Abstract

Across societies, cultures, and political ideologies, autonomy is a deeply valued attribute for both flourishing individuals and communities. However, it is also the object of different visions, including among those considering autonomy a highly valued individual ability, and those emphasizing its relational nature but its sometimes-questionable value. A pragmatist orientation suggests that the concept of autonomy should be further specified (i.e., instrumentalized) beyond theory in terms of its real-world implications and usability for moral agents. Accordingly, this latter orientation leads us to present autonomy as an ability; and then to unpack it as a broader than usual composite ability constituted of the component-abilities of voluntariness, self-control, information, deliberation, authenticity, and enactment. Given that particular abilities of an agent can only be exercised in a given set of circumstances (i.e., within a situation), including relationships as well as other important contextual characteristics, the exercise of one’s autonomy is inherently contextual and should be understood as being transactional in nature. This programmatic paper presents a situated account of autonomy inspired by Dewey’s pragmatism and instrumentalism against the backdrop of more individual and relational accounts of autonomy. Using examples from health ethics, the paper then demonstrates how this thinking supports a strategy of synergetic enrichment of the concept of autonomy by which experiential and empirical knowledge about autonomy and the exercise of autonomy enriches our understanding of some of its component-abilities and thus promises to make agents more autonomous.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Across many societies, cultures, and political ideologies, the concept of autonomy designates a deeply valued attribute of flourishing for both individual persons and communities (Chirkov et al., 2003; Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Ryff, 2014). Accordingly, autonomy is a key concept in ethics and philosophy and has been examined from many perspectives in a range of fields, from psychology to political science. In psychology, it has been articulated as a goal of human development, related to self-actualization (Maslow, 1970; Rogers, 1961; Ryan and Deci, 2000); in ethics and political theory, it has been described as a value related to the rights of individuals to have their decisions respected as long as they do not impede the rights of others (Dworkin, 1988; Kant, 1994 [1785]; Mill, 1956 [1859]). While the concept of autonomy is widely regarded as important, it is also deeply contested and debated in numerous social contexts, complicated by the need to balance the weight attributed to autonomy with other values and principles (Callan, 1997; Beauchamp and Childress, 2012). Beyond this unavoidable balancing, situations evoking concerns about autonomy are also marked by a number of uncertainties and sometimes confusion about the nature of autonomy (descriptive concerns, i.e., about what autonomy is) and about its function (normative concerns, i.e., about why autonomy is valued and whether it leads to positive experiences). To faithfully describe autonomy as an ethical concept, we must attend to both of these sets of concerns: autonomy would be irrelevant to ethics were it not valued, and autonomy would not be useful were it not describable in concrete and effective terms.

In this programmatic paper, we propose to deepen understandings of autonomy based on insights from pragmatist theory, as well as theories and research from contemporary psychology on autonomy and human flourishing (Ryan and Deci, 2000; Ryff, 1989; Ryff and Singer, 2008; Ryff, 2014). In doing so, we adopt an instrumentalist strategy of ethics concept analysis and enrichment pioneered by Peirce generally and Dewey in the context of ethics (Racine, 2017; Racine et al., 2017c). This strategy calls for the clarification and establishment of the meaning of an ethics concept based on its implications, i.e., what the concept achieves, analogously to a tool or an instrument. We first explain key features of this unconventional pragmatist and instrumentalist view of ethics concept analysis, notably the need to envision ethics concepts as instruments for both moral problem solving and the pursuit of a flourishing life. We then propose to “instrumentalize” autonomy through the novel concept of “contextualized autonomy.” We situate this proposal within a cursory review of influential accounts of autonomy. The contextualized account envisions autonomy as an ability that represents an agent’s capacity to transact with their environment in certain ways. This ability is intrinsically valued because it is a cornerstone of a flourishing life. Therein, the concepts of autonomy—like other meaningful ethics ideas— becomes an instruments supporting valuable life experiences.Footnote 1 We also explain how, following this orientation, autonomy can be fruitfully considered a complex composite ability involving the component-abilities of voluntariness, information, self-control, deliberation, authenticity, and enactment, instead of an ability definable in terms of a single criterion (e.g., rationality, voluntariness). This view helps make sense of the fact that autonomy is intimately related to human experiences, and that the normative value of autonomy is related to the kinds of positive and enriching experiences that this idea allows. Impoverishment of autonomy is also possible in situations of heteronomy, alienation, and so on.

To further expand on this idea of mutual reciprocity between knowledge and experience, we follow a process of synergetic concept enrichment inherent to instrumentalist concept analyses (Racine, 2017; Racine et al., 2017c). This process reflects the nature of concepts as tools; it encapsulates that theory and experience reciprocally nurture each other. To illustrate this process, we draw on disciplines not typically considered to be foundational for theories of autonomy (at least in ethics), namely social work, disability studies, and psychology, but which reveal how autonomy is enacted and can be supported in practice. Preliminary practical implications of this enrichment are discussed with a focus on healthcare contexts, chosen here for practical reasons given the background of the authors. Furthermore, autonomy has dominated discussions in health ethics and allows for a meaningful exploration of the mutual relationship between theory and application. We conclude by drawing on knowledge that enriches our concept of autonomy by shedding light on the nature of the component-abilities of information, self-control, and authenticity, as well as on facilitators and barriers to these abilities. We consider interdisciplinary evidence about agent-related factors, context-related factors, and factors related to the interaction between agents and contexts that contextualize the experience of each component-ability. This paper is programmatic insofar as it enacts and operationalizes a pragmatist approach to autonomy in a way that offers a direction for future conceptual and empirical work and builds from a wide range of scholarly contributions without providing fine-grain arguments and analysis for all its claims. In this spirit, it steps away from traditional philosophical work on autonomy and engages with scholarships from a vast array of humanities and social science disciplines.

Pragmatism and instrumentalist ethics concept analysis of autonomy

Our proposal for instrumentalizing contextual autonomy as a complex composite ability is inspired by pragmatism. Pragmatism refers to a rich intellectual tradition that emerged from the work of a diverse group of scholars who proposed similar, yet somewhat different positions and claims about the nature of knowledge, meaning, morality, science, education, and democracy, amongst others (Legg and Hookway, 2019; Martela, 2015; McDermid, 2006; Misak, 2013). Inspired by the foundational work of Peirce (1877; 1878), pragmatists typically endorse the use of scientific methods for the examination of all domains of life and inquiry by valuing experience and rejecting a priori notions, ones related to “metaphysical truths” or infallible knowledge, notions unspecifiable in terms of their implications and of inquiries into their implications. A chief reason for this is that for pragmatists, the meaning of a concept is best understood, or best clarified in terms of its implications (Peirce, 1877; 1878). From this perspective, it is insufficient to draw only on abstract and theoretical reasoning and definitions of concepts and principles; instead, theory needs to identify avenues for empirical research to test out and enrich various concepts so that they can be held accountable for what they purport. Providing a definition is what Peirce described as a “second grade clarity” of a concept, whereas being able to base the meaning of a concept on its functions and implications represents a third and higher standard. However, in order to refine the meaning of a concept in this way, one must understand its implications, hence the important role of empirical research (or “inquiries” in Peirce and Dewey’s words) that capture, here for example, the experience of autonomy in action (Racine et al., 2019).

Following Peirce, DeweyFootnote 2 proposed that ethics concepts ought to be also considered as instruments in the resolution of “morally problematic situations” and in thinking practically about and actually facilitating a life of growth and fulfillment (Dewey, 1922; Dewey and Tufts, 1932). Here a situation refers to a unit of experience that reflects the constant transactions occurring between human beings and their environments. Even the thinking we undertake to grasp these situations is transactional and is in a sense purposive as it reflects intentions because human thinking is pervasively action-oriented (Dewey, 1941; Martela, 2015). These ideas suggest that ethics concepts and principles are valuable, relevant, and true insofar as they help moral agents enact the kinds of positive and enriching experiences that they point to (or avoid negative and diminutive experiences) in the context of a flourishing life (Racine et al., 2019). This stance radically differs from stances where the value of ethics concepts is benchmarked to a priori and static concepts (Lekan, 2006). For those who follow Dewey’s insights, ultimately, ethics concepts and principles need to be assessed and considered instruments inasmuch as they are helpful in allowing individuals and communities to “grow” through the resolution of morally problematic situations (Pekarsky, 1990; Pappas, 2008). This does not imply that ethics is only about problem solving, but rather that it situates confrontation to and the solving of difficult moral situations within a life of flourishing and growth.

In many ways, Dewey’s concept of growth is a modern rendition of the ancient concept of Eudaimonia (flourishing or well-being) described by Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers such as Aristotle (Chambliss, 1993; Fahey, 2010). Growth here refers to a dynamic process where agents gain more meaning out of human experiences. These experiences reflect a greater sense of connectedness with other human beings and with one’s own existence (Pekarsky, 1990). Pekarsky described this growth as “ordered richness” because the sign of growth is the acquisition of a richer perspective on and richer meaning of human experience in ways that allow individuals (and communities) to live more meaningful lives and resolve morally problematic situations (1990).Footnote 3 This centrality of meaning and purpose to life is now well recognized and evidenced in contemporary psychological understandings of human flourishing (Zika and Chamberlain, 1992) and capabilities-based approaches (Aiguier and Loute, 2016; Sen, 2000).

Our instrumentalist analysis of autonomy follows this pragmatist strategy, which can be applied to the analysis of any ethics concepts and principles. This strategy leads us to ask whether what is designated by a given ethics concept (e.g., autonomy) and the function suggested by a given related principle (e.g., principle of respect for autonomy) is actually useful in helping agent(s) reach a desired goal (e.g., to be or become autonomous) (Martela, 2017; Racine, 2017; Racine et al., 2017c; Racine et al., 2019) and whether this goal in this context is consistent with a flourishing life. Within such a pragmatist and instrumentalist view, autonomy is deeply valued because it is a condition and a goal in the process of growth, consistent with modern theories of Eudaimonia where autonomy is prominently featured (Ryan and Deci, 2000; Ryff and Singer, 2008; Ryff, 2014). However, whether or not the concept of autonomy is useful in helping us enact autonomous choices and behaviors should remain an open question. In other words, following Dewey, ethics concepts and principles like autonomy remain hypotheses in the sense that they demand to be “tested” or “explored” in real-world settings to see whether or not they are useful tools or instruments. This implies that empirical evidence on the value of proposed understandings of autonomy be fed back to re-assess critically whether the tool is useful to achieve the goal sought. This explains why Dewey adamantly argued for the radical role of empirical research in ethics to avoid vacuous and unhelpful ethics theory.

An instrumentalist approach to ethics concept analysis requires that, at minimum, both a descriptive account (what it is) and an evaluative account (why it matters, which function it serves) of an ethics concept be provided. Once the function or goal of a given concept such as autonomy is identified and analyzed, and the experiences it designates better circumscribed, then the concept can be potentially enriched through the existent breadth of literature and lived experience (Racine et al., 2017a,b; Racine et al., 2017c). Eventually, from the user standpoint promoted by pragmatism, an enriched concept will be tested by agents dealing with some moral struggle (e.g., a moral conflict, dilemma, or tension), seeking resolution in order to assess whether or not the concept leads to richer and more satisfactory experiences (Racine, 2017; Racine et al., 2019). These kinds of experiences are then fed back to revise how we envision and value autonomy following an iterative process of enrichment (Martela, 2017). We undertake this task below, beginning with a description of intellectual trends in conceptualizing autonomy, then evaluating the function of autonomy in various healthcare-related contexts, and ultimately enriching the concept by drawing on interdisciplinary empirical and experiential research. We conclude with suggestions for applications and future research.

A pragmatist account of contextualized autonomy

Major influential trends have shaped ideas about autonomy, notably the description of autonomy as an abstract property of individual agents (e.g., Kant), and the relational accounts of autonomy that stress the importance of recognizing its relational aspects (Mackenzie and Stoljar, 2000). For example, from the influential Kantian perspective, autonomy is a rather abstract but highly valued ability to self-govern and self-determine. Accordingly, autonomous actions are described as those actions characterized by the “presence of freedom, rationality, and consistency with one’s own preferences” (Agich, 1994, pp. 267).Footnote 4 Furthermore, “the autonomous person is idealized as a free, rational, agent who is able to make choices based on his [sic] own preferences” (Agich, 1994, pp. 267). This description captures a widespread notion of autonomy that requires freedom from influences/external factors, which leads to a notion of an agent who is often understood as being abstracted from relationships and social contexts in order to count as autonomous.

This account of individual autonomy has been criticized not only by advocates of the concept of relational autonomy (Mackenzie and Stoljar, 2000),Footnote 5 described in greater detail below, but also by other more mainstream theorists of autonomy such as Dworkin (1976) and more recently by the bioethicists Beauchamp and Childress (2012). These latter authors have made the case that no individual is ever completely free, given that individuals are immersed in and are influenced by their social environments. Dworkin also relativizes the criterion of complete freedom by specifying that an individual must not be overly influenced by external factors in order to count as autonomous. Furthermore, following Frankfurt’s classic analysis, he and other more contemporary scholars view autonomy as a capacity to exhibit second-order beliefs/desires that allows agents to ponder about their first-order beliefs/desires and to decide whether or not to follow them (Frankfurt, 1971; Dworkin, 1988). By extension, autonomy can be threatened by coercion, manipulation, brainwashing or covert influences that restrict the individual’s ability to reflect upon their “first-order” desires (Dworkin, 1976). Yet, in spite of these nuances, there remains an ongoing tension between the abstracted nature of autonomy as an ability to self-govern and its relationship to all the concrete factors, which can influence this ability. This is sometimes described as the problem of the “porosity of autonomy” because the free abstracted agent is hard to understand as isolated from biological and social realities (Morar and Beever, 2016; Racine, 2016).

One of the key insights offered by relational accounts of autonomy is that previous scholarship too often considered autonomy to be the property of an abstract moral agent in such a way that the role of relationships and social context was not sufficiently recognized. Relational accounts of autonomy acknowledge both the positive and negative impact of the social environment on the agent’s autonomy. These accounts claim that some forms of oppression like sexism (e.g., the idea that women are “primarily valued […] in terms of their instrumental role as mothers” (McLeod and Sherwin, 2000) are autonomy-diminishing factors that are left out by previous accounts of individual autonomy. McLeod and Sherwin (2000) argue that oppression might even become internalized by an agent without being noticed by them. Internalization leads to a change in the agent’s values, beliefs and self-perception and thereby following “one’s own” desire might in fact not be as autonomous as it would be predicted. Thus, an individual’s autonomy is shaped by their social context. In short, relational accounts and feminist critiques of autonomy fundamentally challenge the common way of describing autonomy as an abstract ability by bringing to the forefront its relational aspects.

Despite the evolution of views on autonomy as an abstract property to that of a relational property (Morar and Beever, 2016), there remain gaps to bridge between the abstracted nature of autonomy and its actual realization in webs of social relationships (Taylor, 1992). For example, does further understanding of real experiences of autonomous choices and behaviors (and limitations to autonomy) undermine the actual existence of this ability? This is often presumed to be the case (Morar and Beever, 2016; Felsen and Reiner, 2011), but this question is handled differently from a pragmatist standpoint because pragmatism relies on an epistemology stressing the connections between theory (abstraction) and practice (the experiential). Indeed, “[p]ragmatism is a philosophical tradition—that very broadly—understands knowing the world as inseparable from agency within it.” (Legg and Hookway, 2019).

From a pragmatist standpoint, it is important to recognize the influential insights gleaned from the more conventional and the more recent feminist scholarship on autonomy, notably the recognition of autonomy as a value, as well as the acknowledgement of its abstract characteristics sometimes exacerbated in individualistic accounts of autonomy and self (Taylor, 1992). However, it is also important to note that the scholarship on autonomy is sometimes inconsistent with the tenets of pragmatism that honor knowledge from multiple sources and from lived experiences, since there has been limited attention to the rich accounts of the lived experience of people undertaking autonomous (or non-autonomous) decisions and actions. Indeed, discussions on autonomy have gloosed over its factual and experiential aspects (Racine et al., 2012; Racine and Dubljević, 2016; 2017; Zizzo et al., 2017). From a more traditional standpoint, a pragmatist and empirical approach risks begging the question: if one defines an account of autonomy based on studying people making autonomous actions, how do we know who is taking autonomous actions in the first place? Obviously, this kind of circularity is not what we have in mind, and so we instead refer readers to writings on methods for instrumentalist analyses of ethical concepts that are iterative and attempt to transform static and essentialized concepts into operational, dynamic and functional ones in light of their practical implications (Racine, 2017; Racine et al., 2017c). Traditionally, factors shaping the actual exercise of autonomy are often seen as a threat to autonomy itself most clearly because autonomy is envisioned as an abstract yet valuable ability. However, evidence about limitations or obstacles to autonomy is not interpreted as a challenge to the value of autonomy itself within a pragmatist approach (Racine et al., 2019; Racine and Dubljević, 2017).

In the following paragraphs, to extend individual and relational accounts of autonomy, we propose a concept of contextualized autonomy, addressing both the descriptive and normative aspects mentioned above. This account was first introduced in the context of policy implications in advanced testing for pre-clinical states of Alzheimer’s disease (Racine et al., 2017a; Racine et al., 2019) in line with observations about patient preferences for autonomy and choices in concrete situations (Forlini and Racine, 2009; Racine et al., 2012; Zizzo et al., 2017). It was expanded upon in discussions on the contribution of neuroscience in agency and autonomy (Racine, 2016; Racine and Dubljević, 2017) and the impact of research on free will on our understandings of volition more generally (Racine, 2017), as well as in the context of addiction (Racine and Rousseau-Lesage, 2017). We here build from this work to provide greater conceptual clarity and pathways for a more concrete instrumentalization of the concept of autonomy.

What is autonomy: a valued and contextualized ability (contextualized autonomy)

An account of “contextualized autonomy” differs from influential individualistic or relational accounts (Table 1). As its name suggests, it is grounded in a contextual understanding of moral agency, in which autonomy plays an important role as an ability composed of several component-abilities such as voluntariness and information, which are described below.

Within a more traditional individual account of autonomy, autonomy is valued because it is intrinsic to the view of the individual as someone who is able to self-govern in the sense of setting their own goals and norms that can guide their behavior (Chirkov et al., 2003; Green, 2001). This insight led Kant to call for the recognition of the dignity of persons and the imperative to respect all persons’ self-governing capacity (Kant, 1994 [1785]). This important normative insight is captured in Kant’s ethics where he postulates a “Kingdom of Ends” as an ideal of the moral human community (Kant, 1994 [1785]). On less philosophical grounds, the constitutions of liberal democracies and republics usually spell out a number of fundamental rights and freedoms, which are consistent with the importance attributed to autonomy by Enlightenment thinkers like Rousseau and Kant (Taylor, 1992). However, we usually do not expect that those rights be exercised in a highly rational way. In other words, stringent criteria of rationality or authenticity are not necessary to justify one’s decisions and actions because the law grants a generous understanding of autonomy and basic human rights to allow individuals to pursue their associations (freedom of association), their beliefs (freedom of religion), and their communication (freedom of speech) in sometimes debatable or even irrational ways. In short, people are granted the right to self-govern with leeway with respect to the reasoning behind a particular decision.

However, this push toward respecting autonomy as an abstract and general ability has tended to be understood in ways that ignore the context in which the individual exerts autonomy, notably because of the underlying influential Kantian normative/descriptive dichotomy that leads to disregarding more factual aspects of situations. Progressively, this more canonical view of individual autonomy has been improved upon by many authors, because the reciprocal influence of individuals’ autonomy and the social environment in which they are embedded has come to be recognized (Beauchamp and Childress, 2012), even though defining how and to what extent these factors interact remains to be clarified (Racine and Dubljević, 2017). For example, the informational aspect of autonomy has been given a significant amount of attention in contexts like clinical care and research where the doctrine of informed consent requires that the moral agent be informed regarding such things as the nature of care they will receive or the harms and benefits of research participation. Research ethics has shown that moral agents are typically not well informed or do not retain crucial aspects of research such as the risks involved, implying that while information may be available and may be provided, the likelihood and propensity of its uptake by moral agents is less clear (Beauchamp and Childress, 2012). Strategies have been trialed to improve information uptake (Hadden et al., 2017). However, other aspects of autonomy such as voluntariness have been the objects of much less attention (Mamotte and Wassenaar, 2015).

Some feminist scholars, notably those tackling relational autonomy and the relational self, have asked important questions about autonomy and challenged the ways in which certain expressions of autonomy have been valued and made more dominant than others. Various social factors, such as racial, sexual, and political oppression influence the degree of autonomy individuals can access (McLeod and Sherwin, 2000), but these have been traditionally neglected. The neglect of these social factors points to broader structural problems that may need further intersectional analysis, as they are symptomatic of an uncritical valuation of autonomy, implicitly reflecting a hegemonic gendered (masculine or male) view on agency and on what is valued in human life (Gilligan, 2001). Alternatively, some feminist theories of agency highlight the importance of examining relationships and social conditions— notably gendered caregiving roles assumed by women and girls—and thus yield another account of moral agency where duties and obligations to others (e.g., to vulnerable populations or groups) take precedence and where individual autonomy is situated within a richer understanding of what needs to be valued (Baylis et al., 2008). In this sense, autonomy is considered relatively.

Here a tension remains as to whether autonomy— granted that its valuation is influenced by social positioning and context—should actually be valued, and for which reasons, and in the context of which other values and goods should it be pursued? As we will see, a pragmatist account of autonomy recognizes that autonomy is grounded in experience, which is shaped heavily by personal trajectory, social context, and culture and that it is, in this sense, relative (consistent with relational accounts) but that, nonetheless, autonomy can be valued (consistent with traditional individual accounts) although not as a mere quintessence of ethics. However, within a pragmatist epistemology (Martela, 2015) and the related concept of synergetic enrichment between theory and practice (Eric Racine et al., 2019, the valuation of autonomy is open to questioning and critical analysis based on inquiries about the implications of autonomous choices and behaviors.

Autonomy as an ability

From a pragmatist perspective, the action-oriented nature of human thinking (Martela, 2015) means that outcomes crucially matter when it comes to defining concepts, especially when envisioning concepts as tools in the context of problem resolution (Peirce, 1878). This also applies to the context of the pursuit of a flourishing life (Pekarsky, 1990) where autonomy can be fundamentally considered as an ability of the moral agent (Raz, 1986). The language of ability here represents a departure from spectator theories (Dewey, 1929; 2004 [1916]) of the person and of autonomy, which consider autonomy a sort of abstract, valued trait or principle. Moreover, “ability” designates the active potential of exercising autonomy, contrary to spectator analyses that view autonomy as a possession that is static in nature. Thus, from this standpoint, the idea that autonomy is a kind of ability departs from accounts that describe it as a value, as a principle, or a kind of relational property.

Autonomy as a contextualized ability

The notion of autonomy as an ability rather than a relational or abstract property helps explain why acknowledging context is crucial, since as an ability, autonomy can only be exercised in a given set of circumstances, namely within a given context.Footnote 6 The pragmatist account of contextualized autonomy reflects the dynamic and transactional nature of organism-environment interactions, as well as the possibility of improving one’s ability to act autonomously or become autonomous within such a transactional framework. Agential and contextual elements, including those that are relational and social in nature (e.g., socio-economic status), as well as those that are commonly considered to be intrinsic to an individual (e.g., cognitive abilities, resources such as motivation and empathy) make up the fabric of situations in which autonomy is understood and exercised (Racine and Dubljević, 2017). Thus, by seeing autonomy as an ability of the particular agent(s) in context, the concept of contextualized autonomy brings an individual and contextual dimension to the forefront—that is, an ability that an individual exercises and can improve upon to a certain degree—that is dependent on social context, one which could either facilitate or diminish autonomy (Racine, 2016; Racine and Dubljević, 2017). Accordingly, empirical knowledge on component-abilities (see below) supports a dynamic and interactional view of autonomy, one that is not only mindful of the influence that context can have on autonomy, but also of how autonomous decisions and actions can shape the contexts they occur within (Racine, 2016; Racine and Dubljević, 2017). Again, these are ideas seldom encountered in accounts of autonomy as an abstract and acontextual ability to self-govern while they are promulgated by feminist scholars.

Autonomy as a composite ability

Influential accounts of autonomy have made certain characteristics (e.g., rationality, voluntariness, self-control) essential to autonomy. For example, irrational decisions are sometimes considered to be heteronomous, involuntary behaviors also, and so on. There are many lists of the essential components of autonomy in the literature (Felsen and Reiner, 2011; Friedrich et al., 2018). These dimensions are sometimes held in contest with one another, such that the true quintessential features of autonomy and autonomous decisions are (for example) considered to be chiefly about rationality, or alternatively, solely about voluntariness.Footnote 7 For example, Walker argues for the importance of rationality in autonomous decisions such that irrational decisions are simply non-autonomous (Walker, 2009). However, are such arguments about the necessary and sufficient conditions of autonomous decisions or behavior useful or not? These contests can promulgate fallacies of false dilemmas and dichotomies between the multiple components of autonomy. In contrast, a pragmatist account of contextualized autonomy does not weigh different components of the concept against each other or propose a definitive set of sufficient and necessary conditions for autonomy. Rather, it strives to generate the richest, most inclusive, and most insightful and helpful account of autonomy, one open to different dimensions and their varying role in different individuals and contexts.

Following this inclusive and experience-based approach to autonomy, several non-exclusive component-abilities, can help characterize autonomy and autonomous actions (Beauchamp and Childress, 2012; Christman, 2004; Dworkin, 1988; Felsen and Reiner, 2011; Friedrich et al., 2018; Racine and Dubljević, 2017). Component-abilities is perhaps a non-standard term to use here because it designates what some would perhaps call “features” or “attributes” of autonomous actions. We prefer to stress that these features are the outcomes of action such that for example informed decisions are not simply passively informed but are the result of information-seeking. Accordingly, the fact that decisions are informed is the result of the use of a multitude of abilities (e.g., information processing, memory, etc.) mobilized by the agent.

Without claiming to offer a final list, and using for now the literature on autonomy as a surrogate for more bottom-up approaches used by psychologists for item-generation (Irvine and Kyllonen, 2010), we can identify a number of component-abilities. These include (1) voluntariness, such that the motives for an action or decision can be ascribed to purposeful decisions made by the moral agent (and not prompted by coercion); (2) self-control, such that the moral agent is considered (by others and themselves) to be able to direct their actions towards a desired goal; (3) information, such that moral agents are clearly not misled by factual misunderstandings, false assumptions, or erroneous interpretations of a situation, and instead glean reliable knowledge of their situation and of possible options, pursuing trustworthy information; (4) deliberation, such that, for example, reasons or motivations of the agent can be critically examined and invoked in justifying one’s actions or decisionsFootnote 8; (5) authenticity, reflecting the agent’s fundamental values and preferences; and/or (6) enactment, as an autonomous decision, that once made, leads to action (and that when enactment is hampered, frustration results). All of these important features of autonomy have been debated and often reduced to shorter lists (Beauchamp and Childress, 2012; Felsen and Reiner, 2011) with certain features prioritized over others (Walker, 2009). They all support autonomous decisions and behavior such that taking away one of these aspects removes in some way the meaning of something being autonomous. For example, a choice that is made with limited or misleading information is difficult to consider as fully autonomous because a person decided based on erroneous information. Likewise, a decision that is not endorsed as being related to one’s values and identity, a choice made without ownership and conviction is not a choice typically considered to be autonomous because of its inauthenticity.

A pragmatist theory of contextualized autonomy considers these features as important components forming a broader composite ability of autonomy (Table 1). Altogether these components provide a richer account of autonomous decision-making and subsequent autonomous action. Accordingly, there is no need to define autonomy exclusively with respect to only one or a few of these components. Also, a contextualized account of autonomy does not imply a strong set of hierarchically organized component-abilities, suggesting that some are more valuable than others. Rather, it states that their importance and degree vary with respect to every individual action and context.

In theory, a decision or action in which all components are clearly demonstrable (e.g., voluntary, informed, and so on) is an ideal exemplification of autonomous action, while it would be the opposite for a situation where all components go unfulfilled (e.g., involuntary, uninformed, and so on). Most, if not all, concrete actions fall between these two extremes and represent variations in the exercise of the different components of autonomy. This nuance helps explain that if a given component-ability is impossible to exercise in a particular situation (e.g., when no information exists regarding a set of decisions or options), then other components take precedence in defining autonomous action. Drawing upon the context of addiction as an example, contextualized autonomy can help explain why a person risks experiencing challenges with regards to certain component-abilities, such as voluntariness or self-control (even though others may go unimpaired, such as information, deliberation, authenticity) (Hall et al., 2003; Levy, 2006; Racine and Rousseau-Lesage, 2017). Expanding on this, a pragmatist account can help circumvent pitfalls within claims that state that, for example, persons with addiction(s) can exercise full autonomy (Foddy and Savulescu, 2005), or that alternatively, these persons completely lack autonomy (Charland, 2002; 2003). These two stances are based on overly restricted accounts of autonomy that focus on specific component-abilities such as voluntariness and lose sight of other component-abilities, which are maintained in the context of addiction (Levy, 2006). In short, a contextual account better resists the notion of autonomy as being an all-or-nothing concept based on a single component-ability because if offers a richer, multifaceted account of this complex composite ability.

Autonomy is experiential (psychological)

The pragmatist account of contextualized autonomy does not ground the meaning of autonomy in the abstract or the conceptual like traditional accounts of individual autonomy (Green, 2001). Rather, as an ability, the meaning of autonomy is grounded in actual subjective and intersubjective experience of beings who are able to exercise actions in autonomous ways. In other words, autonomy is not first and foremost an abstract principle or a relational property, but an experience of the active moral agent, an experience, which can then be described in different ways using different concepts and appealing to its different components. As an experience, autonomy represents a lived, psychological, reality whose social, relational, biological and psychological aspects are worthy of and amenable to investigation (Racine and Dubljević, 2017) that go beyond mere common, social and relational aspects encountered in relational accounts of autonomy (Beever and Morar, 2016), Accordingly, a pragmatist account of contextualized autonomy does not define autonomy as being outside the realm of causality like traditional individual accounts (Kant, 1994 [1785]), for otherwise it would render this ability causally irrelevant and therefore worthless (Racine et al., 2017a; Racine and Dubljević, 2016; 2017). Accordingly, the contextual account of autonomy as an experienced (or unexperienced) ability offers a promising space for empirical ethics research given the rich and vast territory made up of the task of understanding experiences of autonomous, less autonomous or non-autonomous actions as well as the impact of these on the well-being of persons. In some individual accounts of autonomy, empirical evidence pointing to limits in autonomous decision-making or some of its subcomponents (e.g., external influences impeding voluntariness, difficulties of a person in understanding all relevant information to make a decision, etc.) can sometimes be interpreted as a threat to whether an agent’s action is genuinely autonomous or not (and therefore ethically questionable). On a contextual account, however, such evidence is not necessarily a threat. On the contrary, individuals can become empowered by such findings since they present and opportunity for overcoming barriers that impede on autonomous decision-making (Saskia and Reiner, 2013; Racine and Dubljević, 2017).

Why is autonomy valued?

Situating the starting point of an understanding of autonomy in experience also means that the value of autonomy is neither principles nor relationships, but actual lived experience and the valuations found therein. Writing about empirical ethics early on the phenomenologist Czeżowski puts it this way: “ethical principles appear as a variety of empirical hypothetical laws and, as all laws of that type, they can only be founded on inverse reasoning, with primary evaluations as the premises. The role of foundations in ethics is played not by a priori ethical principles but by empirical primary evaluations” (Czeżowski, 1953, p. 168). Analogously, the principle of respect for autonomy is grounded in lived experience, a general ethical rule of conduct that stresses the importance of respecting the valued ability of autonomy, which is rooted in such experiences and relationships. The manifestation of this ability may differ between individuals and communities (Turoldo, 2010), but it remains widely valuable as an instrument of growth because of the key role autonomy has in human flourishing (Ryff and Singer, 2008).

Without the general ability to self-govern and the component-abilities this encapsulates (detailed below), it becomes difficult to grow. Enlightenment philosophers, especially Kant (1991) detailed how a life of heteronomy is a life of depletion, of diminishment, of disempowerment/slavery, and even of alienation, depression, and apathy (Habermas, 1973; Seligman, 1975; Wegener et al., 2007). These theoretical claims are now supported by research on well-being in psychology (Ryan and Deci, 2000; Ryff and Singer, 2008), which has found autonomy to be crucial in pursuing a flourishing life of growth in which meaningful life events are enriched via experiences that provide fulfillment for oneself and others (Fischer and Boer, 2011; Pekarsky, 1990; Ryff, 1989). For example, autonomy support from parents, friends and/or romantic partners leads to higher well-being (Ratelle et al., 2013). Although differing effect sizes have been observed, the overall result holds true across different nations and cultures (Lynch et al., 2009) and autonomy is a component of well-being despite cultural differences (Chirkov et al., 2003). “Self-determination theory” developed by Ryan and Deci (2000) also shows the negative impact of heteronomy on well-being and is instructive on the value of autonomy.Footnote 9 We recognize that autonomy and self-determination as developed in self-determination theory differ, especially that autonomy is posited as one of three basic human needs within this theory (alongside competence and relatedness) and is also used as a qualifier applying to voluntary and endorsed actions.

However, autonomy is not about independence or individualism; it is about the free and voluntary endorsement of norms of behaviors. These norms can be more individualistic or collectivistic, but autonomy describes a relationship to those norms (Chirkov et al., 2003). Compromised autonomy (e.g., when the component-ability of self-control is diminished when the ego is depleted) (Wegener et al., 2007) can also generate apathy and a hopeless attitude towards the future (Baumeister, 2008; Seligman, 1975). At a macrosocial level, the value of autonomy is explicit in societies where individual rights are promoted and enshrined in constitutional law. It is also manifested in various societies and cultures that value and place importance on self-expression whether through art, encouraging children to choose their own names when they get older, or promoting the freedom of mobility in sexual and romantic relationships. The opposite of autonomy (e.g., heteronomy, alienation) are generally considered negative experiences in which the agent is not able to fulfill oneself or pursue a life of growth and flourishing. These consequences are sufficiently negative to be considered criminal offenses and fundamentally contrary to basic human rights. Pragmatism and modern theory on autonomy and well-being in positive psychology (e.g., empirical evidence emerging from self-determination theory), therefore demonstrate that autonomy is highly valued for the very simple reason that it represents an ability broadly conducive to positive experiences and a healthy existence. These clarifications on where the value of autonomy comes from, i.e., from experience rather than some a priori justification, have both practical and epistemological implications.

Practically speaking, it means that empirical research on whether and how various aspects of autonomy-as-an-ability can be a positive factor in well-being and growth provide anything that could stand as an “ultimate foundation” for contextualized autonomy, broadly considered, granted here that this notion of foundation be understood as fallible and susceptible to empirical investigation. Principles, such as respect for autonomy, are grounded in the positive contributions that autonomy makes to individual well-being and flourishing. If autonomy is not found to contribute to individual well-being (e.g., in a particular contextFootnote 10), then the function and purpose of principles like respect for autonomy must be reconsidered. The fact that valuations originate in experience has a direct implication: ethics must support a return to a form of enriched experience and growth (Martela, 2017; Pekarsky, 1990).

From a more epistemological and methodological point of view, the explanation of autonomy as a generally positive valued ability opens up opportunities for empirical research to shed light on aspects of autonomy as a lived experience, alongside its facilitating factors and barriers. Some understandings of autonomy imply knowing more about the inner workings of human autonomy and undermine our ability to exercise it (Beever and Morar, 2016). In contrast, a pragmatist account of contextualized autonomy rejects the belief that learning more about what causes and influences attitudes and behaviors explains away autonomy because our ability to self-govern is supported by such knowledge (Racine, 2005; Racine and Dubljević, 2016; 2017). As we will see below in the next section of this paper, the understanding of different component-abilities of autonomy can be enriched by empirical research that informs us on experiential dimensions of autonomy.

A proof of concept for synergetic enrichment

According to a pragmatist account of autonomy—and of ethical concepts more generally (Racine, 2017; Racine et al., 2017c; Racine et al., 2019)—the concept of autonomy (or of one of its component-abilities) is descriptively and normatively valuable and meaningful insofar as it is genuinely helpful in fostering positive and enriching human experiences. More succinctly, as a concept, it should be an instrument that actually helps foster experiences of autonomy.Footnote 11 As an instrument, the concept can be refined and enriched based on knowledge that helps define the nature of autonomy as well as barriers and facilitators of its component-abilities (Racine and Dubljević, 2017).Footnote 12 Using this knowledge can be manifold and multifaceted; it has been described as a synergetic enrichment between a concept and the experience of what the concept designates (Racine, 2017): a more open-ended ethics and worldview is one which also leads to greater possibilities in terms of imagined possibilities (Alexander, 1993; Fesmire, 2003) and life experiences (Pekarsky, 1990). This odd-sounding instrumentalism where ethics concepts are not viewed only as ends but as means, as tools (Racine et al., 2019) reflects pragmatism’s invitation to unstiffen our ethical concepts (Inguaggiato et al., 2019; Martela, 2015) and consider the task of ethics to be a provider of tools to support a more meaningful life (Martela, 2017), including ethics concepts that are also open-ended and dynamic (Racine, 2017).

Following this approach, a refined understanding of autonomy and its component-abilities can lead to more autonomous decisions and actions, while experiencing and exercising autonomous actions and decisions can lead one to a richer understanding of the concept of autonomy (Racine, 2017). This bi-directional synergy can be illustrated by the practical aspects of autonomous decisions and actions that may involve, for example, fighting against beliefs about oneself or one’s understanding of autonomy, which undermine one’s confidence in the ability to undertake certain actions or projects, or resolve certain decisions. In these situations, views about our lived experiences shape the concepts we entertain while the concepts we entertain shape the kinds of experiences we are able to live (Mead, 1934). For example, becoming more autonomous may entail becoming conscious of views, entrenched behaviors and attitudes about gender, race, language, or ethnicity that imperil a person’s ability to be autonomous and taking a critical stance against such self-beliefs (Bandura, 1982; Bell, 1995). It may involve finding the courage to stand up and affirm oneself. It might also involve developing one’s ability to justify one’s decisions using arguments and principles. It could mean getting involved politically if causes impeding upon autonomous, individual and collective action require institutional or social changes in favor of liberating inherent potential(s) within individuals and communities (Cohan and Howlett, 2017).

Synergetic enrichment of component-abilities of autonomy

Synergetic enrichment involves a dialog between theory and practice. Continuing in the trend of enriching philosophical concepts with empirical research, a number of disciplines and fields of research (e.g., social work, critical disability studies, cognitive science and neuroscience) help shed light on more experiential and practical aspects of autonomy, even though they are not typically considered fundamental sources of theory on autonomy. However, they can (in a pragmatist sense) make autonomy more useful and impactful as an instrument by connecting it to real-world experiences. A comprehensive review of all disciplines and relevant bodies of knowledge is beyond the scope of this paper and its programmatic aims. Furthermore, the synergetic enrichment of all component-abilities of autonomy would require a book-length treatment. In this section, to illustrate synergetic enrichment, we focus on the three component-abilities of self-control, information, and authenticity. For each, we explore knowledge on (1) agential aspects of the component-ability; (2) contextual factors impacting the component-ability; (3) and agential and contextual aspects’ interaction. We also highlight some preliminary practical implications of this knowledge. We more readily pull from healthcare contexts because of the authors’ backgrounds and the dominance of the concept of autonomy in bioethics, but the ideas are applicable in other settings such as education and management.

Self-control

Self-control has been defined as “the ability to voluntarily regulate attention, emotion, and behavior in the service of more valued goals” (Galla and Duckworth, 2015). The relevance of research on self-control in the context of autonomy is increasingly acknowledged, and disciplinary bridges are being established (Levy, 2013). Indeed, self-control is an invaluable component of autonomous behavior since, without it, an agent is limited to reacting impulsively, without taking long-term goals and values into account. In fact, individuals with high levels of self-control are commonly considered better at carrying out self-imposed tasks, while those with lower levels of self-control experience challenges in undertaking and realizing valued actions, notably those that require self-discipline (e.g., exercising, dieting, cessation of smoking) (Tangney et al., 2008).

Agent-related factors

The ability to delay gratification as a child has a strong impact on one’s future life (Casey et al., 2011). It can predict “psychological, cognitive, health and academic later-life outcomes,” (Murray et al., 2018) and so forms an important aspect of the component-ability of self-control. Delaying gratification is closely linked to the ability of self-control, in the sense that it requires the capacity to shift attention, control one’s thoughts, and resist temptations in order to reach long-term goals. Improving one’s ability to delay gratification facilitates one’s autonomy via the self-control component-ability. Murray et al. (2018) have shown that this might indeed be possible by using the so-called “attention training technique” in children since it improves attentional flexibility. Resisting temptations like those in a delay gratification task is a relatively stable personality trait. Thus, knowledge on the possibility of being able to influence one’s own or one’s child’s ability to delay gratification (and thereby self-control) can have lasting, positive long-term effects.

Furthermore, prosocial behavior appears to require self-control in order to override one’s own selfish impulses (Dewall et al., 2008). Particularly, how much self-control prosocial behavior requires is dependent on the agent’s moral values, or conversely their feelings of power (Joosten et al., 2015). Individuals with a strong moral identity, or those with internalized moral values do not need to exert (as high a level of) active self-control in order to behave prosocially (Joosten et al., 2015). In contrast, agents with lesser feelings of power are more likely of acting antisocially (Keltner et al., 2003). This shows that exercising self-control is not equally demanding for everyone but rather dependent on intrinsic, agent-related factors.

Neuroscience research has also shed light on individual factors that influence self-control. The activity of the frontostriatal circuitry (in the prefrontal cortex) is predictive of an individual’s ability to resist temptations (Casey et al., 2011). Accordingly, Hänggi et al. (2016) call for “interventions aiming at strengthening frontostriatal connectivity to strengthen self-controlled behavior.” In the context of addiction, Tang et al. (2015) found mindfulness meditation training to have a positive impact on those brain regions involved in self-control. Sleep has similar effects on brain activity; sleep-deprivation leads to reduced brain activity in the prefrontal cortex (Pilcher et al., 2015), suggesting a decrease in self-control abilities (Christian and Ellis, 2011). Some argue that healthy sleep habits might restore internal resources for self-control and are predictors for good self-control abilities (Hagger, 2014; Pilcher et al., 2015). Consequently, knowledge about factors influencing autonomy, specifically self-control, can empower agents by revealing ways they might improve their own ability for self-control.

Context-related factors

Likewise, numerous studies have explored how contextual factors can increase or decrease self-control. For example, adhering to a diet typically involves a great amount of self-control, whereas low self-control is associated with more unhealthy food choices (Salmon et al., 2014). However, changing one’s context by making explicit a social norm that describes healthy food choices as common increases healthy food choices in individuals with low self-control (Salmon et al., 2014). This shows that it is possible to supplement an agent’s self-control by a making use of a nudge (e.g., displaying a social norm), which acts upon the context. Similarly, research on the effects of beliefs in free will has shown that deterministic beliefs lead to a reduction in intentional inhibition, this constituting an important part of self-control (Rigoni et al., 2012). Here, a reduction in intentional inhibition emphasizes how context-related factors, such as inducing deterministic beliefs, can actually decrease self-control.

Another contextual factor that can facilitate self-control is social support (Pilcher and Bryant, 2016). Pilcher and Bryant (2016) argue that self-control can be diminished by stress, but that social support is able to reduce stress, thereby constituting a possible, inadvertent resource for self-control. Moreover, parenting as well as parental economic standings, can influence individuals’ capacities for self-control (Lee et al., 2013). In the context of computer or smartphone interfaces, auto-play functions of video platforms and push notifications seduce individuals to spend, for example, more time on watching videos than intended. Downloading apps that block distracting websites for chosen amounts of time could facilitate self-control by countering these seductive measures (Racine et al., 2017d).

Interactions between agents and contexts

Agents change context-related factors, and inversely, context changes agent-related factors. Accordingly, Duckworth et al. (2016) propose situational strategies for changing a given context before it becomes demanding of one’s self-control. These strategies do not directly rely on intrapsychic strategies; rather, the authors here argue that employing situational strategies is more effective (Duckworth et al., 2016). One example is going to a library to study. In doing so, the agent does not have to rely on their own intrapsychic abilities to self-control by omitting distractions in their environment that would be needed in other contexts (like a noisy dorm room) (Duckworth et al., 2016), but rather exercises self-control by avoiding an otherwise more demanding situation.

Implications

A better understanding of agent and context-related factors impacting self-control has meaningful implications for ethics theory and practice related to autonomy. The approach preconized by contextualized autonomy empowers individuals by advancing knowledge on the components of autonomy such as self-control, and in turn constitutes the first step in overcoming obstacles by using manifold strategies. Some strategies can be quite simple, such as avoiding asking patients or caregivers to undertake important decisions while being sleep-deprived. Others are exploring how digital technology (e.g., mobile applications) can support users’ ability for self-control in realizing desired goals in a variety of different domains (e.g., spending habits, nutrition, habit control, moral reasoning) (Racine et al., 2017d).

Information

Abilities related to information, in both the ability to understand the meaning of a situation, as well as the ability to use that understanding to gather meaningful options, contribute to autonomous decisions and behaviors. This aspect of ethical decision-making has been extensively investigated in health care given the stakes at hand and, accordingly, we pull from this literature for the synergetic enrichment of this component-ability.

The informed consent process is often regarded as supporting (autonomous) decision-making (Benbassat et al., 1998; Ende et al., 1989; Nease and Brooks, 1995; Zizzo et al., 2017). Making an informed decision (as an aspect of autonomous behavior) has been clearly upheld in North American court decisions (following the doctrine of informed consent), such that it is sometimes held to be congruent with autonomy (Roy et al., 1994). Provision of accurate information is perhaps such an extensively discussed aspect of autonomy (e.g., in the context of health ethics), both because it is an important concept and because it is a more easily documented aspect of autonomy through informed consent forms. However, to fully grasp the component-ability of information and understanding in relation to autonomy, we need to move beyond a focus on sharing information on the risks and benefits of given therapeutic options. Ethical understandings of autonomy (and the importance of information therein) have been evolving partly in isolation from a much broader literature offering important insights on human information seeking and processing. We discuss some of these important insights below.

Agent-related factors

The ability to understand and process information has been the focus of research in fields such as contemporary cognitive psychology (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979). Research in this domain describes, among others, the interplay between context and simple cognitive processes (like heuristics) that can influence, positively or negatively, how information is understood or taken up, and by extension, explain how biased decisions are made. Within this scholarship, the “framing effect” is an example of a cognitive bias that describes how “alternative descriptions of a decision or problem often give rise to different preferences contrary to the principle of invariance that underlies a rational theory of choice” (Tversky and Kahneman, 1986). The framing effect, which refers to the manner in which information is presented (either positively or negatively framed) will influence the choice one makes, revealing the unboundedness of autonomy and challenging assumptions about rationality. For example, applying Walker’s (2009) rationalistic account of autonomy leads to a situation where every decision affected by a framing effect could be potentially considered irrational since it fails to apply logical or statistical rules. Another example is the anchor effect that describes how agents are unconsciously influenced in their judgment by the first piece of information (“anchor”) given before being asked to make a judgment. Agents may unconsciously orient their evaluation or decisions towards an anchor that might actually be irrelevant to the task at hand (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974). Similar ideas about cognitive biases have been taken up in the field of health communications (Paek et al., 2011) to examine how nutritional information is evaluated based on the presence or absence of anchor points (Paek et al., 2011); or how disease risk or prognoses may be communicated (Senay and Kaphingst, 2009). The latter topic has been deeply explored in the field of medicine in relation to biases associated with errors of diagnosis (Croskerry, 2003).

Following a pragmatist account of contextualized autonomy, the notion that the agent has autonomy is not threatened by knowledge about biases. The first-person experience of being able to choose autonomously cannot simply be dismissed by third-person perspectives of scientific research (Racine, 2017; Racine and Dubljević, 2017). The ability of autonomy might be diminished by cognitive bias, but autonomy’s existence and value in general is not necessarily eradicated by these findings (Racine, 2017; Racine and Dubljević, 2016). Enriching the concept of autonomy with this kind of knowledge only predisposes us to a higher level of awareness about potential biases manifest in such situations, resulting in an ability to detect contextual influences, thus enabling agents to be more careful and deliberate in their choices.

Context-related factors

Different contextual factors can influence how agents take up and understand information and make autonomous decisions. For instance, individuals with impaired cognitive or intellectual abilities may require support in order to assess information about options or decisions. For example, supporting autonomy of individuals with cognitive impairments in the context of health-related decisions (e.g., shared decision-making) could require physicians to develop deeper rapport with their patients and work with them to evaluate personal values and preferences (Young and Colpaert, 2009). Shared decision-making models have been defined as “an approach where clinicians and patients share the best available evidence when faced with the task of making decisions, and where patients are supported to consider options, to achieve informed preferences” (Elwyn et al., 2010). These models are built on the premise that autonomy can be supported in the context of trusting relationships that honor informed preferences (King and Moulton, 2006). In this vein, supported decision-making tools and models of care have been in development to engage children and adults (Hawley et al., 2017; Joseph-Williams et al., 2017; Montreuil et al., 2020) in health care decisions to increase autonomy. Nonetheless, factors such as patient-physician relationships, patients’ desires for involvement, and congruence between physicians and patients’ understandings of “involvement in decision-making” may vary and influence the extent to which decisions are shared (Robinson and Thomson, 2001).

Interactions between agents and contexts

Environments that facilitate the reciprocal exchange of information through communication methods that enhance and support an agent’s ability to understand information provide that agent opportunities to communicate preferences, values and choices. For example, Celia Fisher’s “goodness-of-fit ethic[s]” (2003) provides a framework for considering information exchange between health and social services providers with individuals that have cognitive impairments in the context of health decision-making. Through this lens, the interaction between agent and context can be examined for its contributions in facilitating an agent’s ability to engage and understand information that concerns decisions reflecting hopes, values, and ideas for one’s well-being while avoiding over-protectionist attributions of vulnerability.

Implications

As we have noted, autonomy in ethics (and especially in bioethics) is closely intertwined with informed consent. In medicine, full disclosure of all side effects seems to be a necessary condition for respecting autonomy. However, explaining all side effects risks meaning that they are more likely to happen (nocebo effects), which raises a dilemma between respect for autonomy and non-maleficence. Thus, some ethicists have proposed “contextualized informed consent” (Wells and Kaptchuk, 2012) that takes into account context when evaluating what and how to disclose information to the patient. This proposal exemplifies another practical implication of the concept of contextualized autonomy. Understanding mechanisms of information processing can help support autonomous decision-making. For instance, knowing the influence of certain cognitive biases can be helpful in overcoming them (Felsen and Reiner, 2011). As in the aforementioned, knowledge about the influence of the anchor effect on decisions (i.e., unconscious overweighing of a first piece of evidence) can lead to a careful reconsideration of one’s reasons for a certain choice, thus allowing one to avoid the influence of this effect on important decisions. Respect for autonomy can then lead to a need for educating health care practitioners and patients about those influences in order to empower them (Racine et al., 2017b).

Authenticity

Authenticity, or “the autonomy of personal preferences” (Sjöstrand and Juth, 2014), designates “the degree to which actions, including decisions, reflect the self: individuality, character, personal integrity, and coherence” (Ganzini and Lee, 1993). Inauthentic choices are those “that are out of character and inconsistent with past history, values, and decision-making style” (Ganzini and Lee, 1993), as well as inconsistent with one’s personality (Ganzini and Lee, 1993; Holm, 2001). Authenticity therefore refers not only to the present moment, but also to the notion of a temporal continuity with oneself, one’s narrative. Authenticity can be described by using a “self-discovery view” that focuses on being true to oneself as one is, or a “self-creation view” that focuses on striving to create oneself as the individual one wants to become (Singh, 2013).

Without authenticity, autonomy loses much interest and value. A prototypical autonomous decision is one that is authentic and that reflects intrinsic motivations, wanting to do something for its own sake and for self-fulfillment (Cortright et al., 2015; Taffoni et al., 2014), in contrast to extrinsic motivations that follow from social obedience or conformity (Deci et al., 1989; Ryan and Deci, 2000). Not all moderately autonomous actions need to be highly authentic in this sense, however it would be counter-intuitive to claim that a decision made autonomously does not resonate with one’s own desires, motivations, or preferences. Self-determination theory (reviewed above) has made a clear case about why autonomous (or at least highly autonomous) decisions are authentic and why such actions and decisions are crucial for individual growth and self-actualization (Ryan and Deci, 2000; Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Relatedly, the model of Informed Decision-Making (Bailey et al., 2013; Bekker et al., 2003) aims to empower individuals to make decisions concordant with their values. This focus on authenticity and concordance of one’s own values has been discussed rather fruitfully in the context of clinical decision-making and treatment-seeking (Bailey et al., 2013; Bekker et al., 2003; Singh, 2013). Importantly, not all intrinsic motivations are authentic and not all extrinsic motivations are inauthentic. Introjected regulation represents a motivation driven by an intrinsic desire to please or to comply with an internalized pressure (e.g., shame, guilt, worry). Identified and integrated regulations represents forms of motivation where a “person consciously values what she or he is doing and, when integrated, that valuing is deeply assimilated and fitting holistically with the person’s values” (Ryan and Ryan, 2019).

Agent-related factors

Several agent-related factors are potentially associated with authenticity and motivation in decision-making and in undertaking actions. For example, the influence of intrinsic motivation can impact people differently based on age (Taffoni et al., 2014) or sex (Cortright et al., 2015), although others found no effect for sex in younger age groups (Garon-Carrier et al., 2016). Some argue that authenticity might be threatened in the contexts of (develop)mental or cognitive health conditions and/or their treatments. However, these arguments have been challenged in a number of studies, including in an examination of perspectives on authenticity among children who receive psychopharmaceutical treatment for childhood ADHD (Singh, 2013), as well as opioid treatment use and its refusal (Ganzini and Lee, 1993). Some patients with anorexia perceive recovery as a threat to their true selves, in contrast to others who perceive anorexia itself as a threat to their authenticity (Sjöstrand and Juth, 2014). In the case of dementia, concerns have been raised about psychological continuity and authenticity (Holm, 2001). However, as Holm aptly illustrates, cognitive impairment, even to the point of losing legal ability to consent to medical care or research, does not mean that all authenticity is lost (Johansson et al., 2011). Holm argues when considering decisional competence, authenticity, which is not all or nothing, forms but one of the key components for evaluation.

Context-related factors

Context-related factors can also affect authenticity and intrinsic motivation. Although intrinsic motivation is (by definition) internal, it can be fostered by outside forces, something that a lot of philosophy underlying education studies (reviewed above) implies (Cortright et al., 2015; Garon-Carrier et al., 2016). This approach demonstrates that authentic motivation is not static or entirely inner-driven but can also be contextual. Not only can relationships with others affect intrinsic motivations, but also broader cultures such as work culture (Janus, 2014). External factors such as coercion or lack of information can be barriers to authentic decision-making in healthcare (Ganzini and Lee, 1993). Financial factors can also be a threat to intrinsic motivation as they might serve as an external motivation that overshadows intrinsic motivation and therefore authenticity of the choice, for example, to participate in research (Promberger and Marteau, 2013). The strength of this overshadowing effect, however, may vary by context (Promberger and Marteau, 2013). Importantly, financial incentives should be “perceived as confirming the individual’s autonomy rather than controlling his or her behavior,” otherwise they may indeed lead to feelings of inauthenticity. External factors can also support authenticity by addressing authentic concerns (Ganzini and Lee, 1993).

Interactions between agents and contexts

Interactions between agent-related and context-related factors are important for authenticity. For instance, when considering notions of sex and gender, terms that are sometimes used interchangeably, it may be difficult to disentangle agent and context. Sex is a biological aspect and gender inherently a social construct referring to self-perceptions, behaviors and other attributes along a spectrum of femininity and masculinity, therefore it may not be so simple to examine sex differences to understand differences in intrinsic motivation (Cortright et al., 2015). These must be understood in the context of gender representations as well (Watt et al., 2012). Anthropologist Charles Lindholm (2008) links the concept of authenticity to urban modernity and specifically the work of Rousseau. Stressing the historical particularity of the concept of authenticity suggests that there may be differences across time and space with respect to how people define authenticity and how much they value it. Authenticity is both individual and collective (Lindholm, 2008), so an authentic decision is not necessarily one that is culture-free. Authenticity can involve being true to one’s cultural values as well as one’s own.

Implications

Authenticity reflects an ability to exercise autonomy in order to actualize deeply held values, preferences, and identities. Issues about decision-making capacities and autonomy of patients are often voiced when patients disagree with commonly accepted clinical opinions (Ganzini and Lee, 1993; Holm, 2001; Sjöstrand and Juth, 2014). Communities struggle to determine when these challenges are warranted and when physicians should challenge them. These challenges do not rest on the argument that the patient does not “have” autonomy, but that concern for well-being or beneficence may be more important than empowering an autonomous decision (Sjöstrand and Juth, 2014; van Willigenburg and Delaere, 2005). Different subcomponents of autonomy could be at stake such that physicians could be favoring information while the patients could be privileging authenticity. This issue has been discussed in the context of advanced directives in which authenticity stands in tension with notions of information and voluntariness (self-governance) (van Willigenburg and Delaere, 2005); whereas for a contrasting view, see Holm (2001). Granting that prototypical autonomous actions need to be authentic to some extent, it is important to realize that autonomy is valued insofar as it allows individuals to live experiences that they consider worth living and in ways that they wish, experiences consistent with their values. Appreciating how profound the dimension of authenticity is for autonomous decisions makes us understand why cases that involve different values deeply embedded in world views and identities (e.g., debates over blood transfusions, mastectomies and chest reconstructions, sex reassignment surgeries, and cochlear implants) often represent some of the most challenging situations for clinicians and for discussions on the nature and extent of autonomy.

Conclusion

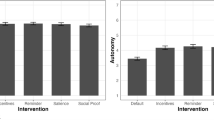

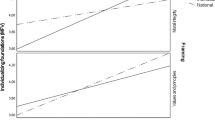

Autonomy is one of the highest esteemed values in many societies and communities. Its importance has been recognized in constitutional law and ethical principles, such as respect for patient autonomy in healthcare, legal, and political settings. Here, we have noted that there are intermingled debates on the nature of autonomy (what it is) and why it is valued (e.g., its role in ethics, its functions) and how these issues point back to more descriptive and normative concerns. Following the theoretical and methodological insights offered by pragmatism, we adopted an instrumentalist strategy to gather insights about autonomy and push forward the intent of more clearly making autonomy a tool for moral agents. We described a pragmatist account of contextualized autonomy that seizes autonomy as a broadly shared value based notably on recent findings in positive psychology and that recognizes, along with relational theories, that it is not singular in nature nor universally experienced in the same way. Moreover, the pragmatist account put forward aligns with relational accounts that stress that autonomy is situated and forged in webs of relationships in contrast to the rather disembodied and abstract nature of individual accounts of autonomy. A pragmatist account of contextualized autonomy also integrates a strong agential perspective by describing autonomy as a complex ability composed of multiple component-abilities that can be facilitated or hindered; exercised or neglected. This account enriches the ethics concept of autonomy through a synergistic process that draws on interdisciplinary resources to determine the functions of autonomy and its subcomponents in order to evaluate it. The strategy of synergetic enrichment proposed avoids some traditional metaphysical issues caused by spurious dualisms (e.g., theory versus experience); accordingly, a pragmatist account of contextualized autonomy is not “threatened” by knowledge arising from empirical sciences that reveals how decisions may, for example, be unconsciously influenced by external factors. Rather, we argued how understandings of autonomous behavior and decisions can be enriched by a range of disciplines often neglected in more philosophical discussions sensu stricto on autonomy. As a result, we demonstrate that empirical disciplines can empower autonomous agents by promoting greater self-understanding of personal agency, as well as foster a better appreciation of the contextual forces that shape individual decisions. We hope that the views shared in this programmatic paper encourage further work on the methods of instrumentalist analysis and synergetic enrichment, as well as more detailed exploration of autonomy in concrete scholarly and practical contexts. We hope that rich interdisciplinary dialog on autonomy and agency, and the seemingly insurmountable conceptual and disciplinary barriers, give way to revising concepts and practices inspired by strong commitments to scientific and experiential knowledge on agency. Looking forward, we encourage the development of multi-dimensional scales that measure autonomy as a genuine ethics construct and that interventions be assessed for their impact on the autonomy of agents in practice.

Data availability