Abstract

Deep mining operates under complex high in-situ stress conditions where the inherent anisotropy of rock strata, caused by bedding planes and random joints. However, most existing studies on this plastic zone assume isotropic strata, which substantially deviates from real engineering conditions. Based on an improved anisotropic Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion, an analytical solution for the plastic zone under anisotropic conditions is derived. Comparative analyses—through both theoretical and numerical simulations—between anisotropic and isotropic cases confirm the considerable impact of bedding planes and joints on the plastic zone. The evolution and characteristics of the maximum principal stress and plastic zone are systematically investigated under varying in-situ stress conditions for three joint configurations: single-set joints, multi-set orthogonal joints, and multi-set non-orthogonal joints. The results reveal that for roadways with a single-set joint, the plastic zone approximates a banded distribution aligned with the joint dip direction. In multi-joint roadways, the plastic zone transitions from a hexagonal to an “X” shape as the joint dip angle increases. Furthermore, with an increasing lateral pressure coefficient, the plastic zone in orthogonally jointed strata evolves from “butterfly” to “horizontal line,” “cross,” “vertical line,” and finally an “X” shape. A case study validating the model against field observations of roadway deformation and failure in anisotropic strata demonstrates that the extension direction of the plastic zone aligns with the joint orientation, exhibiting distinct asymmetric large deformation. The close agreement between numerical simulations and field measurements substantiates the reliability of the proposed model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mining depth in China continues to increase at a rate of 10–15 m per year1,2. In some mining areas, coal seam dip angles vary significantly, with inclined or steeply inclined coal seams present. The varying bedding dip angles of overlying strata result in significant anisotropy in their mechanical properties. Furthermore, most mining areas contain well-developed geological structures, such as faults. These factors create a complex high-stress environment in deep mining, significantly affecting the distribution of the plastic zone in surrounding rock after roadway excavation3,4,5. Consequently, the surrounding rock of the roadway often shows pronounced, asymmetric, large-scale deformation6,7. Therefore, studying the evolution and failure of the plastic zone in roadway surrounding rock under in-situ stress conditions, especially in anisotropic strata, is crucial for guiding and optimizing roadway support design.

The plastic zone is a key indicator for analyzing failure and controlling deformation in roadway surrounding rock, providing a basis for assessing the extent, mode, and scope of rock mass failure8,9. Consequently, accurately characterizing the evolution of the plastic zone and its associated failure characteristics has become a major focus of research. The initial development of plastic zone theory assumed that the roadway surrounding rock was subjected to a uniform stress field and consisted of homogeneous, isotropic material. Using an implicit boundary method, Zhao10 found that the roadway plastic zone could transition between circular, elliptical, and butterfly shapes under varying pressure conditions, leading to the first proposal of the butterfly-shaped plastic zone theory. Building on this foundation, Wang and Li11,12,13 used FLAC finite difference simulations and the Mohr–Coulomb criterion to develop a simplified wing-crack model. By analyzing the distribution of fractures and stresses within the plastic zone, they developed a mechanical dilation model for surrounding rock containing weak planes. Their results showed that rock failure begins at the point of maximum tangential stress around the roadway, leading to discontinuous fracturing. They found that the failure morphology is closely related to the distribution of initial cracks, revealing the micromechanisms of unloading-induced fracturing in deep surrounding rock and offering a macroscale explanation for large deformation failures in roadways. As the butterfly-shaped plastic zone theory developed, many researchers observed significant variations in the morphology, distribution, and evolution of these zones under different geological conditions14,15,16. It is crucial to note, however, that all the aforementioned studies were conducted under the fundamental assumptions of isotropic in-situ stress and homogeneous rock formations. However, under actual engineering conditions, the surrounding rock of roadways is subjected to complex stress fields, where in-situ stresses are often non-uniform and non-orthogonal17,18,19. Zuo and Wang20,21,22 derived the tangential stress equation for a circular roadway under unequal biaxial pressure using complex variable theory. Through theoretical analysis, they examined the distribution of the plastic zone around circular roadways under different lateral pressure coefficients, proposed a theoretical formula for its calculation, and explained how the size of the plastic zone affects roadway failure modes. In addition to the lateral pressure coefficient, the rotation of the in-situ stress also plays a significant role in determining both the distribution pattern and the evolution of the plastic zone surrounding the roadway. Ma, Liu, and Li23,24,25,26,27developed a stress model for roadways under non-orthogonal conditions between in-situ and mining-induced stresses, based on the plastic zone boundary equation for circular openings under non-uniform pressure and the butterfly failure theory. They derived the boundary equation of the plastic zone under in-situ stress rotation and examined the relationship between principal stress rotation and asymmetric roadway failure. Their studies revealed that the plastic zone distribution evolves cyclically with stress rotation, following the sequence: petal-shaped → elliptical → circular → elliptical → butterfly-shaped. They analyzed the evolution of the butterfly lobe angle and summarized the mechanisms through which various factors influence its variation. The morphology of the butterfly plastic zone was found to result from the synergistic coupling of multiple factors; however, the interaction between the lateral pressure coefficient and in-situ stress conditions plays the dominant role in its evolution. Although previous studies focused mainly on plastic zone distribution in circular roadways, questions remain about its applicability to roadways with different cross-sections, variable rock conditions, and complex joint distributions. Guo28,29,30,31conducted a study on the stability of non-circular excavations within multi-jointed rock masses. Based on the implicit boundary equation of the plastic zone, they proposed a ubiquitous multi-joint model and derived a formula for calculating the plastic zone shape coefficient. They further examined the applicability of the butterfly plastic zone distribution theory and confirmed its validity for non-circular roadway sections and stratified surrounding rock. Furthermore, based on elastoplastic mechanics, they derived an analytical solution for the characteristic radius of the plastic zone.

Although extensive research has focused on plastic zone theory in isotropic surrounding rocks, the distribution patterns of plastic zones and the associated failure modes in non-orthogonal jointed rock masses under in-situ stress conditions are still not well understood. To better approximate real-world geological conditions and provide theoretical guidance for engineering practice, this study conducts an in-depth analysis of the failure characteristics of roadway surrounding rock intersected by non-orthogonal joints under different stress fields. The primary objective is to clarify the mechanisms by which complex in-situ stress conditions affect the formation and evolution of plastic zones in jointed rock masses. Furthermore, the study systematically examines the evolution patterns of plastic zone distribution under varying confining pressures and principal stress rotation angles.

Modeling the plastic zone for predicting failure in roadways within anisotropic rock masses under multiaxial stress States

Analysis of the stress state in surrounding rock of roadways in anisotropic strata

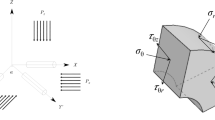

The stress analysis of a roadway in a jointed rock mass can be simplified using a plane strain model, where the rock mass is idealized as a transversely isotropic material. The horizontal and vertical elastic moduli are denoted as Ex and Ey, respectively, under horizontal and vertical in-situ stresses of σH and σh. The Analytical Stress model is shown in Fig. 1.

Using the small deformation assumption and the principle of linear superposition, the total stress field is decomposed into the models shown in Fig. 2. The stress components in polar coordinates are determined by simultaneously solving the constitutive and equilibrium equations. The solution is expressed as a function of material properties, geometric parameters, and the spatial coordinate θ, as shown in Eq. (1).

σr, σθ and τrθ denote the radial stress, hoop stress, and shear stress, respectively, at any point in the surrounding rock within the polar coordinate system.

(1) Stress components in surrounding rock under the action of q1.

In the stress analysis of roadway surrounding rock, the boundary conditions are defined as follows: at the excavation boundary (r = a), the stresses satisfy σr = 0, τrθ = 0; at infinity (r = ∞), the stresses satisfy σr = -q, τrθ = 0. For orthotropic rock masses, the stress field depends on both the radial distance r and the polar angle θ. Based on the stress variation method, a stress function for the roadway under q1 far-field in-situ pressure can be constructed as Eq. (2).

Retaining the B1 and B2 from Eq. (2) and substituting them into Eq. (1) yields the stress components of q1 in polar coordinates. The expressions are provided below:

By converting the stress components from Eqs. (3), (4) and (5) into the Cartesian coordinate system and substituting them into the stress-strain relations for anisotropic materials, the undetermined coefficients B1 and B2 are solved as follows:

The notations are defined as follows:

where Ex, Ey and Ez are the elastic moduli along the x-, y-, and z-axes, respectively; and Gxy is the shear modulus in the x-y plane. µij(i, j = x, y, z,) denotes the Poisson’s ratio.

(2) Stress components in surrounding rock under the action of q2.

In the stress analysis of roadway surrounding rock, the boundary conditions are defined as follows: at the excavation boundary (r = a), the stresses satisfy σr = 0, τrθ = 0; at infinity (r = ∞), the stresses satisfy σr = -q2cos2θ, τrθ = q2sin2θ. For orthotropic rock masses, the stress field depends on both the radial distance r and the polar angle θ. Based on the stress variation method, a stress function for the roadway under q2 far-field in-situ pressure can be constructed as Eq. (12).

By considering the first two terms, C1 and C2, in Eq. (7), their expressions are similarly determined as follows:

The stress components in polar coordinates for the load case q₂ are therefore given by:

According to the principle of stress superposition, the radial stress, hoop stress, and shear stress in the surrounding rock of the roadway are given by Eq. (18).

The transformation equations relating stresses in polar coordinates to principal stresses in physical coordinates are given by Eq. (19).

Substituting Eq. (18) into the transformation formulae of Eq. (19) yields the maximum and minimum principal stresses in the surrounding rock of the bedded roadway as follows:

Analytical solution for the plastic zone in roadway surrounding rock within anisotropic strata

The extent of the plastic zone was determined using an anisotropic Mohr-Coulomb criterion, characterized by its direction-dependent strength. The yield function is given by Eq. (21).

The cohesion (C) and internal friction angle (Φ) are not constants but instead vary with the angle (β) between the potential failure plane and the isotropic bedding plane. Through curve fitting of laboratory test data, both Φ(β) and C(β) are expressed as cosine functions of β, as shown in the Eq. (22).

In this equation, A, B, C, and D are constants that govern the orientation angles of the principal stresses. The azimuth of the principal stress plane can then be derived from the relationship between the principal stresses, as expressed in the Eq. (23).

Using the stress transformation equations between polar and Cartesian coordinates, we obtain the Eq. (24).

These values are substituted into Eq. (17) to assess the extent of the plastic zone. Plasticity is considered to have occurred when F > 0.

Evolutionary behavior of the plastic zone in surrounding rock under varying in-situ stress States

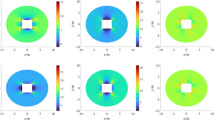

Using the above formula, the distribution curves of the plastic zone around an anisotropic roadway under varying lateral pressure coefficients (λ) are plotted, as shown in Fig. 3.

As shown in Fig. 3, the evolution of the plastic zone clearly depends on the in-situ stress regime. When the vertical principal stress is dominant, the plastic zone develops primarily along the shoulder and floor corners of the roadway, forming a transverse X-shaped pattern. Simultaneously, tensile failure occurs in the roof and floor. As the stress state approaches hydrostatic conditions, the X-shaped zone radius decreases, and its morphology becomes more rectangular as the plastic zone contracts toward the excavation boundary. Under isotropic stress conditions, a uniform circular plastic zone forms around the roadway. As the lateral pressure coefficient increases, the plastic zone develops faster in the roof and floor than in the sidewalls, forming a vertically oriented elliptical distribution. Notably, the propagation of the plastic zone into the surrounding rock does not continue indefinitely in the roof, floor, or sidewalls. Once a certain depth is reached, expansion in these directions nearly stops. Subsequently, the dominant growth shifts back to the shoulder and floor corners, resuming the X-shaped evolution pattern. Under increasingly dominant horizontal stress, plastic zone development at the shoulder and floor corners accelerates markedly. This causes a continuous increase in the plastic zone radius, ultimately forming an extensive butterfly-shaped failure zone around the roadway.

In summary, the evolutionary morphology of the plastic zone, which shows transitional forms such as rectangular, elliptical, and X-shaped patterns, is primarily influenced by the lateral pressure coefficient. The magnitude of the horizontal in-situ stress not only determines the distribution pattern of the plastic zone but also influences its evolutionary trajectory and main direction of extension. Specifically, when horizontal stress slightly exceeds vertical stress, the plastic zone extends more rapidly in the vertical direction. This results in a greater depth of failure in the roof and floor compared to the sidewalls. Conversely, under significantly high horizontal stress, the primary extension of the plastic zone shifts towards the shoulder and floor corners, forming a distinct X-shaped pattern. As horizontal stress increases, the development at these corners becomes predominantly vertical, resulting in a continuous increase in the maximum radius of the plastic zone. A key observation is that the acute angle of the X-shaped pattern remains largely constant throughout this process.

Evolution of the plastic zone in roadway surrounding rock with orthogonal joints under different lateral pressure coefficients

UDEC numerical modeling and mechanical parameters

A UDEC numerical model was developed based on the existing theoretical framework of butterfly-shaped plastic zone failure in surrounding rock28, as shown in Fig. 4. The model has dimensions of 80 m in length and 80 m in width, with a roadway diameter of 4.0 m. The rock mass near the roadway was discretized into rectangular blocks of 0.4 m side length, while the distant region was discretized into blocks of 0.8 m side length to enhance computational efficiency. A vertical load of 14.0 MPa was applied to the top boundary to simulate the gravitational stress from a 440 m thick overburden. The lateral pressure coefficient was considered by applying corresponding horizontal stresses to the left and right boundaries. Displacement constraints were applied to the lateral horizontal directions and the bottom vertical direction. The block material was modeled using the Mohr-Coulomb elastoplastic constitutive model, with interactions between blocks governed by the Coulomb slip model. The mechanical parameters for the intact rock blocks and joint properties, summarized in Tables 1 and 2, were selected based on rock mechanics test results from the reference study28.

Calibration of mechanical parameters in the numerical model

Extensive research, supported by field measurements, has investigated the plastic zone distribution in roadway surrounding rock under isotropic conditions. The joint parameters in the numerical model were initially set to match the block parameters, with mechanical property values listed in Tables 1 and 2, ensuring the rock mass in the model was isotropic. Numerical simulations were conducted to investigate the plastic zone distribution under various lateral pressure coefficients (λ = 0.4, 0.7, 1.0, 1.6, 2.2, 2.4), as shown in Fig. 5. The UDEC simulation results for the plastic zone under isotropic conditions closely align with the FLAC simulation results from the existing literature28. Additionally, the numerical results show strong consistency with the theoretical predictions of plastic zone evolution around isotropic roadway surrounding rock under different lateral pressure coefficients, as shown in Fig. 6. A comparative analysis of the plastic zone distribution from both numerical simulations and theoretical solutions for isotropic, orthogonally jointed roadway surrounding rock (based on Figs. 5 and 6) shows that their evolutionary patterns under different lateral pressure coefficients are consistent. This agreement aligns with the established theoretical framework of the butterfly-shaped plastic zone. Consequently, these findings validate the reliability of the adopted model and parameters.

A comparative analysis of Figs. 5 and 6 reveals a strong consistency and synchronicity between the simulation and theoretical results regarding the distribution, evolution, and failure characteristics of the plastic zone in isotropic, orthogonally jointed surrounding rock. A quantitative comparison of the plastic zone extents shows that the theoretically predicted zone is slightly smaller. This discrepancy arises because the theoretical calculation neglects the influence of the intermediate principal stress, simplifying the analysis of the stress state around the roadway.

In practical scenarios, however, stress redistribution caused by excavation continuously adjusts the surrounding rock stress field, driving further propagation of the plastic zone. This results in a generally larger plastic zone in the simulation compared to the theoretical solution.

As the lateral pressure coefficient increases, the maximum radius of the plastic zone from both methods shows an initial decrease followed by accelerated growth. As horizontal principal stress increases, both methods capture the characteristic evolutionary sequence of the plastic zone: butterfly-shaped → elliptical → circular → elliptical → butterfly-shaped.

When horizontal principal stress dominates, the plastic zone develops more rapidly in the roof and floor than in the sides, resulting in a vertically oriented elliptical shape. An increase in the lateral pressure coefficient further accelerates the development of the plastic zone at the shoulder and floor corners, compared to the roof, floor, and sides, leading to a distinct butterfly-shaped distribution. At this stage, a large-scale plastic failure zone develops in the surrounding rock. Conversely, when vertical principal stress dominates, the plastic zone is mainly confined to the sidewalls and shoulder corners, while the roof and floor remain elastic.

The close agreement in both the distribution and evolutionary patterns of the plastic zone under different confining pressures, as obtained from the two independent methods, validates the reliability of the numerical model and selected parameters.

An evolution analysis of the plastic zone for underground excavations in anisotropic rock mass

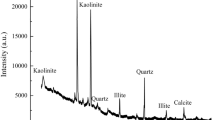

Numerous studies have shown that the mechanical parameters of bedding planes or joints are significantly lower than those of intact rock blocks, and the presence of these discontinuities introduces pronounced anisotropy to the rock mass. Therefore, based on the calibrated model, the mechanical parameters for bedding planes or joints were reduced (see Table 3), while the intact block properties remained unchanged.

The resulting evolutionary patterns of the plastic zone in the surrounding rock of the orthogonally jointed, anisotropic roadway under different lateral pressure coefficients, as obtained from simulations, are shown in Fig. 7. Analysis of Fig. 7 shows that, although the general evolutionary trend of the plastic zone with increasing horizontal principal stress aligns with that observed in isotropic strata, distinct differences arise in the distribution morphology.

For instance, under biaxial equal compression, the plastic zone in the anisotropic surrounding rock does not exhibit the typical circular distribution found in isotropic rock masses. Instead, it forms a regular, symmetrical “cross-shaped” pattern that extends along the joint sets. Furthermore, under low confining pressure, the plastic zone in the anisotropic surrounding rock develops distinct polygonal or angular patterns, as opposed to continuous curved surfaces. The plastic zone has a tendency to develop along the joint planes. This is because the joints in the anisotropic rock mass hinder the uniform evolution of in-situ stress, causing the plastic zone to develop along the joint planes and thus assume a characteristically angular morphology. In contrast, the homogeneous mechanical properties of isotropic strata lead to a continuous, smoothly curved stress distribution following excavation, resulting in a continuous plastic zone.

However, under excessively high confining pressure ratios, the plastic zone morphology converges between the two cases. Under high confining pressure, the rock mass primarily exhibits plastic behavior, resulting in increased overall strength. Under such high confinement, the presence of joints has a negligible effect on stress transfer within the surrounding rock. Consequently, the plastic zone in both isotropic and anisotropic models evolves into a continuous “X-shaped” configuration.

As shown in Fig. 7, when the lateral pressure coefficient is less than 1, the plastic zone at the sidewalls expands with decreasing horizontal in-situ stress. Concurrently, shear failure in the roof and floor gradually ceases and gives way to a certain degree of tensile failure. Under these conditions, the initial “cross-shaped” zone gradually transitions into a horizontal, band-like zone along the sidewalls. However, when the lateral pressure coefficient decreases to 0.3, the plastic zone undergoes a remarkable transformation, evolving into a distinct butterfly-shaped pattern that expands sharply from the shoulder and floor corners. This signifies a critical transition from localized shear failure to global rock instability, characterized by tensile-shear composite failure.

When the lateral pressure coefficient exceeds 1, the sidewalls maintain stable, uniform shear failure, while the shear-induced plastic zone in the roof and floor propagates progressively deeper into the surrounding rock. Meanwhile, the horizontal extent of the roof and floor plastic zones progressively increases. At this stage, the “cross-shaped” zone transitions into a predominantly vertical, band-like zone along the roof and floor.

As the in-situ stress field evolves toward a horizontally dominant state, the plastic zones in the sidewalls propagate progressively deeper. Furthermore, the plastic zone propagates at a slightly higher rate in the upper and lower sections of the sidewalls than in the central part. Simultaneously, the roof and floor plastic zones cease propagating inward and begin to extend obliquely at roughly 45-degree angles from the corners. These zones eventually coalesce, forming a large, integrated X-shaped plastic zone. At this stage, the surrounding rock has reached a state of through-going plastic failure, indicating that large-scale deformation of the excavation is imminent.

Furthermore, when the horizontal principal stress is either too high or too low, the plastic zone radius at the shoulder corners significantly enlarges. This indicates that the growth rate of the plastic zone radius is highly sensitive to both excessively high and low confining pressures.

Figure 8 shows the contour plots of the maximum principal stress distribution in the surrounding rock of an orthogonally jointed anisotropic roadway under various lateral pressure coefficients. Analysis of Fig. 8 shows that when the lateral pressure coefficient is small, the bearing capacity of the roof and floor is significantly reduced, leading to roof subsidence and floor heave. Meanwhile, stress concentration in the sidewalls leads to noticeable squeezing deformation. Under these conditions, the roadway becomes highly unstable.

Under near-isotropic stress conditions, the maximum principal stress exhibits a smooth and uniform cruciform distribution, intensifying in a graded manner from the excavation surface into the deep rock mass. In this scenario, stress concentration is significantly reduced. Failure is confined to a shallow fractured zone near the roadway surface, while the deep surrounding rock remains intact and elastic.

As the lateral pressure coefficient increases and the horizontal principal stress becomes dominant, significant stress concentration develops at the shoulder and floor corners. This culminates in large-deformation failure, marked by reduced roof/floor bearing capacity, high sidewall stress concentration, and expanding pressure-relief zones at the corners that coalesce into the surrounding rock.

Based on the foregoing analysis, it is clear that as the lateral pressure coefficient increases, the plastic zone in the orthogonally jointed anisotropic surrounding rock evolves through a distinct morphological sequence: butterfly-shaped → horizontal band-shaped → regular cross-shaped → vertical band-shaped → X-shaped.

Specifically, As the horizontal principal stress increases, the failure mode in the roof and floor transitions from superficial tensile failure to shear failure, ultimately evolving into a large-deformation failure characterized by an interconnected plastic zone. This evolutionary pattern demonstrates the significant influence of both in-situ stress conditions and joint characteristics on the morphology of the plastic zone.

Under moderate confining pressures, both models exhibit similar locations and developmental trends in their plastic zones compared to the isotropic case. The plastic zone in the anisotropic rock mass typically displays an angular, geometry-controlled pattern along the joint planes, with localized stress concentrations at joint intersections. In contrast, under excessively high or critically low confining pressures, the plastic zone morphologies in both isotropic and anisotropic models converge. This convergence occurs because high stress conditions reduce the structural control exerted by the joints. This indicates that the in-situ stress environment plays a more dominant role than anisotropic jointing in determining both the final morphology of the plastic zone and the resulting failure mode of the surrounding rock.

In deep roadways, the in-situ stress environment is significantly influenced by factors such as high ground stress, surrounding rock properties, and excavation geometry. These factors can change the orientation of the principal stresses in the surrounding rock. In deep mining conditions, the combined influence of tectonic and gravitational stresses typically leads to a horizontally dominant stress field. A lateral pressure coefficient of 1.5 represents tectonically active regions and more accurately reflects the mechanical response of the surrounding rock under high-stress conditions. Therefore, this study uses a lateral pressure coefficient of 1.5. The model and joint parameters are consistent with those in Tables 1 and 3, while all other parameters remain unchanged.

To investigate the influence of principal stress rotation, seven scenarios were analyzed with the angle between the principal stress direction and the horizontal axis varying in 15° intervals: 0°, 15°, 30°, 45°, 60°, 75°, and 90°. The expansion trends of the plastic zone distribution and the evolution of the maximum principal stress in the orthogonally jointed, anisotropic surrounding rock under these rotation angles are shown in Figs. 9 and 10, respectively.

As shown in Figs. 9 and 10, as the principal stress rotation angle increases from 0° to 90°, the plastic zone distribution follows a distinct evolutionary sequence: “vertical band-shaped” → “cross-shaped” → “horizontal band-shaped.” This evolution is characterized by the maximum plastic radius shifting from the sidewalls, through the shoulder and floor corners, and ultimately developing along the roof and floor. Both the plastic zone and the maximum principal stress distribution exhibit perfect symmetry around the 45° rotation angle, with the evolutionary direction of the plastic zone aligning closely with the principal stress rotation.

With the principal stress direction unaltered (0°), the dominant horizontal stress triggers widespread plastic failure in the roof and floor (i.e., the vertical direction). As the principal stress rotates, the horizontal component of the horizontal stress gradually decreases. Consequently, the maximum radius of the plastic zone in the roof and floor progressively decreases, while it increases in the sidewalls. Meanwhile, the plastic zone at the shoulder corners expands.

At a principal stress rotation of 45°, the projection components of the maximum and minimum principal stresses in both the vertical and horizontal directions become equal. The resulting plastic zone is approximately cross-shaped, closely resembling the pattern typically formed by a set of conjugate symmetric joints under primary rock stress.

Notably, despite the rotation of the principal stress, the magnitude of the maximum principal stress in the surrounding rock remains largely unchanged. The deep surrounding rock maintains a consistent maximum principal stress of 20 MPa, while a pressure relief zone near the excavation boundary reduces this value to 3 MPa in the shallow rock. The orientation of the maximum principal stress transitions from horizontal to vertical.

Regardless of the in-situ stress rotation, the primary extension direction of the plastic zone shifts from vertical to horizontal, always maintaining an orthogonal pattern aligned with the joint sets, rather than developing obliquely with stress rotation. This demonstrates that plastic zone development along joint directions is the dominant characteristic of orthogonally jointed anisotropic rock masses. The primary extension direction of the plastic zone consistently aligns perpendicular to the maximum principal stress and propagates deeper into the rock mass.

Evolution of the plastic zone in roadway surrounding rock with non-orthogonal joints under different lateral pressure coefficients

Plastic zone evolution in surrounding rock of jointed roadways with varied dip angles

Coal seams in China exhibit a wide range of dip angles, from sub-horizontal to nearly vertical. To investigate the influence of rock bedding on the plastic zone in roadway surrounding rock, we systematically simulated and analyzed the stress field and plastic zone development in rock masses with a single set of bedding planes at different dip angles (0°, 15°, 30°, 45°, 60°, 75°, 90°). The lateral pressure coefficient was set to 1, with joint and block parameters identical to those in the prior simulations. The numerical simulation results for the evolution of the plastic zone, stress field redistribution, and surrounding rock deformation are presented in Figs. 11 and 12.

As shown in Figs. 11 and 12, as the joint dip angle transitions from 0° to 90°, the primary extension direction of the plastic zone gradually shifts from a horizontal “band-shaped” pattern to a vertical “band-shaped” pattern. Throughout this process, the primary extension direction of the plastic zone remains closely aligned with the joint dip angle. Regardless of the joint dip angle, both the maximum principal stress and the plastic zone distribution exhibit symmetry along the joint dip angle as the axis of symmetry.

Notably, regardless of the joint dip angle, the pressure relief zones and the plastic zone in the surrounding rock develop only in the shallow region around the roadway. The maximum radius of the plastic zone is merely 4 m. Under these conditions, surrounding rock deformation remains small, with only slight fracturing confined to the immediate roadway surface, thus presenting fewer challenges for support.

Under geological conditions involving a single set of joints with varying dip angles, the maximum principal stress in the deep surrounding rock generally stabilizes around 21 MPa, consistent with the initial in-situ stress field. The stress state of the surrounding rock remains largely unchanged. This is because a single set of joints has a limited structural impact on the rock mass surrounding the roadway. When the internal friction angle exceeds a critical threshold, shear slippage may occur along the joint planes, causing roadway deformation and failure. Otherwise, the roadway remains in a stable state. Therefore, with a single joint set maintained constant, varying its dip angle induces no significant change in the maximum principal stress or the maximum radius of the plastic zone.

Although the initial simulation conditions were set to an isotropic stress state, the plastic zone distribution did not manifest the “cross-shaped” or “circular” patterns mentioned earlier. Instead, it consistently showed a “band-shaped” distribution along the joints. In rock masses with a single joint set, plastic zones develop locally in the direction perpendicular to the joints, whereas the dominant development consistently aligns with the joint direction. This demonstrates that joint characteristics significantly influence the extension direction and evolutionary trend of the plastic zone, as well as the distribution of the maximum principal stress in the surrounding rock.

Plastic zone evolution in surrounding rock of multi-jointed roadways with varied dip angles

Under actual engineering geological conditions, rock strata often contain multiple joint sets due to tectonic influences, leading to a more complex in-situ stress distribution. The anisotropy of rock masses containing multiple joint sets is markedly enhanced. In such rock masses, roadway excavation gives rise to a complex surrounding stress field, which in turn produces a plastic zone with distinctly anisotropic features.

To investigate the influence of multiple non-orthogonal joint sets on the stability of roadway surrounding rock, a simulation study examined the differences in the stress field and plastic zone distribution under various in-situ stress condition. The evolutionary patterns of the plastic zone under different intersection angles of multiple joint sets were obtained, along with the deformation and failure characteristics of the roadway under varying lateral pressure coefficients and principal stress rotation angles in non-orthogonally jointed strata.

The model contained two sets of conjugate joints dipping symmetrically about the vertical plane. One set had a dip angle of θ, and the other had a dip angle of 180°−θ. The dip angles for one joint set were 10°, 20°, 30°, 40°, 50°, 60°, 70°, and 80°. The numerical results reveal the evolution of the plastic zone, the stress field redistribution, and the surrounding rock deformation, as presented in Figs. 13 and 14.

As shown in Figs. 13 and 14, the plastic zone and the maximum principal stress distribution are both symmetric about the vertical plane, and the morphology of the former corresponds well with the latter. When the two conjugate joint sets are sub-horizontal or sub-vertical, they become mechanically equivalent to a single set of continuous horizontal or vertical joints. Under these conditions, both the plastic zone and maximum principal stress distribution primarily develop along the horizontal or vertical direction. The maximum radius of the plastic zone in the sidewalls or roof and floor reaches high values, with roadway failure mainly manifesting as rib spalling, roof subsidence, or floor heave.

As the conjugate joint sets transition from horizontal to vertical (or vice versa), the maximum radius of the plastic zone at the shoulder corners gradually expands, while the maximum radii in the roof-floor and sidewall directions decrease show a decreasing trend. However, an “anomalous peak” occurs during this transition. This occurs because a slight deviation from a nearly horizontal or vertical dip is mechanically equivalent to introducing a second, symmetrically oriented joint set into the rock mass. The increased number of joint sets enhances rock mass fragmentation, widening the block size distribution and intensifying stress concentration in the surrounding rock. This leads to an abnormal increase in the maximum plastic zone radius in both the roof-floor and sidewall directions.

The conjugate joints at 40° and 50° dips can be conceptualized as a rotated orthogonal joint system. The resulting plastic zone and stress distributions are congruent with the orthogonal joint case, up to a rotation. The rock mass fragmented by these joint sets is highly homogeneous, yielding blocks of near-cubic shape. Compared to the pyramidal blocks formed by joints with other orientations, these cubic blocks facilitate more uniform stress transfer. The interfaces between the two joint sets form two perfectly aligned block tips that can effectively withstand the applied loads. The plastic zone’s maximum radius attains a global minimum, with only localized shear failure occurring at the shoulder and floor corners The overall stability of the roadway under these conditions remains high.

Based on the foregoing analysis, The evolution of the plastic zone morphology with joint dip angle (from sub-horizontal to 45°) can be summarized as a band-to-asterisk-to-X sequence. For angles increasing from 45° to sub-vertical, the sequence reverses, completing a symmetrical pattern of evolution. This indicates that as the two sets of conjugate symmetrical joints become more aligned, the primary extension direction of the plastic zone transitions from divergent to concentrated. The overall evolutionary pattern is characterized by a migration of both the plastic zone and the maximum principal stress from the roof, floor, and sidewalls toward the shoulder and floor corners of the excavation.

Therefore, it is evident that the evolution of both the plastic zone and the maximum principal stress is governed by the orientation of the joints, extending strictly along and perpendicular to them. Notably, the extent of development differs in these two principal directions. Compared to the direction perpendicular to the joints, the plastic zone propagates deeper along the joint direction.

The symmetric joint model has a fundamental limitation: it cannot capture the inherent structural asymmetry of natural rock masses, which typically contain both dominant and secondary joints. The dominant joint set, influenced by regional tectonic activity, usually has a fixed dip angle. In contrast, secondary joints, formed by prolonged tectonic evolution or local stress perturbations, typically exhibit a broad spectrum of dip angles. The presence of this asymmetric master-secondary joint system causes the rock mass to exhibit mechanical behaviors that show a marked departure from the predictions of idealized symmetric models.

To investigate this phenomenon, a dominant joint set with a fixed dip angle of 45° was defined, while the dip angle (α) of the secondary joint set was varied from 0° to 90° in 10° increments (10°, 20°, 30°, 40°, 50°, 60°, 70°, 80°, 90°). A lateral pressure coefficient of 1 was applied, and all other model and joint parameters were kept consistent with previous simulations. The resulting distribution patterns and evolutionary characteristics of the plastic zone and maximum principal stress in the surrounding rock are shown in Figs. 15 and 16.

As shown in Figs. 15 and 16, with the dominant joint fixed at 45°, both the plastic zone and maximum principal stress distribution evolve distinctly as the secondary joint angle changes. When the secondary joint angle increases from 0° toward 45°, the plastic zone and stress distribution transition from an inclined “asterisk-shaped” pattern to a “band-shaped” configuration. Conversely, as the secondary joint angle increases from 45° toward 90°, the distribution transforms from an inclined “band-shaped” pattern to an “asterisk-shaped” configuration.

This evolutionary behavior results from the changing spatial relationship between the two joint sets. As the secondary joint angle approaches the dominant joint angle (45°), the two joint sets gradually converge and ultimately coincide, forming a single well-developed joint set penetrating the roadway. This convergence creates a superposition effect of plastic failure along the joint direction, leading to a wide band-shaped distribution of both the plastic zone and maximum principal stress. Except for minor plastic zones developing perpendicular to the joint direction, almost no plastic failure occurs in other directions, resembling the characteristics observed in the single 45° joint set case discussed earlier.

Similarly, the progressive divergence of the secondary joint orientation from the dominant set can be mechanically equivalent to the introduction of an additional joint set into the rock mass. Under these conditions, the plastic zone evolves from a band-shaped pattern to a diverging “asterisk-shaped” distribution.

A clear correlation is observed: for secondary joint angles below the dominant 45° dip, the plastic zone’s primary extension plane ranges from 0° to 45°, with its angle converging toward 45° as the secondary joint angle increases. Similarly, when the secondary joint angle exceeds 45°, the dip angle of the primary extension plane ranges from 45° to 90°, gradually approaching 90° as the secondary joint angle increases.

Although the evolutionary patterns of the plastic zone and maximum principal stress distribution remain consistent across both stages, the presence of the dominant joint fundamentally influences the orientation of the primary extension plane. This influence creates a distinct angular difference in the extension directions between the two stages, with this angular difference being directly related to the angle of the dominant joint set.

Therefore, the morphology of the plastic zone is governed by the combined influence of both the dominant and secondary joint sets. When the two joint sets have similar dip angles, their individual plastic failure zones merge and form a continuous, band-like structure. Conversely, a marked difference in dip angles causes the plastic zone to develop into a diverging, asterisk-shaped pattern.

Consequently, the plastic zone develops and propagates preferentially along the joint direction and, to a lesser extent, perpendicular to it, with development along the joint direction being significantly more pronounced. Furthermore, the primary extension plane of the plastic zone consistently aligns within the angular range between the dip angles of the two joint sets, while the secondary extension plane remains perpendicular to the primary one.

Considering the potential presence of multiple dominant joint sets in complex geological structures, this study further investigates the distribution patterns and evolutionary characteristics of the plastic zone in roadway surrounding rock. The investigation focuses on the rock mass under the combined influence of two sets of conjugate symmetrical dominant joints and secondary joints, the latter being formed by mining activities or regional tectonics with varying dip angles and strikes. Two dominant joint sets with fixed dip angles of 50° and 130° were established, while the dip angle (β) of the secondary joints varied in 15° increments: 0°, 15°, 30°, 45°, 60°, 75°, and 90°. A lateral pressure coefficient of 1 was maintained, and the boundary conditions and joint parameters were consistent with those of previous models.

The numerical results provided insights into the anisotropic characteristics of the plastic zone distribution and the evolutionary patterns of the maximum principal stress field in the surrounding rock of the multi-jointed roadway, as shown in Figs. 17 and 18.

As shown in Fig. 17, the plastic zone in the surrounding rock evolves from a “hexagonal” pattern to an “X-shaped” configuration with an increase in the dip angle of the secondary joints. When the joint dip angle is 0°, three primary extension planes form along the three joint sets in the surrounding rock. At a 90° joint dip angle, the plastic zone distribution is essentially equivalent to that at 0° subjected to a 90° counterclockwise rotation. However, Compared to the 0° case, the plastic zone is more extensive and the stress distribution is more uniform.

At joint dip angles of 45° and 60°, the plastic zone assumes a distinct X-shaped configuration. In this scenario, the three joint sets can be approximated by a model of two symmetrical and orthogonal sets, since the third set’s orientation converges with that of the fixed 50° dip joint. The primary extension planes of the plastic zone are collinear with the joint dip angles, resulting in two main fracture planes oriented along the orthogonal joint directions and arranged in an X-shaped pattern. This pattern bears a strong resemblance to the plastic zone distribution observed for the conjugate symmetrical joints at 40° and 50°; in both cases, failure is concentrated at the shoulder and floor corners. Under these conditions, both the extent of the plastic zone and the magnitude of the maximum principal stress remain relatively low. This is because the third joint set aligns with the fixed joints, which reduces the fragmentation effect of multiple joint sets on the surrounding rock. The rock mass, intersected by approximately conjugate symmetrical joints, forms a new interlocking structure, enhancing the overall integrity of the surrounding rock.

Figure 18 shows that the evolutionary trend of the maximum principal stress distribution in the surrounding rock of the roadway with multiple non-orthogonal joint sets aligns with that of the plastic zone distribution. When the dip angle of the third joint set is 30° or lower, high-stress zones easily form in the deep surrounding rock. The integrity of the rock mass is compromised by the multiple joints, resulting in its disintegration into a blocky structure. As a result, fragmented rock blocks often create pressure relief zones near the roadway surface, leading to phenomena such as roof bulging or “mesh bag” deformation. As the secondary joint dip angles increase to 45° and 60°, the principal stress in the deep surrounding rock decreases. The decrease in principal stress is attributed to the reduced rock mass fragmentation by the joints, promoting a more stable deep in-situ stress regime. As the joint dip angle increases further, the high-stress zones in the roof, floor, and sidewalls gradually expand and coalesce into a butterfly-shaped pattern. Asymmetric deformations, such as roof subsidence and floor heave, often occur in the right roof and left floor areas of the roadway under these conditions.

Based on the above analysis, it can be concluded that the plastic zone reaches its minimum radius when the dip angles of the secondary joints are 45° and 60°. Under these conditions, the surrounding rock remains predominantly elastic, without significant pressure relief, resulting in maximum roadway stability. However, As the joint dip angles deviate from this optimal range, they progressively fragment the rock mass through intersecting patterns. This fragmentation decreases the overall integrity of the surrounding rock. These observations show that the orientation and development characteristics of internal joint sets in the rock mass significantly influence the evolution of the plastic zone and the distribution of the maximum principal stress, ultimately leading to differential stress transfer.

Plastic zone evolution in surrounding rock of roadways with non-orthogonal joints under various stress environments

Numerical simulations were conducted to investigate the evolution of the plastic zone and deformation behavior of surrounding rock in non-orthogonally jointed rock masses under various lateral pressure coefficients. Two sets of non-orthogonal joints were defined in the model, with dip angles of 45° and 90° respectively. The lateral pressure coefficient ranged from 0.4 to 2.4, with joint and intact rock parameters consistent with previous simulations. The resulting evolution of the plastic zone in the roadway surrounding rock is shown in Fig. 19.

As shown in Fig. 19, a lateral pressure coefficient of 1 results in a failure mode characterized by minor tensile failure at the surface and predominant shear failure at depth. The plastic zone generally exhibits an “asterisk-shaped” pattern, with primary extension directions oriented toward the upper right and lower left of the roadway, while failure in the sidewalls remains limited.

As the lateral pressure coefficient decreases, the plastic zone progressively assumes a diamond-star configuration. Tensile failure at the roadway surface becomes more pronounced, with the primary extension direction of the plastic zone gradually shifting from the upper right and lower left areas toward the sidewalls. Simultaneously, the maximum radius of the plastic zone propagates further into the rock mass.

However, when horizontal stress exceeds vertical stress, the primary extension direction of the plastic zone shifts to the shoulder and floor corners. Furthermore, the plastic zone propagates progressively deeper into the roof and floor with increasing horizontal principal stress.

Under high horizontal in-situ stress, the plastic zone in the sidewalls propagates rapidly and eventually coalesces with the zones at the shoulder and floor corners. This interconnection forms an irregular, large-scale plastic failure region.

This analysis demonstrates that the plastic zone morphology transitions sequentially from rhomboid to asterisk and finally to X-shaped with increasing lateral pressure coefficient in the anisotropic, non-orthogonally jointed rock mass.

Compared to isotropic and orthogonally jointed anisotropic rock masses, the plastic zone morphology in the non-orthogonal case shows significant differences. Under different confining pressure ratios, the plastic zone in the non-orthogonal case exhibits an irregular and asymmetric pattern, resulting in uneven and asymmetric large-scale deformation failures in the roadway. This response stems from the segmentation of the rock mass by asymmetric, irregular joints into a rhombic block structure. These rhomboid blocks results in greater complexity in load transfer compared to the cubic structure of orthogonal joints or the homogeneity of isotropic rock. The numerous interfaces and contact elements between the rhomboid blocks significantly influence the mechanical behavior, thereby exerting a controlling effect on in-situ stress transfer and distribution. As a result, the plastic zone develops an irregular and asymmetric distribution, aligning with the geometry of the rhomboid blocks and asymmetric joint planes.

However, all three cases share a common evolutionary pattern: the plastic zone’s primary extension reorients from horizontal to vertical with increasing horizontal principal stress. In other words, regardless of the specific distribution morphology, the evolutionary trend with increasing lateral pressure coefficient always shifts from predominantly lateral widening to predominantly vertical deepening. This demonstrates that while joint distribution within the rock mass primarily governs the specific morphology of the plastic zone, the lateral pressure coefficient plays a decisive role in determining its primary extension direction and overall evolution.

The excavation of deep roadways and the subsequent formation of a goaf create a extensive cantilevered overhang in the roof, inducing fracture, rotation, and displacement of the overlying strata. This causes the rotation of the principal stress directions. A numerical model was established—featuring non-orthogonal joint sets at 45° and 90°—to simulate the stress distribution and failure behavior of the surrounding rock under the specified conditions. The rotation angle of the principal stresses was varied as the key parameter, with increments of 15°, covering cases of 0°, 15°, 30°, 45°, 60°, 75°, and 90°. The lateral pressure coefficient was set to 0.5, with all other parameters consistent with previous simulations. The evolution of the plastic zone under different principal stress rotation directions is summarized in Fig. 20.

As shown in Fig. 20, the plastic zone morphology evolves with increasing principal stress rotation, transitioning through diamond-star, asterisk, and X-shaped patterns. When the principal stresses are unrotated (0°) and the vertical principal stress dominates, the plastic zone propagates primarily from the sidewalls into the deeper surrounding rock. As the rotation angle increases, the primary extension direction of the plastic zone shifts gradually toward the roof and floor, eventually forming an “X-shaped” distribution that propagates deeply along the shoulder and floor corners of the roadway.

The rotation of the principal stresses can be mechanically equated to an increase in the lateral pressure coefficient, as both result in a reorientation of the in-situ stress field from vertically dominant to horizontally dominant. This evolutionary pattern—from a diamond-star to an X-shaped plastic zone—closely parallels the trend previously described for non-orthogonally jointed rock under varying lateral pressure coefficients. The principal direction of plastic zone extension transitions from lateral to vertical. Notably, however, the orientation of the primary extension plane of the plastic zone consistently aligns with the rotation angle of the principal stresses. Additionally, the plastic zone reaches its minimum extent at a principal stress rotation angle of 60°. This is because, at this angle, the stress components along the 45° and 90° joint directions are minimized.

The principal stress rotation has a profound impact on the evolution of deformation and failure mechanisms in roadways excavated in non-orthogonally jointed rock masses. This influence is mainly observed in the transformation of the plastic zone morphology, the reorientation of its primary extension direction, and the shift in the locations of large-scale deformation zones as the principal stress direction rotates. Furthermore, a tight coupling exists between the rotation direction of the principal stresses and the primary extension direction of the plastic zone.

Case study of asymmetric large deformation in surrounding rock of a roadway with inclined bedding

Engineering background

The Xin’an Coal Mine is situated in Pingliang City, Gansu Province. The coal seams in this mining field are deeply buried, with main roadways at depths of 750 to 900 m. The + 535 m return air roadway is located at a depth of about 720 m. The roadway has a straight-walled semi-circular arch cross-section, with a width of 5.0 m and a height of 4.0 m. The upper semi-circular arch has a radius of 2.5 m. The surrounding rock of the main ventilation roadway is composed mainly of mudstone and sandstone, dipping at 10°. The immediate roof and floor strata are sandstone. These rocks are classified as soft and incompetent. The average rock block strength of the surrounding rock is 10 MPa, while the estimated rock mass strength ranges from 2.5 to 7.0 MPa. Mudstone and sandy mudstone, which form the immediate floor, exhibit poor mechanical strength and possess water-swelling properties, rendering them incompetent. In contrast, siltstone and fine sandstone in the floor sequence demonstrate relatively higher strength. The roadway is supported by a combination of rock bolts, wire mesh, and shotcrete.

The overburden depth of 750 m in the Xin’an Coal Mine results in a gravitational stress of approximately 19 MPa. Geotectonically, the mine is situated in the southeastern part of the Ankou–Xinyao Coalfield, where both the Ankou–Xinyao Coalfield and the mine area lie within a composite structural zone formed by the Qilian–Lüliang–Helan Mountains “zigzag” tectonic belt and the Longxi rotational structure system. This structural setting has subjected the region to compressional forces oriented nearly NE–SW, leading to a predominant geostress orientation that is approximately E–W to NE–SW. In-situ stress measurements indicate a maximum principal stress of 31 MPa with an azimuth of 66° and a dip angle of 8°, and a minimum principal stress of 16.5 MPa with an azimuth of 336° and a dip angle of − 7°.

The combined action of in-situ stress and bedding planes has induced differential asymmetric failure with large deformations in the roadway surrounding rock. This is primarily characterized by significant convergence of the surrounding rock into the free space, resulting in various deformation damages. The primary failure modes include roof bulging, floor heave, roof subsidence, and sidewall convergence.

Failed rock has piled up as discrete blocks at the right shoulder corner of the return airway. A “mesh bagging” effect has developed within the bolt-mesh-shotcrete support, combined with noticeable roof subsidence and sidewall convergence. The complex stress field induced by stress concentrations at the roadway shoulder places higher demands on the load-bearing capacity of the bolts and cables. This overloading has resulted in the tearing of the wire mesh and the shearing failure of the bolts and cables.

Additionally, significant floor heave has occurred, with the left side of the roadway exhibiting more severe deformation, which gradually decreases toward the right side. The deformed floor profile resembles an irregular triangle, indicating partial functional failure of the roadway, as shown in Fig. 21.

Roof bulge in + 535 return air roadway of Xinan coal mine32.

The Xin’an Coal Mine features rock strata with a bedding dip angle of 10° and complex, varied lithological distributions, classifying the surrounding rock as anisotropic. The excavation-induced stress redistribution has created complex geomechanical conditions around the + 535return airway.

In contrast to the relatively uniform deformation of isotropic rock masses, the anisotropic surrounding rock here manifests distinct failure characteristics marked by greater deformation magnitude, broader failure extent, and pronounced heterogeneity. The interaction between in-situ stress and bedding planes, combined with the contrasting mechanical properties of different rock types, intensifies the anisotropic nature of the surrounding rock. The presence of anisotropic joints induces a differential mechanical response to in-situ stress across different spatial directions within the surrounding rock. As a result, the + 535return airway at Xin’an Coal Mine experiences pronounced asymmetric deformation, as shown in Fig. 21.

Numerical analysis of failure mechanisms in roadways within typical anisotropic formations

Taking the + 535 m return airway of the Xin’an Coal Mine as the engineering background, a representative stratigraphic model was developed utilizing data from borehole core samples and subsequent geological analysis and classification. The model dimensions are 60 m×55 m. The model’s upper boundary was assigned a stress boundary condition; a vertical stress of 16.2 MPa, equivalent to the overburden pressure from the average rock density, was applied to the top surface. The model’s sides and bottom were fixed against horizontal and vertical displacement, respectively.

Four surface monitoring points were established to monitor roadway displacements at the roof, floor, and both sidewalls. Additional points were placed at 1 m intervals in each direction, extending into the deep surrounding rock, bringing the total to 44 monitoring points. The numerical model and layout of the surface monitoring points are shown in Fig. 22.

Parameter calibration was performed using the intact rock and rock mass properties from Reference32, as summarized in Table 4. The stress-strain curve from the simulated uniaxial compression test is shown in Fig. 23. The physical and mechanical parameters of the rock layers and joint surface parameters after calibration are summarized in Tables 5 and 6, respectively.

Figure 24 presents the distributions of the plastic zone and displacement contours in the surrounding rock after the roadway excavation. Comparison with field photographs reveals consistent failure modes: severe floor heave on the left side, significant roof subsidence at the right arch crown, and inward squeezing of both sidewalls, leading to asymmetric deformation. The plastic failure zone develops along both the dip direction of the bedding planes and the perpendicular direction, forming an approximate “cross-shaped” pattern centered on the roadway.

The displacement contour distribution shows that maximum displacement occurs near the left-side floor and the arch crown, manifesting as intense floor heave and roof subsidence.

Monitoring data from measuring points at the roof, floor, and both sides of the roadway were used to obtain the vertical displacements of the roof and floor and the horizontal displacements of the sidewalls, as shown in Fig. 25. After stress stabilization, the simulated displacements of the left and right sidewalls were 768 mm and 510 mm, respectively, compared to field-measured displacements of 568 mm and 510 mm. The field-measured displacements of the roof and floor were 640 mm and 480 mm, respectively, while the simulated displacements were 680 mm and 746 mm. This analysis demonstrates that the simulation results generally agree with the field measurements, confirming the reliability of the parameters and the joint model.

Conclusion

The specific findings are as follows:

(1) A theoretical model was developed to describe the failure behavior of roadway surrounding rock in anisotropic formations. The principal stresses and the distribution range of the plastic zone were derived analytically. The differences in plastic zone characteristics between anisotropic and isotropic formations under varying lateral pressure coefficients were analyzed. Under non-hydrostatic pressure conditions, as the lateral pressure coefficient deviates from unity, the plastic zone gradually evolves from an elliptical to an “X”-shaped form. However, under anisotropic conditions, the extent of the plastic zone is more strongly influenced by joint structures than under isotropic conditions.

(2) In formations containing a single set of joints, the plastic zone shows a banded distribution along the joint dip and rotates synchronously with variations in joint inclination. In contrast, around excavations in rock masses with multiple joint sets, the plastic zone extends both along and perpendicular to the dominant joint orientations, with preferential and more pronounced extension observed along the joint directions.

(3) For isotropic, orthogonally jointed, and non-orthogonally jointed roadways, the lateral pressure coefficient exerts a significant influence on the morphology and evolutionary trend of the plastic zone. Under both low and high confining pressures, the maximum radius of the plastic zone at the roadway shoulders in orthogonally jointed formations increases rapidly, with a growth rate of up to 170%.

(4) A field case was analyzed to investigate the deformation and failure characteristics of surrounding rock in anisotropic formations. A numerical model of a roadway within inclined bedding formations was constructed. Simulation results show that the plastic zone exhibits a distinct “X”-shaped pattern along bedding or joint directions, and the surrounding rock experiences pronounced asymmetric deformation. The numerical simulation results are generally consistent with field measurements, thereby validating, to a certain extent, the rationality of the proposed model.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Pan, W. et al. Coal burst prevention technology and engineering practice in Ordos deep mining area of China. Sustainability 15 (1), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010159 (2022).

Sun, H., Dai, L., Lu, J., Cao, J. & Li, M. Analyzing energy transfer mechanism during coal and gas protrusion in deep mines. Processes 10 (12), 2634. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10122634 (2022).

Liu, X., Feng, X., Zhou, Y. & Sharifzadeh, M. Influences of foliation orientation and lateral stress difference on the deformation and fracturing of a thin-layered rock around underground excavations: insight from multi-axial loading tests. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 81 (5), 171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-022-02648-5 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Numerical simulation of Spatial distributions of mining-induced stress and fracture fields for three coal mining layouts. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 10 (5), 907–913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2018.02.008 (2018).

Yu, M., Zuo, J., Sun, Y., Mi, C. & Li, Z. Investigation on fracture models and ground pressure distribution of Thick hard rock strata including weak interlayer. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 32 (1), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2021.10.009 (2022).

Kang, H., Zhang, X., Si, L., Wu, Y. & Gao, F. In-situ stress measurements and stress distribution characteristics in underground coal mines in China. Eng. Geol. 116 (3–4), 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2010.09.015 (2010).

Liu, T. et al. Cracking process and stress field evolution in specimen containing combined flaw under uniaxial compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49 (8), 3095–3113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-016-0982-4 (2016).

Wang, W., Fan, L., Zhao, Z. & Han, S. Research progress of support theory and technology of the roadway surrounding rock based on the plastic zone control. J. China Coal Soc. 49 (01), 320–336. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2023.1412 (2024).

Paul, S. K. Numerical models of plastic zones and associated deformations for elliptical inclusions in remote elastic loading–unloading with different R-ratios. Eng. Fract. Mech. 152, 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2015.12.008 (2016).

Zhao, Z. et al. Study on mechanism and control method of deformation and failure of surrounding rock in large deformation mining roadway. J. China Coal Soc. 41 (11), 2689–2697. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2016.0786 (2016).

Li, X., Huan, Z., Li, X. & Gong, F. Fracture patterns induced by deep underground excavation based on a crack propagation model. J. China Coal Soc. 44 (5), 1378–1390. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2019.6036 (2019).

Wang, W., Dong, E. & Yuan, C. Boundary equation of plastic zone of circular roadway in non-axisymmetric stress and its application. J. China Coal Soc. 44 (01), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2018.5035 (2019).

Wang, W. et al. Fracture distribution and deformation mechanism of surrounding rock in two-way extremely unequal pressure soft rock roadway. J. China Coal Soc. 49 (07), 3025–3037. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2023.0913 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Similar simulation study on the deformation and failure of surrounding rock of a large section chamber group under dynamic loading. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 31 (3), 495–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2021.03.009 (2021).

Jing, H., Wu, J., Yin, Q. & Wang, K. Deformation and failure characteristics of anchorage structure of surrounding rock in deep roadway. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 30 (5), 593–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2020.06.003 (2020).

Yuan, C., Cao, L., Fan, L. & Guo, J. Theoretical analysis on distribution pattern of plastic zone in surrounding rock of high-gas‐coal roadway. Adv. Civil Eng. 2021 (1), 6684243. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6684243 (2021).

Hu, X., He, C., Walton, G. & Chen, Z. A combined support system associated with the segmental lining in a jointed rock mass: the case of the inclined shaft tunnel at the bulianta coal mine. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 53 (6), 2653–2669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-020-02056-9 (2020).

Gu, L. Excavation stress path induced fracturing mechanism of hard rock in deep tunnel. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56 (3), 1779–1806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-022-03151-9 (2023).

Chen, Q., Zuo, Y., Lin, J., Chen, B. & Zheng, L. Numerical research on response characteristics of surrounding rock for deep layered clastic rock roadway under static and dynamic loading conditions. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resources. 8 (3), 91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-021-00329-3 (2022).

Liu, D., Zuo, J., Wang, J., Zhang, T. & Liu, H. Study on large deformation mechanism and concrete-filled steel tubular support technology for ventilation shaft roadway. Eng. Fail. Anal. 116, 104721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2020.104721 (2020).

Wen, J., Zuo, J., Wang, Z., Wen, Z. & Wang, J. Failure mechanism analysis and support strength determination of deep coal mine roadways–A case study. Constr. Build. Mater. 443, 137704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137704 (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. Analysis of surrounding rock stress and plastic zone of two-way unequal pressure circular roadway based on complex variable theory. J. China Coal Soc. 44 (S2), 419–429. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2019.1208 (2019).

Ma, Z., Zuo, J., Zhu, F., Liu, H. & Xu, C. Non-orthogonal failure behavior of roadway surrounding rock subjected to deep complicated stress. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56 (9), 6261–6283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-023-03397-x (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Research on Stope equivalent hole model and rotation law of principal stress. J. China Coal Soc. 48 (10), 3646–3658. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2022.1594 (2023).

Liu, H., Jin, Y., Guo, X. & Han, Z. Evolution of butterfly leaf angle in the butterfly plastic zone of the surrounding rock of a circular roadway. J. China Coal Soc. 50 (07), 3388–3399. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2024.0900 (2025).

Li, J., Qiang, X., Ma, N., Zhang, R. & Li, B. Formation mechanism and engineering application of the directionality of butterfly leaf in the butterfly plastic zone of roadway rock surrounded. J. China Coal Soc. 46 (09), 2838–2852. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2021.1150 (2021).

Luo, W. et al. Centrifugal model test on relationship between support pressure of shield tunnel face and ground deformation in water rich sand strata. Rock. Soil. Mech. 43 (S2), 345–354. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2021.1104 (2022).

Guo, X., Guo, L., Ma, N., Zhao, Z. & Li, C. Applicability analysis of the roadway butterfly failure theory. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 49 (04), 646–653. https://doi.org/10.13247/j.cnki.jcumt.001169 (2020).

Guo, X., Zhao, Z., Gao, X., Wu, X. & Ma, N. Analytical solutions for characteristic radii of circular roadway surrounding rock plastic zone and their application. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 29 (2), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2018.10.002 (2019).

Guo, X., Ma, N., Zhao, X., Zhao, Z. & Li, Y. General shapes and criterion for surrounding rock mass plastic zone of round roadway. J. China Coal Soc. 41 (08), 1871–1877. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2016.0787 (2016).

Xue, X. et al. A 3D ubiquitous-multiple-joint model and its application to the stability analysis of TBM excavated roadway in jointed stratum. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56 (2), 1343–1366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-022-03100-6 (2023).

Yang, S., Chen, M., Jing, H., Chen, K. & Meng, B. A case study on large deformation failure mechanism of deep soft rock roadway in xin’an coal mine, China. Eng. Geol. 217, 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2016.12.012 (2017).

Funding

This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52394192), Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Special Program for Key R&D Tasks (2024B03017) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52474114; 52225404).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yunjiang Sun (First Author, Corresponding Author) contributed to the conceptualization, supervision, and resource management of the study, as well as the writing—review and editing of the manuscript. Shuai Guo was responsible for the methodology, formal analysis, and visualization, and also contributed to the writing of the original draft and investigation. Yapeng Wang contributed to the writing of the original draft. Jianping Zuo provided supervision and contributed to the writing—review and editing of the manuscript. Daohan Li was involved in the validation of the study. Yuhao Feng contributed to the formal analysis. Jianan Wang was responsible for the visualization. Yue Tan conducted the investigation, and Jiaxuan Xiao contributed to the formal analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Y., Guo, S., Wang, Y. et al. Evolution of plastic zone in surrounding rock of roadway within anisotropic stratum under complex in-situ stress. Sci Rep 16, 3800 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33938-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33938-z