Abstract

The Framework Programmes for Research and Technological Development are funding programmes created by the European Union to support and foster research. This study aims to describe the features and assess the performance of Social Sciences and Humanities research projects funded under the Sixth Framework Programme that was active between 2002 and 2006. The results show that most funded projects were in the fields of economics and political sciences, in line with the use of the Framework Programme to enhance economic development and the integration process in Europe. Research teams showed a high level of collaboration with an average of 7.8 countries and 10.8 institutions involved in each project. However, the large size and diversity of consortia did not translate into a large number of co-authored scholarly journal articles. The results show that research funds in the Social Sciences and Humanities may have long-term effects, with some outputs acknowledging funding being published more than a decade after the end of the project. Qualitative analysis of the acknowledgements in the articles revealed four types of support: direct funding; utilisation of results from former funded projects as the basis for further research; involvement in conferences and networks resulting from funded projects; and utilisation of datasets or other products resulting from former funded projects. The study also illustrates the difficulties in retrieving the outputs resulting from funded projects since the funding information in Scopus is heterogeneous and not standardised. As a result, the type of assessment conducted in this project is time-consuming and requires a significant amount of manpower to clean and standardise the data. Nevertheless, the procedure could be applied to analyse the performance of subsequent European Framework Programmes in building a European Research Area in the Social Sciences and Humanities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Framework Programmes (FP) for Research and Technological Development are funding programmes created by the European Union to support and foster research in the European Research Area. Through thematic calls for projects, they constitute the main funding instrument to support research in the European Union since 1984. This article explores how the European Union contributed to the development of research in the fields of Social Sciences and Humanities through the Sixth Framework Programme (FP6), which assembled a collection of actions to fund and promote research between 2002 and 2006.

The reason for focusing on FP6 lies in the increase of prominence of the Social Sciences and Humanities in this programme. Although Social Sciences and Humanities had been present in Framework Programmes FP4 (1994–1998) and FP5 (1998–2002), their status took a step forward in FP6, when one of the seven thematic priorities set was “Citizens and governance in a knowledge-based society” with an allocation of 247 million euros, 1.3% of the 19,235 million euros invested in FP6 (Rietschel et al., 2009, p. 9). Previous research (Kastrinos, 2010; Schögler and König, 2017; Kropp, 2021) have investigated the progressive establishment of Social Sciences and Humanities research in the European Union, mostly through the analysis of the policy documents that set up the research priorities behind FP calls. In this paper, we employ a different approach by studying the features of the research projects in Social Sciences and Humanities funded under FP6 between 2002 and 2006, analysing the types of support provided by research funds and describing the characteristics of the scholarly journal articles published as a result of these projects.

Social Sciences and Humanities in the landscape of European research

Social Sciences and Humanities research has been progressively included in European FPs. Recently reviewing the history of European Social Science research, Kropp (2021) observed that, since the 1980s, social scientists become increasingly involved in scientific research at the European level. They formed academic associations (Boncourt, 2017), launched scholarly journals (Heilbron et al., 2017) and set up European social surveys leading towards the use of standardised data sources and a homogenisation of methods and criteria for data collection and analysis across Europe. Simultaneously, Social Science knowledge has been essential in the construction of the European Union, by contributing to build up the Union legal framework or by organising the single market and the Euro, to name but two examples.

The position of the Social Sciences in the European Union research policies took a step forward in the 1990s. At that time, the European Union extended the scope of its FPs by labelling as important research questions Social Sciences issues such as social cohesion, solidarity, democracy, social welfare or living standards. With the FP4 (1994–1998), Social Science issues were included for the first time on their own terms in FPs and not only as support for technological or natural science issues (Schögler and König, 2017).

Despite this apparent consolidation of Social Sciences research, in 2010 Katrinos argued that, although FPs seemed to emphasise research priorities and thematic orientations—including societal changes—European research funding was moving towards a “diffusion-oriented model”, prioritising capacity building over fulfilling a distinct mission. He also observed that the various FP sub-programmes emerged as points-of-reference for the member states, both in terms of themes and orientation. Similar observations were made by Schögler and König (2017) when investigating the evolution on how the European Union has formulated their funding policies towards the Social Sciences. When analysing the programmes devoted to these disciplines, they discerned three features: the dominance of the economic dimension and the integration process, reflecting the aim of the European Commission to use the FPs to enhance economic development in Europe; the focus on the relationship of science and technology with society, education and social exclusion, showing an emphasis on interdisciplinarity; and the fact that the adding of Humanities to Social Sciences did not change this perspective dramatically. Thus, Humanities were officially included in the FP for the first time in FP6, giving birth to the acronym SSH (Social Sciences and Humanities), possibly as an aggregative term equivalent to STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics).

This apparent attempt to equate SSH to STEM did not have a direct impact on budgetary allocations. Kropp (2021) recently described the position of the Social Sciences within the European Union research policy as “fragile”, occupying a “marginal” place. The shaping of the Horizon 2020 programme would have consolidated this subordinate role of the Social Sciences as an accessory to questions and problems emerging from the natural sciences and their related industries. Official statistics on granted research between 2007 and 2020 (European Research Council, 2022) show the following distribution of projects by fields of knowledge: Life Sciences (33%); Physical Sciences & Engineering (45%); and Social Sciences and Humanities (22%).

In sum, we may conclude that, since the 1990s, Social Sciences have become a component of the FPs, although with a progressive transformation from a focus on “socio-economic” sciences to a more global approach to “Social Sciences and Humanities (SSH)”, an expression that aims to cover a set of heterogeneous research fields.

Knowledge generation and publication patterns in the Social Sciences and Humanities

Monitoring research performance in the Social Sciences and Humanities has been problematic for a long time. Performance indicators are usually impregnated by the features of the Natural and Life sciences and are less sensitive to the singularities of the Social Sciences and Humanities. These latter disciplines are characterised by a pronounced national and regional orientation; fewer publications in journals and more in books; a slower pace of theoretical development; a single-scholar approach rather than team research; and a greater share of publications directed at the non-scholarly public (Nederhof, 2006; Van Leeuwen, 2013).

Numerous studies confirm the existence of these specific features in knowledge generation and dissemination practices, although they note differences between academic fields and a certain homogenisation with the Natural and Life Sciences in the choice of journal articles in English as an increasingly relevant publication venue. These changes result from the requirements imposed by evaluation systems. Evaluative metrics have implications for knowledge production, including strategic behaviour and goal displacement, task reduction, and potential biases toward interdisciplinary research (de Rijcke et al., 2016), and researchers adapt their publication practices to the requirements of assessment agencies. Thus, although scholars in countries such as Australia and Sweden are critical of bibliometric indicators, they feel under pressure to use them (Hammarfelt and Haddow, 2018). An analysis of the publication patterns in the Social Sciences and Humanities between 2000 and 2009 in Flanders (Belgium) showed “considerable differences across disciplines in the SSH” and a “steady increase in the number and the proportion of publications in English […], going hand in hand with a decline in publishing in Dutch and other languages”, although no shift away from book publishing was observed (Engels et al., 2012). Focusing on two German political science institutions, Chi (2014) found that their main publication channels between 2003 and 2007 were books and book chapters rather than journal articles, with just a small share of the publications being indexed in the Web of Science. A later study (Chi, 2015) identified two main communication networks: a local one covering monographs and regionally oriented journals mainly written in German, and a smaller one, albeit increasingly international, comprising publications in English. More recently, a longitudinal analysis studying changes in the publication patterns of scholars working at a Social Sciences and Humanities university department in Flanders (Guns et al., 2019) indicated “a trend […] in both the social sciences and humanities toward peer review, use of English, and publishing in WoS-indexed journals”. In sum, evaluation practices increase pressure on scholars to publish journal articles in English. Despite these pressures, publication in many languages and diversity of document types, particularly books, remain important features of the panorama of the Social Sciences and Humanities.

Kulczycki et al. (2018) focused on language patterns in the Social Sciences and Humanities in non-English speaking European countries. They observed differences not only between fields, but within fields (i.e., the same field in different countries has different publication patterns). Nevertheless “in all countries, the share of articles and the share of publications in English is on the rise”. They also showed that social scientists and humanists continue to publish culturally and societally relevant work in their local languages (Kulczycki et al., 2020).

Regarding the importance of books as a publication venue, Engels et al. (2018) showed that the share of monographs in the Social Sciences and Humanities was stable between 2004 and 2015 in five European countries, with the exception of Poland, where reforms in the evaluation system allowed promotion based on a series of articles rather than only on monographs. The policies of research assessment agencies modify scholars’ behaviour, since “the parameters used in a performance-based funding system may influence the publishing patterns of researchers” (Ossenblok, Engels and Sivertsen, 2012). Despite limitations in the definition of monographs and book chapters, Engels et al. (2018) concluded that book publishing was not about to disappear in the Social Sciences and Humanities.

With regard to research collaboration, Ossenblok et al. (2014) observed “a sharp decline in single-author publishing” in the Social Sciences and Humanities though they also noted considerable differences between disciplines. Henriksen (2016) investigated how the methodological differences in research fields in the Social Sciences, together with changes in academia, affect the tendency to co-author articles. Her results showed a rise in the average number of authors and in the share of international co-authored articles in the majority of the Social Sciences. However, the results also showed great differences between disciplines. The most substantial rises in co-authorship occurred in subject categories where research is often based on experiments, large datasets, statistical methods and team-production models.

In sum, the results of research concur on the importance of national journals, frequently not covered by large citation databases, as publication venues for social scientists and humanists. Nonetheless, the traditional trend towards the publication of monographs, including books addressed to a non-scholarly audience, remains alive and healthy. This behaviour is more evident in the Humanities, whereas certain Social Sciences show a greater degree of homogenisation with the Natural and Life sciences. As Hicks (2004) points out, bibliometrics “work reasonably well in economics and psychology, whose literatures share many characteristics with sciences” but not in other fields where scholars publish books for national journals and for the non-scholarly press.

This publishing behaviour is highlighted in an exploratory analysis of the publications submitted to OpenAIRE by research teams in the Social Sciences and Humanities funded under FP7. OpenAIRE (www.openaire.eu) is an infrastructure created in 2009 with the aim of shifting scholarly communication towards openness and transparency. From FP7 onwards, OpenAIRE provides a filter to search for outcomes resulting from a given FP, but this option is not available for FP6. A total of 3099 publication records resulting from 253 projects funded in the Social Sciences and Humanities under FP7 were submitted by the research teams. Most publications (2,582 items, 83.3%) were journal articles, followed by book chapters (9.1%) and books (2.4%). Focusing on these 2,582 articles, 86.8% were published in journals indexed in Scopus. These results confirm the rising role of journals as a publication venue for Social Sciences and Humanities, at least for research funded under FP7.

Assessment of Social Sciences and Humanities research in the European Union

Several studies have aimed to evaluate the results of European FPs and, more specifically, FP6, which constitutes the focus of this article. The ex post evaluation of FP6 was carried out by a group of international experts (Rietschel et al., 2009). The success rate for the projects bidding for funds in the thematic priority focused on the Social Sciences and Humanities (“Citizens and governance in a knowledge-based society”) was similar to that of the whole FP, set at 18% (Rietschel et al., 2009, p. 15). Based on the analysis of the records in CORDIS database, Schögler and König (2017, p. 121) identified 144 social sciences and humanities projects funded under FP6, showing a decrease from 168 projects in FP4 and 237 in FP5, albeit the figure would increase to 253 projects in FP7. Rietschel et al. (2009) offered a positive view of the achievements of FP6, although they noted that there was room for improvement in terms of implementation and management. Regarding the achievements in the Social Sciences and Humanities, the report regretted the lack of empirical evidence on their impact:

“The social sciences and humanities research in this area provides information and support for policy development across a wide range of topics such as participation, tax reform, crime statistics harmonisation, counterterrorism, immigration and economic growth. There is a large number of instances of projects affecting policy, but at this stage there is no systematic evidence about the overall impact of the priority” (p. 44).

A subsequent report (Watson et al., 2010) evaluated the impact of the FP on the formation of a European Research Area in the Social Sciences and Humanities. A mapping exercise of projects receiving support under the 3rd call of FP5 and the whole of FP6 was conducted, although most data were collected through interviews and surveys of desk officers, project coordinators and researchers. The authors concluded that FP programmes had “had a limited impact on national programmes, and that national SSH [Social Sciences and the Humanities] research policy is still mainly driven by domestic agendas”, although “the programme has encouraged more interaction between researchers and policy-makers”.

Other studies have aimed to assess the performance of FP6, but they have mostly focused on science and technology. Thus, Vallés-Brau (2005) analysed the implementation of the first two calls for participation in the FP6 thematic priority devoted to “Nanotechnologies and Nanosciences, knowledge-based multifunctional materials and new production processes and devices”. In a similar fashion, González and Albahari (2007) identified more than 700 FP6 projects related to transport management to gather information on the kinds of projects funded, participation of countries, international cooperation and size of grants. Breschi and Malerba (2011) provided a quantitative assessment of the articles and patents resulting from FP6 projects in information and communication technologies by exploiting the Web of Science. Their results supported the idea that funding instruments might have resulted in artificially “too large” research consortia (p. 256). More recently, Galsworthy et al. (2014) identified FP5 and FP6 health research projects (1998–2006) to describe participation by country and subject area.

To the best of our knowledge, no similar analysis of the performance of projects funded in the Social Sciences and Humanities has been conducted to date. In addition to the relatively low significance of these disciplines in budgetary terms (1.3% of the funds invested in FP6), the difficulties in applying bibliometric methods to the Social Sciences and Humanities may help to explain this lack of attention. Thus, when analysing the results of the European Research Council’s funding calls between 2007 and 2012, König (2016) concluded that “10 years after the ERC’s inception, the question if the ERC has already shaped the way research in the social sciences and humanities is carried out remains unanswered”.

An important handicap in the evaluation of the results of research programmes, although non-exclusive of the Social Sciences and Humanities, is the lack of reliable and meaningful measures to assess their societal impact. Societal impact is much harder to measure than scientific impact. It may take many years until a piece of knowledge yields new products or services that improve society and, possibly, there are no indicators that can be used across all disciplines and fields of knowledge (Bornmann, 2012). This difficulty leads towards a lack of consistency in the use of terms to describe the results of research. Belcher and Halliwell (2021) recently complained that the terms “output, outcome, and impact […] are used ambiguously and the most common definitions for these terms are fundamentally flawed”. Based on their experience with conceptualising and assessing research impact in the Social Sciences and Humanities, they propose to differentiate among three main kinds of results from research: outputs, outcomes and benefits. Outputs would be the products and services of research, produced directly by a research programme. Outcomes would refer to changes in the agency of other actors when they use and/or are influenced by research outputs. Finally, benefits would be tangible changes in the social, economic, environmental, or other physical condition. In this study, we will focus on research outputs in the form of journal articles. Research projects funded under FPs are internationally oriented and journal articles are expected to be the most demanded output. Thus, the guidelines for FP6 project reporting (Project reporting in FP6, 2004, p. 70) required researchers to indicate the number of journal articles published and patents applied for, but no similar requirement was established for other scholarly outputs such as books. The evaluation of outcomes and benefits would be extremely interesting to assess the programmes’ performance, but it is beyond the purpose of this paper.

Purpose and research questions

This study aims to increase our knowledge about the characteristics and results of the projects funded in the Social Sciences and Humanities under the Sixth Framework Programme. As stated above, previous studies have investigated the evolution in how the European Union has formulated its research funding policies towards the Social Sciences and Humanities. Most of these studies have analysed the presence of these disciplines in European policy documents, showing their gradual inclusion in FPs. However, more research is needed in order to examine the characteristics of the Social Sciences and Humanities research projects funded under FPs, the type of support provided by FP funds, and the features of scholarly outputs resulting from these projects. We focus on these three issues by using a descriptive approach that aims to supplement the information currently available on FP6.

From a chronological point of view, we focus in FP6 given its importance in the consolidation of the Social Sciences and Humanities in European research. Therefore, our study focuses on research projects funded between 2002 and 2006. Nevertheless, it is necessary to point out that the data collection and analysis was conducted in 2020 and 2021, 14 years after the end of the programme. This long-term approach was necessary to capture a larger share of relevant outputs and to understand the dynamics of knowledge creation induced by research funding. The slower pace of knowledge creation in the Social Sciences and Humanities compared to other disciplines calls for this approach in order to detect aspects that may take a long time to manifest themselves. Additionally, the study aims to trial the assessment procedure that, if successful, could be employed to analyse subsequent European FPs. The research is underpinned by the following research questions:

-

a.

How many research projects in the Social Sciences and Humanities were funded under the European Union Sixth Framework Programme?

-

b.

What are the features of these projects in terms of length, grants awarded, disciplines, topics, countries and institutions involved?

-

c.

What kind of support do the researchers involved in these projects acknowledge from the Sixth Framework Programme?

-

d.

What was the scholarly output of these projects in terms of journal articles indexed in Scopus?

Methods

Identification of the projects funded in the Social Sciences and Humanities

A list of projects funded under FP6 was retrieved from the European Union Open Data Portal (2022). Three calls were identified as relevant for the Social Sciences and Humanities: “FP6-Citizens” (144 projects funded), “FP6-Policies” (519 projects) and “FP6-Society” (164 projects). The description of each project (title, keywords and abstract) was examined to identify the projects related to the Social Sciences and Humanities. In case of doubt, the website of the project—if available—was visited to determine its disciplinary extent. In total, 275 projects funded under FP6 were identified as related to the Social Sciences and Humanities.

The projects were manually classified in disciplines and their descriptors analysed to identify the most researched topics. The classification scheme derives from the priority objectives stated in the titles and summaries of the projects. Owing to the significant thematic dispersion of the projects, the classification process was carried out through several iterations. A project could be assigned to one or several key issues.

The explanations included in the summary of the projects were first considered. When such explanations did not mention explicitly a discipline, the information on methodology, scope, research institutions, profiles, etc. was employed to assign the project to a discipline. In some instances, the outputs derived from the project were consulted to confirm the classification. The classification is intended to be simple and is based on the top level of the “UNESCO standard nomenclature for fields of science and technology” (UNESCO, 1974), although some minor additions and changes have been introduced. The classification of projects in disciplines is independent of the object of study, since the latter can be approached from various fields. For example, the issue of “migration” allows an approach from the point of view of its economic impact, but also in terms of social response, law, political science, public administration, education, cultural and social anthropology, history, etc.

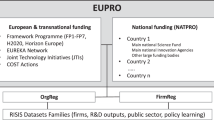

This study is based on information collected from two sources: the CORDIS portal for the identification of Social Sciences and Humanities projects, and Scopus for the retrieval of research outputs acknowledging funding from these projects. For a similar analysis of subsequent FPs, it will be possible to use OpenAIRE, which allows retrieval of the outputs submitted by funded research teams, but this option is not available for FP6.

Retrieval of the bibliographic output of the projects funded in the Social Sciences and Humanities

The next step in the project involved the retrieval of the scholarly output resulting from the projects identified in the previous phase. Scopus was selected as the data source for this part of the study because of its stronger coverage of the Social Sciences and Humanities compared to the Web of Science. In both sources, however, it should be borne in mind that English-language journals are overrepresented to the detriment of other languages (Hug and Brändle, 2017). According to Mongeon and Paul-Hus (2016, p. 219), “Scopus covers less than 25% of journals in both fields [journals in the Social Sciences and Humanities listed in Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory], while WoS covers less than 15%”.

The Scopus database was searched by combining the IDs and the acronyms of the projects in the equation below. This search equation aimed to retrieve the records including either: a) the ID of the project combined with the terms “CT” (standing for Call for Tender), “EC” (standing for European Commission) or “European Commission”; or b) the acronym of the project in any funding field (Scopus has four funding fields: sponsor name, sponsor acronym and grant number):

(FUND-ALL ([ID]) AND (FUND-ALL (CT) OR FUND-ALL (EC) OR FUND-ALL (European Commission) OR FUND-ALL (FP)) OR FUND-ALL ([acronym])

When up to 25 records were retrieved for a project, the records were downloaded for further analysis. We set the threshold at 25 records since this was a number that could be analysed manually without difficulty. However, since project acronyms tend to be vague (e.g., “ABSTRACT”, “AIM” or “ANALOGY”), many searches retrieved large numbers of non-relevant records. When the number of records retrieved in a search was higher than 25, an additional filter was added to the previous equation in order to force the presence of a reference to the funder in the funding field:

AND (FUND-ALL(CT) OR FUND-ALL(EC) OR FUND-ALL(European Commission)

Again, when up to 25 records were retrieved for a project, the records were downloaded. Those searches still retrieving more than 25 records were discarded. As a result of this process 1847 records resulting from 177 projects (64% of the 275 projects identified in the previous phase) were downloaded.

The funding text of each record was examined to decide whether the article had a relationship with the relevant project or not. Finally, 586 records were labelled as relevant and are those analysed in this paper. Acknowledging the assistance and contributions of others is a well-established practice in scholarship. A meta-synthesis of 50 years of research on acknowledgements in the context of scholarly communication (Desrochers et al., 2017) showed that around one-third of the literature on the topic uses acknowledgements to study the effects of funding on research, as well as the performance or productivity of funding bodies or grants programmes.

Although it was not the purpose of this study, this filtering process made evident the lack of homogeneity in the funding texts contained in Scopus. This lack of quality control has been reported in previous studies (Liu, 2020) and shows that automated indexing in bibliographic databases is still far from perfect. Figures 1 and 2 show two examples of these shortfalls. The first example shows a Scopus record including two funding texts (1b): the first corresponds to the funding acknowledgement in the original article (shown in 1c), whereas the second is a bibliographic reference, originally included in the reference list of the published article, possibly listed automatically in the funding field because of the inclusion of the term “funded”.

a Bibliographic reference in Scopus. b Funding field in the Scopus record including the funding text published in the article and a bibliographic reference, included in the reference list of the article, possibly listed automatically because of the inclusion of the term “funded”. c Acknowledgement published in the original article.

The example in Fig. 2 shows the funding text in a Scopus record corresponding to an author bio published in the journal. Again, the inclusion of the term “funded” may have led to the automatic inclusion of the text in the funding field.

Results

Projects funded

Analysis of the research projects funded under the three calls of FP6 resulted in the identification of 275 projects related to the Social Sciences and Humanities out of 10,098 projects funded (2.7%). This figure is slightly higher than the 144 projects obtained from the CORDIS database by Schögler and König (2017 p. 112). Of these 275 projects, 208 (76%) focused on the Social Sciences and Humanities whereas 66 (24%) combined elements of these disciplines with others in the experimental sciences, engineering or technology (Table 1).

Most projects in the Social Sciences and Humanities (116 projects, 42%) lasted between 2 and 3 years, a quarter (25%) lasted between 3 and 4 years and a fifth (21%) lasted between 1 and 2 years (Fig. 3). In contrast, most projects in other disciplines (35%) lasted between 1 and 2 years.

In terms of funding, most projects (52%) were awarded grants of up to one million euros, while a third (34%) received one to two million euros and the remaining 14% received more than two million (Fig. 4). Although there is no clear relationship between the length of the project and the funds awarded, the data follow a power law relationship (r2 = 0.65). In the case of projects in other disciplines, most of them (60%) did not exceed one million euros, although 4% received ten million euros or more, in some cases exceeding 100 million euros.

By discipline, 42% of the projects were in economics and 29% in sociology (Table 2). The projects dealt with a wide range of topics, with those more frequently researched being policy decision-making (19 projects), indicators and metrics (18), migration (16) and governance (16) (Tables 2 and 3).

Analysis of the countries and institutions involved in the projects showed a high level of collaboration. On average, each project involved 7.8 countries and 10.8 institutions. The United Kingdom and Germany were the two countries involved in the largest number of projects, with both countries being present in four of every five funded projects. German institutions were slightly more inclined to assume a leadership role, coordinating 36% of the projects they were involved in, compared to 30% in the case of British institutions. Four additional countries were involved in more than 100 projects each: Italy, Netherlands, France and Spain. There are, however, remarkable differences in the leadership roles assumed by institutions in each country: Italian and French institutions coordinated 31% and 29% of the projects they were involved in, respectively. This percentage dropped among institutions in the Netherlands to 21%. The cases of Spain, Poland and Hungary are more striking: although institutions in each of these countries were involved in more than 70 projects, they only coordinated between 6.1% and 8.5% of them (Table 4).

Regarding institutions, Table 5 lists the 14 research centres involved in ten or more projects each. The list shows that the most active institutions were concentrated in two countries: Belgium (five institutions) and the United Kingdom (five institutions).

Types of acknowledgement

When acknowledging funding from a project, authors may refer to different types of support. In our analysis of the funding texts, four types of acknowledgement were distinguished: direct funding support; utilisation of results from former funded projects as the basis of current research; involvement in conferences and networks resulting from previous projects; and utilisation of datasets or other products resulting from former funded projects.

Acknowledgement of funding

The most obvious acknowledgement refers to the financial support received to accomplish the aims of the research project. This is the case of the two examples in Fig. 5. In both cases, the authors of the article indicate that research was carried out thanks to the grants awarded to the project, although little detail is provided on the specific needs covered.

a Bibliographic record in Scopus of an article published in 2020 acknowledging support from a FP6 research project funded from April 2006 to September 2009. b Bibliographic record in Scopus of an article published in 2019 acknowledging support from a FP6 research project funded from May 2004 to April 2008.

Acknowledgement of a funded project as a previous step to the current research

In some cases, the authors of an article acknowledge a project funded under FP6 as a previous step whose results are the basis for the current research. Figure 6 shows two examples of this kind of acknowledgement. The first corresponds to an article published in 2019 whose results are based on two European Union projects, one of them funded under FP6. In a similar fashion, the authors of the second article, published in 2018, acknowledge early funding from FP5 and FP6.

a Bibliographic record in Scopus of an article published in 2019 acknowledging early support from a FP6 research project funded from April 2006 to September 2009. b Bibliographic record in Scopus of an article published in 2018 acknowledging support from a FP5 project and a FP6 research project funded from May 2004 to April 2008.

Conferences and networks

Some Social Sciences and Humanities projects funded under FP6 included the organisation of conferences that have run over the long term. In some articles, authors acknowledge feedback obtained while attending later editions of these conferences. Figure 7 shows two examples of articles that did not result directly from projects funded under FP6, but acknowledge participation in conferences and networks resulting from those projects. The first article acknowledges feedback obtained from participants in an IMISCOE conference. IMISCOE was a project funded under FP6-CITIZENS that lasted until March 2010. Since then, IMISCOE has consolidated itself as the “largest network of scholars in the area of migration and integration” (https://www.imiscoe.org) and, among other activities, organises an annual conference on the topic.

a Bibliographic record in Scopus of an article published in 2020 acknowledging feedback obtained from participants in a conference resulting from a FP6 research project. b Bibliographic record in Scopus of an article acknowledging feedback obtained from participants in a conference resulting from a FP6 research project.

Datasets and other materials

Finally, some articles’ acknowledgements of FP6 projects are justified by the use of datasets or other materials compiled or prepared in the course of those projects. The first example in Fig. 8 shows a funding text acknowledging the use of datasets gathered in the course of a FP6 project whereas the authors of the second article acknowledge the use of the results of a survey conducted in the framework of a FP6 project.

Scholarly output

After analysing the funding text in the Scopus records, 586 articles were labelled as related to the Social Sciences and Humanities research projects funded under FP6 identified in the previous phase. Specifically, the articles acknowledged support from 116 projects (42% of the total). As shown in Fig. 9, most projects did not publish an article in a journal indexed in Scopus, although we must bear in mind the difficulties experienced in the retrieval of the scholarly outputs described in the methodology. The median number of articles per project was one. However, if the analysis is limited to the 67 projects where Social Sciences and Humanities components were combined with the Experimental Sciences, Engineering or Technology, the median number of articles per project increased to three.

The high level of collaboration observed at the project level, with an average of 10.8 institutions involved in each project, is not reflected in the papers’ co-authorship. On average, each article was signed by authors affiliated to 2.8 institutions (median = 2) (Fig. 10).

Analysis of the articles’ publication dates showed that the effects of research funding in the Social Sciences and Humanities persist in the long term. Although FP6 was active between 2002 and 2006, there are articles published in 2020 that still acknowledge funding from the Programme. The two examples in Fig. 5 illustrate this long-term effect. The first example shows an article published in February 2020 that acknowledges funding from a project funded under FP6-POLICIES from April 2006 to September 2009, i.e., a project that finished 11 years before the date of publication of the article. Similarly, the second example shows an article published in 2019 that acknowledges funding from a project funded in the FP6-CITIZENS programme from May 2004 to April 2008, again 11 years before publication.

Discussion and conclusions

Although Social Sciences and Humanities research was present in Framework Programmes FP4 and FP5, FP6 gave additional impetus to research in these areas by setting a thematic priority specifically devoted to these subjects. The analysis of the three calls more closely related to the Social Sciences and Humanities in FP6 identified 275 projects in these disciplines: three-quarters of them focused on the Social Sciences and Humanities and a quarter combined elements of these disciplines with others in science and technology.

In terms of length, Social Sciences and Humanities projects tended to last slightly longer than projects in other disciplines. On average, they also received less funds than projects in other fields—as described by Kropp (2021), for instance—although this was due to the scattering of funding in other disciplines, with projects being funded with large amounts, sometimes exceeding 100 million euros.

Economics and political sciences were the disciplines with the largest number of funded projects, with gender, governance and policy decision-making being the most researched topics. These results seem to be clearly related to the focus on “socio-economic” sciences on FP4 and FP5 to enhance economic development and the integration process in Europe (Schögler and König, 2017).

Analysis of the countries and institutions involved in these projects showed a high level of collaboration. On average, each project involved 7.8 countries and 10.8 institutions. This feature is the result of a European Union policy that forces projects to be transnational and to include partners from different member states and associated countries in consortia. However, this policy may artificially inflate the size of consortia (Breschi and Malerba, 2011). This high level of collaboration at the project level does not necessarily extend to the scholarly outputs resulting from these projects, which show low levels of institutional co-authorship. The standards for co-authorship in the Social Sciences and Humanities tend to be higher than in the Natural and Life sciences. For instance, Pruschak (2021) observed that “social scientists regard mere data work contributions as not enough for authorship” whereas in the fields of Science and Technology it usually results in co-authorship. Nevertheless, it is important to bear in mind that these results refer to projects funded under FP6, i.e., between 2002 and 2006. In future research we intend to analyse whether this pattern remains stable or changes over the course of the following FPs.

Our analysis has focused on the research outputs of funded projects in terms of scholarly journal articles. The evaluation of outputs and benefits of funded projects is beyond the purposes of this articles. However, our results suggest that funding may have long-term effects on Social Sciences and Humanities research; there are articles published in 2020 that acknowledge funding from the FP6 programme, i.e., more than a decade after the acknowledged project finished. These results suggest that, sometimes, research in the Social Sciences and Humanities take a long time to finish. In addition, publication in the Social Sciences and Humanities entails much longer delays than in Science and Technology (Björk and Solomon, 2013). Examples of acknowledgements of funded projects as a previous step to the current research also illustrate how social scientists and humanists put together funding from different projects in order to tell more complex stories.

The qualitative analysis of the acknowledgements included in the articles offered some rich insights into the types of support provided by research funds. Four types of acknowledgement were identified: direct funding support; utilisation of results from former funded projects as the basis of current research; involvement in conferences and networks resulting from previous projects; and utilisation of datasets or other products resulting from former funded projects.

Finally, our study illustrates the difficulties in retrieving the scholarly outputs of funded projects in order to analyse the performance of FP6. Despite a gradual move towards the use of English, European researchers in Social Sciences and Humanities publish their scholarly outputs in journals in a diversity of languages. In addition, Scopus funding information is heterogeneous, being provided in free text, thus hindering the retrieval of relevant references. The assessment conducted in this study is time-consuming, involving a large amount of manual labour. This is consistent with comments made by Liu (2020), who suggested that funding information in Web of Science is more complete than that in Scopus. However, the worse coverage of Social Sciences and Humanities in Web of Science made us inclined to use Scopus. Despite the difficulties experienced, this article illustrates an approach that we intend to extend to the analysis of subsequent calls (i.e., FP7 and Horizon 2020). We believe a similar analysis can offer us a clearer picture of the performance of EU funds on building a European Research Area in the Social Sciences and Humanities.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Belcher B, Halliwell J (2021) Conceptualizing the elements of research impact: towards semantic standards. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8(183). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00854-2

Björk BC, Solomon D (2013) The publishing delay in scholarly peer-reviewed journals. J Informet 7(4):914–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2013.09.001

Boncourt T (2017) The struggles for European science. A comparative perspective on the history of European social science associations. Serendipities 2(1):10–32. https://unipub.uni-graz.at/serendipities/periodical/titleinfo/2273801

Bornmann L (2012) Measuring the societal impact of research: research is less and less assessed on scientific impact alone—we should aim to quantify the increasingly important contributions of science to society. EMBO Reports 13(8):673–676. https://doi.org/10.1038/embor.2012.99

Breschi S, Malerba F (2011) Assessing the scientific and technological output of EU Framework Programmes: evidence from the FP6 projects in the ICT field. Scientometrics 88(1):239–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0378-x

Chi PS (2014) Which role do non-source items play in the social sciences? A case study in political science in Germany. Scientometrics 101(2):1195–1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1433-1

Chi PS (2015) Changing publication and citation patterns in political science in Germany. Scientometrics 105(3):1833–1848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1609-3

de Rijcke S, Wouters PF, Rushforth AD, Franssen TP, Hammarfelt B (2016) Evaluation practices and effects of indicator use—a literature review. Res Eval 25(2):161–169. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvv038

Desrochers N, Paul‐Hus A, Pecoskie J (2017) Five decades of gratitude: a meta‐synthesis of acknowledgments research. J Assoc Inform Sci Technol 68(12):2821–2833. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23903

Engels TC, Ossenblok TL, Spruyt EH (2012) Changing publication patterns in the social sciences and humanities, 2000–2009. Scientometrics 93(2):373–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0680-2

Engels TC, Starčič AI, Kulczycki E, Pölönen J, Sivertsen G (2018) Are book publications disappearing from scholarly communication in the social sciences and humanities. Aslib J Inform Manag 70(6):592–607. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-05-2018-0127

European Research Council (2022) Statistics. https://erc.europa.eu/projects-figures/statistics

European Union Open Data Portal (2022) CORDIS—EU research projects under FP6 (2002–2006) https://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/dataset/cordisfp6projects

Galsworthy MJ, Irwin R, Charlesworth K, Ernst K, Hristovski D, Wismar M, McKee M (2014) An analysis of subject areas and country participation for all health-related projects in the EU’s FP5 and FP6 programmes. Eur J Public Health 24(3):514–520. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckt075

González EM, Albahari A (2007) Surface transport management projects in the Sixth Framework Programme of the European Union. Transp Res Record 2036(1):58–66. https://doi.org/10.3141/2036-07

Guns R, Eykens J, Engels TC (2019) To what extent do successive cohorts adopt different publication patterns? Peer review, language use, and publication types in the social sciences and humanities. Front Res Metrics Anal 3. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/frma.2018.00038

Hammarfelt B, Haddow G (2018) Conflicting measures and values: How humanities scholars in Australia and Sweden use and react to bibliometric indicators. J Assoc Inform Sci Technol 24(2):924–935. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24043

Heilbron J, Bedecarré M, Timans R (2017) European journals in the social sciences and humanities. Serendipities 2(1):33–49. https://unipub.uni-graz.at/serendipities/periodical/titleinfo/2273802

Henriksen D (2016) The rise in co-authorship in the social sciences (1980–2013). Scientometrics 107(2):455–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1849-x

Hicks D (2004) The four literatures of social science. In: Moed HF, Glänzel W, Schmoch U (eds). Handbook of quantitative science and technology research, Springer. pp. 473–496

Hug SE, Brändle MP (2017) The coverage of Microsoft Academic: Analyzing the publication output of a university. Scientometrics 113(3):1551–1571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2535-3

Kastrinos N (2010) Policies for Co-Ordination in the European Research Area: a view from the social sciences and humanities. Sci Public Policy 37(4):297–310. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234210X496646

König T (2016) Peer Review in the Social Sciences and Humanities at the European Level: the experiences of the European Research Council. In: Ochsner M, et al. (eds.) Research assessment in the humanities: towards Criteria and Procedures. Springer, Basel, 10.1007/978-3-319-29016-4_12

Kropp K (2021) The EU and the social sciences: a fragile relationship. Sociol Rev 69(6):1325–1341. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380261211034706

Kulczycki E et al. (2018) Publication patterns in the social sciences and humanities: evidence from eight European countries. Scientometrics 116(1):463–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2711-0

Kulczycki E et al. (2020) Multilingual publishing in the social sciences and humanities: a seven‐country European study. J Assoc Inform Sci Technol 71(11):1371–1385. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24336

Liu W (2020) Accuracy of funding information in Scopus: a comparative case study. Scientometrics 124:803–811. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03458-w

Mongeon P, Paul-Hus A (2016) The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics 106(1):213–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

Nederhof AJ (2006) Bibliometric monitoring of research performance in the social sciences and the humanities: a review. Scientometrics 66(1):81–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-006-0007-2

Ossenblok TL, Verleysen FT, Engels TC (2014) Coauthorship of journal articles and book chapters in the social sciences and humanities (2000–2010). J Assoc Inform Sci Technol 65(5):882–897. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23015

Ossenblok TL, Engels TC, Sivertsen G (2012) The representation of the social sciences and humanities in the Web of Science—a comparison of publication patterns and incentive structures in Flanders and Norway (2005–9). Res Eval 21(4):280–290. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvs019

Project reporting in FP6 (2004) http://www.hysafe.org/download/63/FP6_project_reporting.pdf

Pruschak G (2021) What constitutes authorship in the social sciences? Front Res Metrics Anal 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2021.655350

Rietschel ET et al. (2009) Evaluation of the Sixth Framework Programmes for research and technological development 2002–2006. https://op.europa.eu/s/vKFa

Schögler R, König T (2017) Thematic research funding in the European Union: What is expected from social scientific knowledge-making? Serendipities 2(1):107–130. https://unipub.uni-graz.at/serendipities/periodical/titleinfo/2273807

UNESCO (1974) UNESCO nomenclature for fields of science and technology. https://skos.um.es/unesco6/

Vallés-Brau JL (2005) Materials research in the Sixth Framework Programme. Solid State Phenom 106:167–172

Van Leeuwen T (2013) Bibliometric research evaluations, Web of Science and the Social Sciences and Humanities: a problematic relationship? Bibliometrie-Praxis und Forschung 2. https://doi.org/10.5283/bpf.173

Watson J et al. (2010) Evaluation of the impact of the Framework Programme on the formation of the ERA in Social Sciences and the Humanities (SSH). https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/9f4cb9f6-f114-4bbb-b0bc-b406e7ccd75c

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the grant PGC2018-096586-B-100 «Redes de colaboración científica en ciencias sociales y humanidades en Europa: análisis de la participación en proyectos y de la coautoría funded» by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and “ERDF A way of making Europe”, by the “European Union”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ardanuy, J., Arguimbau, L. & Borrego, Á. Social sciences and humanities research funded under the European Union Sixth Framework Programme (2002–2006): a long-term assessment of projects, acknowledgements and publications. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9, 397 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01412-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01412-0