Abstract

This qualitative case study is part of the international research project ESCaPE (Evaluating Scientific Advice in a Pandemic Emergency) and aims at understanding how expert advice has been sought, produced and utilized in the management of the Covid-19 emergency in Italy in 2020. Italy was the first country after China having to face the devastating effects of the Covid-19 soon to be pandemic. The state of national emergency was declared on January 31st, 2020, and the Italian Government sought expert advice as an important resource in the management of the pandemic. The Covid-19 crisis in Italy witnessed the emergence of different expert advisory groups: some envisaged by the law; some instituted ad hoc and tasked to deal with specific aspects of the emergency; and others that were already in place before the pandemic but that came to play a crucial role during the unfolding of the outbreak. This case study relies on a mix of both primary (stakeholder interviews) and secondary data collection (official documents and communications by expert advisory bodies, ministerial decrees, and policy documents). Our research shows three main findings: (a) the near-complete overlap of technical advice and political response in the first phase of the pandemic in Spring 2020, with a key policy role played by the advice provided by the Technical and Scientific Committee (CTS); (b) a predominance of epidemiologists and infectious disease specialists over social scientists in the mobilisation of experts for the management of the crisis in Italy; (c) a shift in containment policies from an emergency-based, very strict, national lockdown in the spring of 2020, to proactive risk-informed colour-coded regional restrictions in the fall and winter of 2020. Our case study ends at the end of 2020 and provides an overview and encompassing representation of the mobilization of experts, and of selected types of evidence, to manage the unprecedented health emergency, in year 1 of the Covid-19 pandemic in Italy. Our findings suggest that expert politics can lead to the confirmation of knowledge hierarchies that privilege hard sciences, and corroborate prior literature indicating that economic and social expertize has not been well integrated into public health expert advice, constituting a major challenge for policymaking during a health emergency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic provides an unparalleled opportunity to observe and evaluate how scientific advice is sought by policymakers, translated in policy measures, and accepted by the public, in a highly scrutinized situation of global emergency. This qualitative study is part of the international research project ESCaPE (Evaluating Scientific Advice in a Pandemic Emergency) and aims to evaluate the role played by expert advisory bodies during the Covid-19 outbreak in Italy in 2020, and to understand how expert advice has been sought, produced, and utilized in the design and implementation of Covid-19 containment measures in Italy in in 2020. The Italy case study is particularly interesting as Italy represents the first country in the world, after China, having to face and manage the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in 2020, with the highest degree of uncertainty regarding the new pathogen (Severgnini, 2020).

Background

Italy’s political system

Italy is a parliamentary republic with a degree of federalism at the regional level. The executive branch of power resides with the Council of the Ministers, presided over by the Prime Minister (art. 92 of the Italian Constitution) (Constitution of Italian Republic, English Version). The Government has the authority to initiate legislation, yet the main legislative branch of power resides within Parliament, divided into the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate of the Republic (art. 55). In normal times, ministers present bills to the Parliament for discussion, however in cases of urgency or emergency, as in the context of the pandemic, ministers can pass ‘decrees’ (“decreti-legge”), official orders that have the force of law. The President of the Republic is elected by the Parliament and is in place for seven years. The President of the Republic is the guarantee of the Italian Constitution, does not participate directly in the executive, legislative, judicial branches of power, but nominates the Prime Minister, generally - although not always, as noted below - on the basis of the results of the elections.

Italy’s political history over the last three decades has been marked by the emergence of technocratic governments as an institutional response to political crises. (Pastorella, 2016) The first technocratic government in Italy was led by Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, a former Bank of Italy governor, and was formed in 1993. This was a highly unstable socio-political moment of Italian history, when the country was torn by mafia massacres, political corruption scandals (initiated by the 1992 “Clean Hands” investigation), and consequent social tensions and deligitimation of political institutions. Ciampi’s government mandate by President of the Republic Luigi Scalfaro was specifically to create a government of “social cohesion” and above political parties, which could enable the transition to a new electoral law leading to new political groups and dynamics which could bring stability to the country. Ciampi’s cabinet remained in place for little over a year until May 1994 and, after a short interlude with the first Silvio Berlusconi’s government in 1994, it was followed by Lamberto Dini’s technocratic government in January 1995. Dini’s (another former Bank of Italy governor) cabinet remained in place for one year and 4 months. After a longer interlude, the technocratic formula was reinstated in 2011 with Mario Monti, a former European Commissioner, who was nominated to the role by President of the Republic Giorgio Napolitano with the mandate to implement austerity policies necessary to face the wider Euro crisis. Then, in 2018, Giuseppe Conte—for the first time in Italian political history, a university law professor—was given by the President of the Republic Sergio Mattarella the mandate to form a bipartisan government with the mandate to overcome a political impasse between the populist Five-start movement and the Northern League. As his mandate was renewed in 2019 after a political crisis, the coalition changed, now including the Democratic Party. While himself a technocrat, both Giuseppe Conte’s first government in 2018 and second government in 2019 were formed mostly by politicians, with only a few technocrats. More recently, Mario Draghi (former European Central Bank Governor) replaced Conte in February 2021 as Italy’s Prime Minister, with the task to administer the EU recovery fund and boost Italy’s post-Covid recovery. Overall, the technocratic cabinets in Italy’s republican history have offered a quick response to large systemic crises, with the aim to create a bipartisan political consensuses. Yet, technocratic governments are by many considered anti-democratic, as they replace direct elections and, in the case of the Italian political system, the Prime Minister is nominated by the President of the Republic not on the basis of the results of the elections. As such, these governments are known to be short-lived with quickly eroding public trust and political consensus.

Covid-19 timeframe

Two Chinese tourists in Rome were hospitalized at Spallanzani hospital in Rome in late January 2020 for viral pneumonia (Severgnini, 2020). At that time, the new pathogen did not have a name, however there were worrying reports of a new coronavirus coming from Wuhan, China, causing a new type of viral pneumonia. The new pathogen would be given its official SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) name by the The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) on February 11th, 2020 (WHO, 2020). As the two tourists tested positive for the new coronavirus on January 31st, 2020, a national state of emergency was declared, and all flights to and from China were suspended (Council of Ministers Declares State of Emergency, January 31st, 2020). On the same day, the Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte, in agreement with the Minister of Health Roberto Speranza, as set out in the Italian national preparedness plan described below, delegated to the Head of the Civil Protection Department Angelo Borrelli the management of the emergency and the task of convening of the Civil Protection Operative Committee (Sole 24 ore, 2020). The first native case (known as Patient 1 from Codogno) was recorded on February 19th, 2020 (ANSA, 2020a). After a first phase of attempted contact tracing and case isolation through mobilization of the army, the national government escalated the restrictive measures initially applied only to the affected areas, and declared a national lockdown on March 9th, 2020 (Sole 24 ore, 2020). The national lockdown lasted in Italy until May 5th, 2020, and was one of the most stringent lockdowns in Europe, with major restriction on individual movements, and the closing down of factories and all production lines, which were not considered absolutely essential (Horowitz, 2020).

Methods

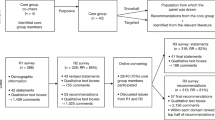

This case study employs a qualitative methodological approach, and relies on a mix of both primary and secondary data collection and analysis. Ethical approval for the project was obtained by King’s College London on September 1, 2020 (reference number MRA 19/20 -21073) and all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines. The primary data collection involved nine key stakeholder interviews. The sample was designed to ensure theoretical representativeness (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007), hence to cover the views and opinions of experts involved in the management of the Covid-19 pandemic in Italy in 2020. Our definition of expert is one who belongs to an expert committee, using the analytical distinction first drawn by Eyal (2013) between “experts” and “expertize”, which allows us to distinguish on the one hand between the “actors” who are professionals recognized as being “experts” and those professionals who are not (necessarily) recognized as being “experts” but who have the capacity to do so. In Italy the management of the pandemic adopted a classic top-down approach with the constitution of key expert committees, of which we interviewed key members. In Italy, although there was a proliferation of independent “experts” who talked to the media, only experts who belonged to expert committees contributed to the production of policy advice in 2020. Hence we focus only on the recognized professional experts as they were the key players in the production of expert advice for policymaking in Italy in 2020.

In our sample, we interviewed members of the Technical and Scientific Committee (Comitato Tecnico-Scientifico, CTS), members of the Economic and Social Committee (Comitato di esperti in materia economica e sociale, CES), members from the Italian National Institute of Health (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, ISS), Italy’s main public health research center, and members of the national bioethics committee (Comitato Nazionale per la Bioetica, CNB).

The nine semi-structured interviews were conducted between October and December 2020 and followed a general protocol and topic guide based on the goals and aims of the wider ESCaPE project (https://escapecovid19.org/), which was adapted to the specific role and function of the respondent. The interviewees were asked to describe their role and function within the pandemic response, the changes (if any) in their role between the first and second Covid-19 wave in 2020, their views on the production and use of evidence in in the managemenf of the pandemic, and their views on the relationship between expert advice and policy decision-making. The interviews were conducted over Zoom, in Italian. They were video recorded in agreement with the participants, following their verbal informed consent to the project and in line with KCL ethical guidelines. The data are stored in a University online research repository according to GDPR regulations. The Italian transcripts were obtained through an automated service, curated and fact-checked collectively by the members of the research team, with relevant excerpts translated into English by the authors. Recruitment was not devoid of difficulties, as not all stakeyholders were equally receptive to our invitations. In November–December 2020 Italy experienced a critical surge of Covid-19 infections. The stakeholders we contacted were directly involved in providing advice to the government, and many of them had severe time limitations due to high workload, and/or had other reservations in speaking to researchers about their experience as Covid advisors. With the result that, while some experts were keen to speak with us and would also actively refer others, therefore, facilitating recruitment through snowball sampling, others did not respond to our invitations, while others who had accepted withdrew their participation shortly before the interview was scheduled to take place. The timeline for collection of data begins with the declaration of international emergency of the WHO and the confirmation of the first two cases of coronavirus in Italy (January 30th, 2020) and terminates with the end of calendar year 2020 (Fig. 1). The secondary data collection relied on official documents and communications by expert advisory bodies, ministerial decrees and governmental documents. Figure 2 lists the type of documents produced and analyzed within the framework of this research.

Italy preparedness plan and key advisory expert groups

The Italian pandemic preparedness plan

Under Italy’s constitution, every citizen has the right to health (Article 32, Constitution of the Italian Republic). This right is enacted through the Italian National Health System (Sistema Sanitario Nazionale-SSN), a system of structures and services aimed at protecting citizens’ health established in 1978 through law n.833 (Law December 23rd, 1978), and based on the collaboration between the State and the twenty regions (of which five enjoy greater autonomy than the others based on historical and geographical reasons: Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Sardinia, Sicily, Trentino-Alto Adige, and Val d’Aosta). The State establishes the Essential Levels of Assistance (ELA) that must be guaranteed on the entire national territory free of charge or upon payment of a participation fee, while the twenty Regions enjoy full autonomy in programming and managing healthcare practices in the relevant territory of their competence.

In 2003, following the outbreak of the A/H5N1 virus in Asia, the WHO recommended that all countries prepare a pandemic preparedness plan following the established guidelines and WHO recommendations of 2005/2006 (WHO, 2005). Italy developed a pandemic preparedness plan in 2006 according to the 6 pandemic phases identified by the WHO. This plan sets out clear organizational guidelines in case the Council of Ministers declares a state of emergency (National Plan for Preparedness and Response 2006). Of direct relevance for this case study, the preparedness plan details that—in the case of an emergency—coordination functions will be the responsibility of the Prime Minister, upon advice from the Department for Civil Protection. The European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) keeps an updated list of the preparedness plans on its website (ECDC List of influenza pandemic preparedness plans). According to our analysis, there seemed to be a general momentum in Europe to draft national pandemic responses plans following the outbreak of the H5N1 influenza virus in Asia in 2003, however that momentum drive petered out afterwards. While some preparedness plans were updated somewhat more recently (France in 2011, Finland in 2012, Germany in 2016), others had been not updated since the 2005/2006 WHO recommendations, including the Italian pandemic preparedness plan. Although Italy was not the only European country failing to update its preparedness plan, it was the first to the bear the brunt of the epidemic in 2020, and it was the European country for which the lack of updating had the most momentous consequences. The lack of an updated plan was at the center of a heated media debate and public scrutiny in 2020, which may have contributed to our difficulties in recruiting key stakeholders for our interviews (Giuffrida and Boseley, 2020). In January 2021, Italy submitted a new preparedness plan to respond to the eventuality of a pandemic influenza.

The Technical and Scientific Committee

The committees and institutions involved in the management of the health emergency evolved during year 1 of the pandemic in Italy (Fig. 3).

During the first wave in the spring of 2020, the main advisory body for the production of expert advice in Italy was the Technical and Scientific Committee (CTS), set up by the Head of the Civil Protection Department, with Ordinance n. 630, February 3rd, 2020 (Ordinance n. 630, Civil Protection Department, 2020a). The setting up of this committee was envisaged by the Italian preparedness plan, as well as the provision that the committee was to remain in place for the entire duration of the national emergency (still in place at the time of revising this article, December 2021). According to its terms of reference, the CTS was vested with a clear consultative role of technical and scientific support to the Civil Protection Department. The members of the CTS were nominated by the Head of the Civil Protection Department upon suggestion of the Ministry of Health, on the basis of representation criteria, i.e., as representatives of the major national authorities and major national institutions with technical competencies in the management of infectious disease outbreaks (Ordinance n. 630, Department of Civil Protection, 2020). As the composition of the CTS, which initially consisted of 14 members, reflected the top management of the main national authorities for health and emergency management in Italy, women were not present in the initial composition of the CTS, as much as they were excluded from any of the senior roles represented in the committee. Because of this striking (although not surprising, for Italian standards) gender imbalance, the composition of the CTS was redefined in April of 2020 with the introduction of six new female members (Ordinance n. 663, Department of Civil Protection 2020) for a total of twenty members (this number was later brought down to 14 with the appointment of the new chair Franco Locatelli with the Ordinance n. 751 of March 17th, 2021.

The Special Covid Commissioner

On March 18th, 2020, the Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte nominated Domenico Arcuri as “Special Covid Commissioner” (Decree of the President of Council of Ministers, March 18, 2020). The Special Covid Commissioner’s role was one of “primus inter pares”, or “first among equals” within the experts tasked with the management of the Covid-19 pandemic in Italy. Arcuri was previously CEO of Invitalia, Italy’s National Agency for Inward Investment and Economic Development (https://www.invitalia.it/eng). External to all expert committees, and responding directly to the Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte, key tasks assigned to Arcuri in his role as Special Covid Commissioner included the organization, acquisition, and support of the production of goods necessary to counter the health emergency, including the acquisition and distribution of medicines and personal protective equipment. In the first phase of the pandemic in 2020, the Special Covid Commissioner issued several decrees. Among the most significant ones, Arcuri introduced a cap on the retail price of facemasks at 0.50 euro (Ordinance 1/11 of Special Covid Commissioner, April 26, 2020)—in the spring of 2020 in Italy, facemasks in scarce supply were sold for up to 40 euros each (La Repubblica, 2020). The Special Covid Commissioner also nominated several Deputy Commissioners tasked with the implementation of the emergency measures at the regional level. During the second wave in 2020, the Special Commissioner Arcuri played an important role in the initial planning of the vaccination campaign: he issued a decree identifying in the military airport of Pratica di Mare southwest of Rome the hangar for storage and distribution of the vaccines. On March 1st, 2021, Arcuri was replaced by General Francesco Paolo Figliuolo as new Special Covid Commissioner, with the main task of revising, and accelerating, the vaccination campaign. The appointment of an army general as Special Covid Commissioner was meant to be a strong sign by the newly installed government led by the Prime Minister Mario Draghi to invest full speed in the vaccination campaign (Reuters, March 1st, 2021). A complete list of the decrees issued by the Special Covid Commissioner is available on the official government webpage (https://www.governo.it/it/dipartimenti/commissario-straordinario-lemergenza-covid-19/cscovid19-ordinanze/14421).

The Control Room of the Health Ministry

The Cntrol Room of the Health Ministry is a consultative body of the Italian government, which was set up with decree on April 30th, 2020 with the following mandate: “to provide a weekly updated classification of the level of risk of uncontrolled and unmanageable transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the Regions/autonomous provinces” (Decree of Health Ministry, April 30, 2020). Unlike the CTS, whose setting up was envisaged by the Italian preparedness plan, the Control Room was not (it was created later). The April 30th decree is key to understanding the management of the epidemic in Italy in the second phase, as it sets out the key monitoring activity of the spread of the virus. It also demarcates the shift from an emergency response based on external data coming from China and mathematical modeling predictions based on those data, to an evidence-based response with risk-based scenarios based on Italian data produced by the regions.

State/Regions conference

The State/Regions conference is a permanent collegial organ of the Italian government aimed at supporting institutional collaboration and political negotiations between the central Government and the Regions, a role that was maintained also in the current pandemic. Representatives of the Regions supported the interests of the regional entities in all negotiations regarding Covid-19 measures, from the re-opening of economic and social activities in summer, to the re-organization of public transport and the development of guidelines for the administration of the vaccine. The State/Regions conference acquired a special significance in the second wave of the pandemic in 2020, as discussed in section “Within-group dynamics and management of disagreement”.

The Economic and Social Council (CES)

On April 10th, 2020, the Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte set up a Council of experts on economic and social matters” (also known as “T task force for phase 2”, or “Colao Committee” from the name of its chair, Vittorio Colao) with the mandate to investigate the impact of the pandemic on socioeconomic activities, and to provide key recommendations on how to support the Italian social and economic recovery after the lockdown). The CES was initially composed of 17 experts of social and economic matters, entrusted by the Prime Minister (Decree of President of the Council of Ministers, April 10, 2020). Many of these experts on economic and social matters came from academia and several had a strong international standing and recognition. The committee delivered in June 2020 a 77-page report for “Italian recovery” in the period 2020–2022 (CES Report, 2020). The report provided very specific recommendations in three key areas: (1) digitalization and innovation; (2) green revolution; (3) gender balance, diversity and inclusion in the workplace. These were referred to in the report as the three “strengthening cornerstones” (assi di rafforzamento), the three key areas on which the experts recommended the Italian government to invest for a successful recovery and positive transformation of the country after the lockdown. However, these recommendations did not have a direct impact on national decrees, in stark contrast with the advice provided by the CTS, as discussed in section “Evidence-based containment policies: a focus on natural sciences and hard data”.

Findings

The qualitative data resulting from the semi-structured interviews was analyzed through an abductive approach via thematic analysis, allowing us to combine theory-derived deductive categories with themes emerging from the data (Angeli et al., 2020; Timmermans and Tavory, 2012). For the deductive part, analysis of both primary and secondary data followed a protocol shared among all 19 case studies of the overarching EScAPE project, aimed at identifying common themes, similarities and differences across the countries involved in the project. Inductive analysis was based on thematic analysis of the qualitative material.

Evidence-based containment policies: a focus on natural sciences and hard data

One of the key tasks of the CTS throughout the pandemic was to screen and scrutinize available evidence, as well as to distinguish between reliable and non-reliable scientific data, and identify key findings and actionable knowledge from the wide amount of Covid-related research which was churned out daily in the early phases of the pandemic. To this end, the CTS operated a daily review of the latest medical and epidemiological evidence. Names of well known scientific international peer reviewed journals were often mentioned in our interviews. International key reference points that were consistently referenced for the work of the CTS were the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, the World Health Organization, and Imperial College London, for the epidemiological projections that were also key to guide UK policies.

Within the government buildings of Lungotevere we would meet every day. At that moment it is important to say we were studying what was happening—or what we were thinking was happening—in China. That was the information we had and that we obtained through official channels, not only studying what was published. We are talking about the beginning of February. Apart from those [data] we did not know anything. We were looking at what was happenining in China and were thinking what we should do when the moment of what was happening there [in China] would happen here.

This quote referring to the type of information on which the CTS relied in the early phases of the Covid emergency in Italy speaks to the uniqueness of the Italian situation in early 2020; when there were no data available to help the CTS manage the disease’s emergence in Italy except those coming from Wuhan. The data coming from China, as highlighted by our stakeholders, were met with some degree of skepticism as they were perceived to contain “some degree of untrustworthiness” (inaffidabilità). The fact that the Chinese were constantly changing how they were counting their “confirmed” coronavirus deaths generated confusion and possibly distrust as there was the perception that the Chinese were covering up the actual numer of deaths (Feuer, 2020).

In early February the CTS produced and presented to the government a first national health plan in response to the Covid-19 health emergency. In this first plan, the members of the CTS made mathematical predictions (for a timeframe of up to a year) of possible scenarios with different levels of infection ratios, namely RT = 0, RT = 1, RT > 1,15; RT > 1,30, RT > 2, and laid out the corresponding measures, which were to be adopted in each scenario. As emerged in our conversations with members of the CTS, this first plan based on mathematical predictions included three stages: the third—a worst-case scenario—made a hypothesis of 70,000 deaths in the first year (on January 7th, 2021, the number of Covid-19 related deaths in Italy was indicated as 77,291, thus exceeding the worst-case scenario prediction of the CTS for the first year of the pandemic in Italy). This first plan was never released in the public domain, likely because of the highly sensitive and potentially panic-inducing information it contained (Luna, 2020; Guerzoni and Sarzanini, 2020).

In early April of 2020, a working group within the CTS was set up and tasked to develop an occupational health risk assessment method for the industrial sector (production, manufacturing) to enable a tailored exiting from national lockdown and management of subsequent outbreaks. The working group of the CTS collaborated closely with the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies (Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali) to produce industry-specific protocols, on the basis of prevention and precaution. Hundreds of business-specific protocols were developed. Often, systemic interventions aimed to mitigate the risk of contagion were suggested. On the one hand, cafés were required to stop serving sugar packets with espressos, but to deliver instead individual sugar packets to patrons upon request. On the other hand, stores and supermarkets, for their part, were required to install plastic panels at checkouts, with a view to enhance the protection of workers as well as customers. These business-specific protocols have informed the management of the second wave and, to the best of our knowledge, represent a unique occupational health risk provision in the management of the epidemic among the landscape of international Covid-19 management provisions.

Although Prime Minister Conte had set up the Economic and Social Committee specifically to gather the input of social scientists to support the recovery phase, after the end of the first lockdown in May 2020, it appears that the report produced by CES was not widely distributed or significantly used in subsequent policies. Our interviewees from CTS did not seem to be aware of or had plainly forgotten that an economic and social council existed. In the words of one of our stakeholders:

To be honest, that group had a very short and tormented life, it must have lasted perhaps two or three weeks.

In fact, the committee’s activity lasted much longer, from April 10th, when the committee was first set up, to June 15th, 2020, when the final report was delivered, although the committee has, to the best of our knowledge, never been officially dismantled. One respondent even mentioned that the CES mission and work was something that “everybody can do in the country”. Another participant elaborated by mentioning that:

While analysis of the epidemiological progression of the virus relies on specific competencies, analysis of business and socio-cultural recovery involves the entire parliament. The CES was therefore introduced in a very active and aggressive arena of competing actors and experts.

On the contrary, the CTS was consistently perceived as a body with hyperspecialized, elite knowledge, which “does not deal with subjects that can be debated”. Interesting to note, though, that after the resignation of Prime Minister Conte on January 26th, 2021, the new government led by Prime Minister Mario Draghi nominated Vittorio Colao as Minister of Technological Innovation and Digital Transition on February 13th, 2021, an unprecedented type of Ministry in Italy. In an interesting turn of events, hence, the first of the three key areas of the report by the Task Force chaired by Colao (“digitalization and innovation”) seems to have had an impact on policy, although after the conclusion of the mandate of the Prime Minister who had first appointed the committee.

Similar—although not identical—considerations as those formulated for the CES apply to the Italian Committee for Bioethics (Comitato Nazionale di Bioetica, CNB). Unlike the CES, the CNB was not set up in response to the pandemic, but is a governmental body that has been in place in Italy since 1990, tasked with the mandate to produce reports to address the ethical and legal problems that arise from progress in scientific research and technological applications on life. However, its members are nominated directly by the Prime Minister, as it was the case for the CES. Also similarly to the CES, the CNB was very productive in 2020, releasing several reports on a variety of topics, from criteria for allocating scarce life-saving resources, to criteria for prioritizing vaccines, to criteria for triage in a pandemic emergency (Italian Committee for Bioethics - Opinions on Covid-19). Incidentally, the CNB was never tasked directly by the government to work specifically on pandemic-related issues, but, as customary for this committee, the committee selected their own topics and constituted working groups to deliver specific reports. It seems however that the CNB reports produced in 2020 did not have, overall, a direct policy impact. The only exception was the report on vaccine prioritization, which outlines that priority should be given to the most “vulnerable” defined as those at higher risk of contracting Covid-19 because of their profession (i.e., healthcare workers), age or existing comorbidities (Italian Committee for Bioethics. Opinion on ‘Vaccines and Covid-19’).

Overall, we found that the expert advice that supported the management of the pandemic in Italy saw a strong predominance of epidemiologists and infectious disease experts. The input of socioeconomic experts, ethicists and other non-health disciplines did not have a substantial impact on policy decisions. To note, all the expert committees discussed in this case study worked completely pro-bono. This added to the gender bias dimensions of the committees and expert advice, as it has been highlighted by some of our key interviewees.The fact that the very intense work required in all committees was unpaid and went in addition to the ordinary tasks of the involved professionals has had a strong crowding out effect on potential female participants and disproportionally burdened the already enrolled female experts, who typically have caring duties and cannot easily travel. In the words of one of our stakeholders:

It was really the usual “old boys’ club”, as all the experts enrolled were all men, highly efficient, perfectly functioning, wealthy, at the height of their mental and physical energies and without any further burden. Not because they do not have any family ties, but without any burden beyond their absolute devotion to the job. They were having so much fun doing all of this. They would address the highly important task at stake with responsibility and sense of duty but in a sort of narcissistic, self-enhancing way. Thinking “how good we are”. Instead, when I received the call the first thing that came to my mind was the crushing responsibility and the enourmous amount of work, efforts and commitment I was facing. They were thinking instead about the praise and appreciation they would receive.

This quote speaks of the different ways in which additional (pro-bono) work was perceived by male and female members of the expert committees set up to manage the Covid-19 crisis in Italy, together with the internal and external rewards that go with it. In fact, the gender imbalance within the expert committees was intensified by the fact that most women could only participate remotely because of caring duties intensified during the pandemic, while male colleagues would most often be able to meet in person.

Delphi’s oracle and Moses’ tablet: the role of the CTS minutes in the management of the pandemic

The advice provided by the CTS—in the form of the meetings minutes—played a key policy advisory role in the management of the pandemic in Italy, covering a quasi-legislative function. In that early phase of the outbreak in Italy in March of 2020, the Government would request the CTS minutes in word format instead of pdf format to facilitate drafting of the decrees. One of our key stakolders provided an apt analogy: the CTS was perceived in this first phase as the “Delphi oracle” and the minutes as “Moses’ tablets”. The CTS members, however, resisted being portrayed as policymakers by the media, with some stakeholders publicly threatening to resign unless the clear consultative role of the expert committee was maintained.

We have become legislators. The problem is we don’t want to be legislators, we only want to be a consultative tool. We are trying hard to keep our function of consultative group however it’s not our own strength but others’ weaknesses which transforms us into something else.

And:

Our task was always to provide a series of elements on which the politicians could decide; we provided a risk analysis. We gave the elements to evaluate the risk, we were not able to judge other elements. It’s the politician who is tasked with the synthesis [of different elements]. This was and has always been our reference point.

In the minutes n. 65 of May 3rd, 2020, the CTS firmly advanced the “necessity of a norm that safeguards the work of the CTS”, in absence of which the Committee threatened to resign (Minute n. 65, CTS, for Foundation Luigi Einaudi 2020). As far as we are aware, this norm was not discussed in the public arena, and the CTS continued to be perceived as a Delphi oracle as long as it came to unanimous decisions (more on this in section “Within-group dynamics and management of disagreement”), and as long as it was convenient for the politicians to rely heavily on expert advice. Members of the CTS and of the CSE were forbidden from talking to the media by strict non-disclosure agreements. One interviewer from the CTS recalls signing non-disclosure agreements “twice a day”, while a member of the CSE indicates that it was strictly prohibited for them to have any contacts with the media in any capacity, “neither as members of said committees nor at a personal level”. Members of the CTS and the CES, therefore, never talked to the media, except for the committee chairs, but even then, only on very few and pre-agreed occasions. This position was challenging for many members of the CTS and CES, especially for those participating in other public activities or holding academic posts. These strict non-disclosure clauses imposed on the technical experts may have led to a proliferation of unofficial or non-appointed experts becoming regular guests in news channels and TV shows. Italian citizens felt a desperate need for information in the midst of a highly uncertain and frightening crisis, and the media grappled to satisfy it. Throughout 2020, a plethora of virologists, immunologists and epidemiologists regularly appeared on TV as consultants on different pandemic-related topics. The opinions shared by these independent experts were often divergent and contradictory, leading to heated live arguments and discussions, as well as questionable declarations, such as famously that the Covid-19 virus was “clinically dead” in the summer of 2020 (Agenzia Italia, 2020). This proliferation of independent experts talking to the media likely contributed to generate a situation of general confusion and misinformation in the public opinion, which undermined the ownership of, and trust in, expert advice in the pandemic. Italy, a country traditionally characterized by a high degree of perceived “trustworthiness” of scientists, for the first time witnessed a diminishing trust in scientists in 2020, as emerging from the biannual survey sent out from Observa, the observatory for science in society of the University of Bologna (Observa, 2021).

Initially, the minutes of the CTS meetings were not made available to the public. According to our stakeholders, this decision was based on the fact that the content of the meetings was particularly delicate, as the CTS was making projections about the evolution of the pandemic, based on data coming from China and on mathematic modeling, including some quite concerning scenarios (which would later be revealed as underestimates) in terms of numbers of deaths. According to the chair of the CTS, the expectations on the minutes of the meetings had been “too high” and it was incorrect to refer to the minutes as “classified” (secretati) as, technically, they were never classified. They were, instead, kept confidential (“riservati”) to avoid panic (AND Kronos 2020). This distinction may not have been well explained by the media. The decision to avoid the disclosure of the minutes of the CTS to the public was highly contested. After a spirited debate in the public, the Government decided to grant access to the foundation “Ludovico Einaudi”Footnote 1 to five of the most important minutes of the CTS, which were published on the website of the Foundation on August 6th, 2020. Later, on September 4th, 2020, the Department of Civil Protection published all 95 min of the CTS meetings held between February 7th and July 20th, 2020. From that moment on, all CTS minutes have become available on the website of the Department of Civil Protection, although with a 40-day delay from the date of the corresponding meeting.

There was an extensive debate in the Parliament, an extensive debate in the government. In the end, the decision was the following: The Minutes are public. But from the moment of writing up the minutes [to when they are published] there needs to be at least 45 days in between. […] So in practice there’s a margin of a month and a half which is simply somewhat strategic. […] It’s clear the minutes need to remain public and be available to be viewed but should be given to the public opinion’s feast [messi in pasto all’opinione pubblica] only after the debate is over.

Hence, a solution was reached, which included a “cooling off” period between the date of the meeting, and the publication of the minutes. This cooling off period was the agreed compromise between the request to publish the minutes, and the need to get things done in the midst of a health emergency without having to discuss every single decision. “Democracy and management of health emergency” do not always go hand in hand, as one of our key stakeholders put it.

Within-group dynamics and management of disagreement

The specification of the CTS’ mandate did not include a provision outlining how decisions were to be reached. The CTS minutes were always signed unanimously in the first phase of the pandemic. Although there was not an explicit framing of issues in terms of values—the committee’s points of reference for decision-making were still exclusively scientific—a mediation of different positions was taking place within the CTS, but without an explicit acknowledgement of the different values informing the different positions, as discussed in section “Discussion”.

To the question of how disagreement within the committee was managed, one of our key stakeholders responded:

Swearing, lots of swearing and bad words. But the important thing was that one [to achieve consensus]. In a way, we could say we were operating a bit union-like, the end-point was to find a common denominator to conciliate different positions. Up until now, there hasn’t been a single minute which has not been signed unanimously.

The “union-like” mode of working mentioned in this quote as a reference point for reaching an agreement is a clear and easily relatable reference point for Italian ears. Italy has a long history and tradition of unions, with a mode of working, which includes the participation of each and every one, making for long and heated discussions, with the aim to reach a compromise, that could be palatable to all stakeholders.

Another key theme emerging from our interviews is the unprecedented level of openness in Italy in terms of inter-institutional cooperation: data that pre-Covid would have required layers and layers of burocreatic approval to be shared between institutions in pre-pandemic times, were now being shared “via whatsapp”. Hence a new, positive collaborative spirit seemed to emerge, prompted by the unprecedented perceived urgency of the situation and the feeling of shared responsibility across the committee members.

The first example of disagreement within the CTS took place in late October of 2020, in relation to the debated issue of closing down gyms and pools (Sarzanini, 2020). School opening/closure also became a topic of heated disagreement in December of 2020, with the chair of the CTS, Agostino Miozzo, publicly talking with the media about the “short-sighted decisions” of the government to close schools and referencing data about mental health issues (“cabin fever”) resulting from protracted lockdown for younger generations (Fregonara, 2020).

We know school is a potential point of contagion but in truth contagion doesn’t take place primarily within school, but takes place before and after school when kids congregate. Schools have rigid rules in place [to avoid contagion]. Students wear masks, they sanitize their hands, keep physical distancing in place. Unfortunately, some governors [of regions] have found a sort of shortcut, that of closing down schools, on the basis that closing down schools reduces congregating on public trasport.

Instead, as the CTS had been suggesting since May 2020, reducing crowding at peak times on public transport could have been achieved through focused investments to expand public transporation capacity and by staggering school opening and closing times. The decision not to stagger school start times and end times with consequent congregation of students on public transport and outside of schools led to a heated controversy around the persistency of remote schooling at high school level (13 years old and older) in Italy. This seemed to be a sore topic for our stakeholders, with noted tensions between the central government and regions.

In the second wave of the pandemic in Italy in 2020, disagreements within the CTS became more frequent. An example was the disagreement in the CTS over which measures to adopt during Christmas break (Guerzoni and Sarzanini, 2020bis). The second wave of the pandemic was also characterized by the emergence of a unique arm-wrestling between the central government and regional-level politics. This led to heated conflicts, with some regions not respecting the algorithm that had been put in place at central level to evaluate the level of regional risk and the corresponding local restrictions. One example was the case of Abruzzo, a region in Southern Italy that was assigned to the “red zone” (highest restriction level) on December 12th, however the Governor of Abruzzo issued a counter-order that placed it into the “orange zone” and allowed restaurants and cafés to be open for take-away as well as commercial business to operate. The Administrative Regional Tribunal (TART) of the City of Aquila (capital of the Abruzzo region in Southern Italy) subsequently suspended the order by the President of the Region and the Region entered the “red zone” (ANSA, 2020bis). The frequent conflicts in the second wave of the pandemic in Italy between the central government and regional politics led to a destabilization of the central government, which was evident in the political crisis which led to the Prime Minister Conte resigning on January 26th, 2021. As emerged from interviews with our key stakeholders, there was a perception that an effective management of the epidemic could not be “democratic”; when it started being so in the second wave of the outbreak in 2020, the “arm-wrestling” between central government and region contributed to the collapse of the government. The inability of the CTS to achieve consensus in the second phase of the pandemic as well as its implications for the CTS’ perceived responsibility and role in the management of the pandemic will be investigated more in depth in section “Discussion”.

Shift in containment policies: from emergency-based national lockdown to proactive, risk-informed, color-coded regional restrictions

In the summer of 2020, the management of the epidemic was, temporarily, under control at the national level, and the Ministry of Health issued a 110 pages report titled “Prevention and response to Covid-19: evolution of strategy and planning in the transition phase for the autumn-winter season”. This document (dated August, 12th, 2020) laid out four different scenarios for the fall and winter months, based on different levels of transmission of Covid-19 in the population (Urbani et al., 2020). The document was updated in October 2020 with specific indications as to which actions were to be put in place to contain the spread of the virus on the basis of a number of elements, called “indicators”, which, through an algorithm, determined four different risk-scenarios with corresponding restrictive measures in place for each scenario (Fig. 4). From that moment on, the updated “Prevention and Response to Covid-19” document represented the main point of reference for Italy’s response measures, thus informing the regional lockdowns during the second wave in the fall and winter of 2020. The CTS itself, in its official minutes, has often pointed out that this document constitutes the technical instrument against which response activities shall be measured (see for example CTS minute n. 122, October 30th, 2020, available here: https://www.fondazioneluigieinaudi.it/i-verbali-del-comitato-tecnico-scientifico/).

The introduction of the Ministry of Health “Control Room” in April 2020 enabled the bi-directional knowledge exchange underpinning the relationship between state and regional authorities and marked an increasingly regionalized approach to the management of the pandemic. This new approach was aimed at avoiding a second national lockdown while tailor-making restrictions around local needs.

From November 3rd, 2020, the 20 Italian regions started producing weekly data on the spread of SARS-Cov-2 at the local level. Data are sent by each region to the Italian National Institute of Health (ISS), which analyzes the data on the basis of 21 indicators of risk level divided into three sections: (a) monitoring capacity; (b) diagnosis, track and tracing capacity; and, (c) hospitals and healthcare services’ capacity. Such indicators are then analyzed by an algorithm that, through an estimation matrix, produces a final risk assessment. The weekly final risk assessment produced by the Italian National Institute of Health is sent to the CTS, which expresses an opinion on the epidemiological curve—this intermediate step is referred to by the legal phrase: “having taken into account the opinion of the CTS” (sentito il parere del CTS)—and sends a recommendation to the Ministry of Health. The Ministry is then tasked with drafting a summary which, on the basis of the level of risk identified by ISS and evaluated by the CTS, places the regions and autonomous provinces into four different risk-scenarios (low, medium, high, very high—white, yellow, orange and red, respectively, depicted in Fig. 4), which define what kind of restrictive measures need to be adopted in each region. To note that the ISS is the main national public health research center in Italy (Italian National Institute of Health Mission, 2021). The ISS has played a key role in the management of the pandemic in Italy in terms of analysis of data determining each region’s level of risk and the subsequent restrictions in place. Within the ISS, there were a number of other ISS expert working groups, which were set up in response to the Covid-19 outbreak in Italy and had very specific roles. Among the most active was the ISS working group on Epidemiological Data, Diagnostic and Microbiological Surveillance and Preparedeness. The complete list of the ISS Covid-19 working groups is available here: https://www.iss.it/web/iss-en/iss-for-covid-19.

While during the first wave in the spring of 2020, the impact on the economy of lockdown and stringent containment measures was not taken into account by the CTS, the second wave was managed with a much stronger awareness of trade-offs between the need to contain the virus’ morbidity and mortality, and to support the economy and safeguard the population’s well-being and mental health.

For sure in some way the political, value-based aspect has penetrated the scientific aspect and in some ways, I think this has led to the erosion in part of the consensus within the [CTS] committee.

And also:

We are still writing [the minutes] as we used to write them. We keep saying that the juridical-administrative connotation of the committee has not changed. However, the socio-political connotation of the [CTS] committee has changed.

Hence, while the CTS has strived to maintain its medical-epidemiological characterization, these trade-offs have necessarily come into play also during the second phase of the pandemic. The combination of different factors, including the introduction of different values to the management of the Covid-19 crisis, the inability of the CTS to achieve consensus which emerged in the fall and winter of 2020, and the introduction of other expert committees and players in the management of the health crisis, such as the Control Room and the governors of the regions—have led to a perceived diminishment of the moral responsibility of the CTS in the management of the pandemic in Italy, as discussed more in depth below.

Discussion

During the first wave in 2020 (February through April) the overlap of technical advice and political response in Italy was near-complete. In this first phase, the decision-makers (the Prime Minister, the Ministry of Health) fed daily questions and problems to the CTS, to which the committee was required to respond and provide solutions, based on the available empirical evidence. The government closely followed the recommendations put forward by the CTS in their policies (decrees). There was an active effort spearheaded by the politicians themselves to take the “politics” out of the management of the pandemic through the use of expert knowledge. Although this was not unique to Italy, in our case study this has been vividly illustrated by the direct use of the minutes provided by the CTS meetings in the text of the decrees during the first phase of the pandemic (Fig. 5). The “cut and paste” feature of the CTS minutes seemed to imply that the advice produced by the CTS was “policy ready”, as the members of the CTS had in a sense stripped away all the uncertainties relative to the science and produced something that was ready to be used in policy. According to this interpretation, the members of the CTS have not only played the role of “issue advocates” (Pielke, 2007)—where the defining characteristic of issue advocates is a desire to reduce the scope of available choice, often to a single preferred policy outcome among many possible outcomes, without necessarily being explicit about about the value judgements that this type of choice implies—but of policymakers. This role, however, was not entrusted to the experts without resistance, as members of the CTS repeatedly tried to push back against their perceived role as policymakers and to reiterate their purely technical and consultative role, as noted above. Their attempts were however not entirely successful. The very close adaptation of the minutes of the CTS meetings into decrees in this first phase of the pandemic became an object of extensive reflection for the members of the CTS, who saw a discrepancy between the consultative role of their committee (as per the terms of reference) and the way their recommendations were being used as executive orders by policymakers. As put by our key stakeholders, the policymakers’ unwillingness to be in charge transformed the CTS’s role from consultative into legislative: because when the advice of the CTS meetings is close to being “copied and pasted” into a law decree, the CTS factually becomes a quasi-legislative body.

The type of discomfort experienced by CTS members towards a “forced upon” political role and responsibility is well recognized in the literature. While policymakers may be “tempted to keep pushing experts to make those [difficult] judgments for them, this is generating discomfort [in the experts], and may well compromise the viability of the newfound reliance on experts as a model to (re)introduce into “normal” policymaking” (Boin et al., 2020, pp. 342–343). The overlap of technical advice and political response is a well-established phenomenon described in the political responses to emergencies, when politics resorts to expert advice and to expert-based policy, or “expert politics” (Iles and Montenegro de Wit, 2020). Similarly, the “following the science” claim was a common thread in the first phase of the pandemic, described also in the UK context as well as in other countries (Horton, 2020). Lavazza and Farina (2020, p. 5) write that “Overall, this delegation of power and of responsibility to experts has allowed leaders and governments to lighten their own responsibility toward society”. This delegation however appears to be temporary, as the role of the CTS evolved towards a diminished perceived responsibility in the second phase of the pandemic in Italy in 2020. The diminished perceived responsibility was signaled by the entrance of “new players” in the field (the Control Room principally, but also the governors of the regions) and by the emergence of disagreement, which put an end to the “Delphi oracle” unanimous verdicts of the CTS.

The question of expert disagreement has emerged as a key aspect in devising public health policies during the pandemic. Our definition of expert was provided at the beginning of this article as the expert who is affiliated to an expert committee. This was the type of expert decision-making used in Italy to manage the pandemic, with a classic top-down approach. Although there were independent experts talking to the media about issues, those lie beyond the scope of our case study as their advice did not feed into recommendations or policymaking in the first year of the pandemic in Italy. Within the top-down nominated experts, there is another, narrower, issue of disagreement. As emerged from our interviews, there was not a clear way of managing disagreement laid out in the terms of reference of the CTS. In the first phase of the pandemic, the members strove to achieve unanimous recommendations and largely succeeded in doing so. This was possible because there was a clear, although tacit, consensus, on the goal of the policies: saving the highest possible number of lives from Covid-19. There were no other values in place that needed compromising, as economic and other types of considerations (e.g. psychological, mental health) came a distant second. The consensus on the single preferred policy outcome as the unanimous recommendation provided by the CTS meeting, which was always obtained in the first phase of the pandemic, broke apart in the second half of 2020, with the emergence of a range of possible, viable, policy outcomes, based on a different, although always implicit, weighting of the three key public health policy values—liberty, equality, and utility. In a recent article, we discuss the ethics value compass in public health policies, and show, through a comparative analysis of Italy and the UK, how the policies in place in Italy consistently ranked utility (i.e. saving highest possible number of lives) above liberty. Hence, Italy adopted a very cautious approach, which resulted in one of the strictest, if not the strictest lockdown in Europe (Angeli et al., 2021). The disagreement that experts displayed in the second phase of the pandemic in 2020 can be understood by ascribing different weights to the three key values in public health policy.

In Italy, the knowledge hierarchies in the management of the health emergency strongly favored evidence coming from expert knowledge in epidemiology and infectious diseases. In the first phase of year 1 of the epidemic in Italy (February - May 2020), the main type of evidence used by the CTS was mathematical modeling based on data coming from China. In the second phase (October - December 2020) mathematical modeling was still widely relied upon, although it was based on data produced weekly by Italian regions, and fed into the production of local risk-based scenarios, which through the use of a specific algorithm, determined the type of restrictions in place. In general, in our case study there seemed to be a shared perception that “soft” evidence and expert knowledge could be left to the political domain. While knowledge about the progression of infectious diseases, epidemiology and crisis management is considered highly specific, the political and sociological evaluations of social scientists and ethicists were perceived to overlap to a much larger extent with policymakers’ assessment and core competencies, hence redundant. In addition, there are known difficulties in representing social and economical knowledge as “politically neutral”, contrary to scientific knowledge drawn from natural sciences (Frickel and Moore, 2006) and there seemed to be some lingering confusion about the mandate of the CES committee. It might be that something that came to be seen as Prime Minister Conte’s own personal project, the CES, became an object of partisan criticism.

Our findings corroborate the literature describing how economic and social expertise are often poorly integrated into public health expert advice, constituting a major challenge for policymaking during a health emergency (Bjørkdahl and Carlsen, 2019). In Italy, expert politics has clearly led to the confirmation of knowledge hierarchies and power relations that see a predominance of hard sciences over social sciences. The reasons behind the much stronger emphasis on some scientific disciplinary fields over others are multifaceted: policymakers were focused on managing the public health emergency rather than on mitigating long-term repercussions of lockdown measures, especially during the first wave in the Spring of 2020. The narrow defining of the boundaries of the Covid-19 pandemic to a health emergency only, by governments, shaped the type of knowledge and evidence that could be mobilized in the management of the crisis, to the detriment of the social sciences. We have seen this clearly at play in our case study, where for most of 2020, the only goal of the policies in place for the management of the Covid-19 crisis was saving the highest possible number of lives, whereas the consideration of the economic and social consequences of the same policies came a distant second.

The proliferation of independent experts that emerged in parallel in Italy in the second phase of the pandemic in 2020 can be possibly linked to the perceived vacuum of transparency of the CTS, caused by the non-disclosure agreements and the media investigation—now a formal legal investigation (De Lorenzo, 2020)—into the non-disclosure of the first health emergency plan formulated by the CTS in February of 2020. The diminishing trust in scientists recorded in Italy by the Observatory for Science in Society of the University of Bologna was explained by the respondents as caused by the multiplicity of the recommendations produced by scientists, the lack of consensus registered at all stages of the pandemic, and the perceived lack of transparency in the motives of scientists, which left space open for speculations of conspiracy theories (de Melo-Martin and Intemann, 2018). Another key feature of the second phase of the pandemic in Italy is the changing role of epidemiological data. While in the first wave, characterized by a national lockdown, the data produced by the regions were used retrospectively to analyze the level of risk, in the second wave of the epidemic in Italy regional data acquired a new, operational role, and were used prospectively to inform the level of risk of each region thus determining the level of restrictions in place. Italy has therefore seen a clear shift in the management of the pandemic from an emergency response mode in the first wave (when the only data available were those coming from China), to an evidence-based, data-informed approach in the second wave of the Covid-19 outbreak in 2020.

Finally, the high level of public support for the government’s measures in the first phase of the pandemic in Italy waivered as soon as the acute emergency was over. The strong political consensus that characterized the first wave proved itself tenuous, while members of parliament beginning to criticize the government’s choices in the management of the epidemic, leading to the resignation of the Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte at the end of January 2021. This type of instant revisionism is not rare after emergencies, nor is the decreasing public support to government a unique feature of our case study, as outlined by Kaniasty and Norris (2004). In the second year of the Covid-19 pandemic, political crises are evident in many countries in Europe and beyond, although Italy is the only country—to date (January 2022)—where the political crisis has directly led to a change in government.

Conclusions

This case study adopted a qualitative methodological approach and relied on a mix of both primary and secondary data collection and analysis, to investigate how expert advice has been sought, produced and utilized in the management of the Covid-19 pandemic in Italy in 2020. The primary data collection involved nine key stakeholder interviews. The secondary data collection relied on official documents and communications by expert advisory bodies, ministerial decrees, and governmental documents, released in the year 2020. The Italy case study is particularly interesting as Italy represents the first country after China having to face and manage the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. The Italy case study is therefore unique in the way the country had to deal with the highest degree of uncertainty regarding the new pathogen. There are three key features of the management of the pandemic in Italy, which emerge from our analysis of the data:

-

i.

The near-complete overlap of technical advice and political response in the first phase of the pandemic in the spring of 2020;

-

ii.

The shift in the management approach to the pandemic from a national lockdown in the spring of 2020 to a prominently regionalized approach in the fall and winter, and leading into 2021;

-

iii.

The confirmation by expert politics of knowledge hierarchies that privilege hard sciences to the detriment of soft sciences (social sciences and humanities).

Our analysis ends at the end of 2020. It is neither exhaustive nor necessarily complete, as we are very much still in the midst of the pandemic as we finalise this article, however our case study provides what we believe is an accurate snapshot and representation of the mobilization of experts, and of selected types of evidence, to manage the unprecedented health emergency, in year 1 of the Covid-19 pandemic in Italy. An interesting follow up from our case study would be to investigate the decision, on February 13th, 2021 of the Italian President of the Republic, Sergio Mattarella, to constitute a “Public Health” Technical Government led by a “technical” Prime Minister Mario Draghi (former Head of the European Central Bank). In a new critical juncture of health emergency, Italian politics resorted again to expert-based policymaking. As outlined in the background section, Italy has a long history of technocratic governments going back to the early 1990s. However, these governments are known to be short-lived with quickly eroding public and political consensus. This should not come as a surprise: as outlined in this case study, as soon as the peak of the health emergency is perceived to be over, partisan differences emerge and experts’ advice, as well as their trustworthiness and impartiality, are called into question. The active effort by Italian politicians to take the “politics” out of the management of the pandemic by resorting to expert knowledge was not by any means unique to Italy. Quite on the contrary, this has emergence as a key feature of the mobilisation of expert knowledge in the management of the Covid-19 health emergency across many different countries, with different political systems, throughout the world. This finding, we believe, could become a lesson for future emergencies. Expert-based politics can only be a temporary solution for politicians. The continued resorting to expert-based advice beyond the strict limits of the emergency can lead to diminished trust in experts with longstanding consequences for science. Finally, our findings corroborate prior literature indicating that economic and social expertize has not been well integrated into public health expert advice, constituting a major challenge for policymaking during a health emergency.

Data availability

The qualitative data collective through the interviews as well as the policy documents analyzed are stored in a university online research repository according to GDPR regulations.

Notes

The Einaudi foundation is a private research center that promotes the dissemination of liberal values in Italy, first and foremost an open and constructive dialogue about facts and ideas.

References

ADN Kronos August 7th, 2020, CTS: ‘Minutes confidential, not classified, to avoid panic’ (CTS: ‘Verbali non segreti ma riservati per non creare panico’) https://www.adnkronos.com/cts-verbali-non-segreti-ma-riservati-per-non-creare-panico_1BmmRbsVWzSMl1EddHvXLB. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Agenzia Italia (2020) Sono più scienziato io di tanti altri, anche in Cts, dice Zangrillo https://www.agi.it/cronaca/news/2020-06-01/cosa-pensano-virologi-virus-morto-zangrillo-8784242/. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Angeli F, Camporesi S, Del Fabbro G (2021) The Covid-19 wicked problem in public health ethics: conflicting evidence, or incommensurable values? Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8(1):1–8

Angeli F, Raab J, Oerlemans L (2020) Adaptive responses to performance gaps in project networks. In: Braun T, Lampel J (eds). Research in the Sociology of Organizations. Emerald Publishing Limited, vol. 67, pp. 153–178

ANSA (2020a) Coronavirus: un contagiato in Lombardia. (Coronavirus: first infected case in Lombardy). February 21st, 2020) https://www.ansa.it/sito/notizie/cronaca/2020/02/21/coronavirus-un-contagiato-in-lombardia_dda62491-4ae1-40af-9cd4-e7dc8402b493.html. (Accessed, Jan 23, 2022)

ANSA (2020bis) Covid: Abruzzo, zona rossa per un giorno, negozi chiusi-Abruzzo-ANSA.it. December 12th, 2020 Available at: https://www.ansa.it/abruzzo/notizie/2020/12/12/covid-abruzzo-zona-rossa-per-un-giorno-negozi-chiusi_feb8d8ce-3bf8-41eb-bc3a-6128bc211d88.html. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Bjørkdahl K, Carlsen B (2019) Pandemics, publics, and politics. Staging Responses to Public Health Crises. Palgrave Pivot, Singapore

Boin A et al. (2020) Beyond Covid‐19: five commentaries on expert knowledge, executive action, and accountability in governance and public administration. Can Public Adm 63:339–368

Constitution of Italian Republic, English Version. Available at: https://www.senato.it/documenti/repository/istituzione/costituzione_inglese.pdf. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

De Lorenzo G (2020) Piano segreto, ora c'è la data ‘X’. Il governo finisce in tribunale. Il Giornale, December 10th, 2020 https://www.ilgiornale.it/news/politica/piano-segreto-ora-c-data-x-governo-finisce-tribunale-1908807.html. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Decree of Health Ministry (2020) Available at https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/05/02/20A02444/sg. (Accessed, Jan 23, 2022)

Decree of Ministry of Interior (2020) (Decreto del Ministero dell’Interno, 20 Aprile 2020) https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/04/16/20A02169/sg. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Decree of the President of the Council of Ministers (2020) Decreto del Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri, 10 aprile, 2020 https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/04/11/20A02179/sg. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Eisenhardt KM, Graebner ME (2007) Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. Acad Manag J 50:25–32

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control - List of influenza pandemic preparedness plans (2021). Available at https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/seasonal-influenza/preparedness/influenza-pandemic-preparedness-plans. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Eyal G (2013) For a sociology of expertise: The social origins of the autism epidemic. Am J Sociol 118(4):863–907

Feuer W (2020) ‘Confusion breeds distrust:’ China keeps changing how it counts coronavirus cases. CNBC February 26, 2020 https://www.cnbc.com/2020/02/26/confusion-breeds-distrust-china-keeps-changing-how-it-counts-coronavirus-cases.html. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Fregonara G (2020) Schools: Miozzo (CTS) says the government is short-sighted. Scuola: Miozzo (CTS) Governo Miope. Corriere, December 17th, 2020 https://www.corriere.it/scuola/secondaria/20_dicembre_17/scuola-miozzo-cts-governo-miope-citta-che-sono-pronte-riaprano-97bf529e-408a-11eb-b55d-be40d0705ed1.shtml. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Frickel S, Moore K (eds.) (2006) The new political sociology of science: Institutions, networks, and power. Univ of Wisconsin Press

Giuffrida A, Boseley S (2020) Italy’s pandemic plan ‘old and inadequate’, Covid report finds. The Guardian, August 13, 2021 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/13/italy-pandemic-plan-was-old-and-inadequate-covid-report-finds. (Accessed: Jan 3rd, 2022)

Guerzoni M, Sarzanini F (2020a) Covid in Italy: the secret plan of the government: here are the three scenarios outlined in February. (Covid in Italia, il piano segreto del governo: i tre scenari delineati a febbraio). Corriere. 8 settembre 2020. Available at: https://www.corriere.it/cronache/20_settembre_08/Covid-ecco-piano-segreto-governo-tre-scenari-delineati-febbraio-c9b3ad06-f14b-11ea-9f2b-89b4229fc5bf.shtml. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Guerzoni M, Sarzanini F (2020bis) Italy: red or orange for Christmas? The fracture within the CTS (Italia: zona rossa o arancione a Natale, e rischio assembramenti. Il CTS si spacca). Corriere, December 20th, 2020 https://www.corriere.it/cronache/20_dicembre_15/italia-zona-rossa-o-arancione-natale-cts-maggiori-controlli-evitare-assembramenti-c75e2ce8-3ebc-11eb-9172-c7bb2a56a969.shtml. (Accessed: Jan 33rd, 2022)

Horowitz J (2020) Italy Announces Restrictions Over Entire Country in Attempt to Halt Coronavirus. The New York Times, March 9, 2020 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/09/world/europe/italy-lockdown-coronavirus.html. (Accessed, Jan 23, 2022)

Horton R (2020) Offline: science and politics in the era of Covid-19. Lancet 396:1319

Iles A, Montenegro de Wit M (2020) Who gets to define ‘the Covid-19 problem’? Expert politics in a pandemic. Agri Hum Value 37:659–660

Italian Committee for Bioethics. Opinion on ‘Vaccines and Covid-19: Ethical aspects on research, cost and distribution’ (2020). November 27th, 2020 Available at: https://bioetica.governo.it/media/4234/p140_2020_riv_vaccines-and-Covid-19-ethical-aspects-on-research-cost-and-distribution.pdf. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Italian Committee for Bioethics–Opinions on Covid-19 (Comitato Nazionale per la Bioetica-I pareri del CNB sul Covid-19). Available at: http://bioetica.governo.it/it/documenti/i-pareri-del-cnb-sul-Covid-19. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Italian Council of Ministers declares the state of emergency. (Consiglio dei ministri dichiara stato d’emergenza) (2020). Available at: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/02/01/20A00737/sg. (Accessed Jan 23, 2022)

Italian National Institute of Health (2021) Our Mission (Istituto Superiore della Sanità, la nostra missione). Available at: https://www.iss.it/web/iss-en/mission. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Italy’s National Plan for Preparedness and Response to an Influenza Pandemic, February 10, 2006 Available at: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_501_ulterioriallegati_ulterioreallegato_0_alleg.pdf. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Kaniasty K, Norris FH (2004) Social support in the aftermath of disasters, catastrophes, and acts of terrorism: altruistic, overwhelmed, uncertain, antagonistic, and patriotic communities. In: Ursano RJ, Norwood, AE, Fullerton CS (eds.), Bioterrorism: psychological and public health interventions. Cambridge University Press. pp. 200–229

Lavazza A, Farina M (2020) The role of experts in the Covid-19 pandemic and the limits of their epistemic authority in democracy. Front Public Health 8:356. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00356

Law December 23rd, (1978), n. 833. Institution of the National Health System. Istituzione del Servizio Sanitario Nazionale, Available at: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/dettaglioAtto?id=21035&completo=true. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

List of Ordinances of Special Covid Commissioner (2021). (Presidenza del Consiglio. Covid19 Ordinanze del Commissario Straordinario). Available at: http://www.governo.it/it/dipartimenti/commissario-straordinario-lemergenza-Covid-19/csCovid19-ordinanze/14421. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Luna R (2020) Il piano anti Covid c’era. Ma i tecnici decisero: “Va tenuto segreto”-la Repubblica. 5 settembre 2020 Available at: https://www.repubblica.it/cronaca/2020/09/05/news/il_piano_anti_covid_tenuto_segreto-266283298/. (Accessed: Jan 3rd, 2022)

de Melo-Martín I, Intemann K (2018) The fight against doubt: How to bridge the gap between scientists and the public. Oxford University Press

Minutes of CTS Covid-19 for Foundation Luigi Einaudi (I verbali del Comitato Tecnico Scientifico Covid-19) Fondazione Luigi Einaudi. Available at: https://www.fondazioneluigieinaudi.it/i-verbali-del-comitato-tecnico-scientifico/. (Accessed: Jan 23rd, 2022)

Observa, Science in Society (2021) Vaccini anti Covid-19 diminuisce lo scetticismo https://www.observa.it/vaccini-anti-covid/. (Accessed: Jan 3rd, 2022)

Ordinance n. 11/2020 of Special Covid Commissioner, (April 26th, 2020). Ordinanza n. 11/2020. Il Commissario Straordinario per l'emergenza Covid-19, Domenico Arcuri, ha firmato l'Ordinanza n. 11/2020 che fissa i prezzi massimi di vendita al consumo delle mascherine facciali (TheSpecial Covid-19 Commissioner, Domenico Arcuri, signs the decree n. 11/2020 which establishes the maximum costs for facial coverings). Available at: https://www.governo.it/it/dipartimenti/14520. (Accessed Jan 23rd, 2020).

Ordinance n. 630, Civil Protection Department, February 3rd, 2020.ORdinanza n.630, Dipartiemnto della Protezione Civile. Primi interventi urgenti di protezione civile in relazione all’emergenza relativa al rischio sanitario connesso all’insorgenza di patologie derivanti da agenti virali trasmissibili- Available at: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/02/08/20A00802/sg. (Accessed, Jan 23, 2022)