Abstract

Adolescence is frequently seen as a troubled age. In many Western societies this is also a time of sharp religious decline. The question arises as to what extent religious faith and practice could help teenagers cope with their distress, especially when religion fades away in secularized environments and stops being a common coping resource. A study was conducted in South-East Spain (N = 531) to assess coping styles—religious and secular—and how they are related to other variables. The outcomes suggest that religious coping has become a minor choice. It correlates positively with age and is mixed with secular coping strategies. Secularization implies a confidence lost in religious means and the search for alternative coping strategies. This study reveals that religious coping works best when linked to religious communities and in combination with other non-religious strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introductory remark

Two perceptions about adolescents and young generations in Western countries are widely assumed nowadays. They are much more vulnerable than previous generations to psychological and social pathologies—like anxiety, depression and distress—and their religiosity levels are lower than those observed in similar cohorts in previous decades. It is too hasty to deduce that both trends are related. Indeed, many variables converge in the social context in which adolescents live and grow. In any case, it is worth asking, whether the religious dimension still plays a positive and healthy role in their development, considering that this is by no means the only helping or positive factor in that life stage, facing many trials and threatening trouble.

A good place to start is exploring the field of “Religious coping”. This is a wide research program that offers a many published studies, discussions and assessments, with new research papers available every year and engrossing a quite broad repertoire that is difficult to render in systematic terms. The common trait of all this research is their attempt to assess to what extent religion and spirituality help to cope with life struggles and crisis.

The present research connects the current literature to new empirical survey, exploring with an extensive questionnaire to what extent Spanish adolescents resort to religious coping strategies; how they perceive that available resource; and how does it relate to other possible coping strategies. This study tries first to assess the outcomes from published studies relevant for this specific realm, and then introduces the survey we proposed and the performed analysis from the obtained data. In a last step, these analyses will offer some new information and nuances to the existing literature and to open new hypothetic application areas.

Literature review

Standard studies on religious coping usually show how measures of religious adaptation are related to indicators of health and well-being in individuals and groups, to their self-esteem and personal satisfaction levels. Such studies are used subsequently by health researchers to develop interventions to assist patients suffering several diseases and problems. In many studies in that field, religion appears as a factor that can promote self-control, influences how projects and goals are selected and enhanced; facilitates attention to regulate situations; and determines and promotes competences in a set of self-regulating behaviors (Pargament et al., 2000; McCullong and Willoughby, 2009).

Kenneth Pargament (1997) is probably the pioneer and better-known scholar in the field of religious coping. He described religion in terms of a search for meaning related to the sacred, and found that it becomes an integral part of meaning systems for many people, a specific approach from which to understand the world, the interactions with others and a global reference frame to order and interpret human events. The coping capacity of religion seems linked to its ability to provide meaning and purpose, especially in more stressful and difficult life conditions (see for an extensive review on meaning: Park, 2010). Other studies point out that belief in God can become an internal interlocutor to motivate personal behaviors through a process similar to what happens in social relationships (Luhrmann, 2020). Thus, people with high levels of religiosity can see God as a safe haven, a figure in which strong attachment feelings converge, close to those developed with parents, an affectionate God who is sensitive to the needs of believers, and involved in human affairs. All this provides individuals with a sense of intimacy and trust with God, offering comfort in adverse situations. However, those who have increased their awareness of sin and sinfulness often accompanied by feelings of moral inadequacy and personal deprivation, may present lower levels of life satisfaction and lower self-esteem (Jung, 2015). According to Hisham and Pargament (2015) many people in all religious traditions rely on spiritual teachings, beliefs and practices to face challenges, transform perspectives and attain comfort. Everything points to the positive aspects of prayer to control anxiety and depression, develop empathy and improve cognitive and intellectual functioning.

Religious coping as a research program has known several revisions and has raised doubts and some skepticism concerning its theoretical and its methodological approach (Folkman and Moskowitz, 2004; Gall and Guirguis-Younger, 2013). The present research connects with a sound tradition and attempts to contribute to its maturity and progress.

Many studies of adolescents have tried to apply to that developmental stage that research program to better know to what extent these religious coping strategies are applied in those life levels and their effectiveness. Considering the published evidence regarding religious coping in adolescents, the relevant literature, will be first systematically reviewed, looking for an answer to our query. In all 76 published studies (until 2016) analyze strategies of religious coping to evaluate its effectiveness addressing different juvenile problems and psychopathologies, such as: stress/depression, consumption of abusive substances, and anorexia/bulimia.

The review has found that religious beliefs and practices had a modest but positive association with the psychological well-being in these young cohorts in 70% of the selected articles. Regarding issues related to mental health, like stress and depression, the studies indicated that the impact of negative events in youths’ lives was reduced in those who reported a high level of positive religious coping. On the contrary, abandonment of religious practices, like prayer or meditation, showed a growing negative effect (Carpenter et al., 2012; Pargament et al., 2003). The evidence indicates that adolescents who consider religion important for their lives, resort to it as a guide in decision-making (Rose et al., 2014). Other authors stated that religious assistance to adolescents in a mild depressive situation helps to cope with it, although it is uncertain whether that effect depends just or mostly on the religious factor (Carleton et al., 2008).

Some studies have addressed the relationship between stress and religion. In general, the available research revealed a moderate positive association between religious attendance or participation and reduced anxiety in middle adolescence, especially for those grown up in societies in which God is more frequently invoked, becoming an appropriate and acceptable practice for most social segments (Jung, 2015; Peterman et al., 2014). The negative results obtained in some cases result from: voluntary abandonment of religious practices; perceived conflict in personal relationships with God and others; doubts and confusion when trying to respond to problems related to stress (Carpenter et al., 2012; Pargament et al., 2003). Some ambiguity in the collected results may be the consequence of too many cross-sectional designs in research. Experts in this area invited to conduct more prospective studies to clarify the causal and interpretative ambiguities among available data (Jung, 2015; Hisham and Pargament, 2015).

On a different level, concerning the influence of religiosity on toxic substances consumption, two approaches will be outlined. The first one argues for an existentialist view that explains consumption of psychoactive substances or substance abuse in young people as a result of meaninglessness of life and existential void (Wilchek-Aviad and Ne’eman-Haviv, 2015). The second approach focuses on studies that highlight the presence of vital stress as a factor in risky behavior (Wills et al., 2003). By observing the consistency of buffering effects against substance abuse in adolescents, possible protective resources can be conceived to counteract such stressors (Wills et al., 2003). In that sense, the reviewed research reveals how spirituality or religiosity predicts positive changes in behavior over time. Religiosity has a clear attenuation effect against those risky factors among participants (Duque and Giancola, 2013; Desrosiers et al., 2011; Rostosky et al., 2008; Bjarnason et al., 2005; Mason and Windle, 2002; Brown et al., 2001). Furthermore, the data suggest in general a prosocial attitude correlated with religion.

A different critical issue, equally important in adolescent development, is related to eating disorders, and here religious coping also appears as relevant. The studies carried out to date show that religious and spiritual variables play an important sociocultural influence in such pathological attitudes (Castellini et al., 2014; Inman et al., 2014). Analyzing a non-clinical sample with subjects at risk associated with their dissatisfaction with, or distortion of their body image, and belonging to different religions groups, it was observed how an increase in levels of religiosity prevents the incidence of such developmental disorders (Latzer et al., 2015). Positive religious adaptation has been shown to be associated with an improvement in psychological adjustment, reduced anxiety, and higher life quality for people who suffer chronic diseases or who have suffered some trauma in interpersonal relationships (Pirutinsky et al., 2012), producing better results in mental and physical health (Carpenter et al., 2012). On the contrary, these same studies agree that higher rates of negative religious adaptation are significantly related to lower levels of self-esteem, an important risk factor linked to eating disorders. Consequently, religious or spiritual factors could exacerbate or mitigate symptoms depending on the individual’s coping style (Rider et al., 2014). A more accurate approach to this issue is offered by studies on religious/spiritual struggles. This concept describes tensions, doubts and internal or external trials and conflicts around one’s own religious beliefs (Exline, 2013; Exline et al. 2014). It is expected from this view that those struggles clearly influence the coping style, the meaning-making process, and could determine the outcomes from religious beliefs and practices in critical circumstances (Exline et al., 2011).

As can be seen from this review, religious coping in adolescents covers a broad spectrum ranging from issues related to personal health and well-being, to means to managing threats and dangers of different kinds. The gathered studies should be complemented by more recent entries that enrich the already abundant list. For instance, recent years have seen new studies on religious coping before depression and anxiety in students; and more recently several studies have focused specifically on coping before Covid-19 pandemic and its threatening effects (Francis et al., 2019; Thomas and Barbato, 2020). The general impression is that religious coping covers a broad field comprising many positive effects on physical and psychological health, and raising several questions regarding its effectiveness and styles.

In general, the reviewed studies reveal a positive religious effect on several problems and risks present in adolescent development. However, such an effect often depends on the coping and religious style, or religious struggling. The outcomes reviewed may be related to cultural environments. Sometimes the evidence is tainted with other uncontrolled factors. This perception of the current research discourages an overall and simple theory, and invites further the research looking for new evidence to clarify aspects that could help to develop a more nuanced view about the supposed benefits of religion in youth development.

After this introductory background, the present study will examine religious coping in a sample of Spanish adolescents. The research tries to mitigate the scarcity of studies on religious coping in younger Spanish populations (an exception being Pérez and Cánovas, 2002). A growing concern for the quoted problems and the lack of more focused studies justify the present investigation and its attempt to fill the gaps, and to assess the extent that renders religious coping a valid coping strategy in very secularized environments, where alternative coping strategies are available in this life stage.

Based on previous studies, three working hypotheses are advanced:

-

Religious coping moderates the impact of negative life events on adolescents and young people through cognitive and attitudinal mechanisms.

-

Adolescents who resort to religious coping in times of crisis also use secular coping methods when struggling with life difficulties.

-

The different degrees of religious coping are related to adolescent development levels.

An empirical study on religious coping in Spanish teenagers

A quantitative research study was developed to assess to what extent religious coping is still an available strategy for Spanish teenagers in a very secularized milieu, the possible coping styles, and the perceived efficacy of such strategy. The research measures the extent of religious aspects in adolescence, and uses a person-centered approach to illustrate and gather information about different levels of religious adaptation. Those data were used to see to what extent religious beliefs and behaviors could counteract the adverse situations that afflict an adolescent generation quite far from religious practices and—to some extent—from the experience of faith. as a valid mechanism to process emotions or as an instance of consolation in the face of big life struggles.

Before giving further steps, a note on religious levels of Spanish adolescents and youths will help to better contextualize the proposed research. The most recent data come from the December 2020 CIS Barometro, an official polling agencyFootnote 1. Those in the cohort between 18 and 24 years that declare to be “practicing Catholic” amount to a modest 10.2%, compared with 20.1% of total Spanish sample. “Not-practicing catholic” are 22.4% among the younger teenagers, while in the whole sample of teenagers it is 41.6%. Then, adding the categories of “agnostics”, “indifferent” and “atheists”, we get 61.1% for the youngest cohort, and 34.4 for the whole sample. However, oddly, the levels of weekly attendance to religious services are similar in both cohorts (around 13%).

The same polling agency data from ten years earlier, i.e., December 2010, shows that the youngest cohort self-describing as Catholics—practicing or not—were 54.9% and 73.6% in the entire sample; 39.8% non-believers plus atheists, among the youngest, and 22.5% for the total. The weekly assistance to a religious service was 4.5% for the younger, and 13.2% for the total. We have a confirmation for the former series from Fundación SM, a Catholic research institute; in its 2010 report shows that 53.5% of a youth cohort confess to be Catholics, while 42.4% consider themselves as no-religious; weekly attendance to religious services were 9.1%, probably a rather optimistic figure (González-Anleo et al., 2010, pp. 182–199). Alternative data come from Pew Research Center, an American Polling Agency; its study Being Christian in Western Europe, from May 2018Footnote 2, reveals that 26% of Spanish parents without religious affiliation educate their children in the Christian faith and values.

In any case, these figures clearly point to a sharp decline in religious indicators in most adolescent and youth, when comparing data in the last 10 years. Spanish adolescents are becoming the less religious cohort among the Spanish population.

Method and data

In order to collect new data for a quantitative study on adolescents’ coping strategies, an instrument has been designed, and a set of high schools was selected, public and Catholic private, located in the South-East Spanish regions of Murcia and Valencia. The instrument consists of an ad hoc questionnaire on religious coping built after a standardized scale, the RCOPE questionnaire designed by Kenneth Pargament (Pargament et al., 2000), and adapted to Spanish adolescents. This instrument has been previously applied and tested by Pargament and his collaborators (Pargament et al., 2011), and in several other published research on religious coping among the youth (Carpenter et al., 2012; Talik, 2013; Lord et al., 2015). The present version contains a reduced number of items (60 in total from the 105 original) to suit that sample and to avoid redundancies.

This Spanish adapted RCOPE version keeps many sub-scales related to different coping strategies and religious styles. Here are the summary of scales and their distribution in number of items:

Negative and struggling coping strategies

-

The stressor is seen as a divine punishment: 3 items

-

Self-management: coping without God’s help (friends, alcohol, drugs, internet, television, self-help, insulation): 14 items.

-

The stressor is attributed to the devil: 1 item

-

Passive waiting, religious postponement to solve problems: 1 item

-

Spiritual discontent, anger in the relationship between God and individual: 4 items

-

Reassessment of God’s power and influence in the stressful situation: 4 items

Positive coping strategies

-

Religion transforms one’s own life, providing new direction: 7 items

-

Voluntary Surrender, yielding to God’s control to address the problems: 9 items

-

Advocate for divine intercession or miracles: 6 items

-

Spiritual support: ask for and give support to others: 6 items

-

Active practicing: 5 items

A Likert scale of 4 levels has been used in this instrument: 1 = Never, not at all; 2 = Occasionally; 3 = on several occasions; 4 = often or very often.

Participants

Prior to undertaking the full survey, a sample was administered to 20 students to assess their understanding and the items fitting. It was distributed to students between 16 and 20 years (mid- and late adolescents) in several high schools, public (300) and private-Catholic (231) in the regions of Murcia and Valencia. A total of 531 were selected after rejecting 20.

The sample’s variety allows for a broad view of the intended target; indeed, the students who answered the questionnaire come from different social and cultural backgrounds and represent a variety of educational curricula.

The questionnaires have been distributed to the students in the classrooms during the academic year 2014–2015 and in lesson time, in the presence of teachers or tutors. In every case the privacy and ethical protocols have been strictly observed; the participants and involved parties have been informed about the nature and scope of the research; and the needed permissions were asked and obtained from the concerned responsible.

Results

a. Descriptive statistics

The sample demographics shows a quite representative distribution: 46.4% was male students and the average age was 17.3 (S.D. = 2.0).

Regarding religious behavior and self-assessment, three items revealed low commitment levels, as could be expected from a secularized cultural environment: weekly religious attendance scores 1.47 (the scale has 4 levels); daily prayer 1.57; and the assessment as a religious person gives 1.82 in the same scale. Possibly some gap persists between religious belief and practice, in the sense that could be described as “believing without much practicing”, adding some nuance and complexity to the well-known category coined by Grace Davie, “Believing without belonging (Davie, 1997; Tromp et al., 2020).

The means table revealed that most students did not resort to religious coping or look for alternative coping strategies in the presence of serious problems or suffering. Anticipating data from a factor analysis that will be later exposed, a factor gathering six related items (alpha = 0,725) describing absence of religious coping in this sample registers a rather high average: 2.75 (1–4) (“To fix my problems I leave God aside”; “I had my doubts about God’s power”; “I trust on my own strength without God’s help”…).

Preferred coping strategies are secular in their orientation: seeking help from friends (2.99); laughing about one’s own problems (2.77), isolation (2.34); and some resignation about positive consequences from bad moments. An item wording is quite revealing in this respect: “difficult situations helped me to grow and improve” (3.18). Religious coping is registered through a wide set composed of 11 related items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.910); in this case the recorded mean is quite low: 1.84, revealing the prevalence of secular over religious coping strategies in this sample

b. Analytical statistics

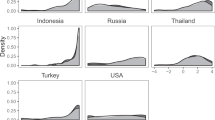

A first step consisted in reducing variables through factor analysis. This allowed the construct validity and reliability of the questionnaire administered to students to be measured; internal validity was measured with Cronbach’s alpha, which showed the internal consistency of a first factor including most items, and its validity as a test to measure the extent of religious coping in students. Appendix table 1 describes the results from the factor analysis with Varimax rotation and describes five reliable extracted factors.

The factor analysis was intended to assess what dimensions explain the variability of responses by adolescents to the questionnaire items, after reducing the many items into clusters. This analysis only detects a factor that includes 30 items with loadings over 0.4 (see the complete questionnaire in Supplementary Materials [The Supplementary Materials link is missing in the appendix]). The other four listed factors are composed by few items and hence they can be neglected. That first single factor explains 21.5% of the variance and indicates that religious coping affects 21.5% of the adolescents. The explanation percentage is high enough given the diffuse nature of what is being measured, which allows to state that the first factor provides a good test to measure of religious coping. That first factor has a Cronbach’s alpha = 0.944, which shows its high internal consistency. In addition, each of the other factors fail to explain each one >5% of the variance.

Analyzing the frequencies of the scores obtained by the test of religious coping it is clearly shown that the higher frequency arises around 1–2 scores, with an acceptable frequency in scores between 2 and 3, confirming that religious coping in adolescents maintains a low level.

A second step has produced a multivariate cluster analysis. It was intended to see how many groups can be separated by the questionnaire items. The result shows the presence of four groups or clusters, distributed as follows (514 valid, lost: 17):

-

1.

175 members

-

2.

237

-

3.

30

-

4.

72

The variance analysis done with these 4 groups depending on factor 1 shows that that factor separates perfectly the four groups, and shows that the groups order regarding their religious coping can be described as follows: 2 < 3 < 1 < 4; in other words, group 4 includes those students who resort more to religious coping; group 1 to some extent; and then the other two groups few or very little.

Next step produced a discriminant analysis aimed to obtain a minimal test that allows to get a measure of religious coping of adolescents by selecting a minimum number of items that discriminate the four groups with a high hitting percentage. Following this analysis of self-report items except for age and course, the following items appear as discriminant:

V61: Age

V14: I sought solace in God

V15: I trusted that God would be on my side

V2: To fix my problems leave aside God

V34: I prayed for others

V59: Seeking support I need in the Church

V16: I do what I can, and the rest I trust God

V35: I have wondered if God had abandoned me

V57: I pray at least once a day

V40: I have asked God to help me to help others

V31: I thought that my life is part of a great spiritual strength

V17: I tried to make a deal with God that He help me

V26: Some tough times have brought me closer to God

V10: I prayed to stop thinking about my problems

V63: Course (1st, 2nd Bachelor)

V39: I think that the solution to my problems is inside me and not on God

V56: I go to church or other religious service at least once a week

V46: I have some devotions—the Virgin, a saint—and call upon them when I need their help

With the information from these items, the percentage of correct reclassifications is 94%, which is the measure of reliability for this test. Furthermore, each group reclassifies well: 90.9% in group (1); 97% group (2); 100% of Group (3), and Group (4), 88.9%. It is therefore a fairly reliable test.

Now several tests with selected variables have been conducted looking for significant outcomes. First, age has been considered. It can be observed that group (1) is associated with students 16 years old. In addition, also those belonging to group (2) are associated with students 17 year old (group with less religious coping). This indicates that students from 17 to 19 years old know a crisis regarding religious coping, therefore young people move from moderate to low religious coping. Moreover, Group (3)—those over 20 years are associated with best religious coping, i.e., there is a recovery of such coping strategy, even overcoming the level registered by those belonging to 16 years old cohort.

Second, the item “I sought solace in God” has also been tested too. Based on the analyzed data, Group (4) has a significant frequency of high scores, for example, we see that from 45 high scores, 36 correspond to group (4). Accordingly, this group corresponds to those who more often are seeking solace in God. However, the figure from group (2) puts us in the opposite direction, those who never seek solace in God.

Third, regarding the variable on personal prayer for other people, group (4) is again associated with subjects who pray more often for others, since they gather 36 from the 72 scoring the highest level. Group (2) is related to adolescents with lowest scores.

Fourth, the item about “seeking support in the Church” has been tested. Group (4) gathers those who seek more support in the Church to face crisis. In the opposite extreme are those belonging to group (2). Looking at the figures, “finding support in the Church” often lacks frequency in this sample. It is a variable that makes the difference, those with more religious coping are seeking more support in the Church.

Regarding religious service attendance, a similar pattern arises: group (2) does not attend Mass or any other religious services once a week, corresponding with an absence of religious coping; group (4) assists on several occasions and group (1) on some occasion. These two groups would represent different levels of religious coping.

The last item to test is the one with the expression “I think that the solution to my problems lays inside me and not in God”. The results show that Group (2) gives an affirmative and decided answer to solving their problems by themselves. In group (4) scores are much lower, while group 1 would be more distributed, part of them would score in high, and other in low levels, revealing different coping strategies.

c. Results and formulated hypothesis

Now, coming back the three hypotheses formulated at the paper’s introduction, the first one stated the moderating effect of religious coping in life stressful events. Overall, the data in this study confirm that the minority cluster with higher religious levels in believing and practice, perceive the beneficial effects of their faith and prayer. Indeed groups (4) and (1)—that attend religious services on several occasions or at some time—present higher levels of religious coping and report a more positive adaptation to difficulties.

The second hypothesis foretells the entrenchment of religious and secular coping strategies. Indeed, our data points to a double coping strategy: adolescents who, in times of crisis, resort to religious coping can, in turn, apply secular coping methods. Our study highlights how often coping strategies are built on a personal search in which the peer group acquires relevance along with the avoidance tactics. The analyzed sample offers this evidence for groups (1) and (3). It is obvious that adolescents use different coping strategies in times of distress and that any stressful situation implies an exchange between person and his/her environment in which the individual develops. That exchange acquires varying forms according to the many factors involved and the events lived. In other words, it is pointless to try to isolate the religious or spiritual variable, which often is very entrenched with other circumstances, especially with one’s own relationships—including family—personality, past experiences, and expectations.

The third hypothesis pointed to a developmental dimension in religious coping. The data from the sample in Group (1), (2) and age range between 16 and 19, reflecting lower religious coping, match the theory describing faith stages according to Fowler and Dell (2004); these stages are predictable, invariable, sequential and occur in all individuals without exception. However, the data from this study reveal that from the age 20 on, a recovery of religious coping strategies takes place, associated with individuals in group (3), which indicates some progress in the process of personal autonomy and the development of self-identity characterized by a personal selection of one’s own values, convictions and beliefs. The progress is determined by the passage to an individual reflexive faith, able to build spaces of introversion in which the perception of God becomes more abstract.

Our research supports that each stage of adolescence is shaped by its own cognitive, social, psychological and behavioral changes, with late adolescence presenting a minor religious coping associated with the Group (2). In addition, the passage from a conventional faith to an individual and reflexive faith marks a recovery of religious coping strategies associated with the older Group (3), those moving beyond teen years. In this way verification of the third hypotheses raised in the investigation “different degrees of religious coping are related to stages of adolescent development”.

d. Other relevant results

Trust in God

Within the analysis group (4) includes adolescents who seek consolation in God, and trust that He will be on their side in difficult times, with scores 3 and 4 in the Likert scale. On the other hand, the group (2) places us in an opposite position in both situations: out of a total of 237 students belonging to this group, 185 never seek consolation in God and 172 of the total express distrust, have no experience of how God can fit in situations of crisis or life struggle.

In our analysis, the students of group (4) showed positive religious coping, their connection with the sacred led them to establish trusting relationships with God; the group (2) seems to express spiritual discontent or possibly a spiritual struggle. Maybe the personal and social situation in which those adolescents live could justify searching for faith in difficult moments, and probably they might experience at the same time help, hindrances and frustration, in their attempt to control very problematic situations. These are conditions and trials necessary to reach maturity and adulthood, and in such struggles—including those related to religious or spiritual beliefs—the role played by faith is undecided, and quite often can be perceived as useless or disappointing.

Looking for support in the Church

Belief strength, personal religious practices and religious motivation are factors that load religiosity with positive effects on the adolescents and the lives of youth. Despite this evidence, many teenagers avoid such support; indeed, the data from our study reveal that the search for support in the church is very low in the group (2)—the bigger in members. This trend probably reveals high distrust levels before ecclesiastical authority; or this segment considers many moral impositions too burdensome for their lives; or they fail to integrate the tension between faith and culture, or perhaps many of their beliefs are rather vague and indefinite, resulting from a superficial faith. Apparently, not a single factor justifies the observed distrust towards the church, rather a set of experiences seem to trigger such negative effects resulting in abandonment.

Prayer frequency

The data in our sample reveal that groups (1), (3) and (4) pray with more or less frequency, while group (2) could be associated with some of the current tendencies: atheist, agnostic, “no practitioner”, “religious without affiliation”, “spiritual but not religious” or “religious in a private way”. The choice in one way or another directly affects the individual; everybody can build an intimate relationship with divine figures and use means such as: prayer, or assistance to religious services as a source of empowerment in difficulties, or when all this fails, to resort to other alternatives.

Praying for others: solidarity

The group with the highest religious coping (4) of the study reveals this trend. Consequently, the three dimensions that converge in the process of religious coping: intra-personal, interpersonal and sound attachment relationships with the divine build spaces of spiritual connection with others. It is evident that other forms of prosociality and altruism happen in the secular world involving mechanisms such as learning, social / personal values, or emotion activation; all this points to a different design in which the spiritual dimension and cooperation with God are absent.

Looking for solution to problems in one’s own self

According to González-Anleo et al. (2010), a bulk of individualism and self-centeredness accompanies the identification and religious search of Spanish youths. Young people believe that it is possible to live religious faith individually, privately, without reference or any community; religious or spiritual beliefs and practices are thus disconnected from ecclesial institutions. Possibly group (2) in our survey represents the large group of adolescents and young people who perceive spirituality as positive behavior, relationships or feelings, but live it away from established religion. The tendency in those belonging to this group is related to the lowest religiosity levels in the whole study. However, spiritual experiences provided by the organizational and cultural religious contexts can help to strengthen and unite moral commitments in adolescents’ lives, with positive and constructive results in most cases.

When considering the collected literature and our own data, the main coping source for adolescents seems to move to interpersonal interactions. Indeed, new emergent religiosity is less related to group and more isolated from community life, far from social networks and resources that a spiritual community can provide to enforce adolescents’ development. Such provision includes activities of control, follow-up, normative regulation and establishment of personal goals that emerge in the interaction between a person and his/her environment.

Furthermore, to dispense with the community reference or the social network with which the individual shares religious or spiritual beliefs and practices entails a weakening in the available social capital (Good and Willoughby, 2006). This situation is reflected in our study: even though adolescence is a privileged period for exploration and commitment to religious or spiritual beliefs, most members in our sample—with the exception of group (4)—reveal moderate levels of religious disaffiliation in the groups (1) and (3) and indifference about any connection with the sacred in the group (2).

Discussion

The present investigation measured the extent of religious coping in Spanish adolescents. Based on these objectives, three hypotheses were formulated. as a basis to develop the present research. All three found significant statistical evidence. Furthermore, the collected data have allowed for a more nuanced view on how Spanish adolescents believe and organize their meaning systems to cope with distress, life risks and unexpected negative events.

The study demonstrated that religious coping is limited for Spanish adolescents immersed in a very secularized culture, despite the apparent benefits that such strategy reports in the available studies. Even such an instrumental view does not help to convince Spanish teenagers about religion’s utility. However, some nuances have been highlighted through the proposed analysis. First, religious coping changes along adolescent stages, reflecting broad and deep variations through that development, as those described by Fowler, Oser, and others (Fowler, 1981; Fowler and Dell, 2004; Oser and Gmünder, 1991). The passage from a conventional religious style to an individual/reflective faith could indicate a recovery of religious coping. Identifying patterns of coping strategies in adolescence could help religious communities to find out more fitting approaches to assist teenagers before stressful events.

The second important finding of this research is linked to the trust relationships that a segment of adolescents establishes with God to motivate their behavior and develop personal beliefs similar to those born from attachment feelings with their parents. In this sense, the highest religious levels and attendance at religious services by parents are reflective of religious values in adolescence. Disruptive events lived by family or in Church life bear as a consequence neglect and decline in the process of religious coping.

On the other hand, the characteristics of group (4), reporting highest levels of religious coping in this sample (4) reflect a more positive adaptation to difficulties than other groups; thus, the results suggest that religious coping expands the range of possibilities to deal with adversity through cognitive and attitudinal mechanisms over their non-religious peers.

The final research finding reveals the emergence of new models of religiosity with weakened institutional belonging in the current scenario. Sociologists of religion have tried in the last decades to better describe such a complex environment, giving rise to forms of “believing without belonging” (Davie, 1997; Tromp et al., 2020); “belonging without believing” (Mcintosh, 2015); and the many expressions of unaffiliated or loosely affiliated religiosity, comprising “believing without practicing” and unaffiliated spiritual beliefs and practices. As can be seen, the religious milieu becomes in in these modern times too complex to allow for a simple model connecting religiosity and coping. The church framework is clearly in decline and new models substitute traditional religious coping based on intra-personal, interpersonal and sound attachments with divinity. Instead, inner search or self-reliance is predominant. However, the study reveals that the highest levels of religious coping include institutional and personal religious commitment by adolescents. When the community link is absent, then religious/spiritual beliefs suffer a clear weakening, observable in the contrast between groups (4) and (2). Nevertheless, different coping strategies coexist and share in the adolescent repertoire, without excluding anyone or assuming an exclusive role. The context and circumstances help to decide which strategy could become more useful, and in many cases a “joint approach” between secular and religious means is the rule.

After presenting our research and its outcomes, it is convenient to summarize the problems associated with such a program. A general question regards the observed limits in religious coping research, as already mentioned. Broad studies and systematic reviews highlight those limits regarding measurement, nomenclature and effectiveness of studied coping strategies (Folkman and Moskowitz, 2004; Gall and Guirguis-Younger, 2013). Then, a related set of doubts arise regarding the adequacy of Pargament instrument RCOPE and its scales, a specific issue on measurement; indeed, several studies have shown their concerns regarding what is really measured and what is left out (Alma et al., 2003; Ahmadi, 2006; Kwilecki, 2004; Xu, 2016; Saarelainen, 2016). Moreover, a third source of criticism regards the probable confusion between religious and secular items in the most used scales, or the difficulty to distinguish between more religious and more secular strategies when both appear as deeply entrenched. This is the case, for instance, of items pointing to consolation and support in friends, or looking for community and company. The “entrenchment issue” looms indeed in all this program and makes a neat distinction between religious and secular coping styles difficult to discern.

The exposed research presents its own limits: this study is quite local and has resorted to a convenience sample. Furthermore, it is limited in time, and does not provide data on how religious coping in the surveyed adolescents would evolve in near future and in different situations. To that end, a long-term longitudinal study would be necessary. Furthermore, a relevant issue that needs to be studied in forthcoming research is the implementation of programs that encourage and test religious coping in educational settings, to assess their validity and application when trying to prevent and help to cope with the current anxieties and troubles many adolescents still have to tackle.

Concluding remarks: current relevance of religious coping for adolescence studies

The surveyed data provide psychologists, educators and religious pastors with more information and criteria to better know that difficult life stage and to deal with young people and their problems in a more focused way. A pending issue concerns the meaning and value of religious coping studies—in general—and our particular and localized research, inside a program that values empirical data and analysis inside a more interdisciplinary approach.

To our own view, at least Four important issues emerge: from the undertaken study that help for a better discernment in the scientific study of religion and offer insights for further development. The first one (1) regards the application range of these data. It is well-known to what extent religious coping has been used as a mean to show the positive side of religious faith, an argument to contrast other negative effects associated with religious beliefs and behaviors. The present study, in line with most published literature on that topic, clearly shows that such positive effect is rather moderate and can hardly be used as a definite strategy to justify or support religious faith; we need to be more modest when trying such an application. However, that modesty should not discourage a conscious use of religious coping research to better describe the place and role of religious faith in different societies and environments; this could be part of programs in “contextual theology” and religious studies.

The second (2) orientation deals with soteriology or the study of religion as salvation systems. The need to offer a renewed content to salvation as the core of religion, could be helped by religious coping studies: in all modesty, these studies fill a gap and provide data showing a direction in which salvation becomes more concrete and to the point, even if translating salvation traditional expressions into the language of coping can raise some questions; this is indeed just a partial and limited expression: religious coping does not exhaust—by no means—the extent and richness of salvation announced by most religions.

The third (3) issue regards the difficulty in separating religious, and secular, sacred and profane, supernatural and natural when dealing with coping strategies. Such finding appears in line with a view in theology and philosophy of religion that tries to overcome such dualisms and to find out the divine not just in some reality sections or specific events, but extending beyond such limits.

The fourth issue relates to (4) how religious coping and search for meaning before difficulties are so closely related that they need to be studied in the same cluster. Indeed, many data and studies invite to think that we are talking about the same family of attitudes and beliefs when we refer to coping and when we talk about meaning-making. Probably there are just some nuances, or the distinctions reflect different research programs, but it is important to point out to this closely relationship to avoid useless and one-sided reductions (Park, 2010; La Cour and Hvidt, 2010).

The described issues need a better development and assessment after considering the amount of published literature and the extent to which a more empirically inspired study of religion can help to fix several issues present in the current reflection and debates. We hope that our research can add some piece more to the broad and complex mosaic that results from the many published studies on religious coping, and still more those focusing on young populations, in which, due to their development and circumstances, probably coping forms assume a specific style and characteristics.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the agreed upon ethical protocols, as dealing with underage subjects. We offer available analysis from the row data from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahmadi F (2006) Culture, religion and spirituality in coping: the example of cancer patients in Sweden. Uppsala University, Uppsala

Alma H, Pieper J, Van Uden M (2003) When I find myself in times of trouble. Arch Psychol Relig 24(1):64–74

Bjarnason T, Thorlindsson T, Sigfusdotter ID, Welch MR (2005) Familial and religious influences on adolescent alcohol use: a multi-level study of students and school communities. Soc Force 84(1):375–390

Brown TL, Zimmerman GS, Source RS (2001) The role of religion in predicting adolescent alcohol use and problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol 62(5):696–705

Carleton R, Esparza P, Thaxter PJ, Grant KE (2008) Stress, religious coping resources, and depressive symptoms in an urban adolescent sample. J Sci Study Relig 47(1):113–121

Carpenter TP, Laney T, Mezulis A (2012) Religious coping, stress and depressive symptoms among adolescents: a prospective study. Psychol Relig Spiritual 4(1):19–30

Castellini G, Zagaglioni A, Godini L, Monami F, Dini C, Favarelli V (2014) Religion orientations and eating disorders. Riv Psichiatr 49(3):140–144

Davie G (1997) Believing without belonging: a framework for religious transmission. Recher Sociol 28(3):17–37

Desrosiers A, Kelley B, Miller L (2011) Parent and peer relationships and relational spirituality in adolescents and Yound Adults Psychol Relig Spiritual 3(1):39–54

Duque A, Giancola P (2013) Alcohol reverses religion´s prosocial influence on aggression. J Sci Stud Relig 52(2):279–292

Exline JJ (2013) Religious and spiritual struggles. In: Pargament KI et al., (ed) APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality. American Psychological Association, Washington, pp. 459–475

Exline JJ, Park CL, Smyth JM, Carey MP (2011) Anger toward God: social-cognitive predictors, prevalence, and links with adjustment to bereavement and cancer. J Person Soc Psychol 100:129–148

Exline JJ, Pargament KI, Grubbs JB, Yali AM (2014) The religious and spiritual struggles scale: development and initial validation. Psychol Relig Spiritual 6:208–222

Folkman S, Moskowitz JT (2004) Coping: pitfalls and promise. Ann Rev Psychol 55:745–774

Fowler JW (1981) Stages of faith: the psychology of human development and the quest for meaning. Harper & Row, New York

Fowler JW, Dell ML (2004) Stages of faith and identity: birth to teens. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 13(1):17–33

Francis B, Gill JS, Yit Han N, Petrus CF, Azhar FL, Ahmad Sabki Z, Said MA, Ong Hui K, Chong Guan N, Sulaiman AH (2019) Religious coping, religiosity, depression and anxiety among medical students in a multi-religious setting. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(2):259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16020259

Gall TL, Guirguis-Younger M (2013) Religious and spiritual coping: Current theory and research. In: Pargament KI, Exline JJ, Jones JW (eds) APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (vol. 1): context, theory, and research. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp. 349–364

González-Anleo JM, López JA, Valls M, Ayuso L, González G (2010) Jóvenes españoles 2010. Fundación Santa María, Madrid

Good M, Willoughby T (2006) The role of spirituality versus religiosity in adolescent psychosocial adjustment. J Youth Adolesc 35(1):41–55

Hisham AR, Pargament KI (2015) Religious coping among diverse religions: commonalities and divergences. Psychol Relig Spiritual 7(1):24–33

Inman M, Mckeel L, Iceberg E (2014) Do religious affirmations, religious commitments, or general commitments mitigate the negative effects of exposure to thin ideals? J Sci Stud Relig 53(1):38–55

Jung JH (2015) Sense of divine involvement and sense of meaning in life: religious tradition as a contingency. J Sci Stud Relig 54(1):119–133

Kwilecki S (2004) Religion and coping: a contribution from religious studies. J Sci Stud Relig 43(4):477–489

La Cour P, Hvidt NC (2010) Research on meaning-making and health in secular society: secular, spiritual and religious existential orientations. Soc Sci Med 71(7):1292–1299

Latzer Y, Weinberger-Litman SL, Gerson B, Rosch A, Mischel R, Hinden T, Kilstein J, Silver J (2015) Negative religious coping predicts disordered eating pathology among orthodox Jewish adolescent girls. J Relig Health 54:1760–1771

Lord BD, Collison EA, Gramling SE, Weisskittle R (2015) Development of a short-form of the RCOPE for use with bereaved college students. J Relig Health 54:1302–1318

Luhrmann TM (2020) How God becomes real: kindling the presence of invisible others. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., Oxford UK

Mason WA, Windle M (2002) A longitudinal study of the effects of religiosity on adolescent alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. J Adolesc Res 17(4):346–363

McCullong ME, Willoughby B (2009) Religion, self-regulation, and self-control: Associations, explanations, and implication. Psychol Bull 135(1):69–93

McIntosh E (2015) Belonging without believing: church as community in the age of digital media. Int J Public Theol 9(2):131–155

Oser F, Gmünder P (1991) Religious judgement: a developmental approach. Religious Education Press, Birmingham, AL

Pargament KI (1997) The psychology of religion and coping: theory, research, practice. Guilford Press, New York

Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM (2000) The many methods of religious coping: development and initial validation of the RCOPE. J Clin Psychol 56(4):519–543

Pargament K, Zinnbauer B, Scot A et al. (2003) “Red flags and religious Coping: identifying some religious warning signs among people in crisis”. J Clin Psychol 59(12):1335–1348

Pargament KI, Zinnbauer BJ, Scot AB, Bulter EM, Zerowin J (2011) Religious coping from adolescence into early adulthood: their form and relations to externalizing problems and prosocial behavior. J Person 79(4):841–873

Pargament KI, Feuille M, Burdzy D (2011) The brief RCOPE: current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Relig J 2:51–76

Park C (2010) Making sense of the meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychol Bull 136(2):257–301

Pérez PM, Cánovas P (2002) Valores y pautas de interacción familiar en la adolescencia (13-18 años). Fundación Santa María, Madrid

Peterman JS, LaBelle DR, Steinberg L (2014) The relationship between anxiety and religiosity in adolescence. Psychol Relig Spiritual 6(2):113–122

Pirutinsky S, Rosmarin D, Holt C (2012) Religious coping moderates the relationship between emotional functioning and obesity. Health Psychol 31(3):394–397

Rider KA, Terrell DJ, Sisemore TA, Hecht JE (2014) Religious coping style as a predictor of the severity of anorectic symptomology. Eating Disord 22:163–179

Rostosky SS, Danner F, Riggle E (2008) Religiosity and alcohol use in sexual minority and heterosexual youth and youth adults. J Youth Adolesc 37(5):552–563

Rose T, Shields J, Tueller S et al. (2014) Religiosity and behavioral health outcomes of adolescentes living in disaster-vulnerable areas. J Relig Health 54(2):480–494

Saarelainen S-M (2016) Coping-related themes in cancer stories of young Finnish adults. Int J Pract Theol 20(1):69–96

Talik EB (2013) The adolescent religious coping, questionnaire translation and cultural adaptation of Pargament’s RCOPE scale for polish adolescent. J Relig Health 52(1):143–158

Thomas J, Barbato M (2020) Positive religious coping and mental health among christians and muslims in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Religions 11(10):498. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100498

Tromp P, Pless A, Houtman D (2020) ‘Believing without belonging’ in twenty European countries (1981-2008) de-institutionalization of christianity or spiritualization of religion? Rev Relig Res 62:509–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-020-00432-z

Wilchek-Aviad Y, Ne’eman-Haviv V (2015) Do meaning in life, ideological commitment, and level of religiosity, related adolescent Substance abuse and attitude? Child Indic Res https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-015-9310-x

Wills TA, Yaeger AM, James M, Sandy JM (2003) Buffering effect of religiosity for adolescent substance use. Psychol Addict Behav 17(1):24–31

Xu J (2016) Pargament’s theory of religious coping: implications for spiritually sensitive social work practice. Br J Soc Work 46:1394–1410

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Torralba, J., Oviedo, L. & Canteras, M. Religious coping in adolescents: new evidence and relevance. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8, 121 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00797-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00797-8

This article is cited by

-

Religious Identity and its Relation to Health-Related Quality of Life and COVID-Related Stress of Refugee Children and Adolescents in Germany

Journal of Religion and Health (2024)

-

Media Religiosity and War Coping Strategies of Young People in Ukraine

Journal of Religion and Health (2023)

-

Religiosity as a factor of social-emotional resilience and personal growth during the COVID-19 pandemic in Croatian adolescents

Journal of Religious Education (2023)