Abstract

The foci of voluminous bibliometric studies on ‘language and linguistics’ research are limited to specific sub-topics with little regional context. Given the paucity of relevant literature, we are relatively uninformed about the regional trends of ‘language and linguistics’ research. This paper aims to analyze research developments in the field of ‘language and linguistics’ in 13 Asian countries: China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, Japan, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Turkey. This study probed 30,515 articles published between 2000 and 2021, assessing each within four major bibliometric perspectives: (1) productivity, (2) authorship and collaborations, (3) top keywords, and (4) research impact. The results show that, in Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research, the relative contributions made by the 13 countries comprised 85% of the total number of articles produced in Asia. The other 28 Asian countries’ output, for the past two decades, never surpassed that of the individual 13 countries. Among the 13 countries, the most prolific were China, Japan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan; they especially published most articles in international core journals. In contrast, Indonesia, Iran, and Malaysia published more in regional journals. Traditionally, research on each country’s national language(s) and dialects were chiefly conducted throughout a period of 22 years. In addition, coping with internationalization worldwide, from 2010 onward, topics related to ‘English’ were of burgeoning interest among Asian researchers. Asian countries often collaborated with each other, and they also exerted a high degree of research influence on each other. The present study was designed to contribute to the literature on the comprehensive bibliometric analyses of Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bibliometric studies that analyze the trends of a research field in a certain region are generally developed from the a priori postulate that regional characteristics (e.g., economic, cultural, political, demographic) play critical roles in shaping such trends (De Filippo et al., 2020; Jokić et al., 2019; McManus et al., 2020; Scarazzati and Wang, 2019). To discover regionally characterized trends, for instance, such studies investigate the following: (1) how much the region has contributed to the research field, (2) how impactful the regional research was, (3) how the regional researchers participated in the field, (4) what the regionally popular research topics were, and (5) which publication types and venues were most highly regarded. These studies’ findings may enable regional academic institutions, governments, and funding agencies to conduct informed evaluations of research performance and make strategic decisions about resource allocation (Lei and Liu, 2018). Additionally, such information would also aid in regional scholars’ decision-making about target venues to publish their research. This information also can be useful to assess their academic levels by comparing their performance with other scholars in the same field and similar regions.

Expressly, when compared to other research fields, regional characteristics could play more substantial roles in ‘language and linguistics’ research. Because language is a core means of communication in a country and given that it further identifies the culture and spirit of a country (Boldyrev and Dubrovskaya, 2016; Tektigul et al., 2022), ‘language and linguistics’ research conducted in a specific country is likely to focus on its own languages and be highly dependent on its own socio–cultural characteristics. Thus, one can surmise that ‘language and linguistics’ research could perform differently depending on the country. However, despite the myriad bibliometric studies about ‘language and linguistics’ research, the foci were often limited to a specific sub-topic. The dearth of relevant literature means that we are ill-informed about the regional trends in ‘language and linguistics’ research.

Asian countries, especially, are linguistically different from countries on other continents. In fact, the languages of most Asian countries are linguistically distant from the Indo-European language family (Lewis et al., 2009; Nakagawa and Sugasawa, 2022), to which the languages, including English, of most countries on other continents belong. Furthermore, the majority of Asian countries have unique official and native languages, and their socio-cultural characteristics are also heterogeneous (Chang, 2022; Tsui and Tollefson, 2017, pp. 1–21). The current study, therefore, seeks to analyze research trends of ‘language and linguistics’ research in Asian countries over the last two decades. Specifically, considering the linguistic diversity among Asian countries, this study focuses on how geographically diverse ‘language and linguistics’ research has been, ranging from considering a country’s productivity level, authorship, and collaboration patterns to top keywords and research impact.

According to the literature review elaborated on in the section “Related literature”, in tandem with the long history of the field, a sizable number of studies has already conducted bibliometric analyses of ‘language and linguistics’ research. However, their foci are mainly on partial topics. As a few exceptions, some studies did try to identify the overall trends of the ‘language and linguistics’ research. However, the few studies that did analyze the trends at the regional level (in Asian countries) relied on too limited samples to illustrate the research trends effectively.

For instance, Barrot (2017) and Lei and Liao (2017) each examine ‘language and linguistics’ research at the Asian regional level. Lei and Liao (2017) analyzed research trends in four Chinse-speaking regions—China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. Based on their sample of 1381 articles and book reviews published between 2003 and 2012 in these regions, the analyses centered on productivity, research impact, and the journals in which articles from these regions were published most often. In a similar vein, Barrot (2017) conducted a bibliometric analysis of ‘language and linguistics’ research published in Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Viet Nam. The study sampled 2704 articles published by these countries from 1996 to 2015 and analyzed the research’s geographic distribution from the perspective of productivity, citation counts, and h-index. The collaboration patterns and the most academically advanced universities in the regions were also analyzed. Nonetheless, as the current study’s results reflect in Figs. 1 and 2, the contribution made by these Southeast Asian countries was relatively small when considered among 41 Asian countries. Besides, Lei and Liao (2017) were limited to four Chinese-speaking countries. Thus, by including 30,515 articles from 13 of the most prolific Asian countries (in terms of research output), this study seeks to provide a good understanding of how ‘language and linguistics’ research has been executed in Asia. The current study also expanded the analytical foci, compared to these other studies; the current study executed bibliometric analyses comprehensively from the perspectives of not only productivity and research impact, but also authorship and collaboration patterns and research topics.

To accomplish its purpose, the current study examined the research output of 13 countries—China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, Japan, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Turkey—which are linguistically diverse. Although Hong Kong, India, and Singapore have English as an official national language (Chang, 2022), the others have different official and native languages. Even in the aforementioned three countries, other languages are widely used co-officially and regionally; for example, Hong Kong now uses Mandarin as a co-official language alongside English, and Cantonese is widely used as a regional language.

Keeping Asia’s linguistic diversity in mind, one may understandably surmise that, on the one hand, these 13 countries could have thoroughly investigated their own languages and sociolinguistic cultures. As such, their disparate ‘language and linguistics’ research trends may differ significantly to each other. On the other hand, given the increasing importance of globalization (Nederhof, 2011), research on regional languages could attract relatively little interest. Rather, research about the lingua franca, English, could garner much more attention. Some studies (Chinchilla-Rodríguez et al., 2015; Fischer, 2003; Tektigul et al., 2022) also suggested that articles written in English and published in international journals do not take up regional matters as research topics, even though the studies were either based on non-Asian regions (i.e. European countries) or on old sample data.

As the relative dearth of relevant studies attests, little is known about the trends in Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research. Based on the sample data of an extensive scale comprised of research published in the last two decades, the current study tries to identify various bibliometric patterns of ‘language and linguistics’ research at the Asian regional level. Moreover, this study verifies whether regional characteristics have indeed shaped such research differently in Asian countries. The present study is designed to contribute to the existing literature by answering a variety of questions like the following: What is the geographic distribution of ‘linguistics and language’ research in Asia, and how much has each country contributed to the development of this research? How did Asian ‘linguistics and language’ scholars conduct their research, from the perspectives of authorship and collaboration? Which topics did they concentrate on? Finally, what is the scope and intensity of Asian countries’ research impact in the field?

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. In the section titled “Related literature”, existing bibliometric studies on ‘language and linguistics’ are summarized. Next, the sample dataset is described in “Data collection”; specifically, the reasoning behind choosing our 13 target countries, the sample data source, and the data’s sampling tactics. The main findings of this study are then described in sections “Research productivity” through “Scholarly impact of Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research” from different bibliometric perspectives. In particular, productivity and the patterns of authorship and collaborations are analyzed in sections “Research productivity” and “Authorship and collaboration patterns”, respectively. As for the analyses of top keywords, these are elaborated on in the section “Hot topics in Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research and topical changes”. In the section “Scholarly impact of Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research”, the scope and strength of the impact achieved by such research are presented. Concluding remarks and charting out possible future directions are given in the “Conclusion and discussion” section.

Related literature

Several studies executed bibliometric analyses to elucidate the trends of ‘language and linguistics’ research. Nevertheless, much has been said about specific trending topics. The examples include ‘children’s language (Guo, 2022),’ ‘computational linguistics (Radev et al., 2016),’ ‘discourse analysis (Wang et al., 2022),’ ‘English Language Teaching (ELT) (Barrot et al., 2022; Ngoc and Barrot, 2022),’ ‘language education for children (Yilmaz et al., 2022),’ ‘language evolution (Bergmann and Dale, 2016),’ ‘linguistic landscape (Peng et al., 2022),’ ‘natural language processing (Chen et al., 2018),’ ‘second language acquisition (Zhang, 2020),’ ‘second language writing (Arik and Arik, 2017),’ and ‘vocabulary acquisition (Meara, 2014)’.

Given the unprecedented interest in ‘computerized language analysis’ techniques and the practice of constantly augmenting interdisciplinary collaborations between ‘linguistics’ and ‘computer science’, several bibliometric analyses have been conducted on the relevant topics (Lei and Liao, 2017). These subjects include ‘chatbots and conversational agents (Io and Lee, 2017),’ ‘computational linguistics (Radev et al., 2016),’ ‘natural language processing (Chen et al., 2018),’ ‘sentiment analysis (Keramatfar and Amirkhani, 2019),’ ‘text mining in medical articles (Hao et al., 2018),’ and ‘topic modeling (Li and Lei, 2021)’. For instance, to assess the development of topic modeling research, Li and Lei (2021) analyzed approximately 1200 articles (2000–2017) regarding productivity, research impact, authorship pattern, geographic reach, and publication venues.

Guo (2022) investigated the research trends of ‘children’s language’ published in the past century (1900–2021). The productivity, main publication venues, geographical and institutional distributions, popular keywords, and research impact were analyzed. In particular, the study was based on a large-scale sample (48,453 articles indexed in WoS) and executed comprehensive bibliometric analyses. However, the outcomes were associated only with ‘children’s language’. As another extensive study, Radev et al. (2016) focused on the research trends of ‘computational linguistics’ and ‘natural language processing’. The study evaluated the 11,749 articles archived in the ACL Anthology (a digital repository) and did so—mainly from the co-citation and co-authorship network perspectives. Although some of the samples included the articles of a prominent linguistics journal (Computational Linguistics), most were from conference proceedings and more closely related to ‘computer science’ than ‘linguistics’. What is more, the geographic distributions were excluded from the analyses.

Another stream of research is concerned with how ‘language and linguistics’ research has been carried out in specific regions. For instance, Ngoc and Barrot (2022) conducts a bibliometric study concentrated on ‘English Language Teaching (ELT)’, a popular topic in ‘language and linguistics’ research. Unlike other studies covering a specific topic without any regional boundaries, the study focused on how ELT-related research has been conducted in ten Southeast Asian countries (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Viet Nam). Similarly, Mohsen (2021) and Barrot et al. (2022) investigated how one topic of ‘language and linguistics’ research has been administered at a country level. In particular, the former study addressed the ‘applied linguistics’ research in Saudi Arabia in the past decade (2011–2020); the later executed a bibliometric study about ELT in the Philippines and is based on doctoral dissertations and master’s theses. As such, these regional studies were limited to only a few countries or to countries that were relatively inactive in terms of research (see section “Geographic distribution of ‘language and linguistics’ research in Asian countries”). Nor did the bibliometric analyses compare research trends across several countries, as the current study has intended.

Nederhof (2011) examined the bibliometric perspective of ‘language and linguistics’ research and ‘literature’ research in The Netherlands. Specifically, the study divided the sampled studies into two groups depending on their target audiences, domestic or international. Then, for each group, which languages were studied and in which languages each was written formed the basis of the study’s evaluation. However, the study was comprised of old sample data, namely, publications from 1982 to 1991. Moreover, the sample contained a large portion of non-academic publications written for the public. As such, it is hard to apply the results from the bibliometric analyses of academic articles, as the current study does.

As such, despite copious studies that performed bibliometric analyses on ‘language and linguistics’ research, relatively scant research has been carried out on the research in Asian countries and regional characteristics. By filling in this critical gap in the academic literature, the current study contributes to the existing body of research by studying the ‘language and linguistics’ research of 13 Asian countries, as well as various bibliometric characteristics.

Data collection

For the analyses of Asian ‘language and linguistic’ research, 13 countries—China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, Japan, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Turkey—whose investment in R&D and academic productivity in ‘language and linguistics’ research has been considerable served the national context of this study. Meo et al. (2013) investigated the correlations among 40 Asian countries’ economic scales and their research outcomes for the last 20 years. The study found that the economic growth of a country, specified in terms of gross domestic product (GDP), was not significantly associated with the productivity rate and impact of their research outcomes. That is, richer countries were not necessarily academically more advanced than poorer ones. Instead, the ratios of how much each country invested in R&DFootnote 1 relative to their GDP were significantly associated with the country’s research productivity (r = 0.48) and research impact (r = 0.43). The more a country financed R&D, the more publications with higher impact produced. Such a significant association between R&D investment and research outcomes also corroborated the findings of other studies (Moed Dr and Halevi Dr, 2014; Nguyen and Pham, 2011). Therefore, with the purpose of analyzing research trends in ‘language and linguistics’ in academically advanced Asian countries, the current study first selected 11 countries whose R&D spending exceeded 0.5% of their GDP. However, despite sizable R&D investment, Qatar, which produced relatively few publications in ‘language and linguistics’, was excluded. Instead, by accounting for Taiwan’s significant academic publications in the field, despite the unknown ratio of R&D spending (Huang and Chang, 2011; Serenko et al., 2010), Taiwan was added. Moreover, in spite of their marginal R&D spending, due to rapid productivity growth in recent years (illustrated in the section “Geographic distribution of ‘language and linguistics’ research in Asian countries”), Indonesia and Saudi Arabia were also included.

To sample publications in the field published in these 13 countries, this study adopted the sampling strategy of Barrot (2017); the current study applied the following sampling methods to Elsevier’s Scopus as a source to collect our target Asian ‘language and linguistics’ studies. First, in the “Advanced Search” field on the Scopus, the following terms were entered: AFFILCOUNTRY(country) AND ALL(language and linguistics). AFFILCOUNTRY means searching all articles for which at least one author was affiliated in the corresponding country. To exclude results not relevant to ‘language and linguistics’, the search results were restricted to the ‘Social Sciences’ and the ‘Arts and Humanities’ subject areas in Scopus (Georgas and Cullars, 2005). Regarding publication outlets, this study concentrated on only journal articles (Barrot, 2017). This is because, for the performance evaluation and promotion of researchers in the Humanities and Social Sciences, universities and research institutions have recently placed more weight on journal articles (Nederhof, 2006; Sabharwal, 2013).

To evaluate recent trends comprehensively, the inclusive years for defining our sample articles were 2000 to 2021. Especially for journals that were not continuously indexed in the sources within the past 22 years, the articles published during the period when each journal was indexed in Scopus were only collected to sample quality articles. For instance, ‘journal of pragmatics’ began to be indexed by Scopus in 1977 and was never discontinued until 2021. Thus, all ‘language and linguistics’-related articles of the journal from 2000 to 2021 were collected. Meanwhile, ‘computer assisted language learning’ journal has been indexed in Scopus since 1990. However, the journal was discontinued in 1997 and reentered into the Scopus database in 2004. Thus, for ‘computer assisted language learning’ journal, a set of articles published between 2004 and 2021 was collected.

Finally, among sample articles, the ones published in the journals classified as ‘predatory’Footnote 2 were also removed, since some of the 13 countries included in this study have allegedly published counterfeit journals (Beall, 2012). Even though there are ongoing efforts to improve Beall’s approach to define ‘predatory journals’ (Krawczyk and Kulczycki, 2021), this study decided to exclude articles with a potential problem. While the initial set of target articles contained 32,379 articles from 2380 different journals, through this process, 1864 articles published in 31 predatory journals were identified and excluded. Therefore, the final set of target articles for the current study was comprised of 30,515 articles from 2349 journals.

Once the target articles were collected, citing articles that referenced the target articles were collected using Scopus. Since both WoS and Scopus have been serving as major sources of bibliometric data for journal articles, coverage of these two sources has been empirically tested at length in the literature (Aghaei Chadegani et al., 2013; Martín-Martín et al., 2018; Mongeon and Paul-Hus, 2016; Norris and Oppenheim, 2007). These existing literatures together suggested a higher rate of journal and article coverage in Scopus than in WoS. In the Social Sciences and the Humanities, especially, where ‘language and linguistics’ are strongly related, Scopus covered almost twice the number of journals than WoS. For articles published by Asian countries, Scopus has higher coverage as well (Martín-Martín et al., 2018; Mongeon and Paul-Hus, 2016). Furthermore, in terms of recall and citation count, Scopus surpassed not only WoS, but also Google Scholar, the latter of which is another major source of bibliometric data (Norris and Oppenheim, 2007). Thus, with the aim of measuring the scholarly impact of Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research more comprehensively, this study chose Scopus as its source of citation information.

For analyzing research impact, the current study separately sampled citing articles from Scopus to secure at least five years’ worth of data to cite the target articles from the time of the data collection, February 2022. To date, for the Social Sciences and Humanities, there is no universally accepted citation window. However, five years is a widely-used citation window in several disciplines (Campanario, 2011; Mingers and Leydesdorff, 2015). Because it was impossible to collect the citing articles to the fullest level (i.e., up to five years) for those published since 2016Footnote 3, the current study collected the citations for only target articles published from 2000 to 2015.

For the target and citing articles, using Scopus API, each article’s detailed information was collected. Such information includes the title, abstract, journal title and ISBN, publication year, number of pages, author keywords, and so on. To determine the authorship patterns, author information including the identifiers assigned by Scopus, names and affiliations, and their respective countriesFootnote 4 were separately collected.

For the remainder of this study, by referring to Shen et al. (2018), a target article’s country was determined by the first author’s affiliation. When the first author’s affiliated country was not in Asia, the corresponding authors’ countries were counted. Given that the authorship role (i.e., corresponding authorship) was not provided by the Scopus API, this information was manually collected in Scopus. If neither the first author nor the corresponding ones were from Asian countries, the country of the first Asian author in the byline was used. That is, even in a situation in which the main authors were not from Asian countries, once any author in the byline did come from Asia, the current study included it as a target article. In addition, when an author was affiliated with more than one institution, the institution located in an Asian region was considered first.

Research productivity

Geographic distribution of ‘language and linguistics’ research in Asian countries

Before delving into the specific details of the productivity of ‘language and linguistics’ research in our 13 target countries, this study first inquired into the contributing portions of these countries’ articles about the field, compared to articles originating from other Asian countries. This was done to examine to what degree the research of these 13 countries is representative of Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research overall. To that end, journal articles about ‘language and linguistics’ published by the other 28 Asian countriesFootnote 5 were searched for in the same way as our target articles were. That is, using Scopus’ detailed search, articles related to the field published by the other 28 countries from 2000 to 2021 were collected, after excluding predatory journals. Figures 1 and 2 detail the comparison of the ‘language and linguistics’ publications by country.

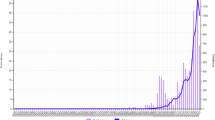

First, Fig. 1 depicts just how different was the total number of journal articles published by each country; in the figure sorted by each country’s total publication number, the 13 red-colored lines indicate the publication rates of our target 13 countries. The other 28 blue-colored lines show the other 28 countries’ rates. From 2000 to 2021, 41 Asian countries published 35,830 articles in total, and the 13 countries that constitute our interest published 85.2% of all the articles (n = 30,515). Furthermore, these 13 countries published at least 900 articles over the last two decades, while none of the other 28 countries published more than the individual 13 countries.

Fig. 2 also details how the total number of articles published by the two sets of countries (i.e., the 13 countries vs. the other 28 countries) has changed from 2000 to 2021. Specifically, Fig. 2 presents the contribution made by each set relative to the entire Asian countries’ annual contributions. In 2000, the commencing year of this study’s sample data, all 41 Asian countries published a total of 212 articles collectively. What is more, that number increased to 6290 articles in 2021, the sample’s final year. The scale of the 2021 publications is the result of a 16.9% annual growth in productivity. That is, except the two years (2002 and 2004) for which there was a decrease, the number of all the Asian ‘language and linguistics’ publications has grown about 17% each year on average. In the context of this remarkable growth, as already noted, our target countries contributed more than 80% of the overall output, without exception. This means the other 28 countries, taken altogether, were never able to reach a contribution rate of 20%. Notably, although the other 28 countries’ contribution level has recently increased, the target 13 countries’ research has truly dominated Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research. The remaining sections of this study, therefore, concentrate mainly on the bibliometric properties of these 13 countries’ research; the objective is to comprehend the trends of Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research.

The research productivity of the 13 target countries

Bearing in mind that our target 13 countries dominated Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research, the next immediate question is: What are the differences in research productivity among the 13 countries? Table 1 illustrates the results, which are key to answering that question. Among 13 countries, the most active countries were China, Iran, and Japan, followed by Hong Kong, Taiwan, and South Korea. Moreover, the annual growth rates of productivity indicate that Indonesia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Malaysia momentarily demonstrated the greatest growth rates. On average, Indonesia’s ‘language and linguistics’ research has grown 73% every year, and Iran’s by 54% annually. Saudi Arabia and Malaysia also demonstrated about a 40% growth rate each year (i.e., 43% for Saudi Arabia and 39% for Malaysia). However, notably, these countries’ productivity levels also widely fluctuated over the last 22 years; the standard deviation values of the growth rates were around 100%, especially, Indonesia’s research had a value of 287%. Meanwhile, regarding the standard deviations, the annual growth rates for Japanese, Hong Kong, and Israeli research had been the most stable. Taking into account the substantial productivity since 2000, as well as steady growth, Japan and Hong Kong consistently held the lead for Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research. As the most prolific country in ‘language and linguistics’, China showed consistent participation (yielded a 29.9% average annual growth rate and 30% of the standard deviation of growth) in the field’s research. However, China became the most prolific Asian country in ‘language and linguistics’ research in 2010; they have taken over the position of Japan, which had been the most prolific country before 2010.

The next analysis was intended to investigate publication venues in which Asian ‘language and linguistics’ researchers were the most active in publishing their articles. Together, they published articles in 2349 different journals, and Table 2 shows the top 20 journals. As the publishers indicated, both the major international and regional journals are mixed up together. Whereas several countries published articles evenly in international journals, a few tended to dominate regional journals. Particularly, in some regional journals, more than 95% of the articles originate from one country (i.e., Iran for Language Related Research, Japan for English Linguistics, and South Korea for Communication Sciences and Disorders).

Next, to ascertain the dissemination of their research findings, the question pursued was: How many diverse journals had each country published their articles in? In addition, between international journals and regional journals, in which type did each country published more articles? To answer these questions, by using WoS’s journal coverage and the time periods of that coverage, 30,515 articles in 2349 journals were divided into either ‘international’ or ‘regional’ subsets. Specifically, it was verified whether each article was published in a journal indexed in WoS core databases, including the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-E), or the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI). If so, the article was then classified as an article of an ‘international journal’. Those published in journals not indexed in SSCI, SCI-E, or A&HCI were classified as articles of a ‘regional journal’. Even for journals indexed later in WoS core databases, articles published in the same journals while the journals were not indexed in the core databases were classified as those of a ‘regional journal’.

Figures 3 and 4 display the results, which answered the above questions. Fig. 3 illustrated how differently each country published its articles between international and regional journals. For the entire set of 30,515 publications among these 13 countries, 46.0% (n = 14,045) of all articles were published in international journals. China, Hong Kong, Israel, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan were the ones who concentrated more on international journals when publishing articles related to ‘language and linguistics’. In particular, the relative difference between the two journal types showed that more than half of the articles published by these countries were in international journals. Whereas the majority (over 70%) of the Indonesian, Iranian, Malaysian, and Saudi Arabian articles were published in regional journals.

By considering the results of both Table 1 and Fig. 3 together, on the one hand, we can deduce that the remarkable growth rate (in terms of research productivity) for Indonesia, Iran, Malaysia, and Saudi Arabia can be ascribed largely to regional publications. On the other hand, the countries, such as China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, that had been consistently leading in Asian ‘language and linguistics’ studies for the past two decades had been also actively publishing articles in international journals. Thus, to gain a better understanding about how international and regional publications changed by country, Fig. 4 depicts the yearly changes of the 13 countries’ productivity, separately in international and regional journals. The patterns illustrated in Fig. 4 verified the journal types each country had been concentrating on over the years, and it also corroborated the above explanations. While Japanese research had consistently grown in both international and regional journal publications over the years, most of the productivity increase in China since the 2010s can be ascribed to publishing in international journals. Moreover, the changing patterns observed for Hong Kong, Israeli, Singaporean, and Taiwanese research productivity levels among international journals were almost perfectly synchronized with the changes in the countries’ overall productivity. This was also the case for Indonesian, Iranian, Malaysian, and Saudi Arabian productivity changes in regional journals. Furthermore, the overall productivity of Indonesia, Iran, Malaysia, and Saudi Arabia had grown intensely in recent years; in fact, its recent productivity almost nearly accounts for the corresponding countries’ entire scale of research for the past 22 years.

Authorship and collaboration patterns

The above analyses demonstrated that each country had conducted their ‘language and linguistics’ research at varying paces and had targeted different publication venues (international vs. regional journals). The questions then become: How did the researchers of these 13 target countries participate differently in the research? With which countries did they often collaborate? To address these questions, this sub-section thus aims to analyze both authorship and collaboration patterns. First, regarding some critical questions about authorship (e.g., How many authors have participated in publishing Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research?; How much of the overall research has been written by collaborations?), Fig. 5a illustrates authorship distributions. As for Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research, 39,929 distinct scholars published 30,515 articles, one of whom had authored 1.8 articles on average (s = 2.4). Additionally, each article was authored by 2.3 researchers (s = 1.7) on average.

Among 30,515 articles, 35.7% (n = 10,904) were written by sole authorship, and 31.1% (n = 9501) and 17.3% (n = 5287) were written by two and three authors, respectively. This means 84.2% of all the articles (n = 25,692) were written by three or fewer authors. However, a large volume of literature (Ahn et al., 2014; Henriksen, 2016; Hu et al., 2020; Wagner et al., 2017) substantiated that, in the current academic culture in which performative culture prevails, as a way to increase productivity and visibility, collaborations have increased across both disciplines and nations. To determine whether this kind of collaborative culture has also been strengthened in Asian ‘language and linguistics’, the yearly changes of authorship per article were examined; the results are presented in Fig. 5b. Specifically, Fig. 5b shows the relational percentage of each type of authorship for the entire set of publications for each corresponding year. It also indicates distinctive pattern changes as the years progress: the reduction of sole authorship and the increase of co-authorship. While sole authorship consistently occupied 55 to 60% of each year’s publications in the early 2000s, the ratios have shrunk to around 30% in the most recent years. Conversely, the ratio of multi-authorship articles increased from around 40 to 45% in the early 2000s to approximately 70% in the 2020s. Particularly, two-person authorship recently became the most common in Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research.

When this collaborative culture increased in the field, had Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research been actively engaged in international or domestic collaborations? Regarding international collaborations, which country was more frequently collaborated with? Among several forms (e.g., inter-lab, inter-organizational, cross-sectoral), international collaboration is considered as the most heterogenetic form; what is more, such heterogeneity is known to produce many benefits, such as enhancing international visibility and productivity, as well as increasing access to expertise and resources that are unavailable domestically (Hu et al., 2020).

Among the 19,611 co-authored articles, 64.1% (n = 12,574) were produced by domestic collaborations. That is, 35.9% (n = 7037) was published by international collaborations. Notably, the majority of international collaborations occurred between two nations (n = 2714). Fig. 6 displays the different collaboration patterns of the target countries. In particular, the data verified the predominance of sole authorship in Hong Kong, Japan, and Taiwan, and, interestingly, these countries were among the most prolific in the field. Meanwhile, three countries, Indonesia, Iran, and Malaysia where exhibited a much higher tendency to publish in regional journals, showed many more (and more frequent) domestic collaborations than international collaborations. Countries like China, Hong Kong, and Singapore, which had actively published articles in international journals, displayed relatively high ratios of international collaborations. Whereas sole authorship was still the most common in Hong Kong and Japan, at least regarding collaborative publications, international collaborations were significantly more frequent than domestic collaborations.

However, Israel, South Korea, and Taiwan exhibited exceptional patterns; it seems that, in these countries where each had published more articles in international journals than regional journals, domestic collaborations were considered enough to publish articles in international journals. These results aligned with the findings of an existing study (Hu et al., 2020), which suggested that these countries have a sufficient number of highly-competent researchers domestically. Thus, to publish in international journals, international collaborations were not a prerequisite anymore in those countries. Saudi Arabian research also showed a unique authorship pattern: the country’s research yielded the highest ratio of sole authorship among the 13 countries. What is more, for the articles produced by collaborations, international collaborations were more common than domestic collaborations. However, Saudi Arabia was one of the countries that published many more articles in regional journals (i.e., 73.8% of overall publications). Therefore, in contrast to the patterns of Israeli, South Korean, and Taiwanese research, in order to publish articles in domestic journals, Saudi Arabian scholars often sought international collaborations to increase their productivity.

Lastly, to comprehend the international collaboration patterns, Fig. 7 renders the collaboration landscape of 7037 internationally co-authored articles. Fig. 7 was constructed based on an ego-centric collaboration network of the 13 target countries; the nodes represent the 13 countries along with their collaborating countries. The different node sizes reflect the country’s ‘Degree’, which indicates the larger the node, the more different countries each corresponding country had collaborated with. The thickness of the line between countries represents the frequency of their collaborations. Briefly speaking, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, Germany, and The Netherlands all frequently collaborated with Asian countries to produce ‘language and linguistics’ research. Additionally, international collaborations among the 13 target countries were also active; China, Hong Kong, and Iran were the top three with which Asian countries often collaborated.

Fig. 7 also depicts three sub-groups of relatively well-connected countries, discovered by the modularity-based community detection technique (Newman, 2006). The technique is used to divide a network into sub-groups by ensuring internal cohesion within each sub-group and external separations between sub-groups as much as possible (Vacca, 2020). The first sub-group consists of the largest number of countries and most European countries, including the United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, Spain, and France, belong to this group. This sub-group also includes a few African countries and Southern American countries. Among the 13 sample countries, India, Israel, and Turkey belong to this group. This means that Indian, Israeli, and Turkish researchers collaborated relatively often with European researchers but less so with other countries in the other two sub-groups. As a different form of ‘degree’ weighted by the frequency of collaborations and signaling collaboration intensity (Ceballos et al., 2017), the ‘average weighted degree’ of this sub-group is 532.6.

Next, the second sub-group of countries consists of the research-wise most prolific Asian countries including China, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. Iran is also in this group. The United States, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and some South Asian countries likewise belong to this group. The average weighted degree of this group is 1972.7. The relatively larger average weighted degree indicates that the countries in this sub-group were more likely to collaborate with each other, and to do so more often. Lastly, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Saudi Arabia constitute the last and third sub-group; furthermore, their collaborators, such as Iraq, Oman, Pakistan, Thailand, United Arab Emirates, belong to this group. The average weighted degree of the third group is 280.0. Compared with the other two sub-groups, this last sub-group infrequently collaborated with each other.

To grasp the international collaboration patterns more clearly, Table 3 summarizes the full breadth of international collaborations for the 13 countries. ‘Betweenness Centrality’ indicates how often each country filled the information brokerage role in the collaboration network. Moreover, ‘Betweenness Centrality’ gauges how many times a given country was located in the shortest path of another collaboration relationship and represents the magnitude to which the country can control the information flow in its own collaboration network. The higher the centrality, the more power that country had over its information flow (Lee, 2020). Table 3 also depicted the number of internationally co-authored articles and the most frequent collaborating countries. China and Japan published the largest number of internationally co-authored articles and collaborated with the most diverse range of countries. Given this activity, the ‘Betweenness Centrality’ values of the two countries were also relatively higher. The ‘Betweenness Centrality’ of India, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey were also high due to their active collaborations with diverse countries, although the number of internationally co-authored articles was relatively low.

Hot topics in Asian ‘Language and linguistics’ research and topical changes

Language is a critical means of expressing a country’s culture, national spirit, and national values (Sapir, 1929; Saussure, 1916; Tektigul et al., 2022). Each of our 13 target countries has its own language; even for those whose official language is English, other co-official and regional languages exist. Therefore, one can postulate that ‘language and linguistics’ studies from these 13 countries would address topics largely about the language(s) used in their own countries. Meanwhile, owing to the on-going globalization process (Fischer, 2003; Tektigul et al., 2022), topics about educating and acquiring a lingua franca (English) would be inextricably intertwined with Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research. To understand the key research topics among these nations in detail, this section analyzed the keywords featured in the target articles.

Beforehand, the current study found that Scopus provided author-defined keywords for only 27,214 of the 30,515 articles. For the remaining 3301, for which the keywords were unavailable in Scopus, the keywords were extracted using KeyBERT (Giarelis et al., 2021). KeyBERT is a keyphrase extraction method that relies on a deep learning-based BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) algorithm (Devlin et al., 2019), which is widely used in document summarization. Because KeyBERT is based on BERT’s pre-trained model, it is both efficient and can create N-gram keywords (Arhab et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2022), like the author-defined keywords of the target articles. For each of the 3301 articles, the KeyBERT method was applied to the title and abstract and, among the keywords derived by the KeyBERT, the top five were selected depending on significance scores. Excluding 157 articles, for which the titles and abstracts were either unavailable or too short to generate keywords, next, based on the keywords of 30,358 articles, the current study performed an analysis of research topics in Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research.

Table 4 lists the top 30 keywords, along with the countries that used the corresponding keywords most often, as well as the most frequent co-appearing keywords. According to the data, some Asian languages (‘Chinese,’ ‘Hebrew,’ ‘Hong Kong,’ ‘Japanese,’ ‘Cantonese’) and teaching and learning English (‘EFL,’ ‘EFL learners,’ ‘English’) were the most frequently explored topics. In particular, whereas each Asian language was studied mainly in its respective country, research about English was popular across all Asian countries. Moreover, topics about ‘discourse’ (i.e., ‘conversation analysis,’ ‘critical discourse analysis,’ ‘discourse analysis’) and ‘language education’ (i.e., ‘higher education,’ ‘language learning,’ ‘second language acquisition’) were likewise prominent. Given the increasing interest in computerized language analyses, ‘sentiment analysis’ was another hot topic.

The top keywords, listed in Table 4, reflect the most popular topics in Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research for the last 22 years. Nonetheless, it is hard to capture the details of each research topic; for instance, ‘whether each popular topic had been traditionally investigated or gained in popularity more intensely during a certain short period of time,’ ‘which topics were most frequently studied in each country,’ and ‘how topics of the Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research had changed over the years’. Therefore, Tables 5 and 6 were also added to examine how the hot topics have changed between 2000 and 2021, and which were the most popular in each of the 13 countries.

Table 5 displays the top 20 keywords for every three years; for articles published every three years, the most popular keywords were listed. In Table 5, discernible patterns emerged around 2010; before 2010, various Asian languages (‘Chinese,’ ‘Cantonese,’ ‘Hebrew,’ ‘Japanese,’ ‘Korean,’ ‘Mandarin Chinese,’ ‘Turkish’) were explored most often, but from 2010 onward, the interest in these topics seemed to wane. In the most recent set of three years, except for ‘Chinese’, none of the Asian languages were included among the top keywords. Similarly, the main components of linguistics research (‘morphology,’ ‘phonology,’ ‘pragmatics,’ ‘syntax’) also received intensive scholarly attention in the early 2000s. However, their popularity seemed to dwindle as well.

Nonetheless, owing to the popularity of learning a lingua franca (English), a means of coping with internationalization worldwide, from 2010 onward, topics related to ‘English’ were of burgeoning interest among Asian researchers. According to the co-appearing keywords, ‘EFL,’ ‘EFL learners,’ ‘EFL teaching’, ‘ESL,’ ‘language learning’ ‘listening comprehension,’ ‘motivation,’ ‘reading comprehension,’ and ‘translation’ were frequently associated with ‘English’ in general. Similar to the patterns of ‘English’-related topics, ‘discourse’-related topics have earned intensive and constant interest since 2010. As such, the co-appearing keywords highly associated with ‘discourse,’ topics covering ‘classroom discourse,’ ‘corpus linguistics,’ ‘critical discourse analysis,’ ‘discourse analysis,’ ‘discourse markers,’ ‘ideology,’ ‘metadiscourse,’ and ‘political discourse’ were regularly studied.

However, as the overall productivity of Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research has drastically increased, more diverse topics may have appeared; it is yet unknown whether interest in Asian languages and major components of linguistics did wane over the years and if interest in ‘English’ and ‘discourse’ indeed had grown. Therefore, a separate analysis was performed, as shown in Fig. 9. For this analysis, the top 30 keywords for every three years (illustrated in Table 5) were expanded to the top 100 keywords for every three-year period. Next, the top keywords of four groups of topics, (1) Asian language-related,Footnote 6 (2) major components of linguistics,Footnote 7 (3) English-related,Footnote 8 and (4) ‘discourse’-relatedFootnote 9—were extracted from the top 100 keywords. Using the top keywords of the four topic groups, the longitudinal changes of these four groups were then analyzed.

As Fig. 8 depicts, Asian languages were well-studied throughout the 22-year period. Even though the keywords pertaining to ‘English’ had been restricted as much as possible for this analysis, the popularity of English-related research has nonetheless surged since 2014. In addition, the popularity of ‘discourse’-related topics was steady for the same duration. The research about main linguistic components had been consistently published; however, due to the increasing volume of Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research overall, the scholarly importance diminished relatively. Although they were excluded in the analysis depicted in Fig. 8, among the top 30 keywords in Table 4, ‘culture’-related topics were also consistently popular throughout the past 22 years. ‘Attitude,’ ‘gender,’ ‘identity,’ ‘ideology,’ and ‘translation’ were frequently co-appearing keywords alongside ‘culture.’ Notably, ‘grammaticalization’ and ‘academic writing’ were also hot topics.

The results of Table 6 demonstrated that the topics related to ‘English’ were explored often in each of the Asian countries, except India. Depending on the nation’s culture and its language-related policies, however, the highly-popular topics associated with ‘English’ differed by country. For instance, in nations in which the official language is English (i.e., Hong Kong and Singapore), ‘bilingualism,’ ‘language policy,’ ‘multilingualism,’ and particularly localized English, including ‘Hong Kong English,’ ‘Singapore English,’ ‘Singlish,’ and ‘colloquial Singapore English,’ were popular. Despite the current official language of Malaysia not being English—owing to its colonial history in which both Malay and English were the official national languages until the 1960s and then English’s importance to globalized communication afterward—topics about ‘English’, including ‘Malaysian English,’ ‘ESL,’ ‘EFL,’ ‘EFL learners,’ ‘language policy,’ and ‘second language acquisition’, were actively explored in Malaysia. Meanwhile, in the other countries for which English is not an official national language, these trending topics related to ‘English’ were prevalently studied: the education of ‘English’ including ‘EFL,’ ‘EFL learners,’ ‘English as a foreign language,’ ‘English language teaching,’ ‘listening comprehension,’ ‘reading comprehension,’ ‘second language,’ and ‘second language acquisition’.

Concurrently, research on a country’s national language(s) and dialects were chiefly conducted. The relevant topics encompassed ‘Cantonese,’ ‘Chinese,’ ‘Mandarin,’ ‘Mandarin Chinese,’ ‘Southern Min,’ and ‘Taiwanese Southern Min’ in Chinese-speaking countries (China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan); ‘Bengali,’ ‘Hindi,’ ‘Indian languages,’ and ‘Kannada,’ in India; ‘Indonesian’ in Indonesia; ‘Persian’ and ‘Persian language’ in Iran; ‘Arabic,’ ‘Hebrew,’ and ‘modern Hebrew,’ in Israel; ‘Japanese’ in Japan; ‘Malay’ in Malaysia; ‘Arabic’ in Saudi Arabia; ‘Korean’ in South Korea; and ‘Turkish’ in Turkey. In particular, the popularity of a certain language as a research topic seems to reflect the speaker population of the language in a country. In Israeli research, ‘Russian’ was one of the top 20 keywords, and it was also one of the frequently co-appearing keywords alongside ‘Hebrew’, owing to the significant population of Russian immigrants in Israel (Lerner, 2011).

The outcomes detailed in Tables 5 and 6 also indicate that, owing to the flourishing interest in computerized language analysis and the on-going development of relevant techniques, associated keywords, such as ‘computer-mediated communication,’ ‘deep learning,’ ‘information retrieval,’ ‘machine learning,’ ‘natural language processing,’ ‘opinion mining,’ ‘sentiment analysis,’ ‘social media,’ ‘speech recognition,’ ‘text mining,’ and ‘Twitter,’ began emerging as hot topics from the early 2000s onward and, especially in the most recent four years, interest has drastically increased. These topics were also trending in ‘China,’ ‘India,’ and ‘South Korea’. Particularly in Indian ‘language and linguistics’ research, out of the top ten keywords, eight pertained to computerized language analysis. Moreover, online language learning and teaching (‘E-learning,’ ‘interactive learning environment,’ ‘online learning’) has likewise grown in popularity since the Covid-19 outbreak.

Scholarly impact of Asian ‘Language and linguistics’ research

Considering the importance of citations in measuring the scope and strength of research impact, it is reasonable to investigate how the citation patterns of the 13 target countries vary. More specifically, this sub-section inquires into critical questions about research impact, including the following: ‘How much attention did each country’s research garner?’ and ‘What country paid the most attention to the research of individual Asian countries?’. As explained in the section “Data collection”, in order to measure properly the impact of articles published in different years, the current study used five-year citation windows. That is, for every target article, with the purpose of removing the effects of time for articles published in varying years, the citations earned only within five years since being published were collected. Moreover, because it was impossible to collect all the citations to the fullest level, recent articles published from 2016 to 2021 were excluded from the analyses; 11,329 articles published up until 2015 were thus accounted for in the analyses.

Fig. 9 shows the overall distribution of citation counts accrued by all 11,329 articles. Over the course of five years, 78.4% (n = 8880) was cited at least once as a reference and received 8.3 citations (s = 12.2) on average. That is, 2449 articles were never cited as a reference at all within the first five years after publication. As for the 8880 articles that had been used as a reference, 55.7% (n = 4947) were cited five times or fewer, and 75.9% (n = 6744) were cited ten times or fewer in that five years span. The overall distribution of citation counts indicated that, especially for Asian ‘language and linguistics’ articles, 19 or more citations were calculated as outliers; that is, the articles that earned either equal to or more than 19 citations were significantly and extraordinarily cited more often than the majority of these kind of articles.

Adhering to the purpose, which is to examine the citation patterns of 13 countries individually, Figures 10a and 10b, respectively, display the distributions of citations accrued by the countries and summaries of the citations per country. In Fig. 10a, particularly, the number at the top of each box is the value used to determine the distribution outliers. For instance, the Chinese articles cited more than 17 times, Hong Kong articles referenced more than 26 times, and Indian articles cited more than 20 times were outliers in that they were extremely well-cited, compared with the distributions for the majority of articles published by these same countries. The citations in the outlier group were omitted in Fig. 10a so as to observe clearly the international differences in the citation distributions among the 13 target countries.

The citations garnered by the articles of each country reflect different distribution patterns. Hong Kong, Israel, and Singapore have the widest and tallest distributions, while Indonesia, Iran, and Malaysia have narrow and shortest distributions. Coinciding with the patterns displayed in Fig. 10a, the summary of Fig. 10b indicated that Hong Kong, Israeli, and Singaporean articles received the highest number of citations per article on average (m = 7.9 [s = 9.8] for Hong Kong, m = 9.1 [s = 16.6] for Israel and m = 9.1 [s = 13.0] for Singapore). Articles from these countries also had the smallest ratios of non-cited articles; 12.7% of Hong Kong articles, 11.5% of Israeli articles, and just 11.2% of Singapore articles were never cited within the first five years of publication. However, more than 20% of the articles published by the remaining ten countries never received any citations at all. Meanwhile, the citations earned by articles from Indonesia, Iran, and Malaysia showed much room for improvement; they received relatively fewer citations (m = 2.1 [s = 3.7] for Indonesia, m = 2.7 [s = 4.6] for Iran, and m = 3.7 [s = 4.9] for Malaysia). Additionally, the ratios for non-cited articles were also relatively high (47.5% for Indonesia, 33.3% for Iran, and 24.7% for Malaysia).

Per the next analyses concerning the scope of impact, the characteristics of citing articles that referenced Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research were investigated. Specifically, self-citations and the dispersal of countries that had most often utilized Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research as references were examined. Existing studies (Aksnes, 2003; Costas et al., 2010) suggested several ways to count self-citations, ranging from author-level, coauthor-level, and institution-level to journal-level and to country-level. The current study counted the self-citations at the author- and country-levels. That is, when article A was cited by article B, which shared at least one author with article A, then it was deemed that an author-level self-citation had occurred.Footnote 10 When article A was cited by article C, which was written by an author(s) of the same country, even though there was no common author between article A and C, it was counted as a country-level self-citation. In particular, when the citing article (article C) was written by a researcher from the same country of the cited article (article A), then regardless of the author’s role (i.e., first, corresponding, or participating authorship), the current study considered the case as a country-level self-citation.

As for the 8880 Asian ‘language and linguistics’ articles that had received a citation within the first five years of their publication date, they were cited 73,688 times. Additionally, the author-level self-citation rate and the country-level self-citation rate were 18.8% (n = 13,853) and 13.3% (n = 9832), respectively. Specifically, 4747 articles were cited by other articles written by the same authors 13,853 times; 3939 articles were cited by other articles written by authors of the same countries 9832 times. The patterns illustrated in Fig. 11 demonstrate how many citations were earned overall by each country that were self-cited, either at the author- or country-level. The countries with the highest author-level self-citation ratios were India, Israel, and Malaysia; in fact, more than 20% of these countries’ articles were cited by the authors themselves. Meanwhile, the countries with the lowest author-level self-citation ratios were Iran, Turkey, and Taiwan. The countries with the highest country-level self-citations were Iran, Malaysia, and Indonesia. That is, the articles originating from these countries seemed to have had a significant impact domestically. Notably, however, according to Fig. 6, Indonesia, Iran, and Malaysia garnered the highest ratios of domestic collaborations among the 13 countries. Therefore, a further investigation into the patterns of domestic citations (e.g., how many domestic citations came from the same institutions or from previous collaborators) is needed—although this inquiry is beyond the scope of the current study.

Next, the remaining citation counts—excluding both author- and country-level self-citations—indicate the magnitude of international citations. In this sense, with the exception of 176 citations (of which the authors’ countries were unknown), 67.9% (n = 50,003) of all citations acquired by Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research was internationally cited. Among the 13 target countries, a comparison of the raw citation counts indicates that the research from Japan, China, Hong Kong, and Israel had a substantial international impact. However, these countries also maintained the highest research productivity among all 13 countries. Therefore, instead of the raw citations, based on the ratio of international citations to the overall number of each country, the research from Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Korea, and Turkey—then followed by Japan and Hong Kong—generated relatively more international impact.

To provide a more complete understanding of exactly how diverse and strong each country’s international impact was, Fig. 12 depicts the citation network of Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research, after excluding author- and country-level self-citations. Additionally, Table 7 shows each country’s total number of international citations, the average international citations per article, and the top five countries for the most often-cited the corresponding country’s publications. Fig. 12 presents the nodes corresponding to each of the target 13 countries, and the size of each node (i.e., each country) varies depending on the country’s ‘in-degree’. The larger the node, the higher number of diverse countries that took advantage of the node country’s articles as references. The thickness of the arrow coming into each node represents how many times the corresponding country was cited by the countries from which each arrow originated.

For instance, the United States was the top country where the most often cited the overall Asian ‘language and linguistics’ (n = 11,804). As such, Table 7 shows that, without exception, the articles from each one of the 13 countries were also cited the most by the United States. Specifically, the United States cited Japanese articles (n = 2321) most often, followed by Israeli (n = 1848), Hong Kong (n = 1655), and Chinese articles (n = 1486). At the continental level, North America was the one where Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research was the most cited (n = 14,045; 28.1% of overall international citations). Regarding international citations within the target 13 Asian countries, these also regularly occurred. Particularly, following North America, Eastern Asia was the area in which Asian research had the second most significant impact (n = 4487; 9.0%). China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Japan, specifically, also frequently cited the other Asian countries’ research. As for one of the Western Asian countries, Iranian research also often referenced other Asian articles. Among Asian countries, the research of those that share the same language, such as China, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan, had quite a discernible impact on each other. Japan, which was the most prolific in terms of ‘language and linguistics’ research along with China (see Table 1) and was often cited internationally, did not frequently take advantage of the other Asian countries’ articles as references. The United Kingdom (n = 4299), Australia (n = 2338), Canada (n = 2083), Spain (n = 2004), and Germany (n = 1875) also often cited Asian research. What is more, next to Northern America and Eastern Asia, the research originating from the 13 target countries also garnered many citations from both Northern Europe (n = 6137; 12.3%) and Western Europe (n = 4994; 10.0%).

Conclusions and discussion

This study carried out an in-depth analysis of research trends over the past two decades in Asian ‘language and linguistics’, focusing particularly on 13 target Asian countries. As a prerequisite for conducting this analysis, it was imperative to determine whether the research produced by the target 13 countries is truly a representative sample of Asian ‘language and languages’ research. Thus, this paper compared the research productivity of our 13 selected countries with 28 other Asian countries. The results demonstrated that our target countries had indeed dominated the entire field of Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research from 2000 to 2021. For the given period, 41 Asian countries published 35,830 articles, and the scale of the publications constituted an 17% annual growth in productivity. In particular, the target countries published 85% of all papers in Asia, and the scale of the research originating from 28 other Asian countries has never actually surpassed that of the individual 13 target countries for the past 20 years. Thus, the current study paid attention mainly to the 30,515 articles published by these 13 countries.

When considering the entirety of Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research, the most prolific nations were China, Iran, Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and South Korea. Notably, while Japanese and Hong Kong research had consistently led the field throughout the designated time period, Chinese research has been a rising star in the field since 2010. In addition, China, Hong Kong, and Israel were the most active in publishing articles in international journals, whereas Indonesia, Iran, and Malaysia concentrated on publishing articles in regional journals. To publish these articles, either sole authorship or the collaborations of small groups still dominated Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research. Specifically, even though the most common authorship type remained sole authorship for these two decades, by following the universal trend of increasing co-authorship alongside the demise of sole authorship, this collaborative culture has been consistently reinforced. In fact, multi-authorship, which represents 40 to 45% of the entirety of articles published in the early 2000s, increased to about 70% in the 2020s. The most common collaborators with Asian researchers were American, English, and Australian scholars. Furthermore, international collaborations among the 13 target countries occurred often as well.

To identify the reasons behind the frequent collaborations between Asian researchers with their European and American counterparts and the topical collaboration patterns, for each of the three groups of collaborators clustered by the modularity of the collaboration networks (see Section “Authorship and collaboration patterns”, especially Fig. 7), the most popular research topics in each group were computed. However, this study failed to find any noticeable differences in the most popular keywords among the groups; for both first (comprised mostly of European countries) and second collaboration groups (comprised mostly of American and Oceanian countries), ‘Chinses,’ ‘English,’ ‘Japanese,’ ‘bilingualism,’ and ‘language’ were commonly the most popular. Even though the third group, which included predominantly Southern or Western Asian countries, had a rather unique set of popular keywords (i.e., ‘Bangladesh,’ ‘Covid-19,’ ‘sentiment analysis,’ ‘higher education,’ and ‘EFL’), this set of countries was relatively inactive in ‘language and linguistics’ research, compared with other Asian countries. Thus, these puzzling and indiscerptible patterns among the three groups deserve to be addressed by further research, to figure out which topics Asian researchers had worked well with different countries, for instance, based on topic clustering or keyword network-based clustering.

In Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research, overall, various Asian languages, teaching and learning English, discourse, and the main components of linguistics were the most popular topics. Whereas interest in subjects related to ‘English’ have been surging since 2014, the other more traditional topics were investigated, covering the past two decades. Moreover, the interest in computerized language analysis and its associated techniques have intensely increased in recent years.

The last analysis concerned the research impact created by each of the 13 target countries. The results demonstrated that Hong Kong, Israel, and Singapore had published impactful articles. Furthermore, each of the 13 countries had a different scope of impact. While Indonesia, Iran, and Malaysia had a relatively high level of domestic impact, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Korea, and Turkey had a strong international impact. The overall influence of Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research was the greatest in the United States. Countries in Eastern Asia, such as China, Hong Kong, Japan, and Taiwan, also often cited the research of other Asian countries.

The findings of this study have opened up other possible avenues of research to pursue. While conducting our analyses on the top keywords of Asian ‘language and linguistics’, because the keywords of more than 20% of the target articles were derived by deep learning-based BERT algorithm, this study evaluated the keywords without further intervention in any way. However, associations among keywords that could be derived from machine-learning-based topic modeling could yield other valuable results. For instance, the outcomes of topic modeling might allow one to group together several countries that have researched similar topics. Additionally, collaborative relationships or citation connections among the sampled countries might inform new narratives. Another future direction that would be vital to expanding our field would be considering why the research impact of these 13 countries differed and, furthermore, what determines their impact within ‘language and linguistics’ research. Although a large body of literature has already presented bibliometric analyses on the Social Sciences and Humanities (Archambault et al., 2006; Bhardwaj, 2017; Bui Hoai et al., 2021; Sīle et al., 2018), wherein ‘language and linguistics’ research belongs, it has been scarcely studied just exactly how the research impact of ‘language and linguistics’ studies would be determined. The last analyses about impactful topics have also shed light on another possible research direction. The results of Tables 5–7 substantiated that the research interest in computerized language analyses has intensified among the Asian ‘language and linguistics’ community. Conversely, the findings of ‘language and linguistics’ research are becoming critical ingredients in cutting-edge Computer Science technologies (Clark et al., 2012; Haddi et al., 2013; Rodriguez et al., 2012). However, due to insufficient time for collecting the citation information of relevant articles, it was premature for the current study to measure the impact of these topics brought about by Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research. Therefore, it will be an imperative academic path to take, to analyze the research trends of computerized language analyses in Asian ‘language and linguistics’ research.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

In Meo et al. (2013), the information regarding each country’s R&D spending was provided by the World Bank.

This study referred to Beall’s list (https://beallslist.net/, visited May 2023) for the titles of predatory journals.

At the beginning of every year, the citation records of articles published in the previous year had not yet been fully collected. Thus, in February 2022, when this study executed its sample data collection, the 2021 citations were not available to the fullest possible level. Thus, the target articles published from 2016 were excluded from the research impact analysis.

Note that authors’ affiliated countries were not necessarily the same as their nationality. Furthermore, both the affiliations and the countries were the ones in which the authors published their articles; as such, these affiliations are prone to change.

The list of 28 countries were from Meo et al. (2013).

‘Arabic,’ ‘Cantonese,’ ‘Chinese,’ ‘Hebrew,’ ‘Japanese,’ ‘Korean,’ ‘Malay,’ ‘Mandarin,’ ‘Mandarin Chinese,’ ‘Persian,’ and ‘Turkish’.

‘morphology,’ ‘phonology,’ ‘pragmatics,’ ‘semantics,’ and ‘syntax’.

‘EFL,’ ‘EFL learners,’ ‘EFL teachers,’ ‘English,’ ‘English as a foreign language,’ ‘English as a lingua franca,’ ‘English for academic purposes,’ ‘English language teaching,’ and ‘ESL’.

‘classroom discourse,’ ‘conversation analysis,’ ‘critical discourse analysis,’ ‘discourse,’ ‘discourse analysis,’ ‘discourse markers,’ and ‘metadiscourse’.

The current study used author IDs provided by Elsevier’s APIs to identify same authors.

References

Aghaei Chadegani A, Salehi H, Yunus M, Farhadi H, Fooladi M, Farhadi M, Ale Ebrahim N (2013) A comparison between two main academic literature collections: Web of Science and Scopus databases. Asian Soc Sci 9(5):18–26

Ahn J, Oh D-h, Lee J-D (2014) The scientific impact and partner selection in collaborative research at Korean universities. Scientometrics 100(1):173–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-013-1201-7

Aksnes DW (2003) A macro study of self-citation. Scientometrics 56(2):235–246. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1021919228368

Archambault É, Vignola-Gagné É, Côté G, Larivière V, Gingrasb Y (2006) Benchmarking scientific output in the social sciences and humanities: the limits of existing databases. Scientometrics 68(3):329–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-006-0115-z

Arhab N, Oussalah M, Jahan MS (2022) Social media analysis of car parking behavior using similarity based clustering. J Big Data 9(1):74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-022-00627-x

Arik BT, Arik E (2017) “Second language writing” publications in web of science: a bibliometric analysis. Publications 5(1):4

Barrot JS (2017) Research impact and productivity of Southeast Asian countries in language and linguistics. Scientometrics 110(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2163-3

Barrot JS, Acomular DR, Alamodin EA, Argonza RCR (2022) Scientific mapping of English language teaching research in the Philippines: a bibliometric review of doctoral and master’s theses (2010–2018). RELC J 53(1):180–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220936764

Beall J (2012) Predatory publishers are corrupting open access. Nature 489(7415):179–179. https://doi.org/10.1038/489179a

Bergmann T, Dale R (2016) A scientometric analysis of evolang: Intersections and authorships. Paper presented at the Evolution of Language: proceedings of the 11th international conference (EVOLANG11). Evolang Scientific Committee, New Orleans

Bhardwaj RK (2017) Information literacy literature in the social sciences and humanities: a bibliometric study. Inf Learn Sci 118(1/2):67–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-09-2016-0068

Boldyrev NN, Dubrovskaya OG (2016) Sociocultural specificity of discourse: the interpretive approach to language use. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci 236:59–64

Bui Hoai S, Hoang Thi B, Nguyen Lan P, Tran T (2021) A bibliometric analysis of cultural and creative industries in the field of arts and humanities. Digit Creativity 32(4):307–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2021.1993928

Campanario JM (2011) Empirical study of journal impact factors obtained using the classical two-year citation window versus a five-year citation window. Scientometrics 87(1):189–204

Ceballos HG, Fangmeyer J, Galeano N, Juarez E, Cantu-Ortiz FJ (2017) Impelling research productivity and impact through collaboration: a scientometric case study of knowledge management. Knowl Manag Res Pract 15(3):346–355. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41275-017-0064-8

Chang Y-W (2022) Capability of non-English-speaking countries for securing a foothold in international journal publishing. J Informetr 16(3):101305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2022.101305

Chen X, Xie H, Wang FL, Liu Z, Xu J, Hao T (2018) A bibliometric analysis of natural language processing in medical research. BMC Med Inform Decision Making 18(1):14

Chinchilla-Rodríguez Z, Miguel S, de Moya-Anegón F (2015) What factors affect the visibility of Argentinean publications in humanities and social sciences in Scopus? Some evidence beyond the geographic realm of research. Scientometrics 102(1):789–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1414-4

Clark A, Fox C, Lappin S (2012) The handbook of computational linguistics and natural language processing, vol 118. John Wiley & Sons

Costas R, van Leeuwen TN, Bordons M (2010) Self-citations at the meso and individual levels: effects of different calculation methods. Scientometrics 82(3):517–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-010-0187-7

De Filippo D, Aleixandre-Benavent R, Sanz-Casado E (2020) Toward a classification of Spanish scholarly journals in social sciences and humanities considering their impact and visibility. Scientometrics 125(2):1709–1732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03665-5

Devlin J, Chang M-W, Lee K, Toutanova K (2019) BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of NAACL-HLT

Fischer S (2003) Globalization and its challenges. Am Econ Rev 93(2):1–30

Georgas H, Cullars J (2005) A citation study of the characteristics of the linguistics literature. College Res Libr 66(6):496–516

Giarelis N, Kanakaris N, Karacapilidis N (2021) A comparative assessment of state-of-the-art methods for multilingual unsupervised keyphrase extraction. Paper presented at the IFIP International conference on artificial intelligence applications and innovations

Guo X (2022) A bibliometric analysis of child language during 1900–2021. Front Psychol 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.862042

Haddi E, Liu X, Shi Y (2013) The role of text pre-processing in sentiment analysis. Procedia Comput Sci 17:26–32

Hao T, Chen X, Li G, Yan J (2018) A bibliometric analysis of text mining in medical research. Soft Comput 22(23):7875–7892. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-018-3511-4