Abstract

Agriculture is a mode of production that maintains its importance for humanity across all historical periods. Despite the development of technology and the mechanization that comes with it, agricultural labour continues to be the basic element of agricultural production. Seasonal work is one of the most common types of agricultural work, which is shaped by the different production conditions in a country. In Turkey, where agricultural product diversity is quite high due to a favourable climate, most agricultural workers migrate to different regions seasonally for work in agricultural production. Therefore, it is important to evaluate this group’s problems and life experiences from sociocultural and economic perspectives. In this respect, research was carried out using qualitative techniques in the towns of Kavaklidere and Piyadeler in the Alasehir District of Manisa Province. These regions are important seasonal destinations for migrant agricultural workers during harvest periods. These regions produce 1/3 of the seedless raisins in the country. In-depth interviews were conducted with 20 seasonal migrant agricultural workers determined by judgemental sampling, and semistructured observations were carried out in the research area. Based on the results of this research, this study reveals that seasonal migrant agricultural workers in the region live at standards far below the general welfare level of society. Workers generally do not have social security. However, seasonal agricultural work for migrants has turned into a regular work- and lifestyle. The most important reason for this situation is poverty in rural areas. The workers are different from the local people in terms of ethnic origin. However, there is a long-standing relationship of trust between the local people and the workers. Workers do not have any problems with wages. These are other factors that ensure the continuity of seasonal agricultural work. In this context, this study proposes that the project (METIP) carried out by the government for seasonal migrant agricultural workers in Turkey should be transformed into an employment-guaranteed national programme that includes solutions for all the problems identified in the field studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nutrition is one of the basic elements ensuring the continuation of human biological existence. For this reason, in every period of history, human beings have had to struggle constantly to meet other human needs as well as their basic physiological needs, such as nutrition. The Neolithic period, occurring after the hunter-gatherer period, has been accepted as the period when agricultural production activities started to meet nutritional needs for the first time; this has been described as a revolution in terms of human history. During this period, when agriculture emerged as the main mode of production for the first time, nutrition patterns were not the only things to change. This period witnessed the emergence of the first examples of settled life. With this new lifestyle, the relations that took place primarily within the framework of agricultural production turned into more complex socio-cultural and economic relations with changing time and technical possibilities.

In the process leading up to the century we live in, with the Industrial Revolution that emerged from the middle of the 18th century, a period began that transformed agricultural societies into industrial societies. Industrialization has removed production from household and farm and has moved it into workshops and factories. Along with industrialization, serious increases have occurred in the production of agricultural products and the manufacturing sector (Kottak, 2002). Therefore, a period has begun where producers no longer produce only to meet their own needs. It is unquestionable that everyone needs products and services made by others (Toffler, 2018). In addition, as a result of successive technological innovations in this period, traditional social relations and lifestyles have also been transformed. A very large part of the working population in industrial societies has come to work in factories or offices instead of agriculture (Giddens, 2000). This has resulted in the concentration of the population in cities.

Alvin Toffler describes the Agricultural and Industrial Revolution, which we have tried to address as a historical process, as the “first” and “second” waves of change that led to new lifestyles that humanity had not experienced until then. Toffler names the process of change brought about by our current period the “third wave”. According to him, the third wave reveals a new type of society that removes the historical barriers between the producer and the consumer (Toffler, 2018). These societies, named postindustrial societies by Daniel Bell, differ from preindustrial and industrial societies as economic activities transitioned from producing goods to producing services. These services are mostly concentrated in areas such as education, health, social services, and professional areas such as communication and information systems (Bell, 1995).

When the historical development of human societies until today is evaluated in general, this process, which especially started with meeting nutritional needs, notably turned into an economic system and lifestyle with agricultural production. In this respect, industrial societies created by the Industrial Revolution and today’s postindustrial societies are accepted as advanced and developed societies that cannot be compared with agricultural societies.

Today, being an agricultural society means belated or even stalled development in terms of social and economic change, and agriculture is considered an underdevelopment problem (Bozkurt, 2015; Buke, 2015). However, although the societies in the world we live in are structurally transformed, agriculture maintains its sectoral importance. In the modern system dominated by the global economic system and competitive market conditions, agriculture is an indispensable element for meeting the nutritional needs of countries. It is still an important employment area for the working-age population. It has been providing raw materials and capital for different sectors. It has impacted exports, and it is a basic element of ecological balance (Dogan et al., 2015). When evaluated in the context of Turkey, agriculture is notably not independent from the conditions of the global economic system, and it is still very important both in terms of sectoral production and its contribution to other sectors. In this respect, this study aims to contribute to the sociological evaluation of the current agricultural situation in Turkey. In this context, it focuses on the position, problems, and life experiences of seasonal migrant agricultural workers who are labourers in the agricultural sector.

There are many field studies on seasonal agricultural work in Turkey. In these studies, seasonal agricultural work is generally defined as the seasonal participation of workers from different regions in agricultural production to meet the needs of the agricultural workforce. Seasonal agricultural work has two important characteristics: it is migratory and temporary. Due to these characteristics, seasonal agricultural work is considered an informal economic activity. In this respect, it is a new form of labour. Seasonal agricultural work differs from small-scale farming, subsistence farming, paid agricultural work, and unpaid family work, which are the recognized forms of labour in Turkish agriculture (Cinar and Lordoglu, 2011; Gorucu and Akbiyik, 2010). However, there are also studies that address the regional and nonregional dimensions of seasonal agricultural work separately. In these studies, seasonal agricultural workers residing in the region are described as “temporary”, while agricultural workers residing outside the region are described as “migrant” workers (Ozbekmezci and Sahil, 2004; Arslan, 2016).

In addition, some studies consider seasonal agricultural work informal work that has become compulsory as a result of the neoliberal transformations in the country’s agriculture after the 1970s. In fact, in this period, inequalities in the distribution of land gradually increased. In the 1990s, there were forced migrations from the rural areas of the Southeast to cities. Village evacuations were carried out by the government. This situation dispossessed rural residents from their property. In particular, many of those living in the southeastern rural areas lost their lands, and the proletarianization processes accelerated (Boratav, 1980; Akbiyik, 2011; Yildirim, 2015, 2016). In addition, some studies emphasize that the negative effects of increasing market pressure on small and medium-sized enterprises and the disintegration of unpaid family labour caused the spread of new low-paid, precarious and high-risk forms of work in agriculture (Arslan and Sengul, 2021; Teoman et al., 2012).

In this respect, studies dealing with seasonal agricultural work in Turkey mostly emphasize a single dimension of the subject. Because seasonal agricultural workers are mostly landless peasants from the South-eastern Anatolia region, there are some studies focusing specifically on ethnic discrimination and exploitation (Pelek, 2022; Duruiz, 2012, 2015, 2019; Uzun, 2015; Onen, 2012). In addition, there are studies that only address problems sheltering workers (Akalin, 2018) or caring for their health (Kaya and Ozgulnar, 2015; Fereli et al., 2016). In addition to the studies that address the living conditions of children as seasonal agricultural workers (Dedeoglu et al., 2019; Kantar Davran et al., 2014), there are studies that focus only on the problems of older workers (Ozkan, 2022). Additionally, some studies focus only on the problems of female workers (Kucukkirca, 2012; Celik et al., 2016).

Turkey is a country rich in agricultural product diversity. Seasonal migrant agricultural workers work in cotton farms in Cukurova in the Mediterranean Region. They work in onion, sugar beet, and carrot farms in the Central Anatolian Region. They work in apricot farms in the Eastern Anatolia Region. They work in fresh vegetables, cotton and olive farms in the Aegean Region. They work in the hazelnut harvest in the Black Sea region (Yilmaz, 2019). Therefore, studies on the subject have concentrated on these regions. In these studies, quantitative research methodology was mostly used. However, there are also studies conducted with qualitative research methodology. The most important limitation of these studies is that they are mostly aimed at determining the problems faced by workers in their working life (Akbiyik, 2011; Cinar and Lordoglu, 2011; Orhan, 2017; Sen and Altin, 2018).

There is limited availability of field studies related to the Manisa region where this research was conducted. In one of these studies, the problems faced by seasonal agricultural workers in their working life were examined, and a life satisfaction scale was applied to 150 workers in the region. As a result of the study, it was determined that there were significant relationships between the socioeconomic status of the employees and their satisfaction with life, income and work (Afsar and Isik, 2018). The study by Pelek (2019) was carried out in Adana and Mersin provinces, as well as Manisa province, with Syrian refugees working as seasonal migrant agricultural workers. This study critically discussed the working and living conditions that make this group more vulnerable than other ethnic workers in seasonal agricultural work.

Therefore, no field study has been conducted with a holistic perspective on the position, sociocultural problems and life experiences of seasonal migrant agricultural workers in the current social structure. This study discusses the current position and problems of seasonal migrant agricultural workers in the sociocultural structure in depth. It tries to reveal what it means to be a seasonal agricultural worker from their own perspective. Although seasonal migrant agricultural work is a vulnerable form of employment in the labour market, this study attempts to reveal why workers have long maintained these positions as regular jobs based on the workers’ own life experiences. In this respect, the study fills an important gap. The study claims that rural poverty is not the only reason seasonal migrant agricultural workers come to this region and work in seasonal agricultural work. It argues that the amicable relationships established by the workers with the local people transform seasonal migrant agricultural work into a form of labour and socialization that is inherited from generation to generation.

Conceptual framework

Although the phenomenon of agriculture is defined differently within the framework of different disciplines and approaches, in general, it can be defined as the “production of herbal and animal products, increasing their quality and efficiency, protecting them under appropriate conditions, processing and valuation and marketing, and agriculture, culture” (TDK, 2021). In Turkey, when the subject is considered within the framework of the relevant legislation, agricultural activities are handled with a much more comprehensive evaluation in Article 19 of the Social Insurance and General Health Insurance Law No. 5510 (Turkey Legal Gazette, 2006). The activities defined in this law were discussed in Article 111 of Labour Law No. 4857, and it was decided that these activities would be determined by the regulations issued by the Ministry of Labour and Social Security (Turkey Legal Gazette, 2003).

When agricultural activities are evaluated holistically, the number of people employed in agriculture was determined to be 4 million 866 thousand in 2022, according to the results of the Turkish Statistical Institute Household Labour Force Survey. In terms of total employment, the agriculture sector ranks 3rd, with 15.8% of the workforce. Employment in the industrial sector is 21.7%. The productivity of the agricultural sector has been on a notable increasing trend since the last quarter of 2014. The services sector has the highest share, with 56.5% of total employment (TUIK, 2022a). As can be understood from the statistical data, although the employment rate in the agricultural sector in Turkey lags behind the industry and services sectors in total employment, agriculture continues to be a sector where almost one out of every five people is employed. Accordingly, the agriculture sector is the third largest part of total employment (Fig. 1).

Sectoral distribution of employment in Turkey (%). Source: (TUIK, 2022a).

Agriculture is one of the prominent sectors as a share of the national income in Turkey and has been increasing since 2002. In addition, Turkey is the 1st largest agricultural economy in the EU and the 7th largest in the world. It ranks in the top 5 of world production in more than 30 products. It exports 1827 agricultural products to 190 countries. These data show that Turkey has a very important place in world agriculture and provides the necessary conditions for global competition (TARSIM, 2019) (Fig. 2).

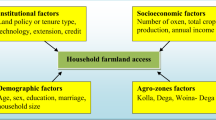

At various stages of the cultivation of agricultural products, human labour and modern machinery are used intensively. Since it is possible to grow a wide variety of products due to different climatic conditions, short-term seasonal agricultural work is quite common (Demir, 2015). Seasonal agriculture is one of the fields that requires labour-intensive work. In this context, seasonal agricultural work is a concept that refers to the seasonal or temporary work of people who do not have their own land, who do not have enough land, or who cannot cultivate this land for different reasons. Due to the changing character of agriculture depending on conditions such as the climate, economic opportunities, technology use, and the high level of informal employment in the sector, the number of seasonal migrant agricultural workers also varies (CSGB, 2010).

Although there is no clear statistical data system for the number of seasonal migrant agricultural workers in Turkey, it is possible to conclude that approximately half a million people work as seasonal migrant agricultural workers when household labour statistics and various research results on the subject are evaluated (TUIK, 2021; Development Workshop, 2020). In addition, the fact that there are four seasons in Turkey means that there is agricultural migration mobility throughout the year for seasonal migrant agricultural workers. According to the growing and harvesting conditions of agricultural products, seasonal migrant agricultural workers migrate to different regions to meet the labour requirements of agricultural production.

When evaluated in terms of developed countries, notably, the majority of those working in agricultural production are seasonal agricultural workers. In Europe, 4.5 million agricultural workers are employed, of which ~500,000 come from outside Europe. In the United States, this number is estimated to be ~2.5 million. It has been reported that more than half of those employed in agriculture in the USA immigrated from other countries (Renaut, 2003; Martin, 2004). Seasonal agricultural workers in developed countries consist of new migrants and temporary migrants from other countries. However, in developing countries, certain groups, mostly within the borders of the country, migrate temporarily to work in seasonal agricultural work (Cinar, 2014). In this respect, the definitions of migrant workers also vary according to the nation. Migrant Workers (Supplementary Provisions) Convention (1975) defines a migrant worker as “a person who migrates or who has migrated from one country to another with a view to being employed otherwise than on his own account”.

The widespread employment of seasonal agricultural workers in agricultural production in developed countries and the international character of migration have led to the creation of common programmes between receiving and sending countries. The Seasonal Agricultural Worker Programme (SAWP) in Canada is one of the most well-known subjects of many academic studies. This foreign worker programme fills the labour shortage in Canadian agricultural production with low-paid, temporary and foreign workers (Castell Roldán and Alvarez Anaya, 2022). In their ethnographic study, Castell Roldán and Alvarez Anaya (2022) conclude that this programme increases the precariousness and expendability of Mexican migrant agricultural workers, who constitute the vast majority of workers in the Canadian agricultural sector. According to them, this situation further deepened the proletarianization of the workers.

Leigh Binford (2002) criticizes Mexico–Canada Programme of Temporary Agricultural Workers based on the results of his field research with migrant agricultural workers in northwest Tlaxcala, Mexico. According to him, the income that workers earn in Canada makes their lives easier economically. However, this situation causes both workers and their families to pay significant social and psychological costs. Therefore, it should be repealed. While agreeing with Binford’s criticism, some researchers consider this Canadian programme to be an important model despite its flaws. Basok (2007) focuses on the functioning of the model by discussing the historical development of the SAWP programme. She states that this programme paves the way for a secure job and better life opportunities for foreign workers. She determined that 465 Mexicans surveyed between 1997 and 2000 had significant improvements in their living conditions through this programme. Similarly, Hennebry and Preibisch (2010) claim that this Canadian programme is the best model for seasonal migrant agricultural workers and sets an example for other developed countries, especially the USA.

In addition, there are studies that argue that the abolition of the SAWP in Canada will have negative consequences and that existing reforms should be expanded and transformed into permanent policies within the framework of the problems that academics have uncovered in field studies (Weiler and McLaughlin, 2019; Silverman and Hari, 2016). In addition to these studies, there are many different field studies examining the employment, wages, living conditions, legal status and problems of migrant workers who work seasonally in the agricultural sector of developed countries (Perloff et al., 1998; Barham et al., 2020; Culp and Umbarger, 2004; Ise and Perloff, 1995; Fiałkowska and Matuszczyk, 2021).

When evaluated in developing countries such as Turkey, seasonal migrant agricultural workers are the subject of many field studies focusing on their problems. In this context, Rogaly et al. (2002) examined the welfare-illfare status of seasonal migrant workers and their employers who migrated from East India to West Bengal to work in rice farming. They discussed the concept of welfare in a comprehensive way and considered the possibility of the formation of a collective identity among workers after migration. They concluded that seasonal migration is compulsorily preferred by workers; workers carry more health risks in the regions where they work, cannot access public health services to a large extent, and cannot choose private health services due to poverty. They also claim that they are excluded from welfare-oriented policies because of problems with security and social exclusion.

Another study on the region was conducted by Debnath (2021). The study focuses on the migratory behaviour of seasonal agricultural workers in the Rarh region of West Bengal. The study reveals that the migration routes of seasonal migrant agricultural workers have changed over time due to the low wages paid for agricultural labour. The study emphasizes that young men living in rural areas migrate to southern and western Indian regions regardless of the distance to work in other jobs with higher wages than agricultural labour.

In another study, Reddy et al. (2016) examined the structural transformation of Dokur village in Telangana, India, in the context of state-led development programmes after the 1970s. This study is based on data collected by ICRISAT between 1975 and 2010. This study reveals that with the enactment of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), both the social security net and the improvements made to eradicate rural poverty have become more inclusive of the poorer classes and lower castes. In this context, various government programmes such as ASHA workers, Anganwadi, PDS, and Aarogyasri arguably play an important role in the well-being of the country’s agricultural workers, the rural poor, and the general public, including the lower castes.

In another study on MGNREGA (Reddy et al., 2014), the programme is presented as based on the principle of providing the right to work legally by one’s individual demand and with a certain minimum wage. In this study, the effect of MGNREGA on the labour market and the country’s agriculture was analysed through numerical data. As a result of the practices carried out within the scope of MGNREGA, significant increases were observed in agricultural wages, especially women’s wages, and the mechanization processes in agriculture and the bargaining power of workers increased. Although the programme did not prevent migration for higher-paid jobs, it reduced dangerous migrations.

The national literature on seasonal agricultural workers is given in detail in the introduction of this study. When evaluated in general, agriculture is a sector that maintains its importance worldwide. As the employees of this sector, agricultural workers are a worthy subject for every study carried out about them. Therefore, in evaluating the living and working conditions of seasonal migrant agricultural workers, determining the problems they encounter, and focusing on their solutions, this study will contribute to the handling of agriculture from a sociological perspective specific to Turkey. It is important to consider the subject from a sociological perspective. A sociological perspective refers to the evaluation of the subject together with the other social systems that the individual interacts with. Starting from the work of C.W. Mills (1959), the general sociological point of view holds that problems and experiences can be considered not only in relation to the limited living space of the individual but also public problems of the social structure. For this reason, in this study, the current positions and problems of seasonal migrant agricultural workers are discussed in depth in relation to the whole social structure. Solutions are proposed to improve the working and living conditions of seasonal migratory agricultural workers.

Research design and data collection

The research was carried out with a qualitative research methodology. The main objective of the research is to understand the experiences of seasonal migrant agricultural workers, who constitute the sample, in their living and working conditions from their own cultural perspectives. In this context, in-depth interviews and semistructured observation methods were used in data collection. In-depth information was obtained from the participants through the guide interview form prepared for use within the scope of the subjects determined before the research. These data were interpreted by supporting the semistructured observations made in the field. In this way, the life experiences of seasonal migratory agricultural workers were revealed from their own cultural perspectives.

The research population consists of seasonal migratory agricultural workers who come to Manisa Province Alasehir District to work in vine harvesting. Manisa Province Alasehir District is located in the Aegean region of Turkey. Due to its climatic conditions, it is a region that allows the cultivation of many agricultural products. In addition, seedless raisin cultivation is quite common in the region as the main source of income (Sargin, 2013). Seedless raisin cultivation is carried out in all villages and towns of the district. Approximately 1/3 of the seedless raisins produced in the country are produced within the region’s borders. Therefore, the region hosts a large number of seasonal migrant agricultural workers from outside the region as well as from within the region during the vine-harvest period.

Judgemental sample selection techniques were used to determine the research sample since the study was carried out within the framework of qualitative research methodology. Judgemental sample selection techniques are used in qualitative research to identify examples from which in-depth information can be obtained in line with the purpose of the research. These techniques are based on the sampling technique that seeks elements of certain qualities (Savran, 2013). In this context, the researcher attempted to determine one or more subgroups in the population in which the research problem can be put forwards in the most typical way (Sencer and Irmak, 1984). Within this framework, the Kavaklidere and Piyadeler towns of the Alasehir district were selected since the region typically hosts groups that reflect the research universe and that have a homogeneous structure. The research sample consisted of 20 seasonal migrant agricultural workers who voluntarily agreed to participate in the research, chosen from seasonal migrant agricultural workers who came to these towns to work during the vine-harvest period. In this respect, the sample size is based on the topical saturation point.

The research was carried out during the vine harvest in the region. In-depth interviews were conducted with the seasonal migrant agricultural workers included in the sample between 15 August 2021 and 15 October 2021, and at the same time, semistructured observations were made in the field. In-depth interviews conducted within the scope of the research lasted an average of 45 min. The seasonal migrant agricultural workers participating in the research mostly come from the eastern and south-eastern Anatolian regions. In this respect, they mostly speak Kurdish among themselves. However, since they have been coming to the region for a long time to work and young people have been educated in formal education institutions, communication has been no problem. The help of an interpreter was used only during the interviews with elderly individuals. In-depth interviews were conducted individually, mostly during the workers’ rest periods. During the interview, the owner of the farm or agricultural intermediary was not present with the seasonal agricultural workers. For this reason, the answers given by the agricultural workers to the questions were unlikely to be affected. The questions were asked within the framework of the guide over the natural course of the conversation. The guide prepared for the in-depth interviews consisted of two parts. In the first part, there are questions about the demographic characteristics of seasonal migrant agricultural workers. In the second part, there are questions about the themes of establishing business connections, transportation to the region, accommodation conditions and nutrition, work, wages, working life and social security, education, benefits from health and social services, social exclusion, and the position of women. The answers given by the participants to the questions were audio-recorded with the consent of the participants, and voice recordings were rendered into textual transcripts at the end of the interview, and interpreted by the researcher.

In addition, a semi-structured observation form was prepared in line with the purpose of the research. In this observation form, the purpose of the research and the subsequent research questions are presented. The duration, location and scope of the observation are explained (Yildirim and Simsek, 2000). A code list was created within the framework of the main themes based on the guide prepared for the in-depth interview. The observations made in this framework were recorded in writing during the observation and analysed after the completion of the observations.

Results

Demographic characteristics of participants

When the research participants were evaluated by their demographic characteristics, 8 of the 20 participants were female, and 12 were male. No problems were encountered regarding the participation of women in the research. In terms of age, 9 of the participants were between 17 and 25, 3 were between 26 and 40, 4 were between 41 and 50, 3 were between 51 and 60, and one was over age 61. In terms of marital status, 10 of the participants were married, 9 were single, and 1 was widowed. When evaluated by their educational status, 2 of the participants were illiterate. The number of participants who could only read and write was 5. One participant was a primary school graduate, and 1 was a secondary school graduate. Three participants were continuing their high school education, 1 participant dropped out of high school, and 4 were high school graduates. The number of participants who were continuing university education is 3.

No participant stated that they had a regular income, except for 2 participants who had a pension. During the winter months, the income earned by working in seasonal agriculture in the summer is mostly used, and there is an attempt to earn income by working in daily jobs. Daily jobs are short-term jobs that are done for a maximum of 1–2 weeks around tasks for which an agreement is made to complete the entire project. Examples include dyeing, repair work, construction work and hawking. In this respect, the income earned during the winter months never exceeds the minimum wage. Finally, when the participants are evaluated in terms of family size, there are 4 participants whose family consists of 2 people, 1 participant with a family consisting of 3 people, 4 participants with families consisting of 4 people, 1 participant with a family consisting of 5 people, 5 participants with families consisting of 6 people, 3 participants with families consisting of 7 people, and 2 participants with families consisting of 10 people. In this respect, the participants in the research notably have mostly large families. In addition to families with many children, there are also families with extended family characteristics.

Establishment of business connections and transportation to the region

In Turkey, agricultural intermediaries have a very important place in both legal legislation and the informal relations network to enable seasonal migrant agricultural workers to establish business connections with agricultural employers. Additionally, these intermediaries have an important voice in regulations regarding conditions that provide employment, wages, work, accommodation, nutrition, etc., between seasonal migrant workers and agricultural employers. Within the framework of the “Regulation on Labour Intermediaries in Agriculture” of the Ministry of Labour and Social Security dated 27.05.2010 and numbered 27,593, business intermediation in agriculture is basically carried out by the Turkish Employment Agency. However, under certain conditions, real and legal persons can also perform agricultural intermediation, provided that permission is obtained from the institution (Turkey Legal Gazette, 2010a).

However, some seasonal migrant agricultural workers can establish business connections without resorting to agricultural intermediaries. Especially in certain regions, those who perform seasonal agricultural work as their life’s work can perform business planning independently of agricultural intermediaries. However, it does not seem possible to say that this is a highly preferred method since it is mostly a situation involving risks (Gorucu and Akbiyik, 2010; UNFPA, 2012).

In the region, agricultural intermediaries who are called “dayibasi and postabasi” locally establish business connections with seasonal migrant workers at the request of agricultural employers before the vine harvest season and mediate the employment of workers in the region. Agricultural intermediaries reside in the region. They know the agricultural labour needs of the region. Although some intermediaries reside locally, they have the same ethnic origin or kinship ties with the workers. Workers do not establish direct business connections with the farm owners. In such a situation, the farm owners can easily dismiss the worker. Generally, farm owners want to work with people referred by agricultural intermediaries. Disabling the agricultural intermediary often results in unemployment. The business connection process begins when farm owners ask an agricultural intermediary to meet the labour force they need for a particular job and for a specific period of time. The agricultural intermediary finds this needed labour force and unites them together with the farm owner. Participants described this situation as follows:

“Since we have been coming here for years, these people (local people) are always our friends, but dayibasi (the intermediary) is still our leader, he informs us, finds us a job and mediates” (Participant 1, male, age 55).

“Relatives inform us, we are coming with them” (Participant 2, male, age 17).

“Since we have been coming for years, my father is very close to the villagers here. They also call, but dayibasi (the intermediary) who is our relative living here, establishes the real business connection” (Participant 6, male, age 25).

Seasonal migrant agricultural workers arrange their own transportation to come to the region on the dates determined by the agricultural employer. Mostly, family members ride to the region on buses. In addition, there are agricultural workers who rent a car with their relatives as well as those who bring their own vehicles. It was observed that only a few families of workers in the region had their own private vehicle. Intermediaries or employers do not cover transportation charges, so agricultural workers cover transportation charges themselves:

“When migrating, we usually come with vehicles rented out to active agricultural workers in the region. My father is the driver, sometimes he brings us. It has been 2 days since I came from Aydin. I am a university student studying in Aydin. The remaining family members come from Mardin” (Participant 3, male, age 22).

“We come from Mardin. Usually, as a few families come from Mardin, we rent a shared minibus. Sometimes we cannot agree on the price. In that case, we come by bus” (Participant 14, female, age 18).

“I’m old and I cannot find as much work as I used to. That is why I try not to miss seasonal work opportunities. We are from Mus Varto. We came here by bus” (Participant 20, male, age 50).

Agricultural workers are transported intraregionally from the places where they stay during the vine harvest season to the fields where they work by the tractors, pick-up trucks, etc., of agricultural employers. In this way, they are transported without any traffic safety. Although there are regulations prohibiting such travel, this remains the most commonly used method of transportation within the region. This situation, which can cause traffic accidents, is also common in many regions where seasonal migratory agricultural workers work (Kaya and Ozgulnar, 2015; Orhan, 2017). It was observed that seasonal migrant agricultural workers in the region did not take any traffic precautions in their transportation to the fields, and they travelled with tractor-trailers. In addition, it was observed that the workers did not have any objections to this situation. This shows that the situation is taken for granted among the workers.

Shelter conditions and nutrition

Within the scope of the Prime Ministry Circular on “Seasonal Agricultural Workers” numbered 2017/6, the task is assigned to governorships to establish safe temporary settlement areas for agricultural workers suitable for local climatic conditions with clean water, electricity, and sewerage systems. Governorships perform this duty within the “Agricultural Workers Action Plan” framework (Turkey Legal Gazette, 2017). In this context, there are temporary settlement areas in the towns of Kavaklidere and Piyadeler. These settlements have been allocated by the town municipalities. Both are located by the river. There are single-story reinforced concrete sheds built on reinforced concrete ground in these temporary settlement areas. There are 10 of these sheds in Kavaklidere Town and 7 in Piyadeler Town.

During the vine-harvest period, families working in the region stay in these sheds collectively. In addition to these sheds, it was observed that 20 tents in Kavaklidere Town and 10 tents in Piyadeler Town were set up for sheltering purposes in the areas allocated for agricultural workers. There was no official allocation system for reinforced concrete shelters. Depending on their arrival priority or preference, families could stay in these sheds. These sheds did not have doors, and they were mostly covered with cloth or nylon covers to ensure privacy. On the other hand, tents were set up entirely by individuals, and wooden or metal supports were covered with cloth or nylon covers. In this context, the participants described their sheltering styles in the region as follows:

“Most of them stay in tents, but since we have a car, we come early and stay in the sheds built by the municipality. Even if it is not as good as a house, we are not looking for luxury; it is for recovering after the day” (Participant 6, male, age 25).

“We stay in tents here. The municipality has built reinforced concrete sheds, but they are useless, and the front is completely open. An animal or something may come in at night it may disturb us. Additionally, it is not possible to stay there when the weather is cold. Those who stay there set up tents after mid-September likewise” (Participant 12, male, age 56).

“We are staying in the tent now. But when we came last year, we stayed in the sheds (pointing to the reinforced concrete sheds built by the municipality). The shed was better than the tent. There was no opportunity this year” (Participant 20, male, age 50).

It was observed that there is no electricity in the reinforced concrete sheds where seasonal migrant agricultural workers stay, but electricity can be used through the lines provided by the municipality. The water is used from fountains built outdoors. The same is true for those who live in tents. The charges for electricity used during the working period in the region are paid by the workers. There is no charge for water. Participants described their use of electricity and water during their stay in the region as follows:

“We do not have a problem with electricity. I have no idea if it is billed. The municipality does not care at all” (Participant 3, male, age 22).

“It is not very clean, but water is everywhere” (Participant 5, female, age 19).

“There is electricity. We pay as we use it. Our dayibasi (the intermediary) is helping. We use the water from the fountain; we have one or two fountains. The water is already clean. There are also people in the village who use water from there” (Participant 9, male, age 49).

“The municipality allowed us to use electricity for a fee. We used a generator before, and we only use the electricity to light lamps and charge the phones” (Participant 17, male, age 26).

The shelter conditions for agricultural workers in the region carry health risks. Agricultural workers share bathrooms and toilets. Two bathrooms and toilets are in Kavaklidere Town. There are 3 bathrooms and 2 toilets in the town of Piyadeler. Both towns have water in the bathrooms and toilets. Available toilets and bathrooms are numerically insufficient to meet the needs of a large group of workers. The existing toilets and bathrooms are open to the use of at least 47 families, each of which consists of at least three people living in the area. This shows that at least 150–200 workers use these toilets and bathrooms. Agricultural workers staying in tents mostly use their own toilets and bathrooms, which are built with nylon or cloth covers. The use of such bathrooms and toilets is not suitable for sanitary conditions. Unfortunately, the same situation occurs in the toilets and bathrooms built with reinforced concrete. Communal life and temporary residence here mean that there are no provisions for necessary cleaning conditions. While this situation was not described as a serious problem by some participants, it was expressed by some participants as one of the most basic problems they experienced during their stay in the region:

“The municipality built here the toilet; they also built the bathroom. Sometimes it is not enough, but thank goodness” (Participant 2, male, age 17).

“We have a hard time; it’s always been the same problem for however many years I’ve been coming here. There is always a queue for toilets and bathrooms. The toilets for men and women are not private. Toilets and bathrooms are not sufficient. We build makeshift toilets and showers” (Participant 4, female, age 48).

“We already have toilets. The municipality has built 3 bathrooms. Since they are not sufficient, we set up tents for the showers. If there is no one staying in the tent, we put the water in plastic cans under the sun, so it warms up for when we arrive. If there is someone staying at home, he or she heats water until we arrive” (Participant 17, male, age 26).

Those who come to the region as seasonal migratory agricultural workers try to meet their nutritional needs mostly with dried legumes and spoilage-resistant foods that they bring with them to minimize food costs. At the same time, depending on the need, they shop at grocery stores and markets or public markets in the town. Workers keep the foodstuffs they bring with them or purchase from the region in reinforced concrete shelters or tents. In addition, there is no place used as a kitchen. For this reason, a refrigerator was provided by the municipality for the common use of the workers in both towns. Perishable foods are stored in these refrigerators. The agricultural employer does not provide the workers’ meals, and each family cooks its own food. It was observed that families often leave women with children or older women in shelters and tents to cook and do laundry. With such a division of labour, family members who cannot work in the field help with housework. Participants expressed this situation as follows:

“In terms of nutrition, those who come from their hometowns usually come prepared from home. We also shop in the market or the public market, depending on the need. Families keep their food and beverages in their tents or sheds. There is a shared refrigerator for perishable products” (Participant 3, male, age 22).

“We came here prepared. There is no problem with food or beverages. We keep perishable foods in the common refrigerator. Nonperishable foods such as rice and cracked wheat are in our tent” (Participant 4, female, age 48).

“We pay for the food and beverage expenses ourselves. Street vendors often come, and we shop from them. When they do not come, we go up to town” (Participant 19, male, age 49).

When the conditions for housing and basic human needs are evaluated in general, the participants live in unhealthy and uncomfortable conditions. The participants also express this observation. However, this situation is not considered unbearable since it is temporary, and the money earned is important for the family budget.

Job, wage, working life and social security

The jobs considered within the scope of agricultural work in Turkey are regulated within the framework of the “Regulation on Jobs Considered as Industry, Commerce, Agriculture and Forestry” dated 03.09.2008 issued under Article 111/2 of the 4857 numbered Labour Law. Those who work in the public sector as agricultural workers are subject to the Labour Law. However, under Article 4/I,b of the Agricultural Labour Law, the provisions of this law cannot be applied in workplaces or commercial enterprises where agricultural and forestry work is carried out by 50 or fewer workers. In this regard, seasonal migrant agricultural workers are excluded from the scope of the “Labour Contract” within the Labour Law due to their changing numbers and the fact that their work is not continuous. The principles regarding the working life of the workers are evaluated within the framework of the “Service Contract” within the scope of the Turkish Code of Obligations No. 6098 (Yucel and Omercioglu, 2016; Gorucu and Akbiyik, 2010).

In this respect, relations between agricultural intermediaries, workers, and employers often have to be formed informally. However, the duties and responsibilities of all three groups are determined by presenting the “Seasonal Agricultural Work Contract” within the scope of the “Regulation on Labour Intermediation in Agriculture” published in the Turkey Legal Gazette dated 27.05.2010 and numbered 27593 (Karaman and Yilmaz, 2011; Turkey Legal Gazette, 2010b).

In this framework, daily working hours and wages for male and female agricultural workers are determined by the “Worker Wages Determination Commission” established in provinces and districts. The daily gross worker earnings must not be below the minimum wage specified in Article 39 of Labour Law No. 4857. In addition, the wages of agricultural intermediaries are determined by this commission. Representatives of workers, employers, and agricultural intermediaries also attend these meetings and convey their demands. During the research, the working hours for the agricultural workers in the vine harvest were determined to be 8 h a day by the relevant commission. Again, the same commission decided that the lowest wage, 85 TL per day, would be given to grape-cutting work. It is the easiest work that can be done by both men and women and does not require any qualifications. The highest wage would be given to the dipping and onloading of grapes at 180 TL because it is very difficult and requires physical strength and endurance. Additionally, it was decided to pay an additional fee of 10 TL for agricultural intermediation.

For seasonal migrant agricultural workers participating in the research, seasonal work has become a regular routine that continues for generations. However, there is no job security, no guarantee of a regular income, and no social security. Most agricultural workers do not have jobs that will provide a regular income and social security in their hometowns, and they mostly try to make a living with the income they receive from their seasonal work as a family. In this respect, seasonal migrant agricultural work has become the most well-known way of earning a good income in a short time despite all the difficulties for the participants. These findings are in line with those of studies carried out both in this and other regions. (Yigit et al., 2017; Afsar and Isik, 2018; Akbiyik, 2011; Benek and Okten, 2011; Cinar and Lordoglu, 2011; Pelek, 2022). The participants described their working life as follows:

“We are trying to live with limited opportunities. We have many children, and we have many expenses. We earn 10,000 TL in the summer season. We come to work; we earn a monthly lump sum when we come here. We have been coming here for ten years. My husband sells vegetables with his truck, so he cannot come. My two sons and I work here” (Participant 4, female, age 48).

“It is good to work and earn money; if we work until the evening in my hometown, we earn 100 TL, but here we earn 150 TL before noon. Sometimes we go to work in the evenings. It is a good opportunity for us to pay for school expenses. Last year, we earned an average of 20,000 TL. I had come here 3 years ago. Last year I worked for 3 months. I have been here for a month this year, we came a little early. We went to pick tomatoes so we would not be unemployed. We were earning little, but it is better than being unemployed. I help my father who is a driver, and we have a small field in the village where we grow vegetables” (Participant 17, male, age 26).

“Our monthly income is 3 thousand TL on average. I do not have a regular job. I do daily jobs. I’ve been working for ten years. If I can find work, I do daily work in my hometown. I am old, and I can’t find a job as easily as I used to. That is why I try not to miss seasonal work. We are from Mus Varto” (Participant 20, male, age 50).

The region employs seasonal agricultural workers intensely, as this has been the production format for most of the grape harvests in the country for many years. In this respect, the economic relationship between the agricultural employer-agricultural intermediary and agricultural workers operates systematically, even if it is at an informal level, and agricultural workers do not experience any difficulties collecting wages. This fact emerges as one of the most important reasons why seasonal migrant agricultural workers regularly come to the region to work. In fact, workers do not go anywhere other than the region for seasonal work. The wages determined by the “Worker Wages Determination Commission” are distributed to the workers mostly at the end of the work season through agricultural intermediaries. Workers confirm this with the following statements:

“The fees vary according to the job. The intermediary takes note of those who go to the work. When the bosses bring the fees, he (the intermediary) distributes it to us. Bosses always bring the fees at the end of the month anyway” (Participant 7, male, age 23).

“The boss we work for brings and gives out the money. No, there has never been anyone who didn’t get paid. People here do not do such a thing” (Participant 15, female, age 35).

Although seasonal agricultural work has become an important source of income and is mostly a regular work routine for the participants, it does not provide social security due to legal regulations. Workers are required to pay individual social security premiums with income from seasonal work. There are two options here. Workers can become involved in the individual pension system by paying their premiums, or they can get involved in the public social security system by paying their own premiums. However, since the income of the workers is not sufficient, these two options cannot be evaluated by the workers. In this respect, many seasonal agricultural workers do not have social security. Many studies on the subject emphasize that most agricultural workers are deprived of social security (Bulut, 2013; Gunes, 2017).

As members of the social security system, participants had varying levels of coverage. Three participants are insured, 5 participants are insured due to their spouse or father, 1 participant does not have insurance, 1 participant is insured due to being a student, and 10 participants do not have insurance. However, these 10 participants are members of the “Green Card” system, which is health care offered by the state to cover the treatment expenses of citizens who cannot afford to pay (Turkey Legal Gazette, 1992).

Benefits from education, health and social services

One of the most important problems faced by seasonal migrant agricultural workers, especially their children, who have to migrate to other cities depending on the agricultural season, is the interruption of education during these periods.

This situation does not constitute an obstacle to education for the children of seasonal agricultural workers who come to this region for the vine harvest since the vine harvest season takes place during the summer months when schools are closed. However, if the family stays in the region for work other than harvesting or comes to the region earlier, the children do not come to the region and stay with one of the family members in their city of residence. In this respect, in this study, the findings were different from many other studies in the literature (Kantar Davran et al., 2014; Dedeoglu et al., 2019; Yilmaz, 2019).

As stated earlier within the framework of the demographic findings of the study, the education level of the participants, especially the older participants, is quite low. However, young participants continue their compulsory education process and even their university education. Participants emphasized the importance of education in having a profession and a regular job. This shows the increasing importance of education in the country. Additionally, in this way, the labour market participation process transforms the patriarchal values that the participants bring from their traditional cultures. The fact that the participants emphasized the importance of education and that they now come here to educate their girls even though they were not sent to school before proves this situation:

“I could not receive an education. All my children are studying. One of them graduated from university this year. One of them passed the exam this year and got into the university. Another of them will take the exam this year. The little one goes to elementary school. In addition, one of them got married too” (Participant 10, female, age 38).

“I am uneducated. I can only read and write. I learned to read and write too late. Our family did not send us to school because we were girls. We learned from our brothers. We are three sisters and two brothers. Our brothers were educated. The girls were not. Our brothers are teachers. I work with my children here; I have three sons “(Participant 13, female, age 54).

“I am going to get a university education. My brother is in high school (he is studying), the others are not. We are eight siblings. Six of them are not studying, and one is in high school. He’s in his senior year of high school now. He is studying in Mardin. We do not work in any other job, only seasonal. We only work in the summer. We come only in August, not in winter. We return in September-October” (Participant 5, female, age 19).

For their health conditions and access to health services, seasonal migrant agricultural workers are affected by their pattern of migrating from their places of residence at certain times of the year to regions with completely different climates and living conditions. They have significant disadvantages in terms of both migration conditions and living conditions in the working region. They may experience health problems due to unsuitable accommodations, nutrition, and sanitation conditions, as well as health problems arising from their work life. They may be exposed to chemicals used in agriculture and have occupational accidents. In addition, they may have difficulty acquiring adequate access to health services because they are mostly deprived of social security. They may also have difficulty acquiring access to the desired level of health services, such as maternal-child health, pregnancy follow-up, and vaccinations (MIGA, 2012).

In this context, the government provides a systematic solution to all the problems that seasonal migrant agricultural workers may encounter, such as transportation, accommodation, nutrition, cleaning, security, working life, education, and access to social services. “Circular on Improving the Working and Social Lives of Seasonal Migrant Agricultural Workers (2010/6)” has been issued. With the METIP (Project for Improving the Working and Social Lives of Seasonal Agricultural Workers) implemented with this circular, the aim is to improve the living conditions and access to services for seasonal agricultural workers in every aspect. Later, this circular was repealed, and the “Seasonal Agricultural Workers Circular” (2017/6), which includes more extensive regulations on the subject, was put into practice (Yigit et al., 2017).

When the seasonal migrant agricultural workers’ health problems and their healthcare access are evaluated, the participants do not claim to have too many problems from their working life. In this regard, the findings of the study differ from the findings of many national and international field studies (Barham et al., 2020; Rogaly et al., 2002; Hennebry et al. 2015; Fereli et al., 2016; Kaya and Ozgulnar, 2015; Fiałkowska and Matuszczyk, 2021). The workers stated that they could benefit from treatment opportunities by being taken to health institutions by the agricultural employer or agricultural intermediary when faced with any emergency health problem or work accident. Likewise, participants who do not have social security also have the opportunity to cover treatment and other health expenses with a “green card”. Participants expressed this situation as follows:

“Sometimes, some workers’ blood pressure or glucose levels drop due to the high temperature. Then, they immediately take him or her to the central hospital” (Participant 4, female, age 48).

“Sometimes, we get sick unintentionally. We tell them that we are sick, and then they come and take us to the hospital. Sometimes, dayibasi (the intermediary) take us to the hospital; sometimes, the boss. If we tell them, even the villagers take us to the hospital” (Participant 10, female, age 38).

“Sometimes we have muscle injuries, then both the boss and our intermediary try to provide every opportunity, we don’t have any problems other than that, thank goodness” (Participant 17, male, age 26).

However, when the seasonal migrant agricultural workers were asked whether they knew about the “Project for Improving the Working and Social Life of Seasonal Agricultural Workers”, which has been implemented for them since 2010, or what services they benefited from within the scope of this project, most of them were not aware of this project. They did not have any information about the services offered or how they could access them. Additionally, the participants stated that they did not find the services offered to them in the region sufficient in any way:

“I’ve never heard of it, I don’t know, there is no help either, we always deal with all the problems ourselves” (Participant 2, male, age 17).

“The municipality allowed us to use electricity. I know that it also built shared bathrooms and toilets, nothing more. You are the first to ask about our situation; I hope it will be good for us” (Participant 6, male, age 25).

“I remember my teacher talked about this project, but I did not research it. I have no idea; there is no personal service here. But the municipality built two toilets, two bathrooms, and 10 reinforced concrete rooms here” (Participant 7, male, age 23).

“What project? We didn’t even have electricity. We had to try so hard to build two toilets and two bathrooms here. They can’t even protect them what service are you talking about?” (Participant 12, male, age 56).

Social exclusion

Social exclusion is a very broad concept. It refers to the fact that some individuals and groups are considered separate from the general society due to their differences, such as biological, sociocultural, political, and economic differences, and that consequently, they cannot sufficiently benefit from rights and opportunities (Hekimler, 2012). From this point of view, seasonal migrant agricultural workers are among the groups with a high risk of being exposed to social exclusion due to their ethnic origins and different regional language and culture. Social exclusion is a subject that is overemphasized in field studies on agricultural workers. Basok (2004), in her research on Mexican workers in Leamington in a Canadian sample, found that workers could not establish adequate communication with the local people living in rural areas, mainly due to the language barrier. She determined that the cultural differences between the workers and the local people caused the workers to live in isolation and that although they had some legal rights, they could not demand these rights sufficiently due to social exclusion. In the case of Turkey, Isler (2022), in her research with workers working in hazelnut harvesting in Duzce and Sakarya provinces, found that social exclusion mostly occurs through labelling and marginalization over ethnic identity. In her work, she states that the tension between the local people and the workers sometimes turns into psychological and physical violence. In many field studies, it is possible to see that seasonal migrant agricultural workers are exposed to social exclusion (Rogaly et al., 2002; Silverman and Hari, 2016).

In the region where the research was carried out, no problems were observed in this regard. The participants mostly stated that they did not experience any problems in terms of language and culture in the region and that they were not exposed to social exclusion. The participants cited this situation as one of the most important reasons why they continued to come to the region for such a long time. Agricultural workers cannot participate in social environments much during their stay in the region since they live in an area far from settlements and spend most of their time working in the field. The socializing environments of the workers are mostly village coffee houses. Men spend some of their spare time in coffee houses with the local people. Apart from this, they can join the local community on special occasions such as weddings and funerals. However, workers do not experience significant problems when they share the same social environment with the local people. This situation shows that both groups accept each other in social life and working life. Participants expressed this situation as follows:

“We don’t have any problems. We teach Kurdish, they teach Turkish. We get along like that, but sometimes they don’t want to learn Kurdish much. No, they treat us well here. No one interferes with anyone. They do not interfere with us and we do not interfere with them” (Participant 10, female, age 38).

“We have been coming here for 35 years. We’ve all become like relatives. The newcomers may get a little bored, but they get used to them over time. Most of the workers already know Turkish. Those who know the language get used to the environment immediately. Those who do not know it usually do not leave their tents. We don’t have a problem, thank goodness. On the contrary, they even like to spend time with us” (Participant 12, male, age 56).

“There is a difference, but it’s okay. People here are sincere; they do not see us as strangers. We’ve been coming here for years so we feel like we’re one of them. No, everyone is already a worker. They do what we do. We are already in the village; no harm comes from the villagers, especially in the Aegean. Here, people are different; they are not bad” (Participant 13, female, age 54).

Position of women

Seasonal work, as an undeniable part of agricultural production, is not a form of work that includes only men. Seasonal migrant agricultural workers migrate to the regions where they will work with all members of their families. In this process, women and even children work together with men as agricultural workers. The women, who contribute to the family income by working with the men in the fields, also try to meet their family’s basic needs, such as nutrition and cleaning, in the remaining time (Fidan, 2020). This is a common finding of many field studies in Turkey. Ozbekmezci and Sahil (2004), in their field research in the Cukurova Lower Seyhan Plain, determined that the heads of households in the families of the workers are men and that both women and children do not have enough rights to speak up. The workload of female agricultural workers is quite heavy, especially since housework is considered work for only women. Afsar and Isik (2018) emphasize that this situation causes important health problems for women. Havlioglu and Koruk (2013) determined that being a woman is the most important factor that negatively affects the quality of life of seasonal migrant agricultural worker adolescents working in Sanliurfa. They emphasize that many adolescent women cannot continue their education life due to the difficult conditions of work and home life. Akbiyik (2011) found that the vast majority of female workers do not have social security, receive lower wages and mostly give their earnings to their spouses. The position of women as seasonal agricultural workers shows similarities not only on a national but also on a global scale (Rogaly et al., 2002; Silverman and Hari, 2016; Barham et al., 2020).

When evaluated in terms of the research region, similar to the abovementioned studies, it was observed that the gender-based division of labour is effective in family life, although women do agricultural work together with men. Women do not do jobs that require physical strength as much as men do in the field. The division of labour in the field is clear. However, when they return from the field, while the man is resting or spending time in the coffee house in his spare time, the woman cooks, washes the dishes, cleans the shed or tent, and takes care of the children. It is the woman’s responsibility to prepare breakfast, tidy up and organize other household chores before going to the field. Here, it is seen that women’s domestic labour, which does not turn into market value, is lost through gender-based role-sharing. The women who do not go to work in the field are mostly older. They also cook, do other household chores, or take care of children while others work in the fields. Their daughters are the ones who help women the most in household work.

Although exceptional, there are participants who state that their husbands or sons help them with housework. Participants expressed this situation as follows:

“As in all areas of life, the burdens of women are heavier here. We also work in the field for the same amount of time as them. When they return from the field, they do not sit idle. They cook, wash dishes. They restless. Okay, men also do heavy work compared to women. But in those temperatures, the fatigue of everyone whose shift is over is the same; the important thing is afterwards…” (Participant 7, male, age 23).

“Women work harder. When the man comes home from work, he expects the woman to prepare food. When the woman comes from work, she cooks. The man sleeps after eating. The woman does the laundry, and tidies up the mess. Not only here, but everywhere, women are like that” (Participant 13, female, age 54).

“My husband is very helpful. He does everything, he helps me. We work together at home and at work” (Participant 15, female, age 35).

“Everyone’s job is clear in the vineyard. But when everybody is in the tents, the men sleep, the women work. It’s not like that in our family, my father helps my mother. Our father helps us with most of our chores. Sometimes he even says let me do the laundry and stuff” (Participant 18, female, age 17).

Conclusion

As in the rest of the world, the agricultural sector in Turkey continues to exist as a labour-intensive sector. Agricultural production, which depends on climatic and seasonal conditions, causes an intense need for agricultural labour during growing and harvesting periods. This need is mostly met by seasonal migrant agricultural workers who come from different regions of the country and carry out agricultural production. In this respect, it is impossible to evaluate this group, which has a significant population size, only as periodic actors of working life. Since they are an important part of social life, they also have a sociologically important position.

This study is an effort to understand the living and working conditions of seasonal migrant agricultural workers and the problems they face from the cultural perspective of the participants. For this reason, in-depth interviews were conducted with 20 people working as seasonal migrant agricultural workers in the Kavaklidere and Piyadeler towns of Manisa Alasehir district, which were used as the sample. Semistructured observation was carried out. This study is based on the results of these in-depth interviews and semistructured observations.

The results of this study cannot be generalized to all seasonal migrant agricultural workers in Manisa Province. It is limited to the time period in which the study was carried out and its participants. Other limitations of the study are that interviews with seasonal agricultural workers are carried out during workers’ resting hours and it is difficult to make observations outside of working hours.

The study addresses the social and cultural problems of seasonal migrant agricultural workers from a holistic perspective. It discusses the reasons why seasonal agricultural labour has become a regular job. Based on the life experiences of the workers, the study questions the meaning of being a seasonal migrant agricultural worker. In this respect, it focuses on sociocultural processes that are not adequately addressed in the literature. The study structures the problems and life experiences of agricultural workers under 6 headings:

1—Establishment of business connections and transportation to the region; 2—Shelter conditions and nutrition; 3—Job, wages, working life and social security; 4—Benefits from education, health and social services; 5—Social exclusion; 6—Position of women

Notably, the workers came to the region during the summer periods, especially between August and October. While there are those who come to the region for a much shorter time, there are also those who come to the region earlier to work in other jobs. The majority of workers come to the region from the eastern and south-eastern Anatolian regions. Since the workers come to the region with their families, it is possible to come across workers from all age groups. The level of education decreases with age. Many young workers receive formal education as part of compulsory education, and there are even young workers who go on to university. The majority of the workers are married. Those who are single come to the region with their families or relatives.

In this study, the main reason for working in seasonal agricultural work is poverty. The situation in the region where they live inhibits their ability to have a regular income, which has made seasonal agricultural work a regular job. Agricultural workers, who mostly belong to extended families, spend the income they earn in the summer for their families throughout the year. Since they have come to the region to work in agriculture for many years, they have no difficulty in establishing business contacts for the following year. As in many regions, agricultural intermediaries play the most important role in this regard. Personal business contacts are not common. The workers organize transportation to the region, and agricultural employers or intermediaries do not interfere with this issue.

According to the semistructured observation results carried out in the research, agricultural workers stay in the areas allocated to them by the municipality during their stay in the region. Most workers live in groups in these areas, which are far from regular settlements and located by the stream. In both migrant worker settlements, there are a certain number of sheds, bathrooms, and toilets built by the municipalities. However, these are not enough for all families. Therefore, many families set up their own tents, toilets and baths. There is no problem with the use of electricity and water in the settled tents and sheds. However, it is not possible to say that these residential areas are healthy living units. In this respect, the workers want to improve the shelter conditions and complain about the indifference of the official authorities. However, most of the participants believed that the conditions were bearable given that the working period was short and the income earned during this period was substantial.

The employer does not cover the food and beverage expenses of the workers. Most of the workers bring most of their food from their home region to avoid additional costs. Workers only spend money on essential expenses during their stay in the region. Workers mostly work without social security within the framework of a service contract. The number of workers with individual social security is low. Many of them have a “Green Card”. It was observed that the working hours and wages determined by the relevant commissions are respected by both agricultural employers and intermediaries. Workers express their satisfaction in this regard.

Regarding the division of labour in the family, since agricultural work requires physical strength, mostly young people and men work in jobs that require more physical strength. Elderly individuals and women work in less strenuous jobs or deal with cooking, cleaning, and childcare. In this respect, there is a gender-based division of labour. It is also seen that women become more tired because they cope with both housework and fieldwork.

Agricultural workers stated that they did not experience any significant problems in terms of access to education, health, and social services, especially since their stay in the region was short. They stated that although they have different linguistic and cultural elements from the local people, they have never faced social exclusion. Contrary to the findings of many studies carried out in different regions, this situation indicates that seasonal agricultural work is an integral part of both work life and social life in the region.

In Turkey, since 2010, important arrangements and projects (METIP) have been made to improve the lives of seasonal migrant agricultural workers. However, agricultural workers state that they do not have any information on this subject or do not have access to individual services. Workers want improved living and working conditions and an increase in the quality of the services offered to them.

When the problems faced by seasonal migrant agricultural workers are evaluated holistically, the study suggests arrangements that will enable workers to be employed in their own living areas from the perspective of social policy and ecology. In addition, the quality of human capital for high-level jobs should be raised. However, as long as seasonal migrant agricultural work requires interregional social fluidity, the temporary living conditions of migrant seasonal agricultural workers should be ensured to reach the average welfare level of society. To achieve this, it is recommended that national-level, gender-sensitive, employment-guaranteed government programmes be established for seasonal migrant agricultural workers. In the creation of these programmes, the contributions of workers, employers and policy-makers should be established. It is recommended that new research be conducted in the fields of agriculture, education, health, social work and sociology for seasonal agricultural workers and to take measures to solve the problems identified in these studies.

Data availability

The datasets generated or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the interviewed group. However, they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Afsar S, Isik M (2018) Studies of seasonal labor mobility and seasonal agricultural worker problems encountered by life In Turkey: Manisa/Alasehir example. Int J Eurasian Stud 6(14):176–192. https://doi.org/10.33692/avrasyad.510617

Akalin M (2018) Assessment of seasonal agricultural workers’ housing conditions: sample of Yenice, Tarsus, Silifke. J Soc Insur 7(13):1–30. https://doi.org/10.21441/sguz.2018.65

Akbiyik N (2011) An analysis of social and economic problems of seasonal agricultural laborers working in Malatya. Electron J Soc Sci 10(36):132–154

Arslan A, Sengul M (2021) Seasonal agricultural work in terms of struggle to hold on to city of small villagers who separated from the rural lands: a research in the sample of Sanliurfa. J Labor Soc 2:1233–1261

Arslan H (2016) Understanding seasonal agricultural worker from the perspective of rural poverty. Int J Soc Sci Educ Res 2(4):1136–1147

Bell D (1995) Communication technology: for better or for worse. In: Salvaggio J L (ed) The information society economic, social & structural issues. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, London, pp. 89–103

Barham BL, Melo AP, Hertz T (2020) Earnings, wages, and poverty outcomes of US farm and low-skill workers. AEPP 42(2):307–334. https://doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13014

Basok T (2004) Post-national citizenship, social exclusion and migrants rights: Mexican seasonal workers in Canada. Citizensh Stud 8(1):47–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362102042000178409

Basok T (2007) Canada’s temporary migration program: a model despite flaws. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/canadas-temporary-migration-program-model-despite-flaws. Accessed 29 Apr 2023

Benek S, Okten S (2011) A study on living conditions of the seasonal agricultural workers: Hilvan county (Sanliurfa) sample. GAUN-JSS 10(2):653–676