-free community (Isiko 2022; Turley 2020). Leach et al. observed an increase in demand for COVID-19 vaccines as the fear of COVID-19 increased with the rising number of people getting infected and dying. The pandemic, therefore, created economic opportunities for private health companies. It also increased and legitimised the government’s power to control and regulate political, economic, social, religious, and other activities.

In response to the pandemic, governments adopted both soft and hard approaches. While soft approaches are voluntary, hard measures are obligatory. Soft responses included public health campaigns, engagement of religious groups, the establishment of a COVID-19 task force and other related structures, and the provision of COVID-19 vaccines. Governments rolled out intensive and extensive public health campaigns using radio, TV, SMS, print media, and online communication (Anguyo 2020a; Wild-Wood et al. 2021). The campaigns were meant to create awareness about coronavirus, including its danger and control measures. In Uganda, for example, the government engaged religious groups to seek their cooperation in controlling COVID-19 (Isiko 2022). For Isiko, the government persuaded religious leaders to close all their places of worship because these places are more vulnerable to the virus. East African Governments also established committees or task forces to spearhead the response to COVID-19. For example, the National Emergency Response Committee was established in Kenya through executive order No. 2 of 2020 (Aluga 2020), and the COVID-19 National Response Taskforce in Uganda (Bukenya et al. 2022). In Tanzania, the Government also established a Covid-19 taskforce and associated sub-committees (Saleh 2020). East African Governments used a variety of vaccines. For example, Tanzania administered Johnson and Johnson vaccine in its first vaccination batch (Richardson, 2022) and the Government of Uganda used the Astra Zenecavaccine for protecting the high-risk section of its population (Leach et al. 2022). The use of different vaccines by these countries depended on the type of vaccines donated. While the United States donated Johnson and Johnson vaccine to Tanzania(Hyera, 2021), the COVAX facility donated the AstraZeneca vaccine to Uganda (Napakol and Kazibwe, 2022; Storer and Jimmy, 2021).

In a hard way, governments used their emergency mandate to order the closure of congested places such as bars, learning institutions, markets, non-essential businesses, public transport, and other gatherings of social, cultural, political, recreational, and religious nature (Isiko 2022; Aluga 2020; Barugahare et al. 2020; Richardson 2022). While the Government of Tanzania established lockdown when it confirmed the first COVID-19 cases, Richardson noted contradictory responses following the announcement of the election date (Buguzi 2021).

Secondary effects and responses to COVID-19

COVID-19 control measures significantly affected the economy in several areas, including revenue, trade, and tourism. Government revenue collection was reduced and tourism earnings dropped (Saleh 2020; Richardson, 2022; UNECA, 2020; Makumi et al., 2020). Foreign direct investments, imports, and exports declined, but borrowing costs and debt vulnerabilities (debt-to-GDP ratio) increased (UNECA, 2020; Makumi et al., 2020). Tourism dropped because of the reduced influx of tourists. In Tanzania, for example, ‘the US Embassy publicly warned that cases were escalating in hospitals and that tourists should not visit the country’ (Patterson 2022). The drop in tourism significantly affected related service sectors, including employment.

The economy was not the only victim of COVID-19 control measures. Political, economic, and other actors, including ordinary people, were also affected. While the control measures restricted political activities and spaces, they increased the power of ruling parties to suppress opposition and ordinary citizens (Patterson, 2022; Bukenya et al. 2022; Kabira and Kibugi 2020). The measures also led to the closure of many businesses (Bukenya et al. 2022), some of them became unsustainable (Richardson, 2022) and others incurred losses (Kiaka et al. 2021). However, businesses dealing in essential commodities flourished. Religious groups were also affected by the COVID-19 control measures. The measures physically disconnected religious institutions from their flock and reduced their financial collections, leading to the inability of some religious institutions to meet their bills (Isiko, 2022; Kilonzo and Omwalo, 2021; Wild-Wood et al. 2021). Traditions and customs regarding death and burial were disrupted (Ogenga and Baraza, 2020). The livelihoods of millions of people in the informal sector were also shattered by public health measures (Macdonald and Owor, 2020; Kiaka et al. 2021). In particular, the pandemic and its policy response caused great economic hardships for persons outside the realm of the government civil service and low-income communities (Bukenya et al. 2022; Ogenga and Baraza 2020). Bukenya et al. also noted an increase in gender-based violence, discrimination, spatial injustices and inequalities, and sexual exploitation against certain categories of people.

The enforcement of COVID-19 control measures was also problematic. In Kenya, for example, circumstances of the pandemic increased opportunities for more indiscriminate violence, harassment, and systemic corruption among police services (Chau 2021; Kiaka et al. 2021). Similar problems were also noted in Uganda. The security forces brutalised people through the excessive use of force and abuse of their power (Kabira and Kibugi 2020; Nkuubi 2020). This led to widespread bribery, extortion, and violation of human rights, including killings and excessive beatings. These corruption practices and human rights violations were reported in many parts of Kenya and Uganda (Nkuubi 2020; Kemboi 2020; Kabira and Kibugi 2020; Bukenya et al. 2022). Consequently, people wondered whether they would be killed by the coronavirus or the police.

Actors responded to the effects of COVID-19 control measures in many ways. East African Governments responded to the effects of COVID-19 control measures on the economy and livelihoods by heavy borrowing as well as provision of a stimulus package and relief support. In 2020, the IMF authorised a loan of 491.5 million US dollars for Uganda from its Rapid Credit Facility to finance health, social security, and macroeconomic stability initiatives, resolve the immediate balance of payments and fiscal needs emerging from the COVID-19 epidemic, and catalyse additional assistance from the international community (Kasirye 2020). The Government of Kenya provided a stimulus package covering a 100 percent tax relief for individuals with a gross income of up to 24,000 Kenyan Shillings, the income tax reduction from 30 percent to 25 percent, the Value Added Tax reduction from 16 percent to 14 percent, and cash transfers to orphans, the elderly and other vulnerable members of the society (Aluga 2020). Relief items included cash, masks, and food items (Macdonald et al. 2020a, 2020b; Anguyo 2020a; Mulinda 2021). The government also called for support from businesses and other entities.

Most actors, including politicians, businesses, and religious groups responded to COVID-19 control measures positively by complying with government directives applicable to them and supporting COVID-19 responses. Politicians distributed masks, sanitisers, hand-washing equipment, and food items (Anguyo 2020a; Mulinda 2021). Businesses also donated to the COVID-19 response (Isiko 2022; Saleh 2020; Mulinda 2021; Bukenya et al. 2022). Religious groups closed their worshipping places and encouraged their congregants to follow COVID-19 public health guidelines (Wild-Wood et al. 2021). They also provided spiritual and psychosocial support and donated relief items to vulnerable people (Wild-Wood et al. 2021, Isiko 2022). Places of worship gave hope and prayed for God’s help (Wild-Wood et al. 2021). Others asked their worshippers to support vulnerable individuals (Saidi-Mpota 2020). However, some church leaders defied the COVID-19 directive on closing places of worship. For example, Pastors of the Pentecostal Church in Mombasa and Kitale, Kenya were arrested for defying the directive by holding their normal church services (Kilonzo and Omwalo 2021). Cultural institutions also supported the COVID-19 response. For example, Buganda, Busoga, and Bunyoro kingdoms donated food and money to the COVID-19 national task force (Isiko 2022). Traditional leaders and elders from Kipsigis, Kikuyu, and Kuria communities held ritual ceremonies to curse and exorcise the virus from Kenya but claimed no healing miracles (Kilonzo and Omwalo 2021).

Responses of actors to COVID-19 were driven by many factors. For governments, responses were mainly driven by their constitutional mandate to provide public goods. They used their emergency mandate to secure the public good which is a virus-free community (Isiko 2022; Turley 2020). The differential state responses were driven by the differential effects of COVID-19 and its control measures. In Kenya, for example, the worst affected counties received more stringent control measures than other areas (Wild-Wood et al. 2021). Relief support was provided to the most affected and vulnerable places and people than others. In Uganda, relief support was channelled to the most vulnerable people (Kasirye 2020; Wild-Wood et al. 2021). However, the majority of vulnerable households in the country have been excluded or not benefited from the relief support (Bukenya et al. 2022; Nathan and Benon 2020). In other cases, they have even become more susceptible to COVID-19 infection and response. For example, the eviction of 15,000 slum dwellers in Nairobi exposed them to the risk of COVID-19 infection, and the vulnerable people were more affected the police brutality (Solymári et al. 2022).

Ruling and opposition politicians provided relief support for political motives. However, religious groups provided relief support out of benevolence. While the provision of relief by businesses appeared to have a motive of providing public goods, they might have inhabited economic interest of improving their reputation, consequently, future sales of their products.

Responses of actors to COVID-19 control measures were driven by fear, benevolence, sanctions, and trust in the government. Kilonzo and Omwalo (2021) argued that the seriousness of following the government’s directives shows that COVID-19 has caused fear and panic among the people. Religious elites rationalised compliance with COVID-19 control measures as actions for the common good and well-being of everybody (Isiko 2022; Wild-Wood et al. 2021). Adherence to the measures also depended on the economic situation. As Wild-Wood et al. (2021: 73) noted, “the poor or precariously financed could choose to stay home and starve, or venture out and contract corona”. Some actors complied with the measures because they feared being punished by the enforcement officers (Kemboi 2020). However, Kemboargued that the stringent and brutal approach to the COVID-19 response failed to bring large-scale behaviour changes because it eroded trust in the government and created perceptions that COVID-19 was a façade and a means for the government to obtain additional loans (Kemboi 2020).

Windows of opportunities and contestations associated with COVID-19 responses

COVID-19 as political opportunities

While some political actors suffered, others benefited from the epidemic. The epidemic presented them with four main opportunities. Firstly, the COVID-19 response provided an opportunity to control opposition. Table 1 shows that 13 percent of the studies considered the COVID-19 response as an opposition control strategy. This challenge was prevalent in Uganda and Burundi. Uganda exploited the epidemic to stifle the opposition politicians by preventing them to hold rallies and campaigns beyond 7:00 P.M. (Lukanda and Walulya 2021). The ruling party excluded them from food relief distribution and sidelined them in the Covid-19 Taskforce (Macdonald and Owor 2020; Bukenya et al. 2022). Bukenya et al. also argued that the epidemic was an opportunity for the President of Uganda to consolidate his power by enhancing his performance, and legitimacy and providing patronage to those in need while suppressing the opposition. In Burundi, the government established a 2-week mandatory quarantine for election observers to keep them off and avoid their scrutiny of the presidential elections (Africa CGTN 2020; Birch et al. 2020; Repucci and Slipowitz 2020). Under the pretext of the COVID-19 response, the ruling parties controlled and suppressed opposition parties.

Secondly, the COVID-19 response provided an opportunity to conduct a political campaign. Table 1 shows that 6 percent of the studies reported the COVID-19 response as a political campaign strategy. Politicians donated face masks, sanitisers, and water tanks branded with Party leaders’ names, logos, and slogans (Mulinda 2021; Anguyo 2020b). In Uganda, the government concentrated relief food distribution in opposition strongholds, especially to the organised groups with the power to organise votes for the ruling party (Macdonald and Owor 2020). Macdonald and Owor observed more relief provisions in areas where senior members of the district task force had political ambitions. They also noted high attendance of task force meetings by local politicians seeking elected positions in the next election. In Tanzania, the late President Magufuli opened the economy to gain political support believing that it would promote the economic growth of his country (Lukanda and Walulya 2021). Lukanda and Walulyaalso associated the Uganda Government’s response to the acquisition of political leverage. Generally, politicians exploited COVID-19 responses as platforms and means for political campaigns.

Thirdly, the COVID-19 response was patronage. Table 1 shows that 6 percent of the studies considered the COVID-19 response patronage. Managing COVID-19 funds, relief distribution, and tenders for relief items and other services were allocated to regime loyalists (Bukenya et al. 2022; Izama 2021; Macdonald and Owor 2020). Macdonald and Owor noted that while other members of parliament (MP)were required to return the 20 million UGX allocated for COVID-19 response in their constituencies, loyal ruling party MPs received 40 million for the same response. So, the COVID-19 response presented the opportunity to reward regime loyalists.

Fourthly, the COVID-19 response favoured some classes of people. Table 1 shows that 8 percent of the studies reported selective implementation and enforcement of COVID-19 control measures. Governments enforced rules that least affect their political objectives (Nyadera et al. 2021). Technocrats favoured themselves, relatives, and friends for cash relief grants(Bukenya et al. 2022). The wealthy and well-connected used their social and political connections to move freely (Macdonald and Owor, 2020; Nyadera et al. 2021). In Uganda, the army and the police dispersed only meetings and activities of opposition politicians (Lukanda and Walulya, 2021). This has also been the case in Burundi where the government allowed political gatherings for the ruling party, but members of the opposition faced heavy-handed clampdowns that stifled their political activities (Vandeginste, 2020). While Burundians faced new COVID-19 restrictions during the election, foreign observers were required to quarantine; leading to their exclusion from the election observation (Repucci and Slipowitz 2020). Opposition strongholds often experienced a disproportionate increase in repression (Grasse et al. 2021). In Kenya, the enforcement of COVID-19 control measures was more stringent in heavily Muslim neighbourhoods that were suspected of harbouring radicalised networks (Médard 2022).

COVID-19 as economic opportunities

COVID-19 provided not only political benefits but also economic opportunities. Firstly, it increased government revenues. Table 1 shows that 5 percent of the studies reported the COVID-19 response as a government revenue source. The pandemic attracted bilateral and multilateral funding (loans and donations) from international agencies (Bukenya et al. 2022; Kasirye 2020). Governments got supplementary budgets for the COVID-19 response (Lukanda and Walulya 2021). Lukanda and Walulya noted the receipt of $300 million by Uganda from the World Bank to support economic recovery from the pandemic. Kasirye also reported the IMF loan authorisation worth $491.5 million for Uganda. Kenya’s Government also received $50 million from the World Bank to support the COVID-19 response (Mohammed et al. 2020).IMF granted a debt relief worth $25.7 million to free up money for public sector health needs (Richardson, 2022). Individuals and organisations also donated cash, equipment, and materials to governments (Lukanda and Walulya, 2021; Bukenya et al. 2022; Saleh, 2020). While the funds were meant for the response and economic recovery from the pandemic, they were mismanaged. The borrowing exhausted the funding quotas, raised the debt-to-GDP ratios, and sparked concerns about the effectiveness of the loan (Bukenya et al. 2022; Kasirye 2020). The supplementary budgets were misallocated. In Uganda, Lukanda and Walulya found the use of a supplementary budget as an excuse to allocate huge sums of money to non-health-related matters (Lukanda and Walulya 2021). The state house classified budgets also increased (Kasirye 2020).

Secondly, the COVID-19 response generated economic benefits for technical staff. Table 1 shows that 5 percent of the studies reported the COVID-19 response as a source of economic benefits for government staff. Government technocrats enlisted themselves, relatives, and friends for cash relief grants, even when they are not eligible (Bukenya et al. 2022). Corruption increased during the procurement of COVID-19 materials (Médard 2022). In Kenya, for example, COVID-19 aggravated corruption in the counties where huge financial resources were sent (Ochieng-Springer, 2022). Funds were also embezzled through collusion between the Ministry of Health and the Kenya Medical Supplies Authority (Kilonzo and Omwalo 2021). Some government staff also diverted the COVID-19 funds (Mohammed et al. 2020).

Thirdly, the COVID-19 response provided earning opportunities to law enforcement officers. Table 1 shows that 5 percent of the studies indicated the extortion of money from people by the security officers enforcing COVID-19 control measures. They sought and accepted bribes from those who violated COVID-19 rules (Bukenya et al. 2022; Médard 2022; Barugahare et al. 2020; Nkuubi 2020; Nathan and Benon 2020; Kemboi 2020; Kiaka et al. 2021). Sometimes, money is even extorted from people who are not violating COVID-19 rules (Parker et al. 2020). Kemboialso was observed breaking into homes and shops and looting food by security personnel.

Fourthly, ordinary citizens also benefited economically from the epidemic. Table 1 shows that 2 percent of the studies acknowledged economic benefits received by ordinary citizens during COVID-19. Unethical business practices such as hoarding and manipulation of prices of essential commodities like food and safety products like sanitisers and masks became common. In Uganda, a group of individuals gained by mounting a fake COVID-19 vaccination exercise, in which at least 800 vaccine-hungry people were persuaded into paying for ‘vaccines’ which were largely water (Leach et al. 2022). Private hospitals also exploited people (Eryenyu 2022). Eryenyuimplicatedprivate health facilities in poor countries in responding to increased demand for COVID care by arbitrarily setting the prices of treatments so high that people had to sell their land or other valuable assets to afford them. When public transport was prohibited, some owners of private vehicles used their vehicles to transport passengers at exorbitant fares (Barugahare et al. 2020). In Kenya, privately-owned taxis hiked transport fares (Kabira and Kibugi 2020).

COVID-19 as contestations

COVID-19 response generated not only political and economic opportunities but contestations by actors. Firstly, there were contestations of science and vaccine. Table 1 shows that 35 percent of the responses are contestations of science (21 percent) and vaccines (14 percent).COVID-19faced denial and misinformation. It was considered a non- or less severe disease. While some people view COVID-19 as a hoax and a tool used by the government to generate money from donors and to control political opponents, others consider it real, but less severe than the normal flu and the disease of the rich, the white, Asians, and the Chinese (Chamegere 2021; URN, 2020; Isiko, 2022). People wearing masks were denounced as pro-government (Médard 2022).

Burundi downplayed and refused to recognize the Covid-19 threat, ridiculed international health advice, and expelled four WHO experts, including the country representative (Fraiture 2022; Mohee 2021). Tanzania contested scientific equipment and expert by critiquing the Covid-19 testing machines, sacking the Deputy Minister for Health, and stopping the provision of statistics of and denying COVID-related cases and deaths (Mutalemwa, 2021; Mohee 2021). Instead, Burundi and Tanzania trusted the divine power. Officials in the Burundian and Tanzanian governments claimed that religious devotion and faith gave them divine protection as their countries and people were spared and saved from COVID-19 infection and death (Lührmann et al. 2020; Guardian, 2020; Mutalemwa, 2021). The Tanzanian President Magufuli also declared Covid-19 was a devil unable to live in the body of Christ because it burns instantly upon entry; so, Tanzanians should defeat the devil through their daily prayer (Saleh 2020). In Kenya, a pastor for the Pentecostal Church in Mombasa, defied closing their churches, arguing that God is greater than Covid-19 and science, thus, it is in the Church that the solution to the pandemic could be found (Kilonzo and Omwalo 2021).

COVID-19 vaccines also faced hesitation. The Tanzanian Government doubted and refused the vaccines. While Burundi’s government officials claimed the country needed no COVID-19- vaccines because of divine protection, otherBurundians argued that the vaccine is for the white people but not them because the pandemic was not serious as they only suffer from the flu (Kaneza 2021; Pelizzo and Kinyondo 2022). The Tanzanian President warned against using vaccines, arguing that Tanzanians would be used as “guinea pigs”(Chakamba 2021). Some people hesitated using vaccines because of concerns about their side effects, safety, effectiveness, and the shorter duration of their creation (Mwai, 2021; Nyalile and Loo, 2021; Masele and Daud, 2022). Instead, the government encouraged prayers and the use of traditional medicines (Saidi-Mpota 2020). Saidi-Mpotaobserves that the Tanzanian Government attributes its self-ascribed success against COVID-19 to the use of traditional medicines and religious prayers. Other people also give credit to the Tanzanian Government for successfully reducing COVID-19 severity through spiritual healing and medicinal herbs (Kamazima et al. 2020). Publicly, Gwajima, the Tanzania Minister of Health, and health officials drank a herbal concoction including ginger, garlic, and lemons, and inhaled steam from herbs, promoting them as natural means of killing the virus (Makoni 2021). In Burundi, people with COVID-19 symptoms chose traditional “food medicines,” including ginger, lemon, and eucalyptus leaves (Kwizera 2021). However, the Catholic Bishops of Burundi have spoken consistently against the reckless handling of the pandemic, urging strong measures to prevent the spread of the disease (Montevecchio, 2021).

Secondly, there were also contestations of roles within the government. Table 1 shows that 7 percent of the responses were contestations of roles within the government. In Uganda, technocrats contested being sidelined by the security forces and political acquaintants (Mbonye 2020). Uganda National Planning Authority (UNPA) also contested the oversized role of the Scientific Advisory Committee (SAC). UNPA claimed that SAC took over its planning role (Bukenya et al. 2022). Bukenya et al. also noted power rivalries and contestations within the structures established by the regime to respond to COVID-19. A battle also erupted between the parliament and the executive branch over the use of budgetary resources for fighting COVID-19 (Macdonald and Owor 2020). Politicians fought over the management of the COVID-19 response (Mohammed et al. 2020). In Uganda, for example, Macdonald and Owor noted the slapping of the Resident District Commissioner (presidential appointee) by the Local Council 5 Chairperson (Opposition politician)over the vehicle allocation for the Covid-19 response. The Government of Uganda also contested the direct distribution of relief items to vulnerable people by non-governmental organisations (Bukenya et al. 2022; Macdonald and Owor 2020).

Thirdly, corruption in relief provision was also contested. Table 1 shows that 3 percent of the responses were contestations of corruption related to relief provision. In Kenya, Chau (2021) reported protests against corruption in the procurement of medical supplies. In Uganda, there was a protest against the poor quality of relief items, political profiling of relief beneficiaries, sluggish relief distribution to the most vulnerable people, and using procurement to benefit those with political connections to the state (Kasirye 2020). Macdonald and Owor (2020) also noted protests against relief provisions to only relatives and friends of COVID-19 task force members. Extorting the public by the military was also contested (Nkuubi 2020).

Fourthly, there was contestation about the selective enforcement of COVID-19 directives. Table 1 shows that 3 percent of the responses were contestations of selective enforcement of COVID-19 directives. Opposition supporters took part in mass protests against selective enforcement of COVID-19 (Cheeseman, 2021) and political profiling (Kasirye 2020). Cheeseman implicated the electoral commission and security forces in responding and enforcing COVID-19 protocols selectively, shutting down opposition events, and detaining and harassing opposition politicians while allowing ruling party meetings to continue unhindered. While the President of Uganda blocked opposition politicians from distributing relief items purportedly for violating social distancing rules, ruling party politicians and government agencies were allowed to distribute food at times without any social distancing, as people crowded in the scramble for relief items (Lukanda and Walulya 2021). There was also protest against the disproportionate relief provision to areas where senior members of the District COVID-19 Taskforce have political ambitions (Macdonald and Owor 2020). Macdonald and Owor also found bitter complaints by ordinary people about the double standard used in enforcing COVID-19 lockdown rules. They observed the relatively wealthy and well-connected using their social and political connections to move freely around town, yet they are among the essential workers.

Fifthly, there were also contestations against the brutality of security forces. Table 1 shows that 2 percent of the responses are contestations against the brutality of security forces. Security forces beat and killed people, purportedly for violating COVID-19 directives (Lukanda and Walulya 2021). Security forces unleashed more brutality on opposition leaders and supporters as well as journalists (Leach et al. 2022; Lukanda and Walulya 2021; Macdonald and Owor 2020; Nkuubi 2020). Leach et al. noted arbitrary arrests, forceful hospitalisation, and concerns of many opposition supporters that they were being targeted for sinister reasons. Nkuubi also noted the targeting of journalists for covering stories depicting overt brutality, bribery, and extortion, among other violations, and abuses of power by the security forces under the pretext of enforcing lockdown measures. Lukanda and Walulya as well as Macdonald and Owor reported the arrest and beating of opposition politicians who were distributing food in their constituencies.

Contestations occurred not only at the national level but also at the East African Community (EAC) level. The EAC Secretariat prepared a COVID-19 response plan and guidelines for a quick flow of information, public awareness, and prevention of pandemics by the member states (EAC Secretariat, 2020). However, East African Community member countries contested the plan and guidelines as they responded to the pandemic differently.

Tanzania and Burundi concealed the actual COVID-19 cases (Nasubo et al. 2022; Basedau and Deitch 2021; Owiny et al., 2020). Tanzania and Burundi also relaxed their social distancing measures, but their East African counterparts, including Kenya and Uganda, imposed curfews and lockdowns (Mutalemwa, 2021; Basedau and Deitch 2021; Liaga et al. 2020). While Kenya, Uganda, and other East African Community member countries viewed church gatherings for prayers as conduits for spreading the virus, Tanzania and Burundi consider them sources of healing and protection from COVID-19 (Mutalemwa, 2021; Nasubo et al. 2022). Medinilla et al. (2020) and Nasubo et al. also reported the absence of late Tanzania’s President, John Pombe Magufuli, and late Burundi’s President, Pierre Nkurunziza at the East African Community Covid-19 consultative video conference However, these contestations largely ended following the death of John Pombe Magufuli and Pierre Nkurunziza and the enthronement new presidents of Tanzania and Burundi respectively (Pelizzo and Kinyondo 2022).

Nasubo et al. also noted the contestation of the administrative guidelines of the EAC secretariat on the movement of people and cargo across borders as member states implemented different measures. This strained relations and hampered trade between EAC member states. For example, Mutalemwa and Nasubo et al. reported tensions between Rwanda and Tanzania, Kenya and Tanzania, Uganda, and Rwanda, and between Kenya and Uganda. Nasubo et al. attribute the uncoordinated pandemic responses by EAC member state to ideological differences, trade wars, suspicion, and mistrust. They observe that member countries responded unilaterally by imposing border restrictions and checks to safeguard national interests.

Contestations of COVID-19 responses also occurred within religious groups. For example, the Tanzania Episcopal Conference (TEC) defied the positions of the Pope and the Archbishop of Canterbury on COVID-19 (Mutalemwa, 2021). Similarly, a Catholic Bishop suspended public gatherings in the Rulenge-Ngara Diocese contrary to the TEC’s position on executing church services (Nakkazi 2020).

Discussion

In summary, COVID-19 and its responses presented political opportunities to suppress opposition, conduct political campaigns, provide patronage, and favour particular classes of people. Economically, the pandemic and its responses became sources of income and benefits for governments and their technical staff, law enforcement officers, businesses, and ordinary citizens. However, COVID-19 and its responses also generated contestation from many actors. Actors contested COVID-19 vaccines and science, role allocation during COVID-19 response, selective enforcement of COVID-19 directives, corruption in relief provision, and the brutality of security forces. These findings are in line with the scholarly works presented in the analytical framework.

Generally, these findings concur with observations that disasters can generate opportunities and trigger conflicts (Renner et al. 2007; Brundiers 2018). However, the economic and political opportunities presented by COVID-19 were exploited at the expense of public interests. The suppression of opposition politicians reduced the effectiveness of responses to the pandemic because the interests of constituencies represented by opposition politicians were excluded or inadequately addressed and response options were limited. While providing relief for campaign purposes increased volumes of relief items, concentrating them in areas of political interest promoted unequal access to relief items. Patronage compromised the COVID-19 response because tenders allocated to party loyalists in Uganda compromised the quality of relief items and led to many other relief challenges. The selective enforcement of COVID-19 measures undermined responses to the pandemic because it allowed the coronavirus to spread in situations where COVID-19 directives were not enforced. While bilateral and multilateral donations and loans facilitated the COVID-19 response, the loans increased debt burdens to an alarming level. The allocation of huge sums of money to non-health-related matters for political and personal interests denied the health sector the valuable resources needed for the COVID-19 response. By favouring themselves, relatives, and friends for cash relief grants, government staff denied people who needed the relief and served those illegible for the relief support. The corrupt procurement practices also led to siphoning off resources meant for COVID-19 response. The unethical business practices elevated private economic interest above public health, thereby hindering access of vulnerable groups to life-saving medical and public health interventions.

Conflicts and contestations also compromised public interests. The contestation of the vaccine left the vaccine-defiant individuals more vulnerable to severe effects of COVID-19 infection. Contestations of roles, power struggles, and blame games by actors in the COVID-19 response undermine the effectiveness of the response because they failed to effectively channel attention, resources, information, and organisational relationships in support of the response. However, some conflicts and contestation promoted public interests. For example, the contestation of selective enforcement of COVID-19 measures brings to light the unfairness and injustices associated with the enforcement. Although protests and contestations of corruption in the relief provision and human rights violations made little change in the response policies, they exposed corruption, discontent, and distrust people have about the COVID-19 response.

The findings also support the proposition that responses of actors to COVID-19 and its control measures are not only neutral and technical solutions serving the common good but also partial and contested events driven by political interests, and economic interests. In particular, the findings support many arguments. Firstly, the findings agree with the observation that government officials implemented COVID-19 policy based on the omniscient advice of health and epidemiological science. This is because the government responded to COVID-19 by adopting control measures recommended by medical experts and the World Health Organisation. However, the findings disagree with the pluralist view echoed in Boettke and Powell (2021) that government officials were disinterested and implemented COVID-19 policy based on economic science that efficiently balances tradeoffs for society to promote overall well-being. The findings also contradict the assumption of the benevolence of all actors (politicians, regulators, scientists, and the public) in the pandemic response, which was noted in Boettke and Powell (2021).

Instead, the findings embrace the view of public choice theorists that the state is itself an interest group wielding power over the policy process in pursuit of the interests of those running it, notably: elected public officials and civil servants. This is because actors, including governments and their employees, exploited the COVID-19 response to serve their political and economic interests. For example, the exploitation of the COVID-19 response for oppressing opposition politicians, the extortion of money from people by security officers, the extraction of money through scandalous procurement deals, and the use of relief distribution for political campaigns.