Abstract

This study assesses the quality of a Master’s Degree in education in Ecuador, a program delivered jointly by three institutions (the Ecuadorian Ministry of Education, the National Education University of Ecuador and the University of Barcelona) from 2017 to 2019. The study adopts a multi-dimensional definition of quality that encompasses organization, teaching and trainees’ satisfaction with the value of the course for their professional development. A survey was conducted among 308 trainee teachers using an online questionnaire featuring both open and closed questions. The descriptive analysis of the variables was performed with SPSS and the qualitative information was analyzed using Nvivo12. The findings showed evidence of quality in organization, administration and teaching, in addition to trainee satisfaction with the personal and professional benefits of the course. The study concludes with recommendations for adapting the pedagogical and didactic contents of the master’s degree to the Ecuadorian context and modifying the organization of the face-to-face phase. Evidence is also offered of the value of blended learning and suggestions are made for ongoing institutional self-evaluation to ensure continued improvements and internal regulation in Ecuadorian higher education, and to further develop the government’s Good Living program.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Teacher training and innovation programs are designed to enhance educational quality in its broadest sense. To that end, appropriate curriculum models, contents, and competencies are set in place. These are obliged to meet the requirements of the surrounding society in order to ensure the highest possible quality. The objective of this study was to provide evidence of the quality of the Master’s Degree in Education and Educational Guidance, the Master’s Degree in the Pedagogy of Language and Literature, the Master’s Degree in the Pedagogy of History and the Social Sciences and the Master’s Degree in the Pedagogy of the Experimental Sciences (Mathematics) at the National University of Education of Ecuador (UNAE), delivered jointly with the Ecuadorian Ministry of Education (MINEDUC) and the University of Barcelona (UB) from 2017 to 2019. Participants comprised 458 Ecuadorian in-service teachers chosen by the MINEDUC, plus 70 teachers from the UB and 19 from the UNAE. The master’s degrees were delivered in a blended mode, combining study in the UB Open Virtual Campus and face-to-face sessions in Ecuador (noteFootnote 1).

In 2014 the Ecuadorian government prioritized the transformation of the country’s education system at all levels. Two particular initiatives were emphasized. The first was the creation of four flagship free public universities that would conform to international quality standards. The UNAE is one of these. The second was a government call to develop the First Pilot Blended Training Program for Ecuadorian Secondary Education Teachers in collaboration with Spanish universities with proven experience in training secondary education teachers. The UB was one of the universities chosen to participate in training 345 Ecuadorian teachers. The other Spanish universities taking part were the Autonomous University of Madrid, the UNED (National University of Distance Education), and the Complutense University of Madrid. The Spanish universities were coordinated by the Spanish Service for the Internationalization of Education (SEPIE in its Spanish initials), which was responsible for liaising with MINEDUC. The program was interrupted for a number of reasons and a second edition was not delivered.

A further important feature of the Ecuadorian context is the paradigm shift the country undertook with the coining of the term Buen Vivir (Good Living), a translation into political terms of the Kiwcha expression Sumak Kawsay. This concept, originating from the ancestral worldview and practices of the indigenous peoples of the Andes and Ecuadorian Amazon, centers on the human being as an integral part of the natural and social environment. It also aims to offer an alternative to the crisis caused by the neoliberal model of development, imposed from abroad. Ecuador was the first country in Latin America to break with this model and return to its own traditions, developing and applying the notion of Good Living as a means of carrying through this major reorientation. The approach was institutionalized in two main forms. The first was the inclusion of the principles of Good Living in the 2008 Constitution, and the second was the National Plan for Good Living (NPGL) 2009–2013 to 2013–2017, an instrument giving the concept practical shape through strategic policy guidelines and the articulation of nationwide goals and mechanisms (Cuestas-Caza and Góngora-Almeida, 2014).

Buen Vivir is expressed in education in two ways. Firstly, the right to education is an essential component of Good Living, since proper schooling develops human potential and therefore ensures equal opportunities for all. Secondly, Good Living is seen as a keystone of education, as the process of learning equips future citizens with the knowledge and values they need to contribute to national development (Gobierno de Ecuador-Secretaría Nacional de Planificación y Desarrollo, 2009).

In 2016, MINEDUC introduced curriculum changes that sought to improve learning opportunities for all the country’s students in the framework of a project that would promote full personal development and integration into a society governed by the principles of Good Living, democratic participation and harmonious coexistence (Gobierno de Ecuador-MINEDUC, 2016). As part of this initiative, MINEDUC signed an agreement with the UB to deliver Master’s Degrees in Education programs in the four specializations mentioned above. This agreement included the option of obtaining a double degree. The first degree, the Master’s Degree in Education plus one of the recognized specializations, was awarded by the UNAE, in close collaboration with the UB, in the 2017–2018 academic year. After obtaining this qualification, trainees could then opt to continue to the Master’s Degree in Secondary Education at the UB (MFPESE-UB) in the 2019 academic year. This article presents an analysis of the quality of these two degrees.

The main objective of the UNAE Master’s Degree in Education was to contribute to Ecuadorian teachers’ professional development via a specialized four-level training course designed to equip them with high-quality performance strategies to respond to a wide range of issues arising in the classroom and in schools in general (UNESCO, 2016). The Master’s Degree comprised three modules: (1) Social, Psychological and Pedagogical Foundations (5 subjects, 725 h); (2) Professionalization and Specialization (7 subjects, 1015 h); and (3) Research and Innovation (2 subjects and the Tutorial Action Plan, 440 h). A total of 458 Students were enrolled in the program, Language and Literature being the specialization with the highest number of students (155), followed by Educational Guidance (131), Mathematics (102) and History and Social Science (70). 99.3% of students passed the final exams.

In January 2019 the process for obtaining the double qualification was set up in an online format at the UB. 366 students enrolled and had to complete a newly designed end-of-degree project since the rest of the subjects were already ratified.

The purpose of this article is to provide evidence of the quality of this course. In the following section, we discuss the concept of quality in higher education adopted for this purpose, as well as the dimensions and measures of our analysis.

Quality in higher education: concept and dimensions

The term “quality” shifts its meaning depending on whether the focus is on the actor, the process, or the products. It is also related to the concepts of exceptionality, perfection, excellence, the achievement of challenges and standards, and transformation (Harvey and Green, 1993). For this reason, and in light of the abundant literature on the subject, it is important, to begin with, an account of the meaning of the concept in its broadest sense (Ball, 1985; Harvey and Green, 1993; Schindler et al., 2015).

Centering our attention specifically on quality in higher education, universities are required to design and deliver action plans (Guzman and Torres, 2004) that are governed by efficacy, efficiency, and excellence (Arranz, 2007) and strive to achieve significant learning outcomes while also providing equal access to knowledge (Tedesco, 2009). The major challenge for quality in university education is the adaptation of programs to our contemporary globalized information society (Temponi, 2005). The function of these programs is to contribute to citizen development by fostering democratic and critical attitudes that favor social transformation, inclusion (Harvey and Burrows, 1992), and economic progress (Bertolini, 2017). In this light, the concept of quality in higher education is a transformative agent that promotes the empowerment of students (Harvey and Burrows, 1992), encouraging them to reflect on their educational process (Wiggins, 1990).

Interest in this concept arose in the 1950s in the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA), which assessed educational actors, programs, institutions and systems, bringing valid, reliable information to bear in comparative analyses of the effects of education policies (Jornet et al., 2017). Thus, it is not a new notion; however, concern for quality development has spread in recent years through Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) requirements for accountability and control in public spending, the OECD Program for International Student Assessment, and the Latin-American Laboratory for the Assessment of Quality in Education, amongst other factors (De la Orden and Jornet, 2012).

The first issue we should address here is the definition of quality in higher education, since, according to Schindler et al. (2015) and Welzant et al. (2015), it combines two essential areas. The first focuses on external aspects or factors, i.e., the process of development and improvement in organization and institutions (autonomy, transparency, and effectiveness), while the second pays attention to internal aspects or factors, i.e., teachers, staff, professional development (Mullins, 1973; Sahney et al., 2010; Ferreira and Bueno, 2019) and resources (e.g., individual transformation; Gvaramadze, 2008). Quality in teaching is associated with practical training initiatives that develop educators’ knowledge, competencies, and skills and have immediate results in the classroom, addressing methodology and innovation (Castilla, 2011). Vizcarro (2003) listed a series of aspects of quality in teaching: course content, the features of in-class presentations, course management, teaching outside the classroom, the quality of learning, teachers’ professional and critical attitudes, and innovation. To complement this, some scholars have focused on the intrinsic relationship between the management of quality and improvements in performance and satisfaction (Sakthivel et al., 2005; Castilla, 2011). In higher education institutions where student opinions on the quality of courses have been surveyed, higher levels of satisfaction have been found.

In brief, then, for the purposes of this study, we base the concept of quality in higher education on three main areas: organizational or external quality; internal or teaching quality; and trainee satisfaction with the professional development outcomes of the course.

The concern for quality has led institutions and organizations, both public and private, to assess their programs (Esquivel, 2007; Valenzuela et al., 2011; González et al., 2011; Rodríguez and Hernández-Vázquez, 2020) in order to develop and improve them and to promote accountability and transparency in decision-making. In this context, assessment is defined as a systematic process of investigation and understanding of an educational initiative that aims to appraise its merit or value and is oriented toward further decision-making (Ruiz-Bueno, 2011; Cano, 2016; Jornet et al., 2017).

Educational assessment has traditionally confined itself to teaching–learning activities and the educator’s own perceptions (Cano, 2016). More recent studies, however, have also scrutinized the effectiveness of education and its transfer (Feixas et al., 2015). These studies have been conducted using the Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick (2000) assessment model, which is based on four levels of analysis: satisfaction, learning, transfer, and impact. As the authors of this model have indicated, the first two levels, i.e., satisfaction and learning, centering on the comparison of students’ and teachers’ views, are the most frequently studied. Amongst the instruments used to assess the course and teaching quality, the most numerous are opinion surveys of students’ perceptions of teaching staff and course organization (Jornet, 2017). Research shows that such questionnaires reliably reflect students’ classroom experience (Escudero, 2000; Casero, 2008) and are a necessary and useful tool for improving quality (Tejedor, 2003; Molero and Ruiz, 2005; Hannan and Silver, 2005).

In line with the multidimensional concept of quality on which this study is based, we concur with Núñez (2002), for whom “quality management is a set of actions aimed at ensuring academic excellence, rather than a simple form of accountability” (p. 9). Thus, in our view, it is indispensable for assessment to take into account more overarching criteria, such as economic efficacy (educational productivity); administrative and managerial efficiency (organization of resources); pedagogical efficacy (the relationship of teaching practice to educational outcomes); and social efficacy (educational and organizational actions that favor coexistence and social cohesion; Harvey and Green, 1993).

Another criterion of quality that should be taken into account is the level of student satisfaction with educational programs. Analyzing different assessment models for course satisfaction, Parra and Ruiz-Bueno (2020) identified three: those oriented toward outcomes; those oriented towards processes; and integrated models. The same authors also classified six levels of evaluation according to the factors analyzed, starting from an initial level focusing on the evaluation of pedagogical coherence (level 1), and subsequently going into greater depth and complexity at higher levels, centering in turn on satisfaction (level 2); learning (level 3); transfer (level 4); impact (level 5); and outcomes or profitability (level 6). The present study focuses on level 5 and aims to assess the professional development value of the master’s degree (Ruiz-Bueno, 2011; Cano, 2016; Parra and Ruiz-Bueno, 2020; Castro et al., 2020).

In light of the above, the study set out to evaluate the practical value of the training course with the purpose of determining what factors the program addressed and what personal and professional needs it fulfilled. Also, when assessing satisfaction, the achievement of objectives and outcomes was examined (Pineda, 2002). In short, the objective was to provide ongoing scrutiny of the program and to undertake an exercise in transparency and accountability on behalf of the agencies which had designed the course (Ruiz-Bueno, 2011).

Methodology and sampling

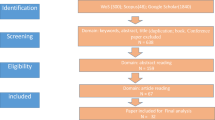

Method

An online self-administered survey was conducted (Díaz de Rada, 2012; Mayorga et al., 2016) among 308 teachers-in-training taking the Master’s Degree at the MFPESE-UB from 2017 to 2019, with aim of appraising the educational quality of this course. Quality was assessed using the measures discussed above: (1) internal (academic and administrative organization and structure); (2) external (teaching practices and material and human resources); and (3) trainee satisfaction with the practical value of the program for professional development.

Instrument

The data-gathering instrument used was the Teacher-Training Master’s Degree Final Survey, 2017–2019. This was developed for online use after completion of training, with the objective of ascertaining trainees’ perceptions of the quality of the program and their satisfaction with its impact on their teaching practice. To elaborate on the final version of the survey, its content (comprehensiveness, dimensions analyzed, appropriacy of measures) and question formulation (relevance and coherence) were validated by judges with an established track record of university teaching and experience in adapting degrees to the European Higher Education Area (EHEA).

The questionnaire comprised four dimensions, each relating to an aspect of the theoretical framework presented in the previous section, and summarized below in Table 1. The survey scales showed high-reliability values, with internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s alpha demonstrating that no item produced variations in the survey’s overall content. The high general reliability of the survey was confirmed by the same means, with a more than the satisfactory value of 0.916 and a confidence level of 95% (p = 0.05).

In this article, we present the results obtained from the three first dimensions of the questionnaire, namely: the demographic data characterizing student profiles; quality in the academic and administrative organization of the degree; and quality in teaching and human and material resources. For the fourth dimension, “contributions of the master’s degree to the philosophy of Good Living,” we chose to focus on results relating to trainees’ satisfaction with the benefits of the course for their professional development (questions 20, 23, and 24 in the survey) and teaching practice.

Participants

The sample was mostly made up of women (70.5%), with 95.1% having degree-equivalent training before beginning the program. Participants were all adults (43% aged 45–54) and mostly worked in secondary schools (65.23%), with a lesser number in primary education (32.62%). A majority had extensive teaching experience (52% with 10–25 years of professional experience). Participation in terms of the specialization studied was: 32.5% Language and Literature; 25.3% Educational Guidance; 22.7% Mathematics; and 19.5% History and Social Sciences. The sample was selected through non-random routes and access to all trainees who had passed the UNAE master’s degree in 2018 (455). 308 participants responded to the survey voluntarily and anonymously in April and May 2020.

Data analysis

A descriptive analysis of all the study variables was performed, focusing on the measures of the central tendency and deviation for the quantitative variables, and on the frequency with which categories appeared for the qualitative variables. The quantitative data were analyzed using the SPSS V. 27 statistical analysis program. The qualitative data yielded by the open questions were processed by qualitative text analysis using Nvivo12 software, in order to speed up activities such as text segmentation in citations, coding, and comment writing (Gibbs, 2012).

The initial categories were developed from the survey transcripts through an inductive and deductive process based on the criteria for internal and external quality and satisfaction with the degree and its value for trainees’ professional practice.

In the following section, certain participants’ words are cited literally, in which case each quotation is labeled with its corresponding code. Responses were coded as follows. Each respondent was assigned a number and the initial of their specialization (L = Language and Literature; M = Mathematics; S = History and Social Sciences; O = Educational Guidance and Counseling). Subsequently, the response was assigned a code identifying which questionnaire dimension (see Table 1) it related to the academic and administrative organization of the degree was represented by the initials OA; the quality of teaching and organization of material and human resources by CD; and satisfaction with the degree and its value for professional development by SM. After these initials, the number of the question answered was added.

Results

Organizational quality

The organizational quality and academic and administrative structure of the master’s degree were highly rated, obtaining an average of 9.72 out of 10 in the scalar question on organizational quality (on a scale of 1: very bad, to 10: excellent), with a standard deviation of 0.597 (see the appendix for descriptions of all the survey dimensions). 77.9% of respondents considered the organization excellent, awarding it 10 out of 10, followed by 17.86% who rated it at 9 (Fig. 1).

The reasons for this outstanding assessment of administration and management by 96% of trainees revolved around three key areas: management and organization, which were seen as prompt and efficient in resolving incidents (registration, access to information, management of administrative procedures, apostilles, etc.); the quality of human resources on the academic, professional and human levels; and effective communication between the UNAE and the UB in both academic and administrative matters.

Organization and management were rated according to two factors: firstly, the administration and coordination of the degree, and secondly, the efficiency of the teaching team. In the first case, the coordination between the participating universities was appreciated for its efficiency in the prompt solution of any issues arising:

Those in charge of the administration and management always paid attention to our questions and constantly made suggestions to make the master’s degree more agile and efficient. (056L_OA9)

In the second case, trainees also perceived organizational quality among the teachers of each subject. More specifically, coordination between teachers aimed at complying with the planned tutorials, tasks, and deadlines, taking into account trainees’ needs and concerns, was highly valued. These data were confirmed by the quantitative data on human resources and the managerial effectiveness of the degree (Table 2).

Almost 100% of participants were of the opinion that the human resources deployed were adequate and appropriate (on a scale from 1: completely disagree, to 5: completely agree). They also gave high scores to the teaching materials and resources, such as the university facilities and the online platform.

During both the virtual and face-to-face studies all the necessary resources were available for smooth organizational and academic execution. (233E_OA9)

The efficiency of the coordinating team in responding quickly and effectively to trainees was likewise corroborated (91.9% affirmed this); and this was also the case for coordination and communication between the UB and the UNAE:

The organization and management of the degree by the University of Barcelona and the UNAE were very efficient, as all the processes, both academic and administrative, were fully carried out. (210L_OA9)

As evidence of this last factor, Table 3 illustrates trainees’ strongly positive assessment of the coordination between the face-to-face and online phases of the degree and the distribution of responsibilities among the institutions involved: in both cases, 99.7% agreed, with the majority of the answers in the highest band, on a scale of 1: completely disagree, to 5: completely agree.

Among the points suggested for improvement in this dimension of quality, it was noted that changes in venues for face-to-face classes were not always announced sufficiently in advance. Adaptation of schedules of in-person classes to student needs was another aspect for improvement, as students who lived outside the cities where the sessions were held had problems arriving to class.

Quality of teaching

The quality of teaching was also highly rated, with an average of 9.83/10 and a standard deviation of 0.429, as can be seen in the appendix on the statistical descriptions of all the survey dimensions. 85.4% of respondents perceived teaching quality as excellent, awarding it 10 on a scale of 10 (1: very bad, to 10, excellent), with 13% rating it at 9 (Fig. 2).

Qualitative analysis of the open question enquiring into the reasons for respondents’ evaluations of teaching quality enabled the identification of the most frequent terms used, as shown in the tag cloud below (Fig. 3). The quality of teaching was directly associated with the resources, materials and content of the course and was complemented by the methodology adopted and knowledge conveyed by the trainers.

From: Data obtained from question no. 10b of the survey (open type). Tag cloud. Compiled by the authors based on the information provided by the software Nvivo. The translation of the words from Spanish to English in descending order from highest to lowest is: resources prepared/materials/classes/teacher/content/quality/knowledge.

Teaching quality was intrinsic to the assessment of the trainers, and was perceived as excellent, both in terms of their mastery of the course content and their human quality.

Having excellent trainers was one of the characteristics of the course: the materials, resources and methodologies applied were very good and the instructors’ interventions were timely and reliable. (045M_CD13)

The materials and resources used were also highly valued: “Most of them were very well designed, the classes were understandable, and there were never any academic gaps” (212S_CD13). The synergy of these two factors with a student-centered methodology, with active student participation and interaction in both the physical classroom and online, was another important indicator of the teaching quality of the degree.

The different methodologies used fostered a good working environment and were appropriate. For instance, the use of ICTs and projections of visual images, which allowed greater participation in the teaching-learning process. (019L_CD13)

Classroom activities using ICTs and project-based learning were appreciated over and above lectures and presentations. Sessions promoting group work were also particularly valued, as they fulfilled the maxim cited by several trainees: “Tell me and I forget, teach me and I remember, involve me and I learn.” In addition to this favorable assessment, the survey also allowed students to suggest improvements in the following aspects of the course:

A) With regard to materials and resources, two important features relating to time and the face-to-face mode were identified for improvement, as illustrated in the tag cloud below (Fig. 4):

From: Data obtained from question no. 11 of the survey (open type). Tag cloud. Compiled by the authors based on the information provided by the software Nvivo. The translation of the words from Spanish to English in descending order from highest to lowest classes/material/time/face-to-face/teachers.

Face-to-face classes were rated very positively for their contribution to more experiential and significant learning; respondents urged an increase in these sessions, using less extensive materials in some cases, and more oriented toward practical learning contexts than theoretical knowledge. For some cases and specializations, trainees saw it as more appropriate “to change the way of teaching by applying hands-on materials to make classes more playful, and to deliver programs explaining the content” (300M_CD14). Greater use and diversity of technological resources in face-to-face classes was a further recurring suggestion for improvement.

Materials such as technological resources like videoconferences or teleworking allow for more interaction between the teacher and the students in clarifying any questions that may arise during the classes. (094E_CD14)

Trainees saw access to materials and resources as another factor for improvement, as this could promote more autonomous learning. Two key suggestions for enhanced transfer of knowledge to the trainees’ own students were to provide a summary of the topics covered, in the form of a coursebook, and to make access available in Ecuador to resources such as the bibliography and documentary sources used: “I see the use of virtual classrooms to explain the tasks posted on the platform as really valuable” (276E_CD14); “We should be invited to the congresses, seminars, and talks on the subjects we saw, and get recommendations for YouTube channels where we can follow the trainers’ video lessons” (024S_CD14).

B) With regard to the contents, although they were rated as excellent, at times they were seen as unsuited to the reality on the ground in Ecuador. This geographical mismatch, which decreased transfer to the professional teaching context, was a recurrent criticism in several of the answers analyzed:

The approach should be closer to the situation in Ecuador, since many of them did not fit the Ecuadorian context. (145E_CD15)

This suggestion was also linked to the requirement for greater transfer of the contents to the trainee teachers’ actual practice. Respondents suggested improving the connection of learning to practice; thus, it was recommended that the course be more oriented towards classroom activities, focusing on conveying know-how and how to put it into practice, which would also allow the trainers in each specialization to go into greater depth. This suggestion was extended to the course methodology, with trainees proposing more appropriate, dynamic, and participatory approaches via interactive techniques that would allow trainers to share more of their experience and for longer periods: “Having more time for trainers to participate in class, making classes more dynamic, because in the face-to-face classes, the schedule is too long and tiring and the teachers lose interest in the classes” (111M_CD16).

Satisfaction with the professional value of the course

In order to analyze the professional development value of the course, it was necessary to adapt the study to the social and educational situation in Ecuador, adopting a two-fold focus. The first area inquired into was the trainees’ teaching practices, in terms of transfers of learning that enhanced their professional development; and the second centered on the principles of Good Living and the contributions of the master’s degree to improving teaching practices in schools governed by these precepts.

The percentages presented in the table below (Table 4) confirmed that these objectives were effectively met. The professional value of the degree was strongly corroborated, firstly in terms of improvements in teachers’ own practices and in their schools (91.5% were strongly or totally in agreement on this point, on a scale from 1: completely disagree, to 5: completely agree), and to a lesser extent, although no less significantly, in terms of the extension of learning to colleagues (88.7% affirmed this). The quality of and opportunities afforded by the training received were clearly perceived as excellent. 92% of respondents also perceived a strong relationship between the master’s degree curriculum and the principles of Good Living.

Trainees’ comments enabled us to understand in greater depth the reasons for their satisfaction by analyzing two complementary narratives: the reasons given for their evaluations, and the improvements they noted in their teaching practice after taking the degree.

Regarding the first, the high professional development value of the course was especially associated with quality, the term that emerged at the core of the word cloud (below, Fig. 5) yielded by the qualitative analysis of the data emerging from question 21 of the survey:

From: Data obtained from question no. 16b from the survey (open type). Tag cloud. Compilated by the authors based on the information provided by the software Nvivo. The translation of the words from Spanish to English in descending order from highest to lowest is quality/training/students/knowledge/goal/master/education.

In this case, quality as a criterion of value was linked to four key factors, as the following citations from trainees testify.

-

A.

The training received was appropriate for trainees’ professional development because “it provided us, Ecuadorian teachers, with reliable, suitable and high-quality training and improved our practices, in my view” (085L_SM21).

-

B.

The personal and professional experience of the course was “an experience of quality and human warmth, which allowed us to grow both personally and professionally, and thus teach and share our knowledge generously” (137M_SM21).

-

C.

The teacher educators exhibited human qualities and effectively conveyed knowledge: “I had very professional teachers with human quality and warmth” (085L_SM21).

-

D.

Trainees’ expectations of enhanced educational quality as a direct effect of the course, among their students, and in their specific teaching contexts, were fulfilled. This is the essential defining factor of professional value: “the objective of quality in Ecuadorian education is being achieved comprehensively through the application of the new knowledge acquired, with the human aspects stressed in each action” (091L_SM21).

With regard to the benefits of the master’s degree for their professional practice, respondents stressed the educational innovations they had learned (in interpersonal relationships and communication, in teaching approaches and methods, in technological resources and materials, and in tools for assessment and tutorial management), which were helpful for meeting educational needs in their own contexts and particular educational situations:

Yes, my teaching practice has improved, because by applying the various techniques, resources and methods I’ve achieved quality results. Example: by using groupwork and motivational techniques I was able to stimulate interest among my students. (006O_SM24)

This aspect of professional development was perceived and articulated from the standpoint of personal and professional responsibility, and also afforded trainees the chance to reassess their identity as education professionals and strengthen its meaning and value for themselves:

The master’s degree training changed my way of thinking. I’ve put into practice what I’ve learned, I’ve left behind traditional methods to do my classes in a more playful way, interpreting the issues from different points of view, developing logical, critical and creative thinking in my students. (069S_SM24)

These beneficial outcomes were also clearly evident from the perspective of the philosophy of Good Living, which is the essential foundation of education in Ecuador, shaping the design of school curricula. As Table 4 above illustrates, 92.5% of participants perceived a strong relationship between the degree curriculum and the principles of Good Living. The value of the degree in this sense emerged particularly in trainees’ personal and professional growth in the context of their role as key actors in this mission and as educators committed to realizing it, responsible for constantly updating their knowledge and practice. Among the main benefits of the course, they noted:

A) The use of methods favoring closer contact with students, which thereby helped them to advance further in this approach to life, adopting more humanistic practices in which the students themselves constructed knowledge from the standpoint of social responsibility, working together in a harmonious and respectful atmosphere:

The sumak kawsay seen as an end in itself, as a potential paradigm with all its implications, as a dream that we must work towards, prioritizing collective needs over the individual and seeing it as an ideal future towards which to direct our efforts in the family and the community. (081L_SM22)

Respondents saw the students and their holistic growth as the main focus of education, and for this reason thought that the teacher should be trained to develop emotional, social, and ethical competencies.

B) Identification with the model of a society governed by the principles of buen vivir, as seen from the standpoint of strengthening national identity and citizens’ commitment to it. In these terms, the master’s degree promoted “greater commitment to a society whose principles are governed by justice, solidarity and transparency as principles of Good Living” (147M_SM22). In another trainee’s words:

Teacher training is extremely important for achieving Good Living. In the professional environment we work with groups of people, whether colleagues, students or parents, and our social relationships should always be framed by the values and principles of Good Living. (187O_SM22).

Discussion and conclusions

In light of these findings, it can be affirmed that the educational program of the master’s degree fulfilled the criteria for quality in higher education in the context of the Ecuadorian philosophy of Good Living. The study was based on a multidimensional concept of quality that allowed for the assessment using measures focusing on the degree’s organization (quality in the academic and administrative organization), teaching (trainers, content, resources, materials), and methodology (Castilla, 2011; Welzant et al., 2015), in addition to trainees’ satisfaction with its outcomes for their professional development.

These findings show that it is possible to organize and deliver a master’s degree program in which two universities on different continents work jointly to successfully accomplish educational objectives at a high standard of quality in all areas.

In the first instance, the results in the area of external quality (organization, management, facilities, and material resources) confirmed that these aspects contributed to the effective delivery of the master’s degree since 100% of trainees saw them as adequate and appropriate. Factors such as the constant coordination among the organizers, the teachers, and the trainees, in addition to good communication amongst all actors, were highlighted as key to achieving the high level perceived in this external dimension of quality. On the other hand, the need to rearrange the venues used for face-to-face classes was noted.

Secondly, amongst the most conclusive data were the high ratings given to the training team and to their teaching as outstanding elements of internal quality. Trainees specifically underscored the dynamic methodology and the resources and materials provided as values favoring educational quality in this internal dimension. Suggestions for improvement centered around the need to reorient the contextualization of the course content, adapting it more closely to the specific situation of Ecuadorian education.

Thirdly, regarding satisfaction with the professional development value of the degree, it was confirmed that the training received afforded significant benefits both in practice and in terms of transfer to professional performance (Pineda, 2002; Parra and Ruiz-Bueno, 2020) and that this was a factor that directly contributed to realizing the principles of Good Living.

In addition to these proofs of quality, the study also yielded the following recommendations for updating and improving the master’s degree:

First, structural reorganization was urged in order to boost coordination among the universities, students, and teachers, particularly in the face-to-face phase. The blended-mode course delivered from 2017 to 2019, jointly with this study’s findings on quality and satisfaction, showed that this mixed mode of learning (Dziuban et al., 2018; Adel and Dayan, 2021) was beneficial. Also, its advantages and disadvantages were identified, allowing for adaptation to the new context of the pandemic. Challenges that emerged to its optimum functioning included the need for adequate infrastructure and technological access; political support and the engagement of teaching staff; technological knowledge and skills; and the availability and mastery of various types of technological resources (Tshabalala et al., 2014).

Second, the choice of teachers for the modules of each specialization was another factor of interest, since, apart from their professional quality, the study also demonstrated their human quality. A selection process had been carried out in which motivation was a key factor; but since the social, cultural, and educational contexts of Ecuador were unknown to most of the teaching staff, a seminar on these issues for the foreign trainers would have been helpful, as this would have equipped them better to respond to trainees’ requests for revision of the curriculum content to address the socio-economic, educational and geographical diversity of their country.

Third, another recommendation was that an ongoing training network should be set up among the trainees to ensure the sustainability of professional outcomes in the long term. In this way, they themselves would become drivers of change and innovation in their schools. Also, they would be able to connect their training with the principles of Good Living and with a fresh, up-to-date vision of education, centered on the training of active, committed citizens.

For these reasons, and in accordance with the precepts of Good Living, the directives of the Latin-American Laboratory for Assessment of Quality in Education (Casassus et al., 1996), and the proofs of the quality of the master’s degree after its delivery, it can be affirmed that this was a valuable initiative on the part of the Ecuadorian government for upgrading its teachers’ training by means of a development plan. Nevertheless, for this to be consolidated, it should be sustained over time, accompanied by further support and follow-up for teachers (unfortunately, at the time of writing, the delivery has been suspended). Amongst similar improvements, it would also be advisable to survey the trainers on the master’s degree in order to collect evidence from a different group of participants (Tejedor, 2009; Molero and Ruiz, 2005; Hannan and Silver, 2005; Freixa et al., 2015).

Another important advance for Ecuadorian higher education institutions would be to undertake self-evaluation as an internal regulatory mechanism designed to ensure the effectiveness and quality of institutional management (Peña et al., 2018). In the light of the multidimensional concept of quality underpinning this study, such a process of self-assessment on the part of the institutions involved would be of great value for strengthening the culture of self-awareness in the system of institutional management, with a view to fulfilling established benchmarks of quality. In Latin America, due to recent considerable growth in the process of accreditation for higher education institutions, it is still a challenge to put systems and/or mechanisms in place that set out to integrate self-assessment in order to enhance quality progressively and permanently.

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this article and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

This study was funded by the master’s degree as an exercise in accountability and critical analysis of the work carried out.

References

Adel A, Dayan J (2021) Towards an intelligent blended system of learning activities model for New Zealand institutions: an investigative approach. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8:72. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00696-4

Arranz P (2007) Los sistemas de garantía de calidad en la Educación Superior en España. Propuesta de un modelo de acreditación para las titulaciones de Grado en Empresa. PhD thesis, University of Burgos, Spain.

Ball CJE (1985) What the hell is quality? In: Ball CJE (ed) Fitness for purpose. Essays (in Higher Education). SRHE/Nelson, Guildford, pp. 96–102

Bertolini J (2017) Integral education in higher education and the development of nations. Caderno Pesquisa 165:848–869. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053144005

Cano E (2016) Factores favorecedores y obstaculizadores de la transferencia de la formación del profesorado en educación superior Rev Iberoam Sobre Calid Efic Cambio Educ 14(2):133–150

Casassus J, Arancibia V, Froemel JE (1996) Laboratorio Latinoamericano de Evaluación de la calidad de la educación. Rev Iberoam Educ 10:231–261. https://doi.org/10.35362/rie1001174

Casero A (2008) Propuesta de un cuestionario de evaluación de la calidad docente universitaria consensuado entre alumnos y profesores. Rev Investig Educat 26(01):25–44. https://revistas.um.es/rie/article/view/94091

Castilla F (2011) Calidad docente en el ámbito universitario: un estudio comparativo de las universidades andaluzas. Educade. Rev Educ Contab Finanz Adm Empres 2:157–172

Castro M, Navarro E, Blanco MA (2020) La calidad de la docencia percibida por el alumnado y el profesorado universitarios: análisis de la dimensionalidad de un cuestionario de evaluación docente. Educación XXI 23(02):41–65. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.25711

Cuestas-Caza J, Góngora-Almeida S (2014) Adoption of Good Living in Ecuador as an alternative paradigm to the development. Paper presented at the 5th LAEMOS Colloquium. Latin American and European meeting on Organization Studies, La Habana, Cuba, 2–5 April 2014. Available at (PDF) Adoption of Good Living in Ecuador as an alternative paradigm to the development (researchgate.net)

De la Orden A, Jornet JM (2012) La utilidad de las evaluaciones de sistemas educativos: el valor de la consideración del contexto. Bordón 64(02):69–88.

Díaz de Rada V (2012) Ventajas e inconvenientes de la encuesta por Internet. Papers. Rev Sociol 97(01):7–31. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/papers/v97n1.71

Dziuban C, Graham C, Moskal PD, Norberg A, Sicilia N (2018) Blended learning: the new normal and emerging technologies. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 15(03):3–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0087-5

Escudero T (2000) La voz de los estudiantes: un delicado instrumento de evaluación. Cuad IRC 5:31–38

Esquivel JE (2007) Chile: an experimental field for university reform. Perfiles Educ 29(116):41–59. Available at Chile: campo experimental para la reforma universitaria (scielo.org.mx)

Feixas M, Lagos P, Fernández I, Sabaté S (2015) Modelos y tendencias en la investigación sobre efectividad, impacto y transferencia de la formación docente en educación superior. Educar 51(01):81–107. https://raco.cat/index.php/Educar/article/view/287036

Ferreira G, Bueno V (2019) University Pedagogy. For an institutional teaching development policy in higher education. Caderno Pesquisa 49(173):44–62. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053145897

Freixa M, Aparicio-Chueca P, Triadó X (2015) El rol del profesorado como elemento clave en las instituciones y en el contexto de la educación superior. In: Figuera P (coord) Persistir con éxito en la Universidad: de la investigación a la acción. Laertes, Barcelona, pp. 139–156

Gibbs G (2012) El análisis de datos cualitativos en investigación cualitativa. Morata, Madrid

Gobierno de Ecuador-Secretaría Nacional de Planificación y Desarrollo (2009) Plan Nacional Para el Buen Vivir 2009–2013. Construyendo un estado Plurinacional e Intercultural. Secretaría Nacional de Planificación y Desarrollo-Sendplades, Quito

Gobierno de Ecuador-MINEDUC (2016) Currículo de los niveles de Educación Obligatoria. MINEDUC-Don Bosco, Quito

González V, Ricardo J, Ramírez Montoya MS, Alfaro JA (2011) The culture of evaluation in educational institutions: Understanding of indicators, competencies and underlying values. Perfiles Educ 33(131):42–63. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0185-26982011000100004&lng=es&nrm=iso

Guzman A, Torres J (2004) Implications to total quality education. Educ Res Inst 5(1):88–99

Gvaramadze I (2008) From quality assurance to quality enhancement in the European Higher Education Area. Eur J Educ 43(04):443–455. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25481874

Hannan A, Silver H (2005) La innovación en la Enseñanza Superior. Enseñanza, aprendizaje y culturas institucionales. Educ Siglo XXI 23:215–217. https://revistas.um.es/educatio/article/view/129

Harvey K, Burrows A (1992) Empowering students New Acad 1(3):1ff

Harvey L, Green D (1993) Defining quality Assess Eval High Educ 18(01):9–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293930180102

Jornet JM (2017) Evaluación estandarizada. Rev Iberoam Eval Educ 10(01):5–8. https://revistas.uam.es/riee/article/view/7590

Jornet JM, González-Such J, Perales MJ, Sánchez-Delgado MP (2017) La evaluación educativa como ámbito de especialización profesional. Crónica. Rev Cient Prof Pedag Psicopedag 02:7–24. http://hdl.handle.net/10550/65498

Kirkpatrick D, Kirkpatrick J (2000) Evaluación de acciones formativas: los cuatro niveles. Epise, Barcelona

Mayorga MJ, Gallardo M, Madrid MD (2016) Cómo construir un cuestionario para evaluar la docencia universitaria. Estudio empírico. Universitas Tarroconensis. Rev Ciènc Educ 02:6–22. https://doi.org/10.17345/ute.2016.2.974

Molero D, Ruiz J (2005) La evaluación de la docencia universitaria. Dimensiones y variables más relevantes. Rev Investig Educ 23(01):57–84. https://revistas.um.es/rie/article/view/98341

Mullins N (1973). Theory and theory groups in contemporary American sociology. Harper and Row, New York.

Núñez J (2002) Evaluación académica, postgrado y sociedad. In: Cruz V y Millán S (coords.) Asociación Universitaria Iberoamericana de Posgrado (AUIP). Gestión de la Calidad del posgrado en Iberoamérica. Experiencias Nacionales. Seminarios y reunion estécnicas internacionales. Programa de Calidad de la Formación Avanzada, Dirección general de la AUP, Salamanca, pp. 36–57. Available at https://www.auip.org/images/stories/DATOS/PublicacionesOnLine/archivos/gestion_calid_post.pdf

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura (UNESCO) (2016) Innovación Educativa. Serie: Herramientas de apoyo para el trabajo docente. Texto 1. Cartolan E.I.R.L., Perú

Parra R, Ruiz-Bueno C (2020) Evaluación del impacto de los programas formativos: aspectos fundamentales, modelos y perspectivas actuales. Rev Educ 44(02):2215–2644. https://doi.org/10.15517/REVEDU.V44I2.40281

Peña LR, Almuiñas JL, Galarza J (2018) La autoevaluación institucional con fines de mejora continua en las instituciones de Educación Superior. Univ Soc 10(4):18–24. http://rus.ucf.edu.cu/index.php/rus

Pineda P (2002) Gestión de la formación en las organizaciones. Ariel, Barcelona

Rodríguez J, Hernández-Vázquez JM (2020) The student perspective on university reforms in four Mexican public institutions. Perfiles Educ 42(170):77–95. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.24486167e.2020.170.59174

Ruiz-Bueno C (2011) La evaluación de programas de formación de formadores en el contexto de la formación en y para la empresa. PhD thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, España

Sahney S, Banwet K, Karunes S (2010) Quality framework in education through application of interpretive structural modeling: an administrative staff perspective in the Indian context. TQM J 22(1):56–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542731011009621

Sakthivel PB, Rajendran G, Raju R (2005) TQM implementation and students’ satisfaction of academic performance. TQM Mag 17(6):573–589. https://doi.org/10.1108/09544780510627660

Schindler L, Puls-Elvidge S, Welzant H, Crawford L (2015) Definitions of quality in higher education: a synthesis of the literature. High Learn Res Commun 5(03):3–13. https://doi.org/10.18870/hlrc.v5i3.244

Tedesco JC(2009) Calidad de la educación y políticas educativas Caderno Pesquisa 39(138):795–811. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-15742009000300006

Tejedor FJ (2003) Un modelo de evaluación del profesorado universitario. Rev Investig Educ 21(01):157–182. https://revistas.um.es/rie/article/view/99151

Tejedor FJ (2009) Evaluación del profesorado universitario: enfoque metodológico y algunas aportaciones de la investigación. Estud Sobre Educ 16:74–02. https://doi.org/10.15581/004.16.%25p

Temponi C (2005) Continuous improvement framework: implications for academia. Qual Assur Educ 13(1):17–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684880510578632

Tshabalala M, Ndeya-Ndereya C, van der Merwe T (2014) Implementing blended learning at a developing university: obstacles in the way. Electron J e-Learn 12(01):101–110. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/153387/

Valenzuela JR, Ramírez MS, Alfaro JA (2011) Cultura de evaluación en instituciones educativas: Comprensión de indicadores, competencias y valores subyacentes. Perfiles Educ 33(131):42–63

Vizcarro C (2003) Evaluación de la calidad de la docencia para su mejora. Rev Red Estatal Docencia Univ 3(01):5–18. https://revistas.um.es/redu/article/view/10571

Welzant H, Schindler L, Puls-Elvidge S, Crawford L (2015) Definitions of quality in higher education: a synthesis of the literature. High Learn Res Commun 5(3) https://doi.org/10.18870/hlrc.v5i3.244

Wiggins G (1990) The truth may make you free but the test may keep you imprisoned: towards assessment worthy of the liberal arts. In: AAHE Assessment Forum (ed) 1990: understanding the implications. Assessment Forum Resource. American Association for Higher Education, Washington, DC, pp. 15–32

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants of the Master’s Degree in Education in Ecuador from the National University of Education of Ecuador, the Ecuadorian Education Ministry, and the University of Barcelona.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. The design of the questionnaire, dissemination, and data collection was conducted by the first author. The second author analyzed the statistical and qualitative data. All authors participated in data interpretation, drafting the study, and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be held accountable for all aspects of the study when ensuring that issues relating to the accuracy and integrity of any part of it are appropriately resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statements

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the university. Ethical clearance and approval were granted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights.

Informed consent

The survey was anonymous and was administered with the authorization of all participants and the commitment of the authors to the privacy and confidentiality of the information gathered.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ambrós-Pallarés, A., Puig, M.S. & Moreno, C.F. Quality of a master’s degree in education in Ecuador. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 26 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01503-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01503-6