Abstract

NATO burden sharing is currently hotly contested. While it has been measured at the political, economic, and military levels and being looked at from the input and output side, the most commonly used variable to measure NATO BS is considering the percentage of GDP that a country spends on defense, which NATO agreed upon in 2014 should be 2%. The aim of this article is twofold. First, we review the most commonly used system- and state-level variables to explain burden sharing behavior and to carve out their explanatory limitations due to their strong rationality assumptions, positivist epistemologies, deductive, hypothesis testing research designs, and methodological individualism. The gap in the burden sharing literature currently is that it is unable to explain why a particular burden sharing behavior exists (i.e., free-riding) and why it occurred (or not) at a particular point in time. Our second aim is to make suggestions on how to fill these gaps by offering a selective number of post-positivist theories to study NATO burden sharing. We argue that we need to unravel the BS logics and social mechanisms that underpin BS decisions and behaviors, and hypothesize that states may, for example, not exclusively be informed in their burden sharing behavior by a logic of consequentiality but one of appropriateness. However, in order to gain access to this logic and social mechanisms, we need to employ post-positivist theories (and thus methodologies).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the birth of NATO in 1949 politicians and academics alike have debated how to fairly share the organization’s collective burdens (Lundestad, 1998, 2003; Sloan, 2016). Burden sharing (BS) is commonly defined as the “actual contribution of each nation to collective defense and the fairness of each state’s contribution” (Hartley and Sandler, 1999: p. 669). More specifically, as Cimbala and Forster note, it is “the distribution of costs and risks among members of a group in the process of accomplishing a common goal. The risks may be economic, political, military or other” (2010: p.1). BS thus occurs in collective action situations where individuals or a group of states want to achieve a common purpose. BS costs are, for example, incurred for maintaining military forces and their equipment, deploying the armed forces as necessary in combat or peace operations, as well as military and political command structures. These costs have to be shared somehow among the allies to achieve distributive justice. In that sense, BS is the division between receiving the benefits from a collective action and, as Olson notes, “the willingness to pay for this action” (1965: p. 21).

To be sure, assessing or even measuring BS is not an easy task, neither analytically nor politically, which explains perhaps why BS debates at times have been loud, flamboyant, vulgar, tasteless, or even hostile. While it has been measured at the politicalFootnote 1, economicFootnote 2, and militaryFootnote 3 levels (Cimbala and Forster, 2010) focusing on input and output elements, the most commonly used variable to measure NATO BS is considering the percentage of GDP that a country spends on defense, which clearly focusses on the input side. In 2014 the alliance has set 2% as the desirable target in this regard. Currently only fiveFootnote 4 out of the 29 member states have met this target. Unsurprisingly, this 2% target is not without contestation.

One of the latest iteration of a strong political contestation on NATO BS emerged with the candidacy of Donald Trump as President of the United States. During an editorial meeting with the New York Times on the campaign trail, he rumbled that

I’ll tell you the problems I have with NATO. No. 1, we pay far too much. We are spending—you know, in fact, they’re [the Europeans]even making it so the percentages are greater. NATO is unfair, economically, to us, to the United States. Because it really helps them more so than the United States, and we pay a disproportionate share. Now, I’m a person that—you notice I talk about economics quite a bit, in these military situations, because it is about economics, because we don’t have money anymore because we’ve been taking care of so many people in so many different forms that we don’t have money—and countries, and countries. So NATO is something that at the time was excellent. Today, it has to be changed. It has to be changed to include terror. It has to be changed from the standpoint of cost because the United States bears far too much of the cost of NATO (New York Times, 2016).Footnote 5

To be sure and to put this statement BS into perspective, President Trump has not been the only U.S. politician who complained about the Europeans not paying enough for NATO and considering BS in the traditional financial-military paradigm—that is how much of a percentage each state spends of its GDP on defense. He is also not the first politician to consider other allies’ BS behavior independent of the American’s. This is called “zero conjectural variation”, which denotes a situation whereby other’s contributions are never considered sufficient (Cornes and Sandler, 1984: p. 367). Former U.S. Secretary of Defense, Robert Gates also reminded NATO allies in his farewell speech in 2011 that

In the past, I’ve worried openly about NATO turning into a two-tiered alliance: Between members who specialize in ‘‘soft’’ humanitarian, development, peacekeeping, and talking tasks, and those conducting the “hard” combat missions. Between those willing and able to pay the price and bear the burdens of alliance commitments, and those who enjoy the benefits of NATO membership—be they security guarantees or headquarters billets—but don’t want to share the risks and the costs. This is no longer a hypothetical worry. We are there today. And it is unacceptable. […] For all but a handful of allies, defense budgets—in absolute terms, as a share of economic output—have been chronically starved for adequate funding for a long time, with the shortfalls compounding on themselves each year (Gates, 2011).Footnote 6

We could go through the history of NATO back to 1949 to find many more examples of BS disagreements (see Thies, 2003). But we want to turn our attention now to contestations and debates in the academy instead (Axelrod, 1984; Barnett and Levy, 1991; Bennett et al., 1994; Betts, 2003; Boyer, 1993; Duffield, 1996; Gilpin, 1981; Grieco, 1988; Hurrell, 2007; Keohane, 1988; Kimball, 2010; Kreps, 2010; Kupchan, 1988; March and Olsen, 2004; Palmer, 1990; Ringsmose, 2010; Snyder, 1997, 2002; Walt, 1987). While we synthesize that debate in greater detail in the next section it suffices here to note their main methodological characteristics: strong rationality assumptions, positivist epistemologies, deductive, hypothesis testing research designs, and methodological individualism that limits researchers to primarily make inferences from the statistical analysis (for one of the latest examples see Sandler and Shimitzu, 2014). Such strong methodological preferences clearly have some benefits in terms of being able to aggregate a large number of data across time and member states in order to easily establish patterns of burden sharing.

At the same time, however, this reductionism also comes with limitations: contemporary burden sharing studies are mostly ontologically static, show limited agency, and treat burden sharing as an outcome rather than as a social process or even practice. Especially the latter point is important because as we know, for example from Constructivist theories in the field of International Relations (IR), intersubjective meanings, social forces, or norms, beliefs, or values can indeed affect behavior reflexively (Keck and Sikking, 1998). Moreover, we also know close to nothing about the influence of social representations and power structures on BS behaviors or BS decision maker’s interpretations of ‘‘burden’’, ‘‘fairness’’, and ‘‘justice’’, also vis-à-vis others. In short, the gap in the burden sharing literature clearly is that rationalist and positivist studies explain very little on why a particular BS practice exists (i.e., free-riding) and why it occurred (or not) at a particular point in time.

The aim of this review article is twofold: (1) first we want to review the most pertinent theories of NATO burden sharing and carve out the gaps in the literature in order to, in a second step, (2) make suggestions on how to fill these gaps by offering a selective number of post-positivist theories to the BS research program. We argue that we need to unravel the BS logics and social mechanisms that underpin BS decisions and behaviors. Why? Because they also allow us to gain access to the value-rational as well as instrumentally rational motivations informing states (Foucault and Mérand, 2012). We might hypothesize, for example, that states may not exclusively be informed in their BS decisions by a logic of consequentiality but one of appropriateness (see March and Olsen, 2004). However, in order to gain access to this logic and social mechanism, we need to employ a different set of theories (and thus methodologies) for the analysis that we discuss in the next section. More concretely, we suggest that the BS research program would benefit from a post-positivist turn, combined with a non-materialistic (or social) ontology. This would allow us to gain a better understanding of (1) how states define NATO’s public goods; (2) how collective burdens are perceived and constructed domestically; (3) what meaning states assign to the burdens and in what particular institutional context (Geertz, 1973: p. 5); (4) what value-rational motivations drive states’ burden sharing behavior (Zyla, 2015, 2016); (5) their normative predispositions towards burden sharing; and (6) how NATO burdens are negotiated and traded in the alliance.

To be clear, we are not suggesting that processes and practices of NATO burden sharing are always positive or unifying. Indeed, they can be highly divisive, as the two quotes above by President Trump and Secretary Gates underline. However, we contend that identifying and explaining the sources of such divisiveness on common standards of burden sharing fairness at the political level is not only a valuable contribution to NATO scholarship; it is also a theoretical contribution and allows us to better conceptualize and understand the divisive perceptions of fairness; how processes of allied learning, norm building, socialization, and community building take place; and, from an IR theory perspective, whether processes of social construction can facilitate or prevent the resolution of BS as a collective action problem.

We argue that while current NATO BS studies emphasize economic or military inputs, a post-positivist NATO BS research agenda would considerably broaden this undoubtedly narrow understanding of BS by showing that, first, the public good of collective defense is no longer focused exclusively on economic and military measures, and thus should include social, political, or geographic elements as well. Second, studying BS inductively by inquiring about the motivations and preference building of BS actors moves discussions of NATO BS from commitments agreed to by NATO members to the political level where BS practices, agreements, and understandings of fairness are highly contested. Again, the two quotes above by President Trump and Secretary of Defense Gates are exemplary here.

However, having just juxtaposed positivist versus post-positivists epistemologies above we are not suggesting that one is superior to the other, that the latter provides deeper explanations, or that we should entirely disregard positivist BS scholarship. Moreover, as we show below, positivist and post-positivist researchers disagree on the dependent variable, namely what burden sharing is: positivists treat BS as an outcome, post-positivists as a process or practice (Neumann, 2002; Pouliot, 2010; Schatzki et al., 2001). It is, therefore, difficult to judge which of their respective explanations is ‘‘better’’ or ‘‘superior’’, and would most likely not push the NATO BS literature forward.

Before we move ahead with our discussions, it is imperative to define some key terms that are used throughout the article in order to avoid any confusion or misunderstandings. We use the term rationalism to signify key ontological assumptions of rational choice theorists who assume that actors (states, individuals, organizations etc.) are utility maximizers. It follows that they only pursue their self-interests, which are calculated based on strict cost-benefits computations, and that those interests are complete, stable, and transitive (Gerring, 2012: p. 434).

Often, positivism is rationalist’s epistemological bedfellow. It is the belief that true knowledge can only be based on observable facts—that is that science must be falsifiable, objective, systematic and logically unified (Ayer, 2001). It aims to deduce generalizations to make predictions of future behavior. This is to be done by developing a theory or hypothesis that yields valid predictions about future phenomena. Natural laws provide causality. Consequently, metaphysical specializations or norms are to be disregarded. Instead, experimental or quasi-experimental research designs are employed and provide a deductive logic combined with quantitative research methods. In the case of NATO BS, often these include statistical calculations (e.g., regression analyses) to infer causal relationships and to develop parsimonious models that are general in scope.

The so-called interpretative (or post-positivist) turn in the late 1980s and early 1990s in the field of international relations introduced an epistemological shift from positivism to post-positivism. The latter emphasizes that the rules, actors, and identities prevalent in the international system are ‘‘socially constructed.’’ They are founded in a process of interaction and production of meaning between relevant actors (e.g., see Wendt, 1999; Hopf, 2002; Campbell, 1992). Accordingly, scholars prefer to use methods that can capture and interpret these processes of social constructions (through e.g., discourse analysis, see (Waever, 2002; Larsen, 1997)).

The term interpretivism is borrowed from hermeneutics and loosely denotes the study of human meanings and intentions. The purpose of this approach is to understand the meanings humans assign to their behavior and themselves vis-à-vis other actors. Their interpretation and development of norms, beliefs, and values are important factors for understanding social behavior. To simplify, this school concentrates on cause-effect relations rather than effect-cause relationships.

The remainder of this article discusses first the conventional system and state level variables that explain BS behavior. What follows in section three is a discussion on how individual level variables could advance our understanding of NATO BS behavior. The last section elucidates on some methods of how to operationalize these individual level variables practically, without claiming comprehensiveness.

International system and the state level variables

System level theories

The purpose of this section is not to provide a fully comprehensive literature review on NATO BS.Footnote 7 Rather, the objective here is to review out some of the perhaps most pertinent and influential segments of that literature in order to advance, in a subsequent step, the argument that the BS research program needs a post-positivist turn. Instead of discussing each theory and its ontological and epistemological assumptions one after the other, we decided to ‘‘cluster’’ our discussion in terms of overarching themes and identifying a selected number of variables. In this section we start with international system and state level variables; in the next section, we focus on variables at the individual level.

For Realists in the field of International Relations burden sharing behavior is decided by the polarity in the international system as well as the distribution of power in that system.Footnote 8 Without a world government, states need to think about how to align themselves with other states (Claude, 1962; Morgenthau, 1948, Waltz, 1979; Walt, 1987), and thus the distribution of material power resources is an important aspect for why states decide to share collective NATO burdens (e.g., balance of power or threats); it also affects the effectiveness and persistence of the BS regime over time (Brown et al., 1995; Buzan et al., 1993; Oye, 1986). This is a key independent variable to explain alliance politics. Specifically, balancing refers to weaker states joining either a stronger power or a coalition of powers (alliances) to address the threat. It also prescribes a hierarchy of international politics with a limited number of great powers dominating the international system while middle or small powers either balance or bandwagon ((Walt, 1987) reminds us that states usually balance and rarely bandwagon).Footnote 9 What follows is that states share alliance burdens because they are concerned about their own security and survival (Waltz, 1979).

In terms of alliance management (e.g., inter-alliance bargaining over military planning, costs and financing, preparedness, and coordination in a crisis), this power-based logic suggests that an ally with large military capabilities is able to provide a surplus of material assets to the collective cause while less militarily capable states are expected to enjoy the alliance’s public good without much paying for it (free-ride) (Snyder, 1997). Put differently, the distribution of alliance benefits, as the sociological-psychological literature on coalition theories charges, is the result of relative capabilities of states (Caplow, 1968). Moreover, allies that value the alliance the least or have better alternatives are more inclined to lobby others for stronger alliance commitments or offer some side-payments. Such a view also provides IR scholars with a clear idea of what units of analysis are worth examining (or not), namely major powers, and unless middle powers are engaged in serious balancing activities or show revisionist ambitions in the international system, they are, analytically speaking, irrelevant (Wight, 1973, 1977; Wight et al., 1978).Footnote 10

Using a similar ontology and logic, rational institutionalism (Ostrom, 1998: p. 1; Shepsle, 2008) considers NATO as an institution that provides a public goods (Olson 1965, Olson and Zeckhauser, 1966) or collectively consumes a good or service (Buchanan, 2008) (i.e., peace, order, stability; Shepsle, 2008: p. 4). Samuelson (1954) contends that if the public good is pure (Samuelson, 1954), then its benefits are expected to be non-rival and non-exclusive, which characterizes a condition in which a unit of the public good could be consumed by a state without diminishing the availability of the good (and thus its benefits) for consumption by others. In turn, the benefits of the public good are non-excludable if they cannot be withheld by the good’s provider (Sandler and Hartley, 1999: p. 29). Thus, denying an ally to consume the public good is not feasible unless side-payments or coercion is applied. The smaller the alliance, the greater the likelihood is that states actually contribute to the collective cause (Olson and Zeckhauser, 1966: 49f; see also Wolfers, 1962). In short, wo hypotheses are put forward by public choice theorists: First, powerful states shoulder disproportionately more of the collective burden (Sandler and Hartley, 1995), which foreign policy analysts used to link the level of national defense spending and burden sharing (Oneal, 1990a, 1990b, Oneal and Elrod, 1989). Second, due to alliance power imbalances, there is a systematic tendency of free-riding (or exploitation) in the collective action game, which occurs when non-payers of the public good continue to enjoy its benefits, and thus negatively affect the collective welfare of the alliance. Third, the joint-product model shows that alliances produce both public and private goods (Sandler and Hartley, 1999: 34ff.; Golden, 1983; Boyer, 1993: p. 14). The good becomes impure when private benefits are paid to alliance members (Ibid., 2001). Based on this, theorists hypothesized that allies who value the public good the most shoulder the largest burdens (Gilpin, 1987; Thies, 2003); those that do not are expected free-ride. Moreover, they have an incentive to not reveal their preference for the good and conceal the value they attach to it.Footnote 11

State level theories

Liberal IR theorists point out that states are not unitary actors but highly decentralized and fragmented entities (Keohane, 1984). They are composed of different societal groups and actors, all of which are expected to hold different BS preferences. That is to say that states represent societal preferences through institutions that are themselves consistently engaged with processing the demands and interests of societal groupings. Indeed, as Moravcsik reminds us, they are considered exogenous causes of the interests of states: “[…] the state is not an actor but a representative institution, constantly subject to capture and recapture, construction and reconstruction, by coalitions of social actors” (, p. 163). In other words, institutions process the interplay and exchanges of particularistic material and ideational interests of societal actors (see also Keohane, 1984, 1989). They are the transmission-belts in the exchange and competition for political ideas. The ends of this transmission process can be called ‘‘state preferences.’’ Such perspective allows us to define, which social actors or groups influence the preferences (or national interests) of states (see also Barnett and Levy, 1991; Bennett et al., 1994; Betts, 2003, 2009; Boyer, 1993; Davidson, 2011; Kreps, 2010; Kupchan, 1988; Levy and Barnett, 1991; Palmer, 1990; Thielemann, 2003). To be sure, BS preferences (or interests) are analytically different from strategies or strategic settings. Actors are believed to have preferences for outcomes (i.e., security, wealth, peace), which leads them to pursue strategies on BS, namely to calculate the means to achieve ends (Frieden, 1999: p. 40–7).Footnote 12

Moreover, actors might rank their preferences and form strategies to achieve them contingent on the environment they are embedded in (Frieden, 1999: p. 45).Footnote 13 Thereby a process of exchanging those societal interests and pressures determines, which of these preferences is most likely to influence BS choices (s.f. Petersson and Matlary, 2013; Hynek and Marton, 2011). Also, while state preferences are distributed across national boundaries, they naturally impose costs and/or benefits for other states and non-state actors. In this bargaining process, three outcomes are likely: negotiating for zero-sum game preferences, overlapping preferences, or mixed preferences.Footnote 14 However, particularly for neo-liberal theorists it does not automatically follow that the distribution of gains among allies must necessarily be equal. Indeed, the importance of relative gains can be conditional. Rather than asking whether relative gains are important, the better question to ask is under what conditions distributional gains might occur (Keohane and Martin, 1995: pp. 44–45).

In other words, (neo)liberal theories contend that the relationship between state and society—that is the domestic as well as trans-national society—is an important variable for explaining burden sharing behavior. Neo-liberal institutionalists in particular emphasize the role of international regimes in helping states to realize common interests (Keohane, 1984). Moreover, mutual interests among states can facilitate cooperation and the growth of international regimes (Young, 1989: p. 200; Keohane, 1984, 1989; Baldwin, 1993; Grieco, 1988; Snidal, 1991; Stein, 1990). A wide distribution of information provides transparency across the membership of the institution and reduces the influence of external factors such as emotions, fear and suspicion, or the threat of cheating that could destabilize relations (s.f. Baldwin, 1993; Grieco, 1988; Keohane, 1989; Powell, 1991; Snidal, 1991; Stein, 1990). Having said all this and much like international system theorists, domestic level theories heavily rely on rational choice models in their theorizing treating actors’ preferences and identities as exogenously given rather than being perhaps affected by rule-governed practices or the institutions themselves.

Since the end of the Cold War, however, neo-liberal theorists have been at the forefront of calls for a more productive dialog between international relations and international law. While states are treated as rational egoists in that body of literature, international law is seen as an intervening variable between the goals of states on the one hand and political outcomes on the other hand. In other words, international law is seen as a regulatory mechanism, not a constitutive one, that conditions states’ identities and interests (Goldstein et al., 2000; Burchill et al., 2005).

Davidson (2011: p. 15) also offers a state level perspective charging that the more future benefits a state can expect from membership in the alliance (alliance value), the more likely that state is to do BS. In other words, the value a state places on an alliance is determined by its own perception of relative influence in the alliance as well as external threat perceptions (s.f. Cimbala and Forster, 2010). The opposite holds as well: if a state assigns less value to allies (and thus the alliance), one expects it to shoulder little or no collective burdens.

Further, a significant body of literature is concerned with questions of alliance politics (or bargaining), especially alliance entrapment and abandonment (Hynek and Marton, 2012; Mastanduno, 1981; Snyder, 1984). Both can be subsumed under the alliance dependence literature (see Zyla, 2015 for a discussion) where states face a security-autonomy trade-off by risking to either be abandoned or entrapped by the alliance. The latter denotes a situation whereby a state either does not share the collective burden of engaging an external aggressor posing a threat to the alliance, or when the state in question decides to align itself with that aggressor and against the alliance. The more autonomy a state exerts vis-à-vis its allies, the less secure the latter are. Therefore, states constantly fear being abandoned by their allies (Snyder, 1984; Kupchan, 1988). On the other hand, the less autonomy a state has vis-à-vis its allies, the more likely it is to fear entrapment in their quarrels (Snyder, 1997). In the case of NATO, it is expected that states who fear losing America’s security guarantee are inclined to share collective NATO burdens; conversely, they might feel entrapped by being part of US-led military missions in which they have little (national) interests at stake (Bennett et al., 1994: pp. 44–45; see also Gowa, 1989: p. 314–16). In other words, from a cost-benefit calculation, the level of dependence on the US as NATO’s superpower is expected to determine the likeliness of support for US military endeavors. Snyder, for example, finds that a highly dependent ally on American power will tend to actively and unconditionally support US military interventions in exchange for security guarantees (hence sacrificing autonomy for greater security). Inversely, a more independent ally will tend to shirk and restrain US foreign policy for fear that entrapment outweigh that of abandonment. On the other hand, allies who witness the most exposure to military threats tend to meet their BS commitments as a means to entrap or entangle the US. In short, this interdependent relationship and the risk of either being abandoned or entrapped is multidirectional. It is also an example of complex interdependencies that involve complicated trade-offs when collective action problems such as BS are debated politically.

Limits of system- and state-level BS theories

The Cold War’s end problematized the power- and interest-based theories outlined above, and revealed their theoretical and methodological limitations in explaining BS behaviors for the following reasons: (1) the public good of collective defense received a new meaning at the Cold War’s end (Dorussen et al., 2009) as NATO’s primary objective of collective defense was amended by crisis management. Indeed, what we witnessed at the Cold War’s end was a significant increase in demand for peace operations (e.g., in Bosnia, Kosovo etc.) that essentially merged military and humanitarian missions, as well as a globalized threat scenario. Both developments have not only significantly expanded the geographical area of operation for the alliance; it also altered the tangible and intangible expenses of these collective peace operations. As a result, the scope against which burden sharing is measured has been expanded (s.f. Cimbala and Forster, 2010: p. 3), and can include, for example exposure to risks, casualties, as well as additional strategic, operational, and tactical costs. (2) The public choice model has limited explanatory value for understandingFootnote 15 BS behavior because, ontologically speaking, it focuses nearly exclusively on material rather than also on ideational BS variables, for example on what motivates states to share burdens. Its practical application has also been limited to the concept of nuclear deterrence, an output (Cimbala and Forster, 2010: p. 11). Indeed, as we will show in the next section, the public choice model neglects non-material variables in its research program (i.e., status, prestige, recognition, and values to explain the dependent variable (BS) and fails to explain why states consider the benefits accrued from collective actions differently (Cooperand Zycher, 1989). Considering these ideational variables, however, would allow an unpacking of the value-rational motivations and interests of social agents for BS. (3) As numerous studies have shown, the rational model’s ontological assumptions of jointness and pureness are hardly applicable to real world settings (Alfano and Marwell, 1981; Marwell and Ames, 1979, 1980; Sweeney, 1973; Dorussen et al., 2009; Snidal, 1985). Individual rationality, methodologically speaking, is insufficient to produce collective rationality of an alliance (Golden, 1983: p. 42) as national decisions made independently of allies is most likely to result in collective failure (Cimbala and Forster, 2010: p. 13). (4) NATO public goods are not equally and efficiently produced among all allies, and alliances may also produce more than one public good, which could be traded between allies (Boyer, 1993: p. 32). (5) The assumption that actor’s preferences on burden sharing, especially in changing security environments are stable over time is simply not realistic (Hasenclever et al., 1997). (6) Moreover, not all BS costs and risks are quantifiable and sometimes intangible, which complicates BS measurements (s.f. Cimbala and Forster, 2010: p. 9). Nuclear powers, for example, contribute unique capabilities that non-nuclear states do not possess. Others (e.g., Iceland or Denmark) have contributed to the alliance by allowing access to crucial territory (Dansk Udenrigspolitisk Institut, 1997). During the Cold War Germany’s subsidies to Berlin were factored in the agreed burden sharing equation at NATO. Frontier states (Germany during the Cold War, Poland and the Baltic states today) provide the battlefield for collective defense scenarios. The associated risk they involuntarily took is no small contribution to the common burden and territorial security of other members (Tuschhoff, 1999, 2002, 2003).

In sum, one must therefore conclude that the rather restrictive assumptions of rationalist theories of NATO BS can only go so far in explaining contemporary burden sharing behavior. They are overly reductionist, parsimonious, simplified, and static, and clearly lack an understanding of states’ intersubjective social structures, meanings, their value-rational motivations for (or against) sharing collective burdens that arrive before considering BS as an output. These variables need to be considered as independent variables to better explain BS behavior. While Cimbala and Forster (2010) hint at this by distinguishing between tangible and intangible BS contributions, they do not offer alternative theories or methodologies that allow us to study those variables systematically.

Individual level variables

The points of critique summarized above underline the claim that the BS research program needs an inductive (bottom-up) approach that considers ideational variables to explain allies’ BS behavior. Such approach would allow us to understand how states define NATO’s public goods and what meaning they assign to it, including what social norms and shared societal understandings, beliefs, values, discourses, and power structures inform their BS decisions and behavior. Idea/identity-based theories may be helpful in this regard filling an obvious void. While they have been applied and widely used in International Relations, they have largely been absent from studying NATO burden sharing, which is why we discuss them here. By considering someFootnote 16 of the most pertinent strands of that theoretical literature, we offer some suggestions of how they could be useful in producing new insights in studying BS beyond considering input/output levels. To be clear, due to space limitations our objective here is not to advance or test those theories empirically. Rather, we simply aim to show how these idea/identity-based theories could potentially provide a deeper analysis. As noted above, we also do not take sides in the debates on whether these idea/identity-based theories are indeed theories or whether they should better be considered meta-theoretical standpoints that ameliorate existing IR theories (s.f. Carlsnaes, 2001; Haas, 1993).

Especially Constructivist theories in International Relations stress ideas and identity as variables (Wendt, 1999) in their explanations. They are thus critical of the rationalist theories discussed in section two above, which treat ideas and identities as exogenously given. Rationalist scholarship, they charge, treats the processes that produce the self-understandings of states (e.g., their identities) as well as the ideas and objectives of what they perceive to be in their (national) interest as a black-box, as an unknown process. Constructivist theorists challenge this ontological claim by pointing out that these processes are causally affected by decision maker’s beliefs and values. Before policy officials or politicians can make decisions, the given circumstances are to be assessed based on the knowledge provided and acquired by these actors. This process is subject to interpretation because the body of knowledge that an actor holds not only shapes the perception of reality; it also allows decision makers to make links between cause and effect relationships, or means and ends calculations (Adler and Haas, 1992; Haas, 1992). As a consequence, constructivists hypothesize that changes in decision maker’s belief systems can indeed change policies and thus the perceived options available to states. In other words, the BS policy of states depends on the foreign policy actor’s (e.g., state official, bureaucrat, politician etc.) perceptions of international problems and threats (the natural and social world). Here, a post-positivist BS research program would build on positivist scholarship (e.g., Tuschhoff, 1999, 2002, 2003; Golden, 1983) to help us better understand NATO BS behavior.

Moreover, these beliefs can be considered at least partially independent from material interests (e.g., the distribution of power and wealth); indeed, they constitute state identities (Risse, 2010). The importance of this in the BS context is to realize that the constructions of reality both enact and reify relations of power (Weldes, 1998, 1999), which in the rationalist ontology is considered a key currency for understanding BS behavior. In sum, it is hypothesized that what we commonly understand as BS ‘‘reality’’ is indeed socially constructed and thus contestable. Here, future BS studies could build on, for example, Kitchen’s (2010) work who argues that transatlantic identity is constructed through political discourses shaping normative predispositions about the appropriate behavior of NATO members in out-of-area operations.

Learning

We speak of learning when BS actors alter their beliefs and this results in changes of behavior (Risse, 2004; Checkel, 2007). Understanding processes of learning is significant in the BS context, because in an alliance of 29 member states and regular, institutionalized political discussions (e.g., in the North Atlantic Council), states might indeed learn from the experience of other states of how to best contribute to an allied cause in a specific historical context. States can also, if they decide to, adjust their BS behavior based on past experiences as learning can occur when states, for example, acquire new understandings of their social world (e.g., other allies) that may prompt BS decision makers to alter their political goals (or how to get there), or to reformulate the state’s political goals vis-à-vis BS entirely (changing national interests) (Haas, 1990). The BS literature knows very little at this point about how states perceive BS in their domestic polities, if states have engaged in BS learning, or are currently in the process of learning from past experiences. Yet, an analysis of this learning process, also longitudinally over time say for NATO’s major- or middle powers, might produce interesting insights, given the internal threats that the alliance is currently facing (see introduction).

Perceptions

The BS literature clearly shows a gap in studying how allies perceive collective burdens in their domestic polities. When state officials (bureaucrats, politicians etc.) negotiate who shares what allied burden (e.g., in the North Atlantic Council), we currently have very limited insights as to how they perceive other states’ definitions of fairness, how they frame BS conflicts and contestations, and how BS has become part of their international identity (Wendt, 1992, 1994). The point is that these perceptions as well as perceived policy options are important considerations, and they can influence BS behavior. They are thus more than exogenously given as rationalists would charge. The point is that perceptions are entirely understudied in the rationalist BS literature because positivist epistemologies, as we have shown above, assume that social interactions between states and their officials are governed by objective, general laws that are independent of human subjectivity and that can objectively explain (social) behaviors (Hempel and Oppenheim, 1948). Here, a post-positivist BS research program could build on the literature of alliance value, which Davidson defines as the “anticipation of future benefit from the alliance” (2011, p. 15). Thus far, however, alliance values have been mainly used in rationalist BS studies showing state support or refusal for participating in NATO military interventions when a highly valued ally requests it (e.g., the US).

Norms

A significant body of literature discusses the importance of norms (Klotz, 1995; Sedelmeier, 2005) for explaining the foreign policy behavior of states and considers them as independent variables (Barnett and Finnemore, 2004; Carlsnaes, 2001: p. 338; Houghton, 2007: pp. 31–33; Finnemore and Sikking, 1998). Wendt defines norms as “intersubjective beliefs about the social and natural world that define actors, their situations, and the possibilities of action” (1995). Indeed, they are social facts setting standards of appropriate behavior and express the agents’ identities (Finnemore, 1996; Katzenstein, 1996; Klotz, 1995). Norms also prescribe how things ought to be in the world (Finnemore and Sikkink, 1998), help actors to situate themselves vis-a-vis others, to interpret their interests and actions, and foster group identification. As a result, norms can be studied as justifications for social actionsFootnote 17, as sources of social power (Hurrell, 2002), and create new actors and interests (Katzenstein, 1996; Ruggie, 1998). With regards to BS, it is currently largely unknown if norms have affected past BS behaviors. This in and of itself reveals a clear gap in the literature.

Socialization

Theorists charge that sociality—that is BS actors who are interacting or socializing with others—always informs individual rationality (not the reverse). Consequently, do not make BS decisions exclusively based on strict cost-benefit calculations following a logic of consequentiality (March and Olsen, 1989); they may also follow a logic of appropriateness assessing what behavior might be appropriate for them and the alliance in a given collective action situation: “Political actors associate specific actions with specific situations by rules of appropriateness. What is appropriate for a particular person in a particular situation is defined by political and social institutions and transmitted through socialization” (March and Olsen, 1989: p. 23). Put differently, intersubjectively shared meanings are important variables to explain BS behaviors (Kratochwil and Ruggie, 1986), because they have a regulative and constitutive character (Dessler, 1989). Material causes do not make states act in a certain way; they make it possible that they act. Applied to the issue of BS this means that BS interests are not exclusively material but can also be socially constructed and thus constitutive of those interests—that is they are “produced, reproduced and transformed through the discursive practices of actors” (Weldes, 1998: p. 218; Larsen, 1997; Price and Tannenwald, 1996). As a consequence, these processes of socialization should be studied to achieve full explanations and understandings of allies’ BS behaviors. A post-positivist BS research program would allow us to study these representations as well as state’s interpretations of BS fairness.

Security community

A significant and influential literature has developed over the past years on pluralistic security communities. They are defined as groups of states that retain their sovereignty while sharing a common identity with other states (Williams and Neumann, 2000), resulting in, for example, expectations of a peaceful resolution of disputes as well as security coordination and cooperation (s.f. Deutsch, 1957). Deutsch defines a pluralist community as a group of states that have become integrated to the point where they have a sense of a coherent group or small community while retaining their national sovereignty: “These states within a pluralistic security community possess a compatibility of core values derived from common institutions, and mutual responsiveness—a matter of mutual identity and loyalty, a sense of we-ness, and are integrated to the point that they entertain dependable expectations of peaceful change” (Adler and Barnett, 1998: p. 7).

Constructivists have further developed this concept by examining how actors share values, norms, customs, and symbols that provide a social identity of a particular community (Hellmann and Herborth, 2016; Anderson et al., 2008; Kopstein and Steinmo, 2008). The essence of security cooperation is that states rely on the resources and commitments of other states for its national security and thus its survival. This may allow for a changing conception among alliance partners of what actually constitutes ‘‘security’’, and for a move away from traditional threats of states towards other forms of security (e.g., social progress and well-being, and economic and environmental notions of security).

The purpose of seeking security communities is a reduction of transaction costs of parties within such a community. They also provide a forum for communication and exchange: parties are told what others expect them to do and what they could expect from their peers (Müller, 2002; Mitchell, 1998). The conclusion, however, that all states are equally seeking such security cooperation did not stand the evidence. Indeed there are differences among the members of a security community, and some, as Harald Müller notes, seek deeper integration than others: “If we compare the present inclination of democratic states to expand the realm of security cooperation in ways that imply further constraints on national sovereignty, we find countries like Canada, Sweden, the Netherlands or Germany in the forefront, the United Kingdom somewhere in the middle, and France, and even more the United States, towards the end” (Müller, 2002 p. 378).

Adler and Barnett outline three defining characteristics of security communities. First, such communities will have shared identities, values and meanings which are ascribable to events, institutions and actors. Second, they will have “many sided and direct relations” or varied, numerous and personal relations not just at governmental levels but at trans-national levels. Third, states will exhibit reciprocity in relations and a certain degree of altruism, obligation and responsibility towards one another (Adler and Barnett, 1998). Such communities can also provide a mechanism through which learning can occur (Schimmelfennig, 1999), which we have discussed above.

Moreover, latest constructivist scholarship has concentrated on the question of agency, which is an empirical point where both rationalist and interpretative research programs could meet and inform each other. Franke’s (2010) work might be a good starting point here. He conceives “NATO as NATO”, and suggests that the alliance is a collectively constructed agent that indeed acts independently of its member states. On the operational level and considering NATO as having agency allows us to, for example, study how the processes of defense planning or force generation impact national burden sharing practices. Here, future post-positivist BS studies could build on earlier constructivist scholarship studying international organizations. Barnett and Finnemore (2004), for example, examine international organizations as Weberian bureaucracies that not only have a unique institutional culture; they also act independent of its member states and utilize their authority and knowledge to regulate and thus constitute a world. In other words, international organizations create a political world they operate in. This is important, because, as Deni (2004, 2007a, 2007b) shows, some member states shoulder more than their share of the alliance burden when it comes to, for example, providing headquarters to gain political and military control over allied operations. Others, such as Tuschhoff (2014), show that burden sharing contributions by member states can vary based on principles and practices that guide defense planning and force generation processes. In contrast, Giegerich (2006, 2008) focuses on national ambition as a variable of domestic politics.

Communication

NATO’s 2% GDP benchmark of how much allies should spend on defense, which has caused significant friction among allies recently, can be seen as a goal post and a collective rule. Studying communications and discourses in collective action situations, as Habermas (1996) reminds us, would allow us to understand the processes of rule interpretation and their application (Cox, 1981), for example why some states spend less than 2% of their GDP on defense. It would also strengthen the argument that BS interests do not exclusively emerge from the material reality. Future BS studies might use, first, Franck (1990) and Hurrel’s (2007) work as starting points here who have argued that norms and rules must be perceived by states as legitimate and fair to ensure their compliance with them. At this point, however, we have no insights as to how allies interpret the 2% rule that allies agreed to in 2014, and thus cannot fully explain why they do not comply with that rule. Second, studies focusing on state reputation might also be beneficial in this regard (Schlag, 2016), as well as those that show that the language of international rules must be clear and precise in order to increase their compliance and overall effectiveness (Kratochwil, 1993).

In sum, idea/identity-based theories hypothesize that discursive and representational practices make material interests valuable in the first place (Adler, 2002: p. 95). With regards to BS, this means that states’ BS choices emerge from multiple reasonings at the individual level, which entail the production of meaning through intersubjective interaction (rather than merely through individual action; c.f. Rhodes, 1994; Finnemore, 1996), and that give meaning to the particular BS situations.

Some methodological considerations for a post-positivist burden sharing research program

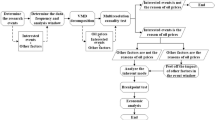

The post-positivist theories discussed in section three suggest an inductive reasoning based on qualitative research methods that see the world from within BS (Creswell, 1994; Denzin and Lincoln, 2000, Denzin, 2008; Silverman and Marvasti, 2008), and that promise to be more holistic (Jackson, 2003: p. 135). It thus suggests a very different research design than the commonly used deductive one. Below, we sketch out some particular methods that allow an operationalization of some of the ontological and epistemological propositions discussed above in a post-positivist research program (e.g., Neumann, 1999). Similarly to section 3, we offer some guideposts of how to move the BS research program into a post-positivist direction, without making claims to comprehensiveness.

Case studies

The first method that comes to mind are case studies. A qualitative BS research program could clearly use some more comparative, heuristic case studies, especially from less well-studied cases, for example, states in from central, eastern, and southern Europe (e.g., Estonia, Albania, Poland etc.) or so-called middle powers for the purpose of detecting larger phenomena, meanings, and causal mechanisms (Bennett and George, 2005: p. 75; della Porta and Keating, 2008: p. 226). Cases are defined as “the detailed examination of an aspect of a historical episode to develop or test historical explanations that may be generalizable to other events” (Bennett and George, 2005: p. 5). In that sense (and contrary to especially statistical BS studies), they do not omit all contextual factors; indeed, inductive case studies are particularly well-known in fostering new hypothesis and addressing causal complexity where statistical methods and formal models are weak (Ibid.: p. 19).

Moreover, as alluded to above, one might consider these types of cases longitudinally. Conceivable, for example, would be examining NATO’s first so-called out of area operations in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s (Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Macedonia, Kosovo), followed by missions in Darfur, Afghanistan (2003–14), Pakistan (2005–06), Somalia (2008–), and Libya (2011).

However, in order to strengthen the generalizability of the findings it is also important to go beyond the alliance context as sources of potential future case studies. The different UN operations in various parts of the world come to mind. The advantage focusing on UN operations clearly is to study BS outside the so-called ‘‘Atlantic community.’’

Expert interviews

Semi-structured or even unstructured interviews with subject matter experts (e.g., with high ranking government officials, ministers, deputy ministers, director generals, NATO international staff) would produce rich, detailed qualitative data. In particular, these interviews would allow post-positivist researchers to (1) explore the value policy makers and/or the respective ministry assign to NATO’s public goods as well as their motivation for (or against) sharing collective NATO burdens; (2) bring out how the interviewees themselves make sense of BS issues, contexts, and related events; (3) provide meaning for government or individual actions related to NATO BS and to corroborate what has been established from other sources (triangulation); (4) are a flexible way of gaining access to the individual’s cognition, meanings of concepts, language, and belief systems. Having said that, we also need to be cautious of applying this method as it is very difficult in those interviews to detect whether the interview partner speaks for her-/himself and thus reveals her/his own positions on a particular issue, or whether s/he simply echoes politically engineered justifications for or against BS. One way to reduce the latter likelihood is to triangulate the interviews with other (primary) sources.

Discourse analysis

As Milliken (1999) reminds us, a discourse analysis is a system of signification that deconstructs social realities, representations of the world, social subjects and social relations, suggesting that there is a dialect between BS meaning, reality, and social practices. Discourses can thus be seen as an inescapable medium through which we make sense and reproduce BS reality. It is a form of social practice that both constitutes the social (BS) world and is constituted by other social practices. It also produces the subjects and objects it makes intelligible, and exclude others as irrelevant.

To be sure, discourse analysis is not new to studying NATO. Kitchen (2010), for example, has shown using a discourse analysis how institutional change is possible through changing discourses at the level of political elites as well as how these elites have nourished certain transatlantic norms over time and how they were engaged in processes of social learning. In our context here, however, such a discourse analytical perspective is absent. Thus, there is analytical room for a qualitative discourse analysis on BS that could, for example, help defining (a) the situation BS decision makers are situated in and within a larger political and public sphere authorized to speak and to act on BS; (b) the audiences for these authorized actors; (c) the common sense binding speakers and audiences. A qualitative discourse analysis is also able to reveal the representations that they draw upon and how they are formed by the representations articulated by a larger number of individuals, institutions, and media outlets (Hansen and Waever, 2002; Larsen, 1997). More concretely, top politicians in the respective NATO member states rarely have detailed knowledge of BS and, therefore, rely upon their advisors, media coverage, and, in some cases, background literature to establish a representational framing of BS. In ‘‘speaking back’’ their representation of a foreign policy issue, politicians are in turn influencing what counts as proper representation within BS debates. One may assume that it is extremely unlikely and politically unsavvy for them to articulate a BS policy without showing concern for the representations found within the wider public sphere as they attempt to present their BS policies as legitimate to the electorate (Fairclough, 1992: p. 237). In other words, understanding official BS discourse opens up an analytical perspective examining (a) how BS representations articulated by oppositional political forces, the media, academe, and popular culture reinforce or contest each other (c.f. Hansen and Wæver, 2002; Holm, 1993, Der, 1992; Neumann, 1996); (b) to what kind of network of larger foreign policy discourses the discursive practice of BS belongs to (i.e., how the discourses are distributed and regulated across textsFootnote 18); and (c) to map the social and cultural relations and structures that constitute the wider institutional and economic contexts of the discursive practice (“the social matrix of discourse” (Fairclough, 1992: p. 237).

Conclusion

Studying NATO burden sharing has attracted a lot of scholarship and political debates since NATO was created in 1949. While the rationalist scholarship in the fields of International Relations and International Political Economy, with all its epistemological and methodological values and focus on input/output indices, has clearly dominated the scholarly BS analysis, we suggested here that the literature would benefit from more post-positivist studies in the BS research program. This promises to produce additional, deeper analytical insights, as well as fruitful, new explanations of BS behaviors.

Against this backdrop, we offered some ideal/identity-based theoretical deliberations on NATO BS, as well as some operationalization of such new BS research program. The aim of this article was to start a conversation on how to move the BS research program forward theoretically and methodologically, and thereby to increase the explanatory value of BS studies moving forward. We suggested that the literature should consider more the intersubjective social structures and representations of BS agents and their value-rational motivations for sharing NATO burdens. As the Constructivist scholarship in the field of International Relations reminds us, it is not merely a rationalist, strict cost-benefit analysis that determine states’ motivations; it can also be informed and driven by societal norms, values, as well as beliefs and power structures (Foucault and Mérand, 2012). We, therefore, suggested that the NATO BS research programs should include these intersubjective social aspects in its analyses, also in (comparative) case studies. The benefit of such an inductive approach is that it moves beyond considering BS as a static outcome; indeed, it gives BS agency and the tools to analyze those processes. Moreover, it would help to produce different causal explanations and understandings of state motivations for (or against) sharing NATO burdens, for example, understandings of how states interpret NATO burdens in their domestic polities, how these burdens are constructed, and what meanings states assign to it and in what particular institutional context (Geertz, 1973: p. 5), as well as how national burden sharing values might be negotiated and traded in the political marketplace (e.g., North Atlantic Council). Having said that and to be sure, if we agree in general to include these post-positivist perspectives in the BS research program, we have just started the conversation because above all BS is a political issue rather than a military one.

Notes

Here territorial access, overflight rights, base access, fatality rates, political risks from participating in non-Article five missions have been considered as variables.

When spending more on the military, less money is available for other government programs and projects (e.g., social, development etc.); economic assistance to Central and Eastern Europe has also been considered a ‘‘soft’’ economic variable (Zyla, 2015), as well as state-and nation building of war-torn societies in the aftermath of conflict.

The geographical dispersion of peace operations beyond NATO territory has imposed additional burdens in terms of tactics, equipment, force capability and sustainability, and intelligence capabilities.

They are, in alphabetical order, Estonia, Greece, Poland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

A similar statement was made in (Trump, 2016).

The point here is to simply illustrate some rather prominent contestations on NATO BS rather than offering a comprehensive overview thereof, longitudinal or otherwise. For earlier debates see (New York Times, 1988).

Space allocations would not allow for reviewing such an extensive body of literature; it has also been accomplished elsewhere (Zyla, 2015, chapter 2); parts of this are also drawn from Zyla, 2018.

It is thus hardly surprising that until this day middle or small powers do not feature prominently as units of BS analysis, which explains past case selections (e.g., USA, Germany etc.).

Preferences are assumed to be constant. They may not be directly observable but can be investigated empirically.

This is meant in the Weberian sense of the term.

The constructivist literature in the field of international relations is immense. As a result, we cannot account for every aspect of that literature.

Finnemore and Sikking (1998: pp. 895–905) has further analyzed the processes of ‘‘norm emergence’’, ‘‘norm cascade’’, and ‘‘norm internalization’’ as described.

This will also allow to identify NATO members who change their political conversations by trying to divert the discussion to ‘‘softer’’ indices (e.g., foreign aid contributions) as their BS commitment and thus deflecting criticism.

References

Adler E, Haas EB (1992) ‘Epistemic communities, World order, and the creation of a reflective research program’. Int Organ 46(1):367–90

Adler E, Barnett M (1998) Security communities. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Adler E (2002) Constructivism and international relations. In: Carlsnaes Walter, Risse Thomas, Simmons Beth (eds). Handbook of International Relations. Sage Publications, London, pp. 95–119

Alfano G, Marwell G (1981) Experiments on the provision of public goods iii: non-divisibility and free riding in ‘real’ groups. Social Psychol Q 43:300–3009

Anderson J, Ikenberry GJ, Risse T eds. (2008) The end of the west? crisis and chance in the atlantic order. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY/ London, UK

Auerswald DP, Saideman SM (2014) NATO in Afghanistan: fighting together, fighting alone. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Axelrod RM (1984) The evolution of cooperation. Basic Books, New York, NY

Ayer AJ (2001) Language, truth and logic. Penguin, London

Baldwin DA (1993) Neorealism and neoliberalism: The contemporary debate. Columbia University Press, New York, NY

Barnett MM, Levy JS (1991) Domestic sources of alliances and alignments: The case of Egypt, 1962-73. Int Organ 45(3):369–395

Barnett M, Finnemore M (2004) Rules for the world: International organizations in global politics. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Bennett A, Lepgold J, Unger D (1994) Burden-sharing in the Persian Gulf War. Int Organ 48(1):39–75

Betts A (2003) “Public goods theory and the provision of refugee protection: The role of the joint-product model in burden-sharing theory”. J Refug Stud 16(3):273–296

Betts A (2009) Protection by persuasion: International cooperation in the refugee regime. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Boyer MA (1993) International cooperation and public goods: Opportunities for the western alliance. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, London

Brown ME, Lynn-Jones SM, Miller SE (1995) The perils of anarchy: contemporary realism and international security. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass

Buchanan JM (2008) Politics and scientific inquiry: Retrospective on a half-century. In: Wittman DA, Weingast BR (eds.) The oxford handbook of political economy. Oxford University Press, Oxford p 980–995

de Mesquita B, Bruce J, Lalman D (1992) Domestic opposition and foreign war. Am Political Sci Rev 84(3):747–66

Burchill SAL, Devetak R, Donnelly J, Paterson M, Reus-Smit C, True J (2009) Theories of International Relations, 3rd edn. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2005

Buzan B, Jones CA, Little R (1993) The logic of anarchy: neorealism to structural realism. Columbia University Press, New York, NY

Campbell D (1992) Writing security: United States foreign policy and the politics of identity. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis

Caplow T (1968) Two against one: Coalitions in triads. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Carlsnaes W (2001) Foreign policy. In: Carlsnaes W, Risse T, Simmons B (eds) Handbook of international relations. Sage Publications, London, pp. 331–349

Checkel JT (ed.) (2007) International institutions and socialization in Europe. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Cimbala SJ, Forster PK (2010) Multinational military intervention; NATO policy, strategy, and burden sharing. Burlington, Ashgate

Claude IL (1962) Power and international relations. Random House, New York, NY

Cooper CA, Zycher B (1989) Perceptions of NATO burden-sharing. RAND, Santa Monica, CA

Cornes R, Sandler T (1984) The theory of public goods: Non’-nash behaviour. J Public Econ 23(1984):367–379

Cox RW (1981) Social forces, states and world orders: Beyond international relations theory. Millenn-J Int Stud 10(2):126–55

Creswell JW (1994) Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Sage, London

Dansk Udenrigspolitisk Institut (1997) Gronland under den Kolde Krig. Dansk Udenrigspolitisk Institut, Kobenhaven

David SR (1991) Explaining third world alignment. World Polit 43(2):233–256

David SR (1992) Why the third world still matters. Int Secur 17(3):127–159. /1993

Davidson J (2011) America’s allies and war: Kosovo, Afghanistan and Iraq. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY

della Porta D, Keating M (2008) Approaches and methodologies in the social sciences. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Deni JR (2004) The NATO rapid deployment corps: Alliance doctrine and force structure. Contemp Secur Policy 25(3):498–523

Deni JR (2007a) Alliance management and maintenance. Ashgate, Hampshire, UK/ Burlington, VT

Deni JR (2007b) Alliance management: NATO’s fight against terrorism. Stud Dipl 60(3):137–156

Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (2000) Handbook of qualitative research, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, Calif.

Denzin NK (2008) Strategies of qualitative inquiry, 3rd edn. Sage Publications, Los Angeles

Der D (1992) Antidiplomacy: Spies, terror, speed, and war. Basil Blackwell, Oxford

Dessler D (1989) What’s at Stake in the agent-structure debate. Int Organ 43:441–73

Deutsch K (1957) Political community and the North Atlantic area. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J

Dorussen H, Kirchner EJ, Sperling J (2009) Sharing the burden of collective security in the European union. Int Organ 63(4):789–810

Duffield JS (1996) The NorthAtlantic treaty organization: Alliance theory. In: Woods N (ed.) Explaining international relations since 1945. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 337–354

Fairclough N (1992) Discourse and social change. Polity Press, Cambridge

Finnemore M, Sikkink K (1998) International norm dynamics and political change. Int Organ 52(4):887–917

Finnemore M (1996) National interests in international society. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y

Franck TM (1990) The power of legitimacy among nations. Oxford University Press, New York, NY

Franke U (2010) Die NATO nach 1989. Das Rätsel ihres Fortbestandes. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden

Frieden JA (1999) Actors and preferences in international relations. In: Lake DA, Powell R (eds.) Strategic choice and international relations. Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp. 39–76

Foucault M, Mérand F (2012) The challenge of burden-sharing. Int J 67(2):423–429

Frohlich N, Oppenheimer J, Young O (1971) Political leadership and collective goods. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J

Gates RM (2011) The security and defense agenda (Future of NATO).” A speech delivered by Secretary of Defense, Brussels, Belgium, Friday, June 10, 2011. Retrieved 20 August, 2011, from http://www.defense.gov/speeches/speech.aspx?speechid=1581

Geertz C (1973) The interpretaion of cultures: Selected essays. Basic Books, New York, NY

Gerring John (2012) Social science methodology: a unified framework. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; New York, NY

Giegerich B (2006) European security and strategic culture. National responses to the EU’s security and defence policy. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden

Giegerich B (2008) European military crisis management. Connecting ambition and reality. Routledge, New York, NY

Gilpin RG (1981) War and change in international politics. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Golden J (1983) The dynamics of change in NATO: A burden-sharing perspective. Praeger, New York, NY

Goldstein J, Kahler M, Keohane RO, Slaughter A (2000) Legalization in world politics. International organization 54(3)

Gowa J (1989) Rational hegemons, excludable goods, and small groups: An epitaph for hegemonic stability theory? World Polit 41:307–24

Grieco JM (1988) Anarchy and the limits of cooepration: A realist critique of the newest liberal institutionalism. Int Organ 42:485–507

Haas EB (1990) Saving the Mediterranean: The politics of international environmental cooperation. Columbia University Press, New York, NY

Haas EB (1992) Knowledge, power, and international policy coordination. Int Org 46(1):1–35

Haas EB (1993) Epistemic communities and the dynamics of international environmental co-operation. In: Rittberger V, Mayer P (ed.) Regime theory and international relations. Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp. 168–201

Habermas J (1996) Between facts and norms: Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy. The MIT Press, Cambridge, M.A

Hansen Lene, Waever Ole (2002) European integration and national identity: The challenge of the nordic states. In: Waever Ole (ed.) Identity, communities and foreign policy: discourse analysis as foreign policy theory. Routledge, London, pp. 20–49

Hartley K, Sandler T (1999) NATO burden-sharing: past and future. J Peace Res 36(6):665–680

Hasenclever A, Mayer P, Rittberger V (1997) Theories of international regimes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; New York, NY

Hellmann G, Herborth B (2016) Uses of ‘the West’: Security and the politics of order. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hempel CG, Oppenheim P (1948) Studies in the logic of explanation. Philos Sci 15:135–75

Holm U (1993) Det franske Europa. Aarhus University Press, Aarhus

Hopf Ted (2002) Social construction of international politics: Identities and foreign policies: Moscow, 1955 and 1999. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Houghton D (2007) Reinvigorating the study of foreign policy decision making: towards a constructivist approach. Foreign Policy Anal 3(1):24–45

Hurrell A (2002) Norms and ethics in international relations. In: Carlsnaes W, Simmons BA, Risse-Kappen T (eds.) Handbook of international relations. SAGE, London, pp. 137–54

Hurrell A (2007) On global order: power, values, and the constitution of international society. Oxford University Press, Oxford; New York, NY

Hyde-Price AGV (2007) European security in the twenty-first century: the challenge of multipolarity. Routledge, London; New York, NY

Nik H, Péter M (2011) State building in Afghanistan: multinational contributions to reconstruction. Routledge, Milton Park

Ikenberry GJ (2002) America Unrivaled: the future of the balance of power. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Katzenstein PeterJ (1996) The culture of national security: Norms and identity in world politics. Columbia University Press, New York, NY

Keck M, Sikking K (1998) Activists beyond borders: Advocacy networks in international politics. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY

Keohane RO (1988) International institutions: Two approaches. Int Stud Q 32(4):379–396

Keohane RO (1984) After hegemony: Cooperation and discord in the world political economy. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J

Keohane RO (1989) International institutions and state power: Essays in International relations theory. Westview Press, Boulder

Kimball AL (2010) Political survival, policy distribution, and alliance formation. J Peace Res 47(4):407–419

Kitchen VM (2010) The globalization of NATO: intervention, security and identity. Routledge, London; New York

Klotz A (1995) Protesting prejudice: Apartheid and the politics of norms in international relations. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Kopstein J, Steinmo S eds. (2008) Growing apart? America and Europe in the twenty-first century. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK; New York, NY

Kratochwil FV, Ruggie JG (1986) International organization: A state of the art on an art of the state. Int Organ 40:753–75

Kratochwil FV (1993) Norms versus numbers. Multilateralism and the rationalist and reflexivist approaches to institutions-a unilateral plea for communicative rationality. In: Ruggie JG (ed.) Multilateralism matters: The theory and praxis of an institutional form. Columbia University Press, New York, NY, pp. 443–74

Krauthammer C (1990) The unipolar moment. Foreign Aff 70:23–33. 1991

Kreps S (2010) Elite consensus as a determinant of alliance cohesion: Why public opinion hardly matters for NATO-led operations in Afghanistan. Foreign Policy Anal 6(3):191–215

Kupchan CA (1988) NATO and the Persian gulf: Examining intra-alliance behavior. Int Organ 42:317–346

Larsen H (1997) Foreign policy and discourse analysis: France, Britain and Europe. Routledge, London

Larson DW (1991) Bandwagoning images in American Foreign Policy. In: Jervis R, Snyder JL (eds.) Dominoes and bandwagons: strategic beliefs and great power competition in the Eurasian rimland. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, pp. 85–111

Levy JS, Barnett MM (1991) Domestic sources of alliances and alignments: The case of Egypt, 1962-1973. Int Organ 45(3):369–395

Lundestad G (1998) No end to alliance: the United States and Western Europe-past, present, and future. St. Martin’s Press, New York, NY

Lundestad G (2003) The United States and Western Europe since 1945: From “empire” by invitation to transatlantic drift. Oxford University Press, Oxford; New York, NY

March JG, Olsen JP (1989) Rediscovering institutions: The organizational basis of politics. Free Press, New York, NY

March JG, Olsen JP (2004) The logic of appropriateness. vol. 9, ARENA: Centre for European Studies, Oslo

Marwell G, Ames RE (1979) Experiments on the provision of public goods I: Resources, interest, group size, and the free rider problem. Am J Sociol 84(6):1335–1360

Marwell G, Ames RE (1980) Experiments on the provision of public goods II: Provision points, stakes, experience, and the free rider problem. Am J Sociol 85(4):926–937

Mastanduno M (1981) The nuclear revolution: International politics before and after Hiroshima. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY

Mastanduno M (1997) Preserving the unipolar moment: Realist theories and U.S. grand strategy after the cold war. Int Secur 21(4):49–88

Morgenthau HJ (1948) Politics among nations; the struggle for power and peace, 1st edn. A. A. Knopf, New York, NY

Müller H (2002) International Security Cooperation, In: Walter C, Thomas Risse/Beth A, Simmons (Hg.), Handbook of International Relations, Thousand Oaks (CA: Sage), S. 369–391

Neumann IverB (2002) Returning practice to the linguistic turn: The case of diplomacy. Millenn: J Int Stud 31(3):627–51

New York Times. (2016, 26 March). Transcript: donald trump expounds on his foreign policy views. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/27/us/politics/donald-trump-transcript.html?mtrref=www.factcheck.org

New York Times. (1988, 16 June). Sharing (Which?) NATO Burdens. The New York Times, A26

Olson M (1965) The logic of collective action. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Olson M, Zeckhauser R (1966) An economic theory of alliances. Rev Econ Stat 48(3):266–279

Oneal JR (1990a) Testing the theory of collective action: NATO defense burdens, 1950-1984. J Confl Resolut 34(3):426–448

Oneal JR (1990b) The theory of collective action and burden sharing in NATO. Int Organ 44(3):379–402

Oneal JR, Elrod MA (1989) NATO burden sharing and the forces of change. Int Stud Q 33:435–56

Ostrom E (1998) A behavioral approach to the rational choice theory of collective action. Am Political Sci Rev 92(1):1–22

Oye KA (1986) Cooperation under anarchy. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J

Palmer G (1990) Alliance politics and issue areas: Determinants of defence spending. Am J Political Sci 34(1):1990–1211

Petersson M, Matlary JH (eds.) (2013) NATO’s European allies: Military capability and political will. Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire

Powell R (1991) Absolute and relative gains in international relations theory. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev 85(4):1303–1320

Pouliot V (2010) International security in practice: The politics of NATO-Russia diplomacy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Price R, Tannenwald N (1996) Norms and deterrence: The nuclear and chemical weapons taboo. In: Katzenstein P (eds.) The culture of national security: Norms and identity in world politics. Columbia University Press, Columbia, pp 114–152

Rhodes E (1994) Do bureaucratic politics matter? Some disconfirming findings from the case of the US Navy. World Polit 47(1):1–41

Ringsmose J (2010) NATO burden-sharing redux: Continuity and change after the cold war. Contemp Secur Policy 31(2):319–338

Risse T (2004) Social constructivism and european integration. In: Wiener Antje, Diez Thomas (eds) European integration theory. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 159–176

Risse T (2010) A community of Europeans? transnational identities and public spheres. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Ruggie JG (1998) What makes the world hang together? Neo-utilitarianism and the social constructivist challenge. Int Organ 52(4):855–84

Samuelson PA (1954) The pure theory of public expenditure. Rev Econ Stat 36:387–389

Sandler T, Hartley K (1995) The economics of defense. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; New York, NY

Sandler T, Hartley K (1999) The political economy of NATO: past, present, and into the 21st century. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.; New York, NY

Sandler T, Shimitzu H (2014) NATO burden sharing 1999–2010: An altered alliance. Foreign Policy Anal 10:43–60

Schatzki T, Knorr Cetina K, von Savigny E (eds) (2001) The practice turn in contemporary theory. Routledge, New York, NY

Schlag G (2016) Außenpolitik als Kultur: Diskurse und Praktiken der Europäischen Sicherheits- und Verteidigungspolitik. Springer Verlag, Wiesbaden

Schimmelfennig F (1999) NATO enlargement: A constructivist explanation. In: Chafetz G, Spirtas M, Frankel B (eds.) The origins of national interests. Frank Cass Publishers, London, pp 198–234

Sedelmeier U (2005) Constructing the path to eastern enlargement: The uneven policy impact of EU identity. Manchester University Press, Manchester

Shepsle KA (2008) Rational choise institutionalism. In: Binder SarahA, Rhodes RAW, Rockman BA (ed). The oxford handbook of political institutions. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 23–38

Silverman David, Marvasti Amir B (2008) Doing qualitative research: A comprehensive guide. SAGE Publications, Los Angeles

Sloan Stanley R (2016) Defense of the West: NATO, the European Union and the transatlantic bargain. Manchester University Press, Manchester