Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with the “infodemic” of misinformation, meant First Nations peoples in Australia’s Northern Territory were hearing “the wrong story” about COVID-19 vaccines. In March 2021, when the Australian government offered COVID-19 vaccines to First Nations adults there was no vaccine information designed with, or for, the priority group. To address this gap, we conducted a Participatory Action Research project in which First Nations leaders collaborated with White clinicians, communication researchers and practitioners to co-design 16 COVID-19 vaccine videos presented by First Nations leaders who spoke 9 languages. Our approach was guided by Critical Race Theory and decolonising processes including Freirean pedagogy. Data included interviews and social media analytics. Videos, mainly distributed by Facebook, were valued by the target audience because trusted leaders delivered information in a culturally safe manner and the message did not attempt to enforce vaccination but instead provided information to sovereign individuals to make an informed choice. The co-design production process was found to be as important as the video outputs. The co-design allowed for knowledge exchange which led to video presenters becoming vaccine champions and clinicians developing a deeper understanding of vaccine hesitancy. Social media data revealed that: sponsored Facebook posts have the largest reach; videos shared on a government branded YouTube page had very low impact; the popularity of videos was not in proportion to the number of language speakers and there is value in reposting content on Facebook. Effective communication during a health crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic requires more than a direct translation of a script written by health professionals; it involves relationships of reciprocity and a decolonised approach to resource production which centres First Nations priorities and values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the COVID-19 virus spread globally an equally worrying contagion spread: the “infodemic”, which was as “dangerous to human health and security as the pandemic itself”. (United Nations Secretary General, 2020) The “infodemic” referred to COVID-19 information over-load and misinformation spread through social media which promoted “scapegoating and scare-mongering” and hampered public health efforts. (United Nations Secretary General, 2020) In Australia’s Northern Territory (NT), where First Nations peoples constitute 30% of the population, the global “infodemic” was compounded by inconsistent Australian government vaccine messaging and a fear of health services “due to racism”. (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022b; Rogers & Powe, 2022; Li et al., 2022; Stanley et al., 2021; Tsirtsakis, 2021) Additionally, in the NT where 60% of First Nations peoples speak one or more of the approximately 100 languages, it was evident that First Nations language speakers were “far less willing to take a vaccine” than others. (Biddle et al., 2021 p.11; Northern Territory Government, 2022).

Against this backdrop, the Australian government began the vaccine roll out in March 2021 targeting priority groups including First Nations adults. This was due to the potential devastating impact of COVID-19 spreading into communities which was recognised because First Nations peoples experience disproportionate rates of poor health resulting from generations of racist policies and practices. (Connolly et al., 2021; Crooks et al., 2020; McCaffery et al., 2020; Stanley et al., 2021) However, when the vaccine roll out began not one First Nations person in the NT had been diagnosed with COVID-19. (Northern Territory Department of Health, 2021) While most of Australia was suffering through lock downs and COVID-19 related deaths, the NT was described as “the safest place in Australia” (Kerrigan et al., 2020) and First Nations peoples questioned the need for the vaccine. A co-designed information campaign was required to subvert “infodemic” related fears amongst First Nations peoples in the NT. (Biddle et al., 2021).

Study rationale

When this study was designed there were no locally relevant information campaigns for the NT which provided First Nations peoples with reliable information. Additionally, the underfunded and overstretched NT health services (Zhao et al., 2022) did not have capacity to create a public health campaign. Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHO) also lacked capacity to create local campaigns as staff focused on the complex logistics of vaccine distribution to remote NT communities.

This project brought together First Nations leaders and White clinicians and communication researcher-practitioners to co-design, distribute via social media and evaluate locally relevant COVID-19 vaccine videos. The co-design approach to video production was vital because historically Australian government health campaigns, designed to suit White communication norms, have inspired resistance among First Nations peoples. (Bond et al., 2012; Crooks et al., 2020; Kerrigan et al., 2020; Seale et al., 2022) The rationale for distributing videos via social media was twofold. Social media has been used to build and express self-determination narratives (Carlson, 2013; Frazer et al., 2022) and social media was successfully used by ACCHOs to promote social distancing and other precautionary measures during the early stages of the pandemic. (Behrendt, 2021) Finally, it was imperative that the evaluation measure the impact of videos through a First Nations lens. (Barker et al., 2022) First Nations researchers explained videos would be deemed successful if family and friends received information that supported informed decision making. The goal of the project was not to increase vaccine uptake which is often used by Western biomedical researchers as a measure of success. (Kerrigan et al., 2023) The decision to be vaccinated must remain with sovereign individuals and families and this, in part, was connected to the fact that historically vaccines had been tested on First Nations peoples. (Mayes, 2020; Mosby & Swidrovich, 2021).

The aim of the paper is to unpack the processes employed to create COVID-19 vaccine videos for First Nations communities and to present the evaluation of the videos. Our work may be relevant to health and communication professionals who are working to decolonise health communication.

Methods

Terminology

First Nations peoples are identified in relation to their Nation, affiliated country and/or language group. Non-Indigenous researchers capitalise the word White to associate themselves with the socially constructed racial category defined in Whiteness studies. (Bargallie, 2020) The word White is used to remind non-Indigenous researchers to critically reflect on unearned privilege and power with the aim of decolonising thought and practice. (Kowal, 2008).

Researcher backgrounds

Lead author VK is a White intercultural health communication researcher and practitioner. DP is a researcher, allied health professional and Aboriginal woman whose family originates from Central Australia (Eastern Arrernte). CR is an Arrernte/Kaytete woman, a project officer, community engagement specialist and family mediator. RMH is a Gälpu women from the Yolŋu nation. She works across health, environment and research sectors. PMW is an Aboriginal Health Practitioner (AHP) and Ngan’gikurunggurr speaker from the West Daly region of the NT. He lives in the Nauiyu community on Malak Malak land. WT is a White multimedia producer who has 20+ years’ experience facilitating video making workshops with First Nations communities. CG is a Djinang-Wulaki man, Burarra speaker and Elder from Maningrida. CG became an AHP in 1976 and is chair of the Mala’la Health Board. JB is a Kunwinjku speaking Djalama women who works as a language worker at Bininj Kunwok Regional Language Centre (BKRLC) and sometimes at the NT Aboriginal Interpreter Service. JN is a Kunwinjku speaking Bularldja Elder who is the chairperson at BKRLC. AR and JD are White global health researchers and infectious disease clinicians.

Study design

This Participatory Action Research (PAR) (Baum et al., 2006) project, which drew on elements of constructivist grounded theory (CGT), (Charmaz, 2014; Simmons and Gregory, 2003) was guided by decolonising philosophies including Critical Race Theory (CRT) and Freirean pedagogy.(Delgado et al., 2017; Freire, 1970; Smith, 2012) These two philosophies are linked by a critical focus on the hegemony, foregrounding race and racism, and a commitment to participatory approaches and prioritising marginalised voices and worldviews. When applied, our methodologically robust approach works to subvert the dominance of Whiteness. The study can be divided into two phases. Phase 1 refers to the co-design of videos and phase 2 refers to the evaluation of videos.

Participant sampling

First Nations leaders and Elders were invited through personal and professional networks to collaborate with White infectious disease specialists, communication researchers and video producers. All First Nations participants were 18 years+, spoke a First Nations language and/or English and lived in NT remote, regional and city centres. In phase 1, First Nations participants with a vested interest in the issue were purposefully sampled. (Baum et al., 2006; Hall, 1985) The sample included clinical professionals, health promotion workers, interpreters, artists, language centre workers, members of an Infectious Disease Indigenous Reference Group (Davies et al., 2022) and First Nations trainees aged between 19 and 26 years from the Menzies School of Health Research. In phase 2, theoretical sampling was incorporated to ensure data explored the diverse perspectives required for a comprehensive evaluation. (Charmaz, 2014) The sample included some of the same collaborators from phase 1 who became video presenters and also co-authors on this publication. During phase 2, researchers expanded the sample to include Royal Darwin Hospital (RDH) inpatients and Aboriginal Health Practitioners (AHP’s) who independently evaluated the videos. Inpatients were invited to participate by DP who approached individuals on the RDH campus. AHP’s were invited through professional networks.

Reciprocity in research practice

Video presenters who were not employed by stakeholders were paid according to their preferences. RDH inpatients and AHPs were thanked for sharing their knowledge with a voucher for a local café or supermarket. Pseudonyms were assigned to inpatients and AHPs. As per PAR, the video presenters who were participant-researchers and therefore are co-authors use their real names to ensure ideas are accurately attributed.

Data collection

Data included structured and semi-structured interviews, researcher field notes and social media analytics.

In phase 1, CR completed structured interviews (Fontana & Prokos, 2016) with the Infectious Disease Indigenous Reference Group. Interviews produced handwritten notes. Additionally, CR and VK scrolled through personal Facebook and LinkedIn feeds and took screenshots of pro and anti-vaccine conversations. CR, VK, AR and JD documented yarns with First Nations leaders and Menzies trainees as field notes. (Bessarab & Ng’andu, 2010) VK and WT also kept field notes reflecting on the video production process. (Schön, 1987) In phase 2, semi structured interviews with video presenters were conducted by VK to explore the production process and perceived impact of videos. In search of divergent views, DP conducted semi structured interviews with RDH inpatients and AHPs after they watched the video/s relevant to them. Recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim.

In phase 2, social media analytics were collected alongside qualitative data. Analytics were collected over 3-months from the date each video was published. Data came from Menzies School of Health Research’s Facebook, Vimeo, Twitter and LinkedIn accounts; the NT Department of Health’s Facebook (organic and sponsored), the parliamentary Member for Lingiari Facebook (sponsored), Miwatj Health Facebook and Indigenous.gov.au YouTube. We reported reach, impressions, views and engagement. (Newberry, 2022) Reach refers to the number of people the video reached, organically or via sponsorship. Impressions refers to the number of times people saw the video in their feed which can be higher than reach because the video may have made an “impression” on someone’s feed more than once. Views refer to how many people played the video: Facebook defines view as 3 seconds or more, whereas YouTube defines view as 30 seconds or more. Engagement indicates whether a user interacted with the post.

Data analysis

Data was inductively analysed and guided by Indigenous knowledges and decolonising theories. (Delgado et al., 2017; Freire, 1970; Smith, 2012) In phase 1, CR analysed data from structured interviews to identify common concerns across language groups. Afterwards, CR, VK, AR and JD discussed the identified concerns which were synthesised into five questions to be addressed in the videos. (Charmaz, 2014) Clinicians AR and JD provided evidence-based clinical information to answer the questions. Information was then rewritten by VK, CR, WT, RMH and JD into plain English ensuring the information followed the Therapeutic Goods Administrations (TGA) guidelines on advertising vaccines. (Therapeutic Goods Administration, 2019).

In phase 2, DP read and re-read interview transcripts to identify similarities, differences and patterns in the data. This resulted in analytical memos. (Charmaz 2014) VK used NVivo12 to review the transcripts while listening to the recorded interviews to minimise dematerialising voices to words disconnected from lived experience. (Gallagher, 2020) This produced memos and codes. The combined preliminary analysis led to categories that captured shared and divergent experiences. Researchers DP and VK conducted “sense checks” of the data to ensure the narrative was a true reflection of the participants and not the perspective of the researchers. (Barkham and Ersser, 2017) Social media analytics was tabulated by AR and summarised using simple descriptive statistics. A draft manuscript was presented to all co-authors who provided feedback which was incorporated into the final manuscript.

Ethics

The Ethics Committee of the NT Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research (HREC 2017–3007) approved this research.

Results

A total of 35 interviews were conducted between 3rd March 2021 and the 28th October 2021. During the co-design phase 15 interviews were conducted with leaders who spoke Anindilyakwa, Arrernte, Burarra, English, Kunwinjku, Kriol, Murrinh-Patha, Ngan’gikurunggurr, Pitjantjatjara, Tiwi, Warramunga, Warlpiri and Yolŋu Matha. Perspectives from different language groups ensured representation from diverse communities.

To evaluate the videos we conducted 20 interviews and reviewed social media analytics. Five video presenters, who are also co-authors, shared insights into the production process and perceived impact of the videos: Burarra speaker Charlie, Ngan’gikurunggurr/Kriol speaker Phillip, Yolŋu Matha speaker Rarrtjiwuy and Kunwinjku speakers Jill and Jeanette. 15 interviews were conducted with 10 RDH inpatients and five AHP’s. Inpatients spoke Burarra, English, Murrinh-Patha, Ngan’gikurunggurr, Tiwi and Yolŋu Matha. AHPs spoke Anindilyakwa, English and Yolŋu Matha.

We found that First Nations peoples in the NT had the “wrong story” about COVID-19 vaccines. To address this, we co-designed 16 locally relevant videos in 8 First Nations languages plus English. The videos were perceived to be meaningful because video presenters were trusted by the target audience, Elders were involved, First Nations languages were spoken, and there were opportunities to decolonise the production process. Social media data revealed that sponsored Facebook posts outperformed organic sharing by a significant margin, reaching a much larger audience at an incredibly low cost of just 1.1 cents per person and that despite the rising popularity of YouTube among the target audience, videos shared on a government branded YouTube page had very low impact.

To ensure the results are clear, participants will be given a descriptor alongside their name and language to identify their role in the research as a leader, video presenter, Aboriginal Health Practitioner or RDH inpatient.

Vaccine related confusion and fear: “the wrong story”

First Nations leaders said vaccine hesitancy was prevalent in their communities. Many questioned the need to be vaccinated because COVID-19 was not in the NT and asked if the vaccine was being tested on First Nations peoples. Kunwinjku speaker and video presenter Jill said people were getting “the wrong story” such as “if we get that vaccine we might get the number of the beast”. Ngan’gikurunggurr/Kriol speaker and video presenter Phillip said that people worried the vaccine would inject “some micro tick or some metal into their blood” or “the COVID infection or virus into their body so that they die.” Anindilyakwa speaker and leader Paul explained that in his community there was a large uptake of the influenza vaccine but people were worried the COVID-19 vaccine had been developed too quickly. Paul said many considered COVID-19 to be a “White people illness”. Arrernte speaker Sarah summarised the confusion:

Some of our mob don’t want to get the needles. We are thinking Aboriginal people don’t get it (the virus). (But) if we do get it, it’ll be really bad – it will kill us! Our mob are frightened – our mob watch the news. – Sarah, Arrernte speaker, leader

Due to a lack of trustworthy information, people relied on the news and social media. Ngan’gikurunggurr/Kriol speaker and AHP Phillip said he wanted to counter the misinformation on Facebook with “positive messages about the COVID immunisation”.

How can we step over that stigma on social media.?…and then my thoughts were like ‘Oh, you know, we should start doing things with language, local people’. – Phillip, Ngan’gikurunggurr/Kriol speaker, video presenter

Leaders reflected that mainstream health services commonly produce written pamphlets as a means of sharing information however as Warramunga/Warlpiri speaker Patricia said: “our mob are visual”. Ideally information would be delivered face to face however leaders also recognised there were limited people to deliver messages across large geographical areas therefore videos that could be shared quickly across large distances was valuable.

Answer the communities’ questions: “Is the vaccine safe?”

To counter the “wrong story”, First Nations leaders, White clinicians and communication researcher-practitioners worked together to extract pertinent questions from the stories relating to confusion and fear. Five key questions were formulated:

1. Why should I get the vaccine? 2. What is the vaccine? 3. Is the vaccine safe? 4. What will happen when I get the vaccine? 5. What are the side effects?

While the questions had universal relevance the responses developed were tailored to address First Nations perspectives. (see Table 1) Considering the large burden of chronic disease in First Nations communities many leaders including Ngan’gikurunggurr/Kriol speaker and video presenter Phillip said information should also specifically address concerns from people with “chronic diseases, people with renal failure, liver problems and heart problems”.

To ensure information provided was consistent across diverse communities, a two-page briefing document in plain English was produced in a Q and A format. The briefing document was shared with video presenters with an open invitation to contact clinicians if there were unaddressed concerns. Presenters and clinicians both benefitted from subsequent conversations which were often lengthy and occurred more than once. These conversations meant presenters knowledge of the COVID-19 vaccine grew and clinicians gained a deeper understanding of what was happening in communities. Yolŋu Matha speaker and video presenter Rarrtjiwuy explained the conversations with clinicians, which she described as “authentic” and “informative”, helped her feel more confident in sharing the vaccine information. She explained that she wanted the video to provide information to help family “make an informed decision”. All presenters were adamant the message should not feel forceful and reported that campaigns simply telling people to “get the jab” were sometimes ignored because people felt the message was coercive.

We are not forcing people, we just want to tell the stories. That’s all. Giving out the information from this COVID vaccine so people can understand. – Jeanette, Kunwinjku speaker, video presenter

In deciding what questions to address in the videos, a decision was made not to debunk conspiracy theories or misinformation from religious leaders. The rationale was that the videos should remain relevant for between 4 and 6 months to compliment the NT vaccine roll out. During the pandemic, “fake news” was emerging daily so attempts to address each idea would have resulted in outdated videos in a short span of time. However, this decision meant that AHPs Natalie, Deborah and Ashley questioned how the videos were co-designed:

Has anyone been out to the communities to ask them what their real concerns were? Um, because some of the ones that I’ve got is they don’t have any concerns because of their strong belief in religion which is going to protect them. – Deborah, English speaker, AHP

Additionally, during the vaccine rollout, the risk of blood clots associated with the AstraZeneca vaccine became apparent. Again, AHPs questioned why this time-specific issue was not addressed. Researcher field notes reveal the team discussed adding detailed information to address the risk of blood clots but decided to only briefly address the issue as per Table 1. This decision was made for two reasons: firstly, blood clots were only associated with one of two vaccines available at the time, the AstraZeneca vaccine, and TGA guidelines banned the use of vaccine brand names in information resources. Secondly, due to distribution issues most people in the NT were offered the Pfizer vaccine which was not linked to blood clot risks.

Locally relevant vaccine resources: “make the messages meaningful”

Between 24 March 2021 and the 9 May 2021, 15 COVID-19 vaccine videos in eight languages were published in just over 6 weeks. Production delays meant a 16th video in Arrernte was published on 31 August 2021. The video presenters were employed variously as health professionals, in health promotion, at language centres as interpreters and storytellers, in the media, at universities, and some were also Elders. In response to the needs of people with chronic illnesses, a long-term renal patient Ms C recorded a video. The video shared information in the briefing document and addressed additional issues, identified by Ms C, who incorporated her own experiences of living with a chronic illness to information about the vaccine. Ms C has passed away and the video was deleted in accordance with cultural protocols.

RDH inpatients recognised the purpose of the video was to provide baseline vaccine information and to encourage people with concerns to visit the clinic. Tiwi speaker and inpatient David said family and friends need to watch the videos so they can learn about the vaccine which will keep them safe from this “deadly virus”. English speaking renal patient Katherine watched two English videos and appreciated the message was “short and sweet and to the point.” She also revealed she was unvaccinated because “I’m not very well at the moment so I’m just going step by step” but added after watching the video with Ms C she felt more receptive towards the vaccine. However, English-speaking health professional Joanna said the videos were too simplistic. Joanna said the English videos “won’t work with my family…it’s a bit too, not simple, I think it’s really good but they probably want to ask deeper questions”. Video presenter Rarrtjiwuy said that while the process and video outputs may not suit every community, she explained there are lessons to be learned from the process undertaken:

It’s not just thinking about education and information sharing as a tick box but actually taking time and effort to make the messages meaningful….and what we should take to government is that ‘one size approach’ isn’t going to work…..It’s not just about developing videos that are going to be helpful for community, it’s also about the right people and the right attitude. – Rarrtjiwuy, Yolŋu Matha speaker, video presenter

We identified four key components that were pivotal to co-designing meaningful messages.

Firstly, the videos were meaningful because video presenters were recognisable through biological and kinship relationships, professional networks and presenters were known to have strong health and cultural values. These relationships meant that the presenters were trusted and could be held accountable in their communities. Tiwi speaking RDH inpatient David commented on the Tiwi video presenter who was an Elder:

I think he’s a respected man and cultured man and he understands about love and caring and sharing stories to the whole community and make sure everyone’s safe in community….speaking in Tiwi, it’s very nice and good.– David, Tiwi speaker, RDH inpatient

English-speaking AHP Natalie said if viewers don’t like the video presenter “you’re not going to get buy-in with the community”. This was observed by a research team member who was working on the vaccine roll out in a remote community. Field notes documented that one of the videos was shown at an arts centre and afterwards six people went to the clinic to get vaccinated, but the same video with the same leader was shown to another artist who said: “I hate that man, he’s done nothing for me, I’m not getting vaccinated”.

Yolŋu Matha speaker and video presenter Rarrtjiwuy said a strength of the videos was that they were personalised unlike the “generic” government messages: “I think it needs to be personalised….they’re making a connection to a real person rather than a cartoon”. AHPs commented that creating videos with real people, not animations, allowed hearing-impaired viewers to lip read.

To further localise the videos, overlay images included video presenters being vaccinated and landscapes associated with each language group. RDH inpatient Katherine said that seeing images of presenters being vaccinated demonstrated the vaccine was “safe to get” and inpatient David said images featuring local landscapes relevant to language groups gave people “a clue” that the video was relevant to them.

For many of the leaders the decision to appear in the videos was complex. Leaders who agreed to work on the videos explained they did so because they were worried family would die if COVID-19 took hold in their community. Burarra speaker and video presenter Charlie said if COVID-19 spread through his unvaccinated community of Maningrida “Family will pass away, then the next family, then next family….”. Some leaders, who were involved in identifying reasons behind vaccine hesitancy, declined to appear in videos because COVID vaccination was considered controversial. Similarly, First Nations leaders at Menzies School of Health Research advised trainees against recording vaccine information fearing the young people may experience a backlash. Kunwinjku speaker and video presenter Jill explained the responsibility: “you have to be strong…to give true messages to people”. Jill, an Elder, worried some people might not listen to her: “Maybe they’re thinking….‘Oh, this woman didn’t work at the clinic’ or ‘She’s not working at the clinic, why does she come, telling us this and that?’. However, Jill and Jeanette decided to record information because at the time of the vaccine roll out there were no health workers at the local clinic who spoke Kunwinjku and they wanted to ensure their families had been provided with evidence-based information, in their own language, so they could make an informed choice.

Secondly, the co-design process included Elders. Presenters used the briefing document to supply information to Elders, educators and linguists who translated information. Before recording their videos, Jeanette and others from the Bininj Kunwok Regional Language Centre reviewed their English to Kunwinjku translation with Elders “two or three times” to ensure they were sharing the “true message” before recording. Phillip described translating the document and testing the validity of his message on Elders:

And then I read to them what I wrote up and whatever I said in language without showing them what the script was…..And I wrote it in my language. And then they said, ‘Yeah, no, that’s good’ but then they changed some words for me. – Phillip, Ngan’gikurunggurr/Kriol speaker, video presenter

Rarrtjiwuy said “we make decisions that are agreed as a group, not as an individual person.” She explained the value of working with her grandmother, Rosemary Gundjarrangbuy:

To have a Yolŋu Elder in the room bouncing off ideas…talking about the respectful way to ask and answer those questions….that was awesome. – Rarrtjiwuy, Yolŋu Matha speaker, video presenter

Before distribution videos were reviewed by the video presenters, Elders and clinicians. Messages recorded in First Nations languages were reviewed by independent language speakers who translated the message back into English. The back translation was then reviewed by clinicians to ensure the information was clinically correct.

Thirdly, messages were meaningful because respectful verbal and body language was used. Kunwinjku speaker Jeanette said translated messages meant “people can hear the straight message”. Sharing information in languages made it easier for the audience because the medical concepts had already been considered and interpreted. This removed the burden placed onto the audience when information is in English:

Those videos have provided stories and messages in a way that people can articulate and comprehend easily because it’s in Yolŋu Matha. So, they don’t have to think about and make an assumption ‘Oh, does this word mean this?’. You know, everything’s done in the practice of having a normal conversation which is what we really wanted. – Rarrtjiwuy, Yolŋu Matha speaker, video presenter

Some video presenters spoke multiple languages and chose which language was most appropriate to use. Burarra speaker and video presenter Charlie explained that in his community nine languages are spoken: “I’m going to go talk to this mob from my language group here and then I pass it on to another bloke and then he spoke to his language, you know, his tribe”.

The videos also contributed to language revitalisation. Phillip spoke Kriol, Ngan’gikurunggurr and English but chose to record the message in Ngan’gikurunggurr to keep the “language going”. RDH inpatient and Ngan’gikurunggurr speaker Melissa said she felt “happy” and “proud” to see her uncle Phillip share information in her language. Phillip shared that his Aunty, one of a few remaining fluent speakers, was overwhelmed with pride which resulted “in tears” when he said he wanted to record vaccine information in Ngan’gikurunggurr:

She was emotional but like happy…She was thinking ‘I’m glad this language is not dying’. And we’re not only putting the COVID message out but it’s an educational tool too for keeping the language going. – Phillip, Ngan’gikurunggurr/Kriol speaker, video presenter

Beyond words, video presenters also displayed the same communication norms as viewers. Yolŋu AHP Emma explained that effective communication includes relationships, tone of voice and body language:

Sometimes you have to…talk to them safe way. Not talk to make them scared because sometimes that client or Yolŋu person can feel scared when the balanda (White) person like nurses can talk to make them, scared in their own voice. But in Yolŋu you talk in language so they feel comfortable, so they can know you and they are related to you. Yo (yes). And you can just talk to them in language but slowly. They don’t feel any fear. – Emma, Yolŋu Matha, AHP

As an AHP with access to reliable information, Emma said she didn’t learn anything new from the Yolŋu Matha videos but hearing the information in her first language was helpful because it confirmed what she had learnt in English. English-speaking AHP Deborah said that she had observed language speakers watch a video in English and then the same video in their own language to “make certain that this story is being told same”.

AHP’s Natalie, Deborah and Ashley said they were disappointed there was no video in Kriol, one of the largest language groups. They were also critical of the English videos which they thought were overly scripted. AHP Deborah said plain English was required: “everyday man’s language. Not the big medical jargon.” Deborah also said that presenters needed to speak “from the heart” and “improvise a little bit. Put a little bit of your soul into what you are talking about.” The group of AHPs also said clinician Dr Jane Davies, the only White person to feature in the videos, was appropriate because she was known to AHP’s and patients through her work in communities. English-speaking AHP Natalie said, “Dr Jane, she’s deadly! She explains things thoroughly and simply.”

Finally, the format of how information was presented in the video was decolonised by some of the video presenters. Seven presenters delivered the message as an individual direct to camera which is in line with White communication norms. However, three groups chose a different approach. Three groups recorded a Q and A with clinician Dr Jane. Media personality Charlie King explained because he was not a COVID-19 vaccine expert he was more comfortable asking questions of the expert and supporting their message. The Kunwinjku and Yolŋu Matha leaders also chose the Q and A with clinician Dr Jane answering questions (refer to Table 2). The videos featured an Elder and an emerging leader who together asked questions of the clinician. The Kunwinjku recording was done in English and after BKRLC workers recorded the voice over translation which was overlayed. The Yolŋu Matha video was recorded in Yolŋu Matha and English in real time. Yolŋu Matha speaker and video presenter Rarrtjiwuy asked questions of the clinician in English and then Rarrtjiwuy and her grandmother Rosemary discussed the answer in Yolŋu Matha. Rarrtjiwuy said the complicated topic required numerous perspectives: “COVID is new, COVID is the unknown, COVID is something that we’re all discovering together and that you know, requires multiple lenses.” This decolonised approach to presenting information also meant that instead of the messages being short and direct as seen in mainstream health campaigns, these videos were lengthy. The Q and A format resulted in three videos in Kunwinjku and five in Yolŋu Matha and the average duration of each video was 5 min.

After watching a selection of videos, RDH inpatients did not express a preference for the Q and A format, or the message delivered direct to camera. English speaking AHPs including Deborah said she preferred the Q and A in English with leader and media personality Charlie King and clinician Dr Jane because it wasn’t “just a blurb. Some of the questions that were asked were actually, ‘Yes! That’s my concern.’ And they’re getting an answer.”

The videos were a “stepping stone”

Presenters became trusted sources of information after co-designing and recording the videos. Phillip described the video as a “stepping stone” to face to face conversations. Vaccine knowledge gained from the co-design process was shared with family and resulted in confidence in the vaccine. Philip said the Elders and linguists he consulted “were the first ones at the clinic the first day that it was going to be delivered…after them there was heaps of people….all lined up for their first jab. No questions about it.” Kunwinjku speaker Jeanette said that before the videos were published she shared her new knowledge with family who then got vaccinated: “My elder sister she got it, my sister-in-law and two girls, my nieces.”

Rarrtjiwuy reported that Yolŋu recognised her from the videos and asked her to explain the vaccine at the shops, over the phone or during ceremonies: “when it’s the right space and time to provide education”. Rarrtjiwuy also said the videos did not generate negative feedback across her communities:

I’m a frequent flyer across north-east Arnhem land, I’ve not had one Yolŋu person come to me and say ‘the videos you did were shit’ or they, you know, ‘they’re forcing people’…I have not have any negative feedback.- Rarrtjiwuy, Yolŋu Matha speaker, video presenter

Video distribution supported through partnerships

Videos were distributed via ACCHO’s, Aboriginal Hostels Limited, Bininj Kunwok Regional Language Centre, Children’s Ground, the federal Indigenous Policy and Engagement advisory group for the COVID-19 response, Menzies School of Health Research, Miwatj Aboriginal Health Corporation (Miwatj Health), NT Health, NT Primary Health Care Network, Thamarrurr Aboriginal Corporation, a NT politician and video presenters. Stakeholders shared videos on social media, websites and TVs in clinics, hospital waiting rooms and shops. The videos were also uploaded to NT Health electronic tablets which meant frontline staff could show videos during the vaccine roll out. Miwatj Health proactively distributed videos. All five Yolŋu Matha videos were on rotation on TVs at seven Miwatj clinics. Additionally, all videos were posted on Facebook twice (approximately one month apart) and shared from the Miwatj Facebook page to six Yolŋu targeted community notice boards with over 16 thousand followers combined. Two stakeholders sponsored Facebook posts. Local politician, Warren Snowden, sponsored 15 videos for one month per video (excluding the Arrernte video due to production delays) at a cost of $4510 on their Facebook page. These sponsored posts geo targeted language speakers. NT Health spent $3852.24 to sponsor one Kunwinjku, Yolŋu Matha, Ngan’gikurunggurr, Murrinh-Patha and two English videos for between 7 and 14 days.

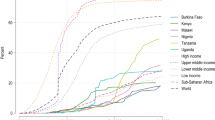

The sponsored “English Q and A” was the most-accessed video with nearly 200,000 impressions across all platforms followed by Tiwi, Yolŋu Matha and Burarra videos (Fig. 1). These figures did not correlate with numbers of language speakers (Fig. 1). Perseverance with watching the content (views) was greatest for Murrinh-Patha then Yolŋu Matha videos (Fig. 1). However, some analytics from Facebook community notice boards where Miwatj Health shared Yolŋu Matha videos were unavailable, so data from this most commonly spoken language are likely to be underestimates. Indeed, engagement (user interaction with the post), for which data were available across all videos, was highest for Yolŋu Matha (Fig. 2). Despite Ngan’gikurunggurr being a minority language (~25 speakers), this video attracted 61,111 impressions, 16,744 views, 242 engagements and had a reach of 16,744. Of note, Miwatj Health reposted all five Yolŋu Matha videos a second time (13–19 April 2021) one month after the initial posting (26 March 2021). Reposting prompted further interest with an overall 74% increase in reach across the five videos: reach was 970 arising from the first post and 1687 arising from the second post.

Sponsored Facebook posts had substantially greater reach and impressions than organic Facebook posts. For example, the “English Q and A” was posted on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn. Data for this video was captured from 25 March 2021 – 01 July 2021. During this time NT Health sponsored the video on Facebook for 7 days (Cost: $1000. Date: 27/03/21-03/04/21) and the parliamentary member sponsored the video for one month (Cost: $600. Date: 26/05/21-25/06/21). Organic posting on the NT Health Facebook on 27/03/2021 resulted in reach of 5826 while the sponsored posts on both Facebook pages (NT Health and the politician’s) resulted in reach of 143,653, giving a cost per person reached of 1.1 cents (calculated as $1600/143,653).

Comparing platforms, videos were most accessed via Facebook boosted by sponsorship (total 784,046 impressions), followed by Twitter (32,069 impressions), Vimeo (7880 impressions) and LinkedIn (5215 impressions). YouTube data were not comparable as number of impressions were not available, with 645 total views for 15 videos. The federal government’s indigenous.gov.au was the only stakeholder to share videos on YouTube. The “English Q and A” which was the most popular video on other platforms only received two views over 3 months on the government YouTube page.

Despite attempts at wide distribution through social media networks and in locations where the target audience would be, only two of 10 RDH inpatients had seen the videos before they were approached for feedback. Murrinh-Patha speaker and RDH inpatient James and Burarra speaker and inpatient Michael both saw the videos on TV screens in the RDH foyer. James also saw the video on a TV screen at a local shop in his community of Wadeye. James watched the video a few times: “I didn’t really know about that vaccine….That’s why I kept watching it on the screen, on the big screen down at the shop”. AHPs Natalie, Deborah and Ashley suggested the younger generation should be targeted with Tik Tok content.

Discussion

This PAR project countered the “infodemic” spreading through the NT by co-designing 16 COVID-19 vaccine videos with First Nations leaders. The videos provided evidence-based information in eight First Nations languages plus English. Our findings are relevant to communication practitioner-researchers and health professionals who co-design resources with marginalised populations in jurisdictions outside of the NT. We learnt that the videos were effective because real people, not animations, could personalise information; presenters were trusted by, and accountable to, the target audience and First Nations languages were spoken. The co-design production process meant that presenters controlled the style in which information was delivered (direct to camera or Q and A with leader and expert); included time for presenters to consult with Elders on how best to localise messages for each community and time with clinicians to ensure the deeper story about vaccination was understood before recording began. These conversations also enhanced the clinician’s knowledge of community perspectives on vaccination. Importantly, we learnt that the video message should not simply instruct people to get vaccinated but instead individuals wanted to be empowered with information to make an informed choice. Our findings also contribute to the evidence that responding to conspiracy theories and “fake news” is limited; instead, the focus should be on building relationships that build trust between mainstream health services, that perpetuate systemic racism, and First Nations communities. Regarding social media we found that sponsoring posts was a sound investment; strategic reposting led to higher reach during critical events when demand for reliable information increased; and video reach didn't always align with language population size, suggesting other factors at play. Below our learnings are discussed in detail.

First Nations leaders, who were accountable to and therefore trusted by communities, featured in the videos. Trust is the cornerstone of effective communication. (Kerrigan et al., 2021; Ramsden, 2002; Topp et al., 2022) The leaders were best placed to deliver information because they understood, and shared, the historical, social, economic and political pressures which have contributed to vaccine hesitancy. (Kelly & Barker, 2016; Lazić & Žeželj, 2021; Stanley et al., 2021) Additionally, leaders acted as a bridge between family and friends and healthcare service providers who may not be trusted due to a history of racist medical practices in which First Nations people were experimented on. (Mayes, 2020; Mosby & Swidrovich, 2021) The possibility of being held to account meant some leaders did not want to be an “information intermediary” (Seale et al., 2022) between health services, which have been used as an apparatus of control, (Bashford, 2000; Bond, 2018) and their communities. In this project, video presenters understood the risks and shared information because they recognised the potential loss of life if reliable information was not urgently supplied. (Connolly et al., 2021).

The videos featured real people and elevated voices that had been further marginalised by the pandemic’s “infodemic” which was dominated by White voices. Health promotion campaigns for First Nations communities are commonly animated with an anonymised voice-over however animated characters cannot be held to account. Additionally, hearing impaired people cannot lipread animations. This is an important consideration as 43% of First Nations peoples experience hearing loss. (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) Therefore, we argue animations have limited impact and should be reconsidered as a favoured format. (Meppelink et al., 2015).

To counter the “wrong story,” information must be delivered in First Nations languages. Although information does not necessarily need to be delivered in the most widely spoken languages. In this project, presenters chose which language was most appropriate for their community. The pandemic was concerning to First Nations peoples globally who feared minority languages could be lost with the death of Elders who were the last fluent speakers. (Connolly et al., 2021) In video presenter Phillip Wilsons’ community of Nauiyu there were 10 language groups: a legacy of missionaries who forced people off their country to the mission site. (Morris et al., 2022) Phillip spoke both Ngan’gikurunggurr which had about 25 speakers and Kriol which had over 7000 speakers. (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022a) The Ngan’gikurunggurr video was a huge source of pride, immortalised the minority language and Elders who spoke Ngan’gikurunggurr became vaccine champions which had a flow-on effect throughout the community when the vaccine was distributed.

The videos were also successful because the co-design production process included time for video presenters to consult with community leaders and Elders who contributed to crafting the message. Effective dissemination of health information amongst First Nations language speakers during a pandemic requires more than translating a script from English and using anonymous interpreters to deliver a message.(Crooks et al., 2020; Kerrigan et al., 2020; Stanley et al., 2021) Our results support the argument that attempting to “deposit” people with information, or instructing them to ‘get the jab’, and expecting them to comply as per the traditional medical model of communication does not lead to behaviour change. (Freire, 1970; Marteau et al., 2015; Wild et al., 2021) To achieve health equity people require time to have conversations with trusted individuals in a supportive environment and access to information they have identified as important so “they are able to take control of those things which determine their health.”(World Health Organisation, 21 November 1986, p.2) Our goal was to facilitate collective knowledge production which involved cycles of knowledge exchange that occurred before, during and after the videos were recorded. During co-design and video production stages, the video presenters and clinicians established relationships. These relationships meant video presenters could contact clinicians with questions which arose from conversations during daily interactions in communities. (Wild et al., 2021) This was vital because the presenters were recognised from the vaccine videos and approached by people who wanted more information. For decades First Nations peoples have requested the “deep” story regarding health issues (Armstrong et al., 2022; Brennan, 1979; Devitt, 1998; Lowell et al., 2021) and these relationships, created through the co-design process, contributed to the deeper story being provided at an appropriate time and place for families. These conversations also deepened clinician’s knowledge of barriers and enablers influencing vaccination uptake in communities.

The flexibility embedded in the culturally responsive production process was vital. Decisions regarding healthcare, in many parts of the world, are made by families not individuals. (The Lancet 2022) The briefing document was supplied to presenters who honoured relationships with Elders and family by prioritising time to discuss information before video production began. (Armstrong et al., 2022; Burarrwanga et al., 2019; Lee, 2013) The aim of the briefing document was to ensure some uniformity of the clinical message across language groups to limit the possibility of contributing to the “infodemic”, but it also left room for communities to adapt the message to suit local contexts. This flexible approach improves communication strategies during a pandemic. (Ratzan et al., 2020) Many video presenters also chose to present the information as a conversation that included Elders and a clinician; the most effective way to improve vaccine uptake is to provide information in a “socially and culturally normative manner”. (Lazić & Žeželj, 2021, p.657) Additionally, the combination of leader and expert, used in the Yolŋu Matha, Kunwinkju and English videos has been found to be the most effective way to counter conspiracy theories. (Lazić & Žeželj, 2021).

Despite these successes, our results also show some dissatisfaction with the videos. First Nations health professionals were critical of some content and wanted presenters to personalise the information. Personal narratives can improve the effectiveness of COVID-19 public health campaigns compared to official impersonal guidance from health authorities. (Solnick et al., 2021) AHPs also questioned why risks associated with blood clots and religious concerns were not addressed. As documented in Table 1, information relating to blood clots was included however it was not detailed for reasons explained. Regarding religious concerns: we recognised that attempts to debunk misinformation “can only go so far” (Ball & Maxmen, 2020) and that “fake news” spreads amongst individuals who distrust health services. (Lazić & Žeželj, 2021; Rogers & Powe, 2022) Therefore a decision was made to attempt to build bridges between health services and communities by working with respected leaders. (Ball & Maxmen, 2020).

Video distribution relied heavily on Facebook which can be simultaneously harmful and also a safe space where First Nations peoples access culturally relevant health information. (Carlson et al., 2021; Hefler et al., 2019) We found Facebook continues to be popular among First Nations peoples however social media quickly evolves and content creators should respond to trends such as Tik Tok. (Carlson et al., 2021; Frazer et al., 2022) In Australia, Facebook is the most popular platform (67%) closely followed by YouTube (61%). (Park et al., 2021) Therefore an unexpected finding was the low numbers related to the indigenous.gov.au YouTube videos. The results may be attributed to the government branding of the YouTube page which could be a deterrent for First Nations peoples who continue to experience discrimination due to government policies which perpetuate harmful colonial ideals. (Elias et al., 2021; Watego et al., 2021)

Unsurprisingly, sponsored Facebook posts had the largest impact. The reach of sponsored Facebook posts was substantially greater than that achieved through organic sharing, for a very low cost per person (1.1 cents). In comparison to television advertising, sponsored Facebook posts are an inexpensive way to disseminate health information. (Allom et al., 2018) Interestingly video reach was not in proportion to language population size. The most popular videos in First Nations languages were Tiwi, Yolŋu Matha, Burarra, Kunwinjku, Ngan’gikurunggurr, Murrinh-Patha, Arrernte and Warlpiri; the descending order of language size is Yolŋu Matha, Arrernte, Warlpiri, Tiwi, Murrinh-Patha, Kunwinjku, Burarra, Ngan’gikurunggurr (Fig. 1). (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2022c) This may reflect differences in timing of video release in relation to vaccine rollout; use of social media platforms in different communities; internet access; and popularity of video presenters.

Another surprising finding was that video content can be effectively reused on Facebook. This overturns the myth among communication practitioners that content can only be used once. When Miwatj Health reposted the same five Yolŋu Matha videos one month after the initial posts the reposted videos had higher reach. Reposting the videos appeared to have been strategically timed to counter a frenzy of media activity in relation to AstraZeneca-associated blood clots and to support the start of the Miwatj Health vaccine rollout. (ABC News, 8 April 2021, 15 April 2021) These two events may have contributed to Yolŋu searching for trustworthy information and the subsequent larger impact.

Regarding study limitations, gathering social media analytics from stakeholders was troublesome. Not all stakeholders supplied data therefore numbers may underrepresent impact. In this research, the unreliability of social media data was countered by qualitative data. When the COVID-19 virus arrived in the NT in late 2021 the collaborations established as part of this PAR project resulted in an additional eight videos in eight languages which addressed community concerns relating to the ongoing “infodemic” plus questions regarding vaccines for children and boosters. As per feedback from the AHP’s in this study, a video in Kriol was created. The impact of those videos has been briefly described in The Lancet. (Kerrigan et al 2023) Finally, we recognise the limitations of a video to address the complexities relating to the pandemic and infodemic and accept that video resources are only one part of the strategy required to achieve public health goals. (Kelly & Barker, 2016).

Conclusion

This project serves as a valuable model for co-designing effective health communication resources with marginalised populations. By collaborating with trusted community leaders, speaking in local languages, and adopting a culturally responsive approach, the videos successfully countered the “wrong story” and built trust between health services and First Nations communities.

Developing public health communication strategies during a pandemic is challenging. We argue that the one size fits all approaches commonly used in public health can easily be refined so that information is meaningful, relevant and culturally appropriate. Resources need to grow from communities, not be imposed from subjugating authorities as per the top-down approach to health communication that has traditionally been favoured by health professionals. The project’s broader impact lies in its contribution to the evidence that successful health communication necessitates a shift in power dynamics. White individuals and mainstream service providers should step back from controlling the narrative and support the creation of resources that meet end-users needs. In this way, health communication can become more inclusive, relevant, and effective.

Ultimately, the project contributes to the broader evidence that successful health communication requires a focus on relationship-building, which fosters trust between healthcare providers and First Nations peoples. The trust built through the co-design is more important and enduring than the videos themselves, which are now out of date. Our project serves as a model for effective health communication that prioritises relationship-building, trust, and co-design, leading to more meaningful and equitable health outcomes.

Data availability

Data from the study are not publicly available due to ethical considerations. Data may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

ABC News. (2021). AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccine Blood Clotting Cause Still 'Unknown'. But The Maths Is Simple. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 19th October 2021 from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-04-08/covid19-vaccine-blood-clotting-az-explainer/100055638

ABC News. (2021). Indigenous Health Leaders Hatch Plan To Increase COVID-19 Vaccine Take-up In Remote NT. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 19th October from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-04-15/plan-to-increase-takeup-vaccine-nt-remote-areas/100069660

Allom V, Jongenelis M, Slevin T, Keightley S, Phillips F, Beasley S, Pettigrew S (2018) Comparing the cost-effectiveness of campaigns delivered via various combinations of television and online media. Front Public Health 6:83. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00083

Armstrong, E, Gapany, D, Maypilama, Ḻ, Bukulatjpi, Y, Fasoli, L, Ireland, S, & Lowell, A (2022) Räl-manapanmirr ga dhä-manapanmir - Collaborating and connecting: creating an educational process and multimedia resources to facilitate intercultural communication. Int J Speech-Lang Pathol 24:1−14

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022a). Language Statistics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Australian Bureau of Statistics

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022b). Northern Territory: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Population Summary. Retrieved 25th October from https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/northern-territory-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-population-summary

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022c). Table 1.2.1 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons who spoke an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander language at home by age(a), Census 2016. Canberra, Australia

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (N/A). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework: 1.15 Ear health. Australian Government Retrieved 12th October from https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/1-15-ear-health#findings

Ball P, Maxmen A (2020) The epic battle against coronavirus misinformation and conspiracy theories. Nature 581(7809):371–374. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01452-z

Bargallie, D (2020). Unmasking the Racial Contract: Indigenous voices on racism in the Australian Public Service. Aboriginal Studies Press

Barker R, Witt S, Bird K, Stothers K, Armstrong E, Yunupingu MD, Campbell N (2022) Co-creation of a student-implemented allied health service in a First Nations remote community of East Arnhem Land, Australia. Aust J Rural Health n/a:1–13

Barkham AM, Ersser SJ (2017) Supporting self-management by Community Matrons through a group intervention; an action research study. Health Soc Care Commun 25(4):1337–1346

Bashford A (2000) ‘Is White Australia possible’?’ Race, colonialism and tropical medicine. Ethn Racial Stud 23(2):248–271

Baum F, MacDougall C, Smith D (2006) Participatory Action Research. J Epidemiol Commun Health 60(10):854

Behrendt L (2021) The weaving power of Indigenous storytelling? Personal reflections on the impact of COVID-19 and the response of Indigenous communities. J Proc R Soc New South Wales 154:85–90

Bessarab, D & Ng'andu, B (2010). Yarning and Yarning as a Legitimate Method in Indigenous Research. Int J Crit Indig Stud 3(1):37–50

Biddle, N et al. (2021). Vaccine willingness and concerns in Australia: August 2020 to April 2021, ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods. Australian National University

Bond, C (3rd September 2018). Slice of LIME Seminar 9.3: ‘Outing’ Unconscious Bias, LIME Network, retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qhq_8GOQI50&list=PLHWJ7ihrg6b_3hjtnF-EBRZlDnZ81Z7ip&index=4&t=0s

Bond C, Brough M, Spurling G, Hayman N (2012) ‘It had to be my choice’ Indigenous smoking cessation and negotiations of risk, resistance and resilience. Health Risk Soc 14(6):565–581

Brennan, G (1979). The need for interpreting and translation services for Australian Aboriginals, with special reference to the Northern Territory: a research report. Canberra: Research Section, Dept. of Aboriginal Affairs

Burarrwanga, L, Ganambarr, R, Ganambarr-Stubbs, M, Ganambarr, B, Maymuru, D, Wright, S, Suchet-Pearson, S, & Lloyd, K (2019). Song Spirals: Sharing Women’s Wisdom Of Country Through Songlines. Allen & Unwin

Carlson, B (2013). The ‘New Frontier’: Emergent Indigenous Identities And Social Media. In: MM Harris, M Nakata, & B Carlson (eds.) The Politics of Identity: Emerging Indigeneity (pp. 147-168). University of Technology Sydney

Carlson B, Frazer R, Farrelly T (2021) “That makes all the difference”: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health-seeking on social media. Health Promot J Aust 32(3):523–531

Charmaz K (2014) Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd edn. Sage, London

Connolly M, Griffiths K, Waldon J, King M, King A, Notzon FC (2021) Overview: the international group for Indigenous health measurement and COVID-19. Stat J IAOS 37:19–24

Crooks K, Casey D, & Ward JS (2020). First Nations people leading the way in COVID-19 pandemic planning, response and management. Med J Aust; 213 (4)

Davies J, Davis J, Hosking K, Binks P, Gargan C, Greenwood-Smith B, Bukulatjpi S, Ngurruwuthun T, Dhagapan A, Wilson P, Santis T, Fuller K, McKinnon M, Mobsby M, Vintour-Cesar E (2022) Eliminating chronic hepatitis B in the Northern Territory of Australia through a holistic care package delivered in partnership with the community. J Hepatol 77:S239–S240

Delgado, R, Stefancic, J, & Harris, A (2017). Critical Race Theory (Third Edition): An Introduction, 3rd edn. New York University Press

Devitt, J (1998). Living On Medicine: A Cultural Study Of End-stage Renal Failure In Aboriginal People. IAD Press, Alice Springs, NT

Elias, A, Mansouri, F, & Paradies, Y (2021). Racism in Australia today. Palgrave Macmillan

Fontana, A, & Prokos, AH (2016). The Interview: From Formal To Postmodern. Routledge

Frazer R, Carlson B, Farrelly T (2022) Indigenous articulations of social media and digital assemblages of care. Digit Geogr Soc 3:100038

Freire, P 1970. Pedagogy Of The Oppressed (30th Anniversary Edition ed.). The Continuum International Publishing Group

Gallagher M (2020) Voice audio methods. Qual Res 20(4):449–464

Hall B (1985) Research, commitment and action: The role of participatory research. Int Rev Educ 30(3):289–299

Hefler, M, Kerrigan, V, Freeman, B, Boot, GR, & Thomas, DP (2019). Using Facebook to reduce smoking among Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: a participatory grounded action study.(Report). BMC Public Health 19(1): 615

Kelly MP, Barker M (2016) Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health 136:109–116

Kerrigan V, Lee AM, Ralph AP, Lawton PD (2020) Stay strong: aboriginal leaders deliver COVID-19 health messages. Health Promot J Aust 32(S1):203–204

Kerrigan V, McGrath SY, Majoni SW, Walker M, Ahmat M, Lee B, Cass A, Hefler M, Ralph AP (2021) From “stuck” to satisfied: Aboriginal people’s experience of culturally safe care with interpreters in a Northern Territory hospital. BMC Health Serv Res 21(1):548

Kerrigan V, Park D, Ross C, Davies J, Ralph AP (2023) Co-design effective health-literacy videos. The Lancet 401: 343

Kowal E (2008) The politics of the gap: indigenous australians, liberal multiculturalism, and the end of the self-determination era. Am Anthropol 110(3):338–348

Lazić A, Žeželj I (2021) A systematic review of narrative interventions: Lessons for countering anti-vaccination conspiracy theories and misinformation. Public Underst Sci 30(6):644–670

Lee, B (2013). Healing from the Dilly Bag: Holistic healing for your body, soul and spirit. Xlibris AU

Li HO-Y, Pastukhova E, Brandts-Longtin O, Tan MG, Kirchhof MG (2022) YouTube as a source of misinformation on COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic analysis. BMJ Global Health 7(3):e008334

Lowell A, Maypilama EL, Gundjarranbuy R (2021) Finding a pathway and making it strong: Learning from Yolŋu about meaningful health education in a remote Indigenous Australian context. Health Promot J Aust 32(Suppl 1):166–178

Marteau TM, Hollands GJ, & Kelly MP (2015). Changing population behavior and reducing health disparities: Exploring the potential of “choice architecture” interventions. In Kaplan RM, Spittel M, & David DH (eds.). Emerging Behavioural and Social Science Perspectives on Population Health. National Institutes of Health/Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Mayes C (2020) White Medicine, White Ethics: On the historical formation of racism in australian healthcare. J Aust Studies 44(3):287–302

McCaffery, K, Dodd, R, Cvejic, E, Ayre, J, Batcup, C, Isautier, J, Copp, T, Bonner, C, Pickles, K, Nickel, B, Dakin, T, Cornell, S, & Wolf, M (2020). Health Literacy And Disparities In Covid-19–related Knowledge, Attitudes, Beliefs And Behaviours in Australia. Public Health Research & Practice

Meppelink CS, van Weert JC, Haven CJ, Smit EG (2015) The effectiveness of health animations in audiences with different health literacy levels: an experimental study. J Med Internet Res 17(1):e11

Morris G, Groom RA, Schuberg EL, Dowden-Parker S, Ungunmerr-Baumann M-R, McTaggart A, Carlson B (2022) ‘I want to video it, so people will respect me’: Nauiyu community, digital platforms and trauma. Media Int Aust. 183(1):139–157

Mosby I, Swidrovich J (2021) Medical experimentation and the roots of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Can Med Assoc J 193(11):E381–E383

Newberry, C (2022). 16 Key Social Media Metrics to Track in 2022 https://blog.hootsuite.com/social-media-metrics/

Northern Territory Department of Health. (2021). Positive COVID-19 Case Update. Northern Territory Government Retrieved 7th February from https://coronavirus.nt.gov.au/updates/items/2021-03-17-positive-covid-19-case-update

Northern Territory Government. (2022). Aboriginal Languages in NT. Retrieved 25th May from https://nt.gov.au/community/interpreting-and-translating-services/aboriginal-interpreter-service/aboriginal-languages-in-nt

Park, S, Fisher, C, McGuinness, K, Lee, JY, & McCallum, K (2021). Digital News Report: Australia 2021, News Media Research Centre, Canberra, Australia

Ramsden, IM (2002). Cultural Safety and Nursing Education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu [Doctoral dissertation, Victoria University of Wellington]

Ratzan, S, Sommariva, S, & Rauh, L (2020). Enhancing global health communication during a crisis: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Res Pract 30: 3022010

Rogers R, Powe N (2022) COVID-19 information sources and misinformation by faith community. Inquiry 59:469580221081388

Schön, D (1987). The Reflective Practitioner. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CAL

Seale H, Harris-Roxas B, Heywood A, Abdi I, Mahimbo A, Chauhan A, Woodland L (2022) The role of community leaders and other information intermediaries during the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from the multicultural sector in Australia. Hum Soc Sci Commun 9(1):174

Simmons OE, Gregory TA (2003) Grounded action: achieving optimal and sustainable change. forum qualitative sozialforschung/forum. Qual Soc Res 4(3):1–7

Smith, LT (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples (2d edn. ed.). Zed Books, distributed in the USA exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan

Solnick RE, Chao G, Ross RD, Kraft-Todd GT, Kocher KE (2021) Emergency physicians and personal narratives improve the perceived effectiveness of COVID-19 public health recommendations on social media: a randomized experiment. Acad Emerg Med 28(2):172–183

Stanley F, Langton M, Ward J, McAullay D, Eades S (2021) Australian First Nations response to the pandemic: A dramatic reversal of the ‘gap’. Jof Paediatr Child Health 57(12):1853–1856

Therapeutic Goods Administration. (2019). Advertising COVID-19 vaccines to the Australian public. Australian Government. https://www.tga.gov.au/communicating-about-covid-19-vaccines

The Lancet (2022) "Why is health literacy failing so many?". The Lancet 400(10364):1655

Topp, SM, Tully, J, Cummins, R, Graham, V, Yashadhana, A, Elliott, L, & Taylor, S (2022). Building patient trust in health systems: a qualitative study of facework in the context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers’ role in Queensland, Australia. Social Science & Med 302: 114984

Tsirtsakis, A (18th March 2021). ‘There’s a lot of vaccine hesitancy out there’. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health experts speak to newsGP about steps to address misinformation and hesitancy ahead of phase 1b. Royal Australasian College of General Practitioners. Retrieved 25th May from https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/clinical/there-s-a-lot-of-vaccine-hesitancy-out-there

United Nations Secretary General. (2020). Cross-Regional Statement on “Infodemic” in the Context of COVID-19. In C. Australia, France, Georgia, India, Indonesia, Latvia, Lebanon, Mauritius, Mexico, Norway, Senegal and South Africa as the co-authors have the honor to transmit the following statement. (Ed.)

Watego, C, Singh, D, & Macoun, A (2021). Partnership for Justice in Health: Scoping paper on race, racism and the Australian health system. The Lowitja Institute

Wild, A, Kunstler, B, Goodwin, D, Onyala, S, Zhang, L, Kufi, M, Salim, W, Musse, F, Mohideen, M, Asthana, M, Al-Khafaji, M, Geronimo, MA, Coase, D, Chew, E, Micallef, E, & Skouteris, H (2021). Communicating COVID-19 health information to culturally and linguistically diverse communities: insights from a participatory research collaboration. Public Health Res Pract

World Health Organisation. (21 November 1986). Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion: First International Conference on Health Promotion

Zhao, Y, Wakerman, J, Zhang, X, Wright, J, Van Bruggen, M, Nasir, R, Duckett, S, & Burgess, P (2022). Remoteness, models of primary care and inequity: Medicare under-expenditure in the Northern Territory. Aust Health Rev

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the First Nations leaders and Elders who contributed but were not co-authors: Larissa Meneri & Purina Anderson from Children’s Ground, Larrakia Elder Aunty Bilawara Lee, Charlie King, Ms C, William Parmbuk, Tiwi Elder Maralampuwi Kurrupuwu, Yolŋu Elder Rosemary Gundjarrangbuy and Warlpiri Elder Theresa Napurrurla Ross. We would also like to thank Andy Peart from Bininj Kunwok Regional Language Centre, Mel Kean from Children’s Ground, Danielle Green from Formation Studios, Seide Ramadani from Mala’la Health Service, Paul Lawton, Angela Kelly and Josh Francis from Menzies School of Health Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VK, CR, PMW and JD conceived the project in consultation with all authors. All authors contributed to study design and implementation. VK, DP, CR, WT, AR and JD collected data. VK, DP, CR and APR conducted analysis. VK drafted the manuscript with input from all authors. APR prepared Figs. 1 and 2. All authors read and approved the final transcript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. This project was funded by a Menzies/ National Critical Care Trauma Response Centre COVID-19 Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Grant 2021. Vicki Kerrigan was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship and Improving Health Outcomes in the Tropical North: A multidisciplinary collaboration (HOT NORTH)’, (NHMRC GNT1131932). Anna P Ralph was supported by an NHMRC fellowship 1142011. Jane Davies was supported by an MRFF EL2 Investigator Grant (MRF1194615).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

At time of writing, JD and APR were employed by NT Health. No competing interests were declared by other authors.

Ethical approval

Approval to conduct the study was provided by the Northern Territory Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research Ethics Committee (HREC-2017-3007). The study conducted is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines.

Informed consent

Written consent to participate was given by all participants and all co-authors consented to publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kerrigan, V., Park, D., Ross, C. et al. Countering the “wrong story”: a Participatory Action Research approach to developing COVID-19 vaccine information videos with First Nations leaders in Australia. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 479 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01965-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01965-8