Abstract

This paper looks at how the British media addressed the issue of migration in Europe between 2015 and 2018, four years when the topic was high on news and political agendas, due to the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ and the UK’s debate on Britain’s relationship with the European Union and free movement of people. Based on a sample of 400 articles from two national newspapers, The Guardian and The Times, the paper compares the content and discourse between the left-wing and right-wing press. The paper argues that media representations turn refugees into ‘migrants’ and portray them as either a threat to the national economy and security or as passive victims of distant circumstances. The study historicizes these media narratives and reveals that the discourse they employ advances the racialised mix of knowledge and historical amnesia and reproduces the age-old hierarchies of the colonial system which divided humans into superior and inferior species. Migrant voice is largely missing from the coverage. History, that could explain the causes of ‘migration’, the distant conflicts and Britain’s role in them, is also nowhere to be found. The paper considers the exclusion of history and migrant voices from stories told to the British audience and reflects on their domestic and international implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For most of its history, Britain has been a migrant country. British communities have never been static, with people moving in, out, and about. While much of the population movement has over the years generated little comment (Bhambra, 2016), at other times, it has become a topic of heated debates. In the newspapers, debates have centred around the wisdom and utility of high rates of emigration from Britain, to fear and hostility to increasing immigration into Britain from Ireland, Eastern Europe, Africa, the Caribbean, and the Middle East (Dorling and Tomlinson, 2019). Through editorials and news generated during periods of intense debate over the costs and benefits of population influx and anxiety over ‘undesirable’ immigration, newspapers have provided an important platform for a national conversation on various aspects of British migration, inclusion and exclusion from national citizenship and belonging.

This paper contributes to our understanding of public debates over migration by examining dynamics within press coverage of arrivals of migrants and refugees in the UK between 2015 and 2018. These 4 years form the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ and the UK’s debate on its relationship with the European Union (EU) and the free movement of people that it entailed. This paper uses a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods to analyse a sample of 400 articles from two national quality newspapers, The Guardian and The Times, and compares coverage across the political spectrum. The study historicizes these media representations and reveals that the discourse they employ advances the racialised mix of knowledge and historical amnesia. Representations of mobility by Britain’s left-wing and centre-right newspapers reproduce visions of ‘invasion’ that, although in different ways, produce an image of a ‘threat’ to the British nation. They create abject subjectivities and divide humans into active and capable on the one side and those linked to crime, danger, inability, resource drain and exploitation, on the other. This construction of a bifurcated world gives rise to racist organizations of society within which media’s contemporary practices continue to racialise non-Western populations. They actively reproduce their subordinate place in a hierarchical relationship with Britain. Consequently, the newspapers reproduce age-old hierarchies of the colonial system, which divided humans into superior and inferior species. Migrant voice is largely missing from the coverage. So is history that could explain the causes of ‘migration’, the distant conflicts within which Britain played a role. This paper considers the exclusion of history and migrant voices from media representations presented to the British public and reflects on the domestic and international implications of such portrayals (Fig. 1).

Europe’s ‘migrants’ in the British and European media

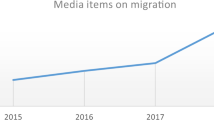

The so-called ‘refugee crisis’ in 2015 and the UK-EU referendum in the United Kingdom held in 2016, placed the topic of migration high on political agendas in Britain (Hobolt, 2016). European media research on immigration revealed that, from 2017 to 2018, the ‘European refugee crisis’ was the dominant focus in the field (Eberl et al., 2018). Recent scholarship has confirmed that migration within Europe and from third countries to Europe and the UK has received the bulk of media attention in Britain (Allen, 2016; Balch and Balabanova, 2016; Berry et al., 2016).

Most research focused on the salience of immigration in media reporting and conceptualized it as the volume (Akkerman, 2011; Lawlor, 2015), or intensity (Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart, 2007, 2009). These primarily quantitative studies measured salience based on the absolute number, or relative share, of news stories discussing immigration or the presence of various migrant groups. They focused mainly on national media systems, including print media outlets (Vliegenthart et al., 2011), and television broadcasting (Igartua et al., 2014).

The agenda-setting role of the media has also been examined. Studies have investigated the relationship between the visibility of immigration-related news and political discourse, looking at how political and media agendas shape one another (Vliegenthart and Roggeband, 2007). In the UK, news coverage of immigration increased after the election of the Conservative-led coalition government in 2010 (Allen, 2016). External events, such as the 9/11 attacks and their influence on the intensity of immigration coverage, have similarly been analysed (Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart, 2009; Kroon et al., 2016). The primary takeaway from these studies is that journalists tend to focus on single, standalone events rather than on broader trends.

Media framing has been another area of scholarly interest in news coverage of mobility. Two main approaches have been used: generic framing and issue-specific framing. Generic framing has explored the victimization of ‘migrants’ and ‘refugees,’ conflicts, and how the media outstrip thematic coverage and relate to journalistic practice (Brüggemann and D’Angelo, 2018). Research on issue-specific frames has focused on economic, cultural, and security matters, capturing the negative portrayal of migrants as a supposed ‘threat’ to the economy, culture, and security of host countries (Balch and Balabanowa, 2016; Breen et al., 2006; Meeusen and Jacobs, 2017), or focusing on both negative and positive framing of migration (de Vreese et al., 2011; Schuck and De Vreese, 2006). Baker et al. (2008) found that the term ‘migrants’ is closely associated with the frame economic threat, the threat of increased competition in the labour market, while the terms ‘refugees’ and ‘asylum seekers’ are linked to an economic burden, for example, on the welfare system. Tabloids have been found to cover immigration more negatively than broadsheets (Cheregi, 2015; Kroon et al., 2016). Quality newspapers employ the vocabulary of ‘refugees,’ while tabloids rely on the terminology of ‘migrants’ or ‘immigrants’ (Berry et al., 2016; Vollmer and Karakayali, 2018) and openly biased terms such as ‘illegal’ or ‘bogus refugees’ (Gabrielatos and Baker, 2008), discursive tactics that delegitimize refugees’ dire political and personal circumstances (Eberl et al., 2018, p. 210).

Ethnic backgrounds of migrants have been also explored by research. Exposure of Muslim immigrants in the media has been more prominent than coverage of other religious groups (Bleich et al., 2015). North Africans, primarily Muslim, are framed as a cultural threat (Meeusen and Jacobs, 2017) and a security threat, frequently linked to terrorism (Chouliaraki et al., 2017; van der Linden and Jacobs, 2017). By contrast, Eastern Europeans are associated with economic burden and economic threats (Balch and Balabanova, 2016). The diversity of actors was the highest in elite newspapers (Masini et al., 2018). Such distinctions applied to ethnic or religious groups in the British newspapers also vary across media genres (Blinder and Allen, 2016).

Studies have also linked the visibility of immigration in the news to the formation of public opinion (Aalberg et al., 2012; Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart, 2009; Schemer et al., 2012). By emphasizing and making visible immigrants’ ethnicity, news media can increase citizens’ hostility towards migrants in host countries (Sniderman et al., 2004; Van Klingeren et al., 2015). Changes in behaviour, such as an increase in extreme-right violence, have also been linked to high media coverage of immigration (Koopmans, 1996). Research has also found evidence for the rise in Euroscepticism amongst viewers due to their exposure to media reporting of the recent ‘refugee crisis’ (Harteveld et al., 2018). Such media reporting has concrete political implications: the more media reports focus on quantitative matters, e.g., the numbers of arriving ‘migrants’, the more likely citizens are to vote for anti-immigration parties (Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart, 2007; Burscher et al., 2015).

In sum, scholarship attending to media coverage of migrants and migrations to Britain and Europe has explored visibility, agenda-setting, actor/group salience, framing, and opinion formation. However, scholars have not paid adequate attention to the role that race plays in media narratives of mobility. This study intends to fill in this gap by exploring connections between contemporary representations of non-Western people and the historical creation of ‘race.’ It studies the role of discourse in the creation and perpetuation of racism.

Race, migration, and the media

Racism, deeply imbricated in imperial and colonial discourses, is understood as institutional, discursive, and legal discrimination based on race, ethnicity, and skin colour, to ensure and justify the domination of Europeans over people of colour (Miles, 1989; West, 2002; Young, 2001). Supported by imperial science, racism was historically understood as a belief that ‘the white race was superior to non-white races’ (Stepan cited in Wheeler, 2001, p. 33). In the 19th century, British public opinion simply regarded the Empire’s black and brown subjects as natural inferiors (Lloyd, 1984). Today, racism is a ‘system, a mode of domination and a form of power’ that persists despite scientific developments ‘proving racial categories to be meaningless and racial hierarchies to be fabrications’ (Mayblin and Turner, 2020, p. 49). It is also a system of beliefs and knowledge production about colour and whiteness, superiority and inferiority, physical and cultural characteristics, and social meanings they carry (Cooper and Stoler, 1997), that has been ‘institutionalized even as British colonies gained independence’ (Bassil, 2011, p. 378). Racism is also a system of ‘moral hierarchies’ that always positions whiteness at the top and blackness at the bottom of the hierarchy, and is ‘irrespective of socio-historical context, criteria, or purposes of comparison’ (Böröcz, 2021, p. 19). Imperial Britain supplemented the initial connection between race and skin colour with other factors, such as religion, class, and culture, that were used to ‘prove’ the inferiority and sub-human status of foreign people, and which shaped British perceptions of the world long after the fall of empire.

The media have historically participated in racial profiling foreign populations and actively constructed Britain’s ‘Other’. For instance, in 1893, Truth magazine described immigrants and foreigners as ‘deceitful, effeminate, irreligious, immoral, unclean and unwholesome. Any one Englishman is a match for any seven of them’ (cited in Dorling and Tomlinson, 2019). Racist ideas that ‘treat an entire category of people as a menace’ (Cooper, 2014, p. 78) were constructed through discourse that produced the colonized as inferior for the purpose of domination (Fanon, 1961). It was through the English language that these beliefs shaped political and popular discourses beyond Britain and influenced modern conceptualizations of the world (Saïd, 1993; Saïd and Barsamian, 2003). Race and racism, however, are largely ignored in the study of mobility (Rajaram, 2018) due to the habit of ‘forgetting’ race across social science research (Mayblin and Turner, 2020, p. 50).

This habit of ‘forgetting’ also dominates research on media representations of contemporary migrations. The field has overlooked the historical connection between colonial racism and contemporary media discourses on mobility. Significant exemptions include a study of the media’s role in orientalising Muslims and Islam. Abbas (2019) observed that conflating the ‘Muslim refugee’ and the ‘terror suspect’ in Brexit Britain was the common response of media to the Syrian refugee ‘crisis’ in the aftermath of the 2015 and 2016 Paris terror attacks. This portrayal relied on racial tropes of violence historically ascribed to Muslims. Likewise, in earlier media coverage following 9/11, western news coverage ‘portrayed Muslims as uncivilized, anti-modern, anti-democratic, and terrorists, fundamentalists, radicals, militants, barbaric, and anti-Western’, effectively turning Muslims and Arabs into a negative ‘Other’ (Nurullah, 2010, p. 1022). Other studies observed that portrayals of EU citizens in the media foster negative stereotypes (Walter, 2019), further dividing British and EU citizens during the 2016 UK–EU referendum.

Strong nationalist tones of the Brexit campaign, negative media coverage of EU citizens that emphasized a divide between ‘us’ vs. ‘them,’ and the subsequent image of EU citizens as an out-group has not, however, been explored in terms of racial divisions, nor has it been connected to Britain’s colonial past. This paper tries to ‘remember’ the histories of racial divisions, of the creation of race and racism. It historicizes media representations of racial ordering in modern Britain and media’s silencing of migration’s diverse causes. It traces a line from colonial to post-colonial, to contemporary discourses of mobility in processes of categorization. It interrogates media coverage of ‘migrants’ and ‘refugees’ to tease out how old racist ideas continue to structure contemporary discourses of, and responses to, the mobility of certain people.

On the method

This paper examines media representations of population movements between 2015 and 2018 when migration was high on political and popular agendas. This period saw Britain and many other European countries facing the issue of integration of the unprecedented number of arrivals during the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ and its aftermath—both socially and economically. In Britain, coverage also focused on the Brexit campaign, fueled in part by the issue of large-scale immigration (Burrell et al., 2019; Dennison and Geddes, 2018) and resulted in a protracted debate on the impact of European migrants on the British economy, and the uncertainty surrounding their status in the UK after the country’s exit from the EU.

The quantitative and outsourced part of the study provides a big picture of British media coverage of migration. It includes mapping of monthly mentions of the keywords ‘migrant(s)’, ‘refugee(s)’, and ‘asylum seeker(s), through the search that delivered 86,537 stories across a wide selection of media outlets.Footnote 1

From this large sample, two newspapers have been selected: The Times and The Guardian, to examine representations of ‘migrants’ and ‘refugees,’ and to explore how the response to mobility in general, and ‘refugee crisis’ in particular, was mediated. The paper focuses on how these two quality newspapers make sense of human mobility, the types of migrations they choose to cover, the narratives they employ to discuss ‘migrants,’ the issues they connect to people on the move, actors and voices that speak (or are silenced) in debates on migration, and the representation of ‘migrants’/’refugees’ agency, rights, and needs. The rationale behind the selection of quality newspapers is that they represent a less obvious case than tabloids. The tabloid press has been eager to employ explicit assumptions about ‘migrants’ and ‘refugees.’ However, the analysis of broadsheet newspapers is likely to reveal more subtle and hidden assumptions that may elucidate the effects of problematic power/knowledge formations. Additionally, selecting The Guardian (with more left-leaning views) and The Times (with centre-right editorial policies) allows to uncover patterns along differing political orientations.

One hundred stories were selected, 50 from each newspaper, from the period between 2015 and 2018.Footnote 2 The study focused on the peak coverage period when the highest number of stories were published each year. The choice of clustered sampling helped identify the types of ‘migration,’ their context(s), underlying causes and consequences, that were considered by both newspapers to be the most newsworthy across the four years of study. In 2015, the peak occurred in September, when the body of Alan Kurdi, a 3-year-old Syrian boy of Kurdish background, washed up on a beach in Turkey. The peak dropped by half at the time of terrorist attacks in Paris in November. Coverage in 2016 spiked in February and was dominated by reporting on the so-called ‘Jungle’, a refugee camp in Calais, France, that was to be demolished. It was also related to the announcement of the referendum on UK membership in the EU by the British government and David Cameron’s subsequent participation in EU meetings on immigration during the pre-Brexit vote period. In 2017, coverage peaked in the first 2 months of the year and focused on harsh winter and living conditions for refugees in Southern Europe, and on stricter measures for asylum seekers announced across Europe. In 2018, the highest coverage peak occurred in June, when the charity ship Aquarius carrying 629 Sudanese and Bangladeshi migrants saved from drowning in the Mediterranean Sea was denied entry into Italy and Malta, before finally being accepted by Spain. Stories were codified with particular interest paid to the frames through which newspapers imagined the ‘migrants,’ voices/actors speaking in the stories, and proposed solutions to the ‘crisis.’

The stories gathered during the peak coverage have been subjected to critical discourse analysis (CDA). CDA is a valuable tool for exploring the discursive production of ‘migrants’ and ‘refugees’ and to explain discourse productivity of media, particularly in representations of ‘migration.’ Scholars of discourse agree that language is constructive and that through discourse, reality, knowledge, and subjectivity are brought into existence (Foucault, 1980; Hall, 2002; Potter and Wetherell, 1987). Discourse is historically and culturally specific: it is a way of (re)presenting a particular topic at a particular historical moment and links knowledge and social processes (social action) (Hall, 1997, p. 44). Discourse is manufactured from pre-existing linguistic resources, systems of terms, narrative forms, metaphors, that construct the world (Potter et al., 1990, p. 207). Discursively produced reality differs depending on the choices of language made by particular communities. In its aim to uncover discursive meaning(s), discourse analysis seeks to ‘investigate how…texts arise out of and are ideologically shaped by relations of power and struggles over power’ (Fairclough, 1993, p. 135).

Therefore, this article subjects the selected newspaper stories to textual and inter-textual analysis (Fairclough, 1995). Textual analysis of the 400 articles explores the linguistic features of the text, looking for trends and patterns in choices of words (nouns, verbs, adjectives, labels). Words are never neutral descriptors but instead produce specific meanings. The texts are also scrutinized in search of evidence of inter-discursive and inter-textual analysis to examine how authors of the articles draw on pre-existing discourses to create their texts. The search for past discourses is what Foucault (1996) calls genealogy, or the ‘history of the present,’ that unearths political practices that have formed the present and uncover alternative understandings that mainstream discourses have left out. Hence, the paper scrutinizes the newspaper stories for their use of past discourses that ‘echo’ directly or indirectly in today’s media reporting and which are being used to construct the present. Finally, the contextual analysis puts the newspaper articles into structural and socio-cultural contexts to explore the societal dimension of texts (e.g., imagined communities) to examine which forms of representation, knowledge, or identity the selected texts make dominant.

The paper borrows from Derrida’s (1981) concept of deconstruction, which argues that language is made up of dichotomies, that are not neutral since one of them is superior to the other (e.g., modern/traditional, civilized/barbaric). Deconstruction allows for uncovering relationships in which people and things are placed in a discourse where one object is distinguished from, or privileged, over another. It exposes hierarchies in those relationships and ultimately uncovers the relation of power (Derrida, 1981). The study of discourse is an enquiry into the knowledge-power nexus (Campbell, 1993; Foucault, 1980, 1991). According to Foucault, ‘power and knowledge directly imply one another…there is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time power relations’ (1977, p. 27). The power of discourse lies in its ability to establish forms of action that are made possible in each social context, to impose specific representations of the world as legitimate and authoritative (e.g., create the meaning of ‘migration’ or ‘crisis’); and to construct social identities—both individual and collective—and establish relationships between them. Discourse is also action-oriented: it implies action, it does things with the linguistic tools it uses (e.g., discourse might blame, apologize, validate, rationalize, or justify). Hence, the paper questions discursive and social practices that discourse enables and the ideological consequences it carries.

What’s in a word: ‘migrants,’ ‘refugees,’ and the ‘crisis’ in the British media

The ‘crisis’ that turned refugees into ‘migrants’

‘Crisis’ has emerged as a central theme in reporting on ‘migration’ by the British media between 2015–2018. The arrival of refugees to southern Europe, mainly Italy and Greece, and their journey across the continent to potentially reach the UK, was labelled by both newspapers as the biggest ‘migration crisis,’ ‘refugee crisis,’ and ‘humanitarian crisis’ since the second World War. Although the European Commission officially declared that this ‘crisis’ ended in March 2019, media outlets continued to apply the term after that period, effectively turning it into a calamity without beginning or end.

Multiple studies have questioned the media’s ‘crisis’ frame as a selective tool used to project certain visions of ‘reality’ and silence others (De Genova, 2016; Chouliaraki et al., 2017; Forkert et al., 2020). Crisis narratives give an impression of immediacy and urgency while stripping the developments of their broader historical and political contexts. The autonomous movement of non-European people has revealed a border crisis (De Genova, 2016) and a racial crisis (De Genova, 2018), while exposing the border regime as based on differential mobility rights granted to different populations (Oliveri, 2017). This, in turn, may be seen as a broader ‘crisis of state sovereignty that is repeatedly instigated…by diverse manifestations of the autonomous subjectivity of human mobility itself’ (De Genova, 2016). The ‘crisis’ narrative opens up space for ‘crisis governance,’ including exceptional measures, the use of force, and derisions of established practices and the rule of law (Forkert et al., 2020). The crisis narrative allows for reconfiguration of strategies and mobilization of stricter law enforcement measures; it permits waning states to re-gain their weakening sovereignty. It provides opportunities to be seen in control.

‘Migrants’ is another overarching term used by the two news outlets to denote a wide variety of people. Europeans living in the UK, ‘refugees’ fleeing from conflict-ridden countries, and people crossing the Mediterranean or the English Channel are described as ‘migrants.’ The papers identify migrants mostly in numeric terms. Numbers, not names, professions, or other human qualities, dominate the coverage. The newspapers describe migrants as ‘numerous’; they arrive in ‘high numbers.’ References to the scale of arrivals are explained through metaphors. Both newspapers are equally inventive, frequently applying images of natural disasters: the words ‘flow,’ ‘wave,’ ‘surge,’ ‘catastrophe,’ and ‘disaster’ are used to portray people’s movements.

Differences between the two newspapers do not always align with their political orientation. The Guardian calls the arrivals primarily ‘refugees’ and ‘asylum seekers’ who deserve human rights, but surprisingly—given its overall humanitarian and strong pro-migration stance—the newspaper also relies on more pejorative terms including ‘economic,’ ‘political,’ and ‘irregular’ migrants. The Times sees the arrivals as a ‘mass exodus,’ ‘flood’ and ‘invasion’ and uses even fewer words denoting names and nationalities than The Guardian. ‘Migrants’ in The Times are overwhelmingly referred to as ‘economic,’ ‘political,’ ‘undocumented,’ ‘illegal,’ or ‘displaced’ people. Women ‘migrants’ are almost non-existent in both newspapers’ coverage.

Thus, both newspapers engage in a re-definition of the term ‘refugee.’ The Geneva Convention of 1951 defines refugees as people fleeing wars and persecutions. They are to be offered legal and material protections, a human right afforded to them by international law. By re-classifying refugees as ‘migrants,’ both newspapers suggest that personal choice and circumstances are the basis for mobility (rather than war and persecution, two aspects clearly out of refugees’ control). As such, the newspapers effectively delegitimize refugees’ claims to protection. This tactic, commonly used by the tabloid press (Berry et al., 2016; Gabrielatos and Baker, 2008; Vollmer and Karakayali, 2018), is widely employed by The Guardian and The Times, although there is reason to believe that The Guardian is simply confused in its mixed messaging. Six years after the ‘crisis,’ the newspaper wholeheartedly defended the ‘human rights’ of refugees, yet painting them as ‘migrants who are in peril,’ and placing a story on the ‘Return of migrant vessels’ in a section on ‘migration’ (2021). The Times largely dismisses the concept of ‘refugees’ and demands ‘emergency breaks’ on their entry into Britain. The newspaper advocates ‘outsourcing’ ‘migrants’ to other regions as a solution to the ‘crisis.’ Through these discursive choices, refugees-turned-migrants are stripped of their legal status, which would typically impose responsibility on receiving states. Instead, states can discharge their accountability for deaths and suffering at the border. Citizens of the host countries and readers of the two newspapers producing this discursive shift are encouraged to think of ‘illegal migrants’ as unworthy of protection.

Desperate victims of distant circumstances

The Guardian emphasizes ‘struggle’ and ‘desperation’ in its portrayal of ‘migrants’ and refugees, though often from a personal angle. The newspaper paints people on the move through the lenses of ‘fear,’ ‘sorrow,’ and ‘pain’ general vulnerability, and victimization: ‘migrants’ are ‘abused,’ ‘vulnerable,’ ‘suffering,’ and ‘victims.’ The Times also frequently implies helplessness and powerlessness by describing people as ‘vulnerable’ and ‘victims.’ Migrants and refugees are also associated with deliberate mischief, and to a lesser degree with fear and desperation. Both newspapers see ‘camps’ as migrants’ natural habitat, a place where ‘desperation,’ ‘daily strife,’ and frequent ‘violence’ occur. Middle Eastern and ‘African’ migrants are never portrayed as integrating with the citizens of host countries, contributing to their new local communities, or socializing into local practices. Although perhaps attempting to imply empathy, the characteristics used to describe migrants as desperate, vulnerable, abused victims are essentially negative. They evoke misery, despair, and hopelessness as the main and natural state of ‘migrants.’ Furthermore, stories of individual suffering direct readers’ attention away from the conditions that made their suffering possible. All descriptors imply passivity by presenting them as people who need to be taken care of, or people who are intrinsically prone to violence—these discursive strategies strip refugees of agency, and ultimately, humanity.

The primary origin of people’s movement is identified by both newspapers as Syria, followed by Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, Yemen, and Libya, and unspecified locations in the Middle East, Africa, and North Africa—all majority Muslim regions. Major destinations of the ‘flow,’ as characterized by both newspapers, include Europe, Germany, and Britain, and excludes some of the largest movements within the Middle East, or Africa, that are not Europe-bound.

The two news outlets do not usually ascertain the causes behind migration. Migration seems to happen for no apparent reason, according to a large proportion of coverage by both newspapers (60–80% across 4 years). Between one quarter and one-third of articles in The Guardian point towards unnamed ‘wars’ and ‘conflicts’ as push factors behind the ‘mass displacement.’ A tiny minority mention the ‘war in Syria,’ ‘repressive governments,’ and ‘poverty,’ with a few stories identifying ‘ISIS’ or ‘terrorism’ as factors that push populations out of their homelands. Factors attracting migrants to Europe and the UK include benefits, social welfare, education, job opportunities, and security. The Times rarely identifies push factors. On occasion, ‘war’—sporadically referred to as ‘Syrian war’—brings ‘migrants’ to Europe. Mostly, The Times mentions unidentified conflicts in the Middle East and Africa as the reasons behind migration. Other, less frequently mentioned push factors include poverty and ‘economic instability,’ ‘rape’ and ‘massacre.’ The Times makes it very clear that the social welfare system in the UK is what attracts ‘migrants’ to Britain. In 2016 alone—the same year as the UK–EU referendum—UK social welfare benefits were listed in 86% of all articles in the sample explaining why migrants moved to Britain.

The voiceless and powerless

Most news coverage paints ‘migrants’ or ‘refugees’ as silent. They do not speak for themselves. The news stories exclude them from conversations about their lives and experiences, are not regarded as fully human with voice, capacity, or agency. They are seen as passive recipients of international aid, subjected to the will of others, never quite capable of providing for themselves.

While The Guardian puts more emphasis on individual stories than the macro-level coverage in The Times, the paper overwhelmingly focuses on refugees’ ‘desperation’ and ‘suffering.’ Their coverage revolves around trauma and vulnerability, a tactic that ignores refugees’ ability to come up with solutions. Passive ‘migrants’ are understood as dependent on host countries’ benevolence; the news stories do not depict them as able, capable, competent, skilful, bright, or gifted. By contrast, the stories portray Western Europeans are as movers and shakers. By far the most frequent actors in The Guardian are national governments. European governments are equipped with agency, decisions, and will, although their responses vary on the moral scale: ‘Angela Merkel said Germany expected to take at least 800,000 asylum seekers’ with the figure likely to ‘hit 1 million.’ Britain is described as ‘refusing to take part in a new quota system proposed by Berlin’ and ‘Hungary uses teargas and water cannon at Serbia border.’ EU institutions and officials are also frequent actors cited in The Guardian, alongside charities and activists. ‘Thousands of Germans’ are praised for volunteering ‘to help refugees.’

Similarly, a state-centric approach dominates The Times coverage. The most frequent actors in stories on migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees are national governments. The British Treasurer was reported working on a ‘new additional budget allocated to aid refugees,’ Angela Merkel’s ‘over-generous’ approach was criticized, and the French President ‘has committed France to accepting 24,000 over two years.’ These national actors are closely followed by international and EU institutions, artists, activists, and citizens. For The Times, any agency or ability afforded to ‘refugees’ or ‘migrants’ is seen only in cases of crime, risk, and menace.

Both newspapers position British and international politicians, institutions, and charities in a dichotomous relationship with migrants. The British are depicted as pro-active, competent, and capable of formulating approaches to the ‘crisis,’ confident in managing the ‘unprecedented’ population movement. The newspapers paint them as protectors of borders, welfare, and the British (and European) way of life. As the binary opposition constructed by the newspapers’ discursive strategies, ‘refugees’ and ‘migrants’ emerge as voiceless, passive, and powerless. The paper will return to the construction of these dichotomies in the later section on colonial hierarchies.

Manufacturing Britain’s ‘enemies’

Security threat

Security threats are a recurring framework through which The Guardian and The Times construct incoming ‘migrants.’ The Times creates ‘migrants,’ especially those from the Middle East and Africa, as a threat to law and order. Mobilizing language of invasion, The Times uses metaphors such as ‘mass exodus,’ ‘desperate exodus,’‘potential stampede,’ ‘mob,’ and ‘aggression.’ ‘Migrants’ are frequently portrayed as people who bring violence over to their host countries, as if violence did not already exist in the host countries. The newspaper reports on ‘rioting migrants’ and ‘huge crowds of refugees’ who ‘battled with the outmanned and ill-equipped local police forces’ on their way to Europe. ‘Furious scenes’ were reported to have occurred at the Hungarian and Serbian borders, as ‘migrants turned on each other.’ Christians expressed anxiety towards Muslims, as fear and hostility amongst different cultural and religious groups reign in refugee camps: ‘the Afghans cause problems, always… they are trying to take advantage of our problems to get to Europe.’ Syrian mothers feared for the safety of their teenage daughters; as ‘Pakistanis… are trying to kill us.’ The Times coverage criminalized border crossings, for instance, the ‘Jihadist hunt’ for a ‘suspected jihadist’ was reported in the ‘new jungle;’ the Calais refugee camp was portrayed as a dangerous ‘no-go area for police’; a man was described as potentially dangerous, wanted by the French Intelligence ‘for the safety of the State,’ and was ‘thought to be planning terror attacks in the UK.’ The Times discussed NATO warships as a solution to ‘stem the flow of refugees coming into Europe.’ In another story, the paper reported ‘growing violence and crime’ amongst migrants in Germany. Taken together, these stories from The Times narrate a dangerous security threat encroaching from all sides of the supposed ‘crisis.’

Surprisingly, despite its primarily humanitarian stance, The Guardian delivered a similar message as The Times while covering various types of migrations, including those to the UK, US, and Australia. The Guardian frequently chooses to focus on illegal activities, such as their legal battles, previous convictions and offences, their support for ‘terrorist group with links to Osama bin Laden’, or smuggling of refugees across the English Channel, which despite being described as the ‘crime of compassion’, still situate refugees in the realm of wrongdoing and law-breaking. ‘Future suicide bomber,’ ‘an invasion under way,’ refugee babies seen as ‘illegal maritime arrivals,’ ‘African exodus,’ and resettlement programmes that work as ‘cover for terrorists’ are a snapshot of the metaphors used by the newspaper that frequently link ‘migrants’ to a security threat. This use of language sends a mixed message. On the one hand, the newspaper defends the refugees’ plight and sympathizes with their dilemmas. Yet, on the other hand, the stories selected for publication recurrently place ‘migrants’ in the context of crime and associate them with illicit activity or terrorism.

Therefore, the two newspapers converge to a large degree on the image of Arab, Muslim, and North African ‘migrants,’ with The Times openly describing them as a threat to law and order, and with The Guardian frequently choosing to publish stories that, although protect ‘migrants’ and defend their rights, they simultaneously see them as thematically connected to the same domain of law and order. The identified ‘Muslim-ness’ connects people to criminality, terror, security threats, and illegality. These newspapers are engaged in a production of British ‘enemies,’ a project that redirects the focus away from human rights and instead towards national security in the treatment of asylum seekers. Abbass observed that the convergence of ‘Muslims’ and ‘threat’ mobilizes a racialized biopolitics (2019). It inserts security concerns that underpin counter-terrorism into asylum regimes based on human rights priorities. This discursive production of ‘threat’ generates the body of knowledge that promotes specific policy responses: the imagined extremism of migrants justifies border closures and withdrawing rights; their portrayal as violent and dangerous supports racialized biopolitics involved in practices of governance that exclude certain groups from nation-building, encourages racial profiling and surveillance practices, rationalizes spatial control, restrictions to freedom of speech and political engagement, and creation of internal divisions within the oppressed group.

This coverage also draws on the earlier construction of Muslims as ‘enemies’ of the West, produced by Western media in the post-9/11 era. During this period, stereotypes and fear of terrorists classified Arabs as a ‘different order of humanity’ (Razack, 2008, p. 7). Such representations legitimized sweeping changes in governmental practices, including curtailing civil liberties and increased support for racial profiling (Altheide, 2004). Individual violent incidents quickly became attributed to Islam, provoking a national backlash against refugees, and an upsurge in right-wing populism and Euroscepticism (Harteveld et al., 2018), which later framed both Brexit and anti-Muslim hostility more broadly. This trend did not affect other religions; scholarly debates and media coverage did not link, for example, Christianity or Judaism with terrorism. These practices, built on centuries of ‘othering’ Muslims and orientalising Islam (Saïd and Barsamian, 2003), are visible in contemporary media debates that discursively link Muslims, Arabs, and North Africans to violence, threat, and disorder, and therefore (re)produce the idea of Muslims as the ‘enemy of mankind,’ a dichotomy that separates humanity along biological, cultural, and religious dimensions. What is particularly striking here is the position of The Guardian, a newspaper which, for the most part, aligns itself with humanitarianism, egalitarianism, and internationalism, accepts buys into the idea of the ‘Muslim other.’ This indicates that the newspaper is drifting towards the right-wing narrative of ‘migrants’ and their manufactured association with ‘security threat.’

Economic threat

The economic impact of migration, particularly its financial cost to host countries and its ‘drain’ on domestic resources, are the most frequently discussed issues by the two newspapers. A large proportion of stories depicts ‘migrants’ as an ‘economic burden’ who affect housing, public services, and job opportunities for British and European citizens.

Eastern Europeans emerged as a group of ‘economic migrants,’ especially in coverage between 2016 and 2017, during the UK–EU referendum, national elections, and extended debates on the UK’s relationship with the EU. Although they exercise their right to free movement granted to all EU citizens by the EU Treaty, ‘Eastern Europeans’ are nevertheless seen as ‘migrants.’ Like Muslim migrants, they too are depicted via the metaphors of flood and invasion, especially in The Times. The most common nationalities reported on in the media included Poles, Bulgarians, and Romanians, who The Times reported on as nameless figures: ‘the number of working Romanians and Bulgarians rose by 30% to 202,000’ to reach ‘almost a million of the UK’s workforce.’

Unlike their western counterparts, who, as ‘EU citizens’ are associated with intellectual capacity and portrayed in positions of responsibility and highly paid jobs, Easterners are associated with low-end manual labour. Both newspapers construct them as ‘workers’ and ‘labourers’ and discursively associate them with ‘shelf-stocking’, ‘cleaning’, ‘fruit-picking’ and ‘farm work.’ They are portrayed as prone to benefit abuse and are imagined as a threat to the British welfare system. The Times depicts Eastern Europeans as architects of ‘child benefit payments going overseas’ and reports on ‘the British Prime Minister pursuing a ‘diplomatic offensive … to restrict benefit payments to EU migrants’ and demanding ‘emergency brakes’ on benefits ‘because the welfare system is under strain.’ Throughout 2016, 84% of stories in The Times made a clear connection between migration and social benefits-seeking.

This construction of Eastern Europeans as a dishonest and exploitative drain on national resources stands in stark contrast to their reception in post-World War Two Britain. The British government recruited close to 100,000 Eastern European refugee workers under a voluntary work scheme in the five years after the war (Maslen, 2011). The Polish Resettlement Act of 1947 invited another 128,000 exiled Polish armed forces and their dependents to settle in Britain (Kay and Miles, 1988). The aim of these programmes was to ‘assimilate’ Eastern European migrants and transform them into ‘worthy members of the British community’ (Salvatici, 2011). For instance, Latvian women belonged to a category of ‘sound stock’—a ‘good and desirable element’ whose marriage to British men was welcomed to ensure the maintenance of a healthy, white, British ‘line’ (Briefing Paper, 1948). Compared to the post-war discourse that racialized Easterners into whiteness, recent media constructions of them as ‘labour,’ ‘threat,’ and ‘welfare system abusers’ represent a discursive shift that separates them from whiteness. Eastern Europeans become detached from skill, knowledge, and worth—traits that belong to Westerners. The newspapers cluster Eastern Europeans with people who, as non-white former colonial subjects, have been historically depicted as dangerous, prone to criminality, and generally of no value to British society. This manoeuvre produces what Böröcz terms ‘dirty whiteness’ (2021), a new category in racial stratification.

Portraying some group identities as being naturally predisposed to physical labour, with the strength of muscles as their only attribute, prone to theft and system abuse (Eastern Europeans), or as dangerous and violent (Middle Easterners), creates a hierarchy of humans. Within this hierarchy British and Western Europeans living in the UK are seen respectable and worthy, all others are depicted by the media as a lower species, undeserving, and evil—perhaps not even fully human. The media actively created a world of divisions between the ‘good’ and the ‘bad,’ between superior and inferior human beings. Such hierarchical representations draw on racism and coloniality exercised in British colonies, which have come to govern the present.

Contemporary lives of imperial discourse: identity, relationships, and genealogy

The media narratives from this sample draw on colonial and post-colonial discourses of population control, racism, imperial self-identity. They also employ the strategy of historical containment. Taken together, these narratives create human hierarchies and produce knowledge rooted in imperial power.

Colonial, post-colonial, and present-day coloniality

Migrants emerge in media coverage as one of the most despised groups in society. They are discarded from national projects and pose a ‘threat’ to Britain’s security and national resources. Their association with danger is a work of representation performed by the British media. Yet, where does the notion of ‘threat’ come from? Why is it associated with foreign populations? This section historicizes the contemporary media discourse of ‘dangerous populations,’ a strategy that draws on the colonial discourses of the 19th century and their racism that is established itself firmly in the British political narrative after the formal colonial era had ended.

The narrative of ‘danger’ has come to dominate the current global mobility regime that, informed by the legacies of colonial systems, is organized around three security threats: immigration, crime, and terror (Shamir, 2005). ‘Danger’ refers to the global poor, to marginalized and undocumented of the darker colour who do not enjoy the same mobility rights as the 2.4 million migrants who, while arriving in Europe to study, work or live in the year of ‘crisis’ (Frontex, 2019), were not considered by the media as threatening. British newspapers actively build public consensus around the politics of exclusion based on neutralizing the ‘threat’ of informal mobility. The newspapers build on an earlier colonial separation of people into ‘compartments’ in which the settler zone was ruled by ‘good behaviour’ and ‘respect for the established order’ while the ‘native town’ was ‘starved of bread’ and ‘peopled by men of evil repute’ (Fanon, 1961, pp. 37–39). The racial order established by colonialism deprived racialised populations of access to resources, healthcare, safety, and opportunity, making them vulnerable to harm and premature death (El-Enany, 2020; Mamdani, 2018). This colonial system, although sustained by material means, was constructed by discourse. The power of the word helped create and sustain hierarchies and imperial identities. Media discourse that produces race and associates it with criminality, lends support to the containment of specific populations.

Racial divisions produced by discourse lived on in post-colonial Britain. When the Empire Windrush brought ‘coloured’ workers—former imperial subjects—to England, the government chose to ‘not make any special efforts to help these people’ (Winder, 2004, p. 338). Enoch Powell, a health minister who encouraged Caribbean workers to work in the British health service, quickly recognized that electoral success relied on anti-immigrant sentiments. In his 1968 ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, he confronted mass immigration. His vision of Britain and its ideal citizen as a ‘decent, ordinary fellow Englishman’ as under threat reinvigorated British racism. For Powell, letting in thousands of foreigners was like ‘watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre’ (1968). Even to the British left, the proposed exclusion of immigrants was an appealing strategy to ‘defend and revalorize the native worker’ (Bhattacharyya et al., 2020, p. 65). The British public knew little about decolonization, or its links to immigration and so remained antagonistic to the entry of non-white populations, who had been assumed as inferior (Dorling and Tomlinson, 2019, p. 206).

Similar sentiments continue today in British political discourse. Theresa May, the former Prime Minister, saw the ‘unprecedented mass movements of people’ as one of the ‘new threats’ (May, 2016). She saw danger in ‘chaotic arrivals’ through ‘unmanaged channels.’ Fifty years after Powell’s speech, while in charge of the Home Office, she created a hostile environment for migrants by sending billboard vans to drive around London with a message proclaiming ‘Go home or face arrest’ (Dorling and Tomlinson, 2019, p. 218). Under her watch, the children of the Windrush generation that had come to rebuild Britain after the Second World War were asked to produce documents that they had not previously been required to have. As a result, 140,000 people were told that they had no right to remain in Britain. British election campaigns today use images of non-white refugees to evoke danger to the established social order (The Guardian, 2016). Racial profiling informs counter-terrorism strategies (The Conversation, 2018) and minorities are charged with ‘pre-crime’ (The Cage 2016). The Brexit referendum applied racist sentiments of the 1960s, sustained in post-colonial Britain, to Eastern Europeans: they were told ‘to go home.’

The genealogy of discursive practices that aim to suppress foreign populations ‘begins in the colonies, intensifies with de-colonization and immigration in the second half of the century, and is formally institutionalized in Europe and North America after 9/11’ (Berda, 2013, p. 627). Contemporary media discourse on migration, in different ways, reinforces the colonial and post-colonial language of danger, criminality, threat, and violence used to describe former colonial subjects. As stated earlier, such discourse creates differentiation in human worth. Formulated within the baggage of colonial experience, it echoes the language of danger, aggression, and malice, and creates a dangerous ‘other’ that generates fear. It maintains coloniality, the cognitive mapping of the empire’s populations that produces a hierarchy of people, knowledge, and cultures (Quijano, 2000) and propels imperial structures into the present. Media discourse continues to provide justification to the containment of informal migration, ‘curbed flows,’ ‘outsourcing of migrants,’ outlawing the world’s poor and marginalized to travel, to the steady erosion of rights of asylum seekers to enter and settle in the global north, to the growing practice of incarceration and forcible return (Barnett, 2002).

Media coverage of ‘migrants’ from the examined sample reproduces racial superiority and xenophobia, that have lingered in political and popular speech since Empire. The discursive construction of the ‘enemy’ constitutes epistemic violence that assigns worth to people based on their external, cultural, and group characteristics: their nationality connotes trades like ‘plumbing’ or ‘cleaning,’; their religion implies a ‘threat’; the ‘darkness’ of the ‘African exodus’ brings ‘violence’ home. Specific groups are deprived of human characteristics: intellect, talent, ability, meaning, substance, quality, and value. The established connection between ‘North Africans’ and ‘Muslims’ with ‘terror,’ or between Eastern Europeans and the abuse of welfare system, creates cultural difference and adds a cultural component to the imperial-era’s biological register of racism (Mayblin and Turner 2020, p. 63). These two registers of racism (biology and culture), although analytically separate, exist together and are present in any racist discourse at the same time (Hall, 1993). Their interdependence gives ‘race’ meaning in the social world in the form of both racism and identity formation.

Imperial self-identity

Britain is portrayed by its national mainstream media as the main recipient of migrants and the primary sponsor footing the bill. Hardly any newspaper articles from the sample discuss regional displacement wherein refugees move into countries in the neighbourhood of conflicts, where most people find refuge. Both newspapers focus on the Global North—Europe, Germany, and Britain—as the main destinations of mass migration. Such self-centred representation reinforces the vision of Britain and Europe that find themselves under attack by dehumanized masses, illegally and undeservedly invading their territory and claiming rights to European wealth. This image of Europe as ‘under siege’ (Forkert et al., 2020) leads to discourses of ‘protection,’ and justifies policies of closed borders and increased security. It does not allow for solidarity with the ‘enemies,’ as they might bring violence to the carefully constructed zone of stability, and hard-earned prosperity.

Tellingly, the term ‘migrants’ does not apply to British people travelling in the opposite direction. The British media have reduced the meaning of ‘migration’ to a one-way movement of people: from the outside in. Stories covering the approximately 5.5 million British nationals living permanently overseas (equivalent to 9.2% of the UK’s population), were not found in the media coverage explored in this study. Britons do not ‘migrate’ even when experts characterized the dramatic outflow of Brits to Europe after the UK–EU referendum (WZB, 2020) as and abandonment of a country ‘hit by a major economic or political crisis’ (cited in The Guardian, 2020). To find British people living abroad, a separate search was performed with the keyword ‘expat.’ It found that British citizens ‘settle,’ or ‘live’ in other countries, while non-British nationals ‘migrate’ to the UK.

Moreover, British citizens living abroad are excluded from debates on ‘migration.’ They are shielded from negative connotations that the term ‘migration’ has acquired. They are not connected to housing shortages or rising prices. Retired British citizens in Southern Europe are not seen as exerting pressure on public services, cost or accessibility of health care, and the drain caused on national resources of host countries. While the news depicts ‘migrants’ in Britain as a threat to the country’s security, economy, and social cohesion, British ‘expats’ are not discursively linked to any of these migration-associated anxieties. The vision of Britons who historically never saw themselves as ‘immigrants’ is reproduced today by the country’s mainstream media. The troped identities of buccaneers, explorers, and entrepreneurs—historically assumed by the British to colonize and exploit the world— (Kemp and Lloyd 1960; Williams, 2005), are not afforded to the ‘illegal’ arrivals in Britain. As such, ‘migration’ is produced by both newspapers as a one-way street cobbled with trouble and disorder.

While discursively producing the ‘other’s’ identity, the newspaper authors generate their own identities in a ‘mutually constitutive process’ (Weldes et al., 1999). The different visions of the Self and the Other thus juxtapose each other in media reporting. Coverage describes individuals from Britain and Europe (Self) as agents of change, while the subaltern (non-Western Other) perspective is unimaginable. These binary oppositions juxtapose categories of the wealthy, orderly, benevolent, and developed Britain, vis a vis the poor, underdeveloped, and dangerous ‘others,’ who are dependent on Britain’s goodwill. These binaries are not merely economic or cultural but are racial divisions borrowed from the colonial lexicon. Such binaries dynamically racialise people from the former colonies through political, social, and cultural discourses and practices (Gilroy, 1987). The media reporting shapes Britain as a normative ideal of orderly governance, peace, and security presented as a ‘standard civilization’—a distinctive achievement of the West, Britain in this case—captured by the liberal theory of world order (Hobson, 2013). Populations placed on ‘the other side’ are deemed by this narrative as ‘uncivilized,’ a ‘backward ghetto that endures only regressive and barbaric institutions… condemned to an impoverished and stagnant existence’ (Hobson, 2013, pp. 32–33), a place where ‘anarchy, fear, violence and insecurity’ are thought to be commonplace (Pasha, 2013, p. 145).

British media actively create and re-create the vision of a bifurcated world. Their politics of pity (The Guardian) and politics of threat (The Times) create an image of dependent, or dangerous ‘others’ that portrays Britain as the sole carrier of this ‘burden.’ Kipling’s ‘White Man’s burden’ (1899) and his view of foreign populations as ‘half devil and half child’ are quietly present in contemporary media discourses of ‘migrants’ and ‘migration.’ This subject/object relationship in media stories is what Derrida calls a dichotomy created by language (1981). The dichotomy is not neutral because one representation is superior to the other. The act of simultaneously constructing the altruist and orderly ‘Self’ and the hopeless and anarchic ‘Other’, is based on the desire to define and dominate. This dichotomous relationship introduces a hierarchy and relation of power between superiority and inferiority, between higher and lower beings (Mehta, 1999, p. 20). It is a form of ‘imperial science’ that creates knowledge from the perspective of the West. It places the West in the position of ‘knowing’ to define ‘the other’ and provide solutions based on that knowledge. Put simply, media narratives re-create older colonial dynamics and identities in a contemporary setting, producing the ‘superior’ West vis a vis the ‘inferior’ rest.

Strategy of historical containment

If journalists claim to witness ‘history in the making’ (Lavoinne and Motlow, 1994), the British press certainly fails at the task. The newspapers do not endeavour to bring history to the reader’s attention or explain the causes of migrations. Although the two newspapers provide unidentified wars and conflicts as factors behind mass migration, these wars merely ‘happen’ to the Middle East; in other words, the wars themselves are never presented as having underlying causes. The role of European states, especially Britain, in these conflicts is not acknowledged. British involvement in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya, places where most ‘migrants’ come from, has come to be understood as ‘total failures’, in which ‘the bulk of responsibility must be laid at the door of [our] politicians who have little idea of conflicts and their consequences and no experience thereof’ (Ledwidge, 2017, p. xxii). Additionally, media coverage of population movement has silenced a range of British violence, including Britain’s colonial projects and the large scale global theft of land and resources and subsequent neo-colonization through multinational corporations, international institutions, and conventions, from which ‘Western perpetrators went away with their imperialistic loot’ (Johnson, 1988); recent ‘humanitarian interventions’ (Ahmed, 2003; Mamdani, 2010); and the transfer of risk to innocent civilians and their deaths, explained away as ‘accidental’ (Shaw, 2005), that have formed the migrants’ present. Britain’s imperial adventures in the Middle East (Stansfield, 2014; Van Genugten, 2016) are not classified by the media as implicated in mass migration. The contribution of colonial and post-colonial societies and resources, such as Malaysian rubber, Indian cotton, Kenyan tea, and others that jointly benefited British industries to the detriment of the post-colonial economies, are all left out from newspaper stories.

Likewise, the causes of Eastern European mass migration are not explained by either of the two newspapers. The post-war reorganization of Germany and Europe conducted at the Conference in Yalta in 1945, or in Moscow a year earlier, are never mentioned. Like similar conferences beforehand (e.g., in Berlin in 1884), Yalta and Moscow essentially put a map on the table and divided up the continent into ‘zones of influence’ to be governed by Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union (Leffler, 2012). A stroke of Churchill’s pen sealed the fate of a hundred million people—who were not consulted or represented in his one-to-one meeting with Stalin. Self-determination, promised by the conference to the liberated peoples of Western Europe, was not extended to Eastern Europeans. Eastern Europeans’ freedoms were the ‘price of peace’ paid to Europe (Haglund, 2012; Preston, 2020). Fast-forward several decades, the central planning of communism that ravaged economies pushed Eastern populations to the West in search of wealth and freedom, denied to them by Churchill and Stalin. Britain had a substantial stake in the division of Europe. Poles, Bulgarians, and Romanians sacrificed their futures for British peace, security, and stability. As in the case of post-colonial peoples and places, Easterners’ contribution to British wealth is not explained by media reporting migrants’ abuses of British welfare. Foucault’s genealogy, his ‘history of the present’ (1996), is non-existent in the two newspapers’ production of ‘migrants’ and the reasons behind their journeys.

Similarly, the domestic conditions that shaped the British economy are not explained in stories on ‘migration.’ Thatcher’s neoliberal agenda of deregulation, privatization and the subsequent selling-off of social housing (Davies, 2013; Farrall et al., 2016); Cameron’s ‘expansionary austerity’ measures that threw the knowledge of economic management of the previous 80 years ‘out the window’ (Krugman, 2012); the subsequent shrinking welfare of the British population (Butterworth and Burton, 2013; Hamnett, 2014; O’Hara, 2015); government underinvestment and declining industrial performance beginning in the 1960s (Kitson and Michie, 1996)—all of which contributed to the deteriorating standards of living, escalating crime, inequality, and the number of food banks (Lambie-Mumford, 2013) and shrinking opportunities in job and housing markets for the increasing section of Britain’s population (Bone and O’Reilly, 2010) have all been conveniently ‘forgotten’ by the newspapers. Such intentional discursive amnesia makes understanding the causes behind the ‘resource drain’ of migrants impossible. This oversight makes it easy to assign blame for depleting resources on incoming migrants. By doing this, the newspapers actively participate in a kind of cover-up operation. They conceal painful truths at home and indulge in vilifying those who carry no responsibility for the state of the British economy.

This systematic politics of forgetting, the ‘historical amnesia’ employed by the media, produces accounts that do not ‘remember’ the specific contexts in which Britain’s imperial adventures, exploitation, resource-theft, violence, domination, slavery, and forced labour, produced the conditions of poverty, conflict, and mass migration (Krishna, 2001; Seth, 2011), to form the foundations of today’s global inequality. Such forgetting also naturalizes the British economic strength as exceptional, an outcome of Britain’s own creation, and refuses to acknowledge the non-Western world’s role in its emergence. A ‘full recognition’ of such repressed histories (Prakash, 1995, p. 5), explaining how the past affects the present does not have a home in British media.

This amputated truth, sanitized vision of the present, and plain denial of history promoted by the media do not educate the audience. Blissfully unaware of their violent histories, British audiences are not presented with full contexts that could allow them to connect the causes of conflicts and poverty, and subsequent populations’ movements. In the face of incoming refugees and deaths at the border, the public takes no responsibility for human suffering and instead demand ‘security measures.’ Disconnected from their underlying causes, refugees’ mobility and deaths come to be seen as natural events (Oliveri, 2016). Their deaths become the ‘result of atavistic religious or ethnic conflicts and as intrinsic to racialised communities in non-Western countries. In the most paranoid versions of this logic, migrants threaten to import the “barbaric” worldviews into Western cultures, provoking social conflict’ (Forkert et al., 2020, p. 23).

Conclusion

This paper has argued that media representations of mobility in Britain advance the racialised mix of knowledge and historical amnesia that reproduce age-old hierarchies of the colonial system. There is also a troubling convergence between visions of the Self and racialised outsiders on different sides of the political spectrum. Representations of mobility by The Guardian and The Times, Britain’s left-wing and centre-right newspapers, respectively, reproduce visions of the ‘invasion’ that, although in different ways, nevertheless produce a vision of ‘threat’ to the British nation and give rise to racist organizations of society. Their colonial practices continue to orientalise and racialise non-Western populations and reproduce their subordinate place in a hierarchical relationship with Britain. Media produce abject subjectivities and divide humans into active and capable on the one side and those associated with danger and a drain on resources or inability, on the other. Fanon’s colonial world of orderly ‘us’ and dangerous, inferior and disorderly ‘them’ continues into the present, as media discourses propel the creation of racial superiority aligned with the British nation whose inner qualities exclude most of the global population.

The study has revealed that racism is reproduced today through discourse that generates culturally prejudiced knowledge and that formulate refugees as Europe’s new ‘enemy.’ ‘Race’ is constructed as a ‘socio-political fact of domination’ that constantly replicates ‘hierarchies of social power, wealth, and prestige enforced through violent and oppressive regimes of (European/colonial) white supremacy’ (De Genova, 2018, p. 1770). Media discourses of ‘migration,’ and the racial categories that it sustains, extend colonial power enacted in the former British Empire. Categorizing people into those with or without rights of entry and residency sustains and reproduces colonial racial hierarchies. Media discourse thus maintains the global racial order established by imperialism and settler colonialism. Racialised populations are deprived of access to resources, healthcare, safety, and opportunity and are systematically made vulnerable to harm and premature death. However, unlike colonial discourses that produced a racial order in the colonies, the contemporary media discourse replicates colonial epistemology out of the colonies, back at home. It brings the bifurcated world invented ‘out there’ to organize social life ‘in here’ and provides an epistemic foundation for the creation of structures of coercion, exploitation, and control over racialised populations on domestic soil.

The construction of migrants as an inferior category that either threaten Britain or depend on it for their survival, precludes alternative political possibilities: what if media were to challenge the practices of the British state and interrogate British foreign interventions that produce human suffering, the main reason behind mass mobility? What if they questioned Britain’s economic model that has historically relied on cheap and racialised workforce, which has produced unprecedented levels of hardship and poverty over the years? Why not interrogate the movement of capital rather than the movement of labour? Instead of sustaining the bifurcated world of benevolent ‘us’ and malicious ‘them,’ why not offer a vision of justice?

Media could contribute to changing social practices. They could challenge the ‘rules’ governing voice, agency, and representation. They could strive to reverse the inequality and injustice, produced by social norms and discursive practices. They could portray migrants and refugees differently than victims of history, objects of pity and charity, or welfare abusers. They could offer them voice and space to share their own understandings of the world. They could include discourses of migrants’ heroism to imply agency or discourses of everyday life that could shift the focus away from security and legal protections toward life supporting measures like education, skills development, and life opportunities, talents that migrants can contribute to host societies. Moreover, the media could acknowledge the role of British industries in environmental degradation, their earlier imperial exploitation, or global inequalities that they have produced in coverage of the mass displacement of people. The exploration of history, culture, and experiences of the incoming people combined with reflection on Britain’s role in the world could help reverse the hierarchy of power and knowledge constructed through the media coverage.

Yet, the British media choose not to do so. They prefer not to ask the question: what does history, Britain, daily life in the Global South, and migration look like when considered from the migrant point of view—from the bottom-up rather than the top-down. The presence of migrant voices in stories told to British audiences in news media would have domestic and international implications. Domestically, it would challenge received understandings of the righteousness of the British economic model and of the British community. Internationally, including migrant voices would make it possible to imagine a Britain engaged with its past, and looking into the future, alongside those who were once part of it—those downgraded to nation-states after the fall of empire who have since been made invisible. Acknowledging their contributions, past and present, to Britain’s strength would produce a Britain worthy of the world’s respect and emulation.

Data availability

Data that underpinned parts of this paper is available at: http://projectmad.civitas.edu.pl/ Contact the Author for more details.

Notes

The key media outlets included television outlets: BBC, Channel 4, ITV, BBC News, SKY News, newspapers: Daily Express, Daily Mail, Daily Mirror, Daily Star, Daily Telegraph, The Times, The Guardian, The Observer, the Independent, The Sun, London Evening Standard, Metro, as well as weekly papers: The Economist and Statesman.

All citations provided in later sections of this article come from peak coverage in the period 2015–2018.

References

Aalberg T, Iyengar S, Messing S (2012) Who is a ‘deserving’ immigrant? An experimental study of Norwegian attitudes. Scand Political Stud 35(2):97–116

Abbas MS (2019) Conflating the Muslim refugee and the terror suspect: responses to the Syrian refugee “crisis” in Brexit Britain. Ethn Racial Stud 42(14):2450–2469

Ahmed NM (2003) Behind the war on terror: western secret strategy and the struggle for Iraq. Clairview Books

Akkerman T (2011) Friend or foe? Right-wing populism and the popular press in Britain and the Netherlands. Journalism 12(8):931–945

Allen W (2016) A decade of immigration in the British press. Migration Observatory Report. COMPAS. University of Oxford

Altheide DL (2004) Consuming terrorism. Symb Interact 27(3):289–308

Baker P, Gabrielatos C, Khosravinik M, Krzyżanowski M, McEnery T, Wodak R (2008) A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press. Discourse Soc 19(3):273–306

Balch A, Balabanova E (2016) Ethics, politics and migration: public debates on the free movement of Romanians and Bulgarians in the UK, 2006–2013. Politics 36(1):19–35

Barnett L (2002) Global governance and the evolution of the international refugee regime. Int J Refug Law 14(2 and 3):238–262

Bassil NR (2011) The roots of Afropessimism: the British invention of the “dark Continent”. Crit Arts 25(3):377–396

Berda Y (2013) Managing dangerous populations: colonial legacies of security and surveillance. Sociol Forum 28:3

Berry M, Garcia-Blanco I, Moore K (2016) Press coverage of the refugee and migrant crisis in the EU: a content analysis of five European countries. Report prepared for the United Nations High Commission for Refugees

Bhambra G (2016) Brexit, the Commonwealth, and exclusionary citizenship, Open Democracy, 8 Dec 2016

Bhattacharyya G, Elliot-Cooper A, Balani S, Nişancıoğlu K, Koram K, Gebrial D, El-Enany N, de Noronha L (2020) Empire’s Endgame: racism and the British state. Pluto Press, London

Bleich E, Stonebraker H, Nisar H, Abdelhamid R (2015) Media portrayals of minorities: Muslims in British newspaper headlines, 2001–2012. J Ethn Migr Stud41(6):942–962

Blinder S, Allen WL (2016) Constructing immigrants: portrayals of migrant groups in British national newspapers, 2010–2012. Int Migr Rev 50(1):3–40

Bone J, O’Reilly K (2010) No place called home: The causes and social consequences of the UK housing “bubble”. Br J Socio 61(2), 231–255

Boomgaarden HG, Vliegenthart R (2009) How news content influences anti‐immigration attitudes: Germany, 1993–2005. Eur J Political Res 48(4):516–542

Boomgaarden HG, Vliegenthart R (2007) Explaining the rise of anti-immigrant parties: The role of news media content. Elect Stud 26(2):404–417

Böröcz J (2021) “Eurowhite” Conceit, “Dirty White” Ressentment: “Race” in Europe. Sociol Forum 36(4):1116–1134

Breen MJ, Devereux E, Haynes A (2006) Fear, framing and foreigners: the othering of immigrants in the Irish print media. Int J Crit Psychol 16:100–121

Briefing Paper (1948) When the war was over: European refugees after 1945. Briefing Paper No. 6. Coming to Britain, University of Nottingham

Brüggemann M, D’Angelo P (2018) Defragmenting news framing research: reconciling generic and issue-specific frames. In Paul D’Angelo (ed): Doing news framing analysis II. Routledge, pp. 90–111

Burrell K, Hopkins P, Isakjee A, Lorne C, Nagel C, Finlay R, Botterill K (2019) Brexit, race, and migration. Environ Plan: Politics Space 37(1):3–40

Burscher B, van Spanje J, de Vreese CH (2015) Owning the issues of crime and immigration: the relation between immigration and crime news and anti-immigrant voting in 11 countries. Elect Stud 38:59–69

Butterworth J, Burton J (2013) Equality, human rights and the public service spending cuts: do UK welfare cuts violate the equal right to social security? Equal Rights Rev11:26–45

Campbell D (1993) Politics without principals: sovereignty, ethics, and the narratives of the Gulf War. Lynne Rienner Publishers, Boulder

Cheregi BF (2015) The media construction of identity in anti-immigration discourses: the case of Romanian immigrants in Great Britain. Romanian J Journalism Commun/Rev Romana Jurnalism Comun 10:1

Chouliaraki L, Georgiou M, Zaborowski R, Oomen WA (2017) The European ‘migration crisis’ and the media: a cross-European press content analysis, Project Report

Cooper F (2014) Africa in the World. Harvard University Press

Cooper F, Stoler AL (Eds.) (1997) Tensions of empire. Berkeley: University of California Press

Davies A (2013) ‘Right to Buy’: the development of a Conservative Housing Policy, 1945–1980. Contemp Br Hist 27(4):421–444

De Genova N (2018) The “migrant crisis” as racial crisis: do Black lives matter in Europe? Ethn Racial Stud 41(10):1765–1782

De Genova N (2016) The ‘crisis’ of the European border regime: towards a Marxist theory of borders. Int Soc 150:31–54

Dennison J, Geddes A (2018) Brexit and the perils of ‘Europeanised’ migration. J Eur Public Policy 25(8):1137–1153

Derrida J (1981) Positions. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

De Vreese CH, Boomgaarden HG, Semetko HA(2011) (In) direct framing effects: Theeffects of news media framing on public support for Turkish membership in theEuropean Union Commun Res 38(2):179–205

Dorling D, Tomlinson S (2019) Rule Britannia: from Brexit to the end of Empire, Biteback Publishing

Eberl JM, Meltzer CE, Heidenreich T, Herrero B, Theorin N, Lind F, Strömbäck J (2018) The European media discourse on immigration and its effects: a literature review. Ann Int Commun Assoc 42(3):207–223

El-Enany N (2020) (B)ordering Britain: law, race and empire. Manchester University Press

Fairclough N (1995) Critical discourse analysis. Longman, London

Fairclough N (1993) Critical discourse analysis and the marketization of public discourse: the universities. Discourse Soc 4(2):133–168

Fanon F (1961/2007) The wretched of the earth. Grove/Atlantic, Inc

Farrall S, Hay C, Jennings W, Gray E (2016) Thatcherite ideology, housing tenure and crime: the socio-spatial consequences of the right to buy for domestic property crime. Br J Criminol 56(6):1235–1252

Forkert K, Oliveri F, Bhattacharyya G, Graham J (2020) How media and conflicts make migrants. Manchester University Press

Foucault M (1996) Foucault Live: collected interviews, 1961–1984

Foucault M (1991) Governmentality. In: Burchell G, Gordon C, Miller P (eds) The Foucault: studies in governmentality. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Foucault M (1980) Power/knowledge. In: Gordon C (ed) Pantheon Books, New York

Foucault M (1977) Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison (trans: Sheridan A). Penguin Social Sciences

Frontex (2019) 2018 in Brief’; European Border and Coast guard Agency; 14 March 2019. Frontex

Gabrielatos C, Baker P (2008) Fleeing, sneaking, flooding: a corpus analysis of discursive constructions of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press, 1996–2005. J Engl Linguist 36(1):5–38

Gilroy P (1987) There ain’t no Black in the Union Jack. Hutchinson, London

Haglund DG (2012) Yalta: the price of peace. Pres Stud Q 42(2):419

Hall S (1997) The work of representation. Representation 2:13–74

Hall S (1993) What is this” black” in black popular culture? Soc Justice 20(51–52):104–114

Hamnett C (2014) Shrinking the welfare state: the structure, geography and impact of British government benefit cuts. Trans Inst Br Geogr 39(4):490–503

Harteveld E, Schaper J, De Lange SL, Van Der Brug W (2018) Blaming Brussels? The impact of (news about) the refugee crisis on attitudes towards the EU and national politics. J Common Market Stud, 56(1), 157–177

Hobolt SB (2016) The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent. J Eur Public Policy 23(9):1259–1277

Hobson JM (2013) The other side of the Westphalian frontier. Postcolonial theory and international relations. Routledge

Igartua JJ, Barrios IM, Ortega F, Frutos FJ (2014) The image of immigration in fiction broadcast on prime-time television in Spain. Palabra Clave 17(3):589–618

Johnson S (1988) NEO-Colonisation of Africa and the OAU. India Q 44(1–2):59–82

Kay D, Miles R (1988) Refugees or migrant workers? The case of the European volunteer workers in Britain (1946–1951). J Refug Stud 1(3-4):214–236

Kemp PK, Lloyd C (1960) The brethren of the coast: The British and French buccaneers in the south seas. London

Kitson M, Michie J (1996) Britain’s industrial performance since 1960: underinvestment and relative decline. Econ J 106(434):196–212