Abstract

To address the severe deformation and failure of roadway roof and floor encountered when crossing fault zones in coal mines in western China, this study takes the lower gateway of the 11E5-303 working face crossing the SF1 normal fault in Zhaohequan Coal Mine as an engineering case. A comprehensive investigation was conducted using field investigation, laboratory testing, numerical simulation, and engineering applications. The research aims to clarify the deformation mechanisms of the surrounding rock in fault-affected zones and to provide adequate control measures for roadway stability during fault crossing. Studies have shown that the roof and floor strata along the 11E5-303 Working face’s adjacent roadway are primarily composed of siltstone, fine sandstone, and argillaceous siltstone, which are highly susceptible to water-induced softening and swelling, leading to a significant decrease in mechanical strength. This phenomenon is particularly severe near the fault, where substantial roof subsidence and pronounced floor heave are observed. Based on the Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion, the deformation and failure mechanisms of the surrounding rock under the existing support system were analyzed. The study revealed that the roadway surrounding rock within 10 m of the fault zone is subject to intense deformation and damage, with the hanging wall showing a significantly larger failure range than the footwall. Floor heave at the fault zone is also markedly greater than in other sections. These findings identified key support zones and critical reinforcement areas, emphasizing the need for early implementation of high-strength support systems within the fault-affected area to enhance stability. Targeted control technology for surrounding rock stability in fault-crossing roadway was proposed. After optimization, the roof subsidence was reduced by 68% and the floor heaves by 81% compared to the original support system. The optimized support scheme significantly improved the stability of the roadway, demonstrating apparent effectiveness. These results provide valuable guidance for roadway support design and stability control under similar geological conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With economic development, the demand for coal resources is increasing, and the eastern coal resources are depleting, gradually shifting to the western region for mining. However, the mining of the western areas is often characterized by complex geological structures, leading to severe deformation and failure of the roadway surrounding rocks. In particular, the stability control of roadways crossing fault zones has become a significant technical challenge for the safe and efficient advancement of coal mining. Abnormal tectonic stresses and the development of fractured zones within fault areas often result in large-scale dislocation of coal seams and surrounding strata, further causing intense deformation in fault-crossing roadways. Typical problems include severe roof subsidence, floor heave (or sidewall spalling), and frequent failure of support structures, all of which pose significant safety risks to underground construction1,2,3,4,5. Therefore, effectively controlling the deformation of surrounding rock in fault-crossing roadways is key to ensuring safe and efficient coal mining.

Domestic and international scholars have conducted extensive research on the deformation and failure of the roadway surrounding rock under the influence of faults6,7,8,9,10,11. These studies cover various aspects such as qualitative fault investigation, fault prediction techniques, and the stability analysis of fractured surrounding rock near fault zones. Yan Shuai, Bai Jianbiao, et al.12, proposed a support strategy for surrounding rock control to mitigate roadway deformation in fault zones overlain by aquifers. Their method involves a staged reinforcement system, consisting of pre-grouting, shotcrete–anchor–grouting as the primary support, and localized reinforcement using anchor cables and supplementary grouting. This approach provides a practical reference for supporting design in fault-affected roadways. Liu Quansheng et al.13, monitored deformation and support pressure changes in fault fracture zones, providing a basis for optimizing and adjusting information-based construction and design schemes for fault-crossing roadways. Meng Qingbin, Zong Yijiang et al.14,15, addressing the complex lithology and sudden geological hazards associated with fault fracture zones, proposed a reasonable roadway excavation and support technology scheme. This approach ensures the long-term stability and safety of the surrounding rock and support structures. Wang Qi et al.16, for the fault zone coal mine roof breakage problem, respectively established a positive fault and reverse fault tectonic zone of the roof plate elastic beam mechanics model, the study of the roof plate stress distribution law, effectively prevented the occurrence of roof plate accidents; Li Ji, Li Chong et al.17,18, studied the roof failure issue in coal roadways crossing fault zones by using experimental and numerical methods. They investigated the influence of fault zones on roadway stability, providing a basis for the rational layout of roadways and effective control near fault zones. Chen Xiaoxiang et al.19, addressing the problem of large deformation of surrounding rock in fault fracture zones, a combined support method of "pre-grouting mesh-anchor-cable reinforcement" is used to control surrounding rock deformation in faulted areas. This approach mitigates large-scale deformation in the roadway surrounding rock within fault fracture zones. Zhang Zhenquan, Xie Xiaoping et al.20,21, focusing on the severe deformation and failure of surrounding rock in soft rock roadways near coal mine faults, proposed a bolt-mesh-cable support technical scheme, which effectively controlled the deformation of the roadway surrounding rock. Sun Xiaoming, Li Huaibin, Yi Lijuan et al.22,23,24, aiming at the problem of severe roadway deformation, adopted a combination of on-site monitoring, theoretical analysis, and numerical simulation to put forward a new roadway construction and support scheme, which significantly reduced the deformation of the roadway surrounding rock. Rong Hai et al.25, addressing the issue of dynamic pressure and large deformation roadways, took the 2603 air inlet roadway of Zhangcun Coal Mine as an example. Through theoretical analysis of factors such as normal faults, on-site tests, and numerical simulations, they developed a new grouting material and proposed a collaborative support scheme. After application, the roadway deformation was reduced by approximately 87%, achieving effective control. Zhang Wei26, concerning the safe and efficient mining when coal mine working faces and roadways pass through faults, proposed a method for fully mechanized caving faces to pass through significant faults quickly. The results showed that safe and efficient mining was realized, providing a reference for projects under similar geological conditions. Zhang Dong, et al.27, To address the unbalanced bearing coefficient (UBC) of pumpable supports (PPS) under uneven loads along the mining direction, a mechanical model was built and a coupling control method proposed, achieving design-matched UBC, controllable convergence, and stable surrounding rock. Zhang Huoquan, et al.28, To address the challenge of damage assessment and early warning for resin-anchored bolt anchorage debonding, the transverse vibration of the free segment was tested via pull-out tests. The damage degree was established, the influence of length was investigated, TVF evolution was clarified, early warning was built, supporting anchorage parameter design.

However, the destructive deformation mechanism of surrounding rock in soft rock roadway under the influence of fault tectonic stress in Chinese coal mines is intricate and different, and there is still room for improvement in theoretical and technical research. Based on previous research, this study focuses on the 11E5-303 Working face’s adjacent roadway crossing a fault in the Zhaohequan Coal Mine, Tuokexun, Xinjiang. The study summarizes the instability characteristics of expansive soft rock roadways under similar geological conditions, and gathers the physical and mechanical parameters of the surrounding rock in soft rock roadways. A simulated analysis investigated the evolution of stress, displacement, and plastic zone under different support schemes for soft rock roadways. Based on these findings, an optimized support strategy is proposed to achieve stable control of roadways in such conditions.

Engineering background

Engineering overview

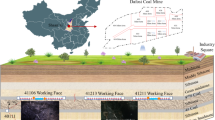

Zhaohequan Coal Mine, situated in the Kelan area of the Turpan Basin, Xinjiang, utilizes a mechanized longwall retreat mining method along the strike of the coal seam. The presence of fault structures within the mine poses significant challenges to the design and stability of soft rock roadways, significantly impacting safe production and operational efficiency.

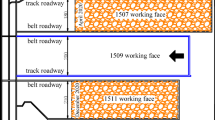

Figure 1 shows the lower gateway of the 11E5-303 working face. This working face primarily exploits the 5–3 coal seam, which has an average thickness of 6.6 m and an average burial depth of 130 m. The coal seam exhibits minimal undulation and is nearly horizontally distributed, representing a stable and fully mineable coal seam across the area. Figure 2 illustrates the coal-rock columnar section of the Working face. The surrounding rock roof of the soft rock roadway is mainly composed of siltstone, fine sandstone, and argillaceous siltstone. Among them, the mudstone is gray with well-developed horizontal bedding; the siltstone is grayish-white, in medium-thick layers, and contains plant fossils. The floor consists of siltstone, fine sandstone, and silty mudstone.

The geological structure of this working face is relatively complex. Approximately 968.65 m ahead of the lower gateway of the 11E5-303 working face (measured from the No. 1 return air incline), there is the SF1 normal fault. This fault is located in the western-central part of the exploration area, with a strike direction of NNE, a dip direction of NWW, and a dip angle ranging from 70° to 76°. The fault throw varies between 0 and 5 m, with an extension length of approximately 760 m within the region. We list the fault parameters in Table 1.

Initial support system and characteristics of surrounding rock deformation and failure

The lower gateway of the 11E5-303 working face is driven along the floor of the 5–3 coal seam, with a rectangular cross-section. The net width of the roadway is 4.5 m, the net height is 3.2 m, and the cross-sectional area is 14.4 m2. For the roadway roof, φ20 mm × 2500 mm threaded steel bolts are used, and for the two sides of the roadway, φ20 mm × 2200 mm threaded steel bolts are adopted, with a spacing and row spacing of 800 × 800 mm, and 14 bolts in each row, with an anchoring force of 60 kN. The anchor cables use φ17.5 × 7300 mm steel strands, with a spacing and row spacing of 1600 × 1600 mm, two anchor cables in each row, and a pre-tightening force of 120kN. The original support scheme of the roadway is shown in Fig. 3.

According to the on-site investigation of the current 11E5-303 lower gateway, the surrounding rock of the roadway has large deformation, showing an overall inward shrinkage phenomenon. Notably, localized roof subsidence is pronounced, with a maximum displacement of approximately 310 mm. The roadway floor exhibits control failure, with severe floor heave reaching a deformation magnitude of up to 400 mm. The overall stability of the surrounding rock is significantly compromised, indicating severe deformation and failure. Affected by the tectonic stress of the SF1 fault and the disturbance from excavation, the coal and rock around the fault-crossing area of the 11E5-303 working face lower gateway have cracked. This is particularly evident in the soft coal part at the upper section of the roadway sides, where the coal mass has undergone flaky fracturing and loose fragmentation, making it highly prone to collapse. Over time, significant deformation and severe damage have developed in the surrounding rock. Spalling ribs occur in the upper-middle section of the sidewalls, forcing the steel mesh and rebar ladders outward or even torn apart, forming large sagging mesh pockets. The deformation and failure characteristics are shown in Fig. 4.

Influencing factors of roadway deformation and failure

Through in-depth analysis of the deformation and failure phenomena of the lower gateway in the 11E5-303 working face, combined with geological data, field investigations, ground stress test results, and relevant theories such as rock mechanics and material mechanics, the key factors affecting roadway deformation and failure are initially identified as follows:

-

(1)

Tectonic stress concentrates when a roadway crosses a faulted geological structural zone. This is mainly manifested near the fault zone, where the overlying strata interrupt the continuity of energy transmission during stress transfer. Intense floor heave occurs primarily in the weak segments of the surrounding rock mass, notably in the unsupported roadway floor strata.

-

(2)

The properties of rocks, such as strength, hardness, toughness, and porosity, significantly influence roadway stability. For instance, weak rocks, characterized by low compressive strength, are prone to plastic deformation and damage after excavating the roadway. The roof strata of the 5–3 coal seam are mainly composed of siltstone, silty mudstone, and fine sandstone. Due to the combined effects of geological sedimentation, diagenesis, and subsequent geological transformation, the fine-grained facies of the roadway surrounding rock has been formed. Overall, the roof of the 5–3 coal seam is predominantly composed of fine-grained lithologies such as siltstone, fine sandstone, and argillaceous siltstone. The surrounding rock exhibits low strength and is prone to softening upon water exposure, adversely affecting roof stability. The detection results of weak structural zones in the roadway roof are shown in Fig. 5. A distinct fractured zone is observed from the detection borehole entrance, primarily caused by the coal and rock layers’ inherent structure and mining-induced disturbances.

-

(3)

The lower gateway of the 11E5-303 working face has a large cross-section and poor surrounding rock stability. Thick coal seams usually require considerable mining heights, which have high requirements for the size of the roadway cross-section, resulting in a large cross-sectional area of the coal roadway. Especially when crossing faults, the mine pressure behavior is intense. After roadway excavation, an extensive range of fractured and plastic zones is generated immediately. The mechanical properties of the surrounding rock show obvious softening characteristics, and their sensitivity to changes in external conditions is enhanced. The roadway height is directly related to the extent of damage on both sidewalls; the greater the height, the more pronounced the sidewall damage. This reduces the support pressure on the roof, while the horizontal stresses on both sidewalls increase, causing more significant floor heave. The heave of the roof, sidewalls, and floor interacts and exacerbates each other, leading to poor overall integrity of the coal roadway’s surrounding rock and complicating surrounding rock control.

Physical and mechanical testing of the surrounding rock

To further understand the deformation and failure characteristics of the surrounding rock in fault-crossing roadways, on-site sampling of coal seam and roof-floor rock samples was conducted from the lower gateway of the 11E5-303 working face in Zhaohequan Coal Mine. Laboratory tests were carried out to analyze the physical and mechanical properties of the surrounding rock in the fault-crossing soft rock roadway.

Rock sampling and testing

The samples include coal seam specimens and roof and floor rock samples obtained on-site, as shown in Fig. 6.

Standard specimens were prepared, and laboratory tests were conducted to determine the physical and mechanical parameters of the coal and rock samples from the 11E5-303 lower gateway, including uniaxial compressive strength, elastic modulus, shear strength, and tensile strength.

Analysis of test results

Uniaxial compressive test results

Uniaxial compression tests were performed on the collected specimens according to the specified requirements. The tests were strictly conducted in compliance with the standards for rock specimens issued by the industry, and the loading was carried out using the method required by the rock mechanics test specifications. The specimens after loading are shown in Fig. 7.

As shown from the uniaxial compression test results in Fig. 8, the roof siltstone exhibits the highest peak stress, indicating that it can withstand the maximum load under uniaxial compression and thus has relatively high strength. In contrast, the coal seam shows the lowest peak stress, corresponding to relatively low strength, while the roof mudstone and floor siltstone peak stresses fall within the intermediate range. The slope of the stress–strain curves for coal and roof mudstone changes relatively gradually. After entering the plastic stage, they can sustain a specific load while deformation increases. In contrast, the curves for roof siltstone and floor siltstone exhibit a steeper slope change approaching peak stress, indicating rapid development of internal damage.

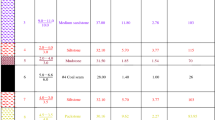

Mechanical parameters of specimens

Analysis and comparison of the mechanical parameters in Table 2 indicate that the roof siltstone exhibits the highest strength, reaching 22.86 MPa, demonstrating the most substantial resistance to external forces. The 5–3 coal has the lowest strength at only 6.45 MPa, indicating a relatively weak load-bearing capacity. The roof mudstone and floor siltstone have intermediate strengths of 11.02 MPa and 15.65 MPa, respectively. Such differences in strength significantly influence the stability of the roadway surrounding rocks. The coal mass with low strength is prone to deformation and failure, which may trigger problems such as severe deformation and damage in soft rock roadways. Additionally, variations exist in the elastic modulus among different rocks. Specifically, the coal seam has the smallest elastic modulus compared to other rock types, indicating that coal is more susceptible to elastic deformation under the same external force than other materials. The variation of Poisson’s ratio can reflect the evolution of internal damage within the rock; a higher Poisson’s ratio indicates greater damage. Comparative analysis of the uniaxial compression test results shows significant differences in compressive strength among the rocks, indicating well-developed bedding and jointing, classifying them as medium-strength rocks.

Hydro-mechanical and XRD analysis of expansive rock samples

The 11E5-303 working face is situated within the Xishanyao H-Ⅱ-2 aquifer, which belongs to the Jurassic bedrock fissure water-bearing system. This aquifer serves as the mine’s direct water-filling aquifer, and during the excavation of the lower gateway, phenomena such as local water seepage and dripping from the roof and coal wall may occur. Therefore, to better understand the causes of rock expansibility, we conducted experiments on rock softening behavior upon water immersion and XRD (X-ray diffraction) analysis of coal and rock samples.

Rock water-softening test

A small piece of argillaceous sandstone sample was selected and placed in a beaker, into which water was added until the specimen was completely submerged. The water-immersion softening process was observed, as illustrated in Fig. 9.

As shown in Fig. 9, the water immediately became turbid upon addition (Fig. 9b). After 2 h, the rock block began disintegrating and softening (Fig. 9c). After 3 h, the rock transformed into a muddy state (Fig. 9d), with further disintegration and softening. The softened portion significantly increased, resulting in an overall softening of the rock block and substantially reducing its overall strength. This test indicates that the argillaceous sandstone exhibits severe argillization. During the roadway support process, special attention should be paid to the amount of production water used to avoid accumulating excessive production water. Meanwhile, efforts should be made to minimize the moisture content in the air as much as possible, thereby preventing the softening effect of water on the surrounding rock of the roadway.

XRD analysis of coal and rock samples

X-ray diffraction (XRD) tests were conducted using a D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer. After curing to the predetermined age, suitable samples were selected and soaked in isopropanol solution for 24 h to terminate hydration. Subsequently, the samples were dried in a vacuum oven at 40 °C for 6 h. The dried samples were then ground into powder, passed through an 80 μm square mesh sieve, and scanned by the XRD instrument at a rate of 5° per minute. The D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer is shown in Fig. 10.

As shown in Fig. 11, XRD testing was performed on roof rock samples, and the results are as follows:

The main mineral components of the roof mudstone specimens are quartz, illite, kaolinite, and chlorite, with contents of 49.66%, 15.29%, 21.88%, and 13.18% respectively.

The main mineral components of the mudstone samples are quartz, illite, kaolinite, and chlorite, with both siltstone and mudstone containing a relatively high proportion of kaolinite. Argillaceous sandstone is a typical type of highly expansive soft rock. Its clay minerals tend to soften and expand when in contact with water and are prone to weathering, which reduces their strength. This makes it challenging to support roadways constructed in such soft rock.

Analysis of roadway deformation, failure, and control strategies

Mechanical analysis of normal fault formation

Anderson model of normal fault formation

As shown in Fig. 12, based on Griffith’s rock mass strength criterion, the Anderson model posits that shear failure in rock masses occurs under the superposition of three principal stresses. A normal fault is generated when the vertical direction corresponds to the maximum principal stress, and the horizontal directions correspond to the intermediate and minimum principal stresses. In this case, the maximum principal stress σ₁ is oriented vertically, while the intermediate principal stress σ₂ and minimum principal stress σ₃ lie in the horizontal plane.

Stress evolution in normal faults

Based on Anderson’s model for normal fault formation as described earlier, it is known that the direction of the maximum principal stress σ₁ during the formation of a normal fault is vertical, meaning σ₁ is the gravity of the overlying strata. The stress state during fault formation is shown in Fig. 13. Shear fractures in coal and rock masses generate fissures. Under continuous tectonic stress, the rock masses on both sides of the fissures move relative to each other, eventually forming a fault.

According to the Mohr–Coulomb criterion, the everyday stress σ and shear stress τ on the fault plane can be expressed by the following formula:

In the formula: C is the cohesion of the fault plane, MPa; τ is the internal friction angle of the rock.

After algebraic manipulation of the above three equations, the resulting expressions are as follows:

The rock cohesion C and internal friction angle φ are assumed to be constant for a specific fault. Under this condition, both the everyday stress σ and shear stress τ on the fault plane depend solely on the minimum horizontal principal stress σ3, and exhibit a positive linear relationship with it. During roadway excavation, when the fault is exposed, the original in-situ stress field becomes disturbed, and the stress state of the fault is directly transferred to the surrounding rock of the roadway. If the everyday stress σ and shear stress τ on the fault plane exceed the shear strength of the fault, expressed as \(\tau = C + \sigma \tan \varphi\), fault slip or dilation may occur. This disrupts the equilibrium of the original in-situ stress field and leads to a redistribution of stress around the roadway. In the geostress environment of a roadway intersecting a normal fault, the principal stresses σ1 and σ3 govern the mechanical response of the surrounding rock, with the minimum horizontal principal stress σ3 serving as the dominant control parameter. An elevated σ3 leads to a proportional increase in the everyday stress σ and shear stress τ acting on the fault plane, thereby enhancing the fault’s reactivation potential. This intensifies stress perturbation transmitted to the surrounding rock mass, significantly accelerating the deformation rate and increasing the magnitude of roadway deformation.

Taking the case of the lower gateway of the 11E5-303 working face crossing a fault as the research object, this paper illustrates the relationship between the mechanical state of the fault and the stress transfer in the surrounding rock of the roadway: when the lower gateway of the 11E5-303 working face is excavated and encounters a fault, factors such as the fault dip angle and the width of the fractured zone affect the stability of the surrounding rock. It is therefore necessary to analyze the law of roadway deformation and failure caused by stress transfer. Based on the in-situ measured mechanical parameters of coal, as summarized in Table 3, the integrity of the rock mass within the fault zone is significantly compromised due to tectonic activity, resulting in a systematic degradation of both cohesion and internal friction angle compared to more stable areas. At the fault zone, the rock mass exhibits a cohesion C = 1 MPa, an internal friction angle φ = 25°, a maximum principal stress σ1 = 13 MPa, σ3 = 3 MPa, and a fault dip angle α = 75°.

First, the normal stress σ and shear stress τ on the fault plane are calculated as follows:

Then, combined with the Mohr–Coulomb criterion, \(\tau = C + \sigma \tan \varphi\), the results are verified as follows:

The calculated shear stress τ (approximately 2.5 MPa) is close to the shear strength, indicating that the fault is in a critical sliding state and prone to activation.

Numerical simulation model

Numerical simulation of the deformation and failure behavior of the surrounding rock in soft rock roadways crossing faults was conducted using FLAC3D software. The geometric model was first constructed externally using Midas software, with dimensions of 40 m × 67.5 m × 42 m along the x, y, and z directions, respectively, as shown in Fig. 14. The external model was then imported into FLAC3D as a mesh. Based on the specific geological conditions of the Zhaohequan coal mine, loads and boundary conditions were applied to the model for simulation.

Taking the lower gateway of the 11E5-303 working face as the research object, the gateway has a net width of 4.5 m, a net height of 3.2 m, and a cross-sectional area of 14.4 m2. It intersects a fault with a dip angle of 75°, and the burial depth of the gateway is 260 m. According to the on-site geological conditions, a vertical stress corresponding to the relevant conditions is applied to the upper boundary of the model; the model is constrained in terms of displacement and initial velocity in the x, y, and z directions, and an equivalent overlying strata load of 5.25 MPa is applied to the top. The simulation adopts the Mohr–Coulomb criterion based on elastoplastic theory, and the physical parameters of the rock strata are listed in Table 3.

Simulation results and analysis

Stress evolution in the fault zone surrounding the rock under the original support

In underground engineering, the self-weight and tectonic stress fields constitute the original rock stress field’s main components, and fault activities significantly influence changes in the stress field. A fault is a geological structure formed by displacing the hanging wall and footwall along a plane under tension or compression. During its formation, it is often accompanied by the release of substantial energy, which affects the in-situ stress around the fault and the rock mass’s elastoplastic state, forming a specific plastic failure zone. Moreover, the direction of the maximum principal stress around the fault tends to impact the roadway considerably during its excavation through the fault. The lower gateway of the 11E5-303 working face advances from the hanging wall toward the footwall of the fault. The contour map of vertical stress distribution in the surrounding rock at various distances from the fault is shown in Fig. 15.

The stress transfer affected by the fault leads to an apparent discontinuity in the vertical stress field of the surrounding rock. As can be seen from Fig. 15, the stress shows a significant decreasing trend as the excavated roadway approaches the fault. In the vicinity of the fault zone, due to the weak lithology, poor cementation, low integrity, and strength of the fault fractured zone, the surrounding rock stress within the fractured zone is lower than that in the roadway surrounding rock of the upper and lower walls. Within a specific range of the fault’s hanging wall, the stress significantly decreases as the excavated roadway approaches the fault. In the footwall of the fault, the stress gradually increases to the original rock stress as the gateway moves away from the fault. The influence range of the fault on the original rock stress is approximately 15 m from the fault plane.

During the excavation of the lower gateway across the fault, affected by the tectonic stress of the fault, the vertical stress of the roadway surrounding rock shows a trend of first decreasing and then increasing. The surrounding rock stress on both sides of the fault increases, while the surrounding rock stress at the fault location decreases significantly. When the lower gateway is 15 m before the fault, 5 m before the fault, at the fault, in the middle of the fault zone, 5 m after the fault, and 15 m after the fault, the vertical stress on both sides of the gateway at these positions is 8.6 MPa, 8.6 MPa, 7.26 MPa, 7.07 MPa, 7.55 MPa, and 7.50 MPa respectively, with the stress concentration factors being 1.32, 1.32, 1.12, 1.09, 1.16, and 1.15 (the original rock stress is 6.5 MPa). The fault zone is severely damaged, and the fault has an obvious stress reduction zone. It can be seen that the fault-crossing area is a key support zone for the roadway.

Failure mechanism of the roadway surrounding rock

As shown in Fig. 16, in the hanging wall of the fault, the plastic zone is dominated by shear failure, featuring a roof plastic depth of 2.5 m, a floor plastic depth of 3.8 m, and a sidewall failure extent of 3.6 m. Within the fault zone, combined shear—tensile failure occurs, triggering a notable expansion of the plastic zone: the roof plastic depth remains 2.5 m, the floor plastic extent increases to 4 m, and the sidewall failure extent reaches 4 m. Simultaneously, the roadway surrounding rock undergoes exacerbated flexural deformation toward the free face, with the stress concentration entrapped in the fault zone dissipating synchronously as the plastic zone propagates rapidly toward sidewalls and floor corners. In the fault footwall, the plastic zone reverts to single shear failure, with its extent reduced relative to the fault zone—a roof plastic depth of 2.6 m, a floor failure extent of 3.8 m, and a sidewall failure extent of 3.7 m. Here, the failure mode simplifies, and the plastic extent falls between those of the hanging wall and the fault zone.

Due to extensive damage to the surrounding rock of the roadway roof and floor, particularly tensile failure occurring to varying degrees in both the roof and floor, stress unloading occurs in these regions. Meanwhile, the two sides remain bearing, subjected to compressive vertical stress, causing them to move inward toward the roadway, resulting in sidewall convergence.

Roadway deformation analysis under various support schemes

To further analyze the influence of the fault on the deformation behavior of soft rock roadways, deformation contour maps of the roadway at different distances from the fault under both original and optimized support schemes are presented in Fig. 17. The fault affects the surrounding rock of the roadway roof and floor. Within a specific range on the hanging wall side of the fault, the roof subsidence tends to decrease as the roadway advances closer to the fault, while the floor heave increases. The largest displacements of the roof and floor occur when the excavation reaches the fault zone. Under the original support scheme, the roof subsidence reached 260 mm, and the floor heave was 403 mm, resulting in a combined convergence of 663 mm between the roof and floor in the fault zone, indicating severe roadway deformation. As the roadway moved away from the fault zone on the footwall side, the roof and floor surrounding rock deformation decreased accordingly. After implementing the optimized support scheme, the maximum roof subsidence was reduced to 74 mm, and the maximum floor heave to 96 mm, with a total deformation of 170 mm. Compared to the original support, the optimized support reduced the total roadway deformation by 74%, significantly improving the stability of the surrounding rock.

Under a certain degree of damage, the deformation of the roadway surrounding rock is fixed due to the principle of energy conservation. When the roof subsidence decreases, the floor heave will increase. Moreover, as the roadway is affected by the fault zone—where the rocks in the fault fracture zone are fragmented with poor cementation, low integrity, and low strength—the fracture zone is prone to instability when the roadway passes through the fault. This exacerbates the deformation of the roof and floor, resulting in the maximum deformation of the roadway in the middle of the fault zone, with the overall floor heave being significantly greater than the roof subsidence.

Analysis after support optimization

After optimization, Fig. 18 shows the roof and floor deformation of the surrounding rock in the fractured zone of the fault crossing area under the original support condition and the optimized support condition.

As seen from Fig. 18, under the original support condition, the deformation of the roadway roof reaches its maximum before entering the fault fractured zone, and the deformation decreases relatively as it approaches the fault zone. In contrast, the deformation trend of the roadway floor is first increasing and then decreasing, with the maximum deformation reaching approximately 400 mm in the fault fractured zone; as it moves away from the fault zone, the deformation decreases slowly, and the floor heave is greater than the roof deformation. The optimized and original support deformation curves show roughly the same trend, but the overall deformation is reduced. The deformation control effect on the surrounding rock of the roadway within the fault zone is the best: the roof subsidence is less than 100 mm, and the floor deformation is reduced to 75 mm. After the optimized support is adopted, the roof subsidence of the roadway is reduced by 68% compared with the original support method, and the floor convergence is reduced by 81%, indicating that the stability of the roadway surrounding rock has been well controlled.

Engineering application

Optimized support design for roadway

Based on laboratory tests and numerical simulation analysis, floor bolting and increased pre-tightening force of bolts were adopted since the roadway floor undergoes the most severe deformation when crossing the fault zone. The optimized support scheme for the roadway crossing the fault zone is determined as follows:

Both ribs’ bolt density is increased, and floor bolts are added for support. The roadway roof is supported by φ20 mm × 2500 mm threaded steel bolts, with a row spacing of 700 mm × 700 mm, 19 bolts per row, and an anchorage force of 80 kN. The ribs are reinforced using φ20 mm × 2200 mm threaded steel bolts, arranged at a spacing of 700 mm × 700 mm, with 19 bolts per row and an anchorage force of 80 kN. Cable bolts are φ17.8 mm × 7300 mm steel strands, arranged at a spacing of 1600 mm × 1600 mm, with two cables per row and a pre-tightening force of no less than 200 kN.

For the floor support bolts in the roadways of the hanging wall and footwall, φ20 mm × 2500 mm threaded steel bolts are used, with a spacing and row distance of 1750 × 700 mm, three bolts per row, and an anchoring force of 80kN. In the severely damaged fault-crossing area, φ22 mm × 2500 mm threaded steel bolts are adopted, with the same spacing and row distance of 1750 × 700 mm and three bolts per row. The optimized support is shown in Fig. 19.

Field monitoring results

The method was applied in the field, and Fig. 20 shows the deformation curve of the soft rock roadway over a specific period.

As shown in Fig. 20, the deformation of the roof, floor, and both sides of the soft rock roadway tends to stabilize after approximately 45 days. The maximum deformation of both sides is about 140 mm, and the maximum deformation of the roof and floor is about 160 mm. Monitoring results indicate that the optimized support can effectively control the deformation of the surrounding rock in the soft rock roadway.

Conclusions

-

(1)

The main causes of large deformation and support structure failure in soft rock roadways crossing faults are as follows: shear slip failure occurs at the fault; the cross-section of the soft rock roadway is relatively large; the original support scheme is insufficient in strength; the floor heave control of the soft rock roadway in the 11E5-303 working face fails; and the severe floor heave leads to large deformation of the surrounding rock of both sides and the roof of the soft rock roadway.

-

(2)

Through physical and mechanical tests on the surrounding rock, it is found that the roof strata of the 5–3 coal seam mainly consist of siltstone, silty mudstone, and fine sandstone. The surrounding rock has low strength and is prone to softening when exposed to water, adversely affecting the roof’s maintenance. The floor of the 5–3 coal seam is mainly composed of siltstone and fine sandstone, with the surrounding rock mostly fine-grained. Its structural planes are mainly bedding planes, followed by joints and fractures in local areas. Therefore, problems such as floor heave and rib spalling, which lead to large deformation, are likely to occur during underground mining.

-

(3)

Based on the engineering background of the lower gateway of the 11E5-303 working face crossing the fault geological structure, Midas and Flac3D were used to simulate the original support scheme for the soft rock roadway with a fault in the 11E5-303 working face. It is shown that the fault will change the stress condition of the surrounding rock: due to the fragmented rock mass in the fault zone, the stress there decreases slightly, but the stress concentration area expands. In addition, the roof and floor of the soft rock roadway undergo severe deformation. Accordingly, an optimized support scheme is proposed, which involves reinforcing the roof and floor with high-strength bolts and reducing the spacing between bolts on both sides. This scheme aims to enhance the self-bearing capacity of the surrounding rock and improve the stability of the soft rock roadway.

-

(4)

According to on-site monitoring, after the optimized support scheme is adopted, the deformation of the surrounding rock in the soft rock roadway crossing the fault is significantly reduced. In particular, the deformation of the surrounding rock on the floor of the soft rock roadway has been well controlled, ensuring safety and long-term stability.

Data availability

The data used to support the finding of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Yang, R., Zhu, Y., Li, Y., Li, Y. & Xiao, B. Stability analysis and control strategy of weakly cemented layered floor in mining-affected roadway. J. China Coal Soc. 07, 2667–2680 (2020).

Hojjat Ollah Safari, S. et al. Geohazards analysis of Pisa tunnel in a fractured incompetent rock in Zagros Mountains, Iran. Arab. J. Geosci. 6(04), 1101–1112 (2013).

Yu, T., Zhang, Q., Zhang, S., Zhao, G. & Fang, Y. Characteristics analysis and stability control of surrounding rock crossing the mined-out area roadway. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 17(03), 909–917 (2021).

Tao, Z., Zhu, C., He, M. & Karakus, M. A physical modeling-based study on the control mechanisms of Negative Poisson’s ratio anchor cable on the stratified toppling deformation of anti-inclined slopes. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 138, 104632 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Rock burst mechanism and characteristics of roadway in “fault-fold” structure area. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 01, 69–81 (2023).

Wang, X., Bai, J., Li, L. & Han, Z. Deformation failure mechanism and control technology of mining-induced roadway near a fault. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 31(05), 674–680 (2014).

Wang, J. et al. Mechanism of roadway floor heave and control technology in fault fracture zone. J. China Coal Soc. 44(02), 397–408 (2019).

Yu, H., Xu, Y. & Yuan, Y. Seismic input method coupling ground motion and fault dislocation for near-fault engineering sites. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 54, 2206–2220 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Failure mechanism of roadway under dynamic load in the fault zone of a steeply inclined coal seam. Eng. Mech. 1–13 (2024).

Zhao, Q. et al. Deformation and stress distribution laws of quarry roadway surrounding rock under multiple fault conditions. Min. Saf. Environ. Prot. 52(02), 0097–0108 (2024).

Li, J., Hu, W. & Zhang, H. Numerical analysis on roadway stability by fault cutting surrounding rock. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 14(S2), 925–929 (2018).

Yan, S., Bai, J., Zhang, Z., Tong, S. & Wu, M. Failure mechanism and ground control of a principal entry above aquifers crossing a fault zone. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 33(06), 979–984 (2016).

Liu, Q., Zhang, W., Lu, X. & Fu, J. Safety monitoring and stability analysis of a large-section roadway in a fault fracture zone. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 29(10), 1954–1962 (2010).

Meng, Q. et al. Study and application of key technology for roadway crossing faults under complex geological conditions. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 02, 199–207 (2017).

Zong, Y., Han, L., Huang, X. & He, H. Grout-recovering and support technology of water-bursting roadway under high confined water pressure. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 33(06), 992–998 (2016).

Wang, Q. et al. Analysis of roof collapse mechanism and supporting measures in the fault zone of coal roadway. J. Rock Soil Mech. 33(10), 3093–3102 (2012).

Li, J. et al. Risk assessment of roof fault activation induced by mining stress deflection in mining roadway. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 42(S2), 4109–4120 (2023).

Li, C., He, S. & Chen, L. Study on asymmetric fracture mechanism and control strategy of soft rock roadway roof with large span section and crossing fault. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 38(06), 1081–1090 (2021).

Chen, X. & Wu, J. Study the mechanism and control technology of the large deformation of the roadway surrounding rock in the fault fracture zone. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 35(05), 885–892 (2018).

Zhang, Z. Stress analysis and support research of surrounding rock in DeepHigh high-stress soft rock roadway. Coal Technol. 6, 49–51 (2018).

Xie, X., Wu, G., Yu, R. & Liu, X. Study on the failure mechanism and control technology of the surrounding rock of soft rock roadway near fault. Coal Sci. Technol. 9, 195–202 (2020).

Sun, X., Wang, J. & He, M. Instability mechanism of mining roadway passing through fault at different angles in a kilometre-deep mine and control measures of roof cutting and NPR cables. J. Mt. Sci. 21(1), 236–251 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Instability characteristics of surrounding rock and surrounding rock control technology of deep coal roadway crossing the fault: a case study of Zhuxianzhuang coal mine, 15(1) (2024).

Yi, L., Pan, W. & Huang, Z. Study on the support technique of the fracture zone influenced by the roadway passing through the fault. Coal Eng. 50(04), 48–50 (2018).

Hai, R. et al. Research on the main influencing factors and complete support technology for dynamic pressure and large deformation roadway. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 4136 (2023).

Zhang, W., Yang, F. & Xiang, J. A method and engineering practice for a fully mechanized caving coalface to rapidly pass through a large fault. Appl. Sci. 15(2), 731 (2025).

Zhang, D. et al. Stability mechanism and control of the pumpable supports in longwall recovery room. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 34(07), 957–974 (2024).

Zhang, H., Shi, H., Zhao, H. & Song, L. Characterization of transverse vibration response of resin-anchored bolt under axial tension and life cycle health assessment of anchorage debonding. Measurement 256, 118273 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all editors and reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Funding

This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 52374129).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. provided the original idea; Z.H wrote the main content of the manuscript; B.J. provided the data for this paper; Z.X. made the figures and tables of this paper; Z.H polished the paper and wrote the first draft; Z.Z. was responsible for the review and editing work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Han, Z., Jiang, B. et al. Characteristics of deformation and failure with support countermeasures for expansive soft rock roadway crossing faults in the western region. Sci Rep 15, 35373 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19390-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19390-z