Abstract

Photojournalistic images shape our understanding of sociopolitical events. How humans are depicted in images may have far-reaching consequences for our attitudes towards them. Social psychology has shown how the visualization of an ‘identifiable victim effect’ can elicit empathic responses. However, images of identifiable victims in the media are the exception rather than the norm. In the context of the Syrian refugee crisis, the majority of images in Western media depicted refugees as large unidentifiable groups. While the effects of the visual depiction of single individuals are well-known, the ways in which the visual framing of large groups operates, and its social and political consequences, remain unknown. We here focus on the visual depiction of refugees to understand how exposure to the dominant visual framing used in the media, depicting them in large groups of faceless individuals, affects their dehumanization and sets off political consequences. To that end we brought together insights from social psychology, social sciences and the humanities to test a range of hypotheses using methods from social and political psychology in 10 studies with the participation of 3951 European citizens. Seeing images of large groups resulted in greater implicit dehumanization compared with images depicting refugees in small groups. Images of large groups are also explicitly rated as more dehumanizing, and when coupled with meta-data such as newspaper headlines, images continue to play a significant and independent role on how (de)humanizing we perceive such news coverage to be. Moreover, after viewing images of large groups, participants showed increased preference for more dominant and less trustworthy-looking political leaders and supported fewer pro-refugee policies and more anti-refugee policies. In terms of a mechanistic understanding of these effects, the extent to which participants felt pity for refugees depicted in large groups as opposed to small groups mediated the effect of visual framing on the choice of a more authoritarian-looking leader. What we see in the media and how it is shown not only has consequences for the ways in which we relate to other human beings and our behaviour towards them but, ultimately, for the functioning of our political systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Images in their many different forms, from paintings to photography and beyond, have always been powerful cultural agents. Their performative power has been extensively discussed across disciplines, from art history (Freedberg, 1991), history of emotions (Plamper, 2017) to media studies (Chouliaraki, 2012; Zelizer, 2010), and more recently political sciences (Bleiker, 2018). The advent of photojournalism endowed photographs with substantial political power due to their capacity to frame reality through the lens, to determine which themes are made visible or not, and to become political forces themselves as they shape our perception of the socio-political events. For instance, Western audiences knew about the Abu Ghraib tortures as news articles were published long before the publication of photographic documentation in 2004 that eventually shifted public opinion (Butler, 2010). Similarly, in the Syrian refugee crisis that started in 2011, the journeys of thousands of refugees fleeing their home country to cross the Mediterranean were widely documented in Western media. However, it was the photograph of the drowned 3-year-old Alan Kurdi, washed up on a Turkish beach on September 2, 2015, that prompted international responses, the EU’s change of policy on refugees (Vis and Goriunova, 2015) and a 10-fold increase in donations (Slovic et al., 2017). The two aforementioned examples highlight the political capacity of ‘iconic’ images that predominantly depict identifiable victims. Social psychology has described the ‘identifiable victim effect’ in detail (Lee and Feeley, 2016; Slovic, 2007), whereby we engage in more pro-social ways (e.g. increased charity donations (Zagefka et al., 2011a) when textual and visual information concern the suffering of a single individual rather than that of large groups. But are these the kind of images that we most commonly see in the media?

In the context of the refugee crisis, analysis of mainstream media in Australia (Bleiker et al., 2013), UK (Wilmott, 2017), US and Germany (Zhang and Hellmueller, 2017) suggest that the majority of images depict refugees in a specific visual framing that is strikingly different from that of the ‘identifiable victim’. Refugees are typically depicted in medium to large groups, without recognizable facial features, and medium-to-long distance camera shots (Batziou, 2011; Bleiker et al., 2013). Given that the majority of images shown in the media are not of identifiable victims, what are the consequences of exposing audiences to photographs of large groups?

This question is timely and crucial for societal and scientific reasons. The impact of certain visual framings may be even more pronounced at times of crisis when the number of images displayed in the news almost doubles (Zelizer, 2010). Understanding how dominant visual framings of large groups, rather than the rare depiction of identifiable victims, operate psychologically can explain how our societies respond during crises or fail to do so (Lenette and Cleland, 2016). While, from a scientific perspective, the prosocial effects of exposure to identifiable victims (Zagefka et al., 2011a) alongside the psychic numbing following exposure to the suffering of many (Lee and Feeley, 2016; Slovic, 2007) are widely documented, the potentially adverse effects that the exposure to the dominant visual frames used by the media may have on people’s attitudes and behavior remains poorly understood. Exposure to images of large groups may either be ineffective (e.g. elicit numbing) without consequential actions or alternatively, they can alter people’s dehumanizing attitudes and their political behavior.

Here we go beyond the well-known identifiable victim (Zagefka et al., 2011a) and the psychic numbing (Lee and Feeley, 2016; Slovic, 2007) effects to test for the first time, across eight main studies and two supplementary studies on European citizens, a series of hypotheses derived from social sciences, media studies and humanities, with methods from social and political psychology. First, we investigated if and how exposure to the dominant visual framings used in the media impacts the viewers’ attitudes and their political behaviour towards refugees. Social sciences have suggested that the dominant way of portraying refugees in large groups is inhumane, as it diminishes the perceived vulnerability of the refugees (Bleiker et al., 2013; Butler, 2010; Slovic, 2007) and emphasizes the security risks of refugee crises (Bleiker et al., 2013; Malkki, 1996), rather than the humanitarian emergency. We, therefore, set out to investigate whether these dominant depictions lead to the dehumanization of refugees in the eyes of the beholders, in other words, the perception of them as lacking, or possessing to a lesser extent uniquely human traits (Haslam and Loughnan, 2014), alongside other groups, e.g. homeless (Harris and Fiske, 2006), Black-Africans (Goff et al., 2008), Arabs (Kteily et al., 2015), survivors of natural disasters (SND) (Andrighetto et al., 2014), immigrants (Bruneau et al., 2018; Leyens et al., 2007; Trounson et al., 2015). We hypothesized that exposing audiences to images of large groups of refugees, as opposed to small groups of refugees, would result in greater implicit dehumanization. Second, and in addition to the general hypothesis concerning the dominant visual framing of large groups, certain visual narratives used to depict refugees may also contribute to their dehumanization. One of the most striking depictions of the refugees’ journeys has been their crossing of the Mediterranean Sea, showing them in a sea context, being rescued or having drowned. Social sciences have proposed that the visual and linguistic (Gabrielatos and Baker, 2008) portrayal of refugees using metaphors of water, waves, tides and ‘floods of water’ (Gabrielatos and Baker, 2008; Wilmott, 2017) reinforces a recurring stereotype of refugees as potentially threatening, uncontrollable agents. We, therefore, tested the effects that exposure to images depicting refugees in the sea, as opposed to land, may have on attitudes. Third, and beyond implicit dehumanization, we also tested how people explicitly judge the humane or inhumane qualities of the depiction itself (i.e. in large groups or in small groups), rather than the depicted people, with and without accompanying textual meta-data. Fourth, we focused on changes in behaviour, rather than attitudes, by testing whether exposure to different visual framings may change people’s support for different policies, as well as their political leader choices and the underlying mechanism of these changes.

To test these hypotheses, we used award-winning photojournalistic images portraying refugees in order to maximize the ecological validity and the transferability of our results to real-life and avoid possible image selection biases. Following the criteria proposed by media studies (Bleiker, 2018) each photo was classified according to the number of people depicted and the recognizability of their facial features: photos of small groups (pSG, n ≤ 8) with recognizable facial features, or of large groups (pLG, n > 8) without recognizable facial features. On purpose we did not contrast images of large groups to images of identifiable victims. Given the vast literature on the potency of the identifiable victim effect, we reasoned that a more appropriate approach would be to compare exposure to images of large groups versus small groups. If we find evidence that exposure to large groups as opposed to small groups results in significant differences in people’s attitudes and behavior, that would provide a more stringent test of our hypothesis.

Methods

All studies were designed and administered using Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com), an online platform for the development and administration of online experiments. These were not pre-registered. Participants were recruited through Prolific (https://www.prolific.ac/), an on-demand, self-service data collection platform for recruiting participants for online studies, and they were compensated with ~£7/h. Participants were informed that we are carrying out a study to investigate how people perceive images depicting different social groups, such as refugees and immigrants, and that they will have to provide subjective ratings and judgments. All studies were carried out according to the Helsinki declaration guidelines and approved by the Ethics committees of the School of Advanced Study, University of London and Royal Holloway University of London. Participants gave their informed consent before taking part. Attention checks were included and are reported in the respective studies. We selected photographs depicting refugees or SND, which have won photojournalism awards or honorary mentions between 1990 and 2017 (see Supplementary Material). Following past research (Bleiker et al., 2013; Wilmott, 2017), each photo was classified unanimously by two independent coders, as depicting: (i) individuals or small groups (n = <8) of refugees, with recognizable facial features (pSG); or I(i) large groups (n > 8) of refugees, without clearly recognizable facial features (pLG) (see Supplementary Material). The final stimuli set consisted of 43 pSG and 39 pLG of refugees. For Studies 2 and 8, a further sub-classification of images was performed according to the visual narrative depicted, namely, whether the refugees were depicted (i) on boats and/or near the sea (Sea, n = 32) or ii) on land (Land, n = 50).

Studies 1–3, including Supplementary Study 1 (see Supplementary Material), examined whether exposure to different visual framings influenced the viewers’ implicit dehumanization. Studies 4 and 5, including Supplementary Study 5 (see Supplementary Material), examined whether different visual framings and newspaper headlines influenced the viewers’ explicit ratings of the humanness of the visual and textual material presented. Studies 6–8 examined whether exposure to different visual framings influenced the viewers’ political behaviour. A summary of the research aims and measures used in each study is presented in Table 1 (a summary of the main and secondary findings of each study can be found in Table S1 of Supplementary Material).

Measures

Dehumanization questionnaire

To measure the impact of visual framing on the attribution of mental states to refugees, we administered, both before and after exposure to our photographic stimuli, a standard dehumanization questionnaire (Leyens et al., 2000; Paladino et al., 2002) that concerns the attribution of primary and secondary emotions.

Visual exposure and distress ratings

Each image was presented for 3 s. Following the presentation of each image, participants rated how distressing it was for them on a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS; 0—not distressing at all; 100—extremely distressing).

Social dominance orientation

Participants’ preference for hierarchy and inequality among social groups was assessed with the 16-item version of the SDO scale (Pratto et al., 1994). For each statement, participants used a scale ranging from 1 (strongly oppose) to 7 (strongly favour). High scores have been shown to predict dehumanization and negative attitudes against immigrants (Esses et al., 2013; Kteily et al., 2015; Trounson et al., 2015). The presentation of items was randomized.

Political orientation

Self-reported political orientation was measured with a Likert scale (1—very Conservative to 7—Very Liberal).

Warmth and competence measures

Ratings of Warmth and Competence were obtained after each image using a slider ranging from ‘cold’ to ‘warm’ and from ‘incompetent’ to ‘competent’, respectively. The following instructions were given, adapted for each group (refugees vs. SND): “How warm (i.e. friendly, trustworthy, warm)/competent (i.e. capable, skilled, competent) do you think the depicted refugees/SND are?”. The presentation order of the questions was randomized.

Ratings of humane depiction (Studies 4 and 5)

Participants were presented with one photo (Study 4), headline (Study S5) or front cover (i.e. Photo/Headline pair; Study 5) at a time, and were asked to judge “How much do you believe the image (Study 4), headline (Study S5) or front cover (Study 5) portrays refugees in a humane way?” using a Likert scale (1—not at all to, 9—very much so). Humane depiction was defined as “refugees portrayed in the same way as national citizens of your country would be, if exposed to and depicted in similar situations”. By contrast, dehumanizing depiction was defined as “depictions of refugees as inferior human beings”.

Signing of petitions task

Participants were provided with two petitions (adapted from Bruneau et al., 2018) and asked to indicate whether they wanted their vote to be counted for (coded as 1), against the petition (coded as −1) or not counted at all (0). The order of presentation of the two petitions was counterbalanced across participants.

Leader choice task

In each trial participants saw two avatar faces, generated by Facegen (Oosterhof and Todorov, 2008; Todorov et al., 2013) and controlled for their level of dominance and trustworthiness (Safra et al., 2017). There were eight different faces comprising every possible combination of dominance and trustworthiness in a range of −2 to +2 points (Oosterhof and Todorov, 2008; Safra et al., 2017) and scaled on both dominance and trustworthiness. The pairs were presented in a random order across 36 trials, and the position of the more dominant face (to the right or left) was counterbalanced between pairs. Before each trial, a fixation cross was presented for 200 ms.

Experienced emotions questionnaire

Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they themselves experienced certain emotions, after each image with a 15-item questionnaire used by Esses (Esses et al., 2013) and Fiske (Fiske et al., 2002) using a VAS scale (0—not at all to 100—very much). Pity toward refugees was calculated as the average of 2 items (pity and sympathetic); Admiration as the average of 5 items (admiring, fond, inspiring, proud, respectful) and contempt as the average of 8 items (angry, ashamed, contemptuous, disgusted, frustrated, hateful, resentful, and uneasy).

Xenophobia Scale

Participants’ fear-related reactions to immigrants and foreigners were assessed using a 5-item xenophobia scale (van der Veer et al., 2011). Agreement with each statement (e.g. “Interacting with immigrants makes me uneasy”) was assessed in a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Scores were summed up. The presentation of the items was randomized.

Realistic and symbolic threat

They were also asked at the end of the experiment to indicate the levels of Realistic (e.g. ‘Because of the presence of refugees, unemployment in Europe will increase’) and Symbolic Threat (e.g. ‘European identity is being threatened because there are too many refugees’) that refugees pose, measured with a three items (randomized order) for each type of threat (Obaidi et al., 2018). Scores were summed up for each measure.

Stimuli

Study 1 used a random selection of 25 pSG and 25 pLG images of refugees from our full stimulus set (available here) and presented to participants in a between-subjects design. Study 2 used a random selection, taken from our full set of images, of 16 sea-pSG, 16 sea-pLG, 16 land-pSG and 16 land-pLG of refugees. In Study 3, each participant was presented with one block of refugee photos and another of SND photos. Each block contained the same number of pLG and pSG images. The order of blocks was counterbalanced, and each block consisted of one of seven random selections, of 24 images per cell, from our full stimulus set. In Study 4, to reduce testing time and fatigue, the stimuli set of refugees photos was randomly divided into two groups, each with a similar number of pSG (n = 21) and pLG (n = 20), and participants were randomly assigned to rate one of the two subsets. In Study 5, 48 headlines (taken from five major UK newspapers) that were previously rated for their ‘humanizing’ or ‘dehumanizing’ portrayal of refugees (Study S5 in Supplementary Material) were paired with photos to create a “news front-cover” in a 2 × 2 within-subjects design: dehumanizing (e.g. “Migrant flood ‘to alter us forever’”) or humanizing (e.g. “Refugees Welcome”) headlines paired with pSG or pLG. We created ten different randomizations consisting of 48 of these ‘front-covers’, each one consisting of a combination of photo and headline. Each randomization contained the following pairs: 12 pLG/12 Humanizing titles; 12 pLG/12 Dehumanizing titles, 12 pSG/12 Humanizing titles; 12 pSG/12 Dehumanizing titles. The average ratings of the headlines (collected in Study S5) paired with pLG and pSG did not differ across randomizations (ps > 0.05). Participants rated each “front-cover” on the extent to which it portrays refugees in a humane way. Studies 6 and 7 used a random selection of 25 pSG and 25 pLG images of refugees from our full stimulus set and presented to participants in a between-subjects design. In Study 8, same as in study 2, a random selection, taken from our full set of images, of 16 sea-pSG, 16 sea-pLG, 16 land-pSG and 16 land-pLG of refugees was used.

Participants

All studies (except Studies 5 and S5) were open to EU nationals and residents (see Table 2). Participants were randomly assigned to different conditions and each study had an independent sample.

For Study 1 a sample size of 477 was estimated to detect a small effect (partial η2 = 0.02) with a power of 0.8 in a multiple regression with 2 predictors. Anticipating some poor quality data, we collected data from 507 participants. The final sample comprised 466 participants (mean age = 32.4, s.d. = 10.5, 257 females, n = 237 for pLG, and n = 229 for pSG), as data from 41 participants was excluded, because they identified themselves as refugees/asylum seekers (n = 1), or they were outliers (n = 40), i.e. whose responses to any of the tasks were more than 2.5 standard deviations higher or lower than the average for that variable.

Study 2 aimed at a sample size similar to Study 1. The final sample comprised 452 participants (mean age = 33.2, s.d. = 9.9). Data from additional 36 participants (outliers (±2.5 s.d. above the mean): n = 32; refugees/asylum seekers: n = 4) were excluded from analyses. Four independent groups of participants rated refugees’ experience of primary and secondary emotions before and after exposure to images of pLG depicted in the sea (n = 111), or on land (n = 113), and pSG depicted in the sea (n = 113) or on land (n = 115).

Study 3, given the within-subject design and the mixed-models analyses, aimed at a lower sample of n = 150–200. The final sample comprised 174 participants (mean age = 33.1, s.d. = 10.8, 114 females). Data from additional 12 outliers (±2.5 s.d. above the mean) was excluded from the analyses.

Study 4 aimed at a sample size similar to Study 3. The final sample comprised 206 participants (mean age = 34.7, s.d. = 9.5, 145 females). Data from 53 additional participants (50 failed at least one of the two attention checks; 2 outliers (±2.5 s.d. above the mean); 1 refugee/asylum seeker) was excluded from analyses.

In line with the strong effect sizes of the Framing manipulation in the within-subjects Studies 3 and 4, Study 5 consisted of 100 participants (mean age = 32.6, s.d. = 10.1, 67 females). Data from 23 additional participants (21 failed at least one attention check (see Supplementary Material); 3 outliers (±2.5 s.d. above the mean)) was excluded from analyses. Recruitment was restricted to UK nationals and residents to avoid language-based misinterpretation of newspaper headlines.

Study 6, in line with two studies using the same measure and analyses (Bruneau et al., 2018; Kteily et al., 2015) aimed at a sample size of 650–700. The final sample comprised 696 participants (mean age = 29.96, sd = 10.71, 343 females; pSG n = 363 for pSG, and n = 333 for pLG). Data from an additional 56 outliers (±2.5 s.d. above the mean), 11 participants who identified themselves as refugees/asylum seekers and 42 participants who failed the attention checks were excluded from analysis.

Study 7 aimed for a sample size similar to Study 1. The final sample comprised 443 volunteers (mean age = 31.28, s.d. = 11.01, 252 females). Data from 29 outliers (±2.5 s.d. above the mean), 2 participants who identified themselves as refugees or asylum seekers, 47 participants who failed at least one attention check and 2 participants for which the logit regression models did not converge were excluded from the analyses.

Study 8 comprised 840 volunteers (mean age = 23.1, s.d. = 7.86, 432 females; sea-pSG = 213; land-pSG = 215; sea-pLG = 203; land-pLG = 215). Data from 29 outliers (± 2.5 s.d. above the mean), 1 participant who identified themselves as refugee/asylum seeker and 15 participants who failed at least one attention check, were excluded from analyses.

Study 1: Rationale and results

We used a between-subject design (Fig. 1A) to test whether exposure to photos of large groups (pLG) or small groups (pSG) of refugees changed participants’ implicit dehumanization of refugees (Leyens et al., 2007, 2000). An important dimension of dehumanization is to consider others as being less capable of experiencing secondary emotions that typically distinguish humans from animals (i.e. tenderness, guilt, and compassion), while the attribution of primary emotions that are shared with animals (i.e. fear, anger, joy) remains unaffected(Costello and Hodson, 2010). This tendency is independent of the emotions’ valence and is therefore not simply a general expression of (dis-)liking (Fiske et al., 2002; Harris and Fiske, 2006; Kteily et al., 2015). We measured the attribution of primary and secondary emotions to refugees before and after exposure to either pLG or pSG. Given our focus on dehumanization, we focused on changes in the attribution of secondary emotions, while controlling for the baseline attribution of secondary emotions and for any changes in primary emotions. We hypothesized that exposure to pLG, as compared to pSG, would lead to a reduced attribution of the uniquely human secondary emotions to refugees, indicative of implicit dehumanization.

A Between-subjects design, Study 1. Pre- and post-exposure to images, participants completed a dehumanization questionnaire that considers the extent to which refugees feel each primary and secondary emotion, by providing a rating using a VAS scale (0—not likely at all; 100—extremely likely). Images depicted here are illustrative examples of the visual framing (i.e. were not presented in any of our studies) Source: Wikimedia Commons, top left link, top right link, bottom left link, bottom right link. B Study 1: Raincloud plot with fitted values of the main effects of Framing on attribution of Secondary Emotions. Y-axis = Assignment of Secondary Emotions after exposure to photographic images. Dots represent single data points; boxplots and half violin plots represent mean and probability distribution according to the condition. Red lines, black points and error bars (SEM) represent fitted values of the main effect of Framing on attribution of secondary emotions. After exposure to pLG of refugees, participants attributed significantly (p < 0.05) fewer secondary emotions to refugees in comparison to pSG. C Study 2 tested four independent groups of participants, reflecting the 2 × 2 between-subjects design of Visual Framing (Large or Small Groups) × Narrative (at the Sea or on Land). Raincloud plot with fitted values of the main effects of Visual Framing on Assignment of Secondary Emotions in function of the Narrative. Y-axis = Assignment of Secondary Emotions after exposure to photographic images of (refugees). Dots represent single data points; boxplots and half violin plots represent the mean and probability distribution according to the condition. Red lines, black points and error bars (SEM) represent fitted values. After exposure to pLG of refugees, participants attributed significantly (p < 0.05) fewer secondary emotions in comparison to pSG when refugees were depicted at Sea (light green, straight red line) rather than at Land (dark green, dotted red line).

Linear regressions were carried out in R (R Core Team, 2013). Post-exposure secondary emotion attribution (Post-Secondary) was entered as a dependent variable on the general linear models. In the first model, additionally to our dummy variable of interest, Framing (0 = pSG; 1 = pLG), respectively. the control variables, pre-exposure secondary emotion attribution (Pre-Secondary) and the difference between post- and pre-exposure assignment of primary emotions (Difference-Primary), and their interactions with Framing were entered in the model. Accounting for Pre-Secondary covariate allowed us to control for the baseline attribution of secondary emotions. Inclusion of the Difference-Primary covariate allowed us to control for any changes in the general attribution of emotions to refugees that are not specific to secondary emotions, our key measure of implicit dehumanization. Unspecific changes in emotion attribution could reflect, for example, perceptions of emotional numbing or distress, instead of the specific negation of complex emotions that characterizes dehumanization (Leyens et al., 2000; Paladino et al., 2002). All covariates were mean centred and scaled. F-values and p-values were estimated with the Anova() function from the car v3.0-3 package library for R (R Core Team, 2013).

In the first regression model (R2 = 0.6989) which included Framing (pSG/pLG) and its interactions with Pre-Secondary and Difference-Primary, exposure to pLG, compared to pSG, resulted in reduced assignment of secondary emotions (F(1460) = 4.420, p = 0.0361, Fig. 1B). Pre-Secondary (F(1460) = 1062.961, p < 0.001) and Difference-Primary (F(1460) = 32.871, p < 0.001) were also significant but, importantly, did not interact with Framing. The inclusion of several covariates of interest—Social Dominance Orientation (SDO), Political Orientation and participants’ average Distress ratings—in the model did not change the pattern of results (see the section “Methods” and Supplementary Material). In addition, as a control analysis, Framing did not predict the attribution of Primary Emotions to refugees after exposure to images (see Supplementary Material).

These results support the hypothesis that photojournalistic images of large groups affect the viewers’ implicit dehumanization of refugees, evidenced by the reduced attribution of uniquely human features to others, a fundamental aspect of social cognition. Past studies that used cartoons, vignettes or textual descriptions suggest that people tend to attribute less mind to individuals when they are perceived in highly cohesive groups but not when they are perceived in heterogeneous groups (Cooley et al., 2017; Morewedge et al., 2013; Waytz and Young, 2012), because perceived homogeneity promotes categorical perception and stereotyping (Cooley and Payne, 2018). Visual depictions of large groups of faceless refugees may promote homogenized perception and stereotyping, whereas small numbers of identifiable refugees primes the viewer to consider them as individuals with minds of their own. However, in a study using a similar design (see S1, Supplementary Material), the dehumanizing effect of pLG vs. pSG, did not generalize to other groups who find themselves in hardship, such as SND, themselves a frequently dehumanized outgroup (Andrighetto et al., 2014; Cuddy et al., 2007). Hence, the effects cannot be solely attributed to the size of any depicted group and are likely to depend on the socio-political and historical connotations associated with specific groups.

Study 2: Rationale and results

Study 2 extended the dehumanizing effect of pLG by testing another hypothesis motivated by visual and linguistic analysis of the refugees’ media portrayal. Widely common media narratives of refugee and asylum seekers make ample use of metaphors of water and flooding (Gabrielatos and Baker, 2008) that has been proposed to reinforce the association between refugees and symbolic threats of cultural deluge (Bleiker et al., 2013; Malkki, 1996; Mannik, 2012). We therefore tested whether exposure to particular visual narratives which reference to the water and sea elements may also increase dehumanization. Four independent groups of participants rated refugees’ experience of primary and secondary emotions before and after exposure to images of pLG depicted in the sea (n = 111), or on land (n = 113), and pSG depicted in the sea (n = 113) or on land (n = 115).

The statistical analysis was identical to that of Study 1, with the dummy variable Narrative (0 = Sea; 1 = Land) and its interactions with the other variables added to the models. The significant interaction was followed by planned post-hoc comparisons, using the emmeans function of R’s CRAN package, to investigate the effect of Framing on each Narrative type and of Narrative on each Framing type. Bonferroni correction was applied to the comparisons made (n = 4).

The first model (R2 = 0.6028) consisted of Framing (pLG/pSG), Narrative (Sea/Land), their interaction, while controlling for Difference-Primary and Pre-Secondary. The interaction Framing × Narrative was significant (F(1440) = 6.518, p = 0.0110; Fig. 1C) as pLG (vs. pSG) were associated with increased dehumanization of refugees for the participants exposed to sea images (t.ratio = 2.90, p = 0.0160) but not those exposed to land images (t.ratio = −0.712, p > 0.99; see Supplementary Material for analysis including covariates of interests). No differences in dehumanization were found between sea and land photos at neither pLG nor pSG (ps > 0.05) (see Supplementary Material for analyses with the covariates). These results extend Study 1 by highlighting the importance of the visual narrative in addition to framing, as seeing large groups in a sea context resulted in the greatest increase in dehumanization. This finding speaks across social sciences and humanities according to which the (visual) use of elements such as ‘water’, ‘waves’, ‘tides’ reinforces representation of refuges as threatening ‘floods of water’ (Malkki, 1996; Mannik, 2012). The visual narrative coupled with the dominant visual framing, may further amplify the implicit dehumanization of refugees, speaking in favour of the ideological and connotative functions of images as semiotic devices (Batziou, 2011; Bredekamp, 2018).

Study 3: Rationale and results

Study 3 provides a conceptual replication of the main Framing effect using a different measure of dehumanization in a more powerful within-subjects design. According to the stereotype content model (SCM) (Fiske et al., 2002), social stereotypes can be captured by the target’s perceived warmth and competence. Warmth closely relates to the person’s perceived intentions and their moral-social values such as trustworthiness and friendliness, while competence refers to abilities, such as intelligence and skills. Lower ratings on warmth and competence denote dehumanization, and have previously been reported for different social groups (Azevedo et al., 2018; Fiske et al., 2002; Harris and Fiske, 2006). We tested whether exposure to pLG or pSG of refugees as well as SND would induce changes in the perceptions of those groups’ social and moral worth (Fig. 2A). We hypothesized that dehumanization, manifested by lower attribution of warmth and competence, will mainly occur in response to pLG, and selectively for refugees. Thus, after each image was presented participants rated how warm and competent they thought the depicted refugees or SND are.

A 2 × 2 within-subjects design of Study 3. Visual framing was randomized within blocks, while block order (i.e. refugees or SNDs) was counterbalanced across participants. B Raincloud plot with fitted values of the main effects of Visual framing on Attribution of Warmth in function of the Visual Framing and the Group (Ref vs. SND). Y-axis = Attribution of Warmth after exposure to photographic images of Ref (refugees, in green) and SND (Survivors of Natural Disaster in red). Dots represent single data points; boxplots and half violin plots represent the mean and probability distribution according to condition. Red line, black points and error-bars (SEM) represent fitted values of the main effect of Visual Framing on Attribution of Warmth in function of the Group (Refugees vs. SND). After exposure to pLG of refugees (green and straight red line), participants assigned significantly (p < 0.01) less warmth than after exposure to pSG, as well as in comparison to SND (red and dotted red line). C Study 4: Explicit ratings (fitted values) of humanness of photographic images across the two Framings. Dots represent single data points; boxplots and half violin plots represent the mean and probability distribution according to condition. Red line, black points and error-bars (SEM) represent fitted values of the main effect of Visual Framing on Ratings of Humanness. Participants rated pLG of refugees as significantly (p < 0.001) less humane than pSG. D Study 5: Explicit ratings (fitted values) of front-covers’ (headlines and images) humanness as a function of Visual Framing (pSG/pLG) and Headlines (Humanizing/Dehumanizing) characteristics. Dots represent single data points, boxplots and half violin plots according to condition pSG/pLG. Red line, black points and error-bars (SEM) represent fitted values. Humanizing Headlines and pSG independently predicted high humanness ratings. The interaction was also significant (p < 0.001), i.e. the combination of pLG with dehumanizing headlines predicted particularly low ratings, and the combination of pSG with humanizing headlines was associated with higher perceptions of humaneness (as reflected by the different slopes in the solid and dashed red lines).

Data was analysed with mixed-model regressions using the lme4 v1.1-17 package for R software. Responses were analysed in two separate mixed-model regressions with Warmth and Competence ratings as dependent variables. In additional second models (see Supplementary Material), we included the covariates SDO and Political Orientation and their interactions with Framing and Group. All covariates were mean centred and scaled. Chisq and p-values for fixed-effect parameters were calculated using the Anova() function from the car v3.0-3 package. Model comparisons, using the loglikelihood ratio statistics asymptotically approximated to a χ2 distribution, were employed to test whether the inclusion of the interaction Framing × Group as random slope over participants improved model fit (Barr, 2013). Whenever convergence or singularity issues were found on model estimation the random slopes structure was simplified. Covariates were mean centred and scaled. Significant interactions were followed by planned post-hoc comparisons, using the emmeans function of the CRAN package, to investigate the effect of Visual Framing on each Group and differences in warmth between groups for each Framing type (Bonferroni-correction: n = 4).

For warmth, the first model that included Framing (pSG/pLG), and its interaction with Group (Refugees/SND), showed a significant Framing × Group interaction (Chisq = 13.379, p < 0.001) whereby, compared to SND, refugees depicted in pLG were judged to be significantly less warm (t.ratio = −3.642, p < 0.001), while for pSG, no significant difference was found between groups (t.ratio = 0.397, p > 0.99, Fig. 2B). Nonetheless, it is worth noting that both groups were judged warmer in pSG (vs. pLG) (refugees: (t.ratio = 9.754, p < 0.001); SND: (t.ratio = 5.680, p < 0.001)).; see also Supplementary Material for additional analysis with covariates). For competence ratings, the Framing × Group interaction (Chisq < 0.01, p = 0.981) was not significant. However, overall, refugees were rated lower than SND (Chisq = 20.249, p < 0.001). The main effect of Framing was not significant (Chisq = 0.574, p = 0.449). Thus, while evaluations of competence are not affected by visual framing, competence is in general lower for refugees than for SND (Harris and Fiske, 2006). The selective effect of visual framing on warmth perception of refugees speaks to the capacity of visual framing to shape attitudes towards refugees, especially when it concerns their affective and moral capacities.

Study 4: Rationale and results

We next set out to understand whether people form corresponding explicit evaluations about the (in)humane qualities of different visual framings, focusing on the depiction itself (i.e. image), and not on the (in)humane qualities of the target (i.e. refugees). In other words, are pSG perceived as portraying refugees in a more humane way than pLG? A new group of participants judged on a Likert-scale (1–9) the extent to which the images used in Study 3 portray refugees in a humane (i.e. as it would portray citizens of their own country), as opposed to a dehumanizing way (i.e. as inferior human beings).

As in Study 3, data was analysed with mixed-models with each participant’s ID as an a priori random factor. Humanness ratings was the dependent variable. All predictors were mean centred and scaled. A stepwise approach was adopted in which we first tested the predictors of interest, i.e. Framing (pSG = 0/pLG = 1), Narrative (Sea = 0/Land = 1), and their interaction. Framing was significant, as pLG were perceived as less humane than pSG (Chisq = 220.498, p < 0.001; Fig. 2C). Interestingly, Narrative (Chisq = 9.128, p = 0.0025) was also found to be significant with sea images perceived as more humane portrayals of refugees than photos in land. The Narrative × Framing interaction (Chisq = 2.153, p = 0.142) was not significant (see Supplementary Material for additional analysis). These findings show how the size of the depicted outgroup and its anonymity influences the explicit evaluation of images. Interestingly, the narrative did not influence explicit judgements of humane qualities of the images, suggesting that while people are able to recognize the inhumanness of pLG, these explicit judgments are less sensitive to the specific narrative portrayed, while their implicit attitudes may be more sensitive (Study 2).

Study 5: Rationale and results

Image are rarely presented in isolation from metadata or textual material such as news articles or headlines that contextualize the images. Such metadata may be thought of as embedding, and potentially reframing the effects of images. The question of how images operate in relation to words remains contested (Zelizer, 2010). Are the effects of combining images and headlines independent, additive or interactive? Can images provide the context that shapes subsequent interpretation of the news? Study 5 answered this question by focusing on the relative balance of power between images and headlines and assessing how different combinations are explicitly evaluated. Forty-eight headlines (taken from five major UK newspapers) that were previously rated for their ‘humanizing’ or ‘dehumanizing’ portrayal of refugees (Study S5 in Supementary Material) were paired with photos to create a “news front-cover” in a 2 × 2 within-subjects design: dehumanizing or humanizing headlines paired with pSG or pLG. Participants rated each “front-cover” on the extent to which it portrays refugees in a humane way.

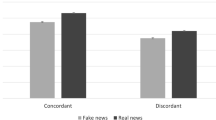

Data was analysed in a series of mixed-model regressions with humanness ratings as a dependent variable. The first model included the dummy variables Framing (0 = pSG; 1 = pLG) and Titles (0 = Inhumane; 1 = Humane), and their interaction. The second model (see SM) included SDO and Political Orientation (both mean centred and scaled), and their interactions with the variables of interest. The Headline × Framing interaction (Chisq = 11.504, p < 0.001) was significant. All post-hocs were significant (t.ratios > 4.335, ps < 0.001) showing that both pLG (vs. pSG) and dehumanizing (vs. humanizing) headlines were associated with lower ratings of the front-covers’ humaneness. Moreover, the combination of strongly dehumanizing headlines and depictions of large groups of refugees predicted particularly low ratings, and the combination of humanizing headlines and pSGs of refugees predicted higher perceptions of humaneness (Fig. 2D, see also Supplementary Material). Thus, images and text can independently affect people’s perception of the (in)humane portrayal of refugees, and distinct combinations amplify such effects.

Study 6: Rationale and results

Having tested for the dehumanizing effects of certain visual framings, as well as their explicit inhumane evaluation, we next focused on the potential political consequences of such images, by testing if exposure to pSG and pLG can influence political behaviour, here operationalized as the tendency to endorse pro- and/or anti-refugee petitions (Kteily et al., 2015) (see Fig. 3). Thus, following exposure to images of pLG or pSG, participants were provided with two petitions presenting pro-refugees and anti-refugees measures, and had to indicate whether they wanted their vote to be counted for the petition, against the petition, or not counted at all.

Plot with predicted values of the main effect of Visual Framing on the probability of signing a Pro-Refugees Petition or an Anti-Refugees Petition. See Tabular results in Supplementary Material.

Choices for each petition (i.e. Pro- and Anti-Refugees Petitions) were analysed in separate ordinal logistic regressions, using the polr () function, with Framing (0 = pSG; 1 = pLG) as dependent variable. Given the direct relevance of the subjective measures collected to political attitudes, the covariates SDO, Political Orientation, Dehumanization Questionnaire (i.e. post-exposure minus pre-exposure), Distress ratings and their interactions with Framing were included. All covariates were mean centred and scaled.

For the pro-refugees petition (Fig. 3), Framing was a significant main predictor (t = −2.513, p = 0.0120; Fig. 3A), while controlling for the covariates of interest—Dehumanization (i.e. post- minus pre-exposure attribution of secondary emotions), SDO scores, Political Orientation and Distress ratings. After exposure to pLG, participants were less likely to support and sign the pro-refugees petition, compared to exposure to pSG. As expected, higher SDO scores predicted lower petition support (t = −6.099, p < 0.001) and liberals were more likely to sign the petition (t = 3.553, p < 0.001). Participants reporting higher Distress, independently of Framing, also showed increased support for the petition (t = 5.156, p < 0.001). None of the covariates showed significant interaction with Framing.

For the anti-refugees petition, participants’ choices to sign for, against or abstain were predicted by their social attitudes, as captured by SDO scores (t = 5.672, p < 0.001) and Political Orientation (t = −2.987, p = 0.0028) but, notably, also by Framing (t = 2.385, p = 0.0171) with those exposed to pLG (vs. pSG) more likely to support it and less likely to sign against it. No covariate was found to interact with Framing (all other ps > 0.05; see Fig. 3). The seizure of refugees’ assets can be considered a rather extreme anti-immigration measure (Bruneau et al., 2018; Kteily et al., 2015) compared to the more passive stance of opposing the allocation of additional resources to support refugees (i.e. signing against the pro-refugees petition). Thus, exposure to images of large groups does not result simply in apathy, but may increase the support for active anti-refugee measures. These findings show the political capacity of the dominant visual framing of refugees in the media, as the significant effect of Framing on the pro-refugee and anti-refugee petitions illustrates the power of images in influencing public support for humanitarian measures. Interestingly however, this does not seem to be moderated by changes in implicit dehumanization. In fact, unlike Studies 1 and 2, Study 6 did not reveal a significant Framing effect on the attribution of secondary emotions to refugees (F(1690) = 0.527, p = 0.468), see also Study 7 and meta-analysis reported after Study 7).

Study 7: Rationale and methods

Beyond the general public’s endorsement or disapproval of policies, our democracies rely on elected politicians to develop and implement them. Immigration policies have been central to political debates in recent elections across European democracies, and the global rise of populist parties led by authoritarian leaders has been partly attributed to anti-immigration sentiments. Study 7 investigated whether the political capacity of visual framing extends to people’s choices of political leaders. We measured participants’ choices of political leaders based on their facial features (Laustsen and Petersen, 2015; Little et al., 2007), in the context of a hypothetical national election. Facial cues inform social judgements, are sensitive to environmental factors and reflect actual political preferences (Little et al., 2007; Olivola et al., 2012; Sussman et al., 2013; Todorov et al., 2005). Indeed, in line with the idea that authoritarianism increases in contexts of social and/or economic threat (Little et al., 2007; Osmundsen et al., 2019), recent research has shown how external threats bias political preferences towards more dominant looking leaders (Laustsen and Petersen, 2015) and authoritarianism in general (Perrin, 2005). Accordingly, we hypothesized that exposure to pLG of refugees that emphasize group-based threat will bias participants’ choices towards more authoritatian looking leaders, i.e. more dominant-looking and less trustworthy-looking leaders. Participants were randomly assigned to the pLG (n = 221) or pSG (n = 222) condition, and performed a leader choice task (Safra et al., 2017; Tsakiris et al., 2021) before and after exposure. In the leader choice task, participants had to choose from a pair of avatar faces, the one which represented their leader preference in a hypothetical national election (Fig. 4A).

A Between-subjects design of Study 7. Prior to exposure to pLG or pSG, participants completed a leader choice task. They had to choose which face out of a pair of avatar faces, scaled according to perceived Trustworthiness and Dominance, they would vote for in hypothetical upcoming national election. During the exposure phase, participants saw 25 images depicting refugees either in pLG or pSG and rated how distressful each image was on a VAS scale (0—not distressing at all; 100—highly distressing). After exposure, they completed again the task. Images depicted here are illustrative examples of visual framing (i.e. were not presented in any of our studies) Source: Wikimedia Commons, top left link, top right link, bottom left link, bottom right link. B Study 7: Raincloud plot with fitted values of the main effects of Visual framing on the probability of choosing a dominant-looking and trustworthy-looking leader (Post- minus Pre-exposure). Y-axis = Probability of choosing a dominant and less trustworthy-looking leader, Post- minus Pre-Image exposure. Dots represent single data points, boxplots and half violin plots represent the mean and probability distribution according to condition. Red line, black points and error-bars (SEM) represent fitted values of the main effect of Visual Framing on the probability of choosing a strong leader. After exposure to photos of large groups of refugees, participants significantly chose a more dominant and less trustworthy leader in comparison to the pSG condition (p < 0.05). C Heatmaps for the probability of choosing a face as a leader according to perceived Trustworthiness (X-axis) and Dominance (Y-axis). Values are probabilities in percentage as a difference of Post–Pre image exposure as well as the difference of photos of Large Groups—photos of Small Groups. After exposure to pLG vs. pSG, participants were more likely to choose a face high in perceived Dominance (red pixels) and low in perceived Trustworthiness (blue).

First, participants’ choices of faces during the Pre- and Post-leader choice task were analysed using a logit regression model for each participant, with the order of presentation as random factor, and faces’ levels of perceived trustworthiness and dominance as fixed effects. The models did not converge for two participants due to a non-sufficient number of valid trials in the tasks; data from these participants was excluded from further analysis. Based on the coefficients of the logit regressions, we then computed the probabilities of choosing a more dominant and less trustworthy looking face as a leader (Safra et al., 2017) for each participant.

Next, a multiple linear regression was carried out in R with the difference between the probabilities of choosing a more dominant and less trustworthy looking leader before and after exposure to images (ProbaPost–ProbaPre) as a dependent variable. Specifically, we measured the main effect of our dummy variable of interest, Framing with our covariates and their interactions with Framing as predicting variables (Political Orientation, Xenophobia Scale, Distress, Difference-Secondary as the difference between post- and pre-exposure in the attribution of secondary emotions). All covariates were mean centred and scaled.

We quantified the effect of Framing (pSG vs. pLG) on the change in the probability of choosing a more dominant and less trustworthy looking leader face in the forced choice task. As predicted, exposure to pLG (compared to pSG) increased the probability of choosing a more dominant and less trustworthy looking leader (R2 = 0.01481; F(1433) = 3.974, p = 0.0468; Fig. 4B, C). In addition to the main effect of Framing on the probability to choose a more authoritarian leader (Post–Pre), the interaction of Framing with Xenophobia (F(1433) = 7138, p = 0.008, see the section “Methods”) was significant: the higher participants scored in the Xenophobia-scale, the more likely they were to increase their preference for authoritarian looking leaders (i.e. more dominant and less trustworthy faces) following exposure to pLG. No other covariates or interaction with Framing were found to be significant.

Thus, exposure to the visual framing of large groups can influence political leader-choices, resulting in an increased support for a more authoritarian-looking leader. Taken together, Studies 6 and 7 demonstrate the political consequences of the dominant visual framing, both for the policies that are supported (or not) by the people, as well as for the choice of their political leaders.

Metanalysis of the implicit dehumanization effect

Interestingly, the political consequences observed in Studies 6 and 7 do not seem to be directly related to changes in dehumanization. For Studies 6 and 7, Framing alone did not influence the implicit dehumanization of refugees (Study 6: F(1690) = 0.527, p = 0.468, and Study 7: F(1437) = 0.065, p = 0.799), nor did dehumanization influence the petition endorsement or the political leader choice, suggesting that visual framing may modulate dehumanization and political behavior independently. Given the divergence in results observed in Studies 1 and 2 and Studies 6 and 7, we carried out a meta-analysis on the effects of Framing across these four studies and confirmed that, on average, there was increased dehumanization of refugees after exposure to pLG compared to pSG (θ = −0.9344, z = −2.262, p = 0.026; Fig. 5). The meta-analysis was carried out using the metaphor Package for R on the coefficient estimates and standard errors from the linear regressions on the main effect of Framing on dehumanization (attribution of secondary emotions) using a fixed effect methods (‘FE’). The Coefficients for Study 2 were estimated in a model without the interaction Framing × Narrative for reliable estimation of Framing without the influence of the interaction. Using the reporter() function for the metaphor Package, the examination of Cook’s distances and studentized residuals (in all studies smaller than ±2.4977), revealed that there was no indication of outliers in the context of this model and none of the studies could be considered to be overly influential. According to the Q-test, there was no significant amount of heterogeneity in the true outcomes (Q(3) = 2.5364, p = 0.4688, I2 = 0.0000%).

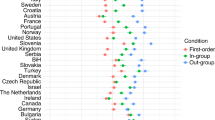

Meta-analysis of Framing’s coefficient estimates on assignment of secondary emotions to refugees across Studies 1, 2, 6, and 7 confirming that on average dehumanization of refugees was greater after exposure to pLG than to pSG Cook’s distances and studentized residuals showed no indication of outliers in and the Q-test and I2 suggest no evidence of heterogeneity in this model.

The meta-analysis substantiates the overall reliability of the Framing effect. Whereas our reported effect sizes are small to medium, when considering the en-masse effects on the general population, repeatedly exposed to considerably more images than the ones presented in our studies, visual exposure to pLG can have substantial real-life social and political consequences.

Study 8: Rationale and results

The lack of a dehumanization effect, at least as measured in Studies 6 and 7, on political behaviour suggests that it is not the emotions observers attribute to the refugees that are driving these political changes. Instead, in line with past findings, the role of emotions people experience themselves during different visual depictions may be more important in bringing about these effects. Esses and colleagues (Esses et al., 2013, 2008) have shown that emotional reactions elicited by dehumanizing media editorials mediated negative attitudes towards refugees and refugee policy (Esses et al., 2008). Study 8 investigated the mechanism whereby visual framing elicits distinct patterns of emotional reactions which may in turn influence participants’ political behaviour. In a between-subjects design, participants rated, after each picture, to what extent they themselves felt emotions of pity, contempt and admiration toward the depicted refugees (Esses et al., 2013, 2008). Before and after visual exposure, participants performed the Leader-Choice Task (see Fig. 6A) and then rated how threatening refugees were in terms of symbolic (i.e., threats to the in-group’s norms, values, and culture) and realistic threat (i.e., threats to the in-group’s economic or political power or physical wellbeing) (Obaidi et al., 2018).

A Between-subjects design of Study 8. Before and after exposure to images, participants completed a leader-choice-task. During exposure (16 images of refugees pLG/pSG; Land/Sea) participants rated after each image, to what extent they felt 15 emotions towards the depicted refugees (VAS scale; 0—not at all—100 —very much so). Pity toward refugees was calculated as the average of two items (pity and sympathetic); Admiration as the average of five items (admiring, fond, inspiring, proud, respectful) and contempt as the average of eight items (angry, ashamed, contemptuous, disgusted, frustrated, hateful, resentful, and uneasy). B Heatmaps for the change (post minus pre) in probability of choosing a face as a leader according to perceived Trustworthiness and Dominance. C Structural equation model predicting Leader-Choice and symbolic and realistic threat. Standardized parameter estimates are shown in blue for negative and red lines for positive significant relationships. PA = Political attitude, conservative-liberal (0–7); Framing = pSG(0), pLG(1); Narrative = sea(0), land(1); SDO = Social Dominance Orientation) Political Leader Choice (Post–Pre exposure to images of refugees). D Plot of significant indirect effects of Framing (green) and Narrative (purple) on Leader-Choice behaviour, perceptions of symbolic and realistic threat via felt Emotions (Pity, Admiration, and Contempt) towards refugees. Significant negative paths are plotted in dotted and significant positive paths in solid lines. All indirect effects presented positively predict the manifest variables Leader-Choice, Symbolic and Realistic threat; i.e. both pLG and images on Land are positively related to socio-political variables via the respective emotions (see also Table S3 in Supplementary Material).

In order to develop a more mechanistic understanding on how visual images may impact viewers’ threat perceptions and political behavior, we used path analysis in structural equation modeling (SEM), to investigate whether participants’ emotional reactions during exposure to images (contempt, pity, admiration) mediate the effects of Framing and Narrative on leader choice (ProbaPost–ProbaPre) and on perceived realistic and symbolic threat (see Fig. 6c and d for the model specification and SM for all effects coefficients). All models were estimated in the lavaan package for R[version 0.6-4] using full information maximum likelihood. Overall model fit was assessed with the comparative fit index and SRMR.

The model [CFI = 0.854; SRMR = 0.065] revealed that exposure to pLG (β = −0.181, p = 0.006) and pictures of refugees on land (β = −0.197, p = 0.003) resulted in reduced felt pity (R2 = 0.235) and admiration (R2 = 0.111; with pLG: β = −0.313, p < 0.001; land: β = −0.199, p = 0.004). Conversely, exposure to land pictures increased contempt (R2 = 0.078, β = 0.242, p = 0.001). Ratings of pity (β = −0.013, p = 0.003) towards refugees directly predicted Leader Choice (R2 = 0.025): the less they reported feeling pity towards refugees, the more likely they were to choose the more dominant and less trustworthy face. Importantly and relevant for understanding the mechanism by which visual depictions impacts political behavior, we observed indirect effects of both Framing (β = 0.002, p = 0.044) and Narrative (β = 0.002, p = 0.036) through pity on Leader Choice: the less participants reported feeling pity for refugees depicted on pLG, the more likely they were to choose an authoritarian looking leader. In addition, the less participants reported feeling pity for refugees depicted on land in general, the more likely they were to choose an authoritarian leader.

While perceptions of Symbolic Threat (R2 = 0.486) towards refugees were not directly affected by Framing and Narrative, indirect effects of both were observed. That is, refugees were judged to pose greater symbolic threat after exposure to pLG through diminished feelings of pity (β = 0.025, p = 0.017) and admiration (β = 0.024, p = 0.019). Further, photos of refugees arriving on land were associated with enhanced perceptions of symbolic threat through the experience of contempt (β = 0.017, p = 0.042), diminished pity (β = 0.028, p = 0.011) and reduced admiration (β = 0.015, p = 0.048). Perceptions of Realistic Threat (R2 = 0.331) were directly predicted by Narrative (β = −0.125, p = 0.042) and indirectly through feelings of contempt (β = 0.035, p = 0.006). Overall, participants exposed to images of refugees at sea (vs. land) perceived them as an important realistic threat to the ingroup. However, when indicating high feelings of contempt after exposure to images showing refugees on land participants also rated refugees as being of considerate realistic threat. The above pattern of results demonstrates once more the importance of emotive reactions to the pictures in the mediation of Framing and Narrative effects. Moreover, it is interesting to note that Framing was particularly associated with the modulation of emotions perceived as “high warmth” (pity and admiration) (Oosterhof and Todorov, 2008) and with perceptions of symbolic (but not realistic) threat which further suggests its impact on socio-moral outgroup evaluations (see Study 3).Taken together, these results advance our understanding of the effect of Framing on political leader choice of Study 7 by explaining aspects of the mechanism whereby Framing and Narrative may independently influence political behavior via distinct emotional reactions.

General discussion

Going beyond the well-studied pro-social changes in attitudes and behavior in response to iconic images of identifiable victims (Slovic, 2007; Slovic et al., 2017; Zagefka et al., 2011a), we investigated the potential adverse effects of the most commonly used, yet understudied, visual framing of large outgroups, in particular of refugees. We tested a series of multi-disciplinary hypotheses on whether and how exposure to news images influence our perceptions of and political behaviour towards the highly stigmatized outgroup of refugees. Unsurprisingly, depicting refugees in large groups is explicitly evaluated as a less humane way of visualizing them (Studies 4 and 5). Beyond such explicit evaluations, Studies 1–3 and a meta-analysis showed that exposure to the current dominant visual framing of refugees, namely that of large anonymized groups, reduced the attribution of uniquely human characteristics to the depicted refugees. This effect cannot be simply attributed to differences in distress (Sontag, 1979) that viewers may experience when exposed to different framings, as reported distress did not vary according to framing. In general, people tend to attribute less mind to individuals perceived in cohesive groups (Malkki, 1996; Mannik, 2012; Morewedge et al., 2013) by showing selective dehumanization according the group’s social characteristics. Interestingly, increased dehumanization was not observed for large groups of SND suggesting that the effect of visual framing on the refugees’ dehumanization is not simply denotative, in the sense that seeing any anonymous group literally hinders the identification of human subjects. Cognitive processes of categorial perception and stereotyping are subject to historical and social contexts and the saliency of the refugee crisis in western media over the recent years (Johnson, 2018) may explain the selective effect we observed.

Beyond the denotative level, our findings demonstrate the power of specific visual framings at the connotative and ideological levels. The fact that exposure to pLG may increase dehumanization of refugees resonates with the view that current visual representations of refugees emphasize a security rather than a humanitarian debate, as refugees are visually represented ‘as being a crisis’ for host nations, rather than finding themselves in a crisis’ (Malkki, 1996; Nyers, 2006). Drawing on the parallels between the common visual depiction of refugees in the sea and linguistic narratives that compare refugees to elemental forces such as water and flooding (Bleiker et al., 2013; Malkki, 1996; Mannik, 2012), we find tentative support for this connotative hypothesis that a narrative conveyed by metaphors of water may increase dehumanization. Connotation refers to the cultural and historical meanings added to a sign’s literal meaning. Here, we found evidence that depictions of large refugee groups in the sea may indeed further increase their dehumanization (Study 2) and, through separate cognitive processes, independently promote perceptions of realistic threat in the case of sea images and symbolic threat for land images (Study 8). Other inferences or associations, such as perceived vulnerability or incurred risk, might also contribute to the observed effects and should be tested in future studies.

In general, while the effect of faming on dehumanization is in the same direction across all studies, we do note that neither in Study 6 nor in Study 7 this effect reaches significance. The meta-analysis, and the replication with an alternative measure that we used in Study 3 provides support in favour of a general effect of framing on dehumanization. Moreover, as Study 2 shows it may be the case that the effect of framing on dehumanization is more pronounced for images that depict refugees in the sea element, and we note that in Studies 6 and 7 images of refugees in both land and sea were used. This may explain why the effect is at trend level in these studies, but we note that the interpretation of a null finding must always be done cautiously. Study 7 also had a different design, as it started with the political leader choice task and that may have framed the dehumanization questionnaire in a different way. Lastly, future studies could focus in more systematic ways in how citizens from different EU countries, depending on the specific geopolitical features of their country, may be differently affected by Framing and Narrative.

As we show, visual framing (Studies 6–8), can impact both the endorsement of policies as well as the hypothetical choice of political leaders. Undoubtedly, voting preferences are best explained by the candidate’s positions but we often form rapid automatic inferences from the facial appearance of political candidates (Todorov et al., 2005). Increased preference for facial dominance in leaders is thought to reveal the electorate’s support for a leader capable of enforcing actions and policies to protect the ingroup (Laustsen and Petersen, 2015). Our findings on the effects of framing-driven biases on political leader choices, reduced endorsement of pro-refugee policies and increased endorsement for anti-refugee policies accord with such findings and demonstrated the political power of imagery to bias political choices. Importantly, it is not the emotions that viewers attribute to the depicted groups that drive these political consequences, but instead it is the emotions that the viewers themselves experience when looking at these images of large groups. In particular, the experience of pity mediated the relationship between visual framing and political leader choice, but also perceived symbolic threat. In line with insights from psychology (Esses et al., 2008; Fiske et al., 2002) and humanities (Freedberg, 1991), images function as semiotic devices (Batziou, 2011; Bredekamp, 2018), that elicit-specific emotional reactions to the visually depicted human beings, ultimately affecting the ways we relate to one another.

In the present studies, we focused primarily on what is considered to be the most important and salient dimension in the visual documentation of humanitarian crises, namely the size of the depicted group, and therefore our conclusions concern the role of group framing. However, images and especially photojournalistic ones vary on several different dimensions, such as their iconography, depicted emotions, gendered aspects to name a few. Even though we used highly ecological stimuli, future studies must further explore the roles of different dimensions and ascertain their potential political power. Lastly, while our studies demonstrated the effects of Framing and Narrative on dehumanization and independently on political behaviour, we note that our focus here was on implicit dehumanization. Given that blatant dehumanization is predictive of numerous consequential attitudes and behaviours, future studies could further explore how the effects of visual exposure to such images influence explicit forms of dehumanization.

There are no neutral ways to visually depict human beings. Neither the medium itself can afford such neutrality, nor the photographers, the publishers or the spectators. Across history, images of refugees change as socio-political discourse, cultural norms and humanistic values—or lack thereof—change (Johnson, 2018). What seemed to be a strategic decision to display refugees as helpless groups devoid of individuality with the hope to increase public support in the sixties, no longer functions in the same way (Johnson, 2018). Nowadays, the removal of individuality, rather than countering the public’s fear, enhances the dehumanization of refugees and the political consequences of specific visualizations. Therefore, the decision of what is made visible, and how, should be thought of as a choice that has consequences for the ways in which we perceive and relate to other human beings, especially in a culture that is powered by images at unprecedented levels.

Data availability

All materials, data-sets and scripts are available at the Open Science Framework https://osf.io/ap9f7/.

References

Andrighetto L, Baldissarri C, Lattanzio S, Loughnan S, Volpato C (2014) Human-itarian aid? Two forms of dehumanization and willingness to help after natural disasters. Br J Soc Psychol 53(3):573–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12066

Azevedo RT, Panasiti MS, Maglio R, Aglioti SM (2018) Perceived warmth and competence of others shape voluntary deceptive behaviour in a morally relevant setting. Br J Psychol 109(1):25–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12245

Barr DJ (2013) Random effects structure for testing interactions in linear mixed-effects models. Front Psychol 4:328. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00328

Batziou A (2011) Framing ‘Otherness’ in press photographs: the case of immigrants in Greece and Spain. J Media Practice 12(1):41–60. https://doi.org/10.1386/jmpr.12.1.41

Bleiker R (ed) (2018) Visual global politics. Routledge, New York

Bleiker R, Campbell D, Hutchison E, Nicholson X (2013) The visual dehumanisation of refugees. Austral J Polit Sci 48(4):398–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2013.840769

Bredekamp HH (2018) Image Acts: A Systematic Approach to Visual Agency. Berlin and Boston, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 361.

Bruneau E, Jacoby N, Kteily N, Saxe R (2018) Denying humanity: the distinct neural correlates of blatant dehumanization. J Exp Psychol 147(7):1078–1093. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000417

Bruneau E, Kteily N, Laustsen L (2018) The unique effects of blatant dehumanization on attitudes and behavior towards Muslim refugees during the European ‘refugee crisis’ across four countries. Eur J Soc Psychol 48(5):645–662. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2357

Butler J (2010) Frames of war: When is life grievable?. London, Verso.

Chouliaraki L (2012) The ironic spectator, solidarity in the age of post-humanitarianism. Polity Press.

Cooley E, Payne BK (2018) A group is more than the average of its parts: why existing stereotypes are applied more to the same individuals when viewed in groups than when viewed alone. Group Process Intergroup Relations 136843021875649. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430218756494

Cooley E, Payne BK, Cipolli W, Cameron CD, Berger A, Gray K (2017) The paradox of group mind: “People in a group” have more mind than “a group of people”. J Exp Psychol 146(5):691–699. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000293

Costello K, Hodson G (2010) Exploring the roots of dehumanization: the role of animal–human similarity in promoting immigrant humanization. Group Process Intergroup Relations 13(1):3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430209347725

Cuddy AJC, Rock MS, Norton MI (2007) Aid in the Aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: Inferences of Secondary Emotions and Intergroup Helping. Group Processes Intergroup Relations 10(1):107–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430207071344

Esses VM, Medianu S, Lawson AS (2013) Uncertainty, threat, and the role of the media in promoting the dehumanization of immigrants and refugees. J Soc Issues 69(3), 518–536.

Esses VM, Veenvliet S, Hodson G, Mihic L (2008) Justice, morality, and the dehumanization of refugees. Soc Justice Res 21(1):4–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-007-0058-4

Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P, Xu J (2002) A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J Personal Soc Psychol 82(6):878–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878

Freedberg D (1991). The power of images, studies in the history and theory of response. The University of Chicago, Press Books.

Gabrielatos C, Baker P (2008a) Fleeing, sneaking, flooding. J Engl Linguist 36(1):5–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424207311247

Goff PA, Eberhardt JL, Williams MJ, Jackson MC (2008) Not yet human: implicit knowledge, historical dehumanization, and contemporary consequences. J Personal Soc Psychol 94(2):292–306. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.292

Harris LT, Fiske ST (2006) Dehumanizing the lowest of the. Psychol Sci 17(10):847–853. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01793.x

Haslam N, Loughnan S (2014) Dehumanization and Infrahumanization. Annu Rev Psychol 65(1):399–423. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115045

Johnson H (2018) Refugees. In: Bleiker R (Ed.) Visual global politics. Routledge, New York

Kteily N, Bruneau E, Waytz A, Cotterill S (2015) The ascent of man: theoretical and empirical evidence for blatant dehumanization. J Personal Soc Psychol 109(5):901–931. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000048

Laustsen L, Petersen MB (2015) Does a competent leader make a good friend? Con- flict, ideology and the psychologies of friendship and followership. Evol Hum Behav 36(4):286–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2015.01.001

Lee S, Feeley TH (2016) The identifiable victim effect: a meta-analytic review. Soc Influ 11(3):199–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2016.1216891

Lenette C, Cleland S (2016) Changing faces: visual representations of asylum seekers in times of crisis. Creative Approaches Res 9(1):68–83

Leyens J-P, Demoulin S, Vaes J, Gaunt R, Paladino MP (2007) Infra-humanization: The Wall of Group Differences. Soc Issues Policy Rev 1(1):139–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2007.00006.x

Leyens J-P, Paladino PM, Rodriguez-Torres R, Vaes J, Demoulin S, Rodriguez-Perez A, Gaunt R (2000) The emotional side of prejudice: the attribution of secondary emotions to ingroups and outgroups. Personal Soc Psychol Rev 4(1):186–197. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_06

Little AC, Burriss RP, Jones BC, Roberts SC (2007) Facial appearance affects voting decisions. Evol Hum Behav 28(1):18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2006.09.002

Malkki LH (1996) Speechless emissaries: refugees, humanitarianism, and dehistoricization. Cult Anthropol 11(3):377–404

Mannik L (2012) Public and private photographs of refugees: the problem of representation. Visual Stud 27(3):262–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2012.717747

Morewedge CK, Chandler JJ, Smith R, Schwarz N, Schooler J (2013) Lost in the crowd: entitative group membership reduces mind attribution. Conscious Cogn 22(4):1195–1205. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CONCOG.2013.08.002

Nyers P (2006) Rethinking refugees beyond state of emergency. Routledge, New York

Obaidi M, Kunst JR, Kteily N, Thomsen L, Sidanius J (2018) Living under threat: Mutual threat perception drives anti-Muslim and anti-Western hostility in the age of terrorism. Eur J Soc Psychol 48(5):567–584. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2362

Olivola CY, Sussman AB, Tsetsos K, Kang OE, Todorov A (2012) Republicans prefer republican-looking leaders political facial stereotypes predict candidate electoral success among right-leaning voters. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 3(5):605–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611432770

Oosterhof NN, Todorov A (2008) The functional basis of face evaluation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(32):11087–11092. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0805664105

Osmundsen M, Hendry DJ, Lautsen L, Smith KB, Petersen MB (2019) The psychophysiology of political ideology: replications, reanalysis and recommendations. 93–110. http://kiss.kstudy.com/search/detail_page.asp?key=3165102

Paladino M-P, Leyens J-P, Rodriguez R, Rodriguez A, Gaunt R, Demoulin S (2002) Differential association of uniquely and non uniquely human emotions with the ingroup and the outgroup. Group Processes Intergroup Relat 5(2):105–117. 10.1177%2F1368430202005002539

Perrin AJ (2005) National threat and political culture: authoritarianism, antiauthoritarianism, and the September 11 attacks. Political Psychol 26(2):167–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00414.x

Plamper J (2017) The history of emotions, an introduction. Oxford University Press.

Pratto F, Sidanius J, Stallworth L, Malle B (1994) Social dominance orientation: a personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. J Personal Soc Psychol 67:741–763. 0022-3514/94/

R Core Team (2013) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Safra L, Algan Y, Tecu T, Grèzes J, Baumard N, Chevallier C (2017) Childhood harshness predicts long-lasting leader preferences. Evol Hum Behav 38(5):645–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2017.05.001

Slovic P (2007). If I look at the mass I will never act;: psychic numbing and genocide. Judgm Decision Making 2. http://journal.sjdm.org/jdm7303a.pdf

Slovic P, Västfjäll D, Erlandsson A, Gregory R (2017). Iconic photographs and the ebb and flow of empathic response to humanitarian disasters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114(4), 640–644. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1613977114