Abstract

Tourism research urgently requires the introduction of new theories to address current issues and challenges. Relative deprivation theory may be the key to effectively explaining the attitudes and behaviours of tourism multistakeholders and resolving tourism conflicts. This study uses CiteSpace to conduct a citation space analysis of relative deprivation theory and draws knowledge mappings to reveal its research foundation, research hotspots, and frontiers to discuss the practical possibility of its application to tourism research. The results show that the research content of relative deprivation theory involves 12 knowledge clusters, including subjective well-being, collective action, socioeconomic inequality, in-group attitudes, and relative deprivation theory, and that its theoretical framework is well suited to the context of tourism research. Tourism-related relative deprivation faces practical challenges and has the potential for theoretical innovation. This study focuses on the perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours of stakeholders and anticipates future research on tourism relative deprivation from the three aspects of multi-interest research subjects, multidimensional research contents, and multiperspective theoretical expansion, which indicate future research directions while revealing the possible innovation of relative deprivation theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Relative deprivation theory is one of the classical theories of social psychology. It refers to the perception that an individual or his or her group is at a disadvantage compared with the reference group, which leads to emotional reactions such as anger, resentment, and a sense of a lack of power (Smith and Pettigrew, 2015). Relative deprivation is generated by social comparison and involves the three psychological processes of cognitive comparison, cognitive evaluation, and the resulting emotions (Smith and Pettigrew, 2015; Smith et al., 2012). Relative deprivation theory can not only effectively explain the psychological effects of disadvantaged groups but also has strong explanatory power and provides insights into the emotions and actions of nondisadvantaged groups. In addition, relative deprivation theory can be integrated with other psychological processes, such as social support (Xie et al., 2018) and social identity (Zagefka et al., 2013; De la sablonniere et al., 2009), to more effectively predict people’s attitudes and behaviours. In recent years, it has been widely used in sociology, criminology, psychology, and other research fields have yielded many qualitative and quantitative research results (Stewart, 2006).

Tourism research involves multiple stakeholders, including tourists, host communities, and tourism practitioners (Liu, 2006). Multilevel interactions between these stakeholders result in the complexity of tourism research situations. Tourism resources are mostly located in underdeveloped and impoverished areas. From generation to generation, indigenous people are inseparable from tourism resources, and tourism resources have become an important component of their productive life. However, tourism development in destinations often separates tourism resources from local communities and treats their production and lifestyle as tourism products without giving them the rights and benefits they deserve, leading to the objective situation in which local communities are often deprived (Bao and Yang, 2022). The flow of tourists from the source to the destination is often the output of economically developed areas to poor areas, and the demonstration effect of tourists can easily cause a sense of relative deprivation among residents (Seaton, 1997). In addition, in the process of tourism destination development and operation, there is a fierce reciprocal game of interests between stakeholders (Yang et al., 2015), and relatively weak stakeholders are likely to feel a sense of relative deprivation. Therefore, relative deprivation is prevalent in tourism destinations due to uneven development opportunities and the unfair distribution of tourism benefits. In particular, in areas where tourism is the leading industry, the problem of relative deprivation caused by tourism development is more prominent (Peng and Wang, 2012). Vulnerable groups who are marginalised or even treated unfairly often have a strong sense of relative deprivation, which can lead to group conflicts (Zhai et al., 2020). Compounding the problem is the fact that it is often not the objectively most disadvantaged groups but rather the objectively relatively advantaged groups that complain the most about tourism development (Pettigrew, 2015).

Relevant studies have shown that the transformation of the objective reality of the uneven distribution of benefits into the subjective perception of relative deprivation is the key to tourism conflicts (Cai et al., 2017). Relative deprivation may be crucial to understanding the attitudes and behaviours of multiple stakeholders regarding the resolution of conflicts in tourist destinations. People’s cognitive judgements depend not only on the current absolute level but also on the relative level generated by social comparison. In many cases, people’s satisfaction does not depend on whether the material conditions of objective life are good or bad but on whether these conditions are “better” or “worse” relative to those of the reference group (Power et al., 2020). Relative deprivation theory emphasises the comparability of people’s cognitive judgements and considers it the basis of their attitudes and social behaviours, which means that the issues caused by relative deprivation in tourism research fields cannot be effectively explained by other theories. However, tourism research lacks due attention to the sense of relative deprivation. There is an urgent need to introduce relative deprivation theory to construct effective explanations that are more relevant to the research reality.

Knowledge mapping has been used by many researchers because it can reveal the relationships between knowledge in a clear and dynamic form. Currently, the main tools for knowledge mapping are CiteSpace, SPSS, Ucinet, and VOSviewer. Among them, CiteSpace knowledge visualisation software is more suitable for studying the evolution of a certain topic, so it has become the most popular tool for knowledge mapping (Chen et al., 2015). Visualisation tools can reveal complex relationships between a large number of research studies via numbers and tables, and have been successfully applied in the field of tourism research (Chen et al., 2022; Qiao et al., 2021; La et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020; Mccabe and Qiao, 2020; Yu et al., 2019).

The study used CiteSpace 5.3R3 citation analysis software to draw the knowledge mapping of relative deprivation theory to reveal its knowledge base, research hotspots, and frontiers and summarise the research framework of relative deprivation. Then, this paper examined the practical possibility of applying relative deprivation theory to tourism research and found that the research framework of relative deprivation theory fits well with tourism research. On this basis, the study continued to explore the future research direction of tourism relative deprivation and the possibility of developing relative deprivation theory.

Literature review

Relative deprivation is an important concept used by the sociologist Stouffer in The American Soldier to explain differences between the attitudes of American soldiers of different classes (Stouffer, 1949). However, Stouffer did not define “relative deprivation” but treated it as an ex-post interpretation. Subsequently, Merton expanded the concept of relative deprivation to the theoretical framework of the reference group and proposed three models of how people choose reference groups (Merton, 2015). Runciman further noted that people need to meet the following four basic conditions to have a sense of relative deprivation: (i) they do not own X, (ii) they are aware that others have X, (iii) they expect to have X, and (iv) this expectation is reasonable and feasible (Runciman, 1966). Gurr suggested in Why People Rebel that the deep-seated reason for the emergence of relative deprivation lies in the inconsistency between people’s perceptions of value expectations and value capabilities (Gurr, 1971). However, most studies argue that relative deprivation arises from social comparison with the reference group and is a subjective psychological feeling originating from people’s judgement and evaluation of their interests relative to the gain or loss of others. As this sense of deprivation is generated by relative comparison, it is called “relative deprivation”(Davis, 1959).

Relative deprivation has been widely used in the sociological, psychological, and criminological research fields. Previous studies have addressed its impacts, which include violent aggression (Zhai et al., 2020; Wang, 2021; Siroky et al., 2020; Greitemeyer and Sagioglou, 2019; Burraston et al., 2018; Greitemeyer and Sagioglou, 2017), health problems (Xia and Ma, 2020; Mishra and Meadows, 2018), and gambling problems (Mishra and Meadows, 2018; Tabri et al., 2017; Callan et al., 2011), as well as the mediators and moderators of the effects of relative deprivation (Xie et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2020; Walker et al., 2015; Smithi et al., 2018), the degree of relative deprivation (Bossert and D’ambrosio, 2020; Ren and Pan, 2016), and its related issues. People are concerned with their status not only relative to the status of others but also relative to their past status or expected future status. Relative deprivation originates not only from the comparison of horizontal reference groups but also from the vertical comparison of the time dimension. According to different classifications, relative deprivation can be divided into horizontal and vertical relative deprivation as well as individual-level and group-level relative deprivation. Horizontal relative deprivation refers to people’s sense of relative deprivation formed by comparison with other reference groups, while the sense of relative deprivation formed by comparison with their past experiences or expected future experiences is called intertemporal relative deprivation (Ceriani and Gigliarano, 2015) or vertical relative deprivation (Wang, 2007). The deprivation generated by individual-level social comparisons is called individual relative deprivation, while the relative deprivation generated by group-level social comparisons is called group relative deprivation (Osborne et al., 2015).

The main reason why relative deprivation has developed into an important social science concept is that people’s social judgements are affected not only by the absolute level, but also by the relative level generated by social comparisons (Pettigrew, 2016). Feelings of relative deprivation arise from competitive social comparisons that occur between individuals and groups, which result in negative differences between what is realistically “earned” and what is justly “deserved” (Meuleman et al., 2020). Being disadvantaged and perceiving it as unfair, which in turn triggers an emotional response related to fairness and justice, is central to people’s experience of relative deprivation (Greitemeyer and Sagioglou, 2019; Feather, 2015). The transition from material inequality to relative deprivation does not happen automatically, and simply recognising that one or one’s group receives less than one deserves does not necessarily lead to conflict or forms of deviant behaviour (Power, 2018). In contrast, the strong emotional components of frustration, dissatisfaction, and resentment generated by feelings of relative deprivation can lead to interpersonal aggression and social conflict more than the perception of the relative inferiority of one or one’s group (Kunst and Obaidi, 2020). In other words, feelings of relative deprivation lead to different behavioural outcomes (such as aggression, avoidance, etc.) by eliciting different emotional responses (such as anger and resentment) (Novakowski and Mishra, 2017). The emotional response to a comparative disadvantage is likely to be a “barometer” for the prediction of behaviour related to relative deprivation (N) (Greitemeyer and Sagioglou, 2019). Relative deprivation seems to spread from person to person, as does aggression, and the experience of relative deprivation affects others with whom it is related (Greitemeyer and Sagioglou, 2019). Overall, relative deprivation emerges from people’s subjective understandings of social, cultural, historical, economic, and legal contexts, and can be used to understand people’s frustrations and their resulting behaviours (Power et al., 2020).

Some scholars in the tourism research field have noticed the phenomenon of relative deprivation in tourism development and have conducted related research. Seaton is considered to be the first scholar who applied relative deprivation theory to study tourism issues. He took Cuba as an example to discuss the phenomenon of relative deprivation among residents caused by the demonstration effect of tourists (Seaton, 1997). In recent years, researchers have gradually recognised the theoretical value and effectiveness of relative deprivation in explaining tourism attitudes and behaviours and have introduced relative deprivation theory for relevant research and discussion (Pan and Yang, 2022; Power et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2021; Liao and He, 2018; Da and Liu, 2019). Although research on tourism relative deprivation involves tourists and host communities, research related to tourists is only at the level of the perception of relative deprivation (Zhai et al., 2020). Comparatively, other studies have paid more attention to the relative deprivation of destination residents, including the perception (Cai et al., 2017; Power et al., 2020; Cai and Cai, 2018), causes and consequences (Zhang et al., 2020), coping styles (Zhang and Zeng, 2019), and influencing mechanism (Xu and Sun, 2020) of relative deprivation as well as attitudes towards tourism under the influence of relative deprivation (Power et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2018; Wang and Peng, 2011).

Nevertheless, research on tourism relative deprivation is still in the stage of trial and exploration, and few empirical studies have used relative deprivation theory as an analytical tool. Previous studies mainly considered relative deprivation as a mediating variable and explored the perception-response result of relative deprivation in tourism. To explain the complex reality in the field of tourism, it is necessary not only to conduct a large number of qualitative and quantitative studies in real tourism contexts but also to further expand and improve relative deprivation theory to enhance its ability to explain complicated and multifaceted tourism phenomena.

Research methodology

Principles of CiteSpace analysis

The CiteSpace software system is an information visualisation software developed by the Chinese scholar Dr. Chen Chaomei. It is mainly used to measure and analyse data from the scientific literature to map knowledge of the development of a scientific field, visualise its information panorama, and identify its key literature, popular research topics and frontier directions (Chen et al., 2014). CiteSpace is mainly based on co-citation theory and the pathfinder algorithm to measure the literature (collection) in a specific field to explore the critical path and knowledge inflection point of the evolution of the discipline. The analysis of the potentially dynamic mechanism of discipline evolution and the exploration of the frontier of discipline development are accomplished through the drawing of a series of visual maps (Zhao, 2012). The main function of CiteSpace is to present and analyse the evolution trend and knowledge correlation status of the frontier of the discipline through visualisation functions such as keyword co-citation, institutional distribution, author cooperation and literature coupling (Li et al., 2017).

The interpretation of knowledge mapping is mainly based on high-betweenness-centrality, high-burst, and high-frequency nodes that occupy an important position in the knowledge network and play a special role in the evolution of the knowledge structure. High-betweenness-centrality papers (indicated in purple) are those that occupy an important position in the structure, i.e., they play an important role in connecting other nodes or several different clusters and represent landmark research results. High-burst papers (indicated in red) refer to those with a sudden increase in citation frequency in the time dimension. Nodes with high frequency indicate that these papers received extra attention in the corresponding time interval and, to some extent, represent the research frontier and hot issues in the discipline, which usually represent a shift in a certain field. High-frequency papers are generally important papers with a foundational role (Chen et al., 2014).

Data collection

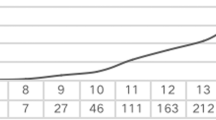

The scientific nature of any knowledge mapping is rooted in the database, and the key issue is determining how to accurately and comprehensively retrieve all the literature on the topic to be studied (Chen et al., 2015). The demand for diversity must be met while ensuring the authority of the data sources. The Web of Science core collection has a strict selection mechanism based on Garfield’s Law of Concentration in bibliometrics and includes only the most important academic journals in each discipline. First, the study searched data with the theme of “relative deprivation” in the Web of Science core collection to ensure the completeness and accuracy of the data. Second, only the “research article” data type was selected for further analysis because of the CiteSpace software itself. Although the research searched the data based on the theme to ensure the completeness and accuracy of the data to the greatest extent, some irrelevant data to the theme were included, so it was necessary to manually review and remove data that were irrelevant to relative deprivation. Then human reviewers went page by page and eliminated data irrelevant to the theme of relative deprivation. After eliminating data, a total of 1509 pieces of valid data were collected. The data were distributed from 1956 to 2018, and the data were obtained in July 2018.

Data analysis

CiteSpace can evaluate the knowledge mapping effect based on two metrics, namely, the module value (the Q value) and the average contour value (Sihouette, i.e., the Si valut). Generally, Q > 0.3 means that the structure of the delineated associations is significant. When the value of Si is 0.7, the clustering is convincingly efficient; if it is above 0.5, the clustering is generally considered reasonable. According to the requirements of software operation and analysis, to ensure the reliability and stability of nodes, the threshold was set to Top50, and the clustering label words were extracted according to the LLR log-likelihood algorithm.

Results

The knowledge base of relative deprivation

The knowledge base of a discipline is the collection of all previous literature corresponding to the research front and its citation and co-citation trajectories in the scientific literature (i.e., the evolutionary network formed by the scientific literature citing the terms of the research front) (Chen, 2009). By analysing the cited references of all the publications in a discipline, the knowledge base of the discipline can be obtained, and the key literature that has contributed significantly to the development of the discipline can be revealed. In CiteSpace, a knowledge base is mainly represented by literature co-citation clustering (Chen et al., 2014). Literature co-citation refers to the phenomenon of the application of two references in the same publication. By analysing the clusters and key nodes in the co-citation network, it is possible to reveal the evolution of the knowledge organisation, research foundation, and literature that plays a key role in the evolution process. In contrast, the timeline diagram is a chronological arrangement of nodes in the same cluster on the same horizontal line, in which the literature is included in each cluster as if it were threaded on a timeline. The focus is placed on sketching the relationships between clusters and the historical span of the literature in a given cluster. The network mapping and timeline mapping of the co-citation clusters of the relative deprivation literature were plotted as presented in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively.

In combination with the timeline plot of the co-citation clusters, the knowledge structure of relative deprivation can be divided into 12 clusters (cluster size not less than 20) with Si values greater than 0.7, indicating that the clustering is efficient and convincing. Consider the largest cluster of “subjective well-being” as an example, which contains 85 nodes with a Si value of 0.863. The closest citation to the cluster is “WHELAN, CT (2010) Welfare regime and social class variation in poverty and economic vulnerability in Europe: an analysis of Eu-Silc. Journal of European Social Policy, V20, P17.” The first reference in the cluster appeared in 2000, and the number of studies began to increase from 2004 onwards. However, after 2014, the research began to cool down and attention decreased, and in recent years, it has received less attention. Throughout the development of the cluster, a high-betweenness-centrality node appeared in 2007, Soc Indic Res) that, occupies an important position in the cluster and is closely related to the “income inequality” cluster and the “dramatic social change” cluster. High-frequency nodes with a foundational role appeared in 2005, 2008, and 2010. High-burst nodes representing the hotspots and research tendencies appeared in 2005 and 2008, which indicates that the research had begun to focus on the “income inequality” cluster. Table 1 presents the details of the top ten most important nodes in the knowledge structure and the evolution of relative deprivation.

Research hotspots and frontiers of relative deprivation theory

A research hotspot is a scientific question or topic addressed by a relatively large number of studies with internal connections within a certain period time. In CiteSpace, term mapping is helpful for the analysis of research hotspots and their changes, especially with the use of the burst term function. A research front is defined as a set of burst dynamic concepts and underlying research questions and represents the current ideological state in a certain research field, reflected by burst terms or the clustering of burst terms in the literature co-citation matrix and cited literature (Chen, 2009). In this study, synonyms were first merged by prerunning CiteSpace to maximise the ability of the software to discriminate between semantic and pragmatic understanding and to improve scientific accuracy. For example, “social inequality” was merged into “social inequalities,” and “individual-based relative deprivation” and “egoistic relative deprivation” were unified into “personal relative deprivation.” The term co-citation network and timeline of the cluster mapping are presented in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively.

From the feature word network mapping and timeline mapping, it can be seen that the relative deprivation terms include those related to mental health, social identity, socioeconomic inequality, reference groups, income inequality, social comparison, etc., which involve social inequality, living standards, theoretical enquiry, and other research topics. To further learn about the research hotspots and frontiers related to relative deprivation, Table 2 reports the top 20 high-frequency terms, high-betweenness-centrality terms, and all high-burst terms that have appeared thus far.

The burst nodes characterising the frontiers of relative deprivation research were found to mainly include social justice, social deprivation, social identity, reference groups, collective action, individual relative deprivation, and relative importance, which involve the factors influencing relative deprivation, the effects of relative deprivation, and the discussion of relative deprivation theory. In other words, the hotspots and frontiers of relative deprivation research include four aspects, the first of which is the discussion of relative deprivation theory, including social comparison and reference groups. The second aspect is the research on the influencing factors of relative deprivation, including social justice, social identity, relative importance, and other basic contents. The third aspect is the measurement of relative deprivation, which mainly includes the relative deprivation model and the relative deprivation index. The final aspect is the effects caused by relative deprivation, which include research on people’s physical health, mental health, subjective well-being, attitudes, and collective action.

Research framework of relative deprivation

Research on relative deprivation theory involves the situation of relative deprivation generation, the generation object, the type of deprivation, the influencing factors, the degree of deprivation and its influencing effects, and the related theoretical discussion, as exhibited in Fig. 5. Further analysis reveals that the social realities of dramatic social change, socioeconomic inequality, and relative poverty contribute to inducing feelings of relative deprivation. At both the individual and group levels, there is a possibility of feeling relative deprivation due to the relative disadvantage of economic, material, and social status. The research on relative deprivation can be divided into two main streams: the first considers relative deprivation as a mediating variable of people’s attitudes, behaviours, and other outcomes, and the second is based on the exploration of relative deprivation theory.

The research on relative deprivation as a mediating variable is mainly concerned with the type, degree, and outcome effects of relative deprivation and its influencing factors. Based on the differences in the generated objects, relative deprivation can be subdivided into individual/group, longitudinal/horizontal, and other corresponding types of relative deprivation or multiple compound relative deprivation. Relative deprivation affects people’s physical health, mental health, group attitudes, collective action, and subjective well-being. The impact on people increases with the level of relative deprivation. The degree of relative deprivation can be measured by the relative deprivation model and relative deprivation index. The type, degree, and outcome effects of relative deprivation are influenced by factors such as age, social identity, social justice, and the relative importance of the deprivation objects. On the other hand, the research on relative deprivation theory includes the causes, conditions, and processes of relative deprivation generation as well as the relevant reference group selection, social comparison, and other related topics.

Prospects of applying relative deprivation theory to tourism research

Relative deprivation research involves social comparisons, reference groups, subjective well-being, socioeconomic inequalities, dramatic social change, collective action, group attitudes, and other relevant themes. The research framework is suitable for studying the real-life situations faced by tourism destinations. In general, in regions and periods with more dramatic changes in socioeconomic transformation, conflicts of interest between social groups increase, economic income gaps widen, social class divisions reorganise, and relative deprivation is more common (Peng and Wang, 2012). Regarding tourism destination development, not only has the original social and economic structure changed, but problems such as unbalanced development and unfair benefits distribution have also emerged; thus, the phenomenon of relative deprivation caused by tourism is very prominent (Pan and Yang, 2022; Power et al., 2020). To further complicate the issue, an interesting phenomenon can often be observed in tourist destinations where those who complain the most about tourism development are often not the objectively most disadvantaged groups but rather the objectively relatively advantaged groups (Pettigrew, 2015). Relative deprivation theory emphasises that people’s cognitive judgements are influenced not only by the absolute level but also by the relative level. Relative deprivation theory is not only applicable to research on the social psychology of disadvantaged groups who are marginalised and disadvantaged due to tourism development but can also provide new insights into the “happiness paradox” and the satisfaction paradox, which cannot be explained by other theories such as social exchange theory and the life cycle of tourism destinations.

The particularity of research on tourism relative deprivation

Although the knowledge map of relative deprivation indicates the direction of research related to tourism relative deprivation, the field of tourism research has its particularities. The research on relative deprivation in the tourism field involves many practical challenges, and it provides the possibility for the innovation and expansion of the relative deprivation theory. The specificity of research on tourism relative deprivation is mainly reflected in the following two points: first, tourism research involves multiple interests that interact with each other; second, tourism destinations, as tourism systems, have their life cycle.

Tourism research involves multiple stakeholders, and there is a fierce dynamic interest game among them. As a comprehensive industry, tourism involves more stakeholders than most other industries (Liu, 2006). It is generally believed that destination residents, tourists, tourism enterprises, and tourism governments constitute the core stakeholder system of a tourism destination. It is argued that the government undertakes the supervision and management of destination development and should not be the core interest game party; rather, it should stand as a third party to administer justice and righteousness to reduce the relative deprivation of stakeholders (Yang et al., 2015). In this study, the government is not considered a stakeholder in the research on tourism relative deprivation. Relative deprivation based on social comparison can never exist in isolation, which means that research on tourism relative deprivation should not only examine the relative deprivation of tourists or destination residents but should also consider the interactive effects of multiple stakeholders. Research on tourism relative deprivation is complicated by the objective difference and subjective demands among the “long-distance nature” of tourists, the “on-site nature” of residents, and the “scene nature” of tourism practitioners in the tourism context.

On the other hand, tourism destinations have their life cycle. Studies related to tourism life cycle theory have noted that destination residents perceive different impacts of tourism development at its different life stages and thus exhibit corresponding attitudes and behaviours (Zhong et al., 2008; Fagence, 2007; Lee and Weaver, 2014; Andriotis, 2006; Kim et al., 2013). As an explanation for and prediction of the attitudes and behaviours of tourism stakeholders, it should also be considered whether there is any relationship between research on tourism relative deprivation and the tourism life cycle stage. Furthermore, researchers should consider whether research on tourism relative deprivation should be conducted in a broader context of reality rather than focusing solely on the relative gains and losses of stakeholders. This question has not yet been explored, but it must be addressed and investigated in depth to understand the current complex reality of tourism destinations.

Prospects of research on tourism relative deprivation

Although tourism research has its particularities, it is still possible to identify the application prospects of relative deprivation theory and the possibility of theoretical expansion in the tourism field based on its knowledge base, hotspots, and frontiers. Research on tourism relative deprivation involves multiple stakeholders, including tourists, tourism practitioners, and destination residents, and covers multidimensional research content such as the generation, perception, response, and effects of relative deprivation. Research on tourism relative deprivation can theoretically expand relative deprivation theory from the perspectives of the generation basis, generation path, and subsequent evolution of relative deprivation, as shown in Fig. 6.

Multi-interest research subjects

First, it is generally believed that tourists leave their usual living environment in pursuit of a better travel experience. However, an exotic travel experience creates a relative disadvantage in terms of destination information and bargaining power for tourism services, which can easily trigger a sense of relative deprivation. Tourists’ sense of relative deprivation not only impacts their travel experience but also profoundly affects their evaluation of tourist destinations and influences the image of the destination through word-of-mouth communication. This, in turn, affects tourists’ willingness to revisit a destination and potential tourists’ destination choice and ultimately affects the sustainable development of the tourism destination. Second, tourism practitioners generally refer to the employees of major tourism enterprises, including culinary, living, travelling, shopping, and entertainment enterprises; these enterprises include both large-scale enterprise groups and small-scale tourism small enterprises. It should be noted that tourism practitioners include not only migrant workers in tourism destinations but also some local community residents, which complicates the relative deprivation of tourism practitioners. The different emotional attachments and ideal expectations of migrant workers in tourism destinations and local community residents lead to differences in tourism service willingness, service costs, and returns. This further leads to differences in the generation of, perceptions of, and responses to relative deprivation and directly affects the quality of tourism services provided to tourists (Balsa et al., 2014). Furthermore, the relative deprivation of host communities affects not only their subjective well-being but also their satisfaction with local tourism development (Munanura et al., 2021; Smith and Huo, 2014). In turn, this affects their attitudes toward tourism development (Power et al., 2020; San et al., 2018) and tourism support behaviours (Lee et al., 2018).

As mentioned previously, research on tourism relative deprivation involves multi-interest research subjects. To solve the current problems related to tourism, research should focus on issues related to tourists, tourism practitioners, and destination residents. Unfortunately, the current research on tourism relative deprivation mainly involves host communities and lacks due attention to tourists and tourism practitioners (Pan and Yang, 2022; Power et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2021; Da and Liu, 2019; Wang et al., 2019). Research on tourism relative deprivation should pay more attention to the related issues of multiple stakeholders. Based on in-depth research on the relative deprivation of each subject, it is necessary to conduct coupling research among destination residents, tourists, and tourism practitioners.

Tourism relative deprivation is centred on the core theme of the perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours of multiple stakeholders and can be combined with tourism destination life cycle theory, stakeholder theory, social exchange theory, and game theory to construct more effective explanations of the sustainable development of tourism destinations. An attempt can be made to explore whether the relative deprivation of tourism stakeholders differs in different life cycle stages of the tourism destination and how stakeholders’ interest game affects their relative deprivation. Future researchers can also explore how relative deprivation theory and social exchange theory interact with each other as well as the influences of relative deprivation theory and life cycle theory on the sustainable development of tourism and other related topics.

Multidimensional research content

As seen from the relative deprivation knowledge map, research on tourism relative deprivation involves multidimensional research content. Relative deprivation can be divided into not only individual and group categories, but also vertical and horizontal. Each type of relative deprivation involves influencing factors, a degree of deprivation, and effects. In general, studies tend to consider relative deprivation a mediating variable to explore its effects on subjective well-being, group attitudes, and collective action. However, because tourism research involves multiple subjects of interest and because tourism destinations have their life cycles, the treatment of relative deprivation as a mediating variable is not only unfavourable to explaining real tourism problems but also limits the possibility of expanding the application of relative deprivation theory.

Relative deprivation, as a subjective feeling, emphasises the comparative nature of human cognition and uses it as a basis for understanding emotions and social actions (Power et al., 2020). Following the response logic of the generation, perception, response, and outcome of people’s sense of relative deprivation and based on distinguishing multiple stakeholders, research on tourism relative deprivation can be divided into four major themes. The first theme is the generation of relative deprivation, which involves the generation situation, path, and mechanism of relative deprivation. The second theme is the perception of relative deprivation, involving the sources, types and conditions of relative deprivation. The third theme is the response to relative deprivation, which mainly explores the degree of deprivation, coping styles and effects. The final theme is the effect of relative deprivation, which mainly considers the impact of relative deprivation on the research subject, including physical and mental health, subjective well-being, and emotional attitudes and behaviours. Owing to the lack of related research on tourism relative deprivation, qualitative research methods such as grounded theory, ethnography, and case studies can be used to collect data from the field to integrate relevant theories and improve the relevant research content.

Multiperspective theoretical expansion

The complex realities faced in tourism research offer the possibility of expanding relative deprivation theory. As mentioned previously, previous research has mainly regarded relative deprivation as a mediating variable to explore its effects. Few studies have considered the generation of relative deprivation, which provides the possibility to expand relative deprivation theory from multiple perspectives. For example, host communities are affected not only by the social and economic changes brought about by local tourism development but also by real situations such as unbalanced tourism development, unequal participation opportunities, and the unfair distribution of tourism benefits. Complex life scenarios may prompt destination residents to choose various reference groups and conduct multidimensional social comparisons. The uncertainty of their reference group selection and the complexity of their social comparisons introduce realistic challenges to the study of tourism relative deprivation while also providing a practical basis for theoretical exploration. The extant research on relative deprivation theory has achieved some results, but in the complex context of tourism, research can further consider whether the basis of relative deprivation generation varies from person to person, whether the paths of generation are the same, and how the sense of relative deprivation is developed after it is generated. Attention to the generation basis, generation path, and subsequent evolution of relative deprivation will realise the multiperspective expansion of its theory.

First, the basis of relative deprivation involves reference group selection and social comparison, but little attention has been given to these factors. People’s dependence on reference groups and their selection habits are not the same, and there are differences in their desire and tendency to compare. Unfortunately, the foundation of relative deprivation has not been explored in depth in previous research. As a result, it is not possible to clarify either the real process of people’s choice of reference groups in changing real-life situations or how people’s sense of relative deprivation is generated by various types of comparison (Power et al., 2020). Although reference group theory and social comparison theory can provide some research insights, the sense of relative deprivation is based on social comparison, and it is necessary to more deeply explore its generation foundation in the tourism context.

Second, the generation process and path of relative deprivation require further exploration. It is generally believed that upwards social comparisons generate relative deprivation, while downward comparisons tend to generate relative satisfaction. Interestingly, people’s downward social comparisons also generate relative deprivation, while upwards comparisons do not generate relative deprivation as much as expected. In other words, even when people are at a comparative disadvantage, they do not necessarily feel relatively deprived. It can be inferred that certain conditions are required for the generation of relative deprivation. The generation of relative deprivation is likely to be influenced by people’s sensitivity to their current environment and their tolerance for comparative differences. In addition, people’s subjective interpretations of their relative disadvantage deeply affect their cognition, and the subjective differences in their cognition further lead to differences in the paths of relative deprivation generation. In other words, the dominant differences between people’s rational and emotional perceptions are likely to lead to differences in the paths by which relative deprivation is generated.

Third, it is unknown whether the sense of relative deprivation, as a subjective feeling, always exists steadily or whether it is just an immediate reaction. Other questions that require further exploration include whether relative deprivation exists in stages or the long term, how relative deprivation changes when people adopt different coping styles, and whether people’s sense of relative deprivation tends to accumulate or diminish over time.

Finally, people are becoming increasingly interested in the antipode of relative deprivation, namely, relative gratification (Smith and Pettigrew, 2015). Relative gratification can be considered a complementary component of relative deprivation that can enrich relative deprivation theory research. In the tourism context, community residents or tourists often experience some degree of relative gratification or relative superiority because they occupy a certain aspect of relative advantage, which introduces a relatively new type of relative deprivation to other community residents or tourists. It is suggested that an in-depth study of the relationship between relative deprivation and relative gratification in the tourism context has the potential to expand the relative deprivation theory. Furthermore, research on tourism relative deprivation can be cross-applied with the more widely used social exchange theory, tourism destination life cycle theory, and game theory to explore more possibilities for theoretical innovation.

Conclusion and recommendations

Theories commonly used in tourism to explain attitudes and behaviours include social exchange theory, social representation theory, social carrying capacity theory, Doxey’s stimulation index theory, tourism life cycle theory, Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs theory, growth machine theory, and tourism dependence theory. Although all these theories can partially explain the attitudes and behaviours of tourism residents, some problems in tourism cannot be effectively explained by these theories, such as the “happiness paradox” of tourism destination residents and the question of why objectively advantaged tourism residents do not exhibit higher tourism satisfaction while objectively less advantaged tourism residents do exhibit higher tourism satisfaction. Relative deprivation theory is widely used because of its validity in explaining people’s attitudes and behaviours. Therefore, it is necessary to introduce the relative deprivation theory to provide more effective explanations.

In addition, there is a widespread phenomenon of relative deprivation in tourist destinations, and residents and tourists in tourist destinations feel a sense of relative deprivation. Relative deprivation seriously affects people’s attitudes and behaviours, but little attention has been given to this issue in the field of tourism research. That is, relative deprivation in the field of tourism research generally exists in reality, and it affects the attitudes and behaviours of residents and tourists. However, related issues cannot be effectively explained by other theories, so it is urgent to introduce the theory of relative deprivation to conduct in-depth discussions of the above issues. Each theory has its range of research applicability. This study suggests that the introduction of relative deprivation theory to discuss the attitudes and behaviours of tourism stakeholders promotes the possibility of better understanding the complex tourism reality.

In short, this study makes three main contributions. First, CiteSpace software was used to draw the knowledge mapping of relative deprivation theory, which revealed its knowledge base, research hotspots and frontiers and constructed the research framework of relative deprivation theory. Second, this study found that the knowledge system of relative deprivation theory can match the tourism research situation. Based on the research framework of relative deprivation theory and the particularity of tourism research, the study noted the direction of the application of relative deprivation theory in tourism research about multiple interest subjects and multidimensional research content. Third, this study showed that research on tourism relative deprivation may promote the development of relative deprivation theory from multiple perspectives. The concept of relative deprivation has long been regarded as an explanatory variable, and few studies have paid attention to the development of this theory. However, the complexity and particularity of tourism research provide the possibility for the development of relative deprivation theory. For example, through the study of people’s reference choices and social comparison, the basis for the generation of relative deprivation may be expanded, and an in-depth discussion of the conditions that generate relative deprivation may reveal whether there are differences in the generation paths of people’s relative deprivation.

Note that tourism research not only involves multi-interest research subjects such as tourists, tourism practitioners, and destination residents, but must also consider the frequent interaction and intense interest games among stakeholders. In addition, tourism has an inevitable life cycle, and different stages of the life cycle cause differences in the attitudes and behaviours of stakeholders. Thus, it is necessary to discuss the relationship between relative deprivation and the destination life cycle, which increases the complexity of research on tourism relative deprivation. In addition, relative deprivation theory may be cross-fertilised with stakeholder theory, game theory and tourism destination life cycle theory to provide more powerful explanations, which may lead to new theoretical achievements.

The study is also characterised by some shortcomings. First, the interpretation of CiteSpace knowledge mapping is limited by personal subjective judgement and knowledge accumulation, and there may have been some omissions in the interpretation. Second, the operation of CiteSpace is limited by the algorithm and function of the software to extract and analyse information, and important literature with a short publication time may have been ignored. In addition, tourism research involves many research contents and classical theories, and this study considered only research on tourism relative deprivation at a broad level. Even though some crucial studies on relative deprivation theory may have been overlooked, this study nevertheless constitutes a worthwhile effort. Subsequent research will focus on topics related to tourism relative deprivation to expand relative deprivation theory while working to solve practical problems encountered in tourism research.

Data availability

Data can be provided on reasonable request for academic purposes only.

References

Andriotis K (2006) The tourism area life cycle. Ann Tour Res 33(4):1176–1178

Balsa AI, French MT, Regan TL (2014) Relative deprivation and risky behaviors. J Hum Resour 49(2):446–471

Bao JG, Yang B (2022) Institutionalization and practices of the “rights to tourist attractions” (RTA) in “Azheke Plan”: a field study of tourism development and poverty reduction. Tour Tribune 37(1):18–31

Bossert W, D’ambrosio C (2020) Losing ground in the income hierarchy: Relative deprivation revisited. J Econ Inequal 18(1):1–12

Burraston B, Mccutcheon JC, Watts SJ (2018) Relative and absolute deprivation’s relationship with violent crime in the United States: testing an interaction effect between income inequality and disadvantage. Crime Delinq 64(4):542–560

Cai KX, Cai Y (2018) Residents’ classification in tourist destination based on relative deprivation theory: a case study of Xijiang Miao scenic area. J Sichuan Normal Univ (Social Science Edition) 45(2):84–91

Cai KX, Pan JY, He H (2017) Interest, power and institutions: on genetic mechanism for tourism social conflict. J Sichuan Normal Univy (Social Science Edition) 44(1):48–55

Callan MJ, Shead NW, Olson JM (2011) Personal relative deprivation, delay discounting, and gambling. J Pers Soc Psychol 101(5):955–973

Ceriani L, Gigliarano C (2015) An inter-temporal relative deprivation index. Soc Indic Res 124(2):427–443

Chen CM (2009) CiteSpace II:detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J China Soc Sci Tech Inform 28(3):401–421

Chen N, Hsu CHC, Li X (2018) Feeling superior or deprived? Attitudes and underlying mentalities of residents towards mainland Chinese tourists. Tour Manag 66:94–107

Chen Y, Chen CM, Hu ZG, Wang XW (2014) Principles and applications of analyzing a citation space. Science Press, Beijing, pp. 14–15

Chen Y, Chen CM, Liu ZY, Hu ZG, Wang XW (2015) The methodology function of CiteSpace mapping knowledge domains. Stud Sci Sci 33(2):242–253

Chen SR, Tian D, Law R, Zhang M (2022) Bibliometric and visualized review of smart tourism research. Int J Tour Res 24(2):298–307

Da L, Liu XY (2019) Study on rural tourism poverty alleviation from relative deprivation perspective: taking Xingyi Wanfenglin community of Guizhou province as example. Areal Res Dev 38(2):124–128

Davis JA (1959) A formal interpretation of the theory of relative deprivation. Sociometry 22(4):280–296

De la sablonniere R, Tougas F, Lortie-lussier M (2009) Dramatic social change in Russia and Mongolia connecting relative deprivation to social identity. J Cross-Cult Psychol 40(3):327–348

Fagence M (2007) The tourism area life cycle. Tour Manag 28(6):1574–1575

Feather NT (2015) Analyzing relative deprivation in relation to deservingness, entitlement and resentment. Soc Just Res 28(1):7–26

Greitemeyer T, Sagioglou C (2019) The impact of personal relative deprivation on aggression over time. J Soc Psychol 159(6):664–675

Greitemeyer T, Sagioglou C (2019) The experience of deprivation: does relative more than absolute status predict hostility? Br J Soc Psychol 58(3):515–533

Greitemeyer T, Sagioglou C (2017) Increasing wealth inequality may increase interpersonal hostility: the relationship between personal relative deprivation and aggression. J Soc Psychol 157(6):766–776

Gurr TR (1971) Why men rebel. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey

Kim K, Uysal M, Sirgy MJ (2013) How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour Manag 36:527–540

Kunst JR, Obaidi M (2020) Understanding violent extremism in the 21st century: the (re)emerging role of relative deprivation. Curr Opin Psychol 35:55–59

La LQ, Xu FF, Buhalis D (2021) Knowledge mapping of sharing accommodation: a bibliometric analysis. Tour Manag Perspect 40:100897

Lee Y, Weaver D (2014) The tourism area life cycle in Kim Yujeong literary village, Korea. Asia Pac J Tour Res 19(2):181–198

Lee CK, Kim JS, Susanna J (2018) Impact of a gaming company’s CSR on residents’ perceived benefits, quality of life, and support. Tour Manag 64:281–290

Liao WJ, He YS (2018) How does the uncivilized behavior of tourists form in unusual environment. J Arid Land Resour Environ 32(6):194–201

Li BH, Luo Q, Liu PL (2017) Knowledge maps analysis of traditional villages research in Chinabased on the citespace method. Econ Geogr 37(9):207–214

Liu JY (2006) Viewing the structure relationship among ecotourism stakeholders from the perspective of systematology. Tour Tribune 5:17–21

Mccabe S, Qiao G (2020) A review of research into social tourism: launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on social tourism. Ann Tour Res 85:103103

Merton RK (2015) Social theory and social structure. Yilin Press, Nanjing

Meuleman B, Abts K, Schmidt P, Pettigrew TF, Davidov E (2020) Economic conditions, group relative deprivation and ethnic threat perceptions: a cross-national perspective. J Ethn Migr Stud 46(3):593–611

Mishra S, Meadows TJS (2018) Does stress mediate the association between personal relative deprivation and gambling. Stress Health 34(2):331–337

Munanura IE, Needham MD, Lindberg K, Kooistra C, Ghahramani L (2021) Support for tourism: the roles of attitudes, subjective wellbeing, and emotional solidarity. J Sustain Tour. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1901104

Novakowski D, Mishra S (2017) Relative state, social comparison reactions, and the behavioral constellation of deprivation. Behav Brain Sci 40:e335. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X17001054

Osborne D, Sibley CG, Huo YJ, Smith H (2015) Doubling-down on deprivation: Using latent profile analysis to evaluate an age-old assumption in relative deprivation theory. Eur J Soc Psychol 45(4):482–495

Pettigrew TF (2016) In pursuit of three theories: authoritarianism, relative deprivation, and intergroup contact. Ann Rev Psychol 67:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033327

Peng J, Wang J (2012) A comparative analysis of the three social psychological perspectives in tourism research. Tour Sci 26(2):1–9, 28

Power SA (2018) The deprivation-protest paradox: How the perception of unfair economic inequality leads to civic unrest. Curr Anthropol 59(6):765–789

Power SA, Madsen T, Morton TA (2020) Relative deprivation and revolt: current and future directions. Curr Opin Psychol 35:119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.06.010

Pan JY, Yang ZZ (2022) Research on the generation mechanism of relative deprivation among tourism destination residents. J Southwest MinZu Univ (Humanit Soc Sci) 43(8):50–57

Power SA, Madsen T, Morton TA (2020) Relative deprivation and revolt: current and future directions. Curr Opin Psychol 35:119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.06.010

Pettigrew TF (2015) Samuel Stouffer and relative deprivation. Soc Psychol Q 78(1):7–24

Power SA, Madsen T, Morton TA (2020) Relative deprivation and revolt: Current and future directions. Curr Opin Psychol 35:119–124

Qiao GH, Ding L, Zhang LL, Yan HL (2021) Accessible tourism: a bibliometric review (2008-2020) Tour Rev https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-12-2020-0619

Ren GQ, Pan XL (2016) An individual relative deprivation index and its curve considering income scope. Soc Indicat Res 126(3):935–953

Runciman GW (1966) Relative deprivation and social justice: a study of attitudes to social inequality in twentieth-century England [M]. University of California Press, Berkeley

Smith HJ, Pettigrew TF (2015) Advances in relative deprivation theory and research. Soc Just Res 28(1):1–6

Smith HJ, Pettigrew TF, Pippin GM, Bialosiewicz S (2012) Relative deprivation: a theoretical and meta-analytic review. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 16(3):203–232

Stewart QT (2006) Reinvigorating relative deprivation: a new measure for a classic concept. Soc Sci Res 35(3):779–802

Smith HJ, Huo YJ (2014) Relative deprivation: how subjective experiences of inequality influence social behavior and health. Health Well-being 1(1):231–238

San martin H, Sanchez M, Herrero A (2018) Residents’ attitudes and behavioural support for tourism in host communities. J Travel Tour Mark 35(2):231–243

Seaton AV (1997) Demonstration effects or relative deprivation? The counter revolutionary pressures of tourism in Cuba. Prog Tour Hospit Res 3(4):307–320

Siroky D, Warner CM, Filip-crawford G, Berlin A, Neuberg SL (2020) Grievances and rebellion: comparing relative deprivation and horizontal inequality. Confl Manag Peace Sci 37(6):694–715

Smithi HJ, Ryan DA, Jaurique A, Pettigrew TF (2018) Cultural values moderate the impact of relative deprivation. J Cross-Cult Psychol 49(8):1183–1218

Stouffer SA (1949) The American soldier. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey

Tabri N, Shead N, Wohl M (2017) Me, myself, and money: relative deprivation predicts disordered gambling severity via delay discounting, especially among gamblers who have a financially focused self-concept. J Gambl Stud 33(4):1–11

Tang WY, Gong JJ, Zhao DP (2021) Relative deprivation of community residents in tourist destination: a review. Hum Geogr 36(6):19–27

Walker I, Leviston Z, Price J, Devine-wright P (2015) Responses to a worsening environment: relative deprivation mediates between place attachments and behaviour. Eur J Soc Psychol 45(7):833–846

Wang LG (2021) Causal analysis of conflict in tourism in rural China: the peasant perspective. Tour Manag Perspect 39:100863

Wang N (2007) Relative deprivation: a case of the retired urban eldersʾ experience on medical security system. J Northwest Normal Univ (Social Sciences) 44(4):19–25. https://doi.org/10.16783/j.cnki.nwnus.2007.04.005

Wang J, Peng J (2011) Study on the altitude of host community based on the relative deprivation theory: a case study of the Maolan nature reserve. Ecol Econ 34-40(2):49

Wang WH, Bai B, Zhang Y (2019) A relative deprivation analysis on the host resistance towards tourism in rural destinations: case from Wuyuan, China. Sci Geogr Sin 39(11):1814–1821. https://doi.org/10.13249/j.cnki.sgs

Xia Y, Ma Z (2020) Relative deprivation, social exclusion, and quality of life among Chinese internal migrants. Public Health 186:129–136

Xie XW, Wang YH, Zhao PC, Lei FQ (2018) Basic psychological needs satisfaction and fear of missing out: friend support moderated the mediating effect of individual relative deprivation. Psychiatry Res 268:223–228

Xu ZC, Sun BD (2020) Influential mechanism of farmers’ sense of relative deprivation in the sustainable development of rural tourism. J Sustain Tour 28(1):110–128

Yang ZZ, Shi H, Yang D, Cai Y, Ren X (2015) Analysis of core stakeholder behaviour in the tourism community using economic game theory. Tour Econ 21(6):1169–1187

Yu L, Wang G, Marcouiller DW (2019) A scientometric review of pro-poor tourism research: visualization and analysis. Tour Manag Perspect 30:75–88

Yu GL, Zhao FQ, Wang H, Li S (2020) Subjective social class and distrust among chinese college students: the mediating roles of relative deprivation and belief in a just world. Curr Psychol 39(6):2221–2230

Zagefka H, Binder J, Brown R, Hancock L (2013) Who is to blame? The relationship between ingroup identification and relative deprivation is moderated by ingroup attributions. Soc Psychol 2013 44(6):398–407

Zhai X, Luo Q, Long W (2020) Why tourists engage in online collective actions in times of crisis: exploring the role of group relative deprivation. J Dest Mark Manag 16:100414

Zhao DQ (2012) Discussion on some problems of scientific mapping knowledge domains based on CiteSpace. Inform Stud Theory Appl 35(10):56–58

Zhang CY, Wang SY, Sun SL, Wei YJ (2020) Knowledge mapping of tourism demand forecasting research. Tour Manag Perspect 35:100715

Zhang DZ, Ma QF, Zhao ZB (2020) A study on the cause and effect variables of relative deprivation of rural tourism residents: an individual-based psychological perspective. Hum Geogr 35(4):32–39, 98

Zhang DZ, Zeng L (2019) Theoretical model of reaction mechanism for residents’ relative deprivation in tourist destinations. Tour Tribune 34(2):29–36

Zhong LS, Deng JY, Xiang BH (2008) Tourism development and the tourism area life-cycle model: a case study of Zhangjiajie National Forest Park, China. Tour Manag 29(5):841–856

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, J., Yang, Z. Knowledge mapping of relative deprivation theory and its applicability in tourism research. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 68 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01520-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01520-5