Abstract

The present study explores the realizing mechanisms of deliberate misinterpretation, by examining the specific situations of deliberate misinterpretation in fictional conversation, from the perspective of socio-cognitive pragmatics, so as to shed light on human daily conversations. The results of analyzing dialogs in the sitcom Friends show that deliberate misinterpretation has to do with the possibility of ambiguity on the speaker’s side and deliberate divergence on the hearer’s side. It is also argued that in these circumstances egocentrism on the hearer’s side is manifested consciously and deliberately. Unlike generally discussed, the deliberate breakdown of communication usually has a positive influence on the communication, and certain communicative goals of the speaker may thus be fulfilled.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Language has design features that make human communication different from any animal group, and verbal communication is the most common way of using language. In addition to stable factors connected with the interlocutors’ communicative abilities, cultural knowledge, or patterns of thinking, other less stable factors, such as their personal relationships, psychological states, or actions motivated by physiological functions, may also result in communicative problems (Manuel, 2017).

Communication has been a central concern in the study of pragmatics. In traditional pragmatics, linguists emphasize the issues that contribute to successful communication, focusing on the cooperation of interlocutors and the issues positive to the communication. However, the process of daily communication is not always that smooth. Consciously or unconsciously, the interlocuters may fail to be cooperative enough and the communication may be in dilemma. In some cases, the hearer fails to grab the exact intended meaning of the speaker, and misunderstanding may occur; but in some specific circumstances, the hearer may actually reach a consensus in the first place while deliberately giving unexpected responses diverging from the speaker’s intention, and by doing so certain communicative goals are achieved. This kind of linguistic phenomenon, which is the focus of the study, is regarded as deliberate misinterpretation.

Misinterpretation occurs in the stage of discourse comprehension, but what it reflects is a complete interactive communication process (Zhou, Chen, 2019). Deliberate misinterpretation happens when the meaning that the hearer misinterprets deliberately or misunderstands intentionally does not agree with what the speaker wishes to convey in his mind (Shen, 2004). Moreover, according to Shen Zhiqi, deliberate misinterpretation should possess three features, namely, the hearer’s intention, the hearer’s communicative strategy, and the mismatch between the hearer’s interpretation and the speaker’s original meaning. When features of deliberate misinterpretation are looked into, some inferences about the interlocutors can be made. The first feature implies that the hearer not only does the understanding and responding job but also actively participates in the attribution to the intended meaning, which is generally considered as the speaker’s duty. However, one significant difference is that in this circumstance the hearer intends to lead the conversation into a diverged direction. The second feature has pointed out the need of the hearer to fulfill certain communicative goals, and it is also been implied that those communicative goals should be beneficial only to the hearer. The third feature refers to the fact that the correct mutual understanding is achieved in the first place, but the hearer acts as if the misunderstanding occurs in order to produce an unexpected response to the speaker.

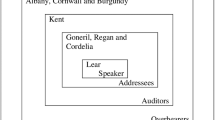

The study focuses on deliberate misinterpretation in English situation comedy based on egocentrism in socio-cognitive approach (SCA), and the reasons are as follows. Firstly, as a linguistic phenomenon, deliberate misinterpretation is commonly seen in daily communications, while it is much more frequent and typical in literary works including situation comedy. Additionally, when it comes to communicative goals, the humorous effect has always been a significant focus in the field of pragmatics, thus the data from a sitcom is quite proper and may shed light on the ongoing daily conversations. Moreover, compared to traditional pragmatic schools, SCA has its specific feature as a “hearer-speaker pragmatics”, which takes the speaker and hearer as integrity into consideration; SCA framework is a dialogical one, which takes the more dynamic and interactional issue into consideration, and it is more applicable for cases like deliberate misinterpretation. When concerning specific cases, frame semantics is also included as an important analysis approach since recontextualization may be closely related to different conceptual structures. Normally, conversation includes frames that “encode a certain amount of ‘real-world knowledge’ in schematized form”; in deliberate misinterpretation cases, however, frames that “encode patterns of opposition that human beings are aware of through everyday experience” may be kernel to the realization of communicative goals (Lowe et al., 1997, p. 19). For spectators as the third party, they “expect certain events to occur and states to obtain” because of the “stereotyped scenarios-situations” that are programmed by them; the humorous effects of the dialog may be appreciated via a kind of “defeated expectancy”, here the unexpected meaning of the situation.

The linguistic data is collected from the English situation comedy Friends. By viewing the data based on the egocentrism perspective, the paper aims to better understand the realizing mechanism and indispensable components of deliberate misinterpretation. Compared to natural communication, artificially designed dialog in literature work has its distinctive feature as including the third party’s inference and interpretationFootnote 1; thus, the study also has its novelty as including not only the interlocutors but also the spectators’ appreciation of humorous effects. Hopefully, it may also be helpful to the smoothening of daily communications and the fulfillment of certain communicative goals.

Literature review

In this section, a brief review of the previous studies of deliberate misinterpretation will be given. Previous studies on deliberate misinterpretation have been the by-studies of misunderstanding, generally covering four aspects, namely the discoursal origins (Verdler, 1994; Schegloff, 1987), the contextual origins (Richard, 1964; Taylor, 1992), the psychological origins (Sperber, Wilson, 1995; Keysar, 2008; Zong, 2003, 2005) and social origins (Gumperz, 1982; Tannen, 1990).

Most scholars have conducted their studies on deliberate misinterpretation mainly from the perspective of pragmatics, and they have regarded deliberate misinterpretation as a communicative strategy in verbal communication. Fisher applies a non-understanding strategy. He discusses people’s communicative actions and pragmatics of human relations when people are talking with each other in a face-to-face context in his book Interpersonal Communication: Pragmatics of Human Relationships. He has explored some relational strategies, and “misunderstanding strategy” is one of those strategies. “Misunderstanding strategy” is referred to as “deliberate non-understanding”, which is a special type of deliberate misinterpretation. When interlocutors use this strategy, they usually know the meaning of each other, but one of them may pretend not to understand the meaning of his/her interlocutor. By doing so, the speaker may achieve the purpose of breaking off a certain relationship with someone (Fisher, 1987). Dascal applies a misunderstanding strategy. He makes a comparison between standard misunderstanding and non-standard misunderstanding, and according to him, non-standard misunderstanding is a widespread phenomenon in communication, which can be used as a powerful communicative strategy to protect people from others’ intrusion. In Dascal’s opinion, the difference between standard misunderstanding and non-standard misunderstanding lies in the former occurs unexpectedly and involuntarily while the latter often occurs voluntarily and is created on purpose. In other words, in standard cases, language users often try to avoid or minimize the bad effects created by misunderstanding while in the non-standard cases, language users create this phenomenon on purpose (Dascal, 1999).

Previous studies on deliberate misinterpretation have some insufficiencies. Initially, deliberate misinterpretation, as a new topic, hasn’t been paid enough attention to. The existing data are not sufficient which leaves space for continuous replenishment and complementation. Additionally, the systematic knowledge framework is far from perfect. Although more and more fruits have been acquired, the motivation and realization mechanism of deliberate misinterpretation could be further studied. What’s more, there are only a few applications of theories in the studies of deliberate misinterpretation. With a theoretical background to base on, further studies will be more practical and systematic.

Research methodology and analytical framework

This section will give a brief introduction on how data is collected and the framework that is going to be applied to analyze the data.

Data collection and process

The data of the study is collected from the American situation comedy Friends. Data classification requires certain criteria to judge if the linguistic phenomenon belongs to deliberate misinterpretation. The measurements adopted here are the three features of deliberate misinterpretation adopted by Shen (2004), namely, the hearer’s intention, the hearer’s communicative strategy, and the mismatch between the hearer’s interpretation and the speaker’s original meaning. With the video version and the transcripts of the sitcom at hand, conversations containing deliberate misinterpretation are marked and collected.

Both qualitative and quantitative approaches are applied to sort the data. By examining the data, cases of deliberate misinterpretation are initially categorized as concerning semantic meanings and deictic expressions, which complies with the distinction of core common ground and emergent common ground in SCA; core common ground is generally related to the meaning while emergent common ground takes contexts into consideration. In light of Relevance Theory, cases concerning semantic meanings and core common ground are further divided into explicit meanings as propositions and implicit meanings containing figurative usages. According to actual situations, deictic expressions are further divided into discourse deixis, person deixis and place deixis. Quantitative studies of speech seem particularly important to theoretic linguistics. In the study quantitative approach serves as a necessary implementation by providing solid evidence as well as demonstrating the frequency of each category. The occurrence of each case is counted and analyzed.

Analytical framework

Socio-cognitive approach (SCA) bridges the gap between the Gricean approaches based on cooperation and the non-Gricean based on egocentrism and offers a model that dialectically includes both cooperation and egocentrism as always present in human interaction (Ivana, 2019). SCA advocates the integration of cognition and pragmatics, namely individual and social factors, “cooperation” and “egocentrism” are the essential characteristics of the two opposites of communication (Kecskes, 2015). It proposes to construct “speaker-hearer pragmatics”, aiming at constructing a kind of linguistics, which is also an analytical framework that combines a pragmatic top-down approach and a cognitive bottom-up approach (Zhou & Ran, 2012).

Kecskes pointed out that traditional pragmatics theory usually regards communication as a cooperative, context-dependent process, in which the speaker is often conceived as the one who makes the discourse after considering all the contextual factors, and the hearer is conceived as the one who tries to understand the speaker’s intentions as much as possible. In fact, what the speaker intends to express is not always recovered by the hearer, but depends on the pre-context of both parties, especially the pre-individual context, the interaction of intention and attention, and the emergent common ground (Kecskes, 2010). Therefore, SCA is proposed and the elements above are accordingly defined as egocentrism and common ground.

Egocentrism as the root cause

In SCA, egocentrism is “a way of thinking that communicators automatically bring explicit information to the level of attention in the process of discourse output and understanding” (Kecskes, 2010). It is used to describe a certain kind of unconscious tendency of interlocutors of different ages. The concept of “egocentrism” is derived from the description of children’s personalities in Developmental Psychology. It refers to children’s perception of the surrounding world from their own perspectives, focusing on their own perceptions, emotions, and subjective wills (Piaget, 1980). However, “egocentrism” of communication is an objective description of the characteristics of speech act or the mechanism of thinking (Zhou & Ran, 2012).

The ongoing communication despite the deliberate feature of misinterpretation makes the case specific. Unlike some implicit utterances in which the actual intention of the speaker is well hidden, for the utterance that can be utilized to realize deliberate misinterpretation, consensus and common ground are relatively more explicit and easily deduced. That is to say, the ostension part of the speaker is fulfilled and the exact ostension primarily retrieved is generally the expected common ground. Since the common ground has been explicitly pointed out, the speaker may take it for granted and fail to clear the potential ambiguity of the utterance, making the unexpected response possible. Later, the anticipated response is deliberately diverged by the hearer. It has been acknowledged that the interlocutors share the feature of egocentrism, while in deliberate misinterpretation, the egocentrism of the hearer is enhanced and manifested by doing so. The egocentrism here lies in the need of the hearer to accomplish certain communicative goals, and the primary need in the case is to realize humorous effects.

The analytical framework can be constructed as follows. Firstly, the consensus of both parties is reached in the first place. Secondly, egocentrism is manifested on the hearer’s part since it’s the hearer who deliberately breaks the consistency and makes an unexpected response. Thirdly, failure in common ground co-construction is deliberately caused by the hearer to fulfill the need for certain communicative goals. Finally, the utterance has to be potentially ambiguous for the possibility of deliberate misinterpretation. To sum up, the speaker has to create an utterance that is plain and understandable, that is, the common ground and consensus are easy to achieve; the utterance is ambiguous in nature although the clearance of ambiguity may not be generally considered as necessary; the hearer achieves the common ground and gets the meaning at the first place and then deliberately gives an unexpected response to fulfill certain communicative goals.

Common ground as concrete manifestation

Since verbal communication is a process of interaction between interlocutors, egocentrism will inevitably lead to egocentric understandings or perspectives, referred to as “self-cognition” and “self-perspective” (Shen, 2009). Linguistic and pragmatic theories based on L1 assume that language use depends on there being commonalities between language users. These factors create a core common ground on which intention and cooperation-based communication is built (Kecskes, 2021). In SCA, egocentrism issues are viewed from the perspective of common ground. Common ground refers to ‘the sum of all the information that people assume they share,’ (Clark, Brennan, 1991), which seems to be closely related to the notion of ‘context’ in traditional pragmatics. SCA defines common ground as an “assumption”; it points out that common ground is a thinking representation entity that is co-constructed by both parties, but neither party can determine in advance whether the entity exists or not (Zhou & Ran, 2012). In other words, it is difficult for people to conclude what the so-called “I know you know what I know” is, and essentially it is an estimate (Zhou, 2013). SCA also proposes the notion of “common ground”, which is further divided into core common ground and emergent common ground. The former refers to the relatively static and stable general knowledge shared by a specific language community, including encyclopedic knowledge, macro-social cultural knowledge, and linguistic knowledge; the latter refers to relatively dynamic and variable individual knowledge, including “shared sense” and “current sense” among the specific communicative parties. The difference between individual shared information and core common ground is that the sharing category is different; the former is social, and the latter is shared by specific communicators (Zhou & Ran, 2012). That is to say, core common ground is more about individual speakers, while emergent common ground depends on the context and the emerged physical surrounding. It is the consensus of common ground that contributes to successful communication, while the failure in common ground co-construction may collapse the conversation.

Common ground in deliberate misinterpretation is closely related to the ostensive-inferential communication in Relevance Theory. The process of ostensive-inferential communication is defined as follows: The communicator produces a stimulus, which makes it mutually manifest to the communicator and audience that the communicator intends, utilizing this stimulus, to make manifest or more manifest to the audience a set of assumptions (Sperber & Wilson, 1995). What’s more, they define “ostension” as the behavior, which makes manifest an intention to make something manifest, and they argue that ostension provides two layers of information to be picked up: first, there is the information that has been, so to speak, pointed out; second, there is the information that the first layer of information has been intentionally pointed out (Sperber & Wilson, 1995). Standing on the perspective of the speaker, it is the ostension that makes manifest the intended information, and the intended information is the anticipated common ground.

Analysis of deliberate misinterpretation in Friends

By employing the classification criteria and the analytical framework, linguistic data in Friends will be accordingly divided into deliberate misinterpretation of semantic meaning and deliberate misinterpretation of deictic expressions. The classification is also based on the concrete linguistic phenomenon and is made in light of core common ground and emergent common ground proposed in SCA.

Deliberate misinterpretation of semantic meaning

Based on the discussions above, it is sufficient to conclude that the semantic meaning related to the utterance is the concern of core common ground. Based on the data retrieved, further classification as deliberate misinterpretation of propositions and deliberate misinterpretation of implied meaning is made. The former covers the data that the concept is more explicit, with polysemy and homonymy as its representatives; and the latter includes indirect utterance and covert concept, conversational implicature, and figurative language may be included.

In deliberate misinterpretation cases, for propositions, the speaker lays the intended meaning into the core common ground, while the polysemic nature of the utterance is utilized by the hearer; for implied meanings, the speaker may do the similar part while the implied and indirect nature of the utterance is utilized by the hearer to realize the linguistic phenomenon. The concrete examples will be illustrated as below.

Deliberate misinterpretation of propositions

Interlocuters may communicate with each other in an explicit way, but the meaning can be easily deduced based on the utterance. When deliberate misinterpretation is possible, the most frequently seen cases in Friends are related to polysemy and hyponymy. In definition, polysemy refers to situations where a word has different meanings (Saeed, 1997); homonymy refers to situations where two different words have the same meaning or form or both. The conversations that typically manifest deliberate misinterpretations of propositions are as follows.

[Scene: Rachel’s father is a surgeon; he had a heart attack and was sent to a hospital. Ross and Rachel are talking about the incident after they went back from the hospital. To be added, both Ross and Rachel possess a Ph.D. degree.]

Rachel: Yeah, just so weird seeing him like that, you know? I mean he is a doctor, you don’t expect doctors to get sick!

Ross: But we do!

(Episode 1013)

The word “doctor” is a polysemic one which makes the deliberate misinterpretation potentially possible, it may refer to a professional medical practitioner or a person who academically holds a Ph.D. degree. According to Frame Semantics, a frame is any system of concepts related in such a way that to understand any one concept it is necessary to understand the entire system; introducing any one concept results in all of them becoming available (Petruck, 1996). There seem to be two frames available, DOCTOR in HOSPITAL and DOCTOR in UNIVERSITY. Under the circumstance, the general frame is supposed to be the former, where PATIENT goes to the HOSPITAL to see a DOCTOR. In Ross’s response, the attribution of DOCTOR is wrongly placed and the reference of the word has diverged. The polysemic nature and framing strategy are deliberately deployed to humorously ease Rachel’s nerves.

[Scene: Monica and Chandler are having an appointment with Monica’s parents in fifteen minutes. However, Chandler hasn’t changed his clothes yet and he is still talking to the chick and duck at Joey and Rachel’s apartment.]

Monica: (startled) Ahh! Aren’t you dressed yet?

Chandler: (looks down at his clothes) Am I naked again?

(Episode 620)

The term “dress” here is a polysemic one, which includes both “to put on some clothes” and “to wear clothes in a certain manner”. Based on the scene and conversation, it can be deduced that Chandler knows Monica is blaming him for not dressing clothes in a rather official manner, still, Chandler intends to deliberately misinterpret Monica’s utterance and tries to make her less angry in a humorous way. In similar cases, a polysemic term can be regarded as a dialogical unity; on the one hand, a word is intuitively perceived as one single word with lexically more or less the same meaning, but on the other hand, it is a fact that there is semantic variation across situations (Linell, 2006). The polysemy may be inconspicuous, or may be different according to situations; still, the utterance is ambiguous in nature. Deliberate misinterpretation is a situated responsive utterance, and the diverged response is made overt for contribution to the communication.

[Scene: Rachel just broke up with Ross; they are having a fight]

Rachel: No. We are never gonna happen. OK? Accept that.

Ross: Ex…Except, expect that what?

(Episode 214)

“Accept” and “except” are homophones here. Homophones are a specific category of homonymy, referring to words that sound alike or the same but are spelled differently and often have different meanings. According to the context, obviously, the acoustic signal refers to the word “accept”, while Ross exploits the ambiguity caused by homonymy and perceives it as “except”. The purpose of the misinterpretation may be trying to maintain the relationship with Rachel and make the circumstance less awkward.

Deliberate misinterpretation of implicit meaning

Due to various conditions, the speaker may not convey propositions directly, and the meaning is transmitted implicitly. It’s not problematic since the various inferences can be made by the hearer, and the most relevant one can be elected based on the context. However, alternative interpretations may be exploited purposely, the following are typical cases of deliberate misinterpretation of implicit meaning.

[Scene: Rachel has gotten an eye problem but doesn’t know an eye doctor, so Monica suggests Rachel see her doctor. Richard is Monica’s ex-boyfriend, who used to be her eye doctor. However, Monica’s current boyfriend Chandler and Rachel do not know that after they broke up Monica changed to another eye doctor.]

Monica: (To Rachel) Wow! It’s really red! You should go see my eye doctor.

Rachel: Richard? I’m not gonna go see your ex-boyfriend!

Chandler: Oh, Richard! That’s all I ever hear, Richard, Richard, Richard!

Monica: Since we’ve been out, I think I’ve mentioned his name twice!

Chandler: OK, so Richard, Richard!

(Episode 522)

In the example above, the second utterance of Monica seems to be just a narrative sentence. While based on the context and common sense, it’s quite clear that Monica is implicitly complaining about Chandler’s being over-sensitive. Chandler, however, deliberately ignores the intention and response just based on literal meaning, humorously expressing his dissatisfaction with the fact that Monica is still in touch with her ex-boyfriend.

[Scene: The gang is hanging in Ross’s apartment. Chandler is forced to smoke with the window open.]

Joey: (obviously cold) Hey, can you close that window, Chandler? My nipples can cut glass over here!

Phoebe: Really? Mine get me out of tickets.

(Episode 317)

This is an example concerning figurative use of language, here hyperbole is applied in Joey’s utterance, exaggeratedly making a statement to express a strong emotion. Phoebe easily gets Joey’s point that she is quite cold and she wants the window closed, and also the hyperbole concerning nipples. Unlike general response as closing the window, Phoebe comes up with a different hyperbole with the same object “nipples”, turning down the request in an indirect manner. The unexpected response may also lighten the atmosphere and enhance the sense of humor.

Deliberate misinterpretation of deictic expressions

The focus of attention or the perspective is all typical issues belonging to emergent common ground. And deictic expressions are regarded as typical cases. In actual communication, the speaker applies the deixis to refer to a certain object, while the fact is that although the object can be easily deduced by the context, the speaker can never guarantee that the hearer won’t deliberately deduce another one. This circumstance is trickly applied by the hearer to produce an unexpected response.

Fillmore further classified deixis into five categories: person deixis (such as I, she), place deixis (here, there), discourse deixis (that), time deixis (now, today), and social deixis (tu/vous). Based on the linguistic data found in the comedy, the deixis will be mainly classified into discourse deixis, person deixis, and place deixis.

Deliberate misinterpretation of discourse deixis

Discourse deixis is a deixis that encodes a reference to portions of discourse. For example, in the utterance “I am thirsty, that is what she said”, “that” serves as a discourse deixis. Discourse deixis is heavily context-dependent, the alternative interpretations are essential for deliberate misinterpretation, concrete situations will be shown in the following examples.

[Scene: Ross and Rachel are having a baby without marriage. They are now at Mr. and Mrs. Geller’s anniversary party. Mrs. Geller, Ross’s mother, tells Ross and Rachel that she has told their friends that they have got married]

Ross: Dad, so what? We have to pretend that we’re married?

Mr. Geller: Son, I had to shave my ears for tonight. You can do this.

Ross: (to Rachel) Can you believe that?

Rachel: Yeah, if you are going to do the ears, you might as well take a pass at the nasal area.

(Episode 818)

In this example, Ross asks Rachel “Can you believe that?”; the discourse deixis “that” clearly refers to the fact that Ross’s mother has told people that they are getting married. However, Rachel takes advantage of the context and deliberately misinterprets it as referring to Mr. Geller will shave his ears tonight. By doing so, Rachel humorously expresses her thought that telling people the wedding news is a good idea.

[Scene: Ross is telling dinosaur stories to Monica again since he is a paleontologist, but Monica has got tired of them.]

Monica: Oh good, another dinosaur story. When are those gonna be extinct?

Ross: You don’t know dinosaurs have been extinct? You really should have more knowledge.

(Episode 307)

The discourse deixis “those” is generally applied to refer to objects in the previous linguistic contexts. It is wildly known that the dinosaurs have died out for quite a long time, so Monica has attempted to use the dinosaur-related word “extinct” to humorously ask the stories to be stopped. Perhaps Ross feels quite dissatisfied or unpleasant, deliberately ignoring the request by the less likely but possible interpretation to regard “those” as deixis to “dinosaurs”. By doing so, not only the humor is continued, but also the denial and tease of Monica made.

Deliberate misinterpretation of person deixis

Person deixis is applied to refer to a specific person, and in conversation, it can identify the role of the participants, such as the addresser, addressee, and other entities. Here is an example.

[Scene: Phoebe has broken up with her boyfriend Mike because Mike never wants to get married. She has asked Mary to stop her from seeing Mike again. However, Phoebe secretly calls Mike and Mike comes to Phoebe’s apartment. Now, Monica sits between Mike and Phoebe to stop them from connecting emotionally.]

Mike: (to Phoebe) So how’ve you been?

Monica: I’ve been pretty good.

(Episode 917)

“You” is a typical person deixis and is commonly used to refer to a person, and the person being referred to can be easily deduced based on the context. In Mike’s utterance, it’s quite clear that “you” is used to refer to Phoebe, since Mike hasn’t seen Phoebe for some days and wants to know about her. However, Monica deliberately exploits the alternative references of the deixis and responds to Mike as if he was asking her. By doing so, Monica sticks to her job, trying to make sure that Mike and Phoebe won’t connect emotionally.

Deliberate misinterpretation of place deixis

Deictic expressions related to place are good markers of viewpoint. Place deixis encodes spatial locations related to the interlocutors (Jaszczolt, 2002). Here is an example.

[Scene: Ross was very depressed the day before and stayed out all night. Monica and Rachel are quite worried when Ross gets back.]

Monica: Oh my god! (She hugs him and hits him on the shoulder after a short stop.) Where the hell have you been?

Ross: Just, you know, out.

Rachel: Oh, out, oh God, I don’t know why we didn’t think to check there!

(Episode 512)

Here, place deixis “out” provides a basis for deliberate misinterpretation. The word “out” uttered by Ross is used to avoid providing further detailed locations, while Rachel deliberately misinterprets it as somewhere specific to express her blame and dissatisfaction.

Summary and discussions

Classification of deliberate misinterpretation cases is made for an overview of Friends (Zheng, 2010). As the Table 1 shows, most cases fall into the category of propositions, and the polysemy-related cases are most frequently seen; deliberate misinterpretation of deictic expression is relatively rare, especially when it is related to person deixis and place deixis.

Some inferences can be made accordingly. Firstly, most cases are about semantic meaning, the reasons being that the polysemic phenomenon is considerably frequent in the English language, and the tricks based on meaning are relatively more understandable. Secondly, the realization of deliberate misinterpretation concerning deictic expression is not quite easy, one reason may be that the focus of deixis is too easy to deduce and the misinterpretation may seem to be kind of foolish. Thirdly, due to the fact that the expected common ground is retrieved in the first place, the tricks in Friends are relatively plain. This makes the situation comedy more suitable for popularity. Finally, although the concrete communicative goals vary among circumstances, achieving humorous effects seems to be a universal one. That is to say, the deliberate failure in common ground co-construction hasn’t led to the breakdown in communication but unexpectedly makes the conversation smoother and more interesting.

Conclusion

Deliberate misinterpretation, as a frequent linguistic phenomenon, should not only be considered as a specific kind of misunderstanding, but more systemic and thorough studies are in need. Egocentrism and common ground in SCA are adopted in the study to make a comprehensive study. Sperber and Wilson’s relevance theory is also included; the principle of relevance guarantees that the hearer can correctly interpret the speaker’s intention and the speaker can recognize the hearer’s intention of using the specific strategy so as to ensure the ongoing of communication.

Traditional pragmatic theories mainly focus on the cooperation of the interlocuters, so in the circumstances of misunderstandings or deliberate misinterpretations, they are not quite appropriate since the misinterpretation is deliberately caused. What’s more, most of the important theories in traditional pragmatics lay emphasis on one side, mostly the speaker’s side. However, Communication is always concerned with both parties, especially in deliberate misinterpretation, which the hearer should be paid much more attention to. SCA mines those traditional theories and attempts to revise them to better account for various linguistic phenomena. Compared to traditional pragmatics schools which give priority to the hearer, SCA has the advantage of integrating the speaker and hearer as a whole and analyzing both parties respectively. Mainstream linguistics ignores the interlocuter’s ability to infer from and recontextualize specific signals and contextual factors (Linell, 2006). SCA framework of deliberate misinterpretation is under the category of dialogical linguistics, which systematically consider the subjects’ relation to the other in interaction and contexts (Linell, 2006); egocentrism and common ground are highly related to dynamic construal (Croft and Cruse, 2004) of the interplay between meaning potentials and contextual dimensions. Deliberate misinterpretation mostly depends on the “reflective” process of inferencing (Carston, 2005), which is more consciously monitored to make some aspects of logical inferencing overt. Under the SCA framework, deliberate misinterpretation has been accounted for from the perspective of dialogical linguistics.

Based on the analytical framework and the concrete data, the realizing mechanism and indispensable components of deliberate misinterpretation in the sitcom Friends can be concluded as follows. It is sufficient to say that the egocentrism of the hearer is one kernel reason for deliberate misinterpretation since the motive of deliberate misinterpretation is to fulfill certain communicative goals, which are triggered by the hearer’s egocentrism. Moreover, the ambiguous nature of the speaker’s utterance is also indispensable since it makes deliberate misinterpretation potentially possible. In the cases above, the consistent common ground is co-constructed by both parties in the first place, while later the hearer utilizes the potential ambiguity of the utterance and deliberately diverges the interpretation, causing the failure in common ground co-construction to fulfill certain communicative goals. In conversations, the hearer’s response is created based on the utterance of the speaker. Meaning determination is usually done only up to a point or to a degree that is sufficient for current communicative purposes (Garfinkel, 1967). Relating the findings to daily dialogs, if the utterance is not favored or the hearer tends to make face-threatening responses, perhaps a better solution is to make good use of the utterance itself. English has the distinct feature of polysemic, so the understanding is highly dependent on the context and co-text; when associating certain linguistic parts of utterance to a different circumstance, the ambiguous potential can be utilized to make deliberate misinterpretations and to accomplish communicative goals. What’s more, in cases like deliberate misinterpretation, when the common ground has diverged, communication may not break down but smoothen instead; egocentrism, as the thinking mechanism, may be highly dependent on the interlocuter’s needs for certain communicative goals and contexts.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Notes

The authors are indebted to the anonymous reviewer for this point.

References

Carston R (2005) Pragmatic inference-reflective or reflexive? Paper at 9th International Pragmatics Conference. Riva del Garda, Italy, 10–15 July, 2005

Clark H, Brennan S (1991) Grounding in communication. In: Resnick L, J Levine J, Teasley S (eds.). Perspectives on socially shared cognition. Washington: American Psychological Association, Washington

Croft W, Cruse A (2004) Cognitive linguistics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Dascal M (1999) Introduction: some questions about misunderstanding. J Pragmat 1999(31):753–762

Fisher BA (1987) Interpersonal communication: pragmatics of human relationships. Random House, Inc., New York

Garfinkel H (1967) Studies in ethnomethodology. Prentice-Hall, New York

Gumperz JJ (1982) Discourse Strategies. Cambridge UK, CUP

Ivana TM (2019) Skidding on common ground: a socio-cognitive approach to problems in intercultural communicative situations. J Pragmat 151(C):118–127

Jaszczolt KM (2002) Semantics and pragmatics: meaning in language and discourse. Longman, London

Kecskes I (2015) Intercultural Impoliteness. J Pragmat 2015(86):43–47

Kecskes I (2010) The paradox of communication: Socio-cognitive approach to pragmatics. Pragmat Soc 2010(1):50–73

Kecskes I (2021) Intercultural communication and our understanding of language. Languages 222(No. 2):25–42

Keysar B (2008) Egocentric processes in communication and miscommunication. In: Istvan K, Jacob M (eds.). Intention, common ground and the egocentric speaker-hearer. Mouton de Gruyter, 2008:277–296

Linell P (2006) Towards a dialogical linguistics. XII International Bakhtin Conference, 18–22 July, Jyväskylä, Finland. University of Jyväskylä

Lowe JB, Baker CF, CJ Fillmore CJ (1997) A frame-semantic approach to semantic annotation. Proceedings of ACL SIGLEX Workshop on Tagging Text with Lexical Semantics. 1997, 19

Manuel PC (2017) Interlocutors-related and hearer-specific causes of misunderstanding: processing strategy, confirmation bias and weak vigilance. Res Lang 15(1):11–36

Petruck, MRL Frame semantics. Handbook of Pragmatics, 1996

Piaget I (1980) Wu Fuyuan Translated. Child psychology. The Commercial Press,, Beijing

Richard LA (1964) The philosophy of rhetoric. Oxford University Press, London

Saeed JI (1997) Semantics. Blackwell Publisher Itd, Oxford

Schegloff EA (1987) Some sources of misunderstanding in talk-in-interaction. Linguistics, 1987 (25):201–218

Shen J (2009) Subjectivity of Chinese and teaching of Chinese grammar. Chinese Learn 2009(1):3–12

Shen ZQ (2004) Deliberate misinterpretation as a pragmatic strategy in verbal communication. Unpublished D.A. thesis in Guangdong University of Foreign Studies

Sperber D, Wilson D (1995) Relevance: communication and cognition. Blackwell, Oxford

Tannen D (1990) You just don’t understand: women and men in conversation. William Morrow, New York, NY

Taylor TJ (1992) Mutual misunderstanding: scepticism and the theorizing of language and interpretation. Duke University Press

Verdler Z (1994) Understanding misunderstanding. In: Jamieson D (ed.). Language, Mind and Art. Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1994:9–21

Zhou H, Chen D (2019) Understanding misunderstandings from socio-cognitive approach to pragmatics. Int J Lang Linguist 7(5):194–194

Zhou H, Ran Y (2012) A new perspective of social-cognitive pragmatics. Foreign Lang Foreign Lang Teach 2012(4):6–10

Zhou H (2013) Cognitive study of egocentric discourse and its roots. Modern Foreign Lang 2013(1):40–46

Zheng Z (2010) Study on deliberate misinterpretation in Friends based on relevance theory, 2010. Shandong University, MA thesis

Zong S (2003) On the social psychological roots of misunderstanding. Modern Foreign Lang 2003(3):266–274

Zong S On the formation mechanism of misunderstanding. Foreign Lang Teach Res 2005(2):124–131

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Associate Professor Tang Aijun and Professor Xu Haiming at Shanghai International Studies University for their critical advices on the initial draft.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, R., Zhan, H. Deliberate misinterpretation from the perspective of socio-cognitive pragmatics. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 340 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01760-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01760-5