Abstract

Within social-cognitive accounts of moral behavior, moral self-consistency or integrity, as conceptualized by Blasi, is assumed to link moral identity to moral behavior. The present study provides a novel account of moral self-consistency as an aspect of the self-organization of moral identity. I used two elements of moral identity to study moral self-consistency: moral values and moral scripts. The moral self-consistency of 410 participants was operationalized as the extent to which their responses on moral values, measured by the Moral Foundations Questionnaire, predicted their responses on moral scripts, measured by the Moral Foundations Vignettes. I identified two types of moral self-consistency: (1) individualizing and (2) binding. As predicted, when the respondents’ moral integrity was activated, (a) individualizing moral self-consistency was greater if it focused on individual moral integrity rather than national moral integrity, and (b) liberals exhibited more binding moral self-consistency than conservatives. This paper discusses the implications and limitations of the present study, as well as the potential for further development of social-cognitive accounts of moral identity.

“If you want to be a good person, make sure you know where true goodness really lies. Don’t just go through the motions of being good.”

Ajahn Fuang Jotiko, Buddhist Monk (Bhikkhu, 1993, p. 10)

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Good deeds are not necessarily performed by good people. Bad people can perform good deeds, and good people can perform bad deeds. Distinguishing the morality of deeds from the morality of people raises a number of challenging issues within moral psychology and forms the basis of the contradistinction between major paradigms such as consequentialism and virtue ethics (Annas, 2004). Arguably it is easier to define what constitutes a good act (taking the form, for example, of a prosocial act) than what a good person is. According to a synthetic view that incorporates classic work by Kohlberg, Blasi, Colby, and Damon, individuals are judged to be good or moral on the basis of the commitment they make to the person they are or wish to become (Bergman, 2002). Morality does not stem from performing moral actions alone, as the quote from Ajahn Fuang Jotiko suggests, but from having a self-commitment to moral norms in a way that is integrated with other elements of the self (Arvanitis and Kalliris, 2020; Beauchamp and Childress, 2001). This type of self-commitment to goodness is known as moral integrity and is associated with the notion of moral identity. Perhaps the most influential account of moral integrity was given by Blasi (1980, 1983, 1984), who saw integrity as personal moral self-consistency. Through this conceptualization of integrity, Blasi was especially interested in showing how moral identity could produce moral action. He did not, however, show a similar interest in how moral self-consistency contributes to the development of moral identity in the first place. Understanding more about moral self-consistency as the self-organization of moral identity is the purpose of the present research.

A social-cognitive approach to moral identity and its self-organization

Through a social-cognitive lens, moral identity is “stored in memory as a complex knowledge structure consisting of moral values, goals, traits, and behavioral scripts” (Aquino et al., 2009, p. 124). Research on moral identity has been dominated by the trait measure that Aquino and Reed (2002) introduced (Hertz and Krettenauer, 2016), but has not focused on moral values and behavioral scripts. Moral traits (being caring, compassionate, fair, friendly, generous, helpful, hardworking, honest, and kind) have been found to strengthen prosocial behavior for individuals that report having them (Aquino and Reed, 2002; Aquino et al., 2011). Within the moral identity tradition, self-consistency has been treated as a bridge between moral traits and moral behavior. It has not, however, been studied as a process that groups different elements of moral identities, such as values and behavioral scripts, so that they form a coherent aspect of an individual’s personality (i.e., as a basic process for the self-organization of moral identity). This study attempts to make that connection for the first time.

The self-organization of moral identity is expected to be a slow developmental process that takes place gradually as a person interacts with the environment (on the self-organization of identity, see Bosma and Kunnen, 2001). In approaching this developmental process, a good place to start is to consider how each isolated situation could add, incrementally, a property to self-organization. In accordance with Skitka (2003), it is necessary to know two things for each situation: (a) whether the situation engages the moral self and (b) the level of accessibility of aspects of the self. The effect of an engaging situational prime should be greater when there is chronic low accessibility of the moral self because chronically salient schemas will guide life tasks, irrespective of situational activation (Lapsley, and Narvaez, 2004). It should be noted, though, that research on situational activation focuses primarily on the enhancement of or further engagement in specific actions. The effects on moral self-consistency are not necessarily in the same direction. Situational activation of moral self-consistency could mean that individuals would assign less importance to a value in certain situations and decrease their engagement in moral actions.

What type of moral self-consistency?

Moral self-organization should not be thought of as a one-way street to becoming more moral. There is no unitary moral self that moral self-consistency would slowly work its way to. While a fully integrated, coherent, and unitary moral self might be an ideal end state that describes the virtuous person, there are probably different, even conflicting, views of morality that are present within the individual before such an ideal state can be reached (if ever). The assumption inherent in the present research is that the individual is constantly trying to bring different moral elements into harmony with each other when faced with morally engaging stimuli. These stimuli could, however, engage different aspects of the self. There may be aspects of the moral self that concentrate, for example, on fairness, and aspects of the moral self that concentrate on loyalty. Depending on the types of stimuli and the level of preexisting self-consistency, individuals may attempt to increase consistency in one aspect of the moral self rather than another.

While the moral identity measure of Aquino and Reed (2002) concentrates mostly on care and fairness and treats moral identity as a one-dimensional unitary concept, AlSheddi et al. (2020) showed that moral identity measures should go beyond care and fairness. To fully capture moral identity, they included binding moral foundations, as conceptualized by Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) in order to better reflect the differences in moral identity between citizens of Saudi Arabia and citizens of Britain. These different types of moral identity could further be associated with different types of moral self-consistency. In order to capture these differences, the present research adopts the framework of MFT with regard to moral values and behavioral scripts.

Moral Foundations Theory was developed by social and cultural psychologists to identify universal psychological moral systems and to account for cross-cultural differences. In addition to care/harm and fairness/cheating (called Individualizing Foundations), MFT identifies loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and purity/degradation (called Binding Foundations) as the foundations of morality, while being open to examining other candidates such as liberty/oppression, equity/undeservingness, and honesty/lying (Graham et al., 2018). Moral judgment is influenced by different moral foundations according to context (Piazza et al., 2019). The original five-factor structure (comprising care, fairness, loyalty, authority, and purity) seems to apply cross-culturally (Doğruyol et al., 2019), although there is also research that finds fewer factors when analyzing the most common measure of moral foundations, the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (e.g., Harper and Rhodes, 2021).

If, as argued above, moral self-consistency varies according to different aspects of the moral self, then morality foundations could be viewed as different building blocks of individuals’ moral selves. Furthermore, there may be other aspects of the self that are involved when moral self-consistency is activated, such as political identity. There is indeed evidence that political identity influences morality: Liberals endorse care and fairness (i.e., individualizing foundations) above most other values; conservatives endorse all values more equally (Graham et al., 2011; Kivikangas et al., 2021). Although political identity should not be equated with moral identity, there is likely overlap between the two concepts (Aquino and Reed, 2002). As the social-cognitive model of moral behavior would predict, the closer a political identity is to a person’s moral identity, the more likely it is to be activated when moral issues are raised because “neurons that fire together, wire together” (Aquino et al., 2009). This view has implications for self-consistency as well. According to the existing literature on MFT and political identity, we may expect individuals to be morally self-consistent with regard to binding values if they are conservative and to be morally self-consistent with regard to individualizing values both if they are conservative and if they are liberal. National identity is also associated with different types of values, especially binding values (loyalty, authority, purity). In order to further examine possible differences in moral self-consistency processes, especially in relation to political and national identity, this study looks at two types of self-consistency: binding moral self-consistency and individualizing moral self-consistency.

Scope of the study and hypotheses

The aim of this study is to examine moral self-consistency processes that are activated by situational cues. Self-consistency is operationalized as the extent to which moral foundation values, as measured by the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (Graham et al., 2008), predict behavioral scripts, as measured by the Moral Foundations Vignettes (Crone et al., 2021). Moral self-consistency according to these measures would mean that a person who highly values, say, purity, would strongly associate a violation of purity with wrongdoing. At the same time, a person who does not value purity highly can still exhibit high moral self-consistency: in this case, a morally self-consistent individual will not judge a violation of purity as morally wrong.

The first question addressed here is what type of situational cue engages the moral self. Potentially, any reference to moral values should engage the moral self. However, a specific reference to a person’s integrity (in a way, a direct reference to self-consistency) is more likely to evoke processes of self-consistency than a general reference to moral values. In simple terms, asking “What would you do as a moral person?” or “What would you do in this case if other people were judging your moral integrity?” is more likely to induce self-awareness and self-organization processes than a simple reference to values and principles—e.g., “What do you think the moral thing to do is in this case?” Moreover, a more specific reference to a group’s moral self, such as “What would you do as a patriot?” is more likely to engage the moral self on binding values than on individualizing values. Therefore it might be expected that, with regard to binding values, situational activation of either a national or an individual moral identity would evoke processes of self-consistency, whereas with regard to individualizing values, only situational activation of an individual moral identity would evoke such processes.

Hypothesis 1: When moral integrity is activated, individualizing moral self-consistency will be greater if it is focused on individual moral integrity rather than on national moral integrity.

Corollary 1a: When moral integrity is not activated, individualizing self-consistency will not differ between situations focused on individual moral integrity and those focused on national moral integrity.

Corollary 1b: When moral integrity is activated, binding moral self-consistency will not differ between situations focused on individual moral integrity and those focused on national moral integrity.

The second question addressed is the level of accessibility to moral values. As argued above, values that are chronically salient should guide behavioral scripts in a consistent manner, irrespective of situational activation. Phrased differently, situational activation of moral integrity related to values that are often accessed should have a smaller moral consistency effect than it would if it related to values that are rarely accessed. Furthermore, if activation concerns values that are central to a certain political identity, it would not be expected to have an effect on individuals that hold that particular political identity. Instead, it would be expected to influence individuals whose political identity is peripheral to these values, since they are less likely (than those whose political identity is central to these values) to think of certain scripts as relevant to moral values in the absence of a prime (see Aquino et al., 2009, for similar reasoning; see Lapsley, 2016, for chronic and situational activation). Such differential chronic activation according to political identity is expected to occur with reference to binding values. Whereas conservatives centrally support binding values, liberals support binding values only peripherally (Graham et al., 2009). Hence, moral integrity activation should have a greater influence on the binding self-consistency of liberals than it has on conservatives. Again it should be stressed that activating self-consistency for liberals may simply mean reducing their feelings of moral wrongdoing when a binding value is violated so that it reflects their low appraisal of that value.

Hypothesis 2: When moral integrity is activated, liberals will exhibit more binding moral self-consistency than conservatives.

Corollary 2a: When moral integrity is not activated, liberals will exhibit the same levels of binding moral self-consistency as conservatives.

Corollary 2b: When moral integrity is activated, liberals will exhibit the same levels of individualizing moral self-consistency as conservatives.

A last point concerns whether any observed consistency is authentic. According to Blasi (1983, p. 201), self-consistency has “the same dynamic nature as the desire for objectivity, for evidence and truth.” However, consistency could also be the product of moral hypocrisy (Monin and Merritt, 2012). Therefore it is also worth examining whether moral consistency is associated with any pressure or compulsion that would render any consistency observed as inauthentic.

Methods

Participants

According to Dawson and Richter (2006), in order to detect a moderate effect size and probe a three-way multiple regression interaction with 90% power, 410 cases are needed. Their probing procedure is conducted using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2022). Following Dawson and Richter’s suggestion, I recruited 410 participants (MAGE = 37.4, SDAGE = 13.7) for this study through the Prolific platform, which is viewed as offering higher quality data than similar platforms (Peer et al., 2022); 62.6% of the participants identified as female, 35.1% as male, 1.8% as non-binary/third gender, and 0.5% preferred not to say. All participants were citizens of the USA.

Procedure and design

Participants completed the questionnaire on the online platform Qualtrics. Initially, they were informed that the study was about thinking and reasoning in daily situations; they gave written informed consent, in line with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. They were then asked to complete the moral relevance section of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire.

Following this, the manipulation was introduced in the instructions for the Moral Foundations Vignettes. Participants were told that the purpose of the study was either to understand moral behavior (framed in terms of values and principles) or to assess their moral integrity (framed in terms of judging and testing their moral integrity). Also, the same instructions asked them to make an assessment from their own perspective (personal identity) or from a US perspective (national identity). Four different versions of instructions were created to accommodate this 2 (Framing: values and principles, moral integrity) × 2 (Identity: personal, national) research design (see Table 1).

Participants responded to the Moral Foundations Vignettes and, subsequently, to a pressure/compulsion scale. They completed a single-item attention check about the purpose of the study and indicated their political orientation, gender, and age. Finally, they were debriefed about the exact purpose of the study and completed their participation. The average reward per hour was £8.22.

Measures

Moral relevance

From the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ-30, Graham et al., 2008), this study used the first section on moral relevance. It asked participants to indicate the extent to which they found certain considerations relevant (0: Not at all relevant, 5: Extremely relevant) when deciding whether something is right or wrong (e.g., Fairness: “Whether or not someone acted unfairly”; Harm: “Whether or not someone suffered emotionally”; Ingroup: “Whether or not someone’s action showed love for his or her country”; Authority: “Whether or not someone conformed to the traditions of society”; Purity: “Whether or not someone violated standards of purity and decency”). The first section of MFQ-30 includes three items per foundation. The reliability measures for each dimension were satisfactory (Fairness: α = 0.749; Harm: α = 0.741; Ingroup: α = 0.750; Authority: α = 0.626, Purity: α = 0.701). In order to test the hypotheses, the study used aggregate measures for individualizing moral foundations (α = 0.820) and binding moral foundations (α = 0.844).

Moral foundations Vignettes

The brief 18-item version of the Moral Foundations Vignettes (MFV; Crone et al., 2021) was used, excluding the dimension of “liberty,” which was not present in the MFQ questionnaire. Three items per dimension examined the extent to which participants considered certain behaviors to be morally wrong (1: not at all wrong, 5: totally wrong). Examples: “You see an employee lying about how many hours she worked during the week” (Fairness); “You see a boy telling a woman that she looks just like her overweight bulldog” (Harm); “You see a former Army General from your country saying publicly he would never buy any of your country’s products” (Ingroup); “You see a teenage girl coming home late and ignoring her parents’ strict curfew” (Authority); “ You see a man in a bar using his phone to watch people having sex with animals” (Purity). The reliability measures for each dimension were adequate to low (Fairness: α = 0.516; Harm: α = 0.715; Ingroup: α = 0.720; Authority: α = .678, Decency: α = 0.628), as was expected for the brief 18-item version of the MFV (Crone et al., 2021). To test the hypotheses, the study used aggregate measures for individualizing moral foundations (α = 0.649) and binding moral foundations (α = 0.814).

Pressure/compulsion

A short four-item scale was designed to identify any pressure/compulsion participants felt while responding to the MFV questionnaire (α = 0.648). The purpose of this measure was to assess whether moral integrity manipulations would exert pressure that rendered any self-consistency observed as inauthentic. The items were: “I felt like there is something inside me which, in a way, forced or compelled me to respond in a specific way”; “I really felt controlled by my desire to do well at this task”; “I really felt I had to prove something when answering the questions”; “I felt pressured during the task.”

Attention check

The attention check was a single item: “The purpose of this research is to assess my personal level of moral integrity,” and participants were asked to respond on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all true; 7 = very true).

Political identity

Following Graham et al. (2009), participants were asked to rate their political orientation on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly liberal; 4 = Neutral (moderate); 7 = strongly conservative).

Demographics

Participants were asked to indicate their gender and age.

Results

Attention check

As expected, a 2 (Framing: Principles and values, Moral integrity)×2 (Identity: Personal, National) ANOVA revealed a main effect of framing, F(1, 406) = 52.96, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.12, indicating that the difference in framing was noticed by participants. More specifically, participants in the moral integrity conditions reported that the purpose of the research was to assess their moral integrity (M = 5.025) more than participants in the principles and values conditions (M = 3.547, p < 0.001).

Pressure/compulsion and MFV responses

Multiple 2 (Framing: Principles and values, Moral integrity)×2 (Identity: Personal National) ANOVAs did not reveal any main effect or interaction for pressure/compulsion or any of the MFV measures that followed the manipulation.

Individualizing moral foundations

In order to test hypotheses 1 and 2, I conducted a moderated moderation analysis using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 3, 5000 bootstrap samples, 95% confidence intervals; Hayes, 2022).

For Hypothesis 1, the goal was to test whether individualizing moral consistency (i.e., Individualizing MFQ predicting Individualizing MFV) was moderated by the interaction Framing × Identity, while controlling for political identity (see Table 2 for results).

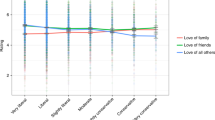

The model was significant F(8, 401) = 8.39, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.14. Importantly, the three-way Individualizing MFQ × Framing × Identity on Individualizing MFV was significant, b = −0.35, t(401) = −2.61, p = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.61, −0.09]. The Individualizing MFQ × Identity interaction was significant only in the moral integrity condition. The results are shown in Fig. 1, revealing that when moral integrity is activated, individualizing self-consistency is higher in the individual identity condition than in the national identity condition (support for Hypothesis 1), but the same is not true when moral integrity is not activated (support for Corollary 1a).

The equivalent three-way Binding MFQ × Framing × Identity on Binding MFV was not significant, b = −0.10, t(401) = −0.87, p = 0.38, 95% CI = [−0.32, 0.12], thereby showing that binding self-consistency was not different in national and individual identity conditions when moral integrity was activated (support for Corollary 1b).

Binding moral foundations

For Hypothesis 2, the goal was to test whether binding moral consistency (i.e., Binding MFQ predicting Binding MFV) was moderated by the interaction Framing × Political Identity (see Table 3 for results).

The model was significant F(7, 402) = 39.75, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.41. Importantly, the three-way Binding MFQ × Framing × Political Identity on Binding MFV was significant, b = −0.08, t(402) = −2.46, p = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.14, −0.02]. A Johnson–Neyman analysis showed that the Binding MFQ × Framing interaction was significant for the bottom 24.63% of the scorers on the political identity scale, roughly one-quarter of the more liberal participants. The results in Fig. 2 show that binding moral consistency seems to be higher through moral integrity framing for more liberal participants (support for Hypothesis 2), but the same is not true when moral integrity is not activated (support for Corollary 2a).

The equivalent three-way interaction with regard to individualizing foundations (Binding MFQ × Framing × Political Identity on Binding MFV) was not significant, b = 0.02, t(402) = 0.54, p = .59, 95% CI = [−0.05, 0.09], thereby showing that individualizing self-consistency did not vary according to political identity when moral integrity was activated (support for Corollary 2b).

Discussion

Moral self-consistency arguably develops through everyday moral activations that, as they accumulate, lead to moral integrity in the long term. Instead of treating moral self-consistency as a process that aligns behavior with moral identity (e.g., Aquino et al., 2009; Blasi, 1980), in the context of this study moral self-consistency is treated as a process that aligns moral values with moral scripts. In other words, it is considered a process that contributes to the self-organization of moral identity through a constant struggle for alignment among its different elements. The assumption is that this process is activated by social settings in the tradition of social-cognitive approaches to personality (Cervone and Shoda, 1999), although these approaches do not necessarily posit a self-consistency motive (Cervone and Tripathi, 2009).

The primary situational cue used in this study was a moral integrity situational activation, similar to the social mandate that often confronts people to be good, moral, or people with integrity. The question was whether such a situational cue would instigate a process of moral self-consistency and how it would vary according to factors relating to the nature of morality and aspects of an individual’s self.

First, the different elements of moral identity need to be taken into account. Current social-cognitive accounts of moral behavior focus more on moral identity as a trait, and less as a “complex knowledge structure consisting of moral values, goals, traits, and behavioral scripts” (Aquino et al., 2009, p. 124). There is no research to date on values and scripts as elements of moral identity. More importantly, the treatment of moral identity as one-dimensional (high or low) fails to acknowledge that moral identity could include different elements that are fragmented within the self, even in opposition to each other. Morality is mostly conceptualized as care and fairness, rather than in the more complicated manner advocated by MFT (Graham et al., 2013; Haidt, 2013). To broaden the concept of moral identity in this study, I used the two main pillars of binding and individualizing values, and self-consistency is measured as the alignment of values and scripts between these two pillars.

Second, other identities should be taken into account. I chose two identities that are also pertinent to moral identity: political identity and individual/national identity. Self-consistency is expected to be influenced by the connection among these interrelated but distinct aspects of the self, on two levels: (a) the degree to which a stimulus engages the self and (b) the degree of accessibility to moral values. With regard to (a), the self is more likely to be engaged when moral integrity cues are in line with the self. This study hypothesizes that, if moral integrity cues concern individualizing values, then invoking a national identity, which is mostly associated with binding values, will likely engage the self less than the invocation of an individual identity (Hypothesis 1, which was supported). With regard to (b), moral integrity activation will influence self-consistency in cases where accessibility to values is not high. This study hypothesizes that, because liberals do not associate their political identity with binding values, they are more likely than conservatives to be susceptible to moral integrity cues concerning binding values (Hypothesis 2, which was supported).

The support found for the two hypotheses and their corollaries in this research is just a first step in the examination of the self-organization of moral identity. It shows that other aspects of the self, such as national/individual identity and political identity may play a role when situational cues invoke self-consistency processes. However, there is no research on other possible interrelationships among aspects of the self or on how many such momentary activations would contribute to a more crystallized self-organization of moral identity. These ideas provide an avenue for further research.

Finally, a comment about the measure of moral self-consistency. This measure is not an index of higher or lower endorsement of values. It represents participants’ judgments about daily situations that are consistent with their already stated relevance of moral values. Participants could not return to see their answers on the Moral Foundations Questionnaire after the manipulation was introduced, and any differences in self-consistency can only be attributed to some inner adjustment before or during the participants’ responses to the Moral Foundations Vignettes. This type of consistency could serve as a useful operationalization for measuring moral integrity in general, as consistency is intertwined with integrity (Arvanitis and Kalliris, 2020). Nevertheless, there is a need to differentiate moral self-consistency from moral identity processes that lead to moral disengagement, moral hypocrisy, and moral licensing (Krettenauer, 2022), even if these processes lead to some sort of (inauthentic) consistency. The notion of moral self-consistency or integrity defended here is conceptualized as authentic, objective, and sincere (Blasi, 1983). It should be noted that there is no indication that individuals felt pressure to respond in any particular way, as illustrated by the between-conditions lack of difference in the pressure/compulsion measures and all MFV measures. This is important from Blasi’s (1983) perspective since self-consistency is intertwined with the tendency to be objective and truthful.

Limitations

While the present study offers some evidence for the expansion of the social-cognitive accounts of moral identity, it is only a first step in that direction. The findings apply primarily to a US population and to individuals recruited through the Prolific platform, especially because the focus of the research is moral foundations, which vary according to cultural context. Moreover, context would also be expected to convey different meanings to our manipulated variables, especially national identity cues. National identity is different for every nationality and is also expected to exhibit different moral properties—for example, during war or during a pandemic, such as COVID-19 (Su and Shen, 2021), which was ongoing when the research was conducted. Also, the activation of moral integrity was momentary and cannot account for the broader developmental process of the gradual self-organization of moral identity. Nevertheless, bringing the study of different types of values and related aspects of identity into the study of moral identity self-organization has been shown, through the present research, to provide an avenue for research.

Opportunities for future research

Moral identity includes traits, goals, moral values, and behavioral scripts. While the present research focuses on moral values and scripts, the next step is to examine their relationship to traits. For example, trait moral identity has been shown to attenuate the effect of binding moral foundations on prejudice (Smith et al., 2014) and would be expected to exhibit different associations with the distinct types of moral self-consistency. Further research could shed light on how binding foundations are linked to prejudice. A social cognitive model of moral identity self-organization also needs to be studied longitudinally in order to explain how momentary self-consistency activations contribute to moral integrity. Moreover, although the self-consistency observed in this study is arguably authentic, it is worth studying when social cues contribute to the exhibition of outward consistency rather than authentic inward consistency. This distinction is present in the symbolization/internalization distinction offered by Aquino and Reed (2002) and could be used in further research examining the authenticity of moral self-consistency. Last, all these effects can be studied in different situational and cross-cultural contexts.

Conclusion

The self is not uniform and coherent. Moral identity should be expected to develop gradually through a process of self-organization that does not advance in a straight line. Other aspects of the self will contribute to the process. The present study shows that social activation of moral integrity influences self-consistency processes according to political identity and national/individual identity. It is the first step in investigating the broader process of moral identity self-organization.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available in Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EDRJYT.

References

AlSheddi M, Russell S, Hegarty P (2020) How does culture shape our moral identity? Moral foundations in Saudi Arabia and Britain. Eur J Soc Psychol 50:97–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2619

Annas J (2004) Being virtuous and doing the right thing. Proc Addresses Am Philos Assoc 78(2):61–75. https://doi.org/10.2307/3219725

Aquino K, Freeman D, Reed II A, Lim VKG, Felps W (2009) Testing a social-cognitive model of moral behavior: the interactive influence of situations and moral identity centrality. J Pers Soc Psychol 97(1):123–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015406

Aquino K, McFerran B, Laven M (2011) Moral identity and the experience of moral elevation in response to acts of uncommon goodness. J Pers Soc Psychol 100(4):703–718. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022540

Aquino K, Reed II A (2002) The self-importance of moral identity. J Pers Soc Psychol 83(6):1423–1440. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1423

Arvanitis A, Kalliris K (2020) Consistency and moral integrity: a self-determination theory perspective. J Moral Educ 49:316–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2019.1695589

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF (2001) Principles of biomedical ethics, 5th edn. Oxford University Press, New York

Bergman R (2002) Why be moral? A conceptual model from developmental psychology. Hum Dev 45(2):104–124. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26763665

Bhikkhu A (1993) Awareness itself: the teachings of Ajaan Fuang Jotiko. P. Samphan Panich, Bangkok

Blasi A (1980) Bridging moral cognition and moral action: a critical review of the literature. Psychol Bull 88(1):1–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.1.1

Blasi A (1983) Moral cognition and moral action: a theoretical perspective. Dev Rev 3(2):178–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(83)90029-1

Blasi A (1984) Moral identity: Its role in moral functioning. In: Kurtines W, Gewirtz J (Eds) Morality, moral behavior and moral development. Wiley, New York, pp. 128–139

Bosma HA, Kunnen ES (Eds) (2001) Identity and emotion: development through self-organization. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 10.1017/CBO9780511598425

Cervone D, Shoda Y (Eds) (1999) The coherence of personality: social-cognitive bases of consistency, variability, and organization. Guilford Press, New York

Cervone D, Tripathi R (2009) The moral functioning of the person as a whole: On moral psychology and personality science. In: Narvaez D, Lapsley DK (Eds.) Personality, identity, and character: explorations in moral psychology. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 30–51

Crone DL, Rhee JJ, Laham SM (2021) Developing brief versions of the Moral Foundations Vignettes using a genetic algorithm-based approach. Behav Res Methods 53:1179–1187. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01489-y

Dawson JF, Richter AW (2006) Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: development and application of a slope difference test. J Appl Psychol 91(4):917–926. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.917

Doğruyol B, Alper S, Yilmaz O (2019) The five-factor model of the moral foundations theory is stable across WEIRD and non-WEIRD cultures. Pers Individ Diff 151:109547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109547

Graham J, Haidt J, Koleva S, Motyl M, Iyer R, Wojcik S, Ditto P (2013) Moral foundations theory: the pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 47:55–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00002-4

Graham J, Haidt J, Motyl M, Meindl P, Iskiwitch C, Mooijman M (2018) Moral foundations theory: on the advantages of moral pluralism over moral monism. In: Gray K, Graham J (Eds.) Atlas of moral psychology. The Guilford Press, New York, p 211–222

Graham J, Haidt J, Nosek BA (2008) The moral foundations questionnaire. https://moralfoundations.org/. Accessed 20 Jan 2022

Graham J, Haidt J, Nosek BA (2009) Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. J Pers Soc Psychol 96(5):1029–1046. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015141

Graham J, Nosek BA, Haidt J, Iyer R, Koleva S, Ditto PH (2011) Mapping the moral domain. J Pers Soc Psychol 101(2):366–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021847

Haidt J (2013) Moral psychology for the twenty-first century. J Moral Educ 42(3):281–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2013.817327

Harper CA, Rhodes D (2021) Reanalysing the factor structure of the moral foundations questionnaire. Br J Soc Psychol 60:1303–1329. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12452

Hayes AF (2022) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford Publications, New York

Hertz SG, Krettenauer T (2016) Does moral identity effectively predict moral behavior?: a meta-analysis. Rev Gen Psychol 20(2):129–140. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000062

Kivikangas JM, Fernández-Castilla B, Järvelä S, Ravaja N, Lönnqvist J-E (2021) Moral foundations and political orientation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 147(1):55–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000308

Krettenauer T (2022) When moral identity undermines moral behavior: an integrative framework. Soc Pers Psychol Compass 16(3):e12655. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12655

Lapsley DK (2016) Moral self-identity and the social-cognitive theory of virtue. In: Annas J, Narvaez D, Snow NE (Eds.) Developing the virtues: integrating perspectives. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 34–68

Lapsley DK, Narvaez D (2004) A social-cognitive approach to the moral personality. In: Lapsley DK, Narvaez D (Eds.) Moral development, self, and identity. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, New Jersey, pp. 189–212

Monin B, Merritt A (2012) Moral hypocrisy, moral inconsistency, and the struggle for moral integrity. In: Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (eds) The social psychology of morality: exploring the causes of good and evil. American Psychological Association, pp. 167–184

Peer E, Rothschild D, Gordon A, Evernden Z, Damer E (2022) Data quality of platforms and panels for online behavioral research. Behav Res Methods 643–1662. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-021-01694-3

Piazza J, Sousa P, Rottman J, Syropoulos S (2019) Which appraisals are foundational to moral judgment? Harm, injustice, and beyond. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 10(7):903–913. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550618801326

Skitka LJ (2003) Of different minds: an accessible identity model of justice reasoning. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 7(4):286–297. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0704_02

Smith IH, Aquino K, Koleva S, Graham J (2014) The Moral Ties That Bind . . . Even to Out-Groups: The Interactive Effect of Moral Identity and the Binding Moral Foundations. Psychol Sci 25(8):1554–1562. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614534450

Su R, Shen W (2021) Is nationalism rising in times of the COVID-19 pandemic? Individual-level evidence from the United States. J Chin Political Sci 26:169–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09696-2

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Studies that are non-funded, of negligible risk, and using non-identifiable data are exempt from formal ethics review according to the national legal framework that is in force at the corresponding author’s affiliated university.

Informed consent

Freely given, informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arvanitis, A. Moral self-consistency as the self-organization of moral identity: A social-cognitive approach. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 259 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01763-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01763-2