Abstract

This article reviews the literature between 2015 and 2022 on mental health disparities between children with gender and sexual minority parents and children with different-sex parents. Although most studies indicate that children with gender and sexual minority parents do not experience more mental health problems than children with different-sex parents, the results are mixed and depend on the underlying sample. The review highlights important shortcomings that characterize this literature, including cross-sectional survey samples, correlational methods, lack of diversity by country, and a lack of research on children with transgender and bisexual parents. Therefore, substantial caution is warranted when attempting to arrive at an overall conclusion based on the current state of the literature. Suggestions are provided that can guide academic work when studying mental health outcomes of children with gender and sexual minority parents in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Almost 50 years have passed since the American Psychiatric Association de-medicalized homosexuality in 1973. Recent estimates indicate that ~4.5% of the adult population, totaling more than 11.3 million adults in the United States, identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer—LGBTQ (Conron, 2019). In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage in all 50 states (Obergefell v. Hodges, 2015). Currently, between 2 and 3.7 million (about 29%) of LGBTQ individuals have children under the age of 18 (Gates, 2015). However, gender and sexual minority individuals still experience considerable legal and social challenges. For instance, despite long-standing opposition from the American Psychiatric Association, only 18 U.S. states have banned conversion therapy for minors (Streed et al., 2019). Gender and sexual minority individuals also experience workplace discrimination and harassment (Kaufman et al., 2022; Sears et al., 2021), even when they are highly educated (Mazrekaj, 2022). Gender and sexual minority (aspiring) parents often face even larger stressors. For instance, they may be disproportionately impacted by the high costs of adoption (typically between 15,000 and 40,000 USD) and IVF (one cycle may cost up to 13,000 USD) (Bell, 2019). Although different-sex couples can get reimbursed by insurance for IVF in some countries, this is not necessarily the case for lesbian couples, as the absence of a male partner may not count as a medical issue, depending on the situation at hand. Moreover, schools in some states outright deny enrollment of children with same-sex parents (Aviles, 2019).

The minority stress theory and the family systems theory provide some of the most frequently suggested mechanisms for mental health differences between children with gender and sexual minority parents and children with different-sex parents (see a review of theories by Farr et al., 2017). The minority stress theory posits that gender and sexual minority parents experience stress from navigating heterosexist societies.Footnote 1 These parents face unique stressors due to their sexual orientation such as experiences of prejudice, negative feedback from friends and family, and a prohibitive legal environment. Gender and sexual minority parents anticipate rejection not only of themselves, but they expect the rejection of their children, which adds stress unique to gender and sexual minority parents to general stress experienced by all parents (Gato et al., 2020; Jin and Mazrekaj, 2023). According to the family systems theory, families consist of interdependent subsystems, among which are the parental subsystem and the children subsystem (Stroud et al., 2011). As a result of spillover effects, the family systems theory posits that stress experienced by the parents is inextricably linked to the mental health of their children. Combining insights from the minority stress theory and the family systems theory, one can hypothesize that children with gender and sexual minority parents may experience more mental health problems than children with different-sex parents due to excessive stress on the family system.

In this paper, we review the literature between 2015 and 2022 on mental health disparities between children with gender and sexual minority parents and children with different-sex parents. As such, this review contributes to the earlier literature that included studies until 2015 that mostly found no differences in outcomes between children with gender and sexual minority parents and children with different-sex parents (Allen, 2015; Crowl et al., 2008; Fedewa et al., 2015; Manning et al., 2014; Schumm, 2016). This review also contrasts with other literature reviews about gender and sexual minorities (Imrie and Golombok, 2020; Reczek, 2020; Suárez et al., 2022; Thomeer et al., 2018) by focusing in detail on children’s mental health. Previous literature has shown that gender and sexual minority individuals are at a two- or three-times higher risk for mental disorders than heterosexual individuals (Wittgens et al., 2022). In this review, we aim to answer the question of whether children with gender and sexual minority parents have worse mental health than children with different-sex parents. In consideration of this question, we critically evaluate the methodological rigor with which the studies were conducted and provide suggestions that can guide future academic work on the mental health disparities between children with gender and sexual minority parents and children with different-sex parents.

Methods

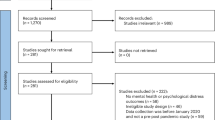

We conducted the review following The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al. 2021) as displayed in Fig. 1. The literature search was performed by the two authors separately. The databases used were PsycInfo, Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and Sociological Abstracts. We searched for the terms “same-sex”, “lesbian”, “gay”, “bisexual”, “transgender”, “trans”, and “queer” in combination with “parent* OR child*” and “health OR well-being”. To exclude studies that were reviewed in earlier literature reviews (Allen, 2015; Crowl et al. 2008; Fedewa et al. 2015; Manning et al. 2014; Schumm, 2016), we restricted the period of publishing to the years 2015 until 2022. We applied four more exclusion criteria when assessing the literature for eligibility. First, only peer-reviewed journal articles in English were considered. Second, the article had to explicitly mention a mental health outcome. For instance, articles that considered the total problem behavior score from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 1997) were not included as the total score measures both mental health and other problems. Third, the article should focus on children’s outcomes rather than only parental outcomes. Lastly, the article had to include a control group of children with different-sex parents. This led to 12 articles that met the inclusion criteria. In addition to databases, we also identified studies via other methods. Namely, we considered the references in the 12 identified articles, and also articles that cited the identified articles for potential inclusion. For citation searching, we applied the same four exclusion criteria to further assess the eligibility of articles. This led to 5 articles that met the inclusion criteria. In total, we included 17 articles in our review.

Results

Table 1 provides a detailed overview of the included studies. It should be directly noted that almost half of the studies identified sexual minorities by couple composition—such as same-sex or different-sex—as observed in column 5.Footnote 2 Parental sexual or gender identity or orientation was not directly observed in the majority of studies. Eleven out of 17 studies show that there are no statistically significant differences in mental health between children with gender and sexual minority parents and children with different-sex parents. One study (Green et al., 2019) found that children with same-sex male parents have fewer anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal issues than children with different-sex parents. However, the study used a non-representative sample of children conceived via surrogacy and should therefore be interpreted with caution. This is because gay fathers who cannot afford the high medical and legal costs of surrogacy are not represented in the sample. As such, the effects of high socioeconomic status are conflated with the effects of gender and sexual orientation of the parents.

On the other hand, several studies by Paul Sullins (2015a, 2015b, 2017), and also the study by Reczek et al. (2017), using large representative samples, indicate that children with same-sex parents have statistically significantly more emotional problems than children with different-sex parents. However, these large representative studies could only take a cross-sectional snapshot of the family structure in a given year. They were not able to distinguish between children who were raised by same-sex parents from birth and children whose parental situation had changed over time due to separation, the coming out of a parent, or other factors. Many children live with a same-sex couple after a gay parent’s separation from a different-sex partner, and therefore they were not raised from birth by same-sex parents. This is an important limitation because events such as parental separation may exert an independent negative effect on mental health outcomes (McLanahan et al., 2013). Consequently, studies based on cross-sectional data may mistakenly attribute a negative coefficient to living with same-sex parents (Mazrekaj et al., 2020).

Further, the only study that considered children with bisexual parents (Calzo et al., 2019) found that children with these parents have more emotional and mental health difficulties than children with different-sex parents, whereas no statistically significant differences were found between children with same-sex parents and children with different-sex parents. The two studies that studied children with transgender parents (Condat et al., 2020; Imrie et al., 2021) suggest no discrepancies with children with cisgender parents.

Discussion

Table 1 has revealed substantial limitations in the current research on mental health outcomes of children with gender and sexual minority parents and children with different-sex parents. We also conduct a more formal risk of bias assessment in Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2. We rated all the studies to have either a serious or critical risk of bias. These limitations reveal significant areas of improvement that can be addressed by future research. Although we attempted to include studies with a wide range of gender and sexual minorities, almost all studies were about same-sex male and same-sex female parents. Only two studies included transgender parents and only one study included bisexual parents. Even when the studies included both same-sex male and same-sex female parents, they were virtually always grouped, and the vast majority of parents were same-sex female parents. Essentially, this review has brought to light that we know very little about the mental health of children of transgender and bisexual parents, but also same-sex male parents. It is of utmost importance that future research also considers separating different gender and sexual minority groups and puts more emphasis on children with transgender and bisexual parents.

Another important limitation is that most studies, namely 12 out of 17 studies, are situated in the United States. This is problematic as research has shown that country differences may be related to substantial differences in findings in the literature (Schumm, 2018). Hence, future research should include countries other than the United States, particularly countries with a different legal and social environment towards gender and sexual minority parents.

Methodologically, this research is still in its infancy. Many of the studies used rather small samples that were not representative of the population. Only one study (Sullins, 2016) had a longitudinal design. As mentioned previously, without a longitudinal design, it is not possible to separate the influence of gender and sexuality minority parents from the influence of other factors such as parental divorce. Future research should use longitudinal datasets that include information on with whom the child resided each year from birth until the outcomes are measured (see for instance Mazrekaj et al., 2020). This would enable the researcher to study whether children were raised by gender and sexual minority parents from birth or solely after a separation of the gender and sexual minority parent with a previous heterosexual partner.

Further, only one study (Mazrekaj et al., 2022) used a method other than the classic correlational methods such as regression analysis. No attempt was made in any of the studies to characterize potential selection bias. Future research should focus more on innovative quasi-experimental methods such as treatment effect bounds (Mazrekaj et al., 2020) to determine the extent to which the found coefficients have a causal interpretation. Finally, all reviewed studies used survey data that are prone to potential reporting and sampling bias. We recommend that future studies consider administrative data on the use of antidepressants and medical health care that are increasingly becoming available in European countries such as the Netherlands and Nordic countries. These large datasets include the entire population of a country with very little measurement error. As such, these data may prove very useful when studying mental health outcomes of children with gender and sexual minority parents in the future.

With these caveats in mind, the findings of this review mostly indicate that children with gender and sexual minority parents do not experience more mental health problems than children with different-sex parents. This finding suggests that there seems to be considerable resilience within the family systems of minority families to buffer against the negative effects of minority stress (Sarah and MacPhee, 2017). Further research should investigate the coping mechanisms underlying this resilience of both the gender and sexual minority parents and their children. In any case, understanding how children with gender and sexual minority parents fare in terms of mental health can help health professionals and parents identify and address any issues early. Furthermore, studies that explore this area can help to combat the stigma and discrimination faced by sexual and gender minorities. Thus, it is important to continue to conduct research in this area to gain a clearer understanding of the mental health issues faced by children with gender and sexual minority parents. These studies can help inform policies and practices designed to support and protect these children and their families.

Data availability

This article is a literature review and hence data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Notes

Note that, for ease of comparisons, we still use the wording same-sex and different-sex regardless of whether the parents were self-identified or identified by the researcher by couple composition, but Column ‘Identification’ in Table 1 shows how the parents were actually identified.

References

Allen D (2015) More heat than light: a critical assessment of the same-sex parenting literature 1995–2013. Marriage Fam Rev 51(2):154–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2015.1033317

Aviles G (2019) Kansas Catholic school rejects kindergartner with same-sex parents. NBC News https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/kansas-city-catholic-school-rejects-kindergartner-same-sex-parents-n980781

Baiocco R, Santamaria F, Ioverno S, Fontanesi L, Baumgartner E, Laghi F, Lingiardi V (2015) Lesbian mother families and gay father families in Italy: family functioning, dyadic satisfaction, and child well-being. Sex Res Soc Policy 12(3):202–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-015-0185-x

Bell AV (2019) “Trying to have your own first; it’s what you do”: the relationship between adoption and medicalized infertility. Qual Sociol 42:479–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-019-09421-3

Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, Coleman E (2013) Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am J Public Health 103(5):943–951. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241

Bos HM, Knox JR, van Rijn-van Gelderen L, Gartrell NK (2016) Same-sex and different-sex parent households and child health outcomes: findings from the national survey of children’s health. J Dev Behav Pediatr 37(3):179–187. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000288

Bos H, van Gelderen L, Gartrell N (2015) Lesbian and heterosexual two-parent families: adolescent–parent relationship quality and adolescent well-being. J Child Fam Stud 24:1031–1046. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9913-8

Calzo JP, Mays VM, Björkenstam C, Björkenstam E, Kosidou K, Cochran SD (2019) Parental sexual orientation and children’s psychological well-being: 2013–2015 National Health Interview Survey. Child Dev 90(4):1097–1108. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12989

Cheng S, Powell B (2015) Measurement, methods, and divergent patterns: reassessing the effects of same-sex parents. Soc Sci Res 52:615–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.04.005

Condat A, Mamou G, Lagrange C, Mendes N, Wielart J, Poirier F, Medjkane F, Brunelle J, Drouineaud V, Rosenblum O, Gründler, Ansermet F, Wolf J-P, Falissard B, Cohen D (2020) Transgender fathering: children’s psychological and family outcomes. PLoS ONE 15(11):e0241214. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241214

Conron KJ (2019) Adult LGBT population in the United States. Fam Equal https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LGBT-Adult-US-Pop-Mar-2019.pdf

Crowl A, Ahn S, Baker J (2008) A meta-analysis of developmental outcomes for children of same-sex and heterosexual parents. J GLBT Fam Stud 4(3):385–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504280802177615

Farr RH, Tasker F, Goldberg AE (2017) Theory in highly cited studies of sexual minority parent families: variations and implications. J Homosex 64(9):1143–1179. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1242336

Fedewa AL, Black WW, Ahn S (2015) Children and adolescents with same-gender parents: a meta-analytic approach in assessing outcomes. J GLBT Fam Stud 11(1):1–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2013.869486

Gamarel KE, Reisner SL, Laurenceau J-P, Nemoto T, Operario D (2014) Gender minority stress, mental health, and relationship quality: a dyadic investigation of transgender women and their cisgender male partners. J Fam Psychol 28(4):437–447. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037171

Gartrell N, Bos H, Koh A (2018) National longitudinal lesbian family study—mental health of adult offspring. New Engl J Med 379(3):297–299. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1804810

Gates GJ (2015) Marriage and family: LGBT individuals and same-sex couples. Future Children 25(2):67–87. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2015.0013

Gato J, Leal D, Coimbra S, Tasker F (2020) Anticipating parenthood among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual young adults without children in Portugal: predictors and profiles. Front Psychol 11:1058. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01058

GLAAD (2023) GLAAD media reference guide, 11th edn. GLAAD

Goodman R (1997) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38(5):581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Green R-J, Rubio RJ, Rothblum ED, Bergman K, Katuzny KE (2019) Gay fathers by surrogacy: prejudice, parenting, and well-being of female and male children. Psychol Sexual Orientat Gend Divers 6(3):269–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000325

Hendricks ML, Testa RJ (2012) A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the minority stress model. Prof Psychol: Res Pract 43(5):460–467. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029597

Imrie S, Golombok S (2020) Impact of new family forms on parenting and child development. Annu Rev Dev Psychol 2:295–316. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-devpsych-070220-122704

Imrie S, Zadeh S, Wylie K, Golombok S (2021) Children with trans parents: parent-child relationship quality and psychological well-being. Parenting 21(3):185–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2020.1792194

Jin Y, Mazrekaj D (2023) The association between parenthood and health for same-gender and different-gender couples. Mimeo

Kaufman G, Auðardóttir AM, Mazrekaj D, Pettigrew RN, Stambolis-Ruhstorfer M, Vuckovic Juros T, Yerkes MA (2022) Are parenting leaves available for LGBTQ parents? Examining policies in Canada, Croatia, France, Iceland, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. In: Dobrotić I, Blum S, Koslowski A (eds) Parenting and social inequalities in a global perspective. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 325–337

Manning WD, Fettro MN, Lamidi E (2014) Child well-being in same-sex parent families: review of research prepared for American Sociological Association Amicus Brief. Popul Res Policy Rev 33:485–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-014-9329-6

Mazrekaj D (2022) Inclusion of LGBT+ researchers is key. Nature 605(7908):30. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-01187-z

Mazrekaj D, De Witte K, Cabus S (2020) School outcomes of children raised by same-sex parents: evidence from administrative panel data. Am Sociol Rev 85(5):830–856. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122420957249

Mazrekaj D, Fischer MM, Bos HM (2022) Behavioral outcomes of children with same-sex parents in the Netherlands. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(10):5922. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105922

McConnachie AL, Ayed N, Foley S, Lamb ME, Jadva V, Tasker F, Golombok S (2021) Adoptive gay father families: a longitudinal study of children’s adjustment at early adolescence. Child Dev 425–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13442

McLanahan S, Tach L, Schneider D (2013) The causal effects of father absence. Annu Rev Sociol 39:399–427. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145704

Meyer IH (2003) Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 129(5):674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) 11-556 (Supreme Court of the United States, US, June 26)

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev 10(1):89. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Reczek C (2020) Sexual- and gender-minority families: a 2010 to 2020 decade in review. J Marriage Fam 82(1):300–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12607

Reczek C, Spiker R, Liu H, Crosnoe R (2016) Family structure and child health: does the sex composition of parents matter? Demography 53:1605–1630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0501-y

Reczek C, Spiker R, Liu H, Crosnoe R (2017) The promise and perils of population research on same-sex families. Demography 54:2385–2397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-017-0630-y

Sarah P, MacPhee D (2017) Family resilience amid stigma and discrimination: a conceptual model for families headed by same-sex parents. Fam Relat 26-40. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12296

Schumm WR (2016) A review and critique of research on same-sex parenting and adoption. Psychol Rep 119(3):641–760. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294116665594

Schumm WR (2018) Same-sex parenting research: a critical assessment. Wilberforce Publications, London, UK

Sears B, Mallory C, Flores AR, Conron KJ (2021) LGBT people’s experiences of workplace discrimination and harassment. UCLA School of Law Williams Institute. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/lgbt-workplace-discrimination/

Streed CG, Anderson SJ, Babits C, Ferguson MA (2019) Changing medical practice, not patients—putting an end to conversion therapy. N Engl J Med 381:500–502. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1903161

Stroud CB, Durbin EC, Wilson S, Mendelsohn KA (2011) Spillover to triadic and dyadic systems in families with young children. J Fam Psychol 25(6):919–930. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025443

Suárez MI, Stackhouse EW, Keese J, Thompson CG (2022) A meta-analysis examining the relationship between parents’ sexual orientation and children’s developmental outcomes. J Fam Stud 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2022.2060121

Sullins DP (2015a) Emotional problems among children with same-sex parents: difference by definition. Br J Educ Soc Behav Sci 7(2):99–120. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJESBS/2015/15823

Sullins DP (2015b) The unexpected harm of same-sex marriage: a critical appraisal, replication and re-analysis of Wainright and Patterson’s studies of adolescents with same-sex parents. Br J Educ Soc Behav Sci 11(2):1–22. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJESBS/2015/19337

Sullins DP (2016) Invisible victims: delayed onset depression among adults with same-sex parents. Depression Res Treat https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2410392

Sullins DP (2017) Sample errors call into question conclusions regarding same-sex married parents: a comment on “family structure and child health: does the sex composition of parents matter?”. Demography 54:2375–2383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-017-0616-9

Thomeer MB, Paine EA, Chénoia B (2018) Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender families and health. Sociol Compass 12(1):e12552. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12552

Wittgens C, Fischer MM, Buspavanich P, Theobald S, Schweizer K, Trautmann S (2022) Mental health in people with minority sexual orientations: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 145(4):357–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13405

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DM and YJ have contributed equally to all parts of the research process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article is a literature review and hence the authors of this article did not perform any studies with human participants.

Informed consent

This article is a literature review and hence the authors of this article did not perform any studies with human participants that required informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mazrekaj, D., Jin, Y. Mental health of children with gender and sexual minority parents: a review and future directions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 509 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02019-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02019-9