Abstract

Biomedical literature and policy are highly concerned with encouraging and improving the clinical application and clinical benefit of new scientific knowledge. Debates, theorizing, and policy initiatives aiming to close the “bench-to-bedside gap” have led to the development of “Translational Research” (TR), an emerging set of research-related discourses and practices within biomedicine. Studies in social science and the humanities have explored and challenged the assumptions underpinning specific TR models and policy initiatives, as well as the socio-material transformations involved. However, only few studies have explored TR as a productive ongoing process of meaning-making taking place as part of the everyday practices of the actual researchers located at the very nexus of science and clinic. This article therefore asks the question of how the discourse and promise of translation is embedded and performed within the practices and perspective of the specific actors involved. The findings are based on material from ethnographic fieldwork among translational researchers situated in a Danish hospital research setting. The analysis draws on the analytical notion of performativity in order to approach statements and models of TR in the light of their performative dimension. This analytical approach thus helps to highlight how the characterizations of TR also contain prescriptions for how the world must change for these characterizations to become true. The analysis provides insights into four different characterizations of TR and reflects on the associated practices where performative success is achieved in practice. With the presentation of these four characterizations, this paper illustrates different uses of the term TR among the actual actors engaged in research-clinic activities and contributes insight into the complex processes of conceptual and material reorganization that form part of the emergence of TR in biomedicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Translational research has become subject to widespread debates in biomedical literature and politics, evoking high expectations, promises, and concerns. The term “translational research” was first used in a US national cancer program in the 90’s and has since appeared in research programs, research strategies, academic articles and journals, policy reports, and educational programs globally. The main interest underlying the concept in this normative policy oriented debate derives from a perceived series of gaps between life sciences, medical research, clinical practices, and effects in the form of, e.g., measurable health improvements. The rationale and promise of TR is to ensure and encourage that public investments in health science are turned into improved care practice and improved public health. The term TR is used interchangeably with other terms such as translational medicine, translational science, academic medicine, medical knowledge translation etc. TR is closely linked to research policy, funding incentives as well as organizational transformation in Europe, US, Australia, and more recently the Nordic countries, where Academic Health Science Centers (AHSCs) have been established in recent years to encourage translational interaction between research and clinic. As such, TR is important as a pervasive discourse in medical science and as a socio-economic reorganization of research practices. Existing studies have pointed to the multiple meanings of translational research in ongoing academic and policy debates—and to the way in which this concept is tied to a range of varying problems and possible solutions, not only in different medical fields but also in different national contexts (Crabu, 2018; Greenhalgh and Wieringa, 2011; Krüger et al., 2018; van der Laan and Boenink, 2015). Very few studies, however, focus empirically on how these expectations and characterizations of TR hold true in the context of actual researcher practices.

This article reports on an ethnographic case study of translational research networks in a Danish university hospital setting. The investigation focused empirically on the nature of these translational activities and on how translational research was “made to work” in a specific research-hospital setting. This article presents a particular sub-set of the data in order to explore how the translational researchers themselves understood and used the concept of translational research (TR). Focus is thus on how actors in a Danish research setting are entangled in wider discourses of TR and how they take part in performing TR discursively and materially. The analysis draws on key ideas from the work of Science and Technology Studies in order to understand TR as a set of performative statements and ideas that generate their own practices and thereby create the world they describe (Mackenzie et al., 2007; Mol, 2002). As such, the article contributes empirical insights into the researchers’ own descriptions and models regarding the concept, how the concept was performed in the setting studied, how researchers engaged with the concept, and what they made of it.

The article is structured as follows. First, I briefly present the literature on the concept of TR. The next section presents the methodological and theoretical backdrop for the research reported and the areas of investigation, translational research grounded in the fields of psychiatry and oncology. Hereafter, key statements and examples from the data are presented and analyzed. Lastly, the discussion reflects upon TR as a complex process of meaning production and material reorganization.

Translational research

In an important article from 2012, Van der Laan and Boenik “disentangle” the concept and rhetoric of TR and its different meanings, both historically and philosophically (van der Laan and Boenink, 2015). They focus on the extensive and exponential use of the concept in biomedical scientific literature during the years 1993–2010 and present different epistemic dimensions regarding the way the concept is interpreted and used. Krueger, Hendriks, and Gauch’s more recent literature survey of the term in biomedical and clinical research also finds a “kaleidoscope” of different dimensions, understandings, and applications related to the term (Krüger et al., 2018).

Despite the variances, one focal figure in this literature is the trope of “bench to bedside”. Here, TR is a science-clinic-public relationship conceptualized as a set of translational phases through which knowledge moves from basic biomedical research into diagnosis or treatment, subsequent development into evidence-based protocols, following deployment in clinical practice, and, ultimately, benefits for the individual and society through improvement of public health. The term implies a relocation and translation of knowledge across what are conceived of as somewhat separate domains. Yet, as noted in the existing literature studies, the way in which the specific gaps, models, and problematic barriers are constructed vary greatly. Likewise, the understanding of the very domains involved differs. Basic science, clinical research, clinical practice, the public, society, and politics are also defined and delineated in varying ways.

The social sciences and humanities have entered into and contributed to the biomedical debate on translational research, as recently reviewed by Crabu (2018). Work in these areas has challenged the transfer notion implicitly found in much of the literature on translational science—as well as the fundamental distinction between basic and applied science. Qualitative empirical studies also bring our attention to the very complex collaborations and recursive pathways of TR, where valuable breakthroughs in science and treatments can emerge by way of the clinical staff and their daily questions and puzzles, from patients or patient groups, commercial activity, or policy demands. The creation of new medical knowledge can thus have many “starting points” in addition to basic science, thus challenging the linearity implied in many discussions and policies on TR. In their study of laboratory and clinical practices related to Huntington Disease, Lewis, Hughes, and Atkinson, for example, point to TR as a complex of clusters and multiple processes of relocation and reconfiguration as objects, knowledge, practices, and resources are circulated between multiple sites (Lewis et al., 2014). Based on a study of health care innovation through extended translational networks in Canada, Lander and Atkinson-Grosjean (2011) likewise describe various hybrid domains of translational science that cut across presumed divides between basic science, clinic, as well as commercial and civic areas. Their study also illustrates how translational pathways flow through the interactions and relations among a complex collection of actors and organizations (Lander and Atkinson-Grosjean, 2011). This complexity is less visible in the normative depiction of TR as a unidimensional line from basic research to clinical practice and then to public health.

The study reported on in this paper converges with this line in the literature located in social science and the humanities, both openly exploring the complexities of TR and challenging the foundations and presuppositions of a normative TR agenda. The article focusses on the question of how actors involved in TR in a specific research-hospital setting engage with and use the concept. The exploration asks open questions as to which statements and models of TR circulate among these actors? What does TR mean in the context studied? How do these statements and models participate in shaping research and clinical practice? How does TR relate to other concepts and concerns? In exploring these questions, different understandings have emerged from the data, summarized here as four themes: TR as knowledge flow, TR as a political buzzword, TR as collaboration and exchange, and TR as competency and skills. Each of these understandings is depicted in turn in the analysis section. Based on this analysis, the paper contributes to existing social science and humanities explorations of TR and adds to existing work by illustrating the ways in which the concept of TR circulates in a particular setting and how the concept is adopted and used by actors in this setting as part of their everyday practice. The paper argues that these performative uses of the term are material and productive as they contribute to organizing work, as well as attaching value to specific kinds of work and specific skills.

The study

The study reported here is based on ethnographic fieldwork in Danish hospitals carried out between January 2018 and March 2019. I conducted interviews and observations and collected a broad range of organizational and project documents. Observations included research team meetings, departmental meetings, public presentations of research, two academic conferences, patient testing and treatment, lab visits and informal conversations (~100 h). I took hand written notes during observation and subsequently wrote these out in text files—with concurrent memoing. Observations and informal conversations provided data on daily experiences and were linked to formal interviews that were conducted in parallel (n20). Interviews were conducted with various team members, primarily clinician-scientists (n11) but also research team members such as Ph.D. students (n4), biologists (n2), an engineer (n1), and lastly two department managers (n2). The interviews lasted 1–2 h, were recorded and transcribed with the respondents’ consent. All interviews were conducted at the hospitals and were semi-structured and included questions about the participants’ definitions, understandings, and models regarding the concept of TR. Data was stored, organized, and coded in the qualitative data analysis software NVivo using grounded theory and analytical tools from situational analysis (Clarke, 2005). The findings presented in this paper draw on a sub-set of the data regarding the way in which the translational researchers themselves understood and used the concept TR.

Ethical approval and consent were obtained in writing from the principle investigators of the research networks and from the informants. The project was also approved by the hospital management and reported to the regional ethics committee. Throughout the research project, I was simultaneously working as a consultant in a crosscutting research and innovation support unit at the hospitals. This involved weekly visits, meetings, workshops, and communication with staff and management at the hospital departments on issues related to research development and support in the region. This concurring consultancy work gave me a background understanding of the organization and the research infrastructure of the hospitals, but it is not included as a formalized part of the dataset due to research ethics of a dual role of employee and researcher.

Oncology and psychiatry

The setting for the research here is Region Zealand in Denmark and in particular two research networks based in the regional hospitals. These research networks connect different research projects or research protocols within a joint vision of changing and improving diagnosis and/or treatment within two very different medical areas, child and youth psychiatric diagnosis and cancer treatment. The two translational research networks were interdisciplinary, yet anchored in the two domains of oncology and psychiatry, referred to here as the electroporation and autism networks. The electroporation case was an international collaborative network working to develop and improve a new type of treatment for cancer, electroporation. This technique creates an electrostatic field in cancer cells in order to increase the permeability of the cell membrane, allowing chemicals, drugs or DNA to be introduced into the cell. When applied locally, this type of treatment has been found effective in killing the cancer cells of the tumor, and the treatment with this technique combined with administering calcium was found to release patterns into the immune system, possibly hindering a recurrence of the tumor and slowing further spreading of the cancer. A range of related projects sought to refine the technique in relation to specific cancer types and in relation to different types of chemicals, and to explore systemic immune responses of the treatment found clinically as an unexpected outcome of the treatment. This network played an important role in developing and implementing this particular type of cancer treatment internationally. The group was involved in developing European guidelines for clinical practices and in various political and practical implementation efforts to establish the treatment type as part of the standardized treatment program for specific cancer types in Denmark. The researchers were thus deeply engaged in research, but they were also focused on realizing its application in the clinic. Most of the researchers were also responsible for everyday clinical practices of examining patients and determining treatment strategies.

The second research network I studied conducted research on autism disorders in children and youth through a translational research design combining behavioral, psychological, and neurobiological approaches. The project was situated within a broader disciplinary debate regarding the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) and concerning controversies as to the way in which to categorize symptoms of mental disorders. Autism in particular presents a contested diagnostic category, appearing clinically in a variety of forms and with varying professional understandings of its nature and appropriate treatments. The research network was concerned with this broader questioning of the very notion of autism as a singular disorder category and was critical of current diagnostic criteria and classification. Furthermore, the research network formed part of a shift in the clinic and the field more generally towards investigating mental disorders such as autism through laboratory practices and technologies like new IT-based cognitive function testing, electroencephalography (EEG), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The researchers’ work was exploratory, seeking to find new ways of understanding autism as both symptoms and pathology, e.g., through a key psychiatric concept of cognitive flexibility that was investigated as part of the project.

Although several of the projects within both of these research networks included industrial partners, the lead researchers themselves stressed that their research was “investigator-initiated” and thus different in nature from clinical trials and medical research driven by industry. The lead researchers themselves framed their research, the research designs and approaches, as “translational”, e.g., in presentations and funding applications (“translational forskning” in Danish).

Analytical framework

Science Studies, Feminist Theory, and Cultural Studies have explored empirically and theoretically the way in which discourse, statements, and representations have productive consequences and effects upon reality (Foucault, 1990; Haraway, 1988; Latour, 1987; Mol, 2002). In their book on economics, Mackenzie et al. (2007) develop the term performativity to examine how economic theory takes part in shaping economic realities—how statements, models, concepts, and formulas over time shape the very worlds they describe. These authors illustrate how reality—socially and materially—over time becomes reshaped to fit with theoretical models and inherent presumptions. This analytical lens is highly relevant for understanding how the language of TR has been, and continually is, an agent for modifying the reality it describes. This analytical lens also leads us to study how actors involved in TR research take part in the actualization and “putting into motion” of TR through their use of TR concepts, models, and research designs. This is the focus in the following analysis where significant examples and excerpts related to the use of TR terminology are presented and discussed. According to Mol (2002), conversations and interviews are a way of listening to informants as if they were their own ethnographers, telling how their work of TR is understood and carried out. Interviews and conversations are thus analyzed as a way of learning about objects, events, and practices that are material and productive.

Analysis

The analysis is organized according to four main understandings emerging from the data—TR as knowledge flow, TR as a political buzzword, TR as knowledge collaboration and exchange, and TR as competencies and skills. The quotes and excerpts are anonymized with regard to informant names and field of expertize and only attributed to the research network—named here as the autism and electroporation network, respectively. Throughout the analysis, the two networks also serve as analytical prisms for one another, juxtaposing their similarities and differences.

TR as knowledge flow from theory to practice

During the study, a dominant understanding of TR that appeared during observations, informal conversations, and interview questioning on the topic was TR as knowledge flow from theory to practice. This understanding aligns with the notion and modeling of TR that is pervasive in biomedical literature and the aforementioned bench to bedside trope. TR is conceived of as a set of transfers or flows of knowledge from basic biomedical research into clinical diagnosis and improved health for patients—and also concerns closing the gaps hindering this flow. This understanding was particularly prevalent in the electroporation network. A lead researcher involved in setting up laboratory studies, clinical trials, and implementation efforts in relation to the treatment technique electroporation explains her understanding of translational research to me in an interview:

It is about closing the gap between lab research and the patient’s everyday life. Moving knowledge from the laboratory over into clinical practice, as well as ensuring how we can take the biological tests that afterwards can go back to the researchers… moving from idea, to laboratory research, to clinical research and all the way into guidelines for new treatment. (Electroporation network)

This quote resonates with the dominant understanding of TR as knowledge that flows through a set of otherwise separate contexts and knowledge domains framed as laboratory, clinical practice (with associated guidelines), and the patient’s everyday life. She describes TR as the moving of laboratory research into clinical practice, and how TR also produces the biological data in the clinic to move back into the lab.

At a research event and presentation at the hospital, this researcher presents a timeline of her research on electroporation. She explains how she has been involved in the basic science in order to understand the cells and cell membranes and how they can be briefly destabilized by applying electrical pulses to the area. Based on these insights into cellular behavior, they developed new experimental electro-engineering tools for applying electricity directly to the skin and tumor and then for injecting drugs and chemicals into the area so these can enter into the tumor and cells creating a local and very effective new treatment form. These tools have subsequently been refined and developed and are part of standard treatment regimes for specific types of cancer, such as skin cancer. In addition, the technique and technology are being developed further for other types of cancers. For example, stomach and colon cancer, where the tumor is more difficult to access directly with electrodes. Here, the electrodes were undergoing further development in order for them to work with endoscopic devices.

In a timeline figure, a presentation slide sketches the steps of translation from basic science over into techniques tested on mice in order, for example, to refine how to administer the electricity and chemicals in an appropriate way and with the correct dosages. This led to further experimental treatments on patients, and later on, randomized trials with a larger number of patients proving both the safety and efficacy of this specific type of treatment. In 2013, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines state that sufficient evidence has been established for this particular treatment for cancer spreading in the skin. In conclusion, she notes that this process has been a relatively “rapid process of translation from the first discoveries to a treatment in widespread use.” She moves on to explain their more recent work on using calcium with this type of treatment to determine how this might have effects upon the immune system beyond the local effects of cancer cell death. The timeline and story of electroporation reiterates a temporal TR image of knowledge flow from theory to practice—and back again—over time.

When asked about definitions of the term translational, another researcher, part of the oncology research networks but involved in the study and treatment of other cancer types, similarly notes:

I think translational covers when we turn over basic science into practical science. I see it as research where we get out and onward from the lab. We have an aim that is out of the lab, and it is important for us to do something that potentially can get out and work in society. (Electroporation network)

This quote links up to an understanding of making science applicable and “something that can be used.” Other informants likewise recognized TR as the clinical application of theoretical or experimental knowledge—or “moving new knowledge closer to the clinic, so “it can be used and tested further.” One informant notes that TR in this way consists of a practical achievement that moves theory into clinical practice:

I define translational as the clinical application of theoretical or experimental knowledge. So translational science is that one translates, really a utilitarian term, that you translate something proven ex vivo or proven in a petri dish to something that has clinical consequences for patients.” (Electroporation network)

In the accounts recorded during the study, an understanding of TR as knowledge flow from theory to practice thus is in agreement with the dominant discourse in the literature and “promise of translation” envisioned in the future (Brown et al., 2000). The hope is that public investments in health science can and should be paid back in the form of improved care practice and improved public health. “Making a difference” was often mentioned as motivation for the career choice of working with translational hospital-based research, along with the value of participating in research that might be practically applicable to and an improvement of current clinical practice. This applicable-practice motivation was notable in both the electroporation and the autism network.

Following Mackenzie et al. (2007), the accounts and ideas also speak of actual practices where, in the electroporation network, knowledge artefacts, as well as biological material are relocated and exchanged. There are also accounts of how experimental research is connected to changing procedures for cancer treatment strategies and new standardized treatment programs.

TR as a political buzzword

Several of the informants in both research networks noted the buzzword character of the word, smiling or laughing at my question of their understanding in the interview thereby distancing themselves from the concept and instead locating the concept in a world of politics and funding bodies with interests different from their own. They reiterated statements resembling the objectives discussed above regarding knowledge flow and transfer, but then added that these ideas did not necessarily match the way TR projects actually played out according to their experience. A researcher from the autism network notes:

I know what it means, but that is not how I see it implemented. It is research that supposedly builds bridges between experimental research… over into clinical research, maybe back again. However, when I see translational programs implemented, it does not really get out to the patients, and it does not really get out into the clinic. (Autism network)

Several informants noted that the TR had a political buzzword quality and was about justifying funding for very specific types of research. Therefore, for some there was a discrepancy between the rhetoric of TR and the way it was realized in ongoing projects. Accounts such as the above imply a critical position—that the translational agenda is a way of living up to demands of funders or creating political enthusiasm for research—but that the actual move into clinic and patient benefits could be questioned.

One informant described TR as a specific kind of research funding to expand “the evidence base” rather than research enabling knowledge to flow between basic science and the clinic.

Really, a buzzword is about creating the funding to make the evidence. It is relatively inexpensive to fund the small, experimental studies but gets expensive when you want to test an intervention on a larger group. It is complicated to create the evidence to prove that this really should be part of the standard treatment plan. So it is a way of creating funding for this difficult phase, where promising research needs to create the evidence base for it to get used. (Electroporation network)

Here, TR is a way of creating political support for particular types of research funding—a way of filling an evidence gap that is necessary for something to be legitimate and justifiable as a diagnostic or treatment option in the clinic. Thus, in this understanding TR is understood as a rhetorical device serving particular interests and political agendas. This resonates with the political move to put significant resources into TR to increase the clinical relevance and application of research. Using research relies on the creation of very specific types of “robust” evidence such as randomized controlled trials—and these are a necessary intermediate stage for research findings to reach decision-makers and potentially have societal health impacts. So here, TR is about the political support for specific types of research, for creating particular research infrastructures that can enable credibility, validity, and paths of impacts for medical research.

Conversations and interviews where TR was referred to as a political buzzword can also be seen as part of the actors’ own reflections on a broader knowledge economy where colleagues, or they themselves, attempt to position themselves strategically in relation to political and funding agendas. They adhere to, draw on, but also smile at this—since what they see “play out” sometimes is a different scenario. The actors in both research networks involved were thus attentive to how one as a researcher strategically can link up to political agendas and adjust projects so they match the demands of policy and funding trends. Here, TR is pointed to as rhetorically powerful in justifying specific types of research resonating related analyses of how TR currently is mobilized in other national academic medical settings (Rushforth, 2016; Wilson-Kovacs and Hauskeller, 2012).

TR as interdisciplinary collaboration and exchange

A third understanding of TR that appeared in both networks was TR as a framing of interdisciplinary collaboration. Models and research designs of TR enabled and encouraged collaborations and exchanges across different medical specializations and across distinct departments and organizations. A researcher from the autism research network replies to the question of how she understands the term translational as follows:

I understand it broadly, that you try to connect knowledge and understanding from different levels—psychological, biological, social etc.—into a joint understanding of a phenomenon… The same phenomenon might really be the result of many different processes. (Autism network)

She moves on to explain how such processes can be captured at different levels and through different investigational methodologies deriving from different disciplines. Methods in her project included preclinical and clinical testing, neurobiological approaches, brain imaging, and at a later stage, if the funding becomes available, possibly also genetic testing. She explains that a translational approach is the next step in developing new knowledge on autism. Here, the promise of TR is to connect different knowledge forms to create radically new understandings.

The idea here is that the translational can dismantle diagnoses, as they are today. If we understand the translational levels, we will understand that the diagnostic system and the psychiatric system should be put together differently. (Autism network)

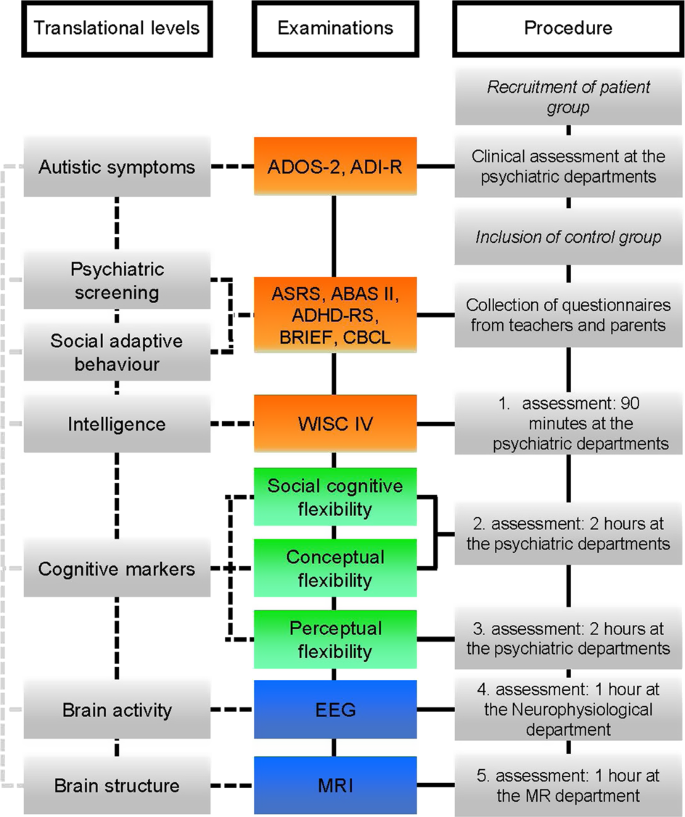

The research design of the autism project is therefore organized around a translational model that the lead researcher sketches for me on the whiteboard in her office, and later, after the interview, she sends me the model figure used in applications and when presenting the research (Fig. 1). Here, different translational levels are depicted along with the examinations, methods, and procedures applied to produce knowledge about these levels. The research project is designed around these translational levels through which the children included in the study move during a series of examinations marked in the figure as “assessments 1–5” under the column with procedures, ranging from standardized clinical screening tests and questionnaires, IT-based cognitive tests and paraclinical methods, including electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These methods provide knowledge on different translational levels from the “psychosocial down to something increasingly biologically based”, she explains.

The translational model was shared by an informant in the autism research network and derives from their project description. The model depicts different translational levels along with the examinations, methods, and procedures applied to produce knowledge about these levels. The research project is designed around these translational levels and a series of examinations marked in the figure as “assessments 1–5” under the column with procedures, ranging from standardized clinical screening tests and questionnaires, IT-based cognitive testing, electroencephalography (EEG) to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The model organizes the research project, the series of tests and examinations the patients and control subjects go through in which different kinds of technologies and expertize are involved. The tests take place in the childrens’ homes and in their school settings (using standardized questionnaires filled out by parents and teachers), in the psychiatric clinic (again using standardized screening and new cognitive tests developed as part of the project), in a neurobiology lab at the neurology department and at the department of medical imaging (where the MRI scanning technologies are located). The studies require personnel and expertize from these various disciplines in order to carry out the examinations and analyze the results. The autism research network thus spanned different departments and disciplinary specializations of child and youth psychiatry, psychology, psychophysiology, radiology, neurology, engineering, and screening software/IT development.

“It is like we take a cross-section and look at the same phenomenon at different levels”. (Autism network)

The translational research design brings together different methods and techniques for investigating many different parameters associated with autism. In this sense, the model of the translational research design can be seen as a workable boundary object (Star and Griesemer, 1989) enabling collaboration across a complex of scientific inquiry methods and knowledge forms into a joint workable research design. The model helps to make possible collaboration across specializations and departments and facilitates a joint study that combines approaches where autism is framed in different ways: as related to social, behavioral, and clinical symptoms, as a disease with a possible neurological basis, and as a disease with a possible brain structural basis. Through the translational research model, it becomes possible to relocate the phenomenon of autism into different disciplines and as such offers a tool towards collaboration. The language of TR in the autism network can thus be seen as a contact language enabling a joint interdisciplinary project to be planned and agreed upon (Galison, 1999).

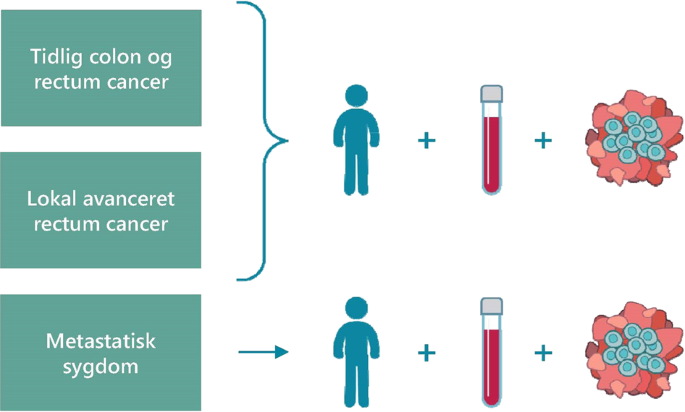

In the same way, projects within the electroporation network were framed and depicted in translational models and research designs. This network also involved collaboration between a range of disciplines and areas of expertize, requiring collaboration between researchers based in oncology, surgery, dermatology, pathology, biochemistry, molecular biology, immunology, physics, engineering, IT, and palliation. A model (Fig. 2) was used in a research presentation to depict and present a subproject taking place within this translational network. The project was set up as a collaboration between the oncology and surgery department at the Danish hospital and included several other partners such as universities, industry, and e.g., a leading immunological research institute in France working to develop new methods to characterize the immune characteristics of cancer tumors, “the cellular landscape of the tumor”. Like the model from the autism network, it looks “across” and combines different types of examination and methodologies in a new way.

The translational model was shared by an informant in the electropration research network and derives from their project description. The model depicts the translational set-up for the study and different methods for examination that include and “sum up” patient outcomes, blood samples, and tumor biopsies across different stages of cancer—early cancer (Tidlig colon og rectum cancer), advanced cancer (Lokal avanceret rectum cancer), and cancer that has spread in the body (Metastatisk sygdom).

One of the lead researchers explains the translational set-up for the study in which the patient is treated with calcium electroporation before the planned surgical removal of a cancer tumor. The treatment prior to surgery aims to stop the tumor growth and hinder spreading of the cancer. Blood samples and tumor biopsies are taken, and biological data is recorded before and after the surgery to assess the effect of the intervention. In the boxes on the left, the figure presents the different stages of cancer development to be examined—early cancer, advanced cancer, and cancer that has spread in the body (metastasized). The investigations then focus on three ways of “reading” the intervention. Firstly, what happens to the patients? Is it safe? How is the treatment experienced by the patient, e.g., pain? Are the side effects short term and long term? Does the tumor grow or spread (as seen and measured through imaging technologies)? Secondly, what happens as the result of this treatment at the molecular level in the tumor and in the blood, examined through tumor biopsy investigations and blood profiling testing before and after the treatment intervention? These different “readings” of the interventions’ effects are summed up (+). The researcher explains that this can be a new way of producing knowledge about the variation they find clinically, for example of how the same intervention works differently in two patients, by looking at the cellular level and the biological markers to explain and understand the variation and the immunological changes involved. Translation is a way of making the effects of an intervention visible and documentable, as a way of proving a link between treatment and specific effects. As such “translational” is a set of methods and tools that can be used to compare and evaluate treatments with the potentiality of providing a new and different kind of knowledge of what works, and sometimes how it works.

In the electroporation network, several researchers noted that the research is fragmented and separate (e.g., in relation to the different stages of cancers or in relation to different treatments before or after surgery). A researcher explains that not a lot of research focuses on all three phases, but that looking at the immune system as a whole rather than the tumor as an isolated entity to be treated or removed is often neglected. Looking at the effects of the treatment overall requires what he notes as a “helicopter view”. Another researcher in the project similarly refers to this work as grasping the “bigger picture”.

It is about designing the study so you see the bigger picture and get a 360-degree view… If you want to make a difference and do research that moves the way we think, then you have to include all the parts and include the whole spectrum. (Electroporation network)

Ideally, for example, results from patient-reported outcomes, molecular biological examinations of blood samples and immunological investigations of tumor material are linked up in the research project—as are different stages of cancer and phases of cancer treatment like pre, during, and post operation, thereby encompassing the “whole spectrum” by working across disciplines and joining differing techniques and niches of research. For both networks, bringing together these different investigational techniques and methods was where the research had the break-through potential to be a “game changer”, as one researcher puts it—in the sense of a new way of thinking about cancer or an entirely new approach to psychiatric diagnosis. This is where there is a promise and potential to change the foundations for existing classifications, diagnostics, and treatment strategies of illnesses. In both networks, TR is a productive and adaptable way of framing interdisciplinary research and multifaceted research problems. TR holds a promise of not only creating usefulness of research, but also of changing fundamental paradigms of both clinical research and practice.

TR as competencies and skills

A final and fourth understanding reappearing in the data material is TR as competencies and skills. When explaining their TR understandings and research activities it was often noted by the informants that such work required a set of specific competencies and skills. This concerned the ability to develop and use translational tools and methodologies in the research project and at the hospital. In the excerpt below, a lead researcher stresses the aspect of “ability to use”:

“To me, translation is the ability to have a tool to translate an effect of something, a clinical intervention, a clinical problem—to be able to translate that into an effect on the genetic, cellular, or molecular level. So translation to me is using that methodology, that method, to find an effect of something that happens clinically.” (Electroporation network)

As part of the electroporation study, Ph.D. students and young researchers went abroad and participated in research courses, seminars and visits—one in an electro-engineering institute in Slovenia to learn the electrophysics behind the technique, the other in an immunology laboratory in France to learn how to measure immune cells in the tumor with a novel prognostic technique. These kinds of exchanges were vital to developing the skills necessary to realize the TR objectives of the project. One of the Ph.D. students explains this as somewhat different from other kinds of clinical research at the department.

When you are a researcher at a hospital, you stand there with your patient, and then you send off your tests, I have heard jokes about this in the lab, you send off your tests into a black box, and we get a bunch of numbers back. I would like to go into that black box and see what happens, to understand how the tests are practically handled in the lab, because I think that the very numbers I get out of that black box, well I will to a greater degree understand them, if I have been there in the lab, where I see it and have it in my hands. (Electroporation network)

In this quote, the physician in research training points to her own movement between research located in a clinic and in a laboratory. Part of her research plan is to move into the laboratory and acquire the skills to understand laboratory-based analysis, results and possibilities. In order to gain these skills and competencies, and apply them to the clinical focus of her research, she notes how it is necessary to physically “move into the black box” and “have it in my hands”. As such, her training involves a shift from more “traditional” medical research into a new kind of translational research.

Another team member in the project has a background in human biology. She has been hired to support the translational research at the department and highlights that it is the exchanges between the different professional groups in the project that are so necessary and where we “really make the most of the knowledge we have”. She explains her mediating work and role and how her educational background in human biology has equipped her to be a clinical research biologist.

It is really about understanding a little bit of everybody else’s areas or field, so you can be precisely that link between chemists, physicists, and doctors. (Electroporation network)

In the electroporation network, a TR research agenda was thus closely linked with recruiting or educating the “TR agents” that could facilitate research activities and exchanges across disciplinary boundaries. A crucial supporting aim of the TR networks was thus to develop these skills in house—at the department and at the hospital, rendering the opportunities in the technologies and the lab more accessible.

Likewise, Ph.D. students in the autism network were trained thoroughly in the working of the neuro-lab by experts at the hospital and from abroad, setting up and using the physical equipment for carrying out EEG examinations, as well as the technologies and software involved in data analysis of the EEG results. As noted by one of the Ph.D. students, this was really a very different set of “much more technical skills” than those he was trained in as medical doctor in child and youth psychiatry. A key participant in the autism network was for example a trained psychologist and had experience from a previous job with MRI brain scanning techniques. His expertize in both child and youth psychiatry and imaging technologies made it possible to connect the psychiatric research interests with possibilities in the MRI devices for testing and analysis. He could speak the necessary highly specialized language related to diagnostic imaging, such as multi-slicing, pulse-sequences, and fiber tracking etc. He enabled the interactions and exchanges among the psychiatrists and the MRI engineer and imaging professor. Such ability to apply new methodologies across disciplines and to converse and move expertly across more than one discipline is thus a fourth way in which the discourse and promise of translation was embedded within the practices of both research networks.

Discussion

This article has presented and explored different uses of the TR terminology in two specific settings of biomedical clinic-academic work practices. This type of inquiry is underexplored in the literature, and this empirical contribution thus adds to related efforts into studying how the actors in the field respond to political agendas of TR and changes in the biomedical research-clinic landscapes (Rushforth, 2016; Vignola-Gagne, 2014; Wilson-Kovacs and Hauskeller, 2012). The analysis has put forth a set of performative statements on TR along with the models of translation presented by these actors. Here we see how TR is embedded in the practices and perspectives of a set of particular actors involved in TR.

The first characterization of TR as knowledge flow can be viewed as an adaptation of the normative language of TR debates and policies. The goal and value of bench to bedside work enters into the actors’ own characterizations and meaning-making of their everyday work—as it also productively shapes and organizes these practices. Researchers involved in TR take on and seek to fulfill expectations and visions of the TR discourse and assumptions that circulate among funders, evaluators, management, and in health care prioritization and politics. TR also becomes part of the actors’ own sense-making and vision of how value can be created through their work for patients and for society. This brings our attention to how actors involved in carrying out TR take part in actualizing and putting into motion theories, models, and the very propositions of TR. This characterization places positive value upon specific kinds of work in the hospitals and among the hospital-based researchers. Translational research work that can ensure that research results are used, integrated into practice, and can produce benefits for patients and society is thus also characterized and performed as desirable and good.

The second characterization points to the critical position of TR as associated with a political agenda and something that can be used strategically to secure funding. TR offers an opportunity for researchers to position themselves advantageously in relation to TR policy and funding—thus potentially gaining a privileged professional status as key leaders of change, as noted in related studies (Vignola-Gagne, 2014; Wainwright and Williams, 2009; Wilson-Kovacs and Hauskeller, 2012). The researchers themselves take part in critically reflecting upon political agendas, funding flows and the consequences for their work, their career, and their field of expertize. They thus participate in questioning the very promises and hopes of the TR dominant discourse and the transformations they experience.

In the third characterization presented here, TR as collaboration and exchange, TR becomes a way of seeing and analyzing the subject matter across disciplinary divides. As such, the translational research design combines several different investigational methodologies from different and otherwise somewhat distinct disciplines. In the terms of Latour, these techniques mediate the object studied in different ways, rendering it visible for science in particular ways (Latour, 1987), and these different mediations are brought together in the promise of “seeing the bigger picture”—and “changing the game” in radical ways. TR discourse and promises become an organizing factor for research and research activities in the hospital studied. TR serves to facilitate epistemological boundary spanning (Evans and Scarbrough, 2014) and is a productive way of framing interdisciplinary research and multifaceted research problems that cannot be solved with traditional research frameworks. In this understanding TR perhaps opens for alternative ways of creating medical knowledge and evidence other than—or in combination with—the gold standard of randomized controlled trials (Timmermans and Berg, 2003; Wieringa et al., 2017).

Lastly, TR is closely linked to the building and expanding of interdisciplinary and transactional skills in the hospital setting studied. This is discussed under the fourth characterization, TR as competencies and skills. This theme highlights the integration of new knowledge forms into the hospital research setting, as well as the very practical, material, and embodied abilities of TR such as handling the equipment, delivering the electric pulses to the tumor areas as in electroporation, and learning to administer the details of the EEG equipment and devices. New skills must be learned and entered into clinical practice and experimentation. Likewise, medically trained employees move into the lab and learn to work with the biopsies, blood samples, and cells “in their hands”. Scientific investigation of cancers and autism is shifted out of the clinic into the laboratories of for example neurobiology and brain imaging—and the techniques and skills from these disciplines are relocated into clinical and medical practice and achieve new value here.

With the presentation of these four understandings, this article illustrates different uses of the term TR among actors engaged in research-clinic activities in two settings, that of clinical oncology and that of clinical psychiatry. The analysis presented in this article does, of course, not cover all the ways in which actors involved in TR use the term. Rather it illustrates some specific, situated uses—uses that reappeared and were focal in the data material produced in this study. The analysis provides new insights into TR as a”force of example” (Flyvbjerg, 2006). Rather than providing a total overview or mapping generalized patterns, the analysis explores specific context-dependent appearances of TR. The study brings out differences and connections for further juxtaposition to other studies in different specializations in different national contexts. It is important to note that the characterizations were not mutually exclusive, but overlapping and entangled in the setting studied. The understandings were mobilized, in turn, to bring out different aspects and values of the hospital-based research work in specific situations. All characterizations circulated in both networks—thus seemingly co-existing within these networks, as well as sometimes in the course of a single interview.

Notable are however also some of the differences in the two research networks. The networks were not analyzed as comparative cases (several cases of the same), but selected due to differences and analyzed in juxtaposition to bring out differences. In the electroporation network, the dominant understanding of TR as knowledge flow was more prevalent than in the autism network. In the electroporation network TR as knowlegde flow appeared as the primary understanding of the term and also as an important guiding rationale of conducting hospital-based translational research. This might be linked to the ways in which the field of cancer research historically has been tied to the political and funding agenda of TR. Historical studies have analyzed how the rise of translational research and a translational agenda, particularly in the US, is closely linked to cancer research and to the promise of cancer cures based on research into new drugs and treatment therapies (Fujimura, 1996; Keating and Cambrosio, 2012; Löwy, 1996). All early publications 1992–1997 using the term are also related to cancer research, in particular research on biomarkers in relation to cancer prevention and the establishment of tissue banks and cancer research centers in this period (van der Laan and Boenink, 2015). Historically, TR in this version seems more closely linked to the electroporation network than to that of psychiatry—where the understanding of TR as collaboration and exchange was foregrounded more often. These differences bring our attention to the ways in which TR is situated differently in different disciplines and underscores the contextual nature of the concept.

Conclusion

This article has presented selected findings from an ethnographic study of the everyday practices of TR in a specific setting. The discourse of TR, including the policy initiatives and organizational transformations linked to the TR discourse, can be seen as a paradigmatic shift in medical science. Yet little is known about how such a paradigm shift plays out in concrete settings, what it means to the actors involved, how it changes what constitutes meaningful and valuable research—as well as meaningful and valuable everyday work practices. This article proposes that actors take part in performing the emergence of TR and possible paradigm shifts by foregrounding and valuing specific versions of TR along with specific practices, specific skills. This entails that other practices and skills perhaps are backgrounded and become less visible and less valued. That which the less visible and less-valued practices are composed of (e.g., perspectives of patients or other working groups at the hospitals) constitutes a pressing question for further work beyond the scope of this paper. One of the important points highlighted here is the different ways in which TR discourses, promises, and expectations form an active part of the researchers’ sense-making and practices. The analysis presented in this article also allows us to reflect on how these actors take part in fulfilling a societal obligation, encouraging and improving the clinical application and clinical benefit of new scientific knowledge. They share the concerns found in the TR debates and policy regarding the closing of a “bench-to-bedside gap”, but also rework these orientations in relation to their specific projects and practices. Applying the notion of performativity, statements and models of TR have been approached in the light of their agency and their performative dimension. This analytical approach thus helps to understand how TR characterizations—and statements—also contain a prescription for how the world must change for them to become true. Mackenzie et.al. suggest that performative success is when there is created both a new language and theory, as well as new reality (2007). This article provides insights into four co-existing characterizations where such performative success was achieved in the setting studied. The analysis also points to a disciplinary difference through the juxtaposition of two different research networks. New languages, theories and realities were successfully in the making in these networks along with changing implications for the way in which research knowledge is produced and applied, as well as cultural shifts in what constitutes good and valuable research. In conclusion, this performative lens is proposed as a potential step forward toward developing a social science and humanities understanding of TR, how usefulness of research is characterized and realized through practice while keeping in sight the complexity and materiality of such processes.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the content and the use/consent agreed with informants. Selected anonymized extracts and summaries are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and signing of a MOU to ensure the ethical use of data.

References

Brown N, Rappert B, Webster A (2000) Contested futures: a sociology of prospective techno-science. Ashgate, Farnham

Clarke AE (2005) Situational analysis: grounded theory after the postmodern turn. Sage Publications, California

Crabu S (2018) Rethinking biomedicine in the age of translational research: organisational, professional, and epistemic encounters. Sociology Compass. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12623

Evans S, Scarbrough, H (2014) Supporting knowledge translation through collaborative translational research initiatives: “bridging” versus “blurring” boundary-spanning approaches in the UK CLAHRC initiative. Soc Sci Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.025

Flyvbjerg B (2006) Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual Inq. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

Foucault M (1990) The history of sexuality. Volume 1, An introduction. Vintage, New York

Fujimura JH (1996) Crafting science. a sociohistory of the quest for the genetics of cancer. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Galison P (1999) Trading Zone-coordinating action and belief. In: Biagolo M (ed) The Science Studies Reader. Abingdon-on-Thames, Routledge, pp. 137–160

Greenhalgh T, Wieringa S (2011) Is it time to drop the ‘knowledge translation’ metaphor? A critical literature review. J R Soc Med. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2011.110285

Haraway D (1988) Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Fem Stud. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

Keating P, Cambrosio A (2012) Cancer on trial: oncology as a new style of practice. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Krüger AK, Hendriks B, Gauch S (2018) The multiple meanings of translational research. negotiating medical science. https://doi.org/10.31235/OSF.IO/W6XJN

Lander B, Atkinson-Grosjean, J (2011) Translational science and the hidden research system in universities and academic hospitals: a case study. Soc Sci Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.019

Latour B (1987) Science in action: how to follow scientists and engineers through society. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Lewis J, Hughes J, Atkinson P (2014) Relocation, realignment and standardisation: circuits of translation in Huntington’s disease. Soc Theor Health. https://doi.org/10.1057/sth.2014.13

Löwy I (1996) Between bench and bedside: science, healing, and interleukin-2 in a cancer ward. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Mackenzie D, Muniesa F, Siu L (2007) Do economists make markets. Do economists make markets? On the Performativity of Economics. Princeton University Press, New Jersey. https://doi.org/10.1086/597458

Mol A (2002) The body multiple: ontology in medical practice. Duke University Press, Durham

Rushforth A (2016) What’s in a slogan? Translational science and the rhetorical work of cancer researchers in a UK university. Nord J Sci Technol Stud. https://doi.org/10.5324/njsts.v4i1.2170

Star SL, Griesemer JR (1989) Institutional ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39. Soc Stud Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631289019003001

Timmermans S, Berg M (2003) The gold standard: the challenge of evidence-based medicine and standardization in health care. Temple University Press, Philadephia

van der Laan AL, Boenink M (2015). Beyond bench and bedside: disentangling the concept of translational research. Health Care Analysis: HCA: J Health Philos Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-012-0236-x

Vignola-Gagne E (2014) Argumentative practices in science, technology and innovation policy: the case of clinician-scientists and translational research. Sci Pub Policy. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/sct039

Wainwright S, Williams C (2009) Stem cells, translational research and the sociology of science. In: Atkinson P, Glasner P, Lock M. Handbook of genetics and society: mapping the new genomic era. Routledge, Abingdon-on-Thames, pp. 41–58

Wieringa S, Engebretsen E, Heggen K, Greenhalgh T (2017) Has evidence-based medicine ever been modern? A Latour-inspired understanding of a changing EBM. J Eval Clin Practice. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12752

Wilson-Kovacs DM, Hauskeller C (2012) The clinician-scientist: professional dynamics in clinical stem cell research. Sociol Health Illn. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01389.x

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Data and Development Support, Region Zealand, and hosted by Department of People and Technology, Roskilde University. The study was carried out with support and supervision from Jesper Grarup, Peter Kjær, and the two research groups Health Promotion Research and Dialogical Communication at Roskilde University. Special thanks are also extended to the participants in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Strand, D.L. Everyday characterizations of translational research: researchers’ own use of terminology and models in medical research and practice. Palgrave Commun 6, 110 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0489-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0489-1