Abstract

The ascent of housing booms and their impact on firm innovation has become a focal point of research, fueled by the remarkable upsurge in housing prices that have been witnessed across global over the past few decades. Despite the attention given to this subject, there has been limited exploration of the spillover effects of housing macroprudential policy (HMP) on firm innovation, which aims to regulate housing booms and ensure financial stability. In this study, we examine the relationship between HMP and firm innovation using panel data from Chinese firms located in 54 cities for the period spanning 2010 to 2019. Our empirical results reveal that tightened HMP promotes firm innovation and is robust to alternative measurements, additional fixed effects, Heckman regression, and IV regression. Moreover, our mechanism analysis demonstrates that HMP promotes firm innovation by reducing leverage and encouraging cash holdings. Further examination of city-level heterogeneity suggests that firms located in areas with lower housing dependency and limited financial development benefit more from HMP’s positive-effect on firm innovation. This paper contributes to the gap in the existing literature that neglects the spillover effect of HMP on firms’ innovation activities. Our findings also provide practical implications for both policymakers and businesses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fueled by the remarkable upsurge in housing prices that have been witnessed across global over the past few decades, the housing macroprudential policy (HMP) plays an increasingly important role in alleviating the financial risks rooted in the housing bubbles (He et al., 2016). Despite a great body of research documenting the effect of HMP on the domestic financial markets (Allen et al., 2020; Hoesli et al., 2020) and its potential effect on international financial markets (Badarau et al., 2020; Chari et al., 2022), micro-level empirical evidence on the effect of HMP is scarce. Existing research has largely neglected the spillover effect of HMP on the local firms’ behavior, especially on firms’ innovation activities, which play a primary determinant in economic growth (Solow, 1957). Therefore, this paper attempts to fill this gap and answer the question of whether and how the regulation on housing markets could affect firms’ innovation activities, by analyzing the city-firm combined dataset in China over a period of dynamically changing HMP.

China, as the largest emerging economy, has experienced a long period of housing boom accompanied by rapid development in R&D investments (Chen and Wen, 2017). To address concerns related to the housing market, Chinese local governments have implemented various regulations over the past decades. This regulatory environment provides an opportunity to investigate the relationship between HMP and firm innovation. Notably, we observe the following stylized facts: before 2014Footnote 1, the firm innovation increased weakly and the housing boom maintained with average annual growth of over 10%. However, after 2015, the R&D activity of firms increased sharply, coinciding with fluctuating housing pricesFootnote 2, indicating a possible crowd-out effect of high housing prices on innovation. Against this background, it is crucial to examine whether HMP can promote firm innovation, as this question holds significant implications for understanding economic growth and achieving policy equilibrium.

We employ a firm-level panel dataset combined with city-level HMP measures to examine such an effect empirically. Our sample covers 54 cities come from 28 provinces and 1947 listed firms in China between 2010 to 2019. We analyze the impact of HMP on firms’ R&D investments. Our results indicate that HMP has a significant promotive effect on firms’ innovation activity, which is in line with the crowd-out effect of the housing boom on firm innovation. We also find that the firms’ reactions vary across different industries regarding the impact of HMP on innovation. Further, mechanism analysis indicates that HMP promotes firm innovation by reducing firm leverage and encouraging cash holding. Further analysis shows the heterogeneous effect of HMP at the city level. We find the promotion effect of HMP is more pronounced for firms located in cities with underdeveloped financial systems or highly housing-independent regions.

Our research distinguishes from the existing literature in the following ways: First, we provide novel empirical evidence linking HMP and firm innovation in emerging markets. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to document such a positive effect of HMP on firm innovation. Given HMP intends to mitigate financial risks, our findings provide insights into understanding the potential spillover effect of macroprudential policy on firms’ activities. Second, we uncover the two possible channels of how macroprudential policy promotes firms’ innovation. We show that tightening HMP leads to improved financial structure and utilizing firms’ investment efficiency by reducing firms’ leverage and encouraging cash holdings, and eventually promoting firms’ innovative investments. Finally, our study extends the research on macroprudential policy on firm activities by including city-level heterogeneity. This fresh perspective enhances our comprehension of the relationship between HMP and firm-level outcomes, thereby shedding light on broader implications for policymaking and economic stability.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section “Literature review and hypothesis development” reviews the literature and develops a hypothesis. Section “Data and methodology” illustrates the data and empirical specification. In section “HMP and firm innovation”, we discuss the baseline results. Section “Further analysis” studies the role of housing dependency and financial development level. Finally, section “Conclusions” concludes.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Institutional background of HMP in China

In response to the housing boom and the associated financial risk, macroprudential policies targeting the real estate market have been implemented in both advanced and emerging economies. Such policies are designed to mitigate systemic risks and a great deal of which focus on the housing sector given that most asset bubbles are made in the real estate sector. The implementation of such HMP involves tools such as dynamic loan-loss provisions, loan-to-value (LTV), and debt-to-income (DTI) ratios, aiming to enhance the resilience of both financial institutions and borrowers when confronting aggregate shocks (Ayyagari et al., 2018). The HMP framework employs these tools and promotes a stable and healthy housing market while minimizing the risk that it poses to the economy.

China’s HMP employs a combination of the above measures to reduce the risks associated with excessive leverage and speculative activity and to curb the non-living demand in the real estate market. One of the key tools in this framework is the loan-to-value (LTV) ratioFootnote 3. LTV ratio in China is different for participants with various numbers of real estate. Generally, the LTV ratio is higher if the buyer has no real estate assets, which allows them to borrow more loans from the bank. Apart from the general tools, China has done a lot to maintain financial stability. For example, China introduces macroprudential tools to real estate firms to limit their excessive risk-taking behaviors in 2020. By strictly regulating their leverage ratio and cash-short debt ratio, the wild expansion of real estate sectors in China has been taken under control. At the end of 2020, China implements a real estate loan concentration management system that mandates financial institutions to maintain their real estate loan ratios below a specified threshold. The threshold varies depending on the banks’ size and is designed to prevent excessive exposure to risk in the housing market.

HMP and innovation

Existing research has extensively studied the direct impact of HMPs on housing markets and suggest that these policies can lead to a reduction in housing prices and curb asset bubbles driven by overinvestment in the real estate sector (Alpanda and Zubairy, 2017; Akinci and Olmstead-Rumsey, 2018). Apart from direct investment into households, firms play an important role in the real estate sector and are involved in various financial activities, such as financing through real estate mortgages and investing in the sector for additional returns. There is growing literature discussing the impact of real estate investment by non-financial firms. Demir (2009) finds that financial investment including housing investment may have a crowd-out effect on the fixed investment due to return gap and reversibility. Similarly, Zhu et al. (2019) suggest that local real estate investment may impede regional innovation. However, Chaney et al. (2012) argue that real estate investments can be regarded as a kind of guarantee, which enables firms to get more financing resources and thus may promote innovation. Despite the substantial and insightful literature on firm innovation, this line of research has largely overlooked the effect of HMP on firm innovation.

If we look at firms’ innovation input as a substitution to firms’ housing investments, HMP could lead to increasing substitution and hence associate with an increment in firm innovation. A stricter HMP activity could effectively lower the returns of real estate investment (Qi et al., 2022), leading firms to reallocate their portfolio and increase the investment in innovation for long-term value to avoid potential uncertainty (Dicks and Fulghieri, 2021). There are also the possibilities that HMP may crowd-out firm innovation due to the potential negative effects of fluctuating house prices on firms’ balance sheets and available funds if they already invest too much in real estate sectors (Rong et al., 2016). Based on these observations, we propose that:

Hypothesis 1(H1): HMP will have a positive effect on firm innovation.

HMP, housing dependency, and innovation

The relationship between housing investment and firm innovation can be characterized by two effects: the crowd-out effect and the collateral effect. The crowd-out effect suggests that firms may prefer to invest in housing markets with higher returns rather than investing in innovation, leading to a decline in the latter (Miao and Wang, 2014; Rong et al., 2016). Conversely, the collateral effect indicates that growing investments in real estate could increase firm’s financing capacity by providing high-value collateral, leading to enhanced investment and innovation (Chaney et al., 2012; Mao, 2021). Taking into account both of these effects, the impact of HMP on firm innovation varies depending on the extent to which local governments rely on the housing market. For firms locate in cities that rely heavily on real estate sectors, HMP could have limited influence on innovation activities. Further, the balance of local government may be subjected to tightened HMP. Lower housing prices and subsequently, lower tax incomes, would lead to fewer support funds from the government for firms to innovate (Wei et al., 2023). By contrast, firms located in cities with less reliance on the housing market may get more motivated to invest in innovation due to the stronger effect of HMP on housing investment. We, therefore, propose that:

Hypothesis 2(H2): HMP will have a heterogeneous impact on firms in different regions. The effect of HMP on firms’ innovation investment will be more pronounced in cities with lower housing dependencies.

HMP, financial development, and innovation

Given the high uncertainty and risky nature associated with innovation activities, financing capacities play a key role in affecting firm R&D activities (Ayyagari et al., 2011; Chen and Yoon, 2021). Therefore, the development of local financial systems could remarkably alter the effect of HMP on firms’ innovation (Cerutti et al., 2017). Firms located in cities with better financial development tend to have better access to funding (Ding et al., 2022), making them less susceptible to the effects of HMP. However, this pattern may not hold in regions with less developed financial systems. Generally, weaker financial development is associated with greater shadow banking activities and lower efficiency in the financial system. Firms located in such regions often face tighter financial constraints and may resort to more off-balance sheet financing through the shadow banking sector (Moosa, 2017). However, HMP could potentially mitigate these issues by providing regulatory mechanisms to redirect the behavior of both banks and consumers toward more sustainable lending practices. Tightening actions of HMP could prevent funds from leaking into shadow banking sectors (Gebauer and Mazelis, 2019), thus improving firms’ innovation by providing short-term funds to finance innovation activities. Hence, we propose that:

Hypothesis 3(H3): HMP will have a heterogeneous impact on firms in different regions. The effect of HMP on firms’ innovation investment will be more pronounced in regions with less developed financial systems.

Data and methodology

Data

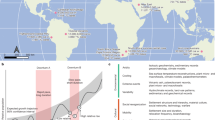

Our sample period in this paper is from 2010 to 2019 to avoid major shocks (e.g., the financial crisis of 2008 and the COVID-19 outbreak at the end of 2019). Our dataset contains information on the R&D activities of Chinese-listed firms and the implementation of HMP tools in various regions and cities. The firm-level data are obtained from the WIND database, CSMAR database. The data of implementation of HMP are collected from disclosure from the People’s Bank of China, and local government public information disclosure. We merge the macroprudential policy into firm-level panel dataFootnote 4. We exclude the firms in the finance industry and real estate industry, which are relatively weaker in innovation and experience direct shock of the HMP, from our sample. We exclude the warning stocks and delisted stocks (Stock names containing ST\*ST\PT) as well. Finally, firms with serious data loss (e.g., main data missing at least 3 consecutive years) are eliminated from our sample. To avoid the effect of extreme values, firm-level continuous variables are winsorized at a 1% level. Following the procedure, we obtain 13,717 firm-year observations from 54 cities of 28 provincesFootnote 5 (see Fig. 1) as our main sample.

Variables

HMP in China

Following existing literature (Allen et al., 2020; Yang and Suh, 2021), we focus on the change of loan-to-value (LTV) and debt-to-income (DTI)Footnote 6 on housing markets as the key measurements for HMP actions. Such measurement could comprehensively capture the quarterly coverage of macroprudential policy over 54 cities in China. We construct categorical variables to capture the dynamic of HMP mainly for two reasons. First, the continuity and availability of continuous data differ across various HMP policy tools. For example, China first introduced LTV regulation for residents in 2003 and began to implement controls on mortgage ratios for financial institutions in 2012. Second, it enables us to comprehensively capture the dynamic nature of macroprudential policy in the housing market by considering both the tightening and the loosening actions for the HMP tools (e.g., LTV and DTI) at a quarter frequency. We define the seasonal city-level HMP variables as follows:

We aggregate the seasonal city-level frequency of HMP to year-level data by summing the times the HMP tools are implemented. Hence, the variable of HMP_T ranges from −4 to 4 with the changing unit of 1, which indicates that the city implements HMP tools sequentially over the course of a yearFootnote 7. In addition, we construct two dummy variables HMP_tight (equals 1 if housing macroprudential tightens, 0 otherwise) and HMP_loose (equals 1 if housing macroprudential relaxes, 0 otherwise) to capture the asymmetric effects of HMP. In the check for robustness, we calculate the average LTV ratios and provide a continuous measurement of HMP.

Figure 2 shows the actions of HMP in our sample from 2010 to 2019, which could provide a scene toward housing market regulation. Before 2013, the majority of our sample cities were being regulated with positive housing macroprudential policies, which implies that the housing market was strictly regulated at national level during this period. Moreover, this pattern has changed since 2014 when the China stock bubble burst. Most cities started to lessen macroprudential policy and maintained this attitude until 2017. From 2017 to 2019, the Chinese government has come back to the pattern of regulating the housing market, while the strength and scope of the policy have been reduced compared to the previous period following the crisis in 2008.

Firm innovation

Following Becker (2015), we use R&D investment (calculated as the ratio of R&D investment to the operating income) instead of the number of patents to measure firm innovation engagement, which could better capture the dynamic relationship between macro-financial policies and firm innovation activity. We also take the natural logarithm of R&D investment at year t as the alternative measure of firm innovation for robust tests.

Empirical specification

To examine the impact of HMP on firm innovation, we estimate the baseline specification model in Eq. (2) with the OLS method as follows:

Where R&Di,t+1 is firms’ innovation investment in year t + 1 measured by the R&D/Income ratio. HMPi,k,t is the categorical variable to measure the dynamics of HMP for firm i locates in city k, which takes a positive value if the HMP is tightened, and takes a negative value if the HMP is loosened. Controlsi,t is a set of variables that influence firm innovation actions from both firm-level and city-levelFootnote 8. c is the constant. Year-fixed effect (μt) and industry-fixed effect (τj) are considered as well. A positive α1 indicates that tightened HMP leads to an increase in firm innovation.

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the summary statistical results of our studyFootnote 9. The R&D/income (%) in our sample ranges from 0.020% to 25.230% with a mean value of 4.755%, indicating that the average firm innovation investment in China is still relatively low and the difference among various firms is significant. As for our explanatory variable, we can see that the mean value of HMP_T is 0.204, which implies that the average attitude of Chinese government towards the housing market is active and tightening regulation. In particular, we could observe substantial differences in the size, growth rate, age, and employment costs between our sample firms (large standard deviations compares to the average). Thus, we further discuss the heterogeneity in the following regression analysis according to the firm characteristics.

HMP and firm innovation

Benchmark results

Table 2 presents the estimation results of Eq. (2). The results of univariate regression are given in column (1) and the results of multivariate regression are shown in column (2). The estimator of HMP_T is significantly positive in both column (1) and column (2), which indicates that tightening HMP could significantly promote firms’ innovation activity. An estimator value of 0.087 (t-statistics = 1.95) indicates the implementation of tightening HMP may lead to an 8.7% marginal increase in local firms’ R&D investment relative to the operation income in the following year, which provide our results with economic significance.

Column (3) ~ (4) reports the asymmetric effects of HMP in various directions, including both tightening and loosening actions. The results indicate that a tightening of HMP has a significant positive impact on firms’ R&D expenditures in the following year, while loosening HMP has a more substantial impact on reducing firm innovation, suggesting that a more relaxed policy environment can negatively impact firms’ investment decisions due to fewer restrictions on real estate investment and financial activities (Hoesli et al., 2020).

Potential mechanisms

To further understand how HMP affects firm innovation, we construct the equation to document the potential mechanisms following Alesina and Zhuravskaya (2011) and Zhao et al. (2010):

Where Mediatori,t indicates the mediators, including leverage and cash holding for firms. Other variables are specified as identical to those in Eq. (2). If the estimated α1 in Eq. (3) is insignificant or the magnitude is different from the estimation from Eq. (2), we can document the potential mechanisms.

Firm leverage

We propose that firm leverage (Lev, measured by the ratio of liability to asset) can be an important mechanism linking HMPs and firm innovation since firm leverage may affect firms’ investment decisions (Nemlioglu and Mallick, 2021). Firms with higher leverage may face credit default risk and subsequently reduce their investment in innovation activities requiring long-term commitments and continuous expenditure. Moreover, HMP can affect firms’ leverage by affecting the availability and cost of credit in the economy. For example, a tightening of HMPs may be associated with a decrease in firm leverage due to fewer funds available and higher financing costs (Liang et al., 2017). In turn, changes in firms’ leverage may affect firms’ innovation by influencing their investment decisions.

Table 3 presents the mechanism analysis results. As shown in column (2), the leverage significantly impedes firm innovation. While the estimator for the effect of HMP decreased and show no statistical significance after controlling for firm leverage compared with the baseline results. The results show that tightened HMP effectively decreases firm leverage, which is consistent with the findings of Yang and Suh (2023). Based on these findings, we argue that HMP promotes innovation by reducing firms’ leverage.

Cash holding

We take firms’ cash position as an additional key mediator between HMP and firm innovation (Kang et al., 2021). Higher cash holding can provide firms with greater financial flexibility and stability, which can in turn increase their ability to invest in innovation activities. With more cash on hand, firms can better absorb unexpected shocks or economic downturns and have greater resources to invest in new products, services, or technologies. In this way, firms are intending to increase their cash holding when confronted with tightened HMP for the sake of economic uncertainty and avoidance of risks, which may contribute to firms’ R&D expenditure next year.

Column (3) in Table 3 reports the role of cash holdings (as measured by the ratio of net operating cash to total assets). The estimator of cash is significantly positive at the 1% level, suggesting that cash plays a key role in promoting firm innovation. Additionally, we find the estimator for the effect of HMP is smaller and insignificant after including the cash holding into our model. Taken together, our results indicate HMP enhances firm innovation by increasing firms’ cash holding.

Industry heterogeneity analysis

Given the huge differences in housing investments and R&D investments for firms in various industries, we estimate the industry heterogeneity of HMP on firm innovation. The industry heterogeneity results are shown in Table 4. The results show that the firms in the ‘Transportation & Delivery’ and ‘Manufacturing’ industry are more likely to increase R&D investment after the HMP implementation, while the impact of HMP on firm innovation is negative for those firms in the ‘Information technology & service’ industry and ‘Farm, forest, and fishing’ industry. We find no significant impact of HMP on innovation for firms in the ‘Health and social work’ industry. Such results indicate that the positive effect of HMP on firm innovation is mainly reflected in firms from asset-heavy industries.

The aggregated obs in this heterogenous analysis are less than whole sample since the numbers of firms in some industries are inadequate to satisfy the panel regression requirements.

.Robustness check

To ensure our results are robust, we perform several robustness checks and report related results as follows. The results indicate our baseline findings are robust, that the HMP has a significantly positive impact on firm innovation activity.

(a) Endogeneity tests

To alleviate the potential concerns about sample selection bias and reverse causal problems, we employ instrumental two-stage least square regression (IV-2SLS), and the Heckman regression methodFootnote 11 to estimate the benchmark model. Dynamic models are included as well.

Following previous studies (Zhang and Zou, 1998; Rong et al., 2016), we employ the residential land area (RLA) of city k at year t as the instrumental variable for HMP_TFootnote 12. Residential land area is associated with the supply of housing as it reflects the availability of land for residential development, which in turn affects housing prices for households. Therefore, RLA is a reasonable instrument for HMP as it is positively associated with the dynamics of HMP with little influence on firm behaviors.

The results of addressing endogenous concerns are reported in Table 5, in which column (1) shows the IV-2SLS results, column (2) is the Heckman results, and columns (3) and (4) give the dynamic model results with OLS. Overall, the effect of HMP on firm innovation remains significantly positive at a specific level.

(b) Alternative measurement of innovation

We employ the natural logarithm of R&D investment as the alternative measure of firm innovation activity. Column (1) ~column (2) in Table 6 shows the regression results of alternative measurement of innovation. We find that the implementation of HMP would positively affect firm innovation investment, which is consistent with our baseline results.

(c) Alternative measurement of HMP

We identify the HMP by using the real estate loan down payment ratio for city kFootnote 13. Column (3)–column (4) in Table 6 shows the regression results of alternative measurement of HMP. Moreover, we combine the alternative measurement of innovation and HMP in column (5)–column (6). The estimators of HMP remain positive and statistically significant, which again indicates that HMP enhances firm innovation.

(d) Additional fixed effects

We consider both city-fixed effect and industry × year-fixed effect to ensure the robustness of our results. The regressions are shown in Table 7, where column (1) includes city-fixed effect and year-fixed effect, column (2) considers city-fixed effect, industry-fixed effect, and year-fixed effect, and column (3) includes industry × year-fixed effect. All the coefficients of HMP_T are significantly positive, suggesting that our baseline results are robust.

Further analysis

In this section, we extend the baseline model Eq. (2) and examine the role of housing dependency and financial development at the city level. In our sample period, there is a significant variation in firm innovation activity between different levels of housing dependency and financial developmentFootnote 14. Thus, we intend to explore whether the HMP could diminish the gap between firm innovation levels in different regions. Following previous studies (Balsmeier et al., 2017; Demir et al., 2022), we employ the reduced-form specification as follows:

Where Li,t is the moderating variable that may affect firm R&D activity with an aspect to HMP. α3 is our main parameter: if α3 < 0, the positive effect of HMP on firm innovation would be alleviated with a higher value of Li,t. The moderating variable includes the following: housing dependency, captured by the ratio of housing market investment to gross domestic production, equals one if the city is highly dependent on housing markets (High HD); and financial development, measured by the ratio of local finance loan balance to GDP, equals one if the financial development is better than the average level in our sample (Fin).

HMP, housing dependency, and innovation

The empirical results of the role of housing dependency are given in Table 8. In column (1) and column (2), we reestimate the Eq. (2) in subsample by the various level of housing dependency among sample cities. Moreover, in column (3), we estimate Eq. (4) in the full sample to explore the role of housing dependency. The estimator of High HD × HMP_T is significantly negative, which indicates the effect of HMP is more pronounced on firms from lower housing-dependent cities. In addition, results in column (1) indicate that firms with high dependency on housing markets are not significantly affected by the HMP. Such findings provide support to H2. In cities with high dependency on the housing industry, local governments adopt less strict HMP to regulate the real estate marketFootnote 15 and firms would suffer more from the crowd-out effect of HMP. As a result, firms located in these regions would react less to tightened HMP in terms of innovation due to the deflation of housing investment and lack of sufficient cash or collateral.

Furthermore, we examine the marginal effects of HMP on firm innovation at a different level of housing dependency. The estimator results are shown in Fig. 3, which shows the predicted value of firm innovation with the variation of HMP. The HMP positively affects the firm innovation activity in lower housing-dependent areas with an upward dotted line. While for those firms with higher dependency on housing markets cities, the predicted value of R&D activity decreases sharply with the increase of positive HMP, which reinforces the findings in interaction estimation. It’s noteworthy that the value of predicted firm innovation in low housing-dependence regions would surpass firms in high housing-dependence areas. This finding indicates that HMP may have a significant structural impact on firm innovation, which provides evidence to extend the reallocation effects of HMP (Fig. 4).

HMP, financial development, and innovation

Table 9 presents the results of examining the role of financial development in affecting HMP and firm innovation. In column (1) and column (2), we estimate the Eq. (2), respectively, in subsample by the various financial development performance. We estimate Eq. (3) in the full sample to explore the role of financial development as shown by column (3). The coefficient of Fin × HMP_T is significantly negative, suggesting that the promotion effect is more pronounced for firms in areas with less financial development. In contrast, the results from column (1) suggest that firms operating in areas with well-developed financial systems may not be affected by HMP.

These findings further evidence that better development of credit markets may discourage firm innovation as proposed by Hsu et al. (2014). Tightened HMP may have less effect on available financial resources for those cities with better financial development due to not affected banks (Jiménez et al., 2017) and increased financial innovation (Merton, 1995). While for the firms located in areas with less financial development, tightened HMP may help in reducing the scale of shadow banking activities, improving bank stability (Ouyang and Wang, 2022), and directing more funds to support firm innovation. Based on these observations, the promotion effect of HMP on firm innovation is more pronounced for those in areas with less financial development.

Conclusions

In this paper, we assess the spillover effect of housing macroprudential policy on firm innovation. Taking advantage of a panel dataset combining listed-firms information and the implementation of the HMP tool at city-level in China from 2010 to 2019, we provide empirical evidence to demonstrate that the tightened HMP has a significantly positive spillover effect on firm innovation. Our results are robust to various measurements of firm R&D activity and housing macroprudential policy. We also addressed the endogeneity concerns by employing the Heckman method, 2SLS-IV regression, and dynamic panels. Taken together, our benchmark results are solid and robust. Mechanism analysis indicates that the promotion effect of HMP on firm innovation may be driven by two main factors: lower firm leverage and increased cash holding.

And we provide further evidence highlighting the heterogenous effect of HMP at the city level, mainly focusing on the degree of housing dependency and financial development. We find that firms in cities with lower housing dependency and less financial development would react more positively to tightened HMP. These findings provide evidence that the local government may weigh between economic growth and financial stability when implementing HMPs.

Our research may shed light on literature related to housing market regulation, macroprudential policy, and firm investments. One possible avenue for further research would be to investigate the asymmetric effect of HMP on firms’ performance. Another potential direction is to extend our study to discuss the interaction between macroprudential policy and fiscal policy or monetary policy, which play a key role in influencing the housing market as well.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

There is a bubble crash during 2014–2015 in China, where the capital markets experience a shrink.

Due to space limits, related data is given in appendix.

LTV ratio = mortgage loan amount/ appraised property value. A higher value of LTV suggests a more relaxing regulation environment.

We choose these 54 cities for following several reasons: On the one hand, HMP information is not completely public, while these 54 cities have relatively better information disclosure about HMP during our sample period. On the other hand, these 54 cities are all big and medium cities in China with almost 50% of China total GDP in 2019 and 1947 listed firms, which enables us to explore the relation between HMP and firm innovation.

We focus on the consumer-facing LTV and DTI instruments, as well as the financial institution-facing LTV instruments to provide a more comprehensive picture of the dynamics of HMP in China.

There is no situation that local government adopt different direction HMP in a year during our sample period.

Detailed description of control variables are given in appendix A.

We show correlation matrix results as well in appendix B.

The aggregated obs in this heterogenous analysis are less than whole sample since the numbers of firms in some industries are inadequate to satisfy the panel regression requirements.

Heckman regression is mainly used for addressing the concerns on sample selection.

The Sargan test results and instrument identification both show that the RLA is suitable for HMP.

It is calculated by 100%-averaged LTV ratio for households (HMP_HL), higher value suggests tightened HMP.

We give the two-sample test results in appendix C, which show that the firms in higher housing dependency and better financial development regions have higher R&D investment level.

The kernel results in Fig. 3 support this by showing that HMP in high housing dependency are more likely to be a normal distribution with zero mean value.

References

Akinci O, Olmstead-Rumsey J (2018) How effective are macroprudential policies? An empirical investigation. J Financ Intermediation 33:33–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2017.04.001

Alesina A, Zhuravskaya E (2011) Segregation and the quality of government in a cross section of countries. Am Econ Rev 101:1872–1911. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.5.1872

Allen J, Grieder T, Peterson B, Roberts T (2020) The impact of macroprudential housing finance tools in canada. J Financ Intermediation 42:100761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2017.08.004

Alpanda S, Zubairy S (2017) Addressing household indebtedness: monetary, fiscal or macroprudential policy. Eur Econ Rev 92:47–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.11.004

Ayyagari M, Beck T, Peria MSM (2018) The micro impact of macroprudential policies: firm-level evidence. IMF Work. Pap. 2018. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781484385654.001.A001

Ayyagari M, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Maksimovic V (2011) Firm innovation in emerging markets: the role of finance, governance, and competition. J Financ Quant Anal 46:1545–1580. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109011000378

Badarau C, Carias M, Figuet J-M (2020) Cross-border spillovers of macroprudential policy in the Euro area. Q Rev Econ Financ 77:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2020.01.005

Balsmeier B, Fleming L, Manso G (2017) Independent boards and innovation. J Financ Econ 123:536–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2016.12.005

Becker B (2015) Public R&d policies and private R&d investment: a survey of the empirical evidence. J Econ Surv 29:917–942. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12074

Cerutti E, Claessens S, Laeven L (2017) The use and effectiveness of macroprudential policies: new evidence. J Financ Stab 28:203–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2015.10.004

Chaney T, Sraer D, Thesmar D (2012) The collateral channel: how real estate shocks affect corporate investment. Am Econ Rev 102:2381–2409. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.102.6.2381

Chari A, Dilts-Stedman K, Forbes K (2022) Spillovers at the extremes: the macroprudential stance and vulnerability to the global financial cycle. J Int Econ 136:103582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2022.103582

Chen H, Yoon SS (2021) Does technology innovation in finance alleviate financing constraints and reduce debt-financing costs? Evidence from China. Asia Pac Bus Rev 0:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2021.1874665

Chen K, Wen Y (2017) The great housing boom of China. Am Econ J Macroecon 9:73–114. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20140234

Demir F (2009) Financial liberalization, private investment and portfolio choice: Financialization of real sectors in emerging markets. J Dev Econ 88:314–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.04.002

Demir F, Hu C, Liu J, Shen H (2022) Local corruption, total factor productivity and firm heterogeneity: empirical evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. World Dev 151:105770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105770

Dicks D, Fulghieri P (2021) Uncertainty, investor sentiment, and innovation. Rev Financ Stud 34:1236–1279. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhaa065

Ding N, Gu L, Peng Y (2022) Fintech, financial constraints and innovation: evidence from China. J Corp Financ 73:102194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2022.102194

Gebauer S, Mazelis F (2019) Macroprudential regulation and leakage to the shadow banking sector. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3433641

He D, Nier EW, Kang H (2016) Macroprudential measures for addressing housing sector risks. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2844274 [accessed Oct 19, 2022]

Hoesli M, Milcheva S, Moss A (2020) Is financial regulation good or bad for real estate companies?–an event study. J Real Estate Finance Econ 61:369–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-017-9634-z

Hsu P-H, Tian X, Xu Y (2014) Financial development and innovation: cross-country evidence. J Financ Econ 112:116–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.12.002

Jiménez G, Ongena S, Peydró J-L, Saurina J (2017) Macroprudential policy, countercyclical bank capital buffers, and credit supply: evidence from the Spanish dynamic provisioning experiments. J Polit Econ 125:2126–2177. https://doi.org/10.1086/694289

Kang Q, Wu J, Chen M, Jeon BN (2021) Do macroprudential policies affect the bank financing of firms in China? Evidence from a quantile regression approach. J Int Money Financ 115:102391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2021.102391

Liang Y, Shi K, Wang L, Xu J (2017) Local government debt and firm leverage: evidence from China. Asian Econ Policy Rev 12:210–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12176

Mao Y (2021) Managing innovation: the role of collateral. J Account Econ 72:101419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2021.101419

Merton RC (1995) Financial innovation and the management and regulation of financial institutions. J Bank Financ 19:461–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4266(94)00133-N

Miao J, Wang P (2014) Sectoral bubbles, misallocation, and endogenous growth. J Math Econ 53:153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmateco.2013.12.003

Moosa IA (2017) The regulation of shadow banking. J Bank Regul 18:61–79. https://doi.org/10.1057/jbr.2015.8

Nemlioglu I, Mallick S (2021) Effective innovation via better management of firms: the role of leverage in times of crisis. Res Policy 50:104259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2021.104259

Ouyang AY, Wang J (2022) Shadow banking, macroprudential policy, and bank stability: Evidence from China’s wealth management product market. J Asian Econ 78:101424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2021.101424

Qi Y, Qin H, Liu P, Liu J, Raslanas S, Banaitienė N (2022) Macroprudential policy, house price fluctuation and household consumption. Technol Econ Dev Econ 28:804–830. https://doi.org/10.3846/tede.2022.16787

Rong Z, Wang W, Gong Q (2016) Housing price appreciation, investment opportunity, and firm innovation: evidence from China. J Hous Econ 33:34–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2016.04.002

Solow RM (1957) Technical change and the aggregate production function. Rev Econ Stat 39:312–320. https://doi.org/10.2307/1926047

Wei L, Lin B, Zheng Z, Wu W, Zhou Y (2023) Does fiscal expenditure promote green technological innovation in China? Evidence from Chinese cities. Environ Impact Assess Rev 98:106945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2022.106945

Yang J, Suh H (2021) Heterogeneous effects of macroprudential policies on firm leverage and value. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3837044

Yang JY, Suh H (2023) Heterogeneous effects of macroprudential policies on firm leverage and value. Int Rev Financ Anal 86:102554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2023.102554

Zhang L, Tao Y, Nie C (2022) Does broadband infrastructure boost firm productivity? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Financ Res Lett 48:102886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.102886

Zhang T, Zou H (1998) Fiscal decentralization, public spending, and economic growth in China. J Public Econ 67:221–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(97)00057-1

Zhao X, Lynch Jr JG, Chen Q (2010) Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: myths and truths about mediation analysis. J Consum Res 37:197–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/651257

Zhu C, Zhao D, Qiu Z (2019) Internal and external effect of estate investment upon regional innovation in China. Emerg Mark Financ Trade 55:513–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2018.1530981

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 19CGL003). Thanks for Zhubin Xie’s work in collecting policy data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. Data are coming from government disclosure and firm reports.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, M., Zhu, H., Sun, Y. et al. The impact of housing macroprudential policy on firm innovation: empirical evidence from China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 498 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02010-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02010-4