Abstract

One might think that the elementary teachings of an instrument should follow uniform planning patterns. The present study shows discrepancies between the models developed by different Spanish conservatories, mainly attributable to the guidelines established by each autonomous community concerning the order of the curriculum markedly influenced by each community’s circumstances. This article analyzes and compares first-year didactic programs in the elementary music teachings of 40 Spanish conservatories within the cello specialty. This work shows significant heterogeneity in planning, marked mainly by the variety of content in planning. The lack of unified criteria and standards for teaching planning is evident in teachers’ freedom to establish the contents and evaluation criteria within the framework of regulations in each autonomous community, whose generality prevents the establishment of standard criteria. It is urgent and necessary to design training plans and standard content that consider improved learning practices and strategies to offer quality training based on common standards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A didactic program is a document prepared by a specific department or area that organizes and structures the knowledge taught in a subject during a school year (Moreno et al., 2019). The peculiarity of music studies, based on individualized teaching or in small groups in instrument subjects, invites teachers to reflect on the contentsFootnote 1 and methodological strategies used in their teaching.

When Spanish students want to dedicate themself to teaching in secondary education, they must earn the official master’s degree of Teacher Training (formerly Course of Pedagogical Qualification or Course of Pedagogical Aptitude). An important part of this training focuses on developing competencies related to teaching planning (realization of teaching planning units). In the case of teachers from either municipal music schools or conservatories, the situation varies since the planning is not organized based on teaching units or planning units. The lack of training for teachers in these centers has minimal impact on the content related to program planning. This situation leads the teachers concerned to develop a sense of ignorance of the structure and elements of the teaching planning documents of an instrument. Some schools have provided specific training for teachers to teach them how to plan, teach, and carry out planning with the minimum content required by the regulations.

The content of the programs analyzed by autonomous communities reveals significant shortcomings, especially in follow-up activities/recovery, resources, and attention to diversity. The shortcomings detected need to be addressed to improve the training programs. From what we have described above, we ask which first cello courses are taught in the different Spanish conservatories. To answer the question, we looked at the differences in the type of content and planning of teaching. The specific objectives for this study were to 1) analyze the situation of teaching the cello in Spain, 2) identify the basic elements of the programs carried out for teaching the cello, and 3) compare and assess the suitability of didactic planning elements for teaching cello.

Background

The Organic Law of Education 2/2006 of May 3 states that elementary music teachers in Spain are considered special regime teachers since they teach a form of art. Article 48.1 states that these teachings “shall have the characteristics and the organization that the educational administrations determine” (p. 43). This lack of concreteness gives each autonomous community in Spain the ability to establish teaching regulations, the curriculum, and planning.

-

Andalucía: The Order of 24 June 2009, which develops the curriculum for elementary music education in Andalucía, establishes in Article 3.3 that the departments will carry out the programs, as well as their content” …objectives, organization of content, the establishment methodology and evaluation procedures and criteria” (p. 7).

-

Castilla and Leon: The programs carried out in the conservatories of Castilla and Leon must include “the objectives, content and assessment criteria for each course of the respective subjects, as well as the learning assessment procedures to be used and qualification criteria” (p. 12942), as can be seen from Order EDU/1118/2008 of 19 June 2008, which regulates the evaluation of elementary and professional music education and evaluation documents.

-

Castilla La Mancha: In the Order of 02/07/2012, which dictates instructions regulating the organization and operation of music and dance conservatories in Castilla La Mancha, the planning must include an introduction, the objectives, the methodology, the contents, evaluation criteria, complementary activities, procedures for continuous evaluation and the criteria, procedures, and timing of the evaluation of the teaching-learning process (p. 21829).

-

Madrid: Madrid advocates “an open, non-rigid planning,” flexible and adapted to the needs of students. Decree 7/2014, of 30 January, widely reflects on the role of planning in the classroom, establishing that its content should include each course’s objectives and evaluation criteria.

-

Murcia: The community of Murcia is specified in Decree 58/2008, of 11 April, which establishes the order and curriculum of elementary music education for this region, that schools develop programs that take into account the needs and characteristics of students (p. 11789).

-

Canary Islands: In the Canary Islands, The Order of 16 March 2018 concretely established that the planning must contain the evaluation criteria, objectives, contents, form of course promotion, didactic methodology, didactic resources,Footnote 2 reinforcement activities, and complementary activities (art. 5.6; p. 9863).

-

Valencian Community: The Valencian community, on p. 37094 of Decree 159/2007, of 21 September, asks for consistency with the established curriculum and with the project of the center on which the planning is based.

-

Asturias: In addition, Decree 57/2007, of 24 May, establishes on page 11958 that, in Asturias, the programs must follow the guidelines found in the educational project of the school, although they must contain at least the following points: content, methodology, evaluation, recovery system and activities Table 1 shows the most representative contents required by the autonomous communities in this study.

Table 1 Content of the programs required by the autonomous communities in Spain.

Given the above data, we ask ourselves, where do we stand? The teaching of the cello in the Spanish panorama has not been examined very much at the pedagogical level and has not often been the specific object of any study or research; this is manifested in the scarcity of studies found after reviewing the literature review for this work (Pérez-Jorge et al., 2020).

In this sense, it is necessary to highlight the work of Etxepare (2011), who focused on cello pedagogy or the teaching of this instrument. This book describes, in detail, the teaching method to be followed by a student from their first class to becoming a cello professional. This work is a world reference in the teaching of this instrument.

Other authors who talk about the programs of the conservatories are Botella and Fuster (2016), who declares that the document that could serve as a guide in the search for information would be the didactic planning, although they clarify that most of them do not talk about methodology but about methods and repertoire.

On the other hand, Bújez (2017) defends that this teaching–learning process of the cello, for a given space of time, course, and students, is reflected in the planning, always written within limits proposed by the educational administrations, and giving space to the idiosyncrasy of the center. According to this author, this document should be open to the necessary modifications during the year, according to the needs that arise.

The research and studies prior to this work carried out on the programs in the Spanish conservatories and their content are very scarce. For a better understanding of the objective, scope, and organization of teaching, we include in Table 2 the most relevant and outstanding aspects of these.

Table 3 reports the findings concerning the meaning and purpose of the study.

It is essential to point out the list of contents and objectives to be taken in each autonomous community. In Tables 4 and 5, the data associated with these two dimensions were collected relating the elementary teachings of the cello and the legislation in force in each of the communities participating in this study. Castilla la Mancha and Murcia do not have specific contents and Andalucía, Castilla La Mancha, and Murcia do not present specific objectives for the elementary teachings of the cello.

Methodology

The methodology used was based on documentary analysis (i.e., search, analysis, and data collection of the different programs selected). This methodology responds to three needs (Vickery, 1970): (1) to know the studies about teaching and planning procedures, (2) to know the elements that cello teachers consider when planning to teach this instrument, and (3) to know the type of information available on instrumental education planning. This methodology provides clean results of relevant data and information. Following Mikhailov and Guiliarevskii (1974) and Pinto (1992), after retrieving the documents, an analytic–synthetic assessment of the content of the documents was carried out.

Perelló (1998) points out that documentary analysis is a dynamic methodological strategy that favors the understanding of documents and reinterprets their meaning and nature. Therefore, we propose:

-

a.

Analyzing and interpreting the regulations that affect and determine the planning models of instrumental education.

-

b.

Reinterpreting the meaning and reasons that justify the planning models (didactic units) used by cello teachers.

Sources of information used for analysis

Two types of sources were used for this study. These sources included official documents (e.g., decrees and regulatory regulations) on how teacher planning affects conservatories and music schools in Spain (N = 6). Cello teachers’ instructions (e.g., planning) were also used (N = 40).

The procedure for collecting information

To obtain the instructions of the teaching of the cello, the web pages of all the Spanish conservatories were accessed, downloading the programs in the case of the published centers and contacting the management teams of the centers in the case of the unpublished centers. The main official pages were accessed to obtain the official documents regulating education. Documents published in non-official languages were not considered for analysis.

Sample

A total of 40 Spanish conservatories from different autonomous communities and provinces from among the more than 200 regulated education centers and authorized centers were included in this study. Within the planning available and considered for the study, only 21 were updated, and 14 did not specify the academic year. As a sample for this study, we have considered the conservatories listed in Table 6. References to the centers will follow the numerical identification code.

Results

For the analysis of the estimated documents, seven basic aspects were considered in the regulations that refer to the structure and planning of education. Specifically, the planning, objectives, content, recovery activities, follow-up activities, and evaluation criteria/minimum evaluation criteria have been analyzed as educational resources and measures to address diversity. See Table 7 for the number of schedules in which each item can be found.

The only dimension analyzed in practically all the programs consulted are the contents (except in the C.P.M. Cartagena, whose planning does not specify any content). Table 8 shows the contents of the first cello to see which ones are taught in the different centers of Spain.

The bow strokes (72.5%), fingering (62.5%), and scales (57.5%) are the three most studied contents in the first cello course in Spanish centers. Moreover, anacrusis (5%), signs of repetition (15%), and agonal (15%) are the least studied. Additionally, the second most frequent dimension in the planning is that of the didactic resources or a list of indicative works, collected in 85% of the planning. As in the rest of the dimensions, for the case of the Andalusian conservatories, the coincidence of contents was observed.

Of the 33 conservatories that use didactic resources in their planning, 100% of them use the Suzuki method one for cello. Another widely used method is the Practical Method for Cello by Sebastian Lee, which appears in 22 of the programs. A great variety of resources were evident, but in addition to those previously mentioned, it is interesting to highlight the use of the Method of the young cellist by Feuillard (considered by 12 conservatories) and of The Cello by Motatu (considered by nine conservatories). In the planning, some of the method content was very difficult, including the book 113 Studies by Dotzauer and the book School of the technique of the bow by Sevcik.

It is important to note that many programs contain only the general objectives and evaluation criteria already established in the regulations of the Autonomous Community concerned but do not specify those specific to the first year of the cello subject. Seven of the programs do not present objectives. Table 9 shows the objectives of the other programs (N = 33).

According to Table 9, 75% of the programs consulted had the objective to adopt a natural and correct position followed by knowing the parts and characteristics of the instrument with 62.5% (both with their respective variants).

Evaluation criteria are another element of the program analyzed. The analysis made it possible to identify the absence of criteria in eight programs. The criteria specified in the other programs refer to general criteria without considering the specific criteria for evaluating the contents and competencies of the first cello course.

Measures dealing with diversity also barely appear in only half of the programs. Most programs refer to the individuality of musical teaching and the need for the teacher to adapt planning to each student’s specific needs. For students with physical difficulties or with different abilities, the planning shows the need to discuss the case with the corresponding department and the school board.

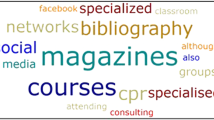

Follow-up and recovery activities are omitted from most programs, with only 10 and 18, respectively. Recovery activities include the tests or exercises that the student must do during the classes to reach the proposed objectives. Other complementary activities included attending concerts and auditions, attending courses and cello masterclass, and participating in orchestras and groups with other instruments (all these aspects, to be developed both inside and outside the school). Many programs also specify that students who repeat a year will attend the repeating course until it reaches the minimum. In some cases, the teacher will have one hour dedicated to the students to attend to those who need some reinforcement to achieve the minimum objectives.

Discussion

The regulations of the Autonomous Communities are pretty clear about the didactic planning of the different subjects taught in the elementary teaching of music. Likewise, according to Botella and Fuster (2016), in the teaching of the cello, “there is no general and unified methodology” (p. 11). Furthermore, this study shows important differences in the preparation of this document in many of the musical educational centers of our country. In many of the documents consulted, we find basic absences, such as the school’s name to which it belongs, front page, index, or school year. In addition, four programs with layout errors have been found, which might suggest that they are copies of other instructions.

The programs consulted are very different in terms of length (ranging from 15 to 90 pages), elements, and configurations. These aspects show an apparent lack of coordination between centers (even within the same Autonomous Community) and a lack of the necessary minimum consensus when planning an education. Objectives, contents, evaluation criteria, and teaching resources are the elements of planning that are most frequently repeated, while elements such as recovery, complementary activities, and measures to address diversity can be improved in many of the programs. There are seven conservatories in which the objectives corresponding to the first course of the cello are not specified; there were two pairs of programs with equal objectives between them.

The body position of the instrument, its parts, and study habits are the most repeated objectives of the 33 programs consulted. Two conservatories have the same bibliographic resources established in the same order. This shows a fairly frequent practice when carrying out the planning; the lack of specific training and competence to adapt the planning to the realities and learning contexts of the different communities encourages malpractice, with consequences effects on the quality of education. If there are no two equal realities, no two equal contexts, and no two equal students, there cannot be two equal programs.

The contents offered in the first-year cello programs of these teachings are different in most of the programs, perceiving that only the scales, bows, and fingering are taught in more than 50% of the conservatories. Evidence suggests that the first cello students of each conservatory learn different things and that everything depends on the place where. In the same line, and due to the lack of unification and joint actions in the planning of cello teachings, students pass the first year having learned different things. There is no common teaching since there are significant differences between what students from different communities learn. Therefore, in the event of a transfer or in the case of access to vocational education, students will be at vastly different skill levels. The Spanish regulations are clear regarding the didactic planning of the different subjects taught in the elementary teaching of music. However, according to Botella and Fuster (2016), in the teaching of the cello, “there is no general and unified methodology” (p. 11). This is evident in this study when preparing this document in many of the musical educational centers of our country.

When studying the list of items present in the first-year cello planning, we found that 95% include contents, 85% include resources, 80% include objectives, and 80% include evaluation criteria. This is in line with the regulations of the various Autonomous Communities, except for teaching resources, which only appear in the Order of 16 March 2018 of the Autonomous Community of the Canary Islands. This confirms Botella and Fuster (2016), who stated that most programs do not talk about methodology, methods, and repertoire. Elements such as recovery, follow-up activities, and diversity measures are areas for improvement in many programs.

As for the design and configuration of the programs, many of the documents consulted have basic absences, such as the name of the school to which it belongs, cover page, index, and the school year. When consulting the regulations associated with these teachings in the different autonomous communities, the production of sound, bows, and the positions are the contents that should be taught in all the elementary conservatories. Data suggests that the first cello students of each conservatory learn different things and that everything depends on the place where they study due to the lack of joint actions around the planning of these teachings. This creates a real disadvantage by creating an incompatibility that can become a problem when it comes to adapting to a new center in the event of a transfer or in the event of access to vocational training. There are also two conservatories with the same bibliographic resources established in the same order. This coincides in part with the current regulations that show that the body position, the instrument’s characteristics, hearing sensitivity, and the repertoire are the objectives that should always be present in the first course of cello plannings.

Following this study, the legislation in each autonomous community should establish general objectives and contents in elementary education for the four instruments of the string family. The lack of such guidelines makes it difficult for conservatory teachers to carry out a program in which, within the freedom of teaching, there is a certain degree of homogeneity throughout the national territory. There is a need for greater coordination between institutions that provide elementary education in different instruments, seeking to unify criteria to improve elementary and vocational education.

Conclusions

The analysis of the situation and the reality of the first cello course has allowed us to conclude that the programs mainly contain five key elements of teaching planning: contents, resources, objectives, evaluation criteria, diversity measures, and complementary and remedial activities. Its development was significantly different between centers; there are differences in course content, and there is no unanimity on the criteria for teaching planning and the organization of cello teaching programs.

The competent education authorities in the field of legislation must establish minimum parameters on which teachers base their teaching programs; the lack of unified criteria leads to significant differences in planning across the country. On the other hand, in some Autonomous Communities, the educational inspectorate review and approves the teaching programs of conservatories, but in others, it does not. This must be done so that there are no manifest inequalities in this article between the different teachings of the same subject. There is also a need to increase specialized conservatory training on how to carry out appropriate planning. There are numerous courses on carrying out planning focused on regulated studies but not on musical studies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

Set of Knowledge and skills that contribute to the achievement of the objectives proposed in a didactic planning for a given educational stage (e.g., bow, strokes, scales, slurs).

Set of books, methods, and works used in a certain stage.

References

Botella M, Fuster V (2016) Un estudio sobre la praxis docente del violonchelo en los conservatorios profesionales de la provincia de Valencia. Vivat Acad: Rev Commun 137:1–22. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2016.137.01-22

Botella M, Escorihuela G (2014) Análisis de la praxis docente de los profesores de las enseñanzas superiores de flauta travesera de la Comunidad Valenciana. El Artista 11:65–87

Bújez V (2017) La planificación docente en los conservatorios de música. Exlibric, Spain

Decree 159/2007, de 21 de septiembre, del Consell, por el que se establece el currículo de las enseñanzas elementales de música y se regula el acceso a estas enseñanzas

Decree 57/2007, de 24 de mayo, por el que se establece la ordenación y el currículo de las enseñanzas elementales de música en el Principado de Asturias. Boletín Oficial del Principado de Asturias, núm. 141, de 18 de junio de 2007, pp. 11955–17032. https://sede.asturias.es/bopa/disposiciones/repositorio/LEGISLACION34/66/14/59776F1BE8A54C32928175F1CE9C8F17.pdf. Accessed 21 Jun 2021

Decree 7/2014, de 30 de enero, del Consejo de Gobierno, por el que se establece el currículo y la organización de las enseñanzas elementales de música en la Comunidad de Madrid, Spain

Decree 58/2008, de 11 de abril, por el que se establece la ordenación y el currículo de las enseñanzas elementales de música para la Región de Murcia, Spain

Etxepare I (2011) Pedagogía del Violonchelo. Música Boileau, Spain

García E (2015) El Violonchelo en la Región de Murcia: una Aproximación Histórica y una Propuesta Didáctica para la Enseñanza de Grado Elemental. Doctoral thesis. Universidad de Murcia, Spain

Organic Law Education 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 4 de mayo de 2006

Lorenzo R (2009) Los contenidos de la educación pianística en los conservatorios de música. Una propuesta integrada. Doctoral thesis. Universidad de Granada, Spain

Lorenzo-Quiles O, Muñoz-Mendiluce S, Soares-Quadros JF (2018) Estudio comparativo de métodos de iniciación al violonchelo utilizados en los conservatorios de música andaluces. Implicaciones para el profesorado. Psychol Soc Educ 1:37–54. https://doi.org/10.25115/psye.v10i1.1069

Mijáilov I, Rudzhero G (1974) Curso introductorio de informática/documentación. Fundación Instituto Venezolano de Productividad, Venezuela

Moreno J, Jaén M, Labella M (2019) Análisis de la importancia de la programación didáctica en la gestión docente del aula y del proceso educativo. Revista interuniversitaria de formación del profesorado: RIFOP 33:115–130

Order de (2012) de la Consejería de Educación, Cultura y Deportes, por la que se dictan instrucciones que regulan la organización y funcionamiento de los conservatorios de música y danza en la Comunidad Autónoma de Castilla-La Mancha. Diario Oficial de Castilla La Mancha, núm. 129, de 3 de julio de, pp. 21825–21838. https://docm.castillalamancha.es/portaldocm/descargarArchivo.do?ruta=2012/07/03/pdf/2012_9763.pdf&tipo=rutaDocm Accessed 21 Jun 2021

Order de 16 de marzo de (2018) por la que se establece la ordenación y el currículo de las enseñanzas elementales de música en el ámbito de la Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias. Boletín Oficial de Canarias, núm. 59, de 23 de marzo de, pp. 9859–9921. http://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/medusa/edublog/cpmsantacruzdetenerife/wp-content/uploads/sites/122/2018/03/orden-ensenanzas-elementales.pdf Accessed 21 Jun 2021

Order de 24 de junio de (2009) por la que se desarrolla el currículo de las enseñanzas elementales de música en Andalucía. Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía, núm. 135, de 14 de julio de, pp. 1–120. https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2009/135/boletin.135.pdf Accessed 21 Jun 2021

Order EDU/1118 (2008) de 19 de junio, por la que se regula la evaluación de las enseñanzas elementales y profesionales de música y los documentos de evaluación. Boletín Oficial de Castilla y León, núm. 124, de 30 de junio de, pp. 12938–12986. https://bocyl.jcyl.es/boletin.do?fechaBoletin=30/06/2008

Perelló J (1998) Sistemas de indización aplicados en bibliotecas: clasificaciones, tesauros y encabezamientos de materias. In: Magán JA (ed.) Tratado básico de biblioteconomía. Universidad Complutense, Spain, pp. 200–203

Pérez-Jorge D, Rodríguez-Jiménez M, Marrero-Rodríguez N, Pastor-Llarena S, Peñas MM (2020) Virtual Teachers’ Toolbox (VTT-BOX)—the experience of the Costa Adeje International School and the University of La Laguna. Int J Interact Mobile Technol 14(13):212–229. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v14i13.14109

Pinto M (1992) El resumen documental: principios y métodos. Pirámide, Spain

Vickery B (1970) Techniques of information retrieval. Butterworths, London

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all music schools and music conservatories for their collaboration with this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Data curation: PH-D, OADR, DP-J. Formal analysis: PH-D, OADR. Investigation: PH-D, VG-C, OADR, DP-J. Methodology: PH-D, DP-J. Project administration: PH-D, VG-C. Resources: PH-D, VG-C, DP-J. Supervision: OADR, DP-J. Validation: PH-D, OADR, DP-J. Writing—original draft: PH-D, DP-J. Writing—review & editing: PH-D, OADR, VG-C, DP-J.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The characteristics of the study did not require the participation of human beings. No approval from the ethics committee of the University of La Laguna was required.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hernández-Dionis, P., Pérez-Jorge, D., Gisbert-Caudeli, V. et al. The teaching of the cello in Spain: An analysis of the planning frameworks used for teaching in conservatories. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9, 132 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01162-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01162-z