Abstract

Engaging with influencer posts has become a prevalent practice among adolescents on social media, exposing them to the combined elements of promotional content and entertainment in influencer marketing. However, the versatile and appealing nature of this content may hinder adolescents’ ability to engage in critical thinking and accurately interpret this hybrid form of advertising. This study aims to investigate adolescents’ capacity to critically process persuasive content shared by influencers, utilizing the five components of digital critical thinking outlined by Van Laar (2019): clarification, evaluation, justification, linking of ideas, and novelty. To analyze minors’ online experiences, a qualitative approach was employed involving twelve discussion groups with a total of 62 children and adolescents aged 11 to 17 in Spain. The findings indicate that the exercise of critical thinking in response to influencer marketing is closely associated with the cognitive and affective dimensions of advertising literacy in adolescents, while wamong them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In a consumer society, the cultivation of advertising literacy has long been recognized as culturally and socially necessary (Malmelin, 2010; Rozendaal et al., 2011). However, the relevance of advertising literacy has significantly increased with the widespread influence of digital technology throughout all stages of the consumer journey encompassing discovery, information search, offer evaluation, purchase decisions and product/service recommendation (Kietzmann et al., 2018; Shavitt and Barnes, 2020). The urgency for adolescents to develop advertising literacy has intensified due to the omnipresence of commercial information in various formats (Braun and Garriga, 2018; Cheng and Anderson, 2021; Humphreys et al., 2021; Kietzmann et al., 2018), such as the emergence of hybrid advertising that poses challenges in identification (Feijoo and Sádaba, 2022; Ikonen et al., 2017). Additionally, the accessibility of technology to audiences, of all age groups, including adolescents, and across various educational levels, particularly through mobile devices (An and Kang, 2014; Chen et al., 2013; Terlutter and Capella, 2013), exacerbates the need for promoting advertising literacy. The personal nature of screens and the exposure to commercial content amplify the urgency of addressing this issue (Oates et al., 2014).

Advertising literacy, which has existed even before the digital era, has now emerged as a distinct category among the various literacies that have evolved (Malmelin, 2010) due to the increasing digitalization of our daily lives (Selber and Selber, 2004). In addition to advertising literacy, other important literacies include algorithmic literacy (Dogruel et al., 2022; Shin et al., 2021), visual literacy (Avgerinou and Ericson, 1997), informational literacy (Behrens, 1994), and data literacy (Sagirolu and Sinanc, 2013), among others. While these literacies may primarily focus on specific perspectives that are currently of great interest, the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required for acquiring these literacies can be widely applicable across various domains. Some scholars argue that simplification is necessary to facilitate efforts in operationalizing these literacies (Kacinova and Sádaba, 2022).

Numerous studies on advertising literacy have emphasized that understanding advertising is necessary but insufficient for accurately processing digital messages (Rozendaal et al., 2011; An et al., 2014; Rozendaal et al., 2013; Vanwesenbeeck et al., 2017; Van Reijmersdal, 2017). This holds true particularly for content where the persuasive intent is more subtle, such as influencer marketing (Borchers, 2022; Van Dam and Van Reijmersdal, 2019). In addition to the cognitive dimension, considering the attitudinal dimension of advertising literacy is crucial as it plays a significant role in encouraging children to question and interpret advertisements. Attitudes such as skepticism (valuing a critical approach to advertising) or liking/disliking the phenomenon are instrumental in facilitating low-effort processing when children encounter new advertising formats. However, an examination of the results from the latest EU Kids Online questionnaire reveals that Spanish children aged 12–16 demonstrate some of the lowest levels of browsing and critical appraisal skills in Europe (Smahel et al., 2020).

Hence, programs aimed at enhancing advertising literacy among adolescents should not solely focus on the cognitive aspects but should also encompass the attitudinal domain, where critical thinking skills play a pivotal role. This article seeks to contribute to the ongoing discourse on advertising literacy in adolescents by employing a qualitative approach to assess their level of critical competence when confronted with influencer-generated branded content, characterized by subtle persuasive intent. The World Health Organization has coined the term “infodemic” to describe the overwhelming abundance of information individuals encounter on the internet, particularly on social networks. Therefore, it is imperative for individuals, especially children who are vulnerable during their formative years, to develop essential skills such as discerning content, identifying and selecting credible sources, curbing the spread of misinformation, and refraining from propagating falsehoods. All these skills foster responsible digital consumption.

The attitudinal and ethical dimension of adolescents’ advertising literacy in the face of influencer marketing

Leisure and social relations content holds significant relevance for children and adolescents in today’s digital landscape. Although screens have been used for educational purposes, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, entertainment continues to be a prominent component of digital device usage (IAB Spain, 2022), particularly among adolescents. The content consumed by minors on social networks often consists of sponsored posts and advertisements, encompassing both traditional and hybrid formats. Influencers frequently utilize this combination of formats to produce content that appeals to the varied interests of young audiences.

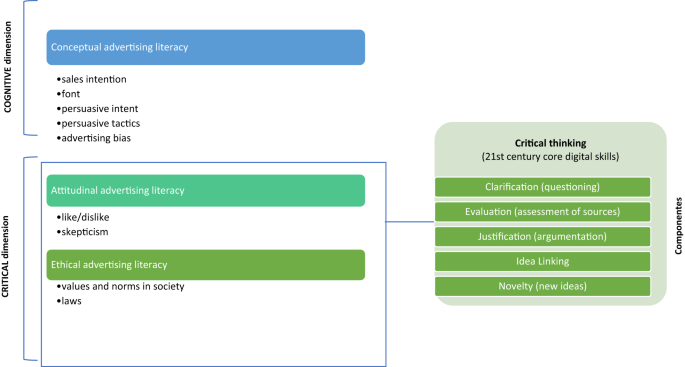

The traditional understanding of advertising literacy in children encompasses both cognitive and attitudinal dimensions (Rozendaal et al., 2011). The cognitive dimension requires the awareness of specific elements such as recognizing the intent to sell, the source, the persuasive intent, the employed tactics, and the advertising bias (Friestad and Wright, 1994; Livingstone and Helsper, 2006; Rozendaal et al., 2011). However, the rapid evolution of commercial tactics presents challenges in accurately processing advertising. Advertisers now employ branded content, adgames and influencer-generated content to quickly capture consumer attention and intention (van Berlo et al., 2021; van Dam and Van Reijmersdal, 2019; Hudders et al., 2016). Strategies used by advertisers include strategically placing content, appealing to audience emotions, offering customized experiences, and providing rewards and gifts in exchange for exposure (Feijoo and Sádaba, 2021). The increasing demands for stricter regulations in digital advertising sometimes surpassing those of television (Feijoo et al., 2020), and the suggestion of timely labeling of commercial content to facilitate identification (Lou and Yuan, 2019; Zozaya and Sádaba, 2022) further emphasize the need to address evolving advertising formats. Given the rapid evolution and ubiquity of advertising formats, developing persuasive knowledge is crucial for navigating this content, particularly among vulnerable audiences.

The attitudinal dimension of advertising literacy encompasses fostering a healthy level of skepticism and promoting critical reflection on the content individuals hear or see in terms of biases and persuasive intentions (Waiguny et al., 2014). Ideally, through this process of critical analysis, individuals would develop an informed response to advertising exposure.

When children come across formats that combine advertising and entertainment, they tend to engage in low-effort cognitive processing and fail to activate their developed associative knowledge network regarding the phenomenon (Mallinckrodt and Mizerski, 2007; Rozendaal et al., 2011; Rozendaal et al., 2013; An et al., 2014; Vanwesenbeeck et al., 2017; Van Reijmersdal et al., 2017). Numerous studies have focused on advergaming formats and have shown that merely recognizing the advertising intent of a message does not automatically translate into the ability to question or interpret the received content. This limited cognitive processing of non-traditional advertising formats is further influenced by several factors, such as the child’s primary attention being directed toward the recreational aspect of the format, often overshadowing the processing of the persuasive message. Consequently, advertising literacy programs should adopt an attitudinal perspective, emphasizing the promotion of critical attitudes towards advertising (Hudders et al., 2017; Vanwesenbeeck et al., 2017; Van Reijmersdal et al., 2017).

In recent years, the dimension of ethics has been recognized as a crucial aspect of advertising literacy (Adams et al., 2017; Hudders et al., 2017; De Jans et al., 2018; Sweeney et al., 2022; Zarouali et al., 2019). This addition reflects the growing pressure and diversification of advertising messages, as well as the utilization of various elements and resources aimed at achieving commercial objectives. Some advertising campaigns employ images, stories or tactics that deviate from social values or norms in order to capture the attention of potential consumers. Others attempt to circumvent legal restrictions by employing hybrid or inaccurately labeled formats or promoting unethical or illegal products or services, which may vary across cultures (Lee et al., 2011). To assess the potential impact of an advertising message or action on themselves, others, or society as a whole, consumers must enhance their ethical dimension (Adams et al., 2017; Zarouali et al., 2019).

The increasing digitization and its impact on consumption practices underscore the heightened necessity of advertising literacy across its three dimensions (Sweeney et al., 2022). Therefore, this study aims to integrate advertising literacy with the development of digital competence by emphasizing its interconnectedness with critical thinking. This integrated approach seeks to facilitate the comprehensive advancement of all three dimensions of advertising literacy. By exploring these synergies, the research intends to equip citizens, particularly adolescents as consumers of commercial content, with the ability to engage with such content in a healthy and conscientious manner. This endeavor aligns with prior research that examines the essential skills adolescents need to cultivate in the face of ubiquitous and pervasive commercial content (Hudders et al., 2017).

Critical thinking as a key competency in advertising literacy for adolescents

The development of critical thinking is recognized as a fundamental skill for educating new generations. Critical thinking entails an intellectually disciplined process of conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and actively evaluating information derived from reflection, reasoning, or communication which serves as a guide to belief and action (Scriven and Paul, 2007). It involves acquiring skills such as identifying the source of information, analyzing credibility, reflecting on information, and drawing conclusions (Linn, 2000; Shin et al., 2015). Additionally, critical thinking encompasses attitudes towards inquiry, a commitment to the accuracy of evidence, and the practical application of these attitudes and knowledge (Watson and Glaser, 1980).

During adolescence, the development of critical thinking becomes more prominent, relying on the advancement of formal thinking. It represents a sophisticated ability to solve complex problems, but prior training is essential to cultivate the skills necessary for evaluating one’s own thinking and the thinking of others (Delval, 1999). In Spain, the Royal Decree 1105/2014 of 26 December establishes the basic curriculum for Compulsory Secondary Education and the Baccalaureate. While critical thinking competency is not considered fundamental throughout the curriculum, it is addressed in a cross-cutting manner within the Secondary and Baccalaureate content.

The constant participation and immersion in the global online environment have elevated critical thinking to one of the seven essential digital skills necessary for engaging with 21st-century online content. Consequently, critical thinking is considered a priority competency by the European Union’s Innovation, Research, Culture, Education, and Youth Council (2022) in their efforts to promote digital literacy and combat misinformation. In the digital context, critical thinking serves as the foundation for developing reflective reasoning, which relies on evidence to validate or challenge the encountered information. This enables users to make informed judgments and decisions by considering the intentions behind publications and examining multiple perspectives (Amabile and Pillemer, 2012; Van Laar, 2019). An essential characteristic of critical thinking is the ability to independently evaluate arguments and evidence, detached from personal beliefs. This capacity to contrast ideas fosters the emergence of new viewpoints and contributes to meaningful discussions (Voskoglou and Buckley, 2012).

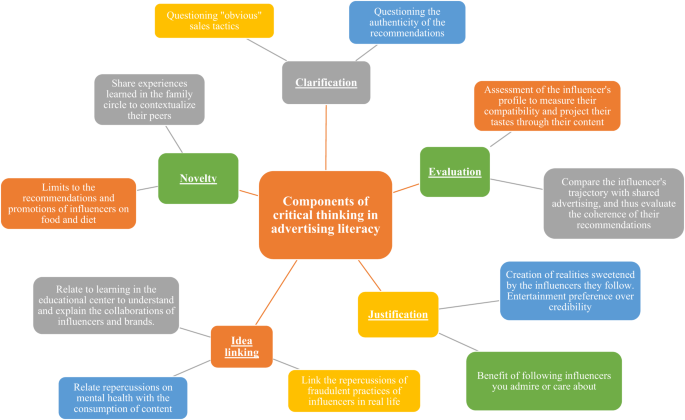

Van Laar (2019) identifies five components of digital critical thinking: clarification (asking and answering clarifying questions), evaluation (assessing the credibility of sources), justification (providing arguments based on personal experiences, reasoning, etc.), idea linking (connecting facts and ideas from personal experiences), and novelty (suggesting new ideas for discussion).

Figure 1 illustrates the advertising literacy model that serves as the foundation for this study (Rozendaal et al., 2011; Hudders et al., 2017). This model outlines the components of digital critical thinking that play a vital role in the attitudinal and ethical dimensions of the literacy process.

However, evidence from the European research network EU Kids Online (Garmendia et al., 2011, 2016, and 2019; Livingstone et al., 2011; Smahel et al., 2020) indicates that Spanish children consistently demonstrate the lowest levels of critical information literacy in Europe. These findings have remained consistent since 2015 (Garmendia et al., 2016) when Spanish children aged 9 to 16 displayed significantly lower levels of information literacy skills, such as contrasting information from different sources, compared to other activities. Only 48% of 9 to 16 year olds claimed to possess this ability, with notable gender and age differences. The most recent EU Kids Online questionnaire, which compares digital skills among children in 18 European countries, reveals alarming results, particularly for Spain. Spanish children aged 12 to 16 exhibit the lowest levels of browsing skills and critical appraisal in Europe (Smahel et al., 2020). Authors such as Van Deursen et al. (2016) argue for the necessity of new qualitative studies that enable a more in-depth exploration of digital skills, particularly those related to Web 2.0 activities and the technical aspects of internet use, to avoid oversimplifying the findings.

Adolescents may encounter difficulties in recognizing dynamic or entertaining advertising formats as advertisements and may face challenges in developing critical attitudes towards them. This is particularly evident in the case of influencer marketing, where influencers serve as brand ambassadors and promote products and services aligned with their personal profiles. They engage with their followers in a manner that resembles recommendations rather than sales pitches. Consequently, distinguishing between genuine product suggestions and paid collaborations can become challenging for the audience (van Dam and van Reijmersdal, 2019; Feijoo and Sádaba, 2021).

Previous research has investigated adolescents’ ability to recognize and respond to influencer-generated content with persuasive intent (Boerman and Van Reijmersdal, 2020; De Jans and Hudders, 2020; Van Reijmersdal and Rozendaal, 2020; Van Dam and Van Reijmersdal, 2019; van der Bend et al., 2023). Qualitative research conducted by Borchers (2022) with 132 German adolescents aged eleven to fifteen revealed their awareness of sponsored influencer posts. However, the study highlighted a tension between their understanding that sponsored content is advertising and the need to critically scrutinize it. Consequently, there is an urgent need for additional qualitative studies exploring adolescents’ online behavior and the strategies they employ to navigate the impact of persuasive content disseminated by influencers. Adopting an advertising literacy approach and aiming to foster the development of critical consumers, it is crucial to gather data on the presence of critical thinking dimensions when children and adolescents encounter messages disguised as entertainment but containing commercial intent (Feijoo and Sádaba, 2021).

The acquisition and development of critical thinking skills among adolescents are fundamental for advancing their advertising literacy. This serves as a crucial foundation for enhancing media and digital competence, especially considering the significant portion of content exposure occurring through internet-connected screens. Examining how critical thinking evolves during exposure to influencer marketing enables questioning, investigation, and learning. This perspective helps envision approaches that go beyond automatic responses influenced by biases against the commercial relationship between advertising and celebrities (McShane et al., 2013).

In light of these underlying factors, this article aims to address the following research question:

RQ1. To what extent do adolescents’ reactions to commercial content created by influencers encompass the components of critical thinking as defined by Van Laar (2019)?

Methodology

The objective of this study is to investigate how adolescents use critical thinking when exposed to influencer-generated content. A qualitative methodology will be employed to accomplish this aim. In assessing critical thinking, the study will adopt the five dimensions proposed by Van Laar (2019) as a framework.

Participants and selection process

For this study, a sample of 62 students between the ages of 11 and 17 (M = 14.14, SD = 1.9) was selected, comprising 59.7% female participants and 40.3% male participants. These students were drawn from multiple schools located across different regions of Spain, with 41.9% from the South, 22.6% from the Levante region, 19.3% from the North, 9.7% from the Canary Islands, and 6.5% from the central area.

Twelve virtual focus groups were conducted using platforms familiar to the participants, namely Zoom and Microsoft Teams between April and June 2021. To ensure more specific data across different segments of the sample, three focus groups were organized for each age group, categorized by socio-economic status (low, medium, and high). This approach allows for a comprehensive examination of the research participants’ perspectives. Additionally, the number of focus groups aligns with previous studies on children and adolescents in Spain, which commonly utilized 10 to 12 focus groups (Iglesias et al., 2015; Nuñez-Gomez et al., 2020). To create a comfortable environment for the younger interviewees, the focus groups were structured to include adolescents of the same age, minimizing any potential inhibitions caused by interactions with older participants.

The sample selection process for participation in the focus groups was conducted as follows. A non-probabilistic sample was chosen in collaboration with educational centers. The sample was defined based on two filtering criteria: age and the socio-economic profile and location of the school attended by the students. Regarding age, the participants were divided into four categories corresponding to their grade level: elementary students (6th graders), 1st cycle of ESO (7th and 8th graders), 2nd cycle of ESO (9th and 10th graders), and Baccalaureate (11th and 12th graders).

To classify schools, two criteria were employed: funding sources and geographical location. Schools were categorized as private, charter or public based on their funding sources. In terms of geographical location, it served as an initial indicator of the socioeconomic level of the households from which the participants came (Andrino et al., 2019). Subsequently, students were classified as attending high-income (+€30,000), medium-income (€11,450-€30,350), or low-income (-€11,450) SEG schools, using data provided by the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (Andrino et al., 2021).

Table 1 illustrates the distribution of the focus groups based on two predetermined filter variables:

This project encompassed various ethical considerations, particularly concerning the involvement of adolescents in the fieldwork. To address these concerns prior informed parental consent was obtained, in accordance with the guidance and oversight of the University Ethics Committee, which both financed and reviewed the research project and approved the final report.

Structure of the focus groups

This study employed a qualitative research design, utilizing focus groups as the primary data collection method to explore the opinions and attitudes of participants towards social networks. The use of focus groups facilitated the recording of adolescents’ perceptions, and their online behaviors through peer discussions. By analyzing the recorded sessions, researchers gained valuable insights into the online dynamics of the participants, including how adolescents share their experiences and engage in idea exchange with other users (Gómez et al., 1996).

The group session commenced with an overview of the objectives and an introduction of the group members. A preliminary exploratory question was posed to the participating students, seeking insights into their social media usage and their preferred platforms for engagement. Subsequently, the researchers delved into the central research questions, inquiring about the influencers they follow and the motivations behind their choices. This led the discussion towards an examination of the credibility and trustworthiness of these influencers. Lastly, the researchers gathered information on the participants’ perceptions of influencers as brand collaborators.

Table 2 shows the precise questions that served as a guide during the discussion.

The protocol for the focus groups began by individually verifying the audio and video settings for all participants. Additionally, they were reassured regarding the confidentiality and privacy of the recordings, with specific mention that access to the files was restricted to the participating researchers. It was emphasized that participation was voluntary, and participants were free to withdraw at any time. Each discussion group lasted approximately 50 min, and consisted of 4–6 participants, with one, exception where three participants were present due to an unforeseen circumstance preventing one attendee from joining at the last moment.

Procedure

The information analysis process is outlined as follows:

Phase 1: Verbatim transcription. During this phase, the recordings of each focus group were transcribed in a word-for-word manner.

Phase 2: Dimension identification. A team of researchers specializing in education and communication, with expertize in the use of social networks, collaboratively reached a consensus on identifying the dimensions of critical thinking. This process involved referring to the scientific literature reviewed in this study.

Phase 3: Categorization process. During this phase, the transcripts were carefully reviewed, and the statements were categorized based on the dimensions identified in the previous phase. The NVivo 12 Plus software was utilized to conduct content analysis of the transcripts.

Table 3 presents the adapted components of critical thinking, based on Van Laar’s (2019) framework, used by the authors to analyze the critical thinking abilities of adolescents when exposed to persuasive content from influencers.

Results

Contextualization

Instagram emerges as the most popular social network across all age groups, comprising 33.53% of total mentions, followed by TikTok at 23.87%, WhatsApp at 14.05%, and YouTube at 12.54%. However, platform preferences vary among different age groups. Primary school and first-cycle ESO students, show a preference for Tiktok, Youtube, Twitch, and Discord. As students’ progress to the second cycle of ESO and beyond, there is a decline in their usage of these platforms, with Instagram becoming the dominant choice, accounting for 47.10% of mentions in Baccalaureate. These usage patterns also reflect differences in users’ motivations. Younger users tend to consume more entertainment-oriented content on platforms like YouTube, TikTok, or Twitch, while older users focus move on communication with friends and family and information consumption. However, recreational usage remains prevalent, particularly among Baccalaureate students.

Participants’ opinions regarding influencers, displayed a high level of consistency across different age groups. They consistently acknowledged the commercial intent and economic nature underlying influencers’ activities and they deemed product promotion as an essential attribute defining an ‘influencer’. Consequently, influencers who do not meet this requirement are excluded from the definition.

Components of critical thinking in advertising literacy

Clarification

During the focus group discussions, participants shared their daily interactions with influencers and their understanding of their role as content creators. They expressed familiarity with influencers’ practices and their ability to question the intentions behind the shared content, which led adolescents, including children as young as 11 years old, to associate influencers with advertising. For instance, a female participant from the 6th grade, belonging to a high socio-economic group provided the following insight:

“If a company wants to sell a product, they often approach a highly popular individual, and request them to feature the product in videos. Many people are influenced to desire the product simply because that person possesses it” (FG1, female, elementary school, high SEG).

Furthermore, participants engaged in discussions questioning the authenticity of influencers’ appearances and raised concerns regarding the negative effects of such alterations. A participant from Baccalaureate, belonging to a low socio-economic group, shared,

“They edit their photos to create an unrealistic image of themselves, which makes us feel uncomfortable because we don’t look like them. They want us to believe that they look like that in real life” (FG9, female, Baccalaureate, low SEG).

This discussion also addressed the use filters, prompting questions about the credibility of recommendations. Another participant shared the following observation:

“Once, an influencer claimed to love a makeup product and wore it in the video, but I noticed she was also using a beauty filter. It surprised me because if the makeup was truly good, why did she need to rely on a filter?” (FG5, female, 2nd cycle ESO, high SEG).

Participants expressed skepticism regarding the authenticity of influencers’ content by examining their language, product presentations, and app usage.

Teenagers and adolescents view repetitive and unoriginal messages with suspicion often questioning the content when they detect common elements that deviate from the narrative:

“When I see someone excessively advertising and repeatedly saying things like ‘oh, this is so good, it’s super, super good, super cheap, super…’, I immediately become suspicious because it doesn’t seem normal to insist so heavily on the greatness of a product… I can tell that someone’s economic interests are involved” (FG3, male, 2nd cycle ESO, low SEG).

Evaluation

The characterization of influencers was identified as a crucial filter through which adolescents evaluate advertising sources. Influencers who solely exist on social networks were categorized in a way that limits their persuasive impact. One participant shared his perspective:

“Influencers and others who engage in gossip, they are less trustworthy. It’s possible that some are solely motivated by money, followers and similar motives. The genuine ones are perhaps the ones who pursue their passions without solely focusing on external gains” (FG3, male, 2nd cycle ESO, low SEG).

The participants recognized the significance of influencers having direct experience with the advertised product when assessing the appropriateness of influencer collaborations and validating recommendations on specific topics. Adolescents expect influencers to have a genuine connection with the product rather than promoting it solely for advertising purposes. One participant offered her viewpoint:

“’If someone says ‘Buy this racket because it’s the best’ …in this case, maybe yes, but if this person were an influencer, which is what we are discussing, someone who relies on social networks and is obligated to engage in this type of advertising, well, no” (FG7, female, 1st cycle ESO, medium SEG).

However, interviewees also emphasized the emotional connection and inspiration they felt towards influencers, extending beyond simply evaluating their expertize in content creation. A participant expressed

“I believe that when you follow someone and aspire to be like that person it’s because they fulfill certain emotional and inspirational criteria that validate you in a certain way” (FG4, male, 2nd cycle ESO, medium SEG).

Among the interviewed adolescents, the physical appearance of influencers was considered a valid criterion for providing dietary and esthetic recommendations to their audiences. As one participant explained:

“She has an amazing body, and she’s not very young anymore… she has three children, if I’m not mistaken, and she’s doing great. So, in the case of diets, I understand that their appearance serves as a reference. I don’t believe this girl has a reason to deceive me, I don’t think she does, because no one is paying her” (FG5, female, 2nd cycle ESO, high SEG).

However, it is important to note that this argument was not universally accepted and was not deemed valid for all recommendations.

Justification

Participants in the study justified the use of exaggerated content by influencers, considering it part of the social media game. They acknowledged the artificial nature of influencers’ online personas but found it entertaining. One participant shared her viewpoint:

“Even though they present a false life and such, it entertains us, you know? They somehow captivate us with their actions and that’s why we choose to follow them” (FG2, female, 1st cycle ESO, high SEG).

Additionally, participants noted that certain practices including controversy, were necessary for influencers to build their social media profiles, based on stories shared within their close circles. Another female participant explained:

“When you have over 15,000 followers on TikTok, you start getting paid based on the number of views. That’s what they do. They intentionally create controversy, and some TikTokers with 5 million views get paid around ten euros per video, or even more. I know this because my brother’s coworker gets paid, you know…” (FG10, female, 1st cycle ESO, low SEG).

Adolescents justify their decision to follow non-authentic profiles by emphasizing their appreciation for other aspects displayed by influencers such as shared interests and new content. As one participant expressed:

“I follow her because I enjoy seeing her fashion choices, discovering new things, and I also admire her style and what she does. Despite the possibility of her portraying a false life, I still appreciate her content” (FG2, female, 1st cycle ESO, high SEG).

Linking ideas and novelty

Participants leveraged their understanding of sales strategies to explain the persuasive techniques employed in advertising. A male participant explained:

“In argumentation there’s this one thing which is, to sell something or to promote an idea, you need to incorporate the endorsement of a respected individual” (FG4, male, 2nd cycle ESO, medium SEG).

In several focus groups, participants referenced lessons taught by their teachers to help explain the phenomenon of influencer marketing. As one participant stated:

“Our teacher informed us about how they try to sell things. It’s true, that if you’re selling a product, you can’t directly say ‘buy this’ or ‘buy it from me’. Instead, you might highlight its quality and durability, which could sway undecided individuals towards making a purchase” (FG3, male, 2nd cycle ESO, low SEG).

Participants drew on their academic knowledge to both explain and critique advertising techniques employed by influencers. For example, one participant provided a critique of the repetitive and tiresome nature of English instruction in YouTube videos. One male participant mentioned:

“The typical YouTuber who promotes Letyshops, and promises refunds, or excessive branding” (FG5, male, 2nd cycle ESO, high SEG).

Furthermore, participants engaged in a critical analysis of the ethics behind certain influencer collaborations highlighting the promotion of bookmakers as an example. As a participant explained:

“Several influencers, particularly Spanish ones, started endorsing bookmakers. They would tell all their followers ‘Hey look, I’ve earned so much by betting on Atleti or Madrid’ and they would display screenshots claiming their winnings… I believe they are exploiting people’s vulnerability” (FG3, male, 2nd cycle ESO, low SEG).

Despite criticisms directed towards content creator practices, participants engaged in debates regarding the impact of exposure to influencer content on the mental health of adolescents, as well as the potential distortion of reality it can cause. A participant stated:

“The problem with influencers and everything surrounding them is that above all, it affects the personality and imagination of everyone, right? It creates this image of a perfect world, a phenomenal life that, ultimately even affects our mental well-being” (FG6, female, Baccalaureate, high SEG).

In addition, some participants made connections between body and diet recommendations from influencers and their own struggles with eating issues. They also questioned the suitability of influencers as spokespersons for such matters, arguing that there are certain topics in which influencers should not offer opinions as they lack the necessary qualifications. As one participant expressed:

“There are certain things that can be promoted, but others are like ‘it’s not your business’ and should be left to a doctors or other medical professionals” (FG7, girl, 1st cycle ESO, medium SEG).

Some adolescents mentioned seeking clarification and guidance, from their parents, bringing new insights to the discussion. One participant shared his experience:

“My mother works as a publicist, and she recently collaborated with an influencer to promote a shopping center. The influencer visited the stores in the mall and promoted them” (FG2, male, 1st cycle ESO, high SEG).

Figure 2 summarizes the critical thinking components in the discourse of the participants.

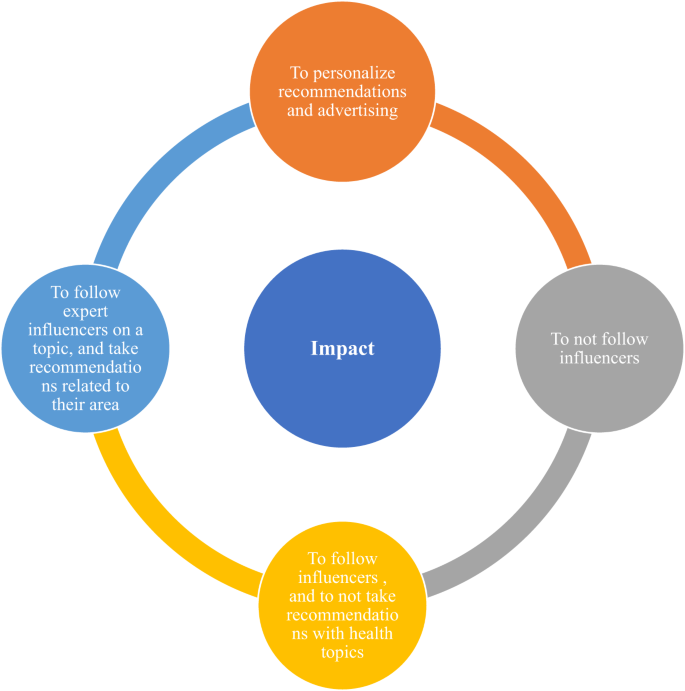

Consequences resulting from critical thinking

As a result of discussing persuasive practices and influencer marketing, interviewees demonstrated a critical attitude towards the latter and expressed the need for content creators, brands, and platforms to provide a less invasive social media experience. One participant from the same group stated:

“So, what I did was I read it the first time they published it, and then I directly personalized it to prevent similar recommendations” (FG2, male, 1st cycle ESO, high SEG).

The critical engagement of baccalaureate students from different socio-economic levels with influencer content was further outlined through three specific actions:

-

1.

Not following influencers: Baccalaureate students from various socio-economic backgrounds displayed a critical attitude towards influencer content which was reflected in their actions. One of these actions involved the decision not to follow influencers, recognizing the potential negative impact on their self-esteem and well-being. While this practice was not common among the interviewees, one participant explained her decision as follows:

“I have set a goal for myself to not follow any influencers […] because I don’t want to compare myself to anyone. I understand that what they show may not be entirely true, and I don’t want to idealize or view them as role models. It’s not something that contributes to my well-being” (FG6, girl, Baccalaureate, high SEG).

-

2.

Following influencers and considering their advice: Some participants, particularly adolescents rely on influencer recommendations when making purchase decisions. They evaluate the influencers’ profiles and the quality of their content before trusting their advice. One participant shared her experience, stating:

“I needed to buy a specific type of paint called Watch and what I did was look for paint artists, YouTubers (laughs) who recommended it and whose opinions I liked the most. I used them as a reference to purchase the drawing supplies” (FG12, female, Baccalaureate, medium SEG).

-

3.

Following influencers while being selective about their recommendations: In this scenario, an interviewee acknowledges that they priorize following influencers, but prefers the advice of true experts over influencer recommendations, particularly when the influencers lack expertize in a specific field, and are solely motivated by financial gain:

“Somehow I don’t always trust the products they promote, because I feel like they do it just for money. They don’t really care if it works for you or not. In those cases, I prefer to go to the pharmacy and listen to the recommendations of the pharmacist rather than relying solely on an influencer” (FG9, female, Baccalaureate, low SEG).

Overall, there was a noticeable trend towards more complex, critical, and well-informed discussions on influencer marketing among older age groups. This was particularly evident in the focus groups conducted with students in the 2nd cycle of ESO and Baccalaureate, as they demonstrated a greater ability to connect influencers’ activities with various outcomes, including the impact on body satisfaction for users.

Consequently, older age groups expressed concerns about the potential effects of influencer content on young people, such as the creation of unrealistic stereotypes that do not reflect the reality of the population., This can lead to feelings of frustration and dissatisfaction with life or one’s body. It is important to note that in the 12-13 age group, thinking tends to be concrete, as they may not perceive the future consequences of their actions and decisions. This age group is characterized by a more narcissistic view of self. However, as adolescents progress beyond this stage, they develop increasingly abstract thinking, abilities, enabling them to engage in critical analysis and discussions while seeking solutions and articulating well-founded arguments (Casas-Rivero and González-Fierro, 2005).

Figure 3 shows the consequent steps related to advertising literacy.

Discussion

This article explores the cognitive, attitudinal, and ethical dimensions of the advertising literacy model proposed by Rozendaal et al. (2011) and Hudders et al. (2016, 2017) which comprehensively encompass the processing of the advertising phenomenon. Understanding these dimensions becomes especially relevant when addressing the more subtle advertising formats that resemble entertainment (Feijoo and Sádaba, 2022; Ikonen et al., 2017). The present study provides insights into the questions raised by previous researchers (Hudders et al., 2017) regarding how adolescents engage with these new hybrid advertising formats and the essential skills that strengthen their associative networks, particularly at the ethical and affective/attitudinal levels (Mallinckrodt and Mizerski, 2007; Rozendaal et al., 2011; Rozendaal et al., 2013; An et al., 2014; Vanwesenbeeck et al., 2017; Van Reijmersdal et al., 2017). It is increasingly crucial to comprehend this area as adolescents are increasingly exposed to influence marketing, an advertising format characterized by the mingling of persuasive and entertaining content (Borchers, 2022; Van Dam and Van Reijmersdal, 2019). Within this context, the development of critical thinking skills becomes paramount for adolescents, making it relevant to examine its application at a dispositional level in the current advertising landscape.

Van Laar (2019) identified five dimensions clarification, evaluation, justification, linking ideas, and novelty for assessing critical thinking in the digital context. This study provides evidence that adolescents generally apply these dimensions when encountering influencer marketing. The findings are based on an analysis of statements made by adolescents during the discussion groups. Participants demonstrated an understanding that product and brand promotion are inherent to the role of an influencer and recognized their intentional and persuasive strategies. They were critical in evaluating influencers by questioning and assessing their experiences and origins before granting them credibility in their storytelling.

Similarly, the emotional connection that adolescents feel towards influencers is crucial in determining the credibility of their commercial arguments (Feijoo and Sádaba, 2021). Adolescents demonstrate a tendency to contextualize the content displayed by influencers and exercise caution in detecting the use of reality-altering tools, such as filters. They also recognize that social media portrays only the positive and friendly aspects of influencers’ lives aiming to foster an aspirational relationship between followers and celebrities. Older adolescents, particularly those in the 2nd cycle of ESO and Baccalaureate, contribute new ideas to the discussion highlighting the expectations generated by such publications, the promotion of ideal esthetics, and the potential impact on their audience’s well-being. Notably, older participants demonstrate a more advanced ability to link ideas and add nuance to the discussions, indicating a higher level of abstract thinking (Casas-Rivero and González-Fierro, 2005).

However, it appears that adolescents are willing to accept exaggeration and superficiality as inherent features of influencer content and social media platforms. As a result, they tend to incorporate these traits into their digital routines, sometimes creating two profiles on the same platform. One profile serves as a curated showcase of their “public life” accessible to relatives, friends, and acquaintances, while the other remains more personal and private, accessible only to their closest circle.

Thus, it can be concluded that the adolescents interviewed in this study demonstrate a thoughtful approach when confronted with influencers’ persuasive messages. They exhibit awareness of and engagement with the cognitive and attitudinal dimensions of advertising literacy as they filter and evaluate these messages. In fact, they apply critical thinking skills by questioning the tactics used, assessing the influencer’s connection to the promoted product and their own preferences recognizing exaggeration and relativism as inherent to the influencer industry, and considering the emotional impact of these publications on their lives. They also propose solutions to counterbalance any potential negative effects on their self-esteem. It is worth noting that influencer marketing is a familiar advertising phenomenon to young audiences. It would be valuable to investigate whether adolescents apply the same components of critical thinking when faced with other hybrid practices, such as advergaming.

The scope adolescents’ critical thinking now extends recognizing the advertising phenomenon. They are aware of the rules of the commercial game (Borchers, 2022; van der Bend et al., 2023), and incorporate them into their digital behavior. However, they do not appear to thoroughly examine the ethical appropriateness of the resources employed (Sweeney et al., 2022). As previous research by Hudders et al. (2017) suggests, the ability to evaluate advertising from a moral standpoint is increasingly crucial, especially considering the intertwining of advertising formats with entertainment in the digital realm.

Individual ethical analysis of advertising relies on people’s knowledge and life experience regarding societal values and norms (Lee et al., 2011). It is worth noting that in Spain, where this study was conducted, there is currently no specific regulation concerning influencer marketing, despite the launch of some self-regulatory initiatives promoting more ethical use. None of the adolescents mentioned the normative dimension or the moral implications of whether promotional content should be explicitly identified as such, as observed in the investigations conducted by Van Dam and Van Reijmersdal (2019) or Sweeney et al. (2022) regarding influencer-sponsored videos.

Thus, while this research indicates that adolescents are employing critical thinking in cognitive and affective aspects, particularly, at the attitudinal level (Borchers, 2022; Rozendaal et al., 2011; Hudders et al., 2017), the moral dimension is largely overlooked. Although topics such as the use of filters and the utilization of personal data to tailor commercial messages were mentioned, no explicit references or reflections on the moral suitability of influencer marketing or evaluations of moral exaggeration were observed.

In the context of hybrid digital formats, it is crucial to incorporate the ethical dimension into advertising literacy for younger generations. This dimension enables adolescents to distinguish between right and wrong and to understand its impact of their choices the individual and societal behavior. Only by integrating ethics into advertising literacy can we truly claim that critical thinking has been achieved (Van Laar, 2019). This is especially important in an ever-changing digital environment where commercial content continually evolves (Borchers, 2022; Braun and Garriga, 2018; Cheng and Anderson, 2021; Humphreys et al., 2021; Kietzmann et al., 2018; Feijoo and Sádaba, 2022; Ikonen et al., 2017).

Conclusions

In a context where children and adolescents are spending an increasing amount of time on the internet, it is crucial to ensure that they possess the necessary competences to navigate the digital environment effectively, both in terms of managing risks and capitalizing on opportunities. While commercial interests are prevalent in Western societies (Kietzmann et al., 2018; Shavitt and Barnes, 2020), it is of utmost importance to teach young users to identify, process and understand the ethical implications of advertising (Chen et al., 2013; Terlutter and Capella, 2013; An and Kang, 2014; Oates et al., 2014;; Ikonen et al., 2017; Braun and Garriga, 2018; Kietzmann et al., 2018; Cheng and Anderson, 2021; Humphreys et al., 2021; Feijoo and Sádaba, 2022).

Digital competence programs have gained attention in recent decades, but it is essential to incorporate the perspective of advertising literacy to address the experiences of young users online, where ads are present in various forms, including subtle and difficult-to-identify modes such as influencer marketing (Rozendaal et al., 2011; Adams et al., 2017; Hudders et al., 2017; De Jans et al., 2018; Van Dam and Van Reijmersdal, 2019; Zarouali et al., 2019; Sweeney et al., 2022; Borchers, 2022; Kacinova and Sádaba, 2022). This advertising literacy should encompass cognitive, attitudinal and ethical dimensions, with critical thinking playing a crucial role.

Implications and future research

The findings of this study have significant implications for the design of advertising and media literacy programs for adolescents. The digital literacy for the younger generation should incorporate an ethical dimension to help them differentiate between good and bad content and understand its impact on individuals and society. This is crucial for fostering critical thinking, a vital skill in the digital landscape where content can often be ambiguous. In an educational context, it is imperative to equip future citizens with digital intelligence and cultivate humanities that align with the demands of the digital age.

The present study, conducted through qualitative methodology, offers valuable insights into the critical capacity of adolescents in interpreting emerging digital advertising formats that combine persuasive intent with entertainment. However, the study acknowledges its limitations in terms of the exploratory nature of qualitative approaches and the inherent constraints of the research design: the sample size precludes generalization of conclusions. For this, further research is needed to replicate and expand on these findings in different cultural contexts, as in the recognition of the ethical dimension of advertising can be influenced by cultural factors. Additionally, it is essential to explore how critical thinking manifests among adolescents when exposed to other digital advertising formats like advergaming or native advertising. This future research should also delve into the ethical dimension of advertising literacy, taking into account the influence of adolescents’ home and educational backgrounds.

Data availability

The data presented in this study can be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Adams B, Schellens T, Valcke M (2017) Promoting adolescents’ moral advertising literacy in secondary education. Comunicar 52:93–103. https://doi.org/10.3916/C52-2017-09

Amabile TM, Pillemer J (2012) Perspectives on the social psychology of creativity. J Creat Behav 46(1):3–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.001

An S, Jin HS, Park EH (2014) Children’s advertising literacy for advergames: perception of the game as advertising. J Advert 43(1):63–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2013.795123

An S, Kang H (2014) Advertising or games? Advergames on the internet gaming sites targeting children. Int J Advert 33(3):509–532. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-33-3-509-532

Andrino B, Grasso D, Llaneras K (2019 October 4) School for the rich, school for the poor? How public and private schools segregate by social class. El País. https://elpais.com/sociedad/2019/09/30/actualidad/1569832939_154094.html. Accessed 14 May 2023

Andrino B, Grasso D, Llaneras K, Sánchez A (2021) Income map of Spain, street by street. El País. https://elpais.com/economia/2021-04-29/el-mapa-de-la-renta-de-los-espanoles-calle-a-calle.html. Accessed 14 May 2023

Avgerinou M, Ericson J (1997) A review of the concept of visual literacy. Br J Educ Technol 28(4):280–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8535.00035

Behrens S (1994) A conceptual analysis and historical overview of information literacy. Coll Res libraries 55(4):309–322. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl_55_04_309

Boerman SC, Van Reijmersdal EA (2020) Disclosing influencer marketing on YouTube to children: the moderating role of para-social relationship. Front Psychol 10:3042. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03042

Borchers NS (2022) Between skepticism and identification: a systematic mapping of adolescents’ persuasion knowledge of influencer marketing. J Curr Issues Res Advert 43(3):274–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2022.2066230

Braun A, Garriga G (2018) Consumer journey analytics in the context of data privacy and ethics. In: Linnhoff-Popien C, Schneider R, Zaddach M (eds) Digital marketplaces unleashed. Springer, Berlin, pp. 663–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-49275-8_59

Casas Rivero JJ, González Fierro MJ (2005) Desarrollo del adolescente. Aspectos físicos, psicológicos y sociales. Pediatr Integral 9(1):20–24. https://repositorio.upn.edu.pe/bitstream/handle/11537/25269/desarrollo_adolescente%282%29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Chen Y, Zhu S, Xu H, Zhou Y (2013) Children’s exposure to mobile in‐app advertising: An analysis of content appropriateness. Proceedings of the SocialCom 2013, International Conference on Social Computing. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, pp. 196–203. https://doi.org/10.1109/SocialCom.2013.36

Cheng M, Anderson CK (2021) Search engine consumer journeys: exploring and segmenting click-through behaviors. Cornell Hosp Q 62(2):198–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965520924649

De Jans S, Hudders L (2020) Disclosure of vlog advertising targeted to children. J Interact Mark 52:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2020.03.003

De Jans S, Vanwesenbeeck I, Cauberghe V, Hudders L, Rozendaal E, van Reijmersdal EA (2018) The development and testing of a child-inspired advertising disclosure to alert children to digital and embedded advertising. J Advert 47(3):255–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2018.1463580

Delval J (1999) El desarrollo humano, 4th edn. Siglo XXI, Madrid

Dogruel L, Masur P, Joeckel S (2022) Development and validation of an algorithm literacy scale for Internet users. Commun Methods Meas 16(2):115–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2021.1968361

European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture (2022) Guidelines for teachers and educators on tackling disinformation and promoting digital literacy through education and training, Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2766/28248. Accessed 8 Mar 2023

Feijoo B, Sádaba C (2022) When ads become invisible: minors’ advertising literacy while using mobile phones. Media Commun 10(1):339–349. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v10i1.4720

Feijoo B, Sádaba C (2021) Is my kid that naive? Parents’ perceptions of their children’s attitudes towards advertising on smartphones in Chile. J Child Media 15(4):476–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2020.1866626

Feijoo B, Sádaba C, Bugueño S (2020) Ads in videos, games, and photos: Impact of advertising received by children through mobile phones. Prof de la Inf 29:e290630. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.nov.30

Friestad M, Wright P (1994) The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. J Consum Res 21(1):1–31. https://doi.org/10.1086/209380

Garmendia M, Jiménez E, Karrera I, Larrañaga N, Casado MA, Martínez G, Garitaonandia C (2019) Actividades, Mediación, Oportunidades y Riesgos online de los menores en la era de la convergencia mediática. Instituto Nacional de Ciberseguridad (INCIBE), León (Spain). https://addi.ehu.es/bitstream/handle/10810/49632/informe-eukidsonline-2018.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 10 Feb 2023

Garmendia M, Jiménez E, Casado MA, Mascheroni G (2016) Net Children Go Mobile: Riesgos y oportunidades en internet y el uso de dispositivos móviles entre menores españoles (2010-2015). Red.es, Universidad del País Vasco. https://netchildrengomobile.eu/ncgm/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Net-Children-Go-Mobile-Spain.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb 2023

Garmendia M, Garitaonandia C, Martínez G, Casado MA (2011) Riesgos y seguridad en internet: Los menores españoles en el contexto europeo. Universidad del País Vasco y EU Kids Online. https://www.observatoriodelainfancia.es/oia/esp/descargar.aspx?id=3155&tipo=documento. Accessed 10 Feb 2023

Gómez GR, Flores JG, Jiménez EG (1996) Metodología de la investigación cualitativa. Ediciones Aljibe, Málaga

Hudders L, Cauberghe V, Panic K (2016) How advertising literacy training affect children’s responses to television commercials versus advergames. Int J Advert 35(6):909–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1090045

Hudders L, De Pauw P, Cauberghe V, Panic K, Zarouali B, Rozendaal E (2017) Shedding new light on how advertising literacy can affect children’s processing of embedded advertising formats: a future research agenda. J Advert 46(2):333–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1269303

Humphreys A, Isaac MS, Wang RJH (2021) Construal matching in online search: applying text analysis to illuminate the consumer decision journey. J Mark Res 58(6):1101–1119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022243720940693

IAB Spain (2022). Social Media Study 2022. https://iabspain.es/estudio/estudio-de-redes-sociales-2022/. Accessed 10 Feb 2023

Iglesias EJ, Larrañaga MSG, del Río MAC (2015) Children’s perception of parental mediation regarding Internet risks. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 70:49–68

Ikonen P, Luoma-Aho V, Bowen SA (2017) Transparency for sponsored content: analysing codes of ethics in public relations, marketing, advertising and journalism. Int J Strateg Commun 11(2):165–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2016.1252917

Kačinová V, Sádaba C (2022) Conceptualization of media competence as an “augmented competence”. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 80:21–38. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2022-1514

Kietzmann J, Paschen J, Treen E (2018) Artificial intelligence in advertising: How marketers can leverage artificial intelligence along the consumer journey. J Advert Res 58(3):263–267. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2018-035

Lee T, Sung Y, Marina Choi S (2011) Young adults’ responses to product placement in movies and television shows: a comparative study of the United States and South Korea. Int J Advert 30(3):479–507. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-30-3-479-507

Linn MC (2000) Designing the knowledge integration environment. Int J Sci Educ 22(8):781–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/095006900412275

Livingstone S, Helsper EJ (2006) Does advertising literacy mediate the effects of advertising on children? A critical examination of two linked research literatures in relation to obesity and food choice. J Commun 56(3):560–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00301.x

Livingstone S, Haddon L, Görzig A, Ólafsson K (2011) Risks and safety on the internet: the perspective of European children. Full findings. EU Kids Online, LSE, London, Accessed 20 Jan 2023 http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/33731/1/Risks%20and%20safety%20on%20the%20internet%28lsero%29.pdf

Lou C, Yuan S (2019) Influencer marketing: how message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. J Interact Advert 19(1):58–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1533501

Mallinckrodt V, Mizerski D (2007) The effects of playing an advergame on young children’s perceptions, preferences, and requests. J Advert 36(2):87–100. https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091‐3367360206

Malmelin N (2010) What is advertising literacy? Exploring the dimensions of advertising literacy. J Vis Lit 29(2):129–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/23796529.2010.11674677

McShane P, Gillis-Drage A, Benton J (2013) Introducción al pensamiento crítico. Plaza y Valdés SL, Madrid

Núñez-Gómez P, Rodrigo-Martín L, Rodrigo-Martín I, Mañas-Viniegra L (2020) Self-confidence and career expectations in minors as a function of gender. The use of creativity to determine the aspirational model. Revista espacios 41:41–57

Oates C, Newman N, Tziortzi A (2014) Parent’s beliefs about, and attitudes towards, marketing to children. In: Blades M, Oates C, Blumberg F, Gunter B (eds.) Advertising to children: new directions, new media. Springer, London, pp. 115–136. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137313256

Rozendaal E, Lapierre MA, Van Reijmersdal EA, Buijzen M (2011) Reconsidering advertising literacy as a defense against advertising effects. Media Psychol 14(4):333–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2011.620540

Rozendaal E, Slot N, van Reijmersdal EA, Buijzen M (2013) Children’s responses to advertising in social games. J Advert 42(2-3):142–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2013.774588

Sagiroglu S, Sinanc D (2013) Big data: a review. Paper presented at 2013 international conference on collaboration technologies and systems (CTS), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–24 May 2013

Scriven M, Paul R (2007) Defining critical thinking. The critical thinking community: foundation for critical thinking. https://www.criticalthinking.org/template.php?pages_id=766. Accessed 3 March 2023

Selber S, Selber SA (2004) Multiliteracies for a digital age. SIU Press, Illinois

Shavitt S, Barnes AJ (2020) Culture and the consumer journey. J Retail 96(1):40–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2019.11.009

Shin D, Rasul A, Fotiadis A (2021) Why am I seeing this? Deconstructing algorithm literacy through the lens of users. Internet Res 32(4):1214–1234. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-02-2021-0087

Shin H, Ma H, Park J, Ji ES, Kim DH (2015) The effect of simulation courseware on critical thinking in undergraduate nursing students: Multisite pre-post study. Nurs Educ Today 35(4):537–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2014.12.004

Smahel D, Machackova H, Mascheroni G, Dedkova L, Staksrud E, Ólafsson K, Livingstone S, Hasebrink U (2020) EU Kids Online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries. EU Kids Online. https://www.eukidsonline.ch/files/Eu-kids-online-2020-international-report.pdf. Accessed 1 Mar 2023

Sweeney E, Lawlor MA, Brady M (2022) Teenagers’ moral advertising literacy in an influencer marketing context. Int J Advert 41(1):54–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2021.1964227

Terlutter R, Capella ML (2013) The gamification of advertising: Analysis and research directions of in‐game advertising, advergames, and advertising in social network games. J Advert 42(2/3):95–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2013.774610

Van Berlo ZM, van Reijmersdal EA, Eisend M (2021) The gamification of branded content: a meta-analysis of advergame effects. J Advert 50(2):179–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2020.1858462

Van Dam S, van Reijmersdal EA (2019) Insights in adolescents’ advertising literacy, perceptions an responses regarding sponsored influencer videos and disclosures. Cyberpsychology 13(2):2. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2019-2-2

Van der Bend DLM, Gijsman N, Bucher T, Shrewsbury VA, van Trijp H, van Kleef E (2023) Can I @handle it? The effects of sponsorship disclosure in TikTok influencer marketing videos with different product integration levels on adolescents’ persuasion knowledge and brand outcomes. Comput Hum Behav https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107723

Van Deursen AJAM, Helsper EJ, Eynon R (2016) Development and validation of the Internet Skills Scale (ISS). Inf Commun Soc 19(6):804–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1078834

Van Laar E (2019) What are E-ssential skills?: A multimethod approach to 21st-century digital skills within the creative industries. Dissertation, University of Twente. https://ris.utwente.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/146623249/Dissertation_Ester_van_Laar.pdf. Accessed 1 Mar 2023

Van Reijmersdal EA, Rozendaal E, Smink N, Van Noort G, Buijzen M (2017) Processes and effects of targeted online advertising among children. Int J Advert 36(3):396–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2016.1196904

Van Reijmersdal EA, Rozendaal E (2020) Transparency of digital native and embedded advertising: opportunities and challenges for regulation and education. Commun 45(3):378–388. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2019-0120

Vanwesenbeeck I, Walrave M, Ponnet K (2017) Children and advergames: the role of product involvement, prior brand attitude, persuasion knowledge and game attitude in purchase intentions and changing attitudes. Int J Advert 36(4):520–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2016.1176637

Voskoglou MG, Buckley S (2012) Problem solving and computational thinking in a learning environment. Egypt Comp Science J 36(4):28–46. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1212.0750

Waiguny MK, Nelson MR, Terlutter R (2014) The relationship of persuasion knowledge, identification of commercial intent and persuasion outcomes in advergames—the role of media context and presence. J Consum Policy 37(2):257–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-013-9227-z

Watson G, Glaser E (1980) Watson–Glaser critical thinking appraisal. The Psychological Corporation, England

Zarouali B, De Pauw P, Ponnet K, Walrave M, Poels K, Cauberghe V, Hudders L (2019) Considering children’s advertising literacy from a methodological point of view: past practices and future recommendations. J Curr Issues Res Advert 40(2):196–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2018.1503109

Zozaya L, Sádaba C (2022) Disguising commercial intentions: sponsorship disclosure practices of mexican instamoms. Media Commun 10(1):124–135. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v10i1.4640

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Government of Spain under I+D+i Project ref. PID2020‐116841RA‐I00. The research was also funded by the Research Plan of the International University of La Rioja (UNIR). We also wish to thank Angela Gearhart for her translation of the original manuscript into English.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BF has carried out the funding acquisition, the methodology, the validation, the formal analysis, the investigation, the resources, and data curation. LZ contributed to the formal analysis and exposition of results. CS has developed the theorical framework and the writing—original draft preparation. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the International University of La Rioja, Spain (code PI:002/2021).

Informed consent

An informed consent was obtained from all their legal guardians of minors’ participants prior to their involvement in the research. Before participating in the focus group, the schools were provided with a consent document by the social studies company that assisted in contacting the sample. This document was given to the legal guardians, who had to sign and return it to the company. The consent document explained the purpose of the research project, the benefits of participating, and the sociodemographic data that would be requested from the minors. It was emphasized that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. The information obtained would only be used for the specific purposes of the study, and the minors had the right to decline to answer any questions they did not wish to answer.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feijoo, B., Zozaya, L. & Sádaba, C. Do I question what influencers sell me? Integration of critical thinking in the advertising literacy of Spanish adolescents. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 363 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01872-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01872-y